7 minute read

YOSSI KLEIN HALEVI

Jewish history is a very strange mixture of success and failure. The Bible is the strangest ancient epic because its protagonists, the Jewish people, fail at their mission. Their mission is to maintain a level of collective holiness, to live in the intensity of a relationship with a revealed presence of God in the desert, in the mishkan (tabernacle) and later in the Temple, through prophecy. And we failed. We couldn’t hold that level of holiness, and we went into exile, supposedly to learn from our mistakes and to do some form of penance. That’s the story that Jews have told themselves for thousands of years, that the Torah tells. It’s a magnificent story of failure.

And now, we’re at a particular moment, coinciding with our 75th anniversary, when the ability of Israeli society to hold together is really hanging in the balance. The question we’re facing is: Is this the beginning of the unraveling and one more tragic example of Jewish self-destructiveness? Or is this the beginning of finally facing deeply distorting processes in Israeli society that we’ve allowed to go unchecked—whether it’s settler violence or the ultra-Orthodox state within a state?

If, almost at the last minute before these processes become impossible to stop, we face them, maybe this crisis will be a blessing, however traumatic. I hope I’m wrong, but I fear the worst is still to come, and that the decent, Zionist, Jewish, democratic Israel I fell in love with as a young American Jew, and that is embodied by the two flags on the bimah of American synagogues, is in danger.

Hope is being expressed every day in the streets of Israel. I never thought we would see a movement of this magnitude and intensity where every week, sometimes every day, hundreds of thousands of Israelis are turning out. We’re fighting for the right to continue loving Israel, to continue being proud of Israel. That fighting spirit has taken liberal Israelis by surprise. I come from the center, and we are militant centrists, which means we’re a little bit left-wing, a little bit right-wing. But now, we really have to fight for the center. If we fail to maintain a minimal sense of unity, of cohesiveness, then to my mind it’s the effective end of the Jewish story.

So long as there’s a Jewish state, the diaspora is not exile, because exile is the condition of coerced distance from the land of Israel. If, God forbid, there’s no Israel, the exile returns. There’s no diaspora anymore, there’s just exile again. And I don’t believe we will be able to sustain Jewish life with the failure of a Jewish state. That’s what we’re fighting for now. We’re fighting for the future of the Jewish people, not just for the state of Israel. This is showtime for Jewish history.

