‘Ntwana ya ko Kasi’

Experiencing space from the residents perespective

Experiencing space from the residents perespective

(1) Cover page

(4) Iminciza yeOvercrowding

- ‘Impilo ya ko kasi’

- ‘Isimo sasekhaya’

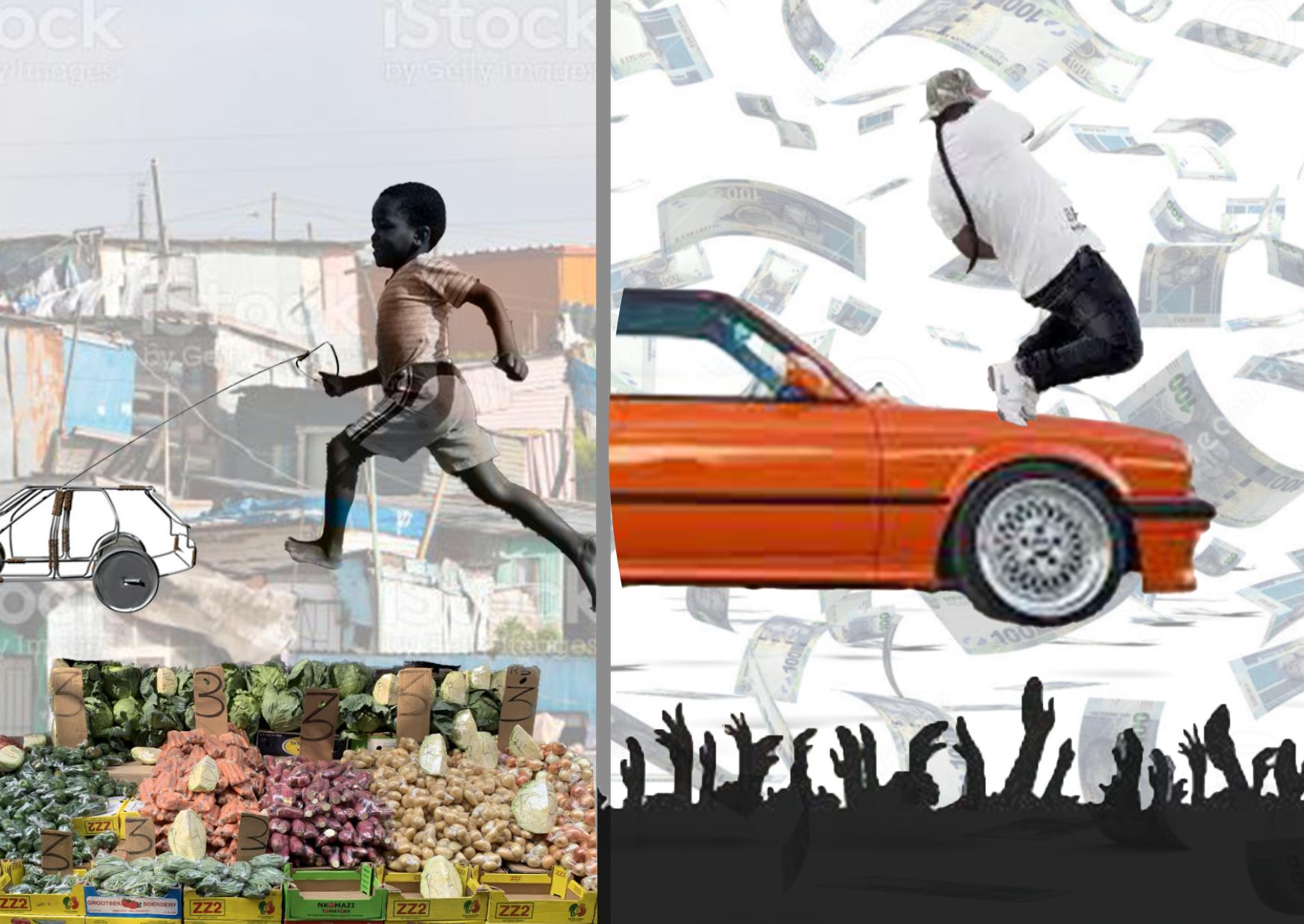

- ‘Creative entrepreneurship’

