Mobile Bay

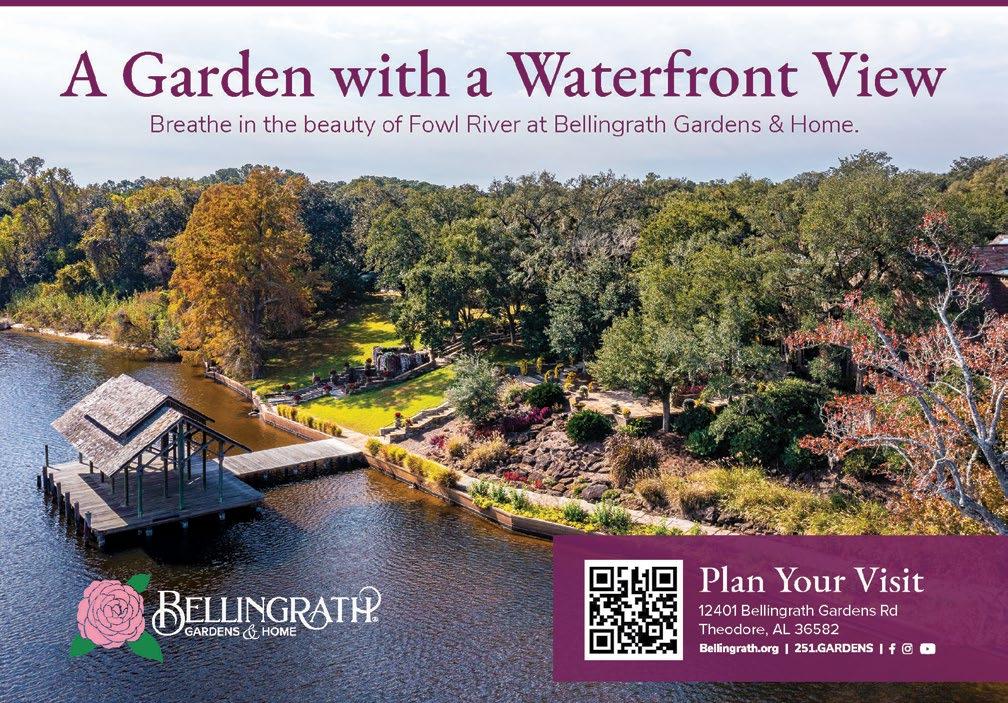

DIVE INTO LIFE ON FOWL RIVER

LIFE IS GOOD ON THE COAST FOR THESE FOUR-LEGGED READERS

RAYZA’S PERFECT RECIPE FOR TUNA TATAKI

THE LIVING IS EASY DOWN COUNTY RD 1

PLUS!

MEET THE ENVIRONMENTAL SUPERSTARS OF OUR ANNUAL WATERSHED AWARDS

DIVE INTO LIFE ON FOWL RIVER

LIFE IS GOOD ON THE COAST FOR THESE FOUR-LEGGED READERS

RAYZA’S PERFECT RECIPE FOR TUNA TATAKI

THE LIVING IS EASY DOWN COUNTY RD 1

PLUS!

MEET THE ENVIRONMENTAL SUPERSTARS OF OUR ANNUAL WATERSHED AWARDS

Meet eight local heroes working to preserve and protect our waters for future generations

Dive deep into this local waterway, from its headwaters to its delta, sharing in the good life along the way

Cold holes in Fowl River are naturally-occurring deep pockets where underground springs feed into the main channel, lowering the water’s temperature. Learn more about the area’s unique features, history and residents on page 52.

ON OUR COVER

Golden Retriever Asher spends a quiet sunrise on the weathered boards of the old family wharf on Mobile Bay. “It was our happy place that is missed dearly.”

64 ARCHIVES

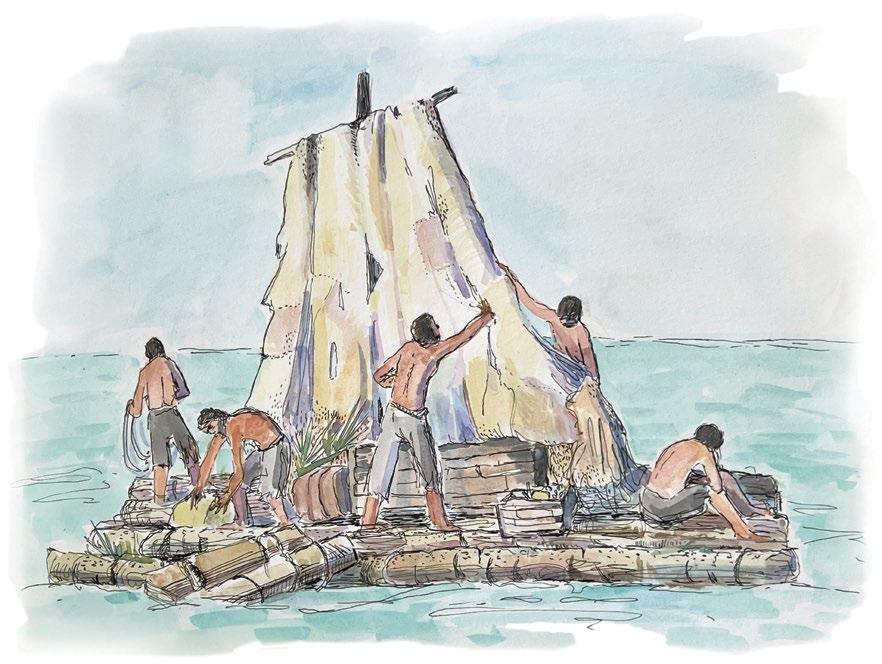

Two men vanish without a trace on Mobile Bay during the Narváez expedition of 1528

Shipp’s

continues a

a

Paddle along on a local’s solo journey across the waters of Mobile Bay

Local sushi expert

Mochamad Rayza shares fresh fish prep tips

Celebrate our coastal culture with snapshots of local soggy dogs 33

Walks on the beach turn sandy trinkets into nautical sculptures

One couple welcomes generations to a waterside retreat on County Road 1 in Fairhope 60

68 MARITIME

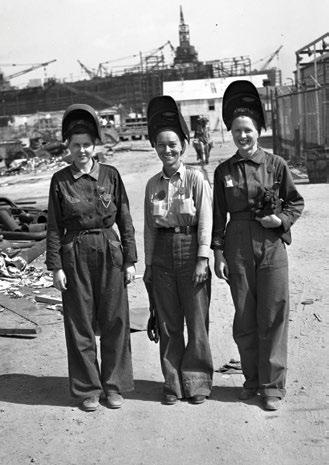

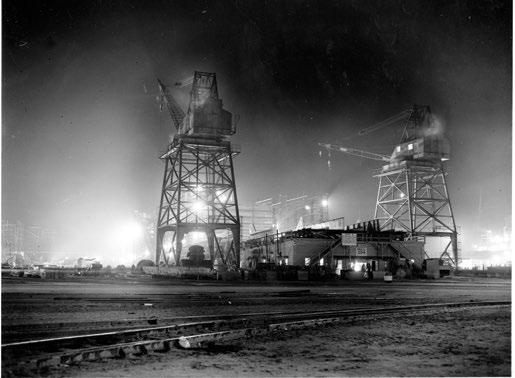

How ADDSCO impacted Mobile’s industry during World War II

72 ASK MCGEHEE

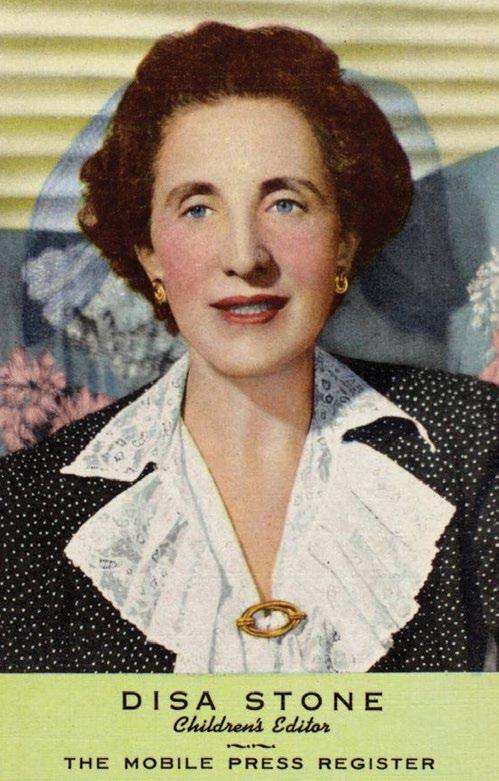

Who was Disa Stone?

74 ENDPIECE

Gather crabs with a Fairhope family in the 1920s

VOLUME XLI

JULY 2025 No7

PUBLISHER T. J. Potts

ASSISTANT PUBLISHER Stephen Potts

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Maggie Lacey

DIGITAL DIRECTOR Abby Parrott

ART DIRECTOR Deanna Gardner

STAFF WRITER Amelia Rose Zimlich

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Mary Ryan Kirsch

ADVERTISING

SALES DIRECTOR Walker Sorrell

SR. ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE Joseph A. Hyland

ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE Jennifer Ray

PRODUCTION Peri Carr

ADMINISTRATION

ACCOUNTING Keith Crabtree

PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT Rachel Mayhall

EVENTS COORDINATOR Frances Hurley

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Emmett Burnett, Catherine Dorrough, Scotty Kirkland, Cam Marston, John Sledge

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Colleen Comer, Matthew Coughlin, Elizabeth Gelineau, Kathy Hicks, Courtney Mason, Chad Riley, Laura Rowe

ADVERTISING AND EDITORIAL OFFICES 166 Government Street, Suite 208 Mobile, AL 36602-3108 251-473-6269

PUBLISHED BY PMT PUBLISHING INC .

PRESIDENT & CEO T. J. Potts

PARTNER & DIRECTOR Thomas E. McMillan

Subscription inquiries and all remittances should be sent to: Mobile Bay c/o Cambey & West P.O. Box 43 Congers, NY 10920-9922 1-833-454-5060

MOVING?

Please note: U.S. Postal Service will not forward magazines mailed through their bulk mail unit. Please send old label along with your new address four to six weeks prior to moving.

