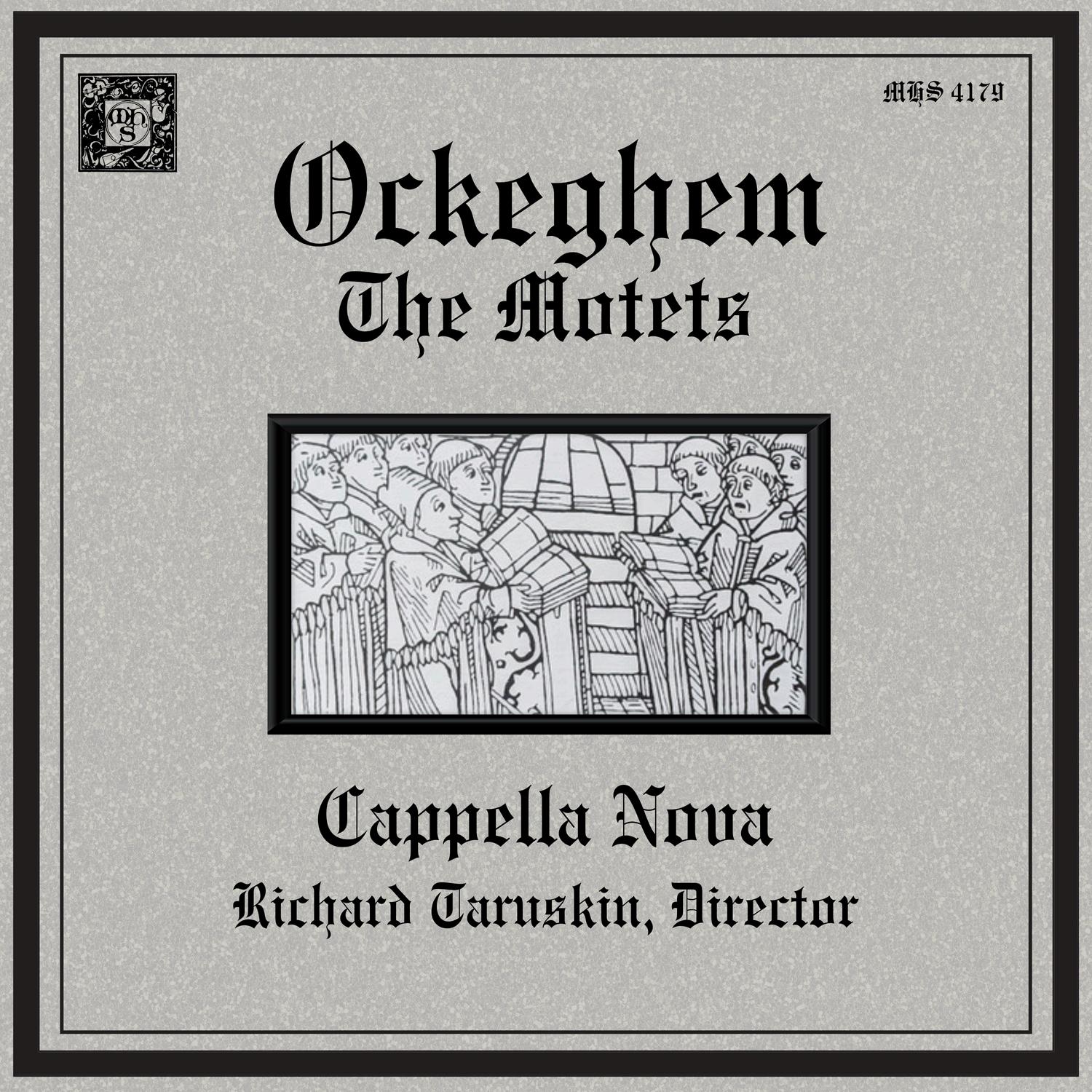

Johannes Ockeghem: Motets

1 BUSNOIS: In Hydraulis 06:34

2. Alma Redemptoris Mater 05:33

3. Intemerata Dei mater 07:42

4. Salve Regina (manuscript Cappella Sistena 42) 08:41

5. Salve Regina II (manuscript Cappella Sistina 46) 04:38

6. Ave Maria 03:29

7. Celeste beneficium (doubtful attribution to Ockeghem) 09:45

8. Gaude Maria (doubtful attribution to Ockeghem) 09:53

Ockeghem

The Motets

D

uring the 15th century, the genre of musical

composition known as motet underwent such a

thorough transformation that it would be virtualy

impossible to define the word in terms that applied

equally well to works so named written at the begin

ning of the period and at the end. Around 1400, the

motet, always the epitome of learned music, had

become a sort of musi cal monument. It was

conceived in purely architectonic terms: over the

foundation of a borrowed Gregorian chant cast as

it were in musical stone by a process of elaborate

rhyth mic patterning known then as “talea” and now

as “isorhythm, ” melodic lines-each carrying its own

text and hang intelligibility! Were vaulted and

buttressed in great sonic arches. In their extreme

complexity of design and rigidity of structure,

motets of this type gave expression to the final,

most impressive outburst of late medieval cosmic

speculation in tone: the apotheosis of the Platonic

ideal of music as the divinely ordained symbol of

the harmony of the spheres. Isorhythmic motets

celebrated great occasions, praised great cities, and honored great men of church and state. The last major practitioner of this somewhat archaic genre was Guillaume Dufay (d. 1474), who wrote, among others, three impressively grandiose specimens to commemorate events in the career of Pope Eugenius IV (reigned 1431-40).

By the middle of the century, elaborately constructivist techniques had largely passed over into the domain of the cyclic Mass, and the motet was reborn (the English, whose music was

luxuriantly in votive services And were surely known to all believers by heart.

Johannes Ockeghem (d 1497), Dufay’s Successor

as leading composer of Catholic church music in

the late 15th century, was heir to all these