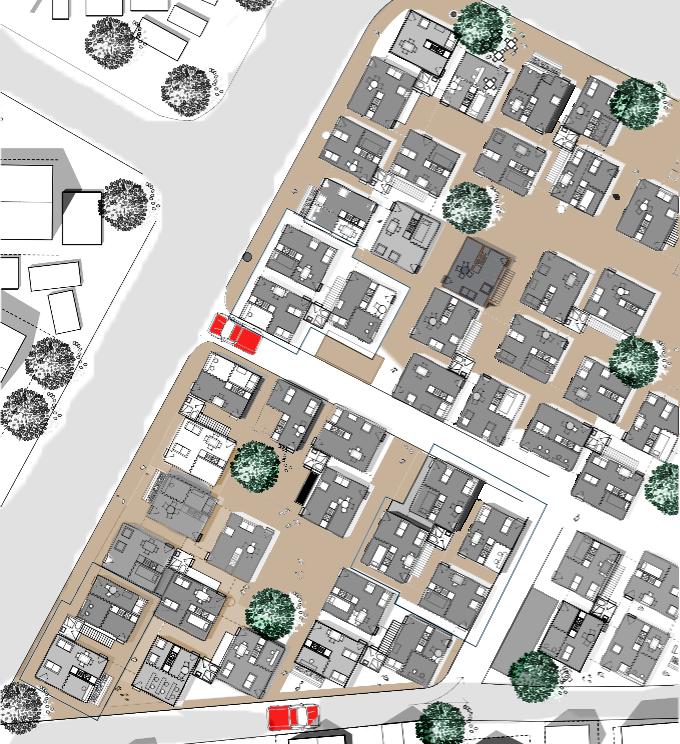

(18) Incrementalism in the Gusheshe neighbourhood

- Intensity and differentiation

(22) Breaking new ground

- Urban Agriculture

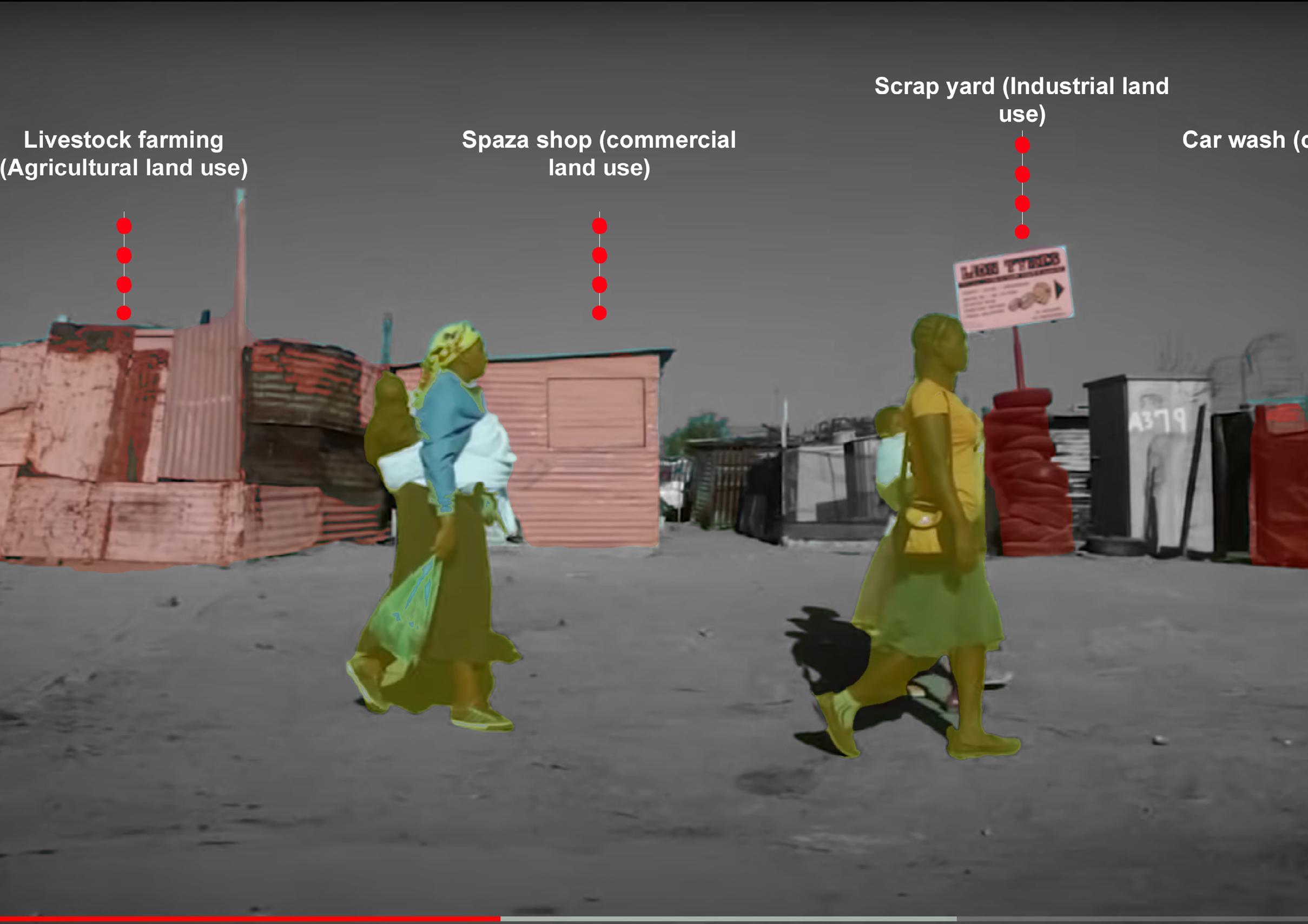

(12) Siyazenzela: Appropriation of space

- Izenzo zabantu

- Local appropriation

(28) References

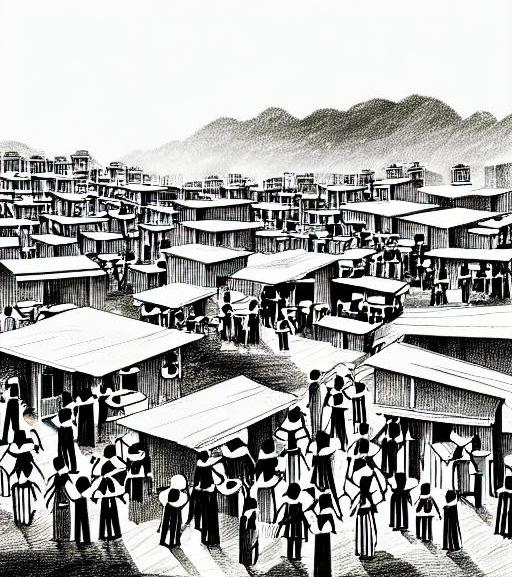

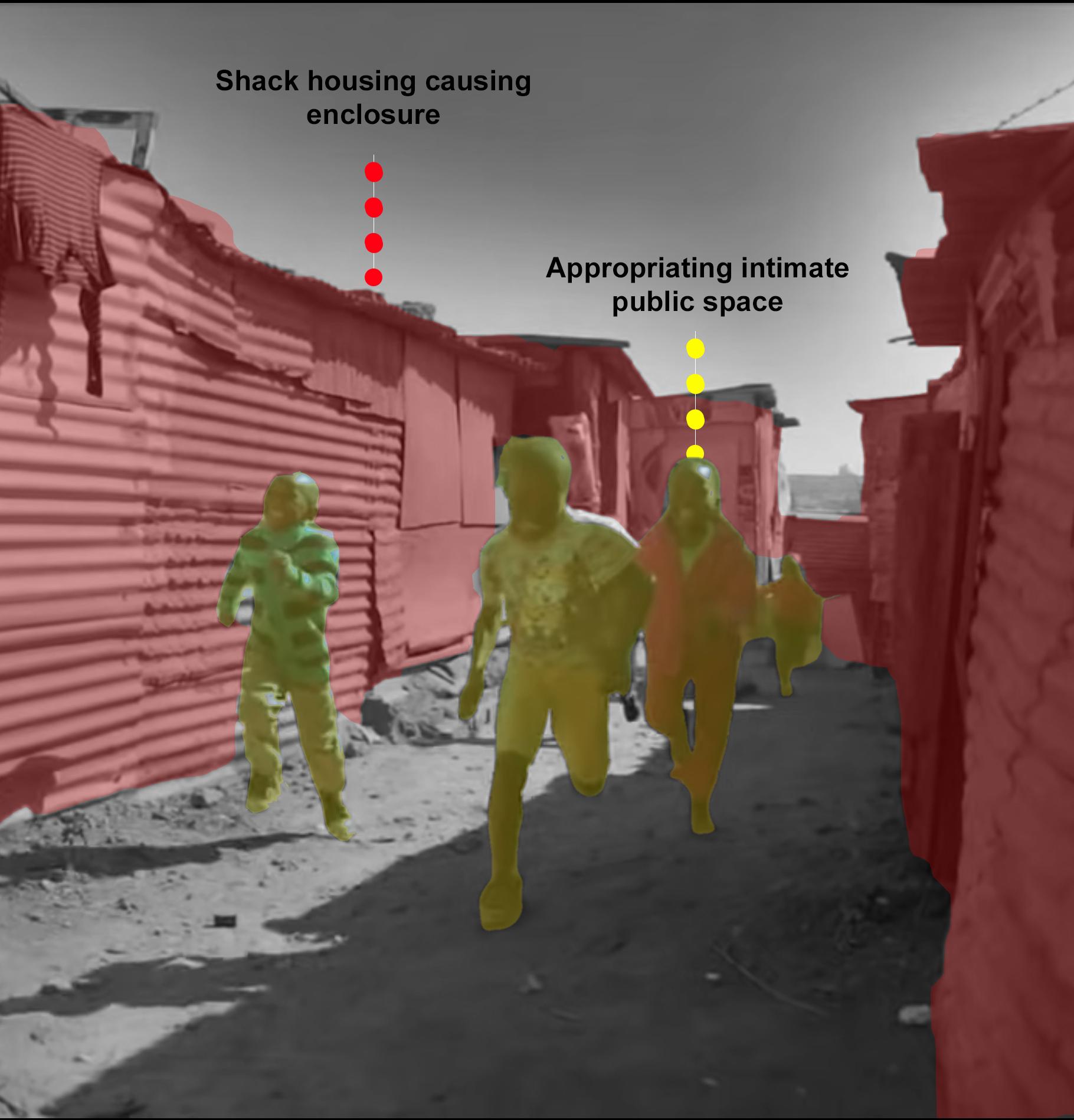

