THE POLITICS OF CITY MAKING

“A city is a sensory emotional and lived experience”

- Charles Landry

HIDDEN HISTORIES

“History is written by the victors” - Winston Churchill ANTITHETICAL PERSPECTIVES

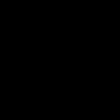

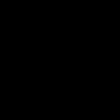

Perspectives and perceptions of Region C’s bicephaly: objectives and activities

COSMO [CITY]?

Can we call the rapidly developing multi-class urban area a ‘city’?

NOTE

What does city-making mean and how does it manifest in the case of Johannesburg, Region-C, through the lens of African urbanism?

Mji [m-jee] noun

1. City

Mzuri [m-zoo-ree] adjective

Root -zuri

1. Good, nice

2. Beautiful, pretty, lovely

3. Cute, atractive

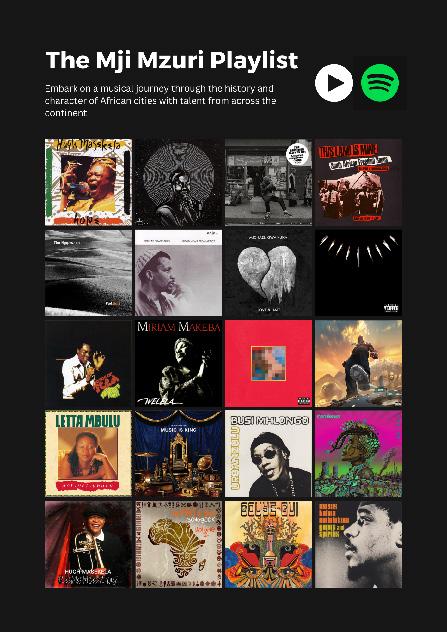

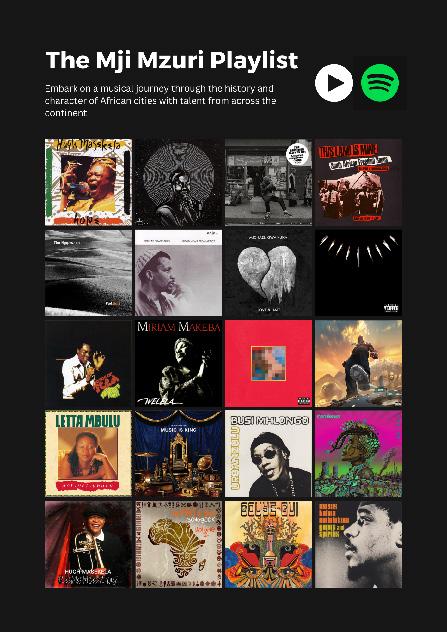

Welcome to Mji Mzuri!

The mission of the Mji Mzuri team is to take our readers through a journey of untold histories and peeking into the possibilities of the future of Region C in the City of Johannesburg. A journey that explores a sensory and emotional experience about the cities, townships and informal settlements of the region.

Through the lens of African urbanism, the magazine attempts to answer the question, ‘What does city-making mean and how does it manifest?’ An introduction to the African urbanism discourse sets the tone for Mji Mzuri. the various theories of city-making by African urbanists such as [insert names] is explored followed by a deeper understanding. The magazine is led by the objectives being: unravelling the various types of African urbanism and the emergence of of Johannesburg West; investigating the politics of spatially segregated cities; tracing the transformation from precolonial to contemporary urbanism; exploring the diversity of practices informal, formal and in-between urban spaces We kickstart the journey by exploring the notion of City-making and go on to address how this notion has materialized both in the passed and modern-day Region C.

We hope you enjoy the journey!

2

EDITORS’

Boitshoko Sebakelwang

Mihlali Mqalo

Morakane

Matabane

Sankara Gibbs

CONTENTS

The Politics of City-Making

The Art of City-Making

Landscape and Mining

Unfolding the secrets of Urban Design in Johannesburg, Region C: An interview with Nkosilenhle Mavuso

Hidden Histories

Hidden Histories

The evolution of transport networks in Region C

Time Travel through housing eras in Roodepoort

Antithetical Perspectives

Landmarks public perception and effects on the urban environment

Artisinal Mining businesses in abandoned residential house

Around the fire: Oral histories of our relationship to land

The Wild West Rand

The Wild West Rand

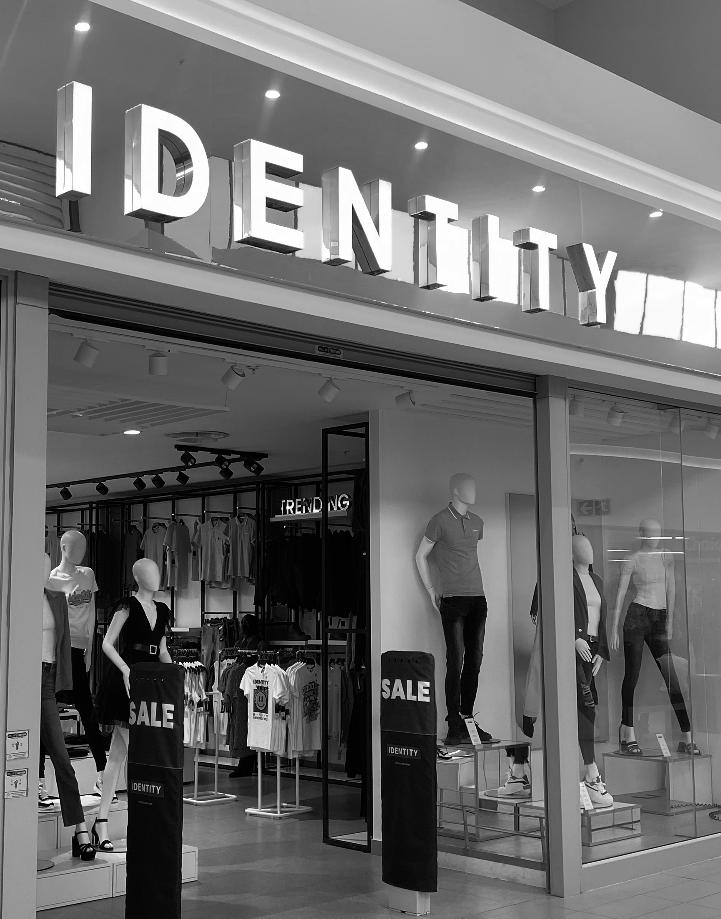

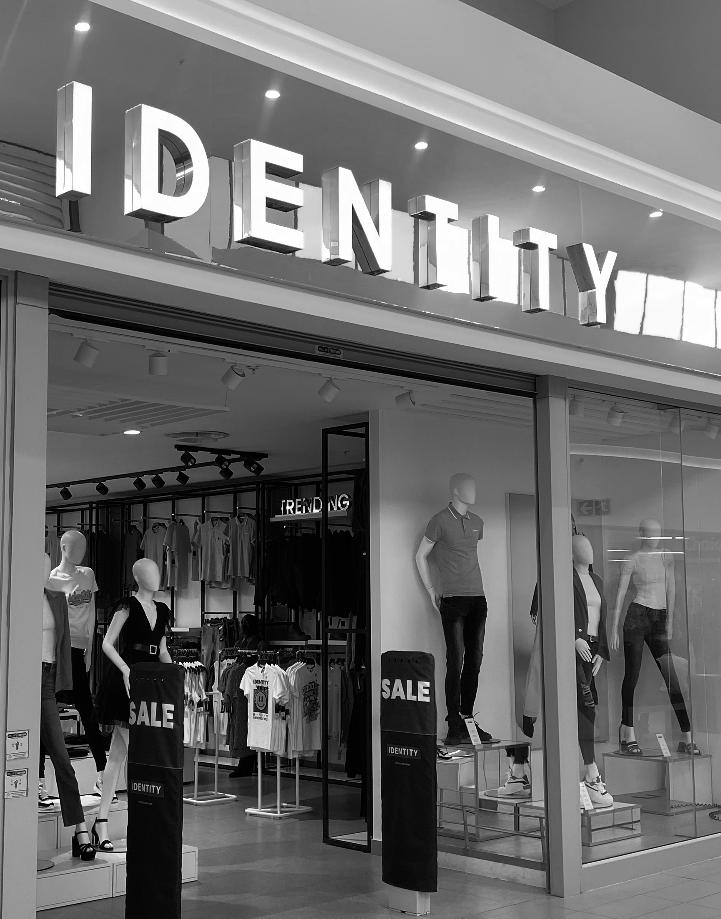

The socio-economic impact of mega-shopping malls in Region C Cosmo [City]?

3

REGION C

QUICK STATS

225 000

49,9%

65%

Are economically active LAND SIZE

318,47km 2

50.1% POPULATION

GENDER of the population has a post-matric qualification

32%

12%

Contribution to JHB economy

Unencumbered mining land offers a development opportunity within certain constraints

Major Areas

Roodepoort Krugersdorp

Cosmo City

1. City of Johannesburg (2019). Region C. [online] Joburg.org.za. Available at: https://www.joburg. org.za/about_/regions/Pages/Region%20C%20-%20Roodepoort/region-c.aspx [Accessed 24 Aug. 2023].

2. COGTA (2020). PROFILE: CITY OF JOHANNESBURG METRO 2. [online] Available at: https:// www.cogta.gov.za/ddm/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/City-of-Johannesburg-October-2020. pdf. 3.iconspng.com (2017). Coal mine shaft / tower PNG icons. [online] Free PNG and Icons Downloads. Available at: https://www.iconspng.com/images/coal-mine-shaft-tower/coal-mineshaft-tower.jpg [Accessed 24 Aug. 2023].

4. VectorStock (2019). City of johannesburg metropolitan municipality vector image on VectorStock. [online] VectorStock. Available at: https://www.vectorstock.com/royalty-freevector/city-of-johannesburg-metropolitan-municipality-vector-23934519 [Accessed 24 Aug. 2023].

5. Wikimedia (2023). [online] Wikimedia.org. Available at: https://upload.wikimedia.org/ wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/af/Gender_symbols_side_by_side_solid.svg/1280px-Gender_ symbols_side_by_side_solid.svg.png [Accessed 24 Aug. 2023].

4

5 Central Developments, Lions Park Lifestyle Estate Available at: https://www.centraldevelopments.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Lion-Pride-Rental-Welcome-Pack_Sep.pdf

AFRICAN URBANISM

WRITTEN BY: BOITSHOKO ORATILE SEBAKELWANG

Defining the African city has sparked several debates amongst scholars, built environment professionals and literary writers. Seemingly, no one can truly formulate a singular definition of what an authentically African city is. Contributing to this debate is the preconceived idea amongst most that Africans did not have cities before colonialisation of African countries by Europeans – an argument that suggests that Urbanism was not apparent in African city-making in the pre-colonial epoch, thus implying that colonialism is to be credited for any and all development that has occurred in in African cities [2].

The spatial layout and planning of pre-colonial African cities disproves this however, with evidence of city-making and planning in the pre-colonial era. During the periods when African Urbanism was the sole influence on development of African cities, the core ideological values upon which these cities were built is one of Ubuntuism – an ideology that holds principles of dignity, community, social justice, respect and shared responsibility,

amongst others, at it’s very centre. This way of developing cities and town places priority on the fostering of comradery as opposed to individuality in the making of African cities, as opposed to colonial and oppressive planning that prioritized the experience and growth of the white individuals, completely neglecting the experience of people native to Africa [4].

African Urbanism in indigenous African cities was – similar to many African histories – disrupted by colonialism and Apartheid (in the South African context) which brought about and later reinforced the notion of Western Urbanism in spatial planning. The influence of oppressive Eurocentric systems brought about by Apartheid and Colonialism became the dictators of planning in African cities – completely changing planning and its processes in African cities. Despite this ‘disruption’ that not only altered the perception of what development is, but additionally shifted the way Africans utilised their cities, there has been discourse around how African cities can make cities ‘more African’.

6

“AFRICA HAD A RICH PAST BEFORE AFRICANS WERE DEHUMANISED.”

