Psychometric analysis of selected tools for pressure ulcer risk assessment – literature review

Dariusz Bazaliński ¹,2,3, Paulina Szymańska 4 , Anna Surmacz¹,2,3, Kamila Pytlak¹,2, Beata Barańska¹,2,3,

1 Father B. Markiewicz Podkarpackie Oncology Centre, Specialist Hospital in Brzozow, Poland

2 Department of Wound Prevention and Treatment, Institute of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences and Psychology, Collegium Medicum, University of Rzeszow, Poland

3 Laboratory for Innovative Research in Nursing, University Research and Development Centre in Health Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences and Psychology, Collegium Medicum, University of Rzeszow, Poland

4 Radom School of Higher Education, Radom Specialist Hospital, Poland

Abstract

Introduction: Risk assessment tools have been utilised for several decades to systematically identify patients at risk of pressure ulcers.

Objective: To examine the psychometric properties of selected pressure ulcer risk assessment tools.

Material and methods: The present study employed a literature review method. A comprehensive review of the available literature from 2015 to 2025 was conducted, utilising the key words “tools for assessing pressure ulcer risk” and “pressure ulcer risk assessment scales”. The following databases were used: PubMed, EBSCO, and the national Termedia database. A comprehensive review of the existing literature was conducted, encompassing randomized studies, original studies, and meta-analyses. Following a thorough analysis of the available literature, the collected material was methodically categorized as follows: (a) universal pressure ulcer risk assessment tools, and (b) perioperative risk assessment tools. The present study focused on the analysis

Introduction

A pressure ulcer is defined as local damage to the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue resulting from pressure or pressure in combination with shear. Pressure-related wounds typically manifest on bony prominences; however, they may also be associated with medical devices or other objects [1]. Despite the considerable advances witnessed in the domains of medicine and health sciences, these complications persist in constituting a substantial challenge for healthcare

Address for correspondence: Anna Surmacz, Faculty of Health Sciences and Psychology, Collegium Medicum, University of Rzeszów, 16C Rejtana St., 35-310 Rzeszow, Poland, e-mail: annwojcik@ur.edu.pl

Nadesłano: 20.08.2025; Zaakceptowano: 29.09.2025

of 16 papers; the remaining cited manuscripts provide the necessary background for the discussion of the problem.

Results: The review did not confirm any domestic studies evaluating the psychometric properties of pressure ulcer risk assessment tools. The prevailing pressure ulcer risk scales are inadequate for consistent application in patients admitted to hospitals according to standardised criteria.

Conclusions: The persistent challenge of pressure ulcers continues to impose a significant burden on healthcare systems. The identification and implementation of preventive measures should be based on a comprehensive medical history, a physical examination, and the utilisation of standardised clinical tools. A review of the existing literature clearly indicates a deficit in current knowledge in the national literature. In the process of updating national guidelines, efforts should be made to prepare a psychometric evaluation of assessment tools and to prepare recommendations related to patient care in the perioperative period. Key words: pressure ulcer risk assessment, nurse, prevention.

systems. The aforementioned factors contribute to an exacerbation in patients’ overall health, thereby significantly affecting their dependence on the support of environment and health services in a manner that results in reduced autonomy, heightened feelings of insecurity, and a concomitant deterioration of mental well-being. The pressure ulcers are associated with considerable financial and individual costs and have a detrimental effect on the individual, affecting them physically, emotionally, and socially.

D. Bazaliński, P. Szymańska, A. Surmacz, et al.

Risk assessment and prophylactic measures are regarded as fundamental components of pressure ulcer prevention, as outlined in international and national practice guidelines [1, 2]. Risk assessment instruments (RAI) have been utilised for several decades to systematically identify patients at risk, as opposed to relying exclusively on clinical risk “assessment”. The identification of the environment in which preventive measures will be implemented (e.g. home environment or hospital ward) is a prerequisite for their effectiveness. This identification is followed by a clinical assessment of the patient’s condition. The assessment of the environment, individual risk, the availability of personnel, level of knowledge and skills, and the possibility of using pressure-relieving equipment and medical devices for preventive purposes form a uniform and coherent concept of pressure ulcer prevention. According to experts in the field, there are a number of highly specific situations that must be taken into consideration, including but not limited to operating room conditions, means of transport for patients, prostheses, and medical equipment [3, 4].

A reliable assessment of the risk of pressure ulcers should be based on a physical examination using questionnaires and clinical scales [5, 6].

Over the past 3 decades, the theoretical foundations of clinimetrics have evolved, resulting in the development and validation of a wide range of instruments designed to measure health status and quality of life. The gold standards for tool development emphasize the importance of ensuring content validity and conceptual frameworks. These standards include rigorous testing and evaluation processes to establish psychometric properties, such as content validity, discriminative validity, known group validity, criterion validity, and concurrent validity. Additionally, they encompass the assessment of inter-rater, intra-rater, and retest reliability. Risk assessment tools are combinations of individual risk factors used to assess the risk of tissue damage under pressure or shear forces. The majority of extant risk assessment instruments are scales that assign numerical values to various factors (e.g. mobility, nutrition, level of urinary and faecal continence), and the sum of these values forms a total score. The resulting score is used as an indicator of the risk of pressure ulcers. Risk assessment scales are utilised to stratify patients at risk of pressure ulcers into categories reflecting the degree of risk (e.g. low risk, medium risk, high risk). Risk assessment scales are evaluated for their ability to predict the development of pressure ulcers. However, preventive interventions are usually implemented immediately

after the risk is identified, and in some cases, the development of pressure ulcers is prevented [6].

The acceptability of the tool by users is equally important in clinical practice. Experts point to the availability of over 40 risk assessment scales, all of which address the issues of sensitivity (identification of actual risk) and specificity (identification of actual risk that is not risk). The complexity of the tools has been demonstrated to result in low reliability of results [7]. In the contemporary era, questionnaire-based assessment alone is inadequate and is susceptible to a high risk of error. Bearing in mind that it is the nurse’s responsibility to assess the patient’s health and perform a physical examination, each patient should be examined in accordance with the recommended algorithm, and the examination should be concluded with an assessment using selected (recommended) tools. Most available risk assessment tools encompass a range of factors, including activity, mobility, nutrition, moisture, sensory perception, friction and shear, and general health.

The objective of risk assessment is to identify individuals who are susceptible to developing pressure ulcers, with the aim of selecting and implementing recommended preventive measures. The utilisation of both risk assessment scales and clinical judgment is a pervasive component of routine practice, serving to identify individuals who are susceptible to developing pressure ulcers. The formulation of recommendations for action can be based on the assigned risk category. As a healthcare professional, nurses engage in a wide range of activities, including professional care, treatment, rehabilitation, and team management. They are obligated to make therapeutic and nursing decisions [8]. Moreover, the mounting demands on the nursing profession, stemming from the expansion of its competencies, underscores the necessity to delve more profoundly into a specialisation. The objective of individual professional development is to ensure the delivery of professional and effective care, in addition to meeting the needs of patients and their families [9]. These requirements have precipitated the implementation of evidence-based nursing practice (EBNP), which is defined as the utilisation of scientific evidence within the context of nursing practice. EBNP can be characterised as a clinical decision-making process that incorporates the most recent scientific research and therapeutic decisions, with these decisions being based on the patient’s condition [10].

A comprehensive review of the global literature reveals a marked increase in the involvement of nurses

in the prevention and treatment of wounds. The range of nursing competencies involved in the selection of methods and measures for treating slow-healing wounds is extensive and has achieved widespread consensus within the medical community. To provide effective and safe care for patients with wounds, it is essential that nursing staff possess a high level of qualification, extensive knowledge, and unquestionable social skills [11].

In a professional context, prevention is a meticulously formulated, acquired, guideline- and recommendation-based, widely comprehensible, holistic professional activity. The specific nature of the profession offers significant opportunities for the prevention and treatment of local wounds in individuals with self-care deficits who are at risk of developing pressure ulcers. The implementation of preventive measures in a timely manner, in conjunction with the utilisation of efficacious interventions, facilitates the deferral of the onset of pressure ulcers and the initiation of treatment during its early stages. The identification of individuals susceptible to developing pressure ulcers constitutes the initial phase in the prevention of such lesions [12]. It is imperative that procedures implemented as part of a prevention initiative consider the quality of nursing care in addition to the recommendations and scientific research results. Patients at risk of developing pressure ulcers should undergo continuous assessment by an interdisciplinary team. This team is responsible for defining the scope of activities for each team member, along with specific roles and tasks. The implementation of measures ought to be informed by the recommendations put forth by scientific societies and global guidelines [13].

A comprehensive literature review was conducted on selected tools for assessing the risk of pressure ulcers, taking into account the conditions of the healthcare system in the area of prevention.

The objective of this study is to examine the psychometric properties of selected pressure ulcer risk assessment tools.

Material and methods

The present study employed a literature review method. A comprehensive review of the available literature from 2015 to 2025 was conducted, using keywords such as “tools for assessing pressure ulcer risk” and “pressure ulcer risk assessment scales”. The following databases were utilised: PubMed, EBSCO, and the national Termedia database. Randomised studies, original studies, and meta-analyses were included. Following a thorough analysis of the existing

literature, the collected material was methodically categorised as follows: (a) universal pressure ulcer risk assessment tools, and (b) risk assessment tools in the perioperative period. The present study focused on the analysis of 16 papers; the remaining cited manuscripts provide the necessary background for the discussion of the problem. The process of searching for duplicates is illustrated in Figure 1.

