Copland

Sonata for Violin and Piano

(Boosey & Hawkes)

[1] Andante semplice

[2] Lento

[3] Allegretto giusto

[4] Vitebsk, Study on a Jewish Theme for Piano Trio

(Cos Cob Press)

Piano Quartet

(Boosey & Hawkes)

[5] Adagio serio

[6] Allegro giusto

[7] Non troppo lento

Dennis Russell Davies, Piano

Romuald Tecco, Violin

Kenneth Harrison, Viola

Lee Duckles, Cello

Superlatives are always dangerous, but it seems safe to say that Aaron Copland is probably the most important and influential composer that the United States has yet produced. Over the course of a career that spanned half a century, this tall, modest, bespectacled man became a virtual embodiment of American music in all of its guises. He wrote symphonies, ballets, operas, sonatas and songs, in styles that were now folkish and friendly, now austere, urban and modernist, yet always retaining a distinctive sensibility, one that was his alone. Moreover, Copland is one of the few composers of his time held in equal esteem by professional musicians and the general public. Such works as El salon Mexico, Billy the Kid, Fanfare for the Common Man and Rodeo have entered the standard repertory - classics all, and as distinctively American as Huckleberry Finn.

Yet Copland is, in one sense, a neglected composer, for the vast majority of his music -- including virtually everything he wrote before 1930 or after mid-century -- remains unknown to the public at large. Unfairly so, for there are masterpieces throughout the Copland canon, from the brash, jazzy and once-shocking early works (when Walter Damrosch led the first performance of Copland's Organ Symphony, he turned to

the audience and said, "If a young man at the age of 23 can write a symphony like that, in five years he will be ready to commit murder!"), through late works such as The Tender Land (which critic B.H. Haggin thought one of the three great American operas) and the splendidly assured Piano Fantasy, composed in memory of William Kapell.

This disc contains three works by Copland which have been long admired by musicians but have never fully entered the standard literature. The earliest of these is Vitebsk, a trio for violin, cello and piano which Copland wrote in 1929 and subtitled "Study on a Jewish Theme." The actor Peter Ustinov has described this brief, highly compact work as a "little tone poem." "It is raucous, hard and dry as splintered wood, and impregnated with a landlocked melancholy," he wrote, in fresh, vivid language that professional critics can only envy. "The piano, used not only percussively but as a carillon, sounds as Russian as it does Jewish, with the passioante and relentless pealing which punctuates the 'Death of Boris."'

Ustinov continued: "Suddenly, all this garish abruptness gives way to a liquid flow, as though the Hasidic energies have been unleashed and God forgive me if a very

French clarity and brittleness doesn't overtake the piano part, so that one can almost see Nadia Boulanger smile with pleasure at her gifted pupil. The baleful strings still give an impression of Semitic sadness and introspection but the picture is one of engaging clarity, with none of the oppressive sense of mission of an Ernest Bloch. It is, if you will, Jewish music filtered in Paris, using quarter tones at times to emphasize the rough edges, but at others, bursting with a Couperin-like felicity."

The Violin Sonata was composed in 1941 and 1942: it is therefore roughly contemporaneous with the far-better known Rodeo and Lincoln Portrait. Composer David Diamond has left a reminiscence of the work's creation, quoted in the invaluable volume of oral history by Copland and the musicologist Vivian Perlis, Copland: 1900 Through 1942: "In New York in the forties, I played fiddle in the 'Hit Parade' orchestra to make a living. I would come up to Aaron's loft when he was working on the Violin Sonata. I showed him things about harmonics in the last movement, and I said 'Aaron, it would be a little awkward to jump from a low note all the way up in the tenth position. Why don't you make it an artificial harmonic?' We played the Violin Sonata

together in a loft performance before it was premiered .... " The sonata may therefore be said to have the fingerprints of two important American composers on it. I am at a loss to account for its obscurity.

Finally, there is the Piano Quartet (1950), one of the first of Copland's 12-tone compositions, and a graceful, gentle and affecting piece it is. Leonard Bernstein, in one of his less inspired public pronouncements, once chided Copland for adopting 12-tone composition. Copland, in an equally public response, asserted that a composer's syntax had little to do with the ultimate value of his creation and that he was still the same composer, no matter what musical language he might choose.

I think Copland was right. His 12-tone pieces have very little to do with the dry academicism that characterized much American composition in this genre. Copland's voice is always present, and, indeed, his best music had always been disposed to careful organization. Such works as the Piano Fantasy, Connotations and Inscape -- the composer's later, thornier works, which met with public indifference and critical hostility -- deserve a reappraisal from the perspective of the 1990s, divorced

from the musical politics of their time.

After 1972, Copland stopped composing. It is one of the longest such moratoriums after Rossini and Sibelius, both of whom abandoned composition at the height of their careers and kept virtual silence for more than a quarter-century. Copland was hardly reclusive, however, and he kept active as a conductor and lecturer through the early 1980s. He regularly attended performances of his music and was helpful to young students, rarely refusing interviews or informal discussions.

"Composers differ greatly in their ideas about how American you ought to sound," Copland said to me in 1985, on the occasion of my last visit to his home in Peekskill, New York. "The main thing, of course, is to write music that you feel is great and that everybody wants to hear." For half a century, Copland lived up to his ideal, and American music will never be the same. Listeners who have only heard Copland's familiar masterpieces should find this disc a revelation: they will find that they haven't known the half of Aaron Copland.

