The Boothby Review

Editor-in-Chief

G. Howard Hunter

Copy Editor

Erin Walker

Layout Design

Shay Steckler

Jack-Of-All-Trades

Sean Patterson

Production Assistant

Jennifer LaCorte Marsiglia

ANon-ConversationwithMaryBethEllis,Shay Steckler

JazzFunerals, L.A. Reno (see also pp. 40, 62, 88, 108, 116)

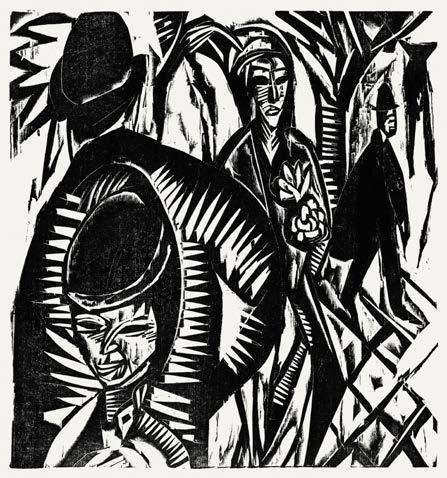

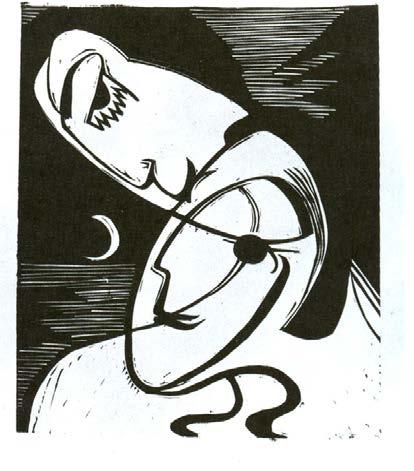

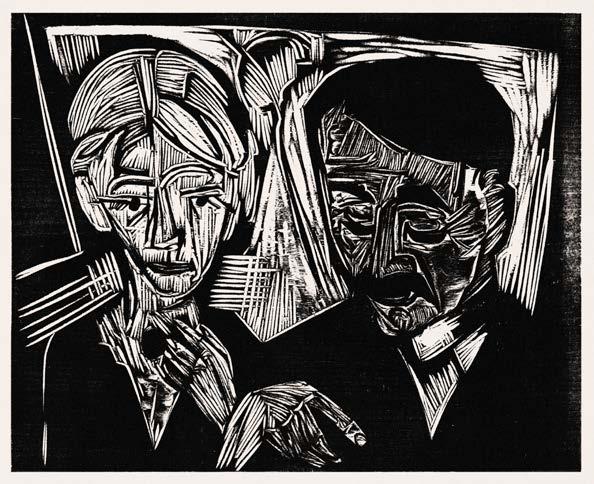

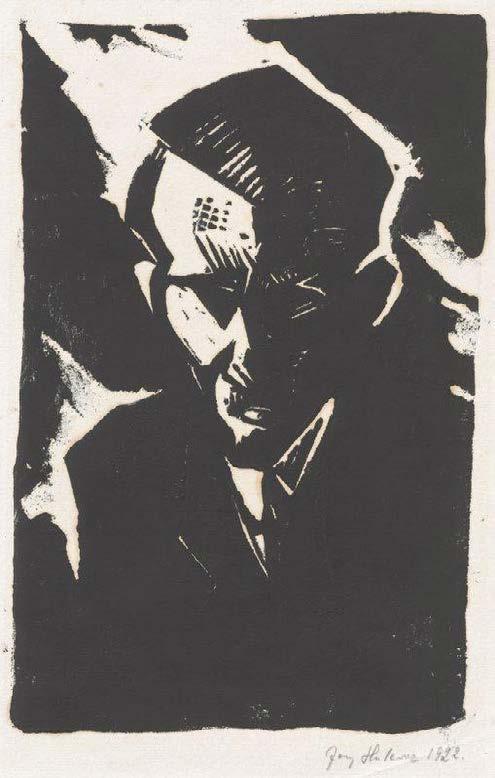

TheDouble, Sam Ferguson

AFilmLover'sDump,Mike Miley

TheHardProblem,Howard Hunter

RockabyeBaby!,Pam Skehan

LastDanceWithButtersandOmar,Justin Gricus

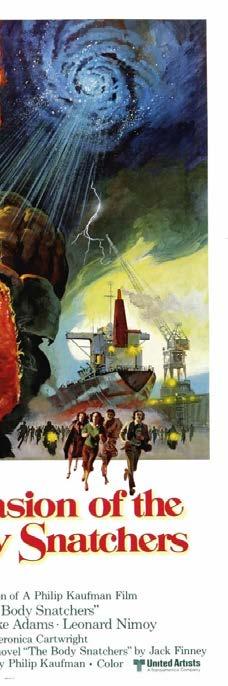

'They'reAlreadyHere':ADeeplyUnnecessaryDiscussionofInvasionofthe BodySnatchers(withspoilers),Robin Heindselman

Wild,Erin Walker

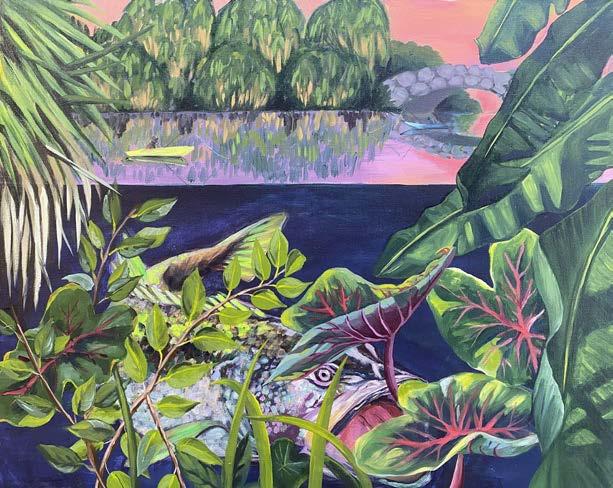

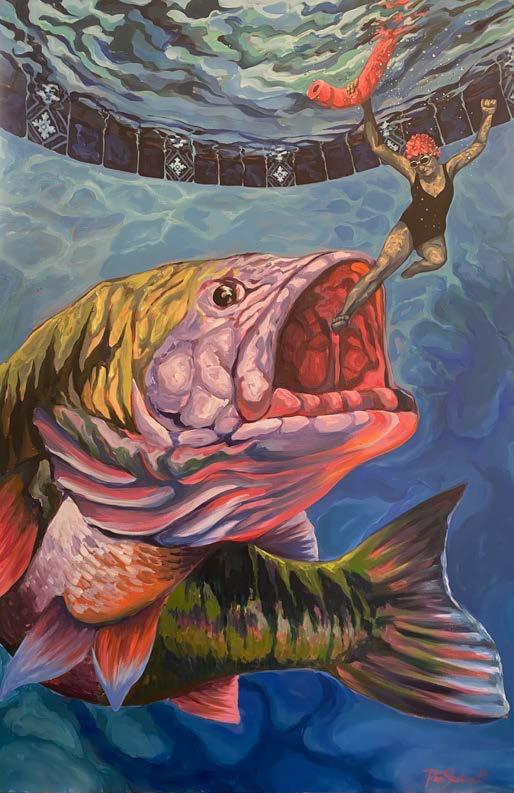

ThroughtheBellyoftheFish:TheFinalPlunge,Pam Skehan

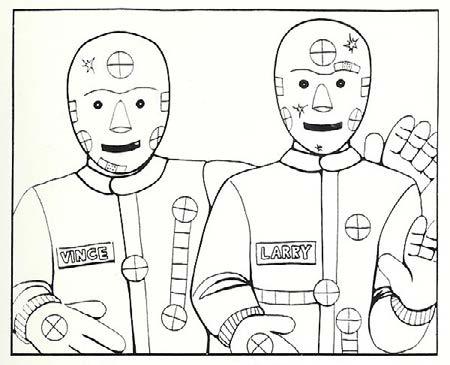

DualityforDummies:ASubjectiveListofCrudeEvaluationsbyan UndereducatedPhilosopher,Sean Patterson

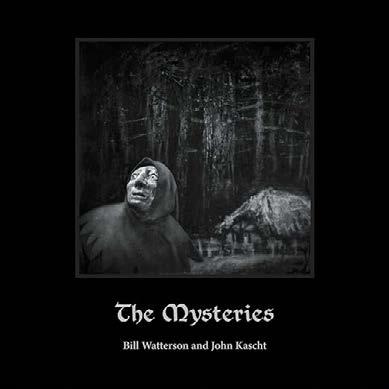

BookReview:TheMysteries,Howard Hunter

AuthorReview:AndersonCooper,Angela Beerman

BookReview:TheBomberMafia,Jason Hubert

FilmReview:Maestro,Howard Hunter

TheProustQuestionnaire:KatieAntis

Seventeenth century philosopher René Descartes averred that we are the stuff of two substances— body and soul. The doctrine formally called dualism has its origins with Plato, who made distinctions between the unchanging realm of ideas and our physical world which is subject to the vicissitudes of life (for example my decaying human body as opposed to my soul). For obvious reasons early Christianity embraced Platonic thought, and we have a Western intellectual structure based on opposites, e.g., good/evil, male/female, or pleasure/pain.

In Volume 3 of TheBoothbyReview, we explore the problem of duality. In one work of fiction, there is a young man dogged by his doppelganger, and in another short story, a young woman sees herself in opposition to those other people who simply don’t measure up. Both works have an interesting denouement, to put it mildly. In one essay, we delve into the power of art in finding transcendence from grief. In other pieces, we celebrate a movie theatre unlike any other, as well as that nagging problem of humans vs. zombies. We also include book and film reviews that dwell on the vagaries of the human condition as well as photographs that mourn death and celebrate life through the jazz funeral. But of course, we could not let the notion of duality go unchallenged. Our first article is an interview with Madame Ellis from the Buddhist perspective. For many, the concept of duality is thoroughly contrived, a canard of Western thinking. We hope you enjoy.

