Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos 1962/1967

Dibujos y documentación

Investigación: Sebastián Vidal Mackinson

MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO DE BUENOS AIRES, 2016

HORACIO RODRÍGUEZ LARRETA

Jefe de Gobierno

FELIPE MIGUEL

Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros

ÁNGEL MAHLER

Ministro de Cultura

VIVIANA CANTONI

Subsecretaria de Gestión Cultural

GUILLERMO ALONSO

Director General de Patrimonio, Museos y Casco Histórico

VICTORIA NOORTHOORN

Directora del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO DE BUENOS AIRES

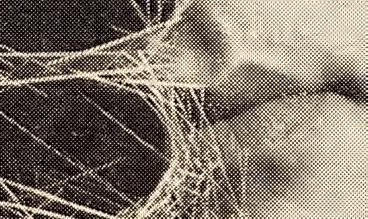

Sameer Makarius . Emilio Renart, 1964. Copia de época, gelatina de plata. 30 x 19,5 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Sameer Makarius . Emilio Renart, 1964. Copia de época, gelatina de plata. 30 x 19,5 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Noorthoorn, Victoria

Emilio Renart : integralismo : bio-cosmos 1962 / 1967 / Victoria Noorthoorn; Sebastián Vidal Mackinson. - 1a ed . - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2016.

160 p. ; 25 x 20 cm.

ISBN 978-987-673-282-6

1. Arte Contemporáneo ArgentiNºI. Noorthoorn, Victoria II. Título

CDD 709.82

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Av. San Juan 350 (1147)

Buenos Aires

Impreso en Argentina

Créditos fotográficos por página:

Área de Documentación y Registro, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes: 74-75

Área de Documentación y Registros, Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes “Emilio Pettoruti”: 125

Oscar Balducci: 37, 46-47, 50-51, 70

Nicolás Beraza: 58-59, 65 Viviana

POR

EMILIO RENART: INTEGRALISMO. BIO-COSMOS 1962/1967 POR

VIDAL MACKINSON

1961/1966

DOCUMENTACIÓN SOBRE LA SERIE INTEGRALISMO. BIO-COSMOS 1962/1967

TRES

Integralismo.

Bio-Cosmos n°1, 1962

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°2, 1963

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3, 1964

Integralismo.

Bio-Cosmos n°5, 1965

Integralismo.

Bio-Cosmos n°4, 1967

Es con gran alegría que celebro esta nueva publicación del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires sobre la obra de Emilio Renart, artista argentino que marcó fuertemente la singularidad de nuestra década del 60 y a tantos artistas argentinos de diversas generaciones. Desde el Museo, consideramos esencial volver sobre los pasos de este gran artista que buscó y encontró su propia identidad al margen de las tendencias del momento. Esperamos poder presentar pronto la gran exposición que Renart amerita. Mientras tanto, confiamos en que esta publicación, a la que se dedicó en exclusividad nuestro curador Sebastián Vidal Mackinson, contribuya a ampliar el conocimiento sobre sus dibujos y su gran proyecto Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos, que tantos misterios encierran. Este libro se centra en esta gran serie creada entre 1962 y 1967 y presenta documentación que intenta ser lo más precisa posible, publicando imágenes, universos de diálogo y recorridos institucionales de los cinco Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos que cristalizaron, en gran medida, el perfil único de Emilio Renart dentro de la escena argentina.

Por la posibilidad de realizar esta publicación, agradezco muy especialmente al Consejo de Promoción Cultural de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. También deseo expresar mi agradecimiento a la Comisión que aprobó el proyecto, entonces integrada por Juan Chiesa, María Anahí Cordero, Carlos Ernesto Gutiérrez, Astrid Obonaga, Carlos Ángel Porroni, Celso Alberto Silvestrini, y a quien la presidía, Juan Manuel Beati, por su confianza en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, que ha sido sumamente valiosa en esta etapa de crecimiento y desarrollo de nuestra institución. Agradezco, asimismo, a la actual Comisión, ahora integrada por Patricio Binaghi, María Anahí Cordero, Josefina Delgado, Astrid Obonaga, Celso Alberto Silvestrini, a su actual Presidente, Carlos Ángel Porroni, y a la Dra. Laura Pollet, subgerente operativa, por su apoyo al Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires en su tarea de dar a conocer lo mejor de nuestro arte a nuestra sociedad.

En el ámbito del Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, agradezco muy especialmente el apoyo de Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, Jefe de Gobierno, de Felipe Miguel, Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros y de Ángel Mahler, Ministro de Cultura. Extiendo mi agradecimiento a Viviana Cantoni, Subsecretaria de Patrimonio Cultural, a Guillermo Alonso, Director General de Patrimonio, Museos y Casco Histórico, y a Alejandro Capato, Director General Técnico, Administrativo y Legal del Ministerio de Cultura, y a sus respectivos equipos.

Mi agradecimiento a la Asociación Amigos del Moderno y a su Comisión Directiva por facilitar y acompañar las gestiones de nuestro museo con suma generosidad, a nuestro gran aliado estratégico, el Banco Supervielle, por su continuo y sostenido apoyo a esta institución y a nuestros sponsors Alba Artística, Aeropuertos Argentina 2000, Arte al Día, Fibertel, Fundación Andreani, Gancia, Interieur Forma Knoll y Plavicon.

En el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, agradezco a Sebastián Vidal Mackinson por su dedicada labor de investigación de la que resulta el contenido de este libro, a Marcos Kramer, responsable de la cronología, y a Gabriela Comte, Editora del Museo. Agradezco también a Fernando Montes Vera por su coordinación, a Julia Benseñor por su atenta corrección, a Juan Beccar Varela por su minucioso retoque fotográfico y a Kit Maude por su trabajo de traducción al inglés. Por último, mi agradecimiento a Adriana Manfredi por su refinado diseño gráfico.

Al momento de enviar este libro a imprenta, el equipo del Museo ha conseguido acceder a archivos parciales y que están en proceso. La investigación, por lo tanto, queda abierta. Esperamos poder avanzar en la producción de saberes y contenidos para poder continuar la tarea y deseamos que en un futuro próximo sea posible la tan necesaria exposición de Renart en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

Pérez, Elba, “Cinco obras de Emilio Renart condenadas a la destrucción”,Tiempo Argentino, Buenos Aires, 23 de marzo de 1985, p. 9

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

CV completo y original de Emilio Renart, 1967 Biblioteca

Porque Renart es un raro, cuyos rasgos distintivos son los que caracterizan a quienes se resuelven de un modo tan personal que parece como si lo anterior no hubiese dejado otras huellas en su espíritu que las que sirven para afirmar el camino.

Aldo Galli, La Prensa, 26 de mayo de 1982 1

A excepción, quizás, de Horacio Safons que, en Estudios: revista argentina de cultura, información y documentación, define a la obra de Renart como “barroquismo textural”. Y más adelante dice: “No son monstruos, porque Renart no imprime semejanzas a sus formas, ni fantasmas, porque no les da apariencias. Son más bien máquinas biológicas escapadas de la honorabilidad del cuerpo humano, signos de afirmación en una dimensión desconocida” (abril de 1968, Nº590, p. 57).

La producción artística de Emilio Renart (1925-1991) es una de las más singulares del siglo XX en la Argentina. La historia del arte y la curaduría todavía mantienen una deuda pendiente con su estudio, sistematización y visibilidad, porque gran parte de su producción, tímidamente conocida, se ha destruido debido a que el mismo artista desechó piezas y otras se malograron por la calidad de los materiales con los que estaban realizadas o porque la gran dispersión de su obra en colecciones privadas y públicas, nacionales e internacionales, y no ha habido una publicación o exposición que las reúna.

Este libro, Emilio Renart: Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos 1962/1967. Dibujos y documentación, busca reparar la falta de estudios sobre su producción y se centra en la serie señalada, realizada entre los años arriba mencionados. Ensaya una reconstrucción lo más precisa posible de imágenes, universos de diálogo, recorridos institucionales de los cinco “Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos” que cristalizaron, en gran medida, el perfil único de Emilio Renart dentro de la escena argentina desde su aparición, a inicios de la década del sesenta. Las razones de este objetivo se deben a que, salvo Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1, del patrimonio del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, y la sección central de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3, en el acervo del Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes “Emilio Pettoruti” de La Plata, el resto de los objetos o bien fueron destruidos por el propio Renart o bien se perdieron o se destruyeron por diversos motivos. Varios dibujos y piezas dispersas sobreviven en colecciones privadas, pero se sabe poco sobre los “monstruos”, como los llamó parte de la prensa coetánea.1 Con este objetivo se recopilaron diversas fuentes de archivo, (como notas periodísticas, catálogos de muestras, fichas de ingreso de obras a colecciones museísticas) y se realizaron entrevistas y pesquisas en colecciones privadas, con el fin de dar a conocer de manera conjunta una de las producciones artísticas más singulares del siglo XX en Argentina.

Emilio Renart abordó lo artístico desde distintas aproximaciones bajo el concepto de “integralismo”. Desde esta posición comprendió la producción de artefactos

visuales, la investigación y escritura de lo que entendió por “creatividad” y el ejercicio de la docencia de manera sostenida por varios años. Así, integralismo2 es el postulado principal con el que se acercó a la práctica artística, que sostuvo y buscó condensar de manera primigenia en el corpus de obras reunidas bajo el nombre de “Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos”. Este, según lo entendió, funcionaba como principio totalizador en el uso conjunto de elementos de disciplinas que tradicionalmente actúan por separado. Así, si por un lado lo pensaba como la posible concatenación de elementos interdisciplinarios con el objetivo de llegar al máximo de las posibilidades de los medios plásticos (el dibujo, la pintura, la escultura); por el otro, y bajo el rótulo de “creatividad”, postuló la potencia creadora y demarcadora de la imaginación que cada uno de nosotros posee en tanto ser humaNºToda su producción se puede mirar y analizar desde este prisma utópico de expandir los límites establecidos que representó en su práctica artística, condensó en su trabajo de escritura de textos para catálogos (por ejemplo, para la exhibición Investigación sobre el proceso de la creación realizada junto a Kenneth Kemble, Enrique Barilari y Víctor Grippo, en 1966), plasmó en el libro Creatividad, publicado en 1987, y accionó sobre la esfera pública en su tarea como docente en talleres de instituciones.

2 Integralismo significaba conceptualmente unir, asociar partes que tradicionalmente se oponían–pared, piso, escultura, pintura, dibujo–. Todo ello unido por una imagen y un estilo personal. En 1966 amplió ese concepto dando lugar a mis distintas facetas creativas: escritos, inventos, investigaciones, obras plásticas, etc...

