A Comprehensive Framework for Shaping Exceptional School Culture

Foreword by Anthony Muhammad

Copyright © 2026 by Marzano Resources

Materials appearing here are copyrighted. With one exception, all rights are reserved. Readers may reproduce only those pages marked “Reproducible.” Otherwise, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher and the authors. This book, in whole or in part, may not be included in a large language model, used to train AI, or uploaded into any AI system.

AI outputs featured in the cover generated with the assistance of Photoshop Generative Fill.

AI output featured in figure 3.4 generated with the assistance of ChatGPT.

555 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404

888.849.0851

FAX: 866.801.1447

email: info@MarzanoResources.com

MarzanoResources.com

Visit MarzanoResources.com/reproducibles to download the free reproducibles in this book.

Printed in the United States of America

Names: Acosta, Mario I. author

Title: The schools our students deserve : a comprehensive framework for shaping exceptional school culture / Mario I. Acosta.

Description: Bloomington, IN : Marzano Resources, [2026] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2025005302 (print) | LCCN 2025005303 (ebook) | ISBN 9781943360963 paperback | ISBN 9781943360970 ebook

Subjects: LCSH: School environment | School management and organization | Educational sociology

Classification: LCC LC210 .A26 2026 (print) | LCC LC210 (ebook) | DDC 370.15--dc23/eng/20250611

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2025005302

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2025005303

Production Team

Publisher: Kendra Slayton

Associate Publisher: Todd Brakke

Acquisitions Director: Hilary Goff

Editorial Director: Laurel Hecker

Art Director: Rian Anderson

Managing Editor: Sarah Ludwig

Copy Chief: Jessi Finn

Senior Production Editor: Christine Hood

Copy Editor: Mark Hain

Proofreader: Charlotte Jones

Text and Cover Designer: Fabiana Cochran

Content Development Specialist: Amy Rubenstein

Associate Editor: Elijah Oates

Editorial Assistant: Madison Chartier

I would like to acknowledge Phil Warrick, who has had a profound impact on both my career path and professional life. You have been an incredible mentor who not only taught me how to be an effective leader and shape successful schools, but you have also been an even better friend. I would not have been able to accomplish my career goals without your guidance and support.

I would like to acknowledge Tina Boogren, Robert Marzano, and Julia Simms for their help with the writing process. With this book, I have attempted to follow the lead of these world-class authors. Furthermore, I would like to thank the entire Solution Tree publishing staff for their hard work processing this book.

I would also like to thank my mom, Cindy Acosta, and dad, Mario Acosta, for their love and support. You not only raised me to be a good human but a good educator as well. Having served as teachers, principals, and district leaders, you

have been the most influential role models in my life. To my kids, Karli, Elena, Kai, and Evalina—I love you with all my heart! I want to thank you for being so supportive of me while I spent countless hours writing this book. I have tried to model for you that anything in life is possible with hard work and dedication.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge my wife, Courtney Acosta. You are not only the love of my life and my best friend but also the single greatest educator I have ever had the pleasure of working with. Together, in our journey as educational leaders, we learned the lessons that I have shared in this book. I could not have written this book without you. Thank you for being the best and most supportive colleague, friend, and wife!

Marzano Resources would like to thank the following reviewers:

Lety Amalla

Former Principal

Midland Independent School District

Midland, Texas

Jeffrey Benson

Educational Consultant

Jeffrey Benson, LLC Brookline, Massachusetts

Courtney Burdick

Apprenticeship Mentor Teacher

Spradling Elementary School Fort Smith, Arkansas

Molly Capps

Principal McDeeds Creek Elementary School Southern Pines, North Carolina

Barbara W. Cirigliano

Former Principal

Willow Grove Kindergarten and Early Childhood Center

Buffalo Grove, Illinois

Doug Crowley

Assistant Principal DeForest Area High School DeForest, Wisconsin

Jenna Fanshier

Principal

Marion Elementary School Marion, Kansas

Visit MarzanoResources.com/reproducibles to download the free reproducibles in this book.

Mario I. Acosta, EdD, is an award-winning educator, accomplished author, and highly regarded speaker and consultant. He spent twenty years of his educational career as a teacher, instructional coach, assistant principal, academic director, and principal leading schools with diverse profiles in the state of Texas. He was named the 2022 Texas principal of the year while principal of Westwood High School, a U.S. News & World Report Top 50 campus and member of the High Reliability Schools network.

Acosta has had success in leading schools of all sizes, with students and teachers from a variety of backgrounds, communities, and socioeconomic statuses. He has led school turnarounds in high-poverty schools throughout Texas

at both the middle and high school levels, which yielded immediate and significant growth in student achievement. Further, under his leadership, Westwood High School was recognized as a top 1 percent campus in the United States for academic achievement and college and career readiness.

Acosta is the coauthor of several books, including Five Big Ideas for Leading a High Reliability School with Robert J. Marzano and Phil B. Warrick, and a contributor to the edited volumes Culture Champions: Teachers Supporting a Healthy Classroom Culture, Culture Keepers: Leaders Creating a Healthy School Culture, and Professional Learning Communities at Work and High-Reliability Schools: Cultures of Continuous Learning.

In 2022, Acosta joined the Marzano Resources and Solution Tree teams and works as an author and national presenter. He specializes in campus-level implementation of effective campus culture, High Reliability Schools (HRSs), professional learning communities (PLCs), instructional improvement, response to intervention, effective teaching strategies for English learners, and standardsreferenced reporting. As an HRS certifier, Acosta works with K–12 schools and districts across the United States as they progress through the levels of certification. He also serves as an adjunct professor in the educational leadership master’s program at the University of Texas at Austin.

Acosta earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from the University of Texas at Austin and a master’s degree in educational leadership from Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas. He also holds a doctorate in educational administration from the University of Texas at Austin and a superintendent certification in the state of Texas.

2

To learn more about Mario I. Acosta’s work, follow him @marioacosta31 on X and mario.acosta.902266 on Instagram.

To book Mario I. Acosta for professional development, contact pd@Marzano Resources.com.

When Dr. Acosta approached me about writing the foreword for his new book, I was both honored and thrilled. Upon learning the title of this book, I became fixated on its meaning: The Schools Our Students Deserve. This title affirms that there should be a correlation between students and quality education and that relationship should be viewed as a right for all, not the privilege of some. As I pondered these concepts, I wondered if the social, political, and professional climate of modern society would interpret these concepts in the same way. Sadly, the evidence would say no.

Is there a basis for the claim that students deserve a quality education? The answer would be simply, yes. Horace Mann, who is often referred to as The Father of Public (Common) Schools, sought to actualize a vision in the 1830s

in Massachusetts. That vision included three key components: (1) Every student has the right to attend a local, funded school and be taught a universal academic curriculum to advance the greater good; (2) every classroom should be led by a teacher who is trained in the vocation of teaching to deliver that curriculum; and (3) local boards of education should oversee these institutions to ensure quality at each school under its jurisdiction (Spring, 2022).

The United States has made schooling available to every child and invested billions of dollars, but it has yet to meet the standard of ensuring every student attends the school they deserve. In most cases, we can predict the quality of a student’s educational experience based on factors like race, gender, social class, and disability. This falls far short of Mann’s vision of excellence for all.

