Voices and Visions

Art and

Writing

from the Middle School

Student Editors: Sankirtha Kapoor ’29 and Kaavya Sinha ’29

Faculty Advisor: Marsha Kleinman

Visual Art Teacher and Curator: Joelle Francht

Layout and Design: Diane Giangreco

8th Grade, Class of 2029

7th Grade, Class of 2030

6th Grade, Class of 2031

5th Grade, Class of 2032

4th Grade, Class of 2033

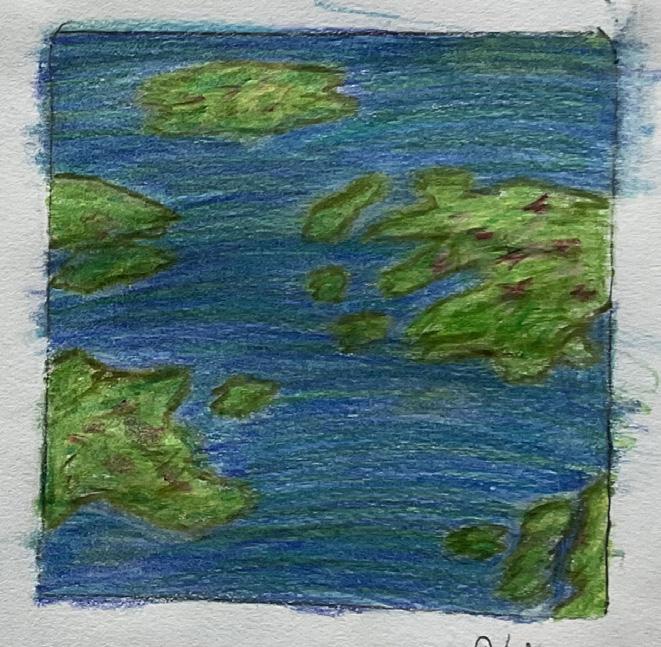

Cover Art: Luciana Murelli ’29

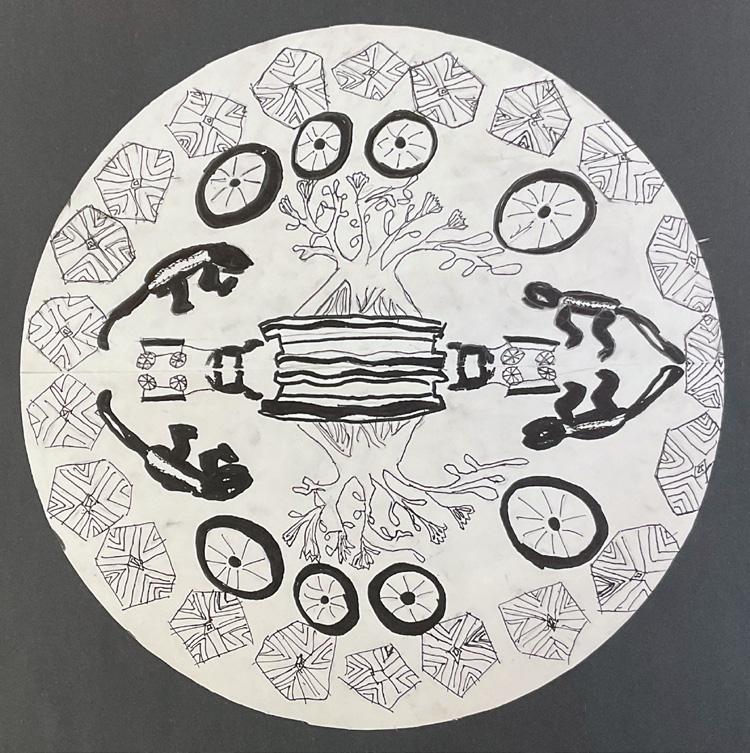

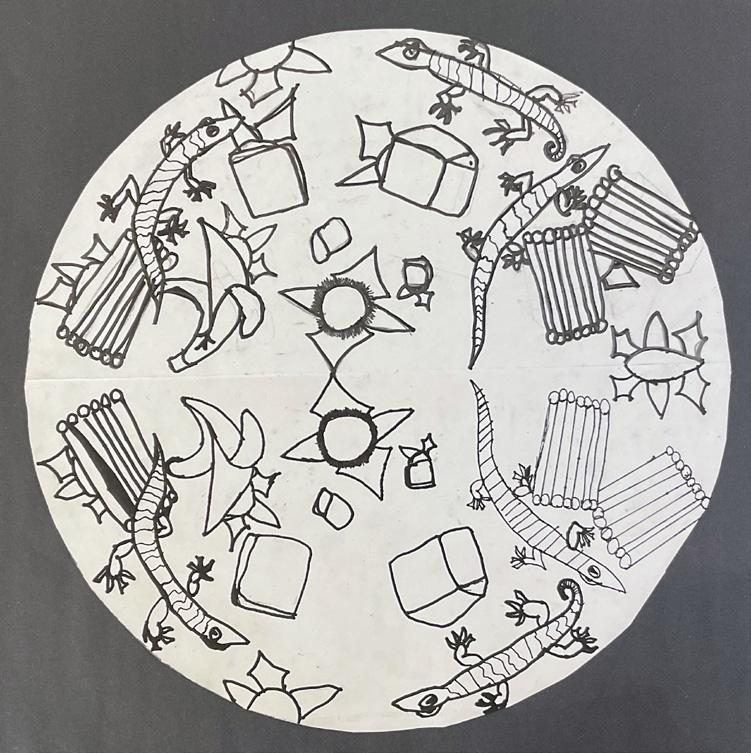

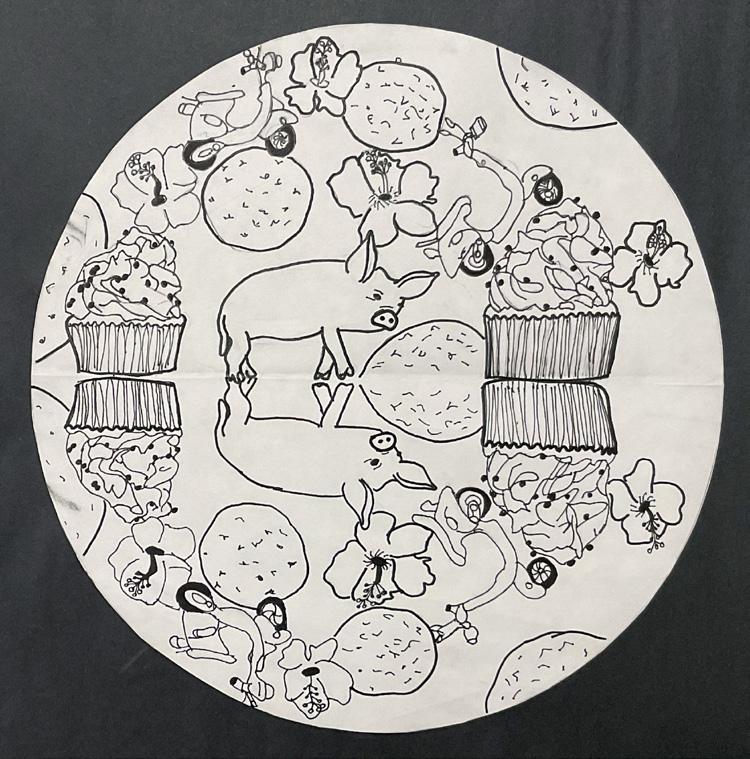

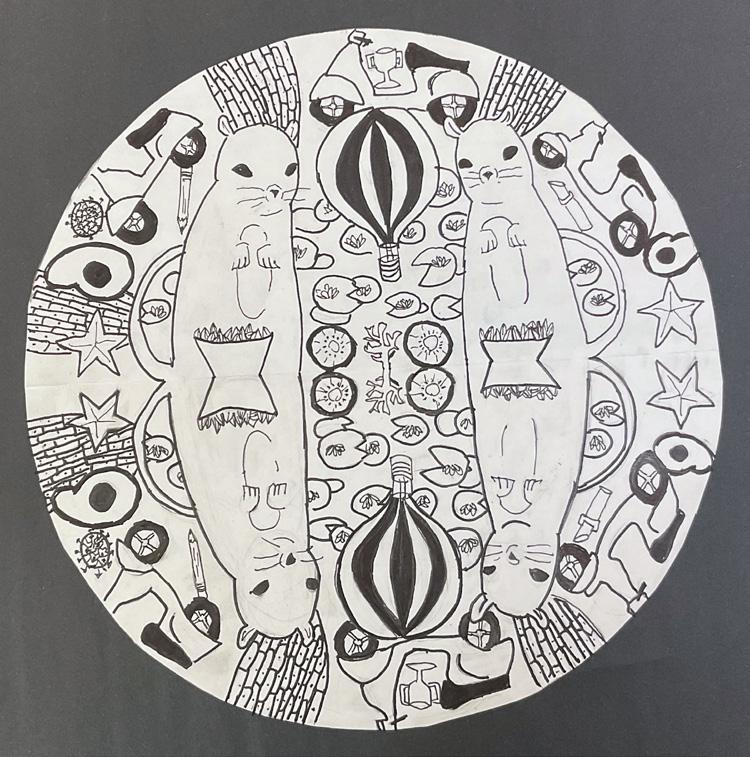

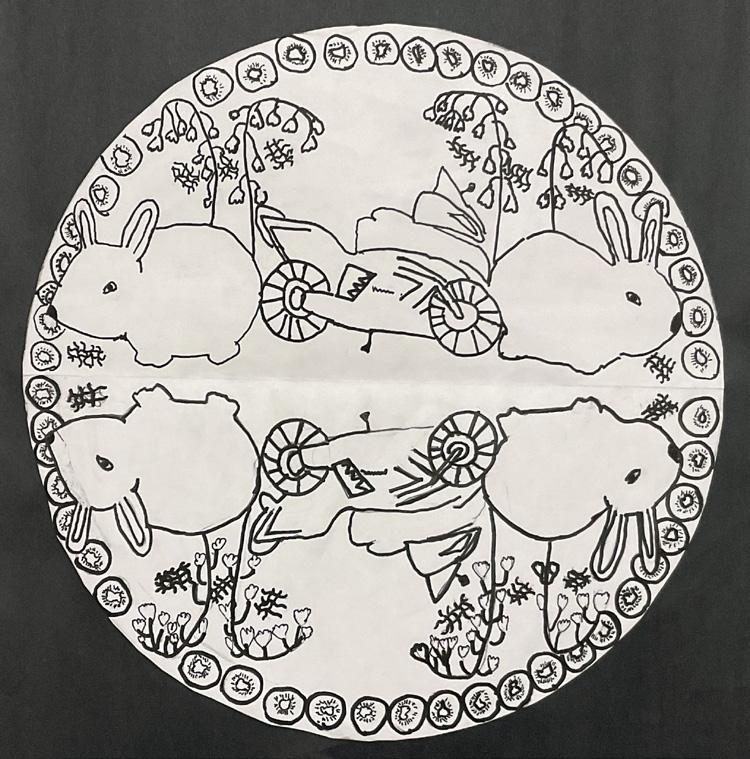

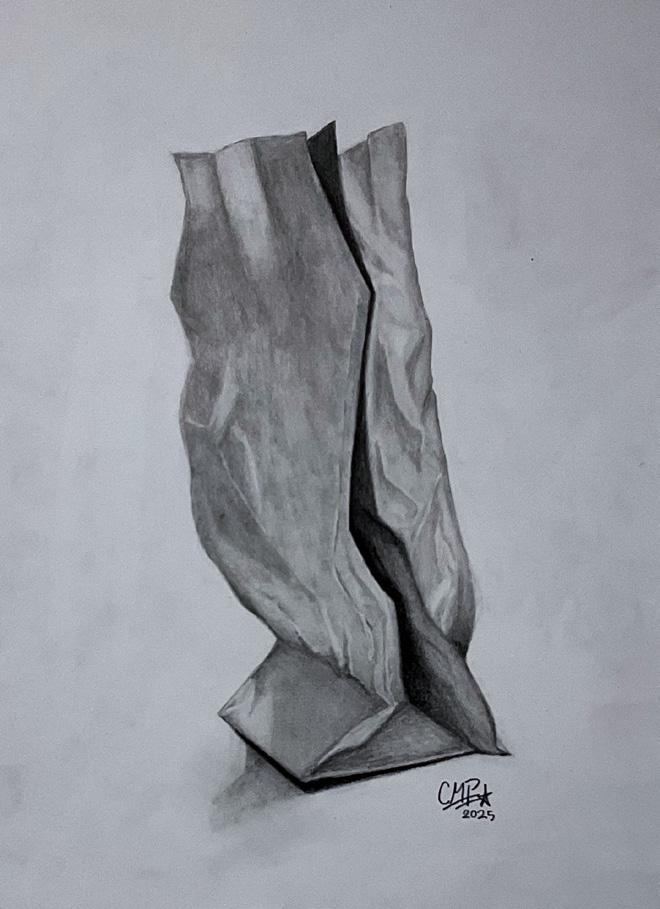

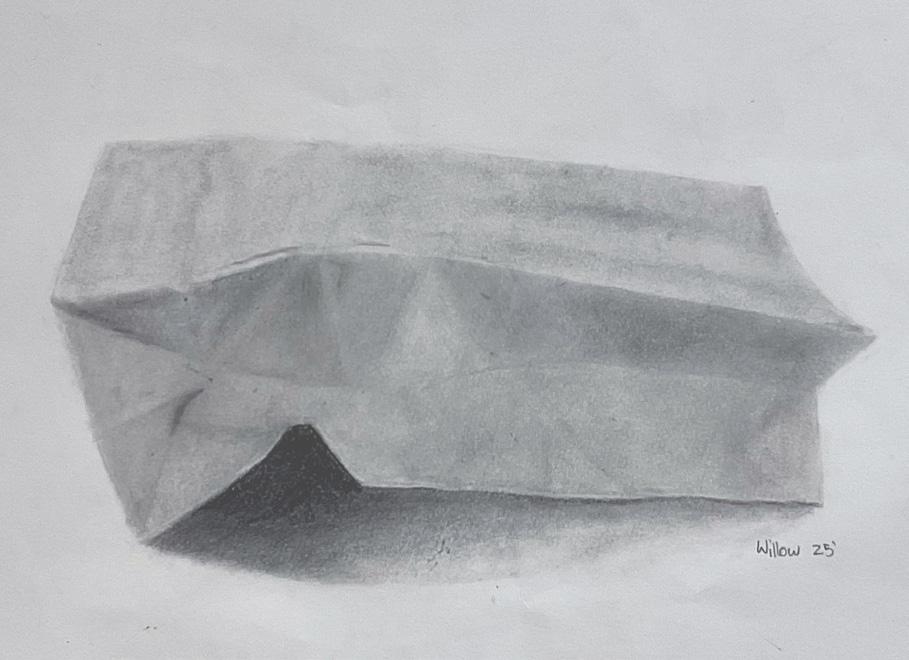

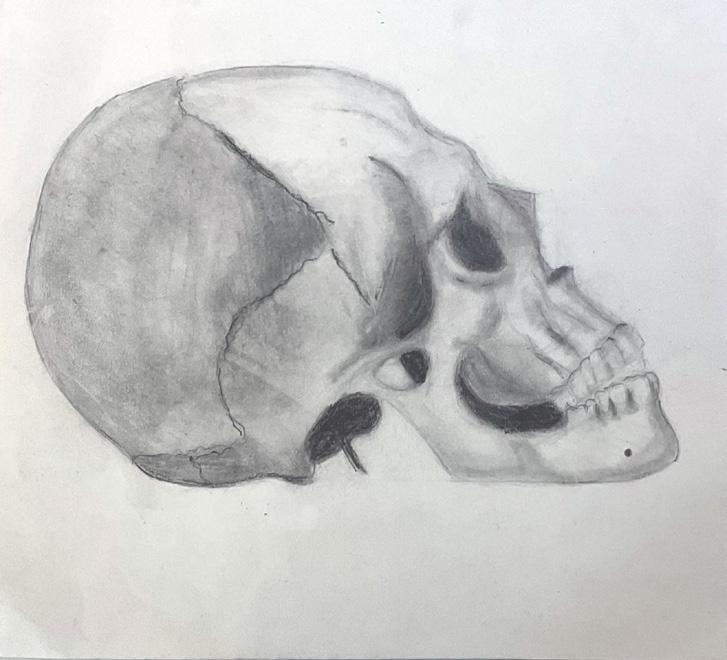

Studio Art 8 Sphere Drawings: Jack Rizzo ’29, Julia Elmore ’29, Suhana Hemrajani ’29, Luciana Murelli ’29, Henry Slim ’29, Evan French-Brown ’29, Cal Portner ’29, and Willow Furlonge ’29.

