SheShouldHaveBeen GivenHerFlowers: QLazzarus

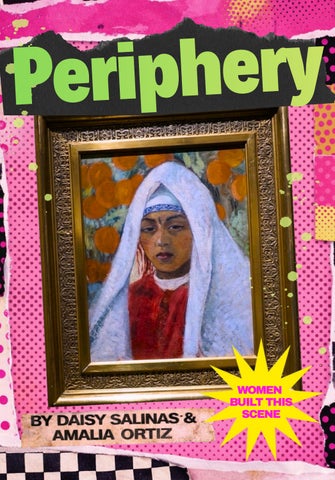

ByDaisySalinas ByDaisySalinas

Diane Luckey sh mystery, or a trivia question passed around late-night music forums. She should be a cornerstone and a name spoken with the same reverence as the architects of alternative and punk history. Instead, she became another immensely talented Black woman the music industry failed and then conveniently forgot. As Q Lazzarus, she carried a voice that was haunting, confrontational, tender, and defiant all at once. It was a voice that refused to be polite, refused to be easily categorized, and refused to make itself smaller.

The music industry did not know what to do with her because it has never known what to do with Black women who do not conform. Labels told her they could not market a Black woman singing rock, as if whiteness were a requirement and Blackness a liability. And it cannot be ignored that fatphobia played a role too. As a plus-size Black woman, Diane existed outside the narrow beauty standards the industry demands, and that kind of cruelty shapes who gets invested in. This hypocrisy is especially stark given the founder of rock ’ n ’ roll was a plus-size Black woman: Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Yet the same oppressive logic continues to relegate Black alternative artists to the margins, pressuring them to dilute their sound or vanish altogether. Q Lazzarus did neither. She kept making the music anyway.

In the mid-1980s, while trying to survive in New York City, Diane Luckey was driving a taxi. Not as a quirky backstory, but because Black women artists have always had to work twice as hard to get half as far. When director Jonathan Demme hailed her cab, she took the opportunity to play him her demo. He heard what the industry refused to hear, a voice that was otherworldly and unforgettable. That chance meeting led to her music appearing in his films, most famously “Goodbye Horses,” which later became a cult classic through The Silence of the Lambs.

But cult status is not the same as equity. A song becoming iconic does not mean the artist behind it was supported. Q Lazzarus’s voice became part of popular culture, but she did not benefit from that success. Sure, she was paid for her songs being in Demme’s movies, but then she never received royalties for her music. The industry took what it wanted and left her to navigate the aftermath alone.

What followed was not disappearance but survival. Diane moved through many worlds, not just music. She cared deeply for her family and was known for her humor, her storytelling, and her love of fashion, food, and travel. She worked grueling jobs as a bus driver, coach operator, and car service driver while quietly carrying a legacy people around her never fully knew. During her struggles with substance use, she also turned to sex work to survive and support her addiction. She battled homelessness, incarceration, and depression, but she eventually got sober and rebuilt her life. These were not just detours from her artistry. They were the conditions forced upon her by systems that repeatedly fail talented Black women.

In August 2019, her story came full circle. Filmmaker Eva Aridjis had been searching for Q Lazzarus for years when she was picked up by a car service driver in New York City. During the ride, Aridjis asked if she knew who Q Lazzarus was. Diane said yes, but at first she did not say more. She had spent decades being erased and dismissed. Then something shifted. Much like the night she played her demo for Jonathan Demme years earlier, Diane chose truth. She told her, “I am Q Lazzarus.” That moment became the beginning of Aridjis’ documentary Goodbye Horses: The Many Lives of Q Lazzarus which finally gave Diane the chance to tell her story in her own words.

During the filming of the documentary, she reconnected with music and began imagining a comeback that was intentional and on her own terms. For the first time, it seemed like the world might finally be ready to listen. She should have been celebrated then. She should have been supported then. She should have received her flowers while she was still here to hold them.

After being forced to postpone her comeback concert due to the pandemic, Diane Luckey heartbreakingly died in 2022 at the age of 61 after breaking her leg and developing sepsis. Her son, James Luckey-Lange, said that her death was the result of medical neglect rooted in racism. Her pain and condition were not taken seriously a familiar pattern in which Black women ’ s suffering is minimized until it becomes fatal. His words echo a well-documented reality: Black women are routinely dismissed and undertreated by a medical system that does not value their lives equally. Even in death, Diane Luckey was failed by the very institutions we are told are supposed to protect her.

Her story is devastating because it is familiar. Black alternative artists are repeatedly invited in only when their work can be extracted or aestheticized, then discarded when they ask for care, safety, or sustainability. Their contributions are celebrated without celebrating them.

Diane deserved a career that matched her talent, a music industry that believed in her vision, and a healthcare system that treated her life as precious. Honoring Q Lazzarus means refusing to let this pattern continue. It means naming the racism and sexism that shaped her path and demanding better for the Black women creating outside the boxes today.

