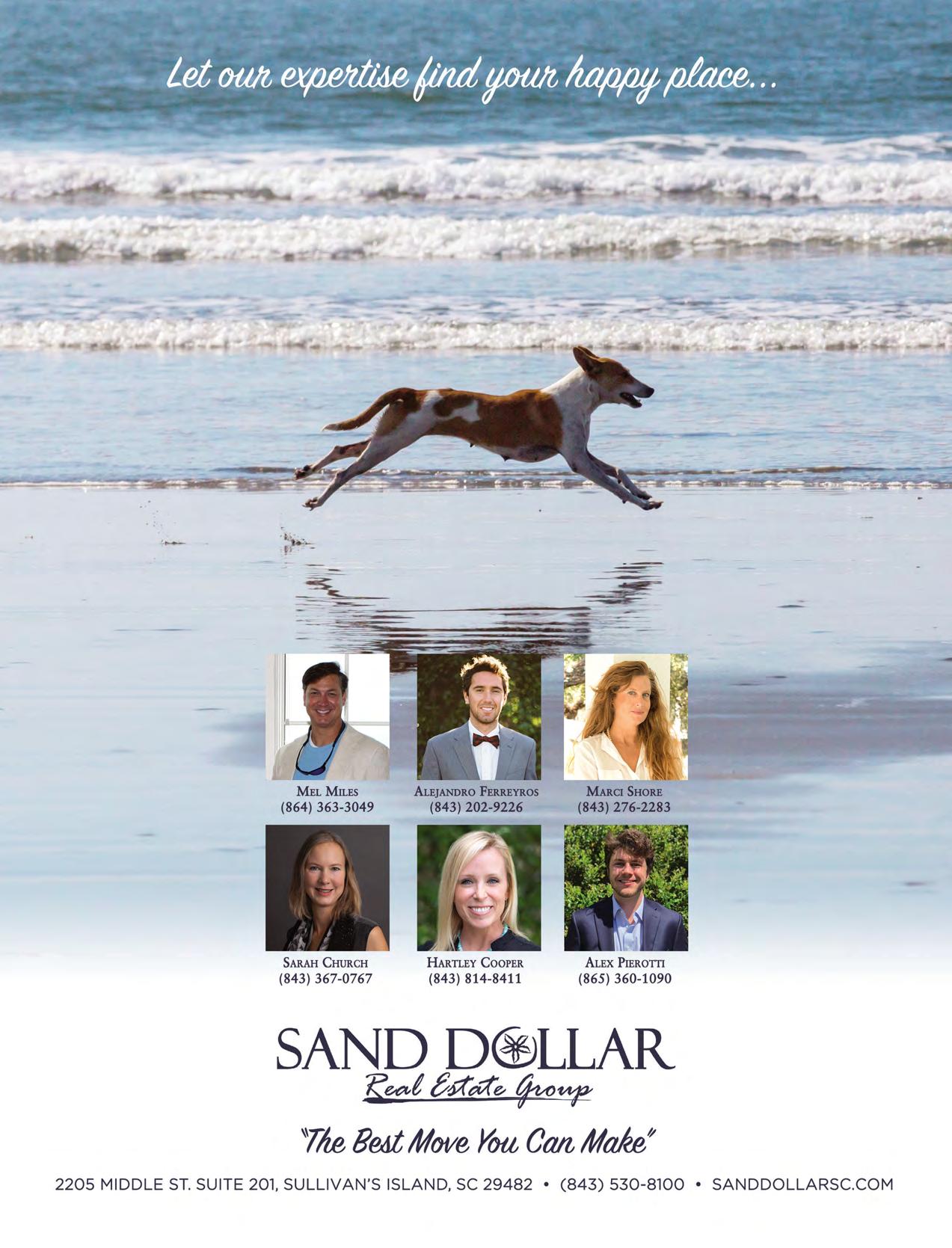

Whether you’re making vacation memories, planning a move, or looking for an investment... Nobody knows the Charleston Coast better.®

Consider Dewees Island. Experience the wild and unspoiled beauty of the Lowcountry. Protected as a nature preserve, the timelessness of Dewees will be preserved for generations to come.

76 | PANDEMIC PIVOTS

How six islanders adjusted to the COVID19 pandemic and came out stronger, wiser, and incredibly grateful for their coastal community.

By Kinsey Gidick

84 | THE GATHERING PLACE

Redfishing and breeze-shooting at the Isle of Palms Marina

By Hastings Hensel

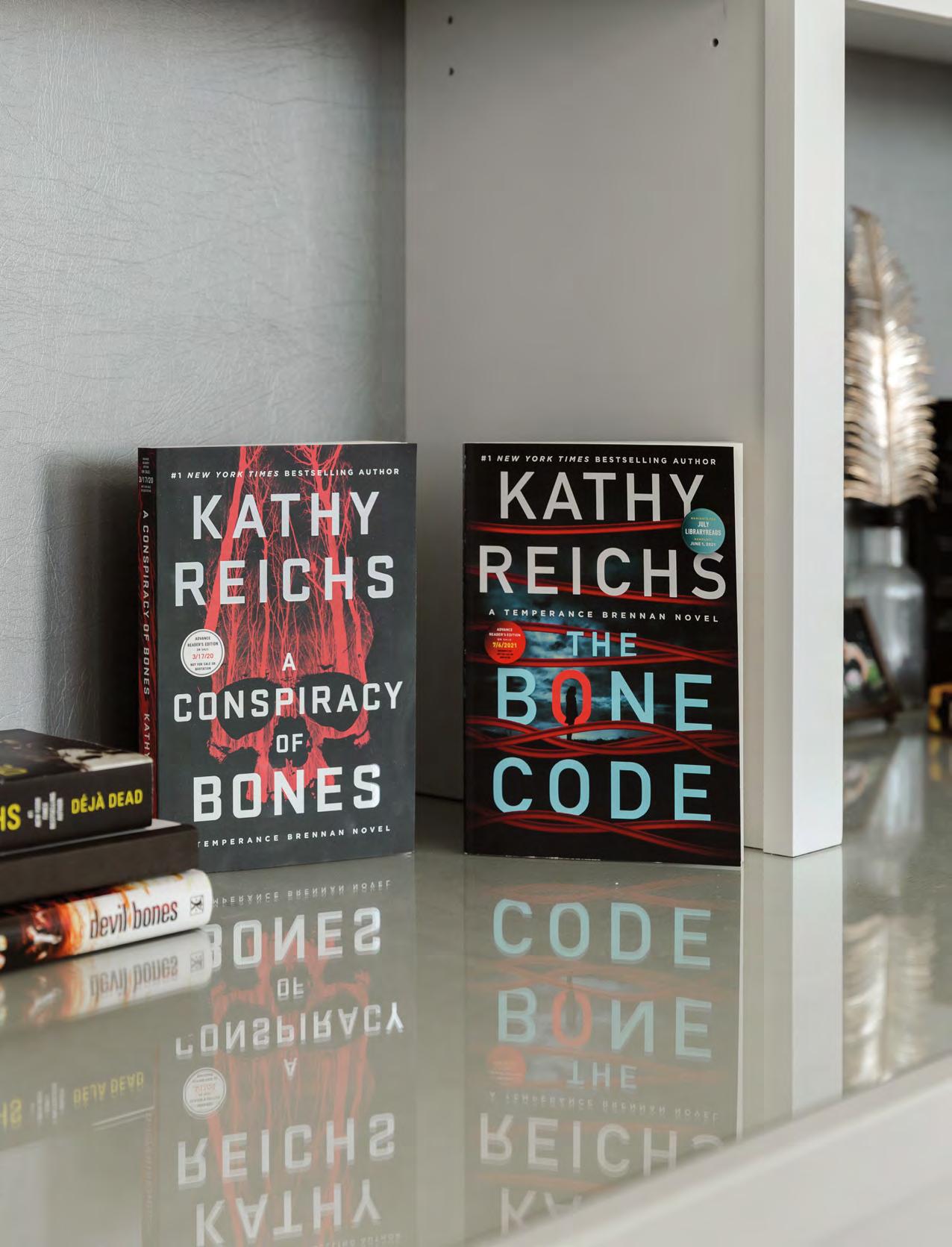

92 | NO BONES ABOUT IT

Meet Dr. Kathy Reichs, a forensic anthropologist and academic turned New York Times bestselling crime writer. By Jennifer Pattison Tuohy

98 | TWENTY YEARS OF ART ON THE ISLAND

Discover how Julie Cooke turned a vacation into a career running Sullivan’s Island’s only art gallery.

By Carol Antman

GUIDE

22 | WATCH FOR WILSON’S

Meet the tiny shorebirds whose Oscarworthy antics are a unique survival tool.

By Judy Drew Fairchild

26 | THE MARITIME FOREST’S MEDICINE WOMAN

Botanist April Punsalan takes us for a walk through Sullivan’s Island’s very own herbal pharmacy.

By Zach Giroux

30 | STINGING SENSATION

Learn about the jellyfish that frequent our beaches and discover why Portuguese Man-of-War deserve your attention.

By Kinsey Gidick

HISTORY SNAPSHOT

34 | PLACING THE PESTILENCE HOUSES

New research reveals more about Sullivan’s Island’s four pest houses and their role in the forced exodus of West Africans to the New World.

By Brian Sherman

38 | FORE SCORE AND ONE GOLF COURSE AGO

Nearly 100 years ago, the Army built a golf course on Sullivan’s Island to provide officers and enlisted men with some R&R. Where did it go?

By Brian Sherman

ISLAND LIFE

Explore what makes life on our islands spectacular places to visit and special places to live

34 | A TIMELESS CRAFT THAT’S STILL ADRIFT

Explore the nautical pastime of wooden boats, a Southern staple that lives on for a small crowd of aficionados on the islands.

By Zach Giroux48 | PRESERVING ISLAND LIFE

Father Lawrence McInerny sat down with the Battery Gadsden Cultural Center to tell the tales of his family’s four generations on the island, helping keep our history alive.

