In our last edition of Summit, we asked you to share your thoughts about this magazine, MRU’s signature community publication — what you liked, what you thought we could and should change; the content, the format, the delivery method.

In general, we wanted to know from you — our readers — your thoughts as you read through our biannual magazine. We appreciate your responsiveness, including the many helpful suggestions and comments. We are studying the results to help shape future issues.

We learned 75 per cent of respondents believe Summit helps them feel informed about what is happening at MRU and 77 per cent are proud of their association with the University. Another take-away? Sixty-six per cent prefer to receive the print edition, while 26 per cent would like to see Summit exclusively online. Encouragingly, 65 per cent of you read most or all of each issue.

More than 85 per cent of respondents either agree or somewhat agree that the magazine presents info and stories on issues and subjects they care about. You told us you are particularly interested in health, current and trending topics, science/technology and things you didn’t know about MRU. So, as a start, we’re responding in this issue with these provocative stories:

» One Mount Royal alumna discovered the positives and the pitfalls of tracing family lines through DNA testing. Imagine finding out that the people you thought were your relatives … aren’t?

» We also cover endurance running. What makes people run long distances? We’re not talking about a jog around your neighbourhood or even attempting a marathon; in this edition we share the story of an ultramarathoner — someone for whom the standard 42-km run doesn’t cut it. What drives them to go the (really long) distance?

» And of course, with MRU in Calgary, we’re all certainly familiar with the modern-day cowboy. But when we take a step away from the carefully cultivated image of the “Hollywood” cowboy, we find a culture that goes back thousands of years and is defined in unexpected ways. All this and many other items in this edition of Summit

Enjoy!

Tim Rahilly, PhD president and vice-chancellor Mount Royal University

Tim Rahilly, PhD president and vice-chancellor Mount Royal University

DNA testing can reveal a lot about our backgrounds . . . sometimes more than we expected. From unlocking ancestral secrets to navigating the legal terrain of criminal investigations, discover the positives and pitfalls of tracing your heritage, and just how accurate the results may (or may not) be.

What’s holding back the electric vehicle?

From cold weather challenges to public policy and problems with mineral extraction, four of MRU’s brightest give their take on what’s keeping the EV revolution stuck in the slow lane.

The jeans and plaid shirts of the Calgary Stampede belie a history much more diverse and widespread than what classic films and television shows might portray.

Going the extra, extra mile

The sport of ultramarathon is exploding, with more participants toeing the starting line of races than ever before. But why would anyone want to take part in these grueling painfests? Explore the art and science behind pushing physical and mental limits, one step at a time.

Erin Creegan-Dougherty

Bachelor of Business Administration — International Business, 2023

Doug Dirks

Sports Administration Diploma, 1983

Lyall Frederiksen Criminology Diploma, 1989

Sierra Hope

Bachelor of Health and Physical Education — Ecotourism and Outdoor Leadership, 2023

Carly Kolesnik

Advanced Athletic Therapy Certificate, 2018

Ally Lo

Bachelor of Health and Physical Education — Athletic Therapy, 2018

Tim McGough Criminology Diploma, 1989

Dave Proctor

Massage Therapy Diploma, 2000

Spirit River Striped Wolf

Bachelor of Arts — Policy Studies, 2023

Theresa Tayler

Bachelor of Communication (Applied) — Journalism, 2005

Sarah Twelvetree

Physical Education — Athletic Therapy Diploma, 1998

Ryan Wenger

Bachelor of Business Administration — General Management, 2019

Summit writer Rachel von Hahn went to great lengths, 90 kilometres in fact, to go behind the scenes of the fascinating world of ultra distance running. Get up to speed on page 32.

EDITOR

Michelle Bodnar

BCMM (APPLIED) ’05

PRODUCTION

MANAGEMENT

Deb Abramson

JOURNALISM DIPLOMA ’77

MARKETING AND EDITORIAL

CO-ORDINATION

Bailey Turnbull

COPY EDITOR

Matthew Fox

ART DIRECTOR

Michal Waissmann

BCMM (APPLIED) ’07

DESIGN

Leslie Blondahl

BCMM ’14

Astri Do Rego

Mike Poon

Michal Waissmann

Chao Zhang

PHOTOGRAPHY

Philip Forsey

Vanessa Garrison

Maximillian Krewiak

Vera Neverkevich Hill

Cary Schatz

LAW ENFORCEMENT DIPLOMA ’89

Chao Zhang

ILLUSTRATIONS

Chidera Uzoka BCMM ’26

Carl Wiens i2iart.com

CONTRIBUTORS

Michelle Bodnar

Sade Dunn

Matthew Fox

Christina Frangou

Peter Glenn

Erin Guiltenane

Dave McLean

Betty Rice

RADIO AND TELEVISION BROADCASTING DIPLOMA ’89

Rachel von Hahn

Bryan Weismiller

BCMM ’13

Ryan Wenger BBA ’16

DIRECTOR, MARKETING

Dave McLean

DIRECTOR, COMMUNICATIONS

Gloria Visser-Niven

DIRECTOR, ALUMNI RELATIONS

Eleanor Finger

Summit is published in the fall and spring of each year. With a circulation of approximately 64,000, each issue features the exceptional alumni, students, faculty and supporters who make up the Mount Royal community. Summit tells the University’s ongoing story of the provision of an outstanding undergraduate education through personalized learning opportunities, a commitment to quality teaching, a focus on practical outcomes and a true dedication to communities. Celebrate yourself through Summit

ISSN 1929-8757 Summit Publications Mail Agreement #40064310

Return undeliverables to: Mount Royal University 4825 Mount Royal Gate SW Calgary, AB, Canada T3E 6K6

Enjoy Summit online by visiting mru.ca/Summit.

If you would like a print copy delivered to your home or office, simply email summit@mtroyal.ca.

Mount Royal University is located in the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of the Treaty 7 region in southern Alberta, which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina and the Îyâhe Nakoda. The city of Calgary is also home to the Métis Nation.

Sustainably yours.

A student’s diet is stereotypically characterized by a breakfast of leftover pizza and late-night ramen dinners. Fast and cheap food has become so closely associated with student life that it’s emblematic of the university experience. Thanks to a generous gift from Canadian Natural, MRU is tackling chronic food insecurity among students. In January, MRU launched the NourishU program to address the causes of food insecurity and help students develop better eating habits. NourishU is free, teaching students how to budget their grocery bill and cook well-rounded meals among the demands on their time and finances. Students attend a three-hour class to cook meals with a professional chef and learn about scouting grocery store savings and that eating healthily doesn’t have to be expensive. The program, developed in partnership with MRU’s Wellness Services department and with funding from Canadian Natural, is just one of the ways MRU and the Students’ Association of Mount Royal University are working to help address food insecurity on campus.

A GREAT PLACE TO WORK

MRU ranked 19th among Canada’s best employers

Forbes released its annual list of Canada’s Best Employers in January and MRU stands out as the only Alberta post-secondary institution to make the top 50. Working with market research firm Statista, Forbes surveyed more than 40,000 people working for Canadian companies that employ at least 500 people. Survey respondents were asked to rate their employer based on a range of criteria, including salary, gender pay-equity, work flexibility, opportunities for promotion and on-the-job training. Participants were also asked if they would recommend their employer to others, and were given the chance to rate other employers in their respective industries. “Universities are exciting and stimulating places to work and we are proud to have been highlighted in this way,” said Dr. Tim Rahilly, PhD, MRU president and vice-chancellor. “It demonstrates perhaps to the rest of the country what we already know — that Mount Royal is a really great place to work and build a career.”

CROSSTOWN SMACKDOWN

The 2024 instalment of the annual Crowchild Classic delivered the ultimate fan experience while showcasing some of Calgary’s best post-secondary athletes. More than 10,500 students, faculty, staff and community members from MRU and the University of Calgary raised the roof of the Scotiabank Saddledome on Jan. 24 to cheer on their respective men’s and women’s hockey teams. The event marked the 10th year of the games between Calgary’s Crowchild Trail rivals.