Identification of records through database searching (PubMed, n = 519), (EBSCO, n = 42)

Identification of records through database searching (Termedia) (n = 76)

Excluded records (n = 585)

Papers rejected (n = 449);

• case studies,

• cost effectiveness of a system

• PI/U in newborns and children,

• historical studies,

• nutritional prevention

• mucous membranes

Papers on pressure injury/ulcer (PI/U) (n = 136)

Papers rejected (n = 120);

• nursing students,

• preventive dressing

• preventive repositioning

• PI/U treatment

Articles eligible for review that discuss tools for assessing the risk of pressure ulcers/injury PI/U (n = 16) INCLUDED

1. Data review process

Universal tools for assessing the risk of pressure ulcers

Pressure ulcers represent a grave health, social, and economic problem. It is widely accepted that most pressure injuries can be prevented through the implementation of fundamental preventive measures. The available assessment tools are based on an analysis of the most common risk factors [2, 14]. Despite the existence of a broad array of pressure ulcer risk assessment tools globally, the most prevalent and renowned instruments in Poland are the Norton, Braden, Waterlow, CBO, and Douglas scales. A review of the available Polish- and English-language literature failed to identify any studies that evaluated psychometric indicators for Polish conditions. The Douglas

Figure

D. Bazaliński, P. Szymańska, A. Surmacz, et al.

and Dutch Consensus Prevention of Bedsores (CBO) scales were not analysed due to the absence of studies evaluating these scales during the specified review period.

The Norton scale is among the initial instruments developed for the evaluation of the risk of pressure ulcers. Published in 1962, it was developed as an assessment instrument for geriatric patients, and it encompasses an evaluation of 5 variables: physical condition, level of consciousness, activity, and the ability to change position independently and control the sphincters of the anus and urethra [2].

The Waterlow scale was developed in 1985 by Judy Waterlow with a specific focus on elderly patients, particularly those undergoing surgical procedures who were over 60 years of age. The tool’s primary function is to assess the physiological condition and associated diseases in elderly patients, with a high degree of accuracy in predicting the risk of pressure ulcers [2].

The Braden Scale is a widely utilised instrument, considered the most prevalent tool globally. The development of this technology was initiated in 1987 in the United States by Barbara Braden and Nancy Bergstrom, who identified a pressing need for an effective tool to predict and prevent pressure ulcers. This instrument has the widest range of applications [15]. The utilisation of this instrument is appropriate for the purpose of evaluating the presence of pressure ulcers in elderly patients. The assessment encompasses a range of variables, including sensation, activity, mobility, nutritional status, friction, and shear force. The necessity to develop new research instruments remains salient because it is associated with the continuous advancement of health sciences and the pursuit of solutions for more precise identification of patients at risk of pressure ulcers [16]. Nonetheless, as indicated by the findings of certain studies, the system’s capacity to prognosticate the likelihood of skin injury across diverse populations and within varied clinical contexts appears to be constrained [17]. In a meta-analysis conducted by Park et al., the 3 most commonly used scales (Norton, Braden, Waterlow) were evaluated. The findings suggest a comparable scope with moderate precision for the scales examined, while heterogeneity exhibited over 80% variability across studies. The results obtained from the meta-analysis indicate that commonly used screening tools for assessing the risk of pressure ulcers have limitations in terms

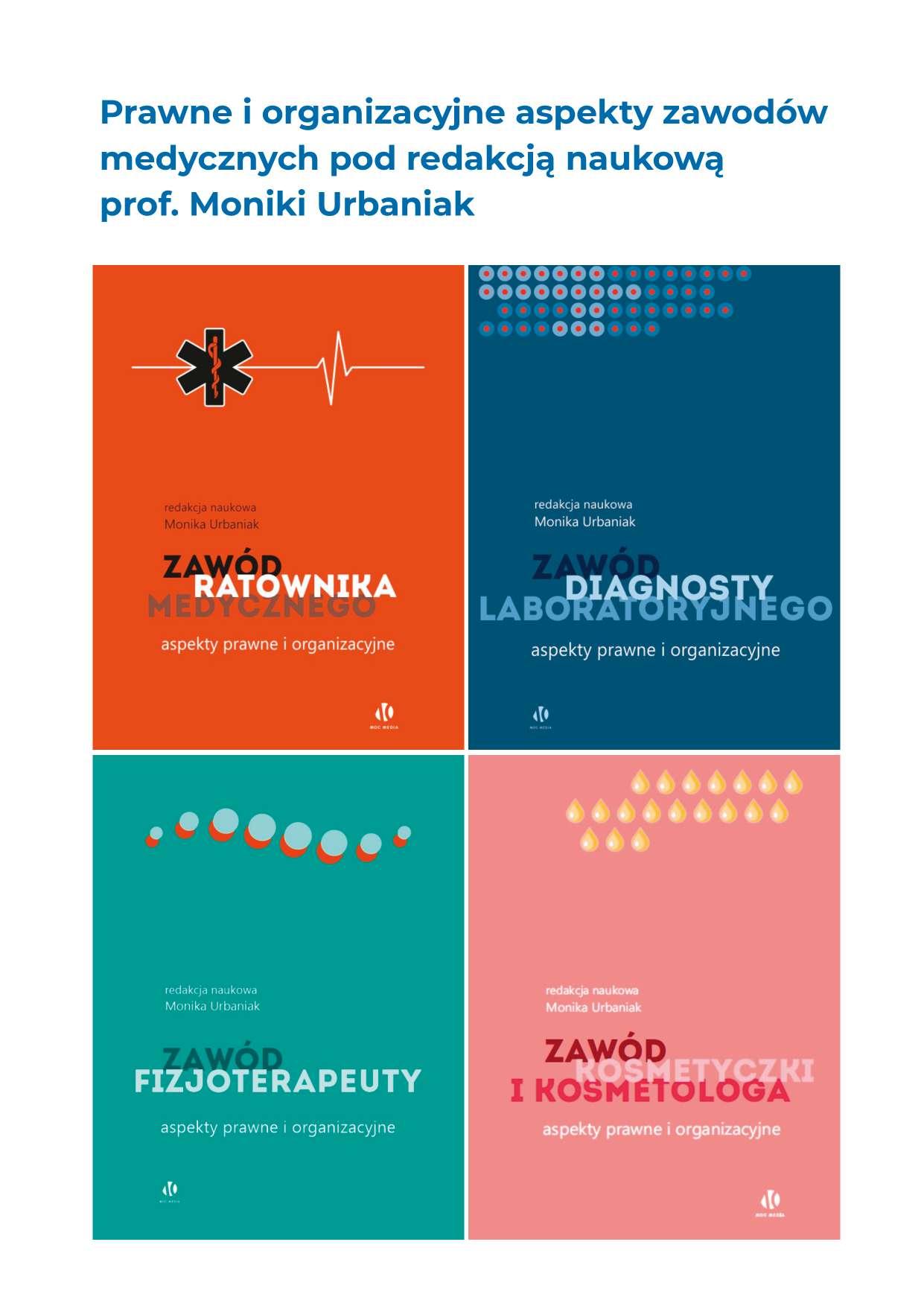

of validity and accuracy in relation to older people due to heterogeneity in the studies [15, 18, 19]. The psychometric data and characteristics of the tools are presented in Table 1. A review of the existing literature on risk assessment tools (RAI) was conducted by Coleman et al., which included a systematic review of the content, development, and testing of 14 RAI tools included in the 2014 NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) review. The study identified limitations of existing RAI tools. The authors noted that numerous tools were developed decades ago, during a period characterised by a lack of evidence regarding risk factors for pressure ulcers and methodological guidelines for the development and evaluation of tools [3, 20]. A tool must demonstrate both sensitivity and specificity in its identification of at-risk and non-at-risk individuals, respectively. Assessing reliability and validity poses a significant challenge in clinical practice, as risk assessment scales are utilised to identify individuals who would develop pressure ulcers if no intervention were taken. Once the risk has been identified, various pressure ulcer prevention strategies are often implemented, which appear to alter the scale’s predictive ability. The lack of clear knowledge about the sensitivity and specificity of risk assessment tools has far-reaching implications for practice, because clinical decisions—such as whether or not to use pressure ulcer prevention strategies—are often made based on risk assessment results, although it has also been argued that nurses often rely solely on clinical judgment when deciding which preventive measures to use. To address the limitations of existing risk assessment tools and instruments, the Primary or Secondary Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Tool (PU) (PURPOSE-T) was developed [3, 7, 20]. This tool was developed using recommended research methods. The primary objective of this system is to identify adults at risk of developing pressure ulcers and to provide nurses with the necessary tools to make informed decisions aimed at reducing the incidence of these lesions (i.e. primary prevention). Additionally, the system is designed to identify individuals with existing or previous pressure ulcers, who require secondary prevention and treatment. The authors employed a color-coded system to denote the most significant risk factors and devised a three-step assessment procedure: Step 1: Screening – to quickly exclude those who are clearly not at risk. This includes an assessment of mobility and skin condition (including the use of

Table 1. Selected general tools for assessing pressure ulcers in research analysis

Scale Design

Braden

Norton

6 elements (perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, friction)

Clinical indications

Sensitivity according to studies Scoring (risk cutoff) Citation

Waterlow

5 elements (physical condition, mental condition, mobility, activity, incontinence)

Hospitals, intensive care units, long-term care

Simple assessment, alternative to other tools

Moderate predictive accuracy, more suitable for middle-aged patients under 60 years of age, hospitalised patients, and the Caucasian population; a cut-off point of 18 may be used to assess the risk of pressure injuries in clinical practice.

AUC for average age <60 years (0.87, 95% CI: 0.84–0.90),

Sensitivity between 62% and 83%, depending on the population and the cut-off point used.