La aparición y acción de Emilio Renart en el campo artístico de Buenos Aires de la década del sesenta fue vertiginosa. Entre 1961 y 1967 participó en prácticamente todos los “espacios calientes” donde un artista joven que buscara expandir los límites de lo artístico debía estar: exhibiciones individuales y colectivas en las galerías centrales de la ciudad, como Peuser, Lirolay y Pizarro; reconocimientos y galardones importantes, entre los que se encontraron las menciones honoríficas de pintura del Premio Varig de Artes Plásticas de 1961 y del Premio Ver y Estimar de 1963, la mención especial en el Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella en 1964, el Primer Premio de Dibujo en el Concurso Georges Braque, organizado por la Embajada de Francia, su participación en el Premio Internacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, ambos en 1965, y la intervención dos años más tarde en el envío argentino a la IX Bienal de San Pablo junto a Juan Carlos Distéfano y David Lamelas. A pesar de este ascenso meteórico, en el que la historia y él parecían ser cómplices y se permitían adelantarse mutuamente en esta carrera hacia “lo nuevo”, Renart mantenía, postulaba y cultivaba un perfil independiente con respecto a sus coetáneos. “No creo en la obra de arte como fin en sí misma, sino como medio para comunicar mi propia problemática existencial. Me considero un plástico científico, porque me interesa bucear lo que hay en mí, pero también las leyes que rigen el universo. Por eso creo que al acto de crear no se le pueden endilgar calificativos: la obra de arte es, y todo lo demás es redundancia”,3 sentenciaba. En la misma nota publicada en el semanario Primera Plana en 1965 sostenía su identificación

3

Entre la ciencia y el erotismo, en Primera Plana, suplemento Artes y Espectáculos, 19 de enero de 1965, p.34.

con la “actitud creadora de los revoltosos representantes de la abstracción lírica” pero, a su vez, se distanciaba y marcaba diferencias con respecto a ellos: “Como expresión plástica —confiesa—, creo que estoy al margen, que soy un solitario”.

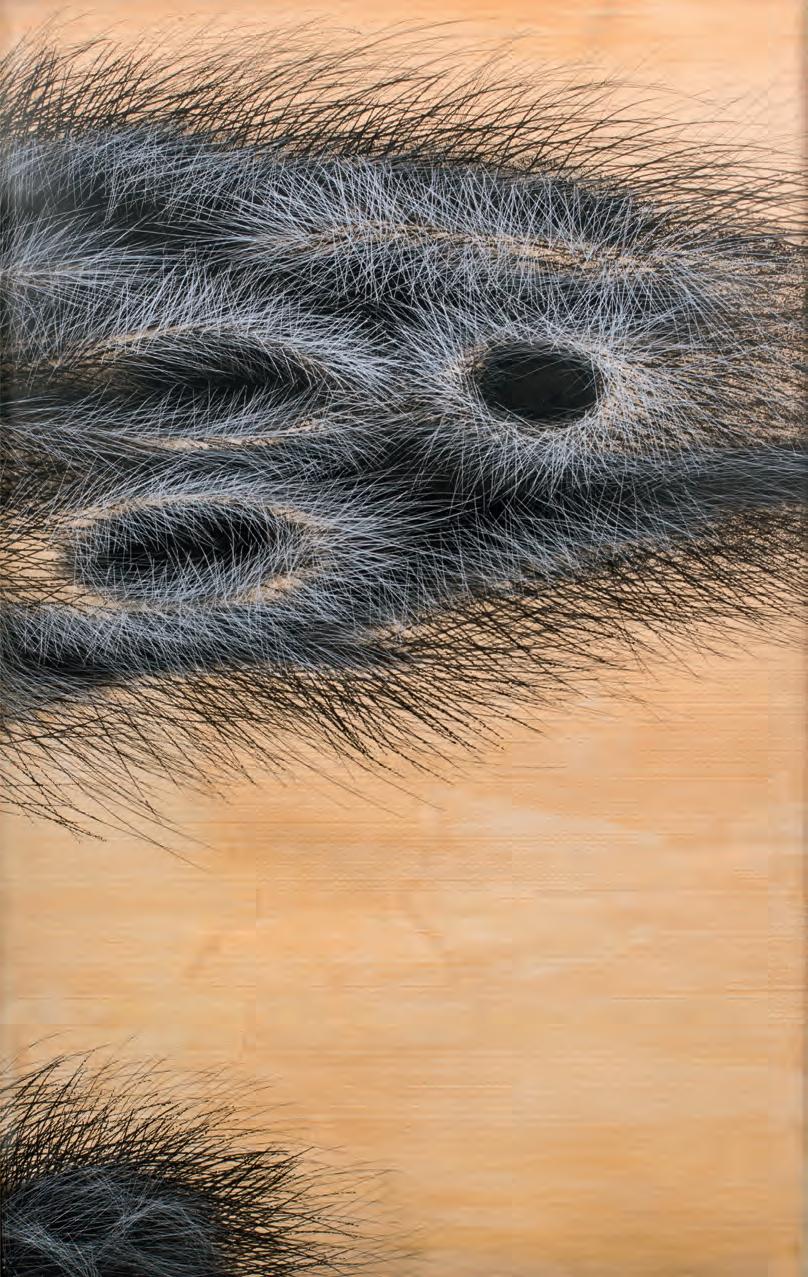

Los Bio-Cosmos se diferenciaban de la producción de sus coetáneos nacionales e internacionales no sólo en términos de los asuntos representados (con la excepción de cierta familiaridad con la imaginería espacial y lunar que Antonio Berni y Raquel Forner estaban realizando en la misma época) sino también en cuanto al uso de materiales (aunque hay una relación con Rubén Santantonín y Alberto Heredia en la manipulación de ciertos materiales). Estructuras metálicas de tela, pintura, resina, mica, fibra de vidrio, yeso, arena, sistemas lumínicos, objetos de desecho, entre otros, fueron los materiales que utilizó para los “monstruos” tridimensionales que, en la mayoría de los casos, iban acompañados de dibujos que también compartían la representación del entorno biológico, físico y espacial. Estos objetos se componían de piezas que fusionaban el dibujo, la pintura y la escultura, y que ocupaban el espacio tridimensional, hechas de hendiduras y concavidades que evocaban imaginarios híbridos modelados entre la histología, la anatomía sexual femenina, la astronomía, la física y la tecnología.

Renart combinaba una imaginería poco usual dentro de la historia del arte argentiNºLa representación de objetos con claras referencias a lo erótico en piezas que prácticamente eran vaginas, vello púbico u objetos con mucha carga sensual se armonizaban con formas que remitían al interés suscitado en la cultura visual por la conquista del espacio estelar iniciado con ahínco desde mediados de la década del cincuenta. Como afirmó Safons, “…máquinas biológicas escapadas de la honorabilidad del cuerpo humano, signos de afirmación en una dimensión desconocida”, que presentaban un nivel erótico y sexualizado inaudito para la época. Objetos sensuales de carácter lunar con una epidermis un poco humana y con algo robótico, topográfico y árido. Objetos corporizados que salían al encuentro del espectador condensando varios tópicos de una década en pleno movimiento.

Esta sensualidad provocaba controversias entre el público y la crítica especializada en arte. Los Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1, n°2 y, sobre todo, el n°3, se focalizaban en el órgano sexual femenino: grandes, medianas y pequeñas vaginas ocuparon los lugares centrales de estos objetos. Vaginas lunares que se presentaban entre el espanto y la fascinación y que posiblemente se imbuyeran de la representación de la mujer que circulaba en las revistas pulp de ciencia ficción, género que tenía un desarrollo importante en el país. Una de las primeras manifestaciones de este género se dio a través de estas revistas a partir de la segunda mitad de la década del cincuenta: Hombres del Futuro (1957), Más Allá (1953-1957), Pistas del espacio (1957) y Hora Cero Semanal, a las cuales seguirán en las décadas posteriores otras como Minotauro (1964), invadieron la cultura visual con nuevos motivos sobre lo cósmico, la biología, la tec-

nología, la mujer. Hasta 1957 ninguna de estas publicaciones periódicas incluyó a autores argentinos hasta que se publicó El Eternauta (1957) en el suplemento semanal Hora Cero, considerada como la primera expresión adulta de la ciencia ficción en nuestro país. Creada por el guionista Héctor Germán Oesterheld y el dibujante Francisco Solano López, a la calidad e innovación de la historia se le sumó el hecho de que la acción se situaba en la Argentina. Las calles de Vicente López donde la historia de Juan se inicia, el combate de la General Paz, el estadio de River Plate, Plaza Italia, la estación de subterráneo Congreso señalaban una cercanía geográfica que hizo accesible, tangible y posible el imaginario de la ciencia ficción en un tono mucho más cercaNºEse género que se acostumbraba a ver, a apreciar y que detonaba procesos de identificación se revelaba con toda su potencia en estas latitudes. Esta cercanía y localización cotidiana y conocida le confería un tono realista que se escapaba de las formas paródicas o aventureras que se acostumbraba utilizar.

