Iceland Review

COMMUNITY, CULTURE, NATURE — SINCE 1963

MUSIC MENTAL NOTE

Unnsteinn’s insights from half a lifetime in the music industry.

SPORT SPARSITY BLUES

Iceland’s only American football team has big dreams.

FOOD BORN AND BREAD

A food history of the humble flatkaka

G et lo s t wit h i n th e c it y

NEWS IN BRIEF 6

ASK ICELAND REVIEW 8

IN FOCUS

HATE SPEECH IN ICELAND 10 PUBLIC TRANSPORT 14

FICTION

THE DIP BY ÖRVAR SMÁRASON 120

PHOTOGRAPHY

FROST 80

A SHOT IN THE DARK 108

LOOKING BACK

TALL TALES AND TREACHEROUS WATERS 60

The 17th-century voyage of Jón the India Traveller.

FROM THE ARCHIVES

THE HEIMAEY ERUPTION 38 Commemorating 50 years since the Westman Islands changed overnight.

SOCIETY

FLOATING THROUGH OBLIVION 26

The therapeutic power of water.

BUSINESS

MAKING IT WORK 70

The uphill battle for equality in the workplace and technology’s latest solutions.

SPORT

SPARSITY BLUES 94

Iceland’s only American football team has big dreams.

MUSIC

MENTAL NOTE 18

TUnnsteinn’s insights from half a lifetime in the music industry.

PEOPLE

MAN OF THE YEAR 42

The Airwaves Music Festival Kicks Off Again.

FOOD

BORN AND BREAD 50

A food history of the humble flatkaka

CONTRIBUTORS

Editor

Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir

Cover photo

Kristján Maack

Publisher

Kjartan Þorbjörnsson

Design & production

Daníel Stefánsson

Annual Subscription (worldwide) €72.

Writers

Erik Pomrenke

Frank Walter Sands

Kjartan Þorbjörnsson

Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Zachary Jordan Melton

Photographers

Golli

Kristján Maack

Erna Rós Kristinsdóttir

Illustrator

Ásdís Hanna Guðnadóttir

Translator Jelena Ćirić

Copy editing Jelena Ćirić

Proofreading

Erik Pomrenke Jelena Ćirić

Zachary Jordan Melton

Subscriptions subscriptions@icelandreview.com

Advertising sales sm@mdr.is

Print Kroonpress Ltd. 5041 0787 Kroonpress

NORDIC SWA N ECOLAB E L

For more information, go to www.icelandreview.com/subscriptions

Head office MD Reykjavík, Laugavegur 3, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland, Tel.: (+354) 537-3900. www.icelandreview@icelandreview.com No articles in this magazine may be reproduced elsewhere, in whole or in part, without the permission of the publisher. Iceland Review (ISSN: 0019-1094) is published six times a year by MD Reykjavík in Iceland. Send address changes to Iceland Review, subscriptions@icelandreview.com .

2 | ICELAND REVIEW FEATURES TABLE OF CONTENTS icelandreview.com

COVER PHOTO: Kristján Maack. Svínafellsjökull.

Find warmth in heart of Reykjavík

Flagship Store - Snorrabraut 56, 105 Reykjavík Online Store - feldur.is info@feldur.is +354 588-0488

Working in media, you spend a lot of time gathering information on the way society works. I read the news, do research, and spend my days talking to people about their lives and their work. It’s a strange type of work sometimes but one that continues to be fascinating, uplifting, enraging, and engaging, usually all at once. Looking from the outside in makes you, if not a jack of all trades, at least someone who could correct the jack from a distance, but definitely master of none. And in forcing you to consider all sides of an issue, also hones your ability to see different perspectives.

Take the city bus. It’s a common cause for complaints. And as a bus user myself, I’ve wondered about how the service seems to have taken a turn for the worse in recent years. The research process for our piece was frustrating for a journalist who kept realising new ways the public transport system was deprived of necessary funds. Then there’s our dive into tech solutions to gender imbalances in the business world, an unpleasant reminder of all the hurdles that remain in the way of women in the workplace, and all the work women are taking on to correct the situation. On the other hand, we found excitement along the way in new plans for intercity transportation, and the ingenious ways startups are coming up with to balance the scales.

In this issue, we explore how rye flatbread, a beloved classic, was born out of Iceland’s history of food scarcity. We run with Icelanders practising the decidedly foreign sport of American football, and dance to the joyous music of Unnsteinn Manuel, the lyrics of which detail his anxiety and creative block. We find time in our busy schedules to experience the serenity of floating and talk with Person of the Year Halli, Iceland’s benevolent tax king, while lamenting the world’s steadfast faith in altruistic millionaires.

In the end, the ability to appreciate the beauty of contrasts-and marvel at the impossible but constant coexistence of extreme opposites-is what allows us to find joy in a world that’s constantly changing. It’s what gives us the power to look modern-day horrors straight in the eye and not let it break us but instead, strengthen our resolve to make this flawed world a little be tter through the power of our own existence.

4 | ICELAND REVIEW

FROM THE EDITOR ICELAND REVIEW · ISSUE 01 – 2023 Editor Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir

Photography by Golli

Join the largest mobile network in Iceland SIM card | 5 GB data 5 GB 50 international min. | 50 sms 2.900 ISK 2.900 ISK SIM card | 10 GB data 10 GB Only data – No calls +354 800 7000 siminn.is / topup siminn.is / prepaid siminn.is siminn siminnisland For more information:

Efling Union members are preparing to strike after chairperson Sólveig Anna Jónsdóttir broke off negotiations with the Confederation of Icelandic Enterprise (SA). Efling has demanded higher wages to keep pace with the rising cost of living and the effects of inflation. While most of the other large trade unions, such as VR and SGS, have agreed to short-term contracts with SA, Efling continues to hold out. The Central Bank of Iceland and the SA warned Icelandic labourers and unions in 2022 that a rise in wages would only exacerbate the country’s inflation problem, while critics like Sólveig argue that workers’ productivity has surpassed their wages since the 2008 economic collapse. Without an agreement, Efling, one of the largest trade unions, is threatening to strike as of the time of writing.

02

Tourists may expect Iceland to be cold, but its residents have been surprised by the unusually low temperatures this winter. According to the Icelandic Met Office, December 2022 was the coldest December in Iceland in 50 years. The average temperature around the country sat at -4°C [24.8°F]. The last time the capital of Reykjavík reached these low temperatures was 1916. The cold weather persisted into January, as Þingvellir reached -22°C [-7.6°F]. While in the capital, these conditions ae merely uncomfortable, in the countryside, they can pose a real threat to travellers as they create conditions for avalanches in the mountains.

03 2023 Handball Championship

In January, Icelanders cheered on the men’s national handball team at the 2023 IHF World Men’s Handball Championship. The national team started strong, beating Portugal in the opening match. As of the time of writing, they have lost against Hungary and Sweden but won South Korea, Cape Verde, and Brazil. Residents all over the country have been watching with keen interest. Even a power outage on the Reykjanes peninsula could not stop the fans. The Search and Rescue Team in Grindavík hosted 30 local residents for the match against South Korea, who were able to enjoy the game thanks to the backup generator.

04 Pollution

Two weeks into 2023, pollution in the capital area exceeded the health-protection limit 19 times. According to the regulations of the Ministry of the Environment, the limit for the entire year is 18 times – meaning Reykjavík surpassed the number in less than one month. With very little wind and an increase in traffic, the nitrogen dioxide from the exhaust of vehicles hovers over the city. Studies have shown that diesel engines contribute significantly to this pollution, leading some critics to blame public bus service Strætó, which operates mostly diesel buses. Minister of the Environment Guðlaugur Þór Þórðarson singled out the bus company, complaining that very few of the fleet of about 160 buses were electric. Strætó pushed back, claiming their buses met industry and environmental standards. Strætó hopes to be fully electric by 2030.

6 | ICELAND REVIEW NEWS IN BRIEF

Photography by Golli Words by Zachary Jordan Melton

01 Stalemate in wage negotiations

Ice land

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 7 MÝ VAT N N ATURE B ATH S pre-book online at m y v at nn a tureb at hs . i s R E LA X E N J OY EXP E RI E NC E

Q1 Can you see Greenland from Iceland?

A common myth you hear sometimes is that on a clear day, from some places in West Iceland, you can see parts of Greenland. This is often attributed to the “lensing” effect of cold air in the polar regions, in which cold air masses can act as a lens and carry light further than usual, over the curvature of the earth.

As great a story as this is, it’s unfortunately not true.

