Dear MTASA Members and Friends,

It’s a privilege to be writing to you as the new president of your association, and I sincerely thank you for your support and warm wishes, which have been so welcoming.

On behalf of the MTASA team, we wish you a very happy and rewarding year ahead in your teaching and invite you to stay connected with us as we work to provide essential information and professional learning experiences, advocate and represent you to the wider community, and offer support and inspiration for the vital work that you do.

Stay tuned for more information about our upcoming events, including the first Concert Performance Day for 2025, to be held on Sunday, April 13 at Elder Hall (in partnership with the AMEB). And for those who were unable to attend the Summer Professional Learning Day in January, we are pleased to announce that the popular and informative session on the introduction of the SA Government Schools Voucher Plus Scheme (now applicable to private music lessons) will soon be accessible for online viewing.

I look forward to meeting many more of you throughout the year and working together to enhance and celebrate growth and collegiality in our profession. So please feel free to reach out to me or your MTASA council anytime with any questions or ideas that you have to share.

With warm regards,

Rosanne Hammer President, MTASA

PATRONS : Her Excellency the Honourable Frances Adamson AC, Governor of South Australia, Mr Rod Bunten, and David Lockett AM

PRESIDENT : Rosanne Hammer

VICE-PRESIDENT : Rodney Smith, Wendy Heiligenberg

SECRETARY : Lynne Franks

TREASURER : Samantha Penny

AUDITOR : Australian Independent Audit Services

CURRENT COUNCIL : Rosanne Hammer (President - New 2025)

Rodney Smith (Vice President), Wendy Heiligenberg (Vice President)

Lynne Franks (Secretary - New 2025)

Sam Penny (treasurer), Pete Barter - Chief Mischief Maker and doer of things.

Yong Cheong Lye, Jessica Liu, Emmy Zhou

Melody Men, Elaine Feng (New 2025)

Lishan Xiao (New 2025), Selena Yang (New 2025)

Lynne Gong (New 2025)

EDITOR : Pete Barter

LAYOUT: : Sectrix

MEMBERSHIP ENQUIRIES to the Secretary –

PO Box 4, RUNDLE MALL, SA 5000 Mobile: 0402 575 219 • E-mail: info@mtasa.com.au

ADVERTISING – Please contact the Secretary

Please see the MEMBER information page for the Advertising Price List.

DEADLINES FOR 2025

Contributions to SA Music Teacher are most welcome. All items to be included must reach the Editor (info@mtasa.com.au) no later than : April 30th 2025.

SOME CONTRIBUTIONS GUIDELINES

All text is to be submitted to the Editor for review.

Italics and inverted commas for quotations – text is to be either in Italics or inside inverted commas, not both.

Single inverted commas to be used; double inverted commas only inside single inverted commas.

CORRECTION:

In the previous issue (Winter 2024), the Volume number was cited incorrectly as Vol. 33., Number 1 The Winter 2024 issue is Volume 32, Number 2 of “S.A. Music Teacher” magazine. We apologise for this error. Editor

Welcome from the President Rosanne Hammer

Coming MTASA Events

Member information

Required Professional Learning For Full Members Of MTASA

Working With Children

Check (WWCC)

MTASA Membership Notes

MTASA Advisory Service

The Seven Elements Of Music Mastery

Jazzin’ Around Lead Sheet Interpretation 5

Open Voicings by Kerin Bailey

Bagatelle by Pat Wilson

On The Voices by Pat Wilson

MTASA Summer Professional Learning Day 23rd january 2025

Review: Dr Dylan

MTASA Professional Learning Day 23rd January 2025

Review: Presentation by Wendy Heiligenberg. This is a fine romance by Rodney Smith

Sports Vouchers Plus Provider Information 2025

Vale Dr Doreen Bridges AM, FACE

Jason Goopy

The Alexander Technique

The Need for More Alexander Technique Teachers

Pedagogy Matters

Summer Edition 2025

Rodney Smith

Unlocking Potential: Musica Viva Australia’s Emerging Artist Program

Contacts

Sunday, 13th April 2025

Concert performance day 1 - In collaboration with the AMEB

Venue Time Ticket Elder Hall, University of Adelaide 12:00pm, 2:00pm and 4:00pm Via website : : :

June 2025

Winter Professional Learning Day

STAY TUNED

August 2025

Concert Performance Day #2

STAY TUNED

The following teaching rates are recommended to members by the MTASA Council for 2025.

Full members of the Music Teachers’ Association of South Australia may use the letters MMTA (member of Music Teachers’ Association) as a post-nominal while they are financial members. Interstate Music Teachers Associations are also encouraging their members to use this or a similar post-nominal.

October 2025

Competitions Day

STAY TUNED

MTASA has introduced a Professional Learning scheme for Full members. This commenced on July 1, 2019 when Full members began accumulating their seven hours of Professional Development. The scheme is designed to underpin and enhance MTASA’s established reputation for the professional excellence of its members, ensuring its standards are fully compliant with current educational expectations. These are clearly outlined in the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (visit www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards) and similar documents.

From July 1, 2020 onwards Full members, when renewing their membership, will be asked to tick a box declaring that they have undertaken at least seven hours of Professional Learning during the previous twelve months.

The following examples are provided to give general guidance for Full members about Professional Learning that would be acceptable to MTASA.

These examples represent only a small sample of all the possibilities available to Full members. Generally Full members should feel comfortable about their own choices but in case of doubt you are welcome to contact the Secretary for further advice (info@mtasa.com.au).

Improved music teaching should be a major factor in all activities that Full members wish to count towards their MTASA Professional Learning.

MTASA will undertake random checks from time to time to ensure the system is working properly. So, on very rare occasions a Full member may receive a request from the Secretary for information about their Professional Learning. In such instances you may submit evidence such as certificates, programs, diary notes, recordings and so forth.

Examples of Professional Learning that would be acceptable to MTASA:

1. Online.

Attending a webinar or similar event; undertaking an online e-learning course.

2. Face-to-Face.

Attending a conference, workshop, masterclass or lecture.

3. Formal Study.

Undertaking a qualification or part-qualification delivered by a recognised institution.

4. Personal Research.

Studying books, journals, articles, musical scores, musical theory, analysis, etc., which lead to an example of improved music pedagogy and/or pupil performance.

Self-conducted research leading to a presentation, masterclass or workshop at a conference.

Composing an educational piece of music that motivates a group of pupils.

5. Team Research.

A joint project with others that achieves particular improvements in a training ensemble.

Joint creation of music teaching materials that improve learning in a group of pupils.

Remember! These are only a few amongst many possibilities. MTASA is a community of creatives. You are encouraged to be creative in your Professional Development!

As a member of Educators SA, MTASA can offer benefits to its members. Here are some offers:

Andersons Solicitors offer MTASA members:

• 10% off legal services, in ALL areas.

• Free initial phone conversation with a lawyer.

When contacting Andersons Solicitors tell them you are a member of MTASA, which is a member organisation of Educators SA (CEASA). Visit the website at www.andersons.com.au/.

Credit Union SA has a range of education only offers. Visit the website at www.creditunionsa.com. au/community/education-communitybanking-benefits/ for more information.

Have you fulfilled the requirements for Full Membership? Student members are reminded that Student membership is restricted to four years after which time it is expected that they would be eligible for another membership category, either Full Membership by Tertiary Study or Full Membership by RPL (Recognition of Prior Learning and Experience).

Student members who are ready to upgrade their membership are invited to submit an application form to the Secretary together with the required supporting documents. Criteria can be downloaded from the MTASA website (www.mtasa.com.au) or obtained from the Secretary (info@mtasa.com.au).

New Legislation regarding Child Protection was introduced with effect from September 1, 2019. A ‘Police Check’ is now known as a ‘Working With Children Check’ (WWCC). The Working With Children Check is the most comprehensive check that exists. Anyone found guilty of breaching this legislation can be fined up to $120,000.

People working or volunteering with children in South Australia must, by law, have a Working With Children Check. A DHS/DCSI child-related check will be recognised as a Working With Children Check until it expires.

People need a Working With Children Check if they are in a ‘prescribed position’. This means people who are in paid or volunteering roles where it is reasonably foreseeable that they will work with children; run or manage a business where the employees or volunteers work with children; are employed to provide preschool, primary or secondary education to a child.

A Working With Children Check is needed for all schools (Government, Catholic and Independent).

For further information go to www.screening. sa.gov.au/types-of-check/new-working-withchildren-checks.