Por su parte, Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°4 y n°5, hoy destruidas, formalizaron una ampliación en su horizonte de diálogo, propio de la década del sesenta, que gestó un clima de nerviosismo provocado por las potencias mundiales ante la eventualidad siempre inminente de un desenlace apocalíptico de la Guerra Fría. La crisis de los misiles entre la U.R.S.S, Cuba y U.S.A en 1962 fue un punto especialmente tenso en ese conflicto. Las posibles implicancias de la potencia atómica expresaban el eco siniestro y traumático de lo sucedido en las ciudades japonesas de Hiroshima y Nagasaki como una amenaza latente de su capacidad destructiva. A su vez, casi en su mismo doblez histórico, también tuvo lugar por esos años la denominada “Carrera Espacial”, esa asombrosa saga motorizada por las mismas potencias mundiales que competían en su afán hacia lo nuevo en términos de industrialización, tecnología, ciencia, que se corporizada en cohetes, astronautas y una nueva cultura visual desarrollada a ambos lados de la Cortina de Hierro. Si los satélites expresaban la disputa por la conquista del espacio exterior, la cultura occidental desarrolló y propagó las exploraciones estelares bajo las formas visuales de la ciencia ficción que utilizaba a la maquinaria de la industria del entretenimiento, también en plena expansión: series animadas como Los Supersónicos (su primera emisión fue en 1962), los films 2001 Odisea del Espacio, de Stanley Kubrick, y Barbarella, de Roger Vadim y protagonizada por Jane Fonda (1968), o canciones populares como “Space Oddity”, de David Bowie (1969), son algunas manifestaciones de las ficciones amparadas en estos años de intensa actividad en el corrimiento de las fronteras hasta entonces conocidas.4

“Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos” fue el primer conjunto de obra coherente de Renart, que pensó y proyectó como serie a lo largo de cinco años. El primer mojón irrumpió en la escena porteña en 1962 en la Galería Pizarro con motivo de su exposición individual en un espacio comercial, y el último tuvo su aparición en 1967, cuando ofició como representante, junto a David Lamelas y Juan Carlos Disféfa-

4

Nota del autor: agradezco las conversaciones que he mantenido con Florencia Qualina sobre estos puntos.

no, del envío argentino a la IX Bienal de San Pablo. A lo largo de estos cinco años, y a pesar de ser diagramada y pensada como una serie con sus lógicas internas y sus maneras propias de exhibirse, se distingue una modificación en el conjunto que se formalizó entre su participación en el Premio Nacional Di Tella de 1964 y el Premio Internacional Di Tella de 1965. Su primera etapa comprende a Bio-Cosmos n°1 (1961), n°2 (1963) y n°3 (1964), donde configuró un interés por la anatomía sexual femenina, la astronomía, las ciencias biológicas, la zoología, la histología y la ciencia ficción; y la segunda, que incluye Bio-Cosmos n°4 y n°5, las relaciones que estas piezas evocaban con respecto a la ciencia y la tecnología se impregnan de la conflictividad que atraviesa la cultura social del siglo XX con relación a la instrumentalización científica y a la física nuclear. En las respectivas pronunciaciones poéticas que se incluyen en los catálogos de cada exposición de los premios señalados, Renart es claro en cuanto a sus intereses: si en Bio-Cosmos n°3 postuló su creencia en la capacidad creadora de la humanidad bajo el signo del “integralismo”; en 1965, con Bio-Cosmos n°4, argumentó este mismo punto de manera más científica y aseveró: “Si aceptamos la posibilidad de que todo humano está dotado de similares cualidades, podría deducirse que estamos llegando lenta, pero progresivamente, a la explosión del átomo de la psiquis. / En 1945, públicamente se demostró la explosión del físico”. La precisión en la fecha es la clara referencia a los bombardeos atómicos que realizó Estados Unidos sobre distintas ciudades de Japón en el marco de la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

Con esta demarcación a un suceso histórico que selló el curso de la historia mundial, Renart presentó modificaciones en sus piezas. Los últimos dos Bio-Cosmos adquirieron monumentalidad y espectacularidad y, si bien ya había utilizado artilugios lumínicos en la pieza central de Bio-Cosmos n°3, en estos dos siguientes este sistema de complejizó: las luces se volvieron intermitentes al ritmo de los latidos del corazón humano (Bio-Cosmos n° 5) o se localizaron para resaltar volúmenes y concavidades (Bio-Cosmos n° 4). A su vez, comenzó a utilizar materiales de producción industrializada, como la resina poliéster y la fibra de vidrio, y cada “monstruo” (cada vez menos morfológico) adquirió verticalidad, de manera que sostenía el avance de sus distintas partes hacia el espacio frontal: volúmenes, concavidades, esferas que parecían flotar y ocupar el espacio con mayor ligereza. Esta capacidad constructiva se vio facilitada por el uso de los nuevos materiales. Así, si los tres primeros Bio-Cosmos presentaban referencias claras al órgano sexual femenino, a la visualización del territorio lunar y cierta antropomorfización fantasiosa, los dos siguientes presentaban un nuevo pliegue en este horizonte visual y cultural.

El cambio formal en las piezas de “Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos” señalado (presentación más espectacularizada, profundización del horizonte con el que dialogaban sus piezas) ocurrió después de su participación en el Premio Nacional a las Artes Visuales de 1964, una de las instancias legitimadoras que caracterizaron una

manera de producir arte durante esos años en la Argentina. Renart competía con otros nueve artistas argentinos, entre los que se encontraban Marta Minujín, Jorge de la Vega y Roberto Aizenberg, entre otros. El jurado estaba compuesto por Clement Greenberg (Estados Unidos), Pierre Restany (Francia) y Jorge Romero Brest (Argentina), quienes discutieron si entregar el Primer Premio a Renart o a Marta Minujin. Renart recibió el apoyo de Clement Greenberg, mientras que a Marta Minujin la apoyó Pierre Restany. El desempate a favor de ella se dio por la acción de Jorge Romero Brest, quien a su vez le otorgó una Mención Especial a Renart. Este suceso, por demás anecdótico, señala que a partir de esta instancia de consagración operada por la institución privada más legitimada, y legitimizante, de la Argentina y con estos nombres oficiando como jurado, se vuelven palpables y visibles las modificaciones formales, constructivas y estructurales que operaría Emilio Renart sobre su obra posterior. Al año siguiente, en 1965, invitado como artista al Premio Internacional de la misma institución, presentó Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°4, una estructura de resina poliéster ondulante que ocupaba el espacio desde el muro. Casi simétrica, en su centro se erigía una forma exenta que evoca la representación científica de los átomos y en la que parece que el dibujo y la pintura dejaban paso al trabajo más escultórico y objetual. Un par de años más tarde, al participar en el envío argentino a la IX Bienal de San Pablo junto a Juan Carlos Distéfano y David Lamelas, Renart presentó Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°5, acompañado de un corpus de dibujos. Nuevamente priorizó la frontalidad de la pieza: una sucesión de esferas lumínicas avanzaba sobre el espacio apagando y prendiéndose al ritmo de las pulsaciones del corazón humaNºAquí, vuelve a aparecer la relación primigenia entre dibujo, pintura y escultura, y de manera inaudita, un rico uso del color.

A su vez, estas dos instancias –el Premio Internacional Di Tella y la IX Bienal de San Pablo– eran dos eventos de alta visibilidad promovidos por gestiones públicas y privadas con el afán de posicionar el arte argentino en la escena internacional. Así, si cierta dinámica institucional (sistemas de premios, becas, envíos nacionales a bienales, etc.) habilitaba a que cada instancia de exposición llevara a arriesgar, a proyectar la concreción de piezas antes inimaginables en el aparente sinfín de posibilidades que acontecían en la Argentina, a Renart no le era sencillo realizar sus piezas ni tampoco que ingresaran a colecciones privadas o públicas. Si este sistema propiciaba la producción de artefactos cada vez más experimentales y contagiaba la energía hacia “lo nuevo” habilitando la osadía, la coyuntura personal de Renart hacía que tuviera que enfrentarse diariamente a claras limitaciones. Realizaba cada uno de estos Bio-Cosmos en su taller, de tamaño mediano, donde tenía que armar y desarmar pieza por pieza cada día para hacer lugar y poder seguir produciendo. A su vez, el mercado no se sentía atraído a adquirir algunas de sus obras más espectaculares y sólo las dos que han llegado a la actualidad lo hicieron porque ingresaron a los acervos de museos por canales oficiales de adquisición de obra. Una (Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n° 1) por disposición del

Esta enumeración sigue el modelo propuesto por Marcelo E. Pacheco en “De lo moderno a lo contemporáneo. Tránsitos del arte argentino 1958-1965”, en Katzenstein, Inés, Escritos de vanguardia. Arte argentino de los años 60, Buenos Aires, Fundación Espigas, 2007.

director del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, Hugo Parpagnoli, y la otra (Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n° 3) por participar y ser premiada con una Mención en el Salón Anual de Artes Plásticas de Mar del Plata de 1966. De esa manera, esta última pieza pasó a integrar el patrimonio del Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes “Emilio Pettoruti” de La Plata.

La escena artística y algunas condiciones de producción

Este lustro centelleante (1962-1967) se entramó en una coyuntura histórica muy precisa. Una sucesión de acontecimientos de orden político y cultural definieron la posibilidad de que cierta práctica artística, denominada de vanguardia o “arte nuevo”, pudiera desarrollarse con características particulares, principalmente en la ciudad de Buenos Aires. En este clima, dado por un encadenamiento de toma de decisiones, “Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos” tuvo su condición de posibilidad y su propia sentencia de colapso. Estas condiciones de producción, como muchos de los desarrollos de la práctica artística de entonces, se enmarcaron dentro del llamado “arte nuevo”, cuyo inicio puede ubicarse alrededor de 1956 con la irrupción del informalismo en la escena porteña. Un año antes, para un sector de la intelectualidad argentina, la “Revolución Libertadora” había señalado la culminación de una etapa de retroceso, aislamiento, atraso y populismo, condiciones que, según ellos, caracterizaban las políticas del gobierno peronista de los años anteriores. Este nuevo discurso con intenciones de renovación operó, a su vez, junto a políticas que se gestionaron para la escena cultural: una serie de acontecimientos diversos imprimieron una nueva dinámica constituida por instituciones públicas y privadas, galerías de arte, posicionamientos discursivos de críticos, colectivos de artistas, exposiciones, sistema de premios, etc. Se diagramó un escenario sobre la ruptura que se operaba con relación al arte moderno y la incipiente consolidación de lo contemporáneo.

En este sentido, resulta esclarecedor tener en cuenta varios sucesos y gestiones de actores que moldearon un perfil de una parte del acontecer del arte argentino entre 1956 y 19685:

1. La fundación del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires y la reapertura del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes en 1956, cuyos directores, Jorge Romero Brest (MNBA), Rafael Squirru y Hugo Parpagnoli (MAM), posibilitaron canales de producciones teóricas y artísticas;

2. El Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, fundado en 1958, junto al Centro de Artes Visuales, inaugurado en 1960, dirigido por Romero Brest desde 1963, operaron como el marco institucional más prestigioso y experimental en el ámbito privado;

3. La implantación y el desarrollo de una serie de premios a las artes visuales que demarcaban las tendencias de “lo nuevo”: los premios nacionales e internacionales del Instituto Torcuato Di Tella (desde 1960), el Premio de Honor Ver y Estimar (1960 a 1968), la Bienal Americana de Arte de Córdoba y el Premio Braque instituido (desde 1963) por la Embajada de Francia fueron instancias de legitimación y aliento hacia el ensayo artístico;

4. El accionar de galerías comerciales con respecto a la práctica artística más experimental. Si Galería Bonino fue el espacio de mayor consagración y visibilidad, un grupo de galerías jóvenes también incidieron en su expansión: Lirolay, Pizarro, Guernica y Antígona dieron cauce a exposiciones de intención rupturista;

5. La incidencia de críticos como Hugo Parpagnoli, Julio Payró, Aldo Pellegrini, Jorge Romero Brest y Rafael Squirru en publicaciones en diversos medios sobre el desarrollo de una nueva red institucional, como jurados de premios y envíos al exterior de exposiciones y bienales, se completaba con una labor de divulgación por medio de la docencia y las conferencias;

6. El deseo de introducir el arte argentino en los circuitos internacionales llevó a que se presentaran exhibiciones nacionales en Europa y Estados Unidos, y a que el Estado articulara las participaciones argentinas en las bienales de San Pablo, Venecia y París con aportes del ámbito privado. Como parte de esta estrategia, el Instituto Torcuato Di Tella y la Bienal Kaiser (Córdoba) incluyeron jurados y artistas internacionales en sus certámenes, entre los que cabe mencionar a Lawrence Alloway, Giulio Argan, Clement Greenberg, André Malraux, Herbert Read, Pierre Restany, Lionnello Venturi y Otto Hahn.