Specificity between 45% and 67%

AUC ROC for Norton in studies 0.70–0.75

15–18 low risk, ≤ 9 points = very high risk

< 15 points = low or no risk, ≤ 11 very high risk

Huang et al. (2021) [16]

Wai et al. (2020) [15]

Šateková et al. [19] (2017)

Park et al. (2016) [18]

11+ elements (body composition, age, BMI, gender, disease, mobility, nutrition and dietary preferences, mobility and activity, specific factors, disability and incontinence)

Hospitals, palliative care, long-term

Sensitivity depends on the threshold adopted: at ≥ 10 points – up to 87.5% (range 82–90%), at ≥ 15 points – approx. 71.4%, at ≥ 20 points – up to 85.7%,

Specificity; at ≥ 10 points – approx. 28% (range 22–85%), at ≥ 15 points – approx. 94%, at ≥ 20 points – approx. 41% and variable predictive accuracy 0.54–0.90, with a median of approx. 0.60–0.61 in large population analyses. To achieve full effectiveness, it should be used in conjunction with clinical nursing assessment and ongoing staff training

A maximum of 64 points can be obtained. A score of 10–14 points indicates risk, 15–19 indicates high risk, and above 20 indicates very high risk

Charalambous et al. (2017) [21]

PURPOSE-T

3-stage: screening + assessment of 9 factors + colour-based decision Hospitals, home care, primary/secondary prevention

AUC = 0.83–0.87

Colour: green (none), orange (risk), pink (pressure ulcer)

Coleman et al. (2018) [20]

Sensitivity: the capacity of the instrument (scale) to discern subjects who are susceptible to developing pressure ulcers. Specificity: the capacity of the tool to discern individuals who are not at risk of developing pressure ulcers. Cut-off score: threshold score indicating the need to implement preventive measures, AUC (ROC): predictive accuracy of the scale (≥ 0.80 – very good), ICC (inter-rater): consistency of assessments by different users, CI (confidence interval), 95%

medical devices), and nurses are encouraged to use their clinical judgment to identify any other risk factors that are relevant to the individual patient.

Step 2: Full assessment – includes the following evidence-based elements: independent movement, detailed skin assessment, previous history of pressure ulcers, medical devices, perfusion, sensory perception, moisture, diabetes.

Step 3: Assessment decision based on Step 2 and supported by colour coding:

• green: no pressure ulcers – no current risk

• orange: no pressure ulcers, but risk present, requiring primary prevention

• red: pressure ulcer category 1 or higher, or scars from previous pressure ulcers requiring prevention/secondary treatment [20].

D. Bazaliński, P. Szymańska, A. Surmacz, et al.

Selected tools for assessing the risk of pressure ulcers in the perioperative period

Clinical prevention of pressure injuries is based on professional and standard assessment of patients and ensuring adequate protection [22]. A comprehensive understanding of preoperative risk factors serves as the foundation for the implementation of preventive measures. Consequently, the nursing staff can implement preventive interventions prior to the occurrence of tissue injury. The primary preventive measure for pressure ulcers is the utilisation of recommended risk assessment tools for the purpose of conducting an early, systematic, accurate, dynamic, and effective assessment. A variety of preventive interventions are available, including the prophylactic use of multi-layer dressings, the utilisation of alternative pressure mattresses, and polymeric bladder-resistant-elastic (gel) on the operating table during surgery. Additionally, patient and caregiver education on nutrition and skin care, frequent position changes, and the use of positioning wedges are recommended [23]. Scales such as Norton, Waterlow, and Braden were not designed for risk assessment in surgical patients and therefore should not be recommended for use in this context. These scales do not take into account risk factors associated with surgery and have low predictive value and low sensitivity for perioperative pressure injuries. Wei et al. conducted a meta-analysis that indicated moderate predictive accuracy of Braden’s scale. The analysis demonstrated that the scale exhibited good sensitivity and low specificity in critically ill adult patients. The further development and modification of this tool, or the creation of a new tool with higher predictive power, is justified for use in critically ill patients [17]. The existing body of literature on hospital-acquired pressure ulcers (HAPIs) is characterised by a lack of reliable reports [24]. A global analysis of the literature and the 2019 recommendations indicates that significant emphasis should be placed on raising awareness of the risk of pressure ulcers in hospitalised patients [1]. In a systematic analysis conducted by Chen et al., the incidence of pressure injuries during surgery was reported to be 15%. Intraoperative pressure injuries (IAPI) are a prevalent cause of skin damage in the perioperative period. The necessity of anaesthesia and surgical intervention renders patients susceptible to acute, localised tissue injury associated with pressure. This injury manifests within 48 to 72 hours post-surgery and is associated with the specific surgical site [26]. Surgical interventions that extend

beyond 2 hours are recognised as a risk factor for the development of pressure ulcers. Aloveni et al. identified 8 significant risk factors associated with HAPI among the surgical population. These risk factors include age ≥ 75 years, female gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade ≥ 3, low BMI, low preoperative Braden score ≤ 14, and comorbidities such as anaemia, respiratory diseases, and hypertension [23]. The development of a pressure ulcer can have numerous adverse consequences, including pain, the necessity for additional treatment, prolonged hospital stays, deformities, and scarring of the body. These consequences can lead to increased morbidity, elevated treatment costs, and an increase in the workload for nurses by more than 50%, resulting in a 3–4-fold increase in the cost per patient [1, 24].

Latimer et al. indicated a high risk of skin damage from pressure ulcers within the initial 36 hours of hospital admission. In a sample of 1047 participants, pressure ulcers were confirmed in 10.8% of the study population. Researchers’ observations indicate that older people with multiple comorbidities and those living in nursing homes are more likely to be admitted to hospital with existing pressure ulcers or to develop them shortly after admission [27, 28]. In the course of the analysis of selected studies, several tools were highlighted.

The Munro pressure ulcer risk assessment scale is a comprehensive tool that is utilised to evaluate the risk of developing pressure ulcers in the perioperative setting. This scale encompasses 3 distinct stages of assessment: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative. The preoperative stage involves a comprehensive evaluation of various factors, including mobility, nutritional status, BMI, recent weight loss, age, and comorbidities. The intraoperative stage focuses on the patient’s American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status, the type of anaesthesia administered, temperature control, the presence of hypotension, humidity levels, the type of support and position used during surgery, and any movements. The postoperative stage is concerned with the duration of surgery and the amount of blood loss. The assessment yields a risk score for each stage, with the total score indicating the overall risk level [17]. The Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses (AORN) proposed and recommended this approach in 2016. The tool is employed to evaluate the primary perioperative risk factors and is extensively utilised for IAPI risk assessment. The EMINA scale was developed as an adaptation of the Norton scale and includes 5 key risk factors: mental status, mobility,

Table 2. Selected risk tools in perioperative care

Citation

Scoring (risk cutoff)

Sensitivity according to studies

Roca-Biosca et al. (2015) [28]

Score range: 0 to 15 points > 10 points = risk

Sensitivity: 94.3% (95% CI: 87.17–100%) Low specificity: 33.33% (95% CI: 25.01–41.66%) 4.3% (AUC 0.90)

Clinical indications

Lospitao-Gómez et al. (2017) [37] De Souza et al. (2023) [38]

≥ 10 points = risk

Sensitivity 80.43% (95% CI: 79.15–81.72%) Specificity 64.41% (95% CI: 63.68–65.14%) Has comparable predictive accuracy to the Braden scale (AUC 0.807) and may be more specific for ICU patients

Recommended for use as an initial screening tool, followed by more specific clinical assessment or another scale

Design

Intensive care units

Developed as an adaptation of the Norton scale and includes 5 key risk factors: mental status, mobility, urinary/faecal incontinence, nutrition, and activity level

Scale

EMINA

Park, et al . (2016) [18]

< 24 points = high risk

Adibelli et al. (2019) [32]

Mosher et al. (2025) [29]

≥ 2 points high risk

Sensitivity 87%, specificity 84% AUC 0.826–0.902 Valuable tool for assessing the risk of pressure ulcers in intensive care units, with advantages over classic scales such as Braden or Norton

Intensive care units, neurology, postoperative

Comprises 6 elements (mobility, perfusion, skin, consciousness, equipment, age)

EVARUCI

Includes 10 elements (including consciousness, haemodynamics, oxygen therapy, age, BMI)

Cubbin-Jackson

Points are calculated at each stage

Due to the small sample size, no statistical significance was achieved; the authors emphasise improved team communication, staff awareness, and potential for complication prevention

Hospital, operating room, surgical wards

Comprises 4 components (age, serum albumin level, estimated duration of surgery, and American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] score)

The Scott Triggers Tool

Lei et al. (2022) [17]

The points are added up to assess the risk in three levels: < 13 –low 14–24 –moderate ≥ 25 –high risk The assessment is performed dynamically at each of these stages (before, during, and after surgery)

specificity

Intraoperative sensitivity

AUC 0.874

Postoperative sensitivity 67.7%, specificity

AUC 0.774 (95% CI: 0.929–0.971)

Hospital, operating room, treatment wards

Cross-cultural adaptations: in China (2018), Turkey (2021), Brazil (2022)

Three-stage; assesses the risk of pressure ulcers in the perioperative period; preoperative (mobility, nutritional status, BMI, recent weight loss, age, comorbidities), intraoperative (ASA status, type of anaesthesia, temperature, hypotension, humidity, type of support/ position, movements) and postoperative (duration of surgery, blood loss). Each stage of the assessment gives a low, mediumor high-risk result, with a total result at the end.

Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale for Perioperative Patients MUNRO

D. Bazaliński, P. Szymańska, A. Surmacz, et al.

Citation

Scoring (risk cutoff)

Sensitivity according to studies

Sengul et al . 2023 [30]

Salvini et al. (2024) [31]

Sensitivity (85%), specificity (75%) predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.85) ≤ 15 points –low risk 16–28 points –moderate risk ≥ 29 points –high risk

Clinical indications

Konatake et al. (2025) [39]

urinary/faecal incontinence, nutrition, and activity level [29]. The manuscripts selected during the analysis, which included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and original studies, were aimed at identifying tools for assessing the risk of pressure ulcers. A selection of these works is presented in Table 2.

The Scott Triggers Tool is a widely utilised instrument for the assessment of pressure ulcers in surgical patients. The model under consideration comprises 4 components: age, serum albumin level, estimated duration of surgery, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score. This instrument evaluates various factors, including patient age, nutritional status, duration of surgery, and the nature of the procedure [30].

Table 2. Selected risk tools in perioperative care (cont.)