The men’s team kicked off the double-header with a game that needed a shootout to decide the winner. Ultimately, the Cougars triumphed 3-2. For the primetime matchup, a ceremonial puck drop featuring Mayor Jyoti Gondek, MRU President and Vice-Chancellor Tim Rahilly, PhD, and UCalgary President and Vice-Chancellor Ed McCauley, PhD, launched the women’s game. It was a wellmatched, hard-played contest that saw the Dinos shut out the U SPORTS national champion Cougars 2-0. While the games at the ‘Dome are one of the highlights of the season, the Crowchild Classic Medal is awarded to the school with the most wins each year in hockey, basketball, volleyball and soccer. The Cougars are now two-time reigning champions.

MRU has unveiled its new Bachelor of Aviation Management, a four-year degree program that gives students the skills to find a rewarding career in the aviation sector in operations and management roles with airlines, airports or other aviation-related businesses. This program, the first of its kind in Alberta, offers two different concentration pathways: Flight Crew Operations, which offers an optional commercial pilot and multi-engine instrument rating stream to prepare students to be a professional pilot while also being ready for management opportunities as their flying career develops; and Aviation Operations, which focuses on developing management skills and provides specific aviation business content. Students will learn about the many complex issues affecting global operations, including economic and environmental sustainability, financial operations, logistics and best practices for managing people and processes in the aviation industry.

“Mount Royal is proud to be playing a vital role in advancing the aviation sector and its importance to the future economy of Alberta,” said Dr. Chad London, PhD, provost and vice-president academic at MRU.

The Bissett School of Business will admit 40 students annually, with the first cohort beginning in Fall 2024.

“There is a pilot shortage worldwide, so there is an enormous demand for education in this sector. We have also received feedback from industry that says there is a need for people with a business background along with an understanding of aviation to work in many other leadership roles,” said Dr. Kelly Williams-Whitt, PhD, dean of the Faculty of Business and Communication Studies.

IMPACT RECOGNIZED

Alumnus Spirit River Striped Wolf and Associate Professor Liza Choi, PhD, were each named one of 2024’s Compelling Calgarians. In 2020, Striped Wolf became the first Students’ Association of Mount Royal University president of Indigenous ancestry. Since then, he has graduated with a Bachelor of Arts — Policy Studies and continues to dedicate his time and knowledge to improving the lives of Indigenous Peoples through his activism, advocacy, volunteering and leadership.

Choi has impacted the lives of hundreds of students in the School of Nursing and Midwifery through the English-as-an-Additional-Language Nursing Student Support Group. Her work was recognized by the Alberta government in 2023 when Choi was awarded an Alberta Newcomer Recognition Award in the category of career and academics contributions.

THANK YOU

Generosity shines on Giving Day

MRU’s Giving Day was a rousing success on Nov. 28, 2023. The annual fundraising event brought together donors, students, alumni and the community at large, who gave in support of students and impactful projects at MRU. Altogether, $322,934 was raised, surpassing the initial fundraising goal by more than 61 per cent. This incredible result was made possible by the support of all who helped spread the word with their networks and generously contributed to Giving Day.

At the forefront of studying a new breed of vigilantes emerging from cyberspace is Dr. Leanna Ireland, PhD, assistant professor of criminal justice in the Department of Economics, Justice and Policy Studies at Mount Royal. With a keen interest in vigilantism in the online world, Ireland is shedding light on new forms of activism, social movements and justice-seeking behaviour as some take the law into their own hands online.

“Undoubtedly, acts of cyber-vigilantism are becoming more commonplace with the proliferation of digital tools,” Ireland says. “More people — regardless of their technical skills — can now engage in cyber-vigilantism efforts.”

Ireland says the practice of cyber-vigilantism is becoming more normalized because of the accessibility and widespread nature of social media. Her work highlights the complexities of this new form of justice, and she emphasizes the need for a nuanced understanding of this phenomenon.

$322,934

The seeds of change nurtured by MRU’s EDI Opportunity Fund are growing, as a wide range of equity, diversity and inclusion initiatives bloom from concept to reality. Since its inception in October 2022, the fund has provided financial support to 13 projects carried out by students, faculty members and staff, with more projects on the horizon. The fund operates under the stewardship of the Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. It serves as a springboard for various EDI projects including program improvements, accessibility initiatives, EDI learning, educational workshops, guest speakers and student-led research projects.

“A common thread through many of the initiatives is that they created learning opportunities,” said Dr. Tim Rahilly, PhD, MRU’s president and vice-chancellor. “When there is a chance to gain new knowledge, it is the ultimate investment.” More exciting developments are in the works as the Office of the President has made an additional $25,000 contribution, raising the total fund to $75,000 for 2023/24. This increase will support more diverse projects and the maximum allotment per project will be adjusted to $10,000 to accommodate a wider range of initiatives.

Dr. Moussa Magassa, PhD, associate vicepresident, equity, diversity and inclusion, emphasizes how strategic investments can drive significant change in addressing systemic barriers. “This fund is more than a financial resource — it’s a catalyst for change,” Magassa said. “It reflects Mount Royal’s commitment to fostering a campus environment where diversity thrives, every voice is heard and equity forms the foundation of our community.”

Roughly 200 Roman-era skeletons have travelled more than 8,000 kilometres from Austria to MRU where they will be used for research, teaching and to be preserved and digitized.

“The remains come from Carnuntum, which was a capital city on the edges of the Roman Empire,” said Dr. Rebecca Gilmour, PhD, an assistant professor of anthropology. “They are from the first- to fourth-centuries AD, so we’re looking at 1,500-plus years old.” Gilmour secured the collection on a long-term loan in collaboration with the Office of the Lower Austrian Provincial Government Department of Art and Culture and Archäologischer Dienst GesmbH, the excavating archaeological firm. Permissions were also granted by the Austrian Federal Monuments Office.

Given their age, many skeletons are not completely preserved, but they will offer an opportunity to know the people who lived on the Roman frontier, including their health, activities and experiences. Gilmour is in the process of delicately categorizing and taking inventory of each set of remains. Students will take part in the research, assisting with documenting preservation on skeletal charts and, where possible, estimating age and sex. “The ability to work directly with ancient skeletons is a rare and invaluable experience offered to few undergraduate-level students,” said department chair Dr. Mary-Lee Mulholland, PhD.

“This collection will be the foundation of many high-impact pedagogical practices including primary data collection and analysis, applied anthropology and independent research.”

It will be used in the classroom as well. Gilmour has selected more than a dozen volunteers and hired a trio of research assistants to work with her.

Alumni protecting lawmakers as sergeants-at-arms

Recognizing the Mount Royal community

Compiled by Erin GuiltenaneThe pathways for graduates of MRU’s criminal justice program are many and varied, so it’s notable that program alumni Tim McGough and Lyall Frederiksen, who both graduated in 1989, are now working as sergeantsat-arms in the Ontario and Saskatchewan legislatures, respectively. McGough first joined the Medicine Hat Police Service, where his career path included supervisory roles in the Firearms Training Unit as well as the tactical team and incident command. Retiring in 2022 as an inspector, in June 2023 McGough started working as the sergeant-atarms and executive director of precinct properties for the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Frederiksen joined the RCMP and was transferred to Saskatchewan where he spent 28 years, with the last eight working at the Saskatchewan headquarters. He retired at the rank of staff sergeant and joined the Saskatchewan Legislature security unit, becoming its sergeant-atarms in February 2023.

Athletic Therapy alumni win Business of the Year and Innovation awards

Athletic therapy alumni and entrepreneurs Carly Kolesnik , Advanced Athletic Therapy Certificate, 2018, and Ally Lo, Bachelor of Health and Physical Education, 2018, and their partner Brodie Lefaivre, recently won the Business of the Year and Innovation awards at the 2023 Airdrie Business Awards. Organized by Airdrie Economic Development and the Airdrie Chamber of Commerce, the awards recognize, celebrate and support business success in Airdrie. Along with Lefaivre, Lo and Kolesnik are Revival Therapeutics and Performance’s co-owners. The team strives to increase education and awareness around chronic pain and empower Airdronians to take active steps in their health.

Ecotourism student strikes gold on ski cross World Cup circuit

Jared Schmidt captured first place in Val Thorens, France; Arosa, Switzerland; and Innichen, Italy, racing on the ski cross World Cup circuit in December 2023. Schmidt started skiing at age two, began competing internationally in 2017 and represented Canada at the 2022 Olympic Winter Games, finishing 10th. A student in MRU’s ecotourism and outdoor leadership major, Schmidt says the program was a huge factor in his decision to attend MRU, as he was looking to enrol in a program in the outdoor sector while being able to train at a high level.