- MUCHIE AND GUMEDE (2016)

In the South African context, the ‘end’ of the Apartheid era marked the beginning of the reignition of Africanisation [4] in our cities – particularly, the city of Johannesburg. This entailed looking at development of African Cities through the African lense, ‘finding African solutions to African problems’ [3].Therefore, although African Urbanism was once a way of life, it has now become a method for regeneration of African cities. – shifting the focus and purpose of planning from segregation and exclusion to planning with the main goal of achieving inclusion and bridging the gap created by Apartheid and colonialism. In doing so, we see African cities (ideally) reverting to utilising the same principles of Ubuntuism (as well as other African ideologies such as Maat, Harambee and Ujamaa) [3] and additionally, realising that there is power in unity amongst African countries - Pan Africanism. A philosophy popularised by African philosophers Julius Nyerere, Kwane Nkrumah, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and the likes. Although, like many other ideologies, one could critique these ideas of Pan Africanism, Africanisation and Afrocentric approaches as being utopian because the reality in African countries is the hegemonic power of the colonial powers that remain an apparent part of our processes and methods, these ideologies are still recognised as by some scholars to be the key to achieving true African Urbanism in today’s ‘post-colonial’ Africa [3, 4 & 5. This too, is true in planning and the distribution of land both pre and ‘post-Apartheid and colonialism’.

The employment of qualities bestowed upon us by the colonial and Apartheid eras will continue to have an impact on the way African countries are developed and perceived and subsequently have an impact on the African experience – the way in which we conduct ourselves, our cultural practices and ultimately, our lives. That being said however, it is imperative to invoke the idea of ‘Africanising’ our cities, and seeking what that means for the future of our cities. Adopting the qualities our ancestors used in developing cities they once called there own. Qualities of Ubuntus – a sense of togetherness [1, 3 & 4].

[1] Abubakar, I.R. and Doan, P.L., 2010, November. New towns in Africa: Modernity and/or decentralization. In African studies association 53rd annual meetings, November (pp. 18-21).

[2] Agbo, M. (2021). African Urbanism: Preserving Cultural Heritage in the Age of Megacities. [online] ArchDaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily. com/966346/african-urbanism-preserving-cultural-heritage-in-the-age-of-megacities.

[3] Muchie, M. and Gumede, V. eds., 2017. Regenerating Africa: bringing African solutions to African problems. Africa Institute of South Africa.

[4] Sihlongonyane, M., 2021. Ideologies, discourses and vectors of African urbanism in the making of South African cities. In The Contested Idea of South Africa (pp. 171-192). Routledge.

[5] Wiredu, K., 2008. Social philosophy in postcolonial Africa: Some preliminaries concerning communalism and communitarianism. South African Journal of Philosophy, 27(4), pp.332-339.

7

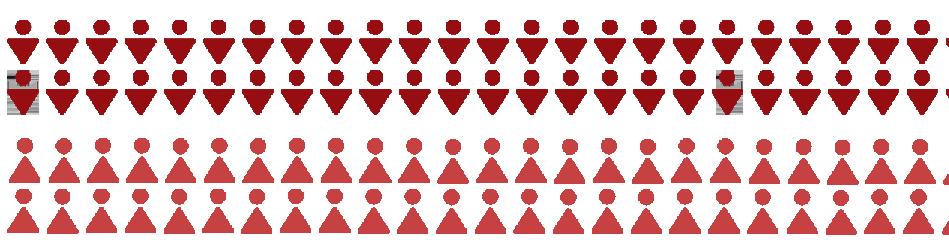

The Art of City Making: shaping the urban landscape

WRITTEN BY: Morakane Matabane

Cities are the epitome of human civilization, representing the convergence of diverse cultures, ideas, and opportunities. They are the vibrant hubs where people live, work, and play, offering a multitude of experiences and possibilities. But have you ever wondered how cities come into existence? The answer lies in the art and science of city-making. In this article, we delve into the multifaceted world of city making, exploring the dynamic interplay of creativity, innovation, and planning that shapes our urban landscapes.

There are a variety of understandings for what constitutes as good City Making. On the surface level, city-making is the process of designing, planning, and constructing urban spaces that cater to the needs and aspirations of its inhabitants, with urban planners being the architects of city planning with the help from the community. It involves a careful balance between functionality, aesthetics, and sustainability, aiming to create cities that are not only visually appealing but also efficient, inclusive, and liveable. Cullen puts emphasis of the physicality, design styles, building typologies, landmarks and nodes, which may be a rational objective and classical view of city making [1]. And the sorts of Alexander (1979) and Lynch (1960) who stress the layout of place and the notion of providing guides for navigating urban places, which is more a sense filled view of City Making [2][3]. However it should be understood that city making must be considered in a wider view than just the physical attributes and layout patterns.

City-making is not limited to physical infrastructure alone. It also encompasses the creation of a vibrant cultural and social fabric. Cities are melting pots of diverse cultures, and fostering inclusivity and diversity is essential for their success. This involves supporting the arts, preserving historical landmarks, promoting cultural events, and providing opportunities for people from all walks of life to thrive and contribute to the city's growth. As Montgomery stresses, the city is a phenomenon of structural complexity and that good cities tend to be a balance of reasonably ordered and city form and places of many and varied comings and going’s, meeting and transactions [4]. Good cities depend on their urbanity (activity, street life and urban culture. Therefore, urban planning that develops neatly laid out, organised in patterns may be successful in their own terms, but eventually lack urban quality.

While Montgomery describes a successful city-making as a place with invisible planning and natural results, with familiarity of open spaces and street life and heightens senses of users and provides sense of living [4]. Landry refers to city making as an art instead of a formula, that there is no simplistic, ten-point plan to be applied to guarantee the success of the making of a city but good city-making can be helped by strong principles [5]. He further defines cities as attractive, sustainable and financially viable environments.

8

https://www.deviantart.com/rmoy-art/art/University-Campus-Master-Plan-sketch-462651199

The skill that goes into technical city making

https://www.jamesholyoak.com/regeneration

Those that make the city and bring the culture

He argues that cities should not seek to be the most creative city in the world but rather strive to be the best and most imaginative city for the world. In many cases cities are described with bland and technical terms like “a large town” or “a municipal centre incorporated by the state” or even “a city as an area with a presence of certain institutions”, as if it were detached and lifeless. However, Mandy defines a city as a sensory, emotional and lived experience. That it’s more about connections between things and understanding culture is a superior way of ponder standing the world and indeed our space, our cities [5].

What gives cities character is their urban quality, their social, psychological and cultural dimensions of place. Successful city making is based on street activity, variety of said activity and how it occurs in and through buildings and open spaces. Urban design is essentially about place making, where places are not just a specific space but all the activities and events that made it possible. Thus, city-making includes all 3 elements physical space, the sensory experience and activity [4].

It is a multidimensional process that goes beyond mere construction. It is about creating spaces that reflect the aspirations and values of its inhabitants. By incorporating principles of urban planning, sustainability, inclusivity, city-makers strive to shape urban landscapes that are not only functional but also beautiful, resilient, and inspiring. The art of city-making is an ongoing endeavor, as cities continue to evolve and adapt to the changing needs and challenges of the future. Therefore, as we continue to shape and mold our cities, we should remember that every decision, every vison put on paper, carries the potential to mold not only the physical landscape but also the hearts and minds of the people who call these cities home.

[1] Cullen, G., (1961), Townscape, The Architectural Press, 1-199.

[2] Alexander, C., (1979) A Timeless Way of Building, Oxford University Press, Vol. 8, 1-552.

[3] Lynch, K., (1960) The Image of the City, The M.I.T Press, 1-202.

[4] Montgomery. J., (1998), Making a City: Urbanity, Vitality and Urban Design, Journal of Urban Design, Vol. 3(1), 93-116.

[5] Landry, C., (2006) The Art of City making, Earthscan, 1-498.

9

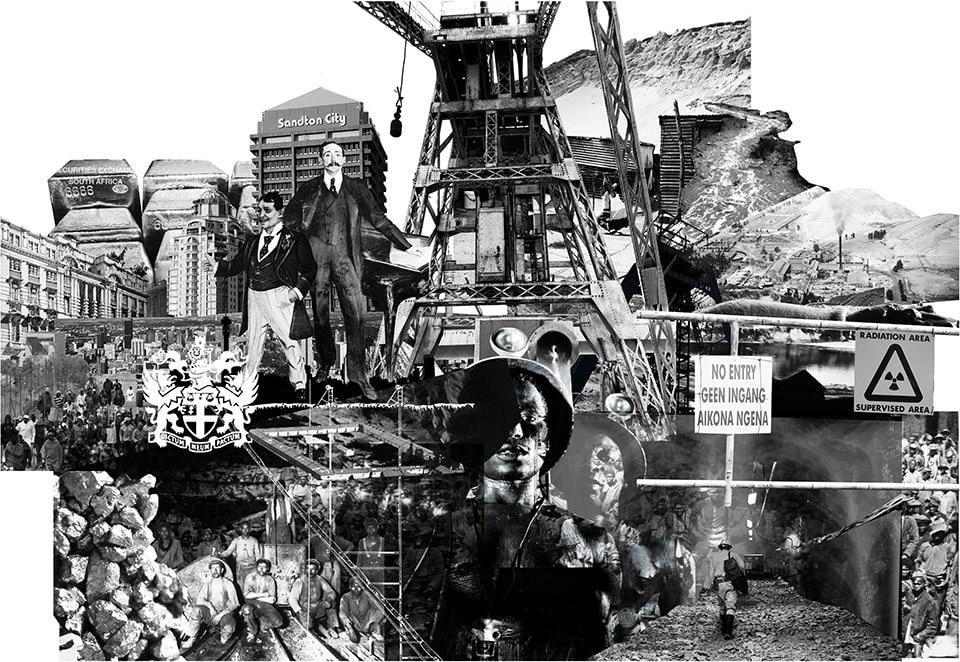

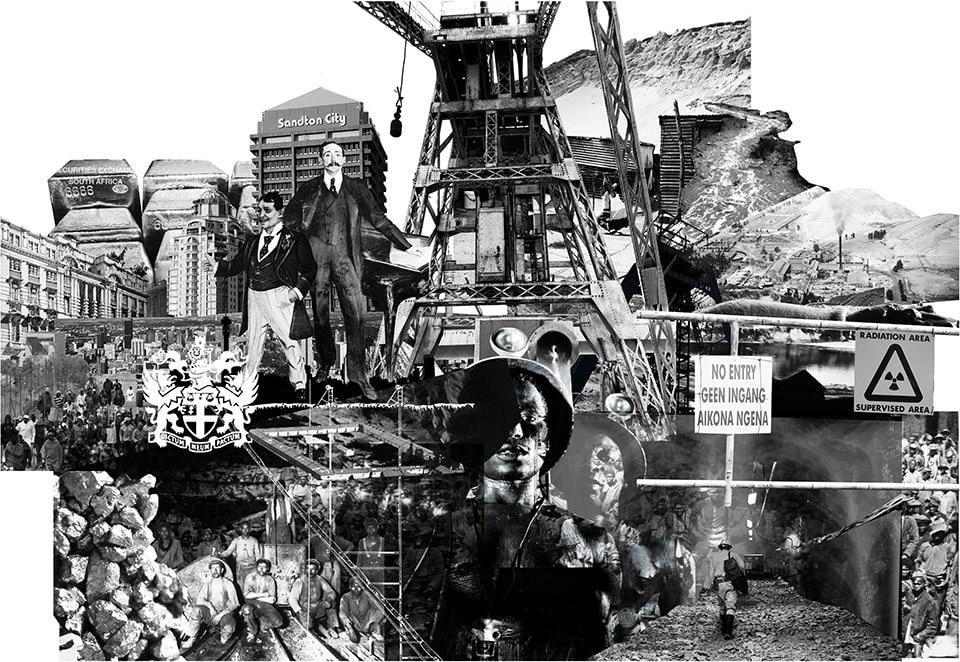

MINING AND LANDSCAPE

IN THE GAUTENG CITY REGION

WRITTEN BY: MORAKANE MATABANE

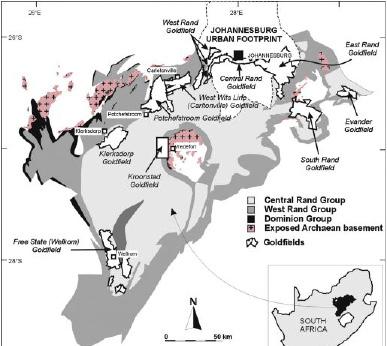

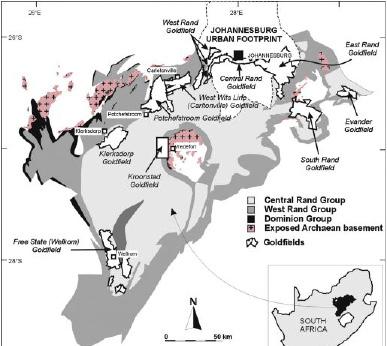

The article explores the landscapes that provided the means for the economic growth of the Gauteng-City Region. The Witwatersrand, the mining of Gold.