When people live together in close proximity to each other are obliged to have more intensive contact with others and their spatial environment (streets, squares, corridor etc.) is the setting for this.

With this chapter, the close conditions have given birth to a unique set of experiences in the ‘natural city’ (Alexander, 1972) of Diepsloot.

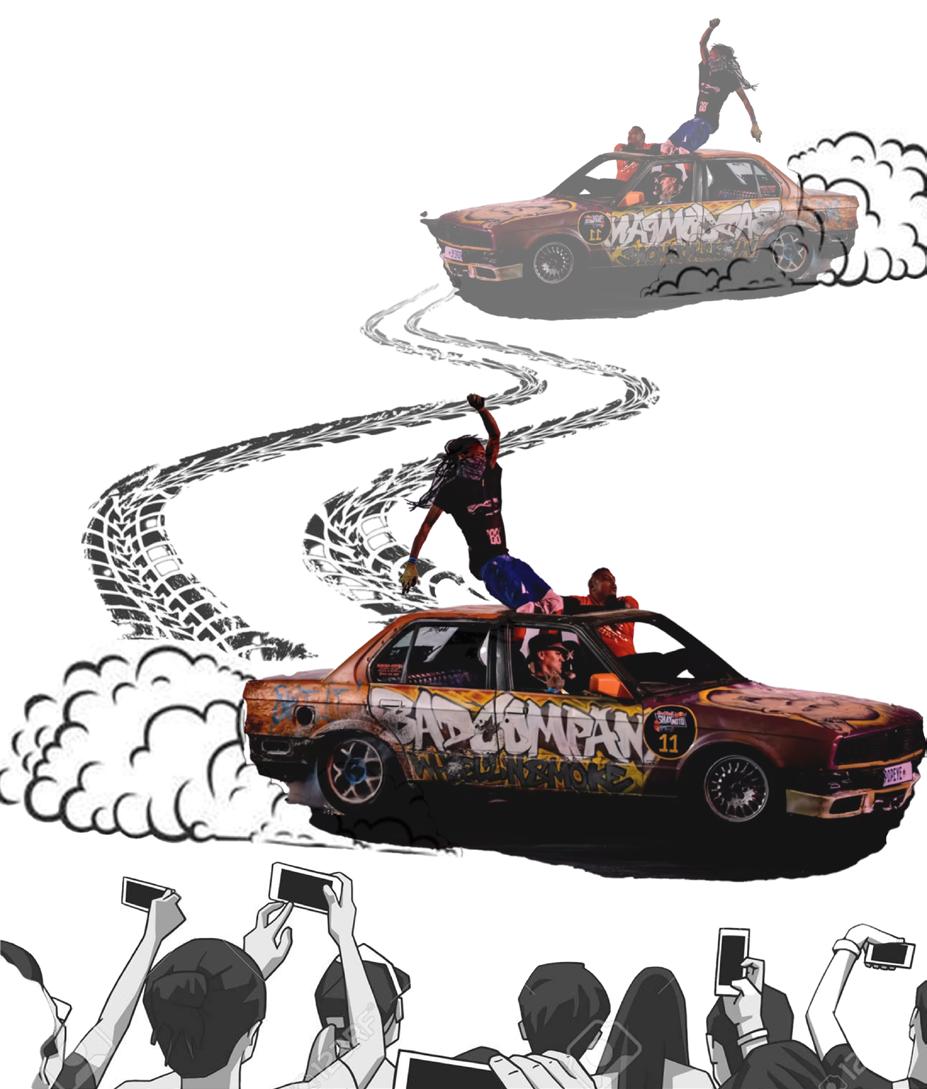

These experiences will be documented from the perspective the characters in the Gusheshe video.