Q Lazzarus did not disappear—she was erased by an industry and by institutions that profit from Black creativity while neglecting Black lives. To remember her now is not an act of sentimentality. It is an act of accountability. It demands that we confront how many gifted, funny, caring, brilliant Black women are silenced not by lack of talent, but by neglect, racism, and indifference. We write Diane Luckey back into the record to make sure her story, and the stories of Black alternative artists like her, are never pushed to the margins again.

If you want to support Diane Luckey’s legacy and her family, you can donate directly to her son via PayPal at @realqlazzarus. You can also support her music by purchasing Goodbye Horses: The Many Lives of Q Lazzarus (Music From the Motion Picture) at www.sacredbonesrecords.com, and watch the documentary Goodbye Horses: The Many Lives of Q Lazzarus on Amazon. 16

ByAmaliaOrtiz ByAmaliaOrtiz

I received a ph lear, it took me a while to figure out it was a butt-dial. A close friend of mine was brainstorming with a second male voice, listing people to interview for the Chicano music documentary he had been working on for some time. After rattling off a list of men ’ s names he paused and contemplated, “And I gotta get some… some mujeres.” After a pause, “I mean, I hate to say that I have to, you know. But I do…” He chuckled. “I do. I think the… [more laughter] the problem is thinking… but who would that be? There’s some, like, sort of peripheral players… you know, but I'm not sure who else that will be necessarily...” The conversation then switched topics, but my thoughts couldn’t.

I was shaken. It wasn’t only the words “I gotta get some… some mujeres. I mean, I hate to say that I have to, you know…” It was also the laughter. It wasn’t evil laughter, but something more insidious: the kind of guilty laughter of someone who knows they just said something fucked up. It was what I imagine uncomfortable laughter sounds like after locker room talk, laughter by someone who disagrees, but doesn’t have the backbone to shut it down. The butt-dial was from a man of color and a homie I have known for decades: someone I consider an ally. The recording cut me.

When I get mad

And I get pissed I grab my pen

And I write out a list Of all the people That won't be missed You've made my shitlist.

As a huge live music fan and a staunch feminist, I felt an obligation to respond. But I first heard the butt-dial message right before boarding an international flight to Spain. I was traveling to a conference, and my husband and I wanted to make the most of this opportunity to scratch a visit to Morocco off of our bucket list. So, upon landing in Madrid, we immediately journeyed south to Tarifa by train and bus. 24 hours later, we found ourselves walking the streets of the Tangiers medina. In the Dar Niaba Museum, the butt-dial recording came to mind as I walked through hall after hall of antique paintings and more modern photographs of men. Sultans and kings. Men of power and privilege. “Where are the mujeres?” I wondered. Then, I found a smaller room filled with paintings of women, most of them at work.

“Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard / But I think ‘oh bondage, up yours!”

On the streets of present-day Tangiers, women have the choice between various levels of modesty. Some wear head coverings or full body coverings and some don’t. But in the museum paintings, the women were covered from head to toe while drawing water and doing laundry at a river or at a marketplace, their sails of fabric blanketed them, indistinguishable from one another. In one of the few

paintings where their heads were uncovered, women polished pots and candlesticks happily. In a portrait of a woman of privilege, her eyes cut through time staring out through a veil. In yet another, a brown-faced female met my gaze, her head but not face covered, and she looked pissed.

“Such a classic girl…”

The combination of the art and the butt-dial sent me to a dark place. I posted the images of the women on Instagram with angry descriptions and defensive hashtags, “You should smile more. #notperipheralplayers #youcamefromawoman #iseeyoukween” “These walls need more men. ” I captioned another. I thought of the historic documentation of women. My friend’s words are true. He doesn’t have to include more women. No one is forcing him. But he should. I thought of centuries of patriarchal gate-keepers controlling female lives, narratives, and how history perceives them.

“I’m gonna get get get get rid of that girl / I’m gonna get get get get rid of that girl / I’m gonna get get get get rid of that girl tonight…”

My mind jumped again to the Beat Generation, specifically the female Beats and how their stories have never been regarded as highly as their male contemporaries. I pictured Joyce Johnson in famous photographs, standing in the shadow out of focus behind Jack Kerouac gleaming under the neon “BAR” light outside of Kettle of Fish in NYC. The camera clearly focused on him, blurring the reality that she was there.

“Such a classic girl…”

In my early thirties, I won a literary award. One of the judges, a nationally recognized award winning writer in his fifties, requested to meet me to personally congratulate me. At that first meeting with him, he offered me part-time work helping him with an anthology of Texas-Mexican literature he was editing. I’d have to email and collect signed releases from all the authors and other low-level administrative duties, he explained. And of course, he intended to include my poetry in the collection. From this first conversation on, he became a mentor, and over the next months, he introduced me to a larger literary world, inviting me to share my writing in highprofile reading opportunities and introducing me to writers at a national level of success. Over the next year, he invited me to sit in on his graduate-level literature classes and to share the bill with him on book tour readings requiring us to travel out of state together. At some point, our relationship had become romantic.

