The Future of Architecture:

An assessment of the visual psychology of our built environment during a climate emergency

To find a solution for reusing buildings for environmental purposes while improving the beauty and organicism in urban environments.

by Myia RobinsonA Dissertation

Submitted to Mackintosh School of Architecture

Glasgow School of Art

In Fulfilment of the Requirements

For the Degree of a Masters of Architecture by Conversion

9986 words

January 16, 2024

Acknowledgements

I am extremely grateful for the prodigious support, encouragement, and wisdom that I have received from those around me in the effort to create this dissertation.

Firstly, I would like to thank my research project tutor Graham Massie for his continued input into my research topic and for his words of wisdom, which was always appreciated.

I would like to acknowledge a special thanks to Emily Bagshaw, material specialist at Material Source Studio Glasgow for the generous time devoted to conversations about relevant industry materials and the future of materials with regards to bio products and integration of such in the built environment.

To add to this, I’d like to thank Alex Rayner, Campaign Manager for the Humanise movement for showing recognition of my project and for sharing some insights into their current work.

To my family who have provided care and support and to my partner Jack, who has devoted endless time into countless conversations and kept me on track throughout the whole process.

Thank you.

Contents

Part One

Introduction pg 8-10

1.1 Preface pg. 8

1.2 Research Hypothesis pg. 8-9

1.3 Methodology pg. 9-10

1.4 Literature Review pg. 10

Part Two

Analysis pg. 12-22

2.1 Chapter One:

Environmental Psychology pg. 12-14

2.1.1 Ornamentation pg. 14-15

2.2 Chapter Two:

Climate Change pg. 15-17

2.3 Chapter Three:

Architectural History pg 17-20

2.3.1 Community and Cultural Influences pg. 17-19

2.3.2 Historical Review of Architectural Styles pg. 19-20

2.4 Chapter Four:

Public Opinion pg.20-22

2.4.1 Past Public Survey Analysis pg.20

2.4.2 Publishing and Gathering Survey Responses pg. 20-22

Part Three

A Guide for the Future of Architecture pg. 24-34

3.1 Changing Opinions pg. 24-28

3.2 Reuse / Retrofit Guide for Integrating Natural Elements pg. 28-33

3.3 Conclusion pg. 34

Part Four

Appendix A pg. 36-67

Appendix B pg. 68-94

Appendix C pg. 95-98

Bibliography pg. 99-102

Introduction

1.1 Preface

The climate emergency is now at a critical point. Over the past few years I have been made acutely aware of some of the effects of climate change that we don’t see here in the UK. Specifically the transatlantic climate regressions. Most of my partner's immediate family live in the capital of Fiji, Suva but many of his wider family still inhabit the villages on Fiji’s smaller islands - villages that are disappearing. Over the past decade many of these villages have seen mass migration away from their ancestral homes inland to avoid the rising water levels but it is ultimately catching up to them. It is only now when extreme weather changes and dwindling resources have become an issue for us that our government has been forced to re-evaluate their policies and push new targets for the reduction of carbon emissions.

Governments around the world are increasing the pressure on designers and engineers to change the status quo. To adapt the practices that have defined our industry for centuries. “Reuse” of old buildings instead of rebuilding or building new is being pushed in the industry to be the standard for the built environment.

To add to this already momentous shift there have been massive advancements in the research of environmental psychology that shows a clear link between the visual aspects of our surroundings and mental health. I first encountered this new field of research when completing a project to design a community centre which led me into the research linking spaces and the development of young children, a fascinating topic that extends far beyond just developing minds. Research shows that our surroundings affect us throughout our lives, from how we develop as kids to our mental health as adults. This topic is starting to become more mainstream, and it is beyond doubt that as more research is completed showing evidence for this link, we as architects will need to design with this in mind.

We must now confront a dual mandate. To balance redefining our role in the development of the built environment and the well-being of those who inhabit it.

1.2 Research Hypothesis

Buildings today are more minimalist and brutalist than ever… is this for the best?

When I began my journey into the world of the built environment, I came into it with an instinctual appreciation for organic and natural architecture. I loved the flowing lines, curves, and textures. When I was a child, I didn’t see any organic architecture anywhere and I remember feeling almost emotional the first time I saw an organic building. I was captivated. I was 15 looking at a piece of paper, on it was a photograph of The Guggenheim in Bilbao.

Throughout my education I have explored many different styles though I have always leaned towards an organic and nature-oriented approach to designing the urban and built environment when I can. As I have progressed into my postgraduate years, I have questioned why I have always seemed to subconsciously encourage my style in this way, which in comparison with much of my cohort, differs completely. Simply I believe I try to in my work capture that same emotion I felt that day as a 15-year-old the first time I was truly inspired by an image of the built environment.

In my thesis post graduate project, I explored deeper into this topic with a look into the importance of organically influenced spaces on the phenomenological experience of a user and in previous years researched the importance of these types of internal spaces (curved, soft, nature-inspired) on the positive well-being of inhabitants. What positive effects do minimal, angular, and jagged edged lined rooms have on the phenomenology of a space for its user? My response would be not many. So why then do we now see so many modern buildings being so minimalist and angular?

1.3 Methodology

The goal of this project is to create a modern guide for architects to begin to answer how we can adapt to the need for change in how we design, based on the demands of the ongoing climate emergency and the rising awareness of how the built environment affects mental health. This guide aims to provide advice and tips as well as identify opportunities, backed by research for how architects can design for the betterment of mental health during a climate emergency. Specifically, it tries to identify opportunities for new standards in architecture that maintain a level of artistic freedom during this push to “reuse”.

By examining existing studies and research in environmental psychology that provide evidence for the link between the built environment and mental health I hope to gain a better understanding of what are the key contributing factors to mental health and how best to incorporate this.

Following this I intend to explore different architectural styles from movements in history such as the Classical, Gothic & Medieval, Renaissance & Mannerism, Eclecticism and Post Modernist periods. My aim is to understand the characteristics and design features of each and then to further determine public opinion through surveys to determine the preference of Architecture styles of the public.

I aim to use this information with the information I gain by my research into studies of environmental psychology to best determine what styles potentially should be considered when designing for the betterment of mental health.

I will also evaluate the current state of the climate emergency and the goals and expectations placed on us by the government in their ambitions to reduce the carbon footprint, specifically here in the UK. In the end, as mentioned prior, I aim to provide a guide to navigate the challenges we face as an industry to implement change to help evaluate how best we can balance these two great challenges which will define the future of architecture

1.4 Literature Review

Throughout the following body of research, I have citied many valuable literature sources but it has been the writings of a few integral pieces of literature that has encouraged and inspired the content of this project in particular. Antoine Picon’s ‘Ornament – The Politics of Architecture and Subjectivity’ delves into the relationship between ornamentation in architecture and its political and subjective dimensions and explores how architectural ornamentation reflects societal values and individual subjectives from a historical place to a prediction of the future of architectural ornamentation. Studying this piece allowed me to make my own presumptions about how ornamentation should be and could be integrated into architecture as a future application, as a reconsideration of its demise in recent architecture as a way to make better visual connections between our built environment and the need for emphasizing the importance of nature in this crucial point in time where the climate emergency is at the forefront of design.

‘Humanise’ by Designer Thomas Heatherwick, is a controversial source that explores the human-centered approach to design and architecture, that discusses how design can enhance the human experience and well-being of inhabitants and interaction from the street perspective. It provides examples of Heatherwick’s personal life experiences and accounts of completed project experiences too. Heatherwick’s ambition to create an agenda for reconsidering Architectural motives of the industry to be more people-centric, are in alignment with my own desires for the future of architectural principles which will be discussed throughout this research document. In contrast with Heatherwick’s ambitions for change in the overall design outcome of our buildings for the future, the ambitions of this project are more specific to a reuse and retrofitting agenda where similar design methods can be applied to existing buildings in our society.