Mobile Bay is published 12 times per year for the Gulf Coast area. All contents © 2023 by PMT Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of the contents without written permission is prohibited. Comments written in this magazine are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the ownership or the management of Mobile Bay. This magazine accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts, photography or artwork. All submissions will be edited for length, clarity and style.

SCAN THIS CODE TO SUBSCRIBE OR GIVE A GIFT SUBSCRIPTION!

Dogs and water just go together, don’t you think? There is nothing quite like the happiness spread across the face of a sandy, wet canine fetching a stick through brackish waves. We adopted our first dog Fourth of July weekend about a year after getting married, and immediately introduced her to life on the Bay. A friend came to pick us up by boat for a holiday on the water, and our newly-rescued shelter dog was understandably hesitant to board the bobbing watercraft. I felt sorry for her, and worried, and attempted to take her back inside. My pragmatic friend said, “Do you want her to be a boat dog or not?” Point taken. There is no time like the present. We scooped her up, climbed aboard and the rest was history. She spent a long and happy life barking at pelicans, jumping off the wharf after tennis balls and frolicking in the sand at Pirate’s Cove. Who knew terrier mixes loved the water so much?

Last year we adopted a new dog — another spotted mutt in need of a home. On her first day as a member of our family, we took her to the water. She tentatively walked over wharf boards and cowered whenever a wave passed by, unsure of this weird new environment. But you should see her now! She chases waves and attempts to bite the foam, taking down her assailant with gusto. She never tires of it, and the waves never cease crashing on the shore, so it’s a good game. She returns home with sand in places I can’t imagine and water stuck deep in her hound dog ears, but happy as a clam.

This month we asked readers to share photos of their soggy doggies, and we found that you are just as enamored of your water-loving pups as I am. My inbox was flooded with golden retrievers, labs and mutts of all stripes enjoying the good life at the beach and on the Bay. We even had a Gravine Island pup or two! It seems life on the coast is as good for the four-legged locals as it is for the rest of us.

Our annual coastal issue is always a reader favorite, and a favorite of mine. This month we took a slow boat up Fowl River, diving deep into the history, recreation and culture of life in south Mobile County. We spent the day down County Road 1 in Fairhope, cooking up summer staples like fresh corn and tomato sandwiches, not to mention a recipe I have never before tried — grilled crabs! We followed along as Cam Marston attempted to paddle across the entirety of the Bay — no small feat, with no chase boat in sight. We learned about Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Co., where my grandfather worked during the War. And of course, we honored our annual Watershed Award winners, those locals working hard in big and small ways to protect our shores and the quality of the water we so dearly love.

It’s a salty issue brimming with all the reasons to love life in coastal Alabama. Grab a towel and dive in!

Maggie Lacey EXECUTIVE EDITOR maggie@pmtpublishing.com

FOURTH OF JULY ENTERTAINING HAS NEVER BEEN MORE BEAUTIFUL WITH THIS GLASS FISH PLATTER FROM VIETRI. AVAILABLE AT IVY COTTAGE A DAY ON THE WATER CALLS FOR A SERIOUSLY COOL FLOAT, LIKE THIS GIANT SNAKE. SUNNYLIFE.COM EVERY WATERLOGGED DOG NEEDS A COLLAR TO MATCH THEIR WET AND WILD PERSONALITY. I LOVE THIS BIG GAME FISH VERSION FROM GUY HARVEY.

WHILE CAM MARSTON PADDLED WHAT HE CALLS A BANDAID-SHAPED BOARD ACROSS THE BAY, HIS FRIEND BRAD FRIESEN PADDLED THIS PENCIL-SHAPED CRAFT THE LENGTH OF THE STATE OF ALABAMA IN THE AL-650 RACE IN 2023. FOLLOW ALONG ON PAGE 18

ADDING A DRY AGER TO MY “WHEN I WIN THE LOTTERY” SHOPPING LIST SO I CAN MAKE INSANELY DELICIOUS TUNA RECIPES LIKE RAYZA. THIS ONE IS THE DX500. TRY A RECIPE, PAGE 24

MY GRANDFATHER, JOHN T. BAGWELL, SEEN HERE AT HIS DESK AT ALABAMA DRY DOCK AND SHIPBUILDING CO. IN 1943, WHERE HE HELPED TRAIN ALABAMA FARM BOYS TO BUILD SHIPS FOR WWII. MORE ON ADDSCO, PAGE 68

On our piece about the nostalgia and simplicity of summer camps

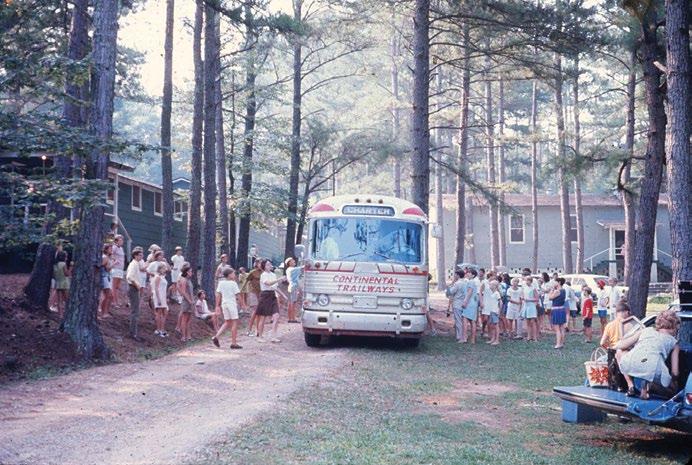

“I happened to read your article ‘Happy Camper’ the very day I found my Camp Kanuga wooden name tags (circa 1986 and beyond) in a dusty box in the attic of my parents’ home. Thank you for your perfect echo of my sentiment on the merits, simplicities and long-lasting impact of summer camp. I, too, am grateful for the many gifts those summers gave me, including a sense of independence, an appreciation for the discomfort required for adventure, a curiosity about the wonders of nature and the ability to build friendships throughout my life.”

- Catherine Druhan

“I loved seeing a picture of the Mobile bus arriving at Camp Mac in Mobile Bay Magazine. I was there that and 10 other summers (a lifer, so to speak). Now my daughter is approaching her eighth summer as a second year junior counselor. She has many friends from my hometown, including several children of my friends growing up! Let the tradition continue to make for unbelievable memories, friendships, experiences, opportunities.”

- Maggie Maher Wagner

On our sweet collaboration with Cammie’s Old Dutch to create Holy Heavenly Hash ice cream

“Oh lord, I can’t wait to eat that.”

- Courtney Matthews

“My father worked at American National Bank and wrote the loan for Mr. Widemire.”

- Heidi Loudermilch

“Sigh, I’ll go grab my keys.”

- Paige Hill

On our article celebrating the 20th anniversary of Tom McGehee writing for Mobile Bay Magazine

“Kudos to Tom McGehee on his 20th anniversary as a columnist for Mobile Bay. He’s one of the city’s treasured resources, as he researches and recounts the people and places of our storied past. His work is as witty as it is informative and important. I wish him continued success.”

- Judy Culbreth

On our article about the Gulf’s golf cart culture

“In the mid 1970s, I bought my mother, Marie Pergantis, a golf cart from City Park in New Orleans to use on her 120-acre farm in Daphne. She rode it daily to plant her flowers, feed her chickens and pigs and take her dogs for a ride. Just another use for the golf carts.”

- Susan Linnon

On our article about Dauphin Island’s iconic Isle Dauphine Club

“I remember the Friday night teen dances upstairs, the days spent at the pool and the wonderful Willy’s Special sandwich in the golf shop!”

- Kristen Kammer-Hattox

Want to share your thoughts and reactions to this issue? Email maggie@pmtpublishing.com.

text by ABBY PARROTT

EFFORTLESSLY COASTAL

The “coastal grandmother” aesthetic isn’t limited to fashion. Find inspiration from some of our favorite local interior designs on the Bay and at the beach.

SHARE THE LOVE

Share your proposal story with us, and we’ll feature your engagement announcement online and on social media.

We didn’t have room to print all of the incredible pictures submitted in our Waterlogged Dogs photo contest, but you’re in luck! The full gallery of adorable pups is now available online.

Our online store is stocked for summer! Visit mobilebayshop.com to peruse our latest coastal-inspired finds.

BEAT THE HEAT

Nothing beats a cool lunch on a hot July day. Check out our 10 picnic lunch recipes, perfect for making ahead and bringing on your next outdoor adventure.

Go online for a list of the top 10 things to do in July, including cook-offs, fishing tournaments, fireworks, fundraisers and more.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Hernando Street? Maldonado Place? Learn about the 1950s initiative to boost the development of Dauphin Island and the swashbuckling street names it produced.

