75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 75 ?art food land music books politics SPRING 2023

Mark your calendars for Moment’s 2023

Benefit & Awards Gala

Sunday, November 12 Washington, DC

Moment is having its first in-person gala since 2019–don’t miss this exciting evening celebrating Moment’s nearly 50 years of independent journalism!

For sponsorship information, email Johnna Raskin, jraskin@momentmag.com

C S C the Save Date

MOMENTMAG.COM

visit us follow us

FACEBOOK @momentmag

TWITTER @momentmagazine

INSTAGRAM @moment_mag

PINTEREST @momentmag

YOUTUBE @momentmag

LINKEDIN /company/moment-magazine

TIKTOK @momentmagazine

MASTODON mastodon.online/@momentmag

ask us

Can I read Moment online?

Yes. If you are not a subscriber and would like access, you can purchase a digital subscription online at momentmag.com/subscribe

How do I donate to support your work?

We could not produce this beautiful magazine and run the projects we do without loyal friends and supporters. Go to momentmag.com/donate or call 202-363-6422.

Whom do I contact to advertise in the magazine, newsletter or website?

Email Ellen Meltzer at emeltzer@momentmag. com or call 202-363-6422.

How do I submit a letter to the editor or pitch?

Email editor@momentmag.com. We will be in touch if your submission fits our editorial needs.

Does Moment have an online gift shop?

Recent past issues, books, tote bags and assorted gifts can be purchased at momentmag.com/shop

read with us

MOMENT MINUTE

Tuesdays & Thursdays

Moment’s editors share their thoughts on important stories and issues.

Sign up at momentmag.com/minute

JEWISH POLITICS & POWER

Alternating Mondays

Reporting and political analysis from a Jewish perspective.

Sign up at momentmag.com/jpp

ANTISEMITISM MONITOR

Regular updates & analysis

Tracking and analysis of antisemitic incidents worldwide.

Sign up at momentmag.com/asm

Moment Magazine is known for its award-winning journalism, first-rate cultural and literary criticism and signature “Big Questions”—all from an independent Jewish perspective. Founded by Leonard Fein and Elie Wiesel in 1975, it has been led by Nadine Epstein since 2004. Moment is published under the auspices of the nonprofit Center for Creative Change and is home to projects such as the Daniel Pearl Investigative Journalism Initiative, the Moment Magazine-Karma Foundation Short Fiction Contest, the Antisemitism Project and MomentLive! To learn more about Moment visit momentmag.com.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF & CEO Nadine Epstein

EDITOR Sarah Breger

DEPUTY EDITOR Jennifer Bardi

OPINION & BOOKS EDITOR Amy E. Schwartz

ARTS & ARTICLES EDITOR Diane M. Bolz

SPECIAL LITERARY CONTRIBUTOR Robert Siegel

SENIOR EDITORS Dan Freedman, Terry E. Grant, Diane Heiman, George E. Johnson z”l, Eileen Lavine, Wesley G. Pippert, Francie Weinman Schwartz, Laurence Wolff

DIGITAL EDITOR Noah Phillips

POETRY EDITOR Jody Bolz

ISRAEL EDITOR Eetta Prince-Gibson

EUROPE EDITOR Liam Hoare

FILM CRITIC Dina Gold

CRITIC-AT-LARGE Carlin Romano

DESIGN Erica Cash

CHIEF OF OPERATIONS Tanya George

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Debbie Sann

FINANCIAL MANAGER Jackie Leffyear

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING Ellen Meltzer

DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Pat Lewis

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT Johnna Miller Raskin

FACT CHECKER/DIGITAL PROJECTS Ross Bishton

CIRCULATION & MARKETING NPS Media Group

SPECIAL PROJECTS DIRECTOR Suzanne Borden

FELLOWS Jocelyn Flores, Jacob Forman, Molly Foster

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER Andrew Michaels

TRAVEL COORDINATOR Aviva Meyer

WEBSITE AllStar Tech Solutions

CONTRIBUTORS Marshall Breger, Geraldine Brooks, Max Brooks, Susan Coll, Marilyn Cooper, Marc Fisher, Glenn Frankel, Konstanty Gebert, Ari Goldman, Gershom Gorenberg, Dara Horn, Pam Janis, Michael Krasny, Clifford May, Ruby Namdar, Joan Nathan, Fania Oz-Salzberger, Mark I. Pinsky, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Sarah Posner, Naomi Ragen, Dan Raviv, Abraham D. Sofaer

MOMENT INSTITUTE FELLOWS Ira N. Forman, Nathan Guttman

MOMENT MAGAZINE ADVISORY BOARD

Michael Berenbaum, Albert Foer, Esther Safran Foer, Kathryn Gandal, Michael Gelman, Carol Brown Goldberg, Lloyd Goldman, Terry E. Grant, Phyllis Greenberger, Sharon Karmazin, Connie Krupin, Peter Lefkin, Andrew Mack, Judea Pearl, Josh Rolnick, Jean Bloch Rosensaft, Menachem Rosensaft, Elizabeth Scheuer, Joan Scheuer, Leonard Schuchman, Janice Shorenstein, Diane Troderman, Robert Wiener, Esther Wojcicki, Gwen Zuares

DANIEL PEARL INVESTIGATIVE

JOURNALISM INITIATIVE ADVISORY BOARD

Michael Abramowitz, Wolf Blitzer, Nadine Epstein, Linda Feldmann, Martin Fletcher, Glenn Frankel, Phyllis Greenberger, Scott Greenberger, Mary Hadar, Amy Kaslow, Bill Kovach, Charles Lewis, Sidney Offit, Clarence Page, Steven Roberts, Amy E. Schwartz, Robert Siegel, Paul Steiger, Lynn Sweet

Project Director Sarah Breger

Articles and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily represent the view of the Advisory Board or any member thereof or any particular board member, adviser, editor or staff member. Advertising in Moment does not necessarily imply editorial endorsement.

Volume 49, Number 2

Moment Magazine (ISSN 0099-0280) is published bi-monthly with a double issue (May/June and July/August) by the Center for Creative Change, a nonprofit corporation, 4115 Wisconsin Avenue NW, Suite LL10, Washington, DC 20016. Full subscription price is $59.70 per year in the United States and Canada, $153.67 elsewhere. Back issues may be available; please email editor@momentmag. com. Copyright ©2023, by Moment Magazine. Printed in the U.S.A. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, DC, and additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to Moment Magazine, P.O. Box 397, Lincolnshire, IL 60069 Order

How to subscribe to Moment

at momentmag.com/subscribe or call 800-214-5558 Canada and foreign subscriptions: 818-487-2006

Bulk subscriptions: 202-363-6422

moment

print or digital

SPRING 2023 2

27

SONGS TO BUILD A NATION

departments features

ESSAY

The Women Who Shaped Israel

A look at the state’s unsung heroines and the forces holding women—and Israel—back today.

by

Nadine Epstein, illustrations by Isaac Ben Aharon

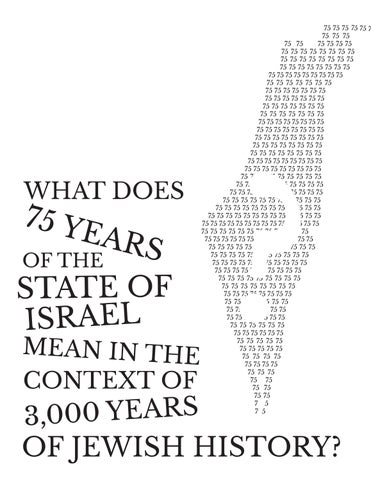

What does 75 years of the State of Israel mean in the context of 3,000 years of Jewish history?

48 62

A MOMENT BIG QUESTION 48

PLAYLIST

Songs to Build a Nation

Yossi Klein Halevi describes the songs that inspire Israelis—and made him fall in love with Israel. as told to Nadine Epstein

52 INTERVIEW

When Water = National Security

Environmentalist Gidon Bromberg builds bonds in the Middle East by expanding the definition of national security.

interview by Noah Phillips

A LITERARY TOUR OF ISRAEL

Traveling the Land, Book in Hand

Literature that illuminates Tel Aviv gardens, Jerusalem cafés, kibbutzim and more. by Omer Friedlander

4

From the Editor-in-Chief

Finding a balance between Israel and the diaspora by

Nadine Epstein

6 The Conversation

12 Opinions

Love for Israel can’t be unconditional by Letty Cottin Pogrebin

Life after ‘Never Again’ by Marshall Breger

Do Jews’ beliefs count on abortion?