By Kinsey Gidick

SIP SALUTES

Dive into the local personalities that make our islands so unique

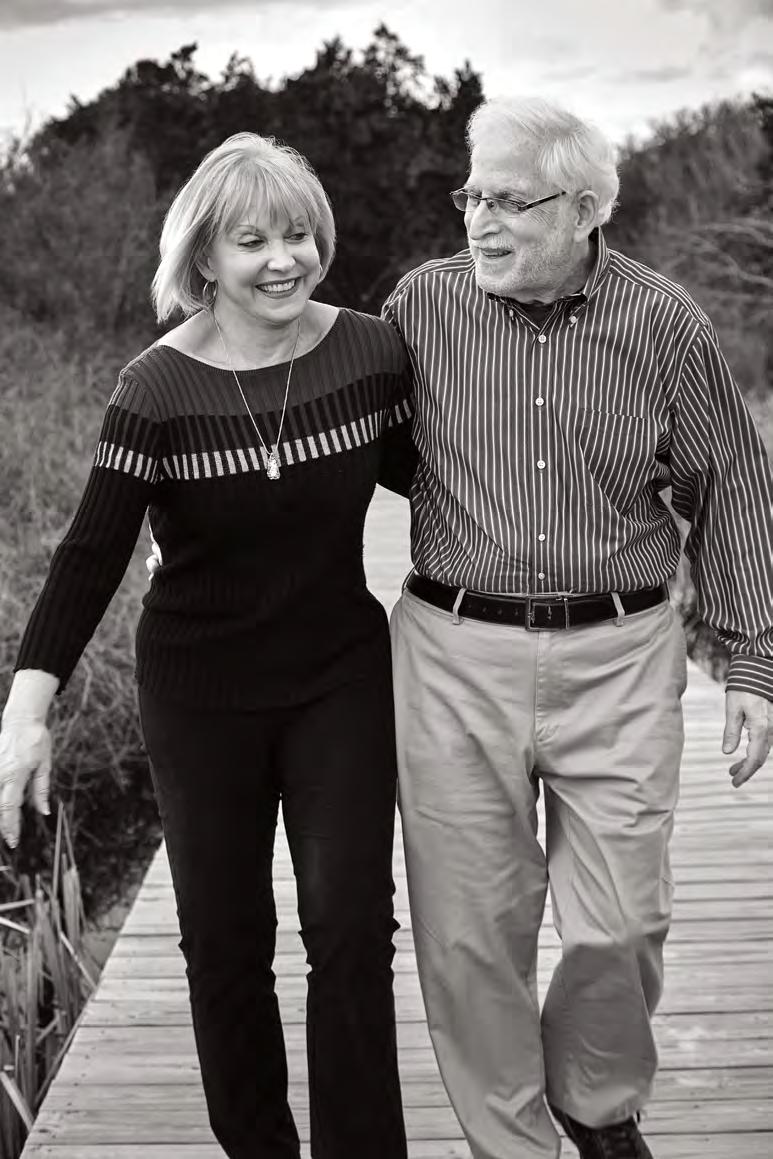

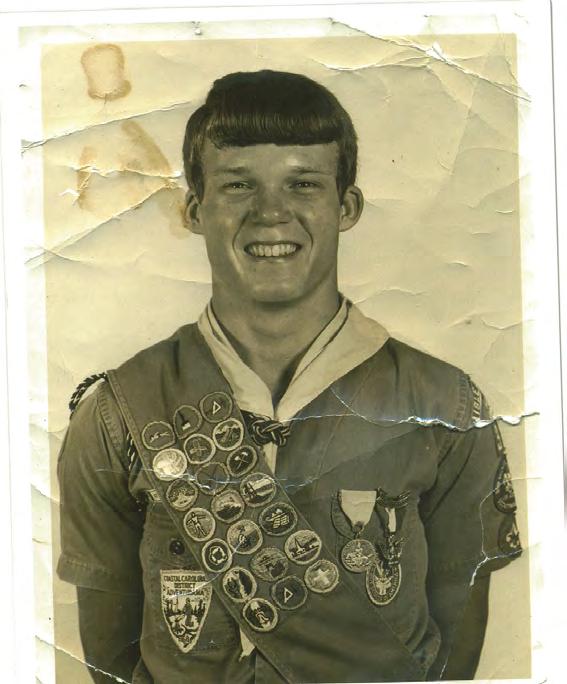

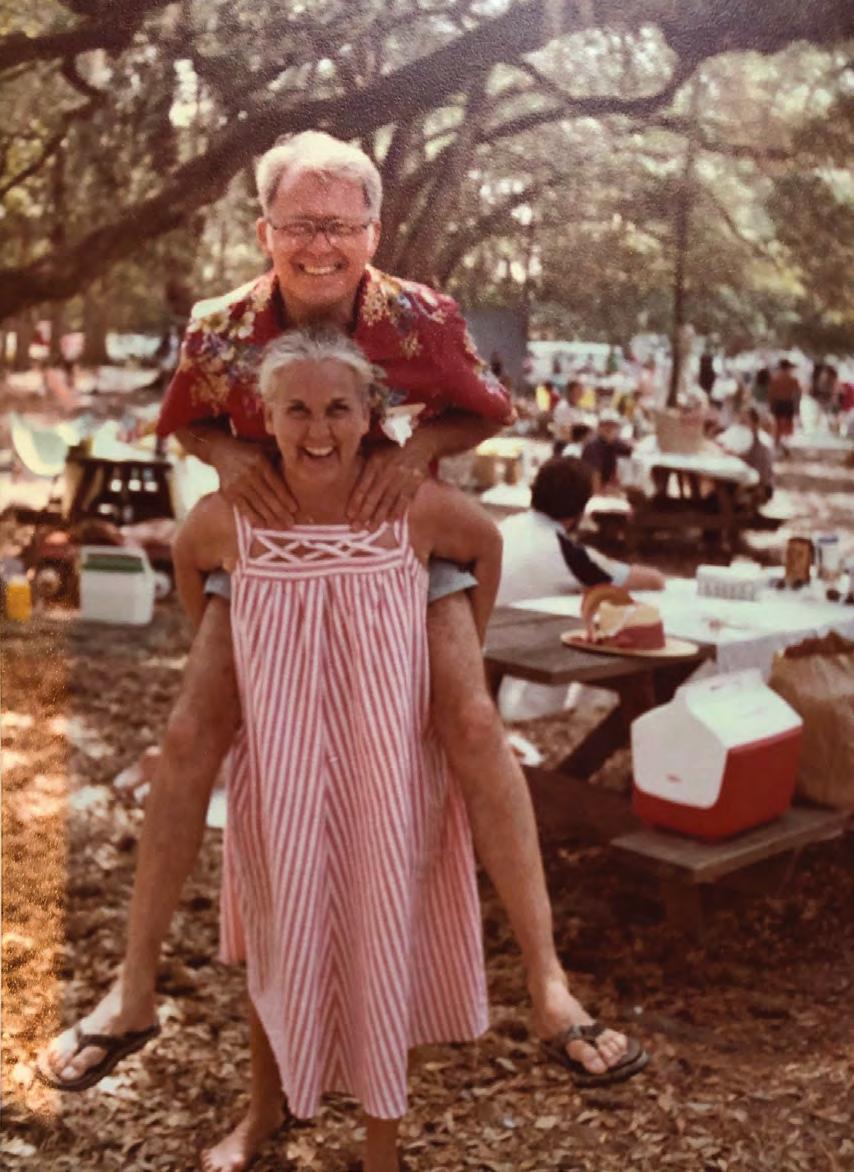

54 | LIVES OF SERVICE

Jerry and Cheryl Kaynard are dedicated to improving and helping those less fortunate.

By Colin McCandless

60 | FOLLOW THE LEADER

Sullivan’s Island Elementay School’s crossing guard is inspired by faith to serve as a community ambassador. By Colin McCandless

64 | MEET SULLIVAN’S UNOFFICIAL MAYOR

Every community needs a welcome committee, and on Sullivan’s that job belongs to Leo Fetter.

By Marci Shore

68 | ‘WE’RE SULLIVAN’S ISLANDERS’

Born and raised on Sullivan’s Island, 92-year-old Doris Lancaster looks back on a life full of sand spurs, smiles, and soldiers.

By Marci Shore

e rising tides of creators and companies new on the scene

106 | NOT YOUR AVERAGE JOE

Ann Hutson and Kevin Hartley on their budding coffee pod business.

By Meghan Daniel

108 | CARVING OUT A BUSINESS

William Rocco and Brock Webb open up a woodworking shop in their spare time. By Meghan Daniel

110 | PROMISE AND PUPS

Amy Scarella has dedicated her life to rescuing last chance dogs.

By Meghan Daniel

A er you’ve soaked up the sun, explore other activities islanders enjoy in their downtime

112 | ON THE PLUS SIDE

The main dish isn’t the only star at island restaurants. These sides often steal the spotlight.

By Stephanie Burt

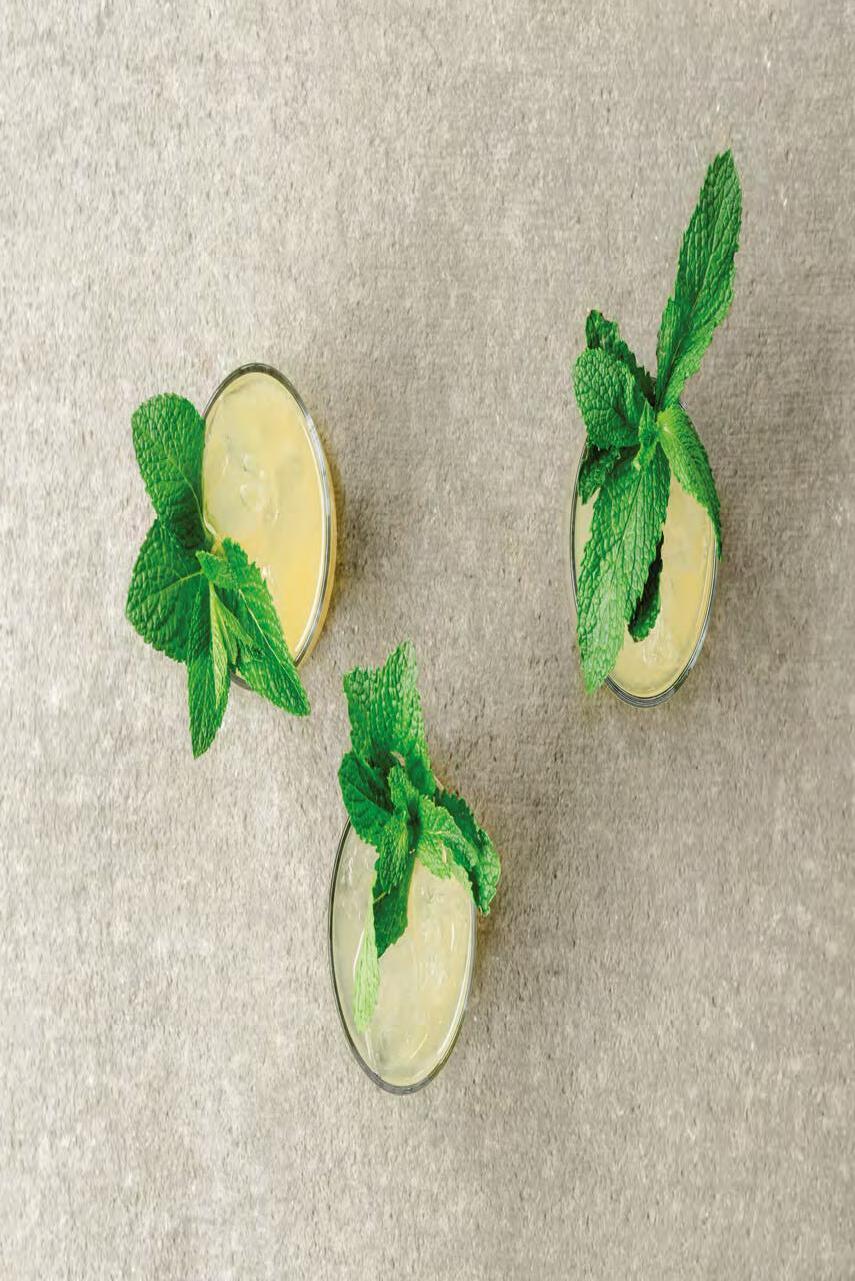

120 | CHEERS TO THESE

Five local bartenders reveal the best beachside cocktails to sip this season.

By Margaret Pilarski

126 | VIBES & VOCALS

Who, what, and where of live music venues on the islands—there’s more t han enough to go around

By Marci Shore

128 | SIP CALENDAR

Your essential guide to island events

This past year has been one for the history books, as they say. But in any time of turmoil you can nd triumph in the face of adversity and hope in the sight of struggle. In our main feature story, in this the seventh annual issue of SiP magazine—which celebrates life on the beautiful barrier islands of Sullivan’s, Isle of Palms, Dewees, and Goat—we sought to tell some of those stories.

Pandemic Pivots (page 76) explores six islanders’ personal and professional struggles through the challenging landscape of the last 18 months. Most of all it reveals how very important their island community was to each of them in helping them make it through.

Community is o en a key to success, which is something that shines through in our story on the Isle of Palms Marina (page 84), a true gathering place built by the people of the island for the people of the island. On Sullivan’s it was the community of artists that helped Julie Cooke create an art gallery out of a sandwich shop that—to everyone’s surprise, including her own—is still going strong two decades later. Read the story of Sandpiper Gallery in 20 Years of Art on the Island (page 92). en meet one of our islands’ most fascinating authors in No Bones About It (page 98), an interview with Dr. Kathy Reichs whose 20th Temperance Brennan crime novel is released this July.

Also within the magazine, we celebrate some of the people who make our islands a community. From Jerry and Cheryl Kaynard who strive tirelessly through their political and legal work to make life better for those less fortunate and Walter Sherrill who is responsible for the safety of our children every morning as they walk to school, to Leo Fetter, the friendliest man on Sullivan’s, and Doris Lancaster, one of the last, original islanders.

SiP’s mission is to celebrate our communities, and we hope that reading these stories will remind you what a wonderful community you are a part of… whether you’re here for a few days or for a lifetime.

Jennifer Pattison Tuohy Editor-in-Chief

Lynn Pierotti Publisher

Jennifer Tuohy

Editor-in-ChiefAlejandro Ferreyros

Art Director

Kinsey Gidick

Deputy Editor

Rob Byko

Photographer

Swan Richards

Ad Designer

Lori McGee, Marci Shore

Advertising Executives

Contributors

Carol Antman

Michael Barnett

Stephanie Burt

Meghan Daniel

Josie Derrick

Judy Drew Fairchild

Zach Giroux

Minette Hand

Hastings Hensel

Colin McCandless

Vincent J. Musi

Margaret Pilarski

Hector Salazar

Brian Sherman

Marci Shore

Mic Smith

Mark Stetler

www.sipmagazinesc.com

Instagram / Facebook @SiPMagazineSC

About SiP

SiP magazine is published annually by Lucky Dog Publishing, LLC., 2205 Middle St., Sullivan’s Island, SC. SiP is mailed to all property owners on Sullivan’s Island, Isle of Palms and Dewees Island, and distributed free at select locations.

Contact SiP

tel. 843.886.6397

mailing address: po box 837 Sullivan’s Island, SC 29482 for editorial inquiries jennifer@luckydognews.com for advertising inquiries lynn@luckydognews.com www.luckydognews.com

Cover Photo by Michael Barnett

Copyright 2021

Carol Antman is driven by creative curiosity. Her passion for travel has led to living on a kibbutz, hitchhiking the Pan American highway, vagabonding in Europe and Central America, and camping throughout the U.S. She now lives on Sullivan’s Island and as a travel writer, she is inspired by the idea that everyone has a story.

Michael Barnett grew up in the Lowcountry, spending his childhood exploring the marsh behind his house, surfing the beaches, and going to grade school in downtown Charleston. He has traveled extensively, documenting it from an early age. He shares his love for wildlife through his work as a photographer on Instagram @ TheMilkyWayChaser.

