Funding, Governance, Collections, Archives, Education, Third Places, Relevancy, Pillars of Democracy

Funding, Governance, Collections, Archives, Education, Third Places, Relevancy, Pillars of Democracy

Inside the Friends of the Library sorting room

Local history: Author Lori Johnson retraces her Black roots in old Whitehaven Books! Book talk, what branches are reading, an old blockbuster revived

MPL UNBOUND (ISSN 3065-503X) is a publication of the MEMPHIS LIBRARY FOUNDATION

3030 Poplar Ave, Memphis, TN 38111

To support the Memphis Public Libraries, scan the code at right, visit memphislibraryfoundation.org/donate, or email us at: unbound@memphislibraryfoundation.org

THE MEMPHIS LIBRARY FOUNDATION IS RECOGNIZED BY THE INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE AS A PUBLIC CHARITY WITH NONPROFIT STATUS, REGISTERED AS A TAX-EXEMPT CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION IN THE STATE OF TENNESSEE.

©2024 MEMPHIS LIBRARY FOUNDATION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Using your mobile device, scan the QR code above to make a tax-deeductible donation to the Memphis Library Foundation

The city funds the cost of library operations like staff salaries & benefits, building maintenance, & security; private donors make our awardwinning library programming possible. The Memphis Library Foundation was founded in 1995 to secure private and corporate donations to fund our innovative and community-centered work at the libraries.

Above: The Memphis Periodical Index filing cabinet. Located in the Memphis Room on the 4th floor of the Benjamin L Hooks Central Library, the cabinet contains the catalog and locator cards of all the newspaper and magazine clippings available for research on the topics listed. Organized alphabetically by topic, each card displays the topic, the topic description, the publication title, the publication date, and the volume and issue number of the periodical.

MPL EVENTS

The library is so much more than books. In our Events section, check out upcoming events, with links for all.

A.I. AND THE LIBRARY

Artificial Intelligence is here. How the library is working with it, and with what kinds of guard rails.

FEATURE: THE LIBRARY

HOW THE LIBRARY WORKS

The Library. Still among the most trusted of institutions, a community anchor, a pillar of democracy. But, how does it work? And, why does it continue to ‘work’?

HISTORY DEPARTMENT

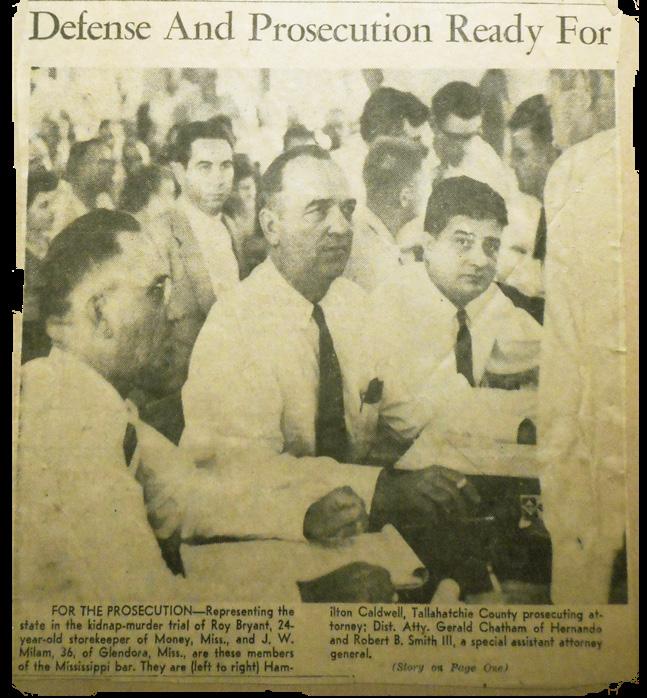

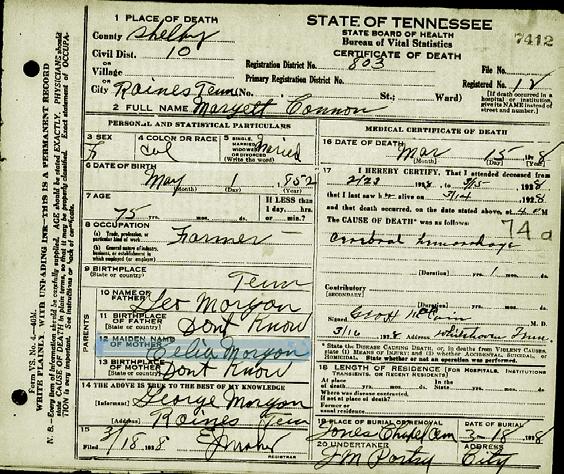

RETRACING HER WHITEHAVEN ROOTS

Lori Johnson takes readers on a personal tour of a family discovery and a dive into her Whitehaven roots.

ESSAYS

VISUALS: ALCHEMY, A DONATED BOOK

Inside the Friends of the Library sorting room; books’ journeys from donation to the Second Editions Bookstore

THE LIBRARY

Robert A. Lanier and Susan Cushman share their love and work with the Memphis Public Libraries

BOOKS

WHAT WE’RE READING

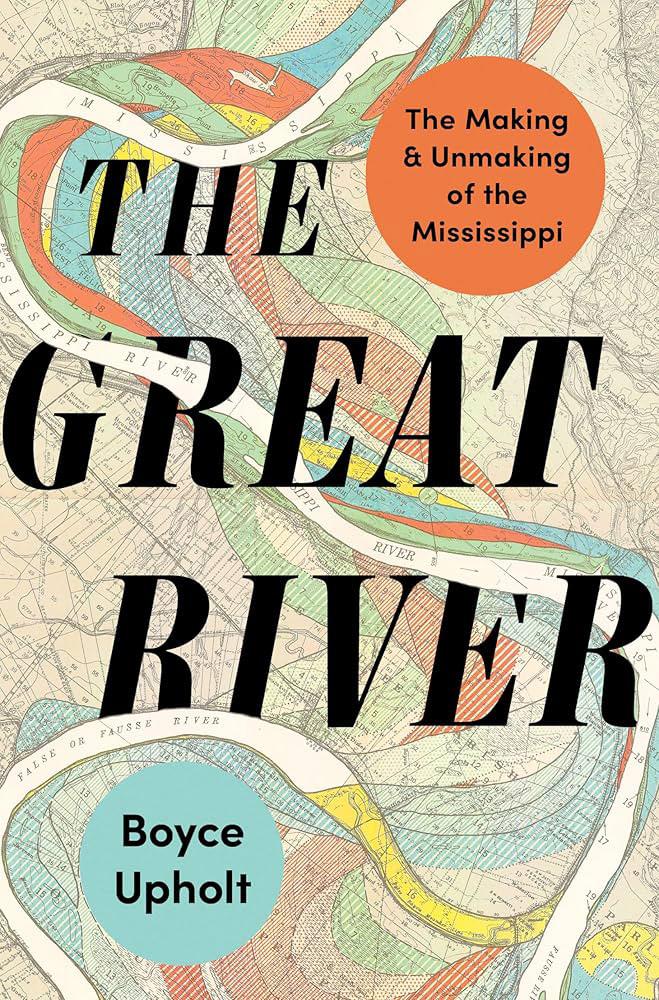

Guess what? Library staff are kinda into books, of all kinds and sizes. Here’s what some of them are reading.

OVERHEARD AT THE EDITORIAL DESK

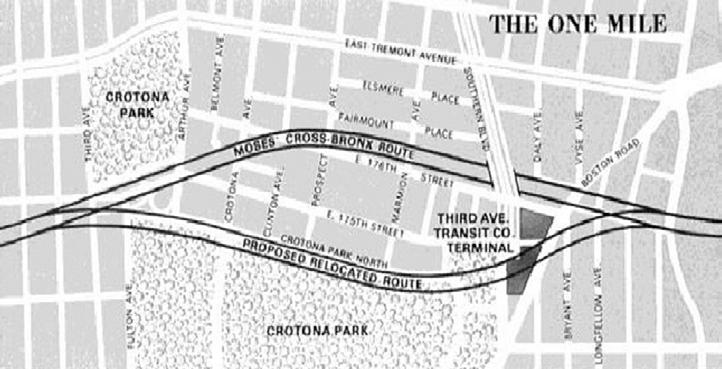

Two editors discuss the resurfacing of Robert Caro’s landmark biography about city planner Robert Moses.

CHECKOUT: THE THIRD PLACE

If you have visited a library recently you won’t be surprised at who you will find there.