traditions and developments, both musical and liturgical. This recording presents his entire extant legacy of motets (undoubtedly only a fraction of what he must have composed during his halfcentury career) with the exception of some

fragments and a mysterious composition entitled

Ut heremita solus (“Lonely as a Hermit"), which

Comes down to us shorn of its text. All but one of the seven motets are Marian (and even the

remaining work Celeste benei cium, is probably only an apparent exception, as will be explained. In their style and fac- ture, Ockeghem’s motets

adhere to the line established by Dufay’s Ave

Regina, while at the same time proclaiming their

Composer’s individuality in matters of texture and sonority: three of the motets are scored for five

Voice parts rather than the standard complement of four, and several exploit extreme tessituras. One in particular, Intemerata, is a prime example of the exploration of the low est depths of vocal range for which Ockeghem-known in his day as a bass singer as well as composer-was famed Many of Ockeghem's motets are found in choirbooks associated with the Papal chapel choir in Rome, testifying to his prestige as churchman and composer alike, as he him self never sang there.

And all of them display the effortless perfection of

form and rapt spirituality through whose magical combination, in the words of Desiderius Erasmus,

"the golden voice of Ockeghem caressed the ears of the angels, and swayed the hearts of men to their depths."

-Richard Taruskin

TEXTS AND NOTES ON THE WORKS

1 In praise of Ockeghem: In Hydraulis

(words and music by Antoine Busnois)

Source: Trent, Castello del Buon Consiglio, Ms. 91, f. 35-37 (music) Munich, Bayerische

Staatsbibliothek, Mus. Ms. 3154, f. 27-29 (text)

In hydraulis quondam Pythagora/ Admirante melos, phtongitates/Malleorum. Secutus aequora/Per

ponderum inaegquili tates/Advenit musae

qualitates./Epitritum ac emioliam,/Epogdoi duplam

perducunt./Nam tessaron pente

convenientiam/Nec non phtongum et pason

adducunt,/Monocordi dum genus conducunt.

Once Pythagoras, having wondered at the melodies

of water organs, and having attend ed to the pitches

made by hammers, discovered the ratio-properties

of the muse through the inequalities of weights.