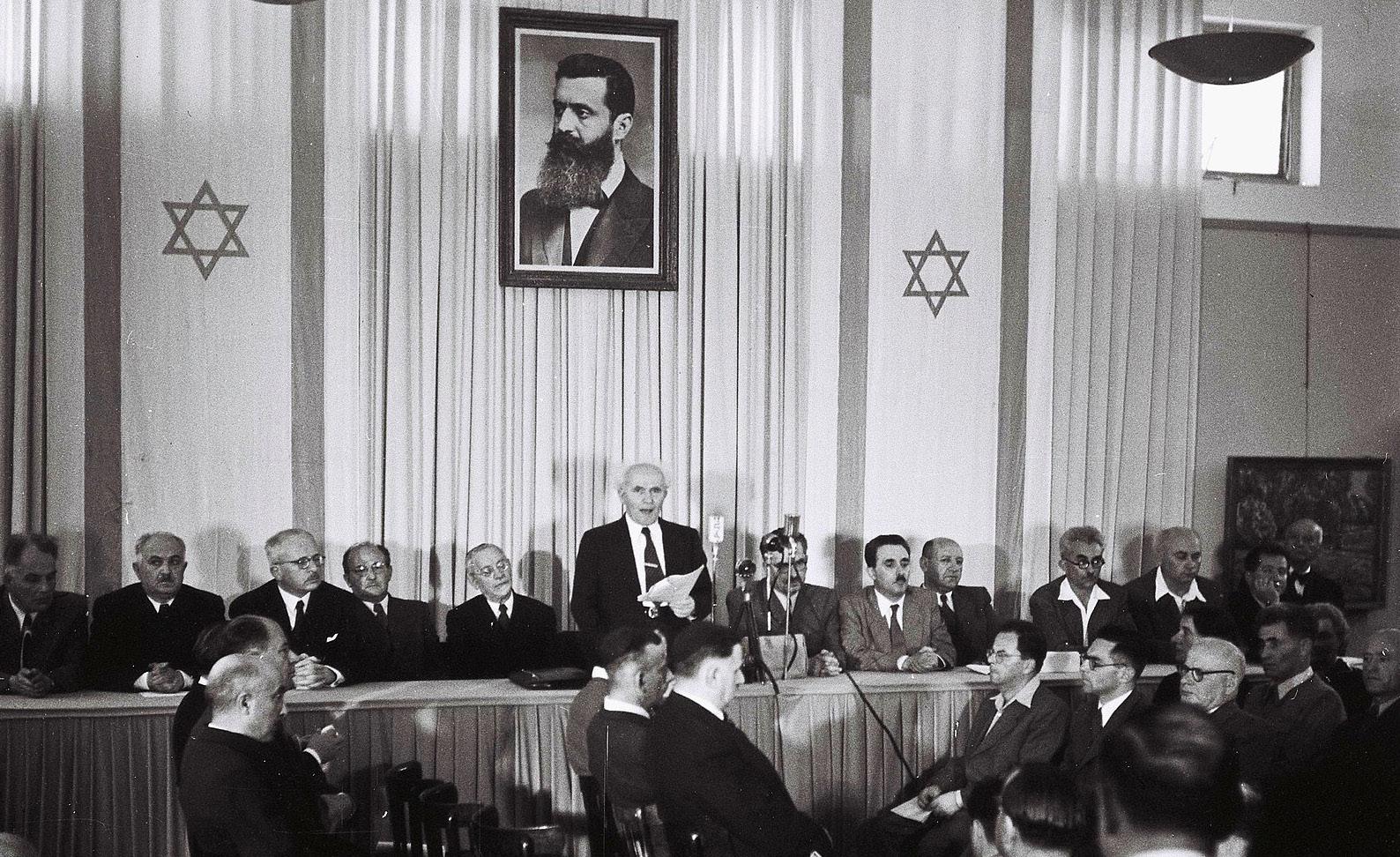

And the fourth is the creation of Israel. Those are the four great, overwhelming moments that have shaped Jewish life. But the Israel that was created in 1948, the Israel of its Declaration of Independence, promising, according to its noble text, “freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel;” and “complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex;” a “guarantee of freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture;” “safeguarding the Holy Places of all religions” and “faithfulness to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations...” is the Israel whose existence is now imperiled by a radical alternative: a halachic-nationalist state in which other religions—Islam and Christianity—have no rights to full citizenship or possibilities of true allegiance. So this moment of existential crisis turns on the most fundamental issue of all: Is Israel to be a liberal democracy in which all who live there have equal rights, or is its destiny to be a Bible-authorized nationalist theocracy? Is it a state for Jews or a state for Judaism?

I saw, during the recent demonstrations, that there were two great hangings posted on the walls, I think outside the Jaffa Gate of the Old City—Turkish walls, of course. And one of them was the enormous Israeli flag that the protesters have adopted, rather brilliantly, making the point “We are patriots, too.” And the other was a huge flag with the text of the Declaration of Independence and that very important and dignified clause about the protection of minority rights.

Simon Schama

I think there are four fundamental moments in Jewish history. One is the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. The second is the expulsion of Jews from Iberia in 1492. The third is the Shoah.

It was moving to me because throughout our history—not, of course, just during the Shoah—Jews have suffered because our minority rights have not been protected. So it was critical to the founders in 1948 to say very unequivocally that minority rights would always be protected. And anybody who reads the crucial document about liberal constitutional democracy, which is John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, will know that one of his bugbears, even though he’s a classic liberal, is what he calls majoritari- anism or what we’ve called since, the tyranny of the majority. And the entire program of these proposed reforms in Israel is imposing, as hundreds of thousands of people of all ages and types understand, a majoritarian tyranny. And democracy cannot stand with a majoritarian tyranny.

English historian Simon Schama hosted the five-part BBC documentary series The Story of the Jews, based on his three-volume book of the same title. His new book, Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations, is due out in September.

Aviya Kushner

There have been many dramatic moments in Jewish history, but certainly the establishment of the State of Israel and the incredible fact that Israel has survived for 75 years has to be a high point. It’s not just that there’s a country; the importance of Hebrew as a national language, an achievement that was unimaginable 150 years ago, can’t be underestimated. Nor can the fact that there is now a common second language among many diaspora Jews. It’s so rare for a language to be revived. It’s a tremendous achievement for Hebrew to be alive and to be so vibrant.

