How Minnesota’s Not-for-Profit Hospital Systems Profit From Their Tax-Exempt Status Money for Nothing?

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Johann Benson, Senior Research Specialist at the Minnesota Department of Revenue, for providing property tax data and explaining how Minnesota tracks and assesses exempt properties, for which we relied upon for our analysis. This report would not have been possible without his expertise.

Executive Summary

• Three in four hospitals in Minnesota are organized as “not-for-profits.” As a condition of tax exemption, not-for-profit hospitals are required to provide charity care to the poor and low-income in the communities they serve. However, neither federal nor state law has established a minimum requirement as a condition of exemption, calling into question whether not-for-profit hospitals are providing sufficient levels of charity care. A number of recent studies have found that many of the nation’s not-for-profit hospitals have become virtually indistinguishable from for-profit hospital corporations. As Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison has stated, “[t]here is a growing consensus that there is very little difference between a forprofit and nonprofit hospital when it comes to behavior.”

• Minnesotans remain unaware of the full cost burden of not-for-profit hospital tax exemptions to taxpayers and communities. Between 2018 and 2022, Twin Cities and Duluth-based systems, Allina Health System, Children’s Minnesota, Essentia Health, Fairview Health Services, HealthPartners, North Memorial, and St. Luke’s Hospital, received a combined $3.9 billion in federal, state, and local tax exemptions, despite returning just $607.1 million in charity care to local communities.

“Between 2018 and 2022, Twin Cities and Duluth-based systems, Allina Health System, Children’s Minnesota, Essentia Health, Fairview Health Services, HealthPartners, North Memorial, and St. Luke’s Hospital, received a combined $3.9 billion in federal, state, and local tax exemptions, despite returning just $607.1 million in charity care to local communities.

• In Minnesota, several of the most prominent health systems that brand themselves as deeply engaged with the community provide shockingly low levels of charity care. The total shortfall, or loss to the public, which is the total value of tax exemptions for Twin Cities and Duluth-based hospital systems reduced by the $607.1 million in charity care they provided for the combined fiscal years 2018 to 2022, is estimated to be $3.3 billion. Allina Health System, HealthPartners, and Fairview Health Services are responsible for the three largest charity care shortfalls.

• Driven to maximize profits, executives at these large health systems have spent less and less on charity care in recent years. While charity care spending briefly increased on average during the COVID-19 pandemic, overall, Twin Cities and Duluth-based hospital systems are spending less as a percentage of total expenses on charity care, as compared to 2018. The decline is even more significant when looking at historic levels: in 2013, these systems spent on average 0.78 percent of their expenses on charity care, down to 0.41 percent a decade later.

• At the same time, not-for-profit hospital tax exemptions appear to provide significant private benefits to healthcare executives in the form of excessive compensation, which continues to spiral upward. This is despite the legal requirement that not-for-profit hospitals, like other not-for-profit institutions, not be organized or operated to benefit private individuals.

• Minnesota’s reputation as a great state to live in masks troubling realities, especially for our less affluent and working-class communities. Minnesota healthcare systems bear a substantial share of responsibility for exacerbating existing inequities. Communities of color, those with lower incomes, and rural Minnesotans are all disproportionately affected by medical debt and hospital/service closures. Additionally, state and local tax exemptions deprive the government of the necessary revenue to fund public services, including public schools where students, parents, and teachers across the state currently face devastating cuts.

• Our goal is not to propose that Twin Cities and Duluth-based hospital systems lose their generous tax exemptions and transition to for-profit status. Rather, hospital executives must take meaningful action and significantly increase the charity care they provide to the communities they serve. Federal, state, and local policy needs to be updated to hold hospitals accountable to their communities. Municipalities should start by reviewing the current property tax exemptions afforded to not-for-profit health systems and explore options to collect additional revenue and commitments from not-for-profit health systems.

Introduction

The large not-for-profit hospital chains that dominate Minnesota’s healthcare landscape receive tens of millions of dollars in exemptions to federal, state, and local taxes annually. Nationally, these tax exemptions cost federal, state, and local governments a combined $37.4 billion in 2021.i In exchange for receiving enormous tax exemptions, not-for-profit hospitals are required to provide charity care to the poor and low-income in the communities they serve.ii However, neither federal nor state law has established a minimum requirement as a condition of exemption, calling into question whether not-for-profit hospitals are providing sufficient levels of charity care.

Source: See Appendix A – Methodology

Despite their generous tax exemptions, notfor-profit hospitals and health systems are not holding up their end of the bargain. As investigative reporters from The New York Times concluded in 2022: “[i]n recent decades, many of the hospitals have become virtually indistinguishable from for-profit companies, adopting an unrelenting focus on the bottom line and straying from their traditional charitable missions.”iii Minnesotans remain unaware of the full cost burden of hospital tax exemptions to taxpayers and communities even as three in four hospitals are organized as “not-for-profits.”iv

Between 2018 and 2022, Twin Cities and Duluthbased not-for-profit hospital systems received a combined $3.9 billion in federal, state, and local tax exemptions, despite returning just $607.1 million in charity care to local communities (see Figure 1).

In public policy circles, tax exemptions are often considered a type of expenditure because they represent an indirect form of taxpayer spending. In theory, this taxpayer expenditure should provide a comparable public benefit, but in actual practice, not-for-profit hospital tax exemptions resemble much more a gift of taxpayer funds: large sums of money handed over year after year, for in far too many cases, little in return.v This is because as tax law professor John D. Colombo has stated: “the standard nonprofit hospital doesn’t act like a charity any more than Microsoft does — they also give some stuff away for free…hospitals’ primary purpose is to deliver high quality health care for a fee, and they’re good at that. But don’t try to tell me that’s charity. They price like a business. They make acquisitions like a business. They are businesses.”vi

In Minnesota, several of the most prominent health systems that brand themselves as deeply engaged with the community provide shockingly low levels of charity care. The total shortfall, or loss to the public, which is the total value of tax exemptions for Twin Cities and Duluthbased hospital systems reduced by the charity care they provided for the combined fiscal years 2018 to 2022, is estimated to be $3.3 billion (see Table 1).

Source: See Appendix A – Methodology

Three systems – Allina Health System, HealthPartners, and Fairview – are responsible for the three largest charity care shortfalls. These shortfalls call into question whether these hospital systems deserve their rich tax exemptions. If these tax exemptions are to remain in place, policymakers should update federal, state, and local laws and regulations to ensure hospitals are addressing the needs of the most vulnerable.

