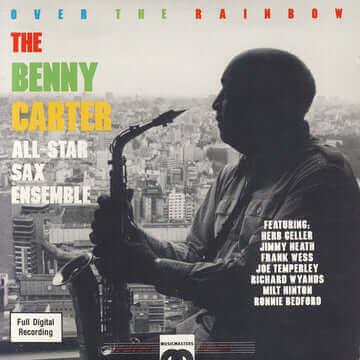

Over the Rainbow

THE BENNY CARTER All-STAR SAX ENSEMBLE

Benny Carter, alto sax

Herb Geller, alto sax

Jimmy Heath, tenor sax

Frank Wess, tenor sax

Joe Temperley, baritone sax

Richard Wyands, piano

Milt Hinton, bass

Ronnie Bedford, drum.

All arrangements by Benny Carter

Carter plays lead on "Over the Rainbow" and "Easy Money."

Geller plays lead on all other tracks, except on "Straight Talk" and "Blues for Lucky Lovers," where the saxes play in unison.

[1] Over the Rainbow

Harold Arlen/E.Y. Harburg

(Leo Feist, Inc.; ASCAP)

[2] Out of Nowhere

Johnny Green/Edward Heyman

(Famous Music Corp.; ASCAP)

[3] Straight Talk

Benny Carter

(Bee Cee Music Co.; ASCAP)

[4] The Gal from Atlanta

Benny Carter

(Bee Cee Music Co.; ASCAP)

[5] The Pawnbroker

Quincy Jones (Pawnbroker Music Corp.; ASCAP)

[6] Easy Money

Benny Carter

(Bee Cee Music Corp.; ASCAP)

[7] Ain't Misbehavin'

Thomas "Fats" Waller

(Mills Music Inc./ Anne Rachel Music Corp.; ASCAP)

[8] Blues for Lucky Lovers

Benny Carter

(Bee Cee Music Co.; ASCAP)

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing any innovator, no matter what the art form, is coming to terms with his past. Some artists studiously avoid any hint of comparison with former glories; others spend a lifetime trying to relive past triumphs. In this album, Benny Carter, whose career in music is unsurpassed in both longevity and accomplishment, reveals his solution to this dilemma. Using a framework he virtually created and certainly perfected -- the saxophone ensemble -- Carter clearly acknowledges his past while making music that is very much of the present. The eight new arrangements heard here show Carter's writing, as well as his playing, to be as inspirational to today's soloists as it was to previous generations of jazz stars.

THE BACKGROUND

Over the Rainbow is the latest in a series of Benny Carter-led saxophone ensemble recordings spanning some fifty years. The inspiration for this project, and several predecessors, is one of the milestones of jazz recording: a 1937 Paris date which launched the French Swing label of Hugues Panassie and Charles Delaunay. On that epic occasion, Carter and his friend, tenor giant Coleman Hawkins, were joined by their French counterparts, Andre Ekyan and Alix

Combelle, along with the legendary gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt. Carter's writing for the sax quartet on Honeysuckle Rose and Crazy Rhythm inspired perfect performances, including some of the greatest Hawkins on record. The other two titles cut that day were more informal but equally satisfying performances on which Carter played trumpet. Happily, on the present album, Carter has included one of them (Out of Nowhere), and based a new melody (The Gal from Atlanta) on the other; after fifty years, we now have the opportunity to hear them fully scored for the sax ensemble.

The saxophone ensemble did not develop in a vacuum, but was inextricably tied to the development of big band jazz in general. Most major jazz orchestras had distinctive reed section sounds, which were a function of both players and arrangers. Many wellknown big band scores emphasized the sax section: Don Redman's Tea for Two (1932), Sy Oliver's Stomp It Off (recorded by Jimmie Lunceford in 1934), Fletcher Henderson's Sometimes I'm Happy (recorded by Benny Goodman in 1935), Duke Ellington's Cottontail and In a Mellotone (1940), Mel Powell's Mission to Moscow (recorded by Goodman in 1942), and two Woody Herman

-- Four Brothers (arranged by Jimmy Giuffre) and Early Autumn (arranged by Ralph Burns), recorded in 1947 and 1948 respectively. Occasionally, an orchestra would record a piece written specifically for the reeds, omitting the brass entirely (e.g. Stan Kenton's 1942 recording of Reed Rapture).