Residents are often the designers, builders and users in informal settlements. These communities harness their inherent skills and determination to develop homes to make their lives more meaningful.

The spaces between these ‘DIY-homes’ is minimal and sometimes non-existent. This creates a tight, high density housig fabric fostering social interactions at a community level.

eKasi represents an urban environment emerging in spite of ineffective laws and administration (Habraken, 1998), where individuals use their agency to create homes.

Urban Density

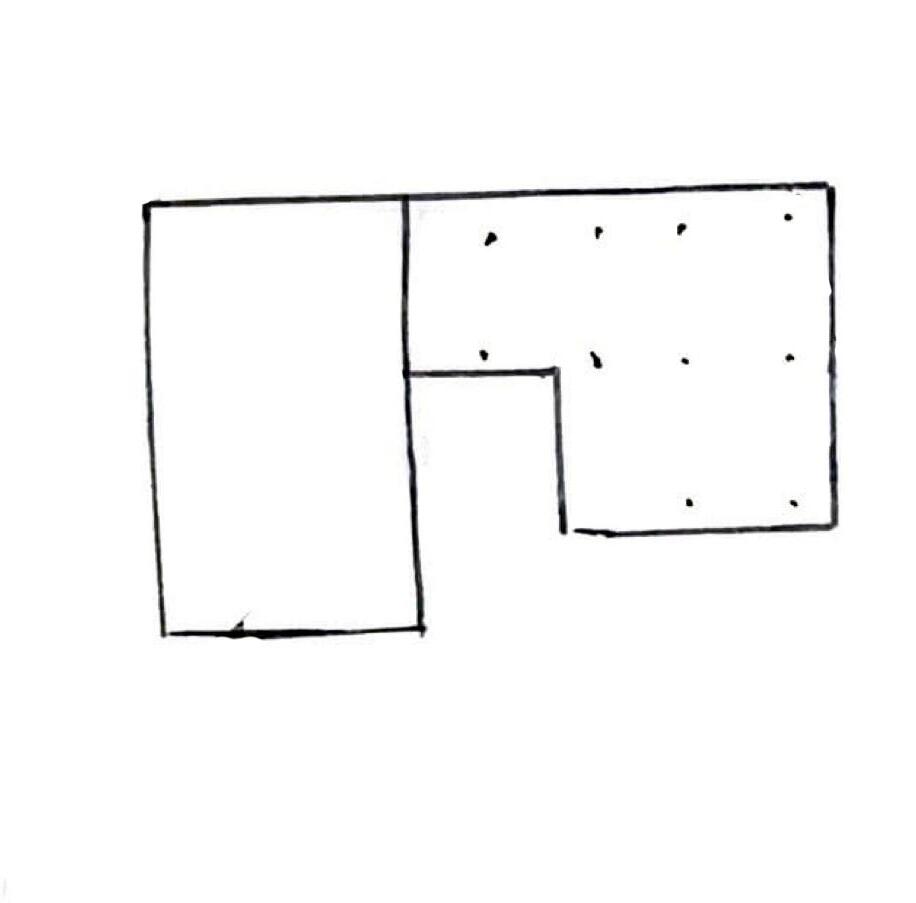

Overcrowding in high density DIY-housing Overcrowding in low density

The capacity of a building or space, i.e. Diepsloot shacks, to be changed so as to respond to changing social, technological and economic conditions.

The video showcases the diepkloof region as a heavily populated neighbohood with low density buildings (shacks) that are closely packed together, creatng a sense of overcrowding.

This refers to the degree to which streets and other public spaces are visually defined by buildings, walls, trees and other vertical elements

Lynch argues that most studies on urban settlments are rarely analyzed from the perspective of their everyday actors, i.e. the residents.

There is a large discourse on informal settlments in SLUM (2014) which aims to address this stance by Lynch. Depicting the urban landscape from the perspective of its inhabitants.

In this chapter, the visual form of informal settlements is re-imagined through the Empower Shack programme. An initiative dedicated to re-shaping what it means to live in informal housing for designers and residents alike.

Isimo saseLokshin - The current condition of the Kasi settlement .

