INTRODUCTION

WRIT TEN BY CATHRYN CLANCY PHOTOGRAPHY BY ALISHA POWER DESIGN BY GEORGE CHEN, GRAHAM HUMPHREYS, SUT TON SHELMIRE , EKPELE ANWAH

WRIT TEN BY CATHRYN CLANCY PHOTOGRAPHY BY ALISHA POWER DESIGN BY GEORGE CHEN, GRAHAM HUMPHREYS, SUT TON SHELMIRE , EKPELE ANWAH

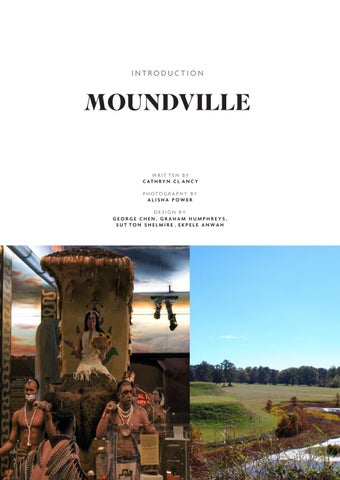

Just 30 minutes from campus lies a beautiful park nestled off not far wfrom the main road. Many use the park as a walking trail along the Black Warrior River, through dense forests, and around strange mounds. However, over 1000 years ago, more than a thousand people used to occupy this 300-acre area, with a population in the tens of thousands oc cupying the surrounding area. Moundville at one point was the second largest settlement in North America, and a complex religious and political center for the Mississippian Native Americans. The strange mounds were man made over a 400-year period, used for ritual and residential purposes. “Lost” for close to half a cen tury, its rediscovery opened the doors for archaeologi cal discovery for years to come.

Currently, Moundville is a protected archaeologi cal site, with both a museum and an archaeology lab

on location. It is a part of the University of Alabama Museum System, and students have the opportunity to visit for a discounted price. Moundville is also the site of continued archaeological excavations, performed by professors at the University along with students. How ever, Moundville has become a point of contention in recent years.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatria tion act was passed in 1990, and dictates that remains and funerary objects that can be traced to current tribes be returned. The University of Alabama housed over 5,000 sets of remains in a lab on campus, which Muskogean tribes fought to have returned. The fight over ownership of the remains went on for years, with a decision being reached only recently.

In this series, Moundville will be explored as a Native American cultural center, an archaeological site, and a place for students to learn and expand their horizons.

From the spot of this elevated mound, nobles could watch ancient ceremonies or stickball, a southeastern Native American game still played today.

Cheering on the Crimson Tide and enjoying the nightlife of The Strip are often the only things that one thinks of when mentioning Tuscaloosa, Alabama. However, 700 years ago, the area would have been the second largest settlement in North America. Mound ville became occupied around the 11th century and within about 100 years, had constructed incredible feats of architecture in the form of mounds. For centu ries, Moundville was a cultural and religious center for Native Americans of the Mississippian culture. At one point, it is estimated that as many as 13,000 people occupied the area, all with specialized roles within their community that kept the society functioning. By the 16th century, the site was all but abandoned, and the once booming settlement was remembered only by the mounds left behind.

Moundville was largely forgotten until the 1800s, when it is mentioned in a Smithsonian survey since it had become farmland. It was not until 1906 that excava tions began on the site conducted by Clarence Bloom field Moore. Moore was an independent archaeologist before the field had been truly defined, and eventually he donated most of his findings to the Smithsonian Institute. The state of Alabama did not like that these artifacts were being moved out of state, and eventually passed laws prohibiting this occurrence.

Formal excavations began in the 1920s when the University of Alabama bought the land. Excavations continue there under the supervision of the University of Alabama to this day. Until 1991, these excavations produced remains and artifacts that were housed in labs belonging to the University.

Today, many tribes consider Moundville to be a part of their history. They each descend from the Musk ogee culture, a language family that developed in the Archaic period in the area. Every year, representatives from the tribes return to Moundville for the Native American Festival to pay respects to their ancestors and share their cultures with visitors.