Stephanie Burt is the host and producer of The Southern Fork podcast and a writer based in Charleston. She is a frequent contributor to Saveur and her

work has appeared in numerous other publications, including The Washington Post, CNN's Parts Unknown, Conde Nast Traveler, and Atlas Obscura

Rob Byko is a photographer and Realtor at Byko Realty, an agent of ERA Wilder Realty. An environmentalist at heart, Rob hopes his art inspires a protective spirit in others. Rob and his wife Karen live on Sullivan’s Island with their two rescue boxers.

Meghan Daniel is a South Carolina native and graduate of Wofford College with a passion for storytelling. She lives in Mount Pleasant where she is pursuing a career in journalism or communications. Through writing for The Island Eye News, Meghan has developed a fond familiarity with the islands.

Josie Derrick is a lifestyle and brand photographer calling the Lowcountry home. She works with makers, creatives, and small business owners to tell their stories.

Judy Drew Fairchild is a Coastal South Carolina Master Naturalist and former middle school teacher who loves teaching and learning about the natural world. She’s served on the Board of Directors of SC Audubon, the Dewees Island Conservancy, and the Lowcountry Biodiversity Institute. She lives full-time on Dewees Island.

Kinsey Gidick is a freelance writer and frequent contributor to Charleston Magazine, Garden & Gun, and Romper.com. Her work has also appeared in Alaska Air Magazine, The Washington Post, McSweeney’s, and The New York Times

Zach Giroux is a journalist for several Lowcountry publications, who transplanted to Charleston from a small town in Vermont. He is a general assignment reporter who covers all things from breaking news to community lifestyle pieces.

Minette Hand is an author and photographer specializing in

interior and portrait photography. Her most recently published book Present, In This Way, covers a roundtrip photo adventure from the East Coast to Montana and Wyoming. It can be found locally as well as on her website minttehand.com.

Hastings Hensel is a freelance writer and teaches writing at Coastal Carolina University. He is the author of two poetry collections— Ballyhoo and Winter Inlet —and a graduate of Johns Hopkins and Sewanee. He lives with his wife, Lee, and their dog, Huck, in Murrells Inlet.

Colin McCandless is a freelance writer based in West Ashley. He has extensive experience writing for magazines and newspapers and developing online content. He writes for Charleston Magazine, Charleston Style & Design, HealthLinks Magazine, and Metro Magazine, among others.

Margaret Pilarski grew up around the country but has lived in Charleston for over a decade now. Her editorial work

frequently features artists, activists, educators, and entrepreneurs. When she’s not exploring the islands for SiP, she directs brand strategy and content at Outline, a creative studio.

Hector Salazar has three decades in the video/ photography business. He works with mid to large-sized companies as well as high profile VIP's. His company MeanStream Studios prides itself on making its clients' vision reality. See his work at meanstreamstudios.com.

Brian Sherman is a freelance writer, editor and graphic designer. A native of Philadelphia, he graduated from Memphis State University and landed in the Lowcountry the day before 9/11. Back when he had a real job, he was the editor of three different newspapers and a national magazine. He lives in Mount Pleasant with his wife, Judy, and their dachshund, Jelly Bean.

Marci Shore has lived in the Lowcountry for 11 years and has written for SiP since

2015. A Sullivan's local, she is owner of Ma’ Formulas Hemp Topicals, an agent with Sand Dollar Real Estate, and a singer/songwriter, fiddler with various local bands.

Mic Smith was thrilled to capture the people and activities around the Isle of Palms Marina with his camera, given it's one of his happy places. An Isle of Palms resident for a quarter century and an active boater for nearly a decade, Smith often launches from the marina, and otherwise loves to stop by for treats and conversation.

Mark Stetler has worked as a photographer for twenty plus years. Born in Cleveland, he studied photography at the Art Institute of Atlanta, moving to New York in 1993 to attend NYU. While in New York he assisted many of the world’s most respected photographers, such as Mary Ellen Mark and Richard Avedon. He currently shoots for clients worldwide while based on the Isle of Palms.

Meet the tiny shorebirds whose Oscar-worthy antics are a unique survival tool.

Story and photos by Judy Drew Fairchild

You may be familiar with the sight of small sanderlings that run with their feet in the waves, but there is a sandpiper-like bird that hides in plain sight right on the beach. Wilson's Plovers, Charadrius wilsonia , are small stocky shorebirds with an erect posture and a ringed neck, and they nest right on the ground in the dunes and overwash areas of the beach. You might nd them standing on dri wood watching you and making a peeping call, or you might encounter one that seems to be hurt, dragging a broken wing in the sand.

Watch where you step, especially if you are in the dunes where there are natural grasses or lots of tiny shells.

Stay closer to the water than the dunes, especially in the heat of the day.

Time your walk for low tide, especially if you have a dog with you: it gives nesting birds more room to roam the beach.

Leash your dog. Even leashed dogs can decrease bird diversity by 50 percent because birds don't understand that the dog is not a predator. Unleashed dogs chase birds by instinct and can harm the tiny shorebirds unintentionally.

If you see a bird faking an injury, freeze in place and carefully back out of the area.

For more information and to see Judy’s Wilson's Plover Nature Walk video go to naturewalkswithjudy. com/2020/05/11/wilsons-plover/

Long-time Dewees Islander, former middle school history teacher, and South Carolina Master Naturalist, Judy Drew Fairchild, has used some of her time in quarantine on Dewees to create a series of nature videos. A welcome distraction in these trying times, the project combines Judy's gift for teaching, love of nature, and passion for conservation. It is a love letter to the natural diversity of the Lowcountry.

The videos, “Nature Walks with Judy,” are designed to spark interest, engage curiosity, and, through knowledge and understanding, invite people to care about conserving nature in their own backyards. Each video is about one minute in length, making it ideal for all ages and combines Judy’s fabulous photography and unique videos with her bountiful knowledge.

The topics of these videos move from birds and trees to the wonders you can find in tidal pools, prompting you to look up and look down and find a new fascination in the natural world all around you. “There are tiny miracles taking place around us all the time, if we stop and look,” says Judy. “My goal is to get people to notice those, and grow to love the nature around us. Once you love something, you’ll be more invested in protecting it.”

Go to www.NatureWalksWithJudy.com to watch the videos and to connect with Judy on social media.

— Carey SullivanOpposite page: From top, a Wilson’s Plover on its nest; the uncovered eggs; a Plover and its chick foraging for food. Below: A young Wilson’s Plover ventures out.

Living only in southern coastal areas, with a particular penchant for barrier islands, Wilson’s Plovers nest on South Carolina beaches through the spring and summer. ese brown and white birds, who are named a er the Scottish-American ornithologist Alexander Wilson, feed on ddler crabs and choose open areas of sandy islands and inlets to lay their eggs, o en near dune edges.

Nesting season begins in late April and is usually nished by mid-July. South Carolina has approximately 375 pairs of nesting Wilson's Plovers and the bird is listed as state-threatened. ey are in decline because so much of their habitat is crowded with beachgoers. Additionally, warming temperatures in the spring pose a danger to chicks in the nests.

Wilson’s Plovers don’t build nests from sticks; rather they lay their speckled eggs directly on the sand and crushed shell. When the eggs hatch, the young birds are adorable balls of u that can run within hours of hatching, seeking shelter under their parents wings or freezing in place right on the sand. Nests and chicks can be almost impossible to see on the beach, making humans the major threat to this species.

When nesting adults perceive a threat, they may jump o their nest and fake a broken wing in an attempt to lure the “predator” away from a nest or youngsters. Unfortunately, eggs and chicks can bake in the hot sun in a few short minutes.

If you see a bird that looks like it’s injured, and it is peeping at you and trying to get your attention, look closely—there is probably a nest with eggs or chicks nearby. Freeze and retreat carefully so as not to step on chicks or eggs. e next time you’re at the beach, keep an eye out for these tiny friends, and give them lots of space.

Botanist April Punsalan takes SiP for a walk through Sullivan’s Island’s very own herbal kitchen.

By Zach Giroux Photos by Rob Byko

Scan this QR code to see a video of April Punsalan and SiP Publisher Lynn Pierotti on a medicinal walk through the Maritime Forest.

When April Punsalan walks through the Sullivan’s Island Maritime Forest at the Station 16 beach access path, she uses it di erently than most beachgoers. She shops the ora with a basket in hand as if she were at the Farmers’ Market.

A botanist, ethnobotanist, herbalist and self-proclaimed “plant whisperer,” Punsalan specializes in the study of edible and medicinal properties that plants hold. Her passion for foraging stemmed from a desire to protect plant diversity from a young age, which has sprouted into a lifetime pursuit for free herbal remedies that can be found in nature’s bounty.

Punsalan’s top-five most medicinally beneficial plants that can be found in the Maritime Forest

Yaupon (Ilex vomitoria)

Use - Caffeinated tea

How to apply - Tea

Native - Southeast Coastal Plain

Where it grows - Maritime forests

Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana)

Use - Antimicrobial (relieve a sinus infection)

How to apply - Steam facial, incense/smudge

Native - Eastern United States

Where it grows - Maritime forests, old fields, roadsides

Wax Myrtle (Morella cerifera)

Use - Astringent and diuretic

How to apply - Tea and bath

Native - Endemic to the Southeastern Coastal Plain

Where it grows - Maritime forests, pocosins, marshes

Carolina Willow (Salix caroliniana)

Use - Anti-inflammatory, Fever Reducer

How to apply - Tincture, tea/decoction

Native - Southeast Coastal Plain

Where it grows - Interdune ponds, riverbanks, sandbars

Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides)

Use - Anti-inflammatory

How to apply - Make a decoction for the bath

Native - Southeastern Coastal plain

Where it grows - On branches of trees

For more information about Punsalan’s teachings, herbal recipes, infusions and decoctions for all ages, visit courses.yaholaherbalschool.com/courses/foragenow.

Punsalan’s a nity for plants evolved during a horticulture class at her high school in Norfolk, Virginia. She would go on to become president of the Future Farmers of America and compete in state fairs with selfmade herbal soap and shampoo at the age of 16. A erward, Punsalan got her master’s in botany from Western Carolina University and worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

A er immersing herself in the eld for the past 24 years, Punsalan decided it was time to enrich the minds of others who share a similar love for plant life. Last August, Punsalan launched Yahola Herbal School to help people connect with the “green friends” one needs for health, vitality and wellness.

Punsalan’s course is called Forage Now but she’s considering changing it to Forage Everyday. For her, foraging is much more than just an act of obtaining nature’s nutrients, it’s a way of life. “ e more that I forage and connect with these plants the more I understand their medicine and how they work on my body and then I can teach you better,” Punsalan says.

When Punsalan teaches people about plants’ medicinal o erings, she purposely focuses on the most common ones and stays away from the rare ones because she is very much a conservationist. She’s also very cautious about using the word heal. Heal is a word that the Federal Drug Administration doesn’t like people such as Punsalan to use when it comes to associating plants and medicine. In terms of selling herbal products, the word “supports” is more appropriate, she says.

Historically, in the late 1800s botanists were medical doctors who would go out and harvest for their patients. Punslan idolizes the work of Francis Peyre Porcher, a well-respected South Carolinian who authored several works on the medicinal properties of plants and joined the Confederate Army as a surgeon during the Civil War. Punsalan credits Porcher for inspiring her to be the “medicine woman” that she is today.

When Punsalan was a child, she su ered from a urinary tract infection. Raised by a single mother of three, her family didn’t have health insurance nor the nancial means to cure it. Punsalan took matters into her own hands and administered a plant called Rattlesnake Master. “I’ve healed myself from things that doctors couldn’t gure out,” Punsalan says. “ ey were still prescribing me antibiotics and I just went out into the forest and harvested something, chewed on a root for a day and it was gone the next day.”

Years later, as a mother, she helped her daughter’s strep throat with herbal remedies. She believes the plants that grow in ecosystems like the Maritime Forest can be more e ective than pharmaceuticals in some cases. Punsalan says that for conditions such as a sinus infection, urinary infection and even kidney stones, she has found that plants can

o er relief similar to generic over-the-counter drugs.

In October 2020, a decade-long legal dispute concerning the Maritime Forest reached a resolution in favor of accepting a settlement that will see more cutting in the forested area. e approved agreement permits the clear-cutting all vegetation within 4 feet of a town-owned beach path, cutting all vegetation in a 100-foot strip next to residences with the exception of mature palmettos, live oaks and magnolias; and limbing mature trees

and removing smaller trees, including cedars, pines and hackberries.

Punsalan is concerned this will provide an opportunity for non-native plant species to overtake native species, due to the exposure of more sunlight. However, she pointed out that it will also increase species’ diversity by creating more openness. “You want spatial and temporal heterogeneity,” Punsalan says. “You want to create patches, so there could be a win-win.”

Meet the jellyfish that frequent our beaches and discover why the Portuguese Man-of-War deserve your attention.

By Kinsey Gidick by Michael BarnettDid you know the venom from bees and wasps poses a bigger public health threat than that of jelly sh? And yet jelly sh continue to be vili ed. As lovely as they are to look at from the safety of a place like the South Carolina Aquarium—home to Moon Jellies and Lion’s Main jelly sh—hit the beaches and the welcome isn’t so warm. We’ve been trained to fear these marine animals whose sting can send shivers down the spine of an unsuspecting swimmer.