VOICES

Tej Bakaya ’29

Hudson Bhatia ’29

Jordan Fass ’29

Willow Furlonge ’29

Eric Gao ’29

Samiya Gupta ’29

Fatim Halsey ’29

Julius Hammer ’29

Arjun Kapoor ’29

Sankirtha Kapoor ’29

Julie Lan ’29

Trevor Meeker ’29

Lindsay Polanskyj ’29

Emma Ross ’29

Emi Simonds ’29

Kaavya Sinha ’29

Henry Slim ’29

Cecelia Spagnoletti ’29

Logan Jones ’30

James Ruberton ’30

Miranda Walter ’30

Ethan Avigdor ’31

Noah Baker ’31

Sasha Chakraberti ’31

Elle Coyle ’31

Juliana Endeladze ’31

Max Gardner ’31

Ayla Gore ’31

Willow Hargrove ’31

Mia Jacobson ’31

Annabel Johnson ’31

Sid Krishnan ’31

Jayden Liu ’31

Seanna Lokker ’31

Navyaa Makin ’31

Mia Martinez ’31

Eva Newman ’31

Sophia Peguero ’31

Shaurya Ramesh ’31

Ryan Simpson ’31

Wilson Zhang ’31

Note from the Editors:

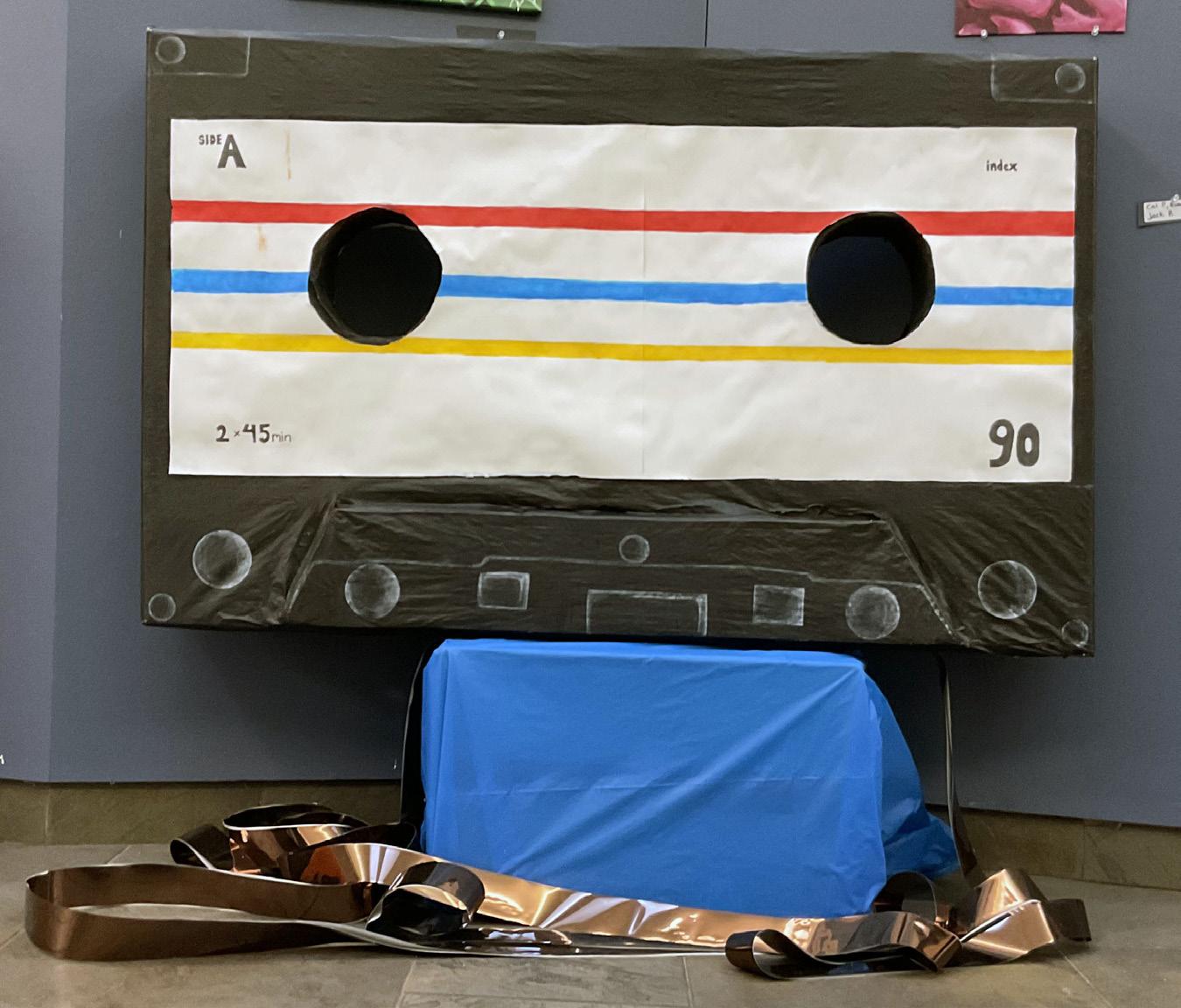

VISIONS

Kayden Chalfoun ’29

Julia Elmore ’29

Mekhi Fitzgerald ’29

Evan French-Brown ’29

Willow Furlonge ’29

Susana Hemrajani ’29

Chloe Jacobson ’29

Nazareth Johnston ’29

Julie Lan ’29

Kaira Lalwani ’29

Luciana Murelli ’29

Bram Nadelson ’29

Cal Portner ’29

Jack Rizzo ’29

Henry Slim ’29

Annie Watkins ’29

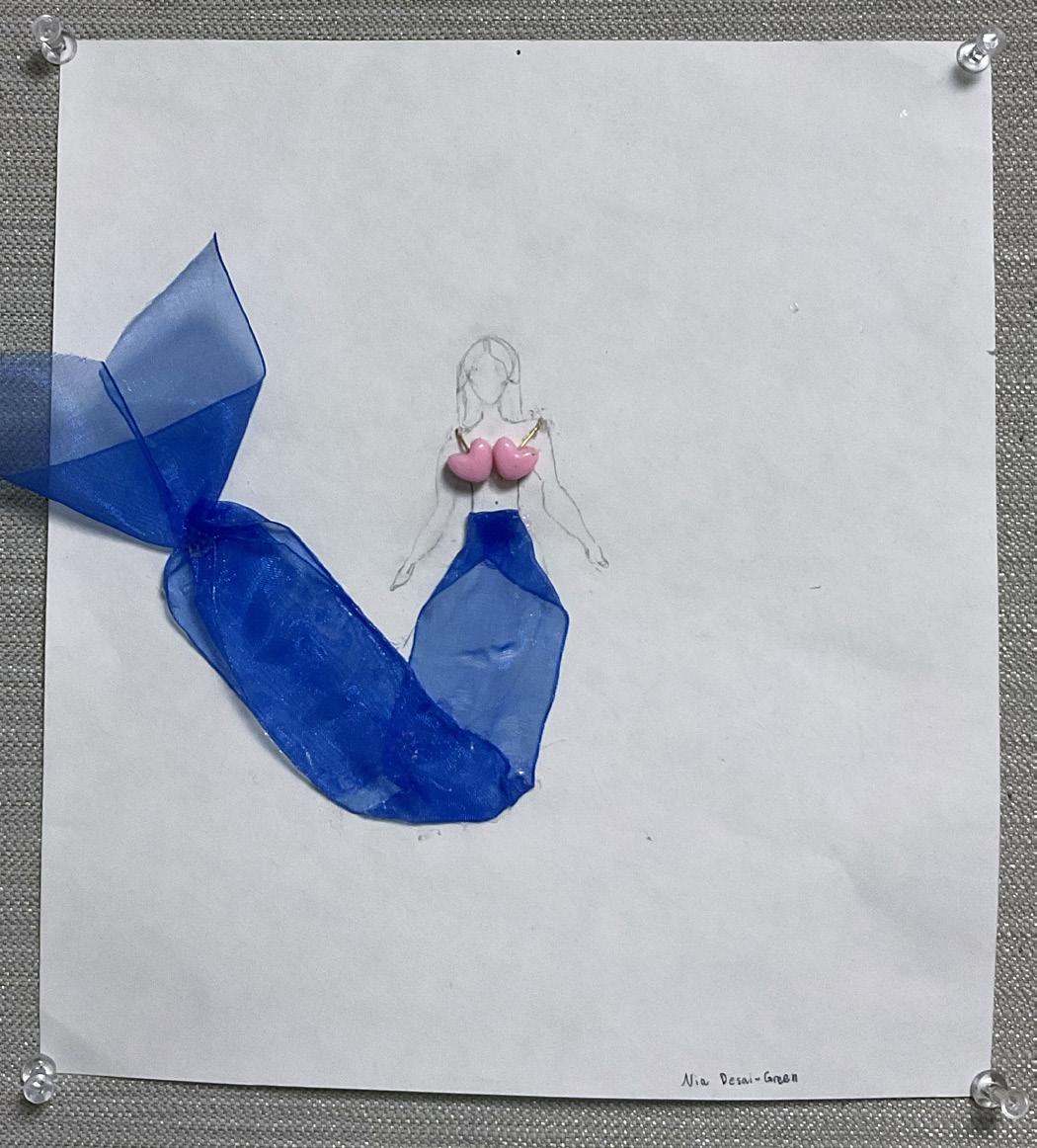

Nia Desai-Green ’30

Ngozi Dike ’30

Thomas Georgescu ’30

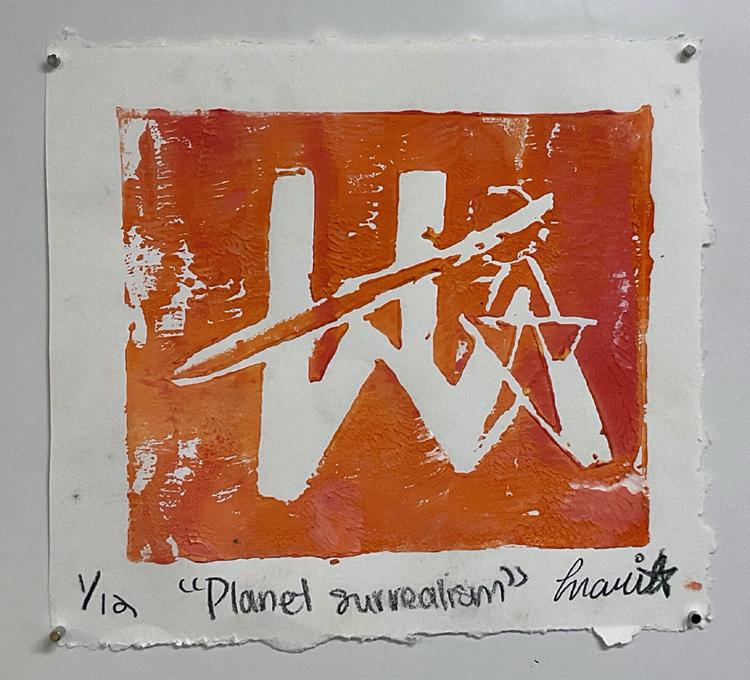

Marit Hedberg ’30

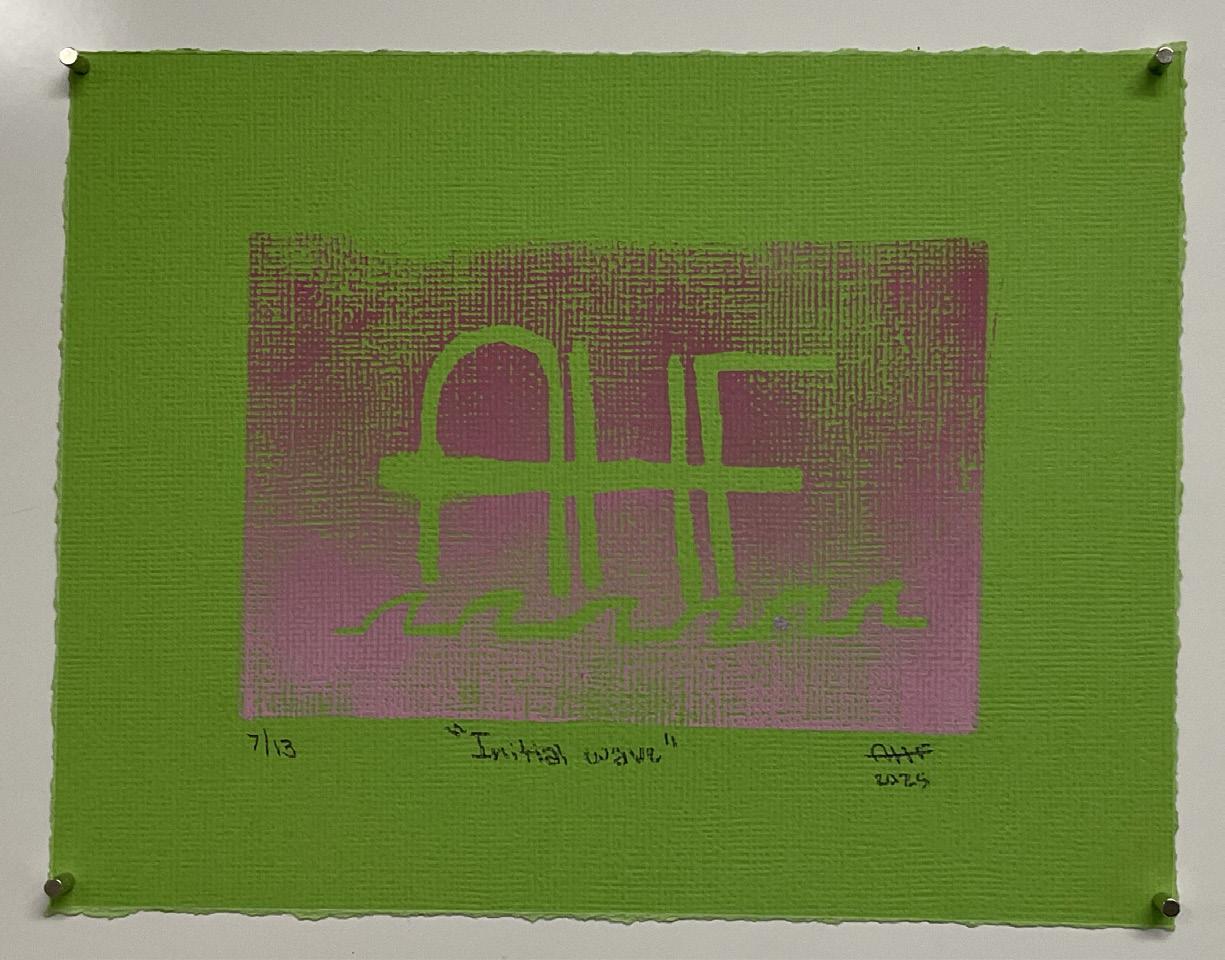

Alli Helmick-Fox ’30

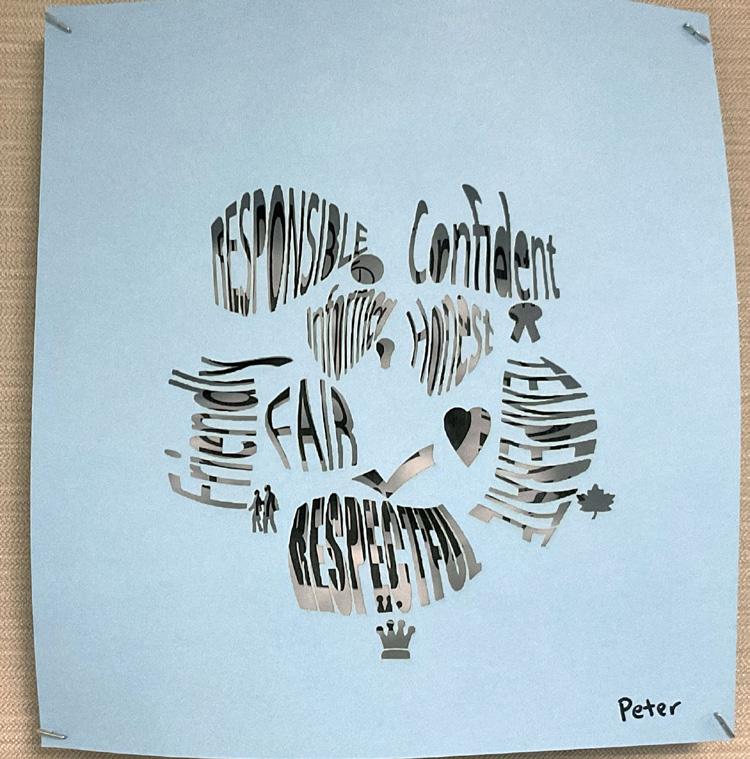

Peter Irwin ’30

Keshav Jagan ’30

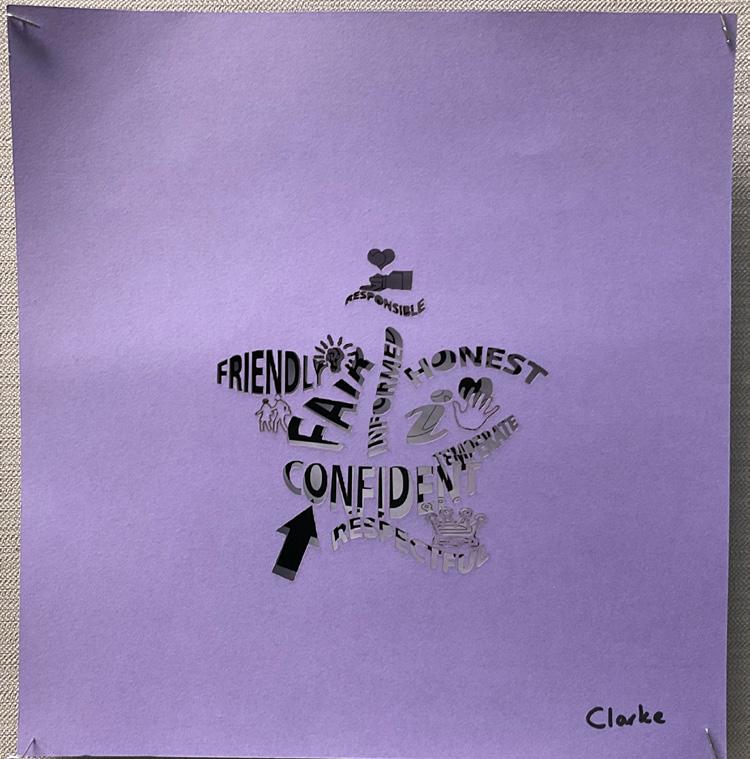

Clarke Jackson ’30

Claire Kiang ’30

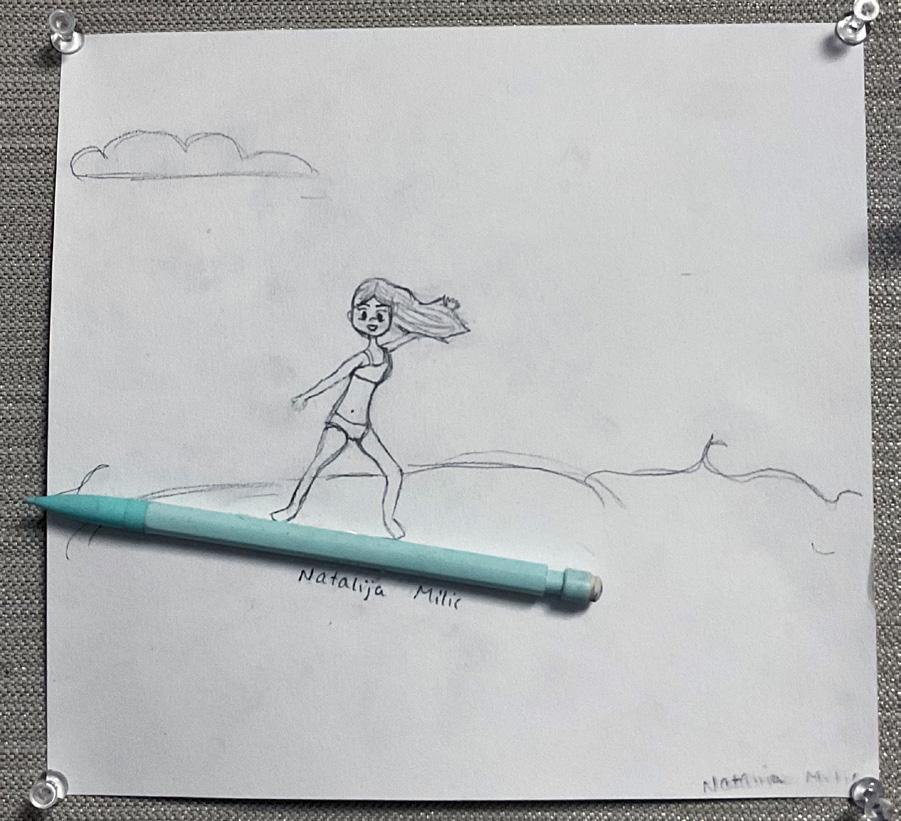

Natalija Milic ’30

Maddie Millon ’30

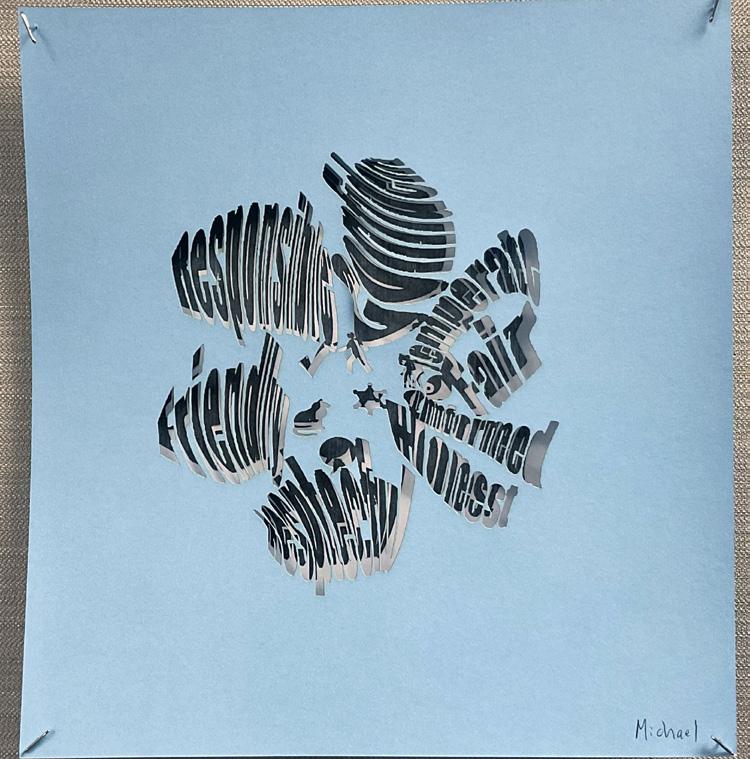

Michael Mullane ’30

Roma Patel ’30

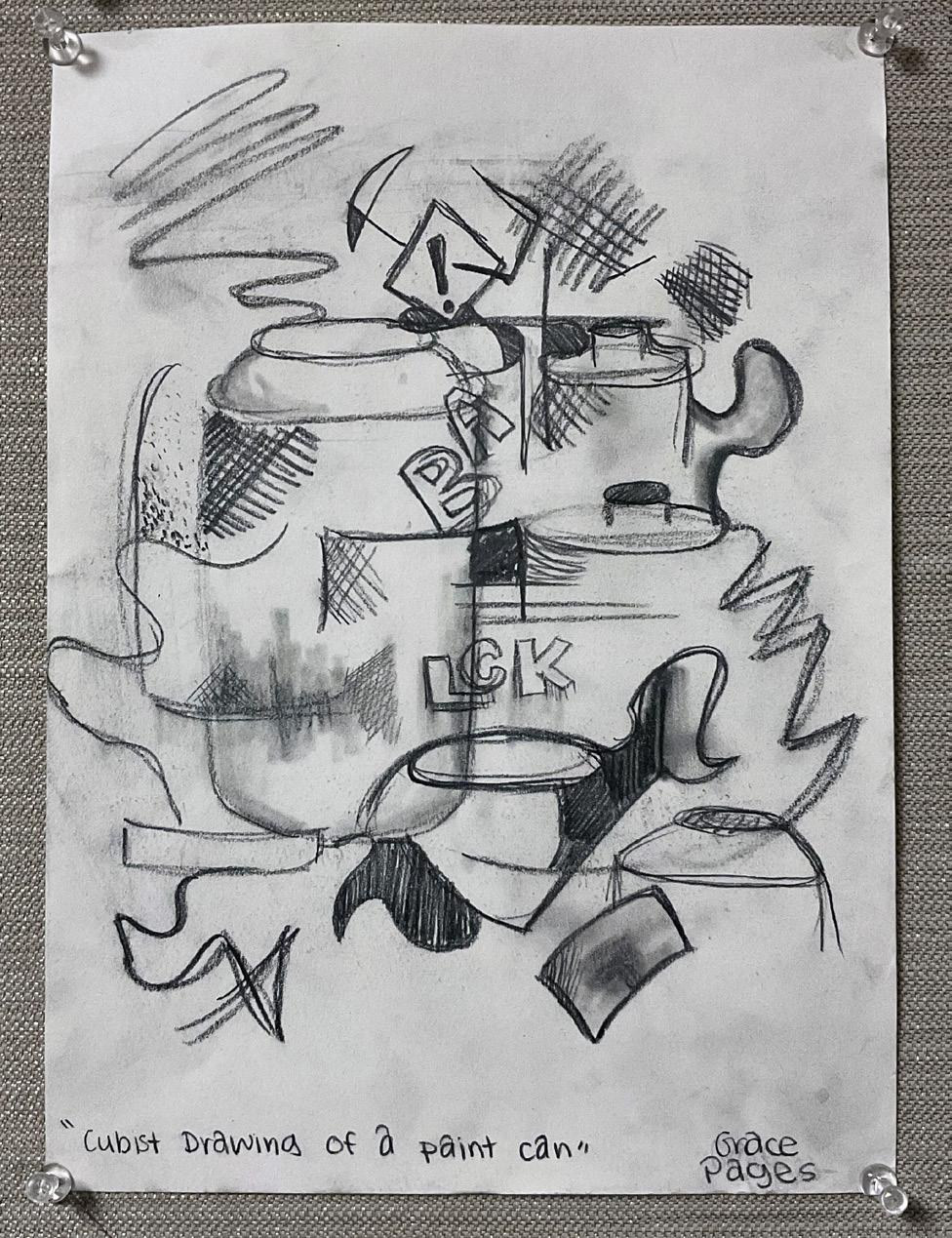

Grace Pages ’30

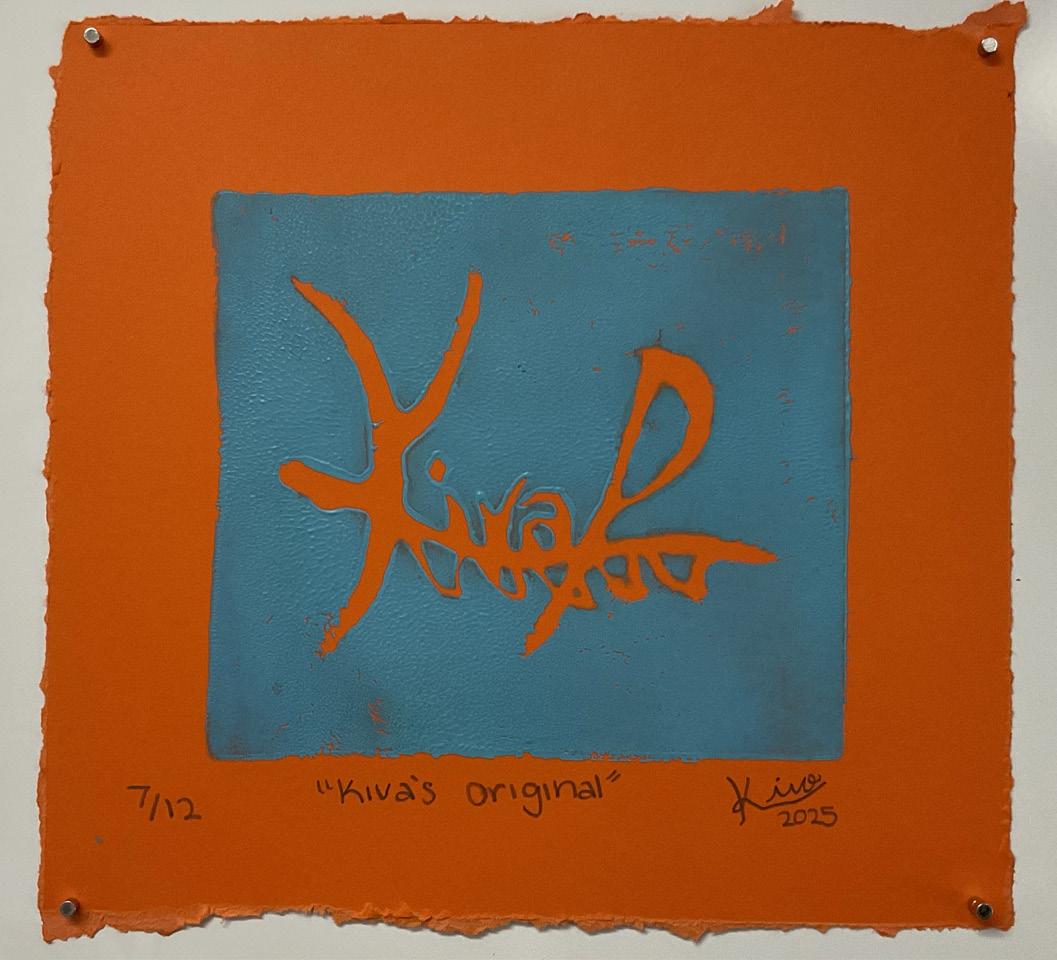

Kiva Pur-Rashid ’30

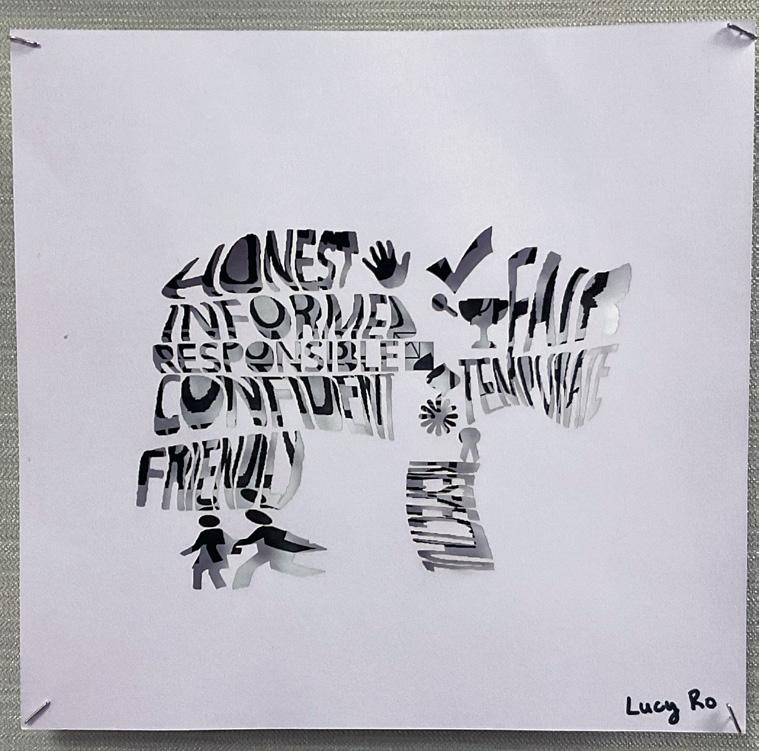

Lucy Ro ’30

Kaylie St Pierre ’30

Seneca Steplight-Tillet ’30

Nica Tagger ’30

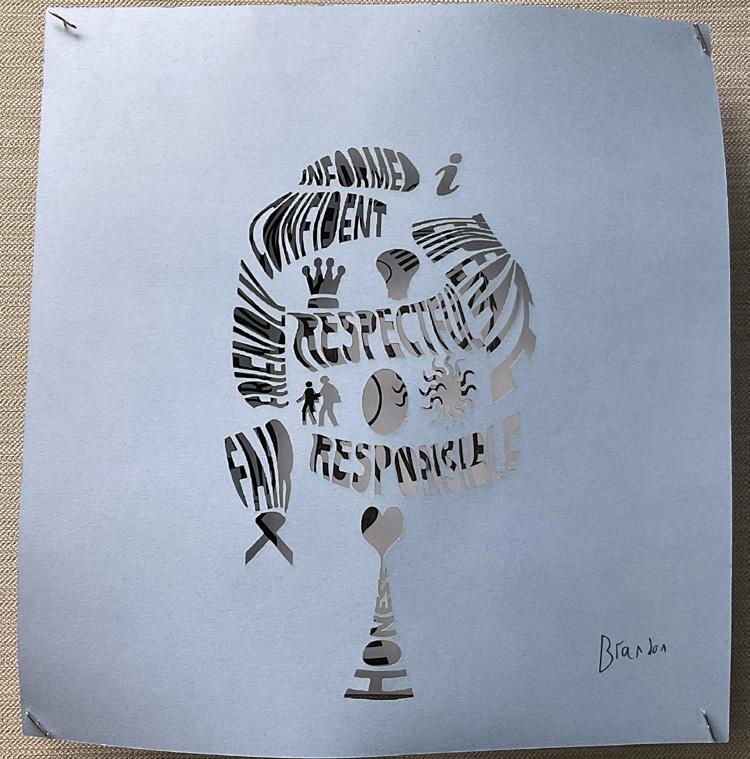

Brandon Treadaway ’30

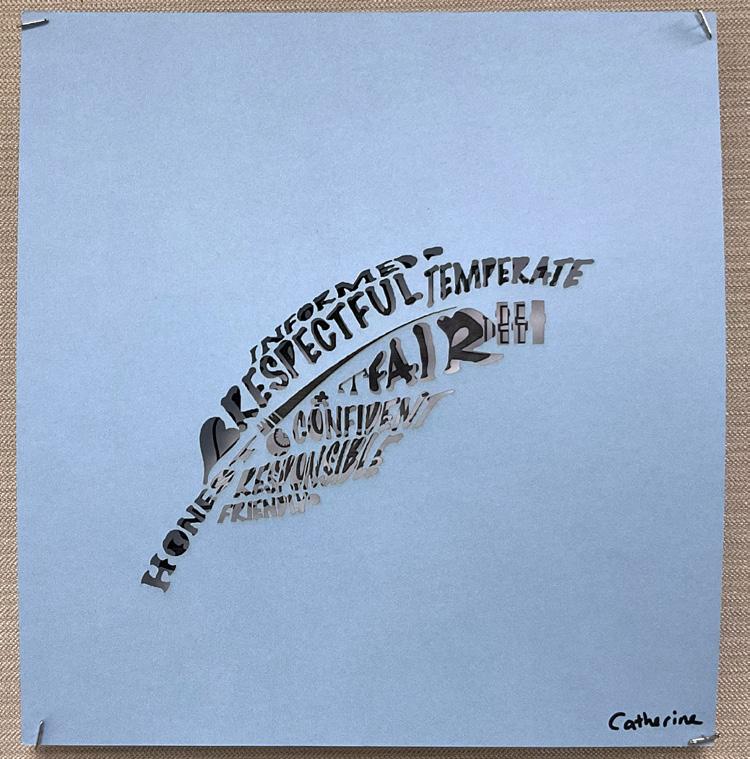

Catherine Xin ’30

Miranda Walter ’30

Reuben Whitman ’30

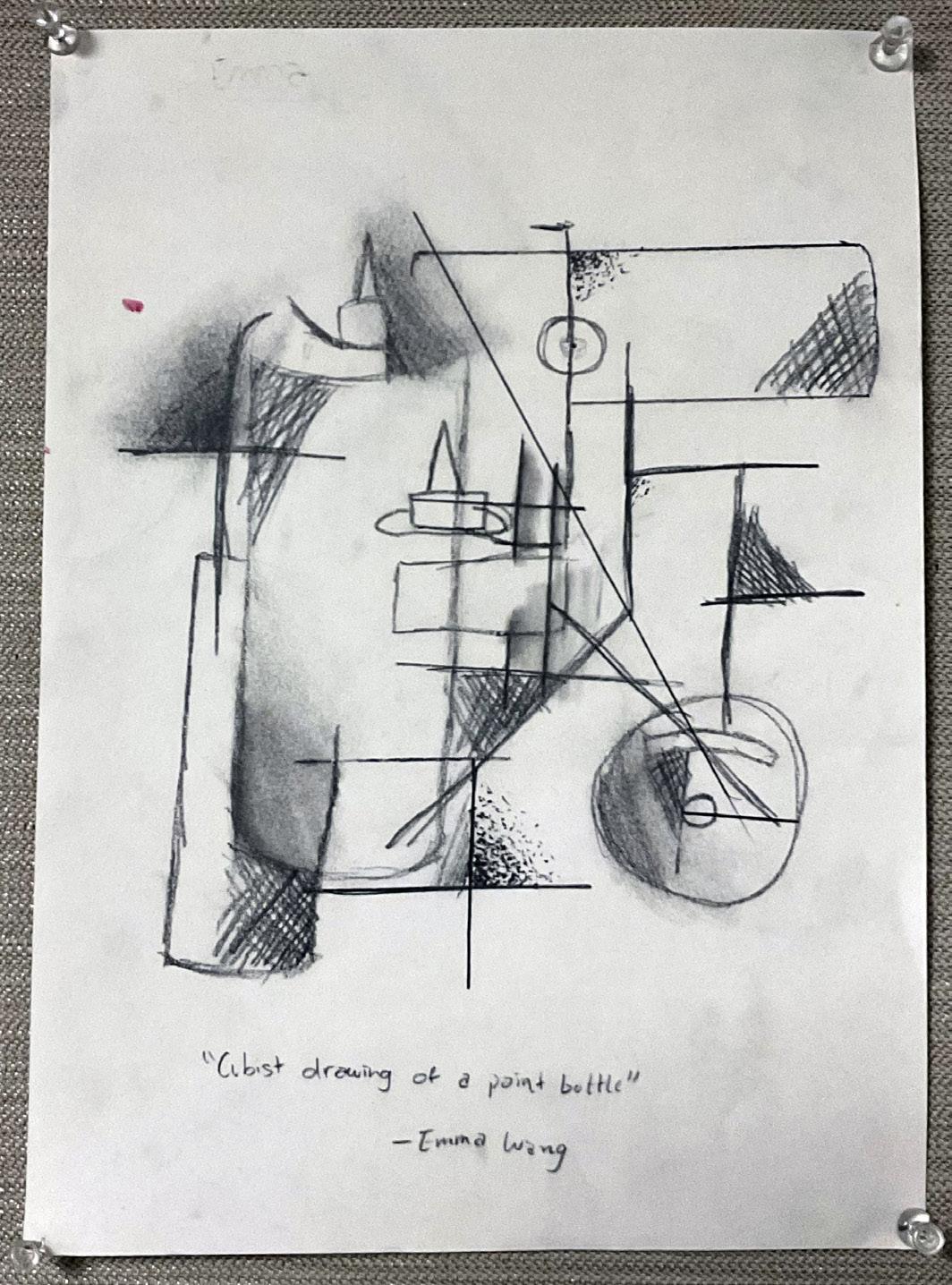

Emma Wang ’30

Isaac Zheng ’30

Madison Colotti ’31

Elle Coyle ’31

Jack Fraher ’31

Shaan Ghia ’31

Molly Harrison ’31

Giri Makin ’31

Maggie Rooney ’31

Alistair Townsend ’31

Ascher Willford ’31

Aspen Basra ’32

Ava Benjamin ’32

Jaden Bhatia ’32

Savannah Burke ’32

Caleb Chuang ’32

Gideon Feldman ’32

Adelaide Khublall ’32

Skylar Lokker ’32

Ryan Mullane ’32

Hannah Ross ’32

Caleb Silver ’32

Matthew Wager ’32

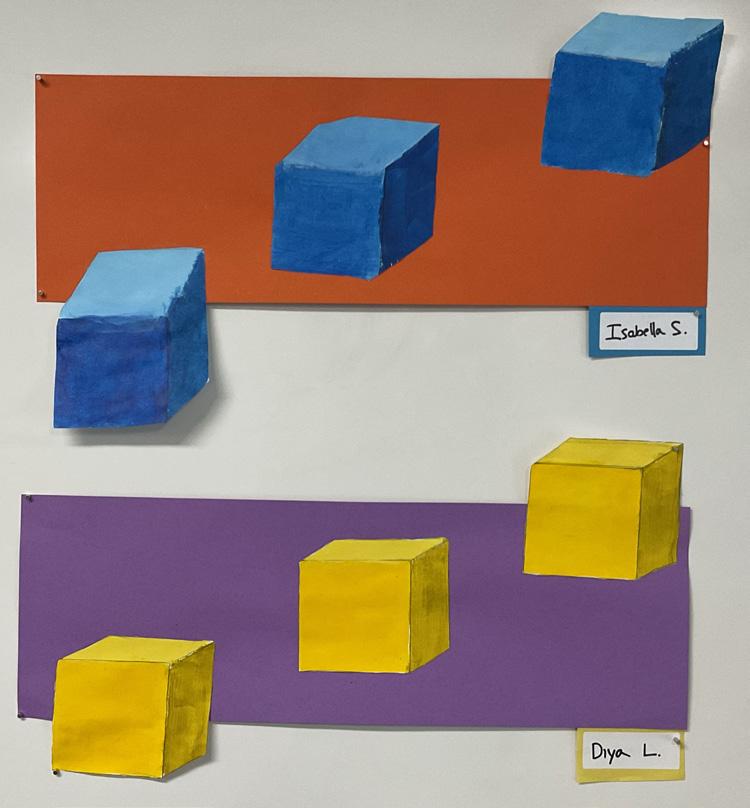

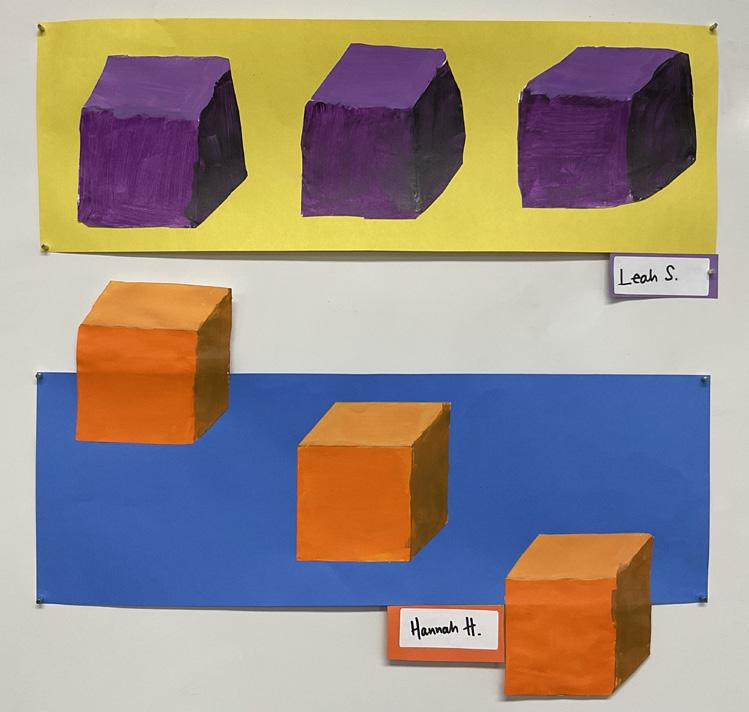

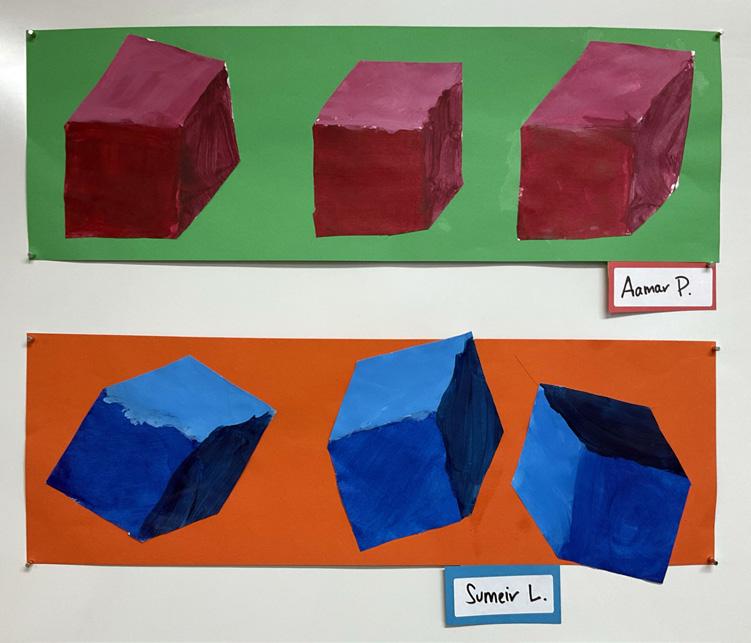

William Anthony ’33

Olivia Borrelli ’33

Maddie Gardner ’33

Hannah Higgins ’33

Grace Hoppe ’33

Avery Jia ’33

Sumeir Lalit ’33

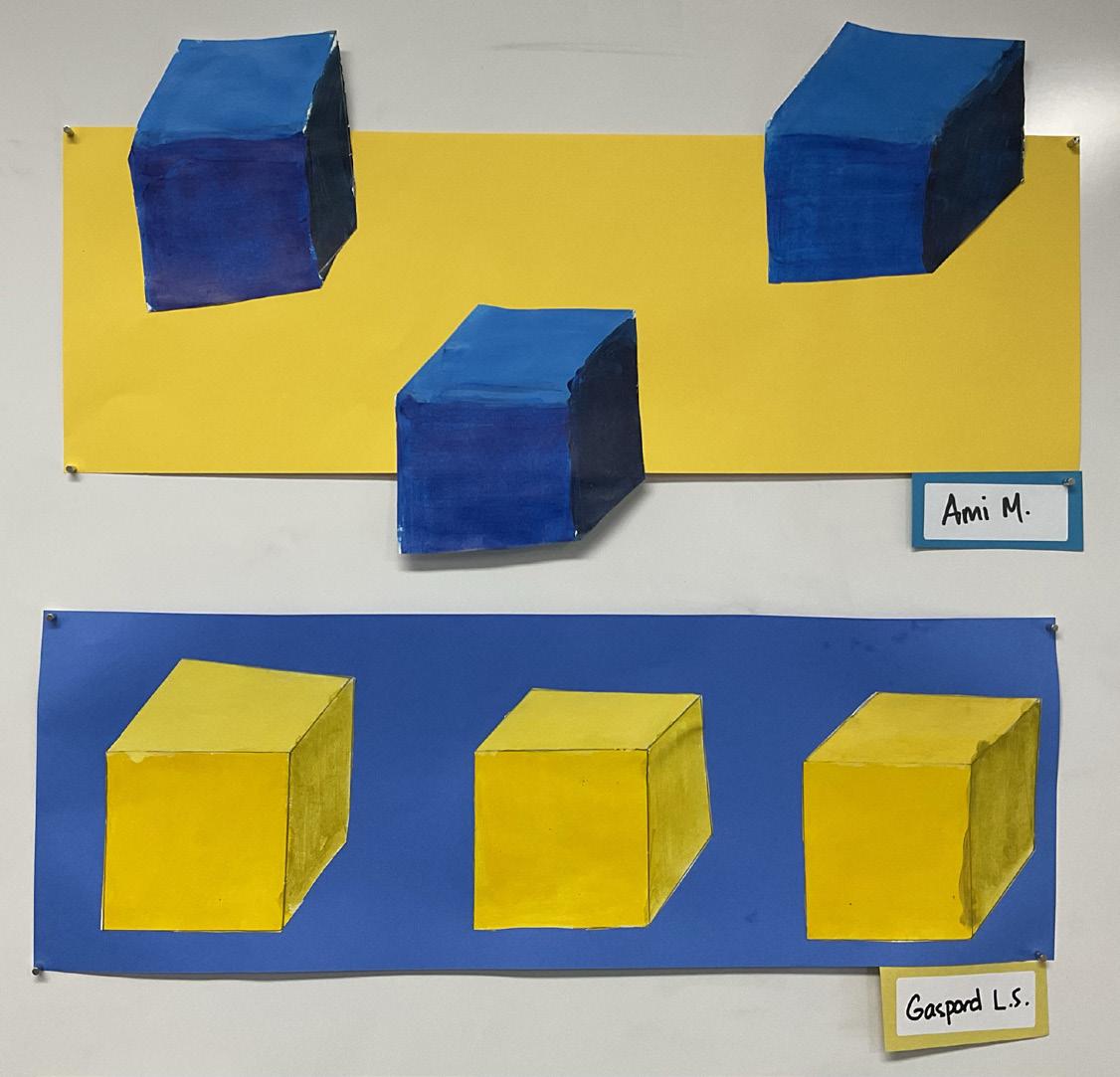

Gaspard Lemaire ’33

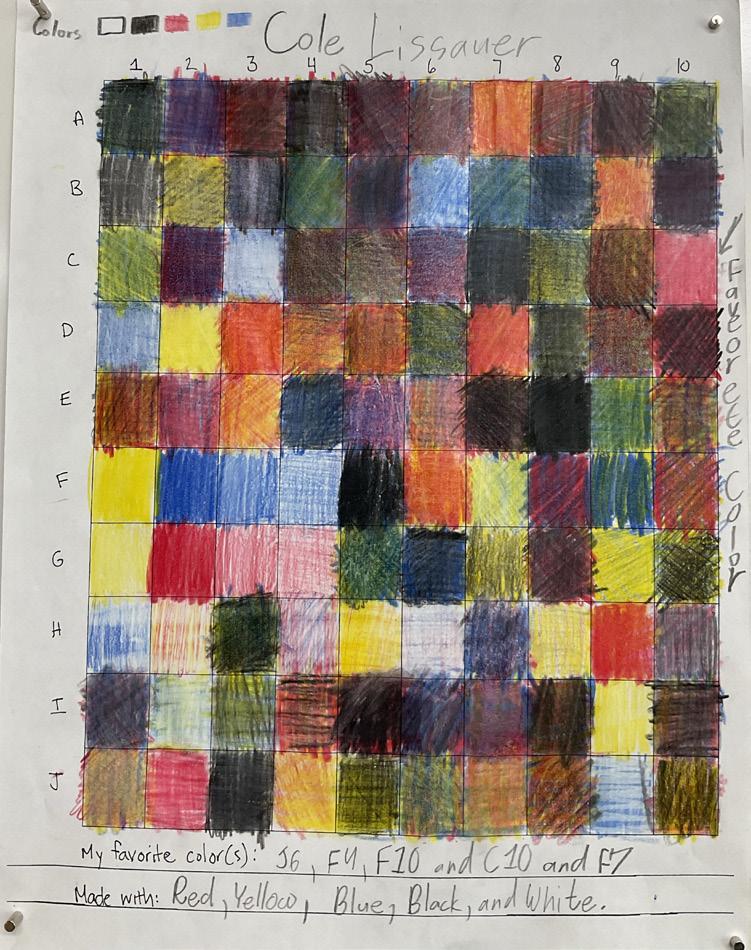

Cole Lissauer ’33

Diya Loganathan ’33

Amelia Morgan ’33

Ellie Nieves ’33

Sophia Pataki ’33

Aamar Patel ’33

Leah Shade ’33

Isabella Sousa ’33

Jane Sowers ’33

The 2025 edition of the Voices and Visions magazine has been nothing short of amazing. All the artists and authors have worked incredibly hard on their projects, and it shows. Each one of these students is extremely talented and gifted when it comes to their medium. Their work features abundant creativity while also letting their personalities shine through. This magazine contains beautiful and original artwork that encourages viewers to look deeper; poetry that showcases the environments these writers have observed and the genuine challenges they have faced; and creative and analytical writing that not only offers fresh perspectives on history but also inventive pieces that transport the reader into whole new worlds. Editing and publishing this magazine has been wonderful for both of us as co-editors. We have thoroughly enjoyed reading through all the pieces and looking at the art, and we hope you enjoy it as much as we did!

Sankirtha Kapoor ’29 and Kaavya Sinha ’29

Cecilia Spagnoletti ’29

I lay my tired hands upon the rough boulder in a swift fashion, a routine familiar as my own brother Kyklopes, though I rarely had time enough to spend on them. Another day of work had just begun. I stepped into my cave and prepared to rest after such strenuous work, but instead of laying on my warm, cozy cave floor, I was stopped in my tracks by the repulsive sight of–I can’t even say the word without gagging–men. With scruffy beards, shrimpy legs, and ridiculous looking clothing, I had to bite my tongue to keep myself from being sick, laughing, or both. I imagined that the men would at least remain quiet and accept defeat; everyone knows that we Kyklopes are undefeatable. If I had wanted to, I could have demolished them in under a second, but what fun would that have been? In spite of my abilities, I decided to initiate a conversation to understand from where these shrimpy little men had come to trespass on my island.