Furthermore, the written works of Gaston Bachelard ‘The Poetics of Space’, ‘The Architecture of Happiness’ by Alain de Botton and ‘Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-being’ by Esther M. Sternberg provided the body of research with empirical evidence and thoughtprovoking discussions into philosophical and psychological orientated architectural accounts, that focus on the importance of beautiful and well-designed spaces for the influence of a person’s emotional well-being and health.

‘The Impact of the Physical Environment on Mental Well-being’ by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and IStructE Guide ‘Circular Economy and Reuse: Guidance for Designers’, have helped to provide some integral industry guidance and knowledge into the topics discussed throughout.

2.1

Chapter One: Environmental Psychology

Though it seems now that the topic has been around forever, the topic of “mental health” is still a relatively new one, predated by the 2“mental hygiene movement”. There have been thousands of studies into mental health, and millions of campaigns to help raise awareness. Study after study delves into the human mind, identifying the root causes for why we feel the way we feel, why some people are more prone to depression, some people are more confident and outgoing, it would be easy to assume that we have truly exhausted every avenue of research in understanding the human mind and human emotions, but in reality we are only at the tip of the iceberg, so to speak. One topic that is, frankly, no longer up for debate is that the environment around you does affect your mental health. It has been proven numerous times in the field of environmental psychology, through replicated research and individual studies 3that a person's surroundings can positively or negatively affect their mental wellbeing, mood, and overall levels of ambition. Past research has shown that the average human spends almost 90% of their lives indoors and a further 6% in vehicles, a statistic that left me baffled. I felt that this must be a gross over exaggeration, but it is frighteningly accurate. In a twenty-four-hour day you sleep for approximately eight. Whether you work remote or in an office that’s on average, another eight spent indoors. Unless it's weather for a barbeque (which we are rarely fortunate enough to have in Glasgow) then food prep, cooking and eating are all done indoors; nights out, restaurants, family visits, are all indoors 4A recent study conducted in the UK seems to back this up, showing what percentage of time the average person spends doing specified categorised tasks. On top of this “modern” way of living, far removed from nature - architecture seems to be pulling further and further away from the natural world too, with no eyes batted at the lack of green or organic form in modern architecture, something I feel is going completely against human nature.

In 2021 the search for “Mental health” related topics reached its highest level ever5. I want to address this and offer help to tackle this by tackling architecture that has left us feeling isolated from nature. Choices made by the architect when designing, that benefit the net zero campaign for each individual building may be argued as doing enough towards a better, greener planet. Though this should be a given and though it is acknowledged and commended for positive

2 Mandell, Wallace. 1995. “Origins of Mental Health | Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.” Publichealth.jhu.edu. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 1995. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/departments/mental-health/about/originsof-mental-health.

3 Xu, Jiayuan, Nana Liu, Elli Polemiti, Liliana Garcia-Mondragon, Jie Tang, Xiaoxuan Liu, Tristram Lett, et al. 2023. “Effects of Urban Living Environments on Mental Health in Adults.” Nature Medicine 29 (6): 1456–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02365-w.

4 “Time Use in the UK - Office for National Statistics.” n.d. Www.ons.gov.uk. Accessed December 16, 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/timeuseint heuk/march2023.

5 “A Year of Healing - Here’s What Our Google Searches Can Teach Us about 2021.” n.d. World Economic Forum. Accessed December 16, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/12/google-searches-covid-lifestyle-mental-health/.

change in our built environment there still lacks a visual communication factor between the good that a building is doing for its user and the people using it or experiencing it as they pass by it on the street.

It can be argued that some of the best senses of “community” around the world are in places with very little. Poverty stricken places where people must come together but I would argue that cities that are intrinsically beautiful have the best sense of wider community, not necessarily in terms of small groups coming together for one another, but in a wider sense, a pride in their city that unites them. Through great beauty in the architecture, people can come together with a love for their city, a sense of pride that they want to protect and show to the world! Glasgow generally is a great city to look at when exploring this idea because we, simultaneously, have both a brilliant and awful sense of community.

“People make Glasgow” I think it’d be hard to find one Glaswegian who doesn’t get almost patriotic when a tourist brings that up, exclaiming that indeed we are the best city, that we have an incredible sense of community, that we are the friendliest place in the world. Yet at the same time, Glasgow has one of the worst senses of community experienced, between the religious divide and the general sense of danger the city has. Glasgow is a city that is completely void of any sense of wider community when the football isn’t on, and even that divides the city in two. Perhaps a reason, beyond religion, is that modern culture and architecture has fuelled a growing divide between people. Or rather has failed to force people to connect.

6“Architecture can’t force people to connect; it can only plan the crossing points, remove barriers, and make the meeting places useful and attractive.”

This wave of modern buildings seems to add barriers, 7the general layout and design almost make you feel like a trapped animal, against everyone and could be said to encourage a culture where the dominant emotion, present in people is envy. The effects of our upbringing, the reality of how we were raised, usually being told that ‘anyone can be anything’ has left everyone feeling slightly entitled and that we deserve the world because we work hard (even when we don’t), as a result of this we feel that same feeling, envy. Perhaps the modern minimalist style we see every day in most homes and nearly every building is causing us to be more envious of the perceived success we haven’t achieved ourselves. We live in a culture where true architectural beauty, intricate beauty, is reserved for the hyper-successful people who can afford 7 figure homes. Has this exacerbated envy? Perhaps if we design the poorest places with detail and beauty in mind, we can eliminate a sense of envy and therefore help to mend this crisis of mental health and depression as people will not feel that like failures - or worse - like they have been unfairly treated by the world for not achieving everything they set out to. This is the first time in human history where a caste system has not been present in society in some form or another, truly the first time where anyone can become successful. The problem is that with everyone being told this, we now feel like we deserve it. Perhaps if the average home was more beautiful people would feel more fulfilled with being average, we don’t need everything to be happy. Yet it doesn't feel that way, I think Architecture can be the solution.

6 Cutieru, Andreea. 2020. “The Architecture of Social Interaction.” ArchDaily. August 7, 2020. https://www.archdaily.com/945172/the-architecture-of-social-interaction

7 “How Architecture Affects Our Thoughts, Mood, and Behavior | Psychology Today.” n.d. Www.psychologytoday.com. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/redesigned/202304/how-architecture-affects-our-thoughts-moodand-behavior.

“We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us.”

By Winston Churchill is a famously known phrase in which he was regarding the repairs for the house of commons after German bombings in 1943, but no phrase better captures the need for architecture and design to consider the psychological impacts of the built environment.

Research being done in this field is finally starting to provide evidence to support specifics of what makes people feel best. 8One study in Iceland found that streets with the “most” architectural variation are the most mentally engaging. With it estimated that by 2050 75% of the world’s population will live in cities this is the perfect time to push this variety.

9A medical study found that darker rooms consistently resulted in patients requiring more medication such as painkillers. 10Another study, from 2017 found that many people tested against an investigation into human reactions to spaces with different geometry preferred curved edges and rounded rooms, which was the exact opposite reaction of the group of architecture students which also tested – a worrying realisation and arguably one of the more important things discovered in a study.

The book ‘Humanise’ discusses this debate of the curve vs the angular in some detail. 11 Humanise disagrees with the notion in Le Corbusier’s book ‘The Poem of the Right Angle’ that humans’ prefer angles to curves. This has been explored by Dr Oshin Vartanian where he tested a selection of people’s brain activity against a series of images of buildings. The tests revealed that when looking at the examples with curved elements, there was heightened activity in the brain area that processes emotional reward. Following this, when asked which buildings they found most beautiful, the group of people responded with the examples of curved buildings 12In similar tests, whilst looking at angular building examples, it was found that brain activity was heightened in the area that deals with stress and fear.