Of course, there were and are other Jewish languages. Yiddish is approximately 1,000 years old, and it was the common language of the Jews of Europe and Ashkenazi Jewry. Ladino, the mother tongue of Jews in the Ottoman Empire for 500 years, was the common language for many Sephardi Jews. So, prior to the establishment of the State of Israel, the Jewish world was split into Ladino speakers and Yiddish speakers. When Hebrew was revived, these two very different traditions folded together and started using Hebrew as their major language.

So to me, Hebrew is a bridge. It’s a bridge to tefilah (prayer) and to the Tanakh. It’s a bridge to contemporary

Israel. It’s a bridge to the medieval Hebrew poets of Spain. It’s an incredible bridge between Ashkenazi Jews, Sephardi Jews and Mizrachi Jews. It’s a bridge to many different eras, and it’s up to you which lane of the bridge you want to walk down. But you can’t even cross the bridge if you don’t speak any Hebrew. You’re stuck on one side and the rest of Jewish history is on the other.

Hebrew also offers a sense of safety and community. Recently I learned that each city in Iran had its own Jewish language—for example, the Jews of Isfahan spoke Isfahani. Why weren’t the Jews of Isfahan speaking Farsi exclusively? Because they needed a language that their neighbors didn’t understand in times of danger. Now, we have that on a much larger scale—instead of a “city” language, or a regional language, we have a national language, a language of the entire Jewish people.

Today, there’s a growing division between Hasidic Jews or ultra-Orthodox Jews and other Jews—and Hebrew can help bridge that gap as well. You may not be fluent in Yiddish, but you may be able to speak enough Hebrew to get through that gap. That’s why a secular Israeli might more easily have a conversation with a Hasid at a bus stop compared to what you might see in the United States. Why? Because there’s a common language

My personal view is that a major reason why there’s a growing gulf between American Jewry and Israeli Jewry is because American Jewry hasn’t emphasized Hebrew language study. If you speak with South American Jews, their Hebrew is often excellent. European Jews often have terrific Hebrew. It’s only in the United States that the Hebrew level is very low. That’s why American Jews are sort of on an island and the rest of Jewry is communicating through Hebrew. But American Jews who can acquire competence in Hebrew can participate in the world Jewish conversation.

As someone who teaches in college, I encounter a lot of teenagers and 20-somethings with views on Israel that are really divorced from what you might think if you read a newspaper in Hebrew.

A lot of the students I encounter who have very strong opinions on Israel are unfortunately not able to read anything in Hebrew. So they’re always getting their information through a curtain. They’re not able to listen to Israeli radio or watch Israeli television or speak to Israelis in Hebrew. They have strong feelings on Zionism, but often can’t read essential texts in the language they were written in. When you read a lot of prominent American commentators on Israel, the people they quote are almost invariably journalists or scholars who speak fluent English. That’s great, but that’s not everyone in Israel. I would say a lot of the voters for Netanyahu don’t speak a word of English. So if you’re only speaking to the reporters who maybe made aliyah, or are American in some way, you’re not really getting the full picture.

Do people see speaking Hebrew as a political statement? That is the big danger. I see more and more young people who are really drawn to Yiddish or Ladino. My personal theory is people want to connect to Jewish language but feel uncomfortable making any sort of statement in favor of Israel. Unfortunately, that means they feel pressured to avoid the Hebrew language. There have also unfortunately been writers and academics who have turned any connection with the Hebrew language of any era into a political and even a military statement. I have endured some really nasty statements. For example, when I was speaking recently at a panel on translation at a literary conference there was a woman in the audience who kept raising her hand over and over and saying, “Why don’t you translate from Arabic?” And so I said, “Because I’m not fluent in Arabic.” She just wouldn’t let go. She kept disrupting the talk and finally said, “Nobody should be translating Hebrew.” I responded, “Thank you for saying this out loud because this is the way, unfortunately, a lot of people in this space feel—that Hebrew as a language is somehow illegitimate.”

I believe every language is legitimate. I certainly don’t believe in banning languages or boycotting them. For the Jewish people, the revival of Hebrew is