“Strangers, why are you here? Have you come simply to make my life more difficult? Don’t expect an ounce of hospitality from me, Polyphêmus, as I am too great for you little men.”

I knew that that would show them. The audacity of those creatures to simply barge into my cave and start a fire! How dare they? I expected a weary apology from the shrimp, but once again I was surprised as one of the grubby little sea urchins stepped forward.

“We are Akhaians from Troy. We came because we served under Agamémnon but got lost during battle. We are so lucky to have arrived on your shores, so please, any gifts or help you can spare are greatly appreciated. And after all, Zeus punishes those who lack Xenia.”

My beautiful, powerful mouth fell agape; I couldn’t believe the audacity. He had already ruined my afternoon, and now he expected gifts, as well! I was in utter disbelief. I spent nearly a second brewing up the perfect rebuttal to this mere mortal, and a pretty glorious rebuttal if I do say so myself.

“Take your Xenia, and go cry. I care not about the power of Zeus, as I, Polyphêmus, am far more powerful than he. If you think I would let you go and pass up a free meal, you are out of your mind, though I doubt you have one of those, you shrimp,” I retorted.

I thought that our conversation had ended. I had clearly won the debate, as I so often do, but the man decided to talk back to me, as a whiny toddler may to his nanny.

“Please, great Polyphêmus, Poseidon has taken from us our ship, our only hope of surviving and leaving your beautiful island. Please help us.”

That was it. This foreigner wanted to bring my father into this? My anger boiled; I felt it in my veins and in my lungs. I was breathing fire from my nostrils to my beautiful eye. These men had intruded on my afternoon, trespassed into my cave, started a fire, asked for gifts, and bashed my father. No words could express my anger, so I, in true Kyklopes fashion, grabbed the little men and tossed some into my great, beautiful mouth. I swallowed and watched the others begin to cry. I was confused; how could such emotions come from creatures so savage? It was nothing like I had seen before. I simply didn’t understand why it was such a travesty for me to eat men. Men shouldn’t act so high and mighty; they are known for eating nearly every animal in their sight such as sheep and cattle. Why should I even need to justify my choices?

As I thought this, I stared at their whiny little faces, and I decided against starting another argument. I simply left the cave and carried on with my important Kyklopes duties. When I returned, the weird little men came bearing a gift. Before they could present it, I snagged two more men as a little reward snack for my hard labor of shepherding. With horror in their eyes, the men offered me some of their wine.

“This wine is a gift from us. We thank you for your kindness, Polyphêmus. We brought it to encourage you to help us, but since we understand that isn’t going to happen, we will still let you taste some.” I grabbed their wine and lifted the bowl up to my beautiful lips. It was delicious–a pure delicacy. I had never tasted anything like it. I very politely demanded two more bowls, which were served to me with great triumph. The leader of the useless little shrimp then attempted to start conversation by informing me of his name: Nohbdy, a rather useless piece of information if you ask me. But Nohbody had been the kindest of the men as to give me the gift of this wine, so I gave him a delightful gift in return.

“Nohbody, I will eat you last of your friends. Thank you for the wine.” Fatigue had begun to come upon me, so I lay down on the floors of my gorgeous cave and let sleep pour over me. These trespassing men could wait until the next morning.

In my sleep, thoughts passed through me as gusts of wind, fogging up my mind. These men were such a burden. How could such a misfortune be bestowed upon me, a mere baby of the Kyklopes? To console myself, I just repeated in my mind that it would all be over tomorrow, and I could go back to living my perfect life without these little creatures in my way. With that, I let my nightmares be conquered by sweet dreams of meat.