Alum working to expand Indigenous backcountry food company

Erin Creegan-Dougherty, Bachelor of Business Administration — International Business, 2023, has taken her business, Maskwa Backcountry Foods, to the next level. The business, which started as a seasonal, à-la-carte venture providing specialty meals to backcountry outfitters and other private clients, is now a full-fledged company offering Indigenous-inspired, gourmet backcountry food with products that accommodate a wide variety of dietary concerns. She debuted at MRU’s Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship’s (IIE) 2022 LaunchPad Pitch Competition and took home $10,000 from JMH & Co. She then finished fourth at the Global Student Entrepreneur Award national competition in 2023, earning a trip to the North American finals in Kitchener, ON. She is currently working as an entrepreneur development officer at the IIE and is a student in the University of Calgary’s accelerated MBA program.

Life is busy, we get it, and sometimes it’s hard to volunteer your time and give back even though you want to. Traditional volunteering isn’t always flexible and often requires a long-term commitment that doesn’t fit in busy schedules.

There are now ways to volunteer at Mount Royal through small, bite-sized micro-volunteering opportunities. Think of micro-volunteering as a chance to make a difference in a minute and be done in a few hours.

Small, meaningful interactions can have a significant impact. Volunteering your time isn’t just about giving back ... it’s about supporting current students, shaping the University’s future, telling heartfelt stories, amplifying the wins within our community and connecting with fellow alumni.

Micro-volunteering is for the changemakers, knowledge-sharers, content creators and most importantly, it’s for you. Are you ready to share your expertise? Inspire curious minds? Make an impact? There’s a micro-volunteering opportunity for every skill set and career level.

Get involved, express your interest in micro-volunteering.

mru.ca/MicroVolunteer

‘More

First recipient of the Doug Dirks Journalism Award announced

Words by Betty RiceImagine being a father of five, a full-time student and working to build a better life through a new career, all at the same time as providing financial support and reserving energy and attention for a busy family.

That’s where Ryan McMillan found himself last year. The journalism student (minoring in marketing) knows that finding the balance between being a student, parent and business owner is challenging, simply in terms of finding enough hours in the day to excel at all three. He is the first to say he wouldn’t have it any other way, but often thought that it would sure be nice to have some help.

This is where Doug Dirks comes in. The recently retired Calgary broadcaster and MRU graduate (Sports Administration Diploma, 1983) recognized both the challenges to the industry to which he’d dedicated his career and to those who hope to follow in his footsteps. In late 2022, Dirks made a $50,000 gift to MRU, establishing the Doug Dirks Journalism Award, which provides $2,000 a year to a selected student.

And McMillan was the first recipient.

“It is more than just a cheque,” he says. “The scholarship has a secondary feature to it, which let me know that I was doing good work and that all of this is worth it.

“Thank you, Doug Dirks!”

Ryan McMillan journalism award recipient

“The scholarship has a secondary feature to it, which let me know that I was doing good work and that all of this is worth it.”

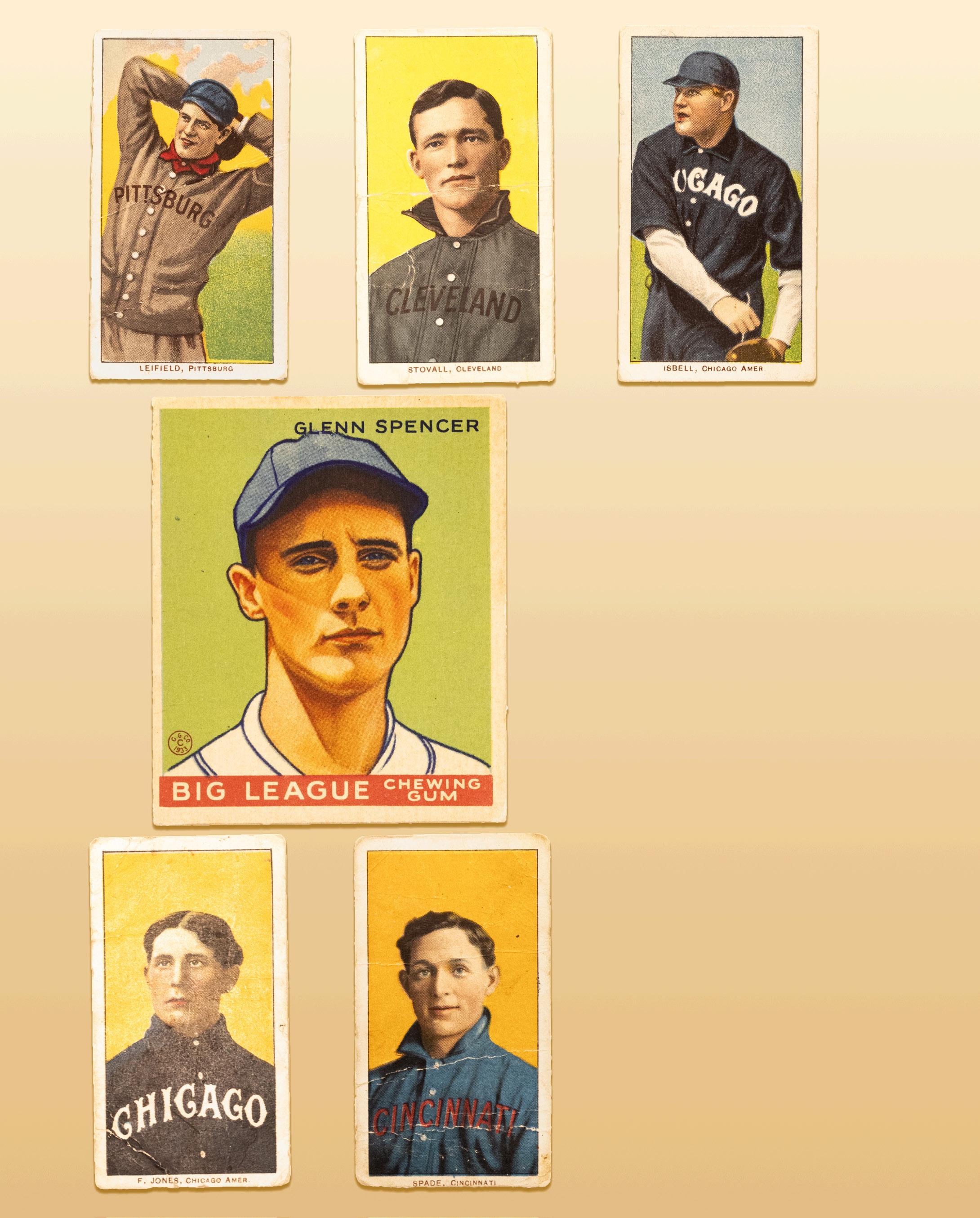

Examples of baseball cards from 1909 through the 1940s, now held by the Mount Royal University Archives and Special Collections.

The Piedmont Tobacco Company started issuing white-bordered baseball cards, known as T206s, in 1909. Piedmont cards are popular among collectors and are notable for their small size and rarity, as well as the high quality and bright colours of their lithograph illustrations. Another popular collectors’ series of cards, the 1934 Big League Chewing Gum series, boasts a similar colourful design with the addition of player information printed on the reverse of the card. Finally, the black and white cards issued by Gum Inc. in the 1940s have a more modern format by featuring realistic photographs of players and detailed biographical information on the reverse.

These baseball cards are part of the Blaine Canadian Sports History collection, which consists of a wide variety of publications, ephemera and promotional objects relating to the history of Canadian rodeo, baseball, football, golf and hockey.

What are the roadblocks to get to a world filled with EVs?

Israel Dunmade, PhD

Professor, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences

Israel Dunmade, PhD

Professor, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences

A number of factors need to come into play in order for electric vehicles (EVs) to have a major environmental impact: the source of electricity used for charging EV batteries; tonnage (i.e. weight) of the EV; effectiveness and efficiency in charging the batteries; longevity/lifespan of the battery and the reusability/ recyclability of the battery.

A lifecycle analysis of the EV ecosystem would be needed to accurately determine the environmental impacts, as impacts will vary based on these factors. If a renewable energy source is used for charging and the charging retention efficiency is higher than 95 per cent, I conservatively put the reduction in environmental impacts at more than 50 per cent. If the electricity source is fossil-fuel based, coal or natural gas, for example, the EV benefit may be very minimal. It is important to keep in mind that environmental impact goes beyond greenhouse gas emissions.