According to Bobbings and his colleagues, the landscapes of the Gauteng City Region can be traced back to about 3000mya when depression in the earth formed an inland sea [1]. Rivers in the area drained its waters into the depression while depositing sediment which would later become one of the largest deposits of minimal wealth on earth [1].

South Africa’s landscapes are endowed with a treasure trove of minerals, and among these, gold stands as a shining symbol of economic prosperity. The rapid mining of this geological wealth accelerated South Africa’s economic development, giving birth to the city of Johannesburg, Roodepoort, and a string of towns along the coveted gold reef in the 19th century. This article explores the profound impact of gold mining on the region’s development, from the flourishing industries and urban centres it created to the challenges posed by mining waste and the evolution of these communities beyond their mining roots.

The discovery of gold was the spark that ignited the remarkable development of Johannesburg and its neighbouring towns. In the 19th century, the glittering promise of gold drew thousands, leading to the rapid growth of urban centres [1]. Towns sprung up along the east-west line of the gold reef, each bustling with activity. As industries were established to support mining operations, job seekers flocked to the region [3]. Within a mere decade, Johannesburg’s population surged to over 100,000 inhabitants [2]. Gold production not only reshaped the city’s skyline but also had a profound influence on the natural landscapes of the region.

Gold production peaked in the 1970s, but this prosperity was not without its challenges [1] [3]. High production costs began to erode the industry’s profitability, leading to a gradual decline in active mining. Despite the decline, gold mining left an enduring legacy in the form of mining waste, including imposing mine dumps, expansive slime dams, and various waste storage facilities. These remnants of a bygone era continue to impact the region’s development and pose a significant challenge to future spatial integration. Many urban areas have developed around these pockets of mining waste or mine residue waste, serving as stark reminders of the region’s mining heritage. Johannesburg, in particular, successfully transformed itself into a manufacturing hub, diversifying its economy beyond mining. However, for distressed mining towns heavily dependent on gold extraction for income, the transition has been more challenging.

The landscape changes due to mining.

10

Photograph by: Clive Hassall.

Mining waste left behind. Photograph by: Clive Hassall.

Mining dumps in Johannesburg. Photography by: Clive Hassall.

DEVELOPING AN INDEPENDENT ECONOMY FROM MINING

Krugersdorp is a mining city established in 1887, lies on the Witwatersrand and was regarded as the industrial hub of western Gauteng [4]. Similar to the City of Johannesburg it has thoroughly modernised itself, developed recreational areas, business centres including shopping malls and works towards diversifying its economy to reduce its independence on mining. It has become a major urban complex and is part of a development strip stretching from downtown Johannesburg westward along the mining belt to Krugersdorp [5]. Krugersdorp’s CBD is the main centre of commerce and social administration and serves a regional function. The area around Krugersdorp has been further developed and has become an upper middle income residential area with a full range of urban amenities, services and facilities [5]. It terms of industry there is growth in manufacturing industries including food processing, automotive components, and machinery production. These have contributed to job creation and economic diversity. The expansion of retail and commercial activities have also been significant and a variety of services have emerged, providing employment.

KAGISO’S PERSISTING LINK WITH HISTORIC GOLD MINING

Kagiso: Established in 1920 by ex-miners, is a mining township located along the historic Main Reef Road [6]. After the mining came to a near standstill in the area, the people of Kagiso and the commune itself lost their livelihood and income. Today, the “Kagiso complex” is essentially an area of deprivation like the surrounding communes and with limited access to services, facilities and opportunities [5]. In Kagiso and surrounding settlements, many skilled miners have turned to informal mining as a source of income. Yet illegal mining emerges as a threat with devastating consequences for the political and economic fabric of our cities.

The township faces a challenge of forging a new path to economic independence, away from its deep-rooted reliance on mining. And while this mining legacy is a source of pride, it is also a doubleedged sword. Its economy has been closely tied to fluctuations of the global gold market, and Kagiso must diversify its economic base to ensure resilience in the face of uncertain times. One primary challenge is finding alternative sources of employment as mining jobs have traditionally been the backbone of Kagiso’s workforce. Upskilling and reskilling the local workforce will be required for the transition to new industries. The transition to economic independence will be a challenging one for this township, however, its resilience and determination are its greatest asset. [1]

11 KRUGERSDORP:

and Trangos, G.,

Mining landscapes of the Gauteng City-Region, GCRO,

date:

2023)

Worlds Bank,

South Africa Economic Update, World Bank,

Accessed at:

University

date: 25 May 2023)

Editors of Encyclopaedia,

Encyclopedia Britannica,

at:

(access

Bobbins, K.,

2018,

1-192, Accessed at: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/items/5bd791f9-78d4-4eba-a0ee-c79504cfadcf (access

25 May

[2]

2018,

1-62,

https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/798731523331698204-0010022018/original/ SouthAfricaEconomicUpdateApril2018.pdf (access date; 30 May 2023) [3] Thompson, L., (2001) A History of South Africa, Yale

Press, 1-418, 3rd Edition, accessed at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/leonard-thompson-history-south-africa-third-edition (access

[4] Britannica, T.

2008,

Accessed

https://www.britannica.com/place/Krugersdorp

date: 30 June 2023)

CHAOS OF AFRICAN CITIES

WRITTEN BY: MORAKANE MATABANE

THE BEAUTY IN THE

“The physical form of a city without people is useless; its the people who make a city a city.”

-Nkosilenhle Mavuso

NkosIlenhle Mavuso is an Urban Designer and a creator. He acquired his degree in BSc Urban and Regional Planning and masters in Urban Design at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Image recieved from Nkosilenhle

This article unfolds the secrets and realities of urban design in African cities. It is based on a conducted interview with an urban designer Nkosilenhle Mavuso.

INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY: MORAKANE MATABANE, SANKARA GIBBS, MIHLALI LORRAINE MQALO AND BOITSHOKO SEBAKELWANG

There are various perspectives on the concept of city-making, including technical, demographic, institutional, and cultural approaches. Nkosilenhle takes a technical standpoint, highlighting that the processes of city-making differ between African and Western contexts. He views space as a complex arena shaped by numerous contributors, emphasizing the need for both private and public investments in its development. In the South African context, investment in cities gained momentum following the discovery of gold, resulting in rapid urban development, the emergence of new towns, and significant economic growth.

As an urban designer with a keen interest in the cultural identity and intricacies of urban blocks, Nkosilenhle underscores the significance of comprehending human behavior to grasp the essence of urban spaces. He notes that a city is not solely defined by its physical infrastructure but also by its inhabitants who occupy and utilize the urban environment. People play a pivotal role in city-making. While formal city-making involves meticulous technical planning, design, and processes, the manner in which people engage with and use urban spaces, whether through appropriation or other means, is what truly breathes life into a city. It becomes a city through a sensory and lived experience.

Nkosilenhle maintains a positive outlook on African cities, appreciating the beauty within what many perceive as the ‘chaos’ of these urban environments. During the interview, he drew connections between the current state and planning of South African cities and the legacy of apartheid planning. He highlighted that apartheid planning significantly influenced the spatial layout, design, and location of cities in South Africa.

Shifting the conversation towards the ideal city, Nkosilenhle expressed that a city should offer opportunities to its residents, encompassing both formal and informal opportunities, as both contribute to city-making. This led to a discussion on the exclusion of ‘otherness’ within cities. In African cities, a substantial portion of urban spaces is inward-looking, protective, and exclusive, limiting the inclusion of diverse people and cultures. This phenomenon is particularly evident in cities like Krugersdorp, where informal trading, despite being a vital facet of African urban culture, is still marginalized and excluded from urban spaces, despite numerous policies and laws supporting it.

The interview was an engaging and extensive exchange of ideas, with this article only scratching the surface of the discussion. To delve deeper into the conversation and explore the full range of fascinating topics covered, scan the QR code to access the complete interview.

1 3

Appropriating Modernism: The Construction of apartheid Cities

This article identifies two planning theories/ models that are apparent in our cities (Region C). With each illustrated with an identified area in Region C.

WRITTEN BY: Morakane Matabane

Apartheid Planning

It is known that the apartheid system was sought to separate and racially divide South Africans, which was introduced in 1948 [1]. This was achieved through implementation of spatial settlement planning, especially in urban areas. Through the introduction of townships (that were inspired by colonial town planning), deliberate exclusion by design achieved racial segregation between the whites and the non-whites [1][2][7]. The townships were developed on the periphery of towns and cities, characterised by low levels of community facilities, commercial employment, low income and poverty [2]. The non-white population was forced to live in these locations through enforcement of the Group areas Act of 1950 and other planning legislation, they ensured separation of race groups by stipulating that “each race group should have its own consolidated residential area [1][7].

These regulations underpinned the creation of townships and shaped the South African cities into what we see today. These townships were areas of exclusion, containment and control. Majority being developed with linkages to the city centre and industrial areas through one road/ single railway line.

The layout and master plans of townships were based on planning models “neighbourhood unit” and British “New Town” [2].

They were planned as independent towns with their new economies, supporting 5,000 –6,000 residents with provision of a school and other social amenities.

In the context of Region C, we look at Kagiso as the result of these planning models. It was established in 1920 by ex-miners, and is located along the historic main Reef Road, between Randfontein and Johannesburg, on a portion of the Luipaardsvlei farm [3][8]. Kagiso was established as a result of the growing white suburbia in Krugersdorp, when it was decided that whites could not possibly share the same area with non-whites of Munsieville (a township that grew from informal settlements inhabited by mine labourers outside of the Krugersdorp mining town), its population was relocated to Kagiso [3]. Today the Kagiso area is a primary urban complex along with Krugersdorp, forms part the development between west Johannesburg CBD along the mining belt to Krugersdorp and is strongly linked to Johannesburg through the R512 [4]. The township falls part of the more disadvantaged settlements with limited access to services and facilities and is separated from Krugersdorp (which is the main business, social and administration centre, has full range of urban amenities, services and facilities) by an extensive east-west mining belt [4]. the township (like any other township in South Africa) represents implementation of the neighbourhood unit and British new town settlement models (refer to the figures below for comparison.

14

Neighbourhood Units in Lakewood, LA County. Image accessed from [2]

The Kagiso Township. Image Taken from ArcGIS.

Randburg: The Quintessential City of Suburbs?

Nestled within the vibrant metropolis of Johannesburg, Randburg holds a unique distinction among South African cities. Named after the country’s currency, the Rand, Randburg is a sprawling residential city located in Gauteng [5]. Established in 1959 through the amalgamation of 32 suburbs, it stands apart as an urban center with no heavy industries but a wealth of familyfriendly entertainment facilities and park-like areas [5]. In this article, we explore Randburg’s diverse neighborhoods, lush green spaces, and its identity as a “Garden City.”

Randburg’s charm lies in its well-defined and diverse neighborhoods, each with its own unique character. Whether you prefer the tranquil, tree-lined streets of Linden, the family-oriented ambiance of Northriding, or the cosmopolitan vibrancy of Ferndale, Randburg offers a wide array of housing options to suit various tastes and budgets. From sprawling estates to cozy townhouses, this city caters to all. Randburg is often referred to as a “Garden City” due to its commitment to preserving greenery amidst urban development [5]. This concept of a “Garden City” was initially introduced by Ebenezer Howard in 1898, emphasizing communities that blend urban amenities with access to nature [6]. Although Randburg doesn’t encircle a central city in a concentric pattern, it has earned the title of a “Garden City” thanks to its abundant green spaces.

One of Randburg’s standout features is its abundance of green spaces. The city is dotted with approximately 20 parks and gardens, providing residents with ample opportunities to enjoy the outdoors [5]. The Walter Sisulu National Botanical Garden, with its native flora and fauna, offers a serene escape from the hustle and bustle of urban life. Whether it’s leisurely strolls, picnics, or outdoor activities, Randburg’s green havens beckon both residents and visitors alike. Randburg’s commitment to greenery extends to its streets, which are lined with lush trees. This not only provides the city with a distinctive aesthetic but also serves a practical purpose. The canopy of trees casts shade, creating a cooler urban environment. Residents can relish a more pleasant city atmosphere, even during the scorching summer months. Randburg’s embrace of the “Garden City” concept serves as a model for urban planners worldwide. It demonstrates how integrating nature into an urban environment can improve the quality of life. As overcrowding and congestion plague many cities globally, Randburg’s commitment to greenbelts, parks, and lush streets offers a refreshing alternative.