In this pursuit, Dr. Acosta leans into the power of an invisible influencer of school quality—its culture. He theorizes that there is a connection between a school’s culture and the quality of the student learning experience. Perhaps, if we could influence the culture of the school, we could influence the quality of student learning. He writes in the introduction:

When a school’s cultural values are in harmony with its goals, the culture itself becomes a catalyst for achievement. It shapes decisions, molds teaching practices, and inspires students. It creates an atmosphere where innovation is not just welcomed but expected, where diversity is not merely accepted but celebrated, and where challenges are viewed not as obstacles but as opportunities for growth. (p. 3)

I have been intrigued by the influence of school culture for more than twenty years. I often wonder why certain practices tend to thrive in one school environment yet flounder in another. This question has driven me to write several books on the topic of school culture in pursuit of fulfilling the vision of Horace Mann. I have discovered that culture is complex because human beings are complex. There is no panacea to creating an ideal culture. Instead, there is a mix of theories and hypotheses that, when woven together, can start to demystify culture and help us collectively walk towards excellence. You can add the name Dr. Mario Acosta to the list of scholars carving out another pathway toward cultural excellence.

At a time when studies tell us that educator morale is at a record low, Dr. Acosta reminds us about the power of our collective influence through professional culture. Nothing influences school quality more than the collective behaviors of adult professionals. This does not excuse the disruptive behaviors

of politicians, parents, and society at large, but no group of people has more influence over creating the schools our students deserve than the educators who dedicate themselves to that pursuit. Things like high expectations, collective optimism, relentless problem solving, and a desire to improve are tools at our disposal. Dr. Acosta challenges us to accept this responsibility and leave no stone unturned in our pursuit of the educational rights of children.

In many ways, this book is a wake-up call to the moral imperative that all educators signed up to pursue. As a child who grew up in a U.S. inner city, I was driven by the idea of being a change agent in creating better school systems for those who are underserved by the current system. Even as a veteran educator of more than thirty years, the cracks of pessimism and despair visit me from time to time, and this book was a wake-up call for me as well.

This book is comprehensive. Dr. Acosta has made the concept of culture more tangible and accessible. He explains its power and influence and provides tools educators can embrace to start the never-ending process of refining their culture. This book is written with a huge level of respect for the scholarship that preceded it but offers solutions that are unique and add value to the literature. This is the book I wish I had in my hands when I started my school leadership journey years ago. You have the opportunity to embrace this scholarship, apply the diagnostic tools, and implement the recommendations found in this book. Will you accept the challenge of producing the school system our students deserve?

At the core of every school is an invisible yet undeniable force—one that breathes life into its classrooms, fuels its ambitions, and ultimately determines its triumphs or struggles. Imagine two schools, nearly identical in student demographics, funding, curricula, and instructional strategies. One is a beacon of success, while the other remains stuck in a cycle of mediocrity. Step into the thriving school: The hallways hum with energy, teachers collaborate with passion, students engage with curiosity, and every decision is anchored in a shared commitment to excellence. Yet just miles away, another school, armed with the same best practices, feels stifled. Administrators impose directives without buy-in, teachers operate in isolation, initiatives fall flat, and students drift through their education disengaged and uninspired. What separates them? It’s not policies, programs, or personnel but something deeper: culture.

Schools are expected to create an environment in which students can thrive academically, socially, and emotionally. The school’s culture has a significant impact on these outcomes. As the embodiment of beliefs, behaviors, and desired outcomes, the culture dictates whether a school truly thrives, merely survives, or even fails. It shapes mindsets and defines the level of commitment to a shared vision. This powerful energy manifests as a dynamic entity born out of the school’s history, directing what is allowed in its present and influencing what it will become in the future. Caring for a school’s culture requires effort from all staff members to perpetuate, mold, and, when necessary, change a school’s culture. All educators must be mindful of the status of their school’s culture to ensure their efforts to improve student outcomes are supported and not thwarted by the culture.

A strong, well-crafted cultural fabric prepares an organization to manage challenges and thrive in better times.

This book unpacks the essence of school culture—how it forms, how it drives or obstructs progress, and most importantly, how educators can intentionally harness it to create schools where both students and staff thrive. Kevin Oakes (2021), an international expert in the field of human capital management, equated culture to a fabric that supports the whole organization. A strong, well-crafted cultural fabric prepares an organization to manage challenges and thrive in better times. If this fabric is weak or damaged, the smallest issues can tear larger holes, affecting everyone in the organization. In schools, a robust culture is crucial for the success and effectiveness of its teachers and students. Thus, the effectiveness of a school’s culture is not merely an indicator but a determinant of its success, influencing outcomes as surely as curricula or pedagogy.

Schools face many challenges from within the educational system as well as increasingly complex societal changes. Educators therefore need to systematically and regularly revisit the status of their school’s culture to align with current and future demands. I aim to provide educators with the knowledge and resources to lead cultural renovation in our ever-changing society. The ideas I present will guide educators through identifying their school’s current culture to implementing the cultural evolution required to meet the demands of educational environments.

Defining and translating school culture into tangible reform actions can be complex. My goal is to simplify the concept so schools can understand and

mobilize their culture in a manner that supports reform efforts and best practices. I make the case that culture represents the collective beliefs and behaviors that form the foundation of an institution’s identity. This discussion takes place within the framework proposed by university professors and culture researchers Terrence E. Deal and Kent D. Peterson (2016), who defined school culture as a school’s unwritten rules and traditions, customs, and expectations. These elements, often unspoken and invisible, serve as the compass to navigate the educational journey and direct the “daily dance” of interactions, decisions, and practices that occur within school walls.

In the narrative of a school’s journey, its culture is both the compass and the terrain over which it travels. It is not just a backdrop but an active participant, influencing every step toward the school’s ambitions. Leveraging this potent force requires a deep dive into the character of the school, understanding that everyone’s contributions are more than isolated inputs: They are the vital threads that weave together the fabric of the educational community. An effective school culture is a dynamic entity, evolving with the times while retaining its core identity. It is the silent yet powerful engine that drives the school toward excellence.

When a school’s cultural values are in harmony with its goals, the culture itself becomes a catalyst for achievement. It shapes decisions, molds teaching practices, and inspires students. It creates an atmosphere where innovation is not just welcomed but expected, where diversity is not merely accepted but celebrated, and where challenges are viewed not as obstacles but as opportunities for growth.

Consider a high school that sets the goal of increasing student engagement through personalized learning. The school’s existing cultural values emphasize innovation, flexibility, and student ownership of learning. Teachers work collaboratively to develop differentiated instruction, and students have voice and choice in their learning pathways. Because the culture’s values align with the goal, initiatives like competency-based grading and flexible scheduling are met with enthusiasm, and the school sees a rise in student achievement and motivation.

When the existing school culture is out of step with the school’s strategic direction, it becomes necessary to stretch the culture to expand its boundaries gently but firmly. Consider a district that mandates all middle schools transition

When the existing school culture is out of step with the school’s strategic direction, it becomes necessary to stretch the culture to expand its boundaries gently but firmly.

to project-based learning to enhance critical thinking and problem solving. However, the current school culture values strict adherence to pacing guides, standardized tests, and teacher-centered instruction. Leaders must skillfully create momentum for these changes by simultaneously honoring the school’s current values while introducing new practices in a way that allows teachers to feel safe and supported as they grow into the new practices.

This stretching requires leaders who are not only skillful in guiding change but also deeply respectful of the existing cultural values. These leaders must collaborate with staff, drawing on the collective wisdom and energy of students, parents, staff, and teachers. Together, they must navigate the delicate process of transformation, seeding new practices and beliefs without uprooting the core identity that gives the school its unique character.

The goal is to foster an adaptive, supportive, and forwardthinking culture.

Educators must weave the individual threads of experience, belief, and behavior into a cohesive cultural fabric that can support and withstand change. This calls for a collective effort to distill and refine the school’s shared beliefs, aligning them with a vision that speaks to every member of the school community. The goal is to foster an adaptive, supportive, and forward-thinking culture that not only reflects the school’s heritage but also its potential, ultimately resulting in a school environment that ensures the success of each individual student. When such a culture is actualized, the burden that educators carry is lightened. A healthy school culture, in essence, increases the school’s effectiveness, staff morale, and professional cohesion. When educators work in such an environment, doing the job feels better and is easier to do well.