The relationship lasted about a year and a half and ended badly when his mentorship turned overbearing and controlling. Convinced I would cheat on him with someone younger, he isolated me from my friends, discouraging me from spending time with anyone other than him. He often ridiculed me in public, referring to me as his “teenage” partner, further exploiting the power imbalance between us. In the end, there was no calming his jealousy and paranoia, so I broke up with him. Word got back to me through mutual friends that he was now describing me as a crazy ex, using the same word, “ crazy, ” that he had used to denigrate all his former partners in his descriptions of them to me.

“Typical girls get upset too quickly / Typical girls can't control themselves…”

When the Tex-Mex lit anthology was released years later, it was no surprise to me that my poetry was removed from the manuscript, but one reviewer for a newspaper directly pointed out the absence of my work. This is just one example of how I was painted out of a specific his-tory. I won’t do a deep dive into my romantic relationship with a filmmaker who filmed my spoken word performance for his documentary on Tejana poets, then scrapped the footage after that relationship ended.

Oh, look at my face

My name is ‘Might-Have-Been’

My name is ‘Never Was’

My name's forgotten

Ironically, the most profound example of historical omission I ever witnessed came on a trip with my mentor in 2002. I invited him to my high-profile gig, a live taping of an episode of Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry in New York City. After my performance, I tagged along to an impromptu meeting with one of his literary friends, Hettie Jones.

I’m embarrassed of my younger self. At that time, I had never heard of her. On the taxi ride to her apartment in the East Village, my mentor caught me up with a CliffsNotes version. Ms. Jones was an author of poetry, fiction and nonfiction. Her most notable work, How I became Hettie Jones: A Memoir, documented her life in 1950s and 60s Manhattan when she worked at the heart of the underground publishing scene with her husband LeRoi Jones (who later

divorced her and became Amiri Baraka). They attracted writers, jazz musicians, and artists, all of them icons of the Beat Generation. Including Hettie Jones herself.

After climbing the narrow and uneven steps to her modest brick apartment, I found myself sitting in her living room. The original hardwood floor planks were noticeably warped and slanted, the bare brick walls were chipped and crudely patched in places, but the home felt lived in and loved, neat and cozy like a modern bohemian hobbit house.

I froze in my seat, an awkward fly on the wall as she recounted to my mentor tales of Allen Ginsberg, Thelonious Monk, Billie Holiday, James Baldwin. At one point, Hettie turned in my direction and pointed at me. “Jack Kerouac sat right there.” Her eyes saw through me to his ghost still in the room with us.

Ms. Jones was animated and intense about these memories, because they were under attack. She explained how gentrification was taking over the Bowery, and her home was listed to be the next casualty. Developers had their eyes on the building, and there was a good chance that she would be forced out. Then, her energy switched to anger. There was one way she could save the building, but she wasn’t sure she could stomach it. She had begun researching how to procure a historical marker for the building, she said. Her voice rose to shouting at this point. And I am recounting this story to the closest that my memory allows, but she said something like she would be damned if she had to walk by a plaque every day that read, “Amiri Baraka lived here.” Why wasn’t it enough that Hettie Jones raised two daughters here?

The experience forever changed how I viewed the Beats. Their popularity always seems to be championed by men who never seem to ask, “Where are the mujeres?”

“I’m gonna get get get get rid of that girl / I’m gonna get get get get rid of that girl / I’m gonna get get get get rid of that girl tonight.”

Who is privileged and who is omitted through hegemonic history-making? This question is central to the book ¡Chicana Power!: Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement in which Maylei Blackwell used oral histories to challenge traditional history modes which favor those in power. The book chronicles Las Hijas de Cuauhtémoc, the Chicana feminist newspaper and student movement which emerged from the late 60s through 80s to address “the repudiation of women ’ s leadership and the marginalization of women ’ s issues in the Chicano student movement.” Chicana organizers began to recognize their struggles were not only with issues of alienation from the dominant culture due to race and cultural differences, but also from gender and sexuality issues from within the Chicano movement itself.

“Survival is the game / Can't stop us now, it's all in vain…”

It follows then that any modern Chicano history that fails to include Chicana perspectives is falling into this same inherently sexist trap. Blackwell flipped the script on Chicanx history, playing the role of cultural DJ remixing female voices through oral histories into the male dominated narrative of the movimiento:

When I began this research in 1991, I embarked on a question to turn up the volume on the stories of gender and sexuality that have been dubbed out of the Chicano historical record. Through this journey I have found that being an oral historian is like being a DJ. As one digs through the old crates of records (historical archives) to find missing stories, the songs (narrative grooves, if you will) must be selected and their elements remixed to produce new meanings. Oral historians spin the historical record by sampling new voices and cutting and mixing the established sounds to allow listeners to hear something different, even in grooves they thought they knew (p. 37-38).

Hey!

Miss Lady DJ (Lady DJ)

Miss Lady DJ (Lady DJ)

Miss Lady DJ (Lady DJ)

Hey! Hey!