7. Por último, los viajes y las estadías de trabajo de los artistas en el exterior se motorizaron gracias a un sistema de becas, como las incluidas en los premios del Di Tella, los programas de apoyo del Fondo Nacional de las Artes, los concursos del Servicio Cultural de la Embajada de Francia (Premio Braque) y las otorgadas por algunas fundaciones estadounidenses, como la Guggenheim.

Sobre este entramado de gestiones llevadas adelante por agentes institucionales, individuales, de carácter público y privado, se concentró el inicio del arte contemporáneo en la Argentina. Informalistas, hacedores de objetos, conceptuales, arte destructivo y nueva figuración saltaron a la escena artística con el objetivo de radicalizar los mecanismos formales y materiales de realización, romper los modos tradicionales de promoción y legitimación, e incluso de consumo de la práctica

artística. Fueron varios los artistas que operaron en esta cruzada: Alberto Greco, Kenneth Kemble, Rubén Santantonín, Marta Minujín, Luis Felipe Noé y Jorge de la Vega y que con sus propuestas desafiaron el límite de lo artísticamente correcto. Entre ellos también se encontraba Emilio Renart.

Esta dinámica de producción mostraba dos caras: el aliento a la creación y a la legitimación, y a la vez la competencia feroz. A pesar de esta efervescencia hacia “lo nuevo”, los canales de circulación, de adquisición de obras y de formalización de la profesión eran precarios. “... llegué a una situación tope en 1968, me sentía muy mal y aprovechando una Beca del Georges Braque me fui a París, donde estuve cinco meses. Evidentemente yo quería huir de mi país, de mis amigos, de mi familia, es decir, quería huir de mí y ahí en Francia me hice una pregunta fundamental: ¿qué me está pasando? Me di cuenta de que estaba envuelto en un individualismo tremendo, entonces ¿cómo solucionaba eso? Dejar o atenuar ese individualismo significaba que tenía que descubrir a los demás; a partir de ese momento comencé a desarrollar mi componente social, hasta ese momento estaba con mi persona y peleando con los demás, ahí me di cuenta de que ese componente social no estaba desarrollado”.6 Harto de competir y de actuar en esas condiciones de la escena, Renart decidió correrse de la centralidad de la escena cultural porteña y dar por cerrada la serie “Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos”. No abandonó su práctica artística (de hecho, participó en varias exposiciones colectivas en la Argentina y en el extranjero con obra que seguía realizando), sino que focalizó su atención en la docencia, la investigación y escritura de lo que entendía por “creatividad”.

En una entrevista ofrecida unos años más tarde, Renart analogó los Bio-Cosmos con la década del sesenta: “Porque lo que me aconteció a mí —aunque parezca una saga melodramática— se repite con la obra de mis colegas, con una persistencia que denuncia los modelos tanáticos que nos rigen. Es hora de definirse por el imperio de Tánatos o el de Eros, por la destrucción o por la vida. Mi elección es bien clara. Los fundamentos del Integralismo no hacen sino dar cuerpo teórico a esta elección por la vida. Los cinco Bio-Cosmos exaltaban plásticamente la generación de la materia, el momento de la creación pura y primaria. No es casual que la destrucción haya perseguido a estas obras. Es la evidencia, una más, de lo ocurrido en la Argentina en estos veinticinco años. Me preguntan hoy qué significó el Di Tella, cómo era aquella década del sesenta. La respuesta sirve para contestar las dos preguntas: existía la posibilidad de equivocarse. Importaba más la dinámica que los resultados, y esta coyuntura permitió a muchos abrir canales expresivos inéditos; a otros, quizás los más, para incurrir en los vicios de la competición o el snobismo. Si bien Jorge Romero Brest era la figura más notoria del Di Tella, es a Guido a quien corresponde el mérito mayor: porque él creía en la necesidad de experimentar en todos los campos, y el instituto iba más allá de las artes plásticas. Sería una pérdida de tiempo recordar este aniversario

del Di Tella en función melancólica, como recordamos a los héroes, por pura nostalgia. Lo importante es recrear, cada día, las grandes posibilidades que la vida tiene implícitas. Jugarse al Eros”.7

Desde esta posición, la de mirar retrospectivamente unos años signados por la experimentación artística y la emergencia de nuevos actores dentro de la escena, entre los que él se encontraba, Renart enunció su malestar: el snobismo y la competencia lo llevaron a correrse de la escena para dedicarse a profundizar su labor escritural y de docencia. Mostrando señales de extenuación, vio que se maravillaban con sus Bio-Cosmos al mismo tiempo que los marginaban. Se los consideraba rarezas, objetos de una frenética experimentación y de un acercamiento particular hacia lo artístico. La única manera que lograrían institucionalizarse, ser legado en la historia, se concretó a través de su ingreso al patrimonio museístico, por la gestión personal de Hugo Parpagnoli, director del MAM y promotor de “lo nuevo” o por los canales más tradicionales de adquisición de obras: la premiación en un salón de arte. De esa manera, Bio-Cosmos n°1 y Bio-Cosmos n°3 son las dos únicas piezas que, aun con dificultades, 8 lograron perdurar en el tiempo a esa magnífica saga que todavía hoy activa “Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos”.

Desde esta misma posición, también podemos posar la mirada sobre esos años intensos para seguir analizando trayectorias artísticas y reflexionando sobre dinámicas institucionales que caracterizaron a una escena que habilitó que los artistas se arriesgaran a confeccionar piezas de gran envergadura bajo las coordenadas de “lo nuevo” y que, en un mismo doblez, no pudo contenerlos.

7

Cinco obras de Emilio Renart condenadas a la destrucción. Pertenecían a la serie “Integralismo BioCosmos”, perdida o deteriorada irremediablemente. No es casual, dice el plástico, en Tiempo Argentino, sección Cultura, viernes 29 de marzo de 1985, p. 9

Sin título, 1959

Tinta y acuarela sobre papel

32,5 x 20,5 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1959

Tinta y acuarela sobre papel

32,5 x 20,5 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1959

Tinta, témpera y acuarela sobre papel

32,5 x 20,7 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1959

Tinta, témpera y acuarela sobre papel

32,5 x 20,7 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1959

Cromo-yeso

35,4 x 44 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1959

Cromo-yeso

33,5 x 37,4 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

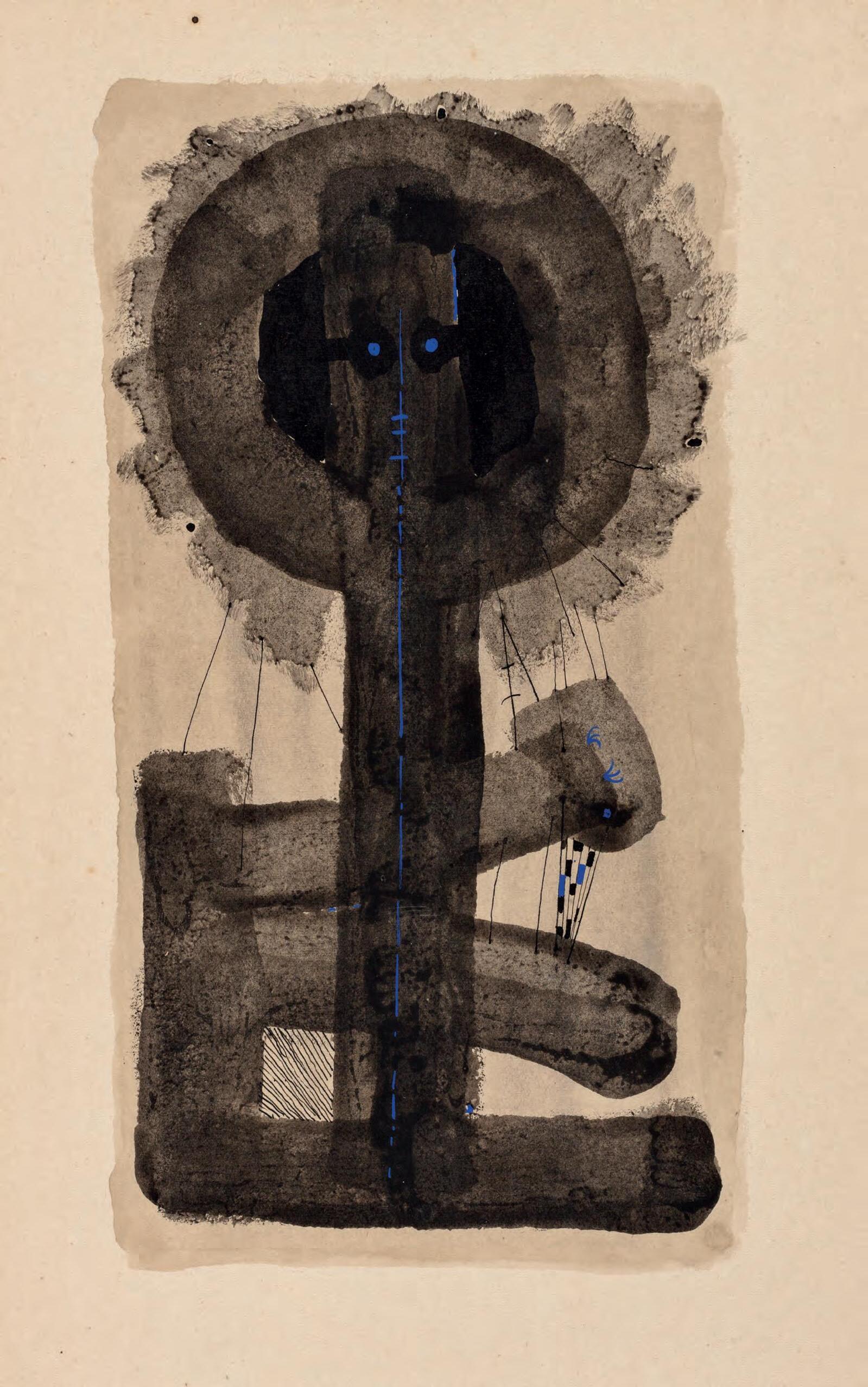

Emilio Renart realizó obra sobre papel de manera prolífica. El grupo de dibujos aquí reunidos comparten el universo de sentido de la serie “Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos.” Biológicos, sensuales, misteriosos, enmarañados, hicieron su primera aparición pública en la exposición Renart en Galería Pizarro en 1962 y la última en la IX Bienal de San Pablo de 1967. Así, en ocasiones se expusieron junto a los Bio-Cosmos y en otras funcionaron como investigación formal y de inserción en el mercado de obras de arte.