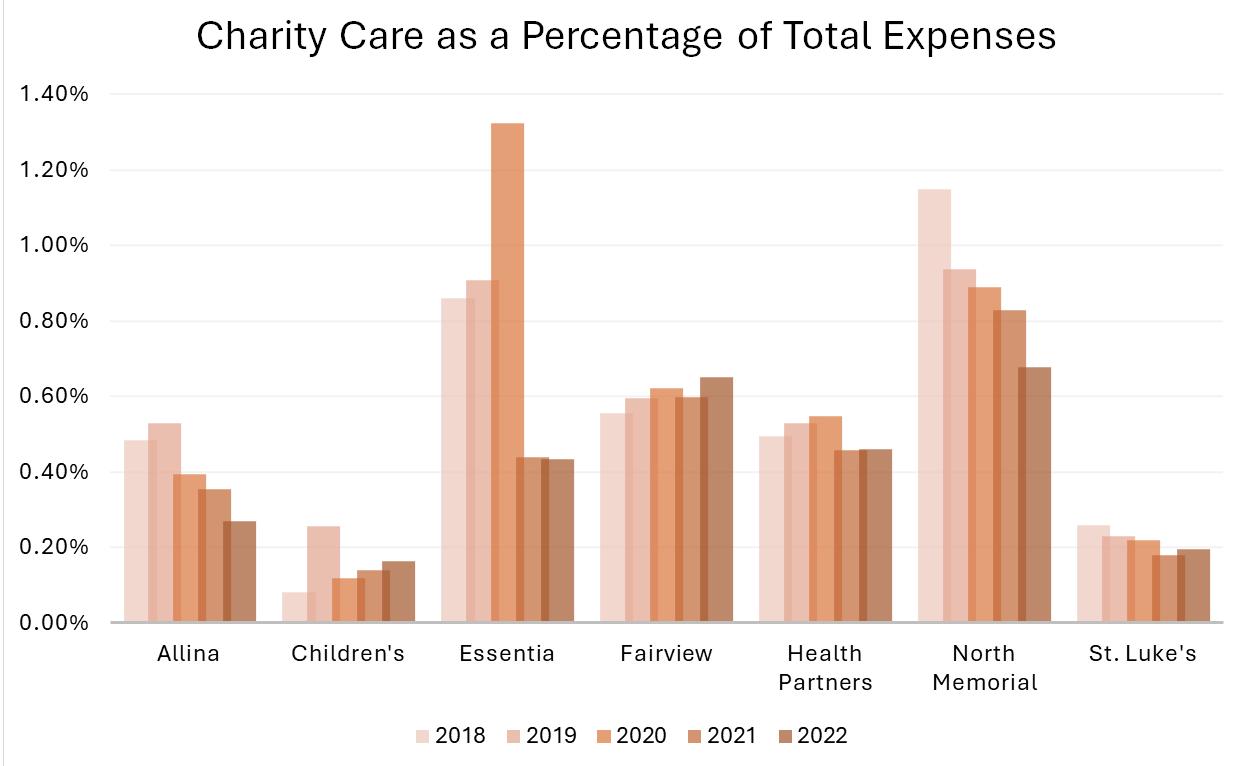

Driven to maximize profits, executives at these large health systems have spent less and less on charity care in recent years. In 2022, Twin Cities and Duluth-based not-for-profit hospital systems on average spent less as a percentage of total expenses on charity care than in 2018. The decline is even more significant when looking at historic levels: in 2013, these systems spent on average 0.78 percent of their expenses on charity care, down to 0.41 percent a decade later (see Figure 2).

“Three systems – Allina Health System, HealthPartners, and Fairview – are responsible for the three largest charity care shortfalls.

2. Charity Care Spending as a Percentage of Total Expenses by Twin Cities and Duluth-based Health Systems 2018 to 2022

Source: Analysis of audited financial statements for Fiscal Years 2013-2022

Instead of incentivizing adequate levels of charity care spending, our current system helps to create a millionaire class of executives whose compensation continues to spiral upward. This is despite the legal requirement that not-for-profit hospitals, like other not-for-profit institutions, not be organized or operated to benefit private individuals.vii As Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison has stated, “[t]here is a growing consensus that there is very little difference between a for-profit and nonprofit hospital when it comes to behavior.”viii

Minnesota has been identified as a top state for healthcare,ix but this assessment masks troubling realities, especially for Minnesota’s less affluent and working-class communities. Several flagship hospitals sit in some of Minnesota’s lowest-income communities, including those that are majority black and brown (see Appendix B). Nearly five years after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 ignited a worldwide dialogue and examination of racial inequities and oppressive systems, large disparities persist: people of color have higher rates of infant mortality,x higher rates of diabetes,xi deaths caused by heart disease,xii and are more likely to forgo care, including crucial routine medical care.xiii Although the percentage of Minnesotans without health insurance dropped to its lowest-measured level in 2023, Black and Latino Minnesotans are significantly more likely to be uninsured.xiv This is all part of “the Minnesota Paradox,” a term coined by Professor Samuel L. Myers Jr. to describe the “simultaneous existence of Minnesota as the best state to live in, but the worst state to live in for blacks.”xv

Hospital executives play a key role in deepening the racial, geographic, and class divides in our state. One hundred million Americans live with medical debt, the result of high prices, barriers to financial assistance, and aggressive collection practices.xvi Medical debt is especially pernicious as it relates to the cycle of poverty and poor health: people may delay necessary care to prioritize basic needs, in turn exacerbating their health issues and accumulating more debt in the process. Vulnerable communities, including the uninsured and those with lower incomes, are more likely to have medical debt.xvii Communities of color are also disproportionately affected – at least half of Black and Hispanic adults report having debt, compared with 37 percent of White adults.xviii The crisis of medical debt is not limited to urban settings. Rural Americans, who are more likely to be uninsured, and have overall worse mental and physical health, have higher rates of medical debt.xix

“Last fall, St. Paul Mayor Melvin Carter announced that the City of Saint Paul, in partnership with Undue Medical Debt would abolish nearly $40 million of medical debt for 32,000 Saint Paul residents.xx Following the model established by other states – using leftover American Plan Rescue Act funds – made sense, Carter explained, to serve “communities who have been historically disinvested in, who have had the odds stacked against them from the start.”xxi As the Mayor himself recognized, the program represented an intervention, rather than a solution to the problem of medical debt.xxii Patients having trouble paying their bills continue to accrue new debt, even if their old debt has been forgiven. Worse yet, Fairview Health Services was labeled as a “partner” in the initiative and received undue credit, given that it is responsible for 30 percent of all medical debt filings in the statexxiii and through this initiative received partial payment for debts it may never have been able to collect.xxiv

Vulnerable communities, including the uninsured and those with lower incomes, are more likely to have medical debt. Communities of color are also disproportionately affected – at least half of Black and Hispanic adults report having debt, compared with 37 percent of White adults.

Across the state, Minnesota healthcare executives have cut or reduced services and closed hospitals, undermining access to care and exacerbating inequities.xxv Patients, including expectant mothers, are forced to travel farther even in the harsh Minnesota winters, increasing the risk of maternal morbidity and adverse infant outcomes such as stillbirth.xxvi Cuts to obstetrics are particularly devastating for rural Minnesotans. Today, nearly 40 percent of women in Greater Minnesota live over 30 minutes from a birthing hospital compared with approximately 12 percent of those living in urban areas.xxvii

State and local tax exemptions also deprive the government of the necessary revenue to fund public services, including public schools, which are largely funded by state and local property taxes.xxviii Students, parents, and teachers in school systems across the state currently face devastating cuts unless they step in to fill shortfalls. In November 2024, Duluth Public Schools announced a $5 million deficit for the 20252026 school year, the equivalent of 50 full-time teacher positions, marking the second year of cuts.xxix

This report looks specifically at the chains based in the Twin Cities and Duluth – Allina Health, Essentia Health, Fairview Health Services, HealthPartners, North Memorial, Children’s Minnesota, and St. Luke’s Hospital – and examines whether these hospital systems are addressing the needs of the communities they serve in proportion to the significant tax exemptions they receive.

Nearly forty years after the 1986 repeal of the not-for-profit tax exemptions for Blue Cross/Blue Shield, it is unclear whether tax exemptions for not-for-profit hospitals will meet a similar fate.xxx Will not-for-profit hospital tax exemptions survive Trump’s second administration?xxxi If the nation’s tax exemptions for not-for-profit hospitals are to survive, not-for-profit hospitals must return to their historic roots and commit themselves to a new social contract with America’s patients and their communities, including the poor and working-class patients most squeezed by today’s stark and growing economic inequalities.