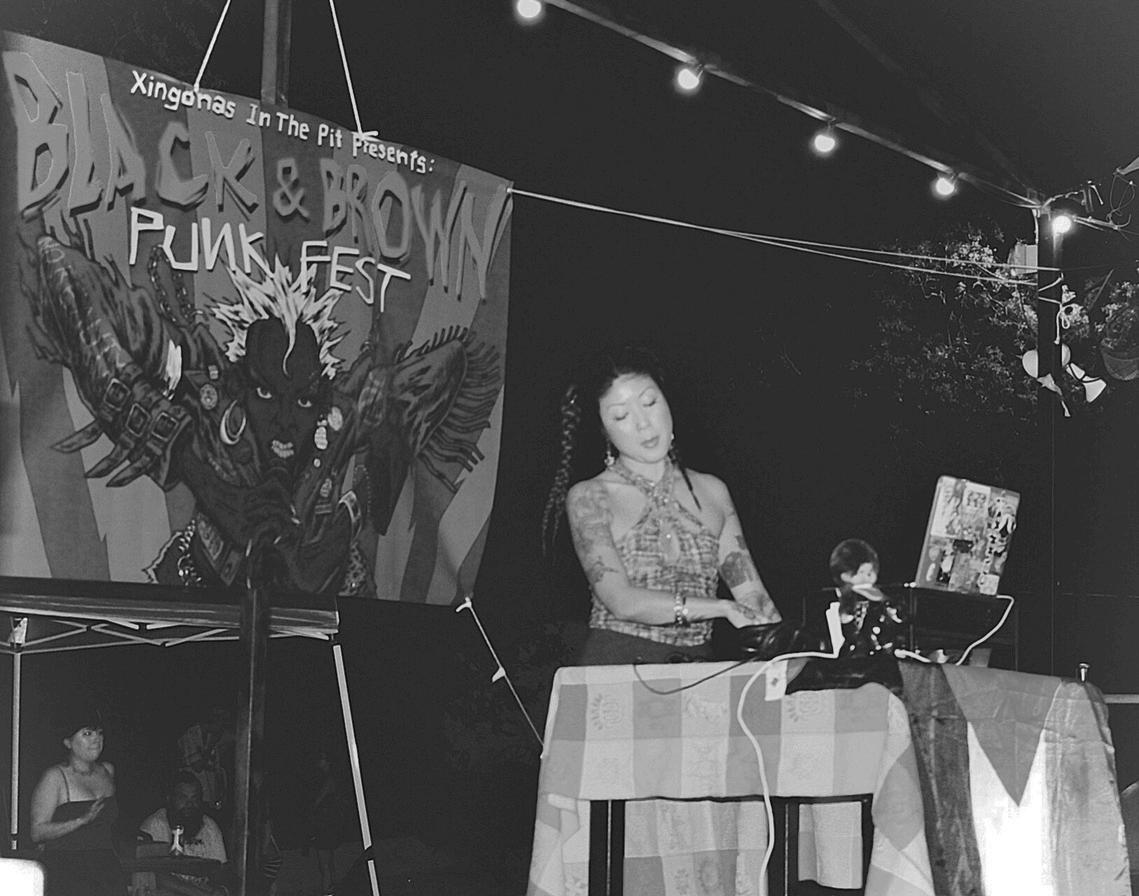

Once back from my trip to Spain, I knew I had to talk to my friend about his documentary. The easiest thing to do would be to say nothing, but the butt dial wasn’t sent to just anyone. It landed in my lap, of all people. I had to tell him that it's true, it’s his doc and he can do whatever he wants, but ignoring the mujeres would be a big mistake. I wanted to tell him about my testimonio that was published in “Maximum Rocknroll” in a larger collection of pieces about the Black and Brown Punk Fest organized by a collective called Xingonas in the Pit. In the article, I described how in my early days of crowd surfing, I was regularly sexually assaulted, only we didn’t call it that in those days. As I was passed over head by countless strangers, men would inevitably grab my breasts, squeeze my ass, or grab and one time even punch me between my legs.

“Too many creeps, too many creeps / Too many creeps, too many creeps ”

I wanted my friend to consider how live music scenes are usually supported by bars which are not always safe or supportive to the marginalized in the ways we need them to be. Collectives like Xingonas in the Pit, a “San Antonio-based decolonial feminist punk collective,” celebrate artists of color, but also understand the challenges of marginalized folks and aim to create “inclusive spaces for punks and other alternative people of color.”

I've been crawling up so long on your stairway to heaven. And now I no longer believe that I wanna get in. And will there always be concerts where women are

raped?

Watch me make up my mind instead of my face. The number one must have is that we are safe.

The same week I sat down to write this essay, Casey Niccoli published an article in HuffPost defending her legacy as a creative, collaborative force with Jane’s Addiction during the band's formative years. She detailed how she riffed with frontman Perry Ferrell on the band’s name, styled him, taught him how to play guitar, took photos and co-created art which appeared on their first two albums, which were both named by her. Niccoli also directed multiple projects including the award-winning music video for “Been Caught Stealing,” which catapulted the band into a national MTV audience.

“Such a classic girl, gives her man great ideas/ And hears you tell your friends, ‘Hey man, why don't you listen to my great idea!’”

