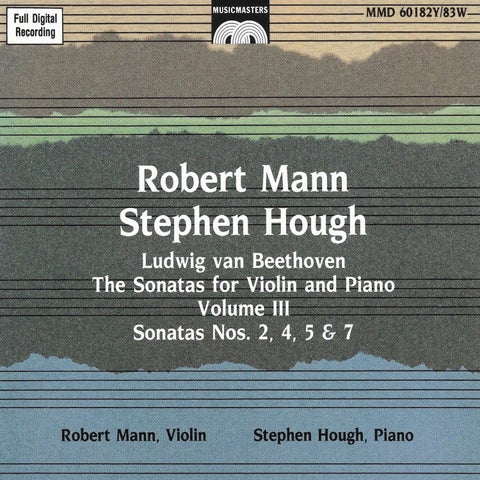

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

The Sonatas for Violin and Piano, Volume III

COMPACT DISC NO. 1

Sonata No. 2 in A Major, Op. 12, No. 2

1. Allegro vivace

2. Andante, piu tosto allegretto

3. Allegro piacevole

Sonata No. 5 in F Major, Op. 24 ("Spring")

4. Allegro

5. Adagio molto espressivo

6. Scherzo: Allegro molto

7. Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo

COMPACT DISC NO. 2

Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23

1. Presto

2. Andante scherzoso. piu allegretto

3. Allegro molto

Sonata No. 7 in C Minor, Op. 30, No. 2

4. Allegro con brio

5. Adagio cantabile

6. Scherzo: Allegro

7. Finale: Allegro

Robert Mann, Violin

Stephen Hough, Piano

One of the many reasons for Beethoven's popularity lies in his heroism, and in our sympathy for his acts of defiance through faith. Faced with overwhelming odds Beethoven shook his fist at adversity and, with magnificent arrogance, declared. "power is the morality of all men who are above the common. and it is mine. " Such an assault on convention is somehow part and parcel of a confidence which nearly but never quite collapsed under the stress of both material pressures and deep spiritual torment. Mozart was quick to advise his contemporaries about this wild untutored phoenix saying, "keep an eye on him. he will make a noise in the world. " Yet even Mozart could not imagine the sort of noise Beethoven would make or the manner in which his creative genius would roar and reverberate around the universe for eternity. Mozart was an Apollonian genius who created his

memorable beauty within an inherited and accepted framework. Beethoven. on the other hand, questioned all tradition and. dismissed as being "raw, gnarled, and unfinished" and a destroyer of form, suffered the loneliness imposed on all true pioneers. In this sense there is a world of difference between Mozart and Beethoven; between a composer of formal grace and perfection and a composer whose hammer and chisel blows are still visible on the marble of his greatest masterpieces.

composers, notably Beethoven. Yet

characteristically, Beethoven's early violin and

piano sonatas provoked bewilderment and hostility,

their pungency and novelty already far beyond

conventional or complacent taste. Thus:

It is undeniable that Herr Beethoven goes his own

gait but what a bizarre and singular gait it is!

Learned, learned and always learned-nothing

natural, no song. Yes, to be accurate, there is only

a mass of learning here, without good method;

obstinacy but for which we feel but little interest; a

striving for strange modulations. an objection to

customary associations, a heaping up of difficuities

till one loses all patience and enjoyment.

The three op. 12 Sonatas ( I 797-98) were

dedicated to Antonio Salieri, an ambiguous tribute.

Beethoven had studied with Salieri but was also

aware of his prestigious and influential position as

Imperial Kapellmeister. Privately, Beethoven's

sarcasm for such officially and lavishly sanctioned

appointments was savage and vituperative: "what

appointment at the Imperial Court could be given

to such a mediocre talent like myself. " For

Beethoven. limitless brio. the fresh breeze of a

truly pioneering spirit was th opposite of safety or

mediocrity; and pedants and conservatives, when

not openly disparaging, found the op. I 2 Sonatas

hard to place. For such unliberated spirits they

represented betwixt and between music with one

The 18th century saw major developments in the violin, both in performance and craftsmanship; an opening for rich, previously untapped technical and expressive possibilities. Such potential was

memorably explored by Mozart in his 34 violin

sonatas, a touchstone or yardstick for later

foot firmly in the 18th century and the other even

more securely in the 19th. a form of post-classicism

that, like so much musical quicksilver, was hard to

accept or categorize.