Randburg, the “Garden City” of Johannesburg, offers a unique urban experience. Its diverse neighborhoods, commitment to greenery, and cooler, more pleasant atmosphere make it a haven for residents seeking the best of suburban living. Randburg’s legacy as a “Garden City” not only beautifies the city but also showcases the potential for harmony between urban life and nature in a rapidly growing world.

How

date: 20 June 2023) [2] Pernegger, L., and Godehart, S. (2007) Townships in the South African Geographic Landscape –Physical and Social legacies and Challenges, 1-25, Accessed at: https://www.treasury.gov.za/divisions/bo/ ndp/ttri/ttri%20oct%202007/day%201%20-%2029%20oct%202007/1a%20keynote%20address%20li%20pernegger%20paper.pdf (access date: 20 June 2023)

[3] Vusumuzi, K. (2017) Kagiso Historical Research Report, 1-26, accessed at: (PDF) KAGISOOHISTORICALLRESEARCH REPORT KAGISOOHISTORICALLRESEARCH REPORT | Cleopas Munemo - Academia.edu (access date: 20 June 2023)

[4] Yes Media, n.d, Mogale City Local Municipality: geography, History & Economy, Accessed at: https://municipalities.co.za/overview/1064/mogale-city-local-municipality#:~:text=Krugersdorp%20and%20 the%20greater%20Kagiso,mining%20belt%20up%20to%20Krugersdorp. (Access date: 23 June 2023)

[5] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia, 2008, Encyclopedia Britannica, Accessed at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Randburg (access date: 30 June 2023)

[6] Howard, E., (1965) Garden Cities of To-Morrow, The M.I.T Press, Vol. 23, 1-168

[7] Thompson, L. (2001) A History of South Africa, Yale University Press, 1-418, 3rd Edition, accessed at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/leonard-thompson-history-south-africa-third-edition (access date:

15

Housing Development Agency (2023) Apartheid Spatial planning, accessed at: (access

[1]

Arial view of the randburg area illustrating the greenery of the city. Image Taken from GoogleMaps.

majority of the streets in randburg suburbs look like. Image Taken from

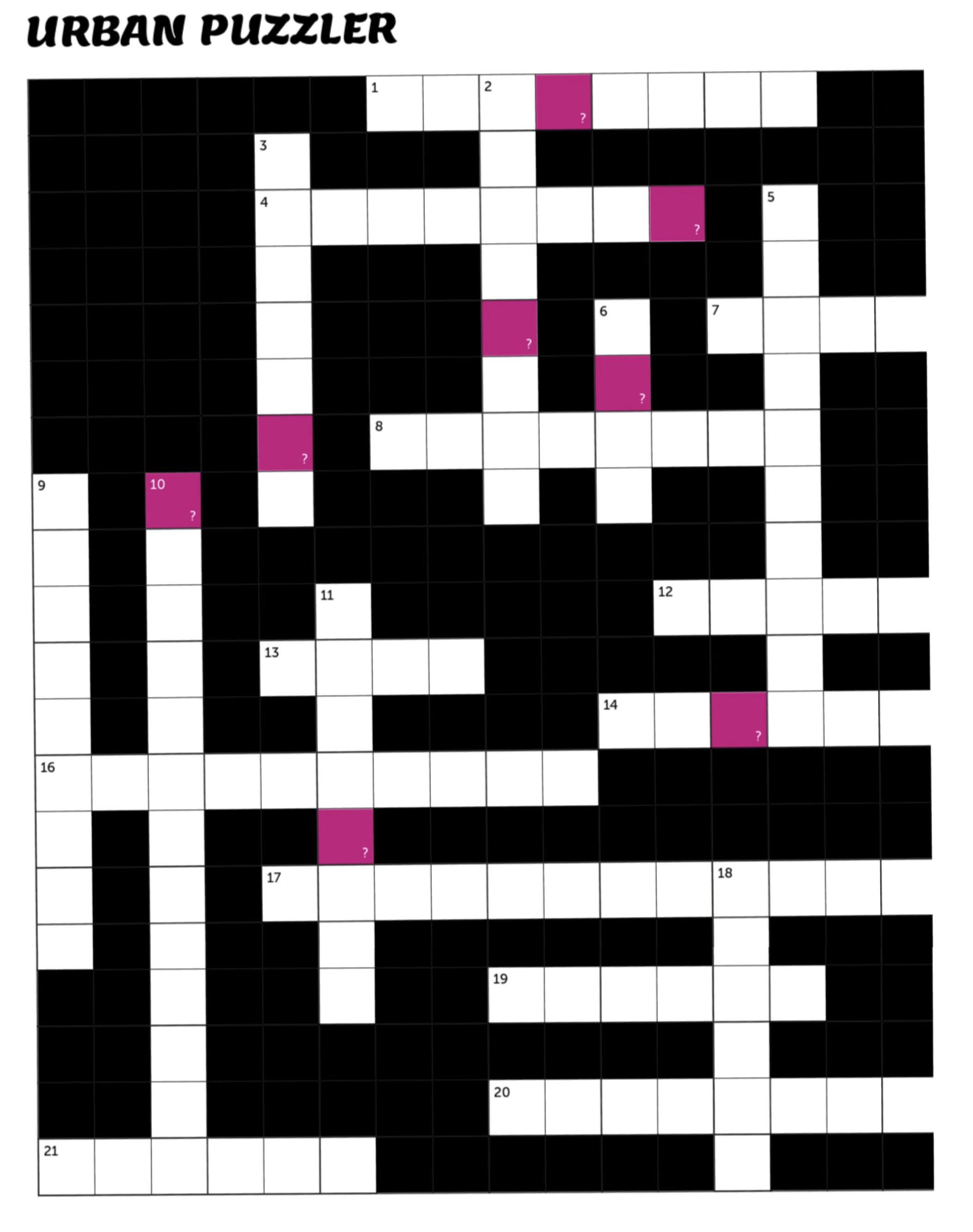

City-Making Challenge

INSTRUCTIONS: CLICK THE LINK OR CROSSWORD IMAGE TO ACCESS ONLINE CROSSWORD EXCERCISE

https://puzzel.org/crossword/play?p=-Nc_9gVpIWNCnwVJ8dCu

Across

1 Activities associated with the governance of a country or area

4 The study of the development and characteristics of cities.

7 Formal document that outlines responsibilities and is legally binding

8 The historic and cultural legacy of a city, often preserved through landmarks and traditions.

12 Takinghat form the critical part of city

13 Space for human occupation

14 The economic heartland of South Africa A collaborative and Multidisciplinary

16 process of shaping the physical setting for life.

17 56 kilometre long, north facing scarp in South Africa

19 A residential area on the outskirts of a city.

20 A residential community with landscaped gardens, parks, and other open areas 21 From the earth obtaining useful materials

Down

2 A feature of a landscape or town that is easily seen and recognised from a distance

3 Concerned with human behaviour and is a superior way of understanding the world and our cities

5 A city named after the red soil found in the area.

6 An area lived through a sensory, emotional and lively experience

9 Visible features of an area of land

10 The official power or control over a particular area or city.

11 A periodical publication containing articles and illustrations, often on a particular subject

15 A yellow metallic element that occurs naturally in pure form

18 The basic unit of urban space through which people experience a city

16

Urban Serenade

In the land of insatiable imagination and dreams, A city of gold awakens with a vibrant pace, with skyscrapers reaching for the heavens high, Like metallic giants touching the sky. The streets like a river of souls in a hurry, A concord of footsteps, a bustling flurry. With taxis darting like bees in a hive, In this city of dreams, where millions strive,

In the shades of night headlights flicker like stars at dusk, A carnival of colors, an urban musk. From the corner bistro to the saucy gizzard stand, A taste of cultures from every land. On crowded sidewalks, strangers unite, Their stories intertwine, day and night. Diverse language dance, conversations blend like whispers in the air,a symphony rare.

Laughter echoes through pathways, As characters converge, a carnival's whim. Some good characters, some bad Some mime on the corner, a silent sage, some paints laughter with gestures, others a silent stage.

But amid the chaos, a rhythm beats, A city's heartbeat, as it never retreats. Through hustle and bustle, a city is defined A fabric sewn with each thread a role.

Let's toast to this city of gold Where dreams are woven, strand by strand. With vivid imagery, wit, and delight, This urban harmony, a dance into the night.

17

Dev_Heart

HIDDEN HISTORIES

When looking at the notion of ‘City making”, it is important to acknowledge that it is exceedingly context based, given the different histories and backgrounds that impact particular cities. There is no exception to this is the African city. The incredibly unique history of African cities and the relation African people have with their cities sets African cities in particular, apart from other cities.

A factor the one cannot ignore when looking at this notion of city making in African cities is culture. The term ‘culture’ can be described as a way of life of a people. A sense of identity and

decider of the core values one holds and keeps and a factor symbolic of one’s descendance. The notion of ‘culture’ can be a determinant for how an individual identifies themselves in relation to others and most certainly, a determinant of the way in which people interact with their cities whether that be in the clothes that they wear, the must they listen to or even the languages they speak. It is this very significant element that acts as a determinant for city making that has been unequivocally and many a time, violently dismissed and subsequently, left unseen, undiscovered, and left in the shadows of ‘modernity’ [1].

“History is written by victors” – Winston Churchill

Events history such as colonialisation have undoubtably altered the cultural make up of many ancestral lands. South Africa is no stranger to this reality. This is true in many instances and is evident in many African cities.

[1] Chapman, M., 1995. Mandela, africanism and modernity: a consideration of Long walk to freedom. Current writing: text and reception in Southern Africa, 7(2), pp.49-54.

[2] Krugersdorp Museum. 2023. Mogale City, Corner Commissioner and Monument Street, Krugersdorp CBD. Visited by Mihlali Mqalo and Boitshoko Sebakelwang on 14 July 2023.

[3] Ramsay, J., 1991. The Batswana-Boer War of 1852-53: how the Batswana achieved victory. Botswana Notes & Records, 23(1), pp.193-207.

[4] Roodepoort Museum. 2023. Roodepoort, 100 Christiaan de Wet Rd, Florida Park. Visted by Mihlali Mqalo and Boitshoko Sebakelwang on 14 July 2023.

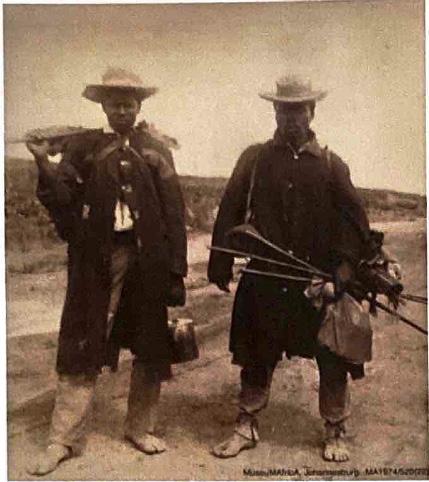

KGOSI MOGALE WA

18

MOGALE Carnivore Resturant, Johannesburg (n.d.)

“HISTORY

is written by VICTORS” – Winston Churchill

WRITTEN BY: BOITSHOKO SEBAKELWANG

Located in Region C of the City of Johannesburg is a city that is a prime example of ‘lost’ of culture. Mogale City or ‘Krugersdorp’, originally home to Batswana settlers in the 1800s, led by Kgosi Mogale WA Mogale, Chief of Batswana tribes, Bahurutshe, Bakwena and Bakgatle, whom he led to multiple areas situated in what we know now as Region C including Swartkoppies near Brits and Krugersdorp and Roodepoort amongst others, has since experienced this ‘phenomenon’ [2]. Once rich is Batswana culture, is now dominated by Afrikaans culture and history of native Krugersdorp and Roodepoort natives has seemingly been relegated to the background. This can be attributed to land and the value thereof. In many instances, land has been at the centre of war – wars between nations, both completely different and similar in likeness. In South Africa, one of the displays of this war over land is the Apartheid era. The discovery of Gold in the Krugersdorp and Roodepoort mines only fuels this war and the oppressive methods of the regime completely displaced the Batswana settlers. As if

displacing Batswana was not enough, the preservation of their culture and history was never made a priority in the Region [2, 3 & 4]. Effectively, prompting ‘Hidden Histories’. Some parts in particular of these histories have been admittedly, deliberately neglected and somewhat ‘misrepresented’. This evident in both the Krugersdorp and Roodepoort Museums – institutions that have been established with the purpose of storing and preserving artifacts, objects, and truths of indigenous people. Granted, such an ugly truth is a prime example of how events in history have completely altered the way native cultures are viewed and respected, however, as time goes on it is up to us to bring our histories out from the where they have been buried.

