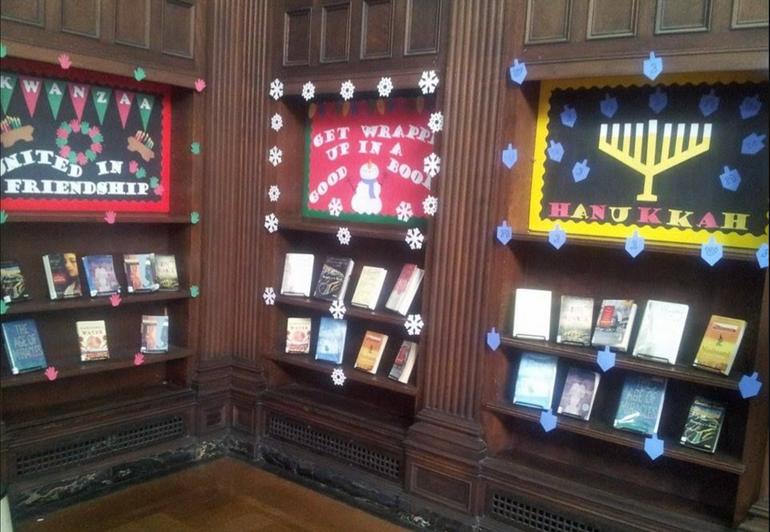

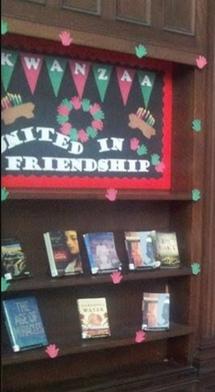

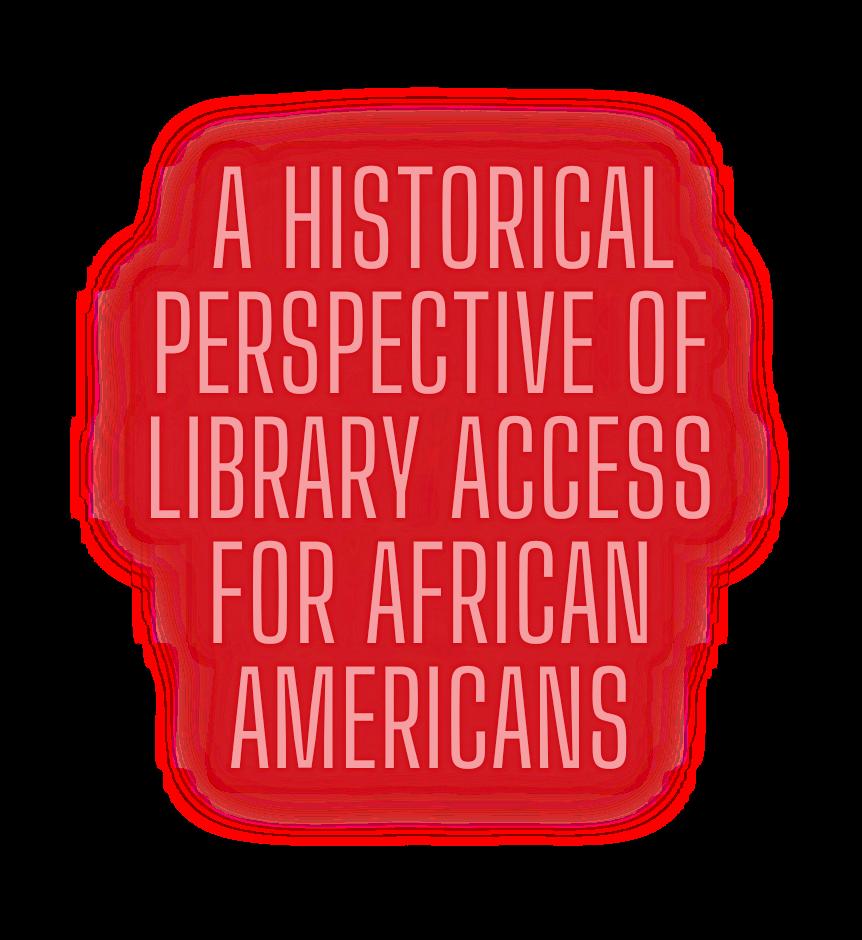

For almost thirty years, the Multicultural Music Group, Inc. (MMG) has been a bastion for diverse scholarship and research, in addition to symphonic music. Our early Encounters presentations all featured a multiracial panel of scholars talking about important socio-political issues from around the world. In line with this year's theme of Afro-Descendants, we honor those African Americans who sacrificed everything for the right to read and access information at public libraries across the United States.

At the end of the 18th Century, those in power treated lack of education as the key to the continued subordination of enslaved people. According to Pamela Spence Richards in "Library Services and the African Intelligentsia before 1960," 90% of the black population in the United States could not read by the year 1900 (1). Though the endeavor to disempower African Americans was nationwide, a few northern states did pass laws to address pervasive illiteracy.