The narrative may have very old origins, going back to the Saga of the Greenlanders. In that story, the settler and outcast Erik the Red is said to set out in search of the land seen by one Gunnbjörn when he went west and discovered “Gunnbjarnarsker.” This skerry, an islet or outcropping of rock in the ocean, was presumably much closer to Greenland than the west coast of Iceland, so it may well have been

Q2 Why is the sand black in Iceland?

Black sand beaches have become one of the images most closely associated with Iceland, and for good reason.

You may already know that the answer has to do with volcanic activity. Iceland, after all, is not the only place in the world with such beaches. Hawaii has several notable black sand beaches, for instance, including Punalu'u and Kehena beaches.

The distinctive black sand shared by these volcanic islands comes from the basalt fragments that accompany a volcanic eruption. Basalt is by far the most common volcanic rock, accounting for about 90% of all volcanic rock on earth. Basalt tends to be dark grey or black in colour because of its mineral composition, which includes high levels of augite and other pyroxene minerals, which tend to be darkly coloured.

possible to see Greenland’s mountains from there.

But not so on Iceland’s mainland. The matter has also been laid to rest authoritatively by Icelandic physicist Þorvaldur Búason. According to Þorvaldur, a 500m [1,640ft] tall hill at a distance of 500km [310mi] appears to us as about the size of a ballpoint pen held at arm’s length. Using some geometry, we can tell that Gunnbjarnarfjall, the tallest mountain in East Greenland, would be invisible to the naked eye from the closest point in Iceland’s Westfjords.

It’s also worth noting that given Iceland’s position relative to Greenland, Greenland stretches further North, South, East, and West than Iceland!

When a lava flow reaches the ocean and comes into contact with water, it cools very quickly and shatters, just like how dishes sometimes shatter in the kitchen if run under cold water directly after heating.

This shattering creates a large amount of fine-grained debris, which is eroded into sand over time.

In many parts of the world, black sand beaches can be formed as a single event and then fade away after the lava flow. But because Iceland is still very volcanically active, the black sand is replenished often, and nearly all of Iceland’s beaches have this distinctive colour.

There are, however, a couple exceptions. Rauðisandur, for example, is a well-known beach in the Westfjords famous for its rustyred colour.

8 | ICELAND REVIEW

ASK ICELAND

REVIEW

Photography by Golli Words by Erik Pomrenke

HIGH QUALITY HOUSES IN THE NORTH OF ICELAND

FNJÓSKÁ NOLLUR

A loft apartment with incredible views of the fjord.

1 bedroom, 1 bathroom, sleeps 2 (4)

HRAFNABJÖRG AKUREYRI

A very well situated, exclusive villa opposite Akureyri.

3 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms, sleeps 6

LEIFSSTADIR AKUREYRI

Exclusive villa in the vicinity of Akureyri.

4 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, sleeps 8

VALLHOLT GRENIVIK

A spacious, luxurious house at the shore.

3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, sleeps 6

SÚLUR NOLLUR

A wonderful holiday house with an elegant interior.

1 bedroom, 1 bathroom, sleeps 4

KRÝSUVÍK NOLLUR

A convenient loft apartment on the Nollur farm in Eyjafjörður.

2 bedrooms, 1 bathroom, sleeps 4 Details and booking www.nollur.is

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 9

Photo: Thomas Seiz

NOLLUR Húsavík AKUREYRI Vík Höfn Eskifjörður

REYKJAVÍK

IN FOCUS Hate Speech in Iceland

As noted by the United Nations, in common language, “hate speech” refers to “offensive discourse targeting a group or an individual based on inherent characteristics (such as race, religion, or gender) and that may threaten social peace.”

When an offensive effigy of Icelandic journalist, athlete, and influencer Edda Falak surfaced at a recent parade in the Westman Islands, it reignited a conversation about misogyny and racism in Iceland. Taking place against the background of a public discourse that seems to be deteriorating, the incident was only one of a series of high-profile cases that inspired the Icelandic government to establish a working group to fight against hate speech.

Working group established

For a long time, Icelandic society was characterised by relative homogeneity, but as it has slowly morphed to become more diverse, there has been no shortage of incidents that shed light on the various prejudices nurtured by the citizenry.

In late June of last year, a working group appointed by the Prime Minister convened for the first time to review indications of “growing hate speech within Icelandic society” and to develop coordinated measures against it (i.e. with regard to race, colour, national origin, sexuality, and gender identity).

In the fall of 2021, the National Queer Organisation of Iceland (Samtökin ’78) saw a rise in reports of harassment of LGBTQ+ people in Iceland, including harassment of children who were perceived as LGBTQ+, who were followed and barked at by groups of harassers.

Other incidents also pointed to growing intolerance of the LGBTQ+ community, including repeated vandalism of a rainbow flag painted outside Grafarvogskirkja church in the city of Reykjavík.

In regards to racism, there are two incidents in particular that most immediately inspired the establishment of the group, and which have most saliently contributed to a feeling that hate speech is on the rise in Iceland.

Lenya Rún Taha Karim

Following the Icelandic parliamentary elections on September 25, 2021, results indicated that Leyna Rún Taha Karim – born in Iceland in 1999 to Kurdish immigrants– had become the youngest parliamentarian in history.

But the victory was short lived.

After a recount in the Northwest constituency on September 26, five seats were reshuffled, and Lenya Rún and four other candidates lost their seats. As a deputy MP, however, Lenya took a seat in Parliament later that year.

Following Lenya’s promotion, the Pirate Party felt compelled to publicly condemn some of the racist remarks that she had been made to suffer. According to a press release in early January, the young politician had faced “relentless propaganda and racism for the mere fact of participating in politics.”

Lenya went on to publish some of the hateful messages that she had received on social media, alongside a selection of comments made in public discussions online following her election. Her story isn’t unique.

10 | ICELAND REVIEW

Photography by Golli

Words by Erik Pomrenke

Adventure Ground Sólheimajökull Mýrdalsjökull Skaftafell Jökulsárlón -TheAurora Ice Cave MAKE SURE IT’S MOUNTAIN GUIDES Adventure Day Tours Hiking Glacier Walk Ice Climbing Snowmobiling Kayaking ATV/Quads BOOK NOW Mountainguides.is info@mountainguides.is

Three Locations

Listasafn

National Gallery of Iceland

Fríkirkjuvegur 7 101 Reykjavík

Safnahúsið

The House of Collections

Hverfisgata 15 101 Reykjavík

Hús Ásgríms Jónssonar Home of an Artist

Bergstaðastræti 74 101 Reykjavík

12 | ICELAND REVIEW

In the Center of Reykjavík

www.listasafn.is +354 515 9600

Íslands

Vigdís Häsler

Later that year, Vigdís Häsler, Director of the Icelandic Farmers’ Association, attended the annual Agricultural Convention (Búnaðarþing) held at Hotel Natura in Reykjavík.

During a photo-op involving a few staff members of the association, who were holding Vigdís in a plank position, the group attempted to convince minister Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson to join them. The minister, having repeatedly refused, reportedly referred to Vigdís as “the black one” (although he has refused to repeat the comment to the media).

In the wake of the incident, Vigdís published a post observing that she “never believed” she would have to sit down and author such a statement: “I have never let skin colour, race, gender, or anything else define me. I have always believed that my work and actions spoke for themselves, but now I feel compelled to speak out about what happened.”

“I know what I heard,” Vigdís stated, “I know what was said. I refuse to be responsible for the words the minister used in my regard; hidden prejudice is a huge social evil and pervades all levels of society. It reduces the work of individuals to colour or gender.”

A meeting with the Prime Minister

Following the outcry that these two incidents inspired, Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir sat down with Lenya and Vigdís in late April to discuss possible ways to deal with racism and xenophobia.

“It was an important conversation, given how difficult the last few weeks have been,” Lenya Rún stated after the meeting. “There have been incidents that have caused concern but that have also served to raise awareness. I’m not happy about these incidents, but I’m happy that they’ve inspired an honest discussion, both in the government and within society.”

The Prime Minister announced the establishment of the abovementioned work group three weeks later.

Working group drafts proposal

On January 3, the working group published its proposal on the government’s online consultation portal (Samráðsgátt), a forum that

invites commentary from interested parties and the citizenry alike.

The document outlines a total of 21 proposals, among them, the allocation of ISK 30 million [$211,000; €194,000] within the 20242026 budget in support of anti-hate speech projects; the allocation of ISK 15 million [$105,000; €97,000] to raise awareness of hate speech in Icelandic society; an online course on the subject of hate speech to be geared towards political representatives (at the state and municipal level), school authorities, teachers, police officers, judges, and others in positions of authority; and increased education on the subject geared towards children.