Design

Hospital, operating room, treatment wards

Consisted of a total of 7 elements, each containing 5 sub-elements. It is assessed on a scale from 1 to 5 in the Likert type. The total score ranges from 7 to 35. The risk of pressure ulcers increases in patients as the score increases

Scale

Surgical Positioning Risk Scale Surgical Positioning Risk Scale ELPO

No data on the sensitivity of the tool in the analysed literature, positive correlation between ELPO (Brazilian Perioperative Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale) and Munro

Hospital, operating room, surgical wards

(Surgery-Related Pressure Injury Risk Assessment Scale) SURPIRAS takes into account risk factors such as age, body mass index (BMI), ASA score, type of anaesthesia, duration of surgery, amount of bleeding, moisture in pressure areas, position changes, use of pressure relief/ accommodations

The ELPO pressure ulcer risk assessment scale for surgical patients provides more detailed descriptions of joint positioning during surgery as part of the assessment of limb positioning. It is employed to evaluate the likelihood of pressure ulcers that patients may develop as a result of surgical positioning during surgery [31, 32]. In a study by Sengul et al., a substantial accuracy rate of 0.944 was confirmed in a group of 186 patients who underwent surgical treatment. The sensitivity of the test was 60%, its specificity was 66%, and its accuracy was 66%. A negative, weak, statistically significant correlation was identified between the total scores on the risk assessment scale for the prevention of surgical positioning injuries and the Braden scale. The tool is recommended for the assessment of patients after surgery in Turkey [31].

The Cubbin Jackson scale was developed in 1991 for patients in intensive care units. The tool incorporates a comprehensive evaluation of general risk factors and those specific to ICU patients. It encompasses a range of parameters, including age, body weight, medical history, general skin condition, mobility, nutritional status, urinary incontinence, hygiene, mental status, haemodynamics, respiration, and oxygen requirements [18, 33]. However, the scientific evidence supporting the use of the Jackson/Cubbins scale to assess the risk of PI-induced complications in ICU patients remains limited and conflicting. As demonstrated by Higgins et al. [34] and Delawder et al. [35], the Jackson/Cubbins scale exhibits moderate predictive value. A meta-analysis conducted by Zhang et al. [36], demonstrated that previous studies were characterized by low quality of scientific evidence and significant heterogeneity, which requires verification in future studies.

The EVARUCI scale is a comprehensive assessment tool that evaluates 6 key domains: mobility, perfusion, skin, consciousness, devices, and age. It is a reliable instrument for evaluating the risk of pressure ulcers in the ICU. The model’s performance metrics, such as sensitivity and specificity, exhibit variations depending on the geographical location of the study (Spain vs. Brazil). However, its overall predictive accuracy (AUC ROC ~0.8) aligns closely with the Braden scale. Furthermore, its efficacy in cross-cultural adaptation has been substantiated in numerous studies [37, 38]. A study by de Souza et al. [38] confirmed the predictive ability of the EVARUCI scale, which was similar to

that of the Braden scale. However, the accuracy of both scales was found to be suboptimal in terms of accurately predicting patients at risk of PI [38].

The SURPIRAS (Surgery-Related Pressure Injury Risk Assessment Scale) is a novel instrument designed to evaluate the risk of pressure ulcers associated with surgical interventions. This scale was developed and validated in the Turkish population [39].

Discussion

The primary objective of care should be the prevention of pressure ulcers. Members of the treatment team should regularly assess the risk of pressure ulcers. The basis for prevention, therefore, must be strong scientific evidence. The efficacy of the implementation and application of clinical guidelines can be determined through well-designed studies and initiatives to enhance the quality of current practices. Clinical decisions should be based on current scientific evidence and present a range of options to aid decision-making between healthcare professionals, patients or their caregivers, and the interdisciplinary team in the prevention of pressure ulcers [2, 40].

The constantly growing number of patients with difficult-to-heal wounds determines the development of nurses’ competences and qualifications. The provision of professional care and the implementation of therapeutic procedures require an in-depth knowledge base, a high level of competence, and practical skills. It is imperative that nurses allocate particular attention to elderly patients, particularly during the perioperative period and during intensive care, and undergo specialised training related to clinical assessment and the utilisation of standardised tools [41]. In addition, other staff members responsible for fundamental care should be included in the care process, in accordance with established standards and procedures. A review of the literature did not reveal any national studies on the validation of pressure ulcer risk assessment tools or studies indicating tools for use in the perioperative period. According to Park et al. [18], a meta-analysis of 17 studies (5185 patients) revealed that the currently used pressure ulcer risk scales are not suitable for uniform practice in patients hospitalised according to standardised criteria. Consequently, to ensure the delivery of more effective nursing care for pressure ulcers, an in-depth analysis reflecting patient characteristics is necessary, as well as the development of a new or modified pressure ulcer risk scale to complement the strengths and weaknesses of existing tools [18]. Given the observed variability in the incidence of postoperative pressure ulcers,

which has been documented in various studies and ranges from 1.3% to 54.8%, depending on the surgical procedure and the demographic characteristics of the patient population, it is imperative to undertake comprehensive efforts to translate these instruments and prepare them for psychometric evaluation and subsequent implementation in clinical practice [25]. Consequently, the procedures implemented as part of prevention should be adapted to specific and well-defined risk factors. It is evident that the aforementioned subjects will manifest distinct behaviours in 3 distinct settings: the operating room, the intensive care unit, and the geriatric ward. Patients at risk of developing pressure ulcers should undergo continuous assessment by an interdisciplinary team, with a clearly delineated scope of responsibilities for each team member [41]. Recent research has led to significant advancements in our understanding of the risk factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers. A significant number of risk assessment instruments fail to incorporate these advancements in knowledge. A meta-analysis by Moore and Patton [42] was conducted to determine whether the use of risk assessment tools reduces the incidence of pressure ulcers. The authors identified only 2 studies that met the criteria [43, 44]. Despite the low certainty of the available scientific evidence related to the use of standardised pressure ulcer risk assessment tools, this area should be strengthened by developing tools based on methodological guidelines. Other variables that indicate a link between the development of pressure ulcers and staff shortages, low staffing levels, and low utilisation of qualifications and competencies in the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers should also be taken into account [45, 46]. A meta-analysis was conducted by Lei et al. to evaluate the efficacy of the Munro pressure ulcer risk assessment scale in rapidly and accurately predicting the risk of pressure injuries in patients undergoing general anaesthesia. The results of this analysis suggest that further research is necessary to validate the tool for national conditions. A comparison of its reliability, validity, advantages, disadvantages, and predictive ability with the more commonly used Braden scale is indicated, as this would indicate the possibility of continuous use throughout the perioperative period and widespread use in operating rooms [17]. Another noteworthy instrument is PURPOSE-T, which was developed employing recommended research methodologies. It identifies adults at risk of developing pressure ulcers and supports nurses in making decisions to reduce them (primary prevention), as well

D. Bazaliński, P. Szymańska, A. Surmacz, et al.

as identifying individuals with existing and previous pressure ulcers who require secondary prevention and treatment. The aforementioned instruments are expected to facilitate a more comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s condition, particularly in light of the fact that the most elementary evaluation scale, the Norton scale, remains in use within the country, despite the emergence of novel global findings.

Conclusions

The persistent challenge of pressure ulcers imposes a substantial strain on healthcare systems. The identification and implementation of preventive measures should be based on a comprehensive medical history, a physical examination, and the utilisation of standardised clinical tools. A review of the available literature clearly indicates a deficit in current knowledge in the national literature. In the course of revising national guidelines, efforts should be made to prepare a psychometric evaluation of assessment tools and to prepare recommendations related to patient care in the perioperative period.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Anna Nowak for translating the text.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of unterest. This research received no external funding. Approval of the Bioethics Committee was not required.

1. References

2. Kottner J, Cuddigan J, Carville K, et al. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: The protocol for the second update of the international Clinical Practice Guideline 2019. J Tissue Viability 2019; 28: 51–58. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtv.2019.01.001.

3. Szewczyk M, Kózka M, Cierzniakowska K, et al. Prophylaxis of pressure ulcers – recommendations of the Polish Wound Management Association. Part I. Leczenie Ran 2020; 17: 113–146. DOI: 10.5114/lr.2020.101506.

4. Coleman S, Nixon J, Keen J, et al. Using cognitive pre-testing methods in the development of a new evidenced-based pressure ulcer risk assessment instrument. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016; 16: 158. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-016-0257-5.

5. Hotaling P, Black J. Ten top tips: honing your pressure injury risk assessment. Wounds International 2021; 12: 8–11.

6. Delmore BA, Ayello EA. Braden Scales for Pressure Injury Risk Assessment. Adv Skin Wound Care 2023; 36: 332–335. DOI: 10.1097/01. ASW.0000931808.23779.44.

7. Szewczyk M, Cwajda-Białasik J, Mościcka P, et al. Treatment of pressure ulcers – recommendations of the Polish Wound Management Association. Part II. Leczenie Ran 2020; 151–184. DOI: 10.5114/ lr.2020.103116.

8. Coleman S, Gorecki C, Nelson EA, et al. Patient risk factors for pressure ulcer development: systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50: 974–1003. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.019.

9. Ten Ham-Baloyi W. Nurses’ roles in changing practice through

implementing best practices: A systematic review. Health SA 2022; 27: 1776. DOI: 10.4102/hsag.v27i0.1776.

10. Wąsowska I., Kózka M. Nurses’ opinions on the use of scientific evidence in professional practice. Nursing Problems 2015; 23: 392–397.

11. Melnyk BM, Tan A, Hsieh AP, Gallagher-Ford L. Evidence-Based Practice Culture and Mentorship Predict EBP Implementation, Nurse Job Satisfaction, and Intent to Stay: Support for the ARCC© Model. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2021; 18: 272–281. DOI: 10.1111/wvn.12524

12. Fukada M. Nursing Competency: Definition, Structure and Development. Yonago Acta Med. 2018; 61: 1–7. DOI: 10.33160/yam.2018.03.001

13. Szumska A. Legal conditions for wound treatment by nurses in Poland. Pielęg Chir Angiol 2020; 2: 47–52.

14. Głowacz J, Szwamel K. Nursing staff’s knowledge of chronic wounds and methods of their treatment. Surgical and Vascular Nursing. 2022; 16: 25–34.

15. Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Treatment of pressure ulcers: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015; 162: 370–379. DOI: 10.7326/M14-1568.

16. Huang C, Ma Y, Wang C, et al. Predictive validity of the braden scale for pressure injury risk assessment in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Open 2021; 8: 2194–2207. DOI: 10.1002/ nop2.792.

17. Wei M, Wu L, Chen Y, Fu Q, Chen W, Yang D. Predictive Validity of the Braden Scale for Pressure Ulcer Risk in Critical Care: A Meta-Analysis. Nurs Crit Care 2020; 25: 165–170. DOI: 10.1111/nicc.12500.

18. Lei L, Zhou T, Xu X, Wang L. Munro Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale in Adult Patients Undergoing General Anesthesia in the Operating Room. J Healthc Eng 2022; 2022: 4157803. DOI: 10.1155/2022/4157803.

19. Park SH, Lee YS, Kwon YM. Predictive Validity of Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Tools for Elderly: A Meta-Analysis. West J Nurs Res 2016; 38: 459–483. DOI: 10.1177/0193945915602259.

20 Šateková L, Žiaková K, Zeleníková R. Predictive validity of the Braden Scale, Norton Scale, and Waterlow Scale in the Czech Republic. Int J Nurs Pract 2017; 23: 10.1111/ijn.12499. DOI: 10.1111/ ijn.12499.

21. Coleman S, Smith IL, McGinnis E, et al. Clinical evaluation of a new pressure ulcer risk assessment instrument, the Pressure Ulcer Risk Primary or Secondary Evaluation Tool (PURPOSE T). J Adv Nurs 2018; 74: 407–424. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13444.

22. Charalambous C, Koulori A, Vasilopoulos A, Roupa Z. Evaluation of the Validity and Reliability of the Waterlow Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale. Med Arch 2018; 72: 141–144. DOI: 10.5455/ medarh.2018.72.141-144

23. McEvoy N, Avsar P, Patton D, Curley G, Kearney CJ, Moore Z. The economic impact of pressure ulcers among patients in intensive care units. A systematic review. J Tissue Viability. 2021; 30: 168–177. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtv.2020.12.004.

24. Aloweni F, Ang SY, Fook-Chong S, et al. A prediction tool for hospital-acquired pressure ulcers among surgical patients: Surgical pressure ulcer risk score. Int Wound J 2019; 16: 164–175. DOI: 10.1111/ iwj.13007.

25. Popow A, Szewczyk M, Cierzniakowska K, Kozłowska E, Mościcka P, Cwajda-Białasik J. Risk factors for bedsore development among hospitalised patients. Surgical and Vascular Nursing 2018; 12: 152–158.

26. Chen HL, Chen XY, Wu J. The incidence of pressure ulcers in surgical patients of the last 5 years: a systematic review. Wounds 2012; 24: 234–241.

27. Shang Y, Wang F, Cai Y, et al. The accuracy of the risk assessment scale for pressure ulcers in adult surgical patients: a network meta-analysis. BMC Surg 2025; 25: 104.21. DOI: 10.1186/s12893-024-02739-y.

28. Latimer S, Chaboyer W, Thalib L, McInnes E, Bucknall T, Gillespie BM. Pressure injury prevalence and predictors among older adults in the first 36 hours of hospitalisation. J Clin Nurs 2019; 28: 4119–4127. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.14967.

29. Konateke S. A Major Risk in Operating Rooms: Pressure Injury.

Journal of Anatolia Nursing and Health Sciences 2021; 24, 3: 365–372.

30. Roca-Biosca A, Garcia-Fernandez FP, Chacon-Garcés S, et al. Validación de las escalas de valoración de riesgo de úlceras por presión EMINA y EVARUCI en pacientes críticos [Validation of EMINA and EVARUCI scales for assessing the risk of developing pressure ulcers in critical patients]. Enferm Intensiva 2015; 26: 15–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.enfi.2014.10.003.

31. Mosher R. Enhancing Perioperative Care: Implementing the Scott Triggers Tool to Prevent Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries in Vascular Surgery Patients. AORN J 2025; 121: 198–207. DOI: 10.1002/ aorn.14303.

32. Sengul T, Gul A, Yilmaz D, Gokduman T. Translation and validation of the ELPO for Turkish population: Risk assessment scale for the development of pressure injuries due to surgical positioning. J Tissue Viability 2022; 31: 358–364. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtv.2022.01.011.

33. Salvini A, Silva E, Passos C, et al. Validation of ELPO-PT: A Risk Assessment Scale for Surgical Positioning Injuries in the Portuguese Context. Nurs Rep 2024; 14: 3242–3263. DOI: 10.3390/ nursrep14040236.

34. Adibelli S, Korkmaz F. Pressure injury risk assessment in intensive care units: Comparison of the reliability and predictive validity of the Braden and Jackson/Cubbin scales. J Clin Nurs 2019; 28: 4595–4605. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.15054.

35. Higgins J, Casey S, Taylor E, Wilson R, Halcomb P. Comparing the Braden and Jackson/Cubbin Pressure Injury Risk Scales in Trauma-Surgery ICU Patients. Crit Care Nurse 2020; 40: 52–61. DOI: 10.4037/ ccn2020874

36. Delawder JM, Leontie SL, Maduro RS, Morgan MK, Zimbro KS. Predictive Validity of the Cubbin-Jackson and Braden Skin Risk Tools in Critical Care Patients: A Multisite Project. Am J Crit Care 2021; 30: 140–144. DOI: 10.4037/ajcc2021669.

37. Zhang Y, Zhuang Y, Shen J, et al. Value of pressure injury assessment scales for patients in the intensive care unit: Systematic review and diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2021; 64: 103009. DOI: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.103009

38. Lospitao-Gómez S, Sebastián-Viana T, González-Ruíz JM,

Álvarez-Rodríguez J. Validity of the current risk assessment scale for pressure ulcers in intensive care (EVARUCI) and the Norton-MI scale in critically ill patients. Appl Nurs Res 2017; 38: 76–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.09.004.

39. de Souza MFC, Zanei SSV, Whitaker IY. Predictive validity of the EVARUCI scale to evaluate risk for pressure injury in critical care patients. J Wound Care 2023; 32 (Supl. 8): clxi-clxv. DOI: 10.12968/ jowc.2023.32.Sup8.clxi

40. Konateke S, Güner Şİ. Development of A Surgery-Related Pressure Injury Risk Assessment Scale (SURPIRAS): A Methodological Study. J Clin Nurs 2025; 34: 4841–4853. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.17765.

41. Tura İ, Arslan S, Türkmen A, Erden S. Assessment of the risk factors for intraoperative pressure injuries in patients. J Tissue Viability 2023; 32: 349–354. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtv.2023.04.006.

42. Chung ML, Widdel M, Kirchhoff J, et al. Risk factors for pressure ulcers in adult patients: A meta-analysis on sociodemographic factors and the Braden scale. J Clin Nurs 2023; 32: 1979–1992. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.16260,

43. Moore ZE, Patton D. Risk assessment tools for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 1: CD006471. pub4. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006471.pub4

44. Saleh M, Anthony D, Parboteeah S. The impact of pressure ulcer risk assessment on patient outcomes among hospitalised patients. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 1923–1929. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02717.x.

45. Webster J, Coleman K, Mudge A, et al. Pressure ulcers: effectiveness of risk-assessment tools. A randomised controlled trial (the ULCER trial). BMJ Qual Saf 2011; 20: 297–306. DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043109.

46. Choi KR, Ragnoni JA, Bickmann JD, Saarinen HA, Gosselin AK. Health Behavior Theory for Pressure Ulcer Prevention: Root-Cause Analysis Project in Critical Care Nursing. J Nurs Care Qual 2016; 31: 68–74. DOI: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000137.

47. Kaba E, Kelesi M, Stavropoulou A, Moustakas D, Fasoi G. How Greek nurses perceive and overcome the barriers in implementing treatment for pressure ulcers: ‚against the odds’. J Wound Care 2017; 26 (Supl. 9): S20–S26. DOI: 10.12968/jowc.2017.26.Sup9.S20.

Opis przypadku | case report

LECZENIE RAN 2025; 22 (3): 104-114

DOI: https://doi.org/10.60075/lr.v22i3.118

Wykorzystanie rekomendowanych narzędzi do oceny stanu klinicznego i monitorowania leczenia chorych z przewlekłą niewydolnością żylną i owrzodzeniem żylnym – opis dwóch przypadków klinicznych

The use of recommended tools for assessing the clinical condition and monitoring the treatment of patients with chronic venous insufficiency and venous ulcers –a description of two clinical cases

Paulina Mościcka 1,2, Katarzyna Cierzniakowska 1,3 , Justyna Cwajda-Białasik 1,2, Arkadiusz Jawień 4 , Maria T. Szewczyk 1,2

1 Katedra Pielęgniarstwa Zabiegowego, Wydział Nauk o Zdrowiu, Collegium Medicum w Bydgoszczy, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu, Polska

2 Poradnia Leczenia Ran Przewlekłych, Szpital Uniwersytecki nr 1 im. dr. A. Jurasza w Bydgoszczy, Polska

3 Klinika Chirurgii Ogólnej i Małoinwazyjnej, Szpital Uniwersytecki nr 2 im. dr. J. Biziela w Bydgoszczy, Polska

Streszczenie

Wprowadzenie: Przewlekła choroba żylna (PChŻ) stanowi istotny problem kliniczny, społeczny i ekonomiczny, a jej najbardziej zaawansowaną manifestacją są owrzodzenia goleni. Cechują się one wysokim wskaźnikiem nawrotów i długim czasem gojenia, co wymaga kompleksowego podejścia diagnostyczno-terapeutycznego.

Cel pracy: Analiza przebiegu leczenia dwóch pacjentek z owrzodzeniem żylnym kończyn dolnych oraz ocena dynamiki zmian klinicznych w odniesieniu do trzech narzędzi: klasyfikacji CEAP, skali VCSS i skali Villalta.