An 1803 New York State law required that all enslaved people be taught to read the Bible by the age of 18 or be set free. As a result, Sunday, also known as Sabbath, schools became very popular (2). The New York Female Union Society to Promote Sabbath Schools even established a lending library in 1823. Nevertheless, black people living in other northern cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Boston were still prohibited from using public libraries.

“Colored Scholars Excluded from Schools,” woodcut from American Anti-Slavery Almanac, for 1839 (New York, 1838).

The image to the left is from a publication called "The American Anti-Slavery Almanac" that was published in 1839 The caption quotes a reverend from the Southern Religious Telegraph who stated, "If the free colored people were generally taught to read, it might be an inducement to them to remain in this country" (3) In other words, the ability to read is directly connected to political participation and belonging.

The legal foundation for segregated libraries was established by the landmark 1896 Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson. Most people may not know that, prior to the 1896, libraries were not segregated; African Americans were simply excluded from libraries altogether (2). Even if Plessy v. Ferguson enshrined unequal separation into federal law, the Supreme Court's decision inadvertently allowed black people access to libraries for the first time in American history.

"

Plessy v. Ferguson inadvertently allowed black people access to libraries for the first time in American History."

Even after Plessy v. Ferguson, many African Americans received only bookmobile service; though the vast majority got no library service at all. Black people who demanded service at public libraries were charged with disturbing the peace, and one such case, Brown v. Louisiana, went all the way to the Supreme Court in 1966, when the court decided that the rules for using public facilities must be enforced in a "reasonably nondiscriminatory manner, equally applicable to all" (4).

According to Maurice Wheeler and Debbie Johnson-Houston's "A Brief History of Library Service to African Americans" (2004), a common practice was to either close the library entirely rather than provide service to black people, or to remove all of the furniture so people were encouraged to check out books and leave immediately (2).

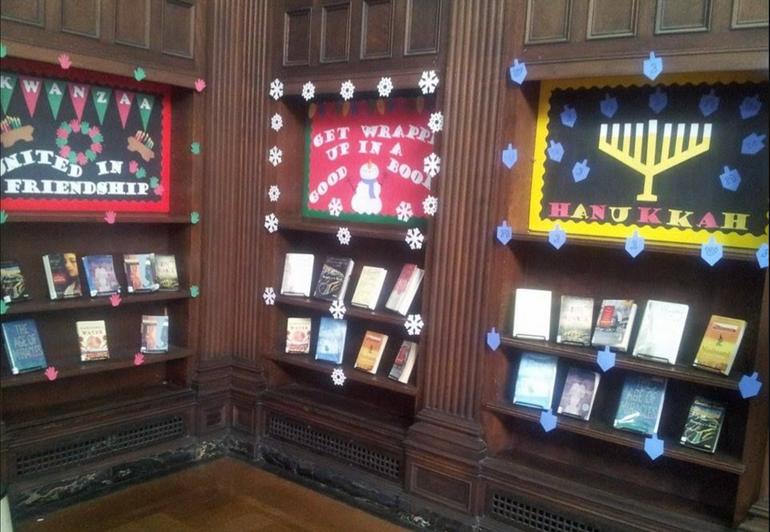

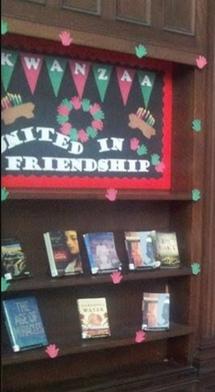

The image above links to a description of the children's book, "Richard Wright and the Library Card" (1997) by William Miller

Enormous social change has taken place at libraries, sometimes with violent consequences. African Americans were beaten, arrested, and often lost their jobs attempting to register for library cards (2). Many Americans may not know that the library card is one of the most valid identifying documents in the United States, besides passports and state licenses, that prove legitimate residency.

"African Americans were beaten, arrested, and often lost their jobs attempting to register for library cards."

Though MMG has hosted several panels of diverse scholars, we aim to take our commitment to empowering multicultural intellectual growth a step further in the next two years. We currently applying for a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to create a mechanism of defense against discrimination in the areas of health, education, economics, law, and technology. Addressing global social justice topics in our Encounters presentations was only the beginning of MMG's journey to identify and strategize solutions to the most pressing issues of our time. The Multicultural Music Group strives to change the lived experience of disempowered peoples, not to pontificate about problems, even if their resolution results in waning investment in new publications.

Richards, Pamela Spence. “Library Services and the African-American Intelligentsia before 1960.” Libraries & Culture33, no. 1 (1998): 91–97. http://www jstor org/stable/25548602

Wheeler, Maurice, Debbie Johnson-Houston, and Billie E Walker “A Brief History of Library Service to African Americans ” American Libraries 35, no 2 (2004): 42–45 http://www.jstor.org/stable/25649066.

American Anti-Slavery Society, American Anti-Slavery Almanac, for 1839 New York: S. W. Benedict, 1839, page 13 Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library http://dlxs library cornell edu/m/mayantislavery Fortas, Abe, and Supreme Court Of The United States U S Reports: Brown v Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131. 1965. Periodical. https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep383131/.