More troubling remarks

Whether these measures prove effective remains to be seen, with a handful of more recent incidents pointing to their timeliness.

As noted in an article on Kjarninn in early June, a majority of Polish immigrants in Iceland (or 56%) have experienced hate speech in Iceland – and a large part of that group has experienced it repeatedly.

Last summer, for example, Sylwia Zajkowska was selected to portray Iceland’s Lady of the Mountain (fjallkonan, the female personification of Iceland) during the 2022 Icelandic National Day. Sylwia delivered a speech on Austurvellir Square – and recited a poem by Brynja Hjálmarsdóttir – stating that it was “a great honour” to have been offered the role.

Eiríkur Rögnvaldsson – professor emeritus of Icelandic grammar at the University of Iceland – later revealed that he had received an anonymous email following his discussion of Sylwia’s selection to the media. The author of the email maintained that Icelanders simply had a “low tolerance towards people who speak Icelandic with a foreign accent,” adding that they disapproved of this “large influx of foreigners.”

“Which is why people hate that a Polish person was chosen –and it didn’t help that she didn’t know Icelandic.”

“It’s not admirable to send an anonymous email, as it indicates that the author in question knows that they probably don’t have a particularly strong argument, if they’re too afraid to put their name to what they write,” Eiríkur told Mbl.is.

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 13

IN FOCUS Hate Speech in Iceland

Photography by Golli Words by Erik Pomrenke

With ambitious climate goals, rising oil prices, and an energy transition underway, many Icelandic politicians want to de-centre the private automobile. One might assume that public transportation in Iceland would simultaneously see increased support. Sadly, this has not been the case, and, in addition to large budget deficits in 2022, public bus service Strætó has seen significant cuts in service, alongside some of the largest price hikes in recent years.

Cutbacks

In the spring of 2022, Strætó announced in a revised budget report that it would need an additional ISK 750 million [$5.3 million; €4.9 million] to be able to continue operations. Later, in September, it revised this figure to double the amount: ISK 1.5 billion. In a statement at the time, Strætó’s CEO Jóhannes Svavar Rúnarsson cited decreases in revenue due to COVID-19, increasing fuel prices, and increasing labour costs following a the implementation of a shortened work week as key causes of the operational deficit. Strætó ridership, and therefore revenue, peaked shortly before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and has still not completely recovered, with Jóhannes estimating a loss of around ISK 1.7-1.9 billion [$11.9-13.3 million; €11-12.3 million] due to COVID-19.

The budget deficit has also caused a reduction in service, including route reductions, longer wait times, and the elimination of the night bus. The night bus, a weekend service aimed at providing an alternative to taxis for partygoers, was first discontinued due to low utilisation during the pandemic. After a two-year hiatus, the service returned for a trial period this year, running from July to

September, during which time ridership numbers were assessed. Statistics revealed that numbers averaged 14 to 16 passengers per bus, for a total of some 300 to 340 passengers served every weekend. According to Strætó, these numbers fell below acceptable levels, and they decided to discontinue the service once more.

The return of the night bus became a political issue, as it formed one of the election promises of the Progressive Party in municipal elections last spring. In December 2022, Reykjavík Mayor Dagur B. Eggertsson proposed further municipal funding for Strætó to continue its night service at a city council meeting, to the tune of ISK 51 million [$358,000; €330,000]. As of the time of writing, the night bus service is slated to return in 2023, but only within the city of Reykjavík, not the surrounding area. As it stands, none of the additional service reductions are set to be reversed in the foreseeable future.

Funding

Alongside service reduction, a fare hike was also introduced to offset costs. Single tickets alongside both monthly and yearly passes rose in price by 12.5%, one of the largest fare hikes in the system’s history. Where a single ticket previously cost ISK 490 [$3.44; €3.17], it now costs ISK 550 [$3.86; €3.55]. Monthly passes, by far the most popular among residents, rose from ISK 8,000 to ISK 9,000.

In 2021, Strætó’s operating budget comprised a total of ISK 8.6 billion [$60 million; €56 million], of which ISK 1.85 billion came from fares, 4.06 billion from municipalities (Reykjavík by far leading in its financial contributions), 1.03 billion from the state, and 1.6 billion from

14 | ICELAND REVIEW

IN

FOCUS Public Transport

Photography by Golli Words by Erik Pomrenke

other sources, including Pant, a transportation service for disabled people.

To address the dual impact of rising costs and reduced service, some have called for increased state contributions to Strætó. The ISK 1 billion [$7 million; €6.5 million] received by Strætó in 2021 included an additional contribution of ca. ISK 100 million for COVID-19 relief. However, because Strætó went into the pandemic with ca. ISK 600 million in cash reserves, the state contribution for COVID-19 relief was far smaller than it would have been. These funds had been earmarked for the new fleet of electric buses, and now that the pandemic has wiped out Strætó’s cash reserve, a new bus fleet seems a far way off.

Additionally, the annual state contribution of ISK 900 million [$6.3 million; €5.8 million] was last assessed in 2012 and is not indexed to inflation. This means that in terms of the real value of the state contribution, Strætó receives less and less money every year. ASÍ, the Confederation of Icelandic Labour, recently issued a report comparing state subsidies for electric vehicles to state contributions to public transportation. The report showed that in 2021, Strætó received ca. ISK 1 billion in state funding, while state subsidies for EVs totalled ISK 9.2 billion. These subsidies overwhelmingly benefit higher-income earners, who may already be in a position to purchase an EV without a discount. On average, every EV sold in Iceland is subsidised with ISK 1.1 million in state funds, and every plug-in hybrid vehicle with ISK 932,000.

Statistics show a clear correlation between income level and utilisation of Strætó, with 31% of Icelanders in the lowest income

bracket using Strætó daily, compared to 12.3% of the highest income bracket. Similar trends can be seen in age, with both the very young and very old highly dependent on Strætó, in addition to students, renters, people with disabilities, and the unemployed.

Icelandic politicians are rightfully serious about the energy transition, but in order for it to be a just one, public transportation must be granted a more central role.

Making the switch

A recent report on pollution in the capital area stated that already by January 6 of this year, pollution exceeded acceptable levels more times than are permissible in an entire year. This surprising news also called the ageing Strætó fleet into question. In statements on the matter, Minister of Environment Guðlaugur Þór Þórðarson has called for municipalities to cut down on emissions by reducing the number of diesel vehicles.

Although some construed the minister’s comments as blaming public transit for the excessive pollution levels, nearly all agree that the bus fleet needs an update. Very few of Strætó’s current fleet of 160 vehicles are electric, but in the coming months, there are plans to add an additional 25 electric buses to the fleet. The state contribution to Strætó is also set to be reassessed soon, and Strætó board member Alexandra Briem is optimistic that they will be able to increase funding, precisely through the same EV subsidies that have, up until now, only benefited the owners of private vehicles.

A new app

Strætó also introduced a new ticketing app, named KLAPP, in late

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 15

IN FOCUS Public Transport

Photography by Golli Words by Erik Pomrenke

2021. The app itself was originally designed by FARA, a Norwegian developer specialising in ticketing systems for mid-sized European transit systems. Citing security flaws in the previous app, Strætó also began phasing out its paper tickets, giving patrons until March 2022 to trade in any paper stubs for credit on the app. Now, KLAPP is the only way to use the bus system in the capital area, although the rural intercity buses use a separate payment system.

The initial adoption was bumpy, with many passengers unable to board buses because of system errors. The previous app which KLAPP replaced, named Strætó, worked simply enough, requiring the passenger to show the electronic ticket to the bus driver. With KLAPP, a new QR code system was introduced, meaning that passengers now had to scan the ticket on the ticket reader aboard the bus. However, upon scanning, many passengers were greeted by red frowny faces and the error message: “Invalid ticket.” The new app also did away with popular features from its predecessor, including the ability to track one’s bus in real time.

Late in 2022, Strætó also experienced difficulties with its scanners, which stopped functioning. The scanners are currently being replaced at the cost of the provider, and there are plans to soon introduce alternate payment methods onboard, including credit card and phone payments.

Strætó B.S.

Iceland’s public transportation system is run by an entity known as Strætó bs. The “bs.” designates Strætó as a municipal association (byggðasamlag), a public corporation owned by the municipalities of Reykjavík, Kópavogur, Hafnarfjörður, Garðabær, Mosfellsbær, Seltjarnarnes, and Álftanes. Ownership of Strætó is proportional to the population of the municipalities.