G. Howard Hunter, Editor-in-Chief

G. Howard Hunter, Editor-in-Chief

When I told Mary Beth the theme of this year’s TheBoothyReview would be duality, she seemed puzzled. Why? There’s no such thing as duality. Mary Beth Ellis has been studying Eastern thought for over fifty years. A practicing Buddhist herself, she has had the opportunity to study in Dharamsala, India, at the Naropa’s Buddhist University in Boulder, CO, to attend workshops and presentations by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and to teach her own classes on Eastern thought and spirituality to both high school students and adults.

Shay: Ok, so talk to me about duality, or non-duality.

MaryBeth: Non-duality. It’s a very, very deep, complicated concept, and it’s not one that can be understood intellectually, although for purposes of this article, we need to make it an intellectual answer, so I’ll do my best.

Shay: So it’s not just that there is no duality?

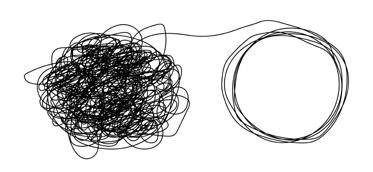

MaryBeth: Well, here’s the thing. You can’t say that there is duality or that there is non-duality. You can only say maybe that there is NOT duality. Now, if that isn't confusing enough, that gives you an idea of the complexity of the situation. However, we are going to make it a little surface-y, facile, and easy to understand. You can’t understand it intellectually; you’ve got to understand it experientially, but the following might help clarify it a bit: Non-duality means that there is no subject and object. We are all one. Quantum physics has verified this in the last 50 years, this idea that’s been around for thousands of years in the East. What it means simply is that there is no separate object or person that exists in and of itself. Every object, even a physical object, is just energy, energy that exists in everything else. We all know now that a human being doesn’t have any of the same cells he or she had seven years ago, so it’s easy to imagine that all the energy is constantly coming and going in and out of people. It’s one of those things like: “Is the wave part of the ocean or a separate entity?” That would be an example of duality or non-duality. Some people would say quite accurately that the wave is the ocean. That’s non-duality. But then other people would say, “No, there’s a separate wave.” That’s duality. But, those are intellectual concepts like, “How many angels can dance on the top of a pin?” The point is that everything is a mental concept if you’re gonna talk about this, which you really can’t.

Shay,laughing: So we’re not having this conversation.

MaryBeth: We are not having this conversation. (Shegiggles.) It makes sense for everything. For example, a cloud, you can’t say a cloud is a separate thing, a cloud is made up of air molecules and water molecules, etc., and everything is like that— everything is part of everything else. So that’s kind of an easy way to conceive of the idea.

Shay: In Eastern thought, there’s no good and evil; it just is?

MaryBeth: Yes. Everything just is. Good and evil is a concept in the human mind. Some people thought Hurricane Katrina was evil. Now, many people think it changed New Orleans for the better. Most things we get negative about and consider bad are just triggering some unresolved seed in us. Spiritual teachers often say that what we consider bad or evil events in our lives lead us to God. Thomas Keating terms these things “the 1,000 paths to God.”

Shay: What about Plato’s cave allegory?

MaryBeth: Well, Plato is someone who understood that idea because he understood that our concept of what reality is is not at all what reality really is. We see only the shadows on the cave wall; we have no idea what’s out there creating these projections. And that’s the way everything is in our mind. I mean that’s a perfect example of the way that our minds create their own reality. We are seeing nothing but shadows in the cave. All day long. That’s it. And it takes probably years and decades of meditation, honest self-reflection, and dealing with this idea to truly start experiencing what it is—not just intellectualizing about it. You couldn’t explain to somebody sitting there in the cave who had looked at nothing but those shadows for a lifetime that they aren’t reality. It’s not until they break their chains, turn around, and go out and experience reality that they can see the Truth. “Oh, that’s what it is. It’s the shadow of this.” But what we are doing right now is talking about two people sitting in there looking at the shadows who have never seen anything but the shadows, who are chained, talking about the possibility that maybe it’s not reality. But they have no concept of what it might be. That’s what I was referring to. How do you tell someone what chocolate tastes like if they’ve never eaten any? Carl Jung and the latest in neurolinguistics talk a lot about unitive consciousness or non-duality, so it’s now becoming very popular, but it’s a concept that has been around for many thousands of years in the East, and which has even been in Christian teachings since the 4th century of the Common Era. The oneness of all life is not new at all.

It’s a given in Hindu and Buddhist teachings, like the Upanishads and Vedanta, so it isn’t often discussed. It’s only been recently in the West that it’s become trendy. Buddha didn’t talk about it at all.

Shay: Because non-duality doesn’t exist?

MaryBeth: It’s more that Buddha was very pragmatic. He was not into intellectual concepts, but since Buddhism morphed out of Hinduism, the concept was there; however, in the East it is such a given that they wouldn’t need to discuss it.

Shay: Buddha wouldn’t have mentioned duality because there was no duality to even mention.

How do you tell someone what chocolate tastes like if they’ve never eaten any?

MaryBeth: Right. He wouldn’t have thought of it. I don’t know, nobody does, because nobody knows exactly everything Buddha talked about, but from all the writings and the research, most Buddhist scholars say, “No. Non-duality was a concept that started later because in the West, we tend to think in dualistic terms.”

Shay: So the idea of non-duality came out of the West?

MaryBeth: No, it came from the East, but the West has made a big deal about it because we think in dualistic terms. Like so many intellectual concepts, Buddha never taught it. He left Hinduism because he didn’t like all that intellectualism, dogma, and ritual. He was pragmatic: Be good. Be compassionate. Help everyone. Life is what we make it. People just made it very complicated, and duality was one of those concepts. But, we can understand that in terms of quantum physics—life is all energy, and it’s all inter-related. Thus, all life is one.

Shay: Right. Like light and dark. Dark is simply the absence of light. It’s not a separate thing.

MaryBeth: Yes. It’s like the yin and the yang in Taoism. You’ve got the black and the white, but each one has within it the opposite. And it can’t be what it is without that. And that’s only a small symbol of it right there, but the point is that we have in our minds the concept that there are fixed material objects out there and they each mean a certain thing. We in the West are totally victims of this dualist thinking, like the people watching the shadows in Plato’s Cave Allegory. That’s why we have this concept of nonduality; we need it to break free from our concept of duality, which in the East is a given.

Shay: That’s why you gotta meditate.

MaryBeth: I didn’t say it, but that is said to be the truth. Years of meditation allows us to make the necessary shift in the hardwiring of our programmed dualistic perceptions. Then we actually can go out into the world and see the reality of what projected the shadows in the cave, which we thought was reality. Otherwise, we are stuck in the cave looking at the shadows and perhaps intellectually talking about the fact that it’s not real, but we have never really experienced liberation.

Shay: Because we haven’t experienced being one with the all.

MaryBeth: Yes, it’s only a concept in your mind, and intellectual concepts don’t work with basic reality. Bottom line, non-dualism is a very trendy, recent concept in the West. No one talked about it in ancient, authentic Buddhist texts. The concept was a given. Christianity’s dualistic concepts brought about the word’s use. To a Hindu or Buddhist, it would be like saying, “I have this revolutionary idea: the sky is blue.” Duh.

The whole thing is akin to the last scene in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy realizes that the shoes which can carry her home have been right there on her feet the whole time–or maybe like Moliere’s Bourgeois Gentilhomme, who is so proud of himself because he’s been writing in prose his whole life and just didn’t know it. We can’t really talk about non-duality, because duality doesn’t and never has existed. Or as Thomas Merton said, “You have to experience duality a long time before you realize it’s not there.”

Shay: I love that.

MaryBeth: Isn’t that fabulous?

Shay: Well, it was really great to not have this conversation with you.

MaryBeth,laughing: Even though it’s a conversation about something that you can’t discuss anyway, it’s been very interesting to do so.

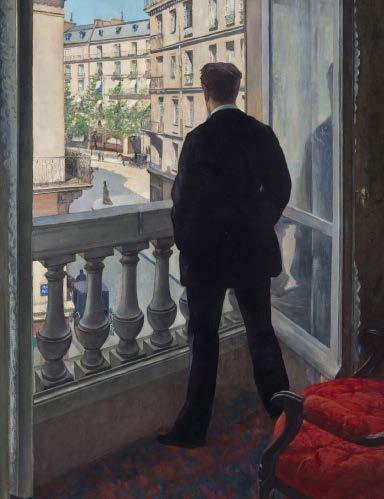

It was there, on the Wilhelm Tower’s only functioning elevator, that Schmidt was first apprised of the existence of his double. Mr. Beckroth—the president of Kaiser Bank and thus, though far removed, Schmidt’s ultimate superior—was waiting at the threshold of the lift, just off the lobby, his suitcase in his left hand and his bowler in his right. He had not, it seemed, seen Schmidt, who had halted just behind him and a few steps to his left, nervous lest this man, with whom he’d exchanged only meaningless pleasantries, should recognize Schmidt and condescend to conversation. It was rare, Schmidt thought, for Beckroth to be here—now, at seven thirty, thronged by common clerks and even janitors and chambermaids. His hair was combed back in luxuriant waves, and his dark pinstripe suit and Italian shoes—shined to a bright and exorbitant black—emphasized the tanned, athletic vigor of his skin. He was, Schmidt guessed, about sixty years old, though he remained, despite his age, a man of intimidating briskness and vitality, like a general who still lusted after combat.