James Stauch

Executive Director, Institute for Community Prosperity

James Stauch

Executive Director, Institute for Community Prosperity

Despite slower consumer uptake in Canada than anticipated, even with public incentives (except for Alberta, which has slapped a levy on EVs), EVs are definitely here to stay. While it’s true in some jurisdictions, including Alberta, that a switch to EVs is a switch from gas-powered to coal-powered energy, the efficiency of EVs is so vastly superior to internal combustion engines that there’s still an argument to make the switch even in cold climate, coal-dependent places. And battery technology has made great strides in the past couple of years.

But, it’s complex: EVs, while necessary to transition away from fossil fuels, will definitely not save the climate and will, at best, slow the pace of climate change. Moreover, EVs produced at the scale of all automobiles today would require an increase in mining minerals that frankly has horrific implications for the environment. Additionally, EVs are much heavier than comparable gas-powered vehicles, and thus more dangerous in collisions, for pedestrians and cyclists especially. The quietness of EV motors, welcome in so many ways, may be a hazard for people with visual or auditory impairment. A scaled-up EV network will also require trillions of dollars in new investment in North America alone, though there is interesting potential for distributed and decentralized energy storage.

Katherine Boggs, PhD Professor, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences

Katherine Boggs, PhD Professor, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences

I am cautiously optimistic that it is possible to transition the Canadian energy grid to renewable energy sources towards the end of the 2030s, but there are issues facing EVs, in particular the need for critical minerals.

With today’s technology, each EV requires 65 kilograms of copper and 10 kilograms of cobalt. Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects that by the late 2030s there will be over 280 million EVs. Within a decade, this will require more copper than has ever been produced. Cobalt is a major bottleneck because those 280 million EVs will require approximately 2.8 million tonnes, while the current global annual production is approximately 100,000 tonnes.

More than 70 per cent of the global supply of cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo that has nearly no environmental or occupational health and safety regulations. So, why am I cautiously optimistic? First, there is significant engineering and technological focus on improving EV batteries, developing new batteries that don’t require cobalt, and reducing the amount of copper and cobalt required in EVs. Second, mineral exploration across North and South America, and Australia is now focusing on critical minerals such as copper and cobalt. Canada is now the fifth-largest producer of cobalt with mines in Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Manitoba.

Professor, Department of Economics, Justice and Policy Studies

While market forces are already at play with the rise of EVs, it is clear that the government’s role will be significant in the expansion, or not, of EVs.

Governments have a series of tools at their disposal. First, they can provide subsidies to consumers to purchase EVs. Second, they can provide subsidies to producers to build more EVs. Third, they can use legislation to mandate that a certain percentage of all new vehicles sold must be EVs. Fourth, they can take legislative or financial steps to ensure that there are enough charging stations across the country.

However, if a government (like Alberta) is either skeptical or even hostile to EVs, there are policy tools that it can use. The easiest is to do nothing. A government could claim that if consumers and producers really believe that EVs are the future, then the government does not need to try and incentivize their use. Or, a government could take direct action by imposing specific taxes on EVs to prevent their mainstream adoption and put charging stations under more rigorous regulations.

Research shows improving the gender gap in parenting has long-term societal benefits

Words by Peter Glenn

Anupam Das, PhD

Anyone with children can likely relate to the wish for some alone time, but who feels that they need more, mom or dad?

Tom Buchanan, PhD

A recent study from a trio of researchers including two MRU professors found that higher levels of responsibility faced by mothers of young children led to a greater desire to spend time alone as compared to fathers.

“Historically, mothers have been doing the lion’s share of household work, including child care. Since the 1960s, with changes in child-care policies, more fathers started to take parental leave and contribute to the caring for children. Nevertheless, there is still a significant gap in child care among Canadian parents,” says Dr. Tom Buchanan, PhD, a professor of sociology at MRU, who undertook a study into the topic with Dr. Anupam Das, PhD, an MRU economist, along with Dr. Adian McFarlane, PhD,

held at MRU. This soon led to collaborating on interdisciplinary research combining elements of sociology and economics.

Since then, they have examined the gender gap in child care among educated and working parents. They also studied how the gender gap in parenting time is related to the Canadian gender income gap, gender differences in perception of worklife balance and the gender gap in hours spent working in the labour market.

For the recent study, the researchers used Statistics Canada’s Time Use Survey data to analyze gender differences in desired alone time and how these differences are impacted by the gender gap in parenting time for Canadian

“A deficiency of alone time among parents, particularly mothers, can impact their well-being, labour market productivity and, by extension, economic prosperity in the long run.”

parents. The dataset used in the study contains 1,120 observations. Using cross-sectional analysis, they found that more than half of mothers with young children report desiring more alone time compared to about one-third of fathers. They also found that mothers’ desire for more alone time went up as their parenting and household labour time increased.

Alone time is not selfish, but a resource

Health is an important determinant of longterm economic growth. The researchers point out that psychology literature has found less alone time is associated with agitation, chronic stress, fatigue and, in general, harmful impacts on mental health.

“A deficiency of alone time among parents, particularly mothers, can impact their wellbeing, labour market productivity and, by extension, economic prosperity in the long run,” Das says.

The division of household labour practised by parents profoundly impacts children’s work and family expectations. This is important as children age, enter relationships, start families and contribute to the economy as workers.

“We believe that society has a critical role to play in expecting the equitable contributions of fathers, who must take initiatives in parenting time that fully allow mothers to experience alone time in ways that build personal resources. This includes freedom from parenting including the co-ordination of parenting-related tasks,” Buchanan says.

“This must happen at the level of intentional conversations in the household. If fathers

— Anupam Das, PhD professor of economics

contributed equally to parenting, household and cognitive labour, it would likely reduce mothers’ desire to be alone.”

In terms of public policy, the researchers argue that “it is not enough for parental leave to be available to employees. Employers need to mandate or at least set an organizational expectation that fathers will take leave.” They cite research from MRU human resources professor Dr. Rachael Pettigrew, PhD, which shows many fathers do not always take advantage of parental leave even when available.

With the gender gap in parenting time not likely to go away any time soon, Buchanan and Das say they will continue to explore this topic as new national-level data becomes available.

“We are always looking for ways to explain how inequities in families impact different aspects of life,” Das says. “We would like to explore how different configurations of families and parenting arrangements may offer new insights in this area. More generally, one continual contribution of our research is to shed light on the persistent inequities mothers face.”

Nick Strzalkowski, PhD

Nick Strzalkowski, PhD

Fromastronauts to pillownauts, an MRU biologist is studying skin sensitivity changes in participants spending 60 days in headdown bed rest to better understand sensory adaptations that occur during space flight.

Dr. Nick Strzalkowski, PhD, is part of a team studying countermeasures that could help astronauts deal with these issues in future space missions while providing valuable learnings for humans on Earth.

Strzalkowski is cross-appointed in the departments of biology and general education, and teaches courses on numeracy and scientific literacy, as well as human physiology. His scientific interests cover all aspects of human health, but specifically the neural pathways and networks involved in the control of movement in healthy and diseased populations.

At University of Guelph, Strzalkowski obtained a PhD under the supervision of Dr.

Leah Bent, PhD, who studies neurophysiology and is the primary investigator in this latest project funded by the Canadian Space Agency.

Part of that graduate research involved a 2009 project called Hypersole. For that project Strzalowski and Bent looked at the sensitivity of the skin on astronauts’ feet before and after a short space flight to the International Space Station.

Skin receptors in the sole of the foot play a critical role in the control of balance and posture, and tactile skin feedback provides humans with information about the direction of gravity and body orientation and verticality. The subjects of the original Hypersole study were 11 crew from the last four space shuttle missions before the program was cancelled in 2011.

“That’s how I got started in space research. We worked with astronauts, I

got to travel all over the States, and it led to two publications,” Strzalkowski says.

In particular, the study identified a subgroup of astronauts who demonstrated increased sensitivity of skin receptors that was shown to correspond to balance impairments following space flight, during trials specifically designed to target vestibular system (inner ear) deficits.