Suspended in the four-story lobby of the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library, architectural artist Ed Carpenter’s spectacular “light canvasses” structure of dichroic glass reflects sunlight throughout the lobby. At times, its radiance seems to rival the brilliance of the sun itself, creating a veritable curtain of light. During the evening hours, it is lit to create a rich atmospheric effect that is as engrossing to the eye as it is during the daytime. Memphis photographer Jamie Harmon captured this image one summer evening at dusk, exclusively for MPL UNBOUND’s inaugural issue.

Welcome to the first-ever edition of MPL UNBOUND, a magazine dedicated to the stories, people, and vision that make the Memphis Public Libraries (MPL) pillars of imagination and transformation. At the Memphis Library Foundation, our mission is to raise awareness and funds for MPL to go far beyond basic library services, equipping the 18 local branches to respond dynamically to the evolving needs of our diverse city. In these pages, you’ll find stories that illustrate how libraries are not only places of learning but also hubs of connection, innovation, and community empowerment.

Libraries today are more essential than ever. While books and quiet reading spaces remain important for many library patrons, libraries have adapted (and continue to adapt) to the changing needs of 21st-century Memphians. From offering digital media labs and career workshops to serving as safe, inclusive spaces for people of all ages, libraries are at the heart of communitybuilding. MPL connects families to educational programs, students to the most up-to-date resources, job-seekers to critical training, and seniors to digital literacy tools. This magazine celebrates MPL’s innovative spirit and the positive ripple effects of our growth across our city. In this magazine, you’ll read about exciting new projects at MPL that are made possible by the support of donors and advocates like you. You will peruse pieces ranging from personal book reviews written by your beloved staffers to deep historical analyses drawn from information found in the MPL archives. The central story undergirding this inaugural issue highlights what our public libraries mean to Memphians. As a third place, MPL branches provide a home away from home for little kids fumbling through picture books, teenagers sneaking glances at their young loves in the stacks, the unhoused looking for a safe place to relax, the retired couple looking for new hobbies to explore, the aspiring entrepreneur exploring how to turn their passion into a careerin a word, MPL is for everyone.

As you turn each page, know that the achievements you see here are only possible because of community members who believe in the power of libraries. Whether you’re a longtime supporter or new to our mission, we invite you to explore the ways you can make a difference through the Memphis Public Libraries. Each donation, volunteer hour, or word of advocacy amplifies our libraries’ ability to serve and uplift all Memphians.

Thank you for joining us on this journey. Together, we are transforming lives, strengthening our city, and allowing future generations to imagine more for themselves and for Memphis.

~Warmest regards,

Christine Weinreich Executive Director Memphis Library Foundation

There has always been the library. My high school had a great little library - this was early-1980s California - an indoor roundhouse in the center of our humanities building, with floor-toceiling windows. The entire space was sunken a couple of steps down, like the conversation pits in 1960s & ‘70s living rooms, and just as comforting. It was often empty. Maybe a student or two, and the quiet bespectacled librarian behind the front desk. But it was well-stocked, which always surprised me, with rows of shelves lined with thousands of books waiting to be opened and read. It often felt like my own private sanctuary, a place to escape from the hustle of being a teen who didn’t quite fit into any single group. My high school resume was just enough sports and smarts for college prep, and hanging out with guys like me. We didn’t belong with the jocks or the geeks, and we weren’t the class clowns. But we loved learning, and our teachers loved us. Thus we were summarily disdained by everyone, the jocks and the geeks and the clowns alike (the smokers were somehow ok with us, go figure).

But I was happiest in the library, and the most at home, hanging out with wonderful stacks of books and occasionally sharing a few adult thoughts with the librarian. I always walked away from her thinking that she was the smartest person in the school, and yet the most invisible.

Midway through our senior year, when we were all anxious for adulthood, a ratty little freshman started crossing our path. A punk of a kid, always disheveled, and always talking smack from his bicycle, he annoyed everyone. And as we used to say, he was just asking for it.

One day we heard that a group of seniors had gone after him after school. We later learned that he had pissed off the wrong jocks, managed to evade them, and had found safety, crying and hiding, in a far corner of the library.

We felt awful. None of us knew his story, nor anything of his life at home, but we knew it couldn’t have been good. And while finding refuge in the library made perfect sense, at the time we did not see anything symbolic in an outcast being rescued by books and the librarian behind the glasses.

This September Southern writer Margaret Renkl wrote a New York Times story about librarians as superheroes, and Louisiana librarian Amanda Jones, who in recent years has been targeted by extremists for speaking in defense of diverse books. No self-proclaimed superhero, Ms. Jones says she speaks out as a “defender of wonders.”

When we imagined this magazine’s purpose, people like Ms. Jones and that poor freshman came to my mind, because the library - especially now in this new era of unknowns - still provides so much of what we love, cherish, and need. It is a reliable, free source of knowledge and hope. It is a safe, warm sanctuary for all. We hope this publication provides the same.

~

Mark Fleischer Chief Editor & Connect Crew Specialist

THE LIBRARY IN YOUR MAILBOX

Library supporters who give at least $25 per month or $250 annually to support the Memphis Public Libraries receive UNBOUND by mail each quarter. Scan the QR code or visit memphislibraryfoundation.org to donate today!

Scan this code to submit content or letters to the editors FOR CONSIDERATION. Storytellers may submit works of short or feature-length nonfiction, short fiction, book reviews, poetry, photography, artwork, etc. Letters to the Editor should be 175 words or less. For more details, see page 31.

PIECES

The library saved my life. Spat out of university with a college degree and no job, no purpose, and not even knowing who I was, I fell into disrepair. I didn’t know what to do. So I read. Then, when the books weren’t enough, I volunteered at the library. Before I knew it, I was hired and started using my skills and passions to create programs. I tried to help those around me by sharing the skills I loved in the communities of Memphis. Even as an employee, I explored everything the library offered to its patrons, finding pieces of myself along the way. There’s nothing quite like knowing the library had acknowledged, accepted, and provided for me and people like me before I even set foot inside. I kick myself every day for not coming sooner. Which is why I came to work on UNBOUND, so that those of you who read it can find pieces of yourself reflected within its pages—so that you are brought to the library, which offers something for everyone.

Rebecca Stovall, Co-Editor & Connect Crew Specialist

Welcome to UNBOUND!

I welcome the opportunity to work on this magazine. It combines two of my passions-writing and libraries. I find myself in a room with library staffers who share my enthusiasm for the library and this magazine. The people creating the stories and visuals are people like me who love both libraries and storytelling. UNBOUND showcases MPL’s response to the world we live in today. This magazine will highlight the services and activities the library branches offer. UNBOUND will expose readers to creative content that helps us enjoy life without stressing about it.

When facing stressful times and juggling feelings of despair and uncertainty, there is nothing more reassuring than the written word. In reading we find solace. UNBOUND intends to be a balm for MPL staff, supporters, and customers. Regardless of your feelings, you will discover something soothing within the pages of UNBOUND.

Reading UNBOUND will give people a view of the library as seen through the eyes of those who came to the Library system by many paths, but stayed because our love for books, libraries, and writing keeps us bound to it.

Enjoy. ~Juanita White

SUBMITTING CONTENT FOR CONSIDERATION

MPL UNBOUND accepts submissions from local, Mid-South storytellers or those with ties to Memphis and the Library. Storytellers may submit a variety of works, including book reviews, poetry, photography, and artwork. Letters to the Editor should be 175 words or less. Use the QR code on the facing page or visit memphislibrary.org. See page 31

When I first heard the idea of a library magazine, I was desperate to be involved. The library has supported me through every major stage in my life, even before I could read or talk. If you know a librarian, you’ll know that they’re hooked on the library - promoting our seed library at parties, telling family about our genealogy resources, even cornering friends to sign up for a library card. But I am continually shocked by how few people in Memphis use the library. To me, UNBOUND is a publication that can meet Memphians where they’re at, bringing the resources and essence of the library to wherever they need it. I strongly believe in equitable access to education, information, and community, and there is no better place to find it than the Memphis Public Libraries. The library is one of the only places that is truly for everyone, no matter your background. As you flip through the pages of our inaugural issue, I hope you feel the love and intention from our editorial team, our library staff, and everyone who supported this project. Thank you for reading and for loving your library. Your library loves you back.

~Emma Pennington

I have wanted to write ever since my mother, who is a retired private school teacher, put a pencil in my hand. To keep me from annoying her while she was a stay-at-home mom, she taught me how to read and write when I was 3-4 years old. Trips to the local library were much more fun than going to the fabric store or grocery store.

I guess since both of my parents read, it was obvious I wanted to read. There was never a push on Math or Sciences, so I always leaned toward English and Literature classes in high school. In fact, I have a degree in Creative Writing. I tell people I have a BA in BS. Trips to the library and actually working for MPL is still more fun than trips to the grocery store. Writing for a magazine has been something I have wanted to do for a while. I am proud to be part of the Editing and Writing team for UNBOUND. Just as I enjoy learning and contributing snippets of my life, I hope you will learn and contribute snippets of yours. Everyone has a story. What’s yours?