Opinion interview with Dahlia Lithwick by Amy E. Schwartz

16 Moment Debate

Has the word Zionism outlived its usefulness?

Mira Sucharov vs. Derek Penslar interviews by Amy E. Schwartz

18

Ask the Rabbis

What does Israel reaching 75 mean in the context of 3,000 years of Jewish history?

21 Poem

“Fruit of the Land” by Yonatan Berg; translated by Joanna Chen

22 Jewish Word

Israel: What’s in a name? by Jacob Forman

24 Visual Moment

Sigalit Landau’s immersion in the Dead Sea by Diane M. Bolz

60 Talk of the Table

A feast to celebrate 75 years by Vered Guttman

62 Literary Moment

We Are Not One: A History of America’s Fight Over Israel; The Arc of a Covenant: The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People

review by Robert Siegel

The House of Love and Prayer and Other Stories

review by Erika Dreifus

72 Caption Contest

Cartoon by Ben Schwartz

73 Spice Box

PLUS! Moment’s Higher Learning Guide, a special advertising supplement Page 56

Konstanty Gebert, Susan Neiman, Dina Porat, Fania OzSalzberger, Simon Schama and others share their views. interviews by Moment staff 34 SPRING 2023 | MOMENT 3

spring issue 2023 27 62

from the editor-in-chief

principles on which Israeli civil society is built and has acted as the counterweight to the nationalist and theocratic tendencies now running rampant.

FINDING A BALANCE BETWEEN ISRAEL AND THE DIASPORA

When we started talking about an “Israel at 75” anniversary issue, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was out of office for the first time in 12 years. That brief interlude, during which the country cobbled together a centrist consensus, came to an end last fall when Netanyahu’s new far-right coalition took over. After years of simmering, the divisions within Israel have now boiled over and are testing its unity. We are seeing Israeli Jew vs. Israeli Jew, communities with sharply divergent visions of what Israel should be, each adamantly convinced they are right.

Those divisions may come down to this: those who want Israel to be a secular modern democratic nation—at least for Jews—with all its joys and flaws, and those who want a very different kind of state, one markedly less free and inclusive. It’s no secret why Israel’s far-right wing has made the country’s Supreme Court its sacrificial lamb. While the nation’s founders clearly envisioned Israel as a full-fledged parliamentary democracy, they failed to draw up a constitution or abolish the rabbinate, which was absorbed from the Ottoman legal system. Without a constitution on the books, it is the court that has established the

Tensions between the court and Israel’s legislative and executive branches are not new. But never has a ruling coalition come so dangerously close to destabilizing the balance of Israel’s separate branches of power. That the court has been branded left-wing is not wholly accurate. Its decisions fully satisfy neither right nor left, and it treads carefully, aware of the precariousness of its position. In 2020, for example, the court ruled that Netanyahu could form a new government despite being under indictment for corruption, to the dismay of his opponents. Let us hope that the court’s independence will not be curtailed. Democracies are messy, but in the long run those with independent judicial systems are less likely to slide into authoritarianism.

Even before the legislative offensive by the Netanyahu government, we had planned to ask historians and others a “Big Question” in search of some much-needed perspective. After considerable discussion we settled on “What does Israel reaching 75 mean in the context of 3,000 years of Jewish history?” Due to the crisis, the responses are less celebratory of this milestone than we originally imagined, and many are tinged with pain, even despair. We asked our rabbis the same question, and their answers are also telling.

One common refrain is the belief that the modern State of Israel is or should be the center of Jewish life and is the best hope for Jewish continuity. I am uncomfortable with this for several reasons. One is historical: Many of the great achievements of Judaism and Jewish culture have occurred in galut, exile, or to use the slightly less negative word, diaspora. These include the Babylonian Talmud; the classic commentaries of Rashi and Maimonides; Iberian mysticism; the Haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment in Western and Central Europe; Hasidism in Eastern Europe; and the great flourishing of new denominations in the United States, just to name a few.

BY NADINE EPSTEIN

The millennia-long tango between diaspora Jews and their surrounding cultures has brought us many gifts, though it has been punctuated by much suffering.

There is another reason for my discomfort, stemming from my role as editor-in-chief of a magazine founded nearly 50 years ago for the American Jews who didn’t pack up and move to Israel, but chose to stay and build a vibrant Jewish life here. Moment is part of the extraordinary thriving of Jewish life in the United States that has evolved largely unfettered by the kinds of religious strictures imposed by Israel’s rabbinical courts, although of course it has been affected by them, as well as by Israel’s wars and politics. I am always amazed at the fresh ways Judaism is expressed and practiced here. This phenomenal creativity is constantly transforming the American Jewish world, birthing new ideas and projects, theology, literature and art, all nourished by endless kibitzing and arguments.

This is why we should not be hesitant to say that both the diaspora and the ingathering enhance Jewish resiliency and creativity. Israel is an astonishing achievement of the Jewish people, a melting pot of cultures, a cauldron of creativity and a necessary home for Jews—but it is not the only home. The Jewish past and future demand both a homeland and a diaspora, and it is our ongoing responsibility to find a balance between them.

Building bridges between the diaspora and Israel is more than a matter of language. I know Israelis who speak English fluently who cannot understand America, or American Jews for that matter, and I know Americans who speak Hebrew who see only very narrow slivers of Israel. Travel, too, is not reliable: it depends on where you visit and who you meet. In this issue, we bridge the divide through the power of culture. One of our guides is Yossi Klein Halevi, who shares his favorite Israeli songs—a playlist that illuminates how Israelis think. Another guide is Omer Friedlander, who leads us on a tour of the land through its literature. In “Visual Moment,” by Arts & Articles Editor Diane M. Bolz, we see the

SPRING 2023 4 CAROL GUZY

Moment is a close-knit family, and we were shocked as we prepared to go to press with this issue when George E. Johnson, one of our senior editors, suddenly passed away. George, who came to Moment after a distinguished career as a lawyer and writer, became observant after serving as an intelligence officer in Vietnam as a young man. He was a wise and thoughtful colleague and a beloved presence in editorial meetings. We miss him greatly. To read his work and watch his MomentLive! program about his experiences in Vietnam, visit https:// momentmag.com/george-e-johnson.

We dedicate this issue to George. May his memory be a blessing.

Dead Sea through the inventive eyes of an artist concerned for its survival.

“Jewish Word” by Moment fellow Jacob Forman is a historical dive into how Israel got its name just a few hours before the state was declared. Digital Editor Noah Phillips introduces us to an environmentalist who has expanded the definition of national security. “Moment Debate” asks: Has the word Zionism outlived its usefulness? And since we couldn’t mark Israel’s 75th without inviting women to the party, I pay homage to some of Israel’s great ones. Finally, there’s food, perhaps the greatest human connector of all. Chef Vered Guttman has designed a menu drawn from the foods Israelis ate in 1948. It is a feast that fuses together the varied and rich cultures on which Israel was built.

As usual, we couldn’t fit everything into print—so sign up for Moment Minute at momentmag.com/newsletter to read about Israel’s top innovations, iconic objects and archaeological finds, as well as what may happen when Mahmoud Abbas is no longer on the scene. At momentmag.com/zoominars, watch an “Israel at 75 Book Series,” in which Opinion & Books Editor Amy E. Schwartz talks with Robert Alter about poet Yehuda Amichai and with Etgar Keret about short stories. We hope your spring will be enriched and inspired by these offerings and look forward to hearing your thoughts!

QSPRING 2023 | MOMENT 5 CELEBRATING 49 YEARS OF INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM EVERY DOLLAR YOU GIVE MOMENT HELPS POWER OUR JOURNALISM AND SUSTAIN OUR FUTURE • Contribute online at momentmag.com/donate • Send a check to Moment at 4115 Wisconsin Ave. NW, Suite LL10, Washington, DC 20016 • Give stocks, bonds or mutual funds through Fidelity Charitable or another fund • Remember Moment in your will or estate plan. Contact your financial adviser or Debbie Sann at dsann@momentmag.com or 202.363.6422 MOMENT IS A NON-PROFIT! ALL GIFTS ARE FULLY TAX-DEDUCTIBLE. WHEN YOU MAKE MOMENT PART OF YOUR ANNUAL GIVING YOU ARE SUPPORTING IN-DEPTH REPORTING ON ISSUES OF CONCERN TO AMERICAN JEWS PUBLIC PROGRAMMING THAT SHOWCASES THE LITERARY AND ARTISTIC TALENT IN THE JEWISH COMMUNITY INCLUSIVE PLATFORMS FOR CIVIL DISCOURSE PROJECTS THAT FIGHT ANTISEMITISM AWARD-WINNING JOURNALISM YOU CAN TRUST

TO JOIN THE

• RESPOND AT MOMENTMAG.COM

• TWEET @MOMENTMAGAZINE

• COMMENT ON FACEBOOK

• SEND A LETTER TO THE EDITOR TO EDITOR@MOMENTMAG.COM

Please include your hometown, state, email and phone number.