Enthusiastic volunteers are needed to help with various jobs at MTASA events. Tasks include setting up the venue, helping with registration at the check in table, ushering, assisting performers, helping with meals, and packing up afterwards.

It is a great way to network and a volunteering certificate will be provided, which will enhance your CV!

For more information, please e-mail the Secretary at info@mtasa.com.au.

In recent years each issue of SA Music Teacher has included an article about music teaching in a country region of South Australia. There are some regions that haven’t been visited yet. If you haven’t done so please write something – it doesn’t need to be very long – and also include a photo. If you have written something before you are welcome to send an update. E-mail the Secretary at info@mtasa.com.au.

Visit mtasa.com.au/index.php/members/becomea-member/ to join MTASA.

Current Full, Student or Associate Members are not required to submit any supporting documentation to continue their MTASA membership. Anyone applying for Full Membership (either Tertiary Level Qualification and Study or Recognition of Prior Learning and Experience) or Student Membership for the first time must fulfil all of the requirements listed and submit the appropriate supporting documentation. Associate Membership is no longer being offered but those who were Associate Members on September 24, 2017, can continue their membership provided they remain as financial members. Full Membership (Recognition of Prior Learning and Experience) has replaced General Membership.

MTASA Members are always encouraged to write to the Secretary about any concerns that they may have. The MTASA Council will consider your request.

To be listed in the ‘The Directory of Teachers of Music’ on the MTASA website as a teacher of theory/musicianship applicants for Full or Student membership must supply evidence of having completed studies in this field to at least AMEB 5th Grade theory/musicianship standard or equivalent. Full, Student or Associate MTASA members wishing to have theory and/or musicianship included in their Directory listing should send copies of the relevant certificates to the Secretary (info@mtasa.com.au).

The Editor is always looking for things to include in SA Music Teacher. Articles can be about any music related topic. If you would like to write an article this is your invitation! A helpful hint, a comment, a joke, a poem, a cartoon, etc. … please e-mail them to the Secretary at info@mtasa.com.au.

Announcing MTASA Partners!

We invite organisations to partner with MTASA on our website. Benefits include advertising via a clickable link and two free tickets to our events for an annual fee of just $100. Please go to our website.

MTASA Members, free. Non-members, $17. Please contact the Secretary (info@mtasa.com.au) about advertising.

You’ve hit a problem in your professional life as a music educator.

Feeling isolated in your role as a music educator? You’re not alone.

The Music Teachers’ Advisory Service (MTAS) is here to offer the support and guidance you need. Whether you’re concerned about a student’s progress, your studio’s business model, or navigating institutional regulations, we’re here to help. When you encounter a professional challenge as a music educator, your first step is to reach out to the Secretary of MTASA. Based on your query, you will be referred to the most suitable MTASA Council member who will then contact you to provide the necessary advice and support.

While MTASA Council members offer their expertise free of charge to support their peers, the Music Teachers’ Advisory Service has an $80:00 hourly fee. This rate is comparable to a single lesson fee, and most issues are resolved within an hour. Please note, this service is not intended for specific instrumental expertise.

Book an advisory Consultant. Supporting you in your private music teaching situation.

Depending on the nature of your query, you will be referred to the MTASA Council member most suitable to advise you… and they will get in touch with you.

FIND OUT MORE at MTASA.com.au

By Pete Barter.

To truly master an instrument or any musical skill, you must refine multiple aspects of musicianship. This is where The Seven Elements of Music Mastery come in.

Just as the Infinity Stones grant ultimate power to those who wield them, these seven elements give musicians complete control over their craft.

The Seven Elements of Music Mastery –The Infinity Stones of Musicianship

Mastering music isn’t about conquering just one element—it’s about balancing all seven. If you focus too much on one, others may diminish. For example, while working on your timing, your technique may weaken, or while developing creativity, your structure might suffer. True mastery means continuously maintaining all seven elements while striving for new heights.

1. Pulse (Timing) – The Pulse Stone (Blue)

Timing is the foundation of all music. A musician with great timing can lock into a groove, stay in sync with a band, and execute rhythms with confidence. Whether you’re a drummer keeping a steady beat, a pianist accompanying a vocalist, or a guitarist strumming along to a metronome, timing is everything.

How to maintain it: Practise with a metronome, play with different time signatures, and perform with live musicians to develop a strong rhythmic feel.

2. Precision (Technique) – The Precision Stone (Yellow)

Mastering technique means controlling your movements, articulation, and accuracy on your instrument. Strong technique allows for fluidity, speed, and effortless execution. However, focusing solely on technique can lead to robotic playing if you don’t balance it with creativity and expression.

How to maintain it: Incorporate daily exercises for finger dexterity, breath control, or stick handling while also applying technique to real musical phrases.

3. Innovation (Creativity) – The Innovation Stone (Red)

Creativity is what separates great musicians from technical robots. This includes improvisation, composition, and unique musical interpretation. However, if creativity is prioritized without structure, performances can feel unfocused or chaotic.

How to maintain it: Set time aside for free improvisation, experiment with new styles, and challenge yourself to compose original melodies.

4. Order (Structure) – The Order Stone (Green)

A musician’s journey must have structure and discipline. Random, unorganized practice will slow progress, while structured practice ensures steady, measurable growth.

How to maintain it: Follow structured practice routines, track progress, and set specific, achievable goals.

5. Expression (Dynamics) – The Expression Stone (Purple)

Playing at a single volume makes music sound flat and lifeless. Dynamics give depth, power, and emotional intensity. Without dynamic variation, performances lose impact.

How to maintain it: Practice playing soft and loud, experiment with swells and accents, and listen actively to recordings that use dynamic contrast.

6. Efficiency (Time Management) – The Efficiency Stone (Orange)

Musicians often feel they don’t have enough time to practice, but time management is about quality, not

just quantity. Effective time management ensures you get the most out of each session.

How to maintain it: Break down practice sessions into focused blocks, prioritizing weaknesses while keeping a well-rounded routine.

(Positive Thinking)

(White)

Mindset is often overlooked but plays a massive role in growth. Confidence, resilience, and the ability to embrace challenges are crucial for long-term success. A musician who believes in their ability to improve will outlast one who gets discouraged easily.

How to maintain it: Adopt a growth mindset, celebrate small wins, and push through challenges with a positive attitude.

The Seven Elements of Music Mastery aren’t something you achieve once and keep forever— they must be continuously maintained. If you focus too much on one, others may weaken. Just as a musician must balance practice between technical exercises, repertoire, and creativity, they must also actively maintain each element to stay at peak performance.

Real-World Application: Practising in Performance Conditions

Tiger Woods famously hits 1,000 golf balls a day leading up to a tour.

This concept applies to musicians, too. Practise in real-world conditions—gigging, performing, and putting yourself in live situations. Playing in different environments, varying temperatures, and even under fatigue builds adaptability, ensuring that when it’s time to perform, you’re fully prepared for anything.

Formula One world champions reach the top not just through speed, but through dedication to detail. They meticulously understand every component of their vehicle, the nuances of each track, and their own physical and mental performance. But while they focus on precision, they never lose sight of the bigger picture—embracing both the forest and the trees. The same principle applies to musicians: mastery comes from refining the small details while always keeping the overall performance in perspective.

Gamification: Making Mastery Tangible for Students

For educators, a great way to motivate students is by gamifying the learning process.

Using physical representations of the Seven Elements of Music Mastery, such as stones, marbles, or tokens, teachers can create a reward system that encourages students to develop each skill actively.

How to apply to your teaching practice:

• Each student starts with no stones and earns them as they demonstrate growth in a particular element.

• If a student has mastered timing, they receive the Pulse Stone, but they must continue proving their timing skills to keep it.

• If a student is excelling in creativity, they receive the Innovation Stone—encouraging them to compose or improvise regularly.

• Teachers can introduce challenges, milestones, and small rewards for collecting and maintaining all seven stones.

This system gamifies the learning process, making it more engaging, rewarding, and structured, while reinforcing that mastery is an ongoing journey, not a one-time achievement.

Wielding All Seven: The Path to Musical Power

Mastering music isn’t just about having good technique or a great ear—it’s about balancing all seven elements. If you have timing but no creativity, you’ll sound rigid. If you have dynamics but no structure, your playing will feel chaotic.

True mastery comes from developing all seven elements in harmony.

Your challenge: Start collecting your seven stones today

Refine your timing. Strengthen your technique. Embrace creativity. Build structure. Control your dynamics. Manage your time. And above all—stay positive.

