EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Maddy Scharrer

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Rayyan Bhatti

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Maddy Scharrer

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Rayyan Bhatti

PHOTOGRAPHY LEADS

Molly Claus

Indu Lekha Konduru

GRAPHIC AND ILLUSTRATION LEADS

OPERATIONS DIRECTOR

Adina Kurzban

INTERNAL RELATIONS

DIRECTOR

Makaylah Maxwell

PUBLIC RELATIONS

DIRECTOR

Kaitlyn Dietz

EVENTS DIRECTOR

Kasia Kirmser

CULTURE EDITOR

Kate Reuscher

ARTS EDITOR

Talia Horn

LIFESTYLE EDITOR

Tessa Almond

FASHION EDITOR

Marceya Polinger-Hyman

ONLINE EDITOR

Vanessa Snyder

WRITERS

Tessa Almond • Sarah

Berendes • Elise Daczko • Lillian Hescheles • Alyna Hildenbrand • Talia Horn • Allie Ketelsen

• Lily Kocourek • Makaylah

Maxwell • Marceya PolingerHyman • Josie Purisch • Isabella Rotfeld • Adelaide Taylor

Breanna Dunworth

Amelia Tingley

STYLING LEADS

Shira Malitz

Jessie Wang

SHOOT PRODUCTION LEADS

Sydney Alston

Heidi Falk

MODEL MANAGEMENT LEAD

Kaleyah Rivera

ART

Rayyan Bhatti • Zoee

Boog • Elise Daczko •

Breanna Dunworth • Natalie

Khemelevsky • Amelia Tingley

PHOTOGRAPHY

Rayyan Bhatti • Hannah Byma

• Molly Claus • Heidi Falk • Indu Lekha Konduru • Maya Stegner

• Paige Valley • Sofia Wells

SHOOT DIRECTION AND STYLING

Sydney Alston • Kayleigh

Carlos • Bethany Ehlenbach • Heidi Falk • Kavya Kanungo • Shira Malitz • Devon Moriarty • Kate Pennoyer • Lila Robinson • Jessie Wang • Sofia Wells

MODELS

Kelly Chi • Gueda Daff • Soyer

Foley • Alyna Hildenbrand

• Kavya Kanungo • Lily Meinertzhagen • Madeline

Miller • Claire Neblett • Kate Pennoyer • Khinny Shin • Arshiya Singh • Zoe

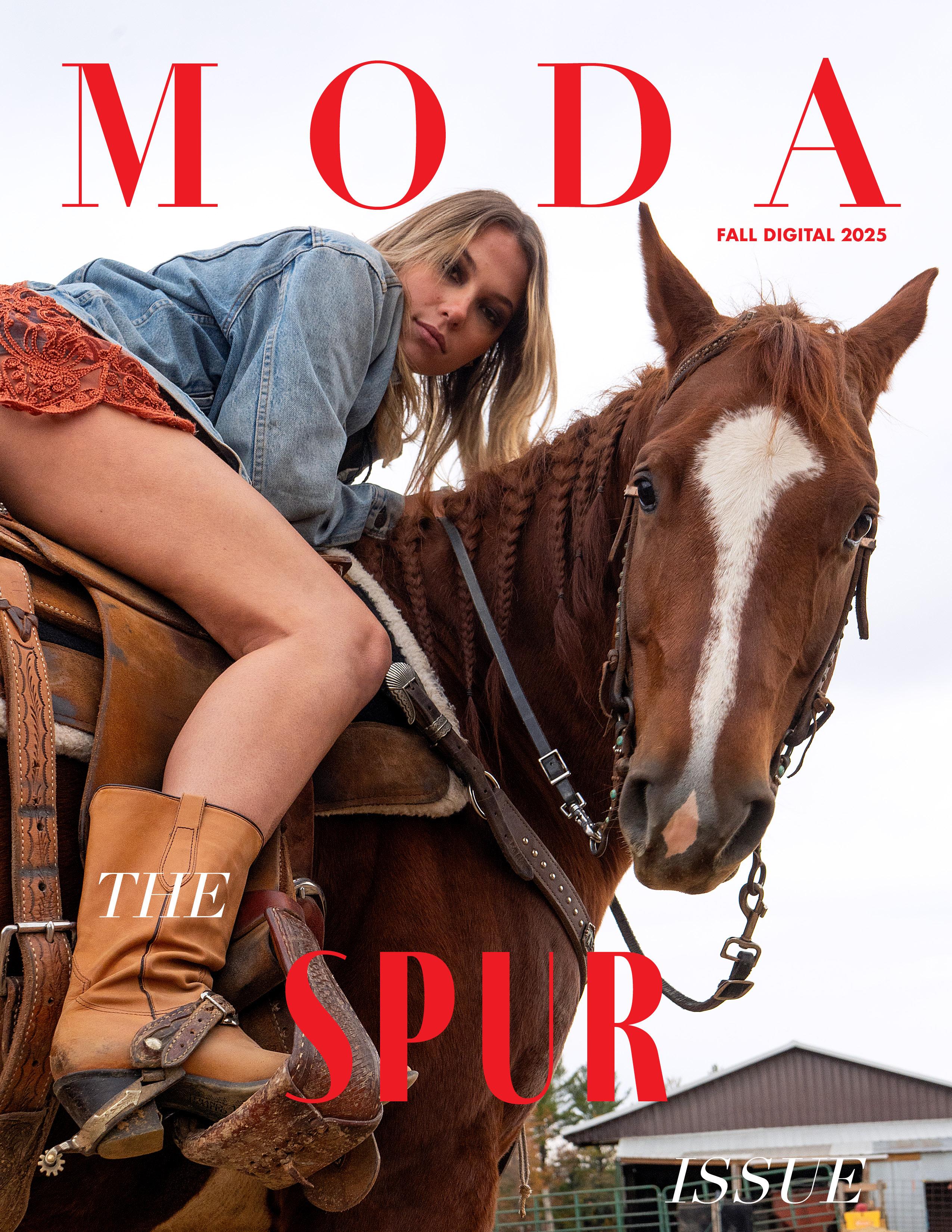

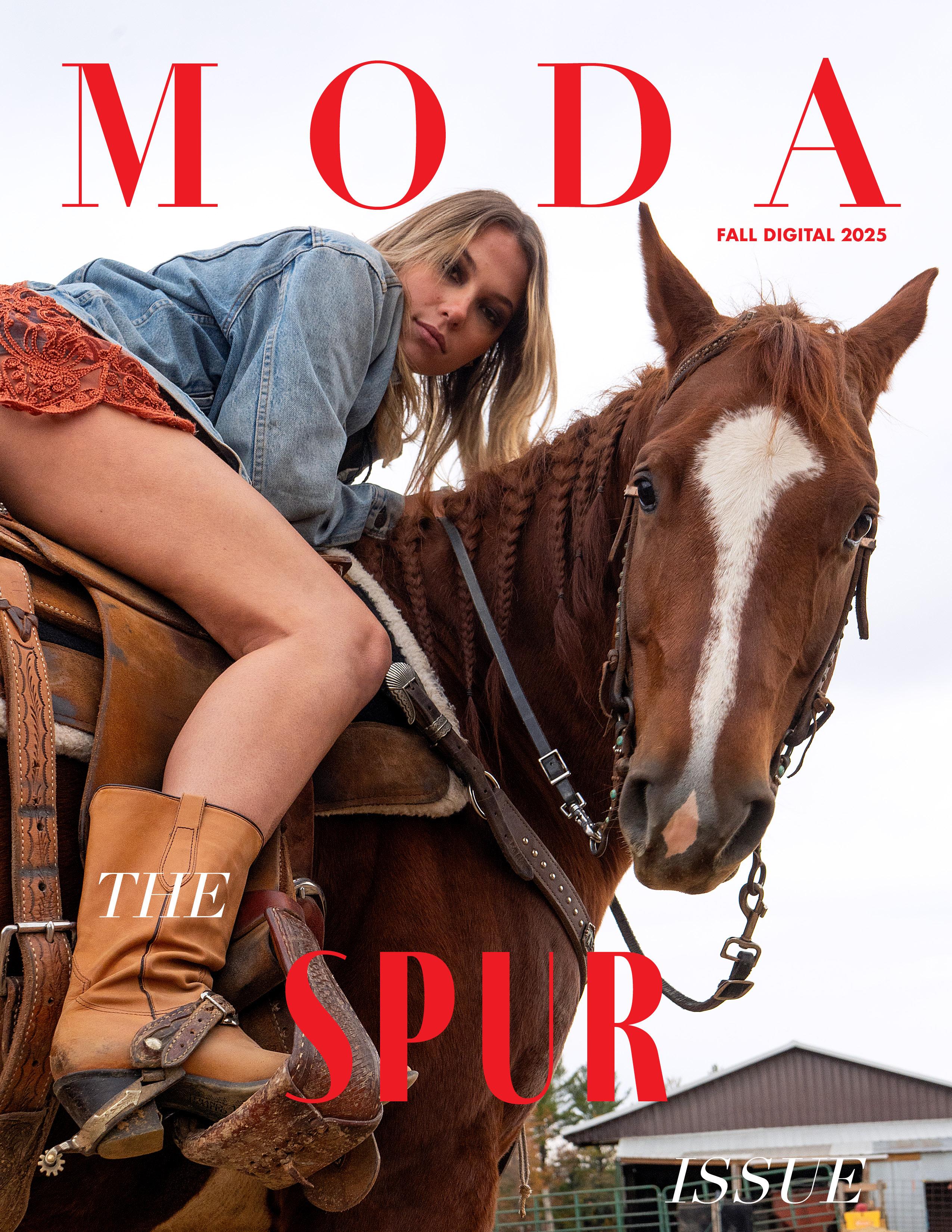

06 Buckle Up: Rebranding the Buckle Bunny

Reclaiming the rodeo’s most misunderstood muse: how the buckle bunny turned a stereotype into a symbol of feminine power, fashion and freedom