Comparten el interés por la representación biológica, molecular, lunar y anatómica al igual que los objetos de la serie. Filigranas en tinta negra o blanca, témpera de diversos colores, o lápiz sobre papel de una precisión que llegó, incluso, a que ciertos coetáneos sospecharan del trazo preciso del artista y postularan el uso de una máquina especialmente diseñada para su confección.

En este apartado se dan a ver dibujos pertenecientes a colecciones privadas y públicas.

A su vez, se muestran una selección de pinturas de paisajes lunares de diversos tamaños, que anticipan cierta volumetría que plasmaría en los subsiguientes “Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos.”

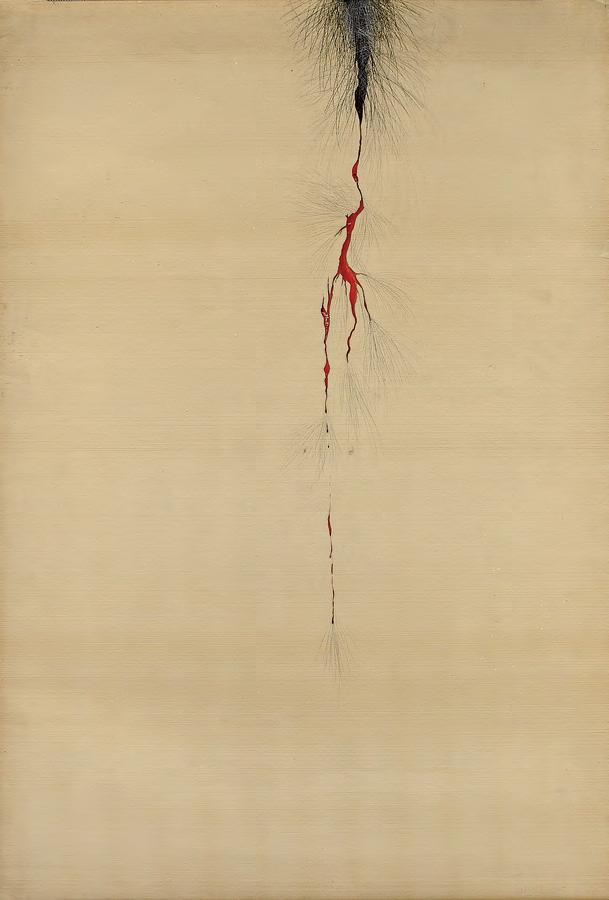

Dibujo n°2, 1965

Técnica mixta sobre papel

76 x 125 cm

Colección MALBA, Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

Dibujo nº8, 1965

Tinta y aguada sobre papel

76 x 125 cm

Colección MALBA, Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1965

Tinta sobre papel

110 x 74 cm

Colección particular, Nueva York

Sin título, 1965

Tinta sobre papel

74 x 110 cm

Colección particular, Nueva York

Sin título (detalle), 1965

Técnica mixta sobre papel

109 x 74 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Sin título (detalle), 1965

Técnica mixta sobre papel

76 x 54 cm

Colección particular

Sin título, 1965

Tinta y aguada sobre papel

76 x 112 cm

Sin título, 1964

Dibujo, tinta, tinta blanca sobre papel

76,5 x 112 cm

Colección Museo de Arte

Moderno de Buenos Aires, Adquisición 1968

Dibujo n°21, 1965

Técnica mixta sobre papel

49,7 x 76 cm

Colección Eduardo F.

Costantini, Buenos Aires

Dibujo n°9, 1964

Técnica mixta sobre papel

112 X 76 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1965

Técnica mixta sobre papel

75 x 55 cm

Sin título, 1962

Técnica mixta sobre papel

112 x 76,5 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Dibujo n°4, 1964

Técnica mixta sobre papel

75 x 112 cm

Colección Eduardo F. Costantini, Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1962

Técnica mixta sobre papel

112 x 72 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1964

Lápiz sobre papel

73 x 43 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Dibujo n°14, 1965

Técnica mixta sobre papel

76 x 125 cm

Colección MALBA, Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1965

Técnica mixta sobre papel

76 x 40 cm

Sin título, 1964

Técnica mixta sobre papel

74 x 54,5 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Dibujo n°30, 1965

Tinta, aguada y pigmentos sobre papel

112,5 x 76 cm

Colección MALBA, Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

Sin título, (detalle),1965

Tinta sobre papel

110 x 74 cm

Colección particular, Nueva York

Dibujo n°1 (Serie Biocosmos), 1966

Témpera y tinta sobre papel

76 x 115 cm

Colección Museo Nacional de Bellas

Artes, Buenos Aires

Adquisición - a RENART, Emilio 1966

Nº Inv. 7431

Sin título, 1962

Técnica mixta sobre tela

41 x 30 cm c/u

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Introversión cósmica B, 1961

Pintura, arena y barnices

184 x 99 x 2 cm

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Sin título, 1962

Pintura, arena y barnices

182 x 141 cm

Colección particular, Buenos Aires

Entre 1962 y 1967 hicieron su aparición cinco Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos. Participaron de exposiciones individuales, colectivas, premios nacionales e internacionales y envíos argentinos a Bienales de Arte Internacional. Salvo el n°1 (en Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires) y una parte del n°3 (en Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes “Emilio Pettoruti”), el resto se destruyó por decisión del propio Renart o por circunstancias ajenas a su radio de acción.

Estructuras metálicas, tela, pintura, resina, mica, fibra de vidrio, yeso, arena, sistemas lumínicos, objetos de desecho, fueron algunos de los materiales que utilizó para los “monstruos” que componían de piezas que integraban el dibujo, la pintura y la escultura. Renart combinaba una imaginería poco usual dentro de la historia del arte argentino: la representación de objetos con claras referencias a lo erótico se armonizaba con formas que remitían al interés suscitado en la cultura visual por la conquista del espacio estelar iniciado con ahínco desde mediados de la década del cincuenta. Como afirmó Safons, “…máquinas biológicas escapadas de la honorabilidad del cuerpo humano, signos de afirmación en una dimensión desconocida”, que presentaban un nivel erótico y sexualizado inaudito para la época. Objetos de carácter lunar con una epidermis un poco humana y con algo robótico, topográfico y árido.

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1, 1962 Estructura metálica, aluminio, lienzo, pinturas, arena tamizada por granos, yeso, cola vinílica, tul, aserrín, resina poliéster

230 x 300 x 90 cm

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires Comienza con un dibujo pintado de blanco. Limitando esa superficie el color se torna tierra anaranjado y se convierte a su vez en un relieve que toma tonos pardos. Este relieve se transforma en un objeto realizado con una estructura metálica forrada con lienzos tensados y materiales varios que mide 230 x 300 x 90 cm, que se puede descomponer en tres partes desarmables de color tierra siena tostada virada al negro. La parte superior del objeto presenta una especie de cabeza con un orificio por el cual se puede percibir la transparencia de un vidrio que, de acuerdo al desplazamiento del observador, cambia de tono yendo del amarillo al azul, pasando por el rojo. En el centro de su extremo derecho hay un orificio por donde se observa el interior. El objeto se apoya sobre patas de alambre.

Patrimonio del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires por adquisición directa del entonces director Hugo Parpagnoli.

Exposiciones:

Integralismo, Galería Pizarro, 1962.

Objetos 64, Museo de Arte Moderno, 1964.

Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno, 1964.

Squirru, Rafael, “El arte de las cosas”, Revista Américas, Washington, agosto 1963, p. 15-19

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, _ca. 1962 Fotografía de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1. Copia de época, gelatina de plata

18 x 24 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, _ca. 1962

Fotografía de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1. Copia de época, gelatina de plata

24 x 18 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, _ca. 1962

Fotografía de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1

Copia de época, gelatina de plata

15 x 10,3 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Renart, Buenos Aires, Galería Pizarro, 28 de agosto al 15 de septiembre de 1962

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Ficha de ingreso de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1 a patrimonio Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 1968 Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1 y n°2 Vista de sala de Exposición Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Estos Bio-Cosmos son los únicos dos de la serie que se expusieron juntos en la exposición Buenos Aires 64 que produjo la empresa Pepsi-Cola con la organización y colaboración del Museo de Arte ModerNºLa exposición se desarrolló en las salas del museo porteño y, luego, en Pepsi-Cola Exhibition Gallery de Nueva York. Los Bio-Cosmos no viajaron a Estados Unidos debido a problemas de traslado.

A su vez, se expusieron también en la exposición organizada por Hugo Parpagnoli en el Museo de Arte Moderno, Objetos 64.