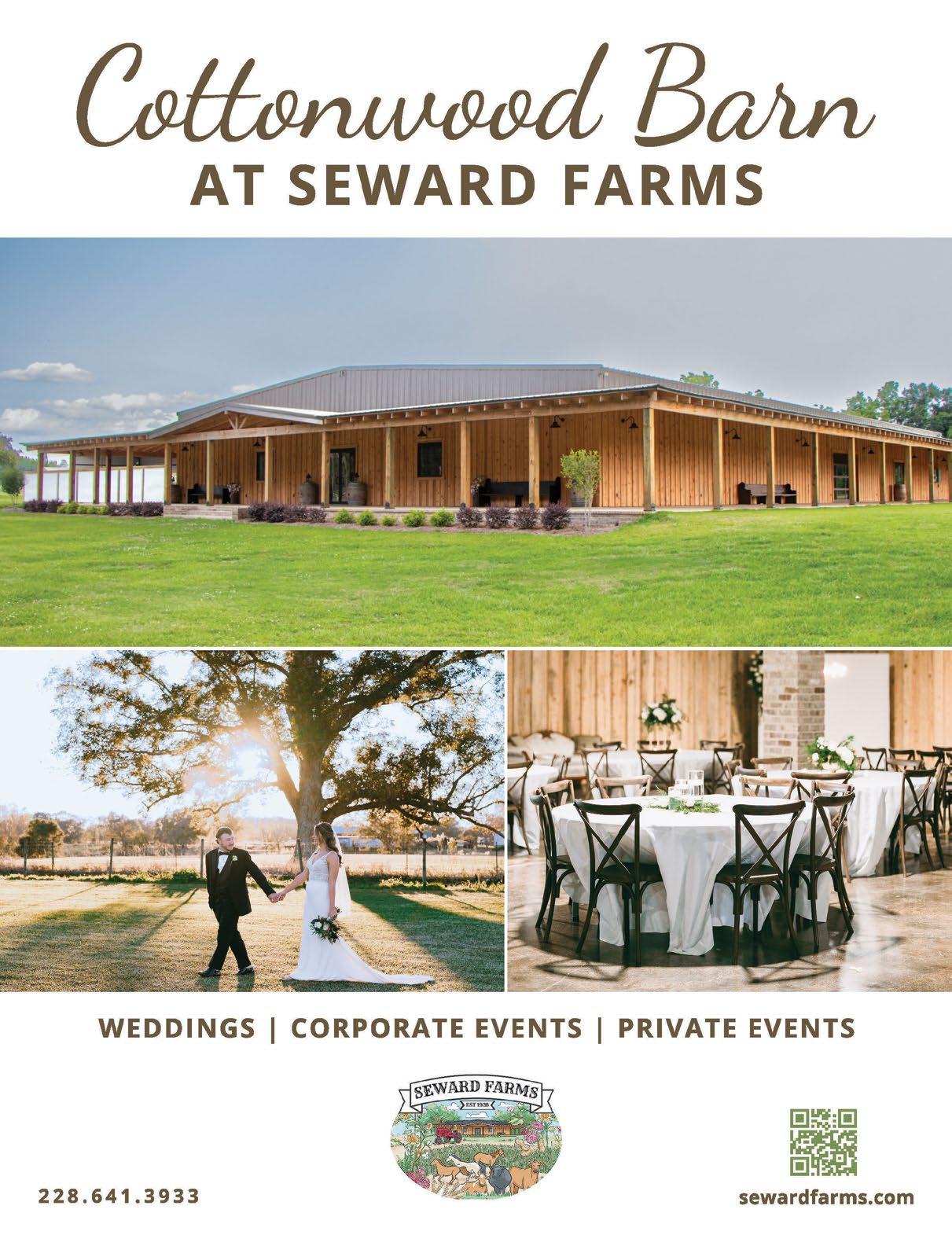

New! Scan the QR code above to browse our comprehensive wedding vendor directory and view the Web-exclusive galleries of recent local weddings.

Finally, an email you’ll actually love to read. Get the latest in food, art, homes, local history and events delivered right to your inbox. You’ll also be the first to know about new contests and exclusive deals for our online store. Sign up today!

text by MB EDITORIAL STAFF

Did you know?

Bluefin tuna are warm-blooded. They can swim nearly 30 MILES PER HOUR and they never stop swimming.

More on tuna, page 24.

The year 19-year-old Murphy graduate Gaywood Steadham swam across Mobile Bay from Arlington Park to Point Clear

Follow another epic trek across the Bay, page 18.

“Meanwhile

the Gulf, breasted, mapped, loved, and fouled, remains as ungovernable as ever, heaving to its own infinitely variable rhythms.”

— John Sledge, “Gulf of Mexico”

The name given to Fowl River by French Colonists Dive into Fowl River, page 52.

swim differently than every other type of dog, using a modified breaststroke (that I need to see to believe).

For more wet dogs, turn to page 26.

Glass is not a solid, but a very SLOWMOVING LIQUID

Glass can be infinitely recycled, so keep that liquid moving!

Meet a local salvaged glass artist, page 33.

The new restaurant from five-time James Beardnominated Chef Bill Briand (formerly of Fisher’s) has opened its doors in downtown Fairhope

MB’s contributing food fanatics share their go-to local dishes.

BUDDY BATES

Retired Vice President and Property Manager for Regions Bank

BOEUF BOURGUIGNON AT KITCHEN ON MAIN

“At Kitchen On Main, there is always a chalkboard with specials. We ordered the special of Boeuf Bourguignon and it was the most delicious tender beef served over mashed potatoes along with shareables: crab cakes and Buffalo oysters. The food was beautiful and delicious. It really is fine dining quality food in a casual, friendly atmosphere. Reservations are desired as this gem of a restaurant is usually packed. The secret is to call ahead, you won’t be sorry!”

KITCHEN ON MAIN • 1716 MAIN ST., DAPHNE 307-5350 • KITCHENONMAINDAPHNE.COM

CAM JACKSON Director of Membership, Eastern Shore Chamber of Commerce

BEEF TENDERLOIN

AT THE TRELLIS ROOM

“What more can I say about this dish other than that it is simply exquisite. The grilled beef tenderloin medallions are juicy and flavorful, with a delicious melt-in-your-mouth tenderness — you could cut them with a spoon. Tucked away inside the historic Battle House in downtown Mobile, The Trellis Room is low-key fine dining at its best, with a wonderful menu and without the crazy expensive price to match the quality.”

THE TRELLIS ROOM • 26 N ROYAL ST., MOBILE 338-2000 • TRELLISROOM.COM

TOOTS OTTS WEAVER Real Estate Agent, Courtney & Morris Real Estate

THE CRUNCHY LOBSTER AT THAI CHILLI BY SIAM

“Thai Chilli by Siam on Museum Drive in Mobile offers a standout dish: the Crunchy Lobster. This entrée features lightly battered, deep-fried lobster stir-fried with roasted chili paste, onions, bell peppers, and carrots, all topped with cashew nuts. Diners can customize the spiciness to their preference; a level 2 provides a gentle kick without overwhelming the dish’s rich flavors. The Crunchy Lobster is a flavorful option for those seeking a blend of crispy texture and savory heat.”

THAI CHILLI BY SIAM • 744 MUSEUM DRIVE, MOBILE 300-8658 • THAICHILLIBYSIAM.COM

GINNY BEHLEN Dietitian, WIC at Mobile County Health Department

COFFEE BRAISED SHORT RIBS AT THE ROYAL SCAM

“I love to dine, and, most arguably, one of the best places to do so is The Royal Scam. I ordered the coffee braised short ribs. The dark intense sauce was a perfect compliment to the tender meat. Creamy parmesan polenta was an awesome vehicle for the sauce. While the beefy comfort food is rich, polenta, which is higher in fiber and lower in carbohydrate, gave some credibility to a healthier option. Tender grilled asparagus stood up to the robust flavor of the dish and helped tie everything together.”

THE ROYAL SCAM • 72 S ROYAL ST., MOBILE • 432-7226 ROYALSCAMMOBILE.COM

What dishes made you drool and left you hungry for more? Share them on our Facebook page!

text by AMELIA ROSE ZIMLICH • photos by ELIZABETH GELINEAU

Enjoying meals on the water is a hallmark of coastal Alabama summers. If a dockside dining experience is calling your name, the perfect place is waiting for you in Orange Beach Marina with Shipp’s Dockside Grill. In the location previously home to Fisher’s, the concept serves as a new iteration of past Shipp’s restaurants gone by, including the original Shipp’s Harbor Grill in Sportsman’s Marina and Fin & Fork in Orange Beach.

Chef Matt Shipp, along with his daughter Kamila Albright, opened Shipp’s Dockside Grill in March. The double-decked restaurant provides two separate dining experiences for customers. The lower deck caters to fast-casual dining, with customers often hopping off the boat for a dockside lunch or dinner. Customers place their food orders at the front desk and drink orders at the bar before grabbing a tracker to put down at their table. When orders are ready, they are delivered by food runners. “We also have an oyster bar where you can watch oysters shucked fresh to order and get yourself a bushwacker or a frozen margarita,” says Albright. While the service is quick and efficient, you wouldn’t know it by the food quality and plethora of dishes on offer. The sushi is a bestseller, with many flavorful varieties to choose from.

Crab dip, fresh oysters, sandwiches and salads are also hits. Patrons are welcome to grab a quick bite before heading back out to the beach or sit a spell for a relaxed meal.

The upper deck provides a more traditional restaurant atmosphere, encouraging people to spend several hours enjoying meals and each other’s company. Albright puts it as fine-dining without the fine-dining expectations. “People will feel comfortable coming in shorts and a T-shirt but still get that quality that they want,” she says. Opening later than the lower deck, the upper part of the restaurant serves more elevated menu items, such as crab bisque, island swordfish and blackened duck, and martinis to wash it down. Rich blue tones and wood accents lend the decor a classic coastal vibe with a refined touch. Sunday brunch has become a favorite with customers wanting a slow weekend morning with family.

Whether you’re looking for a more formal meal or something quick by the water, Shipp’s welcomes you to bring the kids. “Our restaurant is very family friendly,” says Albright. “It’s a familyowned restaurant. I started working in our restaurants when I was 12 years old, so that’s something that’s really important to me, and I hope we portray it to our customers.” MB

[ ON THE MENU ]

Jumbo lump crab, lemon oil and lemon zest give this sushi roll a bright, fresh taste. Stuffed with tempura shrimp, avocado and cream cheese, this roll is topped with a drizzle of spicy mayo for a hint of heat.

Seared tuna is topped with grilled pineapple salsa, wasabi mayo, wasabi greens and butter for an elevated dish you won’t want to miss.

This roll features crunchy tempura shrimp, creamy avocado and cream cheese and a kick from wasabi mayo. Tuna, microgreens and a soy glaze top it off.

This bestselling appetizer is made for sharing. Rich, creamy and full of crabmeat, it is topped with pickled jalapenos and Parmesan and served with pita chips.

This citrus-based cocktail is the restaurant’s signature drink, served in a souvenir glass and ready to set the ideal vacation mood.

A weekend adventurer pushes himself to the limits while attempting to cross Mobile Bay and finds the good type of fear in the process.

text

Both arms ached, and my right lat muscle was seizing with cramps. I had to raise my right arm above my head to get it to relax. I was sitting on a paddleboard in the center of Mobile Bay, working to keep my fear from taking control, breathing deeply, trying to remain calm.

When I paddled again, the seizing muscle returned. It took 10 minutes of rest to calm it, during which the north wind pushed me too far south. To make up for lost ground, I headed hard northeast. I was now alternating paddling seated for 20 minutes, kneeling for 20 minutes and standing for 20 minutes. Each different position offered different muscle usage, giving different muscles a small break. I was tired. And I was more than a little worried.