Also known as jellyballs, these jellyfish are the most common in our area. During the summer and fall, large numbers appear near the coast and in the months of estuaries. Fortunately, while the cannonball is the most abundant jellyfish in the area, it is also one of the least venomous. Cannonballs can be identified by their white bell shape, decorated with rich, chocolate brown bands. They have no tentacle but a gristle-like feeding apparatus.

Mushroom Jelly

The mushroom jelly is often mistaken for the cannonball jelly, but it differs in many ways. The larger mushroom jelly, growing to 20 inches in diameter, lacks the brown bands associated with the cannonball and is much flatter and softer. Like the cannonball, the mushroom has no tentacles. However, it possesses long, finger-like appendages hanging from the feeding apparatus. It doesn’t pose a hazard to humans.

Moon Jelly

Probably the most widely recognized jellyfish, the moon jelly is relatively infrequent in South Carolina waters. It has a transparent, saucer-shaped bell and is easily identified by the four pink horseshoe-shaped gonads visible through the bell. It typically reaches 6-8 inches in diameter, but some are known to exceed 20 inches. The moon jelly is only slightly venomous.

Also known as the winter jelly, the lion's mane typically appears during colder months of the year. The bell, measuring 6-8 inches, is saucershaped with reddish brown oral arms and eight clusters of tentacles hanging underneath. Lion’s manes are moderate stingers.

Frequently observed in South Carolina waters during summer months, the sea nettle jellyfish is saucer-shaped with brown or red pigments. It is usually 6-8 inches in diameter, with four oral arms and long marginal tentacles hanging from the bell. The sting of a sea nettle is considered moderate to severe and may be described as burning rather than stinging.

Known as the box jelly because of its cube-shaped bell, the sea wasp is the most venomous jellyfish inhabiting our waters. Its potent sting can cause severe dermatitis and may even require hospitalization. Sea wasps are strong swimmers reaching 5-6 inches in diameter and 4-6 inches in height. Several long tentacles hang from the four corners of the cube. A similar species, the four-tentacled Tamoya haplonema, also appears in our waters.

The Portuguese Man-of-War is not a "true" jellyfish. It typically inhabits the warm waters of the tropics, sub-tropics and Gulf Stream, but wind and ocean currents can propel them into nearshore waters of South Carolina.

Information courtesy SC Department of Health and Environmental Control. Photos courtesy of the South Carolina Aquarium.

The average jellyfish sting can be easily treated with vinegar, says Shannon Howard, a biologist at the South Carolina Aquarium. If a tentacle is stuck on you, do not touch it. Squirt the vinegar on it instead. “What that does is causes the stinging cells to retract, then you can safely remove it with something like tweezers,” she says. She also encourages regular beach swimmers to keep heat packs handy to place on the wound. “A heat pack will help the swelling and pain,” she says.

A Man o’ War sting is a different beast. Howard says that while they’re rarely deadly for humans, it’s best to be extra cautious if stung. It is very painful, and she advises going to the emergency room. “At the very minimum, go to your nearest urgent care,” says Howard, just to be safe.

But Shannon Howard, a biologist at the South Carolina Aquarium, says some of our fear is misplaced. “Yes, it's common to get stung, but it's also common to get stung by a bee and the majority of people are going to have a pretty mild reaction,” says Howard. When it comes to the average jelly sh swimming around the Isle of Palms and Sullivan’s—like cannonball, mushroom, and sea nettle jellies—we can all calm down a bit. “For some people the sting is nothing more than an annoying rash, but for others it is more painful,” she says of their inevitable sting. At worst, unless you’re allergic, you can expect a typical jelly sh sting to last several hours, with welts possibly lingering for a few weeks.

Portuguese Man-of-War, however, deserves your attention. In coastal Carolina the native Man-of-War stirs up all kinds of dramatic headlines each year. at’s because it packs the most painful punch of all our area’s tentacled creatures.

But, get this, it’s not actually a jelly sh. at’s right, a Man-of-War is a complex colony of polyps. ey don’t swim, they’re wind powered and propel themselves via a oat—a bulbous sail that sits above the water. at’s why you see them wash up on the beach a er a big storm or strong current. Even when it’s not windy, however, South Carolina swimmers should learn to identify these venomous

creatures because under that lovely purple oat dangle powerful tentacles. “ ey look like ribbon of curly red and they can be very long,” says Howard. “ irty feet is about the average, but they could be as short as six feet to as long as 165 feet.”

Step on or get swiped by one of those tentacles and you’re not going to be a happy camper. “We always tell people if you see one wash up on shore, or especially if you see one in the water, don't touch it. Do not get in the water,” adds Howard. is is especially important on our coast where the water isn’t clear and you may think you’re swimming in a safe spot when you’re really not.

Respect all jellies and they’ll respect you. SiP

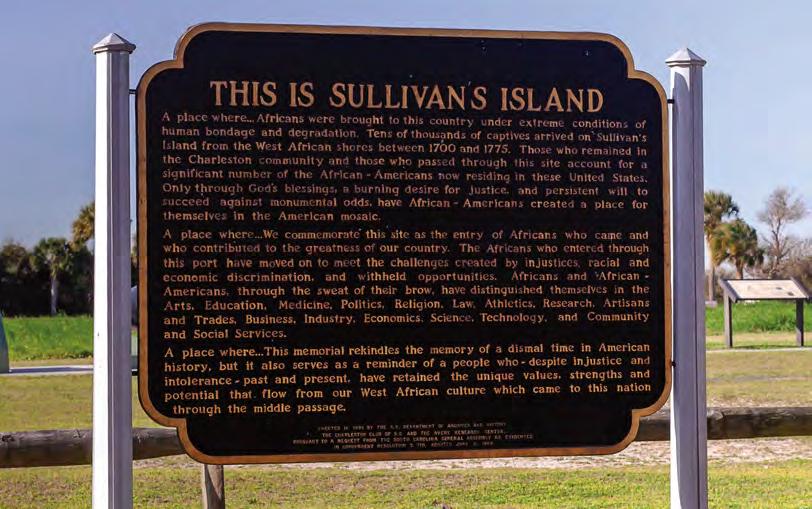

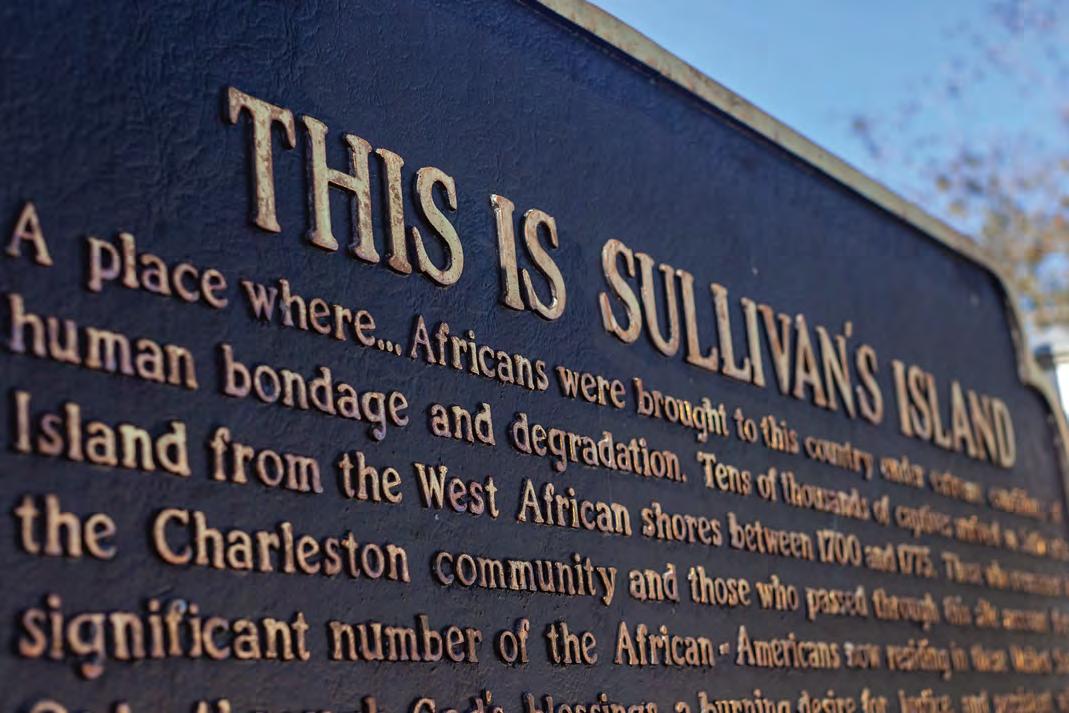

New research reveals more about Sullivan’s Island’s four pest houses and their role in the forced exodus of West Africans to the New World.

By Brian ShermanFor many years, local lore had it that every enslaved African who came to the New World through the port of Charleston rst spent time on Sullivan’s Island. It was thought the pest houses there served as a revolving door for hundreds of thousands of soon-to-be slaves who needed to be quarantined to protect the local population from smallpox, yellow fever, measles and other communicable diseases.

In reality, there is likely a gaping chasm between truth and ction concerning what actually transpired on the mostly uninhabited island between the beginning of the 18th century and the start of the 19th century, when the trans-Atlantic slave trade was abolished by the United States.

“ ere are so many misconceptions,” says historian and Charleston Time Machine podcast host Nic Butler, Ph.D., pointing out that little is known about the exact size or location of Sullivan’s Island’s four pest—short for pestilence—houses. “An idea that’s become popular is that Sullivan’s Island was the rst place Africans touched. at’s true for some but certainly not for all. at’s a story that started in the 1970s,” says Butler. “But the island is important in African American history. I’m not trying to undermine that.”

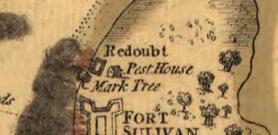

According to Butler’s research, the island’s four pest houses existed consecutively from 1707 to 1714; 1745 to 1752; 1755 to 1775; and 1784 to 1796. is means that, more o en than not, they weren’t a part of the quarantining process in place in Charleston from 1698 until 1808, when research shows approximately 40 percent of all enslaved people entering North America came through Charleston—between 150,000 and 200,000 people.

Not many people actually spent time in a pest house on Sullivan’s Island. Instead, a large number of those brought to America were quarantined aboard the ships that brought them to the New World. One reason for this, in addition to the fact that during more than half that time there were no pest houses at all, is the buildings were small and unable to accommodate a large number of people at one time.

Butler posits they were maybe capable of housing a dozen or so. In addition, a law that was in force from 1744 to 1784 required all ships carrying Africans to Charleston to anchor in the harbor for 10 days. During this time, a er spending four to eight weeks in dark, dirty quarters aboard a slave ship, many people were taken to Sullivan’s Island for a bath, fresh food, exercise, and new clothes so they would look healthier and bring a higher price once they reached the market in Charleston.

Sullivan’s Island’s role in the African American story

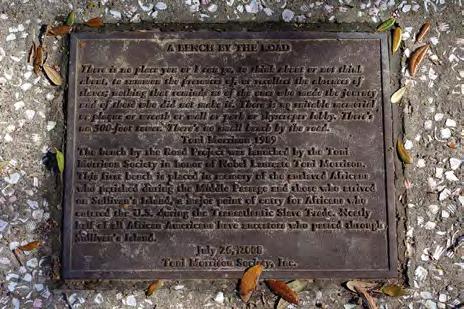

When the International African American Museum opens in Charleston next year, Sullivan’s Island’s role in the journey thousands of Africans endured will be part of the stories told there.

In 1980, when Michael Allen was hired by the National Park Service, the narrative of Africans stopping on Sullivan's Island on their way to being sold into slavery was no more than a small footnote in history. In 2022, the details of their journey will be available for all to see.

Allen helped bring this story to light through exhibits on the Sullivan’s Island pest houses at the Fort Moultrie VNPS Visitor Center. He was also tasked with helping establish a marker commemorating the slave trade near Fort Moultrie, as well as the commemorative Bench by the Road. “I saw the relevancy and importance of a history that needed to be told and brought to life,” Allen says.

The mission of the International African American Museum is to tell the story of “the journey of millions of Africans, captured and forced across the Atlantic in the grueling and inhumane Middle Passage, who arrived at Gadsden’s Wharf in Charleston, South Carolina, and other ports in the Atlantic World. Their labor, resistance and ingenuity and that of their descendants shaped every aspect of our world,” states the museum’s website. “There is a direct tie,” Allen noted. “We live in the Gullah Geechie Cultural Heritage Corridor. Without an acknowledgement of what happened on Sullivan’s, that does not exist.”