~Andrea Bledsoe King

Libraries, fundamentally, are about access. Access to information, access to technology, access to experiences. Most of us spend thirteen to fourteen years attending school, maybe more if we choose, but K-12 schools are limited by time, funding, and other responsibilities. Librarians have the freedom to interact with patrons one-on-one. Instead of a fifty-minute lecture, we can bring in an expert who will demonstrate the real-life applications of what you’re learning. We help you do your taxes and fill out job applications. We teach yoga and robotics. We show you how to use your phone and how to make something on a 3D printer. Thanks to the funding we receive from the Memphis Library Foundation, our only limit is our creativity. This magazine is a natural extension of what we do: we are providing information, we are giving the citizens of Memphis a new, free experience, and we are opening a dialogue. Who are you, reader, and what would you like to see next at your neighborhood library? The librarians here won’t shush you: we’re listening.

~Sara Priddy

Psychologists theorize that our earliest memories reflect aspects of ourselves, of what is important to us now. It’s fitting, then, that one of my earliest memories is of walking through a colorful forest into the brand-new Children’s Department at the brand-new Benjamin L. Hooks Library. The public library has always held a special place in my heart. As an institution, we exist to serve the public. We provide information, technology, books (of course), and a place to sit and rest your head - free of charge. A noble mission, yes? And it’s one that I’m proud to serve, especially in these uncertain times. Even so, I know that we can do more; that we can be more. That’s one of the main reasons I volunteered to work on this publication – a magazine where you can catch up on local events, get book recommendations, read stories and poems and essays by and for Memphians, and learn about what your library is doing for you. This magazine is for you, because we cannot exist without you. I hope you enjoy what we’ve put together, and I hope to read your own contributions soon. ~Marty Synk

As Style and Design Editor, my contribution to the production of MPL UNBOUND allows me to indulge one of my greatest passions: the interaction of word and image. I have a degree in art history, but more than that, I just love to look, and I will admit I’m pretty good at it. In a printed publication, good design facilitates good communication because it is nice to look at. I have been fortunate to work with all kinds of books, including many that were old, rare, handmade, or sometimes so artfully crafted as to hardly resemble a book! These experiences broadened my conceptions of what a print publication could look like, how it could function, and how good design unites words, graphics, and imagery. I am grateful to use what I’ve learned - with other talented editors and creators - on a project that reflects the vibrant culture of Memphis through the lens of the Library. There is no question that the MPL is an anchor for Memphis’ many communities, a place that brings us all together for countless reasons. The Library is a hub of informational and social exchange, and MPL Unbound will serve as a conductor of both. ~David Christie

Epistolary novels have always been some of my favorite books to read. Telling a story through personal letters allows a reader to get lost in the intimacy of the language, the personal thoughts that were meant for no one else to see, the anguished plea or the elusive tone. Whether a war-time missive home to a sweetheart or an angry email to a prodigal relative, letters reveal; letters are open-faced insight. This letter is no different.

UNBOUND is a love letter. A love letter to Memphis, to the libraries that sit in her neighborhoods and stand on her corners. To you, the MPL UNBOUND reader, its pages relay not only what library life is like for those of us who work here every day, but also how the library makes every life more rich and better connected. We hope by laying bare who the library is, what it does and how it works, you will know us better and find yourself in these pages and in the stacks.

~Beth Thorne

Bookstock is the largest annual local authors festival in Memphis, with up to 60 local authors joining in for networking, author talks, local entertainment, and more. Interested authors should visit the Memphis Public Libraries website (memphispubliclibrary.org) and go to

the BookStock link to fill out the 2025 Bookstock Application form in the website. Email the form to Alexandra Farmer (Alexandra. Farmer@memphistn.gov) and copy (cc) Wang-Ying Glasgow (Wang-Ying.Glasgow@ memphistn.gov).

HOLIDAY CONCERT WITH KENNETH JACKSON INFO IN EVENTS, FACING PAGE DEC 20 FRI

Cossitt Library: 33 S. Front Street, 38103; (901) 415-2766

Cornelia Crenshaw Memorial Library: 531 Vance Avenue, 38126; (901) 415-2765

Gaston Park Library: 1040 South Third Street, 38106; (901) 415-2769

South Library: 1929 South Third Street, 38109; (901) 415-2780

Levi Library: 3676 South Third Street, 38109; (901) 415-2773

Frayser Library: 3712 Argonne Street, 38127; (901) 415-2768

Raleigh Library: 3452 Austin Peay Hwy, 38128; (901) 415-2778

Hollywood Library: 1530 North Hollywood Street, 38108; (901) 415-2772

North Library: 1192 Vollintine Avenue, 38107; (901) 415-2775

Randolph Library: 3752 Given Avenue, 38122; (901) 415-2779

Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library: 3030 Poplar Avenue, 38111; (901) 415-2700

Orange Mound Library: 843 Dallas Street, 38114; (901) 415-2761

Cherokee Library: 3300 Sharpe Avenue, 38111; (901) 743-3655

Whitehaven Library: 4120 Mill Branch Road, 38116; (901) 415-2781

The Library in Your Hands

MPL UNBOUND, a Publication of the Memphis Library Foundation

Publisher: CHRISTINE WEINREICH Executive Director of the Memphis Library Foundation (MLF)

Associate Publisher: RACHEL MATTSON Director of Development & Communications MLF

Chief Editor: MARK FLEISCHER Connect Crew Specialist

Co-Editor: REBECCA STOVALL Connect Crew Specialist

Associate Editors: ANDREA KING

EMMA PENNINGTON

SARA PRIDDY

MARTY SYNK

BETH THORNE

JUANITA WHITE

Style & Design Editor: DAVID CHRISTIE

Officer Geoffrey Redd Library: 5094 Poplar Avenue, 38117; (901) 415-2777

Parkway Village Library: 4655 Knight Arnold Road, 38118; (901) 415-2776

East Shelby Library: 7200 East Shelby Drive, 38125; (901) 415-2767

Cordova Library: 8457 Trinity Road, 38018; (901) 415-2764

Graphic Design, Layout: SERAH DELONG SerahWorks

Special Masthead, Type Design: REBECCA PHILLIPS Dribbble.com

Photographer for Inaugural Edition: JAMIE HARMON Photographer, Amurica

Operations: MOLLY PEACHER-RYAN Director of Operations & Donor Strategy MLF

Regular Contributors: WAYNE DOWDY

The Memphis & Shelby County Room

STEPHEN USERY

WYPL Program Manager, Host of Nationally-Syndicated Show BookTalk

JAMIE GRIFFIN Featured Contribution

SCAN FOR ALL MPL EVENTS

DO YOU WANT TO BECOME A US CITIZEN?

5 - 6pm • Cordova Library Ages: Adults

Prep for the Citizenship exam

Contact: Karol Hogan email: Karol.Hogan@memphistn.gov phone: 901.415.2764

THE MOVABLE COLLECTION ARTISTS SPOTLIGHT

2 - 3pm • Whitehaven Library Ages: Teens, Adults

Memphis artists whose work is on display in the Whitehaven branch will present workshops for teens and Artist Talks for all ages.

Contact: Branch p: 901.415.2781

AARP SENIOR GAME DAY 12 noon - 5:30pm • North Library Age Group: Adults

Relax with friends during an afternoon of fun and games.

Contact: Vanessa Luellen p: 901.415.2775

DECK THE HALLS: ORNAMENT PAINTING 4:30 - 5:30pm Orange Mound Library Meeting Room OM Ages: All

Get creative and personalize your own festive ornaments.

Contact: Nyale Pieh e: nyale.pieh@memphistn.gov p: 901.415.2761

POSITIVE SOLUTIONS FOR FAMILIES CLASSES TN VOICES* Every Wednesday 12 noon - 1:30pm Orange Mound Library, Room OM Ages: Teens, Adults

Positive Solutions for Families (PSF) is an evidence-informed seven-part series for parents and caregivers of young children. Participants will learn how to use positive approaches and effective techniques to improve interactions with their child(ren). These tools will promote optimal development and will address challenging behaviors.