Was it time to call for help?

Last July, I determined that I’d paddleboard across Mobile Bay — or try to, at least. The challenge would test me, and I could use a test like this. I shared my intentions with lots of people. I reasoned that with so many people aware of my goal, it would hold me accountable to achieving it. I hadn’t been on a paddleboard in 10 years or more. My balance, critical to paddleboarding, is average at best, and I didn’t even own a paddleboard or paddle. I began laying out a plan.

Using Google Earth and estimating how fast I could paddle, I figured I’d need to paddle with good strength for just shy of four hours. I was wrong. Way wrong.

I was inspired by the Molokai to Oahu paddleboard race I had seen on social media. It’s a 32-mile open-water challenge that happens every July between the Hawaiian island of Molokai and an Oahu beach. Videos of these athletes plowing over and through huge swells was awe inspiring. Certainly, if these people can paddle 32 miles over the deep, open Pacific Ocean (the Ka’iwi Channel is 2,300 feet deep), I can go 11 miles over the calm, shallow waters of Mobile Bay. Unlike the Molokai to Oahu competition, where the event date is fixed on the calendar, I could pick my crossing day when I found the weather I wanted, and I could train until I felt ready. Because of this flexibility, this would be a good challenge, I told myself, and it wouldn’t be too hard. It would force me through the fear of being alone on open water — there would be no paddle partner and no chase boat — and train me to do something unknown. This is the good type of fear.

Yet the ultimate question haunted me: Can I actually do this? Do I have what it takes? Do I have the mental and physical discipline to plan for the crossing, train consistently and appropriately, start paddling at Dog River and finish on the eastern shore of Mobile Bay at the Grand Hotel? It’s 10.8 miles as the crow flies. With adjustments and course corrections along the way, I expected it to be nearly a 12-mile paddle.

Jimbo Meador loaned me his Dragonfly paddleboard designed as a fishing board. It was wide and long with a shallow keel to allow it to float over very shallow water. It was stable, which I needed, but it was also heavy — at 65 pounds it is about three

times as heavy as newer board models. The shallow keel meant that when I paddled, it was easy to get off target, and I’d need to switch paddling sides frequently. Clint Jameson with Adventure Earth rented me an adjustable paddle and sized it to my height. Then it was time to train.

August 18, 2024

I shoved away from land at Memories Fish Camp near the headwaters of Fowl River around 8 a.m. This would become my training water. Fowl River would be calm. At no point was I too far from the water’s edge if something went wrong.

I paddled about an hour that day — about two miles of slow, very deliberate and wobbly paddling. When I passed the only other boat I saw, they called out “Good morning” and I nearly fell. I smiled instead of replying. I’d have to wait to learn to both talk and stand on a paddleboard at the same time — I wasn’t quite there yet.

August 30

Out of bed at 5:05 a.m. The board was strapped to my car and the paddle was inside. I was on the water at Fowl River shortly after 6 a.m. My goal was to reach three hours of paddling. I had achieved two hours the weekend before and felt good when I finished. Three hours should be reachable.

Twenty minutes into the paddle, a giant whoosh disrupted the water about a foot from my board. The board rocked, and I struggled to stay standing where whatever made the whoosh was now below me. The boil in the water was about four feet in diameter — whatever caused it was huge. The week before, I had asked local Fowl River expert Sam St. John if there were any alligators in the river. “Oh yes,” he

September 14

I left Memories Fish Camp at 8:20 a.m. I was feeling strong. Getting to my feet on the board was getting easier, and I’d only fallen twice in all my training — most recently when a boater slowed down next to me, swamping me with its wake.

At 90 minutes, I turned around on the eastern side of Bellingrath Gardens in a wide part of the river. There was now a slight headwind, and the tide was going out, running against me. This will be a good test, I told myself.

In the third hour, something happened. I grew suddenly weak and had to drop to my knees. With the headwind and the current against me, I was still far from my starting point. My vision began to blur and fade, and I was unable to see color. Everything went white except for a small hole in the center of my vision where I could make out broad shapes.

Could this be a stroke? Another one? I had no life jackets. I was afraid to grab for my phone for fear of fumbling and dropping it.

I paddled to land and sat until my vision slightly recovered, then pushed back into the water and, from my knees, slowly paddled another 40 minutes to the launch. The distance between the last Fowl River no-wake sign and the Memories Fish Camp launch usually takes 10 minutes to paddle. This time, it took 30. I asked a fisherman launching his boat for help loading the board since I was too weak to do it alone. I sat in my car another 30 minutes until my vision was good enough to drive, then headed straight to Greer’s in Bayley’s Corner and bought an armload of fruit and Gatorade.

A doctor told me it was likely a severe blood sugar deficiency, and I should paddle with apples and peanut butter next time — along with lots of water — to keep my blood sugar up. Noted.

TWENTY MINUTES INTO THE PADDLE, A GIANT WHOOSH DISRUPTED THE WATER ABOUT A FOOT FROM MY BOARD. THE BOARD ROCKED, AND I STRUGGLED TO STAY STANDING WHERE WHATEVER MADE THE WHOOSH WAS NOW BELOW ME. THE BOIL IN THE WATER WAS ABOUT FOUR FEET IN DIAMETER. WHATEVER CAUSED IT WAS HUGE.

nodded. “Plenty of them.” Was it an alligator that had caused the water to jump? A manatee? A gar? A bull shark? I paddled to the nearest bulkhead, dropped to my knees and looked back. The water was still churning.

Not knowing what to do, I looked at my phone and noticed the threat of weather to the south and saw an anvilshaped cloud forming. That was all the excuse I needed. I turned around and headed back to the launch, sprinting over the spot where the big creature had been. I was loading the paddleboard onto my car 20 minutes later in the rain. The three-hour goal would have to wait.

October 13

I paddled the length of Fowl River, from Memories Fish Camp to the Fowl River marina. I ate apple slices and peanut butter along the way and never felt weak. I was ready to make the crossing, I thought. I felt confident and strong in the water.

Then my work travel schedule took off. I was on airplanes and in hotel rooms for most of the fall. During the Christmas holidays, it was simply too cold to be on the water, and then spring vanished with Mardi Gras activities. The paddleboard beckoned from the garage. I wondered if I had what it took to resume this challenge, or would I find excuses not to try?

April 12, 2025

It had been six months since I was last on the paddleboard. I carried the board on my head from the Memories Fish Camp parking lot to the edge of Fowl River where, at the water’s edge, my flip-flop hit slippery mud. I didn’t fall straight down. In a quirk of physics, I gained altitude before beginning my fall. My lower back left a crater in the mud, and I struggled to get out from under the paddleboard. I launched wearing a blue t-shirt caked in Fowl River mud.

Three hours later, I asked a kayaker to help me carry my board to the car. He walked to the water’s edge, and just as he got to my board — in the very same spot — his feet shot out from under him. He ascended and crashed on his back in the very same crater my back had made earlier. It’s a tricky spot.

With a solid three-hour paddle completed, I was as ready as I’d ever be, though one more three-plus hour paddle would add to my confidence. It would never happen.

The spring of 2025 in south Alabama proved breezier than any I could recall. Looking for days to practice or days to cross the Bay, the wind was always a problem. I wanted a light wind from the west, enough to help move me over the water but not so strong it would create chop on the Bay. Later in the week of May 26, a series of storms blew through, and when the weather cleared, it left blue skies and a breeze from the north. Saturday would be the day. I was tired of putting it off. Though not a west wind, a north wind would help once I cleared Gaillard Island. This would have to be it.

curvature of the earth to overcome. It’s the reason I can see only the treetops on the other side — no roofs, no wharves, certainly not the Grand Hotel. I get to my feet and take my first big stroke. “This crossing may be a non-event. We’ll see,” I call to my wife over my shoulder. I point the paddleboard northeast to account for the wind and start.

I hadn’t realized how much the wind would push me. Though the tide was coming north, the wind was blowing me south, and the wind was winning. To move easterly across the Bay, I had to point the board well to the northeast — roughly at what I guessed was the Spanish Fort Hampton Inn just off I-10 — to keep moving east. It required 15 to 20 strong strokes on the right side of the board, then three light strokes on the left to go straight. Eventually, I passed the Dog River channel markers and then came even with the western edge of Gaillard Island.

May 31—The Crossing — 10:40 a.m.

My wife and I found a small beach at the end of Park Road just north of the Dog River bridge. We set up the paddleboard, and I shoved off to the east. The wind was blowing but should eventually die down. I decided to launch at the high point of the day’s wind when I’d have my strength. By the time I weakened, so would the wind, and I’d have to fight it less.

Ahead of me was nearly 11 miles of Mobile Bay to cross and the

My lower back was on fire. Paddling primarily on one side of the board was not something I had prepared for. Whenever I paddled on the left, I could feel my back ease, but paddling repeatedly on the right into the wind brought lower back pains I hadn’t experienced in my Fowl River practices.

11:30 a.m.

I still had not cleared Gaillard Island. The wind had not died down much. Now on the horizon was what appeared to be the top of a tall, rectangular building about where I guessed the Grand Hotel to be. I made this my new target but was still having to point the board northeast to account for the north wind. In an hour, I might be able to turn south a bit and let the wind offer a hand.

12:30 p.m.

I finally cleared Gaillard Island. The rectangular building was still visible and still my target. The wind was slacking but hadn’t stopped. My legs were feeling it. The waves were causing the board to wobble more than anything I had experienced on Fowl River, and the small muscular adjustments to stay standing were being absorbed in my thighs, which were now on fire. This was new pain. I estimated I was about halfway.

1:30 p.m.

I thought I could see where the land on the Eastern Shore formed a point to my south, which would be the Grand Hotel. On the eastern side of Mobile Bay, there were many fewer pilings or crab trap buoys for me to use to judge my speed. In the past hour, it didn’t feel like I’d made any headway. The wind had slowed a bit, but the current was still coming in. Could it be that the current was now winning and that, regardless of my paddling, I was floating north, not southeast toward my target?

I reminded myself not to let my brain get out of control. My guess was that the paddle would now take four hours. My left triceps and right shoulder were beginning to cramp. The nearest land was the Fairhope beach, however getting there would require me paddling directly perpendicular to the wind, and I no longer had that strength. I headed further south. Though a longer paddle, it would let the wind push me toward the hotel. “You’re OK,” I kept repeating to myself.

