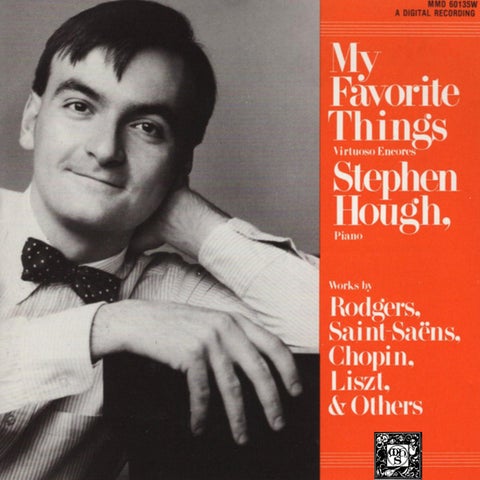

My Favorite Things

Virtuoso Encores

Stephen Hough, Piano

If pressed, many audience members admit that encores are the most enjoyable part of a piano recital. After performing Beethoven's last three sonatas, Dame Myra Hess may have asked, "What else can I play after such music?," but others have invariably followed scarcely less exalted programs with longed-for favorites or mischievously unannounced bonnes bouches. A Rubinstein recital without "Nocturne by Chopin" (always op. 15, no. 2 in F-sharp) and Falla's Ritual Fire Dance, or a Moiseiwitsch concert without Palmgren's enchanting West Finnish Dance or Rachmaninoff's vertiginous E minor Moment musical would have seemed sadly incomplete. Following in a romantic and authentic tradition, Stephen Hough feels no less happy to tickle his audience's fancy, to delight them with this or that favorite or rarity, to send them home thoughtfully humming, smiling and light-footed. Virtually all the pieces in this recital were written by pianist-composers rather than composerpianists, the majority prominent at the turn of the century. And they are somehow part and parcel of a 19th-century tradition, a love of encores, of the teasing and delectable. They could also be considered an overspill from several great pianist's careers, lavishly extending both style and technique. They are written for those who, as Horowitz would say,

can differentiate between technique and mechanics, who can extend mere facility to magical effect, molding and varying their sonority to make it glow and sparkle like the finest jewelry. The Sturm und Drang of, say, the Liszt Sonata or the F minor Transcendental Etude are alien to such music which requires an effortless elan vital and subtle stylistic awareness, an elusive elixir particularly hard to achieve in the recording studio. You quickly learn to recognize each of these composer's calling cards, his stockin-trade. Godowsky's labyrinthine textures and liquid sense of sonority can perfume and embellish even the most unlikely material. "The Gardens of Buitenzorg" (no. 8 from the Java Suite) is a notably exotic instance of his style at its most heady and alluring. Again, in Godowsky's hands Saint-Saens' The Swan takes on a whole new dimension, one in which an idealization of grace is fragmented into a magical iridescence. The virtuosity of works such as MacDowell's Hexentanz (one of two Fantasiestucke, op. 17) or Moszkowski's Caprice espagnol is more compact, less obviously luxuriant or sophisticated, though MacDowell's rapid patterning and Moszkowski's repeated notes are recognizable thumbprints or hallmarks. Both

composers were also celebrated for more serene

or lyrical virtues; Moszkowski's Siciliano is an

out-and-out charmer, an example of his picture-

-postcard impressionism at its most debonair, lilting, and insinuating.

Gabrilovitch, too, could range from the overt virtuosity of his Caprice-Burlesque to the more private and affectionate world of Melodie (dedicated to his sister), while Paul de Schlozer's A-flat Etude, enjoying a recent revival, flaunts a daunting rather than superficial difficulty. Liszt's transcription of Chopin's song The Maiden's Wish was a favorite of Hofmann, Rachmaninoff, Paderewski, and Cortot, who fell easily in love with such grateful virtuosity and openhearted affection, an inimitable tribute from one composer to another, though not without a cunning and florid Lisztian bias.