Because when you master all seven, you’ll have the power to play with confidence, adaptability, and total musical control.

For a printable pdf and gem holder card, Head to Petebarter.com/7Elements

Disclaimer:

The concept of the Infinity Stones is the intellectual property of Marvel Entertainment, LLC and is used here purely as an inspirational framework to illustrate the Seven Elements of Music Mastery. This adaptation is a creative homage to Marvel’s universe and is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or connected to Marvel or its subsidiaries in any official capacity.

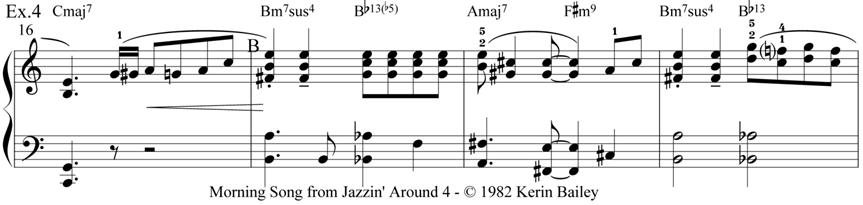

Kerin Bailey

See my previous three articles for preparatory steps to this: 1. RH melody with LH chords; 2. RH melody/ chords and LH bass line; 3. Stride; 4. LH Ballad/Latin styles

Open voicing of a chord is the division of the chord tones between the hands and results in a fuller sonority, and is trickier to do than my previous steps.

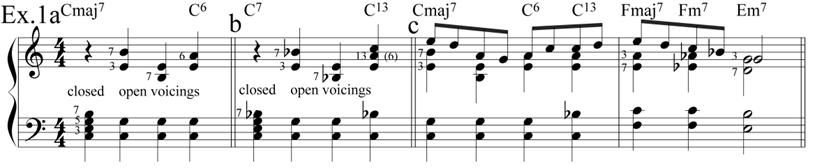

Ex.1a shows the closed Cmaj7 chord followed by the distribution of 3rd and 7th to RH, with 7th on top, root and 5th in LH; beat 3 has the same tones but with the 3rd on top. Beat 4 has 6th (A) on top with the 3rd below. Ex.3b has the flattened 7th (C dominant 7th) but same distribution. When the 6th occurs in a dominant chord it is commonly called a 13th – beat 4. Note the voicing – 7th in LH and no 5th, root doubled on top (optional).

Ex.1c combines these voicings with a simple melody, resulting in a fuller and more agreeable sonority than my steps 1 and 2 – see above.

4th bar is Fmaj7 – 3rd (A) on top and 7th (E) doubled in the melody. Flattening 3 and 7 in beat 2 gives us Fmin7, progressing down a semitone to Em7.

Note – the same voicing rules apply to the 5 main 7th chord qualities occurring in the major scale – major, minor, dominant, 1/2 diminished and diminished – classical harmony!

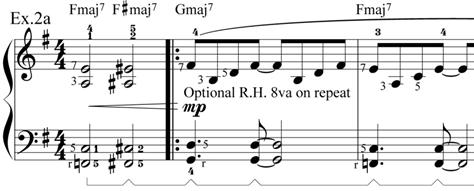

Ex.2a and b are the opening and closing bars of Study in Latin from Jazzin’ Around 2, clearly illustrating the open voicing major 7ths and 6ths. Note – bars 2/3 melody is simply a broken chord of the RH voicing – with added 5th. Following are some examples putting these and other possibilities into practice.

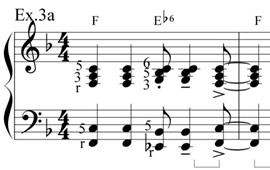

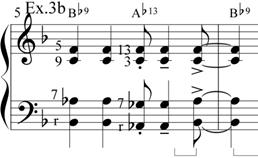

Ex.3a, b and c are excerpts from Groove Time from Jazzin’ Around 4 and demonstrate variations on the basic open voicings.

3a – straight F triad RH, and 6th voicing for Eb6 with added 5th – note the voice leading. 3b has LH 7th shell with RH 9th and 5th in Bb9 chord (no 3rd), and open Ab13 voicing from Ex.1b. 3c – parallel simple dominant 7th voicings, root doubled in melody, no 5th. Though easy to play, these are fairly big chords at this level to capture the driving rock style. Listed in gr.3 AMEB PLF and ANZCA.

Ex.4 is an excerpt from the bridge of Morning Song from Jazzin’ Around 4. Open voicings here contrast with the A sections covered in step 2 article. This is listed in AMEB and ANZCA gr. 6 and the voicings are more sophisticated (and difficult). Bar 16 is the classic open voicing from Ex.1, 3rd on top. Bar 17 – Bm7 suspended 4th (11th); the E in the Bb13 is named b5, also commonly called #11. This is a tritone substitution for E7 and forms a II V7 (bII7) I key change to A major. Note the F#m9 voicing – no 3rd (A); this is the VI chord of the I VI II V (bII7) I progression from 18-20; interestingly, I in bar 20 is Amin7! LH in 17-19 is mostly R/7th shell. Amaj7 LH is a 6th, maj7 (G#) in RH!

Ex.5 is an excerpt of a Beatle’s hit from the album The Beatles for Jazz Piano – excellent arrangements by Steve Hill. This is a bit more complex again, with chord extension dominant and minor 9ths, 11ths and 13ths, and chromatic alterations – #11and aug.5th (+5).

NB: some of the RH voicings are dense and cluster-like; the descending bass line; the 1/8th notes on beats 2 + and 4 + are swung – i.e., same (approximate) values as beats 1 and 3 (this is a common and misleading notation – see my book Rhythm Unravelled ch.6).

So – further ideas for readers to explore to develop the capability for interpreting a lead sheet and creating arrangements of favourite tunes. A reminder also to re-visit Anthony Lilywhite’s informative articles on the Overtone Series. E.g., part 4 in his series, page 18 in the Winter 2023 edition, explains the harmonisation of the major and minor scales and the II-V-I progression.

https://youtu.be/U2O3DkgZCdw Study in Latin tutorial/demonstration

https://youtu.be/60-3qdwMJZ0 Groove Time tutorial/demonstration

https://kerinbailey.com.au/music-shop/jazzin-around-4-piano/ Groove Time and Morning Song

If interested in purchasing the Beatles album buy the 2nd edition – photo of the Fab Four on cover – not the pink cover, which has lots of missing accidentals as I added above.

Bagatelle by Pat Wilson

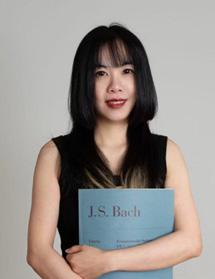

This regular column is a light-hearted way to get to know MTASA Council members, those hard-working people who help to run the Music Teachers’ Association of SA. [Pat Wilson]

[Pronunciation hint for English-speakers = just say “Zo, C-&-G”]

Where were you born? Hangzhou, a city of 12.5 million people in south-east China, not far from Shanghai. Hangzhou, one of the seven ancient capitals of China, is the capital city of Zhejiang province.

What’s your first language? Chinese

And your second language? English – I began learning English in Year 4 at school. What did you look like as a child?

What was your favourite book as a child? “A Fairy GodNanny”

Were your parents musical? Not at all! My mother is a Certified Public Accountant, and my father is an electrical engineer. There was no special emphasis on music in our home. However, my musical auntie Zhang, Jianyun (张,建云)lived only a 20-minute ride away from our house. She was a primary school teacher who also played harmonium (pumped reed organ) for her local church. So my first experience with making music involved putting my little five-year-old fingers on that harmonium and producing sounds. This gave my auntie an idea.

Who was your first music teacher? A friend of my auntie’s (Hu, Laixiang). He taught piano, but only on digital keyboards. I learned with him for a year and progressed very rapidly. He suggested I should transfer to Hangzhou Conservatory. The Conservatory was at least a 50 minute bus ride away from my home, so Saturday piano lessons were much more time-consuming. But revolutionary – because for the first time I was working on a real (analogue) piano, not a digital one. It made such a

difference. At the age of six, I began learning from Professor Chen, Sheng’gang (陈,声钢), at Hangzhou Conservatory… and I worked with him until I was 18 years old. It wasn’t always easy balancing school work with my piano training, especially between Years 7 and 9, when I really struggled with goal-focussed practice at a sufficient level to progress and please my teachers. My mum was sympathetic and supportive; she listened to me and negotiated manageable training levels for me during these tough years.