off, romping away once more in rapid 6/8 waltz

time. The sudden clouding of such high spirits only

occurs when an ominous chromatic unison line

momentarily shadows a figure whose chirruping birdcall must again have proved a sore trial for the

diehards and conservatives of musical Vienna. An exceptionally crisp 36-bar development leads to a

recapitulation and a more extensive coda. including trills like sudden bursts of irreverent

laughter before a final skittish fadeout, as if Ariel

himself had tripped away into the horizon

Movement no. 2 is in two parts, each presented by

the piano. Later the violin helps to redress the

balance as it leads a series of imitative, nearcanonic sequences. The minor key is pensive and

reflective rather than profound and later blossoms into music of a graceful, idyllic, and pastoral charm

(piacevole means agreeable). A sonata-rondo

artfully disguised as a minuet, this finale is full of surprises, including an abrupt termination of the principal theme and a near Mendelssohnian second

episode. The recapitulation, too, is concluded by a series of skips and hops and a solitary A for the piano, a terseness that is both startling yet a true hallmark of Beethoven's early exuberance, wit, and style.

A brief space separates opp. 23 and 24 from their op. 12 predecessors. yet there is a remarkable gain in scope and cogency. Both were composed in 1800, were originally intended as sharply contrasted companions. and were published together in 1801 as op. 23. It was not until 1803

that they were separated. The F major Sonata begins at once with one of the most enchanting and satisfying of all Beethoven's themes, music

truly to soothe the savage breast. The first of the

sonatas to have four movements, it underwent

considerable revision before it achieved its final and justly celebrated form. Certainly it is easy to

see how such music acquired the sobriquet

"Spring" Sonata, for the writing has an eloquence, lyricism, and vernal freshness that are immediately

taking and appealing. Such a mixture of warmth and strength is peculiarly Beethoven's own.

The second subject, with its upward-rushing chords, could be seen as no less springlike in its robustness and vitality, and the exposition concludes with a flood of scales before the development continues in bright and assertive A

major. The recapitulation continues with some

audacious transitions, and there is much play with

a figure deriving from the sixteenth-note swirl of

the first subject. The Adagio is memorably tranquil

with a rare sense of inevitability and momentum, each idea naturally and freely generating another.

The ornamentation, too, looks forward to the world of the Chopin Nocturnes, though the music's

classic poise and serenity could only be

Beethoven's. The slow tremolandi at the end

combine with a figure related to the opening Allegro's principal subject and bring this serene

music to a quiet and speculative close.

The Scherzo, with its famous quirky syncopation and whirling scales, is barely over a minute in length, and almost before we realize it the final Rondo, with a theme scarcely less haunting than that which opens the sonata, is in progress, music

once more alive with all the light and colors of a spring day. That is not to say that the music is

uneventful. The theme is subtly and stylishly varied and is not without some characteristic touches of turbulence and agitation. The coda introduces

fresh material, yet even at this late state it is

perfectly integrated into the general spirit of the

music, accentuating rather than detracting from its

most accessible nature.

A minor is rare in Beethoven, and, apart from the

String Quartet, op. 132, it is hard to think of another masterpiece in this key. Energy of a

sharper less amiable nature than op. 12, no. 3

animates the op. 23 Sonata, a work whose opening

Presto resolutely proclaims its key of A minor.

Playful sforzandos become anguished and stabbing, the entire movement nervous, restless, and full of attenuated fits and starts. The

development continues with unabated activity

while a brief pause for breath signals an

expansively treated theme built on the first subject.

This leads in turn to the recapitulation and later to

a coda. which abruptly terminates music of the

greatest force and urgency. The Andance

scherzoso has a succession of couplets which

create both a restful yet quirkily humorous effect. and a brief fugato leads finally to sixteenth-note

arpeggios confirming the music's piquancy and,

literally, offbeat humor. The finale is fierce and gusty, its principal idea presented in a lithe two-

part texture. There is a miniature adagio cadenza

or recitative, a return to the principal idea. a "ping-

pong" dialogue between piano and violin. and a theme and variation coda.