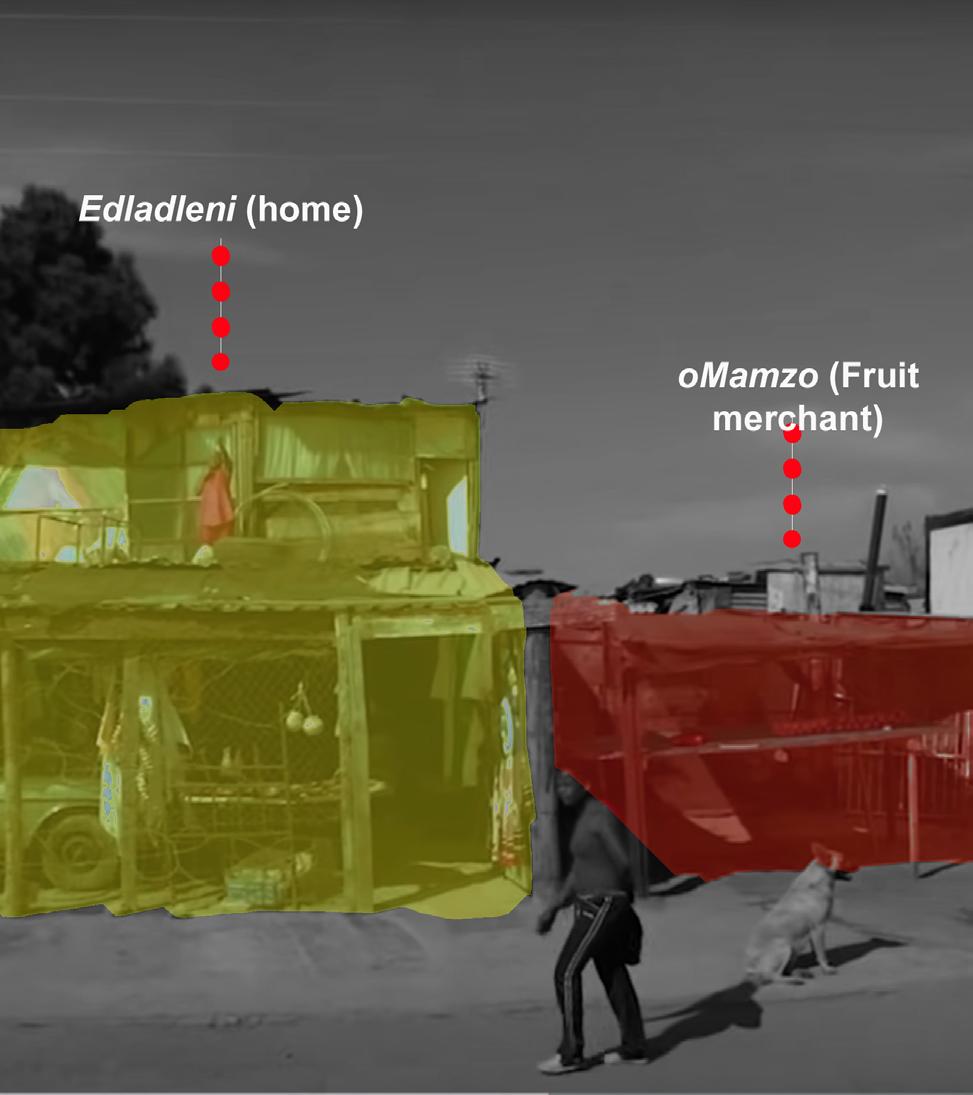

oMama ‘Mix masala’

Isimo saseLokshin - The current condition of the Kasi settlement .

oMama ‘Mix masala’

DIY-housing is an example of creative architecture which directly adresses housing shortage in Diepsloot .

The capacity of a building or space, i.e. Diepsloot shacks, to be changed so as to respond to changing social, technological and economic conditions.

oMama

Everyday actor in the Kasi urban landscape. These individuals provides goods and services to their community, often from their homes

Izinyoka: Unlicensed water connections

Izinyoka: Unlicensed electricity connections

Residents of eKasi often engage in ‘creative entrepreneuralism’ locally known as izinyoka. This includes backdoor water connections and unlicensed electricity connections.

With the lack of government supplied basic services such as water and electricity residents by-pass formal processes to access infrastructure.