History of Health Systems

Many of the large health chains that dominate Minnesota’s landscape have a long history, with several tracing their roots back to the nineteenth century. Allina’s United Hospital in St. Paul started its life as ChristChurch Orphan’s Home and Hospital, established by Episcopal settlers in 1857,xxxii a year before Minnesota was first admitted to the Union.xxxiii Similarly, St. Luke’s opened as Duluth’s first hospital in 1881. xxxiv The hospital, initially located in an old blacksmith’s shop, was established by a group of Episcopalians responding to a typhoid outbreak.xxxv Hospitals continued to spring up across the state in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Beginning in 1888, a group of Benedictine nuns established several hospitals in Greater Minnesota, including St. Mary’s in Duluth, St. Joseph’s in Brainerd, and St. Vincent in Crookston,xxxvi all now part of Essentia Health. Those hospitals were funded by fees from patients and “lumberjack” tickets, an early form of health insurance offered to men working in nearby lumber and mining camps.xxxvii

The postwar years brought significant changes to the state’s hospitals. Between the Great Depression and the mid-1940s, few hospitals

were built in Minnesota, even in communities that needed them,xxxviii an exception being North Memorial, which opened as Victory Hospital in 1940.xxxix In 1946, Congress passed the Hospital Survey and Construction Act, known as the Hill-Burton Act, providing grants and loans to hospitals, nursing homes, and other health facilities for construction and modernization.xl Between 1950 and 1973, 120 general hospitals in Minnesota received funding from the federal Hill-Burton Act.xli Anticipating massive growth in the inner-ring suburbs around the Twin Cities in the postwar years, Fairview executives followed the exodus of people and capital to the suburbs.xlii In an expansion strategy that may have been inspired by the practice of branches in banking,xliii Southdale Hospital in Edina became one of the first “satellites” in the country, built on land donated by the Dayton Corporation.xliv

The year 1957 saw the creation of Group Health, one of the first consumer-governed, prepaid health plans in the country.xlv Beginning with the Como Clinic in St. Paul, the organization provided health plan coverage and employed physicians to provide patient care, which remains HealthPartners’ model today.xlvi

Hospitals had long seen the rationale in working with one another. Following financial difficulties due to the stock market crash of 1929, several St. Paul hospitals joined together to form the Minnesota Hospital Service Association, and shortly thereafter joined with the Minneapolis Hospital Service Association.xlvii A precursor to Blue Cross, the association engaged employers to provide contracted health care plans for their employees for a flat fee, guaranteeing a steady stream of revenue.

Over the ensuing decades, previously locally owned and operated hospitals started to consolidate into large systems. In the 1970s and 1980s, a series of mergers resulted in HealthOne, the first St. Paul-Minneapolis multi-hospital system, which then combined with LifeSpan and subsequently health insurer Medica to form Allina Health System in 1993.xlviii The following year, Minneapolis Children’s Medical Center and Children’s Hospital of St. Paul, first opened in 1924, merged, becoming one of the largest freestanding pediatric health systems in the United States.xlix

Today, the majority of Minnesota hospitals belong to a health system,l the largest of which is Allina Health, as measured by the number of available beds.li Several systems operate hospitals in the surrounding states of Wisconsin and North Dakota.lii The following table illustrates the size of the seven health systems included in this study.

Source: Analysis of bond disclosures, company websites, and internet searches

History of Not-for-Profit Tax-Exempt Status for Hospitals

The nation’s earliest hospitals were founded principally by religious and charitable organizations to tend to the sick and poor. Today’s notfor-profit hospitals and systems, often monumentally wealthy and glittering institutions, are their distant cousins. Over the course of their remarkable evolution, Rosemary Stevens has termed the nation’s hospitals “organizational chameleons” who have had: “the ability to present themselves both as private and as public institutions; as charitable organizations and as businesses, as technological successes and as vehicles for dealing with social failure (often expecting subsidies from the government).”lvi Similarly, Paul Starr has written that: “In developing from places of dreaded impurity and exiled human wreckage into awesome citadels of science and bureaucratic order, [hospitals] acquired a new moral identity, as well as new purposes and patients of higher status. The hospital is perhaps distinctive among social institutions in having first been built primarily for the poor and only later entered…by the more respectable classes.”lvii

Not-for-profit hospitals must meet certain criteria for tax exemption at both the federal and state levels. Not-for-profit hospitals may not distribute their surplus revenues for the benefit of individuals (i.e., owners or shareholders). Ironically, not-for-profit hospitals whose CEOs and other top executives have multimillion dollar compensation packages are often the quickest to raise this point when their levels of charity care and community benefit spending are questioned.

In theory, surplus revenues are supposed to benefit the community in which a not-for-profit hospital is located. In exchange, governments exempt not-for-profit hospitals from paying certain taxes imposed on for-profit enterprises: federal and state income taxes on profits, property taxes, and almost all state and local sales taxes. In addition, not-for-profit hospitals may seek financing through tax-exempt bonds and receive tax-deductible charitable contributions.

In Minnesota, as in other states, the business aspect of not-for-profit hospitals has become dominant as the purpose of the hospital shifts from a charitable organization serving the community to a business gaining profits through procedures for paying customers. The evolution of the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) rules and regulation of not-for-profit hospitals has fueled this change. Many examinations of tax exemption for not-for-profit hospitals fail to include the history of regulation prior to 1969. Before 1969, the federal government did in practice require not-for-profit hospitals to provide charity care in order to qualify as a not-for-profit and reap the tax breaks and other benefits provided by their not-for-profit status. By providing charity care, not-for-profit hospitals remained consistent with the “long-held stance of the IRS (and centuries of legal precedent in the charitable trust arena) that the “relief of the poor” constituted a charitable purpose.”lviii Though the tax codes provide no specific exceptions for hospitals under 501(c)3, not-for-profit hospitals have been recognized as tax-exempt at least since 1928. In 1954, the IRS issued rule, Rev. Rul. 56-185, 1956-1 C.B. 202 that codified “relief of the poor” as a charitable purpose. Rev. Rul. 56-185 established an important requirement addressing hospitals’ charitable obligations: “It must be operated to the extent of its financial ability for those not able to pay for the services rendered and not exclusively for those who are able and expected to pay.”lix Though an official threshold was never established, a hospital lacking a substantial charity care program would face “auditing agents [who would] almost always recommended denial or revocation of exempt status.”lx Auditors did, in fact, deny or revoke the not-for-profit status of hospitals if their charity care amounted to less than 5 percent of gross revenues.lxi

This clear obligation to provide charity care was turned upside down in 1969. Following the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, hospitals argued that the need for charity care would decline so that hospitals could not meet the IRS standard and that they should therefore be awarded more flexibility. The IRS responded with a new rule, Rev. Rul. 69-545, 19692 C.B. 117, altering the hospital exemption so that hospitals would no longer be required to provide charity care to qualify for their exemption: “Revenue Ruling 56-185 is hereby modified to remove…the requirements relating to caring for patients without charge or at rates below cost.”lxii Second, this rule established the “community benefit standard,” which states that: “The promotion of health, like the relief of poverty and the advancement of education and religion, is one of the purposes in the general law of charity that is deemed beneficial to the community as a whole even though the class of beneficiaries eligible to receive a direct benefit from its activities does not include all members of the community, such as indigent members of the community, provided that the class is not so small that its relief is not of benefit to the community.”lxiii In so ruling, the “promotion of health,” (i.e., providing medical care) itself became a charitable act. The charity is in providing health services even for a fee, thus exempting the need to provide those services to those who cannot afford the fee. Yet while there is no specific federal regulatory obligation to provide charity care, it remains generally understood by the public at large as a core component of the larger category of community benefits.lxiv

Following the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, hospitals argued that the need for charity care would decline so that hospitals could not meet the IRS standard and that they should therefore be awarded more flexibility.

Total Value of Tax Exemptions for Fiscal Years 2018 – 2022

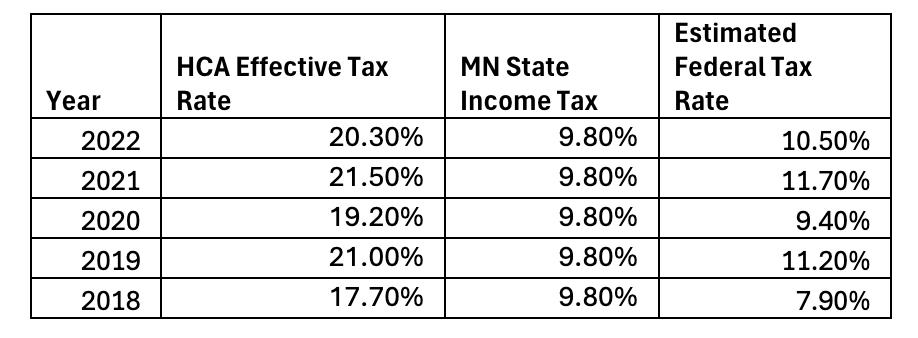

For the combined fiscal years 2018 – 2022, the total value of federal, state, and local not-for-profit tax exemptions for the seven hospital systems was estimated to be $3.9 billion. This is the total estimated subsidy provided to the systems as a result of their not-for-profit status. Out of the group, HealthPartners had the highest estimated tax exemption, at $1 billion, followed by Allina Health at $912.7 million, and Fairview at $817.8 million. These health systems benefit directly from federal and state income tax exemptions, as well as property and sales tax exemptions, which comprise 64 percent of the total value of exemptions (see Figure 3). Notably, the sales tax exemption was the largest component of all systems combined, as well as for four out of the seven individual systems. Other exemptions, including federal taxes deducted for charitable contributions, also benefit the health systems, albeit indirectly. Between 2018

and 2022, the charitable contribution category comprised 24 percent of the total exemption. For a complete explanation of how the value of the exemptions is calculated, see the methodology section in Appendix A.