What’s your primary instrument? Piano

How many instruments do you play? Apart from piano, I did one term studying the bamboo flute (zhú dí). I don’t claim to play it! I also did a single term’s singing study – and the only thing I can remember from it is the melody of Caro mio ben I cannot remember the Italian text; those vowels were very tricky.

How about a picture of your favourite instrument?

Where did you do your tertiary training? I moved to the city of Jinhua, and attended the Zhejiang Normal University for four years, graduating with a Performance of Music degree.

How much practical performance was required in your degree training? We were expected to present two half-hour solo concerts each year as part of our studies.

Can you name a formative teacher of yours?

Professor Chen, Sheng’gang (陈,声钢)

What was your first paid job? In my first year at university, I was hired to help my 10-year-old nephew, who was learning piano but needed some extra tutoring. It was when I worked with him that I realised I really loved teaching, and I wanted to be a music educator. I went on from that to working in a piano shop during my second year at university, where piano lessons were offered.

Composers whose works you love to play? Mozart. What style of compositions do you enjoy teaching? Smooth, legato pieces in a minor key are a special favourite of mine.

Scariest performance? It was my first professional teaching post after graduating from university, and the Hangzhou music school where I was teaching asked me to play the opening piece (Fantasieimpromptu, Op. 66, by Chopin) at the start of their

end-of-the-year student concert. They basically wanted to show off to parents and students what a great teacher they had on their staff. I felt very nervous, but I began this rapid, intricate composition pretty well. I made a fairly noticeable mistake in one chord and immediately I became so aware of the other instrumental teachers in the audience. It really threw me off and I made more little mistakes. There was huge applause at the end of the performance, but I felt shaken by the whole ordeal.

So what do you look like now?

When did you leave China and come to Australia? Seven years ago.

Have you given any solo recital performances in Australia? No; I’ve never been asked to perform. But I’d really like to.

Do you have any handy hints for teachers facing reluctant young piano students? I always chat with them and try to find out what interest they have. Children’s minds jump readily, swiftly channelling emotions from recollected experiences, so I create games and make up little stories based on the music that we are learning. This helps them to enjoy the process; in this way they can begin to interpret and inhabit the music.

Here’s a picture of a recent concert by my students:

Are you a dog person or a cat person? Rabbits!

A picture of your most recent pet?

My dear rabbit, Tutu. Unfortunately, he died recently.

Your favourite food? Oh, I just love cakes. Especially the salted vanilla flavours that aren’t too sweet. I also enjoy extra-spicy hot-pots.

Your favourite recipe? My husband, a digital engineer, is the expert cook in our house.

What’s his best dish? I love his boiled fish (shuí zhŭ yú). It’s spicy and yummy with noodles.

Any hobbies? I enjoy watching movies, especially detective stories and real crime. I also love walking; it’s meditative for me.

Why

by Pat Wilson

A couple of years ago, Julia Hollander (singing therapist, teacher and performer) wrote a fine book called “Why we sing” (Hollander, J. (2023). Why we sing. Allen & Unwin. 368p). Both authoritative and entertaining, it mixes Hollander’s rich personal experiences with scientific research, history, psychology and artistry to address a range of intriguing questions such as:

• Why do parents sing to their babies?

• How is it that some people who have lost the power to speak can still sing?

• Can singing assist recovery from Long COVID? hinking about the breadth of material Hollander covers in her excellent book prompted me to make a quick off-the-top-of-my-head list of reasons why we sing and why our students want to sing. Inspired by her approach, I have added a couple of scientific references to each topic for all you singing geeks out there (you know who you are!) who love to know the reason why.

Before we embark on another year of teaching singing, it’s good to remember just how wonderful and powerful our artform is.

Singing is just plain good for you!

Singing can help you beat stress

Singing can help lower cortisol and relieve stress and tension. The brain releases endorphins and oxytocin when people sing, which can help lower stress and anxiety levels.

Hurst, K. (2014). Singing is good for you: An examination of the relationship between singing, health and well-being. Canadian Music Educator, 55(4), 18-22.

Daykin, N., Mansfield, L., Meads, C., Julier, G., Tomlinson, A., Payne, A., ... & Victor, C. (2018). What works for wellbeing? A systematic review of wellbeing outcomes for music and singing in adults. Perspectives in public health, 138(1), 39-46.

Singing can stimulate your immune response

Singing can boost your immune response, helping you to fight off illnesses. Singers showed higher levels of immunoglobulin A, an antibody secreted by the body to help fend off infections. Listening to music (without singing along) reduced stress hormones but didn’t stimulate the body’s immune system.

Kreutz, G, Bongard, S, Rohrmann, S et al. (2004). Effects of choir singing or listening on secretory Immunoglobulin A, cortisol and emotional state. J. Behav. Med. 27(6), 623-635. doi: 10.1007/s10865004-0006-9

Singing increases your pain threshold

Research has demonstrated that singing, drumming, and dancing in a group triggers the release of hormones that raise your pain tolerance in ways that just listening to music cannot.

Dunbar, R. I., Kaskatis, K., MacDonald, I., & Barra, V. (2012). Performance of music elevates pain threshold and positive affect: implications for the evolutionary function of music. Evolutionary psychology, 10(4), 147470491201000403.

Irons, J. Y., Sheffield, D., Ballington, F., & Stewart, D. E. (2020). A systematic review on the effects of group singing on persistent pain in people with long-term health conditions. European Journal of Pain, 24(1), 71-90.

Singing may improve snoring

Regular singing changes the way you breathe, even when you’re not singing. Researchers interviewed the spouses of choir members, along with the spouses of people who don’t sing., and found that significantly fewer choir members snored. This led them to recommend regular singing as a potential treatment for snoring. Studies have also shown that people who play wind instruments also snore less than the general population. These findings have prompted the suggestion that singing and playing wind instruments might be helpful for people with obstructive sleep apnea.

Russell, J., ... & Hopkinson, N. S. (2016). Singing for Lung Health—a systematic review of the literature and consensus statement. NPJ primary care respiratory medicine, 26(1), 1-8.

Goldenberg, R. B. (2018). Singing lessons for respiratory health: a literature review. Journal of Voice, 32(1), 85-94.

Singing helps to develop a sense of belonging and connection

Singing together with others produces the same kind of camaraderie and bonding that players on sports teams experience.

In a study involving 11,258 schoolchildren, researchers found that children in a singing and musical engagement program developed a strong sense of community and social inclusion.

In a 2016 study involving 375 adult participants, researchers found that people who sang together in a group reported a higher sense of wellbeing and meaningful connection than people who sang solo.

One of the neurochemicals released when people feel bonded together is oxytocin. Spontaneous, improvised singing causes your body to release this feel-good hormone, which may help give you a heightened sense of connectedness and inclusion.

Forbes, M. (2024). Addressing the global crisis of social connection: Singers as positively energizing leaders who create belonging in our communities. Voice and Speech Review, 1-17.

Camlin, D. A., Daffern, H., & Zeserson, K. (2020). Group singing as a resource for the development of a healthy public: a study of adult group singing. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 1-15.

Singing enhances memory in people with dementia

In addition to simple enjoyment of singing, increased social inclusiveness and improvements in relationships, memory and mood have been noted in dementia sufferers participating in singing activities, assisting patients to accept and cope with dementia.

Osman, S. E., Tischler, V., & Schneider, J. (2016). ‘Singing for the Brain’: a qualitative study exploring the health and well-being benefits of singing for people with dementia and their carers. Dementia, 15(6), 1326-1339.

Thompson Z, Baker FA, Tamplin J, Clark IN. (2021) How Singing can help people with dementia and their family care-partners: A mixed studies systematic review with narrative synthesis, thematic

11;12:764372.

Vella-Burrows, T. (2012). Singing and people with dementia. Canterbury, UK: Canterbury Christ Church University.

Singing helps with grief

Through breath and vibration, the act of singing helps us connect with other people as well as our own emotions, effectively helping to metabolise grief, both individually and collectively. Barbara McAfee, in “Singing through grief”, (https:// fullvoicebook.wordpress.com/2018/07/19/singingthrough-grief/) says:

”Singing together gets us connected to each other on a visceral level – through breath and vibration. It also awakens our emotions and softens our defences. There is also great power in giving voice to our tears. Many of us weep silently if we weep at all.”

Fancourt D, Finn S, Warran K, et al. (2022). Group singing in bereavement: effects on mental health, self-efficacy, self-esteem and well-being. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 12, e607-e615.