Bassist Eric Avery posted a picture on Instagram in May 2024 of the sculpture she co-created with Ferrall for the cover of the 1990 album Ritual De Lo Habitual. “An amazing historical artifact was unearthed today. #janesaddiction” he captioned the post without mention of its co-creator Niccoli. Internet fans protested the omission and a day later Niccoli went to instagram with her thoughts on the matter, which would evolve into the HuffPost essay:

I thought I would celebrate me today, because my name doesn’t get mentioned much anymore in reference to my work for JA. …Perry and I haven’t spoken since probably 1999. Somewhere along the way, without any communication, Perry decided that I was unworthy of any credit or respect. He slowly stopped mentioning my name when interviewing about the band’s history, and the artwork. What he once referred to as “ we ” became “I”.

Her story is riveting and gut wrenching. The article proves her capable of writing an autobiography or creating her own documentary. Whatever the case, herstory needs to be told and heard.

“Such a classic girl…”

When I hear about a lack of representation of women in a music scene, my first reaction is to wonder how welcome women are in the first place. How many female and marginalized performers have been pushed out by a boys club of promoters, club owners, or a male-dominated musicican

community? Whose stories are left out due to bad blood or breakups? What other factors keep marginalized folx out? Patriarchal industry gatekeepers? Archaic divisions of labor that come to a head when women have children? I want to ask any man standing center stage what women have sacrificed for them to be there. Who raised the babies? Who fed them and cleaned the house? Who sacrificed their own artistic aspirations to perform the labor necessary for paying rent? What role do drugs and alcohol play in a community which can only exacerbate the threat of sexual assault, sexual harrassment, unplanned pregnancy, and domestic violence? “Too many creeps, too many creeps / Too many creeps, too many creeps… ”

It took me about a month after my return from my trip abroad before I was able to meet with my homie calmly and tell him about his butt-dial. I handed him a list of about 13 people I think he could interview for his Chicano music documentary. My list included queer rapper Chris Conde, festival and rock show producer Faith Radle, and filmmaker Jim Mendiola who is known for his directing videos and films championing female rockers. Rebel Mariposa, the former owner of the now closed lgbtq+ live music and gay cultural hub La Botanica should be interviewed, along with the creator of Xingonas in the Pit, Daisy Salinas, who frequently moved all the furniture out of her house to create a safe and inclusive space for the local punk houseparties. The list goes on: Son Queers, Alyson Alonzo, Suzy Bravo and the Soul Review, Speeder, Jackie on Acid (now called Saving Jackie), DJ Despeinada, Ceiba Ili, and the Indigenecias.

just another book about the women in rock just another book about the women in rock just another book about the women in rock just another book about the women in rock

My list is not comprehensive by any means. We all have blind spots that we can either acknowledge or ignore in our work. “Your blind spot is my whole reality,” I told him. I didn't mention to him that this is a line from a song I had just written inspired by these thoughts. I also didn’t mention that I am writing this essay.

He heard me out and took it like a true homie. He apologized for the hurt his words caused. We talked about the list and he agreed that he needs to interview some of the names I offered him. “Such a classic girl, gives her man great ideas / And hears you tell your friends, ‘Hey man, why don't you listen to my great idea!’"

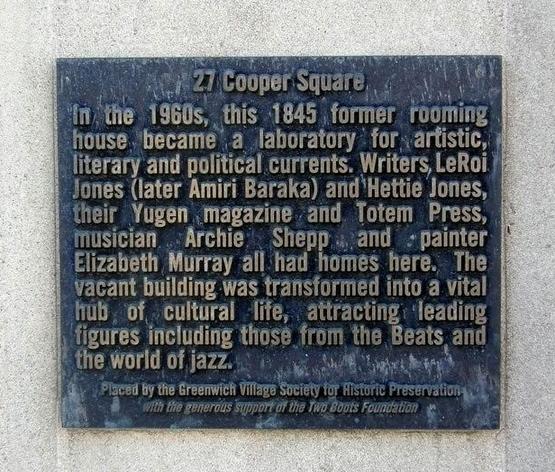

Hettie Jones ended up fighting developers until a deal was struck for them to construct a 23-story hotel around her building. The Cooper Square Hotel (now The Standard, East Village) opened in 2008, and eventually in 2017, a historic marker did go up. It reads:

In the 1960s, this 1845 former rooming house became the laboratory for artistic, literary and political currents. Writers LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) and Hettie Jones, their Yugen magazine and Totem Press, musician Archie Shepp and painter Elizabeth Murray all had homes here. The vacant building was transformed into a vital hub of cultural life, attracting leading figures including those from the Beats and the world of jazz.

It doesn’t mention, but should be noted that Hetti Jones raised two daughters there. “Such a classic girl… /Such a classic girl… / You know for us these are the days.”

References: https://www.instagram.com/p/C7DUgqQrVS6/ https://www.instagram.com/p/C7GORCANfh1/? utm source=ig web copy link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA== https://socialjusticechicanoactivism.wordpress.com/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/chicana power.pdf https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/creative-force-behind-one-biggest125908936.html https://www.beatdom.com/women-of-the-beat-generation/ https://medium.com/@womenofthebeatgeneration /introduction-to-thewomen-of-the-beat-generation-e9ff38a454a5 https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/28/nyregion/thecity/28hote.html https://www.standardhotels.com/culture/hettie-jones-east-village-interview https://pitchfork.com/features/lists-and-guides/9923-the-story-of-feministp k i h

u

Fertile La Toyah Jackson

Black punk vocalist and performance artist active in underground DIY scenes.