The Failures of Non-for-Profit Hospitals in Minnesota State Hospital CEOs Earn as Much as Fifty Times the Average Minnesotan

By law, not-for-profit hospitals, which are non-profit 501(c)3 organizations, cannot be organized or operated to benefit any private individual lxv Per the IRS:

A section 501(c)(3) organization must not be organized or operated for the benefit of private interests, such as the creator or the creator’s family, shareholders of the organization, other designated individuals, or persons controlled directly or indirectly by such private interests. No part of the net earnings of a section 501(c)(3) organization may inure to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual. A private shareholder or individual is a person having a personal and private interest in the activities of the organization.lxvi

Despite the seemingly clear guidance of not-for-profit law, hospital CEOs continue to earn exorbitant salaries and compensation packages (see Table 4). These multi-million-dollar compensation packages put them far out of touch with the lived experience and daily struggles of average Minnesotans. Here the question arises: would the money now richly compensating these CEOs and other top hospital executives be more ethically spent providing charity care to those in need? What other policies, practices, programming, and other initiatives might hospital executives more invested in caring for their communities than profiteering put in place?

Inc.

North Memorial Health Care J Kevin Croston MD $2,285,767

St. Luke's Hospital Nicholas Van Deelen MD $1,066,238 17:1

St. Luke's Hospital Eric Lohn $1,207,284 19:1

Source: Analysis of health system 990 tax returns and Bureau of Labor Statistics data

Prolific Debt Collector Allina Health Denied Care to Patients in Arrears

An estimated 100 million Americans owe medical debt.lxvii Like many other forms of debt, medical debt is not evenly distributed across the population: people with disabilities, those in worse health, Black Americans, people living in rural areas, and those without insurance are disproportionately burdened.lxviii According to a recent Minnesota State Bar Association report, 17 percent of debt collection cases in Minnesota were for medical debt.lxix Medical debt can and does ruin lives.lxx Until recently, medical debt automatically transferred after death to a surviving spouse.lxxi The Minnesota Hospital Association opposed ultimately successful efforts to eliminate spousal liability, asserting such reforms were not in hospitals’ financial interest.lxxii

According to a recent Minnesota State Bar Association report, 17 percent of debt collection cases in Minnesota were for medical debt. Medical debt can and does ruin lives.

Unlike many healthcare providers that sell debts to independent firms for pennies on the dollar, Allina sues patients through its own for-profit subsidiary, Accounts Receivable Services LLC.lxxiii Though Accounts Receivable exclusively pursues debts for Allina, they do not advertise their relationship. Allina’s name and logo do not appear on Accounts Receivable’s website or outside its offices.lxxiv The Minnesota State Bar Association found that Accounts Receivable filed the second-highest number of medical debt lawsuits in the state, accounting for over 11 percent of medical debt cases.lxxv

Allina faced scrutiny in 2023 when a New York Times investigation found that the company had an explicit policy cutting off clinic services to patients who had at least $4,500 in outstanding bills.lxxvi The policy instructed staff to cancel appointments with patients and to lock their

electronic health records so they could not schedule future appointments. Providers raised concerns that they would have to turn away patients with health risks. As Dr. Rita Raverty concluded, “Nobody wins when patients can’t get preventative care … It creates worse disease outcomes when you’re not catching things early.” Allina employees also alleged that some of the patients cut off had low enough incomes to qualify for Medicaid and should have received free care under Allina’s financial assistance policy, which patients may not have been aware of. An Allina spokesperson did not dispute this claim. Allina executives later reversed the policy, but only after the Minnesota Attorney General launched an investigation into the system and its practices.lxxvii

Fairview Health Services Closes Two Hospitals During the Pandemic

Patients count on local hospitals for care when they are at their most vulnerable. Hospital executives directly undermine this access when they decide to close or consolidate services. In 2017, Fairview acquired HealthEast,lxxviii which historically served low-income communities and communities of color in the East Metro.lxxix An MPR News headline announcing the deal read: “Fairview rescues struggling HealthEast in merger.” However, it quickly became clear that Fairview CEO James Hereford had little interest in continuing to operate these hospitals. Though Hereford wrote about an “affordability crisis” in healthcare,lxxx his “bold new vision”lxxxi involved closing Bethesdalxxxii and and St. Joseph’slxxxiii hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These closures were predicted to hit mental health care particularly hard,lxxxiv a concern that was validated by research published in 2023 showing that patients facing mental health crises stay in Minnesota’s emergency rooms 25 hours longer than necessary.lxxxv

The primary cause: a lack of inpatient psychiatric beds. Fairview’s solution to the ongoing mental health crisis has been equally problematic. The organization entered into a joint venture with for-profit Acadia Healthcare to build a standalone mental health hospital, expected to open later this year.lxxxvi A New York Times investigation later found that Acadia was holding patients against their will in order to maximize insurance payouts.lxxxvii Acadia agreed to pay nearly $20 million in September 2024 and faces a new federal investigation as of October 2024.lxxxviii

“A New York Times investigation later found that Acadia was holding patients against their will in order to maximize insurance payouts.

Deprives the City of Necessary Property Taxes

Once predicted to become the next Chicago, Duluth became a wealthy city during the Gilded Age, driven by iron mining and timber.lxxxix Early on, the city weathered shifts in the economy due to its prominence in manufacturing and transporting steel.xc Industrial decline started to hit Duluth in the mid-twentieth century as the city’s three largest employers, including U.S. Steel, left, taking more than 5,000 jobs. By the early 1980s, the city’s economic prospects were grim. Unemployment hit 13 percent by 1983, and a billboard asked, “will the last one leaving Duluth please turn out the light[?]”xci

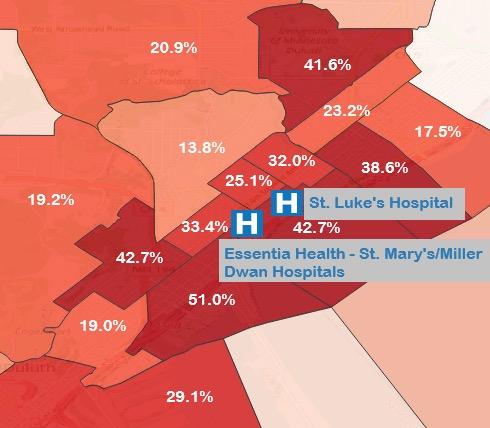

While the city has experienced significant revitalization in recent years, its scars as a Rust Belt city remain. The median household income is $66,263, trailing that of the state as a whole – $87,556.xcii Over seventeen percent of the city’s population lives in poverty.xciii

Today, healthcare, education, and government are Duluth’s primary employers.xciv Essentia Health is the city’s largest employer, comprising more than 16 percent of the city’s total employment.xcv Both Essentia and St. Luke’s, Duluth’s second-largest employer, sit on prime real estate in the Medical District. Essentia’s nearly $1 billion dollar St. Mary’s Hospital opened in the summer of 2023, “offering panoramic views of Lake Superior and the Duluth hillside.”xcvi Yet, as a not-for-profit, Essentia Health is exempt from paying most taxes, including sales and property taxes that fund essential city services. We estimate that Essentia Health and St. Luke’s would have paid the City of Duluth $38.3 million in property taxes over a five-year period had they not been exempt.