The doors drew apart, and Mr. Beckroth stepped inside. Schmidt scurried after, his face turned away, hidden by his shoulder and the bustle of the others—three men and two women—who were filling the compartment. But Schmidt, for all his stooping, was a very tall man, a tousle-headed scarecrow in a just-too-tight suit, and Mr. Beckroth, standing with his back against the rear wall of the lift, his gaze frankly trained on the oncoming scrum, soon spotted and addressed him.

“Eckermann, my boy.” He reached across the lift and squeezed Schmidt’s arm. “I heard all about the new Teitelbaum account. A fine piece of work. Yes, you’re well on your way.”

It should have gone without saying that Schmidt wasn’t Eckermann. He was Schmidt. But how, without considerable embarrassment, could this fact be made known?

“Teitelbaum, sir?” asked Schmidt, with no intention of sustaining his superior’s confusion.

“Oh, such modesty is charming to your peers, I have no doubt. But you shouldn’t try it out on an old rascal like myself. I’ve been watching you, Eckermann. You’re a killer. Just like me. And that’s exactly what we need. A whole floor full of killers. A whole army of Eckermanns.”

He was smiling up at Schmidt, still pinning his arm in his firm, virile grip.

“Thank you, sir,” said Schmidt. “But I—”

“Oh, thank you’s enough,” interrupted Mr. Beckroth. “There’s no need to play down your successes with me. Your thanks is enough—and, of course, your continued success.”

“Yes, sir,” said Schmidt, “but I should tell you—”

“Know when to say when, Mr. Eckermann. Please. Now this is my floor. You’ll see more of me soon, I’m quite sure of it. Excuse me.”

He gave Schmidt’s arm a valedictory squeeze before stepping through the pack of lesser laborers and exiting, at last, into the lobby of his office—that marblefloored, wainscoted palace of an office which occupied the whole of the tower’s tenth floor.

Schmidt’s confusion was compounded by the kindness of this praise, and any pleasure thus intended was converted into pain—the lingering sting of embarrassment, the shattering blow of his own anonymity. The president didn’t know Schmidt from this Eckermann—did not, evidently, know Schmidt in the least. The praise, what was more, had simply emphasized his weakness, the inertia and stagnation that had qualified his clerkship. He felt himself reproved within the shadow of a genius.

The seventeenth floor, where Schmidt stepped off now, was wholly given over to the junior clerks’ work room, a vast but stuffy space in which the cluttered dispensation of the workers and their desks had formed a densely crowded grid, a hive of buzzing industry with minimal partitions and a sense, overall, of assiduous drudgery. The room ran the length of a regulation football pitch, and there were countless men and women here whose faces Schmidt knew well and yet whose names, in their abundance, he had never thought to learn. Here, in the work room, a man rarely spoke beyond the barest verbal needs for the conducting of his business. It was a hub of oblivious, name-bereft faces, a world in which the passing of the hours was marked by paperwork, by the signing of contracts, the stamping of missives, the approval or denial of debentures and investments.

He proceeded to his station at the center of the room and was halfway down his aisle when he noticed, at its end, a man he didn’t recognize. The man was tall, as tall as Schmidt, and he had the same halo of tousled brown hair, which rose from his scalp in great bristles and curls. But where Schmidt was rail-thin, and where he shuffled with a skittishness made quick by his anxiety, this stranger was sure-footed, muscular, bold. Eckermann, thought Schmidt. His double. This was Eckermann.

He sat down at his desk and tried to focus on his work. But even here, from his chair, he saw Eckermann, who had sat on the edge of Ms. Bierbrauer’s desk. He was leaning flirtatiously towards her, his curls hanging low on his broad, handsome brow, while Miss Bierbrauer—the work room’s chief secretary, a severely pretty woman who was never known to smile—actually threw back her head with a laugh, her pale and lovely throat profoundly naked in her mirth. It was, Schmidt thought, an unbelievable sight. Unbelievable, yes, but also distracting.

He turned to Leo Reuss, his only friend at Kaiser Bank. Reuss’s nose was to his desk, farsightedly pressed toward a sheaf of fresh contracts.

“Reuss,” said Schmidt. “Hey, Reuss. Who’s that man?”

“What man?” asked Reuss.

“That man. Over there.”

Reuss lifted his head. His eyes followed Schmidt’s to the end of the aisle.

“That’s Eckermann,” said Reuss. “A man on the rise.”

He’d spoken with an edge of nasty irony. He was short and frail himself, and all signs of male strength he perceived as a slight to his own quite diminutive person.

“How do you mean?”

“The Teitelbaum account. You heard about it, didn’t you? A tricky bit of business, though he sewed it up perfectly. Say what you will about the way he walks around the place, like Jehovah’s own gift to the world’s junior secretaries, but the man gets results. He’s efficient. He’s ruthless. They say he’s due for a promotion.”

“A promotion,” Schmidt quavered with impotent envy. “How long has he been here? I never saw him till today.”

“As long as you’ve been here. For five years at least.”

“Have I been here that long?”

Reuss shrugged, unenticed by the mysteries of time, and readdressed himself with interest to the contracts on his desk.

Schmidt, for his part, struggled to ignore the rampant laughter of Miss Bierbrauer—the only sign, without his looking, that this Eckermann was there. But soon he had immersed himself in drafting memoranda, and when, some time later, he looked up from his desk, he found that his double was gone, that he had disappeared at last within the vast hive of the work room.

The rest of the day involved no further incidents—until, that is, Schmidt’s departure, which was colored by the knowledge of his double, of his bearing a resemblance, however pallid or unfavorable, to the vigorous and enterprising Eckermann. It was normal for Schmidt to leave promptly at five, rushing toward the exit, meeting no one, saying nothing. Today, however, was different. Today he crossed the work room with a light, audacious jauntiness and turned his eyes unflinchingly on everyone he passed. He was looking for the gestures of mistaken recognition, for a smile or a nod or a greeting for Eckermann, and these he was to find in each new person that he passed, who seemed to regard his great towering awkwardness not as a threat or as some lanky imposition but as the natural gait and stature of a colleague on the rise. Several women smiled. Several men said good evening. And when he made it to the lift and saw the doors were closing quickly, he was gratified to find a colleague’s hand shoot forth to hold them. His gratitude, quite naturally, was met with further warmth—a gentle, smiling nod, the happy music of You’re welcome.

The small world of the work room and the tower seemed to blossom, to open up before him with a bold but yielding easiness. It struck him as unseemly, his usurping of this ease. He felt, as he descended, like a con-man or a thief. usurping of this ease. The president himself had called him Eckermann. Schmidt had not succeeded in correcting him—had crumbled. Was this not, on its face, an unsustainable imposture?

As always he stopped at the Black Marten Inn, one block from the apartment where his wife and son awaited him. He liked, on a Thursday, to nurse a frothy pint and read his favorite evening paper, alone with his thoughts and the news of the day before the caterwauling nagging of his family obligations.

He’d sat at the bar and had waved for his drink when he noticed, in the corner, the unexpected silhouette of Eckermann. Had he followed Schmidt here, from the office? Was this some sick joke, some theatrical prank, performed by unseen agents bent on Schmidt’s humiliation? But such a joke, when he considered it, did not at all seem likely. Eckermann had clearly finished several rounds already, and his gaze, far from crafty, shone with all the florid joy of heedless dissipation. He was joined, what was more, by a woman—a woman ennobled by a beauty so uncommon that it emphasized the commonness of everyone around her. Everyone, that is, except

Eckermann. He shone further still in the flame of her presence. They were beautiful together—beautiful and drunk and frankly amorous. Eckermann had draped a winsome arm around her waist, and she, like Miss Bierbrauer, tossed back her head at this charming man’s quips, which Schmidt couldn’t hear but which came, as she laughed, with a frequency and skill that might stir envy in a clown. Was this, Schmidt thought, some kind of fancywoman? But no, she surely wasn’t. Such women didn’t laugh with such conviction—did not seem so enamored of the men who were their “patrons.” And this wasn’t, besides, the place for fancy women. The neighborhood was quiet. It was decent. It was home.

Schmidt’s glass, he now found, had been emptied. He waved once again at the barman.

“Another, Alphonse. Just one more.”

“Anything else, sir?”

“Yes, in fact.” Schmidt was whispering. “Who is that man?”

“Who, him?” Alphonse crowed. “That’s Eckermann, sir. You know him. He’s a regular.”

“I’ve never seen him in my life. He’s a stranger to me. Or he was, till today.”

The bartender paused, as if considering the likelihood of Schmidt’s not knowing Eckermann.

“He’s a gentleman,” he said, imbuing the word with inscrutable humor. “A gentleman who’s never to be found without a lady. The things I’ve seen from him, it’s a wonder he’s not famous for his exploits.”

“Exploits?” asked Schmidt.

“I shouldn’t talk. It’s not correct.”

“He’s a lothario, you mean.”

“I’ll say no more. You can see, sir, for yourself.”

And with that he stepped back, taking Schmidt’s glass and refilling it, expertly. Schmidt in the meantime glanced back toward this Eckermann. Should he introduce himself? Acknowledge the fact of their mutual workplace? Eckermann’s lady—for all her self-possessing laughter, she seemed somehow his—stood now from the bar and retired, Schmidt presumed, to the powder room. For the first time that day, Schmidt could study his man from up close, sans distraction. He decided not to speak to him, to investigate instead what bonded Eckermann to him, and what, for good or ill, distinguished each man as his own sovereign self.

The comparison, in one sense, flattered Schmidt. His double was lean-jawed and wolfishly handsome, with an intensity of aspect—a burning of the eyes, a thoughtful crinkle of the brow—that was wholly prepossessing. Though wasn’t there something grotesque in his handsomeness, a leering, preening ugliness that underlay his charm? It was, he half-realized, his own timid resentments, reflected and refracted in the beauty of another. He felt a flash of violent hatred, a comet-streak of rancor in his stomach and his chest. He wanted, inexplicably, to beat him—to annihilate this double as a rival, as his foe.