20 Saddle Up, Babe! We're Going Out

A modern ode to Western glamour and rewriting your nightlife narrative

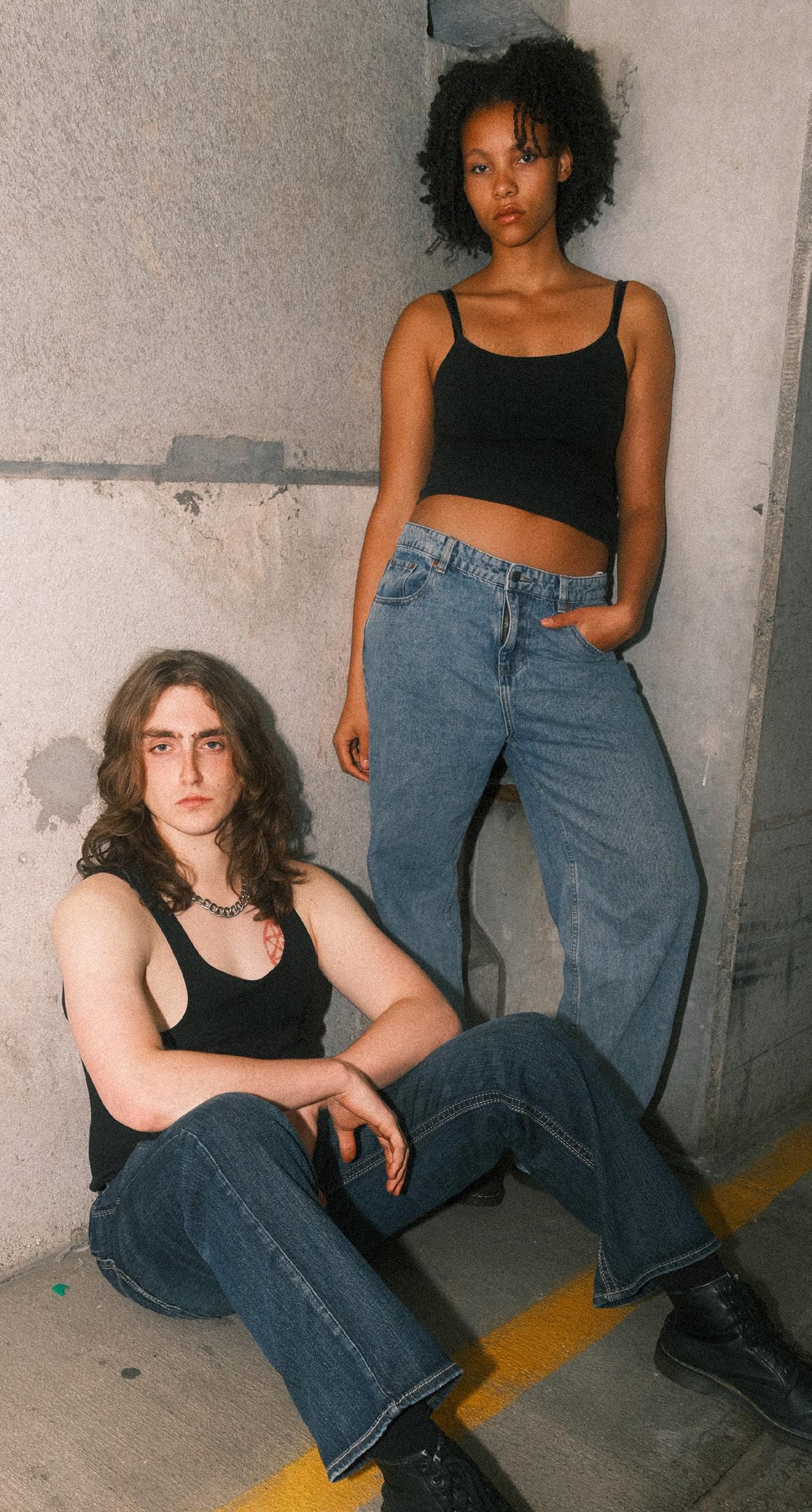

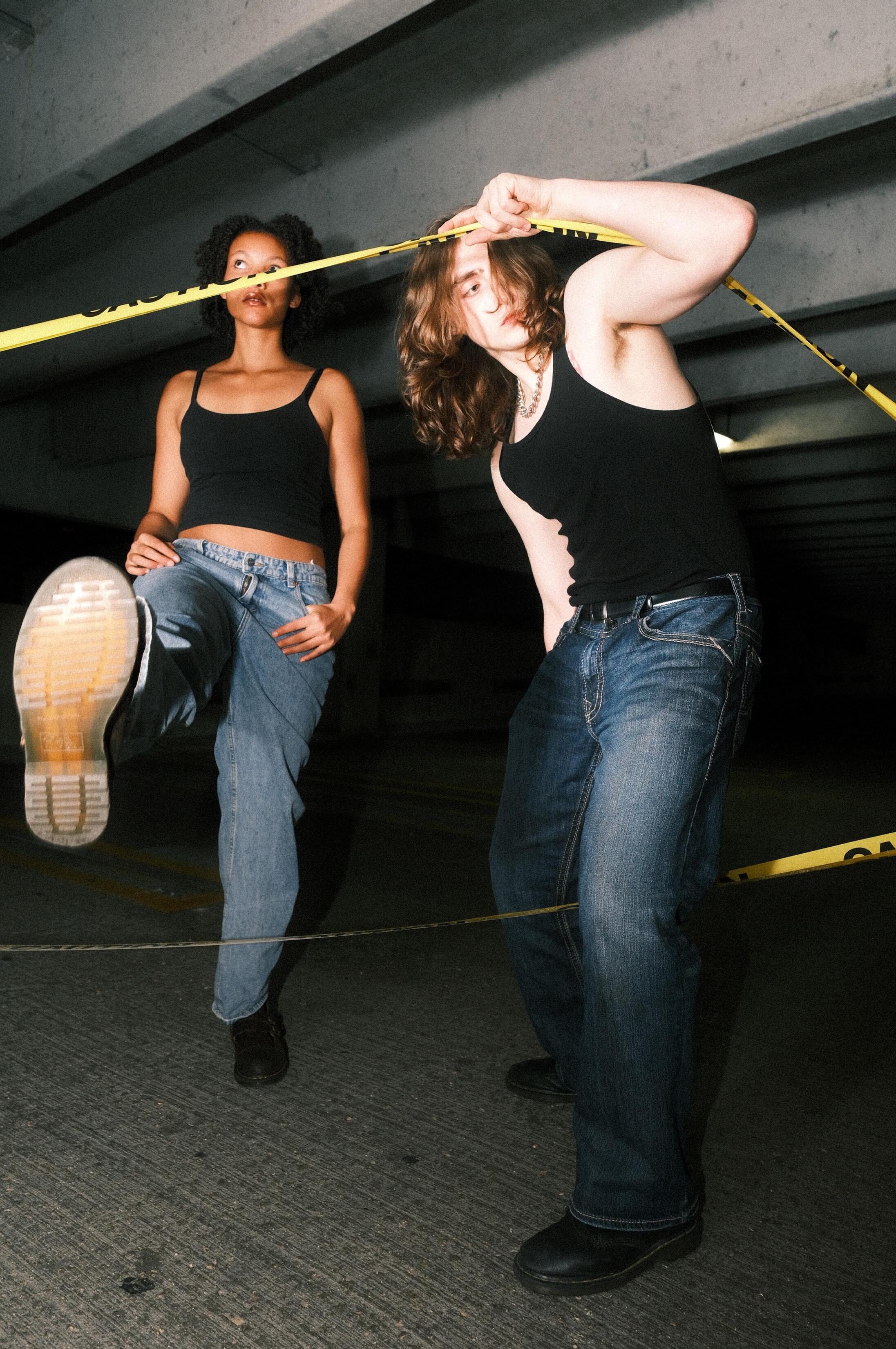

33 A Denim Revolution

Stitching a story through the decades

36 Navigating the Vintage Americana Aesthetic in a Modern Landscape

Can you embrace the aesthetic while rejecting the sentiment?

17 Queer Country

Returning to the roots of the genre

18 Clear Eyes, Full Hearts, Small Towns

How film and TV portray the beauty and burden of the Americana small town

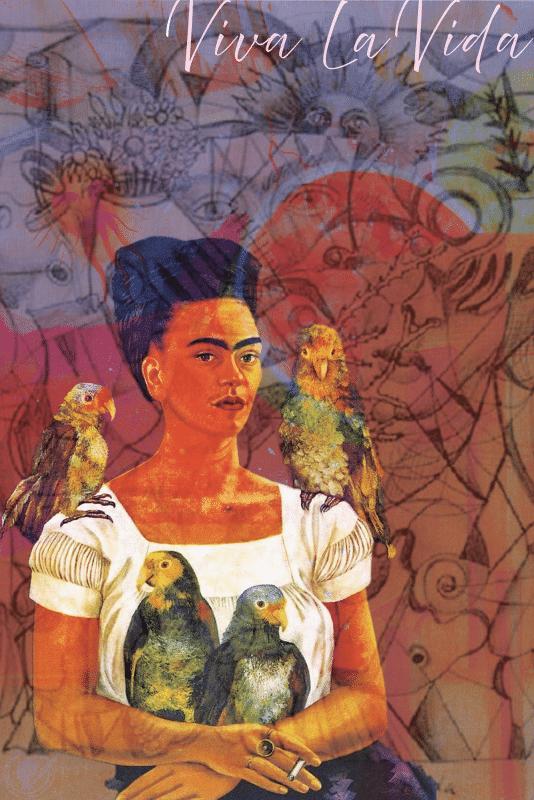

40 Frida Kahlo's Queer Revolution

How Frida Kahlo redefined art, identity and the queer imagination

10 Honky Tonk Collective

How line dancing speaks to us all

14 Threaded

How Chicano culture transformed functionality into fashion

24 The Disappearance and Restoration of Native Languages

Centuries of colonization have silenced Native voices, but a new generation is determined to reclaim them

39 From "Woke" to Western Cowboy culture is trending — and so is conservatism

42 The Roots of the Braid: Beyond the Cowboy Hat

Examining the history behind braids

12 Badgers in the Saddle

An introduction to equestrian sports on the UW-Madison campus

30 Southern Comfort in the Kitchen

Exploring the history of classic Southern dishes and their ties to community and connection

26 The Reins

Dear Readers,

Welcome back to another school year!

Many beloved Modies who were formative in shaping what our publication has become today graduated last spring, and we thank them for their impactful contributions to our organization. With this, many leadership torches were passed, and I am both ecstatic (and admittedly nervous) to be stepping into the role of Moda’s Editorial Director. Moda has been a pillar of my college career, and I've always aspired toward this position. Still, I entered the school year a bit apprehensive about the large shoes I was to fill.

But sometimes, you just have to leap and embrace the uncertainty of change.