Moment reserves the right to edit letters for clarity and space.

the conversation

HATEFUL ENCOUNTERS NOT A “NOTHINGBURGER”

Reading Nadine Epstein’s “First Encounter of a Hateful Kind” (“From the Editor,” Winter 2023), I was struck and saddened that the cutting antisemitic remark, “Jew ’em down,” muttered by a man in rural Pennsylvania to Epstein’s father, is an incident that would go down, as she put it, “in the annals of hate...as a nothingburger.” Once antisemitism is pervasive, accepted and normalized in a culture, this creates fertile soil for further dehumanization and then normalization of greater degrees of dehumanization. This phenomenon within a society is clear in Daniel Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust and many other books. The slow drip, drip, drip of antisemitism that inevitably permeates an entire society starts with normalizing “nothingburgers.”

Chris Mayka Arlington, VA

ARE ALGORITHMS DANGEROUS?

THE MAGIC OF SEMICHA AN INEFFABLE LEANING

I love words and so was pleased to see yet another “Jewish Word” column (“Semicha—When a Rabbi Becomes a Rabbi,” Winter 2023). I found George Johnson’s article compelling and educational, especially the historical review of ordination through the generations. I appreciated how the article progressed from numerous historical examples of rabbis/teachers leaning on their successors to convey semicha to a current-day example in which a female rabbi was told to “lean back” into the hands of her teacher as she was being ordained. The feeling of pressure from her teacher’s hands as they transmitted the blessing caused her to shake, feeling that “something ineffable was happening.” Including this modern-day example was insightful, as how Moshe and Joshua might have felt during the laying of hands is not mentioned in the Torah. In a religion that focuses so much on rules

Andrew Michael’s first-person account “From Zero To Hate In Just a Tik And a Tok” (Winter 2023), describing how the TikTok algorithm can lead to Nazi content even for those not looking for it, generated a spirited response online. On the web forum Reddit, a debate ensued over the concept of radicalization described by the author. “This whole concept of algorithmic extremism is frankly nonsense,” a commentator with the username Party_Reception_4209 wrote. “What the algorithms do is optimize for engagement. If you constantly signal to the platform that you want a certain kind of content then you’ll get it. No platform serves up extremism when all the user ordered was memes of hot moms dancing in their kitchen, which is all I ever see on the app.” Disagreeing, another commentator (username: Vecrin), explained that it is the ability of algorithms to shift a user’s recommended content over time that makes them insidious. “Let’s say you’re a random teenager who likes gaming. TikTok feeds you amazing Fortnite clips. All good. But then it starts to push this guy who starts making fun of some ‘crazy’ woman who is ‘ruining gaming.’” Over time, Vecrin noted, a user’s feed will continue to develop. “You happen upon a TikTok talking about how feminists are trying to ruin culture...Pretty soon you’re listening to people complain about how women aren’t having relationships with guys like you anymore. Feminism has corrupted them…So you start to listen to that type of content more. It’s fun. They’re just joking around. What’s the harm in listening to a few slurs drop every once in a while?...So you continue to listen and think, huh, maybe they’re right about this stuff.” They warn, “It starts with a normal, fun subject (like gaming) and slowly pushes you down the rabbit hole.”

MANY OF US HAVE BEEN WONDERING WHY ANTISEMITISM SEEMS TO BE GROWING BY LEAPS AND BOUNDS AMONG MANY WHO ARE NOT THE USUAL SUSPECTS.

“

CONVERSATION:

SPRING 2023 6

and obligations, it was refreshing to read about human touch as reinforcement of the transfer of authority.

Elaine Amir Rockville, MD

INSIDE TIKTOK A MODERN HELL

Jennifer Bardi’s chilling article about antisemitism on TikTok (“The Good, the Bad and the Algorithm,” Winter 2023) unfortunately reinforced a grim conclusion that I’ve long harbored about social media in general. Bardi’s suggestions about how to thwart antisemitic deportment on TikTok reflect the assessments of an intelligent, civilized individual. However, I’ve concluded that bigots and their ilk, having found cybermegaphones that allow them, literally, to reach practically everyone, will never be purged from the internet. Dante’s Hell was a place of punishment; the web is a very modern kind of hell, a ghastly theater of the depraved for antisemites, racists, etc. And the future? I dread what will happen when the bigots are able to manipulate AI—or the other way around.

Howard Schneider New York, NY

A PERFECT STORM

I have close to zero familiarity with TikTok (to me it’s just cool dances and fun stuff), but your article describes a really appalling development. Many of us have been wondering why antisemitism seems to be growing by leaps and bounds, and among many who are not “the usual suspects.” It seems to be a perfect storm between the advent of this technology with its ingenious algorithms and the vanishing generation of people who experienced the Holocaust firsthand or knew those who did. For a lovely interlude in the second half of the 20th century, antisemitism seemed to be on the wane, and young people, Jewish or other, were oblivious to what it was like to experience it. Thank you for your coverage, and please keep presenting information like this so we know what we’re up against, even if we don’t use TikTok.

Joan Reisman New York, NY

There are many ways to support Israel and its people, but none is more transformative than a gift to Magen David Adom, Israel’s paramedic and Red Cross service. Your gift to MDA isn’t just changing lives — it’s literally saving them — providing critical care and hospital transport for everyone from victims of heart attacks to casualties of rocket attacks. Support Magen David Adom by donating

SPRING 2023 | MOMENT 7 No

charitable gift has a greater impact on the lives of Israelis.

today at afmda.org/give or call 866.632.2763. afmda.org/give

VISUAL MOMENT

FOUR WINTERS, TWO THUMBS UP

I just read the article about the film Four Winters (“Tales of Rifles and Resistance” Winter 2023) and I thought it was terrific—detailed and evocative. Great choices were made about which elements in the film to highlight, and there were vivid quotes from the film’s director. I also loved how the photos were used in the article.

All the attention that Four Winters is receiving means the partisans’ stories will be heard more widely. ABC News, for instance, did a piece about the film in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day. That sort of coverage as well as Moment’s article and all the other media attention is really useful in spreading the word about Jewish bravery and resistance during WWII.

Emily Mandelstam

MOMENTLIVE!

ANOTHER GREAT PROGRAM

Thank you for the recent program “The Educational Legacy of Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington.” I was aware of the Rosenwald schools and heard several interviews with Andrew Feiler when his book on the topic came out. My most enthusiastic praise is for the ease of registering and joining on my computer despite having registered on my phone. Thank you for a stellar program and for a very easy experience to join and enjoy it.

Louise Eighmie Turner

Louise Eighmie Turner

Atlanta, GA

Editor’s note: All programs are available at momentmag.com/zoominars

MOMENT DEBATE POLL

In the previous issue, Moment asked if changing the Law of Return will harm Israel-diaspora relations. We asked our Twitter followers to weigh in. The majority answered yes.

New York, NY King David, Jerusalem | Dan Jerusalem | Dan Panorama Jerusalem | Dan Boutique Jerusalem | Dan Eilat Dan Panorama Eilat | Neptune Eilat | Dan Tel Aviv | Dan Panorama Tel Aviv | Link hotel & hub TLV Dan Accadia Resort | Dan Caesarea Resort | Dan Carmel, Haifa | Mirabelle Plaza, Haifa | Dan Panorama Haifa Ruth Safed | Mary’s Well Nazareth | The Den, Bengaluru www.danhotels.com Jerusalem iconic King David and Tel Aviv’s first luxury hotel, The Dan Tel Aviv - Israel’s members of the “Leading Hotels of the World” a prestigious collection of exclusive hotels that offer unsurpassed splendour . KING DAVID JERUSLAEM. DAN TEL AVIV. Proudly part of the “Leading Hotels of the World” JEWISH REVIEW BOOKS JRB is celebrating its 13th year! Jewish Culture. Cover to Cover. From fiction to philosophy, and from ancient history to the latest show (or Supreme Court decision), the JRB brings you great writers who review the Jewish world with deep knowledge and ready wit. For special anniversary rates please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or call 1-877-753-0337 or scan code. SPRING 2023 | MOMENT 11

COTTIN POGREBIN

ISRAEL, WE’VE GOT TO TALK

Time to put some conditions on our tortured relationship.