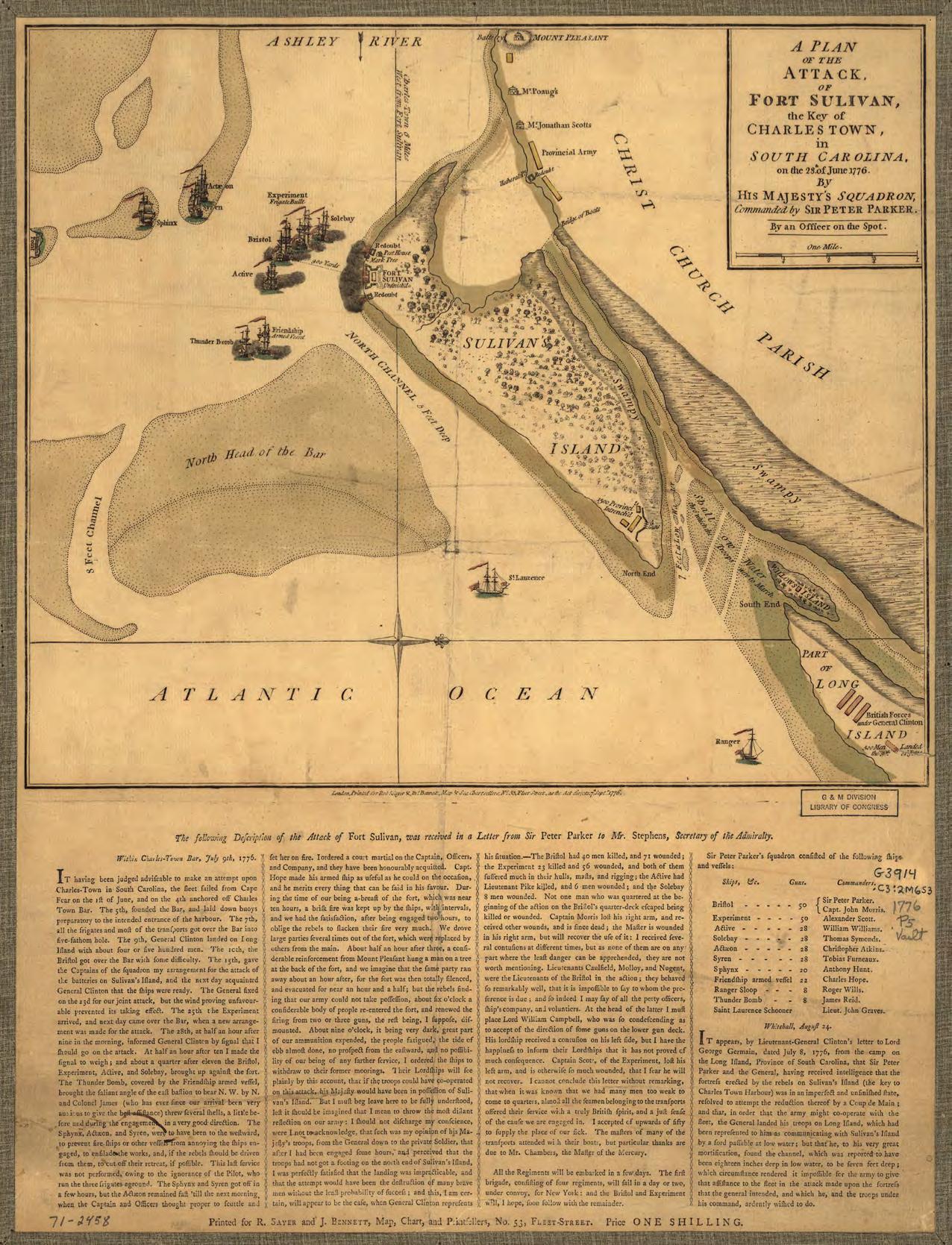

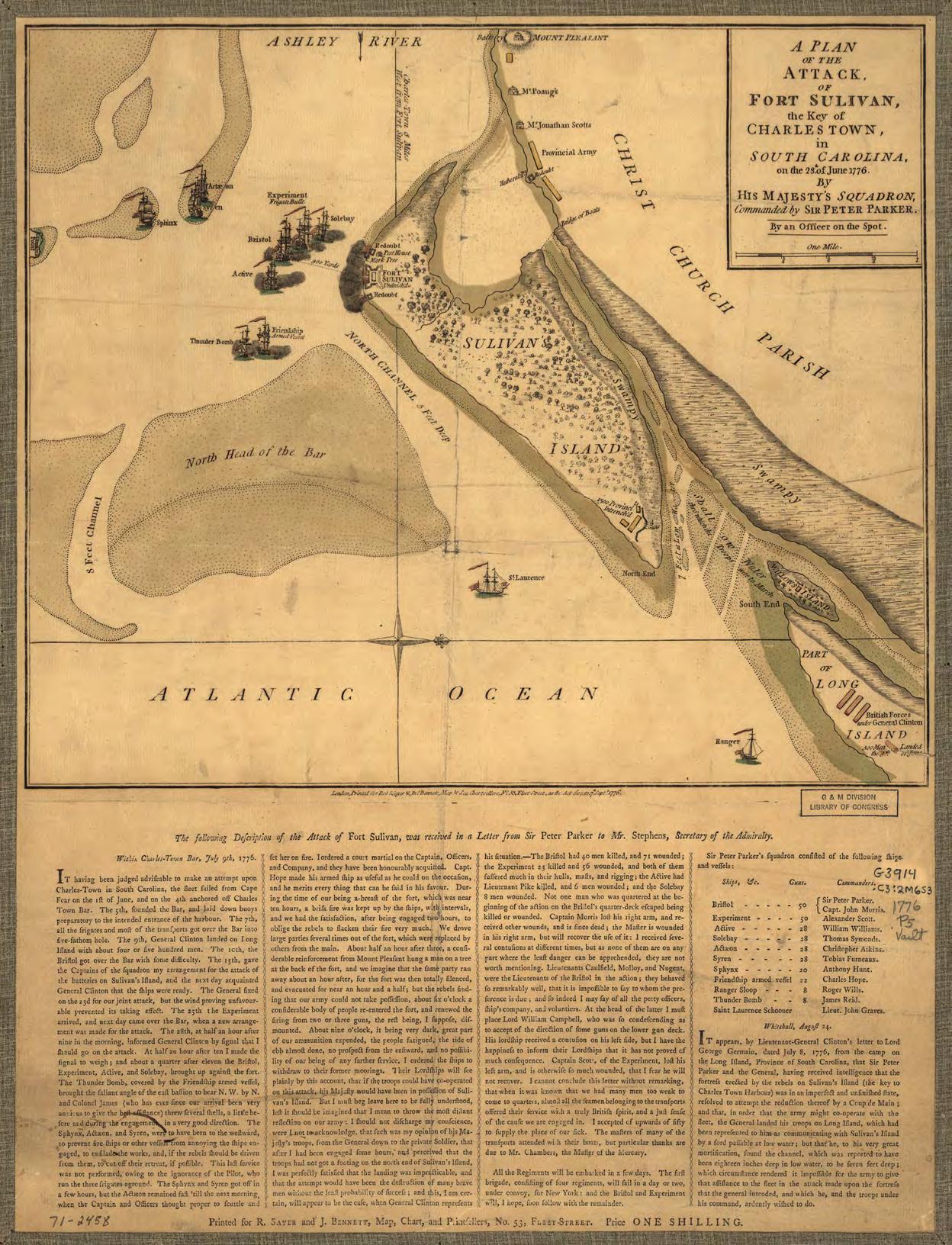

Opposite page: A map drawn in 1776 depicting the Battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28. In the center (enhanced) is a marker for a pest house. This is the only known map showing its location. (Map courtesy the Library of Congress)

ose enslaved people suspected to be contagious were relegated to a pest house and remained there until a physician—who visited only periodically—decided they were healthy. Or until they died. No graves have been found. “We do not know if there were burial grounds or if bodies were taken to sea and released into the waters,” says Elaine Nichols, curator of culture with the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, D.C.

Historian Michael Allen, a former employee of the National Park Service and the driving force behind the creation of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, says that based on the customs of the time, “they were most likely thrown into the harbor.” Butler says there are no records describing three of the four pest houses, though it is known that a facility destroyed by a hurricane in 1752 was a windowless, four-room brick building. “It was just a shell with a roof and probably cots and replaces,” Butler says. “It wasn’t a comfortable place. It was in some respects a death house or a continuation of being in the hull of a ship,” Allen adds. “It wasn’t a medical center. It was just to hold the cargo. At the end of the day, those people were just a part of the manifest of that ship.”

e experts disagree on what became of Sullivan’s Island’s four pest houses and where they stood. Allen suggests they were in locations that now are underwater in Charleston Harbor, while Butler believes the last pest house was converted into a restaurant. According to Nichols, the property where Grace Episcopal Church once stood on Station 14 was sold to the church near the end of the 18th Century, so could have been one location.

Regardless of where the pest houses were located, Nichols points out that legend, and even some historians, have misrepresented their main purpose. She said state law required the pest houses to be maintained to house enslaved Africans and contain the diseases they supposedly were bringing from across the Atlantic Ocean. However, local medical and governmental leaders and private citizens were more concerned about their safety than about race. She believes whites as well as Blacks spent time in pest houses.

“ e reality was that the people of Charleston recognized the certainty that they were just as likely to die of contagious diseases from white passengers from domestic or international ports of call as from diseases from Africa,” she says. “In the end, survival and not race determined who was placed into quarantine on Sullivan’s Island. If a person had smallpox, yellow fever, or measles, they wanted those persons placed in isolation so that they would not spread the diseases.”

“Charlestonians’ fear of diseases borne by Africans may have been the impetus for building pest houses on Sullivan’s Island, but what motivated them to place people in quarantine was the presence or potential presence of deadly diseases,” she adds. “Pest houses were used for the isolation of all racial and ethnic groups.” Her extensive research has not uncovered any instance of segregation based on race at Sullivan’s Island’s pest houses.

As the trans-Atlantic slave trade diminished and nally died in the early 19th century, memory of Sullivan’s Island’s pest houses faded as well into the deep, dark and mysterious corners of unwritten history. e legend found new life 165 years later, but much of the story still remains a mystery.

Nearly 100 years ago, the Army built a golf course on Sullivan’s Island to provide its officers and enlisted men with some R&R. Where did it go?

By Brian ShermanWherever you are in South Carolina, you don’t have to go far to play golf. But with more than 360 courses in the Palmetto State, you’d still be out of luck if you wanted to spend a pleasant Lowcountry a ernoon honing your driving skills or perfecting your short game on Sullivan’s Island, known more for its place in American history than for its lush fairways. at wasn’t always the case, though we don’t know for sure if undulating putting surfaces and di cult-tonavigate hazards were ever in play on Sullivan’s Island.

We do know that from the early 1930s until the U.S. Army lowered Old Glory at Fort Moultrie for the nal time in 1947, there was a golf course on the island that provided exercise and healthy competition among o cers and enlisted men alike. Women played there as well, as did civilians from area country clubs.

“PFC

Joseph M. Chevis was the course professional and greenskeeper. When he wasn’t taking care of his military responsibilities, he gave golf lessons, 50 cents for a half hour of instruction.

Not much is known about the course; even its number of holes is in question. According to Dawn Davis, public a airs o cer with the National Park Service, the course’s footprint ran from the current location of the Sand Dunes Club to Battery Jasper. e building that doubled as the golf shop and caddy house was located near the current intersection of Poe Avenue and Artillery Drive. And the layout of the course? Davis says the area doesn’t appear to be large enough for 18 holes, “but newspaper articles refer to 18 holes being played, so I would guess just nine.” However, in a 2013 thesis titled “Remembering the Legacy of Coastal Defense: How an Understanding of the Development of Fort Moultrie Military Reservation, Sullivan’s Island, South

Above: These photos of Battery Jasper (top) and Battery Logan (middle) show various angles of the presumed location of the golf course on Sullivan’s Island. The golf shop and caddy house (bottom) was a 144-square foot building with a 256-square foot porch. It was completed in November, 1938. (Photos courtesy The National Park Service)

Opposite page: A notice from 1941 regarding the golf course on Sullivan’s Island that was built in the early 1930s. (Courtesy The National Archives)

Carolina, Can Facilitate its Future Preservation,” Karl Philip Sondermann presented a di erent opinion. “With post expansion, golf club membership rose, enabling the construction of a one-hole golf course. Its fairway was in front of Battery Logan and its circular green placed in front of Battery Jasper,” his thesis pointed out.

According to newspaper clippings from the 1930s, the winning scores in tournaments and matches were in the 70s and 80s, so it’s logical to assume that golfers actually played 18 holes. Did they tee o from 18 di erent locations to a single green? e answer to that question might be buried in the annals of Lowcountry golf history.

e names of some of the better Fort Moultrie golfers of the 1930s are recorded in local newspaper articles. Sgt. Walter Mueller, eodoro Ciacoasa, Maj. Charles S. Johnson, Maj. Richard T. Edwards and Sgt. H.F. “Gabby” Hudson all won tournaments on the course, and trophies were captured by Maj. A.A. McDaniel, Lt. Moses Alexander, Mrs. Frederick R. Keller, Mrs. R.T. Gibson and Mrs. omas T. May. Johnson was credited with a hole-in-one on the course’s second hole. e newspaper also reported that Fort Moultrie golfers defeated a group from the Country Club of Charleston, but a few days later lost to the same team at the Wappoo course.

Questions about the course itself remain, but we do have a pretty good idea about the golf shop and caddy house and even a photo of the building. According to Army paperwork the 144-square-foot building—with a 256-square-foot porch—was completed on Nov. 5, 1938. It was equipped with electricity and water and sewer connections and was built with salvaged materials.