The woman was returning. She crossed the gloomy barroom, illuminating all with her unyielding femininity. Eckermann turned, looked at Schmidt, shot a wink. Schmidt spun away, as if caught in some crime.

He glanced at his pint. It was empty again.

He set down his money and pulled back his chair and then left at a furnacecheeked, self-loathing trot. Night, to his astonishment, had already fallen. How long had he sat there, glowering at Eckermann? His wife would be waiting; she would doubtless be worried, and likely irate. His supper, what was worse, would now be cold.

He stumbled ahead, slowed by incipient drunkenness, and made it at last to his building. He climbed the grim stairs to his third-floor apartment, where Rudolph and Mathilda were awaiting him. The child, by now, would be sleeping. Mathilda would be sitting in the kitchen in her wrapper, her arms and legs folded, her face set in righteous, corrosive disdain.

It was as Schmidt had suspected. The apartment was dark, except for the

kitchen, where Mathilda sat stooped at the table—refusing, evidently, to ask him where he’d been.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Didn’t mean to be late.”

“Quiet,” she said. “Do you want to wake Rudolph? He’s finally asleep.”

“Sorry,” Schmidt repeated. He stepped into the kitchen, bumping, with his hip, the room’s only lamp. He caught it in time, but not before spitting a sharp, too-loud curse.

“Please,” she said. “Please. Just sit down and be quiet. Come sit down and eat.”

He stopped where he stood and considered his wife. Hers was a conditional beauty—a fineness that was squandered in these circumstances, the burdens of the housewife having snuffed the inner candle of her loveliness, which nonetheless burned, Schmidt reflected, when perceived from certain angles, or on those rare but sweet occasions when she drifted into happiness—when she laughed with the baby or, exalted by the turnings of her own capricious heart, broke into a folk-song from her childhood, a melody derived from the Arcadia of youth.

“Please,” she said. “Sit.”

No music, he knew, would now float from these lips.

“One moment,” he said. “I want to see Rudolph. To check on him first.”

He left her in the kitchen, where her silence spread and rose into the low hum of contempt.

The child was in his crib. Schmidt, though he regretted it, had a theory which explained his own detachment from his son, from the supine, snoring form of this defenseless, sinless child. The boy, little Rudolph, spent his days dandled and cosseted, engaging in wordless and burbling colloquies with the woman who, till recently, had dedicated everything to Schmidt, to the washing and the cooking and the labors of the marriage bed. But such a complaint, he understood, was superficial—was savagely self-centered and opposed to his own character. His true

complaint, the source of his discomfort and distrust, had to do with her motherly influence. Schmidt—as the father and main earner, the champion of his family in the huge devouring world—had forfeited, by necessity, the experience of witnessing his infant son’s formation. This was as it should be, by the standards of his day. And yet he found himself distrusting his own wife, resenting the allegiance between Rudolph and herself. There was, for example, the way she sometimes clutched him to her chest, turning him from Schmidt—giving her husband, quite literally, the cold bone of her shoulder as a bitter consolation. The child, Schmidt thought, had even begun to resemble her, to lose whatever traces of his own face he had seen there, in the blank slate of his son’s—had imagined, it now seemed, in the first quixotic blush of his paternity.

Rudolph sighed and gurgled, turning his head toward the wall of his crib. Schmidt considered reaching out to touch him, rub his chest, but then he reconsidered, afraid that he might wake him and inspire a fit of tears. The child sighed again.

Schmidt turned and stalked out, toward the kitchen and his wife.

A week passed uneventfully—uneventfully, perhaps, and yet laced with the venomous taint of suspicion. The smiles which Schmidt received within the work room and the lobby—even, on occasion, on the street—did little to convince him that he hadn’t been mistaken, that he wasn’t, in effect, being erased by these innocent grins. Each smile was like a slap, a reminder of that smooth, flirtatious operator, Eckermann. He never smiled back, averting his gaze and then hurrying on, as if by quickening his pace he might discourage all such errors and assert himself anew. He was Schmidt, his walk said. He was Schmidt. No one else.

He’d seen his double only rarely, from a distance in the work room: dazzling Miss Bierbrauer, slapping backs with nameless colleagues, passing with his graceful gait from one desk to another. Schmidt, when he saw him, did not watch for long. It was sickening enough to know that Eckermann was present, preening and ascending and impressing all he met.

On the following Thursday, Schmidt sat immersed in his work, at his desk, when Leo

Reuss turned to him, hissed for attention, and coughed up a morsel of scandalous gossip:

“You hear about Eckermann? About the Havermeier deal?”

“I haven’t heard a thing.”

“Word is he forged a few signatures. A councilman’s or senator’s or something. They’re saying Beckroth knows. Not only knows, but does not disapprove. The bastard is bulletproof.”

“That can’t be true,” said Schmidt. “That’s simply not true.”

Reuss’s grin was disconcerting: a jack o'lantern leer that suggested—in its jaggedness, the angles and cracks of its ludicrous wiles—some obscure point of satire. Was he playing a joke on his friend? Was Schmidt being lied to for reasons unknown?

“I assure you, dear Schmidt, that it is.”

Schmidt stood without a word and hurried off toward the toilets, where at least he could be free from Reuss’s grin.

At the far end of the aisle, a pretty young woman whose name he didn’t know looked up at him and smiled with eager openness.

“Mr. Eckermann,” she said.

He shuddered, rushing onward, refusing to acknowledge her or any other person.

Now, in the lavatory, assessing himself in its large, shining mirror, he was reassured to find he hadn’t changed—that these were his shoulders, and this was his hair, and this the same gaunt, inarticulate visage. He decided to leave early, to fortify himself with several drinks and then go home. He was feeling very faint, and it was three o’clock already. Any hope of productivity, he told himself, had gone.

He returned to his desk, collected his things, and left in a harried, undignified silence.

He was down in the street when he heard, once again, the other man’s name used against him.

“Eckermann, my boy!” the voice boomed. “Eckermann, you rascal, won’t you stop and chat a minute with your withered old employer?”

Schmidt turned but didn’t stop. It was Beckroth, the president, his hair raked back in great masculine waves, his step sure and brisk as he charged after Schmidt like some fearsome but gregarious policeman. He was anything but withered. He

was, instead, terrifying—the very form and figure of a huge, robust confusion, an error of the universe which hounded Schmidt and hinted at his secret obsolescence. The president loomed—he was ten feet away—and Schmidt turned and ran down an alley, a fugitive.

He sprinted through the streets, sightless to the glares of all he passed, and blundered at last through the doors of the inn, proceeding with a clatter to the barroom and his stool.

Alphonse was at the bar, slicing citrus wedges with a bright and curving blade.

“Afternoon, sir.”

“A shot,” Schmidt gasped. “A shot and a pint.”

“Right away, sir,” said the barman, turning with a private, knowing smile.

It was then that Schmidt swiveled and scanned the whole room. What he saw there should not have alarmed him, yet did. Eckermann was seated at the far end of the bar, flanked not by one, but by two laughing women. These ladies, two strangers, were dressed in a manner more flagrant, more revealing, than anything one found outside the slummiest of brothels. Skirts hiked high. Necklines plunged. Stilettos shot up at precipitous angles, tipping both girls toward the bar, their chests outward. Eckermann bellowed some hideous joke, the words of which were lost upon the seething, frantic Schmidt, and the women, as expected, tossed back their heads in a bright and gleeful preview of erotic satisfaction. Eckermann, they cackled, was a card.

Alphonse placed the shot and the pint on the bar, and Schmidt gulped them down without pausing to breathe. He drank as if the liquor might alleviate the horror, the rotten, toxic horror that was eating up his lungs.

“Another,” Schmidt said. “Bring another, Alphonse.”

He’d shouted this order, his voice a shrill yelp. But Alphonse had stepped out, and the barroom, but for Eckermann, was empty.

“And what is it, friend,” asked a low, steady voice, “that’s got you so upset?”

Schmidt turned. It was Eckermann—smiling at him, winking from between his laughing girls.

Schmidt couldn’t speak. He sat there and stammered, his face growing hot.

“Why don’t you join us?” asked Eckermann. “There’s plenty to go around.”

There was something in his voice—something in the dreadful exclusivity of plenty, the way this man was boasting of the harlots on his arm—that pushed Schmidt into action.

He seized the bar’s knife and charged blindly at Eckermann. The women shot upward and ran away screaming, clambering and scratching at each other as they fled. Eckermann, however, didn’t flee. He lifted his arms, spreading them as if to greet his double, to embrace him. Schmidt tumbled forth, stabbing wildly at his stomach, striking at his chest and outstretched arms. He hacked and ripped and tore and slashed until the mass of stubborn flesh and rigid bone that stood before him had yielded to a slouching sac of sanguinary chunks. His double had slumped to the floor. He was dead.

Schmidt stepped away and looked down at his hands, at the bloodstains on his shirtfront and his pants. No one could have seen him but the women, who had fled.

He threw down the knife and ran out, to the street.

It was, or should have been, the busiest hour of the day. But the streets were somehow empty, and as he scrambled down the pavements in his soiled and sopping clothes, he was fortunate, it seemed, to pass unseen by any witnesses. Outside his own building, he stripped to his undershirt, stashing his jacket and tie in an ashcan. His pants were still stained, though these he could dispense with on his threshold— stow them in a corner and produce some desperate alibi. A can of paint had fallen from a ladder as he passed. A drunken man had vomited upon him in the street. A meatball had slipped from his fork in the lunchroom, sullying his shirtfront and the fabric at his crotch. She should not, he’d insist, waste her time with the washing. The problem was his; he’d address it himself.