1/15 Session 1: Making a Connection 1/22 Session 2: Keeping it Positive 1/29 Session 3: Behavior Has Meaning 2/5 Session 4: The Power of Routines 2/12 Session 5: Teach Me What to Do! 2/19 Session 6: Responding With Purpose 2/26 Session 7: Bringing it All Together

WHITEHAVEN LIBRARY ANNUAL BOYS COAT DRIVE

3:30 - 5:30pm • Whitehaven Library Meeting Room WHI Ages: 6-12, Teens

Whitehaven Library’s 4th Annual Boys Winter Coat Drive

Contact: Tanishia Jennes-Turner e: tanishia.jennes@memphistn.gov p: 901.415.2781

GATHERING PRESENTS: UNDUGU II

3 - 5pm • Levi Library

Join us for a live hip-hop music event focused on local Memphis artists. The lyrics will be clean and friendly for All ages.

Contact: Courtney Shaw e: courtney.shaw@memphistn.gov p: 901.415.2871

SANTA CLAUS IS COMING TO TOWN

12 noon - 2pm • Cheroke Library Meeting Room CHE Ages: Children 0-8

Santa will visit the children of the Cherokee Library.

Contact: Kitty Baker e: kitty.baker@memphistn.gov p: 901.415.2762

Event sponsored by Friends of the Library

Event sponsored by the Memphis Library Foundation

DEC 18 WED

FREE TECH SUPPORT AT THE LIBRARY (AVAILABLE IN FOUR LANGUAGES)

2 - 3:30pm Cordova Library, Room COR Ages: Adults

Help with your phone, laptop, tablet, email, photos, videos, etc.

Contact: Gretchen Wilwayco e: gretchen.wilwayco@memphistn.gov p: 901.415.2764

‘TIS A SOULFUL SEASON: HOLIDAY CONCERT WITH KENNETH JACKSON

2 - 3pm • Orange Mound Library Meeting Room OM Ages: Adults

Enjoy the soulful music of Kenneth Jackson as he ushers in the holiday season for the Orange Mound community. A very special holiday treat!

Contact: Skyler Gambert e: skyler.gambert@memphistn.gov p: 901.415.2761

WALK A MILE AND GET A FREE BOOK!

10 - 11am • Cordova Library Outdoor Grounds Ages: Adults

We are going to walk from the library entrance, complete the walking path around the Bert Ferguson community center (approx. 1 mile), and return to the library.

Contact: Gretchen Wilwayco e: gretchen.wilwayco@memphistn.gov

Contact: Skyler Gambert e: skyler.gambert@memphistn.gov p: 901.415.2761

*REGISTRATION REQUIRED. SCAN BELOW TO REGISTER:

FREE TECH SUPPORT AT THE LIBRARY (available in four languages)

2 - 3:30pm • Cordova Library Meeting Room COR Ages: Adults, Adult-Seniors

Need help with your phone, laptop, tablet, email, photos, videos, etc.?

Come to the library for free one-on-one tech support! Staff member Gretchen speaks English, Spanish, French and Tagalog, and will be happy to help you.

Contact: Gretchen Wilwayco gretchen.wilwayco@memphistn.gov

LIBRARY LOVE IS PERMANENT

12 noon - 8pm

Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library Ages: Adults

We’re excited to announce that Library Love is Permanent is BACK, just in time for Library Lovers’ Month! Looking to get some new ink and want to support the Memphis Public Libraries? We can’t wait to see you there!

Contact: Rachel Mattson Rachel@memphislibraryfoundation.org

Just like this new publication, the Connect Crew meets the community where they are.

Connect Crew is your local public library on wheels! Step foot on the START HERE van and find the programs, books, and resources you love, all wrapped up in a small team dedicated to expanding library walls throughout the city, and meeting our patrons where they are. You will find us delivering programs at local schools and community & retirement centers, story times at the zoo, museums, parks, and farmers markets, and setting up our mobile library at fairs, festivals, and neighborhood block parties, with library card sign-ups, free books, and more.

Upcoming programs include ongoing PorterLeath Storytimes for Pre-k every Friday (at alternating locations), and The Writer’s Block (Wednesdays 6-8pm Panera Bread in Laurelwood Shopping Center), a writing club that invites aspiring and experienced writers to gather and get past hurdles to putting words on the page.

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT CONNECT CREW

RIGHT AROUND THE CORNER FROM THE CENTRAL LIBRARY, PICK UP A COPY OF MPL UNBOUND:

STATE GRANT FUNDS REPLACEMENT OF CENTRAL LIBRARY ELEVATORS & ESCALATORS

The Memphis Public Libraries were awarded a Connected Community Facilities grant for $1,584,000 as part of Tennessee’s statewide digital opportunity investments.

MPL’s staff hosts thousands of programs for all ages and learning levels each year. Central Library building upgrades, including replacing the elevators and escalators and installing a self service kiosk on each floor, will ensure that these programs

are truly accessible for those with physical limitations. State of Tennessee support will allow MPL to reach more residents in a meaningful way so that the library can teach them marketable skills designed to help them reach career and education goals and connect them to mentors, networks, and additional resources to support their success.

LIBRARY FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES STATE GRANT TO EXPAND CREATIVE ENTREPRENEURSHIP PROGRAM

The Memphis Library Foundation was awarded a two-year grant of $300,510 from the Tennessee Department of Economic & Community Development to expand the Innovator-inResidence (IIR) Program at the Cossitt and Raleigh Branch Libraries. Piloted at Cossitt with podcaster Ena Esco, the program engages entrepreneurial creatives to provide classes, workshops, individual mentoring, and a myriad other resources to citizens interested in learning their craft. In exchange, Innovators receive library space and resources to grow their business.

Interested in becoming an Innovator? Applications will be available soon. Subscribe to the Memphis Library Foundation’s new Substack newsletter below to be kept informed:

THE MEMPHIS LIBRARY FOUNDATION IS NOW ON SUBSTACK

DON’T HAVE A LIBRARY CARD YET? A Library Card opens the door to our physical and online collections including over a million items in our 18 locations and over 50,000 e-books and e-audiobooks. You can also use it to reserve one of our public access computers.

The MPL family lost long-time Senior Manager of the Crenshaw and Gaston Park Branch Libraries Inger Upchurch suddenly on August 26th, 2024. Inger Upchurch was the community’s mom wherever she worked.

She will be remembered as a sweet, compassionate, loving, smart, talented, and caring person. This is a huge loss for all of the Memphis Public Libraries. All will grieve her passing. Inger was one in a million. She embodies what Memphis Public Libraries is all about through her service and dedication to the community, her spirit and her creativity.

SIGN UP FOR A LIBRARY CARD

RIGHT HERE!

By Samara Solomon

“Is it live, or is it Memorex?”

Readers of certain ages will likely recall that tag line from Memorex and their series of television commercials in the 1970s and ‘80s, produced for its line of blank cassette tapes starting in 1974. In a long-running ad campaign, it featured a film of the great Ella Fitzgerald singing a high note that shattered a wine glass, played back from a Memorex tape, that again shattered another glass.

The slogan became an everyday catchphrase, emblematic of an era when advances in media and technology were met with wonder and excitement, and spawned a nostalgia-filled generation of home recordings and mixed tapes. With the rise of Artificial Intelligence integrating itself into our work and lives across the nation, step by incremental step becoming a component of many people’s daily lives, it is filled with unknowns that instill both excitement and fear. Now we ask, skeptically, Is it real or is it A.I.?

And the technology, its usage and its own selfinduced flaws, are advancing rapidly. Questions abound, about its use in the arts, in medicine, in advertising, by writers, and as convincing stand-ins - copies - of very real people. It already peppers what we see on social media and just about anywhere we look.

Like the cosmos, its reach and its implications seem unlimited, and new studies, discoveries, and explorations appear daily. On the flip-side, in a mind-bending twist, recent studies have even identified ways that A.I. can “de-generate,” in effect degrade and distort itself in the process of extracting and re-extracting information from its own generated images and information. As one example suggested, imagine an original drawing that is photocopied – a copy of a copy of a copy and so on – millions of times over to the point where the image eventually becomes nothing, or in one experiment, a blurry blob.

To begin addressing how it shapes and influences our lives, Memphis Public Libraries are exploring how the library is going to deal with it. An internal committee is looking into all of it: exploring tools and resources already available; looking at how other libraries, nationwide, are working with it; and, as one of our culture’s cornerstones of trust and truth, preparing to counter its potential destructive effects. The committee has separated into sub-committees to home in on each area of focus: staff training, fair use, resources, and programs frameworks.

This committee is researching the various A.I. tools that are freely available and discussing the ways A.I. has already influenced our daily lives. They are developing frameworks for staff to create programs focused on teaching the public about A.I. literacy. The committee will also be looking at developing training programs for staff to familiarize them with Artificial Intelligence,

both for personal knowledge and to help customers.

The big question asked in this committee is how the rise of A.I. will affect libraries going forward. As an institution of knowledge, as well as a place where computers and the internet are accessed daily, A.I. will have an impact on libraries, whether we utilize it within the library walls or come across patrons who have questions on it.