A “Golf Notice” released by Maj. S. J. Adams on March 4, 1941, detailed that o cers were entitled to use the golf course for free, while enlisted men could play for a fee of $1 per year, as long as they could demonstrate to a member of the Enlisted Men’s Golf Committee, “their knowledge of the game, including proper use of clubs and the rules and etiquette of the game, with a view to safeguarding the course through proper usage of the tees, fairways, sand traps and greens.”

e committee included Mueller, Sgt. Claude L. Lynch and PFC Joseph M. Chevis. e letter designated Chevis, a golf pro in civilian life, to be the course professional and greenskeeper. When he wasn’t taking care of his military responsibilities, he was permitted to give golf lessons, charging up to 50 cents for a half hour of instruction.

So, what happened to the golf course a er the military packed up and le Sullivan’s Island shortly a er the end of World War II? “We do know that the area in front of Jasper was le to grow wild pretty quickly a er the war, and then development on Sullivan’s Island took care of the rest,” Davis explains. “So, probably by the very early 1950s, the area was developed over.”

VEHICLES WITH LARGE SEATING CAPACITY STREET LEGAL FOR DAY OR NIGHT

APPROVED FOR RENTAL WITHIN WILD DUNES, KIAWAH & SEABROOK 25MPH/SEATBELTS PROVIDED

Wooden boats on Lowcountry tides go together like pimento cheese on bread. The nautical pastime is a Southern staple that lives on for a small crowd of aficionados on the islands.

By Zach GirouxThe “Sappho” is Hal Coste’s 1958 Simmons Sea Skiff. At 18-feet long, with a marine plywood and mahogany finish, this sturdy and lightweight boat was designer for a fisherman or to be an Army engineer’s workboat.

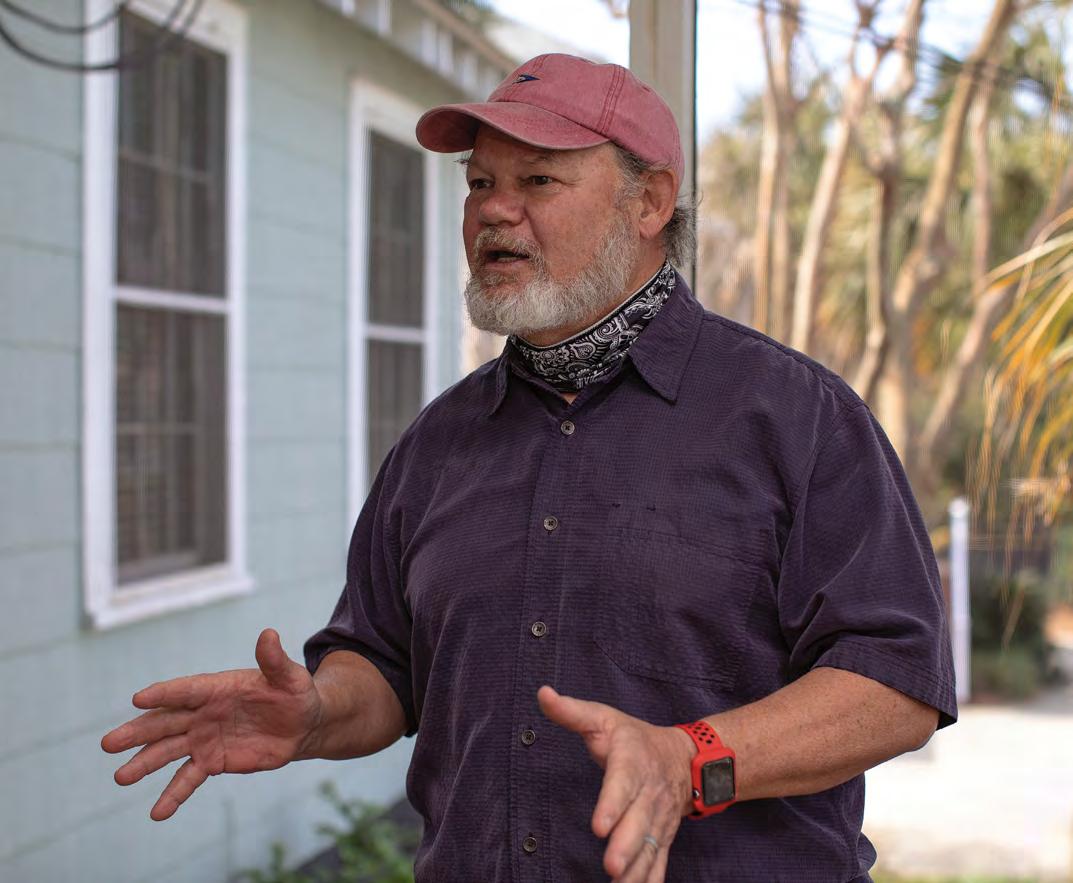

Hal Coste is one of the fortunate ones. A Sullivan’s Islander, Coste is a semiretired residential contractor and carpenter, and he’s also an award-winning wooden boat builder.

With all the modern materials available to make a boat, wood is chosen time and time again. Working with wood is well within the means of most people, the material is relatively easy to obtain and it’s not as labor intensive as other options. Built right, wooden boats are very strong, lightweight and do not fatigue. But for Coste, it’s a hobby, not a matter of business. Although, judging by his lineage, it appears the cra runs in the blood or atop the waves.

Coste hails from a long line of sea captains. His grandfather, Vincent O. Coste, was skipper of the local Coast Guard station. Vincent served in the U.S. Lifesaving Service, which joined with the Revenue Cutter Service in 1915 to form the U.S. Coast Guard.

His great-great grandfather, N. L. Coste, arguably committed one of the rst acts of piracy in the Civil War. He was not a swashbuckler but rather he commandeered the Revenue Cutter William Aiken in the Battle of Fort Sumter in April 1861, seizing the ship for the state of South Carolina. It was admitted as the rst o cial boat in the Confederate Navy.

Coste is no stranger to the water either. A former surfer, today his pride and joy is not a board, but Sappho and Scoota, his two wooden boats. In 2014, Coste heard through a friend about a free eBay listing of an abandoned boat that needed tender love and care. He jumped at the opportunity. Renting a workspace at Barrier Island Boatworks on Pherigo Street in Mount Pleasant and enlisting boat builder Teddy Hu , he got to work stitching and glueing it together. Stitch-and-glue is a simple boat building method that uses plywood panels stitched together, usually with copper wire, and glued together with epoxy resin. “I’m an old square and level carpenter. It’s got to be like that for me, but I learned a lot of lessons,” Coste says of his work on the boat renovation

A er sinking $13,000 of his own money into the endeavor, Coste watched his dream boat come to life right before his eyes. A 1958 Simmons Sea Ski , 18-feet long, green and white with a marine plywood and mahogany nish, he named it “Sappho” a er the ferry that ran between Charleston and Mount Pleasant at the turn of the century, of which N. L. Coste was the skipper.

From 1950 to 1970, Simmons manufactured approximately 1,000 of the Sea Ski s and Coste is fortunate enough to own one of the originals. Sturdy and lightweight, a Simmons boat design

Sullivan’s Island’s Hal Coste is a semi-retired residential contractor who is also an awardwinning wooden boat builder.

Sullivan’s Island’s Hal Coste is a semi-retired residential contractor who is also an awardwinning wooden boat builder.

Sullivan’s Island resident Fredrick Carl “Bunky” Wichmann Jr. with a miniature replica of a former boat named MOBJACK that he and his father once sailed. The original boat was a 1935 Francis Herreshoff design.

Sullivan’s Island resident Fredrick Carl “Bunky” Wichmann Jr. with a miniature replica of a former boat named MOBJACK that he and his father once sailed. The original boat was a 1935 Francis Herreshoff design.

is optimal for a sherman or an Army engineer’s workboat because of its stability, practicality and price. e rst Simmons Sea-Ski was a rowing boat designed with a strong in uence from an old dory hulk and used for net shing from the ocean beach. e boat’s maneuverability is designed to be a one-man operation.

Sappho won the 16th Annual Cape Fear Community College Boat Show as well as Best in Show and People’s Choice Award. Coste’s boat was appraised for $23,500 a er winning both accolades, which are the top two honors in Wilmington, North Carolina, which also happen to be the home of the Simmons Sea Ski . “It will get you out and back a long time a er you wish you weren’t out there. It’s sturdy,” Coste says with a smile. Coste’s other love, Scoota, is also sea- and show- worthy. A 1951 Halsey “Scooter Pooper,” the boat was built here in Charleston at AO Halsey Boatworks. is was a popular boat before the berglass era. Five years ago, Coste caught word of a boat for sale down in a barn in Georgia. Scoota was considered an antique and the owner was adamant about it going to a museum. By happenstance, at the time Coste was president of the Battery Gadsden Cultural Center, a non-pro t organization that seeks to share the rich history of Sullivan's Island through lectures and performances. is association made Coste t to be a caretaker for the boat and he has since donated plenty of his time and sweat equity into restoring it.

e boat itself consists of a petite, 12-foot marine plywood frame with a mahogany deck. A perfect creek boat, it scoots along with no more than a 10 horsepower engine on the back of it. Fittingly enough, Coste has boat access within golf-carting distance of his home. e ideal inlet for trolling through the creeks on the Intracoastal Waterway.

Within the local wooden boat community, a very small circle, Coste’s friend Sam Gervais of the Lowcountry Maritime Society is similarly avid about the cra e James Island native was a water baby as well and grew up sailing competitively.

One day, during the summer of 2019, Gervais was asked by the founder of Lowcountry Maritime Society, Prentice “Tripp” Brower, to take over the helm of the business. Brower and Gervais used to compete in sailing competitions and forged a friendship through their mutual love for the watersport. Brower showed Gervais the ropes of the trade before he jumped on his sailboat to take a trip halfway across the world. Brower is still on that voyage out at sea and has yet to return due to travel restrictions caused by COVID-19.

Gervais, a former history teacher at Cane Bay High School, is now the executive director of the Lowcountry Maritime Society. e nonpro t’s mission is dedicated to connecting the community to the water and teaching math and science to h- through eighth-graders in public and private school. Gervais’ boat-building courses provide a team-based interdisciplinary platform that teachers can easily integrate into their current classroom curriculum.

Every April the Lowcountry Maritime Society hosts a boat launch, o en in line with the In the Water Boat Show at Brittlebank Park in downtown Charleston. Here they launch all the boats the students have worked on over the course of the program. Gervais cherishes the full-circle aspect of teaching and going from a pile of lumber to cra ing a seaworthy specimen. For him, that moment when that lightbulb goes o and it clicks for the student, is what it’s all about.

Opposite page: Bunky Wichmann Jr. is the grandson of the former keeper of the Cape Romain Lighthouse, built in 1958.

No stranger to wooden boats and all things sea-related is Sullivan’s Island resident Fredrick Carl “Bunky” Wichmann Jr. e nickname Bunky was coined as a baby in the crib from an old Vaudeville act starring Dot Johnson, but that’s not what’s important or unique.

Wichmann’s grandfather was the keeper of the Cape Romain Lighthouse built in 1958. Ever since he was a child Wichmann knew that the ocean would revolve around his life and sure enough he was right. At just 10 years old, Wichmann was already racing sailboats o shore with his father. His family has been sailing to the Bahamas since the 1960s.

Little did Wichmann know that six years later he would nd himself on that same course, except this time without parental supervision. In 1976, at the tender age of 16, Wichmann and his best friend Bill Swanson sailed from Charleston to the Bahamas and back. Ironically, the boat’s name was Con dence, because the intimate details of that trip are personal, says Wichmann. He will admit that this was a turning point in his sailing career. It was a coming-of-age type voyage. “I wouldn’t let my kids do what I did, hell no,” he laughed.

Today, Wichmann owns a 1973 Man O’ War Sailing Dinghy and a 1989 Sea of Abaco, but nothing compares to his prized possession MOBJACK. An original 1935 Francis Herresho design, MOBJACK was purchased in 1981 with no mast and no hint of any seaworthiness, although it was rumored General George S. Patton supposedly once sailed on the boat.

A er xing her up, Wichmann and his father spent the next 35 years sailing her up and down the East Coast from New England to the Caribbean. But, before she was nally put to rest, he would nd himself on yet another “ill-advised adventure.”

It was 1983, Wichmann remembers the exact year because it was when Australia beat the United States in the America’s Cup. e 132-year-old sailing event was traditionally taking place of Newport, Rhode Island. Wichmann was out in those same waters in MOBJACK when devastation hit. Approximately 120 miles out from New York, Wichmann and a sailing partner hit a patch of nasty weather and the boat began to capsize. He recalled using 5-gallon buckets to try to bail out the water but it made no di erence. With the help of the U.S. Coast Guard, they were able to make port at Ocean City, Maryland without surrendering the boat to the sea.