2.1.1 Ornamentation

Ornamentation has been an integral part of architecture throughout human history. It is only recently that we have seen a decline in this art form due to economic and cultural factors, and changes in architectural preferences.

Ornamentation was the initial, biggest influencing factor for this entire research project. Before I began this project, I had read the book by Antoine Picon named ‘Ornament’ which focusses on the politics and subjectivity of ornament.

8 Lindal, Pall J., and Terry Hartig. 2013. “Architectural Variation, Building Height, and the Restorative Quality of Urban Residential Streetscapes.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 33 (March): 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.09.003.

9 Malenbaum, Sara, Francis J. Keefe, Amanda C. de C. Williams, Roger Ulrich, and Tamara J. Somers. 2008. “Pain in Its Environmental Context: Implications for Designing Environments to Enhance Pain Control.” Pain 134 (3): 241–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.002.

10 Shemesh, Avishag, Ronen Talmon, Ofer Karp, Idan Amir, Moshe Bar, and Yasha Jacob Grobman. 2016. “Affective Response to Architecture – Investigating Human Reaction to Spaces with Different Geometry.” Architectural Science Review 60 (2): 116–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00038628.2016.1266597.

11 Heatherwick, Thomas. 2023. Humanise. Random House. Pg. 220-221

12 Heatherwick, Thomas. 2023. Humanise. Random House. Pg. 221

In my fifth year thesis project I explored many of the same themes discussed in this research project prior to now, like the notion of creating and improving senses of community through architecture and furthermore creating spaces for better well-being. I lead the architectural ambitions of the project with a focus on organic massing, which involved large scale changing topology across the volumetric shape of the proposed building. After reading this book by Picon, and analysing more of the work of Architect Victor Horta who captured beautiful detailing in his designs around Brussels, I felt like I had missed an opportunity to explore the intricacies of ornamental detailing within my project and felt it was therefore appropriate to extend my research into this masters thesis and through researching this I have established a desire for integrating it into my future career.

Craftsmenship including stone mason jobs are now rare because of the decline of craftsmenship over the years due to time efficiency and low income I hope there is a potential change in the future for this for economic purposes that creates a better unity between craftsmen and industry where technology is starting to overtake their roles.

In Picon’s book he addresses the idea that architectural issues should be displayed or interpreted through the external skin of the building as nothing is deeper than the skin and in response to this, the proposal is that ornament could withhold the key to these architectural issues. With previous discussions about the core architectural issue of addressing climate change, it should be explored that through the usual nature inspired forms that ornamentation takes, by implementing traditional uses of it, we could visually acknowledge the need for a better relationship with nature, for more climate awareness.

2.2 Chapter Two: Climate Change

The climate emergency has completely changed the landscape of this industry, not just in terms of the need for nature in architecture but in terms of the carbon output from the construction industry. The UK has committed to net zero, though the date for this is continually pushed due to just how far off we are technologically.13The main change when trying to push for net zero is to “reuse, not rebuild”. This movement unfortunately clashes with the importance of visual environmental factors on our mental health and leaves a question of how we balance the two major topics that will define the future of architecture.

The climate emergency, now more than ever, demands our immediate attention. It is the most pressing challenge we face today and possibly the biggest challenge humanity has ever faced. With depleting natural resources and a degrading ecosystem we now are faced with the consequences of generations of neglecting our planet. 14Recent studies predict we have less than 50 years of oil reserves left and with sea temperatures and levels rising exponentially,

13 “The Principals of Reusing Existing Buildings.” 2020. IStructE. November 2, 2020. https://www.istructe.org/resources/guidance/the-principles-of-reusing-existing-buildings/.

14 McFadden, Christopher. 2021. “50 Years or Never: How Much Crude Oil Do We Have Left?” Interestingengineering.com. December 4, 2021. https://interestingengineering.com/science/we-will-never-run-out-of-oil.

urgent action is being taken by governments and industries worldwide against this emergency before the damage to our planet and its delicate ecosystem becomes irreversible.

15The construction industry contributes as much as 40% of the UK’s carbon output. As a result, the industry has seen a massive shift, both brought on by new policies and greener targets set by the government and organisations that are taking the initiative to meet the demand for greener, more sustainable buildings. 16Over the past 30 years the UK has made massive strides in this field of sustainability and in November of 2021 Glasgow was host to COP26. The 26th annual conference hosted by the United Nations, at which government representatives of the 200 attending nations report on progress, set goals and negotiate policies all relevant to climate change. This particular “Conference of Parties” was special because it led to the Glasgow climate pact, the first global agreement to recognise the need to limit global warming at 1.5°C and to increase the ambition of national climate plans every year until 2025.

A few months prior to the conference, the UK announced plans to cut emissions by 78% of the levels recorded in 1990 by 172035 with the goal of net zero to be achieved by 2050. The UK has been very proactive in this and are still announcing many new initiatives to help reach this goal. The landscape of the industry has changed, possibly forever. With the industry's standard practices and goals now being more aligned with wider environmental goals. Major organisations such as RIBA18, IstructE19 and ARUP20 have created maps for how to reduce emissions and enact change. One of the most prevalent changes is the new push to reuse buildings where possible. 21“Don’t build!” was the phrase given by IstructE during a presentation about lean design. This push of course doesn’t mean nothing will be built anymore but highlights just how much change the industry faces. This raises the question, what will being an architect mean in the future?

Throughout history, humans have taken pride in the built environment. Through architecture, civilisations came to shape and define their culture, art and even religions over centuries of development. The desire to improve upon these structures pushed humans to make

15 Sutton, Jane. 2021. “Construction Sector Must Move Further and Faster to Curb Carbon Emissions, Say Engineers.” Raeng.org.uk. September 24, 2021. https://raeng.org.uk/news/construction-sector-must-move-further-and-faster-to-curb-carbon-emissions-sayengineers.

16 “UK Government Web Archive.” n.d. Webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Accessed December 6, 2023. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20230401054904/https:/ukcop26.org/.

17 Harrabin, Roger. 2021. “Climate Change: UK to Speed up Target to Cut Carbon Emissions.” BBC News, April 20, 2021, sec. UK Politics. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-56807520.

18 “RIBA Publishes Guide to Building Sustainably.” n.d. Www.architecture.com. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/knowledge-landing-page/riba-publishes-guide-to-building-sustainably.

19 “Net Zero Structural Design.” n.d. IStructE. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://www.istructe.org/events/hq/2024/net-zerostructural-design/.

20 “Designing a Net Zero Roadmap for Healthcare - Arup.” n.d. Www.arup.com. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/designing-a-net-zero-roadmap-for-healthcare.

21 “Lean Design: 10 Things to Do Now.” 2020. August 2020. https://www.istructe.org/IStructE/media/Public/TSE-Archive/2020/Leandesign-10-things-to-do-now.pdf.

advancements in technology, creating more and more sophisticated and innovative structures that have shaped society.

Now with a move towards actively restoring the ecosystem, more pressure than ever is on architects to not just design but to consider the consequences of the design. Furthermore, the onus to reuse buildings leaves architects at the mercy of a changing industry landscape.

This shift is forcing architects to work as ambassadors for climate, taking on more eco and social responsibility than ever before. There is a risk that this new push to reuse buildings, rather than start from scratch will forsake innovation in architecture but I believe that it is instead an opportunity to adapt. To use this opportunity to improve on our current built environment, to create new opportunities to innovate by detailing and designing onto or with current structures.