A resources sub-committee is responsible for finding A.I. tools already available for public use, e.g. ChatGPT, Dall-e, Grammarly, and more. This team has looked into rask.ai, a language translating tool; Speechify, a tool to read text on a webpage for those who may struggle with concentrating on reading; and Izotope10, for audio repair.

As a purveyor of free resources for the public, the library’s focus is on the free versions of these various tools. One roadblock this committee has discovered already is that many of these tools come with fees, large and small. Most of the websites providing A.I. tools offer free versions, but they are very limited as compared to the paid versions, a reminder of the early concerns that A.I. could both exclude and exploit more vulnerable individuals of our population.

A program frameworks committee has drafted a framework for A.I. safety, part of the “A.I.” for Beginners” sessions that will focus

on how to use these tools safely. Currently, the team is trying to make the program user- friendly, especially for those seniors who may not be computer savvy.

A fair-use sub-committee is focused on the ethics of A.I. usage, especially in regard to recreating art and art images. There are a number of image creation-based Artificial Intelligence devices on the internet, some of which are being included as features on graphic design sites like Canva. Users can even change their homepage on Google to a curated image created using an A.I. system. Talks around these types of sites have brought up the fact that these A.I. image generators use art circling the internet within their database without the artist’s permission. The Fair Use committee is looking into these types of issues so staff will be prepared if they come across any ethical issues with A.I. while helping customers. An A.I. ethics program may be created in the future to teach customers about these issues as well.

So far, there are two programs already in the works at MPL focusing on teaching the basics of A.I. to the public. The Cordova Library has an “A.I. for Beginners” series. The Randolph Library has a program focused on teaching teens about A.I. tools. Please check the library calendar for future dates for both these series.

A program frameworks committee has drafted a framework for A.I. safety, part of the “A.I.” for Beginners” sessions that will focus on how to use these tools safely. Currently, the team is trying to make the program user-friendly, especially for those who may not be computer savvy.

In the future, a program based around showing teachers the basics of A.I. will be developed as well. This will focus on the concerns and questions that educators may have with A.I. use in the classroom, whether they plan to use it themselves to lesson plan, or to teach kids the Do’s and Don’ts of using A.I. to assist with homework and other course material. Patrons are encouraged to check our website to see when this program will begin.

A.I. and its usage in libraries is a topic facing libraries nationwide, with a wide-ranging scope and an unknown ceiling. As it has done for centuries of advances in technologies, the library is adapting accordingly. Following that commitment, the A.I. Committee is hard at work to position the library to be able to field any questions that these incoming changes may generate from patrons, customers, and staff alike, and to issue guidelines surrounding its use within the library’s very real walls.

This was adapted and expanded from an article in BookMark, an internal, MPL staff newsletter, with contributions from Mark Fleischer

MEMPHIS ROOM

LINC 2-1-1

CHILDREN’S

DELIVERY & DISTRIBUTION

CIRCULATION / CHECK-OUT

NEWSPAPERS / PERIODICALS

FRIENDS OF THE LIBRARY SECOND EDITIONS BOOKSTORE

CLOUD901

By the MPL UNBOUND Staff

“The

smell of a library is such a happy thing. The smell of books. It’s just joy. There’s just a joy about libraries.”

~Christine Weinreich, Executive Director of the Memphis Library Foundation

It is that quiet place you went after school, a sanctuary. It is that special book you pulled off the shelves, well-worn and well-read, or that brandnew bestseller, the one that made you fall in love with reading. It is hours upon hours of time spent in uninterrupted and wonderfully meandering thought, of leafing through book after book, studying, reading, or learning about the world. A place to dream, a place to feel safe.

“The first day I came to work, here at the Library Foundation,” said executive director Christine Weinreich, “I walked in the staff door and smelled it. The smell of a library is such a happy thing. The smell of books, actual books. It’s just joy. There’s just a joy about libraries.”

The library. The name alone may reverberate in echoes of innocence, discovery, and, yes, joy. It’s one of those words that rolls off the tongue like a lick of ice cream. Whatever your memories of your library are, they are elemental, specific, and almost primal,

activating all the senses. They hold a special place in hearts and minds; a permanence, a part of your DNA.

“I went to the library every day,” states Library Director Keenon McCloy. “And it informed a lot of things. . . . it was a safe place. It was always really comfortable to be there.”

For some, however, the library carries with it echoes of harmless dissonance: from “shh’s” out of nowhere, glares from the librarian staring down our younger selves over the wire rims of disapproving spectacles. Or worse, older generations and individuals of color may recall the library as that place of closed doors, a place of mystery and exclusion, once reserved only for those whose skin color did not resemble theirs.

Today, the public library in American life is as open as it has ever been to people of all colors, ethnicities, and income levels. It remains an active pillar of democratic access. An access that is being threatened by book challenges, privatization of library systems, and cyberattacks on library websites and infrastructure. Librarians have been personally attacked and threatened. Nationally, personal attacks and

threats against librarians have become increasingly commonplace, and leaders at state and local levels have threatened funding cuts. Thankfully, the Memphis Public Libraries have been fortunate to be wellsupported by our current state and local leaders, and Tennessee Secretary of State Tre Hargett has actually increased library funding and not threatened to cut it. Nonetheless, libraries nationwide now face a host of other post-election uncertainties. It is no stretch to suggest that like our democracy, our public libraries are facing tests not seen since the McCarthy Era and perhaps beyond.

Conversely, libraries have seen a renaissance in recent years, adapting to new technologies and evolving into places that not only house and lend books, but also serve the public in a wide variety of ways. Public libraries, at this moment, are still beacons of freedom and free thought, bastions of knowledge and hope, centers for free resources, programs, and learning, and a reflection of the communities they serve. For many, the library is still the cherished third place of their youth – that place outside of work and home where one can clear the mind, escape from the daily grind, meet with a friend, do some actual reading or open up a laptop, or, enviably, to simply be.

“Growing up,” states Keenon, “I lived near PeabodyMcLean with the (former) Main library; the bus dropped me off every day. I lived a block and a half away, so I spent a whole lot of time, because it was the place to be.“

Here in Memphis, we are fortunate to have not just a few safe places “to be” within the metro system, but 18 branches spread across our sprawling city, serving their communities as only they know how, responding to the needs of the neighborhoods they serve.

Among library systems nationwide, our Memphis Public Libraries are shining examples of this current evolution of the library. As the only public library system in the country to win the National Medal for Museum and Library Service twice (in 2007 and 2021), the Memphis Public Libraries continue to incubate and deliver innovations that garner national attention as well as serving one of the most diverse, creative, charitable, yet poverty-stricken metropolitan regions in the country. The Smithsonian magazine gave our library a feature profile in a 2021 issue with the headline “How Memphis Created the Nation’s Most Innovative Library.”

to the Children’s Department– an expansive miniwonderland of books, games, and story times with an adjoining garden– or the sleek lines of Cloud901, the multimedia playground for teens.

The floors above fill in the rest of the tapestry of free services, information, and knowledge: computer desks and terminals, printers and copiers, laptop bars, and free wi-fi. Makers spaces, sewing machines and circuit boards, 3D printers, Legos, and even Nintendo Clubs, and a seed library. Gallery spaces and themed art displays created by library staff.

On every floor you can find that third place - the being spaces - public living rooms and studies, with chairs and tables. A recording space for oral histories in the Central Library’s Memphis Room, which houses archival materials, local historical collections, old phone books, city directories, and microfilm reels of newspapers and directories. Back downstairs, outside the lobby, there are the studios of WYPL. The Memphis Public Libraries is the only public library system in the country with its own television and radio stations.

And that’s just the Central Library. There is a podcast studio at the new Cossitt Library downtown, and a commercial kitchen at the new Raleigh Library.

And of course, at all of the libraries there are rows and rows, shelves and shelves, and miles upon miles of books. Books, those perfectly bound worlds of memory, stories, and knowledge, which are carefully curated and cultivated by knowledgeable, helpful, and passionate librarians.

Taking it all in, with all that the library has to offer, one must wonder, How does it all work?

So how do libraries - still one of the most trusted institutions, here in Memphis and throughout the world - work? How are they governed? How are they funded? How are they established, built, and maintained? And perhaps as critical as ever, as a pillar of democracy, why do they continue to work?

The history of libraries, from the ancient world to today, is an epic tale of perseverance, as noted and explored vigorously by co-authors and historians Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen for their book The Library, A Fragile History. “If there is one lesson from the centuries-long history of the library,” they tell us, “it is that libraries only last as long as people find them useful.”