2:00 p.m.

I was slowly getting closer. I had to be. I thought I noticed the features of the hotel coming into view. Or maybe I was imagining progress. My arms hurt and I was questioning what I had started. Why even do this?

My memory of being helpless during a stroke from a blood clot in my head in March of 2023 wouldn’t go away. I fully recovered from it thanks to lots of luck and my doctors’ expertise. It was an awful event, and the memory of that helplessness has nagged at me. I wanted to feel like I was in control of my body again. And to regain that feeling, I settled on this challenge that would put me into unfamiliar territory — something that would generate the fear that makes you feel more alive, not the fear of being helpless to circumstances beyond your control.

“Why?” was the question most people asked when I told them what I was up to. And saying, “To feel more alive” is a corny answer. But it’s the truth. I ended up saying, “Just to see if I can do it” as the standard reply which generated lots of shaking heads. My wife sensed that I was committed and never tried to talk me out of it. My friends offered to escort me with their boats, and I turned them all down. I wanted to do it alone, I wanted to feel exhausted, I wanted a feeling of accomplishment and, along the way, I wanted to feel a bit of fear.

More of the Grand Hotel’s features were coming into view, but somehow it felt like I wasn’t moving. My wife told me she could see my movement on her phone app, that I was headed in the right direction. None of the key landmarks — the Grand Hotel in particular — appeared

to be getting any closer. My arms and shoulders were exhausted. I’d eaten all my apples and was nearly out of water. This whole thing was a bad idea.

3:20

My watch battery died. It last showed that I’d paddled for five hours, travelling 10.8 miles at an average of 2 miles per hour. My heart had been beating at 150 bpm the whole time. 2,800 calories burned, with still a ways to go.

I paddled the last stretch of water on my knees, counting out 100 paddles, then falling forward onto my hands to rest. Three hundred paddles later, I could hear my wife calling to me from the marina bulkhead. Her video shows weak paddles, no strength left. The paddleboard touched the sand at the small marina just north of the Grand Hotel. I sat on the board for 20 minutes while my arms and legs trembled. My wife brought me Gatorades and bananas. Gradually, I was able to stand. We lifted the board onto the car and strapped it down for the ride back to Mobile.

I frequently tell my children that they are capable of doing hard things. Usually, I say this sitting in my comfy morning chair drinking a coffee or, later in the day, having a glass of wine. What I’m saying versus what I’m doing stands in stark contrast with one another, and this dissonance has often made me wonder if I am still capable of doing hard things.

My stroke put me on the mat. It scared me. I was not in control. Having the will to live and survive is not a hard thing. It’s automatic; it’s built in. I needed to do something hard to remind me that I am, today, capable of doing hard things. And I did it. Despite the exhaustion I felt that afternoon and poor sleep that night due to twitching muscles and a fatigue that wouldn’t allow me to relax, I was tremendously proud of myself. And I still am.

The next day, my brother Dale met me at Jimbo Meador’s house to help me unload the board. I’d washed and waxed it, and Dale and I put it on its stand under the eave of Jimbo’s garage. Jimbo congratulated me. “That’s quite an accomplishment,” he said.

“The board is here if you ever want to use it again.” Nope. I’m done with that. Glad I did it, but never again. Paddling across the Bay scared me a bit. But it was just the amount of fear that I needed. MB

Cam Marston records weekly commentaries for Alabama Public Radio that broadcast Fridays during drive time. He has a podcast, runs a seminar company, and is a top-rated keynote speaker focusing on workplace and workforce trends.

text by AMELIA ROSE ZIMLICH • recipe by MOCHAMAD RAYZA • photos by ELIZABETH GELINEAU

A Daphne chef serves creative recipes for fresh-off-the-boat fish.

Mochamad Rayza is a go-to resource for all things fish. His customers are well aware, approaching the chef and owner of Rayza’s in Daphne for his expertise. “Customers will say, ‘I just caught a yellowfin tuna. Is that good for sushi?’” he says.

Fishing is second nature to many on the Bay, but preparing fish to eat fresh can feel somewhat intimidating. Not to Rayza. As it turns out, the process is straightforward. “For people who like eating tuna raw, they can do that easily at home,” he says.

“A good option is always a tuna poke. Just clean up the fish, descale it, gut it and everything, then dice it up.” Rayza enjoys experimenting with different flavor profiles to serve with his catch.

“You can always try out making your own sauce, like spicy mayo, sesame soy sauce or a wasabi dressing, to top it.”

With over 20 years of culinary experience in Indonesia, Dubai, Miami and, finally, Alabama, Rayza has never been one to shy away from fish. He was head chef and sushi roller at Chuck’s Fish in Tuscaloosa before bringing a location to Mobile. He started Rayza’s a few summers ago, a restaurant that he describes as being a call from God and a fusion of everywhere he’s worked. His menu utilizes fish in almost any capacity you can think of. While

some is brought in from Japan or Alaska, “We try to use as much of our local fish as we can, especially for the yellowfin tuna, which we get from the Gulf,” he says.

Dry aging is a signature fish preparation method that Rayza employs in his kitchen. “We dry age the fresh tuna that we have and then season it, put it in a pan, do a quick sear and use it to make a tuna bowl,” he says. Dry aging amplifies the umami flavor of the fresh fish. “When you slice dry-aged fish, it tastes more buttery,” he says. “It takes away the impurity of flavor and the moisture. This helps eliminate the overpowering fishiness, allowing the natural flavor of the meat to truly shine.”

Though the process may seem mystifying to those without vast culinary experience, Rayza says it can be replicated by home cooks who want to give it a shot. “You can turn your wine

cooler into a dry ager by installing a small fan for air circulation. Or you can buy a dry ager that’s made for residential use.” The keys to success? Keep a steady temperature between 33-37 degrees for fish and make sure you age your fish for the proper time. “We are blessed to have convenient access to the water and the Gulf,” he says. “You can definitely prepare fresh fish at home.” MB

TUNA TATAKI SERVES 2

5 ounces dry aged yellowfin tuna Salt, to taste

Black pepper, to taste

1/4 cup puffed rice

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon balsamic teriyaki sauce

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon creamy truffle sesame sauce

Maldon salt, for garnish Microgreens, for garnish

1. Season the tuna with salt and freshly cracked pepper. Press it gently into the rice puffs. In a pan over medium-high heat, add a touch of avocado oil and sear the tuna for a minute per side.

2. On a plate, spread a swipe of both sauces. Slice tuna thinly with a sharp knife and place over the sauce. Finish with a sprinkle of Maldon salt and a handful of microgreens.

MAKES 1 CUP

1 cup Kewpie sesame roasted dressing

2 tablespoons white truffle oil

1 tablespoon yuzu juice

1/4 teaspoon Xanthan gum

BALSAMIC TERIYAKI SAUCE MAKES 2 1/2 CUPS

1 cup plus 2 tablespoons balsamic vinegar

1 1/4 cup chicken stock

1/4 cup sugar

3 tablespoons plus 1 teaspoon soy sauce

3 tablespoons plus 1 teaspoon mirin

1. To make the above sauces, mix all ingredients together and store in the refrigerator until use.

Experience the joy of life on the water through the lenses of readers in our wet dog photo contest.

Having lived by the water her entire life, the “Bayside Lifestyle” is something special to Mallie. She traveled with me to St. Kitts for nearly three years while I completed veterinary school. She is one in a million, the best companion and most definitely a water dog. Mallie

Standing atop a massive rock by the Bay, GiGi embodies the power and presence that all chihuahuas possess. This image is extra special because GiGi passed away two years ago at the age of 10. We still feel her grandiose presence with us and this photo is a reminder of that.

BLACK LAB

Four-year-old Chief is the definition of a water dog as he jumps into the water with his gear in

Oscar

One person’s trash is Ben Gibson’s treasure — and the beginnings of new works of art.

text by CATHERINE DORROUGH photos by CHAD RILEY

It’s a cloudy Saturday morning at Fairhope’s Secret Beach. The air is clear and sweet from the previous night’s rain. A heavy fog bank roils along the tree line and blurs the western horizon, blending both the Bay and the sky into one infinite depth.

Ben Gibson and his two young sons are here to hunt for treasure. Gibson often comes down to this quiet sandy stretch most weekends to soak up the seclusion, but today is an especially good day because conditions are perfect for a treasure-hunting expedition.

Earlier in the week, a thunderous gullywasher swept across the Bay, dumping torrents of water that sluiced down the muddy folds of Fairhope’s shoreline, shifting and molding the layers of clay and soil. The Gibsons are experienced enough to know that this is the kind of storm that unearths old glass bottles and other artifacts from Fairhope’s past. Equipped with rain boots and a five-gallon bucket, Ben and his boys set off to see what they can find.

To arrive at the Secret Beach, they’ve come down the “Stairway to Heaven,” a 76-step wooden public access stairway hidden in the trees near an infrequently traveled road. There’s no public parking, no city signs to point the way, which means you’ll never find it if you don’t know where it is.

Ben only knows about it because, back in his early 20s, he used to live up on this part of the bluff, in a crummy cinderblock house with a great view.

Once they’ve made it down the rain-slick steps, traversed a short trail and emerged onto the beach, Ben and his sons – fifthgrader Rett and second-grader Davis – scan the sand for flotsam and jetsam that has washed ashore. They collect trash to throw away later and put anything that looks interesting into the bucket. Their finds are the usual beachcomber stuff: bits of sea glass, plastic knickknacks, driftwood. But these are just smaller treasures, curiosities to gather on their way to the main attraction. Their destination is halfway up the beach, invisible until you’re right up on it. There, behind a curtain of vegetation, an invitingly clear path of tumbledown rocks, silt and clay recedes into the bluff.

Less intrepid beachgoers might be inclined to leave this gully to the snakes and raccoons. But the Gibsons delve into the gloom without a moment’s hesitation, ready to clamber over logs and duck under branches. Not 30 feet from the start of the path, a jumble of rusted car frames lies within reach.