The current research, Hypersole2 , will be conducted in collaboration with NASA and DLR (German space agency), and is one of many concurrent projects run at :envihab in Cologne, Germany. The experiment Strzalkowski is contributing to involves 60 days of head-down bed rest — an established space flight analog. Participants remain in a bed with their head tilted below their feet by six degrees, simulating the physiological onloading and fluid shifts experienced by astronauts in microgravity. Participants will have nursing and physiotherapy care, but will otherwise stay lying down for the duration of the study. With access to computers and screens, many participants in similar studies take courses, play games and watch movies to fill the time.

“For our study they will be lying on their stomach,“ Strzalkowski says. “Sixty days is enough to see the effects on the muscle and bone that you probably wouldn’t see over a week.”

Participants are divided into four groups: control, proprioceptive training (involving body awareness), electrical muscle stimulation and exercise. The goal is to see if these countermeasures have an impact on skin sensitivity and if that may lessen the impact of long voyages in space.

“When you go up in space, you’re floating, and one thing that happens is your

vestibular system, which normally tells us about gravity, gets disrupted. Your brain kind of freaks out, you get really nauseous for a few days, but then over time we think there’s a re-weighting of sensory feedback to compensate and one of those things could be more sensitive skin because our skin also tells us about gravity here on Earth when we’re standing,” Strzalkowski explains.

“For me, being part of something this enormous is really interesting. A lot of the work we do is often just ourselves in the lab. This project involves dozens of labs and even our team has three faculty researchers involved and we’re one tiny piece of this.”

The work will also involve MRU undergraduate students in data analysis, an important component of research and the undergraduate experience at MRU.

“Nick’s work in this area emphasizes the wide range of research that is happening at MRU. As we increase our research capabilities, the sky isn’t even the limit for faculty and for our students,” says Dr. Jonathan Withey, DPhil, dean of science and technology at MRU.

While the immediate goal is to find ways to help astronauts, the research findings have potential spinoffs for human health here on Earth.

“There are people who are bedridden so it will help with that, but it’s bigger than that,” Strzalkowski stresses. “It involves a lot of basic science questions about human physiology. Learning about these intervention and mitigation strategies might turn into spinoff therapies for different patients or population groups. It’s pretty amazing how much space research makes its way back to the public.”

“It’s pretty amazing how much space research makes its way back to the public.”

—Nick Strzalkowski,

PhD associate professor, Departments of Biology and General Education

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

The term “cowboy” in this piece refers to ranchers, herders and horse riders of all genders.

Theiconography that many North Americans typically associate with the “cowboy” has largely been built through Hollywood and television productions, old and new. From classic heroes like John Wayne to the Dutton family patriarch on Paramount’s Yellowstone (played by 2022 Calgary Stampede Parade Marshal Kevin Costner), the cowboy’s familiar hat, boots and maverick attitude are a storytelling mainstay.

The real history of the “cowboy,” however, is much more diverse and widespread than what classic films and television shows portray. Traditions, events and cultural practices based around horses find their beginnings far from North America, thousands of years in the past.

Dr. Carolyn Willekes, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of General Education at MRU. An equestrian herself, her research and lecture topics include the history of the horse.

“If we define a cowboy as someone who rides horses and herds animals, we can use archeological and visual records to trace the symbols and tools we use to identify someone as a ‘cowboy’ back to the domestication of the horse, which was around 5,000 years ago on the steppes of central Asia in the area that’s now Kazakhstan,” she explains.

Nomadic groups began the taming process for horses as a food and milk source and the domestication of the horse was a turning point in how people managed their lives, economies and livelihoods.

“At the most basic level, that’s the birth of the cowboy — these nomadic groups in Central Asia who are migrating across the steppe and using horses to manage their animal resources,” Willekes says.

The original home of recognizable rodeo-type events is ancient Greece. The Thessaly region, famous for its horses and cattle, combined the two into a “rodeo”-type sport to result in horsebackbull-wrestling. Likely part of a festival honouring the god Poseidon, depictions of the sport can be found on coins dating from about 450 to 320 BC.

The culture then made its way across Europe, with evidence of “cowboys” in what is now Tuscany in Italy.

Traditions of ranching, riding and cattle management emerged with “cowboys” called the Butteri. To this day, the Butteri raise impressive, long-horned Italian cattle. “They have their own versions of rodeos that are more medieval or martialcombat in style, but the whole idea is a festival that celebrates their way of life.”

Following contact and settlement by the Spanish, cattle and horse husbandry traditions from southern Spain migrated to the Americas. The pampas of Argentina and the sprawling grasslands of Mexico were ideal for large groups of cattle.

“The people indigenous to the land were trained to become riders, basically to become cowboys, or vaquero, and that’s where we see the idea of rodeo develop,”

Willekes says. “They have a rich rodeo tradition (Charrería) in Mexico, and that moves from Mexico up into Texas.”

Interestingly, about 3.5 million years ago North America boasted numerous representatives of the genus Equus, or ancient horses. They became extinct for reasons still being debated by scholars. It’s popularly believed that horses were re-introduced to the continent by Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés in 1519, however this is debated by some North American Indigenous cultures who report seeing horses before Europeans arrived.

Indigenous communities across the plains were quick to integrate horses into their ways of life. “Research is showing that the horse moved across North America far quicker than we’d previously thought,” Willekes says. “It seems to suggest that Indigenous communities embraced the horse and very quickly figured out how to ride, manage and use them to great success.”

The familiar image of the modern cowboy — usually a white man in boots with spurs wearing a wide-brimmed hat and large belt buckle and seated atop a horse — begins to take place during the colonization of the Americas.

However, Willekes notes that ranching traditions in the southern United States were far more diverse. “If we look back to the 1800s when ranches were emerging in Texas and western North America, at least a quarter of all cowboys were Black. But if you look at the history of the cowboy, it’s presented as white. So that’s very much been erased.”

Particularly during the American Civil War, many white ranchers relied on enslaved people to manage their cattle and horses while they were away fighting. By the time the war ended, Black workhands had gained considerable ranching skills and expertise and many were hired once the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863.

“The Lone Ranger — who in Hollywood renditions is always white — is probably based on a Black man named Bass Reeves (1838-1910), who was one of the first Black sheriffs and became famous for doing a lot of the things that we see the Lone Ranger doing,” Willekes says. “His story was fascinating to writers,

movie creators, comic book creators and others. They made a very deliberate decision to make the Lone Ranger white, when in reality the inspiration for the Lone Ranger was Black.”

Here in Alberta, John Ware — the famous Black Canadian cowboy — was an integral part of southern Alberta’s early ranching industry. An excellent horseman, he was among the first ranchers in Alberta, arriving in 1882 on a cattle drive from the United States and ranching until his death in 1905.

Prior to the First World War, it would not be a surprise to see women fully participating in ranching and rodeo in North America, herding, roping and helping with other various aspects of herd management, and riding broncos and competing against their male counterparts in rodeos.

“With the professionalization of rodeo and the creation of rodeo associations run exclusively by men, women were pushed out of the narrative,” Willekes explains. “Women had to create their own rodeo

associations, which are, of course, marginalized compared to the others.”

It wasn’t until 1948 when the Girls Rodeo Association (now the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association) was created that women were able to push for gender parity by successfully advocating for inclusion in the professional rodeo circuit and for better pay.

The history of the horse in the western world and the cowboy identity are multi-layered. The cowboy identity finds a solid home in many parts of Alberta, particularly during the Calgary Stampede, which has evolved over the years to incorporate all of those who are skilled and interested in horsemanship.

“Wherever horses show up — and it’s an introduced species to most parts of the world — people find this relationship with it and incorporate it into their own cultural traditions,” Willekes says. “It got to most parts of the world through conquest and colonialism, yet people realize that it’s useful and a significant status symbol, and build social structures and practices around it.”

Willekes’ wide-ranging expertise has led to her knowledge being tapped for a cinematic deep dive into ancient Greece. She can be seen in the Netflix docu-drama Alexander: The Making of a God, which is a six-part series featuring historical reenactments and expert academic insights. Willekes says while it is not a traditional academic venture it opens up the story of Alexander to more people, many of whom might not have had a prior interest in Greek or Mediterranean history.

Acupuncture dates back more than 3,000 years, but the ancient practice of inserting needles just below the skin – identified by the World Health Organization as the most widely used traditional medicine practice globally – remains something of an unknown.

“Chinese medicine is used to treat everything that a primary care doctor treats in the West,” says Dr. Sarah Twelvetree, a 1998 MRU grad who became the first person in Alberta to be both a certified athletic therapist and a Doctor of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

“If a headache is a branch on a tree, there’s an underlying root system causing the headaches,” says Twelvetree, who offers acupuncture at MRU’s Injury and Prevention Clinic. “Acupuncture treats the branch –because people want relief – but it also looks at root causes.”