I had finally achieved peace when out of nowhere, a sharp excruciating pain bubbled through my eye and nose and spread through my entire face. I couldn’t tell where the pain had come from until I heard the sizzle and pop of my poor, poor, beautiful eye. I shrieked in horror. In a daze, I tugged a sizzling spike from my eye, and I threw it as far as the eye–well, not my eye anymore as it had been blinded–could see. I was in such a dreadful haze that these were the only words I could utter:

“Nohbody has hurt me! Nohbody has attacked me!”

In my daze, I couldn’t understand why my Kyklopes brothers brushed off my screams of misery until after the whole event had occurred. The shrimp ended up escaping. I tried to hurt them with boulders, but my pain would never be reciprocated, as the men escaped from my land. In their escape, the leader further proved himself an idiot by shouting out his true name: Odysseus. In the end, they took both my vision and my dignity. I felt as if my life was over, and so the only thing left for me to do was ensure that Odyesseus’ was too.

Aspen Basra ’32

“The Suffering of Polyphemus”

Confined in a cave, defined as monstrous, I am a cyclops am I, a true slave of men

Living blissfully, feasting on humans so feeble

The great treachery of that man was truly so evil

Came into my cave while I munched on his men Stabbed me in my eye, and I could not see him Called out for my brethren, but they did not arrive He had expertly played me with a plan he’d connived

His name was not “Nohbdy” As he did tell me He made a fool out of me No one would help me

He almost got away and saved himself then But he could not resist taunting me again He announces to me my foolery, forgetting his great diligence, With my knowledge of his name, the gods shall burden Odysseus

He played a great trick on me His actions were quite cunning But the price he shall pay Is worse than all others

He has given me his name, A great fool is he With the knowledge of his name I shall plague harm on thee

I shall pray to the earthshaker, The god who trials him I shall order great harm And discourse unto him

O great Poseidon, the one who quakes the earth, Please do unto Odysseus as he so deserves His trickery and deception and as he so gloats I beg you to never allow him to return home

Make his journey so treacherous One of great suffering And display his great flaws And harm his own brethren

May they wind up on shores they cannot name May they run into creatures with frightening shape May they fall into pits of the darkest of shades May they run into circles and never escape

May suffering follow his men And proceed to harm them all They should never have harmed me then May they never return to Ithaka

How flawed is he, The one who commands the men He caused the downfall of them all The “great’ Odysseus

-Tej Bakaya ’29

Caleb Chuang ’32

Jaden Bhatia ’32

Perseus: Hello, listeners! Welcome back to the Heroes and Villains Podcast. I’m your host, Perseus, Medusa’s stone-cold killer (HAHAHA)! Today, our special guest is Polyphemus. Be sure to text 292929H if you think Polyphemus is a hero and 292929V if you think Polyphemus is a villain at the end of the podcast. Polyphemus, I think most of our listeners know you from your encounter with Odysseus. How is your eye doing? Polyphemus: Not good. Yeah, that’s what most people remember about me, but I had a whole life before Odysseus came along. I mean, really—nobody ever talks about my side of the story. Everyone just hears his version, and of course, he’s the “hero” in the myth, so I’m painted as the villain. But let’s be honest here, I had my reasons!

Perseus: Alright, you have a point, let’s hear it. What really happened?

Polyphemus: Well, first off, I was just living my life in my cave on the island, minding my own business. I took good care of my goats, milking them every day and making delicious cheese. One day, I was coming back to my cave when I saw this mortal and his crew, uninvited, eating my food, and expecting me to treat him with Xenia. I mean, this is not fair!

Perseus: Okay, I see where you’re coming from. But… you did react pretty violently. Didn’t you eat some of his men?

Polyphemus: Yes, but I was hungry. And annoyed. And I only ate a couple of his people…maybe two mouthfuls total. Blinding me by sticking a burning stake into my eye while I was asleep after he got me drunk was not fair play.

Perseus: Polyphemus, did you really give him a choice? You trapped him in your cave, ate a few of his men. And you weren’t exactly letting him leave.