When I joined Moda my freshman year, we were still doing monthly issues, and our overall structure was very different. Witnessing how our organization has grown and changed over four years has been an incredible journey. One thing I’ve always adored about Moda is how dedicated its members and community are. So thank you for reading, thank you for your passion and thank you for evolving with us.

As I reflect on how our organization has evolved, this theme felt fitting. Spur is unlike anything we’ve done before. This made it somewhat of a challenge, but one we were up for. We spun a few definitions together to evoke Western undertones that are making a resurgence in our culture while also paying attention to how our past has shaped or redefined this “country” landscape today.

Like a spur driving into a horse, the catalyst for movement can be painful. We tie these stories to their messy, knotted and sometimes uncomfortable roots in our history to convey how strides have been made along the way. As we evolve, we must tend to our roots if we want to grow.

In her article “Queer Country,” staff writer Sarah Berendes dives into these roots and finds that the inclusivity and acceptance found in country music today is actually a return to the ideas the genre was founded on.

Arts Editor Tessa Almond underscores the impact of Westernization on Indigenous communities in her article "The Disappearance and Restoration of Native Languages.

Staff writer Lily Kocourek puts to words what we’ve all been thinking: “going-out” fashion has gone country. In her article "Saddle Up, Babe! We're Going Out," she describes the Western-inspired styles returning to the bar scene.

I hope you enjoy the variety of stories selected, and that they spur some conversations.

Saddle up!

Warmly,

MaddyScharer

Reclaiming the rodeo’s most misunderstood muse: how the buckle bunny turned a stereotype into a symbol of feminine power, fashion and freedom

Written

by

Marceya Polinger-Hyman, Fashion Editor

Photography by Molly Claus, Photography Lead |

|

Shoot Direction by Heidi Falk, Shoot Production Lead |

Styling by Jessie Wang, Styling Lead |

Videography by Leah Bulson |

Modeled by Khinny Shin

The crowd goes wild as the bull bursts from the chute — eight seconds of chaos, dust and adrenaline. The rider clings tight, every muscle tensed, the crowd’s roar rising with each buck and twist. But when the buzzer sounds and the cowboy is thrown to the dirt, attention shifts. On the edge of the arena, framed by the golden glow of the floodlights, stands another kind of rodeo icon: the buckle bunny.

Her curls bounce beneath a black Western hat, turquoise jewelry glinting under the lights. The fringe of her black leather jacket sways as she leans against the fence, boots sunk into the dust, eyes alive with the same wild energy that drives the show inside the ring. She’s not just watching the spectacle — she’s part of it.

Historically dismissed as a rodeo groupie, the buckle bunny has often been reduced to a caricature of a woman chasing cowboys for the gleam of their championship belt buckles. But behind this intrinsically sexist stereotype, the buckle bunny has a huge impact on the South’s expectations of women. To rebrand her is to recognize that the buckle bunny is not just chasing cowboys; she is rewriting the meaning of Western style by incorporating pieces from the past and reminding us of all of America’s rich history. Shifting the conversation around the “buckle bunny” gives her the freedom to harness the power of her creativity, sexuality and power in the modern world.

The term “buckle bunny” emerged in rodeo slang in the mid-20th century, used as a way to poke fun at young women who hung around cowboys1. The label was often given a negative connotation and was associated with shallowness and frivolity.

The use of this term also signified a shift in rodeo culture and society. Cowboys weren’t the only ones getting attention anymore. Buckle bunnies brought visibility, beauty and unapologetic femininity to a culture that traditionally only celebrated male bravado. If a cowboy represented rugged masculinity, then a buckle bunny represented bold feminine power.

The rodeo itself has always been considered a spectacle more than just a sport.2 It is often trademarked by its pageantry and performance, with bold pieces like rhinestone-studded jackets, leather chaps and designer cowboy boots, turning it into a fashion show for Western style.

This fashion surge began in the 1940s and 1950s when those attending the rodeo began to embrace more eye-catching pieces.3 Rhinestones, embroidered shirts and leather were incorporated wherever possible. This marked the era of Nudie Cohn, the legendary tailor whose “Nudie Suits” were bedazzled with sequins, fringe and elaborate Western motifs.4

“The “Nudie Suit” — a universal name for the outrageously embellished stage costumes that became status symbols in country music circles in the 1950s and beyond — embodied the American Dream.”5 This style exploded in

1 Chris La Tray, “A Brief History of the Rodeo,” Smithsonian Magazine, July/ August 2022.

2 Ibid.

3 Natasha Samsonov, “From Rodeo to Runway: How Western Wear Became Luxury’s Latest Obsession,” The Mash Magazine, March 28, 2025.

4 Simon Harper, “Nudie Cohn: The Real Rhinestone Cowboy,” Clash Magazine, July 7, 2016.

5 “Nudie Cohn: The Original Rhinestone Cowboy,” Country Music Hall of Fame.

popularity and was worn by numerous famous individuals. According to the Country Music Hall of Fame, “In 1950, the couple opened Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors, the North Hollywood storefront and tailoring shop where Cohn would cultivate a celebrity clientele that included country and rock royalty — ranging from Hank Williams and Johnny Cash to Elvis Presley and Elton John.”6

This style adoption emphasizes that Western aesthetics are often very much about display as well as durability. It also influences the buckle bunny’s teased hair, turquoise jewelry, fringe jackets and glittering boots, which are all a direct result of the Nudie Cohn era. But what really makes the buckle bunny an icon isn’t the clothes she wears, but rather how she wears them.

She doesn’t just wear fringe, she flaunts its movement, turning each entrance into a stage-worthy strut. Her turquoise isn’t merely accessorizing; it’s a statement of belonging to a long Western history while bending it to her own modern desires. Connecting her to generations of women before her — ranch wives, rodeo queens, and Indigenous artisans 6 Ibid.

whose craftsmanship and symbolism shaped the region’s identity. Turquoise, in particular, carries deep meaning in Southwestern and Native cultures, symbolizing protection, strength and connection to the Earth.7

By wearing it, the buckle bunny is acknowledging those roots and situating herself within that ongoing Western narrative — one defined by resilience, artistry and connection to the land. Even her boots, which are usually scuffed from the dance floor, are still shining with rhinestones, capturing that paradox of grit meeting glamour. What truly makes her unforgettable is not the individual pieces, but the way she charges them with personality, humor, heritage and power.

The buckle bunny proves that Western style is not merely about the functions that were historically necessary. Now, this style can harness the realness of the past and the glamour of modern times. Whether she’s leaning on the rodeo fence or posting a TikTok fit check, her fashion tells a story that runs so much deeper than cowgirl boots and a western hat. She represents resilience, confidence and the rich history of the land so many of us call home.

7 “Turquoise: Its Significance in Native American Culture,” Indian Traders, October 29, 2018.

How line dancing speaks to us all

Written by Makaylah Maxwell, Internal Relations Director |

In a dimly lit room packed with line dancers, boots stomp against the worn floors and bass pulses through the speakers. Under the lights, people move in sync, swaying and spinning with a timeless joy. Music blares through the air, a country classic or a TikTok remix, bringing energy to the surface and spreading movement across the floor. Line dances are a remix of culture and community, a style of dancing where belonging meets a beat.

In its own way, line dancing is an expressive act of community, holding equal parts tradition and rebellion. It’s a space where people crave connection; the simple stomps and turns have the opportunity to grow into something more. What makes people love it so much isn’t just the music or the moves, but the way it invites everyone in. There’s no velvet rope, no need for a partner and no pressure to perform. There’s simply a shared rhythm, space and the unspoken understanding that everyone will learn the moves together.

Despite the popularity of line dancing now, many don’t know where its roots lie. “The Madison” line dancing style originated in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1957 from Black communities, and it is known as the first modern line dancing style.1 The coordinated steps done in lines birthed the namesake of “line dancing,” and it was popularized throughout the nation after being featured on the Buddy Deane Show in 1960.2 Despite this coverage, there is no surviving video footage

1 Richard Powers, “The Hully-Gully, French Madison, Hot Chocolate, and Electric Slide,” Stanford University.

2 “The History of Line Dancing: From Folk Roots to Modern Popularity,” Linedance NZ, July 31, 2024.

of Black communities dancing “The Madison,” an erasure of its roots and cultural beginnings.3

With its complex roots, line dancing has become intertwined with different folk traditions, disco floors and country bars. With every new beat, line dancing evolves and transforms into something everyone can enjoy. Through the efforts of Black and working-class communities, line dancing has been given the grit and soul we’ve come to enjoy. What keeps people coming back is the feeling that synchronized motion turns strangers into a unit. Each movement tells its participants that they are one, even when they’re apart. The dance floor becomes a place where outside worries and divisions don’t matter, and everyone is connected by

3 David Murray, “How the Madison and the Twist ‘Crossed Over,’” Wall of Sound, Oct. 5, 2007.

the music. It’s not just about dancing next to someone — it’s about dancing with them.

Now, in the state where the polka dance is ingrained in Wisconsin tradition, line dancing has also found its groove.4 In Madison alone, there are four places where you can put your boots on the ground. On Monday nights at FIVE Nightclub, the “Dairyland Dancers” offer dance lessons in line dancing, the swig, circle and two-step. Red Rock on State Street offers a place for you to two-step with friends after you take on the mechanical bull. Line dancing isn’t just meant for a young crowd, though — the Madison Senior Center offers line dancing lessons for popular styles like Boots on the Ground, Cowgirl Trail Ride, Cleveland Shuffle and Bad Boy by Luther Vandross.

It’s more than just steps and counts — these dances are storytelling in motion. Each shuffle and spin carries the memories of those who danced these dances before us. Dancing acts as a bridge across generations where grandparents, students and strangers can all move to the same beat. What makes line dancing powerful is actually its simplicity. Anyone can step in, find the rhythm and feel a part of the crowd, fostering a sense of community and belonging. There’s no need for a dance partner, all you need is a willingness to learn and groove. It’s a reminder that connection doesn’t have to be complicated — it’s just a stomp, a clap and a smile away!

Written by Elise Daczko |

Graphic by Breanna Dunworth, Illustration and Design Lead |

Amere 40-minute drive from the UW-Madison campus, members of the Wisconsin Equestrian Team gather at Sugar Creek Stables for another day of riding lessons. There is an atmosphere of encouragement, team camaraderie and strong work ethic amongst the riders as they tack up their horses, cheer each other on through drills and apply their max effort to a sport they love. But this admirable team was not formed overnight.