Flora Lucini (MAAFA, The 1865)

Brazilian-born Black punk musician & fest organizer who channels politically rooted “Afro-Progressive Hardcore.”

Fanny Millington & Jean Millington (Fanny)

Filipina-American sisters in one of the first all-women rock bands.

Gaye Advert (The Adverts)

British punk bassist who’s basslines helped define early UK punk.

Irma Cecilia Loera (Cecilia ±)

Early Descendents vocalist erased from official band history - later fronted goth band Angel of the Odd

Jenny Lens

Without her photographs, large parts of the early L.A. punk scene (Black Flag, X, Germs, The Bags) would barely exist visually.

Jessy Bulbo (Las Ultrasónicas)

Mexican punk musician, producer, and writer whose work helped define feminist punk and garage rock in Mexico.

Pauline Black (The Selecter)

Key figure in 2 Tone ska-punk, merging anti-racist politics with punk energy.

Penelope Houston (The Avengers)

Political punk frontwoman central to the San Francisco punk scene

Poison Ivy (The Cramps)

Guitarist, songwriter, and archivist whose musical vision was central to The Cramps’ punk-garage sound and longevity, often overshadowed by her male bandmate.

Poly Styrene (X-Ray Spex)

Black British punk visionary whose influence is often sidelined in favor of white contemporaries.

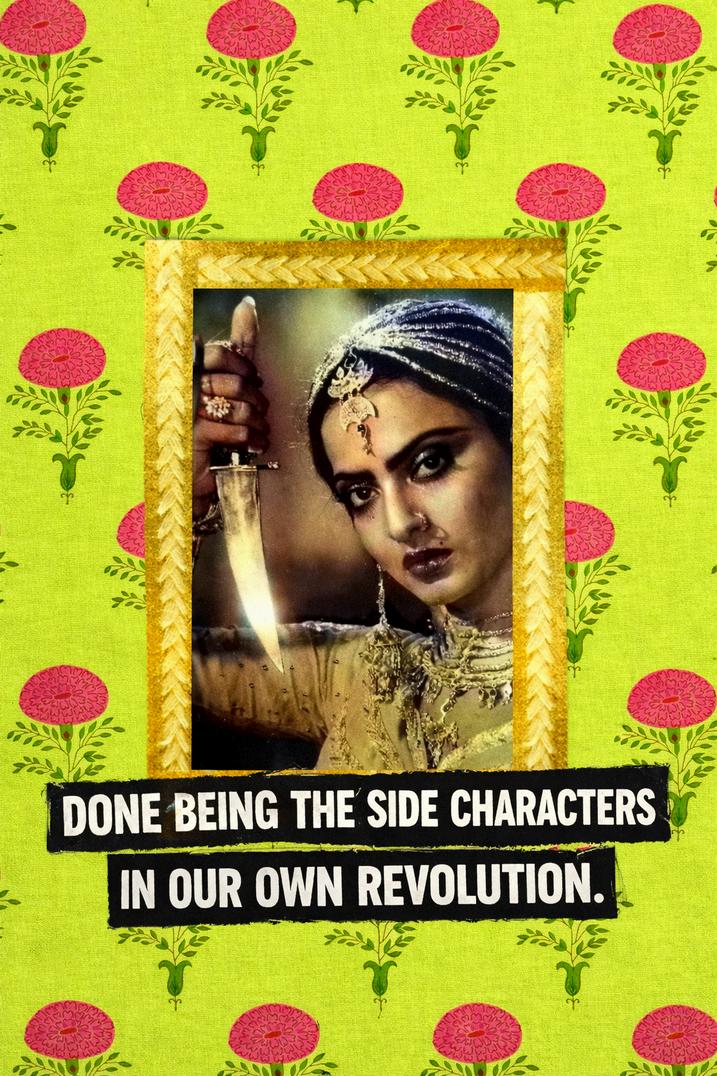

Q Lazzarus (Diane Luckey)

Black alternative artist whose work crossed punk, new wave, and post-punk spaces

Raeghan Buchanan (The Secret History of Black Punk)

Comic writer and visual artist preserving Black punk narratives long erased from mainstream histories.

Susana “Susy Riot” Sepulveda (Las Sangronas y El Cabron, Punk Con)

Punk vocalist, scholar, and co-founder of Punk Con.

Suzi Quatro (The Pleasure Seekers)

Proto-punk rocker whose influence on punk bassists and performers is often under-acknowledged

Suzy Exposito (Suzy X)

Singer (Shady Hawkins), zinester (Chiflada), and music journalist.

Teresa Covarrubias (The Brat)

East L A punk bassist and organizer central to Chicanx punk’s emergence.

Tina Bell (Bam Bam)

Seattle punk pioneer whose work predates and directly influences grunge.

Tina Weymouth (Talking Heads)

Bassist whose rhythmic innovations shaped post-punk and new wave.