In Hebrew, ahavat Yisrael means “love of one’s fellow Jews.” But for many of the millions of Jews who define their Judaism in a nationalist as well as, or rather than, a religious framework, ahavat Yisrael has come to mean love of the Jewish state.

For the past 75 years, the relationship between the average Jewish American and the State of Israel has flourished in large part because of a love pact of our own making: In return for helping us feel safe, strong and proud, we agreed to give Israel unconditional love. This tacit covenant has impelled us to do amazing things: defend every Israeli government regardless of party, policies or politics; lobby our legislators to give Israel advanced weapons and vast amounts of foreign aid; raise huge sums of money for its military, cultural and social institutions; and vigorously promote its entrepreneurship, ingenuity, technology and tourism.

All this time, our love of Israel has remained steadfast regardless of whether it is returned in kind, or in kindness. We’ve kept up our end of the pact, even when some Israeli leaders have humiliated our leaders (think Netanyahu making an end run around Obama to address Congress).

The romance kept its youthful blush, even after some Israeli rabbis blithely dissed some of our rabbis, delegitimizing the conversions of Reform, Conservative and several Modern Orthodox religious courts, ridiculing our denominational Judaism and restricting our prayer practices at the Western Wall, as if the ancient site belonged to the Orthodox rabbinate, not to the Jewish people.

So many American Jews keep saying “I love Israel,” even when the object of our love violates international law, as it does daily by encouraging settlement creep and permitting de facto annexation in the West Bank. Or when it routinely violates

the human rights and dignity of millions of Palestinians who live under constant scrutiny by the IDF and Israeli police and are subject to military, not civilian, law. My own eyes have seen the results of housing demolitions, evictions, preventive detention, confiscation of property, arrests of small children, gratuitous insults and casual dehumanization of Palestinians at checkpoints.

Most surprising to me, the love pact held firm even when the Knesset passed the 2018 Nation-State Law, which expressly denied equal rights to its Arab citizens and other minorities and flagrantly privileged Jews. Had our government taken equivalent discriminatory steps against U.S. minority groups, doubtless most American Jews would have catapulted themselves and their communal organizations into action. But when festering blemishes broke out on the face of “the only democracy in the Middle East,” our top spokespersons trotted out the concealer. Shoulder to shoulder with conservative evangelicals, most Jews continued to press their hyperbolic claim that Israel “shares America’s values.”

But at long last, we’re discovering that love has its limits. Since Bibi’s coalition of fascist, racist, ultranationalist, Orthodoxdominated far-right ministers assumed power, not only have hundreds of thousands of Israelis taken to the streets, but a number of U.S. machers—prominent mainstream Jews—have broken ranks and put their distress on the record in no uncertain terms.

Rabbi Eric Yoffie, president emeritus of the Union for Reform Judaism, said he felt morally obligated to criticize Israel’s elected rulers “for the first time in my life.” The revered former ADL chief Abe Foxman told The Jerusalem Post, “If Israel ceases to be an open democracy, I won’t be able to support it.”

In a video that went viral, Sharon Brous, the charismatic rabbi of the IKAR community in Los Angeles, delivered a passionate

sermon on the urgency and the agony of not loving what Israel has become.

Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky of Manhattan’s Ansche Chesed revealed that he and his congregation would no longer recite the “Prayer for the Welfare of the State and Government of Israel,” which has been said on Shabbat and holidays in Conservative synagogues since the founding of the state.

Many ordinary Jews, too, have been struggling with pangs of conscience. Since September, I’ve given more than 60 talks to Jewish groups all over the country during which I heard Jews whisper that, for the first time in their lives, they’re ashamed of Israel. For some, it’s a shanda fur die goyim (an embarrassing act by Jews witnessed by non-Jews) that the Jewish state is being compared to Hungary, Belarus and the Philippines and its prime minister likened to their authoritarian leaders. Others admit they were embarrassed as Jews when settlers were filmed torching Palestinian villages, that the scenes awakened images seared into their memories of a time when we Jews were the victims of violent mobs. People said they couldn’t believe the Israel they love could possibly have come to this.

Also freshly motivated, a majority of the 27 Jewish members of the U.S. House of Representatives, including Jerrold Nadler, Brad Schneider, Jan Schakowsky and Debbie Wasserman Schultz—all well-known “lovers of Israel”—signed a highly unusual letter to Netanyahu, Israeli President Isaac Herzog and opposition leader Yair Lapid, registering “profound concern about proposed changes to

OPINION

LETTY

perspectives SPRING 2023 12

“

WE’RE DISCOVERING THAT LOVE HAS ITS LIMITS.

The Music & People of

POLAND & PRAGUE

Israel’s governing institutions and legal system that we fear could undermine Israeli democracy and the civil rights and religious freedoms it protects.”

Scattered push came to unified shove on March 12 when representatives of the center-right Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations, including the American Jewish Committee, AIPAC and the Anti-Defamation League (along with many progressive Jewish groups and the U.S. State Department) actually boycotted Israel Bonds’ Washington, DC fundraiser. This unprecedented act was precipitated by the group’s extending a speaking invitation to Israel’s finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, a rabble-rousing hatemonger who has identified himself as a “fascist homophobe,” called gay pride parades “worse than bestiality” and reacted to the settlers’ pogrom in an Arab village by saying the entire town “needs to be wiped out” (a war crime in any language).

I’m grateful to those notables who are

using their platforms, pulpits and personal prestige to come to the defense of Israeli democracy. Yet the full benefits of the democracy they want to save have, in fact, only been enjoyed by Jews. So I also can’t help feeling ashamed that it took a threat to dismantle Jewish rights and Jewish freedoms to burst the balloon of romantic delusion.

It shouldn’t have taken a settler pogrom, or a clear and present threat to freedoms previously taken for granted by Jews, to rile up our leaders.

Love of Israel must be conditional. We can’t support, reward or enable the Jewish state to do whatever it chooses, without taking some responsibility when its choice is to trample on the rights and freedoms of other human beings. Here’s what conditional love looks like:

• We don’t quit lobbying for the Jewish state. We lobby for Israel and Israelis, not their current government, which seems hell-bent on dismantling the founding freedoms granted to its people in its own

majestic Declaration of Independence.

• We don’t stop giving money. We stop giving undirected money to just any “pro-Israel” organization. We target our funds to entities working to secure an array of democratic institutions in Israel (free speech, press, minority rights and an independent judiciary).

• We don’t stop visiting Israel. We make sure our tour itineraries expose us to the whole truth about the land we love, not just its tech miracles and blooming deserts.

You’ve heard the expression “Friends don’t let friends drive drunk.” If someone we love is steering their life off a cliff, we try to stop them, redirect them, talk sense into them. It doesn’t mean we take away the car, it means we take away the car keys. We don’t want Israel to cease to exist. We just want its government to stop eroding the very foundations of its existence.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin’s most recent book is Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy.

O ctober 14-25, 2023

Featuring the SOARING VOICES of the American Conference of Cantors Full Itinerary, Registration & More: secure.ayelet.com/ACC2023.aspx

M ore JEWISH HERITAGE Adventures CROATIA PRIVATE YACHT CRUISE OCTOBER 13-21, 2023

MOROCCO LED BY BILL CARTIFF NOVEMBER 1-12, 2023

CUBA PROF. STEPHEN BERK DECEMBER 3-10, 2023

ayelet@ayelet.com SPRING 2023 | MOMENT 13

GREECE PROF. NATAN MEIR JUNE 17-28, 2024

800-237-1517 / 518-783-6001 | www.ayelet.com |

OPINION MARSHALL BREGER

BEYOND ‘NEVER AGAIN’

In the wake of war crimes, balancing collective memory and collective amnesia.

We have probably seen the end of the German trials of Nazi perpetrators. In the most recent one, in 2022, Irmgard Furchner, 97, a secretary to the camp commander at Stutthof, was found guilty and given a suspended sentence. In 2015 Oskar Gröning, 95, a desk officer at Auschwitz, was sentenced to two years in prison, but he died during the appeals process. How do we narrate the Shoah when the living consciousness of the Holocaust is gone? The natural human instinct for justice has been felled by time. What is left is the demand for accountability, transparency, memory.

Jews, of course, have a special focus on memory. One of the greatest Jewish historians of our age, Yosef Yerushalmi, wrote that “only in Israel and nowhere else is the injunction to remember felt as a religious imperative.” We are sternly commanded in Deuteronomy, “Remember that you were once slaves in Egypt.”