Some of the recent frustrations with Iceland’s public transportation system have also called attention to the organisation of Strætó. Strætó’s board of directors consists of six individuals representing the municipalities. Of these six, four belong to the centre-right Independence Party, not a particularly strong supporter of public transportation, and one belongs to the Reform Party, a centrist party that favours market solutions to social problems.

Due to budget cuts, many of Strætó’s responsibilities are contracted out, including maintenance work and also many of the drivers themselves. Some of these dissatisfactions with the management of Strætó have led to conversations about whether Strætó should become more of a transit authority, overseeing and regulating the operations of one or more private transportation solutions. This, however, is not a definite direction.

16 | ICELAND REVIEW

C M Y CM MY CY CMY K IN

FOCUS Public Transport

Photography by Golli

Words by Erik Pomrenke

UNNSTEINN’S INSIGHTS FROM HALF A LIFETIME IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY

It’s the last night of the Iceland Airwaves festival. There have been some good shows and a few bad ones. I’ve stopped trying to adhere to my thoroughly-researched festival plan in favour of a more vibe-based approach. What sounds like fun? As a more-interesting-than-expected act wraps up at Húrra, I ask a friend where we should go next. He suggests we catch a few songs of Unnsteinn’s set at Iðnó. I’d seen Unnsteinn Manuel Stefánsson on stage several times before as part of the wildly popular Retro Stefson (active 2006-2016), but it’d been a while.

When we arrive, a Norwegian act comprised of a blond elf-like singer and costumed dancers is wrapping up. Unnsteinn walks on stage in a black hoodie, looking casually comfortable, accompanied by Sveinbjörn Thorarensen, better known as Hermigervill, in his signature red braids. Despite our resolution to leave after a couple of songs to squeeze in one last show, suddenly we’re not quite ready to leave. A few songs later, the crowd is dancing, jumping, moving together as one, and we’re definitely staying until the end. By now, Unnsteinn has torn off his hoodie and is in a black sleeveless tee and leather pants. He’s spontaneously acquired an orange cowboy hat and brought his cousin on stage as a dancer. Hermigervill has fully entered another realm inhabited entirely by his own beats; his imp-like posture and jerking movements make it seem like he’s not simply playing his synths but conjuring the sounds up through supernatural pathways. Nobody is ready for the show to end and Unnsteinn plays not one but two encores to a rapt audience.

As we head out into the night, I excitedly yell at my companion: “Man, Unnsteinn, who knew? Where has he been, why haven’t I seen him play more?”

MENTAL NOTE

Words by Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir Photography by Golli

18 | ICELAND REVIEW

SPACED OUT

It turns out Unnsteinn has been asking himself the same question. While working on his latest music, the tunes he was playing at the Airwaves gig, he released a podcast, one episode per song. Here’s how he introduces himself:

Dear listener, […] It’s been six years since Retro Stefson’s last gig. So much has happened in my life in these past six years. I had a kid and bought an apartment, built a studio, did a year at Iceland University of the Arts, and another year in a film school in Germany, started a company, a radio station, and yadda yadda yadda. I’m trying to make this list sound like the waves of status updates flowing across Facebook on New Year’s, where people list their accomplishments of the past year. And I’m also using it to flatter my ego and the fact that while I owned and ran a studio that acted as a factory for some of the country’s most popular music, I could barely finish a single song myself. I could help everyone else to write, play, and feel reassured, but getting anywhere with my own compositions, that stayed on the back burner. I’m really good at procrastinating and putting other stuff ahead of my own. And, what might be my greatest talent and biggest flaw, is how great I am at ruminating on things. Thinking. The problem, as those of you who are great at thinking know, is that we’re not as good at doing.

MY GENERATION

It’s not as if Unnsteinn has been in hiding. He’s been on TV and the radio, modelling in advertisements, repping and producing young musicians, running a radio station, and he even appeared as a judge on Iceland’s iteration of The Voice. To the casual onlooker, it seemed like he’d given up on the performing side of music and was settling in comfortably as a mogul in the making. At thirty years and change, he even sounds a bit like a wizened mentor to the young kids. “I’ve been making music professionally for about half my life now,” Unnsteinn tells me. “I communicate with young people a lot in our studios and I work with young people. I think it’s so important.” He doesn’t like to teach though, preferring to act as a sort of guide. “I remember

vividly when I was in school, and grownups would tell me how you were supposed to make music and how not to. I thought that was so unhealthy.”

Unnsteinn explains how he was writing music for a play in the Reykjavík City Theatre when he got to know a young audio tech. It turned out he was in a band called Inspector Spacetime and invited Unnsteinn to come check out their studio. That’s how Unnsteinn found himself with a couple of 20-year-olds, in a studio matching their age, doing music ‘wrong.’ “You don’t really record stuff like that, or so people have always told me. But I visited their studio and they just had a mic that was falling apart somewhere in the corner and we were singing directly into autotune, and it was such a great vibe. It changes your performance. We made a great song and it works perfectly.” He found it liberating.

CH-CH-CH-CH-CHANGES

Being open to new developments is what keeps music alive. “In the history of recorded music, there’s always some new technology that changes everything: autotune, the metronome, drum machines. It’s such an unhealthy perspective to look at a new technology that’s set to change music and simply dismiss it with an ‘ugh, Spotify,’ or whatever.” Unnsteinn’s interests include not only how technology changes music, but also the influence of space, the outside world, and culture. He’s fascinated by how organ music written for Catholics sounds different than what’s written for Protestants, as the size of the churches affects the reverberation. Speaking of cultural impact, there’s the global pandemic. For the older guard of Icelandic musicians, the hardships of COVID-19 led many to rethink their music, and even retire. The younger generation, however, is now entering the industry having only made music on their own, never having played a show in front of people. “They’re making music to dance to, music that’s about being together,” Unnsteinn notes. “It’s music that’s made to be heard in a space, by the people gathered in that space.”

I’VE BEEN EVERYWHERE

During his career, Unnsteinn has tried out several different ways of existing within the music industry. “In 2011, when touring with Retro Stefson, we had a manager, sometimes two, sometimes three. And after I moved on to TV, I started a record label working with younger artists. I went into the big productions and finally, got completely fed up with that side of the music industry.” In his podcast, as well as

20 | ICELAND REVIEW

“It’s been six years since Retro Stefson’s last gig. So much has happened in my life in these past six years.”

his music, Unnsteinn honestly describes his experience of suffering burnout in the work he loves so much. “Now, instead of me releasing music for others, I prefer to teach them how the software works so they can do it themselves. In our studio, we completely switched gears. We were releasing Flóni, Birnir, Young Karin, GDRN - some of the country’s biggest artists. But we switched it up and now we have courses where we teach people how to make music with software.”

Unnsteinn’s studio had built up quite a roster of some of the country’s most popular artists, but when they started the courses, they focused on the least-represented demographic in their circle.

“The courses are just for girls,” Unnsteinn explains. “They had never been a big part of our releases. Some girls would come in and maybe not feel entirely comfortable in our space, it was a ‘boy’ studio. So now, we’ve taught around 60 girls to do it themselves and they’re releasing their own music.” Amongst the alumnae is a newcomer calling herself Lúpína, and up and coming pop artist Una Torfa (though she had recorded music previously).

Unnsteinn explains how they found themselves in a male-dominated environment before course correcting. “With all the guys on our roster, it wasn’t because we heard their music somewhere and thought: hey, let’s go sign this guy. Take Flóni for instance: he was

only at our studio to paint our floors. He played us some of his music and after that, he kept showing up. But it’s a much bigger step for a teenage girl to enter a space like that. So that’s why we started the course.”

SPEAK MY LANGUAGE

Unnsteinn really is good at thinking about things. When I ask him about returning to live music, he launches into a breakdown of the status and history of the Icelandic music industry. The truth is that his ability to work as a creative musician is directly tied to popular trends – and the economy. “With pop music, each genre would usually get like five years at a time,” Unnsteinn muses. “When I was in school, it was indie rock. Then dance music dominated for a while. By the time I was graduating around 2010, 2011, rap was everywhere. And it’s still going.” Unnsteinn puts the longevity of rap music popularity down to streaming services. “I know they say you don’t get much money from Spotify, but if you reach a lot of plays, it’s enough. To build a market, people start making music in their own languages.”

The number of emerging artists focusing on the Icelandic market is best visible in the lack of fresh musical exports from Iceland. “Think about the bands being exported from Iceland right now: it’s

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 21

“I’ve been making music professionally for about half my life now.”

the same ones that we were exporting ten years ago. Kaleo and Of Monsters and Men. There haven’t been many new ones since. Laufey, maybe, she’s breaking through. But with rap, the thing that happens is that the market becomes hyper-localised. It’s like a washing machine, the rap songs coming round and round again, one after the other. If you want to make a new song, it can’t be too far away from the song that you did before that one and it creates a saturation. That keeps rap so popular.”