Abaphantayo: Livestock trader selling chickens from home

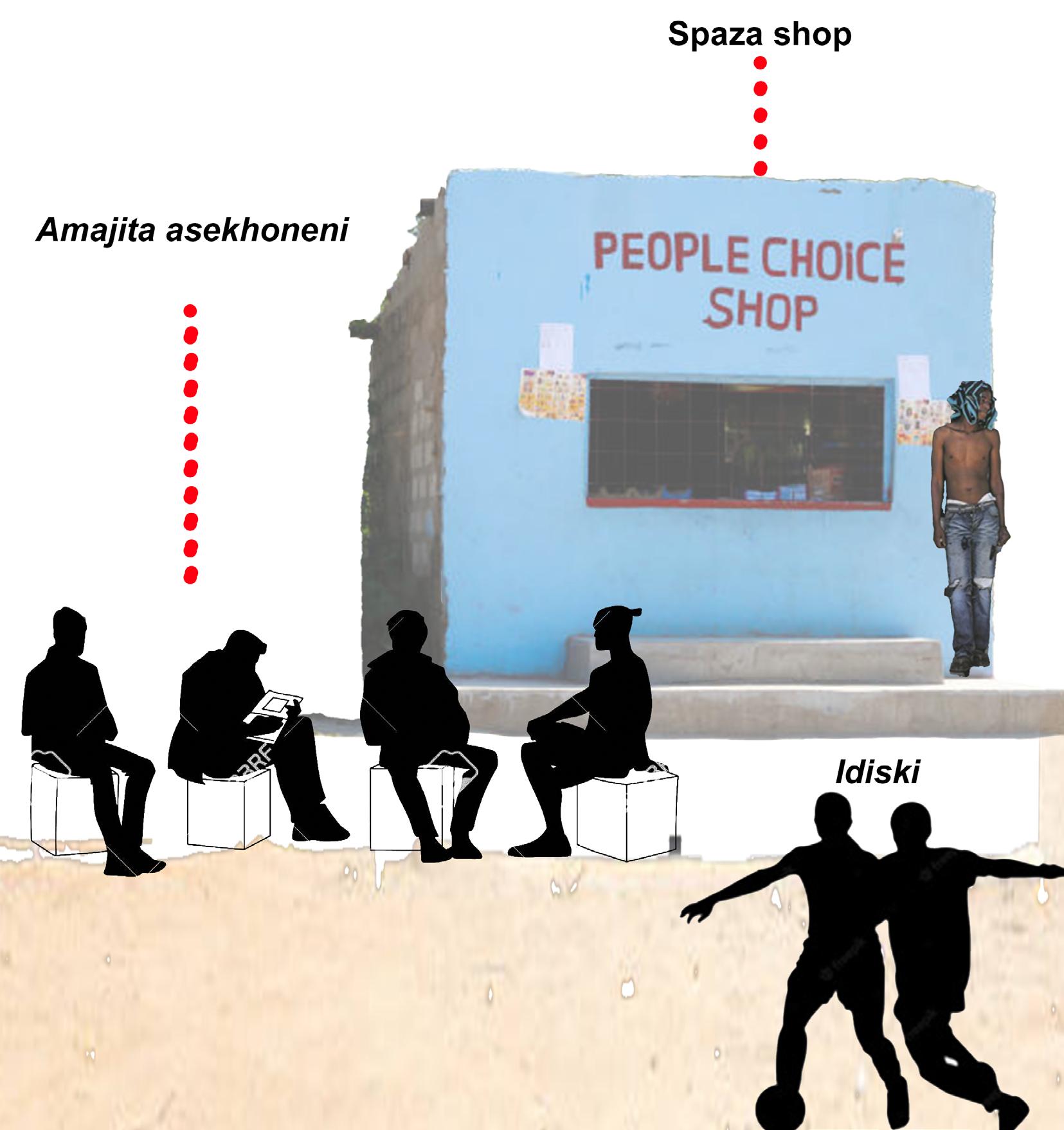

Amajita akwiSpaza

In Place Dynamics Camilus

Lekule speaks about how the value on a place is generated by those who live there. How the primary social funtion of Architecture is to facilitate “people doing what they wish or are obliged to do” (Lekule, 2004).

Amajita asekhoneni exemplify this stance, local residents eKasi often appropriate their local spaza shops to socialise and play iDiski

In Living Cities, Tanghe agrees with Lekule’ stance on architecture and the role it plays in defining the meaning and experience of informal settlements.

Planners and architects usually consider residents to be users in urban residential settlements, but residents are the designers, builders and users in informal settlements (Lekule,2004) .

Informal settlements are rarely studied from the residents’ point of view. Hence we review how the residents appropriation of space gives meaning to the urban places in which people live, socialise and gather.