He crept into the living room, reduced now to his underclothes, padding in his

garters and his socks. Mathilda sat as always at the table in the kitchen, absorbed in a book, its title obscured by her soft pinkish hands. She had not, evidently, heard him enter. He observed her quiet face, illuminated now by the enchantments of her leisure, and flinched, for the first time since fleeing, with guilt. He felt nothing for Eckermann—only for himself, and for this woman he’d destroyed through the fulfillment of his rage. She was beautiful, he realized, and never again would he come home to find her, reading and at ease, with their child in its crib and a pot on the stove, bubbling appealingly with spices, fragrant steam. He took a step toward her. She sighed and looked up.

“Your clothes,” she said. “What happened?”

“An accident,” he told her, “with a workman and some paint. I had to throw it all away.”

She set down her book. The sense of his lying was palpable, dense, though she seemed—it was a miracle—incurious, at ease.

“Where’s Rudolph?” he asked.

“He must have stepped out,” said Mathilda. She smiled.

“Right.” Schmidt laughed. “But of course. He stepped out.”

He approached his wife and kissed her on the softness of her cheek, a whim so strange and surprisingly affectionate that she yielded to it instantly, her face offered up like a fresh, buoyant rose.

“I’ll go check on him then.”

The child lay asleep in the nursery. Schmidt saw his face and was filled, once again, with a horrible remorse—the shivering antithesis of all that had impelled him toward his savagery, his crime. The child sighed and burbled, rolling toward Schmidt in some vague whim of sleep. What did Schmidt see in the long, pallid brow; the thin, curving nose; the resplendent blonde hair? Was it, he wondered, himself? Or was it—it occurred to him, descending like a sickness—some phantom trace of Eckermann, surviving in his son?

He stepped away in horror, toward the kitchen and his wife.

He expected, in the morning, to be arrested with his breakfast. But when no one came knocking, and when no one apprehended him or seized him on the street, he began to assume some mistake had been made. In the blackest hours of night, he’d accepted what he now viewed as his destiny: his arrest; an accelerated trial; his execution, swift and final, by the even-handed state.

He took the lift as usual, though no one in the lobby or the elevator looked at him. No one smiled or nodded or mistook him for another. The lift rose and stopped, depositing Schmidt in the bustling work room. He stalked to his desk— unnoticed, unhailed.

For the first time in years, Reuss was not at his desk, which was tidier than ever—its papers piled and gathered, made anonymously neat. Schmidt sat and waited, unable to attend to any problems but his own. Soon, he understood, he’d feel a rough hand on his shoulder. He’d hear his name barked with retributive wrath. He’d yield up his wrists to their shackles, then stand, then go where they led him, his face dark with shame.

Several hours passed. Several days. Several weeks.

But no one ever came. And no one—not a soul—could restore him to himself.

When it comes to movie theaters, I can be a bit of a snob. I expect, perhaps even demand, that theaters project films in their proper aspect ratio from the highest quality source material with all audio levels and image values properly calibrated. If a lazy projectionist leaves the 3D filter on a 2D movie, I’ll know, and I’ll say something. (I am an absolute joy to be with.) As my recent trips to New Orleans cinemas have shown, no one else will care, especially the teenage employee tasked with listening to my complaint.

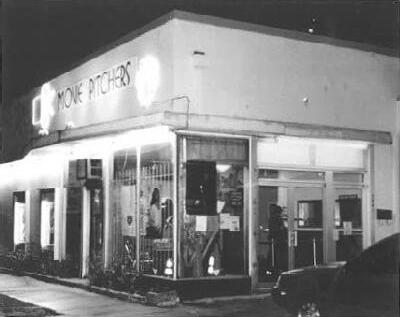

Given my admitted snobbery, you might expect a multiplex like the ArcLight in Los Angeles or a movie palace like the Egyptian to top my list of favorite movie theaters. These places revere the movies as an art form and place them ahead of anything else attendant to the theatrical experience, even previews, even rumbling subwoofers, even high fructose corn syrup. While those two certainly rank highly on my very short list, my favorite movie theater of all time is far less lofty. In fact, it’s about as far from a Snob’s Paradise as one could get. The Egyptian and the Cinerama Dome may be great places to see the greatest films, but they cannot match the carefree attitude and dubious glory of New Orleans’ Movie Pitchers.

Movie Pitchers was a four screen, second-run theater at 3901 Bienville St. that specialized in independent and art-house films. The first films that screened there in May 1991 give you a perfect sense of the range they would have on offer during their ten years of business: the B-horror flick Warlock and the Oscar-winning Italian nostalgia piece Cinema Paradiso. Duality dominated their marquee. A Cuban film such as Guantanamera would play next door to the latest Troma film, a quirky doc such as HandsonaHardbody would screen after the latest by Woody Allen or Almodovar. This sense of adventure extended beyond film programming to include regular midnight screenings of RockyHorrorPictureShow (complete with a shadow cast) and weekly performances by the improv comedy troupe Brown!, where cast member Dr. Ken Jeong entertained audiences before moving on to TheHangover and TheMaskedSinger. Such eclecticism may be old hat in the era of 20-screen multiplexes, but in the 1990s, this clash constituted an almost radical remapping of cinematic taste that obliterated the divide between high and low and replaced it with a more egalitarian and curious sensibility.

Today, movie theaters are just another one of dozens of goods and services that have experienced a bougiefication in which business owners seek to inflate the experience (and prices) of their product with higher-end versions of basic amenities. Over the last twenty years, we have seen concessions at movie theaters go from the

basic popcorn and soda to truffle parmesan kettle corn and bespoke cocktails, and seating transform from a glorified folding chair to fully reclining faux-leather seats with cupholders, trays, and a button to page the waitstaff. These developments seem like necessities as theaters compete with increasingly sophisticated home theater equipment, prestige television, and a deluge of streaming content, but all arguably distract from the films in one way or another. The prosciutto flatbread and boneless wings turn the auditorium into a restaurant, and the well-heeled artisanal baubles reduce this populist art form into an elite space to see and be seen, diverting eyes from the art on the screen toward the self-regarding gaze of the attendees.

The sad, overlooked fact is that Movie Pitchers was already doing most of these things touted as elite experiences in its own no-frills way. Unlike those other, fancier places, people came to Movie Pitchers for high-quality movies at video-rental prices.

Along with its programming choices, its humble appearance obscured just how much Movie Pitchers was ahead of its time. It sat in a nondescript building that kind of looked like a video store or insurance office from the outside and wasn’t much bigger on the inside. What it lacked in grandeur it made up for in grungy charm, economy, and, in true New Orleans fashion, booze.

Movie Pitchers had draft beer and a full-bar before it was cool, and they weren’t as concerned with technicalities such as legal drinking ages or photo identification as their current-day analogues. They also served some surprisingly tasty sandwiches that they would deliver during the movie on a paper plate. Granted, “delivery” meant an employee walking into the middle of the movie, blocking the projector, and shouting “Who had the ham and cheese?” Distracting perhaps, but it didn’t seem to matter all that much. After all, what was there to complain about when you were drinking a draft beer in a movie theater?

The screening rooms were the antithesis of impressive. In fact, they would horrify most people, as in they’d probably get themselves tested after just peeking inside. But that’s all part of the charm. The screen was half a baby step up from a bedsheet, the sound was just good enough to be audible, and the ceilings and projector were positioned so low that if anyone sat up straight their head would block the screen. But you didn’t need to sit up because each screening room at Movie Pitchers was furnished with nothing but couches and lounge chairs. Not the plush rocker kind, mind you: these were … what’s the phrase … lived in —mismatched, moldy-ass couches that every freak in Mid-City had done God knows what on over the years. (This probably explains why they never turned the house lights on, no matter what.)

Afterall,what complainabout weredrinking a movie

As for the screenings themselves, well, you never knew what was going to happen, even if you’d seen the movie before. At most theaters, Paul Thomas Anderson’s BoogieNights runs two hours and thirty-five minutes, plus previews. But at Movie Pitchers, it lasted nearly four hours one time because the film broke several times, each time requiring at least fifteen minutes to repair. Had this happened at any other theater, I would have been incensed, but here, it was barely even an inconvenience. It was what you paid for, part of a (literal) night at the movies. (Part of me suspects they broke the film on purpose to sell more alcohol.) I have two strips of film prints that broke at Movie Pitchers, and they are among my most prized possessions.

Yes, Movie Pitchers was a complete dump, but it was a film lover’s dump. For $5 a ticket, you could see all the foreign and arty indie films that didn’t play anywhere else in town other than the overpriced Canal Place in the French Quarter. In fact, the old Canal Place theater was Movie Pitcher’s mirror image, the twin separated at birth who gets to live in the rich neighborhood and attend the nicer schools. Both were four-screen theaters that showed art-house and independent films, although one sat atop a fancy shopping mall (Canal Place) and would get the films first, and some of the prints would eventually trickle down to the rundown building in Mid-City (Movie Pitchers). But for all its shiny, well-heeled surfaces, Canal Place did not have the warmth and charm of Movie Pitchers. They didn’t have the sofas that fit like a thrift-store glove. And they certainly didn’t have the drinks.

theater?

Some of these choices were deliberate, others were the result of necessity, happenstance, or obliviousness, but all of them added up to something that is virtually extinct in America: a blue-collar art-house theater. Every development in the theatrical experience has endeavored to keep these two concepts separate, to impose a strict duality in which high-class art and the general populace do not mix. What Movie Pitchers understood, perhaps on an intuitive level, was that movies are a popular art form and that people who may only have $5 to spend on a movie ticket would be interested in quality cinema and the community that attends it. To look at the theater and complain that it wasn’t fancy enough was to miss the point entirely.