There are two functions of memory. One is to ensure that the horrors are not forgotten—that the truth will out. In the Warsaw Ghetto, Emanuel Ringelblum and a group using the code name Oyneg Shabbes collected documentation of the Nazi atrocities the ghetto underwent knowing he and his community were doomed. The documentation, buried underground in metal boxes and milk cans, was his group’s answer to the question “Who will write our history?”

These issues are not limited to the Jewish community. The invasion of Ukraine has focused international attention on the issue of war crimes trials. Ukraine has already held such trials against Russian soldiers for crimes in Bucha and elsewhere. The International Criminal Court intends to open war crimes cases against Russians, and the establishment of a separate international court for Ukrainian atrocities is being discussed.

Supposedly, knowledge of such acts aids future deterrence. As George Santayana iconically stated, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” On this view, memory is a prophylactic that can avert future horrors, as in the mantra “Never again.” But there is scant empirical evidence for that assertion. As David Rieff has written, “After Sarajevo, after Srebrenica, we now know what ‘Never again!’ means. Never again simply means never again will Germans kill Jews in Europe in the 1940s.”

“Never again” may be treated as a warning—we must remember so that Jews (read: Israel) will be strong enough not to allow themselves to be destroyed when, in the Haggadah’s words, “in every generation they rise up to slaughter us.” Collective memory can reinforce communal solidarity. But it is also a social construct—in the words of French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, “a reconstruction of the past in light of the present.” The annual trip that takes Israeli high school youth to Poland is focused on the death camps and what would happen if Jews again should become weak. Some would argue that the trip serves not only to memorialize the Shoah but to reinforce the Israeli right’s skepticism of rapprochement with the Palestinians.

However, collective memory can also increase collective trauma. A cult of memory can make reconciliation near impossible. The Jewish quarter of Hebron has transformed itself into a museum to the massacre of Jews by Arabs in 1929. The birthday of every child murdered is commemorated, as is the place where every Jewish inhabitant was slaughtered. In 1992, journalists covering the siege of Srebrenica recounted that when they asked Serbs why they were fighting, they simply answered “1453”—the year the Ottomans conquered Christian Constantinople. When I was in Kosovo after the 1995 Dayton

Accords, I asked some Serbs the same question. Their answer was “1389”—the date of a famous battle where the Serbs had faced off with the Ottomans.

All this suggests a certain argument for forgetting. Collective amnesia may allow not just a society but its citizens to rebuild their lives. Rieff suggests that the price of remembering “at least in certain social and historical conjunctures” might be too high. It is no accident that there was so little discussion of the Holocaust even in Israel in the early years of the Jewish state. In fact, relatively few “survivor memoirs” were published until the late 20th century. Some years ago the Rwandan ambassador to the United States, speaking of the murder of one million, told me that Rwandans had no choice but to forget because they have to live cheek by jowl.

For years, the Jewish community insisted on the uniqueness of the Shoah and denied the very notion of comparative Holocaust studies. But unique or not, the multigenerational experience of remembering atrocities and rebuilding identities and communities has generated not only valuable scholarship and reflection but legal and civic experience in dealing with the aftermath. That experience will be more than relevant in the years to come as Ukrainians in the wake of the conflict with Russia work their way through the trauma of war crimes, accountability and memory.

Marshall Breger is a professor of law at Catholic University.

SPRING 2023 14

A CULT OF MEMORY CAN MAKE RECONCILIATION NEAR IMPOSSIBLE.

“

DO YOU REALLY WANT THAT ABORTION?

Courts have no business deciding whether Jewish plaintiffs are sincere.

Deep-red Indiana isn’t a state you’d ordinarily look to as the leading edge of post-Roe v. Wade abortion politics. Now, though, a case in the Indiana state courts could have consequences not just for abortion rights but for religious liberty. A group called Hoosier Jews for Choice and several women, including three Jews and one Muslim, sued to block the state’s near-total abortion ban on the basis that it infringed on their religious liberty. A judge allowed the suit to go forward under the state’s robust Religious Freedom Restoration Act, or RFRA (signed in 2015 by then-governor Mike Pence). Having progressed furthest of the multiple religious-freedom challenges to abortion bans being brought by Jews and others around the country, the Indiana case has provoked the sharpest backlash. The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a law firm that has represented many religious conservatives, filed a brief asserting in so many words that the Jewish plaintiffs were insincere in their religious convictions.

Dahlia Lithwick, Slate’s legal affairs correspondent and a court watcher, calls the Becket brief’s argument “astonishing in its frank and candid willingness to impugn the religious beliefs of Jews and other religious minorities.” Is this the shape that future church-state disputes could take once liberals, not just conservatives, assert that their religious convictions are entitled to deference? Lithwick spoke with Moment Opinion Editor Amy E. Schwartz.

Was this how you anticipated the post-Roe landscape would look? No!

To have the Becket Fund call into question the religious sincerity of Jewish and Muslim plaintiffs was shocking. It crosses so many lines on how we treat other faiths. There were many ways to oppose the plaintiffs’ case without inviting courts to engage in this really diabolical project of deciding who’s faking their religion and who isn’t. They could have stopped at the argument that the state has a compelling

interest in fetal life. I’m not suggesting courts never have to weigh issues of religious sincerity. Under RFRA they often must determine whether something is a real religious objection. But not like this. After another recent case, Becket issued a celebratory press release saying the result showed that “Courts can’t decide what it means to be Catholic—only the Church can do that.” But in this case they’re essentially saying, “We invite the courts to say what Judaism is and is not.”

Last summer, South Texas College of Law professor Josh Blackman wrote a piece with some “tentative thoughts” questioning the religious sincerity of non-Orthodox Jews generally. He argued that unless you follow all of halacha, you’re picking and choosing, and therefore you have no meaningful religious obligations. In other words, Reform and Conservative Jews don’t need to be taken seriously as religious objectors. University of Virginia Law Professor Micah Schwartzman and I responded at the time, writing how dangerous and deeply disturbing that argument was and how it was anathema to First Amendment religious provisions. Blackman’s not even describing the law correctly; under RFRA, you don’t have to break an affirmative religious command to have your religious exercise burdened; it’s enough to say, “This is my religious conviction.” And it’s really important to head off at the pass this notion that Reform and Conservative Jews just make it up as they go along.

There’s a very good brief in the Indiana case recounting the history of everything the Indiana Jewish community was doing pre-Roe, and also afterwards, to support women who needed abortion care. Nobody could suggest this is anything but long-standing Jewish conduct. There was an abortion underground, there was organizing, there were sermons explicitly supporting abortion and

birth control, rabbis taking the position that children need to be wanted.

How will these claims of insincerity play at the Supreme Court? It’s possible that Becket miscalculated: The court is probably reluctant to take a case that’s cast as “the Jews and the Muslims are lying liars.” The court wants to hold itself out as being open to all comers religiously. Still, in the Roberts court, some religions seem to win more. Whether it’s Hobby Lobby, where religious employers get an exemption from the contraception mandate, or the COVID cases, where the court overruled public health regulations that capped the size of religious gatherings, it’s been “Yes, yes, yes.” People who seek religious exemptions from providing abortions prevail far more frequently than people saying, “My religion prohibits me from waiting to help until someone is bleeding out on the table.”

Does this case uniquely impact Jews? Not at all. One plaintiff is Muslim. A lot of faiths require that the fetus not be privileged over the life of the mother. It’s really sad that we’re learning this only in the wake of Dobbs. Faith communities were absolutely central to liberalizing abortion laws in the 1960s and 1970s, but after Roe, they fell silent. And then the Moral Majority came in and claimed that only one side, the evangelical and Catholic groups, had skin in the game. The groups that had worked so tirelessly for decades stopped paying attention, and they stopped grounding their support for abortion rights in morality and faith.

What other cases should people be watching closely? There are abortion-and-religious-liberty cases filed in Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky and Texas, among others. Each one is a harbinger of where religious liberty is going.

OPINION INTERVIEW

DAHLIA LITHWICK

SPRING 2023 | MOMENT 15

moment debate

YES

Has the word Zionism outlived its usefulness? Yes. Because different people use it in so many different ways, we end up talking past each other, especially in conversations between those who say they support Zionism and those who say they oppose it. Supporters—and here I’m specifically talking about people with a generally liberal worldview—tend to think the term refers to either belief in a Jewish and democratic state, or a sense of personal and communal attachment to Israel. Opponents tend to focus on Zionism as a state-led ideology—because at the moment Zionism doesn’t exist apart from the single state, Israel, whose policies flow from it—and say that whatever those policies are, they all have at their root the inequality and the privileging of some people and groups over others, whether it’s Jews over non-Jews or citizens of the state over Palestinians under occupation.