Fortunately, a wealth of educational research and proven practices provide clear guidance for schools working to shape a more hopeful future. Robert Marzano, Phillip Warrick, and Julia Simms (2014) developed a framework of effective school reform called High Reliability Schools (HRSs), which emphasizes five key elements.

1. A safe, supportive, and collaborative culture

2. Effective teaching in every classroom

3. A guaranteed and viable curriculum

4. A standards-based approach to tracking and reporting student progress

5. The use of competency-based educational practices

These five elements are not just theoretical ideals—they are fundamental conditions that schools must implement and measure to ensure educational success for all students.

In addition to the HRS elements that guide effective school practice, consider the important best practices Richard DuFour and Robert Eaker (1998) offered in Professional Learning Communities at Work: Best Practices for Enhancing Student Achievement. To achieve learning for all students, DuFour and Eaker (1998) declared that schools must work collaboratively as professional learning communities (PLCs) using three big ideas.

1. A focus on learning

2. A collaborative culture

3. A results orientation

Schools thrive when teachers collaborate on a shared objective of enhancing student learning.

Integrating HRS with PLC concepts offers a comprehensive approach for enhancing school performance. HRSs offer a tiered framework of conditions essential for school effectiveness and continuous improvement. Schools sustain these conditions when they follow the PLC strategies of collaborative professional development and continuous improvement, all with a focus on the success of every student. Together, HRSs and PLCs create a robust system in which trust, teaching excellence, and student-centric decision making are at the forefront. This union leverages the best practices from research and practical implementations, illustrating that schools that commit to these principles often witness substantial improvements in student learning.

HRSs and PLCs offer schools an approach to ensuring positive student outcomes; however, the congruence of a school’s culture with the principles of HRSs and PLCs becomes not just beneficial but required for success. When aligned with the foundational elements of the HRS and PLC literature, school culture has the power to bolster educational outcomes.

Author and thought leader Anthony Muhammad (2024) asserted, “The fundamental purpose of a school is to improve learning for students” (p. 104). Therefore, sculpting an environment where educators’ belief systems and the school’s cultural framework are in sync with these principles is essential. Such

alignment is key for overcoming present educational struggles and for realizing the full academic potential of each student. To weather the storm of educational tribulations and to truly enhance the academic potential of each student, a school must commit to a culture that is in concert with these essential HRS and PLC tenets of school reform.

I wrote this book to support educators in working together to ensure their school’s culture aligns with its aspirational goals and outcomes. Teachers and staff members must actively partner with school leaders in fostering a successful school culture. Likewise, school leaders must understand and support teachers in manifesting effective classroom cultures. Fostering an effective school culture is critical to ensuring successful outcomes for each student. This book guides educators through tangible action steps to engage in their school’s culture, understand its nuances, and shape it deliberately. Throughout this book, we journey to the core of what constitutes school culture, unraveling its intricacies and charting a path toward its reinforcement and, if necessary, revitalization.

Each chapter is designed to create a cohesive and comprehensive practitioner’s guide. My intent is to ensure that the school’s cultural compass aligns with its reform efforts, focusing on student success that endures and testifying to the transformative power of a culture that is nurtured and strategically leveraged.

Chapter 1 establishes the foundational understanding of school culture, explaining its powerful influence on decision making, teacher-student interactions, and school priorities. It explores culture as the unwritten rules that dictate success or failure within schools. You will gain an understanding of how culture shapes behavior, why mutual respect alongside measurable results is important, and how school leaders can leverage culture to create a highperforming environment.

Chapter 2 explores the role of vision in shaping and sustaining school culture. It examines how clearly defined core values, beliefs, and an envisioned future align a school’s current actions with its purpose. The chapter provides practical strategies for articulating and reinforcing a shared vision, ensuring that cultural beliefs remain in harmony with educational goals. It also offers best practices for embedding cultural values into hiring decisions and providing meaningful onboarding experiences.

Chapter 3 discusses how schools can refine and adjust aspects of their culture without dismantling their foundational strengths. Through the culture stretch process, educators learn to identify necessary behavioral shifts, leverage subcultures to drive change, and implement leadership strategies to ensure new practices take root. The chapter highlights how strong cultures embrace change while preserving their core identity.

An effective culture is sustained by a healthy school climate. Chapter 4 examines the key factors that shape school climate, including trust, communication, validation, and staff wellness. It discusses how a positive climate fosters collaboration, reduces burnout, and enhances both recruitment and retention.

The core focus of an effective school culture is student success and family involvement. Chapter 5 outlines the conditions necessary to foster student achievement, including high expectations, trauma-informed practices, student motivation, and evidence-based teaching. Additionally, it highlights how family and community engagement strengthen school culture, ensuring students receive holistic support.

The book concludes with an appendix containing a collection of tools designed to help schools and school leaders move from insight to action. These practical resources include audits, diagnostic surveys, and mapping frameworks that support everything from culture identification to climate evaluation and organizational network analysis. Each tool is research-informed and field-tested, offering clear pathways for translating values into behavior and uncovering the hidden dynamics within a school community.

I invite teachers, staff, administrators, and policymakers to join in the vital mission of fostering a school culture that supports highly effective learning environments within schools that students rightly deserve. This book is not just a call to action for a cultural revolution in schools; it is also a profound recognition of the urgent need to recalibrate and cultivate a stronger, more resilient school culture that addresses the challenges of today’s educational realities and builds the expectation of excellence, equity, and enduring success within schools and districts to ensure success for the students we serve.

When a school’s cultural values align with its objectives, the culture itself drives success. However, when the culture is misaligned and needs to change for the good of the school, the staff, or its students, the success of the change initiative lies in the effectiveness of the school’s leaders and cultural caretakers. Research on successful organizations in both the educational and corporate sectors identifies the importance and complexity of establishing cultures that are willing to adapt and change practice as needed, while simultaneously being strong enough to hold to their core ideology (Costanza, Blacksmith, Coats, Severt, & DeCostanza, 2016; Kelly, 2018; Vargas-Halabi & Yagüe-Perales, 2024).

A willingness to embrace change is an important characteristic of an effective culture. According to Oakes (2021), “High-performance organizations are more likely to say change is normal, and in fact employees in these organizations describe regular change as an opportunity to boost productivity” (p. 17). Thus, cultivating a supportive, values-driven school culture is not a peripheral task but a strategic imperative that lays the groundwork for sustainable change, driving both individual and organizational transformation. Schools and districts must take intentional steps to ensure that their culture supports its members to respond effectively when change in practice is needed.

A willingness to embrace change is an important characteristic of an effective culture.

This chapter provides actions schools and districts can take to improve specific aspects of their culture, avoiding the common misconception that the culture can be changed holistically. The second component of the School Culture Framework— behavior alignment for change—describes the importance of understanding that changing school culture is accomplished by identifying specific aspects of the culture that need renovation as opposed to attempting a demolition of the entire culture.

According to Oakes (2021), companies that effectively changed their cultures were successful because they were renovating what they had, respecting their past and their core values, and not starting from scratch and completely rebuilding or transforming. Reinforcing this idea, Gruenert and Whitaker (2015) wrote the following:

When pursuing cultural change, leaders shouldn’t consider changing the culture entirely—even in the most toxic school cultures, some aspects are probably functioning quite well. School leaders need to understand the specific aspects of the culture that are interfering with the school’s goals. (pp. 108–109)

Even in the case of unhealthy, misaligned cultures, the research supports the notion that change must occur by impacting strategic slices of improvement instead of attempting to impact the whole organization all at once (Ashby, 1999).