UW-Madison’s equestrian traditions date back to the university’s founding. In 1909, the construction of the Stock Pavilion, an exhibit hall built to house horses and host livestock shows, elevated the presence of horseback riding on Equestrian interest gained further traction in the 1920s as riding organizations began to form: the UW Hunt Club, the Bit & Spur Club of the Women’s Athletic Association and the all-women Prince of In 1939, these smaller riding clubs consolidated into the Hoofer Riding Club, providing the first student-led coed organization for riders on campus. Today, the organization continues to support students’ recreational and competitive equestrian pursuits.3

1 “Stock Pavillion,” University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries.

2 “Early Hoofers History: 1930s,” University of Wisconsin-

3 “The Hoofer History,” Wisconsin Hoofers.

The Wisconsin Equestrian Team, founded in 2000, is within the Hoofer Riding Club and consists of about 20 to 30 UW-Madison students led by Coach Andi Bill and Volunteer Assistant Coach Abby Douglas. The team competes in Hunt Seat Equitation style riding through the Intercollegiate Horse Show Association (IHSA),4 meaning that in horse shows, the rider is evaluated on their own riding style, position and technique rather than their horse’s performance.

“You draw a random horse, and you just have to get on and go,” says Ella Stufft, the 2025-2026 Wisconsin Equestrian Team Captain.

Stufft grew up riding horses in Highland, Michigan, and has been riding for over 10 years. Stemming from a fondness for her neighbor’s horses, Stufft was quickly drawn into the world of equestrian sports. She gradually progressed through various levels in the Hunter/Jumper discipline until showing on the A-Circuit during her high school years. Stufft was voted into captaincy of the Wisconsin Equestrian Team last spring, allowing her to give back to a sport that has given her so much.

“From the moment I joined the team, I had my eyes set on the captaincy,” Stufft says. “I love sharing my advice and expertise because I’ve been riding for so long, so having the opportunity to be a resource for other members is really special to me.”

Whether prospective members have been competing in horse shows for years or if it is their first time riding a horse, the Wisconsin Equestrian Team provides a comfortable yet rigorous learning environment for student riders of all backgrounds and disciplines.

“I was completely brand-new to the sport when I joined my freshman year,” says team member Amneet Kaur. “I was super nervous at first. Everyone seemed like they knew what they were doing, and I didn’t even know what a saddle was.

My teammates were so helpful, so I’d say our team is definitely a place where you can learn the skills from scratch.”

In high school, Kaur swam for her school’s varsity swim team, but she wanted to pursue a new sport in college. With a love for horses rooted in her experiences visiting her grandfather’s horses in India, Kaur decided that college was the perfect place to gain an affordable introduction to riding. During her time on the team, Kaur has enjoyed improving her technique and general riding knowledge, but above all, she most enjoys the support of her team.

“Anytime I get off of a ride at a show, everyone’s so supportive,” says Kaur. “Even if someone’s in the same ride as you and competing against you, we’re cheering each other on.”

Beyond these strong teammate connections and the dedication required to excel in equestrian sports, the sport celebrates the unique partnership between humans and horses.5 In reflecting on the differences between swim and equestrian sports, Kaur notes that while both are individual sports, the biggest difference between the two is decidedly the presence of the horse.

“You create a relationship with the horse, even before the competition or lesson begins,” says Kaur. “I still love swimming, but having the aspect of the horse as someone who you can bond with is just a completely different feeling.”

From the early origins of the Wisconsin Equestrian Team to its presence today, the team has always prioritized community and inclusivity. Stufft hopes these values will remain for the next generations of members to come.

“I hope members can build lasting connections on the team,” says Stufft, “and I hope they can find themselves along the way.”

5 Bjerkan, Christine, “The Cultural and Historical Significance of Equestrian Sports at the Olympics,” The Plaid Horse, July 25, 2024.

How Chicano culture transformed functionality into fashion

Written

Alyna Hildenbrand

The paisley-patterned fabric of a bandana is easily recognizable by many. Its rich history is woven through countless cultures, holding different purposes in each. Despite their functional origins, these vividly colored fabrics have crept into casual fashion and streetwear worldwide. Bandanas can be associated with many different groups: the LGBTQ+ community, bikers, rock groups and most often, cowboys. But this shift from functionality to fashion can be attributed to Chicano culture — otherwise known as Mexican-American culture — though they are not always credited for this impact.

Despite the different cultures and communities that wear them, when people think of bandanas, they might first picture a cowboy. This figure is likely a white man sitting on a horse with red fabric tied around his neck.1 This lasting image was created due to the prominence of Western movies from the 1930s to 1950s, linking cowboys with bandanas.2

In reality, Indigenous Mexicans are the origins of the North American cowboy. When Spanish colonists introduced horses and cattle into the land in the early 16th century, many hands were needed to tend to them. Indigenous Mexicans often worked these jobs, soon becoming known as vaqueros, a name derived from the Spanish word for cow, “vaca”, as well as “ero,” meaning worker.3

Despite vaqueros coming before the widely known “All-American” cowboy, many don’t associate them with the image.4 This is largely due to the villainizing portrayal of Mexican people in Westerns, leaving the role of the cowboy predominantly to white men.5 These trope-filled films ignore the historical context and origins of cowboys.

The overlap in cowboy culture is not the only connection bandanas have to Mexican-American culture. Bandanas were also used to protect from the blazing sun, or to signify affiliation with social and political groups.6 Bandana usage has also been heavily tied into Chicano style, also known as cholo/a.7 Chicana women were some

1 Bush, “The History Of Bandanas: From Practical Necessity To Fashion Statement,” Dec. 19, 2024.

2 “Mexico’s Original Cowboys: History of the Vaqueros of Texas,” Amigo Energy, Jan. 4, 2023.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Jarmoo, “What culture wears bandanas,” Aug. 8, 2023.

7 Sowmaya Krishnamurthy, “Cholo Style,” Oct. 6,

of the first to turn the functional usage of bandanas into fashion statements. Since the mid-1900s, Chicana women have been wearing bandanas as shirts, headbands and scarves, creating stylish symbols of pride in their origins and culture.8

2023.

8 Barbara Calderón-Douglass, “The Folk Feminist Struggle Behind the Chola Fashion Trend,” April 13, 2015.

This history ties back into the oppression Mexican-Americans have faced in the past and still face today. Born out of the discrimination they were subjected to, Chicano people portrayed pride in their shared identity through

this style. They intended to show how unashamed they were of their heritage.9

“To me, a chola is the epitome of beauty, style and pride with a badass, take-no-shit attitude,” said Hellabreezy, an Oakland-based model and modern chola.

The underlying discrimination and ignorance of Chicano culture was ultimately a factor in creating the cholo/a style. This fashionable liberation created a sense of belonging that Chicanos weren’t able to find in other spaces.

While modern-day fashion has taken to bandanas gracefully, many forget their origins and cultural ties when they wear one. All different types of people find ways to include the small piece of fabric into outfits, adding a lively element to something otherwise plain. When we see this accessory at music festivals, layered under baseball caps and on the shelf at H&M, it’s important that we acknowledge the bandana can be worn by all, but it was assimilated into its role today through Chicano culture.

9 Ibid.

When you think of country music, your first thoughts are likely of cowboy hats, whisky and pickup trucks. But the genre used to be defined by its outspokenness about the systemic issues affecting disadvantaged communities.

Some of country music’s most famous and prolific musicians, like Johnny Cash, were especially vocal regarding their thoughts on issues such as war, Native displacement, prison reformation and racism.1 Willie Nelson, another luminary, is known for stirring up controversy with his antiwar, pro-immigration and generally left-leaning stances.2 So, when did the activism at the core of country music’s history turn into endless songs about cawing eagles and American “greatness”?

to Die” and “Queen of the Rodeo.” In “Hope To Die,” Peck sings, “Take me back to the time I was yours and you were mine, I had to whisper because you liked it that way.”6 Like in many of his songs, he expresses the struggles of queer people and the secretive nature they often have to conduct their relationships in.

His music spreads awareness on how many queer people must look for an escape from rural ideations or hide their sexuality altogether just to feel safe. In an overt celebration of his sexu-

roles forced onto her by her small town. She expresses the culture shock she faced moving to Milwaukee, while also acknowledging the freedom it gave her.

Written by Sarah Berendes

The answer lies in one of the great American tragedies. Following 9/11, many popular country artists called for unity, but the tone of the music had changed3. The songs were no longer anti-war; rather, they encouraged war as revenge for the attack that had ensued.4 Across the genre, it was no longer the norm to be outspoken against the government.

Famously, “The Chicks” were exiled from country music for years after they spoke out against some of George W. Bush’s decisions while in office.5 The shift in country music led to a stagnation in the topics and opinions “allowed” to be held in the songs. This informal rigidity on what can and cannot be written persisted for decades.

Within the last few years, we’ve seen the debut of artists returning to the genre’s roots through both their writing and inherently through their identities. Among the most famous is Orville Peck. Debuting in 2019 with his album “Pony,” Peck helped to redefine the genre with songs that highlight the queer experience, such as “Hope

1 Em Casalena, “5 of Johnny Cash’s Greatest Protest Songs,” American Songwriter, July 14, 2025.

2 Sterling Whitaker, “The Most Politically Outspoken Country Singers,” Taste of Country, August 22, 2024.

3 Joseph Hudak, “9/11 Country Songs Pushed Patriotism to Grieving, Angry Listeners,” RollingStone, Sept. 10, 2021.

4 Meg Richards, “The Resonating Echos of 9/11 in Country Music,” The Beacon Magazine, April 17, 2024.

5 Jennifer Gerson, “The Chicks Were Silenced Over Politics. 20 Years Later, Those Lessons Shaped Country Music’s New Generation,” The 19th, March 10, 2023.

ality and country music, he was chosen to make a country-style cover of Lady Gaga’s 2011 title track, “Born This Way,” for the album’s tenth anniversary.

Celebrating queerness through country is not exclusive to artists within the genre. Though she is not primarily a country singer, Chappell Roan explores themes similar to Peck’s in her music. Recently, she released her country-pop single “The Giver.” The upbeat, innuendo and banjo-filled hit was written about the artist’s lesbian relationship. Roan may not be a frontrunner in the genre, but simply putting out a country song expressing these ideas makes a statement that country is, and always has been, for everyone.