MONEY, MONEY, MONEY

The trouble with making experimental music is that Iceland’s population, although growing, doesn’t support a touring musician. “If I had stayed in Berlin, I could have done an Unnsteinn tour of Germany, playing for a few hundred people in each venue. When I moved home, we played Arnarhóll on Reykjavík Culture Night, and a similar festival in Akureyri, a few school dances and office parties, you know, the gigs that are available here. And they’re good gigs, fun to play. But then I played during Airwaves and that was the first time this winter that I felt I had like a real concert.”

Doing it for the art is all well and good, but there are practical questions to consider. “I was talking finances with a girl who wants to get into music recently. “I told her there were two questions she needed to ask herself. Are you going to be making Top 40 music that

will get played on the biggest radio stations or are you going to be doing something a little more artsy or experimental? The next thing you need to consider is: will you make music in Icelandic or English? Because if you want to sing in Icelandic, you’re not going to be able to live off making experimental music. It’s possible to make a living in music in Iceland, but you need a solid listener base. You need to appeal to a lot of people.”

LET ME ENTERTAIN YOU

In order to have a career in Iceland, to be able to live off making music, one has to embrace the world of entertainment. Unnsteinn sets a high standard for himself and his music, and for a long time, he wrestled with the idea to become an entertainer. “I used to find the idea difficult,” Unnsteinn tells me, before adding, somewhat selfdeprecatingly: “That was an issue because it’s no fun to hire a selfinvolved artiste from 101 to sing a song at an office party and they’re about to have a nervous breakdown over the possibility of saying or doing something stupid.” Getting over himself was one step to clearing his mental block from making music. But for Unnsteinn, performing live is still stressful. “I get awful stage fright. There’s a difference between playing cover songs and my own music. I do Er þetta ást [by beloved Icelandic pop legend Páll Óskar] pretty often and that’s completely nerve-wracking.”

22 | ICELAND REVIEW

“It’s no fun to hire a self-involved artist from 101 to sing a song at an office party and they’re about to have a nervous breakdown over the possibility of saying or doing something stupid.”

While he can manipulate his own songs in the moment, “if that’s the way the song wants to be,” he feels the pressure to do someone else’s songs justice the way they were written. In the end, Unnsteinn doesn’t have a problem with the struggle. “Maybe making art should be stressful.” While popularity helps with paying the bills, ultimately, Unnsteinn has found chasing it unhelpful in the creative process. “I’ve tried to appeal to a lot of people, and at other times, I’ve tried not to do that. The music I’m making now is completely the kind of music I want to listen to myself. That’s the only thing you can rely on. If I’m going to be making music, this is the music I want to be doing. It’s a specific style and the soundscape is maybe a little aggressive. But I made the decision to spend my time doing exactly this because it gives me pleasure.”

There are all sorts of possibilities in the future but for now, Unnsteinn is living in the moment. “There’s the question if I should sing these songs in English, try for a bigger audience, but I’ve had the best time making and releasing these songs as they are.”

DU HAST (MICH GEFRAGT)

So how would he describe the type of music he’s now making, that he performed at that Airwaves gig? As is to be expected, Unnsteinn has thought a lot about his answer. “Consider Rammstein. If you were to ask what sort of music Rammstein made, your first thought might

be metal, but really, they’re a pop group. If you look at the way they structure their songs, the songs are three minutes, there’s the exact structure of a pop song, including hooks and everything but the soundscape is metal. That’s what Hermigervill and I are doing with this album. We’re making pop music, but the soundscape is techno.”

THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC

The talk turns to Hermigervill, Unnsteinn co-creator and veteran of the alternative music scene in Iceland. Unnsteinn has a clear admiration for the effort and ambition Hermigervill has for his craft. “The music we’re making, he’s getting all the sounds into the synths and playing everything live but if you’re not paying attention, you could just as well assume that he’s DJing. So you have to be a music lover and concertgoer to realise what he’s doing: that it’s a risk and that it’s a live performance.” In contrast, Unnsteinn mentions a recent gig where he and Hermigervill performed at the grand opening of a large company’s new cafeteria. “We were standing there in the corner, and people didn’t really realise what was going on. They just saw a redheaded guy and that guy from The Voice trying to keep the party going.” He chuckles. “We also went to London and did two gigs at an event promoting Icelandic tourism. We’ve done the weirdest gigs, where people aren’t expecting live music. Where music is like a commodity, not an art form.” For a young man with a family and

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 23

“If you want to sing in Icelandic, you’re not going to be able to live off making experimental music.

a mortgage, these gigs pay the bills. But that Airwaves concert felt a little different. “It felt incredibly rewarding, artistically. I realised I have to think about making and playing the music that I want to create, instead of focusing on the bottom line. I have to think about the whole experience, what it’s like to show up to a concert.”

Since Unnsteinn has been working as a professional musician for more than half his life, I ask him: is it no big deal to eke out an existence in such a competitive industry? He laughs in tortured artist: “No, it’s a huge deal, actually. I was talking to a guy about my pension rights recently, and he was telling me all these things I apparently should have known. I just went: ‘Huh?’ The system isn’t really set up to make it easy for you.” But Unnsteinn didn’t get into this because of the money. “Music has given me so much. My son is starting to experience it, he loves singing. So we do that together every day these days. I wouldn’t want to do anything else.” In reality, Unnsteinn does do plenty of other things, amongst them, making TV. “Right now, I’m fiercely immersed in music because I just finished making a TV programme for the past four months. And after I’ll have spent four months making my record, maybe I’ll just want to make TV.”

COMING UP

Unnsteinn recently received an artists’ stipend to make music for a theatre adaptation of Nobel laureate Halldór Laxness’s novel Iceland’s Bell, directed by Þorleifur Örn Arnarsson and featuring a cast consisting entirely of people of colour. During that time, Unnsteinn plans to work on his solo music as well, finishing his album. “I want to get it out as soon as I can, so it doesn’t turn into a record that I just talk about.”

24 | ICELAND REVIEW

“People didn’t really realise what was going on. They just saw a redheaded guy and that guy from The Voice trying to keep the party going.”

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 25 LIVE MUSIC EVERY NIGHT HAPPY HOUR 4-7PM EVERY DAY Ingólfsstræti 3, 101 Reykjavík | Tel: 552-0070 | danski.is IcelandReview_182x120_DenDanskeKro.indd 1 5/7/2019 5:40:40 PM

FLOATING THROUGH OBLIVION

Photography by Golli

Words by Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Photography by Golli

Words by Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Oasis

The word oasis refers to a fertile area in the desert. The essential component of the concept is water, for the area is made fertile because of it. The popular image is a half-dozen palm trees, huddled religiously around a small pond, surrounded by an expanse of sand.

Although there are no smouldering deserts in Iceland, Icelanders, like all peoples, have their oases, albeit purely in the figurative sense. Our oases, like the original referent, are unthinkable without the presence of H2O: our oases are warm water, and we’ve long harnessed the power of geothermal energy to make our existence on this harsh island more bearable.

28 | ICELAND REVIEW I ADVISE YOU TO JUST LET GO.

Consider Snorri Sturluson: the renowned historian, poet, and politician thought to have authored, or at least compiled, portions of the Prose Edda, a vital source for Norse mythology, as well as Heimskringla, a history of the Norwegian kings. Although there’s no way to be certain, Snorri may have found not only refuge but also inspiration in his ancient jacuzzi in Reykholt, one of the oldest and most famous man-made hot tubs in Iceland. The pool, fed by the hot spring Skrifla, was mentioned in the Book of Settlements, suggesting it may have been used as early as the 10th century.

Modern Iceland would no doubt be unrecognisable to Snorri Sturluson, although if one were to resurrect the hoary historian, the best way of easing him back into the chaos of modern life would likely be to set him down at the public pools. Have him strap on a floating hood and a few floatation devices. And allow him to be reborn through water.

PERSPECTIVE

Unnur Valdís Kristjánsdóttir has no recollection of the first time that she visited a public pool – but she has vivid memories from her time in water as a child.

Her mother, whom Unnur describes as “a busy woman,” would often buy herself some free time –much the way that a modern parent would employ an iPad – by allowing her daughter to take long soaks in the bathtub.

“I dreamed of designing a moveable tub,” Unnur remembers, “one that I could use to travel the world. This idea, perhaps, later came to inform my manifesto; it’s an outlandish notion, I know,” she admits.