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Objetos 64, Buenos Aires, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 1964

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, “A caballo sobre la cabeza del David de Miguel Angel”, Todo Buenos Aires, n°11, 10 de diciembre de 1964, p. 53

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, _ca. 1964

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1 y n°2 en exposición Buenos Aires 64, Buenos Aires, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Copia de época, gelatina de plata

8,5 x 13,7 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires 64, Buenos Aires, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 1964

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, _ca. 1964

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1 y n°2 en exposición Buenos Aires 64, Buenos Aires, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Copia de época, gelatina de plata 13,7 x 8,5 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, _ca. 1964

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°1 y n°2 en exposición Buenos Aires 64, Buenos Aires, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Copia de época, gelatina de plata 8,5 x 13,7 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

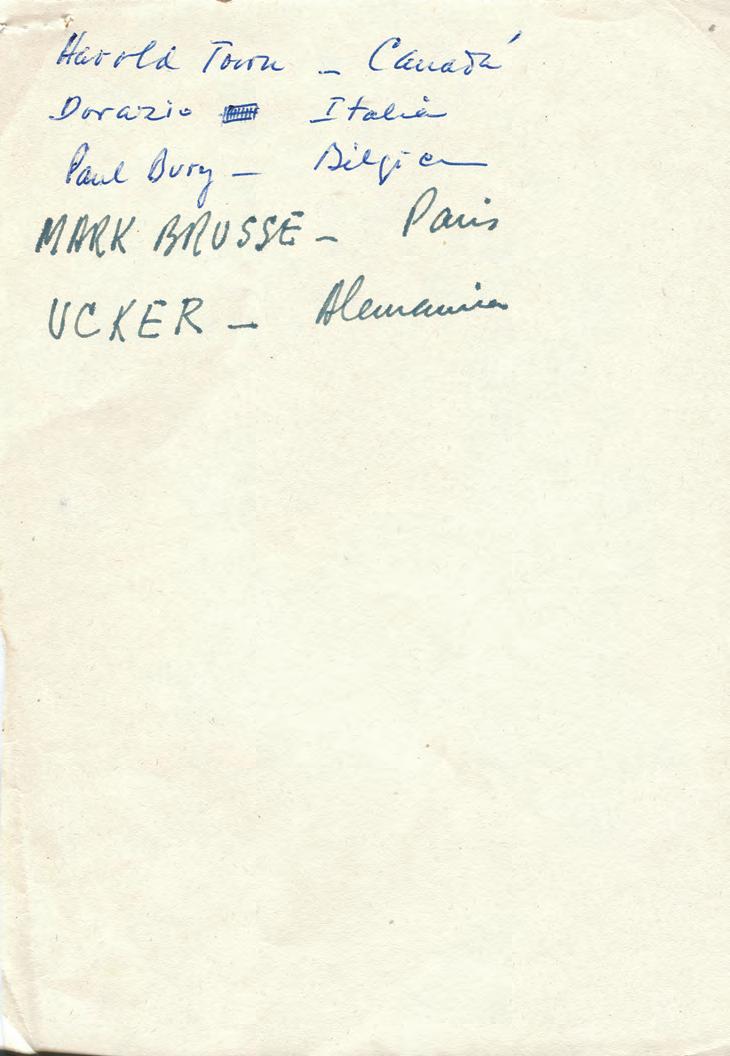

Lista de artistas de Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, 1964

De izquierda a derecha: en el suelo, Pablo Mesejean y Rubén Santantonín; de pie, Nemesio Mitre Aguirre, Emilio Renart y Zulema Ciordia. A la derecha, Marta Minujín y Ary Brizzi, en Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. Copia de época, gelatina de plata

24 x 18 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Entrevista a Emilio Renart para Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Entrevista a Emilio Renart para Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, 1964

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°2 en exposición Objetos 64, Buenos Aires, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Copia de época, gelatina de plata

17 x 24 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°2, 1963 Estructura metálica, aluminio, lienzo, pinturas, arena tamizada por granos, yeso, cola vinílica, tul, aserrín, resina poliéster 230 x 350 x 120 cm

Tanto la organización como los materiales empleados eran los mismos de los utilizados en Bio-Cosmos n°1. El cuadro madre, un relieve realizado con arena tamizada por granos, tenía tonos azules metalizados desde donde emerge un objeto de color tierra siena tostada, virada en su interior que presentaba orificios por donde se podían observar puntos luminosos. Estaba apoyado sobre diversas patas de alambre negro y podía descomponerse en trece partes desarmables. Tenía una medida de 230 x 350 x 120 cm. Sin lugar para guardarlo y sin que hubiera ningún comprador que lo adquiriera, Emlio Renart regaló la pieza a un vendedor ambulante de botellas interesado en la estructura metálica

Exposiciones:

Premio Ver y Estimar, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1963. Objetos 64, Museo de Arte Moderno, 1964. Buenos Aires 64, Museo de Arte Moderno, 1964.

Anónimo, 1964

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°2 (detalle) en exposición Objetos 64, Buenos Aires, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Copia de época, gelatina de plata. 13,6 x 8,5 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

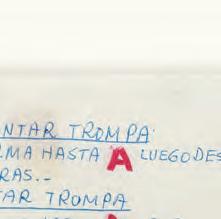

Instructivo de montaje de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°2, 1963 Lápiz, acuarela y tinta sobre papel

22 x 18 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, 1964 Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°2 (detalle) en exposición Objetos 64, Buenos Aires, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Copia de época, gelatina de plata

8,5 x 13,5 cm

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, “Entre la ciencia y el erotismo”, Primera Plana, 19 de enero de 1965 (detalle)

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, “Renart”, Imagen en el mundo del arte, 13 de agosto de 1965, p. 51 (detalle)

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3, 1964 Estructura metálica, aluminio, lienzo, pinturas, arena tamizada por granos, yeso, cola vinílica, tul, aserrín, resina poliéster

240 x 190 x 210 cm

(Originalmente: Sector A 220 x 350 x 40 cm / Sector B 280 x 640 x 260 cm)

Colección Museo Provincial Bellas Artes

“Emilio Pettoruti”, La Plata

Compuesto de dos sectores divididos cada uno en tres objetos, representaba formas orgánicas femeninas y masculinas. Es el BioCosmos que mayor extensión ocupaba. El sector A medía 220 x 350 x 40 cm., y tenía objetos laterales y uno central. El sector B, por su parte, tenía una superficie de 280 c 640 x 260 cm., y también estaba formado por tres objetos diferentes. Confeccionado por una estructura metálica, con aluminio, lienzo, pinturas, arena tamizada por granos, yeso, cola vinílica, tul, aserrín, resina poliéster, hoy sólo se conserva una zona, prácticamente restaurada, en el Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes “Emilio Pettoruti” de La Plata.

Exposiciones:

Premio Nacional Torcuato Di Tella, Centro de Artes Visuales, 1964. Obtiene Mención Especial. Salón Anual de Artes Plásticas, Mar del Plata, 1966. Obtiene una mención.

Sergio Sorrentino, 1964

Emilio Renart junto a Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3 en Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Harari, Paula, “Renart”, Pintores Argentinos del Siglo XX. Renart, Centro Editor de América Latina, Buenos Aires, 1981, p. 7

Anónimo, 1964

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3 (detalle) en Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Harari, Paula, “Renart”, Pintores Argentinos del Siglo XX. Renart, Centro Editor de América Latina, Buenos Aires, 1981, p. 5

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3 (detalle), 1964 Estructura metálica, aluminio, lienzo, pinturas, arena tamizada por granos, yeso, cola vinílica, tul, aserrín, resina poliéster

240 x 190 x 210 cm

Adquisición XXV Salón de Arte de Mar del Plata, 1966

Colección Museo Provincial Bellas Artes “Emilio Pettoruti”, La Plata

Anónimo, 1964

Emilio Renart junto a Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3 en Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964 Parpagnoli, Hugo, Argentina. Distéfano, Lamelas, Renart. Argentina, IX Bienal de San Pablo, 1967.

Catálogo envío argentino a Bienal de San Pablo 1967

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Emilio Renart, 1964

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3 (detalle) en Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Parpagnoli, Hugo, Argentina. Distéfano, Lamelas, Renart. Argentina, IX Bienal de San Pablo, 1967.

Catálogo envío argentino a Bienal de San Pablo 1967

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

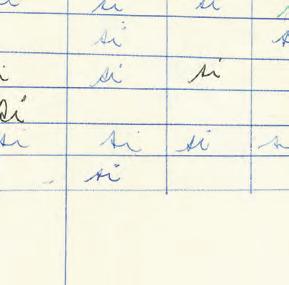

Lista de artistas para Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Dictamen de los miembros del jurado de premiaciónClement Greenberg (Estados Unidos), Pierre Restany (Francia) y Jorge Romero Brest (Argentina)- de Premio Nacional Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Memorandum de artistas seleccionados y miembros del jurado Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

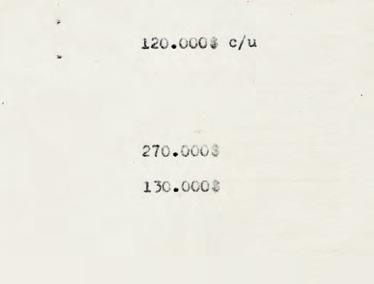

Precios de obras participantes en Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra

Emilio

Reproducido en Parpagnoli, Hugo, Argentina. Distéfano, Lamelas, Renart, IX Bienal de San Pablo, 1967.

Catálogo envío argentino a Bienal de San Pablo 1967

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Carta de Nicolás Rubio a Samuel Paz, director adjunto de Centro de Artes Visuales de Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, a raíz de obras expuestas en Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Anónimo, ca_1964

Tira de contacto de vistas de exposición

Premio Nacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Córdova Iturburu, “Arte apto y no apto para menores en Di Tella”, El mundo, 27 de septiembre de 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Fèvre, Fermín B., “El premio nacional Di Tella 1964”, El cronista comercial, 6 de octubre de 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Uribe, Basilio, “Premio Di Tella 64”, Criterio, 24 de septiembre de 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Fèvre, Fermín B., “El salón internacional Di Tella”, El cronista comercial, 13 de octubre de 1964

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

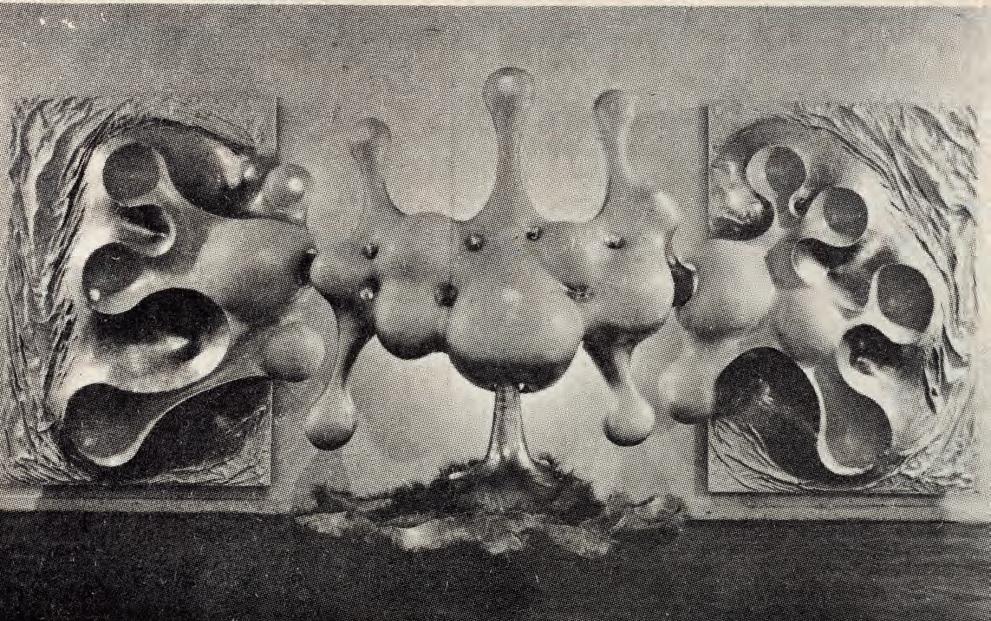

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°4, 1965 Estructura metálica, tul endurecido con yeso mezclado con agua y cola vinílica y mascarillas en resina poliéster 250 x 500 x 200 cm

Este objeto de 250 x 500 x 200 cm., estaba compuesto por siete partes desarmables. Renart utilizó una estructura metálica, tul endurecido con yeso mezclado con agua y cola vinílica, y mascarillas en resina poliéster. Presentaba formas orgánicas: dos laterales adheridas al muro y una central sostenida por las otras dos. El sector suspendido era de color blanco en las salientes y aluminizado en las entrantes. Apoyado en un pilar tratado con laminados de aluminio, se proyectaba sobre el piso en oquedades de color naranja bordeado por pilosidades y por detrás funcionaba una fuerza lumínica asincrónica parpadeante.