Another artist spurring a return to country’s roots is Wisconsin native Trixie Mattel. Mattel is a Native American drag queen who has used her platform for a variety of ventures, including winning RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars, starting her own makeup brand and a country music career.7 Growing up in rural Wisconsin, Mattel faced heavy backlash for her sexuality from her community and the adults in her life. The name “Trixie” is the derogatory name her stepfather called her growing up when she acted too flamboyant, which she then reclaimed to launch her drag and later music career.8 In her song “Little Sister,” she explores the gender expectations and

6 Orville Peck, “Hope To Die,” track 11 on Pony, Sub Pop Records, 2019.

7 Liam Hess, “How Trixie Mattel Went From Drag Queen to Country-Pop Superstar,” Vogue, July 19, 2022.

8 Stephanie Sala, “The Truth Behind Trixie Mattel’s Drag Name,” Nicki Swift, July 1, 2022.

Some country artists already have an established audience when they come out. The greatest example of this is T.J. Osborne of the Brothers Osborne. Coming out recently in 2021, Osborne became the only openly gay country artist signed to a major label.9 Following his announcement, the musical duo released a heartfelt song titled “Younger Me” in which they declare, “Younger me…. Didn’t know that being different really wouldn’t be the end.”10

Anyone who is queer understands the fear you feel when you realize you are “different.” No one wants to be perceived as different, especially in rural areas where it is even more stigmatized. T.J. Osborne sharing his experience with his largely country audience is a step toward acceptance where it may not typically be found.

Perhaps the most recent mainstream queer country media is Tyler Childers’ “In Your Love” music video. This video depicts two gay coal miners in Appalachia and their relationship before one of them fell victim to black lung, a disease that has affected many coal miners.11 While initially the music video may seem to be social commentary on queer people themselves, diving deeper into the video can show that the setting and disease were extremely intentional choices. While the main subjects of the video face homophobia, they’re still able to live a happy life together. The true heartbreak of the video comes from a disease that anyone who worked in the mines could’ve gotten.

The expression of hardships is what has been at the very core of the genre from the beginning. At the end of the day, we all work hard, we all love and we all lose that love at some point. If this is a collective experience, why shouldn’t queer artists be spurring country music back to its roots? We struggle, love and repeat, just as everyone else.

9 Sam Lansky, “T.J. Osborne Is Ready to Tell His Story,” Time Magazine, Feb. 3, 2021.

10 Brothers Osborne, “Younger Me,” track 13 on Skeletons (Deluxe), EMI Nashville, 2021.

11 Tyler Childers, “In Your Love,” directed by Bryan Schlam, July 27, 2023, Youtube.

Written by Talia Horn, Arts Editor |

Graphic by Natalie Khemelevsky |

Loyal, conformist, safe, judgmental, nostalgic: The ambiguous Americana small town. High school football teams running onto the field and children riding their bikes past faded red barns and one-block “downtowns.” Is it youth, community and suburban bliss? Or, is it a prison of traditions trapped in time?

The American small town is portrayed just as confusingly on our screens, often shown as something to both escape and yearn to come back to. In many iconic TV shows and movies, these stereotypes seem to shapeshift, leaving the audience with a clear question: What is small-town “Americana”?

Instead of shying away from these inconsistencies, the series “Friday Night Lights” (2006-2011) embraced them. The show paints the scene of remote, football-crazed Dillon, Texas. The town, inspired by Odessa, Texas, is a place as full of opportunity and community as it is of division and limitations.

In the pilot, football star Tim Riggins yells during a bonfire toast, “Texas Forever!” a proclamation met with raised beers and smiles. As though the fire is crackling before you, warming your face, this fictional place begins to feel like home. But it’s not without its faults.

Dillon is also a town riddled with racism, poverty and close-mindedness. Tyra Collette, born and raised by a single mother in a lower-class family, was taught repeatedly that her value came only from her beauty. After enduring a string of her mother’s abusive boyfriends, belittling from her own boyfriend and laughter at her notions of going to college, Tyra dreamt of escaping Dillon. The heart of small town Dillon was overshadowed by the haven University of Texas-Austin represented. After fighting and scraping by, her story ends driving out of Dillon to live a fuller life in Austin.

However, when Tyra returns for a few episodes in the final season, she brings a new perspective. As the parade of football pride drives down the main road the night before the championship game, Tyra admits that Dillon is “kind of like this drug” that always manages to pull you in.1 The show’s

1 “Texas Whatever,” Friday Night Lights, created by Peter Berg, Season 5 Episode 12, Imagine

well-known motto, “Clear eyes. Full hearts. Can’t lose,” captures the intoxicating energy of the multifaceted small Texas town.

Taking a different tone, the film adaptation of a Stephen King novel, “Stand By Me” (1986), tells the story of four

Television, February 12, 2011.

young boys who adventure to find the body of a missing kid in Little Rock, Oregon. Unlike “Friday Night Lights,” which takes place solely in Dillon, the majority of the plot happens just outside the border of Little Rock.

Amidst joyful mocking and playful arguments, the boys explore their internal struggles and secret dreams. The main character, Gordie Lachance, is a bright writer from a middle-class family mourning his older brother’s recent death in a car accident. His family’s grief-stricken state reflects his own feeling in the town: stuck.

The coming-of-age film is a story of friendship between Gordie and his best friend, Chris Chambers, a charismatic trouble-maker from a violent

family. Chris believes his reputation as a “bad” kid in this town will hinder him from having a successful life, because for him, success means getting out of Little Rock. Instead, he channels that ambition into Gordie, encouraging him to use his writing skills as a ticket to freedom to save himself from the Little Rock oblivion to which Chris feels destined.

As the boys return at the end of the film, the town seems to feel “smaller” with less to offer. The other two boys in the group wind up in monotonous jobs and lives mirroring what Chris feared for himself.

Before Chris’ tragic death, he and Gordie find happiness as a lawyer and writer, a fate only possible after they

left. “Stand By Me” represents the Americana town as one of limitation, where talent is an escape plan and home a springboard in one’s life.

Not every negative portrayal of smalltown life sends the same message. The 1984 classic “Footloose” plays with the idea of the Americana ideal. The movie’s premise follows the McCormack family’s move from Chicago to the strict religious town of Bomont, Utah, with one distinct quality: dancing is illegal.

Bomont’s moral representative, Reverend Moore, claims that the town has a family-like community that gives it its essence – a common, positive trait emphasized about small towns. But, protagonist Ren McCormack sees the possibility of what the town could become, and is determined to make it so.

Newcomer Ren deeply believes in the magic that dance and self-expression bring to a community. Inspired by Ren’s passion, which had spread amongst the town’s teenagers, the Reverend loosened his reins, choosing to trust the youth to explore and discover themselves instead of forcing his own values on them. The final scene is set at the high school’s senior dance, filled with joy, color and music.

Footloose critiques the American small-town mindset while raising hope that not all may be stuck in their ways. Bomont lived up to its fullest potential when it welcomed change. It does not discredit the close-knit community nor its good people and intentions; rather, it shows the future small-town Americana could have if it opens its iron fist ever so slightly to invite new opportunities.

The small-town Americana setting is a complicated, contradictory experience different for every person, as is reflected in popular media. Our job as an audience is to absorb these contradictions to recognize the beauty tangled with its inherent flaws. We must appreciate the community and culture that exists in real places scattered around the country, but never forget to see where we can evolve. With Tyra Collette, Chris Chambers and Ren McCormack in the back of our minds, we must remember to always look to the future.

Written by Lily Kocourek | Photography, Shoot Direction & Styling by Sofia Wells |

Modeled by Kelly Chi & Arshiya

Singh

She doesn’t simply enter the bar — she makes an entrance. Boots hit the floor, eyes scan the room and every head turns. She’s got flushed cheeks, a glossed lip and a leather jacket sliding off one shoulder. She’s not here for a whiskey neat (though she’ll take one). She’s here to be seen.

The saloon siren has arrived.

These aren’t your old school Western girls. They are part flirt, part outlaw. Women who use fashion to transform, tease and tell a story. It’s about persona — a curated moment that whispers, “she’ll dance like she’s yours, laugh like she means it, then disappear before closing time.”

And no, she’s not at a honky-tonk in Nashville. She’s at your local dive. A downtown club. Maybe even the rooftop at the Double U. Because the Wild West isn’t just a place anymore; it’s a vibe for after dark.

Western fashion has always carried a bit of danger in its stitching. Its roots run deep into the mythos of the American frontier, a time and place where women like Annie Oakley and Etta Place lived outside the boundaries of what was expected. Etta, the mysterious companion of the outlaws, was elegant in gunpowder form, riding with the “Wild Bunch” in silk blouses and wide-brimmed hats, her presence as disarming as her aim.1 Then there was Annie, the origi1 Ciaran Conliffe, “Ethel ‘Etta’ Place, Western Women of Mystery” Headstuff,

nal sharpshooter sweetheart, who dazzled crowds with her precision and poise.2 Her fringed skirts and custom-made costumes weren’t just performance — they were power, turning femininity into spectacle and strength.

These women blurred the lines between myth and reality, showing the world that in the West, danger could come dressed to kill.

It’s a look co-signed by fashion’s most watched. Kendall Jenner wears her cowboy boots with barely-there dresses and backless halters. Bella Hadid turns vintage Wrangler into a night-out staple. Suki Waterhouse lives in fringe jackets, sheer slips and tousled hair like she just stepped off a midnight ride.

Western glam works because it walks the line between structure and seduction. It’s the contrast of rough textures with soft silhouettes. It’s that untamed energy in a polished package. And most importantly, it’s a style that lets you step into character — one that’s bold and a little bit dangerous.

But this isn’t just dress-up. It’s a transformation.

Because this girl? She’s not just going out — she’s showing up for herself. She’s reclaiming space. She’s playful, yes, but with an edge that says she knows exactly what she’s doing. She embodies a specific kind of empowerment: one rooted in self-definition. She doesn’t need to be rescued; she’s the one riding off on her own terms.

So, how do you become her?

You don’t just throw on clothes. You step into the role.

June 2, 2023

2

Piece by piece, layer by layer, with each choice dripping with intention.

Start from the bottom up, babe.

First, the boots. Weathered leather, snakeskin or suede that sounds like confidence with every step. They’re the foundation of your story, so find a pair that speaks to you.

Then, the legs. A sleek maxi or leather mini that hugs every curve — something that moves with you, not against you. It’s the kind of piece that invites eyes but never begs for attention.

Up top, mix softness with grit. A lace corset and vintage tee tied up, or a silky camisole with a touch of edge. It’s the contrast that keeps them guessing.

Throw on that jacket, preferably something a little worn, with a story etched in every crease. The kind you don’t mind slipping off when the night heats up. Opt for thrifted leather or vintage fringe — they bring spunk and flair.