Unnur began modelling at the age of 15 and although she was somewhat embarrassed about her career in its immediate aftermath, that regret was gradually supplanted by a sense of gratitude. She’d been afforded the opportunity of travelling the world, which gave her a certain distance from and perspective on her native country. Gore Vidal looking across the Mediterranean from Ravello.

Later in life, when grappling with an especially difficult decision – one which she had been musing upon over a period of many days – she decided to take a break and visit the pool. It was there that she

had an epiphany, like Archimedes in his bathtub (“Eureka!”), intuiting, in retrospect, that that epiphany was closely tied to the water.

And from there, a whole culture has sprung forth.

LETTING GO

On the morning of Tuesday, December 20, I tumbled out of bed at 5:25 AM.

I popped open my laptop and did some work, roused the kids, fed and dressed them, and drove the younger one to school, trying impatiently to keep him focused on the task at hand, and inuring him to the idea that, in the modern world, there’s no time to stop to admire the magic of everyday existence. I dropped my mother-in-law off at the car dealership before visiting the doctor’s with my elder son, who yelled hysterically over the prospect of an infected finger (which may have explained the fever), and throughout the day I continued this marathon game of whack-a-mole with my hydra-headed to-do list. All the while, my consciousness seemed to drift, almost incessantly, to the small business that I operate with my wife.

When I finally came to, sometime later that evening, in a parking lot outside a nursing home complex deep within snow-ridden Reykjavík, I was exhausted.

And late.

I rushed out of the car and weaved confusedly through the parking lot, spotting a pedestrian in the moonlight. “Excuse me, is there a pool here somewhere?” I asked. “It’s down there,” the woman replied (something about her inflection suggesting this was not the first time she’d received such a query). Before hurrying onwards, she pointed quickly towards the corner of the complex, at the end of a sloping and slippery driveway.

“Thanks.”

I kicked off my boots in the foyer and was directed towards the locker room, where I met a man who’d recently returned to Iceland from Norway. He asked if this was “my first time,” and I admitted that it was.

“I advise you to just let go,” he offered. “It may seem a little strange at first, this whole thing, but don’t pay it any mind.” I determined at once to heed

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 29

I FELT AS IF I HAD BEEN REBORN; I FELT SO UTTERLY DISORIENTED AND CONFUSED THAT I FORGOT, ALMOST, WHO I WAS.

his words, although something about my physical and mental state felt especially antithetical to the kind of levelheadedness often required to ease into a new experience: my nerves were tingling, my mind was detached, and my gums were gauzy from all the nicotine pouches I had too frequently insinuated below my upper lip. I breathed deeply, tried to relax, undressed, showered, and clambered awkwardly into my bathing suit.

But then – an oasis.

The pool itself was maybe 25 metres [80 feet] long and situated beneath a low ceiling, although I’d later think of it as almost infinite in its extension. There were big windows that looked out towards the apartment complex to the east. The majority of the blinds were up, although I only caught sight of a single person, busying herself within a kitchen. Lanterns lined the edge of the pool and music was playing. These weren’t the kind of mildly off-putting, vaguely oriental tones that so often accompany meditation sessions but the less intrusive, more familiar Nordic ambient: a soft piano on a slightly varying loop.

Unnur stood in the middle of the pool and asked the dozen or so participants to gather round in a circle. She explained that the winter solstice session was a sort of national holiday for Flot, her water therapy practice. It was their “Independence Day.” Unnur talked briefly before handing the stage over to one of her assistants, who continued the introduction with a handful of rather disjointed and digressive ideas, softly intoning some of the more popular spiritual catchwords, which made it difficult to focus.

And then we fastened our floating hoods.

INTO THE ABYSS

Unnur conceived of the idea for the Flothetta (a floating swim cap) in 2012.

At the time, she had tried her hand at various pursuits, before enrolling in the department of product design at the Iceland Academy of the Arts. Her

fascination with health and well-being, combined with her life-long love of water, inspired the product’s design, which originally consisted of a set of leg floats and a single head piece. (The concept has since evolved to include a blindfold, to keep the user’s field of vision in check, and additional leg floats to accommodate different physiques.)

I began to float in the darkness, my body undulating in rhythm with my breathing: each deep inhalation drawing me closer to the surface, which also served to raise the volume of the music: a phenomenon so rhythmic and routine that it felt almost artificial.

A friend of mine had described the affair as “a return to the womb,” but my experience was different; I felt as if I were floating through empty space, sinking into a dark and comforting oblivion. At first, it was relaxing and strange and beautiful but not yet remarkable. That latter feeling only became applicable when two hands reached out to “the soft animal of my body” and gently manoeuvred my limbs through the ether, before cradling me, as if I were a child, in an embrace that felt vaguely angelic.

I began to spin, and although I must have been moving slowly through the water, the conscious sensation was akin to hurtling, almost at the speed of light, through the darkness of space. It was indescribable. When those two arms released me, I began to feel like an astronaut in one of those disaster movies, drifting helplessly from whatever remote station to which I’d been attached. I longed for a lifeline. For the renewed sensation of human touch.

Time moved mysteriously, too.

I drifted in and out of consciousness, at times thinking that I’d fallen asleep, and, at other times, very much inhabiting the present moment; and thankfully, Unnur, or one of her assistants, returned at regular intervals to again cradle me in her arms.

I spent a total of 90 minutes in the water (although that couldn’t possibly be right?) and after Unnur had gently

32 | ICELAND REVIEW

THE CONTOURS OF TIME SEEM TO ALTER IN THE WATER.

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 33

removed my floats, she reorientated my body in the water, pressing me up against the pool wall to recover. I felt as if I had been reborn; I felt so utterly disoriented and confused that I forgot, almost, who I was.

“What was that?”

QUESTIONS

“It was like zooming through outer space,” I told Unnur, over the phone, a few weeks after our session. “Is that common?”

“I haven’t heard anyone mention moving at such high speeds, but that thing you said, about time, that I’ve heard; the contours of time seem to alter in the water.”

One of the things that Unnur and her instructors try to emphasise in their float therapy is not over-curating the experience – to keep it simple and manage expectations – so that each practitioner is at liberty to enter into their own realm.

“We don’t want to force an experience upon you. We want to keep it pure,” she observes.

Unnur explained that the weightlessness served to calm down the senses: to unburden the body and its musculoskeletal system, to achieve a deeper calm.

People often find themselves in this wide expanse, which can be a bit overwhelming. They feel lonely, as if they’re drifting through a void, which, perhaps, serves as insightful commentary on the relationship between the human being and the modern world: we’re always stimulated, always addicted to something.”

Encountering nothingness, Unnur seems to suggest – the modern mind reels.

“Have you experienced such powerful feelings yourself?” I inquire.

“I have. But also, I’ve begun to use float therapy as a kind of exercise in intuition. When I need an answer to something, for example; we often know the answer ourselves but fail to find it amidst the hassle of daily life. And I think there’s something truly of value there, allowing us the opportunity to solve our

34 | ICELAND REVIEW

I DREAMED OF DESIGNING A MOVEABLE BATHTUB, ONE THAT I COULD USE TO TRAVEL THE WORLD.

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 35

36 | ICELAND REVIEW

Ep al Skeifan 6 / Ep al De si gn Kringlan / Ep al I cel andic De sig n Laugavegi 70 www. epal.is

Meet some of Iceland’s finest designers

problems in a gentle manner, as opposed to losing the run of ourselves. There are so many people in positions of authority who are making decisions that affect us all; it’s important that these decisions are made well, with quality and thought.”

“It felt so alien and yet so familiar; as Icelanders, our fate has long been interwoven with water.”

“Yes, our daily trips to the public pools make us semiexperts in water, unlike those who only visit pools once or twice a year. The Icelanders are very quick to relax and trust the water. Foreigners, on the other hand, find it more difficult to let go.”

I told Unnur how the sensation of human touch seemed to

IT FELT SO ALIEN AND YET SO FAMILIAR; AS ICELANDERS, OUR FATE HAS LONG BEEN INTERWOVEN WITH WATER.

elevate the ritual to something almost transcendent.

“There’s so much healing power to touch. We know this when it comes to our children, and we take good care of them, but perhaps we forget as we grow older. It loses its importance. We need it.”

I hung up the phone and returned to the chaos of modern life. But have since, during feelings of distress, returned to that place, where I seemed suspended in oblivion; it reminds me of that Czesław Miłosz quote: “Calm down. Both your sins and your good deeds will be lost in oblivion.”

And there’s comfort in that.

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 37

This year, Iceland Review celebrates its 60th anniversary. To commemorate the occasion, we’ve dug deep in our archives to bring you some highlights of Iceland’s history, through the eyes of contemporary journalists and photographers.