Wichmann has a miniature replica of MOBJACK that hangs on the wall above his kitchen in his home. He rarely ever takes it down so dust visibly collects, but every time it catches his eye the memories accumulate as well. In February, Wichmann and his family returned to the Cape Romain Lighthouse to spread the ashes of his father, who would have turned 91 this year. In recent years, there have been attempts to decommission the light, but it is protected by the Cape Romain National Wildlife Reserve.

Wichmann lives by his father’s words of wisdom that he has passed down to his son, eo. “Have fun. Have an adventure. And don’t be afraid to take risks—within reason.”

Reverend Monsignor Lawrence B. McInerny’s family has been on Sullivan’s since the building of Fort Moultrie, and four generations of McInernys have made the island home. The Stella Maris priest sat down with the Battery Gadsden Cultural Center Oral History Project to tell the tales of his family’s time on the island and help keep its history alive.

By Kinsey GidickTop: Father McInerny’s aunts and uncles sit with John McInerny who was born on Sulllivan’s in 1842. Bottom: Father McInerny’s aunt Christle (center, in large hat) with some locals, enjoying a classic Sullivan’s past time.

These days, there are very few people on Sullivan’s Island who can trace their family’s arrival to the 1840s. Rev. Msgr. Lawrence B. McInerny, J.C.L., better known as Father McInerny to his congregation at Stella Maris Catholic Church on Middle Street, is one of them. As Father McInerny recently recounted to the Battery Gadsden Cultural Center’s Oral History Project, his family grabbed a Lowcountry foothold in 1840. at’s when McInerny’s ancestor Michael McInerny le County Clare Ireland (pre-potato famine, mind you) and wound up making a home on the island at the same time Fort Moultrie was under construction.

“I know he lived on Cow Alley,” says Father McInerny in the recorded talk that’s now stored on Lowcountry Digital Library operated by the Addlestone Library at the College of Charleston. One of 11 videos made thus far, Dr. Mike Walsh, Battery Gadsden Cultural Center president, says the project is an e ort to preserve the histories of long-time islanders and their families. Joining individuals like Ruth Schirmer Dehaven, who tells of an area of the island once called “Schirmerville,” and Carl Smith’s look back at his years as mayor, McInerny was a natural addition to the collection. And what we can learn from his story is a better understanding of a bygone age for one of Charleston’s barrier islands.

rough photos and stories passed on by his Irish forebears, Father McInerny describes an island far from the one we know today. A place that promised immigrants a new life lled with opportunity. A place where, as his grandmother described it, “anybody could come and eke out a living.” at’s what Michael McInerny was a er, Father says. But if Cow Alley doesn’t sound like the place to nd it, consider this: that’s actually Station 9 ½ today —a place now recognized for its opulent seaside estates.

Michael McInerny was in the real estate business, too. Father McInerny says he purchased quite a few properties but had trouble in business. “I found out that he had a bakery that burned, and it was an arsonist who had also set res at Fort Moultrie. I think maybe the burning of the bakery is what messed him up with the business,” says Father McInerny.

Tragedy struck again in 1884 when Michael McInerny was hit by a distracted driver, in this case one driving a horse and buggy, and he died from his injuries. But the family legacy continued thanks to Michael’s progeny.

Michael McInerny immigrated from County Clare, Ireland to Sullivan’s in roughly 1840.

Michael McInerny immigrated from County Clare, Ireland to Sullivan’s in roughly 1840.

Father McInerny’s father, pictured here around 2 years old. His mother took him into the city for his portrait.

Father McInerny’s father, pictured here around 2 years old. His mother took him into the city for his portrait.

Clockwise from left: The town post office where Father McInerny’s aunt was post mistress. E. Reynolds McInerny standing in front of The Launderette in the 1950s, the building was once the post office and originally built as his father’s store. A quarter master’s boat at Ft. Moultrie. Centennial Hall—built in honor of the Revolutionary War centennial. Francis Simmons and Douglas Watson in front of a tree bearing Father McInerny as a young boy. In the background is the Blanchard homestead and the former A.M.E. Church.

Michael’s son, John Francis McInerny, was born on Sullivan’s Island in 1842. “He’s probably my favorite of the ancestors,” Father McInerny says. John Francis is notable for quite a few Sullivan’s landmarks. To begin with, and as hard as it might be to believe, he owned a lumber business on the island, which he eventually operated from Station 18 ½ to 19. “It never worked well. It wasn’t deep enough. It was kind of undependable in getting the lumber o -loaded,” Father McInerny explains. Out of luck and out of cash, when Reconstruction hit, John Francis moved to Brooklyn, met his wife, and had a baby who would become Father McInerny’s grandfather.

By 1875, records show the family had returned to their ancestral home on Sullivan’s and in 1889 John Francis bought Centennial Hall. Now there are a very few islanders who have photos or have heard of this once important building, so for those who haven’t, Centennial Hall was a gathering place opened in commemoration of the centennial of the American Revolution on June 28, 1876. “ ey had a pool table. ey had changing rooms. ey had dances. ey advertised they had a fancy piano; they could make up a hop at any time. ey served food,” says Father McInerny.

And incidentally, in a twist that could only happen in a small island community, it was built by Father McInerny’s great-grandfather on the German side, Anton Hammerschmidt. But by the time it landed in John Francis’s portfolio, it was in disrepair. e cyclone of 1885 had le it in tatters. He later sold the building and it no longer exists today.

Grandfathered In

is all brings us to Joseph P. McInerny, son of John Francis and the man who would become the grandfather to our narrator, Father McInerny. We can all thank Joseph P. for bringing better education to the island. It was his life’s work. e merchant who raised seven children loved to sh, but it was getting a public school out on the island that was his great ambition, which he worked toward until he died in the late 1920s.

But not before Father McInerny’s father had arrived. Edward Reynolds McInerny was born at the family’s Sullivan’s homestead in 1910. At the time the army was still onsite and this colored his childhood. “It was a di erent world, in the sense of the soldiers and the mortar battery up there where the Town Hall is today, watching the projectiles go out as the coast artillery practiced up there,” Father McInerny says.

Life ran on when the next ferry boat was to arrive. He played basketball on a team that practiced on a court behind the rear part of the post exchange. In between his athletics and shing in the creek, Edward got his rst job working in the laundry at Fort Moultrie. Learning that trade led to his career running a laundrette on the island for the rest of his life.

Which brings us to Father McInerny’s generation.

“ ings have changed, but it’s still a good community. It’s a great community. I think the great thing is all the people that love the island,” says Father McInerny. What he remembers is that the island was hopping with children in the post war baby boom. “ e other thing that I miss—we had a lot more Black people on the island in those days when we grew up. We’d played baseball over there in Mrs. Burbage’s backyard, and we all played together. We had a very, I guess you’d call it, diverse group, and not just among the children, but even the adults. You had the people who’d been here forever, and you had the people, of course, who had moved here, as was always happening,” he says. “But you had a lot of the old soldiers from Fort Moultrie still around, some of the sergeants especially. And they were a lot of fun. ey were some characters in their own right, you might say. So, there were a lot of di erent people.”

Part of the mission of the Battery Gadsden Cultural Center, a nonprofit established in 1992 to create a museum of the civilian life of Sullivan’s Island, is to collect the oral histories of island residents. The Sullivan’s Island Oral History project conducts interviews that document both facts and lore related to the Island and its culture. By creating digitally accessible oral histories, the project serves to protect these records and to make them available to everyone for both personal enjoyment and historical research. There are currently around a dozen interviews with islanders stored in the Lowcountry Digital Library online at lcdl.library. cofc.edu/lcdl. If you or someone you know has a story to tell about their connection to Sullivan’s Island, contact the Battery Gadsden Cultural Center at batterygadsden@gmail.com.

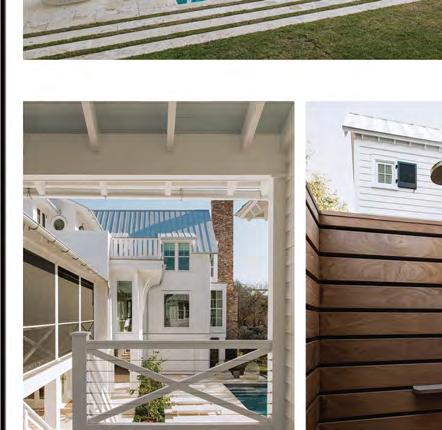

3 52nd IOP

9 Tabby Lane IOP

And the kids had free rein of the island. McInerny says every child had access to a bike and a small boat and once they could handle either with relative competence, they were free to do as they pleased. is independent childhood made Father McInerny fall in love with his island home, so when it was time to take his vows as a priest, he says it was hard to say goodbye. “I never dreamed that I would be pastor of Stella Maris,” he says. “Part of my biggest struggle in becoming a priest was leaving the island, because obviously I have deep roots here. But I love the people and I love the place. I was in seminary for four years, and I decided to take a couple years o ... I nally decided that Sullivan’s Island is great, but it’s not the kingdom of God. It’s almost there, but it’s not quite. We always say that’s why we have mosquitoes and gnats—to remind us we’re not in heaven yet. Otherwise, we’d get confused.” But, divine intervention apparently had another plan. “In our diocese, you would go anywhere in South Carolina. We cover the state. And it was very much to my surprise. I was probably 10, eleven years into the priesthood, always in the Charleston area, but they asked me if I would take Stella Maris. So I said, ‘Well, let me pray over that.” I said, ‘Hail Mary, full of—yes!’”

And that’s how four generations of McInernys have shaped this island and made Sullivan’s home.

Stunning oceanfront like location on quiet side street with residential only parking. 100’ x150’ lot with fantastic potential.

Overlooking the Intracoastal Waterway, this one owner waterfront house sits on almost 3/4 acre impecabbly landscaped lot.

12 Sand Dune Lane IOP

Front beach luxury home in a private community. It comes completely furnished with a solid rental history. PENDING

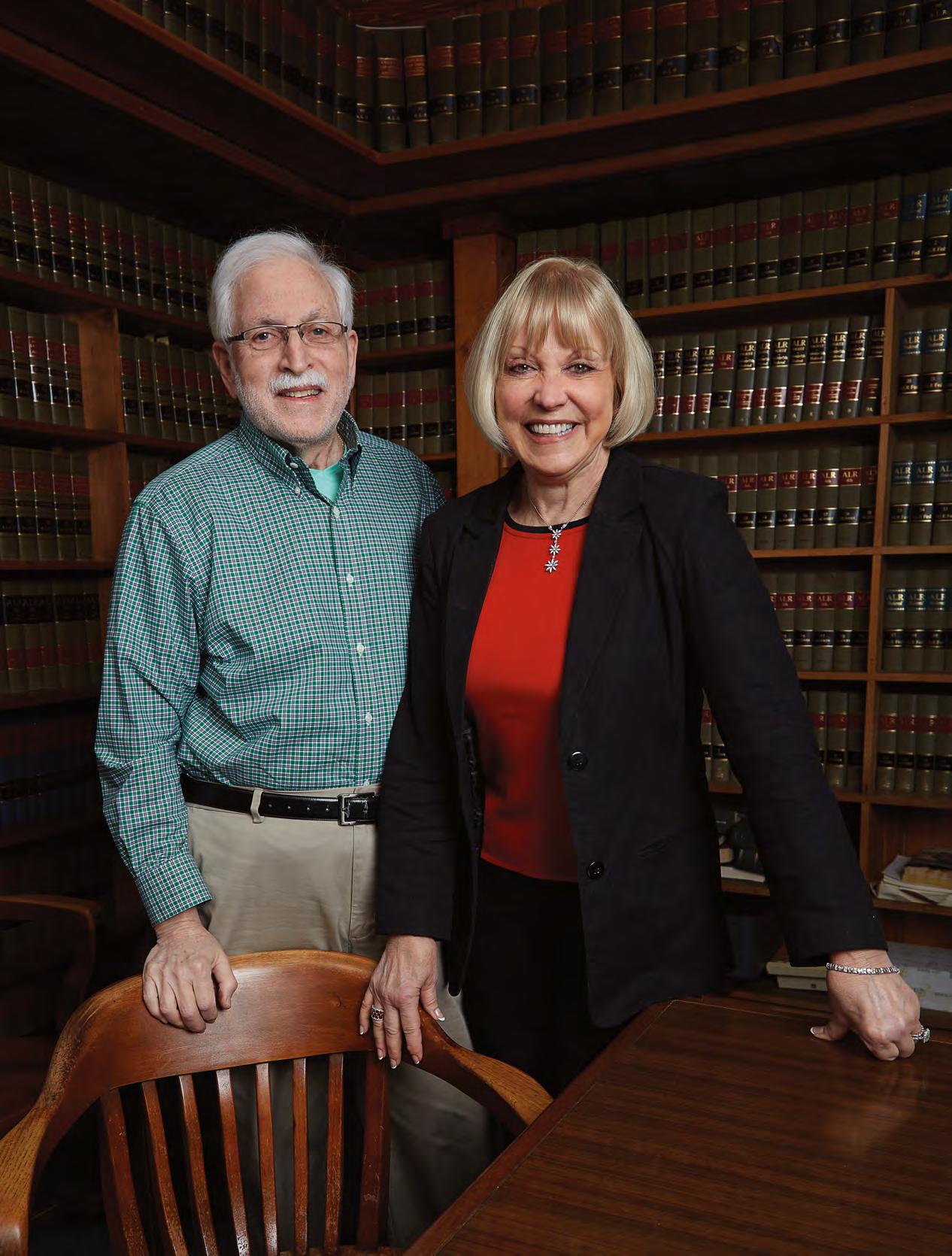

Jerry and Cheryl Kaynard are dedicated to improving their Sullivan’s Island community and helping those less fortunate.