And speaking of Paderewski, who can resist the old-world courtliness of his Minuet or the gentle contrition of his more rarely heard Nocturne? Far from fading or tarnishing with the years such music acquires a new significance in our more hectic and brittle age. Levitzki's A-flat Waltz is also music of another age, a work Stephen Hough confesses somehow forbids casual dress, cries out for white tie and tails, a complementary chic and elegance. Personal and idiosyncratic, such art invites respect rather than condescension.

Of the more obviously virtuoso works Selim Palmgren's concert study, En route, is like Finnish ragtime, while Rosenthal's Papillons and Dohnanyi's F minor Capriccio (an early Horowitz speciality) exploit a gentle and fierce rain of

double notes respectively. lgnacy Friedman is

among Stephen Hough's favorite pianists, and his Musical Box, while less familiar than Liadov's

or Severac's examples, is once more an exercise in nostalgia. More virtuosic than those two classics, Friedman's box of delights discloses a scintillating figure dancing before a child's enraptured gaze and a melody embellished with the most brilliant and precise fioriture.

Finally, a brief word about Stephen Hough's own transcriptions. The choice or criterion was that the material should be both simple and beautiful, inviting variation and ingenuity in a tradition inspired by Rachmaninoff (his two Kreisler transcriptions), Godowsky, Horowitz, and Earl

Wild (his Rachmaninoff songs and Tchaikovsky Dance of the Four Swans arrangements). Richard Rodgers' My Favorite Things, for example, is sufficiently clear-cut or transparent to prompt a playing with the border lines, an embroidery like so much sparkling thread. The two Quilter transcriptions are simple recreations, delicate aquatints, graceful and inimitably English. The Kashmiri Love Song, on the other hand, takes such nostalgia into another dimension, "something to play from a faded rather than brand-new copy, and as full of a beguiling heart's ease as I could make it, " says Stephen Hough.

Here then is living proof that "serious" music is not always so serious, that style, freshness, and vitality need not be confused with levity or

volity The gulf between Richard Rodgers and many of the other composers is not, after all, so impossibly wide or unbridgeable. Here, too, is the quality of sprezzatura, of an unapologetic delight in excess and aplomb, something evocative of an age when pianists were true Kings of the Keyboard, their chosen composers little more than their serfs. Subtle, volatile, and elegantly crafted, such music also contradicts fundamental rules of classicism or decorum with an impish and often outrageous charm placed at premium level

Toronto Symphony (Klaus Tennstedt conducting), as well as with the Detroit, Baltimore, Seattle, and American Symphonies and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. In Great Britain, he regularly appears with the Royal Philharmonic, BBC Philharmonic, and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestras, as well as the Halle Orchestra at the Proms; he recently completed a European tour with the London Symphony Orchestra under Claudio Abbado. An extraordinary recitalist and chamber musician, Mr Hough has been heard in Alice Tully Hall, Ambassador Auditorium, with the Cleveland

On a more personal note, I was both touched and delighted by Stephen Hough's dedication to me of his arrangement of Richard Rodgers' My Favorite Things (an apt title for his entire recital). His inventiveness, too, made me pause to marvel and wonder at the sheer range of his artistry. A pianist who excels in Mozart, Schubert, and "late" Beethoven but who so openheartedly sets out to captivate and enchant is surely not only exceptionally versatile but a wonderfully free and liberated spirit.

Bryce Morrison, 1988

At the age of 27, pianist Stephen Hough has already appeared with many of this country's leading orchestras, and with virtually all the major orchestras in his native Great Britain. Mr. Hough's schedule has included reengagements with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony (James Levine conducting), and the

Quartet at the Metropolitan Museum, and with the Juilliard Quartet at the Library of Congress.

Born in Heswall, Cheshire, in 1961, Stephen

Hough established his presence in the American musical world after winning the prestigious

Naumburg International Piano Competition. His subsequent Alice Tully Hall recital was greeted

with much acclaim, prompting one critic to hail him as "one of the leading talents among the rising generation of young pianists."