This chapter provides a step-by-step process for supporting schools through effective culture change using the culture stretch process. This process reshapes the cultural boundaries by identifying areas of school culture that need improvement and aligning specific behaviors of individual staff and influential subcultures to the needed change. This process supports schools and districts through cultural renovation by providing concrete actions in leveraging the strengths of their current culture while also adjusting aspects in need of renovation.

Figure 3.1 shows how behavioral alignment for change fits into the overall School Culture Framework.

Shared Vision creates clarity on the core ideology of the school, focusing on the success of every student.

Behavior Alignment for Change focuses on how educators’ behaviors impact performance; implements effective change processes when needed; and models, measures, and celebrates educators whose mindsets align with desired behaviors.

School Climate provides people with a positive work environment centered around trust, communication, validation, growth, safety, wellness, collaboration, and autonomy; staff have the resources, support, and desire to meet personal and school goals.

Student Success and Family and Community Engagement place these goals at the center of reform efforts.

Foundation: An equal focus on mutual respect and a results orientation.

3.1: School Culture Framework—Behavior alignment for change

This chapter highlights the following urgent actions for educators.

• Confront potential negative contemporary challenges and their impact on the pre-existing culture.

• Support employee behavior alignment by providing clear expectations and consistent modeling of desired cultural shifts.

• Apply performance-value assessments to understand where staff members stand in both outcomes and alignment.

• Understand culture’s dual role in change—both in culture and of culture—to prioritize change initiatives while effectively leveraging the guardian to support necessary change.

• Identify areas in need of cultural refinement and engage in the cultural stretching process to change or improve.

• Leverage the role of effective leadership to facilitate cultural stretch by supporting school educators through the process.

• Promote distributed leadership by empowering others to influence culture change through shared responsibility and trust.

Unfortunately, the 21st century educational landscape is beset by an array of complex and interconnected challenges that impact every facet of the school experience. These challenges are not just systemic; they exert a significant influence on the personal and professional ideologies and practices of educators. The prevailing difficulties reshape educators’ beliefs about their roles and the nature of teaching. Additionally, the strain of adapting to these multifaceted pressures has tangible effects on educators’ behavior, leading to changes in classroom management, instructional methods, and even the ways they interact with students and colleagues.

Let’s revisit the definition of school culture proposed in chapter 1 (page 12):

The school’s culture encompasses beliefs and behaviors that are cultivated over time, honored by tradition, and validated by the shared experiences of educators, students, and the community alike. It reflects the school’s character and is a blueprint of its values, a defender of its present self, and a guide to its future. It is this character that creates the boundaries of safety, normalcy, and esteem for its members.

As a living, breathing entity, school culture is profoundly impacted by belief and behavior changes caused by the difficulties resulting from societal and global events.

Given the depth of challenges that schools face, educators must consider the impact that these changes have on the health of their school culture to ensure the culture’s willingness to address the challenges it faces. Let us consider the following urgent issues challenging schools: mental health and wellness, the widening achievement gap, state and federal accountability, political polarization, demographic changes, declining attendance, rapid technological advancements, and staffing shortages.

Schools are confronting a mental health crisis among students and staff. Anxiety, depression, and stress have become commonplace, affecting individuals and the educational process itself. In 2024, Compass Health Center reported that 42 percent of teens experience persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, and 14 percent of LGBTQ teenagers attempted suicide, including one in five transgender and nonbinary youth. Furthermore, youth mental health hospitalizations increased by 124 percent since 2016.

Behavioral issues in students have intensified. These issues are often linked to, or exacerbate, mental health concerns, which in turn affect classroom dynamics and learning outcomes (Division of Adolescent and School Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2023). According to Madeline Will (2023), the Merrimack College and EdWeek Research Center found that 57 percent of teachers reported that students’ mental health and wellness issues were having a negative impact on academic learning, and 53 percent responded that these issues were negatively impacting classroom management.

The ongoing achievement gap, referring to the disparity in academic performance between groups of students, is a persistent and familiar challenge for schools. As evidence of this achievement gap, we look to the U.S. Department of Education: Office for Civil Rights (2023) 2020–2021 data collection report, which found the following.

• Students have limited access to advanced mathematics, science, and computer science courses, particularly in schools with high enrollments of Black and Latino students.

• There are disparities in disciplinary actions in public preschools, with Black children being suspended at nearly twice their rate of enrollment, and boys representing a disproportionately high percentage of those receiving suspensions or expulsions.

• Black students, American Indian or Alaska Native students, and students with disabilities are overrepresented in justice facilities compared to their overall student enrollment percentages.

• A considerable number of students attend schools where less than half of the teachers meet all state certification requirements, with most of these students being Black and Latino.

High-poverty schools experience the highest rates of teacher turnover, which affects the continuity of education and contributes to the perpetuation of the socioeconomic achievement gap (Bradley, 2022). Additionally, the National Center for Education Statistics (2023) reported that, on average, 36 percent of students were behind grade level in at least one academic subject by the end of the year. This figure highlights the educational disruptions that have disproportionately affected students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, further emphasizing the need for targeted interventions and resources to bridge the educational divide.

Despite decades of efforts to close the gap, disparities persist. In fact, the gap widened further due to the disproportionate impact the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic had on non-White students and students from low-income households. The achievement gap continues to have profound implications for students, educators, schools, and communities.

In an attempt to support schools with these learning gaps, state and federal governments have increased accountability pressures to aim for educational improvement, which often place undue stress on schools (Munyan-Penney, Jones, & Levitan, 2024). Emulating the efficiency and outcome orientation of businesses, state and federal accountability systems put pressure on schools to value quantifiable results over educational richness and diversity. The emphasis on standardized testing as a measure of school quality is one such example, where a narrow focus on test scores can marginalize other aspects of learning that are less measurable but no less important, such as critical thinking, creativity, and emotional development.

When schools become overly focused on narrowly defined outcomes, they may also overlook the importance of fostering an inclusive, supportive school culture that can cater to the emotional and social well-being of students. The pressure to perform can also lead to a culture of fear and stress rather than one of inspiration and growth. For educators, the additional administrative burdens of complying with these systems can detract from the time and energy they must devote to teaching and mentoring students.

School systems and educators in the United States are also navigating a highly polarized political landscape that deeply influences educational discourse and classroom dynamics. Heightened political polarization has increased pressure on educators to maintain neutrality, particularly on issues such as racial and social justice, which are intrinsically linked to education.

This has led to a challenging environment for teachers who strive to address these topics in their classrooms, often fearing backlash from administrators or parents for stepping away from perceived neutrality (Walker, 2018). These pressures are forcing educators to confront and often combat misinformation and politicized narratives to continue providing a comprehensive and inclusive education. Against this backdrop of political pressures, schools must not merely aspire to equity and excellence but actualize them.

In 2023 and 2024, U.S. schools faced significant challenges due to demographic changes, particularly concerning students from migrant families. Schools had to rapidly adapt to the needs of these students, many of whom come from low-income backgrounds and do not speak English. The influx has required schools to expand programs for English learners, increase class sizes, and, in some cases, hire more teachers and faculty to manage the additional students and their unique needs (Whelan, 2024).

According to the Migration Policy Institute, 2023 saw a historic high of 2.5 million migrants at the U.S. border (Putzel-Kavanaugh & Ruiz Soto, 2023). It then follows that the rise in migrant student populations across the United States has highlighted the urgent need for educational systems to accommodate learners from diverse backgrounds. With educational systems already under pressure, teachers and administrators must navigate new challenges, including providing tailored language, mental health, and educational services.