Benny Carter played an essential role in the evolution of what became known as the swing era big band style. Self-taught as an arranger, Carter learned his craft by studying the stock arrangements of the day. In 1926, while with Charlie Johnson's Orchestra at Small's Paradise, he began to bring in his own sketches for the saxophone section. The importance of his innovative scores for Fletcher Henderson's orchestra as early as 1928 and his own orchestras beginning in the early 1930s has been acknowledged by historians and musicians alike. Within the big band context, however, the saxophone section has always remained Carter's special domain. Richly harmonized, flowing saxophone choruses have been the cornerstone of his writing from his very first recorded arrangement for Johnson's band in 1928 (Charleston Is the Best Dance After All), right up to his 1987 collaboration with the American Jazz Orchestra which yielded

the magnificent Central City Sketches suite. Carter's skillful integration of these daring reed excursions within the overall orchestral setting render them all the more effective.

Among the earliest and most influential masterworks by Carter's orchestra were the 1933 recordings Symphony in Riffs and Lonesome Nights. During his European period (1935-38), Carter continued to produce inventive sax choruses, among them Stardust and All of Me (recorded by the Willie Lewis Orchestra with Carter in Paris in 1936) and Skip It (recorded in Holland in 1937 by Carter's international orchestra). Back in the US, Carter formed a new band which yielded such gems as O.K. for Baby and an updated All of Me (both 1940), and Cuddle Up, Huddle Up (1941). In the mid-1940s, Career's California-based orchestra reflected the bebop leanings of many of its younger members, including Miles Davis, J.J. Johnson, and Max Roach. While accommodating these new voices, Carter continued to produce stunning reed tours de force on arrangements like I Can't Escape from You (1944) and Somebody Loves Me (1946). Although he no longer led a regular orchestra after 1946, Carter made the most of recording opportunities using studio orchestras under his own name and

for other leaders and singers. Carter's two albums of arrangements and compositions for Count Basie (Kansas City Suite, from 1960, and The Legend, from 1961), for example, contain many delightful saxophone passages.

All-saxophone groups (as opposed to bigband sax sections) have had an episodic history in jazz. Early ragtime-flavored recordings by such groups as the Six Brown Brothers (1911-20) only hinted at the possibilities of an all-saxophone instrumentation. Far more prescient are some little-known but intriguing 1929 Columbia recordings by a sax quartet led by Merle Johnston. One year after the 1937 Carter/Hawkins epiphany, Carter himself used the same instrumentation (but without Hawkins) to produce an even more ravishing display of reed writing on I'm Coming Virginia. And a few months later, he devised an equally inventive reed chorus on I'm in the Mood for Swing, which was recorded at a Lionel Hampton all-star date in July I 938, Carter's first session after returning from Europe.

Fields. Fields had come to fame with his Rippling Rhythm band, whose formulaic approach involved introducing each number by blowing through a straw into a fishbowl. In 1941, he scrapped that group and formed his New Music, consisting of ten reeds and a rhythm section. This group's output, although largely dance music, includes some interesting jazz-styled arrangements; Fields, in fact, once invited Benny Carter to join the ensemble, presumably as an arranger. There were few other saxophone ensemble experiments in the 1940s, although a Coleman Hawkins-led studio group with Don Byas and Harry Carney recorded some memorable sides for Keynote in 1944. The arranger and alto saxophonist on that session was Tab Smith.