Materiał i metody: W pracy zaprezentowano dwa opisy przypadków chorych z owrzodzeniem żylnym kończyny dolnej leczonych w poradni leczenia ran przewlekłych. Kryteria włączenia stanowiły potwierdzenie w badaniu dupleks scan przewlekłej niewydolności żylnej oraz prawidłowa wartość wskaźnika kostka–ramię. Kryterium wyłączenia było owrzodzenie o etiologii innej niż żylna oraz wynik wskaźnika kostka–ramię powyżej lub poniżej wartości referencyjnych. Dobór pacjentów miał charakter losowy.

Wyniki: W obu opisanych przypadkach zastosowano leczenie przyczynowe w postaci kompresjoterapii oraz terapię miejscową opartą na oczyszczaniu rany, stosowaniu opatrunków specjalistycznych, antyseptyków, a także edukację. Równoległe monitorowanie procesu gojenia

4 Katedra i Klinika Chirurgii Naczyniowej i Angiologii, Szpital Uniwersytecki nr 1 im. dr. A. Jurasza, Collegium Medicum w Bydgoszczy, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu, Polska

Adres do korespondencji

Paulina Mościcka, Katedra Pielęgniarstwa Zabiegowego, Wydział Nauk o Zdrowiu, Collegium Medicum, ul. Łukasiewicza 1, 85-821 Bydgoszcz, e-mail: moscicka76@op.pl

Nadesłano: 28.09.2025; Zaakceptowano: 27.10.2025

Abstract

Introduction: Chronic venous disease (CVD) is a significant clinical, social, and economic problem, and its most advanced manifestation is leg ulcers. They are characterized by a high recurrence rate and long healing times, requiring a comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

The aim of the study: To analyze the treatment course of two patients with venous ulcers of the lower limbs and to assess the dynamics of clinical changes in relation to three tools: the CEAP classification, the VCSS scale, and the Villalta scale.

Material and methods: This study presents two case reports of patients with venous ulcers of the lower limbs. Inclusion criteria included confirmation of chronic venous insufficiency by duplex scanning and a normal ankle-brachial index. Exclusion criteria were ulcers of a non-venous etiology and an ankle-brachial index result above or below the reference values. Patient selection was random.

Results: In both cases, causal treatment was implemented in the form of compression therapy and local therapy based on wound cleansing, the use of specialized dressings, antiseptics, and education. Simultaneous monitoring of the healing process using scales allowed for an objective and subjective assessment of treatment progress. In both cases,

przy użyciu skal pozwoliło na obiektywną i subiektywną ocenę postępów leczenia. W obu przypadkach uzyskano całkowite wygojenie ran – w 9. i 10. tygodniu terapii.

Wnioski: Skale, w tym CEAP, umożliwiły precyzyjne określenie stanu wyjściowego i końcowego, VCSS odzwierciedlała zmiany morfologiczne i stopniową poprawę stanu miejscowego, natomiast skala Villalta uchwyciła szybkie ustąpienie objawów subiektywnych i poprawę jakości życia. Wykazano, że rekomendowane skale nie są zamienne, lecz komplementarne. Ich równoległe zastosowanie dostarcza pełniejszego obrazu klinicznego, wspiera proces monitorowania skuteczności leczenia i może przyczynić się do zmniejszenia ryzyka nawrotów owrzodzeń.

Słowa kluczowe: przewlekła niewydolność żylna, owrzodzenie żylne, skale kliniczne.

Wprowadzenie

Przewlekła choroba żylna (PChŻ) to postępujące i często niedoceniane schorzenie, charakteryzujące się wysoką częstością występowania w populacji ogólnej oraz znaczącym wpływem klinicznym, społecznym i ekonomicznym [1]. Obejmuje ona szerokie spektrum nieprawidłowości żylnych, w których powrót krwi jest poważnie upośledzony. W patofizjologii PChŻ wzajemne oddziaływanie czynników genetycznych i środowiskowych jest odpowiedzialne za wzrost ciśnienia żylnego, które prowadzi do istotnych zmian w całej strukturze i funkcjonowaniu układu żylnego [2]. Co istotne, termin przewlekła choroba żylna należy odróżnić od przewlekłej niewydolności żylnej (PNŻ). Przewlekła choroba żylna obejmuje morfologiczne i czynnościowe nieprawidłowości układu żylnego [3], natomiast PNŻ odnosi się do najcięższych postaci choroby, w których występują objawy kliniczne, takie jak żylaki, obrzęki, zmiany troficzne skóry, a w zaawansowanym stadium także owrzodzenia żylne. Chorobie tej towarzyszą również dolegliwości subiektywne, m.in. ból, kurcze mięśni, parestezje czy świąd [4, 5].

Owrzodzenia żylne stanowią 70–90% ran zlokalizowanych w okolicy kończyn dolnych [6]. Częstość ich występowania wzrasta wraz z wiekiem, a kobiety są trzykrotnie bardziej narażone na rozwój rany niż mężczyźni [7]. Duże znaczenie ma obecność czynników dziedzicznych, rasowych, a także nadwaga, przebyte ciąże, typ aktywności zawodowej, zaburzenia statyki stopy, nadmierna ekspozycja na działanie słońca, typ aktywności sportowej, dieta ubogoresztkowa i zaparcia [8, 9]. Trzymiesięczny wskaźnik gojenia owrzodzeń szacuje się na 30–60% [10–12], a mediana czasu ich trwania waha się od 6 miesięcy [13–15] do kilkudziesięciu lat [16]. Wskaźnik nawrotów jest wysoki – w niektórych krajach wynosi

complete wound healing was achieved – at weeks 9 and 10 of therapy.

Conclusions: The scales, including the CEAP, enabled precise determination of baseline and final status; the VCSS reflected morphological changes and gradual improvement in local conditions, and the Villalta scale captured the rapid resolution of subjective symptoms and improved quality of life. It was demonstrated that the recommended scales are not interchangeable, but complementary. Their simultaneous use provides a more comprehensive clinical picture, supports the process of monitoring treatment effectiveness, and may contribute to reducing the risk of ulcer recurrence.

Key words: chronic venous insufficiency, venous ulcer, clinical scales.

nawet 70% [17, 18]. U około 80% pacjentów nawrót występuje w ciągu 3 miesięcy od wygojenia [16], a około 26% owrzodzeń nawraca w ciągu pierwszych 12 miesięcy od zakończenia terapii [19]. Do oceny stanu chorego i planowania leczenia można wykorzystać dostępne narzędzia klasyfikacyjne, które pozwalają uwzględnić wiele czynników klinicznych oraz monitorować zmiany w czasie. W niniejszej pracy zastosowano trzy rekomendowane w literaturze narzędzia: klasyfikację CEAP (tab. 1), skalę Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS; tab. 2) oraz skalę Villalta (tab. 3) [20–24].

Celem pracy jest przedstawienie procesu leczenia dwóch losowo wybranych chorych z owrzodzeniem żylnym kończyny dolnej oraz ocena dynamiki zmian klinicznych w odniesieniu do zastosowanych skal.

Materiał i metody

W pracy zaprezentowano dwa opisy przypadków chorych z owrzodzeniem żylnym kończyny dolnej leczonych w Poradni Leczenia Ran Przewlekłych. Kryterium włączenia było potwierdzenie w badaniu duplex scan przewlekłej niewydolności żylnej oraz prawidłowa wartość wskaźnika kostka–ramię (WKR). Do badania nie zakwalifikowano chorych z owrzodzeniem o etiologii innej niż żylna oraz z wynikiem WKR powyżej lub poniżej wartości referencyjnych. Dobór pacjentów miał charakter losowy. W skład zespołu badawczego wchodził wykwalifikowany zespół pielęgniarski oraz lekarz, który pełnił funkcję konsultacyjną. Proces terapeutyczny, w tym diagnostyka i ocena wartości WKR, były wykonywane przez pielęgniarki posiadające wieloletnie doświadczenie kliniczne w leczeniu ran o etiologii naczyniowej oraz pracowników naukowo-dydaktycznych.

Tabela 1. Klasyfikacja CEAP [17, 25]

Komponent

C – Clinical (kliniczny)

E – Etiology (etiologia)

A – Anatomy (anatomia)

P – Pathophysiology (patofizjologia)

Kategorie

C 0 Brak objawów

Opis

C 1 Teleangiektazje, żyły siateczkowate

C 2 Żylaki

C 3 Obrzęk

C 4a Przebarwienia, wyprysk żylny

C4b Lipodermatoskleroza, atrophie blanch e

C 4c Corona phlebectatica (siateczka drobnych żyłek wokół kostki)

C 5 Wygojone owrzodzenie żylne

C 6 Czynne owrzodzenie żylne

C 6r Owrzodzenie nawrotowe

E p Pierwotna

Esi Wtórna (np. pozakrzepowa)

E c Wrodzona

E n Nieokreślona

A s Żyły powierzchowne (np. odpiszczelowa, odstrzałkowa)

Ad Żyły głębokie (np. udowa, podkolanowa)

A p Żyły przeszywające (perforatory)

A n Nieokreślone

P r Refluks

P r Niedrożność

P r,o

Refluks i niedrożność

P n Nieokreślone

Tabela 2. Zmieniona skala VCSS klinicznej ciężkości choroby żylnej [18, 19]

Brak: 0 Łagodny: 1 Umiarkowany: 2 Ciężki: 3

Ból

Żylaki

Obrzęk żylny

Przebarwienia

Nie występuje

Sporadycznie, nie ogranicza dziennej aktywności

Nie występują Pojedyncze żylaki

Nie występuje

Nie występują lub miejscowo

Zapalenie Nie występuje

Stwardnienie Nie występuje

Ograniczony do stopy i kostek

Ograniczone, okołokostkowe

Umiarkowany cellulitis, owrzodzenie okołokostkowe

Ograniczone do obszaru okolicy kostki

Codziennie, wpływa na aktywność, ale jej nie zaburza

Ograniczone do goleni lub uda

Powyżej kostek, ale ograniczony do goleni

Codziennie, ograniczający aktywność

Obejmujące goleń i udo

Dotyczący goleni i powyżej

Rozsiane, poniżej 1/3 goleni Rozlane, powyżej 1/3 goleni

Rozsiane poniżej 1/3 goleni Rozlane powyżej 1/3 goleni

Rozsiane poniżej 1/3 goleni Rozlane powyżej 1/3 goleni

Liczba owrzodzeń 0 1 2 3 i więcej

Czas trwania owrzodzenia – < 3 miesięcy > 3 i < 12 miesięcy Niewyleczone

Rozmiar owrzodzenia – < 2 cm 2–6 cm > 6 cm

Stosowanie kompresjoterapii Niestosowana Czasem Większość dni Cały czas

Tabela 3. Skala Villalta PTS [29, 32]

Objawy/oznaki

kliniczne Brak Łagodny Średni Ciężki

OBJAWY

Ból

Skurcze

Ciężkość

Parestezje

Świąd

OBJAWY KLINICZNE

Obrzęk

Stwardnienie skóry

Przebarwienia

Zaczerwienienie

Poszerzenia żył

Ból przy ucisku goleni 0 punktów

Owrzodzenie żylne Brak Obecne

Opis przypadku nr 1

Pacjentka, lat 76, zgłosiła się do Poradni Leczenia Ran Przewlekłych Szpitala Uniwersyteckiego nr 1 im. dr. A. Jurasza w Bydgoszczy z powodu owrzodzenia kończyny dolnej lewej.