Moundville Archaeological Park is a part of the Univer sity of Alabama Museum System, which includes The Alabama Museum of Natural History, Gorgas House Museum, Mildred Westervelt Warner Transportation Museum, Paul W. Bryant Museum, and Moundville Archaeological Park. If you currently attend the Uni versity of Alabama, in the undergraduate or graduate schools, you are eligible for a free membership which grants unlimited admission to any of the museums that are a part of the system. Take advantage of the oppor tunity you are afforded as a student here and explore the rich history that Alabama has to offer.

In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)was passed in federal courts, which insures “the repatriation and disposition of certain Native American hu man remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony” according to NPS.gov. The act affects federal organizations and requires that they consult descendants concerning the recovery of remains and oth er objects and provide the proper dignity and respect to Native American sites. An important part of the story of NAGPRA and the University of Alabama is that remains and objects must be proven to belong to a certain culture. When the law was passed, the University claimed that the objects and remains in its possession were not able to be traced to any specific culture living today, otherwise known as culturally unidentifi able (CUI).

In response to this, a joint claim was made by seven tribes, which the committee that over sees NAGPRA affirmed on November 24, 2021. The University accepted this after major public backlash and began consulting with the tribes in January of 2022. At this time, all known funerary objects were removed from the museum at the park, and an inventory check was being per formed at the University, where it was found that over 10,000 ancestors were in the university’s possession.

The argument for the return of objects to their cultural associates is not limited to the United States in collaborating with Native Americans. London’s British Museum currently hosts what has come to be known as the Elgin Marbles. These are marble panels that were taken from the Acropolis in Athens in 1801. Recently, argu

ments have been made to return the marbles to Greece. However the British government contin ues to deny this request, because Lord Elgin had received permission from the Sultan occupying Greece at the time to take them. This is one of many instances of cultures asking for their im portant objects back from museums.

It is hard sometimes to understand why muse ums do not return these objects. However, there are also instances where the only chance for preservation is museums in foreign nations. In 2001, the Taliban announced that they planned to destroy the Bamiyan Buddhas, 175 ft sculp tures carved into the mountainside, as they were representations of a religion other than Islam. UNESCO fought to preserve and protect these objects, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art offered to buy the statues and protect them in another location. Efforts were refused by the Taliban, and the buddhas were filmed being destroyed by various explosives. In this case, a piece of art and history was lost.

An important difference between the cases of the Elgin Marbles, Bamiyan Buddhas, and ob jects connected to Native Americans must be noted. Many indigenous cultures consider even the oldest remains in the same regard as they would a known relative. History is regarded differently than the Western ideologies. The ongoing debate about the ethics of museums will likely wage on for decades to come, with laws being passed every year that change the landscape of archaeology and preservation. Most importantly, we should listen to representatives of cultures and attempt to understand history from their perspective and culture to accommo date them as much as possible.

From October 12th to October 15th, Moundville

Archaeological Park hosted the Native American Festival, where members from descendent tribes shared their culture with visitors from around the state. Demonstrators at the event performed dances, songs, and told stories from their cul tures, sharing myths from their religion along with the importance of the site to their respec tive cultures. Vendors sold various Native Ameri can arts and crafts, living history performers told stories of the site, expert craftsmen shared how to make and shoot projectiles, and the museum and other volunteers shared the archaeological discoveries that have been made on the site.

Thousands of visitors entered the park over the course of the week, each stepping away with a newfound appreciation for local Native cultures. The main visitors were school groups. Buses unloaded hundreds of excited students, eager to participate in the offered activities. The event was made accessible to people of all ages, with demonstrations tailored to younger and older visitors.

I had the opportunity to volunteer and de scribe to visitors the archaeological process at the festival through the Anthropology Club, It was amazing seeing so many young students so interested in the park. I also had the opportunity to learn a lot from participating in the event. Our booth was set up by the performance stage, and throughout the day we heard the beautiful songs and stories of the tribes. The performers fielded questions from audience members, ensuring that education and understanding was the main takeaway from the event.

The festival is held every year, and each year the site becomes alive. As I was standing at my booth, I realized that this festival was the clos est the site would get to its former glory. People participating in traditional events, eating, sharing stories, and growing closer with the community was the original purpose of Moundville as a cul

Festival Gathering

Festival Gathering