In the early 1940s, one of the most ambitious reed ventures ever came from a rather unlikely source: band leader Shep

Sax ensemble recordings proliferated in the 1950s. Although many were simply all-star jam sessions involving little written material, arrangers Hal McKusick, Lennie Niehaus, Spud Murphy, and Manny Albam, among others, explored a wide variety of reed textures. Two longstanding ensembles were formed, one on each ·coast; the Hollywood Saxophone Ensemble and the New York Saxophone Quartet reflected the prevalent "third-stream" movement. As early as 1949 there were notable spin-off recording groups

from one of the most celebrated sax sections in history: the Four Brothers of Woody Herman's Second Herd who were immortalized in the arrangement of the same name by Jimmy Giuffre. These efforts continued in the 1950s, usually involving some combination of the original group (Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Herbie Steward, and Serge Chaloff) and Al Cohn, who joined Herman a bit later.

Among other saxophone recording projects during this period were Prestige's Four Altos (1957) and Very Saxy (1959) albums, the latter bringing together tenor stars Coleman Hawkins, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, Buddy Tate, and Arnett Cobb. Hawkins also was featured in a 1958 recorded encounter with the Count Basie reed section and on Bob Prince's Saxophones, Incorporated. The 1957 Quincy Jones-supervised Go West Man included three tracks by an alto quartet consisting of Carter and "West Coast" modernists Herb Geller, Art Pepper, and Charlie Mariano; Lennie Niehaus and Jimmy Giuffre provided the arrangements.

Thiele as a retrospective of the 1937 Paris date, reunited Carter with Hawkins and paired them with two leading saxophone voices of a younger generation: Phil Woods and Charlie Rouse. Using the same instrumentation as on the Paris date, Carter prepared eight new arrangements; the result was the monumental Further Definitions. Five years later, Carter recorded a lesscelebrated but highly successful follow-up album, Additions to Further Definitions, using leading West Coast reedmen. In the interim, Carter undertook one other intriguing saxophone group recording project. In 1964, he arranged for and led an ensemble of ten saxophones for Vee-Jay Records. Only one tantalizing track -- Tickle Toe -- was ever issued from that session; the masters have since disappeared.

Sax ensemble experiments in general waned in the 1960s, but it was during that decade that Benny Carter reentered the arena. A 1961 session, intended by producer Bob

In 1972, the formation of Supersax sparked new interest in sax ensembles. Playing Charlie Parker solos harmonized for five saxes, the group spawned other projects, such as Dave Pell's Prez Conference, which based its repertoire on the improvisations of Lester Young. Decades after the Carter/Hawkins Paris meeting, Europe continued to prove fertile ground for sax ensembles. The British group S.O.S. and several Scandinavian efforts sought to

convey many of the prevailing improvisational motifs of free jazz through the medium of the reed ensemble. The World Saxophone Quartet, the most influential of the sax groups to arise in the past decade, has synthesized many of the characteristics of previous movements. Performing without a rhythm section, this group reflects a wide range of influences, melding some of jazz's earliest forms of collective improvisation with rhythm and blues and free jazz.

Carter himself has recorded twice in recent years in a sax ensemble setting. In 1982, he was joined by Swedish alto star Arne Domnerus and Americans Plas Johnson and Jerome Richardson for several tracks on his Skyline Drive album, and in early 1988 he was featured with the French group Saxomania, led by Claude Tissendier, on a Paris recording. The advent of several contemporary saxophone groups, including the Rova and 29th Street Saxophone Quartets, and Odean Pope's Saxophone Choir, attests to the validity of the concept pioneered by Benny Carter some fifty years ago.

THE ARTISTS

Joining Benny Carter is a hand-picked group

brought together from such diverse locations as Germany and Wyoming specifically for this project. Not only is each of the saxophonists an accomplished improvisor with a distinct sound, but also an adept reader, with the ability to blend in a section. Each player, moreover, approached the project with extraordinary enthusiasm and dedication. The writing is Carter's, but the sympathetic interpretation derives from the cooperative efforts and eager suggestions of eight talented musicians who obviously considered the session more than "just another gig."