Essentia executives have used the health system’s wealth, in part created by tax exemptions, to expand its reach and market share. In 2022, Essentia spent $31 million to acquire the Mid Dakota Clinic, a large multi-specialty independent practice in Bismarck, North Dakota, with an additional $10 million due by October 1, 2025.xcvii Recently, Essentia became a co-owner of Brightside Surgical, an ambulatory

surgery center in Bismarck for an undisclosed price.xcviii Not all of Essentia’s plans have succeeded. The health system was previously in talks with CommonSpirit to acquire CHI St. Alexius Health in Bismarck and other hospitals and facilities in North Dakota and Minnesotaxcix and explored a merger with Wisconsin-based Marshfield Clinic Health System in 2022 and 2023.c In both instances, nurses, other healthcare workers, and community members voiced concerns that a merger would reduce access to patient care in Duluth and other Minnesota communities.ci Essentia later admitted that it called off talks with Marshfield due to their financial challenges,cii news of which was followed nearly immediately by staffing cuts at the Wisconsin-based system.ciii Had the merger gone through, resources may have been diverted from Essentia to prop up the struggling Marshfield.

As Essentia has focused its attention on growth, insufficient tax revenues have had devastating consequences for Duluth’s residents. Citing financial challenges, Duluth Public Schools announced a $5 million deficit for the 2025-2026 school year, the equivalent of 50 full-time teacher positions, which followed $2.6 million in cuts for the 2024-2025 school year.civ Staffing will be reduced by 8 percent, including $1 million at the elementary level, $1.35 million at the secondary level, and $1 million in the special education/care and treatment department.cv

The “casualties” of these cuts – athletics and activities directors, a journalism program, and daily library services – have real-world impacts.cvi

As high school student Tavin Roth, put it, “Without the support available in the library, I would not have been able to succeed in History Day, where I’ve placed at the state tournament every year and have qualified for nationals. By reducing media center staff and cutting the school newspaper, the district is making it clear where it stands on media literacy, which will degrade in the absence of these programs. The ripples of these regressions will be felt by both students and teachers alike.”cvii Similarly, Kate Dean, a school board student representative stated, “If the Duluth Public Schools is committed to focusing on literacy across all content areas, decisions regarding student access to reading and research materials and study spaces do not align with these goals.”cviii

In addition, a decision at the Minnesota Supreme Court recently allowed hospital-affiliated clinics to seek tax-exempt status, significantly reducing the tax revenue from Duluth’s medical district created to support Essentia and St. Luke’s.cix City officials claim they were caught off guard and are now struggling to handle the shortfall in revenue, which they planned to use to retire outstanding debt on a medical district parking ramp. In October, city officials predicted that the parking department would be forced to absorb short-term costs, which, if underfunded, could create a snowball effect, further depriving the city of necessary revenue.cx

Allina Health Challenges Property Taxes While Classifying Them as ‘Community Benefit’

Although Allina Health System is exempt from most taxes, its leadership has chosen to spend resources suing local governments over the minimal property taxes it pays. Between 2018 and 2022, Allina paid $22.6 million in property taxes, which it counts as “community benefit.”cxi However, this is a far cry from the $125.5 million estimated as the value of Allina’s property tax exemption during this period. Court records in the 11-county Twin Cities metropolitan area revealed that Allina filed at least 56 petitions to reduce or eliminate property taxes payable in 20192023, according to our analysis.cxii

“While it is possible that Allina had good reason to believe these properties were incorrectly assessed, this information was not available through the court documents. Three factors raise serious questions for municipalities. First, Allina was found to be engaging in aggressive behavior that was wildly out of step with other Twin Cities and Duluth-based systems. Second, Allina had petitioned for the same properties numerous times. For example, Allina challenged the property tax assessment for its urgent care clinic in Coon Rapids all five years.cxiii Finally, Allina challenged the assessment value of parcels it did not own. Allina successfully reduced the assessment value of parcels in the Midtown Exchange,cxiv which the organization leases portions of as its corporate headquarters.cxv Midtown Exchange Commons LLC, which appears to be an affiliate of developer Ryan Companies, is listed as both the owner and taxpayer per Hennepin County records.cxvi

Charity Care at Twin Cities and Duluth-based Health Systems

Court records in the 11-county Twin Cities metropolitan area revealed that Allina filed at least 56 petitions to reduce or eliminate property taxes payable in 2019 - 2023, according to our analysis.

By some measures Minnesota’s hospitals are among the least generous and community-minded in the country. Minnesota’s hospitals face a lighter burden than almost all other states when it comes to covering the cost of providing charity care and covering bad debt.cxvii According to a March 2024 report by the Medicaid and Chip Payment Access Commission (MACPAC), for FY 2021 only Hawaii hospitals faced a lesser burden of 1.1% of operating expenses, while Minnesota and Pennsylvania ranked second lowest at 1.4% of operating expenses.cxviii Texas hospitals, at the high-end, by comparison, spent 10.2% of operating expenses on charity care and bad debt.cxix

This lack of compassion and concern for poor and working-class Minnesotans is also reflected in the charity care provision by Twin Cities and Duluth-based health systems which in 2022 ranged on the low end from the negligible $1.1 million provided by St. Luke’s and $1.7 million

Source: Analysis of audited financial statements for Fiscal Years 2018-2022

provided by Children’s, to Fairview, which provided $45.5 million on the high end (see Figure 4). Four of the seven systems: Allina, Essentia, North Memorial, and St. Luke’s provided less charity care in 2022 than in 2018, even in nominal, or non-inflation-adjusted, terms. A common method of examining hospital provision of charity care dollars is to examine them in terms of total expenses. Driven to maximize profits, executives at these large health systems have spent less and less on charity care in recent years. In 2018, the Twin City and Duluth-based health systems covered in the report on average provided charity care as a percentage of total expenses at a rate of 0.55 percent, or approximately 1/3rd the national median for not-for-profit hospitals of 1.5 percent of total expenses.cxx In 2022, these systems on average provided charity care at a rate of just 0.41 percent of total expenses despite their flagship campuses being in some of Minnesota’s lowest-income communities (see Appendix B). Unless

transformative steps are taken, medical debts that are “re-set”, as in St. Paul, will quickly re-accumulate. These and other Minnesota health systems have a clear capacity to do much more for Minnesota families struggling with large and often crushing medical bills.

Source: Analysis of audited financial statements for Fiscal Years 2018-2022

The decline in charity care spending is even more significant when looking at historic levels. In 2013, these systems spent on average 0.78 percent of their expenses on charity care, nearly twice the rate a decade later in 2022 (see Figure 6).cxxi This change is most glaring at North Memorial, where charity care spending fell from 1.57 percent of expenses in 2013 to 0.68 percent in 2022 (See Appendix C). These changes may be related to the increasing corporatization of healthcare and the growing influence of the financial sector, as we explored in our 2024 report, Code Blue: How Allina Health’s Financial Ties Compromised its Mission Patient Care and Business.cxxii A 2023 study found that more than half of board members overseeing the nation’s top hospitals have a background in finance or business services.cxxiii

These executives may see charity care as an unwanted and unnecessary expense given their distance from the bedside and the struggling communities hospitals serve.

Figure 6. Charity Care Spending as a Percentage of Total Expenses by Twin Cities and Duluth-based Health Systems 2013 to 2022

Source: Analysis of audited financial statements for Fiscal Years 2013-2022

The following table details the total loss to the public by comparing the total value of tax exemptions for Twin Cities and Duluth-based hospital systems with the amount of charity care they provided for fiscal years 2018 to 2022. Over the five years, the total loss to the public is estimated to be $3.3B. Split out by system, Allina Health System is responsible for the largest shortfall of the group ($820.7M), followed by HealthPartners ($820.4M), and Fairview Health Services ($625.7M). Notably, no health system provided anywhere near as much charity care as the value of their not-for-profit tax exemption (see Figure 6).