Young, L., & Pringle, A. (2018). Lived experiences of singing in a community hospice bereavement support music therapy group. Bereavement Care, 37(2), 55-66.

Singing helps to improve speaking ability

Singing is often used as an assistive therapy in autism, Parkinson’s disease, aphasia (post-stroke), stuttering and similar speech-related problem areas. But its benefits extend to spoken vocal range extension, speech fluency, and confidencebuilding for public speakers.

Wan CY, Rüber T, Hohmann A, Schlaug G. (2010). The therapeutic effects of singing in neurological disorders. Music Percept., Apr 1;27(4), 287-295.

doi: 10.1525/mp.2010.27.4.287. PMID: 21152359; PMCID: PMC2996848.

Glover, H., Kalinowski, J., Rastatter, M., & Stuart, A. (1996). Effect of instruction to sing on stuttering frequency at normal and fast rates. Perceptual and motor skills, 83(2), 511-522.

Barnish, J., Atkinson, R. A., Barran, S. M., & Barnish, M. S. (2016). Potential benefit of singing for people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Journal of Parkinson’s disease, 6(3), 473484.

Effectiveness of Rhythmic Singing Training Program on Emotion Regulation of Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Empowering Exceptional Children, 12(2), 12-21.

& Wan, C. Y. (2010). From singing to speaking: facilitating recovery from nonfluent aphasia. Future neurology, 5(5), 657-665.

And now, for a little New Year’s treat–some of my favourite quotes from the last five centuries about the benefits of singing…

As long as we live, there is never enough singing.

Martin Luther (1483-1546) German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter & Augustinian friar

He who sings scares away his woes.

Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616) Spanish novelist, playwright & poet

Even if you can’t sing well, sing. Sing to yourself. Sing in the privacy of your home. But sing.

Rebbe Nachman (1772-1810) Rabbi Nachman, founder of the Breslev Hasidic movement

I don’t sing because I’m happy; I’m happy because I sing. William James (1842-1910) American philosopher & psychologist

Words make you think. Music makes you feel. A song makes you feel a thought. Yip Harburg (1896-1981) Broadway lyricist, songwriter and poet

Singing is a way of escaping. It’s another world. I’m no longer on earth.

Édith Piaf (1915-1963) French chanteuse

To sing is an expression of your being, a being which is becoming. Maria Callas (1923-1977) American-born Greek operatic soprano

Singing is like a raincoat for your emotions.

(Sammy Davis Jr.). (1925-1990) American singer, actor, comedian & dancer

The voice is an instrument of healing, peace and beauty.

Placido Domingo (1941- ) Spanish opera singer & conductor

When you sing, you open up a part of your soul.

Carole King (1942- .) American singer & songwriter

Music has healing power.

Elton John (1947- .) Singer, songwriter, composer & pianist

Singing provides a true sense of lightheartedness. If I sing when I am alone, I feel wonderful. It’s freedom.

Andrea Bocelli (1958- ) Italian tenor

by Pat Wilson

Nattily suited and armed only with an iPad, pianist and early-career researcher Dylan Henderson established a stimulating atmosphere for musicians and music educators in his two Keynote addresses. Drawing upon an impressive breadth of research, much of which flowed from his recently completed doctoral thesis and performance work, he headlined a stimulating day of research, observations and practical outcomes focussed on revealing the romantic soul embedded within a range of romantic music styles.

Drawing on a dazzling array of sources – poetry, paintings, literature, as well as music – Henderson’s presentation was remarkable for the diversity and quality of his PowerPoint pictures. Text was rare. There were numerous sections of Chopin scores which he analysed with forensic energy. A variety of paintings, etchings, mezzotints and sketches relevant to each section of his discussion tumbled onto the screen. It became an immersive visual cascade of 19th century life and art.

First KEYNOTE address:

Espaces Imaginaires and the Romantic Imagination: Chopin’s Damper Pedal and the Haze of Dreams

Starting by quoting a Polish poet, then showing the Eugène Delacroix painting, Portrait of Frédérick Chopin and George Sand (1838), all wavy hazelnut hair and angst, Henderson built a well-reasoned foundation for the concept of imaginary places (espaces imaginaires) removed from the here-andnow, and the ways in which artists of the mid-19th century conceived and realised them. The work of poets, composers and painters of the day reflected a sense of existence in two planes – the “here” and the “there” - “The dream land of poetry became his true homeland.” So, what’s all this got to do with Frédérick (or Fryderyk) Chopin, let alone his damper pedal?

Liszt spoke of Chopin’s pedalling, calling it “incomparably artistic”. Marmontel (Antoine François Marmontel, author of Histoire du piano et ses origins de la facture sur le style des compositeurs et des virtuoses) praised Chopin and his pedalling technique - “Where Chopin was entirely himself”. “No pianist before him has employed the pedals alternately or simultaneously with so much tact and ability.” The ability to deploy damper pedal, particularly on the Pleyel piano of

his day, enabled Chopin to add a veil of magic and mystery to his sound. This Aeolian pedalling, Henderson explained, requires more frequent and judicious pedalling to achieve its desired result while preventing blurring of the sound.

Pedal markings were examined in Chopin’s Mazurka in B flat (Op.7 No. 1, bars 37-65).

A recording of the same passage played on an 1819 Graf piano, an 1846 Pleyel and a 2016 Bösendorfer clearly illustrated the difference between damper mechanisms of 19th century pianos and contemporary pianos, underlining the necessity for today’s Chopin interpreters to be sensitive to the tonal quality of instrument for which this ethereal music was written. Henderson observed that on a modern instrument, it was necessary to use two half-pedals to achieve an equivalent effect.

Henderson examined in detail a range of Chopin works - Prelude in A major (Op.28 No.7); Mazurka in B minor (Op.24 No.4) - with particular focus on the pedalling marks. You didn’t have to be a Chopin geek to be fascinated by his ideas and observations. Once the sense of ethereality and “other-ness” evoked by Chopin’s music and its pedalled markings came to the fore, Henderson’s language shifted gear. Descriptions of sounds included stains, wisps, perfumes, premonitions, pale ghosts, carillons, vapours, Gothic phantasmagoria, pearls in a golden vase, silvery half-tints of an evening twilight and smoke… a flood of 19th century Romantic-era descriptors

Reminding us of the transience of music as an artform as compared to painting and poetry, Casper David Friedrich’s painting “The dreamer” (1840) and Joseph Severn’s painting “Portrait of John Keats listening to a nightingale” (1845) were added to our sensory input. I admired Henderson’s ability contextualise his musical scholarship with the literature and visual arts of the same era, presenting an integrated aesthetic whole.

“A seer; a true artist capable of channelling the transcendental”, was a quote which I think Henderson applied to painter Joseph Severn. The same words could surely be applied to Chopin himself, in his passionate quest for an evocation of that dreamy landscape of our emotional imagination.

Dr Dylan Henderson’s first Keynote address alerted the audience to his breadth of scholarship, so we were prepared for the appearance of moonlight and silver in mid-19th century art, literature and music, with a particular examination of Chopin’s sonic palette, thanks to the uniqueness of the Pleyel piano’s design. And we were showered with Romantic cascades of visual art, literary references and poetry, together with a horde of similes and metonyms relating to Chopin’s “silvery” sounds. Although I must confess to being unprepared for the exquisite excess of “small fairy voices sighing under silver bells”… you simply don’t forget phrases like that in a hurry.

Henderson’s careful examination of the “how” and “why” of Chopin’s very specific Romantic-era sound qualities began with an examination of the pianos produced by French instrument makers Pleyel et Cie. Their pianos were said to possess a “bright and silvery” sound in their upper registers, a “penetrating” middle and a “vigorous” tone in their lower registers. Manuel Garcia’s famous observations on vocal registers were acknowledged as influential in this area.

Picking up on that “silvery” adjective, Henderson then connected it to the idealised vocal quality of bel canto opera and art song singers of the mid 19th century. Famous singers’ names which were dropped included Giuditta Pasta, Luigi Lablache, Giovanni Battista Rubini, Henriette Sontag and Maria Malibran. Contemporary descriptions of the silvery quality of these singers’ voices were quoted; the prose became rhapsodic. A personal favourite of mine: “she seemed to breathe the fragrance of fresh flowers”.

This led to a fascinating table comparing the tonal qualities of five different pianos - an 1819 Graf, an 1846 Pleyel, an 1853 Erard, a 2010 Steinway and a 2016 Bösendorfer – with specific reference to the performance of Chopin’s piano compositions.