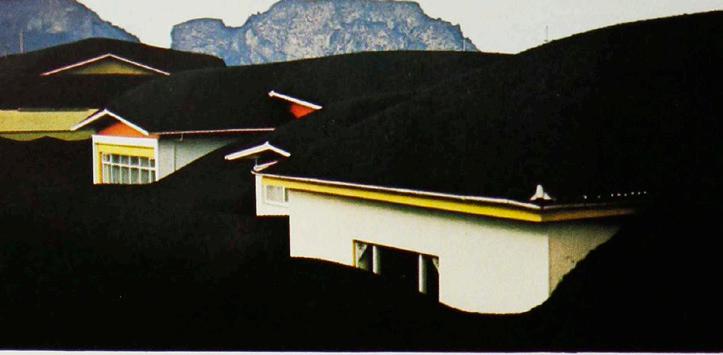

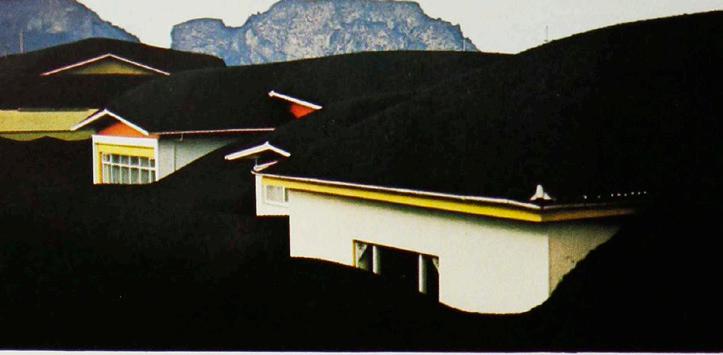

On the morning of January 23, 1973, the fishing village of Heimaey in the Westman Islands awoke to a volcano erupting in the backyard. A fissure a mile-and-ahalf long had opened up about half a mile from the edge of the township. The inhabitants were evacuated in a matter of hours, the sick and elderly going to the mainland by plane and everyone else piling on fishing vessels to escape the lava and ash. Amazingly, no one was injured.

Firefighters, scientists, and geologists stayed behind or travelled to Heimaey to keep the village and the harbour from being destroyed. Pumping equipment was brought in from the mainland and abroad, and ‘suicide squads’ began pumping ice-cold sea water at the leading edge of the lava flow. By the time the eruption had subsided, a 27-metre [90-foot] rock tsunami stood frozen, just yards from the harbour.

From the Archives IR 1973_01

THE HEIMAEY ERUPTION

The volcano – subsequently named Eldfell, or Fire Mountain – remained active for nearly six months. In July 1973, it was announced that the eruption was finally over. While the harbour had been saved, the eastern side of the town was buried under 40 metres [120 feet] of lava, with a total of 112 houses destroyed, either burned or buried entirely.

From the Archives IR 1973_01 THE HEIMAEY ERUPTION

Wordsby Zachary Jordan Melton

From the Archives IR 1973_01 THE HEIMAEY ERUPTION

For nearly six months, the islanders had lived with relatives, friends, or strangers on the mainland, cramped and uncomfortable. As soon as it was deemed safe to return, they began filtering back to their hometown, only to find half of it in complete ruin. They began the long process of rebuilding. More importantly, they used the eruption to their advantage, using the newly created chunks of land to extend their airport runway and harnessing the energy of the volcano to heat their homes.

From the Archives IR 1973_01 THE HEIMAEY ERUPTION

MAN OFTHE YEAR

When Ramp Up Iceland constructed its 300th ramp this November, a curious scene ensued. As Haraldur Þorleifsson, the project’s founder, took centre stage in the Mjódd bus station to make a celebratory speech, President Guðni Th. Jóhannesson interrupted him from the crowd, in what the media would later playfully describe as “heckling.” The President then proceeded to spray-paint over Halli’s initial goal of 1,000 with a new one of 1,500. Later, Halli would tweet, “Since he’s the president, I guess we have to do it.”

The playful exchange captured what many find so endearing about Halli, as he’s often known: a benevolent tech titan who’s still able to take a joke. Much of the exchange also took place on Twitter, of which Halli is both an avid user and a current employee.

42 | ICELAND REVIEW

Words by Erik Pomrenke Photography by Golli

THIS IS HARALDUR ÞORLEIFSSON

IN 2021 HE SOLD HIS COMPANY, UENO, TO TWITTER.

DURING THE SALE PROCESS, HE WAS ADVISED HOW TO LEGALLY AVOID PAYING TAXES ON THE PROFIT.

INSTEAD, HE DEMANDED THAT THE PURCHASE PRICE BE PAID AS SALARY TO MAXIMISE THE TAX HE WOULD HAVE TO PAY.

IN 2021, HE PAID THE SECOND HIGHEST TAX IN ICELAND.

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 43

LIFEBYDESIGN

As a designer, Halli thinks a lot about the decisions that shape the world we inhabit. We take so many aspects of life for granted, be it a building, a coffee cup, or a public transportation system. We see them as a given, as part of our environment, forgetting the choices and circumstances that made them. Halli, however, was not the kind of child to settle for “that’s just how it is” as an answer.

His tech career has allowed him to work wherever he wants, and he has travelled extensively, living and working in places like Tokyo, Buenos Aires, Vancouver, Barcelona, and Rio de Janeiro. Both his travels and design background have made him think very deeply about why cities are laid out in certain ways and why certain buildings lack accessibility, while others don’t. “You can go from city to city,” he says, “and often even just within the same

country, there’s a very stark difference. So it’s very clear that these are all manmade decisions.”

HUMBLEBEGINNINGS

Halli’s journey to becoming one of Iceland’s so-called “tax kings” was not an obvious one. Born with muscular dystrophy which left him fully dependent on his wheelchair by his mid-20s, his family was working-class. Looking back, Halli is fully aware that things could have been different. “Education is definitely the big one,” Halli says, reflecting on the advantages of growing up in Iceland. “In places like the United States, there’s a big difference in education depending on the money you have. And social differentiation begins very early in education, starting in kindergarten. And of course, it’s not just the quality of education, but the network you develop and your social capital as well.”

Having studied philosophy and

44 | ICELAND REVIEW

‘TALENT’ IS MY LEAST FAVOURITE WORD. IT IMPLIES THAT SOME PEOPLE ARE BORN WITH A GIFT. AND THAT OTHERS ARE NOT. IT ' S A LIMITING WORD. GATEKEEPING THROUGH GENETICS. PASSION IS WHAT ACTUALLY MATTERS.

business at university, Halli went on to drop out of a master’s degree in economics. Like so many foundational figures of the tech industry, Halli found it hard to adapt to the daily routines of formal education and work life. But unlike many of his tech peers, Halli hasn’t mythologised his origin story. “It wasn’t really a principled stance at the time,” Halli admits. Thinking back to some of his first jobs, he’s quite candid about the reason he forged a different path: “I just felt I couldn’t show up in a tie every day.”

As Halli was finding his way in the world, he also received some aid in the form of disability payments. “I couldn’t have lived off of them for a long time,” Halli says, “but they did get me through some hard times.” Some of these hard times included being fired from one of his first serious jobs in New York and a difficult period with alcohol and drug use. He also recalls ruefully how he happened to start his first day of

work at CCP, a large Icelandic game development studio, on the same day as the banking collapse in Iceland. But in 2011, Halli sobered up and got married. In 2014, founded Ueno.

Ueno grew out of Halli’s work as a freelancer. Halli scored a lucky break in taking on a project for Google, and as his projects grew bigger and bigger, he realised that he needed to organise a team. Over the years, Ueno grew into a full-service design agency, developing apps, making websites, creating brands, and leading the way in online marketing for some of the biggest names in tech, including Uber, Facebook, Twitter, Apple, Visa, Verizon, and others. Some of their best-known projects include the Google Santa Tracker, the Reuters news app, and Dropbox’s online guide.

When Halli sold Ueno to Twitter in 2021, the proceeds from the sale were enough to send him to number 2 on the list of Iceland’s top taxpayers, the

exclusive list of “tax kings.” Normally, selling off a highly profitable tech company involves stock options and other financial instruments designed at keeping the profit in lower tax brackets than wages. Instead of experimenting with creative bookkeeping, Halli went in the opposite direction, opting to receive the majority of his profit in the form of wages. The highest wage bracket in Iceland is taxed at a marginal rate of 46%, with lower brackets at 38% and 31%. Had Halli chosen stocks or other financial instruments instead, he would have been taxed at a much lower rate of 22%. Not all details from the sale are public, but according to his tax return, Halli reported a monthly salary of ISK 102 million [$718,000; €672,000] throughout 2021, some 46% of which would have been paid in tax.