Table 5. Total Loss to Public: Charity Care Provided Compared to the Total Value of Tax Exemptions for Fiscal Years 2018 to 2022

Source: See Appendix A – Methodology

Source: See Appendix A – Methodology

The Hospital Industry’s Misleading Claims about Charity Care

The not-for-profit hospital industry in Minnesota and elsewhere would like nothing more than to maintain the status quo in which they remain largely unaccountable to the communities they are supposed to serve. A common industry rejoinder to any news articles or reports underlining a lack of charity care provision is to claim that charity care is just a small and relatively unimportant part of the larger category of “community benefits” they provide that justify their tax-exempt status.cxxiv

Arguments for maintaining not-for-profit hospitals’ tax exemptions, in the absence of increased accountability and transparency, are not well-founded and instead perpetuate harm to the communities hospital executives purport to serve and care for. The American Hospital Association (AHA), the main lobbying organization of not-for-profit hospitals, relies primarily on sleight of hand as its’ first line of defense, by comparing only the cost of the federal tax exemptions to community benefits provided, while completely omitting the well over $20 billion in additional annual costs of the tax exemptions to states and other localities.cxxv At the same time they perform this sleight of hand, they turn around and brazenly accuse those attempting to hold not-for-profit hospitals accountable, such as the Lown Institute, of “cherry-picking” data.cxxvi This example alone demonstrates that the AHA’s accusations of bad faith would be better targeted were they to take a long look in the mirror.

The first thing to know about so-called “Community Benefits” is that half or more of the totals are Medicaid and other mean-tested programrelated shortfalls.cxxvii This was similarly demonstrated in the March 2022 report by the Minnesota Department of Health which found that 53.3% of community benefit dollars went to these shortfalls.cxxviii Before we uncritically accept these shortfalls as a meaningful community benefit, we should consider that the Medicaid shortfall, as the Lown Institute’s Judith Garber and Vikis Saini have pointed out “…isn’t money that goes into the community to improve health, nor does it have a tangible impact on patient’s financial health, the way charity care does.”cxxix Garber and Saini also note that other categories of community benefit spending claimed by hospitals, such as medical education, receive significant funding support from Medicare, which goes largely unacknowledged by hospitals, and that research that is fully federally funded can be reported by hospitals as if it were a community benefit the hospital was solely responsible for funding.cxxx

The AHA, when it comes to the issue of Medicaid shortfalls, is again far from transparent or forthcoming about that fact that the payment shortfalls for caring for low-income Medicaid patients are also absorbed by private for-profit hospitals who care for these patients and at similar rates, and receive no tax exemptions at federal, state, and local levels.cxxxi In other words, the nation’s not-for-profit hospitals are demanding that they continue to be paid (via tax exemption) for something the nation’s for-profit hospitals also provide without the benefits of a tax exemption. And if that was not an ugly enough picture for the tax exemption’s advocates, for-profit hospitals also provide charity care at comparable rates to not-for-profit hospitals.cxxxii

It also turns out that upon closer examination, the much-publicized Medicaid shortfalls are less than meets the eye.cxxxiii Research has found that: “…when Medicaid payments for each Medicaid discharge are added to Medicare payments to disproportionate-share hospitals that are tied to each Medicaid day, Medicaid admissions can be profitable.”cxxxiv

While federal and state disproportionate share allotments for Minnesota were a relatively modest $207.6 million in FY 2024,cxxxv a much more lucrative source of funds has been the controversial 340B Drug Pricing Program many hospitals in Minnesota receive significant revenue from. This federal program allows eligible healthcare providers to purchase prescription medications at discounted prices, with the goal of improving care for low-income and vulnerable populations.cxxxvi While covered entities are not limited in the payments they can charge insurers, there is no requirement to pass discounts along to patients, provide additional safety-net care, or report the savings to the federal government.cxxxvii Reporting by The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, as well as governmental and academic research, has found that savings may not translate to enhanced services or increased charity care spending.cxxxviii Instead, recent investigations have found that large hospital systems benefit financially without delivering the community investments and care needed by those the program was purportedly set up to serve. As researchers Bai, Letchuman, and Hyman explain, “This ‘buy low, sell low’ program has evolved into a ‘buy low, sell high’ program that enables eligible hospitals to generate profits by providing these drugs to well-insured patients.”cxxxix

In 2023, Minnesota became the first state to pass legislation to collect and share data from 340B providers.cxl The initial report, released in November 2024, revealed that Minnesota providers collectively earned at least $630 million in net revenue in 2023 – the difference between the payments they received for discounted drugs and the cost of acquiring those drugs plus administration costs.

Given that most entities failed to report complete data, researchers at the Minnesota Department of Health estimated that this figure may represent as little as half of the actual total 340B revenue in Minnesota.cxli While the MDH study did not shed light on critical questions of how net revenue is spent or the extent to which patients benefit, a Star Tribune analysis found that in the aggregate Hennepin Healthcare, North Memorial, and the University of Minnesota Medical Center received far more in 340B revenue than they spent on charity care.cxlii

Winners and Losers

Over the decades, the accountability-free status quo has allowed not-for-profit hospitals to exploit their rich tax exemptions while doing little more of substance for their communities than their for-profit tax-paying counterparts. This dynamic creates winners and losers, with the losers far outnumbering the winners. Chief among the winners are the nation’s not-for-profit CEOs and top executives who have enjoyed ever greater compensation and rich pay packages. According to one recent study: “From 2005 to 2015, the mean major nonprofit medical center CEO compensation increased from…[$]1.6…million to [$]3.1…million, or a 93% increase…[and t]he wage gap increased from…7:1 to 12:1 with pediatricians, and from 23:1 to 44:1 with registered nurses.”cxliii As noted in Table 4, among the hospital systems covered in this study CEO pay ranks from the high of $3.5 million earned by Fairview CEO James Hereford or a ratio of 55:1 compared to the average Minnesotan, to St. Luke’s Hospital CEO Nicholas Van Deelan who at $1.1 million earns a ratio of 17:1, when compared to the average Minnesotan. Below this top tier lies a large swath of hospital executives who also earn exorbitant salaries. It may be that one of the main results of the tax-exempt status for not-for-profit hospitals is to mint millionaires in the healthcare industry, rather than to provide robust charity care and targeted community investment to improve health outcomes.

Communities in Minnesota’s first class cities, including Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Duluth face the brunt of the negative impacts of taxexempt status because not-for-profit institutions such as hospitals: “…demand government services but unlike other sectors of the economy…provide few resources in return, due to their tax exempt status”cxliv (See Appendices D-E). Homeowners suffer directly from the consequent increased burden of taxation, and renters suffer indirectly as property taxes are passed along to them. Seniors and others living on fixed incomes are also hit hard.

“Homeowners suffer directly from the consequent increased burden of taxation, and renters suffer indirectly as property taxes are passed along to them. Seniors and others living on fixed incomes are also hit hard.

Public schools are also impacted as the tax-paying public must either be obliged to step in to fill shortfalls, or services must be cut. This is because school funding largely comes from state aid (67 percent) supported by taxes (e.g., state income and sales tax) as well as property taxes (20 percent), which not-for-profit hospitals generally do not pay into.cxlv For the 2024-2025 school year, the Association of Metropolitan School Districts projected a budget shortfall of over $300 million in their budget survey.cxlvi St. Paul Public Schools’ eventual cuts totaled nearly $115 million, with another $37 million made up in deficit spending.cxlvii Districts around the state are already preparing rounds of cuts and layoffs for the 2025-26 school year, with Minneapolis Public Schools staring down a $75.5 million deficit.cxlviii As previously mentioned, Duluth

Public Schools announced a $5 million deficit for the 2025-2026 school year, the equivalent of 50 full-time teacher positions, in November 2024, which followed $2.6 million in cuts for the 2024-2025 school year.cxlixHospital Executives Continue to Fail their Communities