Wendy Yao, Amy Yao, Emily Ryan (Emily’s Sassy Lime)

First-generation Asian American riot grrrl trio who challenged the movement’s whiteness through raw, lo-fi DIY punk made on their own terms

ByDaisySalinas ByDaisySalinas

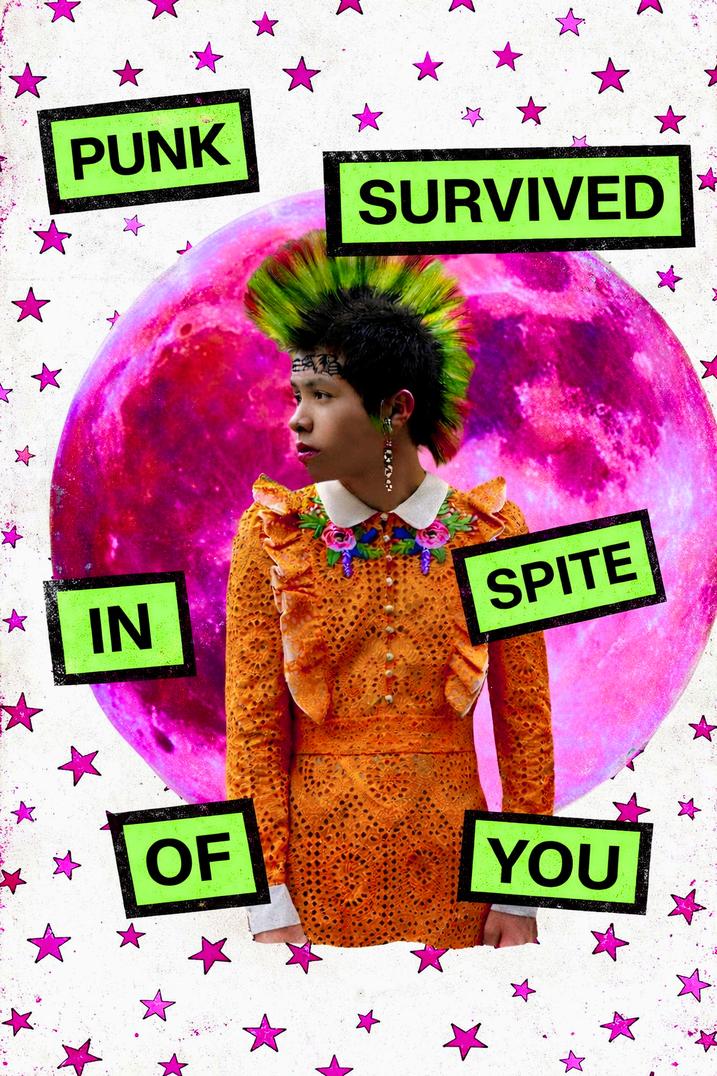

"We're witnessing the era of a new creative punk renaissance led by QTBIPOC investing in the collective holistic well-being of our people in ways that offer alternatives to the dependency on the systems that kill us. Which to me is vital in the longevity of our movements; We really are 'ALL we got.'"

Flora-Morena Ferreira Lucini (MAAFA, The

1865)

After four months of planning, Black & Brown Punk Fest 2025 (Saturday, October 18th at San Antonio’s Tandem) was a huge success and it’s taken me a minute to really sit with what this moment meant. Because Black & Brown Punk Fest isn’t just a show. It’s a sanctuary. And it was built and led by women and femmes of color, onstage, behind the scenes, and in every invisible detail that made the night possible.

Punk gave me freedom growing up in Nashville, but it also pushed me out. Sexism and racism nearly drove me away from the scene I loved and helped create. I wrote about that experience in Muchacha Fanzine’ s “Decolonize Punk” issue (page 45). The message was clear: You can be here, but you can’t take up space. You can exist, but you better stay grateful and quiet. But punk taught me something else too. If the world won’t make space for you, you build your own.

That exclusion pushed me to do the punkest thing I could think of: build my own scene. Since 2017, the feminist punk collective I started, Xingonas in the Pit, has been doing exactly that. In 2018 we launched Texas’s first Black & Brown Punk Fest, which returned in 2019. We’ve also organized additional fests, shows, workshops, the plus-size clothes swap Thick Bitch, a Covid Conscious Craft Club, and more. After a pandemic pause and some burnout, an incredible team of volunteers across Texas helped us bring the fest back stronger and more intentional than ever.

The crew (pictured above) was Jazzmin, Crystal, Nilse, Alma, Denise, Amalia, Monica, Geo, Des, Sabrina, plus me. Folks don’t always see the hundreds of invisible hours behind a DIY festival. You spot a flyer and decide whether to come, but it doesn’t happen out of nowhere. It happens because people like us make it happen through dozens of emails, meetings, grant applications, artist bookings, travel arrangements, rider fulfillment, production logistics, vendor coordination, marketing, flyering, volunteer recruitment, training, and site

(photo by @pray.4rain)

setup. It’s unpaid labor. It’s emotional labor. It’s physical labor. It’s the kind of work capitalism wants to erase because it can’t profit off it. But we do it anyway. By the people, for the people.