Something this wonderful could only exist in New Orleans for so long. In the fall of 2000, the supermarket chain Sav-A-Center began construction on a new location across the street. They bought the ground Movie Pitchers stood on so that they could build an overflow parking lot, somehow believing that shoppers would be willing to cross the street with their shopping carts. Since Movie Pitchers didn’t own the building, there wasn’t much they could do. They tried to do something in court, but they got shot down right away. They didn’t have enough money to move elsewhere, and so the grungy cinematic utopia ceased to be. In a cruel twist of fate,

the Sav-A-Center didn’t last and the entire block is currently a dull and near-derelict corner of Mid-City.

Their closing was a strange shock to me. Just two days before their defeat in court, my first short film screened in the theater. It was an early dream come true, a film I made was playing in a real theater to a paying audience. And not just any movie theater: my favorite theater, and had it been scheduled for two days later, it would have been impossible.

The movie theater landscape in New Orleans is dramatically different. Canal Place went through several bougie makeovers and changes of ownership before the Prytania took over, and many other theaters have closed their doors. The Broad Theater opened in Mid-City in 2016 and openly stated that their intent was to capture the spirit of Movie Pitchers, only nicer. (They even have four screens.) They’ve been successful in this regard, but it’s not the same as watching a movie on a grimy couch holding a clear, plastic cup full of lukewarm beer in a greasy spoon of a movie theater. I have loved other movie theaters in my life, and I’m sure I’ll love some more in the future, but I’ll never love one as much as that absolutely glorious dump on Bienville called Movie Pitchers.

There was a party on a sylvan glade in rural Maryland roughly forty years ago. It was a Sunday afternoon, and the sound of a light rain falling on an enormous tin roof, accentuated a pastoral leitmotif. The house was a rambling structure — three stories with a wrap-around screen porch on each floor and an elevator in the middle that seemed if not incongruous, at least an eccentric addition to the early 20th century design. Yet it made the house all the more whimsical. The guests at the party were all attractive and imbued with that sense of confidence that they in fact belonged there. Yours truly did not, but no one seemed to mind.

Yet I can’t find one person to corroborate the story, nor can I remember a single person at the party. The memory is more a Renoir painting than a newsreel. Perhaps it was a dream or wishful thinking. Of course, it could have happened, as part of youth is wandering into strange and fantastic places willy-nilly. But there is no verification, and the question of whether the gathering actually took place is hardly the only mystery; there are also two conundrums that beg an explanation, more universal in their significance. The first is what neuroscientists call the unitary nature of experience. I can do mental time travel and go back to that party and form a major synthesis of modes of perception — visual, auditory, and olfactory — and no philosopher, psychologist or scientist knows how this is done. Secondly and most important, the memory of that party underscores the fact that all experience is subjective. While a disinterested observer would say we are all sharing an experience at the Wyvern Club, the fact is we are all experiencing the present moment very differently, as we did the last hour or the way we will experience the next hour. And again, we don’t know why. Neuroscientists and philosophers tend to call subjective experience consciousness, and as a matter of clarity, we will go with that definition even though there are others more complex. However we define consciousness, the essential brain/mind problem continues to dog us, and while there seems to be substantial agreement that the origins of consciousness are biological, there is little proof (if at all), and as a result, there are those in the field who think the mind/brain relationship is beyond our capacity to explain. Hence philosopher David Chalmers thirty years ago coined the term “the hard problem.”

We know about brain function, the 100 billion neurons connected by 100 trillion synapses. The brain is its own universe. And we know how different regions work; for example, the four lobes of the cerebral cortex. According to neuroscientist Eric Kandel, recipient of the Nobel prize for his work with memory, the frontal lobe governs “social judgements, planning and organization of activities, … language, control of movement and a form of short-term memory called working memory. The parietal lobe receives sensory information about touch, pressure, and space around the body, and helps integrate that information into coherent perceptions.

The occipital lobe is involved with vision. The temporal lobe is involved with auditory processing and aspects of language and memory.”1 Deep in that cerebral cortex also lies the ganglia which regulates motor performance, the hippocampus which stores memory, and the amygdala which deals with emotion.2 All fine and good — but we still don’t know why or how this translates into subjective experience.

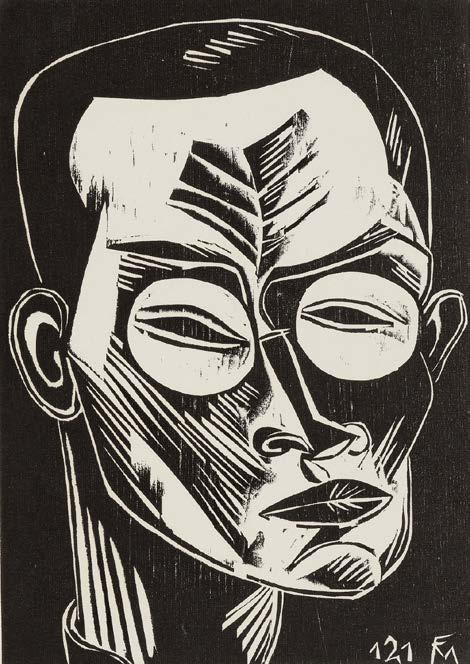

A good question that we moderns are embarrassed to ask is, is there a “ghost in the machine?” Is consciousness separate from the quotidian neural activity? Seventeenth century natural philosopher Rene Descartes thought so. Human beings, he averred, are made of two substances. The res externa is our physical stuff, including the biological brain. The brain is responsible for reflex actions and motor skills. The rescogitans are the non-physical properties that reflect the soul and our ability to reason and reflect, i.e., our subjective experiences. Descartes posited that the two realms connected through the pineal gland, a pretty good guess for a 17th century mathematician, since we now know the pineal gland regulates sleep. The theory of a bifurcated existence was embraced by the church since it reinforced the nature of the soul. Sir John Eccles, Nobel laureate neurobiologist, espoused dualism since it squared with his Catholic faith.3 Yet dualism has largely been written off by neural scientists and philosophers as new agey, anachronistic, or just unscientific.

The materialist monist argument (that the brain and mind are identical) started during the Enlightenment when Cartesian duality was put into question by a science based more on empirical observation than logic and deduction. Franz Joseph Gall, a Viennese medical doctor, argued that all mental activity is biological and different regions of the brain serve specific purposes. It was revolutionary as a thought, but science tends to go two steps forward and one step back. When Gall worked in a Vienna insane asylum, he concluded that sadists all had a bump above the left ear (I don’t know the sample size of sadists), but the next step was examining the bumps on patients’ heads and the pseudoscience of phrenology was born. Phrenology lasted well into the 19th century and was ultimately discredited, but Gall’s theory of functionality was vindicated by the study of damaged brains. For example, in 1861 French surgeon Paul Broca examined a shoemaker named

1 Eric Kandel, InSearchofMemory, (New York, 2006), 111.

2 Kandel, 45.

3 Matthew Cobb, The Idea of the Brain, (New York, 2020), 339

Leborgne, who twenty years earlier had suffered a stroke. While Leborgne could understand language, he could not speak. He died a year later, and in the postmortem Broca discovered a lesion on the frontal lobe of the left cerebral hemisphere now called Broca’s area. Upon studying the brains of eight diseased patients who had been unable to speak, Broca proclaimed, “We speak with the left hemisphere,” another breakthrough.4 Of course, the divided brain has opened a whole intellectual can of worms, with scientists, philosophers, pop theorists and public intellectuals joining the fray. Suffice it to say the left-brain/right-brain thing is very real, but some of the theories on how this plays out begs credulity.

Agoodquestionthatwemodernsareembarrassed toaskis,istherea“ghostinthemachine?”

Yet on the issue of identifying consciousness, the biological argument has come down to a matter of faith. Philosophers are invested because the hard problem deals with various branches of the field — epistemology (theory of knowledge), phenomenology (theory of experience), and ontology (theory of being). Philosopher John Searle posits with grand certitude, “Consciousness is caused by lower-level neuronal processes in the brain and is itself a feature of the brain.”5 Neuroscientists look to a biological solution simply because there is a clarity in finding the place where consciousness lies, in other words where it can be proven. This goes back to Sigmund Freud who believed his id, ego and super ego had to be based on some “organic structure.”6 It was simply a matter of time for it to be unveiled. Yet by the mid 20th century many in both disciplines threw in the towel, convinced the problem was intractable.

Nevertheless, research into solving the Hard Problem enjoyed a boost when Francis Crick of the double helix fame decided in 1976, at the age of sixty, to devote

4 Kandel, 122.

5 John Searle, TheMysteryofConsciousness, (New York, 1997), 17.

6 Kandel, 46.

the rest of his life to the “biological nature of consciousness.”7 Crick started with the materialist position that our thoughts and feelings derive from “a vast assembly of cells and their associated molecules.”8 Eric Kandel surmised that Crick’s efforts until his death in 2004 were only able to “budge the problem a modest distance,” but the method is worth noting.9 The key, Crick believed, was finding neural correlates to the unity of conscious experience. Neural correlates and unity of consciousness are both jumping-off points — correlation can lead to causation, and unity of consciousness can offer clues to the holy grail of subjective experience. Crick’s last paper, which he wrote with Christof Koch in 2004, focuses on the claustrum, located beneath the cerebral cortex. The claustrum is a connecting tissue, and according to the paper, plays the role of a conductor of an orchestra, binding neurons together. There are two problems with the theory, however. Since the paper was published, the notion of the claustrum as the engineer of consciousness has been largely disproven. And while neural correlates have been established, like cells firing when a subject was presented with a picture of a celebrity, we don’t know why the individual had that particular response, and another person would have an altogether different response.