Badanie podmiotowe

• Rana powstała około 4 miesiące wcześniej.

• Owrzodzenie o charakterze nawrotowym, pierwsze powstało 35 lat temu, obecnie jest to 5. nawrót.

• Pacjentka do tej pory leczona doraźnie w różnych placówkach m.in.: POZ, poradni dermatologicznej, poradni chirurgicznej, punktach opieki farmaceutycznej.

• Miejscowo stosowano różne opatrunki specjalistyczne, maści, „przymoczki”, antybiotyki.

• Kompresjoterapię stosowano okazjonalnie.

• Choroby współistniejące – nadciśnienie tętnicze, około 45 lat temu przebyta zakrzepica żył głębokich (w okresie połogu) i od tego czasu chora zażywa leki antykoagulacyjne.

• Dolegliwości bólowe – 7/10 pkt w skali wizualno-analogowej (Visual Analogue Scale – VAS).

Badanie przedmiotowe

• Wskaźnik kostka–ramię: kończyna dolna prawa – 1,15, kończyna dolna lewa – 1,17.

• Wynik badania duplex scan: niewielki 1-sekundowy refluks w ujściu żyły udowej, poza tym żyła udowa podatna cienkościenna. W obrębie żyły podkolanowej widoczne zmiany pozakrzepowe w postaci pogrubienia i nieregularności ściany

naczynia, z obecnością zwłóknień i zniekształceń światła. Ujścia i pnie żył odpiszczelowych i odstrzałkowych wydolne. Na przyśrodkowej powierzchni 1/3 uda od żyły odpiszczelowej odchodzi żylakowato zmieniona obocznica, która podąża po stronie przyśrodkowej kończyny do wysokości 1/2 goleni, gdzie uchodzi do żył głębokich przez niewydolny perforator Cocketta III. Poza tym niewydolnych perforatorów nie wykazano.

• Ocena według klasyfikacji CEAP – C2,4a,b,6, Es, Asdp, Pr,o: C 2 – żylaki kończyn dolnych, C4a – pigmentacja lub egzema, C4b – lipodermatoskleroza lub biała atrofia, C6 – owrzodzenie, Esi – wtórne, np. pozakrzepowe, Asdp – układ powierzchowny, przeszywający i głęboki, Pr,o – refluks i niedrożność.

• Ocena według skali VCSS – 16 pkt: ból – 3, żylaki – 2, obrzęk – 1, pigmentacja skóry – 2, zapalenie – 1, stwardnienie – 1, liczba aktywnych owrzodzeń – 1, czas trwanie owrzodzenia – 2, rozmiar owrzodzenia – 3, stosowanie kompresjoterapii – 1.

• Ocena według skali Villalta – 17 pkt: ból – 3, skurcze – 2, ciężkość – 3, parestezje – 0, świąd – 1, obrzęk – 1, stwardnienie skóry – 1, zaczerwienienie – 1, poszerzenia żył – 2, ból przy ucisku goleni – 0, owrzodzenie żylne – 3.

Opis owrzodzenia i otaczającej skóry

Rana zlokalizowana na kończynie dolnej lewej w okolicy kostki przyśrodkowej, o łącznej powierzchni 39,75 cm 2 i głębokości 0,3 cm. Łożysko

P. Mościcka, K. Cierzniakowska, J. Cwajda-Białasik i wsp.

rany pokryte w 70% żółtą martwicą, 20% stanowiła niepełnowartościowa ziarnina, a 10% powierzchni stanowił naskórek. Całą powierzchnię rany pokrywał biofilm. Brzeg owrzodzenia, zwłaszcza jego górna i przyśrodkowa krawędź, wyraźnie zaznaczone, miejscami przysłonięte włóknikiem, pozostałe krawędzie rany z cechami epitelizacji. Skóra w okolicy getrowej znacznie wysuszona, pergaminowa, z cechami hemosyderozy, lipodermatosklerozy, a wokół owrzodzenia zaczerwieniona, w dolnym biegunie rany zmacerowana.

Postępowanie pielęgnacyjno-lecznicze

Z powierzchni rany pobrano materiał do badania mikrobiologicznego, na podstawie którego wyizolowano Proteus mirabilis 104 , Staphylococcus aureus 102 Po przeanalizowaniu wyniku mikrobiologicznego oraz po ocenie stanu klinicznego podjęto decyzję o wyłącznie miejscowym leczeniu przeciwdrobnoustrojowym. Łożysko rany było systematycznie oczyszczane z tkanek martwych, resztek zrogowaciałego naskórka, pozostałości wysięku. Ranę opracowywano mechanicznie, sięgając 1–2 mm w głąb żywej tkanki, tak aby zwiększyć prawdopodobieństwo usunięcia wszystkich struktur ułatwiającym bakteriom wytwarzanie biofilmu. Jednocześnie monitorowano stan rany pod kątem ryzyka wystąpienia krwawienia. W celu eradykacji drobnoustrojów chorobotwórczych na powierzchnię rany stosowano antyseptyk o szerokim spektrum działania. Podczas pierwszej i drugiej wizyty, przed oczyszczeniem łożyska rany, choremu zalecono zażycie doustnego leku przeciwbólowego. W kolejnych etapach leczenia pacjent nie odczuwał dolegliwości bólowych.

Tabela 4. Przebieg procesu leczenia

W początkowym etapie stosowano opatrunki przeciwdrobnoustrojowe o właściwościach chłonnych, następnie postępowanie miejscowe było uzależnione od stanu klinicznego rany i modyfikowane podczas każdej wizyty. Częstotliwość zmian opatrunków ulegała stopniowej redukcji, w początkowym etapie konieczna zmiana co dwa dni, następnie dwa razy w tygodniu i w końcowym etapie raz na tydzień. Od początku leczenia u chorej włączono kompresjoterapię dwuwarstwową, aplikując ciśnienie w okolicy kostki w zakresie pomiędzy 41 a 50 mm Hg [25]. Pacjentkę poddawano systematycznej edukacji, m.in.: w zakresie stosowania terapii kompresyjnej, ćwiczeń usprawniających pracę stawu skokowego i pompy mięśniowej, odpowiedniej diety, zgodnej ze schematem postępowania dietetycznego w Poradni Leczenia Ran Przewlekłych i leczniczego w tym zakresie [26, 27].

Uzyskany efekt

W trakcie prowadzonej terapii odnotowano istotny postęp procesu gojenia. W pierwszym etapie doszło do oczyszczenia łożyska rany z tkanek martwiczych, co zapoczątkowało kolejne fazy gojenia. Po 9 tygodniach intensywnej terapii uzyskano pełne wygojenie owrzodzenia. Skala VCSS dobrze odzwierciedliła proces gojenia – od stanu ostrego do utrwalonych następstw, z redukcją punktacji z 18 do 9. Skala Villalta była bardziej czuła na poprawę subiektywnych objawów i wygojenie rany, co przełożyło się na szybszy spadek wartości (z 21 do 5 punktów). Zgodnie z klasyfikacją CEAP po wygojeniu owrzodzenia kategoria C6 została zastąpiona kategorią C5 (tab. 4, tab. 5).

Tydzień terapii Powierzchnia w cm2 Skala CEAP Skala VCSS Skala Villalta

1. 39.75 (ryc. 1) C2,4a,b,6r,Esi,Asdp, Pr,o 18 pkt 21 pkt

5. 12 (ryc. 2) - 14 8

9. 0 (ryc. 3) C2, 4a,b,5, Esi,Asdp, Pr,o 9 5

5. Ocena dynamiki zmian na podstawie skal: VCSS i Villalta

tydzień 5. tydzień 9. tydzień Skala VCSS

Tabela

1.

Opis przypadku nr 2

Chora, lat 67, została przyjęta do Poradni Leczenia Ran Przewlekłych Szpitala Uniwersyteckiego nr 1 im. dr. A. Jurasza w Bydgoszczy z powodu niegojącego owrzodzenia żylnego kończyny dolnej lewej.

Badanie podmiotowe

• Rana powstała 6 miesięcy wcześniej.

• Do tej pory stosowano wyłącznie terapię miejscową, niestandardową, w postaci maści z antybiotykami lub glikokortykosteroidami.

• Chorej wcześniej przed przyjęciem do Poradni

Ran Przewlekłych

Rycina 1. Stan rany u 76-letniej chorej w tygodniu 1. Rycina 2. Stan rany u 76-letniej chorej w tygodniu 5.

Rycina 3. Stan rany u 76-letniej chorej w tygodniu 9.

P. Mościcka, K. Cierzniakowska, J. Cwajda-Białasik i wsp.

zakazano mycia skóry (kończyna przez 6 miesięcy nie była umyta).