Sometimes the best additions are the ones you grab at the last minute: a chunky gold ring from a flea market, a turquoise bangle from your grandma or a wide-brimmed hat grabbed on a whim. And don’t forget the lip gloss, because a little shine can seal the whole look.

With this look, you’re not just dressed — you’re ready to own the night to step into a role that’s equal parts wild and glamorous. Confidence is your best accessory, and once you have that, everything else falls into place.

So next time someone texts “You coming out tonight?”

Text Back: “Saddle up, Babe.”

Centuries of colonization have silenced Native voices, but a new generation is determined to reclaim them

Written by Tessa Almond, Lifestyle Editor | Graphic by Rayyan Bhatti, Creative Director |

Every two weeks, an Indigenous language dies.1 We are living in a time of language extinction, and it’s happening right under our noses. There were originally 2,000 distinct Indigenous languages spoken in the United States, and only about 115 remain today, over 99% of which are endangered.2 The erosion of Indigenous language stretches beyond just a loss of communication; it also threatens the survival of Indigenous culture, traditions, memories and identities.

This decline first began with European colonization in the early 1500s, when Indigenous languages were flourishing across the Americas. Native communities were quickly torn apart by violence and land seizures as the French, Spanish and Portuguese took control. This was later intensified by forced assimilation practices, particularly with the establishment of boarding school policies in 1819.3 Under these policies, the North American government adopted the slogan “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” calling for a cultural genocide through the forced separation and assimilation of Native children into white-established boarding schools.4

By 1926, nearly 83% of American Indian school-age children were ripped away from their rightful homes and taken to boarding schools.5 These schools banned anything that represented traditional cultural practices such as clothing, languages and personal belongings. Children also suffered physical and sexual abuse in this environment.6 Unfortunately, many of the children never returned home, and they have yet to be accounted for today.

1 Katalina Toth, “The Death and Revival of Indigenous Languages,” Harvard International Review, Jan. 19, 2022.

2 Rebecca Nagle, “The U.S. Has Spent More Money Erasing Native Languages than Saving Them,” High Country News, Nov. 5, 2019.

3 “US Indian Boarding School History.” The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

The lingering effects of colonization and forced assimilation continue today. Many Indigenous communities have become reliant on federal programs and services in healthcare, housing and education, all of which operate in English. This comes as a result of treaties, executive orders and other legal bases.7 This reliance on English, in combination with the chronic underfunding of Native schools and language programs, has pushed Indigenous languages so far under the rug that they are no longer needed in formal settings.8 As a result, most Native languages today can only be passed down generationally from small groups of elderly community members.

For many Native people, language is an essential part of their identity, history and pride. Its disappearance fractures the passing down of generational knowledge and Native heritage. Oral traditions and ceremonies, for example, are a key part of this identity that is meant to be passed down from generation to generation, but there are simply not enough fluent speakers to sustain these practices.9 This threatens the cohesion of entire tribes who have created community through the retelling of stories and songs in their Native languages. Without it, many Native Americans suffer a painful disconnect from their heritage and community members. There is tangible evidence of this; often called “intergenerational posttraumatic stress disorder,” there have been increased rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation within struggling Native communities as a result of both contemporary and historic traumas.10

7 Donald Warne and Linda Bane Frizzell, “American Indian Health Policy: Historical Trends and Contemporary Issues,” U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2014.

8 “Native American Languages Must Be Saved from Extinction,” Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, July 2023.

9 Les B. Whitbeck et al., “Depressed Affect and Historical Loss among North American Indigenous Adolescents,” U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2009.

10 Ibid.

But there is hope for the survival of Native languages. Alaina Tahlate, a member of the Caddo Nation in Western Oklahoma, is part of the younger generation fighting for Native American language preservation. She is currently learning Caddo, the official language of the Caddo Nation, of which there are only two fluent speakers in the world, both over 90 years old. She first started learning Caddo from her grandparents, who were both native speakers. When she discovered the language was going extinct, she proposed language classes via Zoom and documented Native histories, stories and songs. Her efforts have been met with overwhelming support from the community, and she’s encouraging other young Natives to do the same.11

“Our language encodes so much information about our history, our spirituality, who we are, our cultural values,” Tahlate says. “When we’re able to preserve our language, we’re able to preserve other aspects of our culture as well.”12

In addition to efforts within tribes, there has also been an overwhelming number of projects to revitalize these languages at both the state and national levels. Institutions like the National Museum of Natural History, the Cherokee Nation Language Department and the Indigenous Languages Decade have all implemented programs dedicated to spreading awareness on the subject. Several educational institutions, such as the University of Arizona, Miami University and the University of Alaska Fairbanks, have contributed to research projects, training programs and the funding of language classes for endangered Indigenous languages.13

11 Avery Keatley and Scott Detrow, “The Race to Save Indigenous Languages,” National Public Radio, Feb. 25, 2024.

12 Ibid.

13 “Indigenous Language Research Guide: Revitalization Projects and Centers,” Harvard Library Research Guides, Feb. 20 2024.

On the federal level, in December of 2024, the White House Council on Native American Affairs released the 10-Year National Plan on Native Language Revitalization. According to the US Department of the Interior, the document outlined a “comprehensive, government-wide strategy to support the revitalization, protection, preservation, and reclamation of Native languages” with a focus on languages across the continental United States, Alaska and Hawai’i.14 The $16.7 billion program has supported the creation of hundreds of Native language immersion schools, school programs for youth and networks of educators committed to Native language revitalization. Its effectiveness on preserving languages has yet to be determined, but it is a massive step in the centuries-long fight to save Indigenous languages.

The fight for Indigenous language preservation is far from over, but it’s a fight that is generational. The silencing of Native American voices has been too deliberate and too destructive to ignore — but it’s not too late. With increased awareness, funding and passionate efforts from within tribes, Indigenous languages can flourish once again, ensuring that Native identities thrive in the generations to come.

Photography by Rayyan Bhatti, Creative Director & Paige Valley |

Shoot Direction by Sydney Alston, Shoot Direction Lead, Paige Valley & Rayyan Bhatti | Styling by Jessie Wang, Styling Lead & Sydney Alston | Modeled by Lily Meinertzhagen

Exploring the history of classic Southern dishes and their ties to community and connection

Written

by

Allie Ketelsen

| Graphics by Amelia Tingley, Illustration and Design Lead |

There’s a special kind of warmth that comes with stepping into a Southern kitchen. A blend of buttery biscuits, inviting arms and stories to tell are guaranteed to greet you at the door. The idea of Southern comfort food isn’t just about the food and its beloved reputation; it’s about the ties to community and history. While known for its simplicity, flavor and heartiness, the roots of Southern food go much deeper.

Early English settlers in America relied on local ingredients like leafy greens, beans and corn. During the Transatlantic Slave Trade, enslaved Africans introduced cooking techniques and spices, foreshadowing the Southern classics we know today. Combined with European immigrant influence, these flavors evolved into a new and diverse genre of dishes.1

1 “The Evolution of Southern Comfort Food in Modern Dining,” Barbara Ann’s Southern Fried Chicken, Dec. 20, 2024.

Beyond representing regional cuisine, Southern comfort food symbolizes unity. During the Civil Rights Movement, activists gained strength and community through shared meals. It symbolized the struggle for equality and a push to fight.2 This isn’t just a food group; it’s a representation of America’s foundations and the strength of diversity in the midst of uncertainty and danger.

2 Ibid.

There is so much power in the way food can bring people together. It acts as a universal connector, bridging the space between different perspectives and lived experiences. Today, food continues to play an essential role in community building through potlucks, barbecues, tailgates and more.

In the American South, “taking a dish” refers to a common gesture of preparing a meal for someone undergoing hardship to support and keep them on their feet.3 It honors tradition, spreads kindness and brings awareness to its sacrifice.

Shared food is also a healing method. It connects you to the roots of dishes you’re eating, the people around you and the memories associated with mealtime.4 What is usually a necessary task turns into a cherished moment.

Sometimes the best recipe for comfort on a chilly fall evening is a warm, home-cooked meal or dessert, and some say the best have Southern roots. What should we be making this cold season to keep warm? Here are a few tips to ensure your dish has guests going back for seconds (and thirds).

Mac & Cheese: Grate your own cheese!5 Adding sour cream enhances the flavor profile by adding acidity, similar to the effects of lemon or vinegar.

3 Zuzana Paar, “Understanding the role of community in Southern food culture,” Southern Supper Club, Dec. 12, 2024.

4 Ibid.

5 Kelly Wildenhaus, “Southern Baked Macaroni and Cheese,” The Hungry Bluebird, Oct. 29, 2019.

Fried chicken: Don’t rush it!6 Good fried chicken takes time. A cornstarch and flour mixture will make the chicken extra crunchy. Fry it in peanut oil to prevent flavor loss and immediately sprinkle it with flaky salt after frying.

Peach cobbler: Canned peaches work, but fresh peaches are best!7 Peel the peaches whole before cutting them. To avoid runniness, cornstarch helps thicken the filling as it bakes. After baking, give the cobbler 20-30 minutes to cool, allowing the fruit juices to set.

Today, Southern classics are getting a modern twist. We’re seeing an emergence of innovative takes on southern dishes that appeal to broader audiences and push culinary boundaries. Many recipes have taken flight on TikTok, like the viral Tini’s Mac n Cheese. There’s also been a popularization of different chain restaurants like Dave’s Hot Chicken, Raising Canes and Texas Roadhouse. Healthier options, like plantbased recipes or air-fried dishes have also gained traction.8 Global fusion recipes are also taking flight, like Southernstyle tacos or Cajun sushi rolls.9 These takes on traditional Southern meals combine unexpected elements from different cultures, creating an entirely new genre of cuisine.

With a history of simplicity, it’s no wonder people are finding creative ways to reinvent classic Southern meals. Still, it’s hard to top a timeless family mac and cheese recipe or a 5-ingredient cornbread; not much beats relying on our roots.

6 Brandie Skibinski, “The Best Southern Fried Chicken,” The Country Cook, Feb. 17, 2021.

7 “Fresh Southern Peach Cobbler,” Allrecipes, June 24, 2025.

8 “The Evolution of Southern Comfort Food in Modern Dining,” Barbara Ann’s Southern Fried Chicken, Dec. 20, 2024.