Now that history of indigenous people and cultures is not represented in museums, history books and internet sources, they have somehow been preserved in the minds of African people and passed down intergenerationally through story-telling. [learn more on pg

19

INSTRUCTIONS: ACCESS THE GRAPHIC REPRESENTATION OF THIS STORY IN THE FOLDER LABELLED: KGOSI MOGALE_JOURNEY OF THE BATSWANA Disclaimer: Mental Canvas app is required to open this document, as well as a touchscreen device to interact with the graphics.

AROUND THE BONFIRE

Umhlaba wethu, isidima sethu - Our soil, our dignity

Storyteller: Vuyokazi Nkosiyane

Vuyokazi explains the complexities of her family’s relationship with the land dates back to the Xhosa Wars. The conflicts between the chiefs and different Xhosa kingdoms allowed for the British to take advantage of the situation, meddling in their politics. Generations later, after loss of cattle and livestock wealth, the Nkosiyane family was forced to move from the homelands of Eastern Cape to Soweto. Living conditions somewhat improved because of the emerging developments in Johannesburg. Despite this, the present generation of this family still believes in going back to the Eastern Cape every now and again, seeking to retain their dignity, identity and connection to their culture.

INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY

Land and Identity

Storyteller: Khubu Zulu

Join us in this episode as we delve into the life journey of Khubu Zulu, a remarkable multi-media artist and mother of two. Born in KwaMashu, a vibrant township in Durban, Khubu shares how her upbringing by a defiant single mother and grandmother shaped her identity. Through her insightful narrative, discover how her experiences in places like Durban city, Claremont, Newland East, and Johannesburg have woven a tapestry of influences that define her unique perspective as an artist and individual. Tune in for a captivating exploration of how geography and personal history intersect in the art of self-discovery.

CONDUCTED

20

MIHLALI MQALO [20 MINUTES]

INTERVIEW

BY SANKARA GIBBS [60 MINUTES]

STORYTELLING AS A FORM OF PRESERVING AFRICAN HISTORIES.

WRITTEN BY: SANKARA GIBBS, MORAKANE MOTHABANE, MIHLALI LORRAINE MQALO & BOITSHOKO ORATILE SEBAKELWANG

The Selebogo Perceptive

Storyteller: Sylvia Sebakelwang

This segment focusses on the perspectives and experiences of Mpho Gift Selebogo – a black women and Congreve Selebogo – a coloured man, living in South Africa during the Apartheid era. Their stories are told by their daughter Sylvia Sisimogang Sebakelwang (previously Selebogo). Sylvia takes us through the experience her parents had as owners of land and property during era that is notorious for disallowance for the ownership of land by people of colour. The story accounts for the occupation and shortly after, the loss of properties that were rightfully their own. The distrust between people and state, and subsequently the impact of that on the views and experiences of people of colour in a country that oppressed them.

INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY BOITSHOKO SEBAKELWANG

Kresemose Letsatsi le penyapenya

Storyteller: Vuyokazi Nkosiyane

The story revolves around Grandmother Matabane’s childhood Christmas experiences. On Christmas Eve women donned trousers, while men wore skirts and dresses, and together, they went from door to door singing and receiving gifts. Early on Christmas morning, villagers gathered, eagerly awaiting the sunrise. As the sun emerged from behind the mountains, it would seem to dance and change colours like a rainbow. This breathtaking spectacle held profound meaning for them, symbolising the essence of Christmas.

Matsatsi a Kotulo

On a particular Friday morning every year, between July and September. Excitement at the prospect of reuniting with their parents and indulging in the bountiful harvest. The village kids travel almost 50km to the farms with unwavering enthusiasm.

INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY MORAKANE MATABANE [15 MINUTES]

Get you headphones ready, https://open.spotify.com/show/1dvwSr1nmQR4V1xkHp048u?si=1e448e7f711a450d

21

[50 MINUTES]

DID YOU KNOW?

Land in the Roodepoort and Krugersdorp areas was mainly occupied Tswana and Sotho communities who utilised their land farming and foraging purposes as a means of survival. These were the first tribes to establish settlements in the region between 900 and 1300 AD. These settlements were unbalanced by a host of wars that took place – many of these being over land and who the ‘rightful’ owners of the land were. The resultant of war was drought and famine, leading to issues we often see today of shortages of resources and land.

THE ROODEPOORT MUSEUM

[1] Roodepoort Museum. 2023. Roodepoort, 100 Christiaan de Wet Rd, Florida Park. Visted by Mihlali Mqalo and Boitshoko Sebakelwang on 14 July 2023.

[2] Krugersdorp Museum. 2023. Mogale City, Corner Commissioner and Monument Street, Krugersdorp CBD. Visited by Mihlali Mqalo and Boitshoko Sebakelwang on 14 July 2023.

THE VICTORIAN HOUSE THE MODERN HOUSE THE FARM HOUSE

Farmhouse (Sebakelwang

The Victorian (Sebakelwang

The Roaring (Sebakelwang

22

MIHLALI MQALO AND BOITSHOKO SEBAKELWANG

THE ROODEPOORT MUSEUM TAKES YOU THROUGH THE DIFFERENT ERAS THAT THE HOUSING AND ARCHITECTURAL STYLE WERE INSPIRED BY.

WRITTEN BY: BOITSHOKO ORATILE SEBAKELWANG & MIHLALI LORRAINE MQALO

BEFORE THE DISCOVERY OF GOLD IN REGION C

As it was the era in which farming was the main ‘economic’ activity upon which people depended on, the most common type of housing one would find in the region are farmhouses. These farmhouses were located far from the towns that had been established resulting in there being a ‘simpler’ way of living for those who lived on these farms, but the fact remains even in modern times that land was a resource of power, a way of life, a representation of one’s lineage and a medium through which one can connect with their spirituality.

THE VICTORIAN ERA

Roodepoort went through a significant transition from the ‘Farm House’ dwelling type. The Victorian era was a period in South Africa between the 1830s and early 1900s. The wealthy residents were inspired by Victorian architectural style. Typical interior decoration and design in houses would have ornamental decorations, larger windows, high ceiling, decorative plasterwork and roofs and fireplaces in most rooms. The houses were often built for the elite in Roodepoort, thus surrounded by amenities such as gardens, stables and verandas, showcasing their wealth and social status in society.

THE ROARING ERA

The Roaring Era came after the Victorian Era with a more modernist approach to interior decoration and housing. This period happened after the 1920s, and was prompted by Urbanisation and social changes. There was a prominence in Art deco architecture in Roodepoort which incorporated pieces such as glass, geometric shapes and other decorative motifs. Urbanisation increased the demand for housing and required a more modern architectural style. However, some elements from the Victorian era remained such as decorative pieces and fireplaces.

Farmhouse Exibit, Roodepoort Museum. (Sebakelwang & Mqalo, 2023)

Victorian Era Exibit, Roodepoort Museum. (Sebakelwang & Mqalo, 2023)

23

Roaring Era Exibit, Roodepoort Museum. (Sebakelwang & Mqalo, 2023)

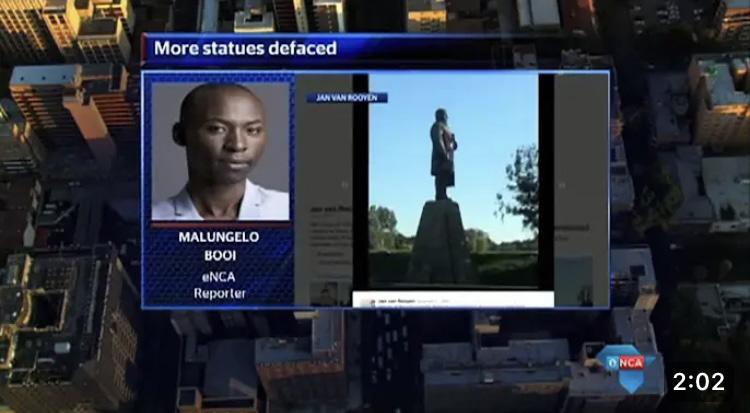

LANDMARKS AND MONUMENTS IN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT

WRITTEN BY: MIHLALI LORRAINE MQALO

Monuments occupy a unique space in the urban environment, serving as a mechanism for the translation of social memory and spatial reference [1]. Additionally, the urban landscape is the art of visually integrating and structuring the buildings, streets, and spaces that comprise the city environment as a combination of manmade and natural areas, with the goal of inspiring a feeling of meaning and identity [3].

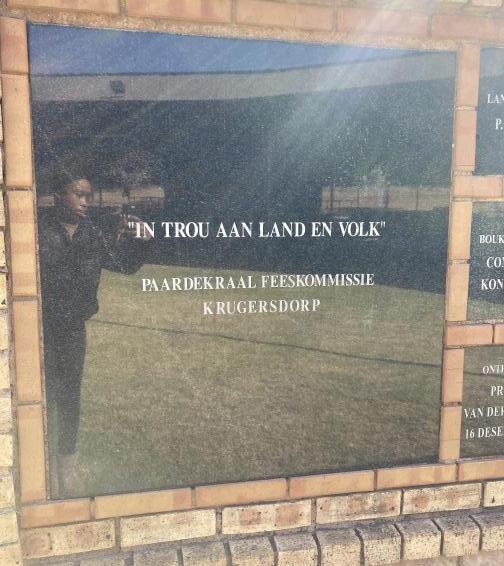

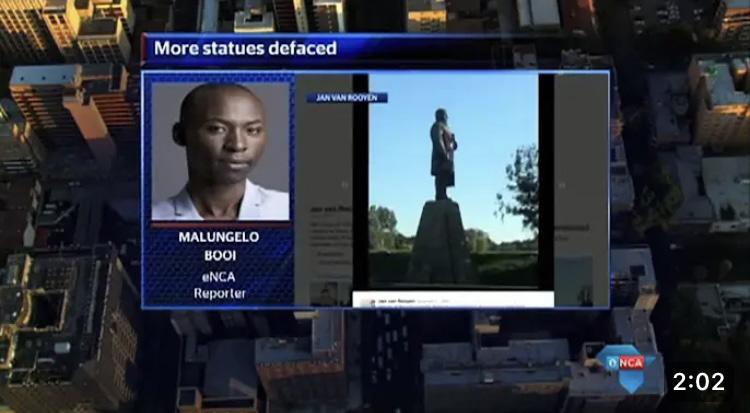

Monuments and landmarks have long served as vital markers of cultural identity and historical heritage, eliciting powerful emotions and influencing public opinion. On the one hand, these iconic buildings tend to make a positive impression on the public, serving as memorials of nation’s successes and achievements, instilling pride and unity in the community. Public opinion, on the other hand, can be negative, particularly when monuments are associated with controversial events or demographics which bring back traumatic memories [2]. It can result in historic misunderstanding, cultural insensitivity or criticism of problematic ideas, calls for abolition or reconsideration. Citizens commonality in daily life, including representatives of diverse social groups place them in concrete space,