It’s not long before they find what they came for, half-hidden in the damp dirt: A glass medicine bottle. A little white porcelain jar. A whiskey bottle. Improbably, a new-looking beach ball, still inflated. Whenever they find an artifact, they check it for markings that could help to date it. In the two years they’ve been exploring this gully, they’ve found more than 200 bottles, including a couple that date back 100 years.

Ben reckons that this gully used to be the place to dump trash for the people who lived up on the bluff. “All the people who lived in this neighborhood were coming down here at some point and just throwing out trash,” he said. “Eventually it gets washed out. It’s still washing out, 100 years later, into the Bay.”

As it turns out, lots of early Fairhopers saw gullies as convenient places to chuck their garbage. Sometimes these dumps were informal, but in the early years of the 20th century, Big Mouth Gully on the northern outskirts of downtown was home to a citysanctioned dump. A gossipy article from the April 18, 1924, edition of the Fairhope Courier reads:

“One of our new citizens was mildly scolded by a ‘father of the town’ the other day, for dumping some trash into the gulley... The gentleman in question is as deeply interested in preserving the attractiveness of Fairhope as any one and explained that seeing other matter having been dumped there, he thought it might be a recognized dumping place, for the purpose of helping to fill up the gulley. On having it explained to him that there was only one authorized dumping place which was down Section street opposite the cemetery, he urged the Courier to call attention to this fact, so that others might be spared the mistake which he had made.”

Stack Gully near the Fairhope Pier has also claimed artifacts, including whole cars that still lie buried under the kudzu. A century ago, when Klumpp Motor Company stood on the gully’s edge, a few “early junkers” somehow ended up tumbling into the depths below, according to local historian Alan Samry in his book “Fairhope (Past and Present).”

The gully at the Secret Beach is not grand enough to have a name on the map, but it’s the most prolific source of artifacts that Ben has found. Within half an hour, the Gibsons have exhausted the area and emerged from the undergrowth. The sun has started to peep

out from behind the clouds. Nearby, a little ground spring bubbles up and cuts through the sand, emptying into the Bay. It’s the perfect spot to rinse off the bottles before hauling them back home. The next time it rains, there will be a new batch of bottles to harvest.

When Ben gets the bottles home to his back porch, he transforms them into art pieces that he calls “gatherings.” It’s a neat magic trick: Take a few bottles and arrange them with some driftwood. Add barnacles and shells, and presto, you have a sophisticated, sculptural bud vase, perfect for fresh camellias. Or maybe you have a suncatcher. Or a centerpiece. He doesn’t overthink it. With the right eye, anything can be made into a new creation. He gives them to friends and occasionally sells them under the name Gibson Gully Glass.

After the treasure hunt is over, the boys run up the beach to a tire swing they’ve hung from a tree. (The tire, of course, is another beach find.) The children get the swing whooshing high, and then one of them points at the water and yells, “Shark!” Out among the waves, a pod of dolphins swims up the Bay.

Near the swing, they’ve erected a monument of driftwood and tied-up glass bottles, a glittering mass of green and clear and brown, and topped it with an American flag. A patchwork of shells, old rope, broken china – even a cooked crawfish – fill in the spaces between the bottles. Off to one side stands the skeleton of a small Christmas tree, every branch decorated with a found ornament: a yellow Easter egg; a purple pair of heart-shaped sunglasses; an ancient pacifier.

The display is always changing. Some days, the Gibsons will arrive to find that some other beachgoer has contributed to it. “If you look at the tree long enough, you’ll say, ‘I don’t remember adding that to it,’” said Ben. Some people make more substantive contributions, too. One person has built an artistic small bench nearby and painted “Fetchin’ Sticks” on it in hot pink. An assortment of stout branches lies across the bench seat, ready for the taking.

But things also disappear. Sometimes, pieces of the beachfront art installation disintegrate and wash away. People occasionally cut the bottles down, take things, break them. It’s all just part of the coming and going, the slow migration of all these manmade objects. They are discovered, discarded, discovered again. “We know it’s not always going to be here,” said Ben. Everything is temporary. MB

A Fairhope coastal cottage on the water is the perfect place to leave a legacy.

text by AMELIA ROSE ZIMLICH

ROWE

The first sound that greets you at Oyster Glass is waves lapping gently on the shore. The second is Venus the dog’s barks of excitement ringing through the house. “We originally thought she was a basenji, a barkless dog,” explains Laura Glassburn. “You see how that went?” she says with a good-natured eye roll and the tilt of a head toward the dog, now curled up on the couch. “I used to have two little terriers, and I know she learned how to bark from them.”

Laura and Venus, along with Laura’s husband Doug, have barely lived in the house by the water for a year, but it already has a distinct, comforting sense of home, as though they’ve been here much longer. The Southern coastal cottage earned the name Oyster Glass as an ode to the Glassburns’ name. When asked about their backgrounds, Laura has a short explanation. “Native,” she says, pointing to herself. She then

points to Doug. “Yankee.” The pair bursts into laughter. Laura has deep Alabama roots, growing up in Monroeville for just a few years before her family moved to Mobile, where she attended St. Paul’s Episcopal School. “I feel like we’ve just always been here,” she says. “My mom was born in Mobile, right behind the old Weinackers. You know all those places like Macy Place and Ann Court? My mom is Ann. My grandfather was a builder in Mobile. He built all of those and named one after every kid.” Laura herself has lived in Fairhope around 40 years. Doug’s calling to Alabama came in the form of work, moving to Daphne from Indiana in 2009 for a job at Austal. The two had a chance meeting one Memorial Day weekend about seven years ago. Laura was staying with her kids in a condo. “It was foggy, rainy and gross, and we had no service. They’re like ‘Mom, we’re going to Flora-Bama to watch the Auburn game,’” she recalls. “I told them, ‘I am not going to Flora-Bama. I’ll go around the corner to Tacky Jacks, get a fish taco, watch the game and be done.’ And there he was. Three bushwackers later and I got a ring.”

Laura had already put an offer on a house in downtown Fairhope when she met Doug, so they lived there for a

few years. During that time, the Glassburns began looking to buy a fish camp, but the price and proximity of the camps on the market made the decision a tough sell. “Doug’s the voice of reason. And I’m the voice of insanity,” says Laura. “He said to me, ‘Let me get this straight. You want to buy something for that amount of money and keep the house in town, so we have two houses about 15 minutes apart? That’s a hard no for me.” The Glassburns kept an eye out until their search led them to County Road 1 in Fairhope. “We were down here on a Sunday and saw this lot. So, we called our realtor friend Rance Reehl, who was in Arkansas at the time,” says Laura. “He said, ‘It’s not on the market yet, but I’ll meet you there at 9 o’clock in the morning.’” The next morning, the couple and Reehl stopped by the lot to look, a task that proved to be more difficult than anticipated. Because of Hurricanes Zeta and Sally, there were trees down across the lot, blocking a clear path forward. “We had to go around to our nowneighbor’s house to see the entire plot of land,” says Laura. “And it had a beach. We loved it because it had a beach, not a bulkhead. Rance said, ‘If y’all don’t buy it, I will.’” They made an offer that day and 24 hours later, it was theirs.

While Laura provided input on her house in downtown Fairhope, this purchase marked both her and Doug’s first time building from the ground up. “We wanted to put in a pier, but we ran into every kind of permitting issue,” says Laura. “And once we finally got everything going, they said, ‘Wait. Because this has never been developed before, we have to have a cultural survey, because the area now covered in water used to be an Indian burial ground.’ We constantly see oyster shells and we don’t

know where they come from.” She pauses. “I mean, they could be the guy on the other end of the pier throwing them out,” she says with a laugh. “But we like to think of them as coming from the Indians, our ancestors. We always jokingly tease the kids about Chief Speckled Trout or some other figure. But, needless to say, that’s sacred ground. They’ve always said it’s the Bay of the Holy Spirit, and we believe it. So, we moved our pier over, which we feel good about. We try to be good stewards of the Bay.”

When it came time to start planning the house, the Glassburns dove right in. “We came up with the initial layout and started working from there,” says Doug. “We met with Cameron Reehl from Reehlco Custom Homes, then he made some changes that would make things easier, cheaper and better.” Their goal was to build a house that was functional and beautiful, with no wasted space. “We wanted to focus on the sustainability of us being here,” says Laura. “We’d like to be here until we’re not, so we tried to build it with family, retirement and entertaining in mind. We tried to incorporate all of that into the design, and I think we did a good job.” The Glassburns worked with Suzie Winston from the start to oversee interiors, look at the plans and give input. Winston designed the entire kitchen, pantry area and bathrooms, adding functionality to every space. “She helped us with cost cutting without design cutting,” says Laura. The living room has ample seating, as does the outdoor screened-in porch, allowing for family, friends and neighbors to gather without overcrowding. The banquette in the dining room can seat up to 12 people. “I just remember growing up and my grandfather had a huge one. All the kids would pile in, and we’d play games there,” says Laura.

Out of all the rooms in the house, the kitchen is Laura’s happy place. It doesn’t come as a surprise given her family’s background. “I love to cook. My mother had a restaurant in Fairhope and now we have lots of her stuff in here,” she says. The restaurant, Aubergine, was a staple in Fairhope in the ‘90s. Its old location is now home to Aubergine French Antiques, where Laura has sourced some of the furniture for Oyster Glass. An oyster painting hanging in the center of the bar area was created by her grandmother, with her oyster plates framing the bar. “The inspiration for everything in this entire house is from that painting,” says Laura. The kitchen’s focal point — a copper hood — was something Laura just knew she couldn’t pass up. “We found an artisan on HGTV,” she says. “Our next-door neighbor moved to Laurel when we were in Fairhope. We were watching as they designed her home in Laurel. And she had this beautiful copper hood. I was like, ‘I’ve got to have that!’ Doug said, ‘You can’t have it,’ and I said, ‘I’ve got to have it!’” Laura called Erin Napier’s resource group, who gave her the name of the artisan in Laurel. “He’s a fireman and a metal worker,” says Laura. “He made it for us and would send us different patinas. I would send those to Suzie, and she goes, ‘We need more,’ so he’d do more and voila!”