Renart conservó esta obra hasta 1971 cuando, cansado de transportarla de un lugar a otro y de cuidarla, la donó al Instituto de Arte Latinoamericano que canalizaba las obras donadas al Museo de la Solidaridad. Luego del golpe de Estado a Salvador Allende, la pieza entró en clandestinidad y se pierde completamente.

Exposiciones:

Premio Internacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Centro de Artes Visuales, 1965.

Anónimo, _ca 1965

Contacto de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°4 en Premio Internacional Instituto Torcuato Di Tella 1965

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965, Buenos Aires, Centro de Artes Visuales Instituto Torcuato Di Tella

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, ca_ 1965

Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965, Buenos Aires, Centro de Artes Visuales Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, p. 62

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, ca_1965

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°4 en Parpagnoli, Hugo, Argentina. Distéfano, Lamelas, Renart.

IX Bienal de San Pablo, 1967. Catálogo envío argentino a Bienal de San Pablo 1967

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, ca_1965

Tira de contacto con vistas de Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965, Buenos Aires, Centro de Artes Visuales Instituto Torcuato Di Tella

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Propuesta de artistas participantes en el Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Propuesta de artistas participantes en el Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Propuesta de artistas participantes en el Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Copia de Invitación a Emilio Renart para participar en el Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Gacetilla de prensa

Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Gacetilla de prensa

Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Emilio Renart, 1965 Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°4 en Harari, Paula, “Renart”, Pintores Argentinos del Siglo XX Renart, Centro Editor de América Latina, Buenos Aires, 1981, p. 7

Dictamen de los miembros del jurado de premiación -Giulio Argan (Italia), Alan Bowness (Inglaterra) y Jorge Romero Brest (Argentina)- de Premio Internacional Torcuato Di Tella 1965

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Anónimo, ca_ 1967

Detalle de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°5

Acompañaban seis dibujos en tintas de colores de 115 x 75 cm., dispuestos tres a cada lado, sintetizando el nacimiento, desarrollo y muerte de las esferas. Del muro libre entre los dibujos emergía un objeto que se descomponía en treinta y cuatro partes desarmables y ocho esferas apoyadas a lo largo de un montículo de arena, cubriendo una superficie de 240 x 230 x 100 cm. Realizada en resina poliéster y con un sistema lumínico pulsátil, presentaba un elemento central del que emergía una célula formada por dos esferas, una incluida en la otra. La primera se hallaba suspendida en el espacio y caía en las otras apoyadas en el suelo. Cada una representaba diez años de vida y de la primera a la última se mostraba el proceso de degradación de lo orgánico. La séptima simbolizaba la muerte orgánica y el desprendimiento de la psiquis que se libera mientras que la octava, por último, la muerte orgánica en su completud. La psiquis, figura perfecta suspendida en el espacio, implicaba el retorno a la fuente como energía generadora de una nueva célula-vida. De regreso a Buenos Aires la obra se destruyó y los dibujos, que habían sido adquiridos por el Museo de Rhode Island, se habían extraviado durante el trayecto.

Exposiciones:

IX Bienal San Pablo, Fundación Bienal de San Pablo, 1967

Emilio Renart, ca_ 1967

Fotografía de Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°3, reproducido en Harai, Paula, “Renart”, Pintores Argentinos del Siglo XX Renart, Centro Editor de América Latina, Buenos Aires, 1981, lámina VI

Parpagnoli, Hugo, Argentina. Distéfano, Lamelas, Renart. Argentina, IX Bienal de San Pablo, 1967. Catálogo.

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Nona Bienal de Sao Paulo 1967, Fundación Bienal de Sao Paulo. Catálogo

Biblioteca Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Anónimo, ca_ 1963

Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos n°2 (detalle), reproducido en catálogo IX Bienal de Sao Paulo

Fundacao Bienal de Sao Paulo, 1967

Anónimo, “San Pablo, jalón de madurez del arte argentino”, Análisis, n° 342, 2 de octubre de 1967, p. 42-46 Fundación Espigas, Buenos Aires

Anónimo, “El crítico Ignacio Pirovano será jurado en la IX Bienal de San Pablo”, La Capital (Rosario), 21 de septiembre de 1967 Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Anónimo, “Artes Plásticas: designan la delegación”, El Mundo, 3 de septiembre de 1967

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

Anónimo, “Envíos argentinos a las bienales de San Pablo y de París”, La Nación, 3 de septiembre de 1967

Fuente: Archivos Di Tella. Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Se agradece el material facilitado por la Biblioteca Di Tella para la realización de esta obra.

TRES TEXTOS DE EMILIO RENART: RENART EXPONE (1962)

INVESTIGACIÓN SOBRE EL PROCESO DE LA CREACIÓN. RENART, KEMBLE, BARILARI Y GRIPPO (1966) CREATIVIDAD (1987)

28 de agosto al 15 de septiembre de 1962, Galería Pizzaro, Buenos Aires

Frente a la realidad que tiende a subdividir los esfuerzos. Frente a los estados fluctuantes, es decir dinámicos, que nos hacen dudar de nuestra anterior seguridad. Frente a lo inesperado que se oculta dentro de lo aparentemente absoluto. Frente al plano, al volumen o a la descarnada línea. Frente a la necesidad de saber que esconden esos sub-totales de mi total y la posibilidad de que existan armoniosamente. Frente a la problemática de todo esto y del hacer, traté de reunir en una obra mi resultante actual, es decir tuve la necesidad de integrarme. Este integralismo me llevó en profundidad, dado que acepto la posible coexistencia combativa de los elementos, siempre que vivan en un ámbito común que los contenga y los armonice sin desmedro de la integridad individual. Posiblemente eso, no se dé como manifestación constante en mí, por lo que admito desde ya, el hecho de desarrollar independientemente lo que mi necesidad expresiva impronta, sin límites, y más, creo que este estado, no puede responder a una estable sin forzar la acción creativa.

El orden y la aventura signan con idéntico rigor al hombre y su existencia. Porque si bien el devenir muestra su juego de creación y destrucción ininterrumpidamente, lo hace dentro del marco de posibilidades que le configuran inexorablemente los principios, las normas, los esquemas, los misterios, la gracia, los mitos, las aureolas, en sustantivación decreciente pero valedera en todos sus matices jerárquicos para componer las “Verdades Inamovibles”, esas que por inamovibles se gastaron, pero que por verdades se mantiene, no importa si forzando su vigencia, al solo efecto de asegurar, para la posteridad de nuestros antepasados los beneficios de una vida higiénica, en la que las maravillas maravillen, los dolores duelan, y lo que vale valga. Súmese a esto del cordón de seguridad casi inviolable que constituyen la falta de contemporaneidad en las vivencias (y su consecuencia obligada: los desniveles en la evolución) por una parte, y el déficit en la administración de la cultura (que hace que la mayoría no esté posibilitada de asimilar las formas de expresión contemporánea y muchos menos de iniciarse o intentar la creación), y tendremos, listo para aplastarnos (o ser aplastado, depende del sector que se elija) el inconmensurable y endeble panorama de nuestras circunstancias. Y afirmamos que no le sirve a nadie.

Por eso, incluidos en la interrelación estático-dinámica que nos sustancia, trataremos de ordenarnos con verdades que se basten a sí mismas, y a movernos dentro de ellas, sin prestigios geográficos que las avalen y nos entorpezcan, y sin recursos históricos que las sustenten y nos inmovilicen.

Para ello cancelamos la inspiración, los raptos emotivos que ella implica, y la hora del crepúsculo para el sufrimiento fecundo y vamos a borrarnos las comillas con que nos vienen cercando la tarea, y vamos a ser artistas o creadores integrando las frases del mismo modo con que pretendemos integrar la sociedad: como sujetos determinados por un quehacer específico al que es posible acceder con intención y libertad.

Consecuentes con lo alegado, afirmamos:

1. Creemos que todo humano está dotado de cualidades semejantes y que la diferencia estriba en el grado de desarrollo de los medios expresivos (medios físicos y psíquicos). Constituimos este grupo de estudio con la intención de verificarlo.

2. Consideramos, por lo tanto, a la expresión creadora con característica multifacética.

3. Aceptamos las deficiencias expresivas por falta de desarrollo de los medios (sicofísicos) como elementos fundamentales que conducen al proceso de desarrollo del individuo y no como lacras que deben ocultarse (canalización positiva de la creación).

4. No establecemos diferencias que puedan impedir el desarrollo de las necesidades expresivas de la creación en nuestros congéneres. Este esquema será una creación en la medida que modifique el esquema de otros, en caso contrario, sólo tendrá las características de una creación intrascendente, pero valiosa, ya que modificó el esquema de los firmantes.

Invitamos pues a incorporarse a este grupo de estudio –no movimiento- a todos cuantos crean que la creación es una actitud abierta y en continuo desarrollo.

Buenos Aires, 1987

Introducción

La creatividad es una palabra de la que mucho se habla y poco se investiga. Normalmente sirve para producir hechos más o menos originales que luego pueden derivar, o no, en factores de consumo. Esto, a mi entender, configura un uso de las personas que los genera, quienes quedan relegadas cuando tal capacidad se atenúa.