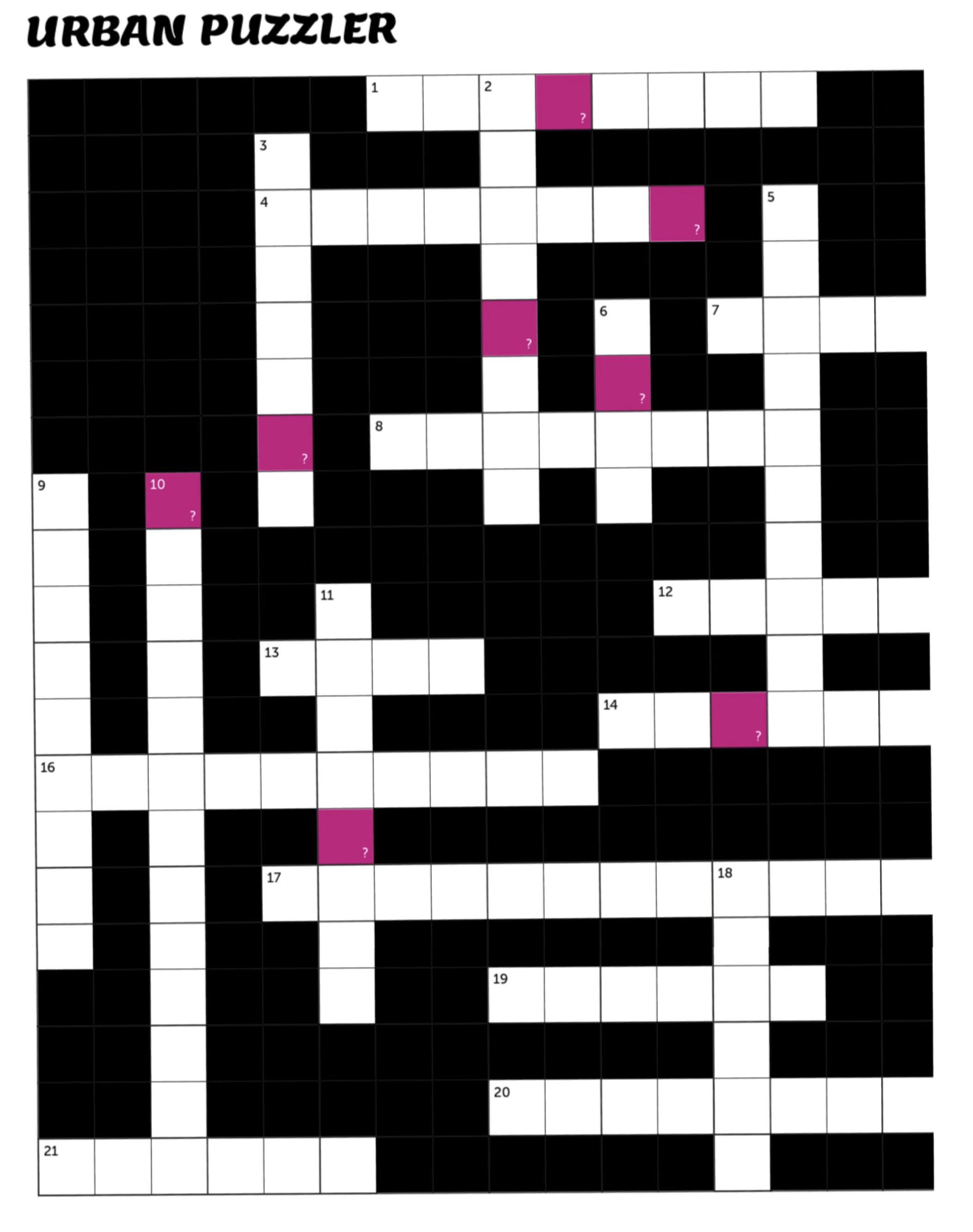

transforming the city into a meaningful space. As a result, the city becomes a symbolic place (monuments, temples, housing etc.) as individuals fill semantic sites with a symbol of their own [1]. This is also true Krugersdorp, a town rich in culture and history. Paardekraal Monument, a historical landmark in South Africa, has generated both positive and negative reactions from the public. This monument that preserved the promise of the Transvaal Boers to regain independence from the British Empire before the First Boer War on December 13, 1880. The Greco-Roman inspired architect Sytze Wierda and he made plans for the monument building. On the one hand, those who see it as a symbol of Afrikaner identity, see it in a positive light. This monument is seen as a reminder of the history of Voortrekker and the freedom struggle. However, others view it negatively, viewing it as a symbol of racism and colonialism [2]. They believe it glorifies an era of oppression and discrimination – similarly to the statue of Paul Kruger and Johannes Gerhardus Strijdom. Ultimately, public opinion on the Paardekraal Memorial is complex and diverse, reflecting divergent views in South African society.

24

In Krugersdorp, landmarks and monuments have been vandalized on various occasions. Commemorative monuments and comparable symbolic artifacts are both the most visible manifestations of state power and its most direct source of vulnerability and contradiction. Politically motivated “ideological vandalism” manifested itself in post-apartheid South Africa in these categories: “black on white” and “white on black,” [2]. The broader trend of commemorative

monument neglect, misuse, and disdain that has persisted throughout the democratic age. This can be assessed in the case of the Paul Kruger and J.G Strijdom statues. The fact that both apartheid and post-apartheid memorials are equally damaged implies that for many, a memorial is not perceived as a dignified public symbol with a distinct political ‘message’, but rather as a generic and basically worthless component of urban architecture.

INTERVIEW WITH SID MANN

Sid is an Afrikaans man who is in charge of groundskeeping the land upon which the Paardekraal monument stands.

He proved us with a personal account of his perception of the 1st and 2nd Boer Wars , and the significance of the monument for himself and other Afrikanners who gather in celebration of the commemoration of their forefathers.

https://open.spotify.com/show/1dvwSr1nmQR4V1xkHp048u?si=1e448e7f711a450d

South Africa’s democratic society has instilled laws that support the freedom of expression of all narratives, and argue that the marginalized have also been acknowledged by their monuments that speak to their struggle. Many historical monuments, particularly those devoted to leaders or commanders, serve an ideological

function in this regard. Placing them in visible and interactive spaces intends to demonstrate the special value of a person, admiring their deeds given the land and the city [1]. It is important, however, to note that some monuments are devoid of personal value, and simply exist to navigate people through the city.

[1] Antonova, N., Grunt. E., Merenkov, A. (2017). Monuments in the Structure of an Urban Environment: The Source of Social Memory and the Marker of the Urban Space. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, pp 1 – 7.

[2] Marshall, S. (2017). Targeting Statues: Monument “Vandalism” as an Expression of Sociopolitical Protest in South Africa. African Studies Review, vol 60(3), pp. 203–219

[3] Shahhosseni, E. (2015). The Role of Urban Sculpture in Shaping the Meaning of Identity in Contemporary Urban Planning. International Journal of Science Technology and Society 3(2):24

[4] eNCA, (2015). More statues defaced. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=more+statues+defaced

An interview with Sid Mann was conducted on the 14th of July by Mihlali Mqalo and Boitshoko Sebakelwang in Paardekraal, Krugersdorp.

(Mqalo, 2023)

Translation: in fidelity to land and people

(Mqalo, 2023)

Staute of Kgosi Mogale placed outside of Krugersdorp civic center.

(Mqalo, 2023) Paardekraal commemorates the vow made by Transvaal Boers to regain independance from British Empire

25 CLICK THE LINK TO ACCESS THIS PLAYLIST:

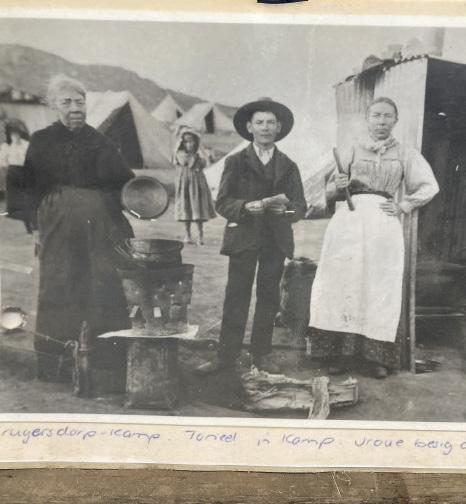

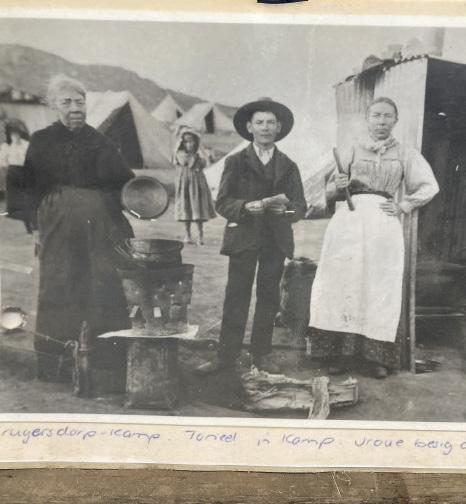

(Mqalo, 2023) Translation: Scene from camp, women making food (Mqalo, 2023) Statue of former president of South African Republic, Paul Kruger

ARTISANAL MINING, ABANDONED HOUSES AND SOCIAL POLITICS IN THE FORGOTTEN TOWN

WRITTEN BY: MIHLALI LORRAINE MQALO

Abandoned mines granting oppotunities for artisinal miners, yet causing devastation for residents living within the settlement located near them: the case of Durban Deep.

Durban Deep is a located in Roodepoort and forms part of the mining belt that runs through the R41, approximately 20km west of the Johannesburg inner city. This area has a long history that dates back to the late 19th century, but is now notoriously known for its abandoned residential houses and artisanal mining from multiple gold bearing conglomerate reefs, creating multiple goldfields in the East Rand, Central Rand and West Rand [1].

The politics of the zama-zama sheds a light on the complex interplay between the state, the mining industry and the informal economy. Zama-zama is a local South African term that refers to ‘artisanal’ who operate outside of mining laws and legislative frameworks as legitimate stakeholders. The artisanal mining businesses refers to small-scale mining activities conducted by individuals who use rudimentary tools and techniques to extract raw minerals [2]. In the case of Durban Deep, zama-zamas have become a part of the informal economy and has led to complicated socio-political tensions. Many of them are from Zimbabwe and migrated to this area, seeking greener pastures and faint hope that gold is still discoverable [3]. Illegal mining activities typically result in a variety of statutory, regulatory, and criminal offenses. Unfortunately, these activities have not benefited the settlement swellers as they are done as a means of survival. The state and police force has attempted to enforce law upon the miners due to safety, but fail to operate in this area because of ists infamous crimes and fatalities. Operations are popular in abandoned mines and provide

Minerals extracted by Zama-zamas (Shaun Swingler, 2018)

Abandoned Durban Deep Mine (IOL News, 2018)

26

Map showing Durban Deep Mine (Hein and Nhlengetwa, 2015)

security for the miners as they believe they are less regulated and there would be a lower chance of them getting caught. Durban Deep is deemed to be a dangourous place, consequently making it beneficial for the miners. The abandonment of mining shafts and infrastructure had dire effects on the urban landscape. Creation of access portals, ventilation shafts, slime dams and waste dumps that were not rehabilitated gave rise to acid mining drainage, collapseinduced mine seismicity [2], but provided an opportunity for the illegal miners to create a business and sustain their livelihoods. In circumstances were they don’t find gold in the mine, relocation becomes the resolution [3]. The industry swiftly becomes an ugly game of survival of the fittest.

The area surrounding Durban Deep is characterized by countless abandoned residential houses and buildings. These building structures are remnants of the mining era when the area was still populated by mine workers are their respective families. Over time, many of them relocated because of the decline in the mining industry, leaving behind empty homes. Today, these homes are occupied by the zama-zamas and show no indication of being renovated. Burnt down houses are often left as is, with many residents left with the decision of relocating [3]. Nonetheless, the Durban Deep mine is close to Fleurhof inclusionary housing and Matholesville settlement also has a number of RDP houses. These initiatives were created during the time of the illegal mining, and one can assume that they are prone to being affected by the zama-zamas. Community members remain upset at the governments’ inconsistent involvement in such life-threatening situations. The state continues to turn a blind eye to the petty crimes, innumerable rape and murder cases.

‘‘They should shut it down... that place is not for people to live in’’ - Connie

‘‘Don’t think even you, you are safe here. This place is not good for you’ - Freedom

[1] Hein, K. A. and Nhlengetwa, K. (2015) Zama-Zama mining in the Durban Deep/Roodepoort area of Johannesburg, South Africa: An invasive or alternative livelihood? University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, pp 1 – 3.

[2] Minerals Council South Africa. Artisanal and small-scale mining. Minerals Council South Africa, pp 1 – 12.

[3] Unreported World (2018), ‘Searching for gold in South Africa’s Abandoned mines’. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WeKO12xwpKA

Abandoned Durban Deep Mine (IOL News, 2018)

Abandoned house in Durban Deep settlement (Julia Cumes, 2020)

27

THE LAND EXPERT

28

INTERVIEW 10/08

AKHO MAYATULA

Specialist Town Planner currently working at the City of Johannesburg, under the Department of Land Use Management. Akgo conducted her studies in Urban and Regional Planning at the Cape Peninsula University of technology

Boitshoko: Does the Department of Land Use Management get involved with the upgrading informal settlements in West Rand?

Akho: No, the department only deals with rezoning of land and implementing what the Department of Spatial Transformation proposes in their Spatial Development Frameworks. There’s a greater focus on land management and zoning according to the SDF then there is in spatial involvement and transformation.

Boitshoko: What challenges is the department faced with when it comes to rezoning and development?