By Colin McCandless Photos by Mark Stetler“ If there is any one word people would use to describe me, it’s ‘relentless’.

- CHERYL KAYNARD

Spending time with Sullivan’s Island residents Jerry Kaynard and Cheryl McMurry Kaynard in their downtown Charleston o ce o ers a window into the lives of these workaholics, community activists and humanitarians. A quick scan around the room reveals photos of Jerry posing with former President Jimmy Carter and Cheryl with current President Joe Biden. e Kaynards have devoted their lives to public service, and both are proli c. Jerry is an attorney who spearheaded the creation of Charleston Pro Bono Legal Services, a former Town of Sullivan’s Island councilman and mayor pro tem, and a former South Carolina DHEC board vice chairman. Cheryl is an attorney, business executive, educator and former Chief Counsel to the Federal Highway Administration. She currently serves on eight boards including chairing WestEdge Foundation and serving on e Sherman House, Pavillon International (a residential addiction treatment center) and e North Carolina Arboretum, among others.

Jerry, who worked for Jimmy Carter during his gubernatorial run in 1966 when the future attorney was attending the University of Georgia, considers the former president a role model and personal hero. He headed the Carter campaign for Charleston in 1976 and his 1980 re-election run, while serving as Charleston County Democratic party chairman. In 1980, Cheryl was serving as Chief Counsel to the FHA in Washington, D.C. e story behind how they rst met is connected to these respective roles and led to a collaboration that produced a well-known Charleston bridge.

Jerry and Cheryl McMurry Kaynard in their downtown Charleston office, located on Church Street.

Jerry and Cheryl McMurry Kaynard in their downtown Charleston office, located on Church Street.

Cheryl and Jerry relaxing at their Atlantic Avenue home on Sullivan’s Island, with their two golden doodles Banjo and Bosco—the real bosses in the family.

Cheryl and Jerry relaxing at their Atlantic Avenue home on Sullivan’s Island, with their two golden doodles Banjo and Bosco—the real bosses in the family.

that spawned a bridge

eir chance meeting occurred amid the height of political season during Carter’s 1980 re-election run, when everyone was “jockeying for favors,” as Cheryl cynically phrased it. Jerry met Cheryl by accident in the D.C. airport and while chatting they learned they shared some common friends. ey soon formed a friendship of their own.

Using his White House contacts, Jerry procured them tickets to the main table of a swanky black-tie gala hosted by the Jewish service organization B’nai B’rith International, where they were seated with Cheryl’s then boss, Secretary of Transportation Neil Goldschmidt, who was receiving an award.

It being election season, Goldschmidt asked Jerry if there was anything the U.S. Department of Transportation could do to help South Carolina. Jerry, who was working as a city attorney for then-Charleston Mayor Joe Riley, mentioned a local bridge project known as the James Island Connector. Jerry communicated to Goldschmidt that they had never been able to get the federal money to build it. In reality, original construction e orts dated back to the ‘60s and the project lay dormant at the time. Goldschmidt promised to look into it.

When Jerry admitted to Riley that he had misguidedly told Goldschimdt the James Island Connector was an active project, Jerry asked who should consult with the DOT. At that time, Charleston had a bare-bones planning department, and that’s how Jerry became the liaison to the federal government on the Connector project.

As Chief Counsel to the FHA, the DOT division which funds bridge construction, Jerry’s new friend Cheryl soon became an in uential ally in his quest to secure federal dollars. ere was a government freeze at the time, which complicated matters, but Cheryl caught wind of some discretionary money available and doggedly pursued it for the Connector project. Her persistence paid o , to the tune of $5 million. “If there is any one word people would use to describe me, it’s ‘relentless,’” quipped Cheryl.

Funding secured, there was still the not-sotrivial matter of White House approval. at’s where Jerry’s White House contact delivered. His former University of Georgia roommate Hamilton Jordan was serving as Carter’s Chief of Sta . Jordan approved it and Cheryl moved forward to release project funding. It took 13 years for the bridge to be completed, but the Connecter was eventually constructed and today it serves as a vital freeway link between Charleston and James Island.

Although she lived in Oklahoma at the time with her then husband and two daughters, Emily and Maggie, at Jerry’s invitation Cheryl ew into Charleston for the 1993 bridge dedication. “What I love about the story is the serendipitous part of it,” she recalls, of how an accidental meeting helped with the building of a bridge that had been stalled for years. Jerry re ects that the experience taught him the life lesson “that when an opportunity presents itself, you’ve got to be ready to grab it.”

“ When an opportunity presents itself, you’ve got to be ready to grab it.

- JERRY KAYNARD

Jerry and Cheryl would later marry and have now been together 12 years. Cheryl commuted from Asheville during the rst year of their marriage while serving as CEO of the Bent Creek Institute, which conducts research into medicinal botanicals. She eventually sold her house and moved to Sullivan’s Island to live with Jerry on Atlantic Avenue in a house he built in the 1970s.

Cheryl, who grew up in a little Oklahoma town said she “loves the small-town atmosphere” of the island and the “milieu of people who know each other.” “I love seeing people out walking on the beach and walking their dogs. Just doing things that are reassuring during these anxious times.”

One of Jerry’s proudest moments during his eight years on Town Council was helping lead the ght to save Sullivan’s Island Elementary School. Built in 1955, an inspection conducted in the mid-2000s revealed structural de ciencies that deemed the building unsafe and necessitated a rebuild. e rebuild needed to be large, and a vocal minority in the community voiced opposition over tra c near their homes and sightline concerns. Jerry, who then served as Sullivan’s Island’s mayor pro tem, felt the “health and vitality of the community were at stake.” Six council members supported reconstruction and one member was opposed, but there was a heated debate within the community over the size.

Construction was nally completed in 2015, with a capacity of approximately 500 students. “ e con ict over building was intense, but it was worth it,” recounted Jerry. He described one of his “forever moments” as seeing SIES rst graders on iPads and portable aquariums in classrooms that teach students about marine biology.

Although rebuilding SIES was controversial, Jerry believes people will look back and say it was key to the island’s future. He regards Sullivan’s Island as “Mayberry by the sea,” an idyllic place where kids ride their bikes and families cruise around in golf carts. “I like to think positively about the community spirit we have on the island,” he said. “I think of it as a community that can pull back together once we reach a decision.”

Cheryl, who has a master’s in Teaching from Winthrop University, re ected that she too believed that saving the school would help determine the island’s future. She expressed concern that without children Sullivan’s Island could have become an upscale retirement community. Cheryl added that the SIES rebuild issue was made more challenging because Sullivan’s Island is a tightknit place. “We’re all on this little island together. e sense of it being a community and neighborhood, so you’re concerned about decisions and how they a ect your neighbors and neighborly relations.”

In 2004, together with the Charleston County Bar Association, Jerry helped found Charleston Pro Bono Legal Services, an organization providing free general legal assistance to economically disadvantaged individuals who can’t a ord one. eir work is made possible through various grants, foundations and supporter contributions.

It has expanded from a two-person organization to a 10-person o ce with ve lawyers today. Charleston Pro Bono is the successor of the federally funded Neighborhood Legal Assistance Program, over which Jerry served as long-time board chairman.

Since Charleston Pro Bono’s inception, Jerry has provided 150 law students summer internships to help them gain their rst experience in public interest law. He typically hires at least 10 students every summer whose internships are funded by the Ackerman Foundation, a private foundation supporting education, the arts, student programs and legal services for low-income persons.

Pro Bono’s lawyers also do special housing project work protecting people who cannot a ord to pay their rent from eviction, an issue that has become dire during the pandemic. e project has developed from a narrow program to a community-wide assistance e ort. “ at’s something that’s very important to Pro Bono’s e orts,” said Jerry. Pro Bono has even been part of Mayor John Tecklenburg’s City of Charleston Homeless Task Force, assisting citizens of the “Tent City” that were camped under the Interstate 26 bridge in accessing transitional housing and nancial resources.

Cheryl, who assists Pro Bono as an attorney, called Jerry, who serves as board chairman, the “driving force that has kept the organization alive.” She also referenced the 2016 executive director hire of the “very dynamic” Alissa Lietzow as making a profound impact. “It’s very inspirational,” she remarked of Pro Bono. “People are trying to help their neighbors.”

In 2015, Charleston Pro Bono became the sponsor and bene ciary of the popular Sullivan’s Island fundraiser Art on the Beach and Chefs in the Kitchen. e annual November bene t, which quickly sells out every year, features a tour of homes on Sullivan’s Island, chef demonstrations and an art show. In addition to showcasing the culinary creations of Sullivan’s Island chefs, it gives local and regional artists an opportunity to promote their talents. “We get to do all of that in a bene t for a worthwhile organization,” said Cheryl. “It’s a really great community project.”

Coordinating a fundraiser of this magnitude requires an extensive volunteer e ort, including gracious hosts accepting the risk of inviting strangers into their residences. “ ese folks that open up their homes, that’s a big deal,” asserted Cheryl. “It’s a leap of faith.” Cheryl pointed out that you can’t discuss the event without recognizing Carol Antman, who started the fundraiser more than 20 years ago. Art on the Beach originally bene ted local performing arts school Creative Spark until it closed down. Jerry, who is friends with Antman, collaborated to transfer the fundraiser’s assets to Pro Bono in order to keep its nonpro t status, leading to Pro Bono assuming responsibility for managing the event. Last year’s fundraiser was virtual because of the pandemic, but the hope is to hold an in-person event in 2021.

Despite everything on their plate, the Kaynards show no signs of slowing down. “I’m always looking for new things to get involved in,” said Cheryl. Jerry added they feel their good fortune in life obligates them to give back. “Both of us are trying to reach out and make the world a better place for those who are less fortunate.”

Faith inspires Walter Sherrill, Sullivan’s Island Elementary’s school crossing guard, to serve as community ambassador.

By Colin McCandless Photos by Rob BykoF“ He’s completely focused on his work and the kids. They just adore him. - SUSAN KING

or many Sullivan’s Island Elementary School students, the school crossing guard is the rst person to greet them in the morning, and o entimes the last person they see in the a ernoon as they head home. is individual bears the important responsibility of guiding their safe passage through tra c, which can be a dangerous proposition on the busy streets of Sullivan’s Island. At SIES, this vital role belongs to Walter Sherrill. As a school crossing guard, state law authorizes Sherrill to stop tra c in order to allow the children to securely cross the street. “ at can really be something today because there are so many distracted drivers,” observed Sherrill. Texting while driving and speeding are two of the most common issues he regularly witnesses. “Someone wanting to get nowhere in a hurry,” he quipped.

Compounding that challenge, school trafc has risen during the pandemic since fewer children are riding the bus due to capacity limits and more parents are dropping kids o by car. With more students than usual to safely usher across the street, it’s been a busy year, but it’s all worth it to Sherrill when he glimpses the childrens’ smiles and hears their heartfelt ‘thank yous.’ “It’s just fun to see how grateful the children are,” beamed Sherrill.

His road to becoming a school crossing guard is connected to his time as a Sullivan’s Island beach patrol o cer. Sherrill, who grew up in Lincolnton, N.C., spent 32 years in Philadelphia where he worked as a chemist in a clinical laboratory. He retired in 2005, and in 2006, he and his wife, Dorothy, a retired teacher who originally hails from Mount Pleasant, decided they would move to her childhood home.

Retirement proved an ill- tting suit for Sherrill. He tried it on for a time and then boredom set in. “I wanted to keep busy,” recalled Sherrill. His initial return to the daily grind included part-time gigs at Ace Hardware and Target. en in 2013 he answered an employment ad for a Sullivan’s Island beach

Opposite page: Sherrill at work on Sullivan’s Middle Street. He says distracted drivers are his biggest concern when it comes to students’ safety.

patrol o cer and was hired. His duties included patrolling the beach and enforcing the Town of Sullivan’s Island’s ordinances, including regulations pertaining to alcohol and dogs.

During the 2016-17 school year, SIES, which at this time didn’t have a school crossing guard, asked the Sullivan’s Island Police Department whether they could provide anyone to assist with morning and a ernoon student street crossings. Police Chief Chris Gri n approached some of the beach patrol o cers to see who would like to volunteer. Sherrill stepped forward since it was convenient for o cers to come o the beach during those hours to lend a hand. Soon a er the school requested a permanent crossing guard. Sherrill applied and the Charleston County Sheri ’s Department hired him on October 19, 2017.

Due to some family commitments, he recently retired as a beach patrol o cer a er serving eight years, which has freed up availability to continue his SIES crossing guard duties. “At least as long as I can,” said Sherrill. What Sherrill loves most about the job is the gratitude shown him by parents, teachers, and most especially, the children. “ e children are a real delight,” he remarked. “ ey are so appreciative of the assistance they get in crossing the street.”