9 Ibid.

Few fabrics have traveled as far and meant as much as denim. From the gold mines to runways, denim has truly stitched a story of rebellion, reinvention and revelation. Denim has gone through a modicum of different styles and wear throughout history. As a result, the material evolved from workwear in the West to a global fashion wear trend. The fabric itself symbolizes resilience, a reliable staple, rebellion and cultural change.

Denim has a versatile and long spanning history. The origin of the word is derived from the French word “serges de Nîmes,” which at the time was a fabric specifically derived from the town of Nimes in France.1 At the same time, there was a fabric known as the “jean.” The differences between the two? “Denim” was made from one colored thread and one white thread woven together, whereas “jean” was made from solely two threads of the same color.2 In 1792, some of the first technical sketches were made for weaving denim.3 Creating denim involved the cultivation of cotton, with the weaving of a blue fabric made from indigo.

Eventually, we see the first curation of the word “denim” in 1864, published in Webster’s Dictionary as “a coarse cotton drilling used for overalls, etc.”4 This definition stayed into the 1900s of being a fabric used for durability and reserved primarily for work clothes, specifically worn for hard labor.5

Around the beginning of the 20th century, the fabric was rebranded in Hollywood films. That would be the benchmark for the romanticization of nostalgia in Western influence. There was an emergence of biker gangs decked out in denim post World War II, and Hollywood latched onto this and emphasized the rebelliousness of the staple.6 Eventually, denim

1 Lynn Downey, “A Short History of Denim,” Levi Strauss, 2014.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Michael Martin, “How Denim Evolved to Become an American Wardrobe Staple,” NPR, Feb. 5, 2022.

6 Ibid.

Stitching a story through the decades

Written by Isabella Rotfeld |

Photography by Indu Lekha Konduru, Photography Lead |

Shoot Direction by Lila Robinson & Bethany Ehlenbach |

Styling

by

Shira Malitz, Styling Lead | Modeled

by

Claire Neblett & Soyer Foley |

manufacturers worked to change this image of the fabric into a positive one.7

Today, denim is still at the forefront of style and continues to shape and create impact in the fashion industry. Denim is represented in a multitude of styles, from the casual approach of day-to-day, to the runway chic repurposed denim. A great example of this is Levi Strauss and Co. Their brand is very central in the denim industry, utilizing marketing strategies from their workman era to the emergence of casual denim. Brands like Guess and Ralph Lauren even have corners on the “luxury denim” market. This can be seen in the popularized Tom Ford by Gucci denim of 1999, holding a price tag of $3,000 at the time.8

We see all these emergences of different styles in which denim is worn today. Styles such as the low rise, bootcut, flare pants, mom jean and more have all had their moments. Additionally, these designs revisit past fashion also seen in a variety of clothing, such as the denim jumpsuit — worn during World War II by women in the factory — or the lavish denim dress, designed as a fashion statement outside of work clothing.9

So, how has the West influenced the denim we see today? The West has been a greatly inspirational area for the creation of denim workwear and the continued appearance of it in cowboy romanticization.10 The elevation of cowboy symbolism furthered the fabric’s ability to showcase independence and toughness. It also brought about the image

7 Ibid.

8 “Denim: Fashion’ Frontier,” FIT NYC, Dec. 1, 2015.

9 Ibid.

10 David Shuck, “A Cinematic History of Denim,” Heddels, April 29, 2013.

of masculinity at the time of its emergence in the 20th century, and the attachment to the image of the “heroic cowboy.”11 As Western films took off, people wanted to match their on-screen idols by wearing the iconic denim outfits displayed on the screens.

One of the first major players we see in this influence is the actor John Wayne in his iconic Levi’s 501s. His attire, worn in the 1939 film “Stagecoach,” had every boy gunning to copy their favorite on-screen actor.12 James Dean was another large influencer in 1954. His attire in “Rebel Without a Cause” portrayed the classic grungy biker aesthetic of the time, inspiring many teenagers to replicate that look with their own take on the aesthetic.13 Not to mention, who can forget the Elvis Presley “Jailhouse Rock” all-denim fit? This iconic look inspired Levi’s to release an all-black jean, seeing the potential for the new market in the industry.14

Today, we can observe Western influence on denim through the image of country music and the overall country aesthetic. When thinking of the theme “country,” there is almost always the image of some sort of denim that comes to mind. On top of the durability that many farmers still rely on in denim, it has become an aesthetic seeped in American culture today.

Denim means something different to everyone. It’s a fashion statement, a symbol of independence, an idea of reliability. From cowboys of the West to the American closet staple, denim has truly transformed the way we see its fabric.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid,

14 Ibid.

Can you embrace the aesthetic while rejecting the sentiment?

Written by Josie Purisch | Photography by Hannah Byma | Shoot Direction by Kavya Kanungo | Styling by Kate Pennoyer | Modeled by Kavya Kanungo, Kate Pennoyer & Zoe

It’s all so romantic: The girl in the tiny red and white gingham top, faded low-rise jean shorts, mud-covered cowboy boots and the perfectly imperfect Coca Cola can curls. She’s probably either coasting her red vintage convertible down quaint country roads or fighting to finish her softserve before the sun threatens to drag it down her arms. She is rough and feminine, independent and humble, effortless and home-grown: the “perfect” vintage Americana girl.

This image is so recognizable because it’s the aesthetic that Americans were raised on and the life we were taught to crave amidst the fast-paced culture that typifies the 21st century. Shows like “The Brady Bunch” that center a picture-perfect family and ignore the existence of any social issues1 can trick a naive viewer into believing the illusion of American life they painted.

As many of us grow tired with pieces of our modern lifestyles, we look back to this aesthetic and yearn for the simple life that old Hollywood movies and photographs promised once existed. But Americana wishes to create a memory of an all-glorious America, one that has never been. The modern world appears entirely complicated in comparison to the past’s guise of “simplicity,” leading us to romanticize a time that was actually typified by discrimination and exclusion.2

This begs the question: Does an aesthetic that relies on nostalgia and exclusivity have a place in modern culture?

The Americana aesthetic originated in the mid-1900s as people romanticized the rugged individualism of the

1 Erin Blakemore, “The 'Queer Innocence' of the Brady Bunch,” JSTOR Daily, October 23, 2018.

2 Douglas Steven Massey, “The Past & Future of American Civil Rights,” Daedalus, 2011.

Western expansion era.3 The workwear that is emblematic of that era, paired with the polka dots, bright reds and short shorts from the 50s, 60s and 70s, is constantly revived in modern media.

Artists like Lana Del Rey capitalize on this all-American stereotype. Her warm filtered photos, cherry-red lipstick and motifs that would make Uncle Sam proud reek of American nostalgia. And as Del Rey smokes a cigarette and laughs with her picture-perfect family in her memory-like music video for “National Anthem,” I almost feel patriotic.

3 Aurélien, “Americana Style: How It Evolved Into a Modern Statement?” Drover Club, June 12, 2025.

While it’s tempting to reach for our Daisy Dukes and embrace the stars and stripes as Del Rey prompts us to tell her she’s our national anthem, we must remember the message that our fashion statements convey. If we relinquish nostalgia to focus on accountability and push the boundaries of who can be the American it-girl, we may be able to steal bits and pieces of the vintage Americana magnetism by reclaiming the fashion trend.

Nostalgia, with its focus on glorifying the past, is far different from hope, which remembers the struggles of the past and aims to fix them for a better future.

We can keep the rugged blue jeans and the palette borrowed from the American flag in our wardrobe while rejecting the notion that these symbols of “Americana” only look good on a narrow group.

The Americana aesthetic is about values: The independence, grit and self-sufficiency that American life had promised to foster remain at the core of the aesthetic, and are seen in the details of the look.

The all-American girl’s low-rise jean shorts are worn because she works tirelessly to support her family, her cowboy boots

are mud-covered because she harvests her own food and her hair is messy because repairing her vintage cherry-red convertible has undone the look she so carefully put together in the morning. She knows fashion, yet she accepts the blemishes to her look to maintain her independence. This imprint of American values onto the threads of our clothes is what makes the Americana aesthetic undeniably magnetic.

Yet the reward of these values was only afforded to an exclusive group.4 It is only when we stop pretending that these values were fulfilled in the past and extend the narrative of who can be a recipient of the American dream that we can bring the vintage Americana aesthetic into the future.

4 Kimberly Lawson, “An American Dream for Some, but Not for All,” Vice, May 5, 2017.

Written by Adelaide Taylor |

Graphic by Elise Daczko |

In the wake of the 2024 presidential election, a new wave has descended upon America – making conserva tism “cool” again.

Starting in the mid-2010s, there was a heightened awareness around social issues like the #MeToo and the BLM movement that lasted until around 2020, when adopting “woke” views peaked in America, according to The Economist. Since then, the decline has been apparent.1

boy boots, American flags and denim on denim (ironically, called Canadian tuxedos). While it has been incredible to witness Black artists like Beyoncé, Lil Nas X and Shaboozey carve their own space in the country scene, as Kyndall Cunningham argues in a Vox article, this rising push and popularity of country music is correlated with the return of masculinity, morality and whiteness that we often see associated with conservative values. 9

By flocking toward this Americana aesthetic, we may creep closer to some outdated ideals. The rise of “trad wife” content online reinforces antiquated notions of gender roles, with women in the submissive and obedient position, and the popularization of modest dressing seems to place a taboo on women’s bodies.

Leading up to Trump’s election, the Republican Party complained of a “woke government” and blamed it for America’s failings, according to The Economist.2 Whether Trump’s win is the cause or the symptom, political trend cycles have shifted right and are mirrored in popular culture.

America has a long history of political attitudes being reflected in our pop culture trends. In the 1970s, disillusionment with social institutions inspired the peace-mak ing, anti-war stances that bled into music, boosting folk and psychedel ic rock sounds. As an act of rebellion, women would craft their own clothing, thus giving birth to the tie-dye and crochet we associate with the 70s hippie movement.3 90s grunge served as a rejection of capitalist consumerism with its distressed, thrifted clothes, moody makeup and angsty punk music.4 Around 2020, we saw a rise in statement-wear, such as the trending “it’s cool to care” hoodies, along with an emphasis on socially-conscious and sustainable shopping that coincided with the times’ attitudes.5

with more country music artists.6 While these are trends that can be separated from political beliefs, we cannot ignore this concurrent rise with right-wing ideation.