These ratios are the epitritum (4:3), the emiolia

(3:2), the epogdoon (9:8) and the double proportion

(2:1). These produce the harmony of fourth, fifth,

tone and octave, while monochords complete the scale.

Haec Ockeghem, qui cunctis ecinis/Galliarum in regis aula,/Practicum propaginis/Arma cernens

quondam Jagora/Burgundiae ducis in patria,/Pro

Busnois, illustris comitis/De Chaulois indignum

musicum,/Saluteris tuis pro meritis/Tamquam

summum capias tro pheum,/Vale, verum instar

Orpheicem!

You, Ockeghem, who have understood the late

Pythagoras and are first among singers at the court

of the King of France, strengthen the practice of your progeny in the nation of the Duke of Burgundy.

On behalf of me. Busnois, unworthy musician of the

illustrious Count of Charolais, be saluted for your great merit, and may you take the highest trophy.

Flourish, true image of Orpheus!

Text emended and translated by Susan Hellauer

As a kind of preface to our program of Ockeghem

motets we present this tribute to the master—itself in the form of a motet- from his greatest colleague,

Antoine Busnois (d. 1492), who was to the court and chapel of the Duchy of Burgundy what

Ockeghem was to those of France: “first singer”

(i.e., chiet musician and composer), as the text of the motet puts it. Ockeghem is compared with

Pythagoras, the legendary inventor of musi cal science, and with Orpheus, the semi godly musician who could move the shades of Hades with

his songvivid testimonials To Ockeghem’s preeminence in the eyes of contemporaries. Since

Busnois refers to his patron as the Count of

Charolais The motet must have been written

before Charles the Bold acceded to the ducal

throne in 1467. And since dedicatory motets like

this one probably arose from direct professional

contact. It has been suggested that In hydraulis

was composed in connection with the coronation

of Louis XI of France in 1461, when the whole

Burgundian court and its entourage visited Paris.

Since In hydraulis is a celebratory motet with a

“great man” as its object, and especially since its

text deals so conspicuously with musical “science, ”

it is not surprising that Busnois reverted in it

somewhat to the style and procedures of the old-

fashioned isorhythmic motet. The whole piece is

laid out over a series of repetitions in the tenor part

of a three-note pattern which, in its transposition,

sums up the “Pythagorean” pitch ratios the text

describes Moreover, the three-note motive is put

through a series of rhythmic alterations that

express the same ratios in terms of durations.

Meanwhile the three other voices carol away in the

most complex fashion-syncopations, lengthy melodic sequences, cross rhythms and accents

galore And so, despite the ostensibly hon oritic

purpose and the ostentatiously humble tone of the

motet’s text, one imagines that the real purpose of

the piece may well have been to astound the

assembled musicians of the French court with

Burgundian virtuosity. (Ockeghem seems to have

returned the “compliment” with the even more

spectacularly complex Ut heremita solus, which,

for carious reasons too lengthy to go into here,

might be a sort of companion piece to in hydraulis

with Busnois as its dedicatee).

Alma Redemptoris Mater

Source: Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms.

Cappella Sistina 46, f. 115-17

Alma redemptoris mater/quae pervia caeli porta

manes,/et stella maris, succure cadeno ti/surgere

qui curat populo:/Tu quae genuistio natura

mirante,/tuum sanctum Genitorem

Mother beloved of the Savior, and Gate wide open of Heaven, Star of the Sea, bring help to the people

that weakens and wavers; O thou, whom marveling

Nature saw to bear the Creator within thee:

Virgo prius ac posterius, /Gabrielis ab ore sumens illud Ave,/peccatorum miserere Amen.

Virgin before and since, O thou to whom Gabriel kneeling, uttered his "Hail” , show pity to all sinners. Amen.

Tradition holds that the original chant melody of this Marian antiphon was composed in the eleventh century by the monk and musical theorist

Hermannus Contractus Abbot of Reichenau in

Switzerland (1013-54). In Ockeghem's setting, the melody is transposed up a fifth, liberally embellished in the manner of the cantilena, and assigned to the alto voice rather than the more conventional tenor. The unusually high range thus achieved combines with an exceptional transparency of texture and fluid lyricism in the vocal writing to evoke a delicate musical trait of the

Divine Mother

Intemerata Dei Mater

Source: Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms.