Compounding the demographic shifts are declining student attendance rates, symptomatic of deeper systemic problems and often a precursor to academic disengagement. According to a 2022 federal data analysis conducted by Attendance Works (2023), two out of three schools in the United States had high chronic absenteeism (defined as a student missing 10 percent or more school days), which was up from 25 percent in 2019. Further, the report explained that in eleven states, more than one in four students were chronically absent. Additionally, “kindergarten enrollment remained down 5.2% in the 2022–2023 school year compared with

the 2019–2020 school year, according to an Associated Press analysis of state-level data. Public school enrollment across all grades fell by 2.2%” (Mumphrey, Lurye, & Stavely, 2023).

These attendance issues raise red flags about students’ well-being, family dynamics, and the overall school experience. The impact of these changes is deep, with schools facing enrollment declines due to population aging and lower birth rates. This trend poses unique challenges to the financial stability and educational quality of school districts, compelling them to rethink their resource allocation and instructional designs to address varied student needs (Cook, 2023). These demographic shifts, enrollment declines, changes in family characteristics, and rising popularity of different educational formats such as virtual schools are reshaping the cultural composition of schools.

Simultaneously, rapid technological advancements, especially in artificial intelligence and ed tech tools, are transforming educational delivery and content. The integration of these technologies not only alters how students learn but also demands that educators adapt their teaching methods rapidly to effectively engage this new generation of learners. Educators are at the front line, needing to quickly shift their strategies to accommodate these seismic changes in student demographics and technological integration. This requires an adaptive mindset and a willingness to engage in continuous professional development to remain effective in their roles.

At the writing of this book, school districts find themselves in an acute staffing crisis. Staff turnover has become a revolving door in many districts, with burnout and dissatisfaction driving educators away, leaving schools struggling to maintain continuity and quality. A 2023 survey conducted by the RAND Corporation found that 56 percent of K–12 public school teachers reported symptoms of burnout, while 58 percent of teachers in public schools reported experiencing frequent job-related stress (Diliberti, Steiner, Kaufman, Woo, & Schwartz, 2023).

According to 2023 data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES, 2023), the statistical center of the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES), 86 percent of American K–12 public schools faced difficulties in recruiting teachers for the 2023–2024 academic year. Additionally, 83 percent of these schools are experiencing obstacles in filling nonteaching roles, such as classroom aides, transportation staff, and mental health professionals (Nuland & Ewaida, 2023). This widespread educator shortage is leaving crucial gaps in the educational framework and placing additional strain on the remaining staff.

Leadership within schools is also facing its own hurdles, with inexperience at the helm sometimes leading to missteps in navigating these complex issues. According to 2022 data from the Superintendent Research Project, 49 percent of the five hundred largest school districts have faced superintendent changes since March 2020 (Ward, 2023). Experience in principalship is also dwindling, with over 20 percent of principals not returning after the 2022 school year (Ward, 2023). The lack of seasoned leaders can result in a deficiency in mentorship and support for both new and established teachers, undermining efforts to create a cohesive, effective educational environment.

Schools must confront these challenges and understand how they are affected by the multitude of evolving issues. This demands that schools be proactive in acknowledging and addressing the impacts these challenges have had on their school cultures, incorporating strategies to support educators and students alike. A deliberate and thoughtful reshaping of school culture is therefore not only strategic but also necessary to empower schools to rise above these challenges and ensure every staff member and student thrives. The status quo can no longer stand!

The simple fact is that the only way to change outcomes for students is for educators to modify their behaviors in ways that will positively impact students.

School systems frequently focus improvement efforts in areas such as standardized testing, attendance rates, and graduation rates, but DuFour and Marzano (2011) asserted that school improvement begins with people improvement. Challenging the status quo in schools begins with a review and revision of educator behavior. School accountability systems force schools to focus on goal planning, goal accomplishment, exceeding performance expectations, missing performance expectations, and so on. Unfortunately, schools are not asked to address the human-centered elements of the workplace. Values, behaviors, and employee experience are seldom monitored and even more rarely measured (Edmonds & Babbitt, 2021). The simple fact is that the only way to change outcomes for students is for educators to modify their behaviors in ways that will positively impact students.

Consider the following logic statement: School culture influences educator behavior; educator behavior determines strategy implementation; strategy implementation

drives student outcomes. The implementation of any strategy requires all employees to both accept and commit to a common course of action (Kaplan & Norton, 2001). Behaviors aligned with effective school culture contribute significantly to creating an environment conducive to student success. Put simply, educator behavior ultimately determines the effectiveness of schools.

Research indicates that when teachers are engaged and actively participating in the school’s vision, student outcomes improve (Goddard, Goddard, Kim, & Miller, 2015). For educators to align their behavior with the school’s culture, they must understand that their daily behavior should be informed by the content of the school’s written vision, encompassing both its values and envisioned future. Schools can support this alignment by pairing individual performance expectations with school values (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2003). Effectively aligned cultures are characterized by institutionalized systems (particularly measurement systems) that implicitly and explicitly direct the intentions and efforts of all involved (Ehrhart et al., 2014).

Put simply, educator behavior ultimately determines the effectiveness of schools.

Organizations should create robust measurement processes that assess faculty and staff behavior in relation to the institution’s written values. This alignment between values and behaviors can be monitored using metrics that track goal attainment as well as the degree faculty and staff embody the school’s core values in their day-to-day interactions (Dolan, Garcia, & Richley, 2006). For example, a school that prioritizes inclusivity might develop measures that evaluate how teachers foster an inclusive classroom environment or how administrators create policies that support diverse learners. These behavior-based evaluations allow schools to ensure their values are more than just words on paper but instead, become actionable standards that guide everyday practices.

By implementing systems that align staff behavior with organizational values, schools can foster a more consistent and intentional culture that contributes directly to their overarching educational goals. This alignment not only enhances school performance but also creates a more cohesive and motivating environment for educators and students alike. The following scenario provides a tangible example of how a school could measure educator behavior alignment to school values.

Consider a school whose core values include inclusivity, growth, and accountability. To ensure these values are consistently upheld, the school creates specific metrics and behaviors for teachers and administrators that align with these values, as table 3.1 (page 84) shows.

TABLE 3.1: Example Value-Behavior Metrics

Example Core Values

Example Behavior Metrics

Inclusivity Teachers are evaluated on how they foster inclusive classrooms. This could involve using tools like student surveys and peer observations to assess whether each teacher encourages diverse perspectives and creates an environment where all students feel valued. Administrators, in turn, might be evaluated based on policies they implement to support diverse learners, such as ensuring accessibility in classrooms or adapting curricula to address different cultural backgrounds. Regular feedback and reflection sessions allow educators to see how their daily interactions align with the school’s inclusion goals.

Growth To promote growth as a core value, the school might implement professional development goals tied to specific educational techniques or subject matter expertise. Teachers could track and discuss their progress in regular one-on-one meetings with mentors, focusing on both student achievement and self-improvement in their teaching practices.

Accountability To ensure accountability, the school could introduce a system in which both teachers and administrators set quarterly goals aligned with the school’s strategic objectives. Progress toward these goals is tracked through clear metrics, such as improvements in student engagement or achievement in classrooms. By incorporating accountability into behavior evaluations, the school promotes transparency and personal responsibility, encouraging all educators to align with school values in their actions.