The current climate emergency has almost been a blessing in disguise in terms of nature in architecture. The need to create green, natural spaces is more in the public eye than ever. The effect that modern, minimalist and brutalist architecture has is that when people see these massive, concrete structures, they can be reminded of a time when environmental concerns were not as prominent, and this can, in turn, lead to a heightened awareness of the need for change in terms of the climate emergency, which can leave people feeling rather depressed and regretful of the actions of our society. Perhaps a solution as we move forward is to help reconnect people with nature through the built environment, since the need for raising awareness is no longer a massive issue, with this issue being at the heart of problems being addressed by the western world.

2.3 Chapter Three: Architectural History

2.3.1 Community and Cultural Influences

The Cambridge dictionary defines community as “people who are considered as a unit because of their common interests, social group, or nationality”. Briefly this description may seem an innocent and fair view of the term, but personally, with the changing modern attitude towards isolated groups, I find it divisive. Perhaps in the past this statement describing a community could have been viewed as positive, that communities of people with similar interests and social standing was beneficial but it is hard to deny that in our modern world a description such as this feels somewhat dangerous, completely counter to the actual meaning. A group united by their nationality has connotations of exclusivity and division, untrusting towards outsiders. Something that is all too rampant today, at least in the UK. In fact, a study recently published in the22 “proceedings of the national academy of sciences” found that in fact people living in more diverse areas were more likely to perceive themselves as being part of the same community, regardless of ethnicity.

Glasgow is no stranger to religious division but a great sense of community within each faction stood as the pillar that held the city up despite the religious divide. Today it seems the wider UK

22 “For People in Diverse Areas, Community Identity Supersedes Racial, Ethnic Differences.” n.d. Princeton University. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.princeton.edu/news/2020/05/19/people-diverse-areas-community-identity-supersedes-racialethnic-differences.

is more divided than ever, with tensions constantly rising between religious and national groups due to immigration, the economy, and the general standard of living. In truth this isn’t the case. This country has always been rife with controversy, from the glorious revolution to Irish home rule, from the abolition of slavery to the Falklands war. Our nation has constantly been at moral odds with itself, dividing the populous. So why now does it feel different?

I couldn't tell you the first thing about my neighbours other than a brief description of them that I got from passing them in the stairwell. I know I’m not alone in this with younger generations feeling no need to get to know the people they live nearby. Something my grandparents' generation would find incredibly odd. Even now If I asked my grandmother to tell me about a neighbour from 40 years ago, I could get a long lecture on the person 4 doors down. In fact, a recent study shows that23 “Feelings of belonging to one’s neighbourhood” have reached all-time lows. Some experts blame the problem on social media, others on economic downturns. The truth is that the cause doesn't matter, the lack of a sense of community negatively impacts people. As I stated in an earlier section of this paper, we have evolved to need a community. Community started simply as a method of survival, safety in numbers. This however has evolved, as we have evolved. Humans need community as readily as we need water and air, not having a community can lead to people developing, anxiety, depression, even suicidal behaviours. 24Which in turn influences the wider society.

There are two defined spectrums of culture25, individual and collectivist. Individualist cultures are cultures where people put themselves and their own needs above the needs of the wider community. Collectivist culture is defined as a culture in which people focus on the needs of the group before themselves. I believe that modern architecture is nurturing the former. And as a result, we are losing the sense of community within our society.

As we lose a sense of community in our modern society, we are also losing culture, as cities become more culturally 26homogeneous. We hear today a plethora of reasons why we are losing a sense of national pride; we are told by so-called experts that the reasons for this are economic, political etc. But one reason that I feel is a major factor though, that is never or at least, rarely brought up. Is architecture.

Architecture has been used to define cultures for centuries. From the peaceful, noble Buddhist cultures of eastern Asia to the decadent aristocracy of the west, architecture has mirrored society. Culture has developed around architecture and art as much as it has around religion. Traditional Japanese architecture today is defined as tranquil and serene and is used when designers want to create “zen” spaces, this is in direct correlation with the cultural values of feudal Japan. Modern Japan however, in major cities such as Tokyo, is exciting, vibrant, fast

23 Mohdin, Aamna. 2020. “Britons’ Sense of Community Belonging Is Falling, Data Shows.” The Guardian, February 20, 2020, sec. Society. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/feb/20/britons-sense-of-community-belonging-is-falling-data-shows.

24 Plys, Evan, and Sara H. Qualls. 2019. “Sense of Community and Its Relationship with Psychological Well-Being in Assisted Living.” Aging & Mental Health, July, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1647133.

25 Individualistic vs. Collectivistic Cultures: Differences & Communication Styles Video. 2019. “Individualistic vs. Collectivistic Cultures: Differences & Communication Styles - Video & Lesson Transcript | Study.com.” Study.com. 2019. https://study.com/academy/lesson/individualistic-vs-collectivistic-cultures-differences-communication-styles.html.

26 Lemoine-Rodríguez, Richard, Luis Inostroza, and Harald Zepp. 2020. “The Global Homogenization of Urban Form. An Assessment of 194 Cities across Time.” Landscape and Urban Planning 204 (December): 103949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103949.

paced and modern. And the architecture again mirrors this with large glass buildings that dominate the skyline, promoting a culture of modern workers and western values. Clearly the architecture has been influenced by changing culture. This can be seen everywhere as all cities are seeming to evolve into a modern world where culture is non-existent and modern architecture is no longer unique to a city, no longer influenced and defined by a style unique to any one culture. Skylines are slowly becoming indistinguishable with the only character left in a city being historical buildings that once stood as the heart of a culture. I believe that this movement in architecture is an undisclosed but primary reason for the vanishing sense of community. A study run by the UK government in 2015 found that only 15% of Brits below the age of 25 felt “very” patriotic, as opposed to nearly 50% of citizens above the age of 60. 27 While it’s hard to feel patriotic with current governments, a big part of this drop in nationalism in my eyes is due to the fact that modern architecture is indistinguishable from other modern cities. Culture is under threat.

I believe that we can help reduce this threat by ensuring to consider the area in which the design is to be constructed as well as gathering input from locals. If you were to be hired to design an extension on a client’s home. Would you consult with them before designing the extension? Or would you go ahead and design as you see fit? The answer is obvious, isn’t it? Unless you are given express permission to build freely you are morally obligated to design for their wants and needs. Yet for the majority of projects, projects that will affect the people who live within the city or area that this project will be constructed, we completely ignore their opinions. People will relocate for a number of reasons. Work, family, weather. But architecture is a defining factor. It can really define a city or town. People pay council tax here in the UK to live in a specific place, yet we rarely offer these people a say in their city. People who pay to live in a city should absolutely have the right to a vote on how their city has evolved. By doing this we can help people feel proud of their spaces and communities again. As opposed to being forced to live in a built environment that makes them feel in any way negative. Take Ayr shopping centre for example. My Grandparents are never shy of words of contempt for that place. Claiming it destroyed the centre of Ayr, I asked once if they felt they should have been consulted about such a massive project in the heart of their community and the response was clear. “Yes”.

2.3.2 Historical Review of Architectural Styles

To help progress with my research into what styles should be considered to help improve mental health, I have conducted a review into Architectural styles throughout history (See Appendix A). Of course, I cannot evaluate every single architectural style that has appeared throughout history so instead I have identified key architectural styles to be explored. I assessed the evolution of architectural styles throughout history by examining how cultural, societal, and technological influences have resulted in shifts from one movement to another. By conducting this I have gained a deeper understanding of the factors that define architecture and use this to guide the next stages of the project. My Investigation begins with a quick overview of each style

27 “Are British People Becoming Less Patriotic?” 2015. The Independent. July 15, 2015.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/britain-s-young-people-less-patriotic-than-older-generation-10390185.html.

that I have identified. Looking at some key buildings for each and identifying the styles defining characteristics.