Chigiana C. VIll. 234, f. 276' -79.

Intemerata dei mater, generosa puella,/Milia

carminibus quam stipant agmina divum,/Respice

nos tantum, si quid jubilando menemur./Tu scis,

virgo decens, quantum discrimen agatur/Exilibus,

passimque quibus jactemur arenis.

O undefiled mother of God, gracious maiden, whom

flights of angels throng with a thou sand songs:

look down on us, if we deserve any reward for our

celebrations. You, noble virgin, know in what danger we exiles are, And in what wastes of sand we are tossed about.

Nec sine te manet ulla quies, spes nulla laboris, /Nulla salus patriae, domus aut potiunda

parentis,/Cui regina praees, dispen sans omnia./Laeto suscipis pios dulci quos nectare

potas,/Et facis assiduos epulis accumbere sacris.

Without you there is no rest, no hope in Our travail,

no salvation for our country, no regaining that ancestral home over which you reign and to which

you give all things. But you raise up the devout with

a cheering face and give them sweet nectar and

invite them to recline at sacred banquets

forevermore.

Aspiciat facito miseros pietatis ocello Filius;/ipsa

potes. Fessos hinc arripe surSum/Diva, virgo, manu

tutos et in arce locato. Amen.

Prevail upon your son to look upon the wretched

with an eye of pity (for we know you can), and, O

Virgin, lift up the weary in your heavenly hand, take

them away from this place, and set them safely in

the citadel. Amen.

Trans Lawrence Rosenwald

No greater contrast could be imagined than between the airy grace of Alma Redemptoris Mater and the tortured depths of Intemerata. This motet

is a prime example of a votive antiphon--a newly composed, non-canonical text meant for a similarly non canonical votive Mass or Office, so common ly

celebrated in the fifteenth century. In keep ing with

the nature of the text, the music seems to be based on no preexistent cantus firmus. It is an excellent example of Ockeghem's “free style, " in which the

music derives its shape from a series of sections

based on a line or two of text, each of which, beginning slowly, reaches a bristling climax of

rhythmic energy before subsiding into the cadence

Although there is no cantus firmus, the motet

quotes from two Masses by Ockeghem which share

its extremely somber range and rich texture: the

Missa M-Mi (quoted at the very beginning) and the

Missa Fors seulement (quoted at the beginning of the motet's secunda pars at the words, "Nec sine

te"). Fors seulement itself was a famous song of courtly love (also by Ockeghem). Quotations from

such songs in the context of Marian devotions was

a favorite way of sym bolizing the love felt by the

Christian soul for the Bride of Christ. Both masses

quoted in Intemerata are found along with it in the

famous “Chigi Codex” now at the Vatican This

fabulously illuminated Flemish manu script,

seemingly compiled as a retrospective shortly after

Ockeghem’s death, is the richest single source of

his music today.

Salve Regina

Source: Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms.

Cappella Sistina 42, f. 144-48.

Salve regina, mater misericordiae: Vita, dulcedo et

spes nostra, salve. Ad te clama mus, exsules, filii

Hevae. Ad te suspiramus, gementes et flentes in

hac lacrimarum valle.

Hail, holy Queen, Mother of mercy; Hail, Our life,

our sweetness, and our hope! To thee do we cry,

poor banished children of Eve, to thee do we send

up our sighs, mourning and weeping in this vale of tears.

Eya ergo, advocata nostra, illos tuos mis ericordes

oculos ad nos converte. Et Jesum, benedictum

fructum ventris tui, nobis post hoc exslium ostende.

Turn then, most gracious advocate, thine eyes of mercy towards us; and after this Our exile, show

unto us the blessed fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

O clemens: O pia: O dulcis Virgo Maria.

O clement, O loving, O sweet Virgin Mary!