I recently conducted a survey of American Jews, and unsurprisingly, a strong majority said they were Zionist. Then I posed a series of definitions, asking whether they were Zionist according to definitions A, B or C. When Zionism was defined as supporting the existence of a Jewish and democratic state, more than 70 percent said they were Zionists. Likewise when Zionism was defined as a sense of attachment to Israel. But when the definition was “Zionism means a set of policies that flow from a particular governing structure where Jews are inherently privileged over non-Jews,” only 10 percent said yes. That tells me the word’s not very useful. It’s better to talk about emotions and values directly.

How did the term collect so much baggage? It comes partly from looking at ideologies through the lens of who

wins and who loses. With Zionism, the winners were clearly the Jews, who succeeded in creating a state. The losers were clearly the Palestinians, actively displaced by Jews’ creation of that state. Awareness has grown about the cost of certain state-building practices on some marginalized populations. Even in my field, international relations, people are teaching and thinking more than they did 20 years ago about decolonization and racism.

Being a Zionist once meant you were committed to moving to Israel and making your life there. Now Jews feel more secure in North America—the rise of antisemitism notwithstanding—so Zionism tends to be more of an arms-length political and emotional allegiance. I think that’s another reason the term has become so contested. Now it’s a set of political beliefs, and all political beliefs are and should be subject to debate and critique.

Does using the word Zionist imply that the existence of the state is still in question? If you think of Zionism as the push to create a Jewish state, that’s right. But Zionism is not only a historical political program, it’s also a set of contemporary state-led ideologies and policies. The creation of Israel is a settled matter, but we should always be thinking of how its policies affect individuals and groups.

Then there’s the argument that opposing Zionism is opposing not just the state but the Jewish people—in other words, that anti-Zionism is antisemitism. I don’t agree with that equation, but it has to be heard and dealt with. And to debate it, we have to define our terms.

What other words could we use instead? Why not say pro-Israel? I

wouldn’t use any of those words. We should talk about policies that advance or impair dignity, equality, justice and freedom: What has Israel done, what can it or does it do, to advance those values? And where does Israel need to be held to account? That approach also avoids holding Israel to a double standard, because those are questions we should be asking everywhere in the world. Separately, we could talk about attachment to Israel. Am I a Zionist? If I’m attached to the people and the language of Israel, and want to make it a more just place for everyone who calls it home, maybe someone who defines Zionism as attachment would see me as a Zionist. But someone who sees Zionism as a matter of policies wouldn’t, because of the policies I argue for. If someone wants to ask me if I’m attached to Israel, ask me that. It doesn’t necessarily mean I support the policies of inequality that Israel advances. If I simply said I’m a Zionist, or an anti-Zionist, no one would know where I stood on emotions or values. If we eschew the term Zionism, then we can advance the conversation.

Can the word be reclaimed? I don’t think so. It’s not like reclaiming a negative word like “queer.” That was binary: You could use it in a positive way to take the sting out of it. But Zionism, while it’s sometimes a slur, is already being used in too many fundamentally different ways. There’s too much mixing and matching, when what we really need is clarity.

Mira Sucharov is a professor of political science at Carleton University, the author most recently of Borders and Belonging: A Memoir, and coeditor of Social Justice and Israel/Palestine: Foundational and Contemporary Debates.

“

If we eschew the term Zionism, then we can advance the conversation.

MIRA SUCHAROV

SPRING 2023 16

Has the word Zionism outlived its usefulness?

Has the word Zionism outlived its usefulness? No. I can understand why people might say so, but Zionism describes a series of beliefs, feelings and needs that transcend political reality. In that sense, it’s like any word that ends in “ism”—liberalism, conservatism, progressivism. These are bundles of ideas and feelings that survive across time, even if their meanings change. For example, to be a liberal today is very different from 150 years ago, but we still use the word.

How did the term collect so much baggage? On the left, the word Zionism has come to mean a particular approach to Jewish nationhood tainted with exclusion, domination and racism. In universities today it’s often a pejorative. I think the connotations are inaccurate: As Amos Oz said, Zionism is a last name that has many first names, religious Zionism, Labor Zionism, spiritual Zionism, Revisionist Zionism and more. But it’s not just 21st-century progressives who’ve contributed to those connotations. A lot of Arab Muslim countries have not wanted to call Israel by name, so they refer to “the Zionist entity.” Iran still does. In the former Soviet Union, “Zionism” was a crime. Before that, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion—the most famous antisemitic tract in history—used the word “Zion” to connote a global conspiracy of Jews. It’s been used in slogans attributing negative qualities to Israel since the 1960s— Zionism as racism, Zionism as apartheid. But I don’t think throwing out the word would get rid of these underlying negative feelings.

Some people who associate Zionism with ethnocentrism, narrowness and racism don’t want anything to do with it, and it’s true that there are forms of Zionism

that are all those things—the current Israeli government embodies those aspects. But there are other types of Zionism that are more progressive and inclusive. When my daughter was in college, she would say, “I’m Zionish.” I hear something like that from a lot of my Jewish students, who feel connected to Israel but feel that “Zionism” has acquired too much negative meaning. And of course some Jews and even Israelis consider themselves anti-Zionist because their desire for equity and justice between Jews and Palestinians is so fundamental to their identity. But to be a Jewish anti-Zionist is to be engaged with Israel in a deeply personal way—which, in my definition, is also to be a Zionist. It means you care, even if you don’t want to admit it.

Does using the word Zionist imply the existence of the state is still in question? It’s true that if you define Zionism as the movement to create a Jewish state, that movement ended in 1948. Right-wing figures in the 1940s coined the term “post-Zionism” to describe just that. The idea reappeared, this time from the left, in the 1990s when the Oslo peace process appeared to herald the onset of a “normal” Israel, with peace and diplomatic ties with the Arab world, when it seemed that Zionism as a mobilizing movement would no longer be wise or necessary.

But Zionism was always about much more than simply the creation of the Jewish state. It was also about a profound sense of Jewish nationhood and the cultivation of that nationhood through the connection to Israel as a spiritual and cultural center. That sense of connection continues. Even the fact that so many Jews in the diaspora are upset with Israel at the moment means they care about it.

Some in Israel think that Zionism no longer applies because Israel has no connection with the diaspora. But in fact, both right-wing and left-wing diaspora Jews are constantly involved in Israeli politics.

What other words could we use instead? Why not say pro-Israel? We could call the ideology Israelism, but that assumes that we’re only talking about the State of Israel, and I don’t think that’s true. It’s about something more—global Jewish solidarity, interest in Hebrew culture, the religious heritage of the Jewish people. “Israelism” suggests we venerate or worship a country. Zionism’s a better choice—it’s more abstract and open-ended.

Can the word be reclaimed? Yes—it needs to be rescued from the anti-Zionist left and also from the illiberal, populist and hateful streams within contemporary Israel, shared by no small segment of American Jewry. We can’t stop them from calling themselves Zionist, but other Jews with other ideas can keep using it, too. There are many different ways one can identify with the state of Israel and the Jewish people. There are people in academia who say they are non-Zionist, anti-Zionist, post-Zionist—but they’re still using the word Zionist as a reference point. I don’t want to force anybody into a category; if they don’t want to use it, that’s their business. But the idea of Zionism is still useful, even if I don’t define it the way Benjamin Netanyahu does.

Derek Penslar is a comparative historian and a professor of Jewish history at Harvard University. He is the author or editor of a dozen books, including the forthcoming Zionism: An Emotional State.

NO

“

Zionism was always about much more than simply the creation of the Jewish state.

