3 minute read

EDITOR'S NOTE

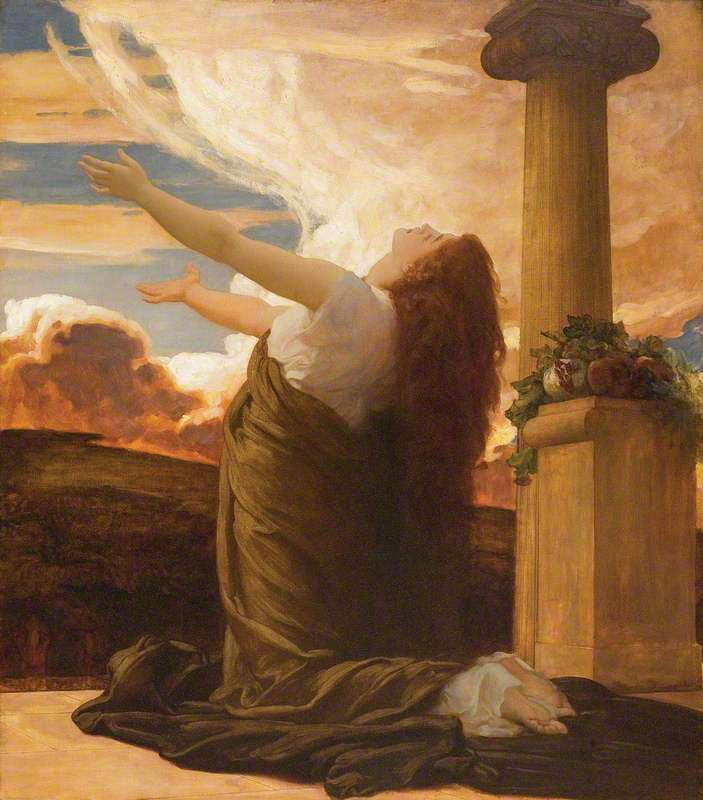

image: The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Culture Service, Leighton House Museum A ll the while i was growing up, my family had a kitchen garden. It seemed everyone in the suburbs did then—the source of late-summer tomatoes, a few scraggly carrots, cucumbers, parsley and those exuberantly abundant zucchinis that we kids carted off to share with neighbors.

In addition to these basics, my mother always planted a few massive sunflowers. Unlike the parsley, cucumbers and tomatoes, the flowers served no practical function—they were simply there as benevolent sentries, something my mom planted each year so we could watch them grow from tiny sprouts to colossal tree-like fixtures, then save, dry, plant and begin again.

TOWARD THE SUN

by CARA MCDONALD

The act of planting those sunflowers every summer was one of creating a moment of beauty, a long growing season culminated in a short-lived, dazzling bloom that was simply there to teach and delight us before bending to the birds.

Whether they appeal to our inner Klimt or Van Gogh or our sunshine-deprived Midwestern souls, sunflowers seem to invite a collective viewing and sigh of appreciation, like an August sunset or a fireworks finale.

They’ve captured our imagination in history, art and mythology—Ovid tells of the story of Apollo and Clytie, a sea nymph who fell in love with but was spurned by the sun god. (He ran after Leucothoë, a Babylonian princess; it ended badly.) Grief-stricken, obsessed, Clytie crawled out of the water and sat stunned and disheveled on the bare ground, subsisting for days on dew and her own tears, only moving to turn her gaze to follow Apollo’s golden arc across the sky. The story goes that over time her limbs clung to the soil and a flower sprouted to hide her tears, and she became a sunflower, which to this day turns its face to follow the sun as it moves across the heavens.

Apollo’s appalling behavior and Clytie’s lack of healthy boundaries notwithstanding, there’s something about the notion of a field of sunflowers following the sun—a small army of devoted, riotous, beautiful nymphs moving in golden unison—that just stops the heart.

All across Northern Michigan, there’s a growing, unsung network of sunflower farms and fields. You won’t find them on most maps, but as word of them spreads, their call is irresistible. From observation decks or behind artists’ easels, from roadside picnics to U-Pick stands, we’re all invited to partake in the wild celebration of this here-and-there crop, grown by equal parts farmers and fanatics, that lights up the landscape for a few precious days each August.

The guide in this month’s issue will steer you to a field that takes your breath away. I hope it lets you share a moment of communion with your fellow visitors and invites you to revel in a moment of summer sunshine that begs us to stop what we’re doing and turn our faces to the sky. Devotion, hopefulness, awe, togetherness, fleeting beauty.

“Clytie” by Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

What better symbol of summer could we ask for? The fields are waiting to show us.

Don’t take my word for it—the poet Mary Oliver penned an invitation far more beautiful:

…each of them, though it stands in a crowd of many, like a separate universe, is lonely, the long work of turning their lives into a celebration is not easy. Come

and let us talk with those modest faces, the simple garments of leaves, the coarse roots in the earth so uprightly burning. —Mary Oliver, “The Sunflowers”

Cara McDonald, Executive Editor cara@mynorth.com

YOU’RE INVITED

Named “Most Beautiful Place in America” by the viewers of Good Morning America, and sitting pretty on National Geographic’s list of “21 Best Beaches in the World.” There are plenty of places to vacation, but nowhere comes close to Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. You don’t have to take our word for it though. Come experience the magic of Northern Michigan for yourself.