HERB GELLER (alto sax). This album marks the welcome return to the US recording scene of a leading alto talent. Born in Los Angeles in 1928, Geller began his career in some of the big bands of the late 1940s and early 1950s. He soon earned a reputation as one of the luminaries of the West Coast jazz scene, playing in a classic Charlie Parkerinfluenced style. In the late 1950s, Geller worked with Benny Goodman and Louie Bellson before moving to Europe in 1962. He has spent the last 25 years in Germany, first as a member of the Radio Free Berlin (SFB) orchestra and, since 1965, with the North German Radio Orchestra (NOR) in Hamburg .Active as an educator, Geller has completed

an improvisational method book. He continues to perform frequently at major European festivals and is currently working on a musical with a jazz theme. A powerful soloist and indefatigable lead player, Geller returned to the US especially for this date, calling the trip "the greatest vacation I ever had!"

JIMMY HEATH (tenor sax). A member of a most illustrious jazz family (his brothers are bassist Percy and drummer Albert), Heath was born in Philadelphia in 1926. He first came to prominence on alto sax, earning the nickname "Little Bird" because of his thorough assimilation of Charlie Parker's innovations. Heath led his own big band in Philadelphia in the late 1940s. This unit was influential in the careers of members like John Coltrane, who credits Heath with fostering his musical development. Heath has since worked with virtually every major bebop figure, including Howard McGhee, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Art Farmer. Although best known for his tenor, Heath is also a superb flutist and soprano saxophonist, as well as an arranger and composer whose works have been performed by many leading ensembles. In 1975, he joined his siblings in the highly successful Heath Brothers group. One of the

leaders in the jazz education movement, Heath has shared his knowledge through extensive work with Jazzmobile and currently teaches at Queens College. His solo style is a fascinating amalgam of modern concepts, nurtured by a deep understanding of earlier traditions, including the contributions of Benny Carter. "I heard Benny when I was fourteen and got my first alto. My father had his record of Cocktails for Two. I always loved his sound and articulation; his improvisations are like the work of a great composer." Heath adds, "to be asked to record with one of my heroes is a dream come true."

FRANK WESS (tenor sax). Born in Kansas City in 1922, Wess is one of jazz's most versatile reedmen, as well as an important arranger and composer. His early associations include the orchestras of Billy Eckstine, Eddie Heywood, Lucky Millinder, and Bullmoose Jackson in the late 1940s. In 1953, he joined Count Basie, quickly becoming a mainstay of the Basie powerhouse, as both an instrumentalist and an arranger. Wess added flute to his arsenal, and is credited with introducing that instrument to the modern jazz idiom. After leaving the Basie organization in 1964, Wess turned to free-lance work and has since

been in constant demand in the studios. In the mid-1970s, he played regularly with the New York Jazz Quartet, which he helped found, and in the 1980s with such repertory groups as Dameronia and the American Jazz Orchestra. In 1981, Wess toured Japan as a member of the Benny Carter All Stars. At home in virtually any musical setting, Wess is capable of evoking a wide variety of moods from his tenor -- from big-toned and hard-swinging to fleet and boppish.

JOE TEMPERLEY (baritone sax). Since moving to New York from his native Scotland, Temperley has established himself as one of jazz's premier baritone saxophonists. He was born in Fife in 1929, and gained big band experience in several British dance bands. He then spent seven years with trumpeter Humphrey Lyttelton before moving to the US in 1965. His impressive big band credentials include Woody Herman, Thad Jones/Mel Lewis, and Buddy Rich. In 1974, he replaced Harry Carney (a close friend and major influence) in Mercer Ellington's orchestra. Well-versed in Ellingtonia, Temperley played in the orchestra for the Broadway show

Sophisticated Ladies, and his many studio credits include the sound track of the film Cotton Club. In recent years, he has worked in Buck Clayton's big band. This is Carter. "I

could always recognize Benny's writing, as well as his playing; I've been a fan for years," he says. Commenting on the opportunity to play with the man whose work he has admired for so long from afar, Temperley adds: "This is the most inspiring thing I've ever taken part in. I'd go to the moon for Benny!" Temperley's baritone style combines the full-bodied tone necessary to anchor a section with a flexible and swinging solo style. He also demonstrates a thoughtful approach to improvisation, and at slower tempos displays a delicacy not usually associated with his instrument.