I then explored for each where relevant; the reasons for the shift into and away from the movement as well as giving my own opinion of the movement. By the end of this section my aim was to combine the reviewed architectural styles based on their key characteristics and create a more defined list of three to six styles that still influence architecture today that can be explored more deeply and taken to the public to get evidence of what different audiences’ opinions are on the different styles and what type of emotions or feelings these buildings provoke.

2.4 Chapter Four: Public Opinion

2.4.1 Past Public Survey Analysis

28‘People prefer traditionally designed buildings’, YouGov Survey results were discussed on Dezeen by Rose Etherington. Discussed as a first point is the statistic that out of a selection of four photographs 77% of survey participants chose a traditional style of design when asked to choose their personal preference between traditional or contemporary designs. Robert Adam of Robert Adam Architects said the following about the YouGov results:

This has been proven over and over again.

The preference is not just for traditional residential buildings but for non-residential buildings too including traditional styled office buildings and public buildings.

The statistics won’t change how architects design but they’ll know that they will be doing it with popular disapproval of the public

Architects should design for people who have to live in their buildings

To design traditionally doesn’t mean to lose originality or modern flair.

Upon further analysis of the study, it can be determined that there is not a lot of variation by age, income or region. Further comments about the survey raise concerns that Architects are not truly concerned with what the public thinks and that they are merely concerned with what their architectural peers think and that the survey reveals just how disconnected the ideas of the architect are from the public they so to say serve.

Given the severity of these results and the generalisation that this is an occurring theme across the industry of architectural practice, this comes as a real concern. I believe that there needs to be a real push for people to become the main priority of the design of the buildings around them.

2.4.2 Publishing and Gathering Survey Responses

28 Etherington, Rose. 2009. “‘People Prefer Traditionally Designed Buildings’ - YouGov.” Dezeen. October 16, 2009. https://www.dezeen.com/2009/10/16/people-prefer-traditionally-designed-buildings-yougov/.

Through the platform Survey Monkey, I was able to generate and publish a public survey regarding the emotional responses of our built environment. This was released to the public, architecture and engineering students and professionals. I felt that it was incredibly appropriate for me to create a public survey to create a primary source all about public opinions on the buildings around them (See Appendix B)

In question one I showed six photographs that each represented a style that I had established as being a dominating style throughout the historical review previous. I asked the question of ‘Which building sparks your interest the most?’ 32% of people answered with number one which represented gothic architecture and 23% responded with number six – representing organic architecture and expressing their interest in integrated green infrastructure. When asked in question two to choose the most appropriate words to describe the same building they had chosen in question one the top six buzzwords chosen were: detailed, powerful, textured, organic, inviting and curved. Asking them to address the same set of photographs again, with the question proposed as ‘which building gives you a feeling of boredom’, an incredible 60% of voters chose building number five which represented modern non-residential buildings. This time, they described their least interesting building as giving connotations of dullness, simplicity, industrial feeling, no texture, angular in shape, and heavy. This set of results completely transpires with the themes explored earlier in the document of: modern architecture having a disconnect with the general public, people preferring curved shapes, detail can be powerful and inviting rather than off-putting, and that people don’t want to be disconnected to nature. Unfortunately, 65% of people voted in question three that building number five also reminded them most of the buildings in their nearest city.

In question eleven, the public were asked if they’d be likely to touch the surface of a building with textured and patterned brick formations across its façade. 87% of people agreed that they would physically interact with the building’s surface. The following question asked the same thing but referred it to an image of modern architecture with sleek panelling. 85% of the public did not want to touch or interact with this building. This result explains that people do not care to engage with building’s that lack texture and visual complexity. Ensuring that a building does have these qualities when designing for the future would be a good rule of thumb for creating positive and stimulating relationships between people and the built environment.

In discussion earlier about how, ornament could potentially bridge the gap between the built environment and nature in a time where we should be reminded about the effects climate change is having on nature., the following questions aimed to address this. The public were asked to choose their preference of building between two photographs – both images of a residential block, one image of a plain residential block and the other of an art nouveau detailed façade. 68% preferred the one with art nouveau details and gave an account that the shapes, the colours, textures, and materials all reminded them of nature in some way.

Asked next was a series of questions about thresholds. 96% responded that they were more likely to enter a building with a three dimensional, waving frame around the entrance way as opposed to a rectangular door frame and 74.5% opted to enter a topological style of ornamental façade that waved around the entire front façade of shop as opposed to its various neighbours.

This statistic further emphasises the information discussed throughout that people are more visually interested in a building when it is organically inspired in shape or form or detailing.

Part Three

A Guide for the Future of Architecture

In order to break out of the newfound norm of seeing uninspiring architectural representations around our cities, we must seek out better representation for the people living in and visiting these cities and push for new methodologies to be introduced into the building industry in various sectors. The following chapter proposes a range of concepts for change and then begins to consider how these could be achieved, immediately, in the context of Glasgow.

In this chapter, the aim is to provide a variety of long term and short-term proposals for how we begin to deal with and strategize this integration of organic architecture back into our built environment for the increase of mental health & wellbeing of those in our society and for an increased visual unity between the natural and built environments – for better acknowledgement of our climate crisis.

The following describes an array of common-sense types of suggestions that can begin to be integrated into the longer-term design and build proposals in our industry to secure the desired union described prior. These ideas have the potential to be integrated into educational and professional guidebooks or programs and more permanently in the form of building standards.

2.5.1

Strategy 1: Changing Opinions

Broadening the minds of professionals within the industry

Changing the focal point of ‘good design’

We must advocate for more consideration within the design industry to be about the consideration of the effects that spaces have on people’s mental health and well-being. This framework can be and should be implemented into our universities and educational careers within architecture in the form of modules that explicitly show a concern for the importance of mental health in creating spaces. This is vital to create psychologically effective spaces for the public.

Strategy 2: Form = Function

Buildings shouldn’t just be practical

‘Form follows function’ vs ‘Function follows form’

There needs to be a shift where the ‘beauty’ – represented by the ‘form’ is considered as just as important as the internal space and function of the building. Now, this is not to say that this is a concept that has never been apparent- that would be a false accusation as there are many wonderful architects who do make this priority and many built examples around the globe and in Glasgow have been consciously designed with this in mind. It is merely a suggestion that the

vast majority of buildings being designed are not considered this way, and that is something that urgently needs to change.

30This image of the interior of The Tassel House of Victor Horta in Brussels is the epitome of the idea where function and form are equals. The beauty in the functional staircase rail is not an afterthought – it seems to the user that the design of this piece is imbedded in the overall ethos and atmosphere of the home. The expression of the wooden handrail edge feels expertly crafted for functional comfort. It is intentional, thoughtful and human.

The form=function strategy where the importance of the form in terms of beauty becomes more integral to the outcome of the building design in the future, should be integrated into building regulations where it should be a mandatory standard to consider the visual complexity of a building’s design in accordance with a specific set of rules that contradict the ways of designing without the consideration for the beauty of a building.

Strategy 3: Fight for the Client Reestablishing priorities within the professions

30 Horta, Victor. 2021. “The Tassel House by Victor Horta: An Art Nouveau Masterpiece.” ARAU. July 15, 2021. https://www.arau.org/en/tours/the-tassel-house-by-victor-horta-an-art-nouveau-masterpiece/.