Tim Page

The Glenn Gould Reader (1985) and Selected Letters of Virgil Thomson (1988). He is a faculty member of The Juilliard School.

Tim Page is the chief classical music critic for Newsday and the host of a radio program on WNYC-FM in New York. His books include

Widely acknowledged as one of classical music's most innovative conductors, Dennis Russell Davies is also one of the most active, holding three musical directorships and performing as guest conductor with major orchestras on both sides of the Atlantic. In his third year as General Music Director of the City of Bonn, West Germany, he is also principal conductor and cofounder of the highly regarded American Composers Orchestra and music director of the Cabrillo Music Festival. Born in Toledo, Ohio in 1944, Mr. Davies studied piano with Berenice B. McNab. He attended The Juilliard School, where he studied piano with Lonny Epstein and Sascha Gorodnitski and conducting with Jean Morel and Jorge Mester. Mr. Davies first attracted public attention in 1968, when he and Luciano Berio founded the Juilliard Ensemble. A champion of contemporary music, Mr. Davies has presented the works of such composers as William Bolcom, Philip Glass, Hans Werner Henze, Heinz Winbeck, and Arvo Part. Throughout his career, he has collaborated with a wide range of musicians, including Laurie Anderson, Keith Jarrett, Duke Ellington and Elliott Carter.

Recorded at the Performing Arts Center, University of California, Santa Cruz July 10-12, 1989

Produced, Engineered and Edited by George K. Squires

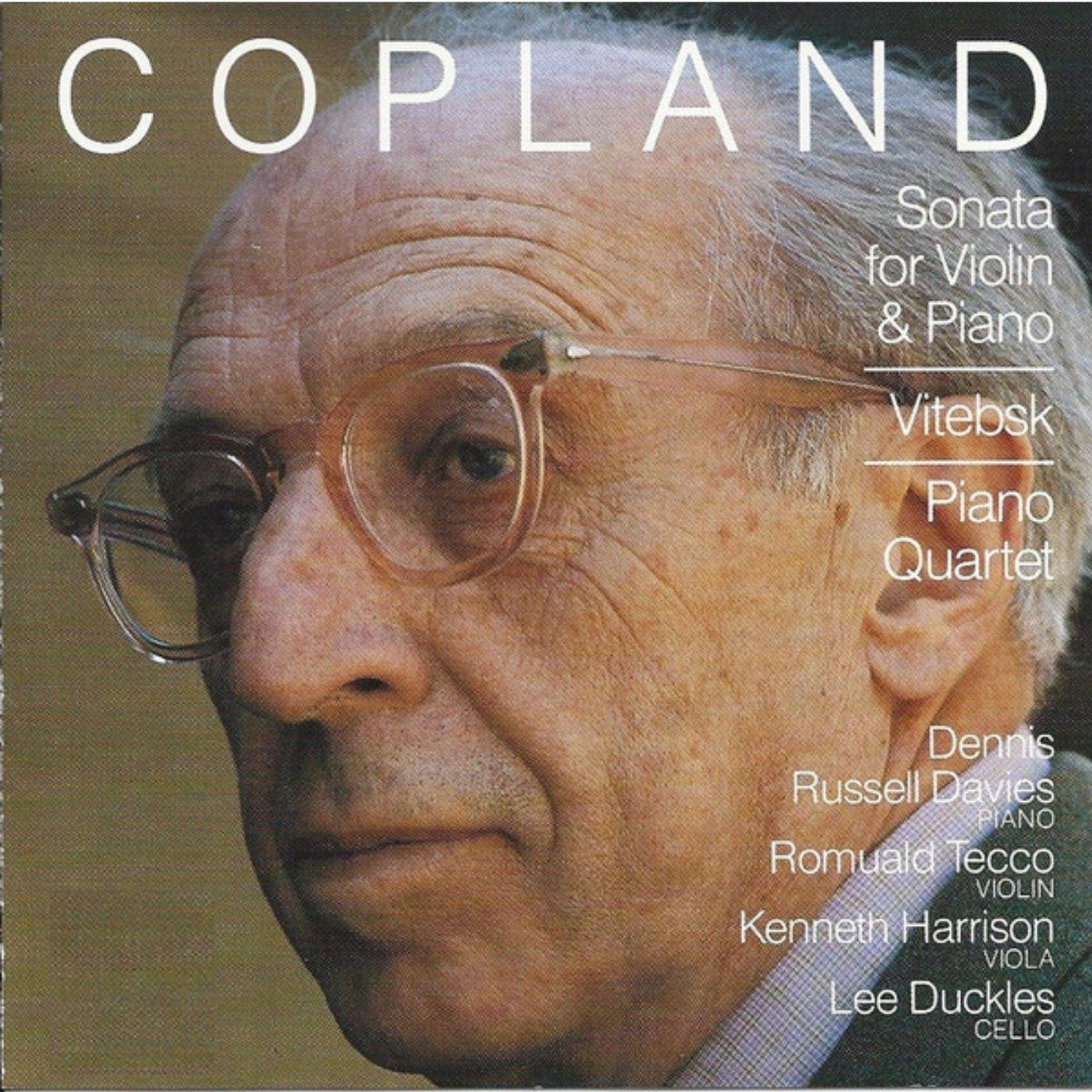

Cover Photo by Don Hunstein

Cover Design: John Berg