Akho: There’s so many! But the prominent challenges are surrounding the issues of land grabs that are outside of the UDB (urban development boundary) where the city can’t provide the necessary services. People usually have little regard of environmentally sensitive areas and leads to them illegally occupying the space. There are so many environmental and geological studies that need to take place before development can even take place, and title deeds need to be granted to the residents as well.

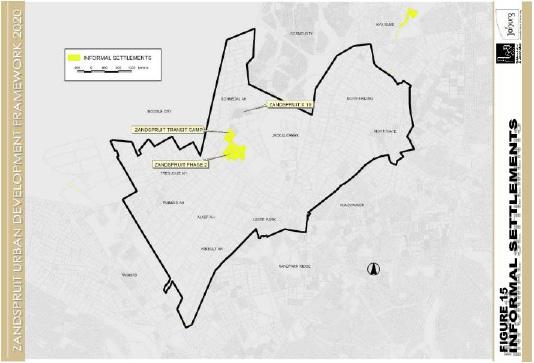

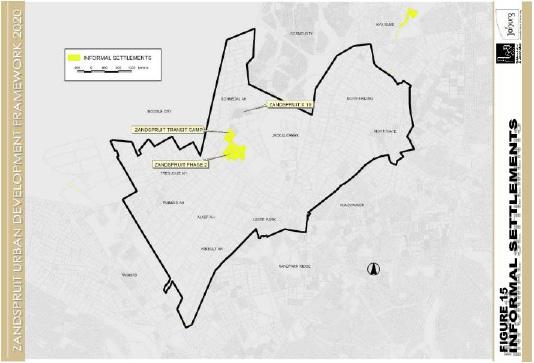

Mihlali: Were these processes considered in Zandspruit and Princess?

Akho: Well… the land the informal dwellers are occupying is council-owned. So, this means that there could’ve been communication with the JPC (Johannesburg Property Company), and there was collaboration between the different departments to negotiate that rezoning; but the housing and spatial transformation department are more involved with such issues. We would simply look at the SDF and assess how they have considered the area.

Boitshoko: How long would the rezoning process take?

Akho: From the submission date to the end, it would take four to six months, ideally! But they could take much longer than that.

Mihlali: Has the department experienced any political influences that have hindered zoning of certain areas, and how has the department strategically dealt with such situations?

Akho: Oh that is a difficult one – but yes. Political parties would communicate with the council managers, who would then consult with us and give instructions on what we need to rezone the areas to. Uh, political parties would advocate for the provision of housing without considering the relevant policies – they don’t care about what our policies say! They would say things like ‘’people need housing’’ or ‘’we must get the land back”. Unfortunately, some of these areas are beyond the UBD and town planners are left to deal with the ‘mess’.

29

CREATING BRIDGES: CASE OF PRINCESS INFORMAL SETTLEMNT AND ZANDSPRUIT, RUIMSIG

WRITTEN BY: MIHLALI LORRAINE MQALO

Informal dwellers seem to have strategically placed themselves in areas that provide the most opportunities for them, which are predominantly affluent neighborhoods. However, this has led to friction between the inhabitants of these wealthier regions and informal dwellers.

The repeal of the Apartheid’s legislative framework brought immense hope to individuals who had previously been disadvantaged. Government made promises that alluded perfect and instant spatial, economic and social equality, as well as hopes to uplift the affected people from the oppression and poor standard of living [5]. These promises, however, have not been holistically fulfilled. In consequence, those affected have been driven to seek and create opportunities of inclusion themselves. The resistance of staying in detrimental areas compelled the move to areas

that offer a sense of hope. The rapid migration to these areas created the artless and instantaneous informal settlements. Such incidents are not foreign in places like Ruimsig and neighbouring suburbs (Lindhaven, Wilropark and Witpoortjie) near Westgate Mall. The perpetually growing informal settlements place themselves in affluent areas that have vast amenities in close proximity and job opportunities that fit their skillset. Consequently, the politics of accessing these services in this setting activates the struggle between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’.

Demographic statistics of Roodepoort

Informal dwelling/shack, NOT in backyard, e.g. in an informal/ squatter settlement (number)

Princess informal settlement, Roodepoort (Mpengesi, 2020)

193.90 thousand

0.71

566.86 thousand -Population

-Households

-Gini Coefficient Ration

133.36

116.47

18.70

30

14393.17 -Black African

-White

-Coloured

-Indian/ Asian

“It was imperative for the community to start improving their own lives in partnership with the state.”

-Andrea Bolnick

Andrea Bolnick, in collaboration with Upgrading Informal Settlement Programme (UISP) that supports insitu developments and relocation in unavoidable to access basic services and acquire tenure security. The blocking-out project in Ruimsig informal settlement includes 396 shacks with 422 families [4], that numerous stakeholders that were involved advocated for the settlement to remain. Legal transfer of the settlement was between City of Johannesburg and Mogale City municipalities to allow fair state intervention in spatial layouts establishments. Thus, becoming key urban actors and a firm voice for the dwellers. Bolnick concludes that the partnership and understanding housing politics assists the initiatives aimed at helping the urban poor [2].

Zandspruit and Princess informal settlements cases have evidently emphasized the juxtaposed cases in conjunction to the different roles of local government and municipalities that have played that guarantees land and housing security for the vulnerable dwellers. Residents of Princess informal settlement continue struggle with service from the local further deteriorating through its infrastructures and socio economic standing and continuing to place them in poor living conditions. Private property owners of neighbouring areas feel threated about the settlement’s rapid growth, and fear that it may encroach on their family plots [1]. Furthermore, the residents have threated to occupy the owner’s places as a form of strengthening their voice and getting attention from various actors, including the government. Residents have filed several to the government, yet the state claims their unawareness to the disheartening situation.

Cases such as Princess force residents to take the politics of governance into their hands to ensure their basic necessities are satisfied. Other stakeholders have aided in the face of adversity include local schools, political parties and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Despite the fact that these cases have the same actors of governance, the response in each have shown great distinctiveness. The varied perspectives of affected stakeholders, as well as interventions -or lack thereof - raises the question of classism in South African society. Were Zandspruit dwellers considered to continue occupying the place to protect Ruimsig’s image and reputation, or was the act of strengthening their voices prompt the government’s willingness to assist vulnerable residents?

[1] Adegun, O. B. (2016). Informal Settlement Intervention and Green Infrastructure: Exploring Just Sustainability in Kya Sands, Ruimsig and Cosmo City in Johannesburg. University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, pp 1 – 266.

[2] Bolnick, A. (n.d). Transforming Minds and Setting Precedents: Blocking-out at Ruimsig Informal Settlement. Community Organisation Resource Centre and Ikhayalami, Good Governance Learning Network, pp 1 – 6.

[3] Bolton, C (2023). Private property in Princess threatened by informal settlement. Roodepoort Record. [Accessed 23 June 2023]. Available at: https:// roodepoortrecord.co.za/2023/06/23/private-property-in-princess-threatened-by-informal-settlement/

[3] Khanyile, S (2016). Map showing Ruimsig informal settlement and adjoining wetland. [Accessed on February 2016}. Available at: https://www. researchgate.net/figure/map-showing-ruimsig-informal-settlement-and-adjoining-wetland-Produced-by-samkelisiwe_fig2_325028046

[4] Nyamhuno, S. (2021). Livelihood Impact of Solar Home Systems: The case of Ruimsig Informal Settlement in Gauteng. University of Free State, pp 1 – 122. [5] Rakuba, W. M. (2011). The Traumatic Effects Of Rapid Urbanization In The New South Africa After The 1994 Dispensation, A Challenge To Pastoral Counselling, With Particular Reference To Informal Settlements In The Roodepoort Area. University of Pretoria, Pretoria, pp 1 – 30. [6] City of Johannesburg, (2009) Zandspruit Urban Development Framework 2020. Maluleke Luthuli and Associates, Parktown West. [7]https://www.quantec.co.za/

Figure 15: Zandspruit informal settlement (Zandsrpuit UDF, 2020)

31

Figure 20: Zandspruit Development Framework (Zandsrpuit UDF, 2020)

Colonialism and Apartheid spatial planning in conjunction with rapid urbanisation has only catalysed the copious amounts of spatial and social inequalities in modern day South African town and cities [1 & 4]. Both regimes utilise spatial planning as an instrument for destruction, unequal resource allocation, oppression and enforcement of bias urban, economic and social development. This has had an undeniably unfortunate impact on the lives for previously disadvantaged groups. Today, these groups have been ‘othered’ – pushing them further into the abyss of marginalisation. Some of their reactions to this injustice – establishing informal settlements, occupying land that is not legally under their ownership or standing together in protest to attain the attention of the state in their grievances amongst other demonstrations of expostulation – has only added to their constant criminalisation.

Who should be CRIMINALISED

SWANEVILLE: ANOTHER

“KE BONE BOPHELO BO KE BO PHELANG BO.” - CONNIE MOKGOSI

WRITTEN BY: BOITSHOKO ORATILE SEBAKELWANG

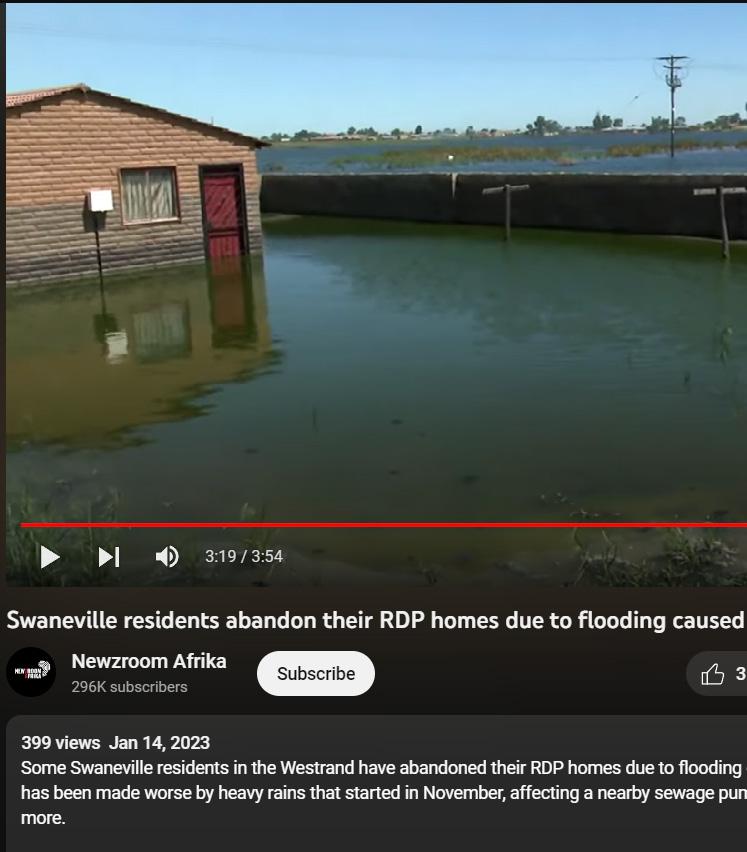

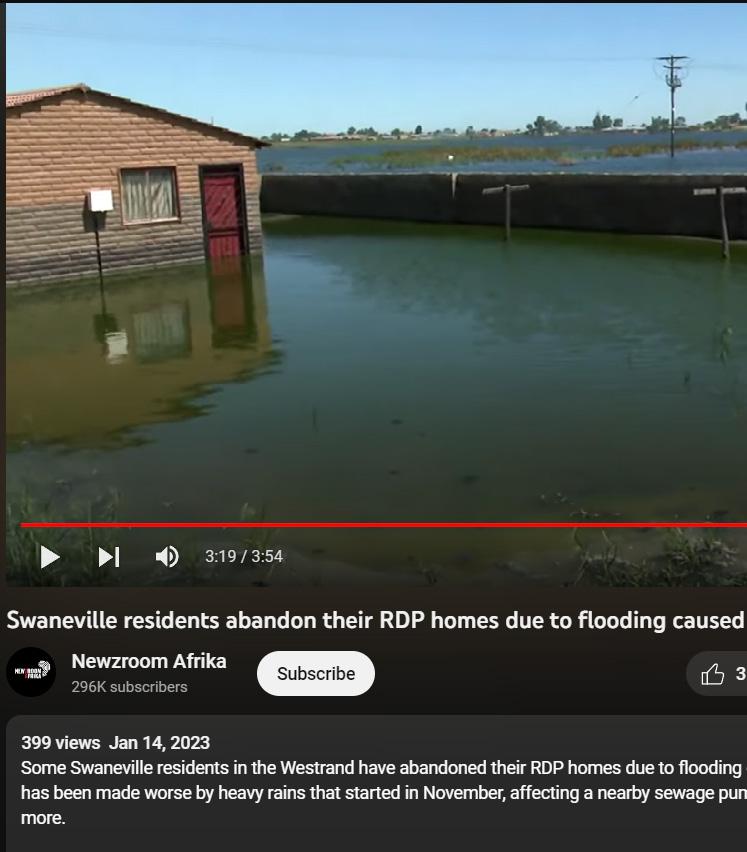

For many, the failures of the state to fulfil their promise have left them having to fend for themselves. We shift our focus to a relatively new and rapidly growing informal settlement in Swaneville, located on the southern border, where Region C of the City of Johannesburg meets the West Rand municipal District. The settlement has been developed on what one would assume is privately owned land or land in the custodianship of state and is on the edge of Roodepoort Main Reef gold mine and another mine dump – and surrounded by several other mine dumps. The growth of the settlement was met by government intervention by establishment of RDP housing in 2008 (REF). Problem solved, right? Wrong. The subsidised housing did not accommodate for everyone in the growing community – as a result we see the continued expansion of the settlement.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TM4oBPqxlxY