Polyphemus: Maybe, but calling himself “Nobody” to trick me? That was cheap. I’m groping blindly, in pain, screaming for help from my brothers. They hear me yelling “Nohbdy’s tricked me, Nohbdy’s ruined me!” So of course, they didn’t come to help! I understand Odysseus is a master tactician, but still… that was a really dirty trick.

Perseus: Yeah, you have me starting to look at this situation differently. But what about after? When he escaped?

Polyphemus: Oh, that’s what really gets me angry! He could’ve just left quietly, but no, he stole my goats and teased me as he sailed away. He even shouted his real name and said he would have killed me if he could have. I was justified in trying to sink his ship with a boulder. That’s when I prayed to my father, Poseidon, to make Odysseus’s journey miserable.

Perseus: Well, that worked out for you! His journey home was far from smooth. Polyphemus: Exactly! People always say I’m the villain, but honestly, I was just a cyclops protecting his home from unwanted intruders. Wouldn’t anyone do the same?

Perseus: Yeah, I think you might have convinced some of my listeners. Polyphemus: Perseus, thank you so much for having me on and giving me the opportunity to tell my side of the story. Perseus: My pleasure. Listeners, remember, text 292929H if you think Polyphemus is a hero and 292929V if you think Polyphemus is a villain. See you all next week when we feature Prometheus!

A father. All my life I had yearned for a father. I remember my mother looking like a haggard and lifeless patient, patiently waiting for this man. I remembered the pride in her voice when she said my father’s name, Odysseus. I was always full of questions about him, what he looked like, if he knew me, when he was coming home, and she would say, “ Patience Telé. He’ll be home any day now, and answer all your questions for himself.” The ironic thing is, I never got the answers to my questions. My mother’s smile and resolve faded like the years and then there were only sobs and anguish. I didn’t cry when the first suitor came in. At 12-years-old, no one cared what I did, except Eurykleia who was always by my side. She also seemed to believe in this Odysseus; she told me my father was a strong man who would come back for me and my mother. That he would I thought that was wishful thinking; our family was broken because of him. I was adamant on the inside but on the outside, I desperately wanted a father and was so sick of the suitors. I wanted my mother to be happy and for her to smile again. By 19, I had accepted the reality that he was dead, but I knew I had to save my family somehow. Today that day finally came. I had a quest to find my father and save my family; I was going to find Odysseus myself.

Fatim Halsey ’29

Adelaide Khublall ’32

Skylar Lokker ’32

Arjun Kapoor ’29

He does not love me. I see it in his eyes, the way he looks to the sea, longing for the home he may one day see again. I have given him paradise, shelter, even immortality, and yet his heart still clings to that aging woman across the ocean who is nothing compared to my beauty. She will one day wither away, but I am everlasting. Now, Hermes commands me to let him go. Zeus wills it, and even I must obey. This heartbreaking news hurts me more than any blade and degrades my love. I am immortal, and his mortal wife, Penelope, is not. He chooses death over divinity. I will watch him build his raft. I will give him what he needs. Not because I wish to, but because I have to. Still, I will tell him how much I love him, that I offered him eternity, and he chose to be human. He is the fool here, I am not. I offered him what others would give their life for, yet he decided not to be with me. And as I sit and watch him prepare to leave me, I wonder what that aging woman who has nothing but struggle and sorrow can give what I cannot.

Julie Lan ’29

I have never feared before that day. Not the storms that split the sky, not the jagged cliffs that watched over my home, and certainly not men—small, brittle things that shattered under my grasp. But that day, I feared. The darkness swallowed me whole.

The morning was still, the sea streaked as the sun rose up in the sky. My sheep bleated as I milked them, their warmth a quiet comfort. I had all I needed. There was no emptiness in me, no hunger unfulfilled. Then they came.

I smelt them first; the stench of salt and sweat, the sharp tang of metal. I sealed the entrance with my boulder, a shield against intruders. Only then did I see them, shrinking into the shadows. Thieves.