RICHARD WYANDS (piano). Wyands began his professional career in his native Oakland, California, where he was born in 1928. He served as accompanist for vocal greats Ella Fitzgerald and Carmen McRae in the mid1950s, before moving to New York in 1958. He has been in great demand ever since, working and recording with an impressive array of jazz stars of varied styles, including Charles Mingus, Cal Tjader, Gigi Gryce, Roy Haynes, Zoot Sims, Gene Ammons, and Oliver Nelson. He was a regular member of guitarist Kenny Burrell's groups for many years, as well as of the JPJ Quartet in the mid-1970s, and currently plays with Illinois Jacquet's big band. During the past two years, Wyands has worked regularly with

Benny Carter, particularly during Carter's frequent New York engagements at Carlos I. His sensitivity as an accompanist (note his imaginative fills) and swinging, cliche-free solo style are well-displayed throughout this album.

RONNIE BEDFORD

(drums). Universally respected by his peers, Bedford has worked with many of the greatest names in jazz in a wide range of musical contexts. Born in 1931 in Bridgeport, Connecticut, Bedford studied with local teachers, as well as with Fred Albright of the NBC Symphony. In 1951, he

MILT HINTON (bass). Hinton not only helped carve a role for his instrument in jazz, but continues to be a creative force in his seventh decade as a professional musician. Born in Mississippi in 1910, Hinton spent his formative years in Chicago, where he experienced firsthand the musical cataclysm brought about by giants like Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines. While still in his teens, Hinton attracted the attention of several bandleaders in Chicago, and made his first recording in 1929 with Tiny Parham. He worked with violin virtuoso Eddie South in the early 1930s and joined Cab Calloway's orchestra in 1936, remaining until 1951. Gaining his initial entree through Jackie Gleason's mood music records, Hinton became one of New York's most soughtafter studio players. Perhaps the mostrecorded jazzman of all time, Hinton's backing has enhanced countless vocals, television productions, commercial jingles, and dramatic' scores, as well as every conceivable type of jazz recording: from Eubie Blake to Bill Evans, Benny Goodman to John Coltrane. As if his musical achievements were not enough, Hinton is also an accomplished photographer and diligent chronicler of the music he helped create; his book of photographs and reminiscences, Bass Line, was published in 1988 by Temple University Press to universal acclaim. Hinton and Carter have a longstanding friendship. The bassist remembers some arrangements that Cab Calloway commissioned from Carter. "The band never got tired of playing them," he recalls. Their first recording together took place almost fifty years ago, on one of the classic Teddy Wilson dates featuring Billie Holiday. Hinton was also the bassist on one of the greatest saxophone summits ever: the 1939 Lionel Hampton session which brought together Carter, Coleman Hawkins, Chu Berry, and Ben Webster. Fifty years later, the hallmarks of Hinton's style remain intact: the huge sound, flawless intonation, imaginative lines, steady time, and, last but not least, sense of humor.

went on the road with Louis Prima, with whom he made his first recording. After a two-year stint as a snare drummer in the 2nd Army Bagpipe band, Bedford was able to perfect his big band skills with the orchestra of Billy May. In the 1960s, Bedford broadened his already considerable musical experience. In addition to studio work, he performed regularly in such diverse jazz company as Eddie Condon's group and challenging ensembles led by Rod Levitt and Johnny Richards. Bedford also enhanced the acts of countless popular singers and several leading comedians, including Woody Allen, Rodney Dangerfield, and Bob Hope. By the 1970s, Bedford was concentrating on jazz; his associations during that decade included two years with Benny Goodman. Benny Carter first worked with the drummer in 1977 when Bedford was a last-minute replacement during Carter's engagement at Michael's Pub. Bedford became Carter's drummer of choice in New York, joining the saxophonist for many other club and concert performances. In 1986, Bedford tired of the New York scene and moved to Wyoming, where he enjoys ranching as well as playing and teaching. It is clear from his work here why Carter requested him: Bedford is a highly musical drummer, whose sensitive support buoys both ensemble and soloists.