Observing that the tone of Pleyel pianos were seen as especially evocative of the human voice, Henderson analysed the “silvery” tonal qualities in a variety of Chopin works: Larghetto from Concerto in F minor (Op.21); Nocturne in B flat minor (Op.9 No.1); Berceuse in F sharp major (Op.60); Etude in A flat major (Op.25 No.1); Mazurka in B flat minor (Op.24 No. 4).

Not only was the musical analysis fascinating and thorough; Henderson contextualised his scholarship with a wealth of literary references to the application of “silvery” sounds and sensations in the aesthetic of the Romantic era. Quotes from the writings of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, W.B. Yeats, Walter de la Mare, Shakespeare, George Meredith and Percy Bysshe Shelley were reminders of that era’s love affair with an ephemeral, ethereal atmosphere and a longing for the unattainable, often in the form of unrequited love. Chopin’s ability to establish a mood was a perfect fit for the artistic ethos of his day.

The tone of Chopin’s preferred piano, Pleyel, was sometimes likened to a glass harmonica. These delicate instruments, together with the delicate overtones of the aeolian harp, were the essence of “silvery” sounds. Henderson concluded this flurry of silver by quoting the lyric of that famous 1612 madrigal by Orlando Gibbons, The silver swan. Although from an era well before the Romantics, it epitomised the shimmer and glitter of Chopin’s “silvery” sound.

References

Henderson, D. (2023). A ‘narrow-keyed’ Pleyel: The ergonomics of Chopin’s interface. Chopin Review, (6), 96-125.

Henderson, D. (2025). ‘Espaces Imaginaires’: Chopin’s Damper Pedal and the Haze of Dreams. In J. Kallberg (Ed.), Romanticism in Music: Poland in its European Context. Warsaw, Poland: Narodowy Instytut Fryderyka Chopina.

Marmontel, A. (1885). Histoire du piano et de ses origines: influence de la facture sur le style des compositeurs et des virtuoses. Heugel.

is a fine

by Rodney Smith.

Effectively chosen slides illustrated Wendy Heiligenberg’s interesting presentation on how string instruments coped with the demands of romantic composers. Furthermore, an introductory performance of Johann Svendsen’s Romance by her pupil violinist Apollon Velonakis accompanied by pianist Jamie Cock admirably summed up the demands being made.

Subsequently, Wendy explained how artists of the romantic period emphasise emotion, passion and nature, and how music of this period evokes stories, places and events She also described how notable composers such as Beethoven (later works), Tchaikovsky, Mendelssohn and Brahms demanded a great deal of dynamic contrast including exaggerated crescendo, diminuendo and sforzando markings and timbral colour.

Wendy illustrated how the violin itself met these demands with the Fingerboard lengthened and angled to allow a wider range of notes, the Bridge raised to increase volume and brightness of tone, the Bass bar widened to improve volume of lower strings and the Strings themselves made of metal or metal-wound gut rather than gut alone.

She also showed how the bow developed from possessing a Swan head (light at the tip) to a Hatchet Head (heavier at the tip) with a slightly concave stick and more hairs.

Such changes enabled virtuosic techniques and long continuous bowing for extended phrases.

Illustrating the importance of humour when dealing with such revolutionary and challenging developments, a recording of part of Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony was played, hilariously performed by the Dolmetsch recorder ensemble and illustrated by comic genius Gerard Hoffnung.

This was a brilliantly light-hearted way to finish and while Tchaikovsky might not have been amused, listeners certainly were.

Providers must be:

● incorporated under the Associations Incorporation Act 1985 (SA) or have some other comparable legal status or

● a registered business* with an active and valid Australian Business Number (ABN)

● based or have a physical presence in South Australia.

*Music providers can operate as an individual/sole trader without a legal business name.

Providers must deliver a recognised sport, active recreation, music or dance activity.

● The nationally agreed definition of sport is ‘a human activity involving physical exertion and skill as the primary focus of the activity, with elements of competition where rules and patterns of behaviour governing the activity exist formally though organisations and is generally recognised as a sport.’

● Active recreation is those engaged in for the purpose of relaxation, health and wellbeing or enjoyment with the primary activity requiring physical exertion, and the primary focus on human activity.

Providers must be child safe compliant.

● A child safe environments compliance statement must be completed through the Department of Human Services and meet all Working with Children Check legal obligations as per the Child Safety (Prohibited Persons) Act 2016.

Providers must offer a minimum activity duration.

● All providers must offer a minimum 8 weeks of semi-structured activity or as approved by the Office for Recreation, Sport and Racing

In addition to the above, music providers must:

● hold a current Certificate of Currency for public liability insurance appropriate to the type and level of eligible activities being delivered.

● hold appropriate skills, experience or qualifications for the activities provided.

Further Eligibility Notes:

● Schools are not eligible to become Sports Voucher providers.

● Organisations may need to supply a copy of the organisation’s constitution or a schedule detailing the minimum 8-week program of activities offered specifically for children.

● Music providers may need to supply evidence of qualifications or experience.

● Organisations may need to supply additional information as requested by ORSR to assist with determining the eligibility of becoming a Sports Voucher provider.

Ineligible activities:

● School-run competitions, concerts, drama programs, including weekend activities or interschoolcompetitions or activities.

● Examination fees for qualifications and assessment.

● One-off events or school holiday clinics which run for less than 8 weeks of activity.

● Purchase of equipment (bats, balls, instruments) except in the circumstances where the equipment is part of the total fees the child must pay to participate in the activity.

Did you know that to comply with the Children and Young People (Safety) Act 2017, all South Australian organisations/sole traders that work with or provide services (including music tuition etc) to children and young people under the age of 18 years must:

● have appropriate child safe environment policy(ies) in place and review them at least once every 5 years

● meet Working with Children Check obligations

● lodge a child safe environments compliance statement with the Department of Human Services

(DHS) and lodge a new statement each time your policy(ies) is reviewed and updated.

Resources to develop a child safe environment policy

The DHS Child Safe Environment Program has provided two different policy templates (see attached). One template is for sole traders with no paid or unpaid workers and the other is for sole traders with workers or for organisations to use. If you choose to use a template, ensure you read it fully and add/delete information where indicated. Alternatively, refer to the Guideline to writing a policy designed to support organisations/sole traders to develop their own child safe policy that will create and maintain environments that are both friendly and safe for children and young people. The Guideline includes information that must be addressed in your policy and provides examples in each section on how you can do this.

Please note that in South Australia, sole traders/ organisations are required to ensure they and any current and potential workers have a current, not prohibited Working with Children Check (WWCC) when working with children and young people. Before employing a person to work or volunteer with children, an employer must verify that the potential worker has a WWCC conducted in the preceding 5 years and is not prohibited from working with children. Employers are legally required to link all WWCCs to their organisation’s registration and to verify a WWCC is valid, online in the DHS Screening Unit portal. Through the verification process, you

should generate a Certificate of Interrogation.

How to lodge a child safe environments compliance statement

Child safe environments compliance statements can be lodged online through the DHS website. After registering, organisations will be prompted to select a service type (please select ‘Music’), include applicant details, answer a range of questions about their practices when working with children and young people, and upload policy document/s as evidence of their answers. Failure to lodge a child safe environments compliance statement exposes an organisation to a $10,000 fine under the Children and Young People (Safety) Act 2017.

If you have questions about child safe environments, contact the DHS Child Safe Environment Program by phone at 1800 371 113 or email dhs.childsafe@ sa.gov.au.

If you have any further questions please do not hesitate to contact us on 1300 714 990 or via email at sportsvouchers@sa.gov.au

Jason Goopy

It is with sadness that I share the news that Honorary Life Member Dr Doreen Bridges AM FACE has passed away in Adelaide. She was 106 years old.

Dee, as she was affectionately known to many, was a champion for Australian music education and leaves an incredible legacy. She was the first to receive a PhD in music education from an Australian university in 1970, and her work continues to impact the lives of teachers and children even today. She will be remembered by many for her publications, including “Music, Young Children, and You,” which introduces parents and educators to music in the early years. With Dr Deanna Hoermann, she published the widely used collection, “Catch a Song,” and evaluated the Developmental Music Programme, which was the beginning of the Australian Kodály movement in New South Wales.

Doreen’s work spans associations and approaches, including the International Society for Music Education, Dalcroze Australia, and Kodály Australia. She was a Patron of Dalcroze Australia and an Honorary Life Member of Kodály Australia. She taught music at all levels, from kindergarten to postgraduate study, including as a Senior Lecturer at the Nursery School Teachers’ College in Sydney. She was later Chairman of the Board of Governors of the NSW State Conservatorium.