Rage surged in my chest. Who were they to trespass, to steal what was mine? I crushed one, his bones snapping like twigs. The others recoiled, terror in their eyes. Did they think they could cheat me? They were mine now.

But I was blind before the darkness came. I drank the wine they offered—fiery and smooth as it went down my throat. Their leader, who was clever and arrogant, spoke boldly, calling himself “Nobody.” My thoughts slowed, my body lulled into ease. Then, fire.

A stake, searing hot, plunged into my single eye. Agony tore through me, a fire without end. I roared, clawing at the air, at my face, at my doom. The darkness, once distant, consumed me whole.

I tried to scream. I tried to tear the air apart, to claw at my face, but it was too late. Blindness overwhelmed me. Was this the end? I fumbled in the darkness, hoping for anything that would give me back my sight.

But there was nothing.

In the darkness, I waited. I knew they were still in my cave, hiding, watching me suffer. The night dragged on, endless. By the time dawn touched the world, my rage had been replaced by an awful, gnawing feeling. Did they think I would forget? I couldn’t find them. My hands, fumbling in the dark, touched only wool and flesh—the sheep, my only companions. No matter how much I reached, the men were gone.

And then I heard it. That voice, ringing across the waves, taunting me. Odysseus. A name that would haunt me for all eternity. The cunning one. The liar.

Was it the loss of my eye that doomed me? Perhaps. But I wonder now, even in my blindness, if I had been blind long before that day—blind to the arrogance in my heart, blind to the trickery of men, blind to the reality that I was not invincible.

Kaavya Sinha ’29

Twenty years. How is it that I had waited for this man for twenty years? For years, my mother waited with nothing but delusions of love. I had spent my entire life trying to live up to his reputation. For as long as I can remember, I was told about my father’s greatness: Lord Odysseus, the great tactician, the sharpest, most honorable man in all of Greece. I once looked at his reputation as something to honor; I held onto it as a replacement for the love I so desperately craved. I looked at my mother ’s loyalty as the ultimate symbol of love. But his honor is all but true. His loyalty is even more questionable than that. What kind of man leaves his wife alone to rot for twenty years? He let my mother put her dignity and happiness on the line with nothing but foolish hope. I was alone as I watched my mother fall deeper and deeper into depression as the suitors wreaked havoc on the palace. I dreamed of the day my father would return and restore its glory. We once imagined him on his journey, doing everything he could to come home. I can still remember the day we learned the truth. The pain on my mother’s face when she learned of his arrogance was even greater than realizing it was his own actions that kept him at sea–it was his own hubris that killed his poor shipmates! My grand image of him was shattered. I was so excited, so excited to finally escape this loneliness. I never really had anyone who looked out for me. My mother tried, but she was often too distraught at my father’s situation. My friends used to say that I must feel so proud to have a hero for a father. But he was never a father. A real father would have been there; he is nothing but an arrogant creature who only serves himself. After seeing what his hubris did to his shipmates, I can’t help but wonder how long until my mother or I will be the ones who suffer next.

Caleb Silver ’32

I have always felt different from my family. Unlike them, I have never desired the same power and vanity. I am condemned to live alone on this island. Do I ever feel lonely? The answer is yes—always. I long for connection. My family has consistently neglected me, but it bothers me less now. I’ve adapted to this isolation. No one has ever dared to question my sovereignty. I still recall the day he arrived. Odysseus. I will never forget him. His bravery left me in awe. The way he spoke and carried himself was full of confidence and wonder. Of course, before I met him his men had arrived, and my first thought was to turn them into pigs. I hadn’t put my powers to use in years! After all, I was just letting their true colors show. With a flick of my wrist, I prepare a feast fit for kings. The beautiful smell of roasted meats and sweet wines fills the air as I welcome these strange men into my home. I watch them closely as they eat and drink to their heart’s content, unaware of what’s in store for them. As they finish their last bite, I raise my wand turning them into what they truly are. Once where men stood now lies a herd of swine. While I was admiring my work, I felt an unwanted presence; a strange man walked in. Dark-haired with eyes lit with mischief. Must be their leader. Without even talking to him I can already tell who he is. He walks with boldness and courage and a smirk on his face, blessing the room with his presence. A smile rests on my lips. Perhaps this encounter will be more interesting than I had expected. After all, it’s been ages since a mortal has truly questioned me.

“Polyphêmus”

The waves still taunt me with his name The wretched man who stole my eye. A trickster with a liar’s aim, And yet, the gods let him slip by.

My cave, once bright with a flame, Now drowned in the dark and all hollow. No warmth, no sheep, but all the blame Here I lay, with nothing but my own sorrow.

Calling himself a name so small, A joke upon my terrible pain.

“Nobody” made a giant fall, Now I’m stumbling in the rain.

What good is strength when wit is sharp, When gods and men both point and mock? They called me a monster, they made me a mark, But I was wronged, and I am still in shock.

-Henry Slim ’29

Gideon Feldman ’32

Hannah Ross ’32

Matthew Wager ’32

I’m from purple hydrangeas and blackberry bushes. I am from barefoot backyard adventures, and mid-afternoon meals filled with humbow and spring rolls. Lego weekends and heated floors.

I am from pub dinners with mac and cheese and perfectly cut fries. I am from light up shoes and gumbo on Christmas. I am from “Let it out, and always be thankful.”

I am from street bike rides turning into a bmx race with big hills.

I am from snow days and ski weeks.

I am from Alderbrook, it’s salty air I know so well, how a leaf could be a boat, and to never be afraid of crabs.

It’s s’more pits I know so well, and nice people.

In those

Cold waters, my memories STORED in its days. I am from water.

-Sophia Peguero ’31

Sagacious and strong, and usually sure.

Observant and open-minded, but not always optimistic.

Passionate at ice skating, productive, usually polite.

Heartfelt and honest, hardworking for what she thinks is right.

Imaginative and independent, insightful at all life. Adventurous, artistic, admirable, and right.

-Sophia Peguero ’31

Where

I’m From

I am from blueberry pancakes - cooked, fried, and crispy Me and my sister fighting over who gets to put in the blueberries

The satisfaction of flipping over a golden brown side to the next.

I am from hot summers and backyard hoses My face boiling until cool sprinkles of water soak my body. Me and my sister hopping around, laughing till we fall.

I am from everything bagels. Every time I think about how I can’t eat more, and yet I always do.

I am from The Hate U Give, Dress Code, Climate Club, and ACT. The books I love to read. The smelly, honking cars, yet my happy place is Jersey City to the quiet town of South Orange.

I am from the stories my grandparents told me of family artists and immigrants who worked hard so each generation could live a better life.

I am from the determined Monica Conley and Eric Newman. Speak up for those who can’t. You shape the world, it doesn’t shape you.

I am from the inspiring stories of the activists like Mala Yousafzai, Sara Mardini, Warsan Shire, and many more stories that are yet to be told.

I am from day dreamers, Like Dancing On The Clouds

I am from the fear everyday might bring The Wake Up Nightmares

I am from Aaron, Eleanor, Edward, Robert, and Wanda their sweat, cries, and laughs.

I am from a trunk in the attic of all my great, great, grandparents’ belongings. Their sweat, cries, and laughs are part of me just as mine are part of them.

-Eva Newman ’31

Catherine Xin ’30

Isaac Zheng ’30

Where I’m From

I am from bruised knees

Tripping over crunchy ice and clear snow.

I am from tired nights

With welcoming, hot pasta.

I am from cold Sunday mornings

Running to the bookish blue car

Speeding to the place that smelled Of artificial cold and smoke

From cigarettes. Where I learned to skate And learned to cry.

I am from sweaty summer days

At the pool, begging For ice cream

Begging for my dad

To swim with us, To play motorboat.

I am from screaming, crying, kicking

Hating the evil eye drops

The huge needles

The scary dentist

And the sticky, disgusting medicine

That always tasted like bitter carpet and chemicals.

I am from shrieks of joy

Being flung down an icy white hill, plummeting

On a puffy sled, brother Right beside.

I am from fighting, yelling, laughing With my brother about “Who gets the Legos?”

Playing the flashlight game

Breaking collarbones

Scared of bumpy fingers Together.

I am from memories of love.

-Elle Coyle ’31

Where I’m From

I am from the condos of Maxwell Place, from a scar on my face from the stairs of Kidville. I am from the pretty sights of the waterfront. (Water, boats, riding ferries with my dad.)

I am from holding my dad’s leg being sad knowing he is going to work. My friend and I destroying the secret wood fort at the playground and protecting our city.

I am from Gaga and Four Square, from Hoboken and Manhattan. I’m from drinking apple juice and refusing to use straws. I embrace my mom’s care and my dad’s support.

I am from being annoyed at my sister but giggle and laugh too.

I’m from Malibu Diner and Elysian Cafe. Chocolate chip pancakes and chicken fingers. From rec soccer dread and my old best friend Charlie.

I’m from getting snacks a block away at Prime on Bloom. In California, my favorite chair spins over and over again.

I am from that special chair. My sister and I play with it all day. That was our entertainment. -Ryan Simpson ’31

Roma Patel ’30

Seneca Steplight-Tillet ’30

Like a spec on paper or a grain of sand

Truly a wonder

I see a miracle like a mother come back to life

I feel energy like the beat of 1,000 hearts playing in unison

I smell a hot popped water balloon on a hot summer day

I hear small booms and whines occasionally then nothing

I fall weary to the void of space

I taste a feeling

No

More of a sensation

Water Fire Peace

All my senses absorb it - not on earth

But in a world where I dwell

A world full of mystery

A world full of secrets

A elemental world filled to the brink with bright dots

Each powers its own world

And I feel like I belong -Noah Baker ’31

Thomas Georgescu ’30

Ngozi Dike ’30

Television

Everyday, I sit at the Same Exact Spot. A group of People had placed me Here.

They all look at me For hours, and they Laugh.

This is not funny, I try to laugh back At them, but all that comes out Are sounds Of Human gibberish, And funny music.

I feel like as if I am A statue, but one That makes noises and Cracks people up. -Wilson Zhang ’31

“Trees”

Watching the wonders of the world go by.

Standing tall with pride.

Their bark holds a story, waiting to be told. Swaying in the wind, their amber leaves of gold.

Towering over, sturdy and strong. Opposing the wind, all year long.

Bearing its branches when the cold weather sets, exposing beehives and birds’ nests.

Few leaves remain, hanging on tight, eventually succumbing to the leaf pile with nothing left to fight.

-Ayla Goore ’31

“Dancing Swirls”

Once I start, I only stop to think. Ideas come flooding in I’m an artist, as some would say. I make mistakes, but I can fix them. My friends fix me, and I can fix them. Sometimes I get lost, sometimes forever. But sometimes I get found. And I can do more, with new ideas But the more ideas, the shorter I get, And soon I am Nothing more Than Ashes.

-Mia

Martinez ’31

“Mirror”

Looking at me, every day, every hour.

You primp and preen over your hair, fix your lipstick, paint layers of color over your face. All you look at is yourself.

I see all of your life, never noticed unless you see yourself.

Vanity takes over your life. My shiny surface attracts you, staring at your flaws and imperfections. Never looking at anyone but Yourself.

Is my only worth my reflection of you?

-Annabel Johnson ’31

“The dance of the leaves”

The wind whispers through the trees, Shaking leaves with gentle ease. They spin and twirl in the autumn light, Dancing softly, day and night.

Their colors change from green to gold, A story in each leaf they hold. They fall, they flutter, to the ground, A carpet soft, without a sound.

The branches sway, the shadows play, As sunlight fades and night turns gray. The leaves are still, but not for long, But soon they’ll join the wind’s sweet song.

-Mia Jacobson ’31

“Wind”

I am unseen, invisible, Moving from side to side. I can either push you to your destination Or try to stop you.

Many don’t acknowledge me, But I am one of a kind, An incredible force, But even I cannot reach everywhere.

When I make my journeys, Everything in my path shakes. Trees are shaken, people are pushed, Smaller objects are thrown, All because of me.

I make the cold feel colder, A source of renewable energy. But I can make you waste it, Trying to push past me.

Every day, I do my tasks But rarely am I considered. People mention me Occasionally, But no one appreciates me.

-Sid Krishnan ’31

“Just a grade”

“You got an A? That’s surprising.” Like it’s not something I worked for. “Did you study, or just guess?” As if my effort doesn’t count.

It’s just a grade, but it feels different When people act like it’s all luck. They don’t see the hours or the struggle, Just the number on the paper.

There’s more to it than the score we see, But it’s hard to show them sometimes. Grades don’t tell the whole story, Because the story starts and ends with me

-Mia Jacobson ’31

“Flower”

A small but mighty buzz fills the air Whilst it collects my pollen. Then off it goes, back to the hive.

I started as a tiny seed, so delicate, With no purpose

With the help of soil, the sun, and water, I began To come out of my shell,

Approaching the sunlight Still, so purposeless. The only thing I can do is Grow.

My leaves expand and My petals burst into vibrance, Still so purposeless. The only thing to do is Grow.

Eventually, my petals become full, my leaves Are bright green, and I am full-grown.

A small creature with colorful wings comes to me and Starts drinking my sugar. Do I have a purpose?

Finally, the moment I have been waiting for! Bees and butterflies come to me For food.

Soon, my leaves begin to crumble. They no longer have Their bright green color and My petals are losing Vibrance.

I slowly fall back onto the ground Where I once was.

-Seanna Lokker ’31

“Asthma”

You breathe deep. And they stare. “Why can’t you just breathe more air?”

They just don’t see. The fight inside. How every breath, Is a struggle to hide.

Each inhale, A battle Each inhale A small victory

-Ethan Avigdor ’31

Natalija Milic ’30

Maddie Millon ’30

Inventions of the Han Dynasty

Max Gardner ’31

During the Han dynasty huge advancements were made in technology, literature, and science which drastically changed life in China at that time. The Han dynasty ruled for over 400 years from 206 BC to 220 AD.1 In those years, the Chinese enjoyed life with peace and prosperity.2 Liu Bang was the founder and first emperor of the Han dynasty. Wu-Ti, the seventh emperor, helped iron become a big, booming business in China at that time. As a result, Wu-Ti was thought of as the best ruler because he made the economy better. The inventions that enhanced Chinese life during the Han dynasty were the development of the blast furnace which produced higher quality iron, improved farming tools like the moldboard plow and wheelbarrow, and the invention of paper which helped in many aspects of life, including education and the military.

When the Han invented the blast furnace, they made higher quality iron which they used for many important things. The Chinese heated cast iron and then let it cool down slowly. Over time, this led to a broader change in how the Han were making tools and weapons because the process was much faster.3 Later the Chinese learned to melt cast iron and wrought iron together to make steel which was used to produce longer and stronger swords.4 This was a turning point because this process allowed the Han to make higher quality things they used in numerous areas of life. Weapons like swords were improved by making the blades sharper and longer with the stronger steel that was made in the blast furnace. From this, it can be inferred that the Han were more successful in battles because of the superior swords that they produced.5 As time passed, iron started to get used more during the Han dynasty. It was used for body armour to protect people during war. It was also used to make stronger shields and to make helmets.6 Farming tools like moldboard plows and wheelbarrows got stronger because of iron so farmers could use them a lot easier. The long-term impact of this was that those farm tools helped make more money for the Han.7 The work on farms was going faster because of new and improved tools so farmers were able to grow crops faster and could also sell them faster. Blast furnaces helped the Han quickly make better weapons for wars, and they were also essential for making plows and wheelbarrows.

The Han improved past inventions like the plow and the wheelbarrow which made some parts of farming easier and helped farmers produce food faster. Many peasants in China were farmers and made their money from agriculture.8 After the Chinese people got better at working with metal, the plow was improved from one blade to two and one handle to two handles. As a result of this action, the outcome was that it was much easier to navigate the plow.9 The moldboard was the iron plate that turned over and broke up the soil which made it ready for farming. When the Han invented and added the moldboard to the old plowshare, the new plow was a big improvement.10 Since the farmers could break up the soil faster and more efficiently, they had an easier time preparing the land. Therefore, the farmers could grow things faster which helped them earn money quicker. 11 Additionally, growing food faster meant the Han people suddenly had more than enough food. Wheelbarrows helped farmers move loads around their farms more easily.12 When the Han first invented the wheelbarrow, the wheel was in the middle and the frame was around it. As a result, the weight was distributed better so the person pulling or pushing it had an easier time doing the work.13 This was significant because the farmers didn’t need as much help on their farms which saved them money since they didn’t have to employ as many people.14 Farming advancements were very beneficial for the lives of Han farmers, and they were able to keep track of the changes they made to improved tools like the plow and wheelbarrow when a stronger, sturdier paper was invented.