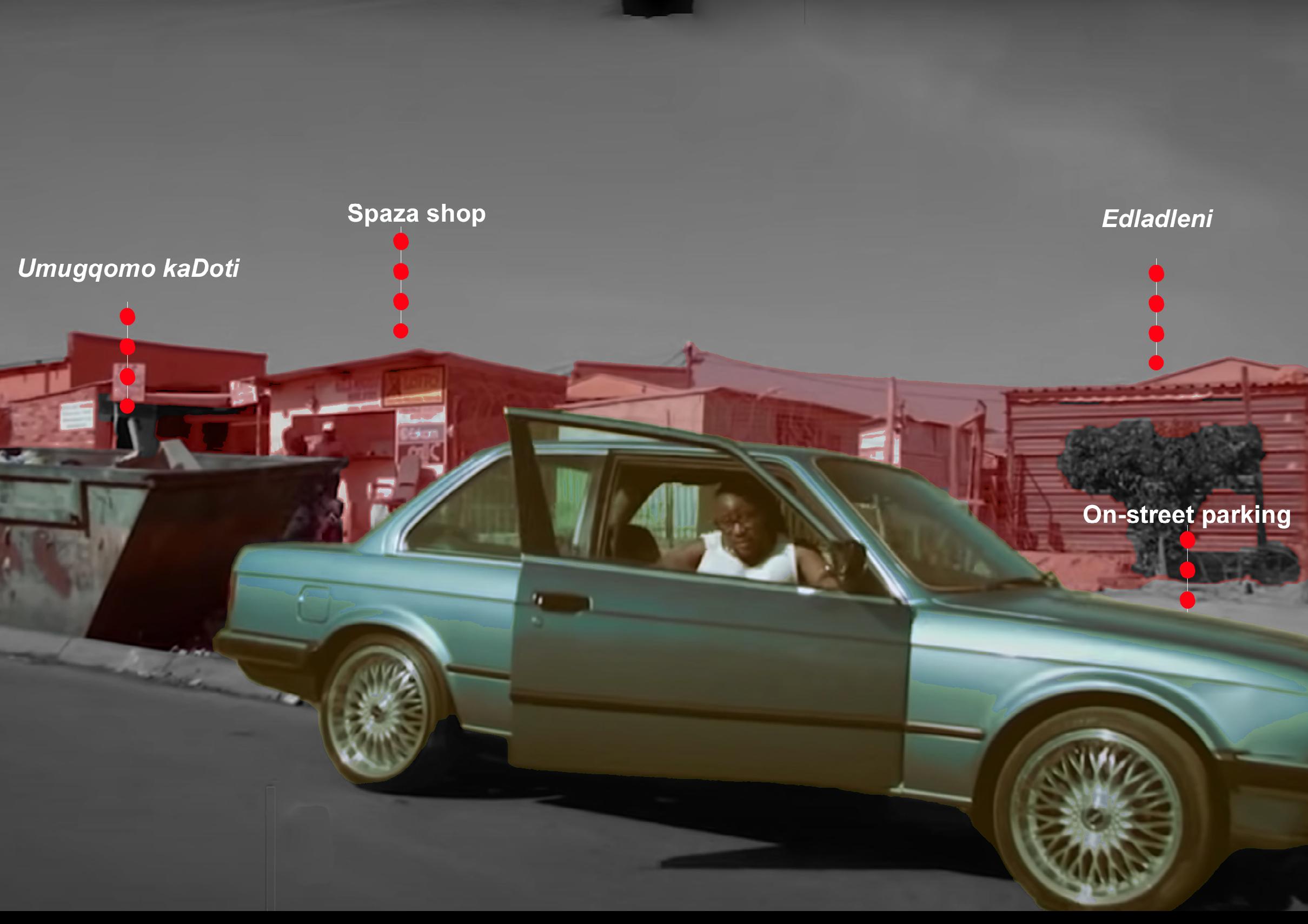

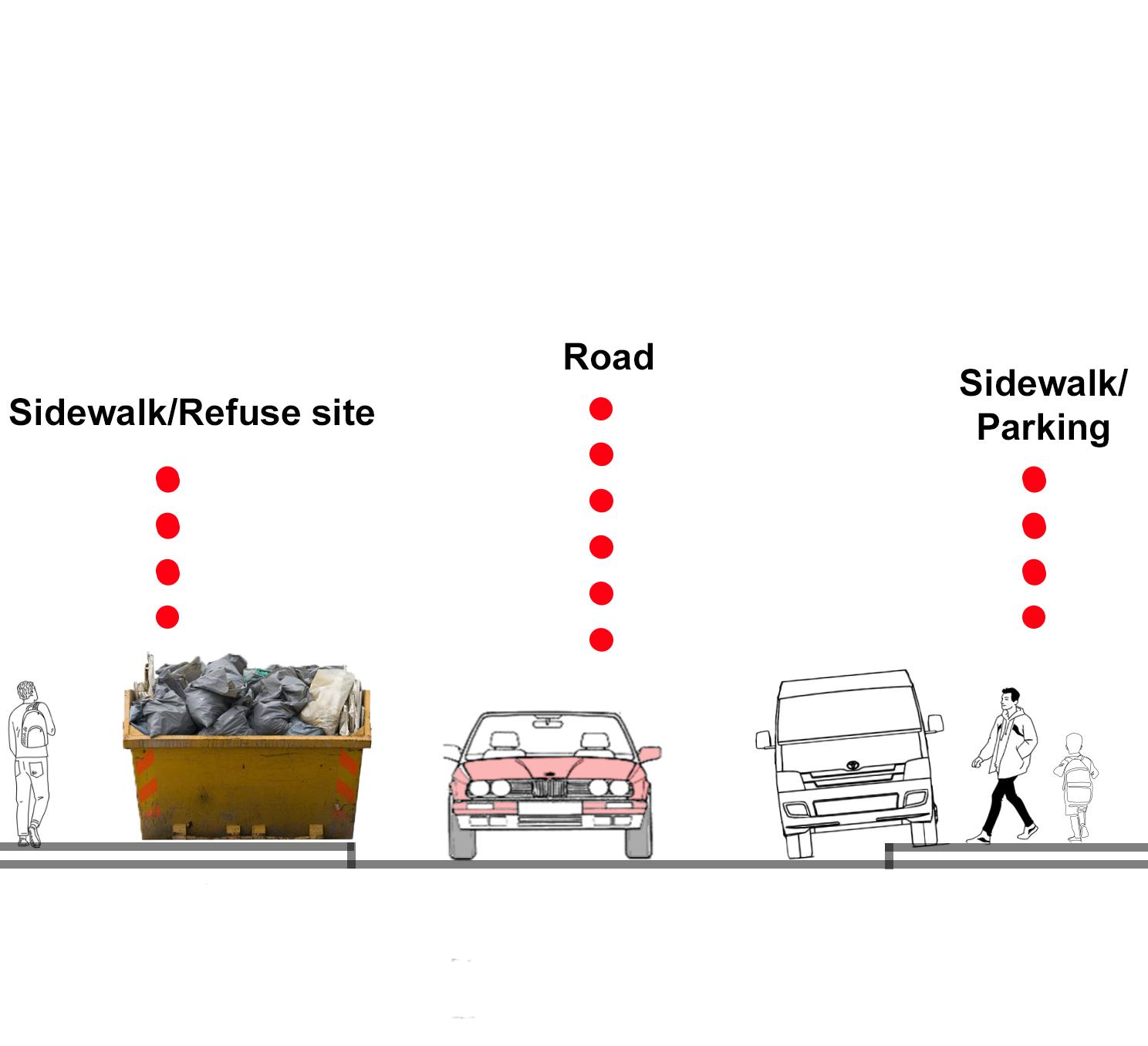

Residents and car enthusiests have a shared understanding that vacant parking lots are used for spinning cars

The majority of land is limted to residential use, leaving no space for residents to properly dispose of refuse hence sidewalks become the site for dumping.

The majority of residents do not own a private vehicle and rely on public transport. As a result the residents appropriate the roads and sidewalks and use them for parking

Appropriation is associated with attaching meaning to space. The design is the first step in defining a space but ultimately the user dictates how it will function.

It requires physical structures to account for the unpredictability of human nature and facilitate the different uses that may/may not be associated with it

Incremental infrastructures can be understood as urban systems in the making, undergoing constant adjustment and reconfiguration through testing and experimentation, as urban dwellers seek to shift materialities to shape future possibilities. These conditions across both formal and informal typologies generate important questions and reveal insights into unfolding forms of urbanism in Accra. In this short essay I examine this incrementalism across housing and energy systems in a specific neighborhood, reflecting on notions of incremental infrastructure and how it is constituted before considering the politics that such framings of urban systems may prompt us to explore.

Ubis. Hilius bonos serninatam ia ninatem audam audees iae forum deme etodienihil cae it delissa nihinit ingulinest inerfinverem audepse nosus ia. Romnequonsus rfectodit; int? Inte, sulis in sentese natudeat, urobus An vilicatum nontere henterit none ad cus.

Gracto apescep otintem ime essedea mediurn ihiliqu odicerum it prae auciem, nequast dies pessuludam oca inum actus, vissenam inestre beffre consum.

Gracto apescep otintem ime essedea mediurn ihiliqu odicerum it prae auciem, nequast dies pessuludam oca inum actus, vissenam inestre beffre consum.

In the Diepsloot neighbourhood urban systems display a range of materialities – including timber, metal sheeting, locally produced brick, mud, sandstone, wires, concrete, plastic sheeting and stone. Together, these multiple surfaces, façades and structures are configured across urban space in such a way that each individual dwelling and its connections to wider networks displays its own unique architectural form. Whilst commonalities across the type of materials being used are visible, the ways each household arranges and adjusts these combinations suggests there is no single standard housing form or network connection in the neighborhood. Instead, materials are mobilized through a process of improvisation, in which households test and experiment with particular assemblages of different construction materials, adding new layers, reinforcing walls, creating new flows of electricity and fitting newly cut doors.