THE MUSIC

Carter's unusual uptempo treatment of Over the Rainbow works perfectly. The Harold Arlen melody takes on a new sheen in Carter's hands, while retaining its own compelling contours. The ensemble is heard in the opening and closing choruses, richly scored in quintessential Carter fashion. In between are half-chorus solos by Heath, Geller, Temperley, and Wess, a full-chorus by Carter, a half by Wyands, and half shared by Hinton and Bedford.

Out of Nowhere opens with improvised statements from Carter, Wess, Geller, Heath, Temperley, and Wyands. Each soloist demonstrates his ability to make a cogent (and complementary) statement in only sixteen measures. The sax ensemble takes over for the final chorus, which is filled with lovely harmonic combinations and melodic embellishments.

Straight Talk is a new Carter piece in the time-honored twelve-bar blues tradition. The composer adds variety by assigning the opening chorus to the tenors, adding the altos and baritone for the second. Hinton skillfully fills the spaces. The solos (two choruses each) are by Wess, Carter, Heath, Wyands, Temperley, and Geller.

The Gal from Atlanta opens with a sax ensemble paraphrase of a standard melody, launching two-chorus solos by Wess, Carter, Temperley, Geller, and Wyands. The ensemble returns for a completely different and exciting out-chorus. The entire performance is propelled by Bedford's accents and Hinton's relentless drive.

The Pawnbroker is a Quincy Jones composition and the theme of the 1965 film of the same name. The lovely melody serves as a vehicle for the sax ensemble and for pianist Wyands, who is the only soloist. Carter's voicings take full advantage of the section, with imaginative combinations and juxtapositions. The use of the baritone is particularly striking, as Temperley's deep tone is set off dramatically against the other reeds in several places. The opening and closing ensemble choruses differ subtly: the last eight bars of melody in the first chorus are played by the piano, whereas in the outchorus the lead alto carries the melody over a contrapuntal rhythmic figure played by the baritone.

which featured Carter's arrangements and compositions. Carter has recorded it several times with different instrumentations, most recently with the American Jazz Orchestra on Central City Sketches (CIJD 60126X). The ensemble states the jaunty melody in the first chorus, with Carter taking the bridge. A series of inspired solos follows; Geller, Wess, Temperley, and Heath take two choruses each, followed by Carter for three and Wyands for two. The saxes return with some catchy riffs, leaving space for perfect fills by Wyands and Hinton.

Easy Money is a perennial Carter favorite that seems to lend itself to any setting. The piece was premiered by the Count Basie orchestra on The Legend, a 1961 album

Carter recorded Fats Waller's Ain't Misbehavin' only once before; in 1943, he accompanied the composer on trumpet on the superb rendition heard in the film Stormy Weather. The sumptuous opening ensemble treats the melody with great respect. The saxes ease into a supporting role on the bridge, behind Temperley's majestic baritone. Temperley finishes the chorus and is followed by choruses from Heath, Geller, Wess, Carter, and Hinton. Each builds on what has preceded him, and everyone keeps Waller's theme in sight. The ensemble returns for a daring out-chorus highlighted by some intricate sixteenth-note passages, featuring Wyands' piano on the bridge. Blues for Lucky Lovers is an uptempo Carter

which he first recorded in Sweden in 1985 with Nat Adderley and Red Norvo. Two choruses by the rhythm section bring on the theme, stated by the ensemble. Each saxophonist solos for three choruses: Temperley, Geller, Heath, Carter, Wess. That order is maintained for the four-bar trades with Bedford which follow. Hinton gives a three-chorus lesson in walking bass, with delicate punctuations by Wyands, before the saxes return.

This album reaffirms Benny Carter's mastery of the idiom he helped create half a century ago. In music, as in life, Carter draws on his past, but refuses to dwell on it. As he says, "My 'good old days' are here and now."

Ed Berger, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

Produced by Ed Berger

Engineering: Gregory K. Squires, Paul Goodman

Recorded October 18 and 19, 1988 at RCA Studios, New York

Jimmy Heath appears courtesy Land Mark Records

Photo of Benny Carter by Ed Berger

Cover Design: John Berg