The Salve Regina is the most penitential in mood of

the four Marian antiphons, and so became the most

popular for votive obser vances. Ockeghem wrote

two motet settings which paraphrase this famous

chant, and they could not be more different. The

one we present first emphasizes the penitent mood

by rather unconventionally placing the chant

paraphrase in the lowest voice part, with

Occasional migrations to the more usual tenor. The beautiful arc-like settings of the closing

acclamations are unforgettable.

Salve Regina

Source: Rome, Bibliote ca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms.

Cappella Sistina 46, f. 118-20.

The other setting of Salve Regina is an intriguing

experiment in texture. The tradition al melody is

paraphrased cantilena-style in the highest voice

part, and the composer has taken pains to make

the setting particularly song-like. The repetition of

the opening phrase in the original chant melody is

mir rored by a corresponding exact repetition in the

paraphrase, at the words “Vita, dulcedo. At the

same time, however, the tenor enters with

sustained notes (and continues in this fashion to the end), creating a texture remi niscent of the

older cantus firmus motet, and perhaps deliberately

creating the illusion that the tenor, not the soprano,

is the voice carry ing the preexistent melody. No

such tune has yet been identified in the tenor part,

however, and while it is not impossible that we are

dealing here with a double paraphrase (wherein

lines derived from two different Gregorian chants

are played off one against the other), it is more

likely that the composer has perpetrated a clever

and in fact unique trompe-l’oreille effect. It has

recently been discovered that this setting of the

Salve Regina was published in 1520 by the printer

Andrea Antico of Rome with an attribution not to

Ockeghem but to the somewhat younger composer

Philippe Basiron. Thus an element of doubt has

been raised as to the motet’s status as a

composition by Ockeghem Considering, however,

that the manuscript from which we have drawn our

version of the motet also contains other works by

Ockeghem which are of unchallenged authenticity, we feel justified in relying for our present purposes

on the standard attribution.

Ave Maria

Source: Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms.

Chigiana C VIl 234, f 139’ 40

Ave, Maria, gratia plena: Dominus tecum. Benedicta

tu in mulieribus, et benedictum fructus ventris tui,

Jesus Christus. Amen.

Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee.

Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the

fruit of thy womb, Jesus Christ.

Amen.

Ockeghem’s concise setting of what is surely the

most familiar of all Marian votive texts is an

exquisite jewel of a motet in free style. No

preexistent melody is present: rather. All four

voices move in a rhythmically close-knit harmony,

achieving a marvelous climax at mention of the name of Jesus by means of a sudden expansion of range (both outer voices mnove to their extremes) and a lengthening of rhyth mic values The concluding “Phrygian” cadence to A is one of Ockeghem’s most beautiful inspirations.

Celeste beneficium

Source: Regensburg, Proske-Bibliothek, Mus. Mss.

B 211-15

Celeste beneficium introivit in orbem ver bum Dei quod fulget nobis per Germaniam.

A heavenly gift has come into the world: it is the word of God, which shines out for our Germany.

Celeste beneficium accipe Germaniam grata quia

tibi resonuit vox tandem aeterni numinis salutem

adesse nuncians. Ambulate dum lucem habetis.

And you, O Germany, accept freely that heavenly

gift; for at long last the voice of the everlasting God has sounded out to you, pro claiming that salvation is at hand. Go forth now, while you still have the light.

-Trans Lawrence Rosenwald

The authenticity of this motet as a work of Ockeghem’s has been doubted by many It is found

only in a set of German partbooks dated 1538, which puts its unique Source at an enormous remove from Ockeghem both in time and in place

The only direct evidence that links the work with

our composer seems flimsy; the entry “Okegus” in

one part (the bassus) out of five. And the piece is

different from that of any authenticated work of the

master in style and technique, since it makes so

much conspicuous use of imitation. And yet, there

is no reason to dismiss the possi bility that the work

is authentic: if it does not immediately remind us of Ockeghem’s style, neither does it bring that of any

other com poser to mind The imitative writing, though pervasive, is not “structural” as it might be

expected to be in a work actually composed

around 1538 The main structural principal is still

the sustained-note cantus firmus in the tenor part,

around which the other parts twist like vines, the

close imitations assuming an essentially decorative

role. And we simply do not possess enough of Ockeghem’s music to be able to form a reliable

“internal” basis for deciding questions of

authenticity. In other words, the internal grounds

for doubting Ockeghem’s authorship are not strong

enough to outweigh even the flimsiest external

grounds for accepting it, and so accept it we must,

at least for now. Not that one is reluctant: Celeste

beneficium is clearly a major work by a great

master.