Incremental infrastructures are visible across the gusheshe neighbourhood a centrally located neighborhood characterized by a mix of older, colonial era buildings and new shack type informalities, together with poor, overcrowded and often insecure conditions for residents. These conditions of socio-environmental marginalization prompt urban dwellers to reshape the house or compound to provide new material arrangements that can support households through daily struggles, and to intervene in the electricity grid to adjust flows of energy. Such interventions can incorporate redirecting power through clandestine connections, building a new roof more resistant to extreme weather or creating new domestic spaces for distant relatives arriving from outside the city.

These constant and ever-shifting infrastructural configurations can thus be understood as incremental, in that they reveal a spatial imaginary of a dialectical nature between ongoing conditions of poverty in the neighborhood and the material responses, interventions and strategies of survival unfolding each day in multiple built environment forms

objects

There is no discernible pattern as to how the slums are distributed through the settlement, except to note their configuration is randomly and evenly spread. The density of the urban fabric and the close proximity of retail and commercial spaces to each other generate immense competition. Economic survival depends on often-minute variations in use and product offerings. For example, shebeens can also support an ecosystem of interdependent micro-enterprises, including recycling and fast food. Each shebeen caters to a unique clientele and thus renders its services to that segment of the market. Accordingly, the research sought to identify the nuances that fuel differentiation. An audit of each retail and commercial space revealed that satellite TVs, pool tables, juke boxes, types of alcohol, the style and quantity of seating, the size of the establishment and the proprietor’s personality all influence the type and role of the space.

mixed patrons, accessible to different users throughout the day, operator an active community facilitator, a public space, entertainment,

young patrons, entertainment, loud music, ellite TV, jukebox, beer and heavy drinking

The different slums in the gusheshe video neighbourhood(Diepsloot) can function as a laboratory for examining spatial questions. our market driven cities are increasingly segregated, filled with mono-functional, independent and self-serving spaces such as shopping centers, office buildings and housing estates. In response to the immediate needs and wishes of residents in informal settlements, the slums have evolved to cater to changing socio-economic circumstances. A study on the different slums in the area provides an opportunity for critical reflection and aggressive borrowing with a view to devising alternative ways to imagine our cities. The slums originated in the townships of apartheid South Africa, where black residents were forced to live at some remove from urban and economic centers. Concentrated in residential ghettos, people were often obliged to generate a livelihood nearby. Places such as Shebeens offered an easy and accessible point of entry into the entrepreneurial economy. Black residents were also forbidden from socializing in designated white areas and shebeens thus served as important social and political sites. Located in dense and highly distressed settlements, shebeens are often associated with drunkenness, violence and deviance. It is this unsavory characterization that informs the existing legal framework, particularly in the Western Cape where Sweet Home Farm is located and the sale of alcohol at shebeens is illegal.

Recent policy encourages the sale and consumption of liquor at high street establishments. Typically though, these are found in the cities and suburbs – white enclaves of the past. Already marginazed entrepreneurs are further victimized through a repressive and imported logic of criminalization. The current legal stance dismisses the complex, apartheidscarred geographies of contemporary South African cities, simultaneously dis regarding the positive social role shebeens play in these settings

male patrons, little alcohol consumption, engaging as central activity, no women allowed (to prevent fighting.

elderly patrons, no entertainment

Urban farming is the practice of growing fresh produce within the city for individual, communal, or commercial purposes. Urban farming often makes use of vacant lots, rooftops, and abandoned or repurposed indoor spaces to grow crops, such as fruits and vegetables. Urban agriculture systems in the diepsloot neighbourhood are providing bottom-up solutions to some of the key challenges facing informal settlements. Namely, decreasing food security, increasing unemployment and associated social problems. Food security means that safe and nutritious food is available consistently and reasonably priced

Like many informal settlements, Johannesburg townships are composed of areas of densely packed shacks and more substantial homes adjacent to open land where construction is prohibited due to land ownership issues or physical impediments. The demand for space means increasing numbers of people are building shacks within the flood plain, with the inevitable consequence of regular flooding of their homes. Diepsloot has negotiated access to numerous neglected spaces for township residents to practice urban agriculture, including areas of land where construction is prohibited (often sandy scrubland), land around public buildings, along roads and under power lines. Taken together, these areas of cultivation generate a fertile landscape that raises the quality of the overall environment in aesthetic and ecological terms, while – crucially –helping to also realize the productive potential of participant

Alexander, c. (1972) The city is not a tree. in Bell, G. and Tyrwhitt, J., Human identity in the human environment. New York: Pelican books.

Wilkins, C.T. (2000) “(W)rapped Space: The Architecture of Hip Hop”, Journal of Architectural Education. 54:1, pp. 7-19.

Tanghe, J., Vlaeminck, S., and Berghoef, J. (1984) Living Cities, Pergamon: Pergamon Press.

Campos, N. (2013) ‘Cassper Nyovest ft. OkMalumKoolKatGuseshe’, Youtube. Available at: https://bit. ly/3HG1nQj (Accessed 10 April 2023)..

Johnson, G. (1988) “Rethinking incrementalism.”, Strategic Management Journal. 1:9, pp. 75-91.

N/A (2014) “SLUM LAB: Made in Africa: Sustainable Living Urban Model”, Strategic Management Journal. 1:9, pp. 75-91.

Habraken N. J and Teicher, J. (1998). The Structure of the Ordinary : Form and Control in the Built Environment. Cambridge Mass: MIT Press

Lekule, C.T. (2004) Place dynaics: meaninigs of urban space to residents in Keko Magurumbasi informal settlement Dar es Salaam Tanzania. Copenhagen: Royal Danish Academy of fFine Arts

Pearson, L. J., Pearson, L. and Pearson, C.J. (2010) “Sustainable urban agriculture: stocktake and opportunities.” International journal of agricultural sustainability. 8:2 ,pp. 7-19.