Emphasis on building longevity over short term life

Design advocation for fewer ‘beautiful’ parts rather than more cheaper parts

We must fight to keep the clients goals fixed on more than just cost effectiveness. This Strategy addresses the conflictual triangular relationship between architects, engineers and the client. To fight for the client in this strategy means to ‘fight’ or create a better case for the advocation of beautiful designs from the architect over the pushiness of a structural engineers’ ambitions to reduce ‘decorative’ parts for the concern of reducing costs. This strategy is not implying that costs are not to be considered, but it is suggesting that there needs to be better compromise of creating beautiful elements over removal of beauty to cut costs. This is crucial because of the evidence in previous sections that explicitly raises concerns over the need for visual interest for a better received building. This should be a strategy that is documented within guidebooks in practice when dealing with clients and would require an agreed awareness with other involved AEC members for transparency with regards to project objectives.

Strategy 4: Watch your head.

Take advantage of air space for creative expression on the street

Enable the possibility of designers and developers having excess space to ‘play with’ above ground floor of the streetscape, to provide more interesting variety for people on the street and more incentive for said developers to be creative. Taking this concept and applying it to the realm of Glasgow, considering frequent weather conditions, an appropriate and faster integrated proposal might be to allow building designers to take advantage of creating interesting weather canopies that serve as form = function. This would allow architects to take advantage of the grey areas of a building’s plot line and enjoy them.

Strategy 5: Give the people what they want

Putting aside the bias of what we think people want to see in their cities, always gather people’s personal opinions of what they actually want

Give the public access to up and coming city projects live!

No-one should have the right to disregard people’s opinions who pay to live and experience life in their area of residence because of a contract

The public who are funding the cities should always be involved in the process of designing them This strategy focusses on different determining factors, starting with the point of view that the public pay council taxes to exist in their location of residence. This comes after a simple question that was proposed to members of my family about the place, they live in. They expressed that they resent the place that they live in because buildings in recent years have become so disconnected with the opinions of the people in the area. They associate feelings of being let down and unheard to the way their area has evolved and share the feeling that if they had been questioned or given better opportunity to express their opinion then they would have more pride over the area. After studying a redevelopment proposal in Glasgow’s city center from

2016 and reading the 31public’s comments made about the proposal once rendered images had been complete and released via media outlets, the immense selection of depressed public comments was frightening and understandable; which further solidified this need for more general public involvement and feedback stages across the stages of designing for the public realm.

Strategy 6: Build for tourists

Consider the impact of tourists visiting the city and being drawn to the building

Place making

Buildings must be more characteristic of their surroundings and historical context. Tourists love to see buildings that represent the culture of the place that they are visiting. This can be done by declining the homogenous office building blocks that are erected across every city in the world and design to be more focused on capturing themes in their facades that are relevant to place making

Strategy 7: Consider the experience of living across from the building

How would you feel about waking up and looking at the building every day

This strategy enforces professionals to step away from their own objectives for the building they are designing and truly try to capture the feeling of someone who has to interact with their design on the daily. It suggests the need for more honesty and transparency when designing human-centric buildings. This is a self-reflective process that needs to be encouraged within the workplace.

Strategy 8: Don’t feel constricted by the buildings past

Reuse projects don’t need to be constricted to what’s there

Designers must not feel constricted to limited design freedom when faced with reuse projects. Reuse projects can be exciting and incredibly rewarding and, in some ways, because there is less construction required then the focus can be applied to other areas. This suggests that creativeness should not be capped and that we should find ways through exploring biomaterials for example, just how interesting and broad reuse projects can be.

Strategy 9: Bring back nature

Integrate nature into every design

31 “Bath Street on the up with 12 Storey Mixed Use Plans : August 2016 : News : Architecture in Profile the Building Environment in Scotland - Urban Realm.” 2016. Urban Realm. 2016.

https://www.urbanrealm.com/news/6344/Bath_Street_on_the_up_with_12_storey_mixed_use_plans_.html.

We must intgegrate nature or elements of it into every building that is built. We must do this for better connections with our natural and built environments for the continued awareness of the importance of nature in a time where global climate change is imminent. This can be implemented through, green infrastructure, bio solar roofs, natural inspired shapes and forms on the facades of our buildings etc.

Strategy 10: Bring back masonry

Reinstate the importance of craftsmanship

The industry should reintegrate masonry led skills and job opportunities. This is needed to create better community within the industry and job opportunities and would create a better emphasis on employing local sources or people to do jobs, in turn acting more sustainably.

Strategy 11: Use colour

Don’t always limit the colour palette of a building to its immediate context

Designers need to be more expressive with colours. This is needed in order to create visual interest in a city context. Discussed previously was that the Icelandic survey result that gathered more visually interesting and varied places create better well-beings. This can be implemented simply by broadening our colour palette in conceptual design stages.

Strategy 12: Experiment with texture

Encourage people to touch your building

To create engagement with the public, a building should create opportunity for people to want to come up to its façade and feel the materiality of it. This will automatically create a sense of intrigue and discovery into the place of the building. This is essential for creating better relationships with public buildings and the public who want to use them.

2.5.3 Reuse / Retrofit Guide for Integrating Natural Elements

Bhs Building reuse / retrofit methodology – design strategies for an increased visual unity between the natural and built environment in our city for better acknowledgement of the climate crisis.

(See Appendix C for an existing building study of this building) This section analyses the research conducted until now and provides methods for integrating people centric design elements into the redesign of the building’s skin as part of a reuse agenda. In turn, the objective priority is to create a building that is a representative response to the public’s feedback about what they want to see in their built environment. It addresses the integration of:

Biomaterials

Ornamentation

Green Infrastucture

The Skin

Mackintosh’ Influence

The focus of this strategy is to address the building’s skin. When discussing façades and structural makeup, in the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, these were referred to as the skin & bones. As an homage to Mackintosh and coming from the stance of a purely visual or aesthetic case point, I will continue to discuss my findings in reference to ‘skin’.

In reference to the results of the survey conveyed in part two, broken down and analysed further, the takeaway key elements of the essence of what future ornamental practices should look like are focused as sustainable and ecofriendly practices with art nouveau and art deco style aesthetics. This can further analysed as:

Materials:

• Eco alternatives to durable materials like marble, stone, and wood that provide the same durability.

• Innovative sustainable materials like recycled steel or eco-friendly composites.

• Renewable resources, recycled materials, or reclaimed elements.

Longevity:

• Traditional applications.

Design Elements:

• Embraced organic forms and geometric patterns which promotes natural inspiration.

Sustainability Focus:

• Emphasise energy efficiency, passive design strategies and eco-friendly materials.

• Integration of living walls, green roofs, or plants as natural ornamentation, promoting biodiversity and environmental benefits.

• Emphasis on low-energy manufacturing, locally sourced materials and designs that minimise waste and energy consumption.

When it comes to retrofitting the skin of this building there are two routes to begin this process; removal and reuse of the masonry brickwork that currently makes up the majority of the material of the façade, or to apply partial or full additions on top of the existing brickwork.

Reuse of Masonry – considering carbon emissions

32In order to appropriately evaluate whether a building’s façade recovery is effective compared to it being discarded, a ‘careful dismantling trial’ should be undertaken by a specialist. Following this trial, a decision can be made about the type of technique used for harvesting the bricks which could include the removal of brick panels or as unitary bricks. The amount of embodied carbon measured (kgCO2e/kg input) that becomes added to the brick through either of these processes must be evaluated first. With this in mind, this following suggestion offers a visual retrofit of the façade without the removal of the existing façade.

Ornamentation Introduced

Firstly, we should consider the type and extent of ornamentation that could be effective as part of a retrofit of this existing building. I think that the required strategy to addressing this type of project is based around a few considerations. These considerations should be that design decisions are genuine, organic, sustainable and characteristic of the history of the place whilst respecting the history of the existing site to an extent too.