Acupuncture is based on the theory that qi (chee, or energy) flows through pathways or meridians in the body. By inserting needles into points along the meridians, Chinese medicine practitioners believe balance can be restored. Treating musculoskeletal pain, menstrual cramps and headaches, acupuncture stimulates nerves, muscles and connective tissue, increasing blood flow, reducing pain and promoting the body’s ability to heal itself.

“What has surprised me is how quickly acupuncture can work. For some patients there’s immediate relief,” she says.

Take advantage of your alumni discount and painlessly book your next appointment with one of our professional practitioners using our online booking system.

The stories, surprises and pitfalls of consumer DNA products

Words by Christina Frangou, i2iart.com

Illustrations by Carl WiensTheresa Tayler spit into a tube, sealed it in a box and shipped the package off for analysis.

It was her mom’s idea to have the family’s DNA examined by 23andMe, one of the world’s largest direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies. Her parents had already sent their saliva off for analysis. So had some aunts and cousins. Even Tayler’s 90-year-old grandfather gave it a try.

Once their DNA was posted on the portal, everyone could log into the company’s website and watch their family tree grow as more relatives sent in samples.

Months later, her parents pointed out something they’d noticed. Her grandfather hadn’t popped up in Tayler’s father’s family tree. He was also missing from hers.

“I was like, ‘What?’ ” says Tayler, who graduated from MRU’s journalism program in 2005. She was stunned. She knew the tests weren’t 100 per cent accurate, but these results were either flat-out wrong or everything she knew about the paternal line of her family was incorrect. Based on the company’s analysis, her grandfather did not appear to be a blood relative of Tayler or her father.

Her grandparents had spent their whole adult lives together until her grandmother died in 2017. They’d married in their late teens in London, England, and emigrated from Britain in the 1950s with their six-year-old child, Tayler’s father, in tow.

Tayler knew the English side of her family well. After high school, she’d spent a gap year in London, hanging out with cousins and aunts. She had been close to her grandmother, a staunch atheist who read poetry and oozed kindness. Her grandfather was more aloof, mostly because he was working, golfing or skiing when Tayler was growing up. When she became an adult, that relationship changed. Recently, he’d been diagnosed with advanced stage cancer. Tayler visited him on trips to Vancouver, BC, where he now lived.

The results of the DNA analysis put into question who she and her family were.

Tayler knew these sorts of tests sometimes unexpectedly unveiled secrets — she’d half expected that from her mother’s side of the family. But not this. She didn’t know if the secret had ever been known to anybody besides her grandmother.

“People think that the hard part of the trauma is finding that out,” Tayler says. The hardest part is what comes next. “It’s only because of this [expletive] DNA test.”

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing will turn 20 years old next year and has been an enormous hit with consumers. By 2019, more than 26 million people had submitted their DNA for genetic testing by the four leading commercial companies, 23andMe, Ancestry, GeneByGene and MyHeritage, according to MIT Technology Review. In early 2024, 23andMe reported having more than 12 million customers, while Ancestry’s database contains information from 25 million people. These two leaders in the DTC genetic testing industry have now amassed the world’s largest non-governmental collections of human DNA information.

DTC genetic testing differs from the genetic testing performed by health systems. The latter usually answers questions about a person’s genetic risk for disease. It’s protected by legislation, setting out privacy guardrails for health information and is often delivered by a genetic counsellor.

DTC testing follows different rules. It doesn’t require a referral from a physician, and is advertised as technology to fulfill curiosities about a person’s ancestral lineage and potential health risks. Some companies even offer guidance about a person’s innate athletic abilities or ideal diet based on the DNA analysis.

The large databases owned by these companies also hold enormous promise in the treatment and understanding of disease and genetic risk. They contain huge troves of data about human beings that could help researchers identify new ways to prevent or treat disease.

But sometimes, the information stored in these databases leads to uncomfortable consequences — both for the people who’ve submitted their data and for their families. It can be more than they bargained for when they sent their saliva off in a tube.

Tayler, who spent a decade working as a journalist and in communications roles before starting her own company, was angry at the results. She wanted more answers and had no one to guide her through the next steps. She began questioning her extended family to help put together the human story to go along with her genetic results. “Did you know that Granddad isn’t my Dad’s birth dad?” she asked her cousins and aunts. To her shock, some responded they did, but they’d never wanted to say a word to her or her father. Her father’s younger brother said that he’d known for years; cousins told her that they thought she already knew. The story of her father’s parentage had somehow become the secret that many carried, but no one acknowledged. Looking back, Tayler says she and her father ignored clues. She remembered sitting in a pub while showing her elderly aunt the photo of her and her cousins; her aunt had laughed when Tayler said they looked alike. “She was like, ‘You think so, eh?’ ” Tayler recalls. Her grandparents had both been born in the east end of London in the 1920s, and they were in their teens when the Second World War broke out. Their neighbourhoods endured some of the worst of the Blitz. Her grandparents met after the war, started dating and married in 1949, in what Tayler always imagined was the euphoria of those postwar years.

Now, Tayler understood that her grandmother must have been going through agony when she realized that she was carrying a child out of wedlock. She didn’t know if her grandmother even knew with certainty who the father was. Tayler doesn’t feel anger toward her grandmother about that. “Can you imagine coming out of a war like that?” she asks. “It must have been like this: ‘We’re alive! We didn’t die in the Blitz.’ How can we judge that?”

She didn’t want to risk upsetting her grandfather, who was dying of cancer, but she also did not want to miss out on her last chance to ask him what he knew. She flew to Vancouver, posing the question that felt most appropriate: “How many kids do you have?”

She had to repeat the question when he didn’t answer at first.

“Two and half,” he eventually replied.

She feels protective of her grandparents who kept this hidden for 70 years. But she sometimes feels frustration towards her family who didn’t say anything.

After poking around in her grandmother’s history, looking for clues, Tayler has not uncovered an answer about who her blood grandfather is. She isn’t certain if she wants to reveal a secret that her grandmother had hidden until 21st century technology forced it into the open.

Tayler has learned that her grandmother had an American boyfriend when U.S. troops were stationed in London. She also had a relationship with a German prisoner of war, to whom she’d been writing after the war. Having read these letters, Tayler learned that her grandmother suddenly stopped corresponding with him, ignoring the man’s queries about what happened to her. Tayler has also considered that something terrible happened to her grandmother that resulted in an unwanted pregnancy.

For now, these are just theories, sparked by the result of a genetic test that she did for fun. 23andMe didn’t reveal any unexpected blood relations. Tayler suspects she might find some relatives on her biological grandfather’s side if she submits her DNA to other genetic testing sites. But she’s had enough genetic testing surprises for now.

“I’m glad we did it. It shed a lot of light on stuff that I didn’t even realize it was going to shed light on,” she says. She’s become comfortable with this new story: her grandfather, who wasn’t her father’s father by blood, stepped into the role of father and never wavered. The rest, for now, is her grandmother’s story to keep.

“That story lives with my grandmother. And I used to be angry about it. But I’m starting to realize, as much as it pisses me off that other people knew, it’s her story,” she says.

Forty-four years ago, when an international consortium of scientists set out to sequence the human genome, they were not thinking that their work might send shockwaves through families. The Human Genome Project, which kicked off in 1990 with a budget of $200 million a year, was ambitious. Its great promise was a future with important discoveries about the causes of disease and a map to treat or even prevent disease.

Thirteen years later, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium announced that it had generated a complete human genome. Two years after that, a new industry got its start: DTC genetic testing. Thanks to the work of the consortium, companies could now quickly and, relatively cheaply, scan the labyrinth of human DNA. This meant that people could spit in a tube and send their saliva or cheek swabs for testing, with the price tag of around US$1,000 in the early years. As the technology improved, the cost fell dramatically, to about $99 per test by 2012, and the market for genetic testing exploded. By 2019, there were over 250 companies offering DTC genetic tests.

But there are significant limitations to the results given by many of these companies, says Dr. Samanti Kulatilake, PhD, an associate professor of anthropology at Mount Royal.