One of the more promising ideas coming out of Crick’s research is the notion that consciousness is derived by neurons linking up in various and specific ways. Neurobiologist Gerald Edelman has argued that consciousness is widely distributed across the cortex and thalamus, with neuronal groups looping back and forth between the respective regions.10 With Giulio Tononi and Christof Koch, he has developed an Integrated Information Theory, which

7 Kandel, 377

8 Searle, 21.

9 Kandel, 377.

10 Susan Blackmore, Consciousness,AVeryShortIntroduction, (Oxford, 2017), 46.

essentially attributes consciousness to the ability of neurons to bond into a critical mass for integrating information. They have also developed a mathematical formula for explaining the process, which is well beyond my grasp.

There are also concrete experiments that evince promise regarding the amygdala as a portal for understanding the kind of brain activity that produces consciousness. When Eric Kandel presented pictures of fearful faces to a group as both conscious and unconscious stimuli, it lit up the amygdala, which activates our fight-or-flight instinct. Yet one can argue this goes back to Descartes’s res externa, since the reaction is the visceral kind rather than a reflection or musing; but it may be a start.

One of the more compelling monist theories, introduced in the 1980s by psychologist Bernard Baars, was called the Global Workspace theory. Think of the global workspace as a stage with the spotlight shining on that which we are consciously thinking about. The background is dark, but there are thoughts ready to fall into the spotlight, which can only handle so many thoughts in the foreground at one time. Every new thought enters the spotlight, and the old thought retreats into the darkness. The audience are the unconscious part of the brain. A beautiful metaphor but hardly verifiable.11

But it does raise the question of Freud’s unconscious as a biologically determined phenomenon. German neuroscientist Hans Kornhuber conducted a study in which he asked volunteers to move their right index finger. After attaching an electrode on the skull, he found that the volunteers thought about the movement for a second before they acted. He called this readiness 11 Blackmore, 48.

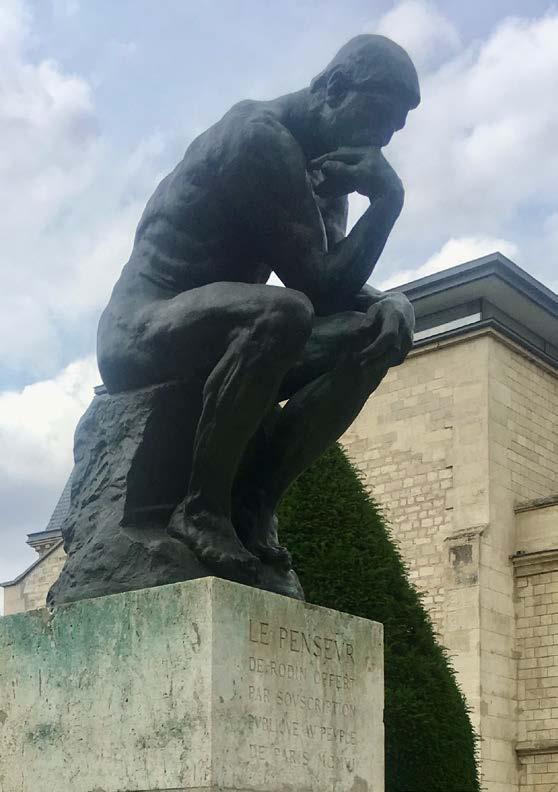

Le Penseur by Rodin

Photo by Shay Steckler

Le Penseur by Rodin

Photo by Shay Steckler

potential. Benjamin Libet of the University of California conducted the same experiment with volunteers and confirmed the readiness potential at a second before the action. Nevertheless, through reconfiguring the experiment, Libet found there is brain activity 200 milliseconds before the conscious decision to bend the finger or wrist. In other words, the mind knows things that we don’t know that it knows. Hence Libet raised not only the question of free will but brought back the dualistic ghost in the machine, which he called a “cerebral mental field.”12

David Chalmers, the rock star of the mind/brain problem, is the accepted guru of the new philosophy of mind. Chalmers made dualism respectable again and has gone after the materialists as being reductionist, or rather facile in their confidence in solving the problem through searching for elusive physical processes. The argument is that if consciousness lacks all physical qualities, then a physical or biological panacea for solving the problem is out of scientific reach. For Chalmers consciousness just IS like energy and matter,and while the brain does things that the brain does, consciousness is an added dimension.13

Which gives rise to the theory of panpsychism, a theory that consciousness is inherent in the atomic structure and therefore part of all matter.14 Human beings simply have more of it than inanimate objects and other living forms. In this case the brain acts as TV antennae or a satellite, receiving consciousness and broadcasting it out.

Two philosophers of mind, Susan Blackmore and Daniel Dennett, simply reject the notion that consciousness exists, that it reflects our own desideratum, a fantasy we want to believe. According to Blackmore, “Consciousness is an illusion: an enticing and compelling illusion that lures us into believing that our minds are separate from our bodies.”15 For Dennett the whole question comes down to human evolution; a combination of biological evolution, brain plasticity and finally cultural evolution (in which I don’t have to reinvent the wheel myself) have allowed us to thrive. The brain is our hardwiring and processes all the information that comes in (i.e., the software). According to Dennett, “human consciousness is a huge complex of memes [impressions] …that can best be understood as the operation of a von

12 Cobb, 356.

13 Blackmore, 45

14 Searle, 156.

15 Blackmore, 130.

Neumannesque virtual machine…”, alluding to mathematician and physicist John von Neumann, along with Alan Turing, inventor of the computer.16

Mathematician Sir Roger Penrose and scientist Stuart Hameroff claim the computer analogy is not even metaphorical, that tiny microtubules found in brain cells are in fact quantum computers that create coherence with information coming in.17 The notion of the brain as a computer has many adherents, and that’s a rabbit hole I avoided. But there is a certain irony in the great hope of Artificial Intelligence, that by building a machine that could achieve singularity (consciousness), it could prove the materialist right, assuming the machine replicates functionality of the brain. It could also settle the monist/dualist controversy for good, forever relegating Descartes to the guy who tortures sixteen-year-olds with Algebra II.

Yetontheissueofidentifying consciousness,thebiologicalargumenthas come down to a matter of faith.

But there is too much out there that defies reductionist materialist theories. We settled the question that experience is subjective, but that does not exclude psychic connections between people. After all, that’s what leads them to the altar (or a hotel). I woke one morning to a feeling of profound ineffability, yet it was peaceful, even perhaps exhilarating. I later found out from my friend’s aunt that he had died at that time of an awful cancer. He had also suffered from mental illness since his early twenties. He was a prince of a fellow and escaped the shackles of this earthly existence. This kind of experience, while not verifiable, is not uncommon. I hardly think brain matter, or a computational network, can achieve this.

My conclusion is that Descartes’s ghost in the machine is no more preposterous than biological materialism or even panpsychism. What if consciousness drives brain activity or that brain activity is a conduit to a level of thinking beyond

16 Daniel Dennett, ConsciousnessExplained, (New York, 1991), 210.

17 Blackmore, 45.

the physical self? My friend DeGioia is college president by profession but a philosopher by training. According to his tenets of philosophical thinking, when we face a hard problem where there is no clear way to navigate the essential question (like what is consciousness?), our only solution is to make a choice. And not making a choice is a choice and perhaps the wisest one. But for those of you who like me cannot avoid this question, which gets to the essence of our human existence, I wish you Godspeed and good luck.

One of my greatest thrills as a new parent is bonding with my child over music. I inherited a stack of CDs from the Mileys titled Rockabye Baby: a series of rock classics translated into lullabies with tubular bells and xylophones. Scratched, scuffed, torn, and taped, this archive has been clearly loved over the years. Every day at 4:45, I pick my daughter up from daycare, pop in a disc, and begin her music education. Here is an abridged ranking of some hits and misses from the collection. ClickonthebabysleepingonthemoontolistentothesongonYouTube.

4 5

Nirvana - I had high hopes for this album. Acoustic interpretations of Nirvana are limitless, including their own legendary MTV Unplugged in New York and Patti Smith’s rich, playful, banjo-based cover of “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Slowed down and tapped on a marimba, Nirvana somehow feels both lethargic and unsoothing. One rattle.

Nine Inch Nails - Trent Reznor is a versatile artist unafraid to bend genres, so I expected his music to lull more gracefully. This haunting interpretation is better suited to the Exorcist soundtrack than a nursery, and it was hard to reconcile the lyrics that played in my head. “Head like a Hole” works better than others when paired with lyrics from the Miley Cyrus Black Mirror collaboration: “I’m full of ambition and verve, I’m going to get what I deserve.” Two rattles.

3

Guns N’ Roses - These rock anthems pleasantly surprised me as lullabies. The shrieking vocals and electric guitar slash through a music box and emerge innocently cheerful arrangements. They also peppered in some chirping and croaking, showing not telling us we’ve reached the “Paradise City.” Three rattles.

Pink Floyd - These covers drifted readily into dreamland, and the melodies and lyrics contain multitudes of emotion. The ticking clocks and resonant chimes from the opening of “Time” sync up seamlessly when played in unison with the original, as if both were written for The Wizard of Oz. “Wish You Were Here” is a bittersweet ode to attachment and object permanence, two concepts we all must reckon with in our early years. Four rattles.

2

1

Pixies - This album has something for everyone. “Monkey’s Gone to Heaven” has a fun counting segment. “Debaser” provides an opportunity for chanting French nonsense wrathfully or gleefully, depending on the mood of the day. “With your feet on the air and your head on the ground,” singing “Where Is My Mind” in unison with a screaming baby is a quintessential early parenting moment. Five rattles.

Butters will turn eighty-four next month. She has been deaf for the last twenty years of her life, and recently her vision has begun to falter. When the cold air of this past winter arrived, her back became arched and crooked and her walk more delicate. Her legs wobbled and quivered in the first few hours of every morning. With the warmer weather, her balance has improved, but she still struggles with standing and supporting her own weight. Her roommate Omar is seventy-eight. He still moves well, but his hearing is also fading. He no longer notices when Butters rises from her bed in the morning and waddles gingerly down the hall to begin her day with a drink of water before breakfast.