DEREK PENSLAR

SPRING 2023 | MOMENT 17

ask the rabbis

What does Israel reaching 75 mean in the context of 3,000 years of Jewish history?

humanist

How is it even possible to judge the meaning of Israel against the very long history of the Jewish people and its Hebrew-Israelite-Judean predecessors? In the context of what necessitated a Jewish state, the State of Israel provided a true sanctuary, gathering Jews from the “four corners” of the world. Our ancient language was revived and our calendar and customs became culturally normative. Most significantly, Israel placed the Jewish people back on the stage of history, a Jewish nation determining its own destiny. But this also poses its biggest challenge.

independent

For one thing, 75 years is how old our ancestor Abraham was when God called him to journey to the land that would one day be called Israel (Genesis 12:4). Thus began not our 3,000- but our 4,000-year history. In that context, 75 years demonstrates beyond question the miraculous nature of the Jew and the authenticity of our sacred writ. Not once did we relinquish our sense of self-value, neither as individuals nor as a people, even though year after year, decade after decade, century after century, there appeared no sign of the ancient promise heralded by our prophets. Nonetheless, every Shabbat we celebrated our liberation, even while loathed and oppressed by the world

around us, subject to annual Easter pogroms and frequent expulsions. And every Passover—though remaining as exiled from our homeland as the Passover before—we concluded our seder with the song of audacity, leshanah ha’ba’ah b’Yerushalayim, “Next Year in Jerusalem,” until one day, 75 years ago, that is precisely where we found ourselves. This is the empowerment threading through our lengthy history, woven by the tradition that kept us afloat through the tsunamis of the past to this very moment. It is knowing deep inside that there is nothing we cannot face when we remember that God is facing us

Rabbi Gershon Winkler Walking Stick Foundation Monument, CO

To run a nation is to have power. In Israel’s case this power includes ruling over several million non-Jews. And because Jews in Israel hail from different Jewish subcultures and religious backgrounds, this power also generates nonstop infighting over the Jewish and democratic nature of the state. Add Israel’s relationship with diaspora Jewry—with its own stake in the state’s definition of Jewish authenticity—and the project becomes even harder. As the first modern attempt at a Jewish state, Israel is certainly unique. What it will ultimately mean in the context of 3,000 years of history remains to be judged by future generations.

Rabbi Jeffrey Falick

Congregation for Humanistic Judaism of Metro Detroit

Farmington Hills, MI

renewal

A mere three generations! So much built and accomplished, so many challenges met and overcome. Having an independent Jewish state for 75 years—it’s but the blink of an eye in the context of our three millennia of history. And yet, à la Benjamin

SPRING 2023 18

THE

MAGNES COLLECTION OF JEWISH ART AND LIFE, UC BERKELEY (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Tiberias, a 1944 painting by Marcel Janco.

Franklin, the question is, can we keep it?

Our last independent Jewish state lasted only about 100 years—from the Maccabean victory in 164 BCE until the Romans took over. (Life lesson: Never invite the Romans in to solve your domestic problems.) We didn’t do too well governing ourselves during that century.

cross. Though precarious, we often flourished; tragedies abounded, too.

conservative

I celebrate Israel’s 75th anniversary with a full heart. We are living in only the third time in 3,000 years that Jews have had sovereignty in the one land to which we are indigenous.

As Andrés Spokoiny,

president and CEO of the Jewish Funders Network, noted in The Forward, the Hasmonean state saw a succession of venal Jewish leaders, rampant corruption, territorial expansion and annexation of non-Jewish populations, the blurring of separate internal institutional powers, divisions within the government and reliance on a single foreign power. He added: “The miracle ends in catastrophe, and becomes a short-lived, failed experiment.”

Eventually, after the collapse of the Second Temple, the rabbis created a jewel, rabbinic Judaism, out of the ruins. Babylonian Jewry built a new Talmudic Judaism to engage the mind and spirit. What about us? Will we learn from the past and avoid going off the rails? Will we fuse the greatness of democracy with the best of Judaism to keep Israel from falling into sectarianism, ultra-nationalism, expansionism and continuing violence? God, I hope so.

Rabbi Gilah Langner

Congregation Kol Ami Arlington, VA

reconstructionist

Sovereignty can be overrated. Sometimes, though, it’s vital. In order of importance, there’s Am Yisrael, Eretz Yisrael and Medinat Yisrael—people, land and state. Masada, that storied site, actually marked a first-century dead end: Extremists there held independence as the supreme value, even above life. Jewish history and values moved north, where, in choosing to accommodate rather than revolt against Rome, the Jews of that region accepted reality, lived in the land and developed the Mishnah. For nearly two millennia since then, while solemnly singing of sovereignty, we’ve pursued holy, creative, communal Jewish life under crescent or

With 19th-century secular nationalism, we debated the cultural Zionism of Ahad Haam versus the political Zionism of Theodor Herzl. Had sovereignty returned a decade earlier, many more Jews might be alive today, so yes, independence matters. Yet nationalism breeds insularity, and home ownership has its headaches. This diaspora rabbi prays (and donates, organizes and advocates) for many more years of a State of Israel that’s yet more democratic than it is at 75—while nurturing moral Jewish spirituality that transcends space and time. To tap statehood’s great potential, let it never become our idol.

Rabbi Fred Scherlinder Dobb Adat Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation Bethesda, MD

reform

Jewish yearning for a home and place of self-determination in the land of Israel dates as far back as the prophet Jeremiah, who lamented the destruction of Jerusalem and the exile to Babylon around 586 BCE. Psalm 137, attributed to Jeremiah and popularized in song by Don McLean and Jimmy Cliff, among many, grieves, “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat, sat and wept, as we thought of Zion.”

Today should be a time of joy and celebration. We have a home and the national self-determination that we yearned for over millennia. Yet instead, many of us continue to weep. While we may have returned to the land of Zion, we have not yet fulfilled the dream of Zion—the creation of a sovereign nation and society that embraces all Jews, all peoples, and that is grounded in righteousness, justice, democracy and peace for all. As a lover of Israel, I approach this Yom Ha’atzmaut with a breaking heart. I weep for our unreached potential to truly be a “light unto the nations.” I weep for the pain, fear and threat that currently runs like a river through the land.

Rabbi Dr. Laura Novak Winer Fresno, CA

Israel’s founding turned the longprayed-for “ingathering of the exiles” into reality and massively altered the Jewish diaspora. We went from being a tolerated minority scattered among the nations to knowing we control our destiny. Jews in America could stand prouder (although Jews in Arab countries were subjected to Nuremberg-style laws and were driven out of places we had lived for many centuries). And while the Jewish leadership of 1947 accepted the UN Partition Plan, the Arabs rejected it, and resident Palestinians became either scattered refugees or citizens in a country to which they would have a complicated loyalty.

While we can take great pride in its countless accomplishments, the State of Israel has struggled to create a society that respects diversity and embraces all Jews regardless of origin or outlook. Sephardim and Mizrahim, Ethiopians and Russians, religious and secular have all struggled to find and define their place in Israel. Israel’s founding resulted in Jews having to govern not only themselves but non-Jews—namely, the Arab population, which numbers 20 percent “within the Green Line” and 80 percent of the West Bank. Is it a state of Jews or a Jewish state? Amid the intense rancor of this period, I honor the state and pray that it can be all that its founders hoped it could be, as expressed in its Declaration of Independence.

Rabbi Amy S. Wallk Temple Beth El Springfield, MA

modern orthodox

These 75 years of the existence of the State of Israel do not just resolve 2,000 years of exile but bring to a climax 3,000 years of Jewish history. It is a surprising redemption: Many of us were under the

SPRING 2023 | MOMENT 19

impression that it would come in the blink of an eye on the wings of eagles. It turns out instead to be the redemption that Maimonides, quoting the Talmud, predicted: “There is no difference between this world and the messianic era except that the Jewish people will have sovereignty in their land” (Sanhedrin 99a).

Though one can be a religious Jew in Brooklyn or Washington without the modern State of Israel, the existence of this normal and imperfect state, after 2,000 years of waiting, is a messianic gift, one vital for the continued existence, safety and flourishing of the Jewish people. Its very existence confers a new religious obligation upon us: that of being a great nation on the world stage, as God first said to Abraham when He led him to the land, to “be a blessing to all the peoples of the world” (Genesis 12).

Rabbi Hyim Shafner Kesher Israel: The Georgetown Synagogue Washington, DC

orthodox

When the State of Israel was declared, many skeptics thought it wasn’t going to last. Some thought that it would be impossible to create a stable country militarily or socially; others saw a Third World backwater. And yet today Israel is a military, social and technological powerhouse and the largest Jewish community on earth.

Traditional Jews do not view history as random, as a series of peaks and valleys or a Hegelian spiral. We see it as leading to a conclusion: the realization of the Jewish vision for the world and the time of messianic redemption. Israel’s founding and its persistence over the decades offers optimism that although the Messiah has not yet come, some building blocks have been put in place. There’s the ingathering of exiles, a growing religious renaissance and a remarkable social cohesion that, despite the huge chasms that separate people politically, allows the country to come together at important moments. What we hope is for Israel to become a nation

that fulfills the Jewish mission: not to lead the world in unicorns or military might, but to make the teachings of the Torah and Jewish wisdom fundamental to our families and to the running of the nation. Israel must become a light unto the nations for spiritual, not only material reasons.