Mysteries do not stop with matters of authorship

The text is clearly a “contrafact, ” that is, a

substitution for a lost original. Not only would

Ockeghem have had no call to write a motet about

or for Germany, and not only is it obvious that the

text Is much shorter than the one to which the music was original ly composed (just listen to the

amount of fragmentary word repetition—all

faithfully transcribed from the source-that is

required to stretch the words out over the musical

frame), but there are specifically musical and

liturgical reasons for suspecting a substitu tion.

The repetition of a lengthy passage of music from

the first part of the motet near the end of the second part (compare the settings of the words

”fulget nobis” and “salutem adesse nuncians”)

suggests the form of a Gregorian responsory, and in fact there is responsary whose text begins with

the words “celeste beneficium introivit” … and it is

Marian! It is part of the liturgy of the Nativity of the

Virgin Mary, and it was undoubtedly the text to which this music was originally composed, whether

or not by Ockeghem

Gaude Maria

Source: Regensburg, Proske-Bibliothek, Mus Mss B 211-215.

Gaude Maria virgo, cunctas haereses sola interemisti,/Quae Gabrielis archangeli dictis credisti,/Dum virgo deum et hominem genuisti,/Et post partum virgo inviolata per mansisti.

Rejoice, Virgin Mary: you unaided have put down all heresies. You believed the word of the Archangel

Gabriel. You, a virgin, gave birth to God and man, And remained a virgin, unspotted, after giving birth.

Gabrielem archangelum credimus divinitus te esse affatum. We believe that the Archangel Gabriel spoke to you by divine dispensation. Uterum tuum

de spiritu sancto credimus impregnatum.

We believe that your womb was made pregnant by

the Holy Spirit.

Erubescat Judeus infelix, qui dicit Christum de

Joseph semine esse natum./Dum virgo deum et

hominem genuisti,/Et post partum virgo inviolata

per mansisti.

Blush for shame, miserable Jew, who say that

Christ was born of Joseph’s seed. You, Mary, a

virgin, gave birth to God and man, And rermained a

virgin, unspotted, after giving birth.

-Trans. Lawrence Rosenwald

Gaude Maria comes from the same set of partbooks as Celeste beneficium, is very sim ilar to

it in style, is attributed to Ockeghem on the basis of

the same evidence (though “Okegus” appears this

time in all five part books), and its authenticity,

therefore, has been similarly doubted. This time, at

least, we can be sure the text is the original one, namely, the Great Responsory for the Feast of the

Annunciation. The form is respected in both text

and music, with partial repetitions of the first

section in both the third and the fourth sections of

the motet. This masterly setting teems with musical

wonders, but we will content ourselves here with

describing only one, a remarkable bit of musical

symbol- ism. The motet is in the transposed Lydian

mode on C, but the note G is curiously insisted

upon at all the section cadences, and is sustained

through practically the whole of the second part It

is undoubtedly meant to stand for the Archangel

Gabriel and his “Ave” on hearing which Mary conceived the Son of God.

Cappella Nova

Ruth Cunningham, * Wendy Erslev, Sarah Hamby, Imogen

Howe, Christine Hunter, Jessie Ann Owens, Caroline Rockwood - sopranos

Peter Becker, Susan Hellauer, * Marian Hyun, Patricia

Petersen, Hugh Robertson, altos

Peter Bannon, Robert Eisenstein, Edward Stevenson, tenors

Thomas Baker, Richard Bodig, Paul de Simone, Louis Flaim, Robert Myers, basses

Richard Taruskin, director

*1st 4 tracks only.

Special thanks to: David Macbride for assisting at the May

1979 recording sessions; Prof. Leeman L. Perkins for assistance in procuring sources.