When Cai Lun invented paper in 105 CE, it became easier for the Han to keep records, write down achievements, and share ideas.15 Before paper, they used wood that was hard to carry and silk which was expensive so it wasn’t easily available to everyone in China. The Han tried out different methods to use the least expensive materials to make the best quality paper.16 Cai Lun’s paper was made from easily obtained materials like hemp fibers, fishing nets, and reeds so it was more accessible to everyone, sturdier so it lasted longer, easier to make, and less expensive. As a result, his paper became the writing surface everyone in China used.17 Paper helped literacy spread once books cost less and were easier to carry.18 Not only did paper give people access to things to read, but it also helped the Han have different ways to keep records.19

1 https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/Han-dynasty/601197

2 Baby Professor, The Han Dynasty : a Historical Summary Chinese Ancient History Grade 6 Children’s Ancient History (Baby Professor, 2021), [Page 66].

3 Wei Qian and Xing Huang, “Invention of Cast Iron Smelting in Early China,” ScienceDirect.com, accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667136021000017.

4 Sjsu.edu, accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/ancientchina.htm.

5 Sjsu.edu.

6 Cartwright, Mark. “Armour in Ancient Chinese Warfare.” Worldhistory.org. Last modified October 30, 2017. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www. worldhistory.org/article/1143/armour-in-ancient-chinese-warfare/.

7 “Han Dynasty Inventions,” Totallyhistory.com, accessed March 26, 2025, https://totallyhistory.com/han-dynasty-inventions/.

8 David Levinson and Karen Christensen, Encyclopedia of Modern Asia (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2002), [Page #], digital file.

9 Cartwright, Mark. “Achievements of the Han Dynasty.” World History Encyclopedia. Last modified September 14, 2017. https://www.worldhistory. org/article/1119/achievements-of-the-han-dynasty/.

10 Ru-Xi Yang and Wen-Bin Wei, “The Shape and Application of Moldboards During the Han Dynasty,” ScienceDirect.com, accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352409X24002840.

11 Yang and Wei, “The Shape,” ScienceDirect.com.

12 Cartwright, Mark. “Achievements of the Han Dynasty.”

13 thoughtco.com

14 thoughtco.com

15 David Levinson and Karen Christensen, Encyclopedia of Modern Asia (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2002), [Page #], digital file. 16 Cartwright, Mark. “Paper in Ancient China.” Worldhistory.org. Last modified September 15, 2017. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1120/paper-in-ancient-china/.

17 Cierra Tolentino, “Ancient Chinese Inventions,” History Cooperative, February 24, 2023, [Page #], accessed April 6, 2025, https://historycooperative.org/chinese-inventions/.

18 Cartwright, Mark. “Paper in Ancient China.” Worldhistory.org. Last modified September 15, 2017. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1120/paper-in-ancient-china/.

19 Josh Clark & Sascha Bos “Top 10 Ancient Chinese Inventions”

This was a turning point because the military could use paper to make maps for the first time which helped them with strategies and battles.20 In addition, different kinds of maps also benefitted the government, people sailing in and out to trade, and other Chinese people.21 Paper was used for packaging medicine, tea packages, hats, and wrapping paper for presents. Stiff paper was used to make armour and windows were made from extremely thin paper. It was even used for household items like screens, sheets, curtains, clothing and, later, paper money.22 Once paper became easier to make, the Han could make large quantities of it. The Silk Road helped paper reach other places so people all over the world could record important information and share knowledge.23 History was changed because of paper.24 The invention of paper transformed life during the Han dynasty, but it also benefitted people all over the world.

Better quality iron from the blast furnace, sturdier farming tools like the moldboard plow and wheelbarrow, and paper all changed China for the better. The blast furnace aided the Han in making sturdier tools and weapons with stronger iron and steel. Improved farming tools helped the Chinese people farm their fields faster and easier which allowed the Han to produce more food at a faster rate. The type of paper produced during the Han dynasty was used in so many different ways that it affected all aspects of life. During the 400 years that the Han dynasty ruled in China, numerous significant improvements were made in literature, science, and technology. As a result of the countless, valuable inventions made by the Han, the dynasty had a substantial impact on life in China and the rest of the world.

Bibliography

Baby Professor. The Han Dynasty : A Historical Summary Chinese Ancient History Grade 6 Children’s Ancient History. Baby Professor, 2021.

Cartwright, Mark. “Paper in Ancient China.” Worldhistory.org. Last modified September 15, 2017. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.worldhistory.org/ article/1120/paper-in-ancient-china/.

Cartwright, Mark. “Armour in Ancient Chinese Warfare.” Worldhistory.org. Last modified October 30, 2017. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.worldhistory. org/article/1143/armour-in-ancient-chinese-warfare/.

Cartwright, Mark. “Achievements of the Han Dynasty.” World History Encyclopedia. Last modified September 14, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/ article/1119/achievements-of-the-han-dynasty/.

Copy Josh Clark & Sascha Bos “Top 10 Ancient Chinese Inventions” 1 January 1970. HowStuffWorks.com. <https://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/ inventions/10-ancient-chinese-inventions.htm> 26 February 2025

This is a website. The website will provide me information about Top Ten Inventions from the Han Dyansty this source will provide information about Top Ten Inventions from the Han Dyansty Davidson, Lucy. “Made in China: 10 Pioneering Chinese Inventions.” Historyhit.com. Last modified September 23, 2021. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://www. historyhit.com/made-in-china-pioneering-chinese-inventions/. “Han Dynasty Inventions.” Totallyhistory.com. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://totallyhistory.com/han-dynasty-inventions/. History.com. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.history.com/articles/han-dynasty-inventions#section_1. https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/Han-dynasty/601197

“The Invention of Paper.” TotallyHistory.com. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://totallyhistory.com/the-invention-of-paper/.

Levinson, David, and Karen Christensen. Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2002. Digital file. Made in China: 10 Pioneering Chinese Inventions. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.historyhit.com/made-in-china-pioneering-chinese-inventions/. Qian, Wei, and Xing Huang. “Invention of Cast Iron Smelting in Early China.” ScienceDirect.com. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S2667136021000017.

Rhoades, Robert E. “Agriculture.” World Book Student. Last modified February 21, 2025. https://www.worldbookonline.com/student-new/#/article/home/ ar007880/Han%20inventions.

Schlager, Neil, and Josh Lauer. Science and Its Times : Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery. Detroit: Gale Group, ©2000-©2001. Digital file.

Sjsu.edu. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/ancientchina.htm.

ThoughtCo. Thought Co. Last modified January 21, 2020. Accessed February 24, 2025. https://www.thoughtco.com/who-invented-the-wheelbarrow-1991685

This is a website.The website will give me information about the wheel barrow this source will provide information about the wheelbarrow ThoughtCo. Thought Co. Last modified October 27, 2019. Accessed February 24, 2025. https://www.thoughtco.com/chinese-inventions-examples-688061.

This is a website. The website will give me information about Chinese inventions this source will provide information about Inventions Tolentino, Cierra. “Ancient Chinese Inventions.” History Cooperative, February 24, 2023. Accessed April 6, 2025. https://historycooperative.org/chineseinventions/.

Yang, Ru-Xi, and Wen-Bin Wei. “The Shape and Application of Moldboards During the Han Dynasty.” ScienceDirect.com. Accessed March 26, 2025. https:// www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352409X24002840.

20 Cartwright, Mark. “Achievements of the Han Dynasty.”

21 Cartwright, Mark. “Achievements of the Han Dynasty.” World History Encyclopedia. Last modified September 14, 2017. https://www.worldhistory. org/article/1119/achievements-of-the-han-dynasty/.

22 Cartwright, Mark. “Paper in Ancient China.” Worldhistory.org. Last modified September 15, 2017. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1120/paper-in-ancient-china/.

23 Davidson, “Made in China,” Historyhit.com.

24 Lucy Davidson, “Made in China: 10 Pioneering Chinese Inventions,” Historyhit.com, last modified September 23, 2021, accessed April 6, 2025, https://www.historyhit.com/made-in-china-pioneering-chinese-inventions/.

The Golden Age of the Han

Sid Krishnan ’31

What defines a great civilization? A lot of wealth, lasting for a long time, or a large empire? All of these are potentially true. When you think about great civilizations, what comes to mind? Sure, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Rome, but what about the Han? The Han dynasty, located in modern-day China, lasted from 206 BCE to 220 CE. This dynasty was created shortly after the rise of the Qin and was followed by the 3 Kingdoms Period. Like nearly all the other dynasties, the Han followed the dynastic cycle, meaning it rose and fell. But even now, millennia later, it is regarded as one of the most impressive ones. So why was the Han considered to be so ineffable, to the point where it was considered a Golden Age? The Han dynasty epitomized a Golden Age of China due to its prosperous economy, its strong central philosophy, and its impressive achievements.

The Han dynasty built a thriving economy, which produced large amounts of wealth and contributed to its growth. Due to the previous dynasty’s harsh treatment and laws, the kicking off of the Han’s economy got off to a shaky start.1 This illustrates that the Han did not have it easy from the beginning. However, through large changes, it was able to become a substantial economy and grow from there. The Han’s economy was mainly centered on growing trade, population, and building industries.2 This shows that Han’s economy was focused on important concepts that all benefited the dynasty. The trading helped the Han gather new resources, and more industries helped advance technology. Since peasants were a key part of the Han’s economy due to their food production output, the government reduced taxes on poor landowners.3 This is significant, as it possibly saved the food economy. Since peasants created the biggest production of food, lowering taxes on the peasants prevented it from plummeting. At the beginning of the 1st century, China’s economy developed to a point where the Han would modify bronze and iron, making new items.4 This illustrates that the Han were able to contribute additional advanced metal and bronze items to the economy. These items, such as armor, or bronze utensils, would have entered the economy and contributed to the Han’s wealth. However, the main source of wealth from the Han’s economy was from effectively using the Silk Road.5 This is important because the Silk Road connected China to Western civilizations. The Han, who were involved with the Silk Road, used this trade to gain new wealth, items, and equipment. In the duration of the Han dynasty, their economy flourished, leading to impressive growth and increased wealth. The Han did not stop there. Having a strong economy meant they needed to have a good leadership style to follow. This led to the Han using a powerful philosophy of governing.

The Han’s governing philosophy, Confucianism, was a strong one and stabilized the Han for a Golden Age to take hold. It promoted integrity, justice, and how to live in society properly. The Han followed a Confucian set of concepts to, in a way, cover up some of the harsher policies, where the authority has all the power.6 This is significant because the Han’s philosophy helped protect the citizens of the Han from unfair rules, leading to a lower chance of rebellion, and a more enduring dynasty. Confucianism protected the Han government while also encouraging civilians to become better people. Confucianism was being used for the first time as a dynasty’s main belief system.7 This illustrates that the Han relied on this philosophy heavily. As a result, Confucianism stayed alive and is still active and followed today. The Han’s use of the central beliefs of Confucianism helped many people regard it as a strong dynasty. During the Han, efforts were made to recollect lost or hidden Confucian texts, and it mostly succeeded. Fu Sheng and other intellectuals saved some Confucian texts.8 These efforts were well spent–they reestablished Confucianism in the Han, which helped the Han thrive as they did. Currently, Confucianism still has believers, and they have something to follow because of the Han. The Han used Confucianism to help run the government, and they found that it helped to make highly valued, loyal officials.9 These highly valued officials would strengthen the government, and these officials would do a better job of governing the Han. To expand power, Emperor Wudi, (an emperor who ruled from 141 to 87 BCE) embraced Confucianism and established an imperial university to train government workers.10 Confucianism helped leaders gain power and expanded education. Confucianism gained the Han greater levels of authority. To teach the Five Classics of Confucianism, a program was created in a university, translated into modern script.11 Confucianism spread throughout the Han thoroughly, to where it was taught in universities to spread knowledge. This unified the Han, with nearly everyone following Confucianism. The Han’s powerful philosophy helped guide the Han and its people. Through this, they were able to strengthen the government. The Han’s philosophy, along with its economy, was part of what helped the Han create so many achievements.

The Han’s remarkable accomplishments are a major reason why it is considered a Golden Age. The Han dynasty was known for its accomplishments, which centered around inventions, government reforms, and civil service.12 The Han dynasty had a range of accomplishments, each impactful in their own way. These achievements each had beneficial effects, such as the civil system giving the Han stability, or inventions improving life in the Han. These all ended up contributing to the Hans’ power. Emperor Wudi, who ruled from 141 to 87 B.C, used his military strength to grow the Han Empire to a massive size.13 The Han was one of the dynasties that expanded what is now China to its current size. The Han Emperors, such as Wudi, were able to grow and expand the empire of China. This led to having more resources and having access to additional trade routes. Thanks to the Han, China was able to connect with western areas, gaining new trade, and a lot more.14 This was a key achievement because coming into contact with the West would lead to the creation of the Silk Road, which had a large impact on most of Asia. The Silk Road had countless effects, including the spread of Buddhism, disease, and more. It is likely that without the Han, we would not have had the Silk Road for a long time. Another big part of the Hans’ achievements was inventions. The invention of paper and its becoming ubiquitous resulted in significant improvement regarding literacy, which led to learning and writing on a high level in the Han.15 This achievement led to scroll paintings, a higher level of literacy and easier communication.16 This demonstrates how big an effect the Han had on the world. Even now, paper is a big part of our world, and back then, it might have been even more

1 “Han dynasty,” Totally History, accessed February 27, 2025

2 Han dynasty,” Totally History.

3 Han dynasty,” Totally History.

4 Jiang Yonglin, “Han dynasty,” in Encyclopedia of Modern Asia, ed. Karen Christensen and David Levinson (New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2002), 2:483, Gale eBooks

5 Han dynasty,” Totally History.

6 Brittanica, accessed February 25, 2025,

7 “Han Dynasty Religion,” Totally History, accessed March 26, 2025, https://totallyhistory.com/han-dynasty-religion/.

8 History.com Editors, “Han dynasty,” HISTORY, last modified June 22, 2023, accessed February 26, 2025,

9 Fredrik T. Hiebert et al., World History : Great Civilizations, student edition ed. (Chicago, IL: National Geographic Learning : Cengage Learning, 2016), 180.

10 Yonglin, “Han dynasty,” 2:484

11 History.com Editors, “Han dynasty,” HISTORY.

12 Brittanica, accessed February 25, 2025

13 Hiebert et al., World History, 180.

14 “Han dynasty,” Totally History.

15 “The Han dynasty,” Mr. Donn, accessed February 25, 2025, https://china.mrdonn.org/han.html.

16 Cynthia L. Jenson-Elliott, Ancient Chinese Dynasties (San Diego, CA: ReferencePoint Press, 2015), 36.

valuable. To add, during the Han, Xu Shen constructed the 1st Chinese dictionary, with different kinds of characters from the Han, Zhou, and Shang.17 The Han was the first dynasty to establish a set dictionary with a written language. This set the Han’s reputation as one of the most culturally advanced dynasties at the time. Iron provided a valuable chance to develop farming tools that would lead to larger, more beneficial harvests.18 Iron enabled the Han to create new farming tools, which led to a much larger surplus of crops, providing the Han with more wealth. Forming these new tools boosted the Han’s agricultural development. The Han’s achievements vary in topic, but all of them were beneficial to the Han. These achievements helped the Han develop as a dynasty, while growing the world of inventions and science, making a significant impact on the world.

A thriving economy, solid central philosophy, and remarkable accomplishments all helped the Han represent a Golden Age of China. Through this, the Han was one of the few civilizations that could heavily influence the world. Why is this significant? Many civilizations have risen and fallen, but only the most outstanding have been able to make lasting changes to the world. This shows that, as society keeps growing, the ones who can make a substantial impact on our world are the ones who are integral to our history. Only those civilizations are used to modify our current world. This is even true right now. Only the countries that can advance the world will be regarded as amazing, and those countries are used to build on as the world goes on. Ultimately, to truly be regarded as one of the best, a society must make a lasting impact; otherwise, it will risk being forgotten in the pool of idle civilizations.

Bibliography

Brittanica. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Han-dynasty.

“The Han Dynasty.” Mr. Donn. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://china.mrdonn.org/han.html.

“Han Dynasty.” Totally History. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://totallyhistory.com/han-dynasty-economy/.