Large scale ornamentation should exaggerate the essence of the phenomenological spirit of the place. The Gadi House designed by PMA Madhushala in India represents a visual strategy that considers the strategies above and could be implemented in Glasgow.

33Gadi House Arch Daily

Creating a façade that visually ‘speaks’ to or informs the passerby about openings that hide under the transparency of the façade is an extremely effective form of communication without the need for signage or directions on a façade. The undulating form of the bricks if applied to

32 Circular Economy and Reuse: Guidance for Designers. 2023. London: The Institution of Structural Engineers.Pg 246

33 “Gadi House / PMA Madhushala.” 2021. ArchDaily. July 19, 2021. https://www.archdaily.com/965169/gadi-house-pmamadhushala.

the bhs building would enhance the feeling of the building twisting and wrapping around the block. It would also pay tribute to the organic qualities of the preferred styles of architecture gathered from the survey results in part two.

Ornamentation on a smaller scale should show a consideration for detail in elements that are interactive with the public at a ground level. This could include a staircase handrail, window trim, door handles and lighting fixtures. Influencing these might be the flower of Scotland, Charles Rennie Mackintosh’ linework etc.

Consideration for Biomaterials

On the tiled proportion of the bhs building facade, a respectful and transformative design advancement would be to re-tile the façade using a combination of natural shapes, decorative textures and biomaterials. Exhibition ‘This Is No Longer Speculative’ at Material Source Glasgow highlighted an array of future forward biomaterials for construction and designing. One of the featured design elements of this exhibition was Giles Miller Studio tiles. The ‘Eco Range’ of GMS

34 https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/372532200442540411/

35 https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/2181499814454544/

tiles are produced and manufactured by using bi-products from the agrifood industry. The materials utilized within this process include: wine, hemp, tobacco and coffee.

Greener buildings are considered to create better air and thermal performance. Integrated green infrastructure can reach into the pockets in our cities where space is at a premium and air quality is at a serious low. This air pollution in cities can often be trapped in urban street canyons and by introducing green walls this can mitigate such pollutants through biogenic regulation, which a normal façade isn’t able to do. Not only are green elements successful contributors towards these factors but they have scientifically proven benefits towards increased biodiversity and improve our productivity, health and well-being due to tapping into biophilia bonds.

36 gm-admin. 2021. “Coming Soon... The Eco Range.” Giles Miller Studio. April 14, 2021. https://gilesmiller.com/journal/comingsoon-the-eco-range/.

37 gm-admin. 2021. “Coming Soon... The Eco Range.” Giles Miller Studio. April 14, 2021. https://gilesmiller.com/journal/comingsoon-the-eco-range/.

38 Effectiveness of Green Infrastructure for Improvement of Air Quality in Urban Street Canyons

– Pugh, Mackenzie, Whyatt and Hewitt, Environmental Science & Technology, 2012

Sketch Outcome

38 Biotecture. 2023. “Benefits of Outdoor Living Walls.” Biotecture. 2023. https://www.biotecture.uk.com/benefits-of-green-walls/benefits-of-exterior-living-walls/.

Conclusion

Through undertaking this body of research, I have gained a great deal of knowledge into the various subtopics of research that I was hoping to find out more about. I think that I am now more reflective of my own self and in my architectural work too as the cause of this journey.

I have gained some insight into very important themes that upon reflection, wish that I could have known more about earlier on in my studies to be able to give a better account of designing for people-centred designs.

I am very keen to continue to explore the relationship between architecture and psychology in my future and haven completed this project I feel more inclined to own my natural style of organic focussed design, as I now think that it can be proven and shown not just that it looks visually appealing but that it has psychological benefits too.

I hope that the future of architecture addresses some of the problematic issues that are present within the industry today. Completing this body of research should impact my future career for the better and I hope that it has only given me positive insight and desire for seeking change for good within the industry.

Part Four

Appendix A

Architectural Styles Review

1. Classical

1.1 Ancient Greek

1.2 Ancient Roman

Period

500 BCE(BC) in Greece - 300 CE(AD) in Rome

Key Characteristics

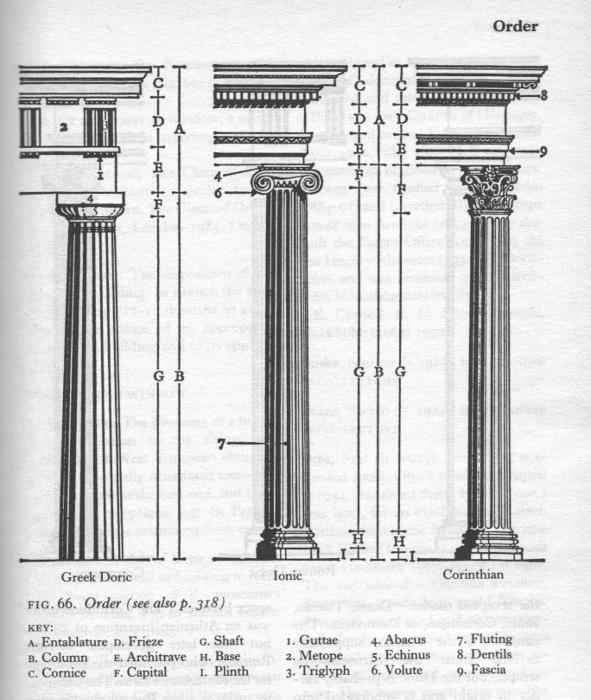

Range of conventional forms, proportions and orders systems. With the relationship between individual architectural parts to the whole building characterising this period. Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders to be emphasised. Defined by ornamentation used. Vitruvius’ beliefs of strength, utility and beauty seen in the architecture of this time period = firmitas, utilitas and venustas. Greeks in this era built columns with no bases nor adornments, they introduced the frieze above columns that allowed for a horizontal space for decorations and/or sculptures. The Romans followed Greek traditions but with added ornamentation. Invention of concrete was a lighter alternative to traditionally used stones up until this point and it was used to build vaulted ceilings and arches.

Key Architect(s)

Marcus Vitruvius

Key Buildings

(1) The Parthenon, Greece. 500 BCE.

(2) The Pantheon, Rome. 113-125 CE

Evaluation

Due to the construction boom in this period, there were a wealth of jobs available for architects, masons and builders with a rippling effect leading to more work being readily available for artisans and labourers. Further, quarrying industries were boosted because of the high demand for stones including fine marbles. Sociopolitics at this time in history meant that the buildings being produced were typically statements of power and sophistication that allowed rulers of cities or regions to flaunt their wealth and significance to said regions. The Parthenon and the Pantheon are key examples of symbolic political prowess and their symmetrical and

harmonious design elements further reflected the regions’ social values of order and balance; a visual representation of the cultural ideals of the time.

Vitruvian beliefs and proportions in accordance with the human body and architectural geometry still play a role in architectural lessons to this day and show a response in the earliest of times in history for the need for a connection between structural integrity and natural growth occurrence, shapes and patterns.

2. Early Christian

2.1 Byzantine

2.2 Romanesque

Period

260 - 540 CE

Key Characteristics

Early Christian churches adopted the design of the Basilica Plan which features a rectangular layout, a central nave and aisles on the sides. Using domes as an architectural expression of roofs showed a move away from flat roofs of earlier structures. Columns and capitals, interior mosaics, introduction of a narthex (an entrance or lobby area became common that served as a transitional space between the secular world and sacred space of the church). Christian symbolism also featured across the architecture, including cross motifs and passages that represented the faith.