Perfectly planned for entertaining and with enough space for all, Oyster Glass is always open for neighbors to stop in or drop by. “Our neighbors are wonderful,” says Laura. “We have a mahjong group here on Wednesday nights. We do small group here

whenever we can. And we’ll get texts that’ll say, ‘Wharf party at 6 p.m.’ or ‘Pick us up over here, we’re going to Jesse’s.’ There’s something always going on with our fun group.” There have already been a plethora of wonderful memories made, despite the short time the Glassburns have lived in the house. “We had a jubilee here pretty soon after we moved in,” says Laura. “The neighbors yelled, ‘Jubilee!’ and we’re like, ‘What? We just got here!’” For Laura, it was exciting. For Doug, it was baptism by fire. “We jump up and he goes, ‘What do I wear?’ and I go, ‘It doesn’t matter!’” she says. “All the neighbors are out in our front yard because we have the beach, so everybody’s got their gigs. I gave Doug one and he goes out there. He’s stabbing these things over and over and one of the guys was so nice. He says, ‘Hey man, it would be easier if you take the tip off the gig.’” The couple breaks into a peal of laughter. “And then Doug reaches under one he gigged, and he was like, ‘I got an albino.’ Turns out it was the underside. Welcome to Alabama!”

Thanks to jubilees and generous neighbors with seafood to spare, the Glassburns have ample opportunity to make their favorite dishes for get-togethers. “I’m trying to get the daughters to make them all again,” she says, poring over printed out pages of red fish on the half shell and fried corn. “Some of these weren’t necessarily recipes; they were just in my head.” She takes out a page. “This is crabmeat Aubergine. Mother’s restaurant in Fairhope was Aubergine, it was her recipe, and we served it at the restaurant.” She notes that, despite the name, it does not contain eggplant. Grilled crabs are another one of her favorites. “They do them like this in Louisiana,” she says. “We boil crabs all the time over here and everybody I ask says, ‘No, we haven’t ever grilled crabs here.’ But they’re really good.”

With most of Doug’s family still up north and Laura’s children scattered around, the house has become an abode for extended stays. “For the Fourth of July this year, we want to get everybody — grandkids, children, family — over here,” says Laura. “The neighbors get together and they’ll have all their families over. We’ve been challenged to a Fourth of July competition with our neighbors. There’s cornhole and I don’t know all the other things that we’re supposed to be doing, but it’ll be fun.” A bedroom with a triple bunk bed and another bed besides is tailormade for grandchildren. The coastal Alabama theme is evident, with the blue bunk frame and sailboat decor. Wool swimsuits from the 1930s hang over one of the beds. The guest rooms should be filled come this fall. “One of the youngest in the family is engaged and they’ve been saving up for this wedding,” says Laura. “They were saying it would be 2027 or 2028 before they could get married, so we talked to them and said, ‘Have it here.’ And they are. In October, we’ll have everybody back, so we’re now the family venue. And it’s perfect.”

For the most part, the Glassburns keep it lowkey. “Entertaining with the big dining room and that kind of hosting, we don’t do it very much anymore,” says Laura. “We’ve moved from that to being more casual. Now it’s porches and piers.” There’s nothing that brings more joy to the Glassburns than watching their loved ones enjoy the beach, have conversations on the porch or sit down to a family meal together. “It doesn’t mean anything to us, this house, if we can’t share it and make memories,” says Laura. “We don’t need anything else. We just want to share it with family and friends. We want to leave a legacy here and it’s meant so much to have this dream come true.” MB

SERVES 12

8-12 ears of corn

1 1/2 pounds Conecuh bacon, chopped

1/2 cup red bell pepper

1 stick butter

Salt and pepper, to taste 1/4 cup milk, if needed

1. With a small paring knife, cut corn kernels off of the cob. Using the back of the knife, run blade down cob to get all the “corn milk.”

2. In a large cast iron skillet, saute bacon until crispy. Add bell pepper and stir until tender. Add corn, butter, salt and pepper. Cook for 10 minutes or until corn is tender and butter is melted. Add milk if corn mixture becomes dry.

SERVES 4-6

8-10 cleaned, uncooked crabs

Marinade

1/2 cup zesty Italian dressing

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1/2 teaspoon smoked paprika

1 tablespoon liquid crab boil

Baste

1 stick butter

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

1 lemon, juiced

1 teaspoon minced garlic

Dash liquid crab boil

1/2 cup finely grated Parmesan cheese

1. Crack the claws for ease of eating. Mix together all marinade ingredients. Marinate crabs for 15 minutes in a shallow dish. Set aside.

2. For baste, melt butter in saucepan then add parsley, lemon juice, garlic and crab boil.

3. Heat grill. Add crabs and cook, basting, 5-7 minutes on one side ,then turn and continue to baste. Once the crabs are fully cooked, sprinkle with Parmesan. Remove from grill and serve.

SERVES 4-6

3 tablespoons chopped shallots

3 tablespoons chopped red bell pepper

2 tablespoons chopped celery

4 tablespoons butter

1 cup heavy cream

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1 teaspoon Cajun seasoning

Dash cayenne pepper

1 pound fresh lump or jumbo lump crabmeat, drained

3 tablespoons finely grated Parmesan cheese

3 tablespoons Panko

1 tablespoon finely chopped parsley

1. Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. In a large skillet over low heat, saute shallots, bell pepper and celery in butter until tender. Add cream, lemon juice, Cajun seasoning and cayenne pepper. Fold in crabmeat, mixing well.

2. Spoon mixture into greased individual baking shells or ramekins and set aside. Mix Parmesan, panko and parsley. Sprinkle over crabmeat.

3. Bake uncovered for 20-25 minutes until heated.

MAKES 12

3/4 cup Duke’s mayonnaise

1 tablespoon Cajun seasoning

1 tablespoon lemon juice

12 slices white bread

3 fresh tomatoes

Salt and pepper, to taste

3 tablespoons cooked bacon pieces

1 tablespoon chopped fresh basil

1. Mix mayo, seasoning and lemon juice together. Cut bread with large round cookie cutter. Slice tomatoes and dry out on paper towels.

2. To assemble, spread mayo mixture on bread. Add tomato, salt and pepper. Sprinkle with bacon pieces and basil. PECAN MERINGUE PIE

SERVES 8

23 butter crackers

3 egg whites

1 cup sugar

1 cup chopped pecans

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 pint whipping cream

1/2 cup confectioners’ sugar

1/2 teaspoon vanilla

Berries or peaches for serving

1. Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Crush crackers in a plastic bag until about 1/4-inch in size.

2. In a mixer, beat egg whites until stiff peaks. Fold in sugar. Do not overmix. Fold in crackers, pecans and vanilla.

3. Pour into greased pie pan. Bake for 15-18 minutes until light brown on the edges. Cool.

4. In a mixer, beat whipping cream until hard peaks. Add confectioners’ sugar and vanilla.

5. Top your pie with whipping cream and add fresh berries or fresh peaches.

SERVES 7

7 large Redfish fillets with skin and scales still on

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

1/2 stick butter

2-3 tablespoons Cajun seasoning

1 lemon, juiced

Dash Worcestershire sauce

1. Coat fish with vegetable oil. Set aside. In a small saucepan, melt butter with all seasonings.

2. Place fish on preheated grill with scales down. Baste fish with butter mixture on an uncovered grill. Let the fish cook until it begins to flake. Do not to over-cook.

3. Gently remove from grill onto platter and finish basting before serving.

From the massive Gulf to tiny butterflies, tasty oysters and humble creeks, the Alabama Gulf Coast is our heritage, playground and, for many, a livelihood. Keeping such waterways clean and viable is the responsibility of us all.

Here are eight examples of those who do it right, our 2025 Watershed honorees. Their interests vary from classrooms in waist deep saltwater to respectful awe of an industrial strength river. But their goal is the same: aquatic excellence.

Michaela Shirley

In northern Mobile County, on the banks of the Tombigbee River, Outokumpu Americas (OTK) produces steel for worldwide customers. The river makes it happen. Michaela Shirley keeps the river clean.

“Actually, protecting the Tombigbee is a team effort,” says Shirley, OTK’s senior environmental sustainability specialist. “My responsibility is to meet environmental compliance, but every employee shares that responsibility.”

Shirley and team strive for more than meeting EPA standards. Their goal is to exceed expectations. “We are not satisfied to make the bare minimum,” she notes. “We strive to be the best.” The best includes good water. “We depend on the Tombigbee to make our products,” Shirley adds. “We must be guardians of the river. We want to work well with the environment and the community. We want to meet the regulations and do better.”

Her team constantly monitors ways to decrease river emissions. Recent projects have reduced OTK’s nitrate discharges by 40%. In one area of the mill, water usage has decreased by five million gallons a year. But the challenges continue. “There are so many regulations – federal, state and local – to keep up with. The challenges and changes occur almost daily but I can make an impact,” she notes, about keeping the steel mill running and the Tombigbee clean.

“It is an important job but also very satisfying. It is a job where you go home at the end of the day with a good feeling

of what you have accomplished.” As for working in a major manufacturing site, she adds “I have been here for 13 years. It still amazes me to see how steel is made.” Just add water –Tombigbee water.

A retired teacher in Mobile County and Baldwin County schools, Katie Owens has taught thousands of children about the importance of our Bay and wetlands. She did so in part as the voice of a frog.

Ribbit’s Big Splash presents interactive, decision-making activities for computers, home and school, and was created by Katie’s father with her assistance. “Dad encouraged me to educate and show children the significance of conservation, the environment and the critters in a puddle of water just outside your door,” recalls Owens. “There was very little local information available for elementary age children on these topics at the time (the 1990s). I was still in high

school when I became the voice of Ribbit.”

The program was produced on CD-ROMs. “CDs were big back in the ‘90s,” Owens recalls. Ribbit’s Big Splash was released in 2000. By 2003, over 38,000 Alabama students had used the program.

From Ribbit’s Big Splash, the Coastal Kids Quiz (CKQ) was created. It was coordinated by Owens for elementary school fifth graders. “I ran the CKQ for almost 10 years,” she recalls. “Originally, Coastal Kids Quiz was conducted much like a Scholars Bowl. Each school had fifth grade teams competing.”

The CKQ was reengineered by the Alabama Coastal Foundation (ACF). Owens is on the ACF Board. “Kids see it as a game but they are learning from it,” says the retired teacher, referencing CKQ.