Forster once called "the C minor of life. " Today. it

is difficult to appreciate fully the originality of

music of such somber strength and power. The Sonata "strides forward like Beethoven himself.

dark-browed. Tempestuous” and so urgent is the

argument that the customary repeat is omitted lest

it mar or stem the music's impetus and forward

momentum. The piano's two ominous opening

questions are sufficiently terse to allow for limitless

permutation and development; and these, together

with the following chromatic descent. are vital

germinal ideas in a tense and gruff progression.

The second subject in E-flat is superficially lyrical

or relaxed, and only a rush of scales fully releases

the music's pent-up energy. In the development the

piano counters the violin's lyrical line with the

Sonata's opening question, and an exceptionally

full and expansive coda brings the movement to a

tumultuous end.

In the Adagio a conventional melodic line is

magically enlivened by "modern" and novel

harmony. Beethoven originally conceived this

movement in G major but finally opted for the

richer if controversial key of A-flat. A secondary

idea has the violin singing high above delicate

"pointillist" arpeggios. and the reprise includes a surprising dotted-rhythm comment from the violin.

After many reminders of the music's overall scope

the movement ends calmly, the violin singing once

more above the piano’s scales. Characteristically,

the Scherzo and Trio [which Beethoven, who

doubted their worth, mercifully retained) have

sufficient offbeat accentuation and sudden

The op. 30. no. 2 Sona

contrast to lend an ambiguity of mood. Even the mellifluous Trio is not without its bracing

.

linking it to rather than contrasting it with the

Scherzo's mercurial nature. The Finale is another

full sonata-rondo, its principal subject dark and

potentially explosive before an expansion into

something lighter and less ominous. Such material

is ripe for development and elaboration and follows

a grimly determined course. And although the

music is periodically lit by a more benign treatment.

the presto is a fast and furious surprise Here all

the rage inherent in that ominous opening theme is

released with all of Beethoven's darkest energy.

Bryce Morrison, 1989

A founder and one of the original members of the

Juilliard String Quartet, Robert Mann was born on

July 19. 1920 in Portland. Oregon. He began study

of the violin with local teachers at the age of nine

In 1941. Mann won the Walter W. Naumburg

Foundation competition and made his New York

debut two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor In

1946. at the invitation of William Schuman. then

president of Juilliard. he formed the Juilliard String

Quartet

Mann appears frequently as a soloist and has

recorded a number of solo works He serves also as

the president of the Walter W. Naumburg

Foundation and is a member of the New York

Philharmonic Board He has devoted a great part of his life to teaching; among his ensemble pupils are

the La Salle, Tokyo, American, Concord, Emerson,

New York, Mendelssohn, and Alexander Quartets,

as well as many other active musicians of our times

who play an important role in the solo-and

chambermusic world

as well as many other active musicians of our times

who play an important role in the solo-and

chambermusic world.

Pianist Stephen Hough has appeared with many of

this country's leading orchestras, and with virtually

all the major orchestras in his native Great Britain.

His recent schedule included reengagements with

the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Chicago

Symphony (James Levine conducting), and the

Toronto Symphony (Klaus Tenstedt conducting),as

well as with the Detroit, Baltimore, Seattle, and

American Symphonies and the Saint Paul Chamber

Orchestra. In Great Britain. he regularly appears

with the Royal Philharmonic, BBC Philharmonic, and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestras, as

well as the Halle Orchestra at the Proms; he

recently completed a European tour with the

London Symphony Orchestra under Claudio

Abbado. An extraordinary recitalist and chamber

musician, Hough has been heard in Alice Tully Hall and Ambassador Auditorium, with the Cleveland

Quartet at the Metropolitan Museum, and with the

Juilliard Quartet at the Library of Congress.

Born in Heswall, Cheshire. in 1961. Stephen Hough

established his presence in the American musical world after winning the prestigious Naumburg

International Piano Competition. His subsequent Alice Tully Hall recital was greeted with much

acclaim. prompting one critic to hail him as “one of the leading talents among the rising generation of young pianists.”