“We’re back to a conservative-coded social currency,” Ning Chang of Shado says.7

Singers like Lana Del Rey, Beyoncé and Post Malone have all gone country despite their musical history in other genres.8 Country music has seen booming popularity, along with noticeable fashion trends like cow-

This selling of country conservatism does not just center around misogyny; it continues to uphold ideals of white supremacy. Cowboys as a historical figure spawned from ideas about Manifest Destiny and of expansion against “savage” forces.10 Simultaneously, it is often overlooked how, despite being popularized by white people, Western fashion has deep roots in the Indigenous culture that was established centuries prior.11

“Just as our politics and society stifle political diversity and grow more conformist, our culture does the same by coalescing around country,” Ning

As far as what the future looks like for cowboy culture in America, I think we will shortly see the pendulum swing once more. In our modern era of social media and fast-paced trend cycles, I think people will quickly become fatigued by this aesthetic’s social subtext. Ideally, the push for inclusivity will overhaul this current wave of regression, and we can pay homage to our history without antiquating our current political climate.

1 “America is Becoming Less ‘Woke,’” The Economist, Sep. 19, 2024.

2 Ibid.

3 Cat Broughton, “Radical Threads: How Politics Shaped 1970s Fashion Trends,” Medium, Jul 20, 2023.

4 Christina Pérez and Boutayna Chokrane, “How the Grunge Aesthetic Stands the Test of Time,” Vogue, Oct 28, 2024.

5 Fiona Scott, “2020’s biggest fashion trends

reflect a world in crisis,” CNNStyle, Dec. 30, 2020.

6 Ning Chang, “County is back–is conservatism next?” Shado, Jan. 6, 2025.

7 Ibid.

8 Kofi Mframa, “America’s shift right should be no surprise. Country music resurgence warned us,” USA Today, Nov. 22, 2024.

9 Kyndall Cunningham, “Want to understand why Trump won the election? Look at pop culture,” Vox, Nov. 15, 2024.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ning Chang, “County is back–is conservatism next?” Shado, Jan. 6, 2025..

Frida Kahlo’s unibrow is an iconic symbol in the art world, representing her fame as one of Mexico’s greatest artists. But her legacy goes far deeper than this. What many people don’t know is that she was a queer, disabled woman who boldly challenged societal norms through her art. Through a lens of feminism and equity, Frida helped shape the fight for queer and marginalized women’s freedom.

Frida was born in 1907 in Coyoacán, Mexico City.1 Her experiences in early childhood were pivotal to her art career. She fell ill with polio at the age of 6, leaving her bedridden for nearly a year. The effects of the disease continued into her adult life, causing her right leg and foot to grow much thinner than her left. Frida began wearing long skirts to cover her limp, which later became her signature style. Despite her battle with Polio, she still played a variety of sports like soccer, swimming and even wrestling, which defied social norms for women at the time.2

Her misfortune did not stop with her disease. At just 18 years old, she was also severely injured in a bus accident.3 Severe spinal injuries left her with chronic pain for the rest of her life. As a form of therapy, Frida spent her time in recovery making striking self-portraits.4 Little did she know the hobby would turn her into one of the most iconic artists of the 20th century.

Frida famously married artist Diego Rivera in 1929, whom she met while attending the renowned National Preparatory School.5 Together, they

1 “Frida Kahlo Biography,” Frida Kahlo.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Marisol Medina-Cadena, “Inside Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s Life in San Francisco,” KQED Inc., Dec. 3, 2020.

moved to San Francisco, where Frida began to make a name for herself as an artist, and her distinctive style caught the attention of San Franciscans. In addition to making more self-portraits, Frida took inspiration from the sculptors and artists she met there and began incorporating elements of surrealism into her art.6

She also became close with horticulturist Luther Burbank, who inspired her to play with imagery of roots, plants and hybrid bodies to explore themes of life and death. Having grown up in Mexico, this theme was already familiar to her, but it was in San Francisco that she made the style her own.7 She suffered through lifelong physical pain, multiple miscarriages and the death of her mother, all of which fostered her interest in the relationship between life and death.8 She frequently painted skulls, ofrendas (altars), bleeding wounds and botanical regeneration. Kahlo’s imagery of life, death and pain is well recognized, yet many biographies overlook her queer identity, a key aspect that she explored in her art. Her bisexuality is well documented, and she most famously had affairs with singer Chavela Vargas and artist Georgia O’Keeffe.9

One particular piece that stands out is “Self Portrait with Cropped Hair” (1940), a painting she made shortly after the divorce.10 The self-portrait shows her wearing traditional men’s clothing, which she frequently wore in

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Alicja Zelazko is Associate Editor, “Frida Kahlo,” Encyclopædia Britannica.

9 Sara Kettler, “Behind Frida Kahlo’s Real and Rumored Affairs with Men and Women,” Biography, July 14, 2020.

10 “Frida Kahlo. Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair. 1940,” MoMA.

her daily life, with a short haircut. She retains aspects of traditional femininity, such as earrings and high heels, blending iconography of both genders. This painting has often been interpreted as Frida expressing a newfound autonomy and exploration of her gender identity after her separation from Rivera.11

Another painting created just after her divorce was “Two Nudes in a Forest” (1939).12 The painting depicts two nude women with a monkey in the background. There have been multiple interpretations of this particular scene, with some seeing it as a representation of Kahlo’s ethnic and European identity, while others see it as Kahlo’s openness about her bisexuality. In Mexico, monkeys were symbols of sin and sexual promiscuity, alluding to possible discrimination faced by Frida in being true to her bisexual identity.13

Frida Kahlo’s life and work remind us that she was far more than just a painter with a striking appearance. She had a revolutionary spirit and authentically portrayed pain, existential crisis and queer openness. She paved the way for artists today who continue her tradition of being unapologetically themselves. Kahlo left behind a legacy that continues to inspire marginalized communities – turning pain into beauty, and suffering into empowerment.

11 Lucy Campbell, “LGBT+ History Month: Lucy Campbell on Frida Kahlo,” Scottish

12 “Two Nudes in a Forest, 1939 by

13 Lucy Campbell, “LGBT+ History Month: Lucy Campbell on Frida Kahlo,” Scottish

Feb. 7, 2022.

Written by Tessa Almond, Lifestyle Editor | Graphic by Zoee Boog |

Written by Lillian Hescheles |

Many people know how to braid hair – it’s a skill informally obtained through life experience. Once learned, braiding is viewed as an “everyday hairstyle” and a practical way to keep hair away from the face. Yet, as the braid continues to become synonymous with WesternAmerican culture, its deep roots in Black history are often overlooked and forgotten.

The popularized braided hairstyles seen today can be traced back to 3500 BC within the Himba people of Namibia.1 During this time, braiding wasn’t just a hairstyle, it was a method in which individuals could identify with their tribes while visualizing rank and identity. Centuries later, enslaved people utilized braids to convey hidden messages.2 For example, while navigating the Underground Railroad, cornrows were shaped into unique patterns, representing maps that enslaved people used to navigate escape routes and find safe houses.

Despite the deep cultural significance of braids to Black people, they’ve historically been forced to disconnect from them. For instance, during the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the first thing slave traders did was shave enslaved people’s hair off.3 Inside the home, enslaved people were forced to wear straight hair patterns similar to those of their slave master, a tactic used to assert control over their natural hair.

The act began a long history of dehumanization and cultural genocide, enabling the racially-motivated belief that Black people’s hair is “bad” and “unprofessional.”4 Today, many Black women put effort into hiding unique parts of their identity, including their natural hair, to uphold conventional beauty standards in society.5 Nevertheless, the cornrow braids created by African Americans are now worn by white people throughout American and Western culture.

Pieces of Black culture have a long history of appropriation among other groups and races, and braids are one of the most prevalent. The rise of social media has offered an increase in video tutorials, product recommendations and

1 Gina Conteh, “A Brief History of Black Hair Braiding and Why Our Hair Will Never Be A Pop Culture Trend,” BET, Aug. 23, 2019.

2 Odele, “A History Lesson Of Hair Braiding,” Odele, Jan. 16, 2024.

3 Gina Conteh, “A Brief History of Black Hair Braiding and Why Our Hair Will Never Be A Pop Culture Trend,” BET, Aug. 23, 2019.

4 Manka Nkimbeng, “The Person Beneath the Hair: Hair Discrimination, Health, and Well-Being,” Health Equity, Aug. 2, 2023.

5 Manka Nkimbeng, “The Person Beneath the Hair: Hair Discrimination, Health, and Well-Being,” Health Equity, Aug. 2, 2023.

personal experiences for braided hairstyles, which allows for more accessibility to these hairstyles and a larger demographic wearing them.6 This normalization spreads into platforms like Instagram, where online users can see Kim Kardashian wearing “boxer braids” (a popularized synonym for cornrows) and other celebrities ignoring the appropriation they unashamedly show off.

Along with braids, Western fashion has increased in popularity recently. But as the modern “dude-ranch” and “cowboy boot” aesthetic continues, it’s important to note the lack of inclusivity for Black people throughout history. Time after time again, country fashion has been primarily represented through white women, such as “Queen of the West” Dale Evans who popularized “mid-calf white boots” and Dolly Parton who thrived amongst rhinestone, nudie suits.7 Today, pop culture stars have followed in Evans’ and Parton’s footsteps, while leaving little room for Black people.8 For instance, in Ariana Grande’s “7 Rings,” she’s accused of using the ideas of black artist Princess Nokia, particularly in Grande’s discussion of hair extensions. 9 When Grande and other white individuals stake a claim on braids and other pinnacles of Black culture, it disregards the historical practices and trauma that come with braiding while also failing to credit Black people for trends that white people decide are worthy.10

Braiding is a beautiful hairstyle that’s fortunately available to many. However, it’s important to recognize the line between partaking in a hairstyle trend and appropriating someone’s culture. Braids aren’t a new trend defined by Western aesthetics. They aren’t a blank accessory existing amongst cowboy culture, festival fashion or popularized beauty trends. The truth of braiding must be remembered through the lens of African American history. Moving forward, let’s choose to braid hair with awareness, respect and an understanding of where our favorite hairstyles came from.

6 “The Impact of Social Media: How Instagram and Youtube Changed the Braiding Game,” Unclouded, Sep. 20, 2025.

7 Sarah Hepola, “How Cowgirl Couture Came to Be,” ELLE, Sep. 12, 2022.

8 Sarah Hepola, “How Cowgirl Couture Came to Be,” ELLE, Sep. 12, 2022.

9 Bass, Alyssa, “I want it, I got it: Cultural appropriation, white privilege, and power in Ariana Grande’s 7,” The Aquila Digital Community, April, 2020.