“Han Dynasty Religion.” Totally History. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://totallyhistory.com/han-dynasty-religion/.

Hiebert, Fredrik T., Christopher P. Thornton, Jeremy McInerney, Michael W. Smith, Peggy Altoff, and David W. Moore. World History : Great Civilizations. Student edition ed. Chicago, IL: National Geographic Learning : Cengage Learning, 2016.

History.com Editors. “Han Dynasty.” HISTORY. Last modified June 22, 2023. Accessed February 26, 2025. https://www.history.com/topics/ancientchina/han-dynasty#confucian-revival.

Jenson-Elliott, Cynthia L. Ancient Chinese Dynasties. San Diego, CA: ReferencePoint Press, 2015.

Yonglin, Jiang. “Han Dynasty.” In Encyclopedia of Modern Asia, edited by Karen Christensen and David Levinson, 482-85. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2002. Gale eBooks.

17 History.com Editors, “Han dynasty,” HISTORY. 18 Jenson-Elliott, Ancient Chinese, 36-37.

Olivia Borrelli ’33

China’s First Empress: Wu Zetian

Navyaa Makin ’31

Envision the opulent and lavish halls of the Ancient Chinese Tang court, where the future empress skillfully handled schemes and plots, gradually eliminating her rivals until she got the power she sought. Wu Zetian (624 CE- 705 CE) was born in a wealthy family, received a good education, and married Emperor Gaozong of Tang (628 CE- 683 CE), eventually becoming Empress. In 660, Gaozong, the emperor, had a stroke that left him blind, passing control to Empress Wu, who ruled for twenty-three years as a de facto leader in the Tang dynasty. In 690 C.E., Empress Wu became the only woman emperor in Chinese history, declaring herself “Holy and Divine Emperor” and founding the “Zhou dynasty.” She ruled until 705 C.E., and despite her ruthless ambition, her achievements greatly benefited Tang China. Empress Wu impacted the Tang dynasty through a balanced leadership style, economic reforms, and her achievements that paved the way for China’s second golden age.

Even though Empress Wu was understood as merciless, her balanced leadership style had a positive effect on the Tang dynasty. She needed to be both firm and quick in her decisions to succeed in a treacherous political environment.1 This behavior might have been why people assumed she was being ruthless and harsh. For example, she had to be strong when substituting Empress Wang to become the highest level wife which was considered empress. Empress Wu’s quick handling of opposition led others to see her as a tough leader, often giving the impression of pitilessness.2 Had she taken a more cautious approach, she might not have been able to rise to power or maintain influence within the complexities of court politics. Her swift approach played a vital role in implementing major reforms and solidifying her legitimacy. She was also very intense at times. She faced many challenges but worked hard to reach her goals. Empress Wu was both charming and brutal.3 This indicates that her two-faced image helped her gain trust; the combination allowed her to navigate challenges effectively. It reflected her ability to use different leadership traits to sustain influence and achieve her goals. Empress Wu’s strength and directness led to an impression of cruelty. Her swift handling of opposition shaped her complexity in her character, allowing her to lead effectively in a constantly shifting political landscape. Nevertheless, she managed to have many beneficial economic reforms and achievements. Empress Wu implemented economic reforms and policies that benefited both the Tang dynasty and its people. She restructured the taxation system, increased the money supply, and promoted trade both within China and abroad.4 These changes boosted the economy, raised living standards, and brought lasting stability. Wu implemented these reforms to strengthen the economy, enhance state revenue, and stabilize her rule by promoting prosperity and solidifying her legacy. Empress Wu implemented agrarian reforms, including farming textbooks, irrigation systems, and reduced taxes.5 This is significant because Empress Wu’s agrarian reforms significantly boosted the economy by improving agricultural productivity through education and infrastructure, easing the financial burden on farmers with reduced taxes and a tax-free year. Empress Wu boosted Silk Road trade, offering a tax-free year while benefiting from its commerce, reinforcing her authority.6 Through hard work, Wu was able to reopen the Silk Road, which boosted economic development, so she implemented policies to ease the financial burden on citizens and encourage greater trade and productivity. She also had many changes to help the empire. Empress Wu revamped the taxation system and introduced reforms to stimulate economic growth and enhance her authority, including agrarian improvement. By promoting Silk Road trade, she aimed to gain the trust of her subjects. While her policies greatly benefited the Tang Dynasty, her legacy includes a broader range of achievements. Her leadership transformed governance, culture, and the economy, solidifying her as a key figure in Chinese history.

Empress Wu’s achievements strengthened her authority and paved the way for advancements during China’s second golden age. Empress Wu conquered several regions and had an extensive amount of cultural influence over Japan and Korea.7 Empress Wu reshaped imperial authority and expanded China’s influence, showing how leadership can drive both internal reform and regional cultural impact. Empress Wu replaced the old civil service examinations, which benefited from effective imperial management. Wu’s reforms would serve as a foundation for later dynasties to develop an even stronger examination system. 8 By altering the civil service structure, Empress Wu demonstrated how institutional reform can be used as a tool to centralize authority and legitimize political power, especially in times of dynastic transformation. She formed the “Scholars of the Northern Gate” to promote literature during her reign. Emperor Gaozong and Wu fostered a vibrant literary culture, leading to poets like Li Bai and Du Fu. Empress Wu’s Scholars of the Northern Gate promoted literature and intellectual life, which helped inspire the rise of famous poets like Li Bai and Du Fu. 9 Her support for the arts had a lasting impact, helping to establish the Tang Dynasty as a cultural golden age in China. The Tang Dynasty is widely considered the “Golden Age of Poetry.” Empress Wu, China’s only female emperor, achieved significant territorial expansion, influencing Japan and Korea. She reformed civil service exams to enhance imperial management and promoted literature by fostering the “Scholars of the Northern Gate,” supporting notable poets.

Empress Wu influenced the Tang dynasty with her balanced approach to leadership, economic reforms, and accomplishments that set the stage for China’s second golden age. Empress Wu’s reign was like a firestarter, igniting the flames of change in a dynasty that had been aching for a transformation. Her bold, often ruthless decisions set the Tang Dynasty ablaze with new reforms, cultural advancements, and economic prosperity. Even though men were set to be rulers, she proved them wrong like a tiny fire that could grow in just a few seconds. Like a fire that both destroys and renews, she cleared the old structures of power, paving the way for a stronger, more dynamic empire. Though her methods were sometimes harsh, they were undeniably effective, ensuring that her legacy would continue to burn brightly through the ages. Empress Wu’s leadership proves that sometimes, to create lasting growth, a fire must first be sparked.

Bibliography

Association for Asian Studies. Last modified 2015. Accessed March 8, 2025. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/wu-zhao-ruler-oftang-dynasty-china/.

Brownlow, Jamie, Abigal Eberhart, and Kristen Berndt. “Emperor Wu Zetian.” Storymaps. Last modified September 17, 2023. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://storymaps.com/stories/e9979b19b6ad47b7a884762814f12a06.

“The Incredible Life of Wu Zetian: China’s Only Female Emperor.” History Skills. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.historyskills.com/classroom/ year-7/wu-zetian/?srsltid=AfmBOoq6VZ52EnveaSeoYv-Tqzq1Kb-v2ri8nvw6gb-SkKpRSIA1NXfH.

1 Jamie Brownlow, Abigal Eberhart, and Kristen Berndt, “Emperor Wu Zetian,” Storymaps, last modified September 17, 2023, accessed March 21, 2025, https://storymaps.com/stories/e9979b19b6ad47b7a884762814f12a06.

2 Brownlow, Eberhart, and Berndt, “Emperor Wu Zetian,” Storymaps.

3 Brownlow, Eberhart, and Berndt, “Emperor Wu Zetian,” Storymaps.

4 “The Incredible Life of Wu Zetian: China’s Only Female Emperor.” History Skills. Accessed March 22, 2025. https://www.historyskills.com/classroom/year-7/wu-zetian/?srsltid=AfmBOoq6VZ52EnveaSeoYv-Tqzq1Kb-v2ri8nvw6gb-SkKpRSIA1NXfH.

5 Association for Asian Studies. Last modified 2015. Accessed March 8, 2025. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/wu-zhao-rulerof-tang-dynasty-china/.

6 Brownlow, Eberhart, and Berndt, “Emperor Wu Zetian,” Storymaps.

7 Association for Asian Studies. Last modified 2015. Accessed March 8, 2025.

8 Association for Asian Studies. Last modified 2015. Accessed March 8, 2025.

9 Association for Asian Studies. Last modified 2015. Accessed March 8, 2025.

Michael Mullane ’30

Miranda Walter ’30

Peter Irwin ’30

Reuben Whitman ’30

Brandon Treadaway ’30

Clarke Jackson ’30

Catherine Xin ’30

Lucy Ro ’30

American Spy Rings

Samiya Gupta ’29

During the American Revolution, the Continental Army faced immense challenges, from limited resources to a lack of experience in warfare. As they struggled against the well-equipped British forces, one unexpected advantage emerged—intelligence. Spy Rings during the American Revolution played a crucial role in obtaining much-needed intelligence for the Americans despite their taboo reputation. These rings ultimately led the Americans to victory.

The Americans faced severe challenges because they lacked military and financial resources. The British army was well-equipped, experienced, and had a strong naval presence. They were skilled in traditional European warfare, making it difficult for the relatively inexperienced and poorly supplied Continental Army to compete headto-head.1 The strong British army was a challenge for the smaller, less formally trained Americans. Instead, they relied on militias, groups of local men who would come together to fight when needed. These militias were often not as well-equipped or as disciplined as the British troops.2 One clear example of the American army’s inadequacy was during the harsh winter at Valley Forge in 1777-1778. The army faced severe shortages of food, clothing, and shelter. Many soldiers lacked proper uniforms and shoes, which led to frostbite and other illnesses. The army’s supply lines were stretched thin, and they struggled to get enough provisions to sustain the troops.3 The American army lacked everything, from experience to resources and supplies. Ultimately, the most important component they lacked was intelligence. George Washington, as commander of the Continental Army, needed detailed information about British troop movements, fortifications, and plans to avoid direct confrontations and to help plan surprise attacks. He needed this crucial information to get ahead and fight in this war. Nevertheless, the Americans didn’t have a plausible solution to get such intelligence which only made their fight for independence even more challenging and risky.

During the American Revolution, the use of spies was highly controversial, as their secretive activities and discreet tactics often blurred the lines between patriotism and treachery. At that time, espionage was often seen as dishonorable and deceitful. Many people believed that wars should be fought openly and honorably on the battlefield, not through secretive and underhanded methods.4 The citizens believed that if you fought a battle on the field, in person, it was honest and fair. You didn’t have to resort to tactics that could make it an unequal opportunity. Furthermore, spies were often viewed as traitors and criminals. If they were caught, they faced severe punishment, including execution.5 Spies were seen as untrustworthy and dishonorable. The treatment of spies showed the belief that spying was a serious betrayal of the core value system and challenged traditional ideas of warfare. One of the key events that led to the mistrust of spies was Benedict Arnold’s actions. Initially, Arnold was a respected general in the Continental Army and played a crucial role in several key battles, including the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and the Battle of Saratoga, which was a turning point in the war. Despite his contributions, Arnold felt he was not adequately recognized or rewarded for his efforts. This sense of underappreciation and mistreatment led him to secretly negotiate and work with the British.6 His betrayal from working with the Americans and then siding with the British reinforced the mistrust of spies and showed people the risks of espionage. Essentially, spies were viewed as “evil” or even “sinister” by many. At the time, the general public felt that relying on spies meant that the war was not being played on an honest level playing field. Rather than a straightforward battle between armies, it became a game of deceit and subterfuge. In addition, the fear of spies being embedded in people’s communities became

1 A.J Baime, “How George Washington Used Spies to Win the American Revolution,” History, A&E Television Networks, last modified October 18, 2024, accessed November 14, 2024,

2 A&E Television Networks, “The Culper Spy Ring - Facts, Code and Importance,” History, last modified June 23, 2023, accessed November 14, 2024, https:// www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/culper-spy-ring.

3 (John A. Nagy, Spies in the Continental Capital : Espionage across Pennsylvania during the American Revolution (Yardley, Pa.: Westholme, 2011), 74)

4 (John A. Nagy, Dr. Benjamin Church, Spy (Yardley: Westholme, 2014), 5452.)

5 (John A. Nagy, Spies in the Continental Capital : Espionage across Pennsylvania during the American Revolution (Yardley, Pa.: Westholme, 2011), 74)

6 ( “George Washington as Spymaster,” American History, https://online. infobase.com/HRC/LearningCenter/Details/2?articleId=369699.)

a constant subject in people’s lives. Civilians and soldiers became suspicious of their neighbors, colleagues, and even friends, fearing that anyone could be a secret agent of the enemy.

Washington devised a bold plan to increase the odds of the Continental Army’s victory over the British. As described earlier, the American army was subpar to the British in many facets of the war—not enough soldiers, few supplies, inexperience in warfare, and seemingly no strategy. So, the Americans established a spy ring. This decision marked a pivotal shift in the war, as the intelligence gathered by these spies became crucial in helping the American forces stay one step ahead of the British. It helped the tiny American army level the playing field against the gargantuan British army. The Culper Spy Ring was established in 1778 by Major Benjamin Tallmadge, under the orders of General George Washington. Its primary purpose was to gather intelligence on British troop movements and plans in New York City, which was a major British stronghold during the American Revolution.7 These spies would gather intelligence by observing British troop movements, listening to conversations, and even befriending British officers to gain their trust. They had informants who provided the spies with valuable information.8 Samuel Woodhull began to run the operations on Long Island and personally traveled back and forth to New York, collecting information and taking detailed notes on the British army. He would assess the reports and determine what useful information would be returned to General Washington.9 Once the Americans finally found a tactic to help them get ahead, they took it to full advantage, using every single piece of information they had to devise a strategic plan. They had found the one light of hope in the revolution - the use of espionage.

Spies during the American Revolution had a variety of tactics to gather and collect crucial information without being detected by the British, including complex networks of informants, invisible ink, and coded messages. Dead drops were a key strategy used by the Culper Spy Ring to exchange information without direct contact. This method involved leaving messages in secret, predetermined locations where another member of the ring could later retrieve them. This way, the risk of being caught while passing information directly was minimized. For example, one famous dead drop location was a hollowed-out tree known as the “Setauket Spy Tree” on Long Island. A spy would leave a message inside the tree and another member would come by later to pick it up. This method allowed them to maintain a high level of secrecy and avoid detection by the British.10 The Culper Spy Ring also devised another clever tactic by inventing a chemical solution that worked as invisible ink. Substances that faded when dry like lime juice, milk, and vinegar were used to write between the lines of ordinary-looking notes. These secret messages would only appear when heated, like over a candle. General Washington advised his agents to use this “sympathetic stain” because it made the messages less likely to be discovered and reassured those who had to carry them.11 Lastly, The Americans created a numerical code system. This system was designed to convert words, names, and even entire phrases into numbers, ensuring that their messages remained undecipherable to anyone without the corresponding codebook. The codebook itself was a crucial tool, containing a list of numbers paired with specific words or letters. For instance, “711” was the code for General George Washington, “727” for New York, and “745” for the British Army. Additionally, individual letters were also assigned numbers, enabling the spies to spell out words that were not directly listed in the codebook.12 They had many different ways to keep their discoveries secret and used it all to get full advantage over the British. Spies uncovered British plans and provided vital intelligence to the Continental Army that led to victories in key battles like Yorktown. The Culper Spy Ring achieved more than any other American or British

7 ( A.J Baime, “How George Washington Used Spies to Win the American Revolution,” History, A&E Television Networks, last modified October 18, 2024, accessed November 14, 2024,)

8 (Intel.Gov, “The Culper Spy Ring,” Intel.gov, accessed November 12, 2024, Culper Spy Ring.)

9 (A&E Television Networks, “The Culper Spy Ring - Facts, Code and Importance,” History, last modified June 23, 2023, accessed November 14, 2024, https:// www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/culper-spy-ring.)

10 . “George Washington as Spymaster,” American History, https://online. infobase.com/HRC/LearningCenter/Details/2?articleId=369699.

11 Alexander Rose, Washington’s Spies : the Story of America’s First Spy Ring (Place of publication not identified: Random House Publishing Group, 2007), [Page 54)

12 Victoria Williams, “Culper Spy Ring” [Culper Spy Ring], Mount Vernon. org, Mou