At the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library, that innovation is on full display. Under a symmetrical canopy of steel, glass, and transparency, it is not the library of our grandparents’ youth, of “shhs” and bespectacled glares. It is open and airy, fostering interaction, acceptance, and invitation on one hand, while providing still cozy nooks and corners on its upper floors for quiet seclusion – those personal spaces for reflection that many of us still seek in our library. In the foyer, there are meeting rooms, a gallery space for local artists, and the welcoming signs of the Friends of the Library Second Editions Bookstore. Through the open doors and into the lobby, there are all the other essentials: book check-out counters, displays about upcoming events, newspaper stands, and shelves of new book releases. Escalators (soon to be restored), elevators, and stairs invite customers to the upper floors. Just past the elevators, one might be enticed by the multi-colored forest of trees that mark the entrance

The earliest libraries date back to 3000 BC in Southwest Asia’s Fertile Crescent, from Mesopotamia to the Nile River in Africa, and continued around 500 BC to early BCE in ancient Egypt, Persia, classical Greece, and Rome. Classical Greece was known for its personal and private libraries, Egypt for the great Library of Alexandria (built sometime between 323 and 246 BC).

Centuries before the invention of the printing press, these early libraries did not house or lend books; they were more akin to today’s archives, and they stored the earliest forms of writing, recorded on clay tablets about an inch thick in various shapes and sizes, holding administrative texts, governmental orders, and collections of resources in disciplines such as geometry, medical science, history, astronomy, and philosophy. Writings on paper, in the form of papyrus scrolls, appeared as early as 2500 BC in ancient Egypt civilizations and continued in use through the heights of the Roman Empire.

“The history of libraries does not offer a story of easy progress through the centuries... Libraries need to adapt to survive, as they have always adapted to survive...”

~The Library, A Fragile History

“Library -- from the Latin liber, meaning ‘book.’ In Greek and the Romance languages, the corresponding term is bibliotheca.”

~Online Dictionary of Library and Information Science (ODLIS)

Ancient Rome is credited for the invention of the first libraries that were open to the “public,” conceived by Julius Caesar and created under Roman soldier and historian Asinius Pollio, built as shrines of dominance in an effort to outshine Alexandria and all preceding libraries. As the book The Library reminds us, “we have to be careful with these phrases (‘open to the public’): authors… were almost by definition members of the elite, and the public they had in mind was composed of people like themselves.”

Such is true for much of library history through the ages. For thousands of years, most libraries did not exist for the benefit of any public; they were impressive structures that housed the personal collections of emperors and noblemen, for intellectual resources or personal interests, and symbols of power or vanity. They were vulnerable to owners’ whims, censorship, or to neglect, wars, or disasters.

In addition, before the invention of Johannes Gutenberg’s movable-type printing press in 1439, the copying of texts was completed by hand by scribes. Scribes were professional copyists, and they also served as latter-day secretaries for kings and noblemen. Their profession was essential to ancient cultures, in the preservation of religious texts, laws, and other forms of literature. And in ancient Rome, they were enslaved.

The early centuries AD through the fall of the Roman Empire (476 AD) also saw a gradual shift that would dramatically reshape the book: the transition of book form, from the scroll to the codex. The codex is the ancestor of the modern book, with pages bound at one edge alongside text formatted in columns, and writing recorded on both sides of sheets made of vellum, papyrus, or parchment.

It was this shift in form that established the book as we know it today, the hand-held, independent, and unplugged organic package that despite movements toward the digital, the cloud, social media reels, videos, or who-knows-what’s-next, is one of last remaining perfections of the world.

As an institution intended for the public good, the

Before we had online circulation systems, libraries used paperbased systems for everyday tasks. This required book card, book pockets (right), charging trays, and the “ca-chunk” sound of a library stamp. From the 1918 Library Supplies, Catalog no. L 1018, the Browne System suggested the use of a book card for every book checked out. The book card was inserted into a book pocket.

~From the Smithsonian’s Libraries and Archive blog

library as it exists today is a relatively new creation. In pre-Revolutionary War America, books were in short supply for anyone not wealthy; those in the lower or middle classes had little access to the written word. To remedy this, Benjamin Franklin co-founded the Library Company of Philadelphia in 1731 with members of the Junto, a discussion group in colonial Pennsylvania. Theirs was a subscription library, and members donated books - many of them focused on religion and education - from their private collections, making them available to fellow members for free, and to non-members for a fee that was given back once the books were returned.

This model was imitated and evolved throughout the original thirteen colonies for a half-century, and by 1780, over fifty townships in New England had established a library.

The idea of a library functioning for the good of the general public has many origins. However, it is the Peterborough Town Library in New Hampshire, founded in 1833, that lays claim as the first taxsupported library in the United States. Many others followed suit. New York State passed legislation in 1835 that authorized state school districts to raise taxes in support of school libraries. And the Boston Public Library, founded in 1848, was the first free, publicly supported, big-city library in the world, and the first to build out space specifically for children.

Through the mid-nineteenth century, a “library movement” had firmly taken hold following a wave of progress - the belief in knowledge as a vital force, and the conviction that access to knowledge should be free. In the late century, New York State librarian Melvil Dewey - yes, that Dewey - founded the first institution for professional librarianship.

But, it was the influence and charity of wealthy industrialist Andrew Carnegie that had the single greatest impact on the public library as we know it today.

As a boy in the 1840s and ‘50s, young Andrew Carnegie believed that book-borrowing should be free. And “Years later,” as the Carnegie Corporation tells us, “Carnegie wrote that the ‘treasures of the world

The book is still the lifeblood of the living library. And from book selections and acquisitions to their delivery and distribution (D&D) to each branch, a book’s physical journey to the bookshelf is much the same as it’s been for centuries: hands-on and labor-intensive.

On the ground floor of the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library, with a couple dozen staff members, it is Monique Williams and Celia Mason’s jobs to see to it that every book makes its journey, from arrival to its intended place on a bookshelf

at one of the 18 branches of the system, ready to be chosen by a reader. That means ensuring that each book is ordered, purchased, delivered, unpacked, sortedrepaired if necessary - cataloged, barcoded, jacketed, stamped, and labeled before the folks at the D&D loading docks pack up their trucks and head out to the branches.

“We’re talking thousands of books,” says Celia. “Our part comes almost last, before the books are ready to go out to the branches and be shelved.”

which books contain were opened to me at the right moment,’” and he was determined to make free library services available to all who needed and wanted them. Beginning in 1886, he used his personal fortune to establish free public libraries throughout America, and by his death he had built over 1,600 libraries in the United States.”

Under his charity, Carnegie paid for the physical buildings, but established a system wherein the community took over the the library’s collections and operating costs. He believed that a city could not progress without having a great library to serve its public: “a creation for and of the people, free and open to all.”

What we benefit from and what we contribute to, all

Celia is the manager of Material Services and Repairs. She and her team perform the meticulous work of physically preparing each book for their journey to each branch and shelf. Their work also includes maintaining existing materials: cleaning, repairing, and re-jacketing.

For the new arrivals, says Celia, “it takes about 30 seconds per book. We timed it out for the entire process. It takes a lot of time, and that’s if you’re cruising through one after the other.”

the wonders that make up the library - must originate somewhere. If the best things in life are free - like the programs, events, books, and librarian expertise of Memphis Public Libraries (and those definitely qualify as the “best things”) - then the fundamental question becomes - after Andrew Carnegie’s millions and philanthropists like him - who pays for the rest? The simplest answer is that public services are paid for by public funds, by tax dollars, by the giant contract we all live under that states, “We want a vibrant, safe, and effective community; here is what we are willing to give in order to make that a reality.” When we all benefit from strong infrastructure, smooth roads, functioning sewer systems, we see those public funds at work, understanding that it takes the mechanism of local government to make public services seem standard, ubiquitous, even banal at times.

As a division of city government, the Memphis Public Libraries have enjoyed strong support from city leadership. Significant library facility enhancements in Raleigh, Frayser, Orange Mound, and downtown at the Cossitt Library were launched during Mayor Jim Strickland’s administration, and this investment in our libraries has continued under Mayor Paul Young, a fervent evangelist for the power of the library. Their leadership has shown a deep understanding of the vital importance of a strong library system in providing essential services to a challenged community, and a trust in library staff to seek remedies to meet those challenges.

But by their nature, public dollars can only allow for so much. Memphis IS a vibrant place to live, but that lifeblood, that vibrancy, is often in reaction to the spreading thin of public funds that should make it all work. Director McCloy understands this. “Part of what makes Memphis Public Libraries unique is the fact that it’s Memphis. Necessity is the mother of invention. [Memphians survive] the poverty, health issues, no access, and no transportation. There’s a lot of ingenuity in being able to stay alive and thrive.”