In talking with Halli, there is no sense of martyrdom or regret. Nor does he seem to have been simply “following the

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 45

PEOPLE CAN BE SUCCESSFUL WITHOUT WORKING HARD OR BEING SMART. BUT NOBODY CAN BE SUCCESSFUL WITHOUT LUCK. AND A LOT OF IT.

46 | ICELAND REVIEW

rules,” impartially acting like everyone ought to. He seems genuinely happy to have the ability to give back.

The largest part of his working life has been with American tech companies. Reflecting on the differences between his home and the United States reveals a deep appreciation for Iceland’s social systems: “In terms of living, Iceland is simply a better place. In terms of work, if you just isolate that part, the US probably has a leg up, but not for the right reasons. It’s a fear-based society. People are afraid to make mistakes, and when they do, there are no safety nets. In a lot of ways, I relate to that American work ethic, but I don’t think we should build a society around it. Everyone is very motivated, but I don’t think they’re happier. In Iceland, because of the social system, there’s more room for life.”

Despite his passion for the principles of social democracy, Halli certainly does not believe he has all the answers for the world’s social woes. Exhibiting his trademark humility, Halli says simply, “I’m not smart enough to have solutions, but I think in general it would be good to level things. We should start with the assumption that it would be good to be more equal, that people who have more should pay more.”

This, it seems, is Halli’s goal: to make Iceland an even better place for living.

RAMPUP

Once Halli was back in Iceland with his family after years of travel, its lack of accessibility seemed both obvious and insupportable. Only now, he could do something about it. Ramp Up Reykjavík started humbly, with the goal to build 100 ramps, mostly in downtown Reykjavík. “It seemed like every year, there was some story about how a person in a wheelchair couldn’t go somewhere on Laugavegur,” he recalls. “The reporter was always shocked, but nothing ever changed, and I remember stories like these going back for decades.”

Now, Ramp Up has expanded its scope from Reykjavík to all of Iceland, with the goal of 1,600 total ramps across the country by 2026. The difference is especially noticeable on Laugavegur, Reykjavík’s main shopping street. Just a year ago, the entrances to many stores, restaurants, hair salons, clinics, and more were blocked by staircases. Now, gently sloping stone ramps, unassuming in their design, can be found throughout the land, allowing people in wheelchairs to access services previously out of reach. Every ramp is a little different, needing to be fitted to the building and surrounding in question. Ramp Up’s success, according to Halli, is largely thanks to the very focused nature of its goal. “In the beginning,” Halli remembers, “we weren’t really sure how it all worked. But now we can do it at scale. It’s complicated and expensive to do as a one-off, but we’ve learned from doing this over and over again.”

“We have a very deep knowledge of this subject now, but we have no idea how to do anything else,” he jokes. The goal of Ramp Up, in short, is to remove any excuse for lack of basic accessibility, making it as easy as possible for the store owner. With a total budget of ISK 400 million [$2.8 million; €2.6 million], half of which is supplied by government funding, Ramp Up handles everything from applying for permits, submitting plans to the city, sending out work crews, working with local municipalities, and everything else. And the reaction has been overwhelmingly positive, with many confessing that they’d wanted to build ramps to their stores for years, but had no idea how to go about it.

However, Halli tells me, as Ramp Up has made progress, they’ve quickly realised that ramps are far from the whole story: “In the beginning, we talked with a lot of people in the disability community. They rightfully pointed out that it’s not just ramps. How wide are the

hallways in a building? Are the restrooms accessible? Are there accommodations for blind and hearing-impaired people? There are so many things that need to be fixed,” Halli says. “If anyone wants to tell me how we could be doing better, I’m always listening.”

ANNAJÓNA

One of the defining experiences of Haraldur’s life was the loss of his mother to a car crash at age 11. He was on vacation at Disney World when his father received the news, but it was only once they arrived back in Iceland that he was told. Her early loss was, of course, a tragedy. But before he lost her, she left a lasting mark on her son that would shape how he viewed the world for the rest of his life. In Halli’s telling, his mother Anna Jóna was like many mothers: “The best in the world.”

His mother imprinted a deep love of the arts in Halli. According to him, she was loving and creative, having worked in set design for films. He remembers how they watched many movies together and what an amazing storyteller she was. It speaks volumes that many of his passion projects now aim at promoting the arts. Upcoming projects include an artists’ residence on the Kjalarnes peninsula and his own musical pursuits, including a guest appearance at this past year’s Airwaves festival and an upcoming album called The Radio Won’t Let Me Sleep, to be released in the spring. For an awkward and depressed kid, the recent time in the spotlight isn’t entirely natural. “I’ve had to learn to be open to failure in a whole new area,” he explains. “It’s a small country, so everyone’s kind of famous, but I’ve gotten a fair bit of attention. It’s been kind of scary. What if the music is terrible? It would be a very public failure.”

This February, Halli will be opening a new café in downtown Reykjavík. Dedicated to his mother, it bears her name: Anna Jóna. With a small theatre

ISSUE 01 – 2023 | 47

A TOURIST ASKED ME RECENTLY WHY THERE WERE SO MANY PEOPLE IN WHEELCHAIRS IN REYKJAVIK. I TOLD HIM HIS COUNTRY HAD THEM TOO, BUT IT WASN'T AS ACCESSIBLE SO THEY STAY AT HOME. SAME APPLIES TO ALL MINORITIES. IF YOU DON'T SEE THEM IT'S BECAUSE THEY ARE HIDING.

equipped with 40 seats, it also aims to become a venue of sorts for small performances and screenings. “It’s an homage to my mother,” Halli tells me. “But something I thought about a lot before opening this café was how I only grew up with her until I was 11. When I think about it now as an adult, it’s such a small slice of her life. I thought about going around to everyone who knew her and asking about her, about their memories of her. But, ultimately, I decided not to, because there’s no way for me to capture her in her entirety. This is an homage to her, but it’s also an homage of my memory of her, of a son for his mother.”

An especially strong memory of his mother stays with Halli to this day, some 40 years later. “Something I keep coming back to is a conversation with my mom I remember very well,” Halli tells me. “We were walking around the city, I think, and she was telling me how everything I saw, everything around me, was man-made. I got such a clear impression from my mother that I could have an impact on the world, that it wasn’t just for me to look at. It was something that I should, that we all should, feel some responsibility for changing.”

LIFTINGTHEVEIL

A popular post featuring Halli made the rounds on social media recently, titled simply “If you’re rich, be more like this guy.” In the comments, a general consensus emerged that cast Halli as the “good guy millionaire.”

Inevitably, the idealisation of Halli is also tied up in romantic ideas of what people want Iceland to mean to them. These ideas portray it as a perfect society, the first nation in the world with an openly LGBT head of state, and the nation that jailed their criminal bankers, if only for a little while.

But to be faithful to Halli’s own social democratic convictions, it is only fair to see him too as someone human, all too human. There is, for instance, the uncomfortable truth that Ueno

made much of its fortune working for American tech companies, many of which are working against precisely the systems which allowed Halli to flourish. Companies like Uber, Tesla, and Amazon have all worked to drive down wages, while fiercely resisting the recent wave of unionisation in the United States. Ueno was, of course, not directly involved in these practices. But nevertheless, wherever Silicon Valley seems to promise novelty and freedom, one cannot help but notice that potentially democracy-destabilising concentrations of wealth seem to follow. Halli was lucky enough to benefit from strong social systems during the hard times of his life, but for many, such opportunities are increasingly being taken away by these tech firms.

Though Halli’s fortune is admittedly more humble, it is difficult not to draw comparisons with other members of the tech elite. In some sense, Halli serves as the inverse image of his current employer, Elon Musk. The child of South African diamond miners, Mr. Musk has likewise benefited from the advantages of his upbringing, though where Musk was born into great generational wealth, Halli was simply born into a strong social democracy. But what truly differentiates Halli from his fellow members of the tech elite is the application of the designer’s eye to his own life as well. Halli doesn’t take the world for granted, nor his position in it. Where others justify their anointed positions through appeals to genius, work ethic, and rugged individualism, Halli openly talks about the social support he’s received, often letting online followers in behind the scenes of his life.

And it’s this kind of online engagement that keeps Halli optimistic about the future of our increasingly digital lives. “I still remember the first chat on a computer I ever had with my cousin on an old 286,” Halli muses, referencing a popular Intel PC model. “Back then, I thought it was going to revolutionise the world in almost