She adds, “Seeing ‘graduates’ of Ribbit’s Big Splash and the CKQ is a thrill. Some are now adults, environmentalists at heart, and doing good things,” she says. “I also love seeing children interacting in these programs, getting the first little pieces about our ecosystem. They may one day find opportunities to help solve problems we do not know about yet.”

Future scientists may one day emerge from children inspired by a computer program, enthused by a Coastal Kids Quiz competition, or guided by the wisdom of a frog named Ribbit

One could swim among oyster larvae and not notice as they are not much bigger than a speck. Doug Ankersen, owner and operator of Isle Dauphine Oyster Company, raises such oysters and, as of this writing, has a lot of those “specks in stock” –about 12 to 15 million.

He and wife Mary raise oysters from seed to restaurant ready. He takes oystering to a higher level, literally. His marvel mollusks are raised off-bottom, that is, in floating cages above the Gulf floor. The advantages are many.

“Raised off-bottom, oysters grow faster and cleaner,” he says. “In addition, the oysters are more uniform in size and shape

“OYSTERS ARE MORE UNIFORM IN SIZE AND SHAPE AND THEIR FOOD, SUCH AS ALGAE, IS MORE PREVALENT NEAR THE WATER’S SURFACE THAN UNDERNEATH ON THE OCEAN FLOOR.”

– DOUG ANKERSEN

and their food, such as algae, is more prevalent near the water’s surface than underneath on the ocean floor.

Ankersen has been in the business since 2014. He started out as a commercial oyster seed nursery operation. He learned about the floating cages and innovative aquaculture techniques of oyster production, from a class taught at Auburn University.

Isle Dauphine’s oysters obtain food directly from the Dauphin Island seawater they are submerged in. There are no supplemental additives. The oysters grow and are transferred from hatchery to nursery, to farm and then sold to restaurants, farms and other oyster businesses. His customer base includes Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas and Florida.

Off-bottom oystering also helps the environment and its marine life. Part of Ankersen’s shellfish are recyclable as he keeps some of the oysters to provide more seed which will start the cycle over again.

“STUDYING THE MONARCH’S POPULATION AND BEHAVIOR CAN INDICATE HOW WELL WE ARE CARING FOR OUR NATIVE ECOSYSTEM...”

‑ CARMEN FLAMMINI

Carmen Flammini

In South Alabama, monarch butterflies get by with a little help from their friends. One such butterfly buddy is Carmen Flammini, Alabama Cooperative Extension System agent, Daphne resident and protector of the monarchy – the one with wings.

She has concerns. “Monarch butterflies are like the canary in the coal mine,” she says, referencing the days when miners sent birds into a dark mine before humans entered. If the canary lived, everything was fine. If the bird died, that was not good.

“Studying the monarch’s population and behavior can indicate how well we are caring for our native ecosystem and whether we are providing adequate food supplies for the insects that depend on it,” she says. “It’s important to maintain our monarch butterfly population. Declines can signal broader threats to pollinators and ecosystem health.”

This cute little bug migrates from Canada to Mexico and back, flying up to 3,000 miles round trip. It can fly over 100 miles in a day.

Flammini’s current project is focused on studying Alabama native milkweed plants, a species that monarch butterflies depend on exclusively to lay their eggs, nourish the caterpillar stage and provide nectar for the adult butterfly. She encourages

us to plant more milkweed, but the right kind: the native species are appropriate for our area.

The milkweed project is in conjunction with an Auburn University entomologist, the AU Horticulture and Ornamental Station in Mobile, the Baldwin County Master Gardeners and 10 other organizations in Baldwin County,

“Monarch butterflies are dwindling in number,” she says, “often because their food is dwindling too.” Without the correct nourishment, the butterflies can’t make the trip.

She adds that Alabama Native Milkweed plants also play an important role providing nectar to other pollinators.

Flammini also teaches master gardener classes and is an expert on home grounds, gardens and pests. She has designed STEM garden programs for schools and other local projects.

Flammini’s endeavors benefit home gardeners, the environment, and tiny winged creatures with a flight to catch.

As a boy, Tom Damson was raised on Dog River. He nostalgically recalls the good ole days when the river provided an abundance of fishing, swimming, and boating, in a watery playground. Life on the water was good back then and Tom strives to keep it that way now.

He is an active member of Partners for Environmental Progress (PEP) and was its board chairman for two years. “We advocate for the environment and best practices in business and manufacturing,” Damson says, about the group with a membership from all points of life. “We have business people and ardent environmentalists in our group. We know that if we communicate, things will work out.”

One of Damson’s and PEP’s current endeavors for a common good is The Eagle Reef Partnership, ‘mini reefs’ for oysters and other creatures. It began as an Eagle Scout service project, hence the name, Eagle Reef. “It is a floating reef in a large box structure, installed under wharfs and other areas,” he adds. “It attracts oysters, barnacles, shellfish. Most importantly, it provides a safe habitat for such marine creatures which have seen population decreases over the years due to less sea grass and habitats.”

He adds, “working with our partners, including the University of South Alabama Stokes School of Marine and Environmental Sciences, PEP Project hopes to deploy a thousand such reefs by the end of 2025. Over 200 are currently installed.”

In addition, Damson is a skilled fundraiser for environmental causes with proceeds going to PEP. He is also an adamant believer that, regardless of one’s statue in life, common ground can be reached. For Damson, that common ground is clean water with vibrant life.

Tom Hutchings

Living shorelines are a dream for some, desired by many and doable for Thomas Hutchings. A native Mobilian, he is president, owner and manager of EcoSolutions Inc. and its sister company, B&B Dredging. Hutchings guards, repairs and restores the life in living shorelines.

He has served in various capacities for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Osprey Construction, Eastern Shore Marine, Southern Yacht Charters, Alabama Coastal Foundation, and Hutchings and Associates.

EcoSolutions opened in 1995. “We recognized a niche not being filled,” Hutchings recalls about the start-up years. It is a niche no more.

He notes, “EcoSolutions designs and permits the project and the sister company, B&B Dredging, builds it.” Don’t try this at home.

“People don’t realize the detail the federal, state and local government puts on you,” Hutchings says, referencing beachfront property owners and those who want to be. “Handling government regulations, environmental laws and other mandates is not something you should do alone.”

He continues, “We work with the customer for the best solution to protect your shoreline while preserving the ecological integrity of the Bay.” He promotes shoreline revitalizations and restorations through the use of natural alternatives such as plants, sand and rocks. “We want to mimic nature as close as

“SHORELINE CREATURES ARE PART OF THE FOOD CHAIN. IF WE LOSE THAT, WE BREAK THE CHAIN AND THEN WE START THE DOWNWARD SPIRAL.”

– TOM HUTCHINGS

we can,” Hutchings adds. “Shoreline creatures are part of the food chain. If we lose that, we break the chain and then we start the downward spiral.”

But it does not have to be like that. “Do not procrastinate,” Hutchings warns about erosion and other factors property owners may face. “Once the shoreline is gone, it is difficult to get it back.”

On a positive note, he proclaims that humans and shorelines can co-exist not just because we need to but because we want to.

Fairhope’s Pelican’s Nest Science Lab’s website quotes Confucius: “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.” The Chinese philosopher no doubt referenced Mobile Bay.

Okay, he never visited Mobile Bay, but his words describe the Eastern Shore’s body of water perfectly. Mobile Bay is a hands-on teacher.

Pelican’s Nest Science Lab makes that teaching happen. Ka-

“FOR MANY OF THESE STUDENTS, EVEN KIDS GROWING UP ON THE EASTERN SHORE, IT IS THE FIRST TIME FOR GETTING THEIR TOES WET IN THE BAY.”

‑ KACIE HARDMAN

cie Hardman, a teacher in Fairhope West Elementary School, is the Pelican’s Nest Science Lab’s director.

“She explains the rewards of teaching in the waves often waist deep by saying, “When you see the spark in a child’s eyes, while holding a crab about the size of their pinky nail, or viewing plankton under a microscope, and for the first time, understanding what an estuary is, that is just life changing for me.”

A signature program of the Fairhope Educational Enrichment Foundation and the Baldwin County School System, Pelican’s Nest offers K-6th an outdoor classroom onshore and off. In 2025, the nest will be expanded for students K-12 with curriculums for each grade level.

“For many of these students, even kids growing up on the Eastern Shore, it is the first time for getting their toes wet in the bay,” Hardman says. “We present opportunities to touch a fish or toss a cast net for the first time.”

She notes that inquisitive youngsters — especially the elementary grades — have questions. “Some want to know if we will catch whales, great white sharks, or an octopus,” she recalls. “The answer is no.”

But the director adds, “however, whatever they pull up in their nets, even if it is seagrass, excites them. They dig into the seagrass and discover tiny minnows and crabs hiding in it. This appreciation for our waters cannot be taught in a formal classroom or in books. It has to be experienced.”

In a 2018 interview with Mobile Bay Magazine, Avery Bates explained his profession. “Folks should realize when you see our shrimp boats or oyster skiffs, it is not a fleet,” said the commercial fisherman, about the craft passed down to him through family generations. “Each boat is usually a single local family business, owned by a local person, making a living for his family.”

In 2025, Bates is retired. But his advocacy for commercial fishing is unyielding.

“Everything we buy and have, our land, houses, trucks, cars, comes from our labor” he says, about the men and women who cast nets professionally.

Bates has served as vice president of the Organized Seafood Association of Alabama. “We fought many battles and we still do,” he notes about the group. “Many of us had to shut down

“EACH BOAT IS USUALLY A SINGLE LOCAL FAMILY BUSINESS, OWNED BY A LOCAL PERSON, MAKING A LIVING FOR HIS FAMILY.”

‑AVERY BATES because of government regulations.”

He is concerned about the demise of local fish, especially oysters, due to mud and silt unloading. “We witnessed massive amounts of mud dumping in upper Mobile Bay,” he recalls. “You can’t put dirt on top of oysters,” he states. “It suffocates oysters and kills them.”

He notes that mud was dumped on the oyster reefs, destroying their habitat.

Like many in Bayou La Batre, Bates learned his vocation as a boy and stayed with it until retirement. Speaking about his trade he testifies, “This life is not an easy life. Commercial fishing is not an easy job. To do it you must love it.”

Avery Bates loves it. MB