Inventive ingenuity. Like so many things in the library system, the funding finds a way. The metro budget for Memphis Public Libraries is around 24 or 25

The public library “outranks any other one thing that a community can do to help its people.”

~Andrew Carnegie, “the Patron Saint of Libraries”

BEHIND THE STACKS

“One of the things that I love about [MPL] is that we don’t care about your politics. We don’t care about your religion. . . .We serve everybody.”

~Christine Weinreich

million, according to Deputy Director Chris Marsalek. But “[the budget] fluctuates every year. There are increases in personnel...that are tied to pension... (payroll) tax, things like that, that we have no control over. But again, there’s only so much funding.”

Memphians might be surprised to know how much of that budget goes directly to books and materials. According to Monique Williams, it’s roughly $790,000 per year. Some people think the library must get their books for free, since after all, we aren’t charging anything for them. Right, Ms. Williams? “(Sarcastically) That would be lovely…”

Anyone can walk into a bookstore and buy a new hardback bestseller for around $25, but not your local library. Libraries rely on distributors, contracts, and warehouses to furnish their collections, and they are bound by the parameters of those contracts. And while outright cost for most books is comparable to the public cost of those books, the same cannot be said for other types of materials provided by the library.

The public perception when it comes to ebooks and audiobooks is often the most skewed. “If there’s not a special sale, most of our ebooks cost between … $49.99 to about $69.99. Audiobooks start at $79.99 per copy,” says Monique. “Most of those are metered access, meaning we only get to keep them for a year or two years based on the contracts. When we buy a physical book we get to keep it until it no longer serves the community or it falls apart. Yet the far more expensive ebooks and audiobooks are never ours to keep.”

That budget also includes subscriptions for online databases, serials and periodicals, magazines, newspapers. Less than a million dollars a year for more than just your favorite John Grisham novel and newest Oprah Book Club pick.

“We’re also supplementing our city operating dollars,” according to Monique. Walk into any branch of the Memphis Public Libraries and you will know immediately that it’s more than personnel, books, and magazines. The life-affirming work requires real dollars. If the City of Memphis and the MPL staff are one leg of a three-legged stool that holds up the library system, the other two are the Friends of the Library and the Memphis Library Foundation. Monique continues, “We always talk about how much the Friends and the Foundation do for us, because we couldn’t really do it without them.”

Two private, nonprofit entities support Memphis Public Libraries. The Friends are a collection of volunteers who believe in what libraries can do and work year-round to fund it primarily through book sales and memberships. Christine Weinreich is the Director of the Memphis Library Foundation and explains the MLF as “the fundraising arm of the

April 6, 1888

Tennessee Grants Charter for Cossitt Library.

Frederick Cossitt’s daughters each donated $25,000 in his honor to establish a public library in Memphis.

State grants charter 1889, calling for a free public library, public art gallery, music hall, lecture room, and museum.

library” with a charter that allows them to have only one beneficiary: Memphis Public Libraries. Christine states, “In the mid 90s, a group of philanthropicallyminded Memphians came together to form the Library Foundation because they really felt it was important to have a world class Central library. It wasn’t until after [the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library] was built and they actually had excess money, that they decided to initiate the endowment and move forward from there as an ongoing resource to support the library.” Enhancements like Cloud901, Teen Innovation Centers at neighborhood branches, special collections, and every day programs are part of the Memphis Library Foundation’s goal. Weinreich continues, “the primary role day to day with MPL is to identify funding resources for the programs that library staff want to be able to implement and library leadership think are priorities.”

Even an institution so thoroughly essential to its community and loved by its patrons has its share of challenges. Some communities in the states of Texas, Montana, Missouri, Utah, Florida, and Arkansas, are even cutting ties with the American Library Association, the national organization that is dedicated to ensuring access to information through libraries and opposing censorship.Two challenges in particular, the rising numbers of book challenges and the trend towards privatizing libraries, are sweeping across the United States.

Privatization is shifting the control of a library from the public sphere to a private company. Local politicians use tax dollars to pay a business entity to run the library, which can mean that factors like political agendas and the “bottom line” influence day to day operating decisions.

Privatization can result in a couple of outcomes. The library becomes more like a business in terms of function and policy, and some of the unique selling points that most public libraries have are often muted or done away with completely. This can include access to an innumerable and diverse collection, a wide array of community programs and resources, transparency on spending and tax dollars, public contribution to collections and policies, and the feel of being ‘The Third Place.’

One might argue in terms of pros and cons when making the decision to privatize a local library. For example, a pro for the financial stakeholders of a privatized library is that it can cost less to maintain it. Financial stakeholders have control over the budget for materials and services that their library provides and can choose when to curb costs. They could slim down the budget for new books, eliminate funding for library programs, and even offer smaller salaries to their workers. The cons of privatizing often fall on

From DIG Memphis, and G.Wayne Dowdy’s Hidden History of Memphis

April 12, 1893

Cossitt Library opens at 33 S. Front Street

Mell Nunnally serves as the first director of Cossitt Library. Serving until 1898

September 1, 1898

Charles Dutton Johnston named library director; Johnston largely responsible for the Tennessee General Assembly passing a law setting aside a percentage of Memphis property tax revenue for library services.

1903. Cossitt establishes first of its branches for African Americans, opening a library within LeMoyne Institute.

the employees and patrons. Librarians working in a privatized library are typically paid less than their public counterparts, and the library, working on a slimmer budget, can put out less for the public in terms of programs and resources.

Of course, another selling point of privatization for some is the ability to limit and control the collection on their shelves. Book-banning has been around as long as there have been books, but the more recent trends in American politics have added fuel to fires we haven’t seen since the McCarthy era. And banning becomes simpler to do in a privatized library. Along with politicians, whatever private company manages the library decides what goes into it. Any books that don’t fit the company’s ideals or standards can be quietly pulled from shelves under the guise of weeding books due to relevance, correctness, or lack of public desire for them. With the rising politicization of diversity and inclusion, this can mean that books with certain religious content, political beliefs or information, LGBTQIA+ content, history of marginalized communities, critical race theory, or anything deemed ‘inappropriate’ or ‘offensive’ by the operator can be censored and, therefore, unavailable to that library’s community. Across the country, this very thing is happening in school, privatized, and even public libraries thanks to new state laws.

In Memphis and Shelby County, it is no different. Christine Weinreich says, “I think sometimes [in Memphis], we feel like we’re insulated from these kinds of things that happen all over the country… that’s foolish for us to draw any comfort from that.”

Whatever this historic wave of book challenges and privatization brings, Memphis Public Libraries and its supporters have a very clear stance. For Keenon McCloy, the library is not about profit or controlling which books are available for its patrons. “For me, it’s the people,” she says. “I don’t believe in censorship, you know, as a generalization…we don’t want to be censored…we’ve been clear since, well, since I got here. Banning books is not something we’re going to do…People deserve to be able to take in whatever learning or anything they’re interested in. I might not share your taste in it, or whatever, but that’s not for me to judge. It’s all personal.” Chris Marszalek agrees, saying, “I think the public library knows the community better than anyone…I don’t know enough about the operation of a private company running a library, but I just don’t imagine a business model being about meeting all the needs of the community in the way that [Memphis Public Libraries does].”

No matter the political climate, MPL upholds the same standards. Christine of Memphis Library Foundation puts it this way: “One of the things that I love about [MPL] is that we don’t care about your politics. We don’t care about your religion. We don’t care about your ethnicity or whether you are

1906. Children’s Department Opens at Cossitt; converted the Women’s Reading Room into a space specifically for younger readers.

more generally conservative or liberal in any way, socially–any of it. We serve everybody. And I think that message, if you have a one-on-one conversation with people, can really resonate with anyone.”

After all, the public library is just that: public. A reflection of its community. A reflection of you. No matter the patrons, if they walk into their public library and can’t find anything that resonates, affirms, or provides for them, then what is the point? Why do their tax dollars go to this? How does it serve them? Memphis Public Libraries strive to be places where an individual can go and see themselves mirrored not only in the collection, but also in the programming, the librarians, and anything that can be found under their local ‘START HERE’ sign.

Everyone has stories from their first experience at the library. They can close their eyes, go back in time and conjure up the scent of well-worn books and a vision of endless shelves spanning out in front of them. They often remember how old they were when they first passed through library doors, what they did, and how often they went.

Director Keenon McCloy’s memories of the Main Library and her daily visits are still strong. She remembers that “The librarians were really intentional about trying to teach us something or tell us something that we might not have known.” Her first discoveries included the albums in the listening room. “The vinyl was so great,” she says, “Like, ‘you’re going to let me touch this turntable?’ And the librarians were like ‘yes, if you’re responsible with it.’ It was one of those things I had never considered to be in a library.”