Kulatilake is a biological anthropologist who specializes in the study of ancient human remains such as bones and teeth, in order to understand past lifeways, migrations and ancestry. In 2017, she spent a summer studying at Lakehead University’s Paleo-DNA Laboratory in Thunder Bay, ON. There,

she learned DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing and interpretation by practicing on herself. She used forensic techniques on her blood, cheek swabs and hair follicles to analyze her mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, looking for markers that are associated with people from different parts of the globe.

There is a difference between finding a marker for ancestral roots and the results provided by genetic testing companies, she says. DTC companies offer their consumers a detailed breakdown of their various ancestral ethnicities, the results of which include such information as “36 per cent Eastern European, 11 percent Italian” and so on — the kind of outcomes that often surprise people. They say things like: “I didn’t know I was Italian!” or “I always thought my roots were entirely German!”

But the science behind these reports is not exact, says Kulatilake. “This idea of assigning somebody with a percentage is very flawed.”

While the science for genome analysis is robust, there are major limitations in the way that companies interpret the results for consumers, she says.

“The start is scientific, but the outcome may not be so because of the way the data is presented to the consumer.”

For one, companies often break down ancestry into percentages based on biomarkers associated with people known to live in different geographic regions. But it is hard to narrow down those markers to an area as small as, say Italy. Particularly when a person’s ancestors were in that region generations ago. What’s more, companies’ interpretations are

“IT IS ENTERTAINMENT, BUT THERE’S A SLIPPERY SLOPE THERE THAT ONE MUST BE VERY CAUTIOUS ABOUT.”

— Samanti Kulatilake, PhD associate professor of anthropology

based on the information in their database, which often includes large samples of Europeans but under-represents people in the Global South. Finally, these tests cannot account for human migration over millennia, points out Kulatilake. People have been moving and interconnecting around the globe from long before the current borders of nation states were set out, she says.

“How can you do this assessment based on a species that is so mobile? We are one of the most mobile species ever,” she says.

The flaws in this system are regularly reflected in test results. In 2019, CBC’s Marketplace reported on identical twins who purchased home kits from five companies and mailed samples to each for analysis. The twins did not receive matching results from a single company. Other families have reported that ancestral roots may appear in one generation but disappear in the next.

Kulatilake tells people not to take the results too seriously. “It is entertainment, but there’s a slippery slope there that one must be very cautious about,” she says. “It’s also costly entertainment — costly for the people who are submitting and also costly for humanity.” There can be racist connotations when people seek to define themselves by modern-day nationalities, she says.

There’s one important fact always overlooked in genetic test information, she adds. Humans are 99.9 percent genetically similar. Our differences are in the 0.1 per cent. “This dissimilarity is very very tiny compared to the sum total of the shared genetic basis of human existence,” she says.

Privacy experts like Dr. Khosro Salmani, PhD, an assistant professor in MRU’s Department of Mathematics and Computing, have long warned that consumers who share personal information with genetic companies risk having sensitive information stolen.

In 2017, The Economist reported that data has replaced oil as the most valuable resource in the world. Personal data, especially, has enormous value. Many actors — from individual hackers to multinational corporations — want those details, whether it’s birth dates, names of family members or hints about items that someone is more likely to be interested in purchasing. Organizations use this information to identify markets for their products, while hackers make money illegally by selling, threatening to sell or hijacking personal data.

The kind of data collected by DTC genetic testing companies is particularly sensitive, says Salmani. “What we have to consider is that it’s not only going to impact me, but our family, and all of the generations right after that.”

Genetic testing companies have been hacked in the past. In 2020, hackers got into GEDmatch, a large genealogy site where users upload their DNA information to search for relatives. Days later, GEDmatch customers who’d also shared their data with MyHeritage, another genealogy site, were targeted again in a phishing attack.

That was only the beginning. In 2023, the industry was hit by the largest data hack in its history. Hackers accessed the personal information of about 6.9 million profiles at 23AndMe—almost half its customers— between April and September 2023, and posted a sample of the data online. The hack appears to have targeted customers with Chinese or Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, and their personal genetic information was then compiled into curated lists that were sold and shared on the dark web.

Since the breach, 23AndMe customers have launched class-action lawsuits in British Columbia and the United States. At this point, it is too early to know what the consequences may be for the people who were hacked, Salmani says. The data could be used to influence people’s premiums for health or life insurance.

Submitting your data for testing “is a big decision,” he warns. He urges people to do their homework before sending their DNA for any analysis with a DTC genetic testing company. They should always look carefully at a website before making an online account to confirm that it is legitimate, and review a company’s privacy policies, which every Canadian company is required to do by law. These policies outline how data is going to be used, what kind of security actions are being taken to ensure that users’ data are protected and the services these companies provide. Many have opt-in clauses regarding use of their data for research or by law enforcement. Users should only sign up for companies that verify new users through a multi-factor authentication system, Salmani says. The push from outsiders to get at your personal data is only going to increase, he adds. “Every day, we are becoming more and more susceptible to these types of attacks, and we should definitely do more in order to protect those kinds of things,” he says. “And when it goes to the genetic data, it becomes even more sensitive.”

Data from genetic testing companies is also being enlisted to solve crime — sometimes through controversial methods.

Police in Canada first used DNA in 1987 when they were looking for a man who’d sexually assaulted seven women in Edmonton. Within the decade, the Canadian government gave the go-head to police to take DNA samples from anyone convicted of a serious crime. That bill laid the foundation for the RCMP’s National DNA Data Bank, which contains two main collections of DNA today.

The first, the Convicted Offender Index, holds DNA from more than 450,000 people convicted of a serious crime in Canada. The second is the Crime Scene Index, a repository of more than 220,250 DNA samples recovered at crime scenes. A computer network called CODIS, for Combined DNA Index System, created and maintained by the FBI in the U.S. and shared with more than 90 law enforcement laboratories in over 50 countries, including Canada, links this information with police across the country.

DNA testing has improved since the database was first launched. Police can now retest old samples using modern methods and come up with DNA profiles for suspects in cases that have long gone cold. This has happened while genealogy databases owned by private companies were rapidly growing. Inside, these databases hold a treasure trove of information; they show family trees of people who’ve submitted their DNA for testing.

For investigators, these trees serve almost like road maps marking out the path from a DNA profile to the identity of a suspect. It’s given rise to a new specialty in law enforcement: investigative genetic genealogy. Its practitioners cross-refernce the DNA samples collected at crime scenes with genealogy databases to identify criminals.

Most famously, genetic genealogy solved the mystery of the Golden State Killer — a man who’d murdered at least 13 people and raped nearly 50 in California in the 1970s and 80s, and was arrested in 2018 based on DNA samples taken from a crime scene 38 years prior. The case kicked off a new era in DNAbased investigations, and since then, genetic genealogy has led to many cold-case arrests in the United States.

Genetic genealogy is used less often in Canada. Canadians do not submit their data as frequently to genealogy websites, rendering the databases less effective here. Still, genetic genealogy has produced high-profile results in Canada. In 2020, Toronto police announced they’d identified the killer of nineyear-old Christine Jessop, who was abducted, raped and killed in 1984. Guy Paul Morin, the family’s neighbour, was wrongly convicted of her murder in 1992, and was cleared in 1995 after DNA typing definitively excluded him.

In Calgary, genetic genealogy recently helped bring charges to a longstanding cold case. For nearly half a century, police did not have a suspect in the 1976 murder of 16-year-old Pauline Brazeau, a single mother whose body was found on a rural road outside Cochrane.

In 2021, the RCMP submitted forensic evidence from the crime scene to Othram, a Texas-based company that does advanced DNA sequencing for law enforcement. Othram gave the RCMP a comprehensive DNA profile for the suspect. From there, the RCMP turned to specialists at Convergence Investigative Genetic Genealogy, an American company that compares DNA profiles against databases where users send their DNA profiles. That led to a suspect. In November 2023, the Calgary Police announced that they’d arrested 73-year-old Ronald James Edwards of Sundre on charges of Brazeau’s murder. His trial is scheduled for March 2025.

DNA technology is changing so rapidly that the laws in Canada have fallen out of date, says Doug King, a professor of criminal justice at MRU. Here, police are not permitted to use familial DNA to identify a suspect using the national DNA databank. If evidence is collected from a crime scene, it cannot be tied to a relative who is in the Convicted Offender Index and then used to pinpoint their relation. (By comparison, most U.S. states allow this.)