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein Cross-Currents Los Angeles, CA

sephardic

In the short time since I received this question, so much has changed in Israel that it seems to refer to another country. And yet the question is appropriate to the situation. The answer can be found in Deuteronomy 32:7: “Remember the days of old,/ Consider the years of ages past;/ Ask your parent, who will inform you,/ Your elders, who will tell you.”

How can 3,000 years of Jewish history inform us about Israel’s future when the country seems to be at the brink of a civil war and, according to some, the establishment of a dictatorship? Throughout the generations, many individuals have abandoned their Jewish identity willingly, while many others have joined voluntarily. We have experienced persecutions and catastrophes but also periods of tranquility and prosperity; the Jewish nation has expanded and contracted, but we have remained, against all odds, a nation.

This phenomenon, truly a miracle, reflects the essential values of the Bible, the principles that guide our behavior as a nation and are a corrective mechanism against apathy, dictatorship and total corruption. The ideas of Shabbat, of humanity being created in the image of God, the importance of supporting the poor, the importance of education and the golden rule “love others as you love yourself”: All Jews, even if they consider themselves unaffiliated or not observant, are guided by them one way or another.

In summary, I am a hopeless optimist. Our history teaches that we will overcome the current crisis, heartbreaking

and scary as it is, and emerge from it wiser and stronger.

Rabbi Haim Ovadia Torah VeAhava Potomac, MD

chabad

Seventy-five years is a long time— according to King David in Psalms, an average life span. Three thousand years (or more) is a whole other story. There is a big difference, especially in the region where Israel exists, between even an entire generation and the literal span of historical existence. The mistaken notion that Israel is somehow “only” 75 years old causes, and also reflects, several problems.

I have long thought that making peace with a 75-year-old entity, especially one that expounds Western values, is a challenging prospect for other nations in the Middle East that live with many ancient traditions. But coming to terms and even peacefully cooperating with an entity that is several millennia old might be another story. Seniority commands respect, especially in that part of the world, and we should cultivate that aspect of our identity—for others’ sake and for our own. Strengthening our own Jewish knowledge and traditions, especially in the young, is a good start here in the diaspora as well as in Israel, where basic awareness of simple Jewish concepts, historical as well as religious, is sorely lacking in too much of the population.

“Israel” is not a newcomer to the region. Basic archaeology confirms that we’ve been there as a people, with Jerusalem as our center, well before anyone else who currently claims it. But more than mere history, our real claim to the Holy Land is G-d’s promise that it will be the homeland of the Jewish people. If we internalize that sentiment and find courteous and respectful ways to share it, then prospects for understanding and for replacing conflict with coexistence are greater. Am Yisrael Chai!

Rabbi Levi Shemtov Executive Vice President, American Friends of Lubavitch Washington, DC

SPRING 2023 20

A biblical symbol of peace and plenty, the fig tree still flourishes in Israel today—but what promise can it hold in the heat of conflict? “Fruit of the Land” by Israeli poet and peace activist Yonatan Berg strikes me as a secular prayer lodged within a lament. Its plea? To refuse the tools of war, both literal and figurative. Moment is proud to publish the poem for the first time in its original Hebrew alongside Joanna Chen’s splendid English translation.

Jody Bolz, Poetry Editor

FRUIT OF THE LAND

The fig tree’s fruit falls to the ground, Its purpled flesh still burning.

A harsh wind rushes by, ruffling the treetop Like the head of a beloved child, and dies Within me. For once in my life I want to say rain And get soaked, to say eternity And lose both past and future.

The wire fence shudders and stills, A candy wrapper shudders and stills, Yet this shuddering inside me goes on. I ask for the courage to refuse The iron tools imprinted within my eyes.

I grasp the bark of the fig tree, Soil and sugar stick to my fingers: A filigree of bitter and sweet.

Translated by Joanna Chen

ץראה ירפ

,שיבכ לע םילטומ הנאת תוריפ

.רעוב דוע םהב לוגסה

הפלחו הרבע הקזח חור

.יכותב םג

תרמצה תא הערפ איה

בוהא דלי לש ושארכ

בטריהלו םשג רמול שקבמ ינא ייחב תחא םעפ

.דיתעהו רבעה תא דבאלו חצנ רמול

תעגרנו תדעור תכתמה רדג

תעגרנו תדעור קתממ תפיטע

ךישממ דימת דערה ונכותבש הז דציכ

ברסל חוכ שקבמ ינא

.ייניעב ורתונש לזרבה ילכל

העוצפ הנאתב זחוא ינא

:ידי לע םירתונ רפעו רכוס

קותמהו רמה לש ךוביסה

Yonatan Berg is the youngest-ever recipient of the Yehuda Amichai Prize for Hebrew Poetry and has won several other literary awards. He has published three books of poetry, one memoir and two novels. His most recent collection, Frayed Light, translated by Joanna Chen, was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award in poetry.

POEM YONATAN BERG

jewish word

Israel: What’s in a Name?

will flee and his brothers submit. This blessing was realized when, after the death of King Solomon and the collapse of the biblical Kingdom of Israel, the Kingdom of Judah emerged as its primary successor. But Judah was eventually invaded by the Babylonian Empire, its Temple destroyed and its people scattered. Some 70 years later, in the 6th century BCE, with the state reforged as Judah and later as the Greco-Roman Judea, Jews built the Second Temple and restored the kingdom. Various incarnations of Judea surfaced throughout the Alexandrian conquests, the Maccabean revolt and ultimately the Jewish-Roman Wars.

n the wake of the November 1947 UN vote on the partition of the British Mandate of Palestine, while Jews across the country were celebrating, David Ben-Gurion remained sober. Preoccupied by the imminent struggle to secure Jewish sovereignty in Palestine, he meticulously created a list of necessities for the fledgling state. The country would need an army, an airport, a civil administration and also a name.

A mere two days before the new state declared independence, with hundreds

dead from Arab-Jewish violence and enemy armies besieging Jerusalem, the Jewish National Council, then the primary executive body of Jewish Palestine and led by Ben-Gurion, met to create the Declaration of Independence. Among pressing military and logistical concerns, it was incumbent upon the council to come up with a name.

Initially, the most popular name for the would-be state was Judea, which derives from Judah, the fourth son of Jacob. In Genesis, Jacob blesses Judah as the leader of the tribes, before whom his enemies

Given this storied and emotionally salient history, it made sense that the members of the National Council would consider Judea as a name for their state. Indeed, “most people in the international community thought the name would be Judea because it was the last sovereign Jewish state in antiquity,” notes Martin Kramer, a Middle East historian at Tel Aviv University. However, the name was rejected, primarily on the grounds that it was irredentist—that is, that it advocated for the reclamation of lost historical territory—and that it might inflame an already volatile situation. “Under the partition plan, much of [ancient] Judea was not in the modern state envisioned by the United Nations, and Ben-Gurion was trying to make a vision of Israel as broad as possible,” says Gil Troy, a professor of history at McGill University. Ben-Gurion saw the danger in the territorial claim inherent in the name Judea. Neither he nor the council wished to further antagonize the international community, so they rejected it.

Another popular suggestion for the name of the new state was Zion. The logic was simple: Zionism is the ideological project and political pursuit of establishing a Jewish state, so Zion would be the state. Kramer notes that “in the Bible, Zion sometimes meant all of Israel” but that “Har Tzion, Mount Zion, was outside the Jewish state licensed by the partition plan.” This name was likewise rejected in the interest of avoiding provocation, as the city of Jerusalem, where Mount Zion

I

GUSTAVE DOR É SPRING 2023 22

Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, Gustave Doré (1855).

is located, was designated an international city under the UN partition.

The name Ever was also considered. Derived from Ivri, the Hebrew word for “Hebrew,” Ever had the benefit of not representing a territory. However, writer Moshe Brilliant, in a 1949 Palestine Post article on the National Council’s deliberations, explained that “no one liked it.”

In addition to those names considered by the council, there were also some omitted from the conversation. The most prominent of these was the name Palestine. After the third Judean war and the destruction of the Second Temple, the Romans changed the name of the province of Judea to Syria Palaestina, derived from the Greek name for the region, Philista, meaning “land of the Philistines.” Given that the Philistines were the Israelites’ ancient enemy, it’s unclear whether the Romans merely picked the Greek word for the region or whether the choice was made out of spite. In the following centuries, as the land passed from the Byzantines to the Arabs to the Ottomans, it retained this new name in various incarnations, including “Palestine.”