ASME offers our condolences to Doreen’s family and all those that were touched by her. Please join me in remembering and celebrating Doreen.

Dr Jason Goopy

President

Australian Society for Music Education president@asme.edu.au

First published on the National News page of the ASME website, 16th September 2024

https://asme.edu.au/vale-dr-doreen-bridges-amface/

[Reprinted with the author’s permission]

Dr Jason Goopy

Acting Higher Degree by Research Coordinator

Lecturer and Coordinator of Secondary & Instrumental Music Education

School of Education | Edith Cowan University

President | Australian Society for Music Education Education Committee Convenor | Kodály Australia

Performers – musicians, actors, dancers – aim to have their talents in top gear for the next stage event. For example: Dame Judi Dench, Hugh Jackman, Paul Macartney, Sting, John Cleese –and many others have one thing in common, they all have studied the Alexander Technique.

Web site https://www.alexander-technique. london/2023/08/01/the-alexander-technique-whycelebrities-love-it has a striking picture gallery of some of the top artists who use the Alexander Technique. Many leading performing arts institutions have Alexander Technique teachers on their staff to help students with the initial stages of their artistic development.

The label, Alexander Technique, is familiar to many people but too often a description of this work is not accurate.

Frederick Matthias Alexander (1869–1955) developed his work here in Australia, majority of his teaching was in England and America from 19041955. People living overseas are more familiar with what this work involves; today there are thousands of Alexander Technique teachers in Europe and America, but very few back here where it all began.

We need more Alexander teachers in Australia.

The Alexander Technique is not just for performers wanting to improve their skills, for all of us it can help improve movement skills in daily life.

Human beings are built for movement. In our daily lives there are basic needs: to walk – so we can get around: to bend – so we can sit down or lower our height to pick something up, or most importantly lower ourselves down on the bed for rest or sleep. We can learn to move with smooth rhythms that demonstrate poise, ease of balance, or movement can be jerky and hard work.

For all musicians who sit to play instruments, the quality of our movement changes from stand to sit and vice versa is important. An interesting experiment is to explore for yourself how much unnecessary tension this action may be causing.

Exploring the change from sit to stand:

Please note Caution, if you normally have difficulties coming to your feet, would advise Do Not try this activity.

When sitting, most body weight is on the sit bones, to stand we transfer our body weight to be on our feet. Simply stand up. How much effort did this transfer require? What changes occurred in the whole-body musculature?

In your first try you may not have noticed much: try again but add the following. Whilst sitting place one hand lightly on the back of your neck to monitor the muscles there, notice the tonus of these muscles. Leave your hand there and stand up. What changes happened to these neck muscles as you stood up? Did the muscles feel softer or tighter during the action? Did the transition from sit to stand happen with a smooth rhythm or at some point was their extra pressure, or a sudden jerk?

Of course, having one hand on the back of the neck to monitor muscle change affects your wholebody balance during this activity, but is useful for gathering information about this movement. You could try placing a hand on the upper leg, under the Chin or the jaw hinge, as you stand, to monitor muscle tone there.

Alexander used mirrors (this was the 1890’s) to observe his manner of ‘Use’ when speaking. You could film yourself using your iPhone doing the sit/ stand action, then on examining the recording look particularly at the head/neck area. What changes took place for the head/neck relationship? If you decide to try an Alexander lesson, talk about what you have learnt.

In an Alexander lesson the hands of the Alexander teacher monitor the constantly changing muscle use of the pupil doing a given activity, as mentioned for example sit to stand.

The training to be an Alexander teacher involves learning to use one’s hands in a specific way, like a feedback loop. The teacher observes the pupil doing an action – sit to stand – then will place the hands on the pupil, it maybe on the back.

Through this touch, this gathering of information about the state of the pupil’s muscles the teacher then monitors muscle tension as the pupil stands and guides the pupil to do the action more smoothy and easily.

One of Alexander’s pupils, the writer Aldous Huxley (1894 – 1963) said, “No Verbal description can do

justice to a technique which involves the changing… of an individual’s sensory experiences”.

This is so true, it is not possible to adequately describe in words an Alexander Technique lesson, it is experiential.

In summarising Alexander’s work the great British physiologist Sir Charles Sherrington, (18571952) wrote “Mr Alexander has done a service to the subject (willed movement and posture) by insistently treating each act as involving the whole integrated individual, the whole psychophysical man. To take a step is an affair, not of this or that limb, solely, but of the total neuromuscular activity of the moment – not least the head and neck.”

In Australia there are few Alexander teachers, unfortunately little teaching in the arts area. While overseas in Europe and America, there are thousands of teachers, many working in wellestablished Arts Institutions such as: Juilliard, Royal College of Music, etc.

The next World Congress for Alexander teachers is being held in Ireland this August, hundreds will be attending.

I am offering Alexander Teacher Training in Adelaide. For further information see my advertisement in this issue of the magazine.

Training to be an Alexander teacher means gaining new skills and knowledge, which can open a new world of rewarding and worthwhile opportunities.

Rosslyn McLeod A.U.A., B.Mus., Dip Ed., A.T.I.

TEACHER TRAINING INFORMATION

• Gain new skills to help artists improve performance.

• Learn to improve: Voice / Breathing

• Ease of movement / Balance / Fine motor control

• Tuition on an individual basis

ROSSLYN McLEOD A.U.A, B.Mus., Dip. Ed

• Experienced Alexander Teacher (40 years)

• Former lecturer the University of Melbourne. V.C.A.

• Gain new skills to assist artists improve performance.

• Learn to Improve Voice and Breathing, Ease of Movement, Balance and Fine Motor Skills

• Personal One-on-One Tuition

• International Qualification upon Graduation

• 40 Years Experience in Teaching the Alexander Technique

Member Alexander Technique International (A.T.I.)

• Former Lecturer at the University of Melbourne and Victorian College of the Arts

• Author of Up from Down Under, the Australian Origins of Frederick Matthias Alexander and the Alexander Technique

• Director and Producer of 70 Min DVD.

• Frederick Matthias Alexander. His Life… His Legacy…

More information, please Contact Rosslyn: Ph: 08 8338 2262 Email: Info@fmalexanderdoc.com

• Author of “Up from Down Under, the Australian Origins of Frederick Matthias Alexander and the Alexander Technique”

• Producer & Director 70 minutes DVD – Frederick Matthias Alexander. His Life… His Legacy.

• Member – Alexander Technique International A.T.I

Correspondence to Contact Rosslyn Ph: 08 8338 2262

Email: info@fmalexanderdoc.com

Rodney Smith.

Dr. Pamela Pike

Continuing a theme from this column in the 2024 Winter Edition of SA Music Teacher, I’m commencing with some comments by Pamela Pike, Editor-in-Chief of Piano Magazine who states (Volume 16, No 4):

Perhaps because we have a healthy amount of teaching music for the piano……it can be overwhelming to introduce lesser-known works into our teaching repertoire.

Later she continues:

Many teachers have discovered that much of the newer or culturally relevant music resonates with their students and engages them…………By creating space in the curriculum for high-quality new or unfamiliar music, students are engaged in robust …study in ways that are personally meaningful……

Let us not forget that European music from the 18th and 19th centuries speaks of a time and context very different to today and the language used reflects social norms of bygone eras. In many ways high quality music written recently by composers from a wide variety of cultures and traditions reaches out to students more immediately.

Pike goes on to mention Connor Chee and eight North American Indigenous composers whose music is noteworthy. There follows information about Weaving Sounds: Elementary Piano Pieces by Native and Indigenous Composers (Piano Education Press 2024).

In this connection I’d like to express my admiration for the presentation by Melody Men and Emma Zhou at MTASA’s recent Professional Learning Day in which they traced the development of western style composing in China during the early 20th century and also the many volumes of recent educational music by Chinese composers that are available. Many of these mesh folk and other idioms from China with more contemporary styles in a way that uses language and gesture that appeals to today’s students.

Including music that is meaningful to our students in an immediate way is surely an important tool for success in our studios as we continue to negotiate the European classics and the romantics as well.

Launched in 2020, Strike A Chord has rapidly become a cornerstone of youth chamber music in Australia, offering students the chance to refine their ensemble skills, connect with like-minded peers, and gain valuable performance experience. Designed to be accessible to all, the competition welcomes culturally diverse and unusual instrumentation and encourages participation from young musicians at all levels.