BBPF’s success was collective care in motion. Our sound team (shoutout Tequila Productions, our production manager Monica, stage manager Des, and stagehand Nilse) made every set land. Flyers, photos, and videos (thank you @juan.y.diego, Bosh, Geo, and Sabrina) captured the night’s intensity and tenderness. Vendors, from Gorda Bakes’ perfect cake to zine creators and artists, made the space feel abundant and sustaining

And I need to say this plainly: Xingonas in the Pit’s Safer Space Crew is not a “nice addition.” It’s the backbone. It’s the point. A safer space crew isn’t just there for vibes. We’re there because people are harmed in scenes that refuse accountability. We’re there because too many punk spaces still treat misogyny, racism, transphobia,

Cake by @gordabakes, flyer by @juan.y.diego (photo by @__kreatura)

fatphobia, and ableism like background noise, like it’s “just how it is.” No. That’s not punk. That’s bigotry playing dress up in a punk costume. Safer Space Crew is how we protect each other when the world won’t. Shoutout to the incredible Shawna Potter (War on Women) for the training!

This work is hard, and sustainability matters if I want to keep doing it. I’m lucky to have such a badass team to prevent burnout. Watching women, queer, trans, and BIPOC people of all ages dance, mosh, and rage together makes every bit of labor worth it. This wasn’t just another show. It was a declaration.

When Xingonas in the Pit took the stage at the beginning of the fest, the room transformed into an intentional space of fierce joy, urgent catharsis, and collective care. Before I passed the mic to Geo, our youngest volunteer, I talked about the importance of all-ages shows and intergenerational solidarity. I talked about creating the kinds of spaces I needed when I was younger. Knowing I get to be a punk auntie to a generation doing punk bigger and better than I ever imagined almost brought me to tears.

From left to right: Our stage manager Des, production manager Monica, volunteer/photographer/videographer Geo, & me. (photo by @pray.4rain)

Because this is what the people in power don’t want us to have: a space full of movement and sound that feels like sanctuary and refuge. People dancing like it matters, moshing like it heals, singing as an act of political resistance. That energy carried the night from performance to ritual, pulling us a little further from isolation and closer to one another. It was, simply, magical.

BBPF reaffirmed that punk is more than a genre of music. It’s a language of resistance and solidarity. It’s a radical tool for marginalized people to resist their oppression, refuse state violence and white supremacy, and still make room for tenderness, queerness, and joy. The bands (Lagrimas, Las Hijas de la Madre, BÖNDBREAKR, Black Mercy, Morta, Fuchi, and quiet storm) delivered cathartic performances that felt like the release we need in these fascist times. Their sets held grief and rage and survival and future-making. Necessary refrains against a world intent on silencing us.

Accessibility was political, not optional. Safety, clean air, and care were central. All acts performed outdoors for better airflow. Volunteers secured the ADA entrance for wheelchair accessibility (shoutout to Crystal for crushing it at the entrance). Supporters provided masks and air purifiers (huge thank you Covid Conscious Bloc of San Antonio, Clear the Air Austin, and NALAC). Despite the ableist hellscape we live in that sacrifices our health to capitalism, I firmly believe: masking is community care. Clean air is a right.

And in response to transphobic policies that make public spaces unsafe, we transformed the bathrooms into genderneutral facilities to be accessible to people of all genders. That infrastructure is political. That decision is punk. That’s what it looks like when we stop asking for permission and start acting like we deserve to exist.

Many thanks to our sponsors (Music to Life and Wonder of You Massage) for helping make an accessible event possible.

BBPF matters because it pushes back against the erasure baked into DIY and punk cultures that have historically centered whiteness, cis-heteropatriarchy, and gatekeeping.

This festival reclaimed punk as home for Black, Brown, Indigenous, and other POC, for women, queer, youth, disabled, fat, migrant, trans, and nonbinary folks, for anyone told they don’t belong. We flew our freak flags, invented rituals of care and resistance, and imagined futures where our existence is celebrated, not policed.

And here’s the part I want everyone to hear, especially the people watching from the edges, thinking they’re “not important enough” or “not experienced enough” to build something: you can start your own festival. You can start your own collective. You can start your own safer space crew. You can make your own DIY infrastructure. You can build the kind of space you ’ ve been praying to find.

You don’t need a million dollars. You don’t need industry approval. You don’t need a perfect lineup. You don’t need permission from people who don’t give a shit about you anyway. You just need a few committed people, a shared politics of care, and the willingness to try. Because punk doesn’t belong to gatekeepers. It belongs to the people who show up and keep each other safe when the world is trying to break us.

And the biggest secret is this: we ’ re not alone. We never were. We just have to find each other. And once we do, we build.

BBPF was proof of that.

Xingonas in the Pit will keep building. If you’re in or near San Antonio, come through. Follow @xingonasinthepit for updates. And if you want resources for organizing your own festival hit me up at xingonasinthepit@gmail.com. I’m also planning a collaborative “howto start a fest” zine with BIPOC punk fest organizers, so keep an eye out. Because we’re done waiting to be included. We are the scene.