But police have turned to non-government genetic databases to identify suspects. Some, but not all, databases ask users to give their consent for law enforcement. In the 2020 hack of GEDmatch, hackers changed the settings of people who’d submitted their DNA and opened everyone up to law enforcement analysis.

King says that a key principle in Canada is that people are owed a reasonable expectation of privacy against the government. He is concerned that people may have their DNA examined in a police search without their permission.

“There’s an old adage related to search and seizure: an unreasonable search cannot be justified by what you find,” he says. “And that’s not just a quaint saying. It is the foundation of section eight of the Charter. We’re toying with some really core principles related to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.”

A Senate committee is currently considering a bill that would change Canadian laws around collection of DNA evidence, aligning them more closely with the United States. If passed, Bill S-231 will mean that anyone convicted of a crime punishable by five years or more of jail time, not just those convicted of a serious crime, will have their DNA collected — a change that would expand the National DNA Data Bank and would have helped identify the killer of Christine Jessop years ago when her murderer was convicted of drunk driving. The bill would also allow police to use DNA samples to identify potential family members of suspects.

King hopes Canada does not follow the U.S. example, saying the Charter is designed to protect from government overreach. As it stands now though, “technologies are outstripping the law,” he says.

Genetic testing companies sell customers on an idea that they will learn about themselves at a deeper level. “Know your personal story, in a whole new way,” promises 23AndMe. “Get to know you” is AncestryDNA’s slogan. But the reality is that these tests are not just about personal discovery. Hackers may also get to know you. Your personal details might be widely shared. Family secrets can get pushed out into the open.

Yes, these tests tell a story about one person’s DNA, but there’s no telling how those stories end.

Exploring the art and science of ultra runningWords by Rachel von Hahn

The sun sets behind the mountains and shrinks my world to the small beam of a headlamp. My feet are a minefield of hotspots and blisters, the undersides of my arms are chafed and raw. Going up another hill makes my calves scream. Every muscle screams, actually. And although I know I need to eat, my stomach threatens to violently revolt. Is the pain I’m feeling harmful or dangerous? Nope, onwards!

I am 14 hours into an ultramarathon race traversing the trails of Kalamalka Lake Provincial Park in Vernon, BC, and only slightly questioning my life decisions. Sweaty, sore and covered in dirt, I find myself smiling. This is absurd, and exactly what I signed up for. Well, almost. I could have done without the record-high 30-degree weather in mid-September. Mother Nature sure has a sick sense of humour … She must be an ultra runner, too.

Put simply, an ultramarathon is any footrace longer than the standard 42.2-km marathon. Distance-based races are the most popular, often taking place on trails and mountainous terrain. Jumping between measurement units, common distances include 50 km, 50 mi. (80.5 km), 100 km and 100 mi. (161 km). There are also multi-stage events where different routes are completed over consecutive days, or ultras where runners go as far as possible within a set time period, such as 12, 24 and 48 hours (flat roads and running tracks are more conducive to this style).

And then you have the unique (no, masochistic) backyard ultra, a format with no set time or distance. Racers complete a 6.7-km loop, known as a yard, every hour on the hour (equal to 100 mi. per day), until only one runner is left standing. If a runner completes a yard in 50 minutes, they have 10 minutes to refuel, change gear and possibly power nap before starting again. Slow, steady and sleep-deprived wins the race.

There’s really nothing glamorous about running really, really far. It requires weeks, months and sometimes years of training and monotonous miles. After you’ve put in all that work, race day throws in its own myriad of challenges. Fatigue, muscle cramps, blisters, chafing, gastrointestinal distress, sleep deprivation, acute injuries, adverse weather … The only real guarantee is your mettle will be tested.

And still, registration numbers are booming.

In 2023, UltraRunning Magazine reported a 1,032 per cent increase in North American ultra participants since 2000, jumping to 86,333 runners from 8,362. In Alberta alone there were over 30 ultra events last year, from the fast and flat Calgary Marathon 50 km to the grueling Divide 200 miler along portions of the Great Divide Trail in the Rockies.

For a sport unapologetically steeped in discomfort, why are so many people eager to toe the starting line?

“I wanted to find what came first, the bottom of the well or the end of the rope. I wanted to find my limit.”

— dave proctorDave Proctor running through Newfoundland during his Trans-Canada record Photo by Vera Neverkevich Hill

Curiosity has always been constant in Dave Proctor’s ultra journey. Proctor is a registered massage therapist, author, speaker, Mount Royal alumnus and one of the most accomplished distance runners in the country. With an ultra career spanning 18 years, the thought, “Is this humanly possible?” has powered him from the lowest of lows to the highest of highs, from broken bones to broken records.

Reflecting on how it all began, Proctor says he once thought running 100 km and beyond couldn’t be possible. After watching runners complete the feat in real time, his skepticism was replaced with a desire to see where his own two feet could take him. “I wanted to find what came first, the bottom of the well or the end of the rope. I wanted to find my limit,” he says.

Sierra Hope, an MRU ecotourism and outdoor leadership program graduate was introduced to ultra running at a young age by her grandparents. While she was happy to volunteer at races and cheer on her grandpa, she wasn’t interested

in doing it herself. “I was always super against running. I was the kid who faked being sick to get out of running in gym class,” she laughs.

But the spirit of inquiry got the best of her after she moved to Canmore, AB, and made friends in the trail running community. “They opened my eyes to what was possible. I was surrounded by people who were pushing themselves and wanted to see what I was capable of,” she says, adding that trail running also became a way for her to explore more of the mountains in less time. Hope crushed her first 50-km ultra last fall.

There are almost two decades separating Proctor and Hope’s inaugural race experiences, but how they ended up at the

starting line isn’t so different. That intrinsic shift from “there’s no way” to “let’s see if I can do it” is a prevalent theme in the ultra community. Labelling something as impossible puts up a barrier and limits beliefs. Dismantle that barrier and suddenly there’s room to reframe your potential. Start chasing that potential — now you’re in a place where the magic happens.

“There’s nothing quite like seeing people cross the finish line,” Proctor says. “They dug way deeper than society-atlarge convinced them was reasonable to do and they earned it. And then they think, ‘If I can do that, what else in my life could I accomplish?’ It’s a reminder of how innately strong we truly are.”

In Proctor’s perpetual search for his limit, he has set numerous course records, the Canadian 24-, 48- and 72-hour distance records, and a couple of Guinness World Records for good measure. In hindsight, these were all just a warm-up for what he describes as his personal Everest: breaking the trans-Canada speed record.

From the logistics and planning required to the sheer size of the country, everything about running across Canada is of behemoth proportions. Now just add in the small factor of doing it in record time. Always up for a challenge, Proctor made his first attempt in 2018. After 32 days of running from Victoria to Winnipeg, a ruptured disc in his back forced him to stop.

Four years later, he again laced up his shoes, donned his signature cowboy hat and set out for the record, this time starting in St. John’s, NL and running west. The coast-to-coast, 7,159-km odyssey threw every kind of hurdle his way: severe weather, catching Covid-19, a stress fracture, a concussion, close calls with distracted drivers and the overall mental and physical toll of running all day, every day.

“It’s a lot of time to locate exit doors on the highway, to catastrophize and make mountains out of molehills,” Proctor reflects. He was constantly faced with two options: quit running or embrace the discomfort and persist. And over and over again, step after step, he chose the latter.

After 67 days, 10 hours, 27 minutes, Proctor had officially run across Canada faster than anyone in history.

In his memoir, Untethered: The Comeback Story of One of the Longest Fastest Runs in History, Proctor writes about how we are genetically programmed to prioritize comfort over effort. “We typically accept some things as too difficult or too painful and give up, especially when survival is not on the line and we have plenty of food in the fridge.”

What happens if we mentally flip that switch? “We can endure many things.”

To Proctor’s point, ultramarathons provide a privileged space where runners can step into discomfort and see how it feels to stay there awhile. It’s a voluntary suffering that challenges one to adapt, endure and persevere in the face of adversity.

“We often look for excuses to pull the plug well in advance of where we should, but it’s okay to be uncomfortable and go, ‘I’m okay,’ Your body will produce when the mind lets it,” he says.

» 67 days, 10 hours, 27 minutes

» 7,159 km (averaging 105.2 km per day)

» 47,584 m total elevation gain (equal to summiting Everest five times)

» 12 pairs of running shoes

» 7,000 to 9,000 calories per day