By using these structured, value-aligned measures, the school ensures its values are not just aspirational but actively embodied in everyday practice. This approach aligns individual efforts with the school’s vision, which enhances both educator engagement and overall school performance (Kuntz, Malinen, & Näswall, 2017). Organizational theorist Karl E. Weick (1985) argued that it is difficult to distinguish strategy from culture in successful organizations, explaining that strategy is what the organization wants to do, and culture is the process by which it can happen. When strategy and culture align, they are indistinguishable. To create such alignment between strategy and culture, schools must build processes that assess faculty and staff behavior in relation to the written values of the institution, considering both performance and values when measuring success.

While traditional performance evaluations often focus solely on meeting jobrelated tasks and goals, they frequently overlook the critical component of values alignment. Leaders must have a structured approach to assess not only what employees achieve but also how they achieve it.

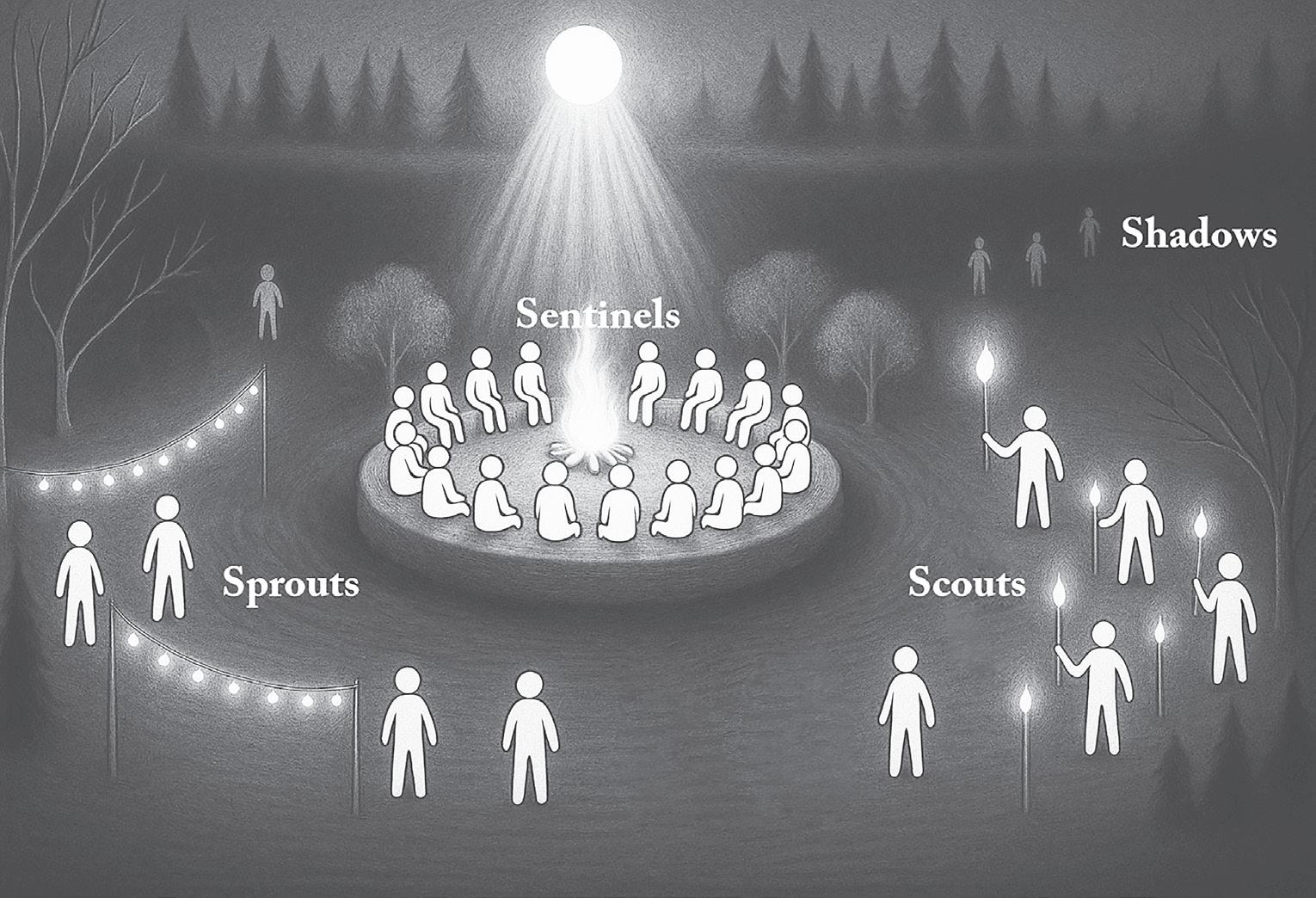

The performance-value matrix in figure 3.2 is a powerful tool designed to monitor and measure employee alignment in both performance and adherence to core values. It provides leaders with a visual framework to evaluate how well individuals are performing in their roles while also assessing their alignment with the organization’s core values. Each of the four quadrants shows a distinct combination of high or low performance and high or low values match, providing a comprehensive overview of employee behavior.

High Performance

Low Performance

Sentinels (low values match, high performance): Sentinels demonstrate strong performance, have a deep understanding of the culture’s history, and prioritize preserving established practices, resisting changes that deviate from cultural traditions.

Shadows (low values match, low performance): Shadows include employees with weak cultural alignment and low performance, often feeling disconnected or disenfranchised.

Source: Adapted from Edmonds & Babbitt, 2021.

FIGURE 3.2: Performance-value matrix

Scouts (high values match, high performance): Scouts exceed performance standards, align strongly with the school’s values, and are forward thinkers who embrace change and improvement.

Sprouts (high values match, low performance: Sprouts align with the school’s values but may lack the skills or confidence to lead change.

Effective use of this tool requires that expectations for both performance and values are explicitly defined, communicated, and agreed on. As discussed in chapter 2 (page 34), when all systems within a school align with its core values, a cohesive and focused environment conducive to achieving educational goals develops. Schools can consistently gauge team member behavior using the matrix, gaining valuable insights into who is excelling, who may need additional support, and who might be better suited for a different role. This approach ensures a balanced focus on both results and cultural fit, which is essential for fostering high-performing, values-driven schools.

The categories of employee alignment and performance in the performance-value matrix from figure 3.2 illustrate distinct types of employee roles, each with unique strengths and challenges within an organizational culture. Each quadrant of the performance-value matrix, which I describe in detail in the following section, has practical applications in school environments, where varying levels of alignment and skill influence both individual and collective performance.

1. High values match–high performance (scouts): These employees and subcultures exceed performance standards and align strongly with the organization’s values. Scouts model the defined values and desired

behaviors (Edmonds & Babbitt, 2021). Scouts are forward thinkers who embrace change and improvement, often acting as early adopters without needing encouragement. In a school setting, scouts could be innovative teachers who adopt and champion new teaching methods, influencing others by example. They actively seek professional development and continuously improve their skills, creating an environment of growth for both students and peers. Research shows that employees with high engagement and high competence, like scouts, tend to foster continuous improvement (Kwon, Jeong, Park, & Yoon, 2024).

2. Low values match–high performance (sentinels): Sentinels have a deep understanding of the culture’s history and prioritize preserving established practices. These individuals and subcultures demonstrate strong performance but resist changes that deviate from cultural traditions. In schools, these employees might be senior teachers who ensure that traditional methods remain integral to teaching practices. They act as custodians of the school’s cultural guardian, standing watch to oversee cultural continuity, maintaining stability and making sure changes align with the school’s historical identity. Unfortunately, sentinels may resist new approaches, fearing they might disrupt the proven methods. They understand in the present what actions align with the developed culture, and they review all efforts to ensure that the future of the culture remains aligned with its past self. Studies on employee conservatism indicate that sentinels contribute stability but may require context and training to understand why changes are beneficial (Hurtz & Donovan, 2000).