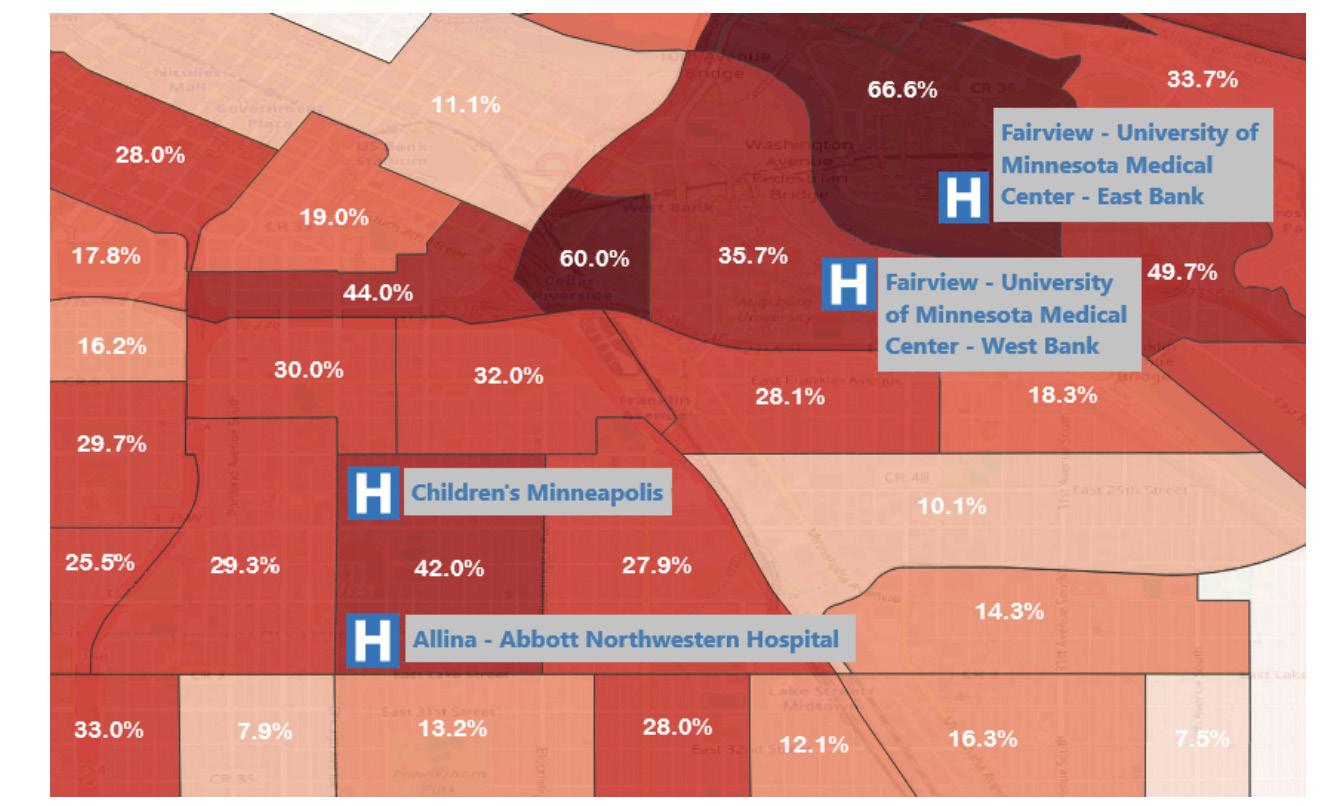

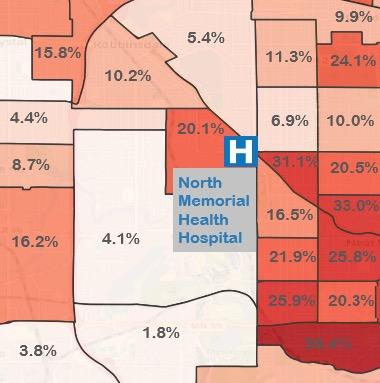

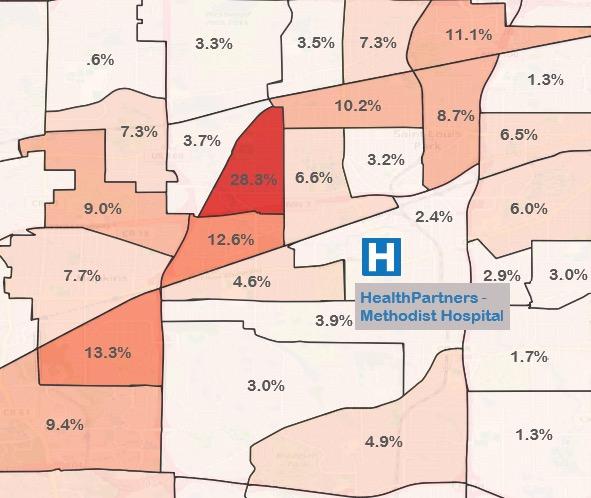

For 2023, Minnesota’s poverty rate of 9.3% was lower than all but two other states.cl As is well-known, this relatively low statewide poverty rate masks deep inequities. In neighborhoods not far from the flagship hospitals of Twin Cities and Duluth-based not-for-profit hospital systems, a very different reality is lived. In Minneapolis not far from Abbott Northwestern, Children’s Hospital Minneapolis, and University of Minnesota Medical Center (UMMC), census tracts can be found where more than 4 in 10 people live in poverty. cli In St. Paul near Regions Hospital and Children’s Hospital St. Paul and in Duluth near Essentia St. Mary’s and St. Luke’s, tracts of concentrated poverty can also be foundclii (See Appendix B). Despite their flagship facilities being in prime locations to serve the less well-off, hospital executives at these systems appear to be at something of a loss when it comes to finding patients in need of charity care. As healthcare has become increasingly profit-driven, not-for-profit hospitals may exacerbate rather than reduce health disparities. According to a recent study, communities most in need received less community benefit spending than more affluent, White communities, both before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.cliii If these hospital executives truly want to engage in work that justifies their rich tax exemptions, ample opportunities should be present for improving the health of these communities through sustained and direct investment.

In Minneapolis not far from Abbott Northwestern, Children’s Hospital Minneapolis, and University of Minnesota Medical Center (UMMC), census tracts can be found where more than 4 in 10 people live in poverty.

Overall life expectancy figures in Minnesota, as was the case with the poverty rate, also mask troubling variation. Minnesota as a whole ranks sixth in life expectancy in the U.S. at 78.8 years.cliv In the very city of Duluth census tract where Essentia St. Mary’s and St. Luke’s hospitals are sited, life expectancy at birth was estimated to be just 66.4 years, a full twelve years less than the statewide figure.clv In St. Paul, nearby to Regents Hospital and Children’s St. Paul, life expectancy was estimated to be an even lower 64.4 years.clvi In Minneapolis, estimated life expectancies as low as 67.2 can be found near Abbott Northwestern, Children’s Hospital Minneapolis, and the University of Minnesota Medical Center (UMMC). While many factors contribute to low life expectancy, medical care has an important role to play,clvii and work must be done to ensure that the flagship hospitals of these systems are doing their part to ensure health, equity, and justice for all.

Communities around the country are waking up to the fact that not-for-profit hospitals do not meaningfully differ from for-profit hospital corporations when it comes to providing charity care and care to those enrolled in Medicaid. Investment in their surrounding communities is what can truly set not-for-profit hospitals apart from their for-profit counterparts and help to justify the continued existence of their taxexempt status.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Minnesotans may be proud of their healthcare, but they should question the large chains that receive millions in tax exemptions every year while exacerbating existing inequalities and undermining care. Even though these chains are organized as “not-for-profits,” many control billions in assets and expend a small fraction of their expenses on charity care, a system allowed to exist by policy failures at every level. A 2023 Lown Institute report found that a majority of private, not-for-profit hospitals in Minnesota had a “fair share deficit,” which they define as receiving more in tax breaks than they spend on “meaningful” community investments.clviii As the authors note, the $712 million annual fair share deficit could pay for all medical debts in the state four times over. As we explore above, insufficient tax revenues have devastating consequences as they reduce the government’s ability to provide essential services, including public health and public education.