Unlike traditional competitions that focus solely on top-tier talent, Strike A Chord ensures that every ensemble benefits from expert guidance and constructive feedback. All entrants receive written comments from our judging panel, allowing them to gain insights and improve their skills. Additionally, participants can apply for free coaching opportunities, providing them with tailored advice and the chance to build confidence ahead of their performance.

Any group intending to enter Strike A Chord Foundation or Championship Sections can apply for a private coaching session with a Musica Viva Australia-affiliated artist. The Coaching Program is free and takes place inperson wherever possible. It is a great way to prepare for your Strike A Chord entry by learning some useful tips and tricks from Australia’s leading chamber musicians. With a limited number of sessions each year, priority is given to regional and low ICSEA groups and groups with at least one First Nations-identifying student.

To find out more or apply for a coaching session, visit musicaviva.com.au/coaching-program

Beyond the thrill of competing, Strike A Chord is a celebration of collaboration and community. The competition encourages camaraderie among students, giving them a shared goal to work towards while developing essential teamwork and communication skills. With a range of cash and development prizes available at both Foundation and Championship levels, there are rewards for all participants, from seasoned ensembles to first-time chamber musicians.

Strike A Chord is about discovering the joy of making music together, an experience that lasts far beyond the final performance.

For young musicians seeking direct mentorship from world-class artists, Musica Viva Australia’s Masterclasses offer a unique professional development experience. These bespoke sessions bring internationally acclaimed musicians into the learning space, providing a rare opportunity for early-career artists and students to receive expert guidance.

Masterclasses take place in-person and via livestream across the country, making them accessible to a broad audience of students and teachers. Tailored workshops and mentorship programs allow participants to engage with accomplished performers, gaining insight into

interpretation, technique, and artistic expression. Importantly, these sessions also offer a behindthe-scenes look at life as a professional musician, bridging the gap between aspiring artists and the mainstage.

Our coaching sessions and masterclasses can also provide valuable professional development opportunities for teachers as well as students. Observing expert musicians at work allows educators to gain fresh insights into teaching techniques, broaden their perspectives, and refine their own pedagogical approach. By engaging with these sessions, teachers can enrich their own skills while supporting their students’ growth.

Through Strike A Chord and our Masterclasses, Musica Viva Australia is nurturing the next generation of performers, ensuring that chamber music remains vibrant, inclusive, and inspiring for years to come. Whether you are an aspiring competitor or an eager student looking to learn from the best, our Emerging Artist program provides a pathway to growth, connection, and artistic excellence.

Visit the Musica Viva Australia website musicaviva. com.au/emerging-artists/ to explore our workshops, masterclasses, and competitions, or contact our team to find out how we can help music students realise their full potential.

Some music-related organisations useful for South Australian music teachers

5MBS: MUSIC BROADCASTING SOCIETY OF SA www.5mbs.com 8346 2324

5mbs@5mbs.com

4A River Street Hindmarsh SA 5007

AUSTRALIAN BAND AND ORCHESTRA DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION (ABODA): ABODA SOUTH AUSTRALIA www.abodasa.com.au info@abodasa.com.au

ABODA AS C/-PO Box 327 Walkerville AS 5081

ABRSM EXAMINATIONS www.us.abrms.org/en/home

SA Rep.: Anastasia Chan 8234 5952/0423 282 589

ACCOMPANIST’S GUILD OF SA INC. www.accompanists.org.au

President: Leonie Hempton OAM 8272 8291/0404 145 505 leoniehempton@gmail.com

ADELAIDE BAROQUE www.adelaidebaroque.com.au 8266 7896

0400 716 554 General Enquiries manager@adelaidebaroque.com.au 10 Clarence Avenue, Klemzig SA 5087

ADELAIDE CHAMBER SINGER www.adelaidechambersingers.com/ +61 8 8352 1329 admin@adelaidechambersingers.com

ADELAIDE EISTEDDFOD SOCIETY INC. www.sacoment.com/aes/eisteddfod/ Secretary: Jane Burgess adleisteddfod@adam.com.au jane@janeburgess.com.au

ADELAIDE HARMONY CHOIR www.facebook.com/adelaidephilharmoniachorus/ Secretary: Sherry Proferes adelaideharmonychoir.info@gmail.com

ADELAIDE PHILHARMONIA CHORUS www.philharmonia.net/

ADELAIDE YOUTH ORCHESTRAS www.adyo.com.au/ 8361 8896

Execute Director: Ben Finn claire@adyo.com.au

AMEB EXAMINATIONS: SA AND NT www.sa.ameb.edu.au/ 8313 8088 ameb@adelaide.edu.au

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS OF SINGING (ANATS) ANATS: SA AND NT CHAPTER www.anats.org.au/sant-chapter Secretary: Dianne Spence 0435 300 070 admin@anats.org.au

ANZCA EXAMINATIONS www.anzca.com.au (03) 9434 7640 admin@anzca.com.au

AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY FOR MUSIC EDUCATION (ASME) ASME: SOUTH AUSTRALIA CHAPTER www.asme.edu.au/sa/ President: Luke Gray graylu@trinity.sa.edu.au asme@asme.edu.au

AUSTRALIAN STRINGS ASSOCIATION (AUSTA) AUSTA: SA CHAPTER www.austa.asn.au/chapters/sa President: Fiona Patten fionapattenaista@gmail.com +61 439 885 754

AUSTRALIAN DOUBLE REED SOCIETY www.adrs.org.au

Contact: Josie Hawkes OAM josie.bassoon@gmail.com

AUSTRALIAN STRING QUARTET www.asq.com.au/ 1800 040 444 asq@asq.com.au

BALAKLAVA EISTEDDFOD SOCIETY www.balaklavaeisteddfod.org.au

Contact: Trish Goodgame 0417 891 834 info@balaklavaeisteddfod.org.au

CON BRIO EXAMINATIONS www.conbrioexams.com 9561 3582 / 0401 014 565 lily@conbrioexams.com

ELDER CONSERVATORIUM OF MUSIC www/music.adelaide.edu.au/ 8313 5995 music@adelaide.edu.au

ELDER HALL www.music.adelaide.edu.au/ 8313 5925 concertmanager@adelaide.edu.au

FLUTE SOCIETY OF SA INC. www.flutesocietyofsa.org

Secretary: Catherine Anderson secretary@flutesocietyofsa.org

INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC: DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION

Instrumental Music Office – Klemzig 8261 8988

IM.KlemzigOffice608@schools.sa.edu.au Instrumental Music Office – Morphett Vale 8392 3800

IM.MorphettValeOffice896@schools.a.edu.au Music Programs 8226 1883 education.musicprograms@sa.gov.au

KODALY MUSIC EDUCATION ASSOCIATION OF SA www.kodalysa.com 0405 066 469 kodalysa@gmail.com

MUSICA VIVA www.musicaviva.com.au for concert details Box office: 1800 688 482 contact@musicaviva.com.au boxoffice@musicaviva.com.au

MT GAMBIEREISTEDDFOD www.backstageinc.org.au

Secretary: Maxine Chalinor 0457 067 555 tonymaxine@internode.on.net

MUSICIANS’ UNION OF AUSTRALIA ADELAIDE BRANCH www.musiciansunion.com.au/ 8272 5013 industrial.officer@musicians.asn.au

Federal Treasurer – Sam Moody 0412 933 865 musosa@bigpond.net.au

ORFF SCHULWERK ASSOCIATION OF SA www.osasa.net/ info@osasa.net

PRIMARY SCHOOLS MUSIC FESTIVAL www.festivalofmusic.org.au 8236 7488 info@recitalsaustralia.org.au

ST CECILIA EXAMINATIONS PTY. LTD. www.st-cecilia.com.au 1800 675 292 info@st-cecilia.com.au

SOUTH AUSTRALIA BAND ASSOCIATION www.sabandassociation.org Secretary: David Corkindale secretary@sabandassociation.org

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN MUSIC CAMP ASSOCIATION www.samusiccamp.com.au Administrator: Samantha Taylor admin@samusiccamp.com.au

THE SOCIETY OF RECORDER PLAYERS SA INC. www.facebook.com/recorderplayerssa/ 0410 109 135 srpsainc@gmail.com

TRINITY COLLEGE LONDON EXAMINATIONS www.trinitycollege.com.au 1300 44 77 13: National Mr. Stanley Tudor 8345 3117: Local stanley.tudor@iinet.net.au

UKARIA CULTURAL CENTRE www.ukaria.com 8227 1277 info@ukaria.com