Key Architect(s)

Isidoros and Anthemios

Key Buildings

(3) Hagia Sophia, Constantinople. 532 CE

Evaluation

Influenced by Roman Classical, Early Christian paved the way for magnificent cathedrals and basilicas, generally in the Western Empire. The Basilica Plan characteristic of the Early Christian style was influenced by Roman civic buildings that came before. Corinthian and composite columns and capitals were usually repurposed from their use and introduction in the classical era, showing a blend of the two elements; christian and classical. Another take from the Roman

empirical style within the classic period was the incorporation of triumphal arches which symbolised the triumph of Christianity.

Similarly to the Classical period, the Early Christian period of constructing grand churches and basilicas provided a significant economic boost and provided many jobs to a similar catchment of professionals and artisans. Mining, quarrying and trade also boosted again as a demand for mosaic tiling etc came to the forefront as well as the continued use of stones from the period previous. Wealthy individuals and the hierarchy of the church played a crucial role as patrons of the architectural projects completed in this time. The economics of the time were intertwined with the religious, cultural and political dynamics at the time. They reflected the importance of; education and literacy and monasteries played a role in preserving and disseminating knowledge, integration of church and state, cultural identity and integration and a symbolism of power and unity.

3. Gothic & Medieval

3.1 Early Gothic

3.2 High Gothic

3.3 Late Gothic

3.4 Venetian Gothic

3.5 Secular Gothic

3.6 Gothic

Period

500 CE - 1500

Key Characteristics

Medieval architecture can be characterised by thick walls, small windows and functional aspects. Gothic is known for its pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses. Medieval architecture had a great romanesque influence in all of its architectural representations, including religious focussed incorporations of transepts, apses and chapels. Many medieval structures were fortified and defensive. Including battlements, turrets etc. to withstand attacks. Heavy, thick materiality and small windows for limited breach. Gothic replaces the Romanesque’s rounded arch style with pointed arches. A skeletal roof support structure that hosts their ribbed vaults - innovative design that allowed for greater height and more internal space. Decorative elements adorned the Gothic buildings, including Gargoyles and other forms that represented mythical creatures and figures. Biblical narratives and saints began to be

depicted in the form of stained glass windows, which added vibrancy and ethereal qualities to the interior spaces of the gothic buildings.

Key Architects

Jean Bornoy

Etienne de Bonneuil

Heinrich Beheim

Pietro Baseggio

Key Buildings

(4) Notre-Dame, Paris. 1163

(5) Chartres Cathedral, Chartres. 1194

Evaluation

Medieval characteristics can be seen directly influenced by the Romanesque period preceding, with its emphasis on sturdy and extremely large structures. Gothic emerged as a successor to Romanesque in the 12th century and continued into the 16th century. The styles developed within this period marked a departure from the heavy and dark structures of the Romanesque period, introducing a sense of lightness and verticality.

4. Renaissance & Mannerism

4.1 Early Renaissance

4.3 High Renaissance

4.4 Northern Renaissance

4.5 Mannerism

Period

Renaissance 1500 - 1600

Mannerism 1520 - 1580

Key Characteristics

The Renaissance saw major classical influence. Emphasis on mathematical proportions and symmetry from this time included. Domes, arches and a sense of humanism - the similar Vitruvian ideal of a building designed with human principles, this was explored in the sense of human scale elements and perspective. Flattened pilaster columns were seen used as decoration. Mannerist architects purposely distorted these symmetrical pieces from the classical principles seen in The Renaissance style for a play on scale and artistic effect. Their designs featured unconventional compositions, elongated forms, emotional expression, complexity and ornamentation. These could be seen in unconventional arrangement of architectural elements, elongated or stretched appearance, emotions that broke away from the rationalism of the Renaissance and increased intricacy in ornamentation details.

Key Architect(s)

Raphael

Andrea Palladio

Leon Battista Alberti

Agnolo Bronzino

Vincenzo Scamozzi

Key Buildings

(6) Villa Rotunda, Vicenza. 1566

(7) Teatro Olympico, Vicenza. 1580

Evaluation

The Renaissance period evolved as a cause of effect, one effect being the end of The Black Plague. It centered in Italy with particular utilisation of the style in Florence. The style was a classical revival of former Greek and Roman styles as an ambition to revive classical forms and principles following social disruptions and disease. In essence Renaissance marked a revival of certain Classical aesthetics and a return to the principles of ancient architecture whereas Mannerism which emerged slightly later, pushed the boundaries by purposefully distorting these very elements for the sake of artistic expression.

5.2

5.3

Period

5.4 French Baroque

5.5 English Baroque

5.6 Rococo

1600 - 1750

Key Characteristics

Dramatic and ornate designs with emphasis on curves and dynamic forms that create a sense of movement and energy. Use of large domes, ornate columns and elaborate ornamentation. A theatrical effect was often achieved through Baroque architecture with prominent design features emphasising light and shadow. Many Baroque structures were commissioned by European monarchs and the Catholic church which reflected similar previous unity between the built environment and religious and political power. Rococo was known for its lightness, elegance and graceful decorative parts that embraced delicate flowing curves and asymmetry, unlike the symmetry of the Baroque style. Soft pastel colours internally created a more refined and again delicate aesthetic. Shells, flowers and scrolls in ornamentation characterised the Rococo interiors opposing the earlier religious ornamentation. Further moving away from the strong religious influences in Baroque architecture, Rococo’s influence extended into more secular and domestic spaces.

Key Architects

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Francesco Borromini

Francesco Rastrelli

Charles Cameron

Key Buildings

(8) St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City. 1615

(9) Catherine Palace, Russia. 1727

Evaluation

In summary, Baroque architecture is known for its grandeur, drama and political or religious symbolism, greatly influenced from the previous periods of religious symbolism. Different to

this is the Rococo style which is characterised by elegance, lightness, nature-inspired motifs and intricate interiors, celebrated in more of a domestic context.

6. Neoclassicism

6.1 Palladianism

6.2 Classical Revival

6.3 Greek Revival

6.4 Empire Style

6.5 Picturesque

6.6 Sublime

Period

1750 - 1850

Key Characteristics

Classic influenced elements - reminiscent of temples including columns, pediments and symmetry; reflecting classical ideals also by the balance and order demonstrated. Separating from the preceding periods, Neoclassicism used clean lines with restrained ornamentation.

Key Architects

Giacomo Quarenghi

Robert Adam

Giorgio Pullicino

Key Buildings

(10) Altes Museum, Berlin. 1830

(11) The White House, Washington DC. 1792

Evaluation

Neoclassicism as a movement was a reaction to the exuberance of the Baroque and Rococo styles preceding. It was marked by a return to a more rational approach to design that returned to classical forms and simplicity and seeked inspiration from classical antiquity, Greek and Roman architecture in particular. Neoclassicism had a profound impact on Western architecture and persisted well into the 19th century in influence.

7. Eclecticism

7.1 Gothic Revival

7.2 Orientalism

7.3 Beaux-Arts

7.4 Arts & Crafts

7.5 Art Nouveau

7.6 Art Deco

Period

1800’s - 1900’s

Key Characteristics

Eclecticism emerged in the nineteenth century as a reaction against the previous strict adherence to historical styles including Gothic, Baroque or Renaissance etc. The traditional characteristics of the style see a mix of styles; often a combination of elements from the Gothic, Classical or Renaissance styles preceding into one single structure. Architects of this time period often expressed their architecture in a free manner, where they would design according to their personal aesthetic desires. Eclectic buildings usually showcase elaborate ornamentation, decorative elements and intricate designs. Although they saw a mix of styles they still remained to use proportions and symmetry in their designs to create visually pleasing compositions.

Key Architects

Daniel Burnham

Antonio Gaudi

Alexander Jackson Davis

Key Buildings

(12) Royal Pavilion of Brighton, Brighton. 1823