The Twin Cities and Duluth-based not-for-profit hospital systems that received at least $3.9 billion in federal, state, and local tax exemptions between 2018 and 2022 can and should do more to improve the communities they claim to serve. Rather than suing patients for medical debt, these systems should be held to meaningful charity care thresholds to qualify for not-for-profit status. Instead of closing facilities or service lines, hospital executives should use their resources to ensure all Minnesotans have access to care in their local communities. Our goal is not to propose that Twin Cities and Duluth-based hospital systems lose their tax exemptions and transition to for-profit status. It is time to stop giving money for nothing; hospital executives must take meaningful action and significantly increase the charity care they provide to the communities they serve. To ensure these efforts do not remain at the discretion of hospital CEOs, policymakers have many options to hold hospitals accountable and to ensure that communities have funding for essential services. We recommend:

Payment In Lieu of Taxes

Though far from a cure-all, in cities such as Boston, MA, New Haven, CT, Providence, RI, Baltimore, MD, and others where not-for-profit hospitals, colleges, and universities dominate the landscape, efforts have been made to get these organizations to make voluntary payments

to their respective cities. These voluntary payments that tax-exempt not-for-profit organizations are asked to make are referred to as Payments in Lieu of Taxation (PILOTs). A 2012 review of PILOTs, found that: “PILOTs have been received by at least 218 localities in at least 28 states since 2000 [and] these payments are collectively worth more than $92 million per year.”clix

In 2017, the Citizens League of St. Paul completed a comprehensive report studying the issue.clx The Committee recommended that the City of St. Paul “initiate discussions with owners of tax-exempt properties in order to design and implement a PILOT initiative for St. Paul”, with the understanding that the initiative would be voluntary.”clxi As part of this process, the Minnesota Hospital Association (MHA) declared its uncategorical opposition to PILOTs, insisting that PILOTS “attempt to circumvent state and federal laws to charitable, nonprofit hospitals and health systems.”clxii In their August 25, 2017 letter to the Citizens League, included in the final report, they cite $131.6 million in Medicaid shortfalls and in excess of $20 million in charity care.clxiii Here again, we see the standard not-for-profit industry practice of bandying about these figures while refusing to acknowledge that for-profit hospitals also face Medicaid shortfalls and provide charity care at the same rate as not-for-profits without receiving favorable tax treatment.

Boston is a leader in efforts to secure payments from its not-for-profit institutions, as well as a number of cultural institutions. As the City of Boston states:

The property tax revenue collected by the City of Boston each year helps to fund important services such as police and fire protection… City services are made available to both taxable property owners and those property owners who are exempt from the property tax. PILOT contributions help to offset the burden placed on Boston taxpayers to fund City services for all property owners.clxiv

(Emphasis added)

Boston requests that not-for-profit institutions owning tax-exempt property valued more than $15 million participate by contributing 25% of what would be paid in property taxes as a for-profit, with at least half of the payment made in cash and up to half of the 25% allowed to be made as a community benefit contribution.clxv

County and municipal governments in Minnesota should pursue similar policies on the condition that community benefits should only be counted if they are meaningful direct investments in community-based health initiatives.

Renegotiating 340B Contracts

The State of Minnesota and local municipalities should seek to renegotiate 340B contracts with healthcare providers to include measurable commitments for charity care spending. By law, private, not-for-profit hospitals seeking to participate in 340B are required to submit a contract with a state or local government to provide healthcare services for low-income individuals not entitled to Medicare or Medicaid. clxvi Unfortunately, as a Minneapolis Office of City Auditor report noted last year, most view the contract as a “box checking” exercise.clxvii Currently, hospitals earn millions in 340B revenue but are not required to pass along the savings to patients, nor do known 340B contracts stipulate a minimum amount of charity care.clxviii Renegotiating the 340B contracts allows the State and local governments to address the needs of their communities and address the limitations of this controversial federal program. Municipalities should also consider explicitly defining income thresholds, requiring covered entities to report the actual amounts of charity care provided, and seeking commitments to provide certain services such as behavioral health.clxix

Establish a Minimum for Charity Care Spending

“Boston requests that not-for-profit institutions owning tax-exempt property valued more than $15 million participate by contributing 25% of what would be paid in property taxes as a for-profit, with at least half of the payment made in cash and up to half of the 25% allowed to be made as a community benefit contribution.

A clear way to increase charity care spending is by mandating a minimum threshold to qualify for not-for-profit status and the resulting benefits (e.g., tax-exempt bond financing and property tax exemption). While no such minimum has existed at the federal level, historically, IRS auditors denied or revoked the not-for-profit status of hospitals if their charity care amounted to less than 5 percent of gross revenues, at least until policy changes were enacted in 1969. clxx Given research has established that, in the aggregate, for-profit hospitals spend 3.8 percent of their total expenses on charity care,clxxi any minimum imposed at the federal or state level should be at a minimum 4 percent of total expenses. Lawmakers may want to adapt existing models created to address overall community benefit spending – at least five states require not-for-profit hospitals to provide community benefits equal or greater in value than their tax exemption or a certain percentage of net revenues – to charity care spending. Policymakers should ensure that the definition of charity care continues to exclude bad debt – debts where there was an expectation of payment at the time of services.clxxii

Reviewing Property Tax Exemptions

Our analysis established that Twin Cities and Duluth-based systems received a property tax exemption worth $620.4 million between 2018 and 2022. Municipalities should carefully review currently exempted properties to ensure compliance with state law. The stakes are high: approximately 20 percent of St. Paul’s properties are tax-exempt, burdening homeowners who are forced to shoulder taxes large not-for-

profit hospitals and universities do not pay.clxxiii Allina’s practice of challenging property tax assessments, coupled with tax records listing owners who no longer exist (e.g., Health One Corporation), suggests that greater scrutiny may be necessary. This approach would not be without precedent. Pittsburgh Mayor Ed Gainey challenged the tax exemption of 104 parcels in 2024, asserting that those properties did not meet the legal requirements of “purely public charities” and belong on the tax rolls.clxxiv According to city officials, the taxes would amount to $6.4 million annually in property tax revenue, as well as another $8.8 million for Pittsburgh Public Schools and libraries.clxxv While success is limited so far, Pittsburgh’s example should inspire municipal governments across the Upper Midwest to take action and ensure their communities are properly funded.

Additional Action by Hospital Executives

Beyond increasing their charity care spending, hospitals should ensure that all patients who qualify for financial assistance receive it, a concern raised in the New York Times’ 2023 investigation into Allina Health.clxxvi So-called “presumptive eligibility” programs are spreading nationally and use data to determine whether a patient qualifies for assistance, without the need for the patient to engage in the lengthy and invasive application process.clxxvii Hennepin Healthcare, owned by the county, instituted presumptive eligibility in 2024; between September and December of that year, the hospital wrote off about $19.5 million in patient debts as presumptive charity.clxxviii These policies work because they remove the “hassle factors” that stop people from applying, like automatic enrollment in retirement plans.clxxix

“In our current political climate, hospitals also need to ensure that all patients feel safe seeking care. As social psychiatrist Eric Reinhart writes, “Hospitals are meant to be sanctuaries — places where people seek care without fear.”clxxx If those without documentation are concerned that seeking care will expose them to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), they may avoid care, which could exacerbate chronic health conditions, lead to increased complications and costly emergency visits, as well as unnecessarily spread infectious diseases. clxxxi Millions of undocumented workers are also essential to the smooth operation of our healthcare system, both in providing direct care to patients and doing the behind-the-scenes work of cleaning patients’ rooms and serving meals.clxxxii Hospital administrators have a moral obligation to protect immigrant patients and workers, regardless of their legal status, to continue to serve their communities and put patients first. Hospitals should publicly commit to protecting patients and workers from ICE and institute training for staff to handle such visits, including maintaining confidentiality of patient information and not allowing authorized personnel in patient care areas without a proper warrant.clxxxiii Hospitals should also build relationships with their surrounding communities, including immigrant rights groups, legal advocates, and government to ensure the public is engaged and aware of the protections in place, and collect feedback on what more needs to be done.

Hospitals are meant to be sanctuaries — places where people seek care without fear.