My wife and I have been taking care of Butters since her original family abandoned her a number of years ago; Omar has been with us since his mother in Mississippi decided to give him up for adoption shortly after his birth.

Butters and Omar are our two Shih Tzus, and their lives are coming to a conclusion. Like many their age, Butters and Omar have their good and bad days, the difficult ones characterized by excessive bouts of sleeping, sometimes nearly twenty hours a day. On these days, Butters will get out of bed to urinate on the kitchen floor before returning to her bed of choice. She has three now, one in the TV room, one in the bedroom, and the other one in the office with the heating pad. It’s been a good ride, but they’ve both entered the twilight of their lives, and my role has changed from one of trainer and adviser to caretaker and nurse, trying to provide a warm, comfortable environment for them to live at peace during their final years, as we all brace ourselves for the inevitable.

Each day, their health declines. Omar struggles to jump on the couch now. Butters needs to be carried down the porch steps. Omar’s back legs shake. Butters stares vacantly for extended periods at the bottom of the refrigerator. During these moments, I’m reminded of a line at the end of KingLear. Kent, Lear’s loyal servant to his final hour, gazes in disbelief at the numerous lifeless bodies strewn about the stage as Lear enters holding the limp body of his favorite daughter. “Is this the promised end?” Kent asks Lear’s son-in-law, Albany.

Sometimes I ask this directly to Omar, but he can’t hear me anymore, and Butters is too busy mindlessly licking the floor to bother to acknowledge me.

On the morning of Boxing Day this year, Omar woke up wheezing and coughing, struggling to catch his breath, and it was evident that what we'd thought was merely a respiratory infection was something far more serious. We took him to the emergency vet, and after various tests, bloodwork, and an overnight stay, we learned that Omar had congestive heart failure, a common ailment for small dog breeds. With medication, they told us, Omar could live another six to eighteen months. The north damp wind blew steadily the next day when we picked him up, and a feeling of dread pervaded the car as we drove past the faceless chain stores and naked trees on the way back to our house. After an oxygen treatment, Omar appeared calm and thankful to return. He settled into his chair. I put his medicine on the kitchen table, and my wife cleaned up the puddle of Butters’ urine in the living room.

Butters remained unfazed by the recent news of Omar’s condition. I envied her inability to understand that, as John Irving wrote at the end of The World AccordingtoGarp, “we are all terminal cases.”

I was afraid that this might happen when my wife originally brought Butters home in January of 2020, a couple of months before the world shut down. Her original elderly owners could no longer care for her and put her up for adoption. I never agreed to take in this dog. It was January. The dog was twelve. “Maybe she lives a year or two, just enough time to form an attachment, and then…,” I said to my wife. “Omar is getting old, too. It seems that we are setting ourselves up for unnecessary sorrow.” I said that on a Sunday. On Monday afternoon, Butters was sleeping on our couch and a new dog dish had been added next to Omar’s.

She didn’t answer to Butters back in those days. She didn’t answer to any title because she was already deaf when we got her. Her birth given name was Diamond. My wife and I didn’t want our dog to be mistaken for an exotic dancer, so we changed her name. Diamond came with papers from the American Kennel Club and a box of clothes, including dog booties for walks on rain-soaked sidewalks and an LSU sweater for football season. Apparently, she had lived a pretty charmed life.

“You’re Butters, now,” I told her. “Welcome to retirement.”

Like many of us during those early months of the pandemic, Butters had an unsettling 2020 and a difficult time adjusting to her new life. Zoom meetings and masks had nothing to do with Butters’ unease, though. It was adjusting to her new Uptown life after spending her entire existence with her family in Gentilly that was at the root of her anxiety. The Prozac our vet prescribed seemed to put her at ease, and, eventually, Butters began to embrace each first day of the rest of her life.

Two years ago, our vet, Dr. Woods (not his real name), made another discovery that also had a significant impact on Butters’ quality of life.

“I think she’s in an incredible amount of pain because of her teeth. Many are loose, and some are clearly decayed,” he said. “I think we should pull them.” Butters went to sleep and woke up with twenty-six fewer teeth, but Dr. Woods insisted that this was the proper decision. “She’ll feel so much better,” he assured us. “I think I may have bought her an additional two years of life.” At this point, Butters’ incontinence had already become an issue.

“We better stock up on a few more old dish rags,” my wife said.

“Yep. I guess we’d better,” I replied.

Our vet has known Omar since he was a puppy. A friend originally recommended this doctor because of his naturally calm demeanor and his tender, mild-mannered disposition. “He loves animals so much, and he reminds me of my grandfather,” she told us. “You'll love him.”

That was over twelve years ago, seventy-eight in dog years. When Omar approached middle-age, Dr. Woods used to scold us about his weight. “He’s one and a half pounds overweight. That’s like you gaining twenty pounds in two years,” he’d tell us.

My wife would get defensive. “He goes on two walks twice a day,” she’d tell him. “We do give him people-food but only carrots and celery and the occasional mushroom.” With a partially raised left eyebrow, our vet would just listen incredulously before changing the subject. Upon leaving, I’d tell my wife not to

worry. I’ve gained a few pounds since the last visit as well. We’re middle-aged now. I understand what Omar’s going through.

“Omar’s not fat,” I’d finally say as we approached the car. “He’s just big-boned.”

Besides the occasional fat shaming, Dr. Woods has treated Omar and us well over the years. We used to see him twice a year, but because of Omar’s recent diagnosis and Butters’ overall decline, we’ve been going to the vet once a month now. I’ve looked at my dogs differently in their later years, but recently I’ve noticed some changes in my vet as well. His hair has thinned. He has begun using a cane when he walks into the waiting room, and, during this last visit, he repeated a key phrase numerous times when giving us specific instructions for administering Omar’s meds. This worried me.

“Are you hearing me? The Dioxin he gets twice daily. Just give him the Pimobendan once a day and only a half tablet of the Spironolactone every other day. Are you hearing me?”

“Yes, sounds good,” I answered.

“Remember, this is not a cure, but only a treatment. Are you hearing me? This will just buy him some time. Are you hearing me? It will not shrink his heart.”

I heard you. Omar’s practically deaf now, so I’ll let him know, and I’ll be sure to tell Butters after she stops staring at the wall and licking the carpet.

That’s my life these days, mopping up dog piss and washing out old dinner towels and placing them in our canvas bag in the laundry room devoted to this new task in my life. I wake up, get ready for work, clean up puddles, then walk out the door. My wife is an occupational therapist at a nursing home, and her work life and home life seem to be blending now. I’m not entirely sure how she copes. My upper school students may be noisy at times or uninterested or distracted or sometimes even asleep when I’m teaching. Most of them remember my name, though, and at least they’re able to use the bathroom without any outside assistance.

Growing up in New England, I became a Boston Red Sox fan as a kid well before they started winning World Series titles and enjoying any success. During the final game of the season, the radio announcer would read a passage from the late Bartlett Giamatti, former president of Yale and the baseball commissioner best remembered for banning Pete Rose from baseball and the Hall of Fame for gambling. Giamatti’s essay, “The Green Fields of the Mind,” is about listening to baseball on the radio as a way to stop the inevitable passage of time. More specifically, he writes about the last game of the 1977 season when a Red Sox win would assure them a tie for first place with the Yankees. As long as the Sox season continues, he writes, “school will not start, rain will never come, sun will warm the back of your neck forever.” When the Red Sox lose the game, Giamatti writes about baseball leaving us to “face the fall alone.” Giamatti had just turned forty when he penned this piece and mentions how “there comes a time when every summer will have something of autumn about it.”

It is spring now, but I’m beginning to understand. Omar’s on the couch sleeping soundly. Butters is in her third bed that’s been moved to the screen porch for the warmer spring weather, and Dr. Woods is probably prescribing medicine to an aging pitbull. I flip my calendar to April and glance past Butters’ bag of dish rags to the top shelf that holds Omar’s pill bottles. There’s November over by the dryer, lurking in the shadows, with a smirk on his face, reminding me of what awaits when the seasons turn and the final out is recorded.

“Are you hearing me?” he asks.

I do, but summer is coming, and Omar needs his second dose of pills for the day, and the refrigerator is just too damn intriguing for Butters to stop staring now. Fall will have to wait.

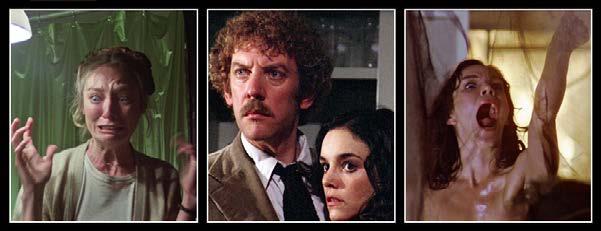

The first thing you might notice about the spore blobs floating toward Earth is they look a little coronaviral. Settling into a variety of botanical forms, they quietly but efficiently take over the San Francisco landscape. We zoom in on a playground, where a teacher is encouraging the children to pick the pretty red flowers and take them home. A priest on a swing glowers at the group, and the priest is Robert Duvall. The camera shifts to his POV for a second, and then we never see Robert Duvall again. This odd little cameo is the first of many disorienting details in InvasionoftheBodySnatchers, an underappreciated sci-fi classic that builds horror not by showing us alien monsters (though there’s a bit of that) but by taking the utterly familiar and tweaking it just so. You think you know Robert Duvall but you don’t.

Our heroine is a Department of Health lab worker named Elizabeth (Brooke Adams), who plucks one of these invasive plants and brings it home to show her cuddly but sports-distracted boyfriend Geoffrey. (You know this is the ‘70s because Elizabeth and Geoffrey own a lot of macrame plant hangers.) The next morning she wakes up to find Geoffrey acting very different — cold, distant, and wearing a three-