• Choroby współistniejące: nadciśnienie tętnicze.

• Brak stosowania kompresjoterapii.

• Dolegliwości bólowe na poziomie 4/10 pkt w skali VAS.

• Dokuczliwy świąd, zwłaszcza w okolicy getrowej

Badanie przedmiotowe

• Wskaźnik kostka–ramię: kończyna prawa – 1,2, kończyna lewa – 1,1.

• Wynik badania duplex scan: żyła głęboka uda i powierzchowna drożne, żyła podkolanowa i w żyłach goleni bez patologii. Niewydolne ujście żyły odpiszczelowej, refluks na całej długości. Żyła odstrzałkowa wydolna. Widoczny refluks w perforatorze Cocketta II i III, utrzymujący się powyżej 0,5 sekundy.

• Ocena według klasyfikacji CEAP – C2,4a,6, Ep, As,p, Pr: C 2 – żylaki kończyn dolnych, C4a – pigmentacja lub egzema, C6 – owrzodzenie, Ep – etiologia pierwotna, Asp – układ powierzchowny, przeszywający, Pr – refluks.

• Ocena według skali VCSS – 12 pkt: ból – 1, żylaki – 1, obrzęk – 1, przebarwienia – 1, zapalenie – 1, stwardnienie – 1, liczba owrzodzeń – 1, czas trwanie owrzodzenia – 2, rozmiar owrzodzenia – 3, stosowanie kompresjoterapii – 0.

• Ocena według skali Villetla – 15 pkt: ból – 1, skurcze – 1, ciężkość – 1, parestezje – 0, świąd – 3, obrzęk – 1, stwardnienie skóry – 1, zaczerwienienie – 1, poszerzenia żył – 1, ból przy ucisku łydki – 0, owrzodzenie żylne – 3.

Opis owrzodzenia i otaczającej skóry

Rana zlokalizowana na kończynie dolnej lewej po stronie przyśrodkowej. Owrzodzenie o powierzchni 52,25 cm2

Tabela 6. Przebieg procesu leczenia

pokryte w 75% żółtą martwicą, 20% powierzchni rany stanowiła ziarnina, a pozostałe łożysko rany wypełniał naskórek. Brzeg rany nieregularny i rozmyty, w górnym biegunie nieco wyraźniej zaznaczony. Rana obficie wydzielająca. Wysięk z rany miał charakter surowiczy i był bezwonny. Skóra otaczająca owrzodzenie przebarwiona, z obrzękiem okolicznych tkanek, z cechami maceracji zwłaszcza w części dystalnej.

Postępowanie pielęgnacyjno-lecznicze

Z powierzchni rany pobrany został materiał do badania mikrobiologicznego, z którego wyhodowano Streptococcus β-hemolizujacy grupy „C”2. Po przeanalizowaniu wyniku bakteriologicznego i ocenie całościowego stanu klinicznego, podjęto decyzję o zastosowaniu miejscowego leczenia przeciwdrobnoustrojowego. Podczas każdej wizyty rana i skóra otaczająca owrzodzenie, była dokładnie myta i oczyszczana w sposób mechaniczny. W celu eradykcji drobnoustrojów chorobotwórczych na powierzchnię rany aplikowano antyseptyk o szerokim spektrum działania. Podczas pierwszej wizyty choremu zalecono, aby przed oczyszczeniem powierzchni rany zażył doustny lek przeciwbólowy. W kolejnych etapach leczenia pacjent nie wymagał leczenia przeciwbólowego. W początkowym etapie stosowano opatrunki piankowe o właściwościach przeciwdrobnoustrojowych. Następnie, w zależności od stanu klinicznego rany – w tym fazy gojenia i ilości wysięku – modyfikowano postępowanie miejscowe. W końcowym etapie procesu gojenia stosowano opatrunki siatkowe. W pierwszym tygodniu terapii opatrunki zmieniano co 1–2 dni, natomiast w dalszym okresie – ze względu na poprawę stanu klinicznego – co 3 dni. Skórę wokół owrzodzenia zabezpieczano przeznaczonym do tego celu emolinetem. Od początku terapii włączono terapię uciskową w formie

Tydzień terapii Powierzchnia w cm2 Skala CEAP Skala VCSS Skala Villalta

1. 52,25 (ryc. 4) C2,4a,6, Ep, As,p, Pr 12 pkt 15 pkt

6. 18,75 (ryc. 5) - 11 7

10. 0 (ryc. 6) C2, 4a,b,5, Es, Asdp, Pr,o 7 3

Tabela 7. Ocena dynamiki zmian na podstawie skal: VCSS i Villalta

VCSS

specjalistycznych bandaży typu short-stretch, aplikując ciśnienie w okolicy kostki 31–40 mm Hg. Przebieg procesu leczenia przedstawiono w tabelach 6 i 7.

Uzyskany efekt

W trakcie terapii odnotowano systematyczny postęp procesu gojenia. Początkowo powierzchnia owrzodzenia wynosiła 52,25 cm², a pacjentka spełniała kryteria CEAP C6. W 6. tygodniu terapii powierzchnia rany zmniejszyła się do 18,75 cm², a w 10. tygodniu uzyskano całkowite wygojenie owrzodzenia. Skala VCSS potwierdziła

Rycina 6. Stan rany u 67-letniej chorej w tygodniu 10.

Rycina 5. Stan rany u 67-letniej chorej w tygodniu 6.

Rycina 4. Stan rany u 67-letniej chorej w tygodniu 1.

P. Mościcka, K. Cierzniakowska, J. Cwajda-Białasik i wsp.

się z 12 do 7, odzwierciedlając redukcję zarówno objawów, jak i zmian miejscowych. Skala Villalta wykazała jeszcze większą dynamikę zmian, z 15 punktów w 1. tygodniu do 3 punktów w 10. tygodniu, co wskazuje na szybkie ustąpienie objawów subiektywnych i znaczną poprawę komfortu chorej. W klasyfikacji CEAP końcowa ocena zmieniła się z C6 na C5, co dokumentuje przejście od fazy aktywnego owrzodzenia do fazy przebytego owrzodzenia żylnego.

Omówienie

Mimo upływu lat w ocenie PChŻ wciąż wykorzystuje się klasyczne narzędzia, takie jak klasyfikacja CEAP, skala VCSS oraz skala Villalta. Powstały w różnych okresach i dla odmiennych celów, jednak nadal są rekomendowane w literaturze i przydatne w codziennej praktyce klinicznej, ponieważ dostarczają uzupełniających informacji na temat stanu pacjenta. Każde z wymienionych narzędzi pełni odmienną funkcję i pozwala na analizę zarówno następstw morfologicznych, jak i subiektywnych objawów choroby, co ma istotne znaczenie w całościowej ocenie przebiegu PChŻ oraz skuteczności leczenia. Należy jednak podkreślić, że skale kliniczne mają charakter uzupełniający, podczas gdy podstawą diagnostyki przewlekłej choroby żylnej pozostaje badanie ultrasonograficzne metodą duplex scan [28]. Badanie obrazowe umożliwia m.in. identyfikację pacjentów z nadciśnieniem żylnym, którzy mogą odnieść korzyść z leczenia nieinwazyjnego lub inwazyjnego, zmniejszając tym samym ryzyko nawrotów owrzodzeń. Równie istotne jest wykluczenie współistniejącej choroby tętnic obwodowych, której obecność stwierdza się nawet u 26% pacjentów z owrzodzeniami kończyn dolnych [29–31].

Klasyfikacja CEAP stanowi od ponad dwóch dekad międzynarodowy standard w opisie PChŻ, umożliwiając dokładne określenie stopnia klinicznego (C), etiologii (E), lokalizacji anatomicznej (A) oraz mechanizmu patofizjologicznego (P). Po raz pierwszy została opublikowana w 1995 r. [20], następnie zaktualizowana w 2004 r. [32], a jej najnowsza rewizja pochodzi z 2020 r. [23]. W ostatniej aktualizacji dodano m.in. nowe kategorie dla corona phlebectatica (C4c), nawracających żylaków (C2r), nawracających owrzodzeń (C6r), a także wprowadzono rozróżnienie wtórnej etiologii na żylne (Esi) i pozażylne (Ese). Klasyfikacja CEAP znajduje zastosowanie głównie w diagnostyce i stratyfikacji pacjentów, natomiast jej użyteczność w monitorowaniu krótkoterminowych efektów terapii pozostaje ograniczona. W przedstawionych przypadkach klasyfikacja CEAP pozwoliła jednoznacznie określić

stan początkowy (C6) i końcowy (C5), stanowiąc punkt odniesienia w procesie leczenia. Skala VCSS została opracowana jako narzędzie uzupełniające CEAP, której statyczny charakter uniemożliwiał monitorowanie dynamiki choroby i efektów leczenia. Po raz pierwszy została zaproponowana w 2000 r. przez Rutherforda i wsp. jako element ujednoliconej oceny ciężkości PChŻ i reakcji na terapię [33]. W kolejnych latach Meissner i wsp. ocenili jej właściwości kliniczne, a Vasquez i wsp. zaproponowali rewizję i dalsze udoskonalenie [21, 34]. Skala obejmuje dziesięć parametrów klinicznych (m.in. ból, żylaki, obrzęk, przebarwienia, zapalenie, stwardnienie skóry, liczbę i czas trwania owrzodzeń, ich wielkość oraz stosowanie kompresjoterapii), z punktacją 0–3 dla każdego objawu. Skala VCSS pozwala na dynamiczną, okresową ocenę pacjenta – ustalenie stanu wyjściowego, obserwację progresji oraz analizę skuteczności leczenia (progresja/regresja/brak wpływu) [35]. W analizowanych przypadkach skala ta pozwoliła uchwycić stopniową poprawę stanu miejscowego – punktacja obniżyła się u pierwszej chorej z 18 do 9 i u drugiej z 12 do 7 – jednocześnie uwidaczniając utrwalone następstwa PChŻ, które pozostają mimo wygojenia rany.