Informal Settlement in Swaneville. (Sebakelwang, 2023)

32

Flood Crisis in Swaneville. Newsroom Afrika, 2023)

Demonstrations of resistance to the circumstances that have been imposed on them during and since the ‘end’ of these regimes in present day South Africa – almost 30 years after the adoption of democracy and the Constitution (1996) of the South African state. A state that is entrusted by the people who elected it to advocate for the prioritise their rights. In this regard, the state has doubtlessly failed them in innumerable circumstances. The nonfeasance of state in delivering basic services, housing and employment opportunities in addition to other promises has robbed the people of experiencing truly integrated and sustainable cities that address the injustices of passed regimes and bring to fruition the desires of the people. This begs the question,

, the people or the state [?]

TRAGEDY OF THE COMMMONS

(SWANEVILLE RESIDENT)

In February of 2023, Swaneville homes had almost been devoured by dust, sewerage and acid mine water from the nearby mine dumps, that was flooding the area and residents’ homes. The residents of took to the streets, chanting “Bheki, Bheki, Bheki” protesting in a bid to get the attention of the state, pleading for local government of Mogale City to have their community relocated from this site (that was detrimental to their health), as it had not been the first time they experienced this and they feared it would not be the last. They called for the mining companies to be held responsible for the environmental issues and for officials of local authorities to intervene. Reportedly, even after the community had to be faced with such devastating realities, their pleas had fallen upon deaf ears. The people of Swaneville only have the promises made by the African National Congress to fall back on as a glimmer of hope for some but for others, it is just another unfulfilled promise made by a state that has proven their lack of dependability and trust countless times already [2 & 3].

[1] Bradlow, B., Bolnick, J. and Shearing, C., 2011. Housing, institutions, money: the failures and promise of human settlements policy and practice in South Africa. Environment and Urbanization, 23(1), pp.267-275.

[2] du Plessis, C. (2019). Ramaphosa promises to address Swaneville housing problems. [online] ewn.co.za. Available at: https://ewn.co.za/2019/04/14/ramaphosa-promises-to-address-swaneville-housing-problems [Accessed 7 Jan. 2023].

[3] Newsroom Afrika (2023). Swaneville residents abandon their RDP homes due to flooding caused by suspected mine dam water. [online] www.youtube. com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TM4oBPqxlxY [Accessed 7 Jun. 2023].

[4] Reddy, D.T., 2015. South Africa, settler colonialism and the failures of liberal democracy. Bloomsbury Publishing.

MOKGOSI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TM4oBPqxlxY

33

Aerial Photograph of Swaneville. (ArcGIS, 2023)

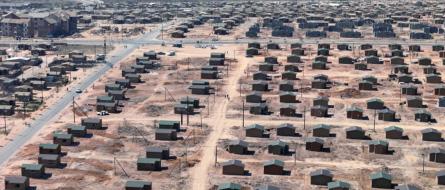

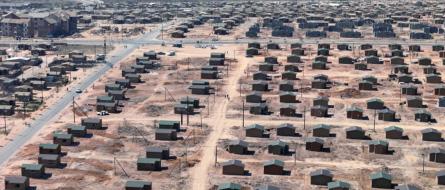

COSMO [CITY]?

The state-hailed residential development has received much acclaimin several circles. But can we call the rapidly developing multi-class urban area a city?

WRITTEN BY: SANKARA GIBBS

Cosmo City, situated on the outskirts of Johannesburg, South Africa, represents a fascinating case study of urban development in a postapartheid context. This article critically examines the extent to which Cosmo City can be regarded as a fully-fledged city, the repetition of historical spatial patterns within its layout, and its progression towards fostering inclusivity. By referencing academic articles on peripheral urbanization [1] and low-income housing in South Africa, this analysis aims to shed light on the complex dynamics shaping this evolving urban landscape.

Cosmo City: A City in Name or Substance?

Cosmo City’s designation as a “city” raises questions about the criteria by which urbanity is defined. Scholars such as Simone Puleo (2018) argue that peripheral urban developments, like Cosmo City, often lack the functional attributes and

infrastructure associated with traditional urban centers. These areas might resemble cities in appearance but often fall short in terms of comprehensive urban amenities, transportation networks, and economic opportunities.

Repetitive Spatial Patterns and the Ghosts of the Past:

Cosmo City’s spatial layout raises concerns about the perpetuation of historical inequalities. The legacy of apartheid-era spatial planning is evident as the community is physically isolated from established urban centers. Drawing from the work of Todes and Huchzermeyer [2], the article can highlight how such patterns can lead to exclusion, inadequate service delivery, and a lack of access to economic opportunities for marginalized populations.

Low-Income Housing and Inclusivity:

While Cosmo City represents

an effort to provide lowincome housing, questions arise regarding the extent to which it is truly inclusive. Analyses by Bénit-Gbaffou and Parnell [3] emphasize the need for more comprehensive approaches to low-income housing, addressing not only physical housing needs but also broader social and economic integration. The article could examine whether Cosmo City effectively fosters social cohesion and upward mobility or inadvertently perpetuates a cycle of marginalization.

Towards a More Inclusive City:

Cosmo City’s evolution towards inclusivity is a complex process. Drawing insights from Gupta and Space [4], the article can explore the role of participatory planning in ensuring that residents have a voice in shaping their environment. It’s important to assess the degree to which the community is engaged in decision-making processes, and whether the

34

Image of a residential development under construction in Cosmo City. (Goldblatt, 2009)

development is responsive to the diverse needs of its residents.

The case of Cosmo City illustrates the multifaceted challenges and opportunities inherent in peripheral urbanization and low-income housing in South Africa. As

scholars emphasize, the mere physical appearance of a city does not guarantee urban functionality or inclusivity. By critically examining Cosmo City’s trajectory through the lenses of historical spatial patterns and academic insights on low-income housing and peripheral urbanization, this

article aims to contribute to a nuanced understanding of its development. In the pursuit of inclusivity, Cosmo City serves as a reminder of the need for comprehensive planning, community participation, and a holistic approach to urban development.

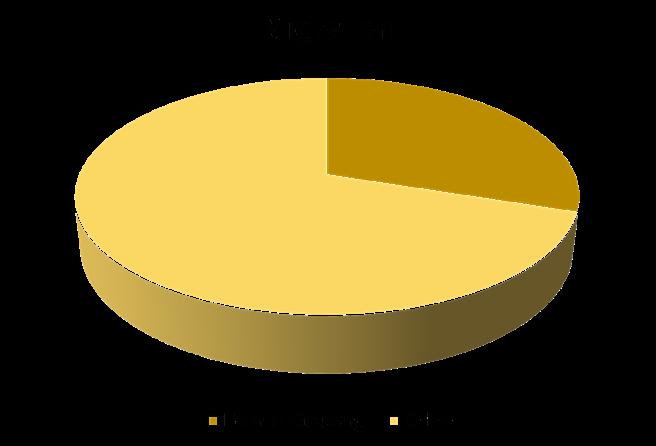

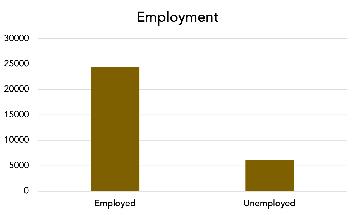

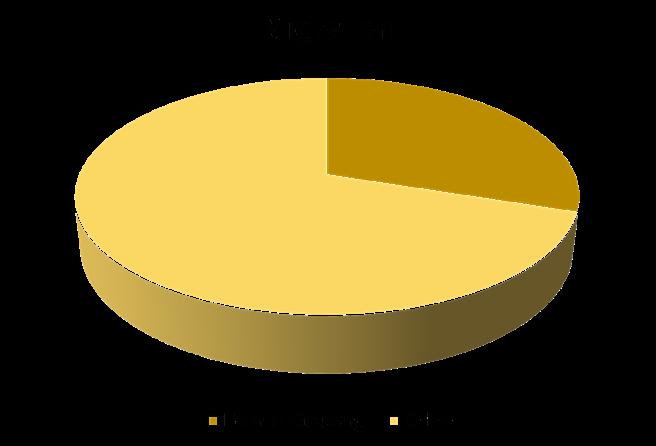

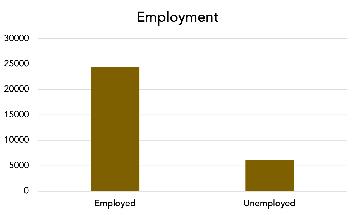

Cosmo City Statistics

20.4 sqkm

Area of Cosmo City, South Africa

90,859

Population

+57.2%

Population change from 2000 to 2015

27.1

Median Age

[1] Puleo, S. (2018). Peripheral urbanization revisited: A new conceptualization of an old phenomenon. Cities, 77, 138-147.

[2] Todes, A., & Huchzermeyer, M. (2015). The “big bang” failure of housing policy in post-apartheid South Africa: People’s preferences and the location of state-sponsored houses, 1994–2009. World Development, 74, 253-262.

[3] Bénit-Gbaffou, C., & Parnell, S. (2012). Informal spaces: The geography of housing in post-apartheid South African cities. Geoforum, 43(4), 815-824.

[4]Gupta, V., & Space, L. (2019). Community engagement and urban transformation: Cosmo City, Johannesburg. Cities, 94, 164-172.

[5] Cosmo City Picture 1: Goldblatt, D. (2009). David Goldblatt | Cosmo City. 15 August 2009 (2009) | Available for Sale | Artsy. [online] Artsy.net. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artwork/david-goldblatt-cosmo-city-15-august-2009 [Accessed 24 Aug. 2023].

35

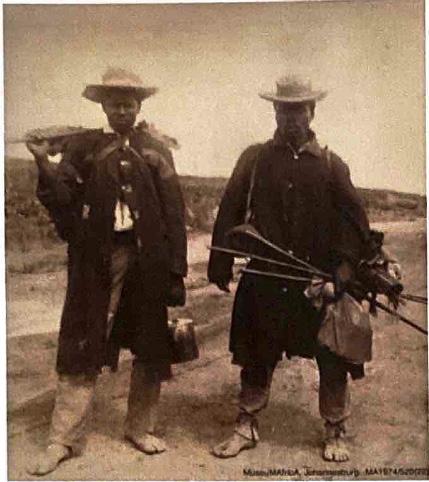

The Wild West Rand

Urban planning as a tool for domination, segregation and oppression in Johannesburg’s western mining towns

WRITTEN BY: SANKARA GIBBS

The wild, untamed landscapes of the American frontier, often referred to as the Wild West, evoke images of rugged individualism, lawlessness, and the struggle for survival. Parallels can be drawn between this era and the history of the West Rand region in Johannesburg, South Africa. The West Rand, a onceuntamed land, became a theater for the manipulation of urban planning as a tool for domination, segregation, and oppression. This article delves into the historical roots of the West Rand, its mining legacy, and how urban planning was wielded during colonialism and apartheid to shape the social fabric and perpetuate inequality.

Mining Heritage of the West Rand

The West Rand, situated on the outskirts of Johannesburg, boasts a rich history intertwined with mining. The discovery of gold in the late 19th century transformed the region into a magnet for fortune seekers and entrepreneurs. The exploitation of its mineral wealth ignited rapid urbanization, sparking the rise of towns like Krugersdorp, Roodepoort,

and Randfontein [1].

Urban Planning as a Tool for Control