Mi intención apunta a un mejoramiento del individuo, ya que entiendo que todos somos creativos por el hecho de ser seres racionales. La diferencia estriba en la trascendencia o no de esa creatividad.

Se habla de la necesidad de un cambio, pero no del nivel en que debe producirse. Pienso que si no ocurre en las profundidades de la psiquis, todo será una apariencia para no cambiar nada. De ahí mi intención de indagar en las posibles causas que hacen a la exteriorización de esa necesidad.

A esta creatividad en el año 1962 se la denominaba creación. Y me parecía solemne, exclusiva para elegidos, por consiguiente discriminatoria, aunque tuviera que seguir usando este vocablo. Hoy, hasta me inclinaría a denominarla “creatividad”, por ser un factor específicamente dinámico.

Me refiero a esa fecha, porque entonces hice una muestra en la galería Pizarro y en el catálogo de presentación dije entre otras cosas: “…Posiblemente eso no se dé como una manifestación constante en mí, por lo que admito desde ya el hecho de desarrollar independientemente lo que mi necesidad expresiva imponga, sin límites, y más aún, creo que este estado no puede responder a un algo estable (me refería a lo establecido, aceptado) sin forzar la acción creativa…” (me negaba a usar la palabra “creadora”). Este fue mi primer intento de expresarme por el medio escrito.

Lo transcripto se refería a la intención que animaba a la obra presentada que denominé “Integralismo-BIO-COSMOS n° 1”. Esta era un objeto –palabra recién acuñada- que constaba de un cuadro adosado a una pared y del cual emergía una escultura. En la parte superior del cuadro había un dibujo que, al descender, se transformaba en pintura que después derivaba en relieves simulando materia orgánica. Luego, desde el ángulo inferior derecho, surgía un objeto que fue bautiza-

do con el nombre de “monstruo”, que en su trayectoria final se iba transformando en una pieza tecnológica que invitaba ópticamente a iniciar el recorrido.

Al margen del atisbo de lo que con el tiempo se llamó arte conceptual, me impulsaba la idea de fusionar técnicas –entonces obraban por separado– como también ligar lo intuitivo con lo racional, lo que equivalía a acercar el arte a la ciencia. Algo que curiosamente está íntimamente relacionado con la presente investigación, y tiene que ver también con mi necesidad de agrupar a las personas, como será más adelante.

Pero esta intención requería una comprobación, y ella se puso de manifiesto en una muestra de inventiva y plástica que se realizó en el año 1966 en la galería Vignes en la que intervinieron los artistas plásticos Enrique Barilari, Kenneth Kemble, Víctor Grippo y yo. En esa oportunidad desarrollé el texto de presentación, que si bien fue corregido por todos, conservó lo esencial. Este hacía referencia a lo que expresé en mi intento de ensayo (inédito) denominado “Integralismo individual”. En él manifestábamos:

Creemos que todo ser humano está dotado de cualidades semejantes y que la diferencia estriba en el grado de desarrollo de los medios expresivos (medios físicos y psíquicos). Constituimos este grupo de estudio con la intención de verificarlos.

Consideramos, por lo tanto, a la expresión creadora, con características multifacéticas.1

Aceptamos las deficiencias expresivas por falta de desarrollo de los medios (piscofísicos) como elementos fundamentales que conducen al proceso de desarrollo del individuo y no como lacras que deban ocultarse (canalización positiva de la creación).

No establecemos diferencias que puedan impedir el desarrollo de las necesidades expresivas de la creación en nuestros congéneres. Este esquema será una creación en la medida que modifique a otros; en caso contrario, sólo tendrá las características de una creación intrascendente pero valiosa, ya que modificó el esquema de los firmantes.2

Desde entonces lo único que modifiqué fue la palabra “creación” que hoy llamo “creatividad”. Sigo fiel al planteamiento general ya que pude comprobar que era demostrable.

Este intento de investigación pasó totalmente inadvertido; el esteticismo era el factor dominante. Los únicos críticos que se acercaron y nos apoyaron fueron

1

Con el transcurrir de los años, esto derivó en mis propuestas de “Creatividad integral” y “Multimágenes”.

2

Planteamiento embrionario de lo que hoy denomino: creatividad trascendente y cotidiana.

En 1968, cansado de tanta indiferencia, de tanto hipercompetir, me fui a París haciendo uso de la beca que logré en el premio de dibujo Georges Braque del año 1964. Era necesario alejarme de mi familia, de mis amigos, de mi trabajo, del ambiente plástico, del país. Una evidente huida que hablaba de un estado depresivo, producto de un sobreesfuerzo y de pocas gratificaciones. Estando allí y en esas condiciones, me hice una pregunta fundamental para mi tarea posterior: si la creatividad me llevó a tales extremos, ¿en qué consiste esa creatividad en función de la salud?

Entonces comprendí que estaba envuelto en una soledad propia del individualismo que cuestionaba, propia del hipercompetir que sólo me había dado la posibilidad de haber salido del anonimato. Tal es el costo de ese logro, pero junto con él, la posibilidad de usar mis vivencias para alertar a otros. De esto surge mi necesidad de conexión con lo social, que ya se había insinuado anteriormente.

Como consecuencia de estas reflexiones, tomé la determinación de retirarme de la plástica –cosa que hice desde 1968 hasta 1976- y regresé al páis sabiendo que mi tarea estaba aquí, a pesar de las dificultades.

A fines de 1969 el rector de la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes Prilidiano Pueyrredón, mi amigo Jorge Lezama, me comunicó que fui nombrado profesor de la cátedra de Dibujo de ese establecimiento. Ofrecimiento que acepté y allí intenté desarrollar lo que entendía por creatividad. En 1973 también me nombraron profesor del departamento de Artes Plásticas –Facultad de Humanidades- de la Universidad Nacional de San Juan. Mi tarea consistía en organizar lo que luego se denominó taller central, destinado a la investigación plástica. Idea que había sugerido con anterioridad. Tuve que renunciar a esa cátedra por no cumplir con lo pactado, que era viajar en avión, por razones de tiempo y de distancia.

Paralelamente a esto, fallece mi hija Graciela en un accidente de tránsito. Tenía 16 años. De esta circunstancia tan penosa surgieron los “ejercicios de convivencia” que hoy se usan en escuelas y talleres de artistas dedicados a la docencia. El momento exigía una solución. Había que reunir a la familia alrededor de un punto de interés para atenuar tanto dolor. Y este punto fue una hoja de papel en la cual, munidos de marcadores de colores, cada uno expresaba por medio de puntos, líneas, letras y números, lo que sentía. En estas circunstancias se podía hacer uso de la palabra, lo que a nivel de docencia eliminé por entender que podía dar origen a agresiones, lo mismo que ciertas simbologías. Las premisas básicas eran: a) Trabajar desde el centro hacia los extremos para evitar de verse obligado a establecer quién llegaba primero a ese centro. Tal criterio era compe-

titivo y, por consiguiente, motivo de conflicto. b) No interferir ningún trazo, lo que equivalía a respetar el esfuerzo realizado por uno y por el otro. c) Cuando alguno de los participantes se cansaba podía pedir la rotación del grupo. Esto equivalía a ceder el lugar de trabajo –territorio- y enfrentarse con lo hecho por otro. Algo que debía respetarse inexorablemente de acuerdo con la pauta establecida, aun cuando aprender a desposeer no resultaba fácil. Debo agregar que los marcadores debían tener un mismo espesor de punta para evitar trazos con características dominantes.

El objetivo fundamental de todo esto era: d) Trabajar siempre sobre la superficie blanca del papel hasta saturarla. e) Esa tarea indefectiblemente daba lugar a conversaciones por el hecho de encontrarse las personas cerca unas de otras. Resultaba una forma de comunicación y, por derivación de terapia atenuada, dado que tenían que pensar, haciendo, premisa que hoy uso en mi tarea docente. Al estar atentos al trabajo y a la vez hablar de sus penas, éstas disminuían de intensidad; se entremezclaban con otras ideas, con la diferencia que aportaban ese testimonio gratificante: el trabajo, mientras que las otras, no, ya que hurgaban en el dolor.

Alrededor de estos ejercicios se agrupó la familia compuesta por Dorita, mi esposa, Beatriz y Claudio, los hijos. Aún conservo esos testimonios. Digo esto porque ninguno de ellos tenía formación plástica y no obstante llegaron a expresar embrionariamente tal capacidad.

Con respecto a mí, me dediqué a inventar una máquina bastante compleja para cortar espuma sintética en forma cilíndrica, destinada a la fabricación de pequeños rodillos para pintar. Tardé tres meses para concluirla. El objetivo básico de esta tarea fue cambiar la “polaridad” de mis pensamientos haciendo algo que me sirviera para el futuro. Si bien esta máquina luego fue suplantada por otra más eficiente, logré que el tiempo transcurriera, y junto con él, que mi sufrimiento se atenuara.

Tuve necesidad de relatar esta anécdota dolorosa para poner de manifiesto que si se nos enseñara a cambiar esa “polaridad”, no tendrían por qué perdurar en nosotros, y por lapsos tan dilatados, conflictos que son propios de la vida. Esta, considero que es una de las tantas tareas de la creatividad.

Continuando con el relato de mi actividad docente, en el año 1974, a instancias de Roberto Duarte, entonces director de Enseñanza Artística dependiente de la Secretaría de Cultura de la provincia de Buenos Aires, fui nombrado profesor de dibujo de una escuela de la que tuve la satisfacción de ser uno de los docentes fundadores: la Escuela de Arte de Luján (Buenos Aires). Estuve en ella hasta el año 1976, año en que quedé cesante. La resultante final de seis años dedicados a la docencia y difusión de la creatividad fueron dos cesantías y una renuncia. Esto me llevó a entender que mi intención tendía a abarcar más de lo que supo-

nía. Como consecuencia de estas vivencias, también me di cuenta del temor que produce la autoindagación, de lo cual no hay que extrañarse, ya que si existe un enemigo al cual tememos, es precisamente el hecho de ser enemigo de sí mismo. Y la autoindagación puede conducir a darnos cuenta de ello.

Pero todo lo dicho no era tan simple. Exigía comprobaciones. En caso contrario, podía correr el riesgo de ser una hipótesis ingeniosamente urdida y al servicio de mi satisfacción personal. Por consiguiente si mi intención era específicamente social, debía elaborar los recaudos para no incurrir en ese error.

No quedándome más alternativas en la docencia oficial, regresé a la plástica en el año 1976, y desde entonces hasta 1983, traté de difundir mis ideas por medio de textos incluidos en los catálogos de presentación de mis muestras.