3. High values match–low performance (sprouts): These employees and subcultures align with the organization’s values but may lack the skills or confidence to lead change. Sprouts in a school might be teachers who support new teaching strategies but lack the expertise to fully implement them independently. They are open to influence and may follow more confident peers if given the proper guidance and skillbuilding opportunities. Sprouts can be swayed to follow the scouts to new practices, but they can also be recruited by the sentinels to help maintain the status quo. New staff members are often in this category. Onboarding programs must take this fact into account consistently and provide mentoring and teaming with scouts. This category has the highest potential for growth since sprouts require skill development rather than cultural alignment (Criss, Konrad, Alber-Morgan, & Brock, 2024).

4. Low values match–low performance (shadows): Shadows include employees with weak cultural alignment and low performance; they often feel disconnected or disenfranchised. In schools, shadows might be those struggling with both instructional methods and value alignment, impacting their ability to engage students effectively. These employees can be challenging to integrate, as their lack of motivation and skills can negatively affect school performance. High levels of support and directive guidance are crucial for this group, as they often need both skills training and cultural alignment to become more effective contributors (Forson, Ofosu-Dwamena, Opoku, & Adjavon, 2021).

In every school or district, staff behaviors tend to align with these four key patterns. Sentinels guard the status quo, scouts lead the way forward, sprouts show promise and growth, and shadows remain disconnected or ineffective. Recognizing these patterns helps leaders develop specific strategies to tailor their support, build momentum, and move the school or district forward strategically and effectively with clarity and purpose.

The Neosho School District in Neosho, Missouri, uses the performance-value matrix (refer to figure 3.2, page 85) to structure support for staff and align coaching with the four different quadrants of the matrix. The school district leaders have used this approach to provide strategic and targeted action plans to ensure that all educators receive targeted support based on their performance-value needs (N. Manley, personal communication, October 15, 2024).

Figure 3.3 shows the performance-value action plan Neosho School District’s leaders use to support employees.

Support:

• Give permission and eliminate barriers to the desired changes.

• Create pathways for success while actively providing support.

• Provide personal validation and specific affirmation.

• Provide opportunities for collaborative grouping.

• Support when stressed; provide tools when needed.

• Offer active listening and walk alongside them.

Leadership:

• Encourage employees to bring their thoughts to the table.

• Offer self-reflection discussions.

• Provide leadership positions and invest in professional development opportunities for growth.

• Place a “carrot” before employees as a goal.

• Leverage influence.

• Recognize difficulties and challenges of the lead teacher position among colleagues.

3.3: Neosho School District performance-value action plan continued

Celebrate:

• Build up employees’ leadership desires.

• Promote self-confidence.

• Recognize qualities that make employees shine.

Modeling:

• Offer the following: + Peer coaching + Action research + Passion projects

Clarifying vision:

• Identify what is best for students and stretch their perspective.

• Create a timeline for check-in.

• Co-create goals and accountability measures.

• Focus on the why; also use support from an instructional coach.

• Limit influence (last resort).

Coaching:

• Ensure culturally aligned commitments.

• Review critical considerations.

• Mentor and demonstrate what is expected and how it’s done.

• Focus on effective student management.

• Direct clear conversations.

• Assign tasks to create behavior that eventually changes belief.

Values:

• Promote positivity in all situations.

• Provide more value-based professional development.

Collaboration:

• Build relationships within the PLC team.

• Team with people who value collaboration and strategic grouping.

• Plant seeds and allow them to arrive at their own “aha” moments.

• Provide video lessons.

• Come with solutions.

Immediate victories:

• Provide small, challenging tasks.

• Counteract impostor syndrome by assuring and empowering.

Coaching, connection cycles, toolbox:

• Focus on effective student management.

• Help with data analysis and next-best action steps.

• Provide instructional coach support and professional development.

• Observe and mentor scout teachers.

• Build strong, collaborative relationships.

• Offer clear, specific feedback.

• Celebrate!

Clarify next steps:

• Coach with effective instructional elements and professional development.

• Seek to understand employees’ needs.

• Encourage observations.

• Motivate, empower, and celebrate.

Hire well:

• Identify necessary skills to be effective in your district.

• Provide support and coaching.

• Offer mentorship with scout teacher.

• Call references to explore employee’s value alignment with your district.

Low

Coaching:

• Implement a personal improvement plan with clear timelines for goals and check-ins.

• Collaborate with scouts.

• Conduct peer observations and walkthroughs.

• Provide professional development.

• Coach with consistent instructional rounds.

• Provide clearly written expectations.

• Assume good intentions.

• Clarify skill set to be developed.

• Focus on effective student management.

Clear values:

• Broadcast happiness and do not allow toxicity to spread (limit influence to system).

• Start with values over performance.

• Have intentional conversations about teaching and learning.

• Set goals with focused and specific feedback.

• Clarify building goals and cultural alignment

Celebrate:

• Highlight positive experiences.

Team impact:

• Prioritize team building.

• Have hard conversations.

• Examine model classroom video and reflect on instruction.

• Complete personality type quizzes.

Source: © 2024 by Neosho School District. Adapted with permission.

Understanding the staff performance-value alignment is a necessary precursor to implementing culture change. By measuring employee performance and value alignment, the change process will leverage the abilities and beliefs of specific sets of employees as catalysts for change.

A school’s culture is the most influential and impactful variable when change is needed. The success or failure of a change effort depends on whether the change is supported by the existing cultural guardian. Therefore, schools engaging in reform or improvement efforts must have clarity regarding the alignment (or misalignment) of the proposed reform with their existing culture. When reform or change efforts align with the school’s culture, faculty and staff are likely to accept the proposed change strategies and align their practices with the changes. In this case, the culture itself is a catalyst for, and a champion of, the change needed. Conversely, if

the proposed changes do not align with the current culture, faculty and staff will likely resist adjusting their practices to the changes. The culture becomes a barrier to change, perceiving the change as a threat to its core identity. Understanding the alignment of employee behavior with change represents the first and potentially most important strategic decision in the change process.

As previously discussed in chapter 2 (page 34), the cultural guardian serves two main purposes: (1) protecting the organization and (2) resisting change. The guardian may find change difficult because it often perceives it as a threat to its established way of functioning. The unpredictability of the future forces the cultural guardian to confront the tension between tradition and progress.

To successfully overcome the cultural guardian’s propensity to resist change, schools must avoid the urge to thrust changes onto the entire culture and, instead, learn to leverage individuals and subcultures (specifically scouts and sprouts) who are willing to engage in the proposed changes. Once willing members of the culture have adopted and refined the changes, they can then become the influencers who lead the change process with the remaining staff. School leaders play a crucial role initiating and facilitating this change process through identifying, supporting, and celebrating the individuals and subcultures who adopt change while simultaneously challenging members who oppose it.

To successfully overcome the cultural guardian’s propensity to resist change, schools must avoid the urge to thrust changes onto the entire culture.

When a change effort in an organization fails, the cause of the failure can regularly be traced to the cultural guardian not supporting the change. Muhammad (2018) elaborated on this phenomenon, asserting that structural changes not supported by cultural change will always be overwhelmed by the existing culture. This cultural phenomenon creates a binary condition for schools and districts to consider. Either the proposed change is currently supported by the culture or it is not.

Whether the culture supports change requires leaders to understand that the change strategy is either first-order change or second-order change. First-order change involves small, manageable improvements within existing structures, while second-order change requires deep, transformative shifts in values, strategy, and operations (Bate, 1994). This distinction is crucial for understanding how organizations adapt to change, as first-order changes are often easier to implement but may not lead to significant transformation, whereas second-order changes can lead to profound organizational evolution but are more challenging to execute (Greenwood, & Hinings, 2023).