For Christine Weinreich, it was growing up in Flint, Michigan. “We would go to the downtown library, which was a big one…the oddest formative memory of my childhood in a library was microfiche…looking at old newspapers and things on microfiche was so fun.”

Past experiences stick with people. They’re steeped in people’s brains–the good, the bad, and the ugly. They can influence what people do in the future, how they behave, and what they do and don’t like. For most, the library is a good experience. It is discovery, safety, and access to a greater world. But that doesn’t mean that it can’t change–that it shouldn’t change. For Keenon, “[The library] is a living document in and of itself. The library continues to evolve.” And it does. Despite similar notes of nostalgia and experiences that all library lovers seem to share, it does change.

The evolution of a library starts and ends with the patron.

The public library of many childhoods, as everyone can guess, gave the public access to shelves of books, librarians with their vast knowledge, and any

“[The library] is a living document in and of itself. The library continues to evolve.”

~Keenon McCloy

1939. Opening of Vance Avenue branch for African Americans

1951. Highland Branch opens. 1955. New Main Branch at Peabody & McLean opens

October 13, 1960. Desegregation of all public libraries

1973. City and county governments created the Memphis/Shelby County Public Library system.

1975. Library Information Center (LINC) was established

2001. Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library opened

“MPL’s branches are in the city in some pretty high poverty areas and where there aren’t many other resources. [Part of what we provide] is something as simple as a clean bathroom or a water fountain, simple things like that…There’s a lot that can be said for those things.”

~Chris Marsalek

technology required to peruse them. Then it evolved, bringing in newer technology, library programs and activities, resources, and more. It’s evolved in ways that people haven’t even noticed.

For one, MPL has gotten good at providing the simple things. Explained by Chris Marsalek, “[MPL’s] branches are in the city in some pretty high poverty areas and where there aren’t many other resources. [Part of what we provide] is something as simple as a clean bathroom or a water fountain, simple things like that…How many spaces are there…where [you can] come sit down in an air conditioned space? There’s a lot that can be said for those things that people don’t think of when they think of a public library...A lot of people think of libraries as a place where you can come get a book. But for other people, it’s all these other things.”

Keenon adds that, “[Growing up, the librarians] were very into shushing me.” She loved the library, but that was one of the experiences she didn’t like. When she became Director of Memphis Public Libraries, she says, “I was committed to not having a library like that...I didn’t want anyone shushing anybody, because you’re kind of taking away their voice...I’m a loud person anyway...“ Memphis Public Libraries, as it is now, is not one for shushing. Through Keenon’s past experiences and surely those of the librarians in MPL’s employ, the library became a place where you could not only read, but you could also speak.

Similarly, leadership has opened the libraries to a more creative approach in recent years. Chris Marszalek shares, “The opening of CLOUD901 (the innovative teen space in the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library) was a major change for how we operate. [When we] started trying to hire people, we realized quickly that we needed a different type of skill. One job description doesn’t really describe what’s going to happen in the sound studio or in a maker space area...The opening of CLOUD901 made us think, as an organization, differently about all our positions…Obviously, [a Master’s in Library Science] is a very important degree…but we focused more on ‘what skill are you going to bring?’ ‘What background do you have that will help us move forward?’” For all of Memphis Public Libraries’ employees, Keenon sums up, “Program to your passions.” The result? Any employee with an idea, a passion, can create a program. Employees from all different walks of life with different experiences, abilities, and passions are making programs for their communities, expanding what the library offers and who it offers it to.

The Memphis Public Libraries is unique in that

aspect, and also with its two National Medals for Museum and Library Service. “I think Memphians have something special,” Keenon says. “Necessity is the mother of invention. [Memphians survive] the poverty, health issues, no access, and no transportation. There’s a lot of ingenuity in being able to stay alive and thrive.”

That ingenuity is reflected directly in the library’s day to day programming, in customers’ book requests, and in their expressions of their needs and passions.

All of this molds the library, forming and evolving it into something useful to every customer. And as members of their customers’ communities, librarians play a critical role, bringing their skills and passions into their work. Librarians get to know each customer and what they need when they walk through the library’s doors. If one comes in wanting to read a certain book that’s not in the collection, their request makes its way to Collection Development and into consideration for the library’s shelves.

The pandemic is a perfect example of the library’s adapting to the customers’ needs. Cloistered away in their homes, people couldn’t come to their local branch to check out books. But a bookworm’s appetite doesn’t cease, especially in the boredom of isolation. Monique in Collection Development recalled that, “[MPL’s] ebook collection was not heavily poured into when I first moved here…it wasn’t heavily used…the pandemic actually boosted the usage of [ebooks]...more and more people have started using [ebooks]. So [Collection Development has] poured more of the budgets into the Overdrive and ebook collection, because [people started using them]...now that more people are getting into it, their collection has grown.”

The Memphis Public Libraries’ responses to the public’s changing needs during the pandemic marked another of the adaptations discussed in Pettegree and der Weduwen’s The Library, A Fragile History: “libraries only last as long as people find them useful.“ In an evolution that started when Roman leaders opened their library doors to their public, that continued with Benjamin Franklin’s lending libraries and Andrew Carnegie’s free public libraries, libraries must adapt to survive, and to serve. And if a library is doing it right, the more a customer, patron, reader, visitor, and refuge-seeker uses the library, the more it should reflect them and connect them, to their community, to themselves, to their world. The more we use it, the more we should see ourselves.

We’ve asked How does the library work? It works, because at its best, it is us.

Merlynn Clemons, a fixture in the Cossitt Library since 2008, is a perfect representation of the variety of career backgrounds and skill sets the librarians of Memphis Public Libraries come from.

In the summer of 2024, Emma Pennington of the Memphis Library Foundation sat down with Merlynn in the conference room of the historic Cossitt Library for a candid conversation about her career as a librarian, and what drives her efforts to help people in need.

Emma: What was your background prior to working at MPL?

Merlynn: “I was employed with Housing and Community Development, so I felt [that Cossitt] could be a good fit for me because of my skills and background and working with the organization that provided service to the homeless…I was hired as the Coordinator of neighborhoods…I started off assigned to Orange Mound, Lauderdale, South Memphis, Binghampton, and West Junction.”

Emma: What did that lead into?

Merlynn: “Because of my working and being in the neighborhoods, I was given an opportunity to work as a consultant to develop a social service plan…we established the Department of Supportive Services, and I was given the opportunity to become manager.”

She has also worked with the Memphis Housing Authority as Social Services Supervisor, Regional One Medical Center as Director of Community Outreach, and in various organizations establishing programs to help youth, families, and the [unhoused]. She worked in one such organization, Memphis Urban League, establishing a program for high school dropouts:

Merlynn: “We worked with various construction trades to identify job opportunities for not only boys, but for young ladies to obtain a trade and at the same time acquire their GED diploma and become self-sufficient.”

Emma: Why did you choose to work at the Cossitt branch?

Merlynn: “I accepted the [library] position, thinking that I would only be here for a few years…I was asked which branch that I’d want to work in, and I chose [Cossitt] immediately because of my background in housing and working downtown.”

Emma: So, how do you feel your career background informs your work here at the library?

Merlynn: “…I have had a working relationship, I guess, between housing and job training, youth programs, and assisting adults. [That] ties into the different things that goes on within the library itself, which is exposure to different career opportunities, health care, and resources…[My social work background] really goes hand in hand with [my library career]. [It] helped me to be able to relate to the library customers…”

Merlynn continued to say how her career background draws her to the unhoused population that takes shelter in the library during open hours.

Merlynn: “It’s an open, public facility. And if you think about it’s the only place downtown for people to actually go up to during the day...[People who are unhoused] stick to certain library branches…I believe [they know] how they are treated once they approach the door whether they are welcome.“

There are no bandwidth limitations on possibilities at the Memphis Public Libraries. Restraints are not meant to be placed on the mind. So, imagine how powerful we are when many minds come together for the greater good of our community.

The Memphis Public Libraries system is not just the minds of the close to 300 people who are employed by the City of Memphis working in some capacity at our 18 locations. It’s the collective minds of more than 621,000 individuals who reside in the city and yes— that includes you.

When thinking about what makes libraries work, many consider budgets, mayors, city council members, check-out clerks, and program managers. But the most important element of that equation is you. We never forget that. We do what we do because of you. We exist to help make the lives of every member of this community better, and the best way to meet that objective is by listening to you. That is why we are encouraging you to share what you want and need from your libraries.

Let me tell you about some of the things we’re doing, a few of which you may have already read about in this issue. We are going into communities to meet people where they are and providing library services through outreach. We are assisting with literacy support for preschool-aged children. We are creating STEM programs and educational opportunities for our elementary-aged children. We are offering mental health awareness programs to our teenagers.