Figure 3.4 illustrates the roles that sentinels, scouts, sprouts, and shadows often play in the change process, as well as in adaptive or transformative change. Schools should first determine whether the proposed change is adaptive, first-order change that safely lies within the light, warmth, and order of the current culture’s boundaries (representing change in culture), or if the proposed change is transformative, second-order change that lies in the unknown danger of the darkness not currently protected by the cultural boundaries (representing change of culture).

Kelsey Miller (2020) described these change conditions as adaptive change versus transformational change. Adaptive changes are small, incremental, first-order changes in culture, supported by the cultural guardian and adopted to address the culture’s needs over time. Transformational changes of culture involve major second-order shifts in strategy, structure, performance, and process and represent mindsets and behaviors that exist outside of the guardian’s current cultural boundaries.

When change is needed in schools, understanding the type of change becomes the first step for school and district leaders. The determination as to whether the existing cultural guardian will support or resist the needed change will govern the outcomes of the change process. Consider the following two examples in figure 3.5 (page 92).

Adaptive Change in Culture: Aligned With School’s Culture

• At Oakwood Middle School, the school culture is centered around collaboration, student-centered learning, and continuous improvement. The administration proposes a new initiative to introduce project-based learning, which allows students to work in groups, solve real-world problems, and showcase their work to the community. Since the staff already values teamwork, hands-on learning, and student engagement, the proposal is well received.

• Teachers enthusiastically embrace the change, aligning it with their shared belief that students learn best through active participation and collaboration. The implementation goes smoothly. The faculty accept professional development eagerly and work together to adjust their lesson plans and share strategies, making the transition seamless and successful.

Transformational Change of Culture: Not Aligned With School’s Culture

• At Maple Grove High School, the culture has a long history of strongly emphasizing standardized testing and lecture-based instruction. The administration proposes a shift to a more flexible, student-led learning model where students have greater autonomy in shaping their learning paths.

• However, most of the staff are uncomfortable with the idea, viewing it as too radical and out of step with the school’s focus on rigor and structure. Despite training sessions and meetings, teachers resist the change, questioning how it fits with the school’s longstanding values.

FIGURE 3.5: Adaptive and transformative change examples

These examples illustrate the point that adaptive changes that align with the cultural guardian will be more readily accepted, and implementation will spread throughout the school quickly and effectively. Transformational change will take time and strategic focus and requires creating buy-in from the guardian before these changes are accepted and supported.

When engaging in reform, schools should consider first implementing adaptive changes. However, schools and school leaders should not accept that they cannot implement critical transformational changes. When the guardian resists change, schools must employ a strategic approach aimed at stretching the school’s culture to adopt the necessary behaviors needed to support transformational change. The goal of cultural stretch is to expand the culture’s boundaries of light and safety to encompass the needed changes, allowing the culture to adopt the change into the light of its safety. The following sections explore strategies that support the change process in either condition.

During adaptive change, “the focus is on evolutionary growth (more of the same, but better) with the aim of retaining and building on those established values, traditions, and working practices that have served the organization well over a period of years” (Mannion, 2022, p. 33). In the case of adaptive change, the school or district’s cultural values align with change goals and actions, and the culture itself becomes a catalyst for achievement. The guardian will support the aligned changes

by rallying the collective efforts and skills of its members to embrace the necessary changes, ensuring successful outcomes for both staff and students. When change aligns with the existing culture, school leaders would do well to proceed with schoolwide implementation. However, even aligned change needs a thoughtful approach to ensure it is executed effectively. The process for such a change would focus on communication, empowerment, building momentum, and leveraging the existing cultural strengths. When leaders identify the need for changes accepted by the guardian, they should apply the change process featured in figure 3.6.

Steps

1. Assess current alignment. Begin by clearly identifying how the proposed change aligns with the organization’s cultural values and norms.

2. Communicate the change. Communicate the change in a way that reinforces its alignment with the culture, reducing resistance.

• Conduct a quick review of the organization’s vision and core values to confirm the alignment.

• Engage in discussions with key stakeholders, like leadership teams and cultural guardians, to ensure the proposed change is truly aligned with the current culture.

• Frame the change as an enhancement or natural extension of the existing values.

• Throughout the entire change process, use storytelling to show how the change supports the organization’s long-standing practices and norms.

• Throughout the entire change process, use both formal communication (memos, meetings) and informal communication channels (hallway conversations, staff huddles) to reinforce the message.

The change results in a clear statement outlining the alignment between the change and the organization’s culture crafted in collaboration with key stakeholders and formal leaders.

The change results in constant communication regarding the change throughout the change process. The change is presented not as something new or disruptive but as a reinforcement of what already exists.

3. Empower stakeholders to lead.

Engage cultural sentinels and key influencers (scouts) within the organization to be champions of the change.

• Identify staff who are enthusiastic about the change and have a good reputation within the culture. Empower these individuals to lead discussions, workshops, or feedback sessions on the change.

• Offer leadership opportunities for employees to take ownership of aspects of the change, ensuring buy-in at all levels.

The change results in a distributed leadership model where staff members feel ownership of the change.

FIGURE 3.6: Adaptive change process—Aligned with the cultural guardian continued

4. Leverage existing practices and rituals. Build momentum by embedding the change into existing routines and practices.

5. Provide tools and resources. Ensure employees have the resources they need to support the change.

• Identify current processes, meetings, or traditions in which the change can be incorporated.

• If the organization already has regular check-ins, team meetings, or professional development sessions, use these to reinforce the aligned change.

• Celebrate existing behaviors that exemplify the change.

• Provide training or development courses that focus on how the change can be executed.

• Make sure staff have access to the tools or systems that make the change easy to implement.

• Offer continuous support, such as question-and-answer sessions or office hours, where employees can come and seek advice about incorporating the change.

The change becomes naturally embedded into the existing fabric of the organization.

Employees feel equipped and confident in making the aligned change work.

6. Monitor and adjust as needed. Track the progress of the change to ensure it stays aligned and on track.

7. Celebrate and recognize progress. Celebrate successes that reinforce the aligned culture and the change.

• Use informal check-ins and pulse surveys to get feedback from staff about how the change is being integrated.

• Be flexible and willing to make small adjustments based on this feedback. Since the change is aligned with the culture, any resistance should be minimal, but monitoring will allow for quick troubleshooting.

• Set clear benchmarks or indicators to measure the success of the change.

• Publicly recognize individuals or teams who have successfully implemented the change in a way that aligns with the organization’s values.

• Use both formal celebrations (awards, recognition at staff meetings) and informal acknowledgments (thank-you emails, personal notes).

• Tie the celebration to the organization’s broader cultural values to reinforce how the change aligns with those values.

Staff have a clear understanding of the change’s effectiveness, along with the ability to quickly pivot if necessary.

Staff maintain the momentum and view the change as a success.

8. Sustain the change with continuous feedback. Ensure that the change becomes part of the longterm culture.

• Throughout the entire change process, set up regular feedback loops where employees can provide their thoughts on how the change is working in practice.

• Continuously relate the change back to the organization’s core values to maintain alignment.

• Encourage leadership to model the change through their behavior and language, showing that the change is not a onetime event but a continuous effort.

Example Prompts for Leaders to Use in Discussions:

• How does this change reflect the core values we’ve always had?

• How can we use our current practices to make this change feel natural?

• In what ways can we empower staff to take ownership of this change?

• What resources or tools do we need to ensure the success of this change?

The change is not only implemented but also sustained as part of the organization’s long-term culture.

Source: Adapted from Hubbart, 2023; Kotter & Schlesinger, 1979; van Dijk & van Dick, 2009.

Visit MarzanoResources.com/reproducibles for a free reproducible version of this figure.