CLASS OF THE

UNITS FOR TEACHING MOTIVATION , PERSEVERANCE , COMMUNICATION , AND COLLABORATION IN THE SECONDARY CLASSROOM

UNITS FOR TEACHING MOTIVATION , PERSEVERANCE , COMMUNICATION , AND COLLABORATION IN THE SECONDARY CLASSROOM

UNITS FOR TEACHING MOTIVATION , PERSEVERANCE , COMMUNICATION , AND COLLABORATION IN THE SECONDARY CLASSROOM

Maureen CHAPMAN

James SIMONS

Copyright © 2026 by Solution Tree Press

Materials appearing here are copyrighted. With one exception, all rights are reserved. Readers may reproduce only those pages marked “Reproducible.” Otherwise, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher. This book, in whole or in part, may not be included in a large language model, used to train AI, or uploaded into any AI system.

555 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 47404

800.733.6786 (toll free) / 812.336.7700

FAX: 812.336.7790

email: info@SolutionTree.com SolutionTree.com

Visit go.SolutionTree.com/studentengagement to download the free reproducibles in this book. Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Chapman, Maureen (Educator) author | Simons, James (Educator) author

Title: Leaders of the class : units for teaching motivation, perseverance, com munication, and collaboration in the secondary classroom / Maureen Chapman, James Simons.

Description: Bloomington, IN : Solution Tree Press, [2026] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2025002610 (print) | LCCN 2025002611 (ebook) | ISBN 9781962188166 paperback | ISBN 9781962188173 ebook

Subjects: LCSH: Leadership--Study and teaching (Secondary)

Classification: LCC HM1261 .C447 2026 (print) | LCC HM1261 (ebook)

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2025002610

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2025002611

Solution Tree

Cameron L. Rains, CEO

Edmund M. Ackerman, President

Solution Tree Press

Publisher: Kendra Slayton

Associate Publisher: Todd Brakke

Acquisitions Director: Hilary Goff

Editorial Director: Laurel Hecker

Art Director: Rian Anderson

Managing Editor: Sarah Ludwig

Copy Chief: Jessi Finn

Senior Production Editor: Tonya Maddox Cupp

Copy Editor: Jessica Starr

Proofreader: Anne Marie Watkins

Cover Designer: Rian Anderson

Text Designer: Kelsey Hoover

Content Development Specialist: Amy Rubenstein

Associate Editor: Elijah Oates

Editorial Assistant: Madison Chartier

The hand-drawn interior artwork in this book comes from art created in 2024 and 2025 by artists Julia Lipovsky and Jon Flannery.

To students: in particular, to my three little leaders—Errol, Cecilia, and Sadie. Daddy and I love you to the moon and the stars.

To educators: in particular, to my parents, who taught me along with countless others. I am grateful for how you saw me as a leader.

To families: in particular, to my loving partner, Thomas, and my siblings, Elaine, Jimmy, Sharon, Phyllis, Alex, and Julia. I am spoiled.

—Maureen

To my parents, for their love, belief, and support. To Jen, my lifelong travel companion, who has accompanied me and encouraged me on every adventure. To Audrey, Hazel, and Alistair for the joy and inspiration they bring to me. And to Clark, because the kids would kill me if I didn’t also mention Clark.

—James

We are grateful for all the incredible educators and students who have inspired us over the years.

We owe a particular debt of gratitude to the following people: our beloved cor creative partners team—Sarah Riemens, Andrew Rocca, and Zane Ranney—who have iterated these tools with us along the way; the educational leaders who have partnered with us, particularly Mary Goslin, Theresa Hirschauer, Rob Zimmerman, Sarah Herman, Tobey Eugenio, Jeff Lane, Troy Norman, Jill Herwig, Teri Fleming, Maria Enrique, Katelyn Fitzgerald, Cari Perchase, and Denny Conklin; the amazing educators at Cincinnati Country Day School and Our Sisters’ School; all of the generous educators who have shared resources with us, including Kristina Wilson, Ian Campbell, Jen Papillo, Kristin Montville, Phyllis Williamson, and Bob Simons; fellow consultants who have warmly accepted us into their communities, including Lori Cohen, Elisa MacDonald, and Krista Leh; Jill Scott for sharing her expertise and resources on emotions while spreading her own pleasant emotions; Tyler Post, who believed in us and encouraged us back when cor was just a harebrained idea; our editors, Hilary Goff and Tonya Maddox Cupp, for their unwavering support and expertise; Julia Lipovsky and Jon Flannery for lending their visual expertise to advance the messages of this book; and finally, everyone who believed in us as leaders along the way.

Solution Tree Press would like to thank the following reviewers:

Zachary Ashauer

Social Sciences Teacher

Hortonville Area School District

Hortonville, Wisconsin

Jessica Bassler

English Teacher

Francis Howell High School

St. Charles, Missouri

Taylor Bronowicz

Mathematics Teacher

Albertville City School District

Albertville, Alabama

Erin Fedina

Supervisor of Mathematics, Science, and Gifted Education

Howell Township Public Schools

Howell, New Jersey

Kelly Limberis

Teacher

McDeeds Creek Elementary School

Southern Pines, North Carolina

Visit go.SolutionTree.com/studentengagement to download the free reproducibles in this book.

Maureen Chapman loves school, and she always has. As a child, she dreamed about becoming an educator. As a middle school student at Thomas G. Pullen K–8 Creative and Performing Arts School in Prince George’s County, Maryland, young Maureen proudly described her future role as spreading her joy for learning to her students.

Maureen continues to pursue this vision of a world in which everyone loves school as much as she does. Maureen is the cofounder and codirector of cor creative partners, a professional development company that supports leadership development for all stakeholders in the K–12 education system. Their cor(e) values are connection, creativity, curiosity, equity, and excellence.

At cor, Maureen supports educators in aligning their work to their own mission and values. She provides instructional and leadership coaching and facilitates workshops and programs. She acts as a strategic partner and cheerleader in the codification and creation of systems that foster a love of school. Additionally, Maureen provides thought leadership through speaking and writing engagements.

Maureen is a lifelong educator who taught for fifteen years in elementary, middle, and high school classrooms before spending eight years in school leadership. As a curriculum director and the head of an instructional leadership team, Maureen oversaw professional development, curriculum, resources, student

data, instructional coaching, new teacher induction, accountability, and career education.

Maureen holds a bachelor of science in elementary education from the Boston University Wheelock College of Education and Human Development. James Simons loves school. Always has. Always will. When James and his colleague, Maureen Chapman, founded cor creative partners, they committed to spreading this love by ensuring that every learner in every classroom experiences meaningful, grade-appropriate academic challenge; relationshipsbased psychological safety; and ongoing opportunities to build the motivation, perseverance, communication, and collaboration skills needed for success and well-being.

In his current role, James works with educators in diverse schools and districts, developing in-depth strategic partnerships, providing leadership and instructional coaching, and facilitating team- and school-level professional learning. James’s areas of passion include supporting leadership development for adults and adolescents as well as all aspects of curriculum design and pedagogy.

When James is not in schools collaborating with fellow educators, he contributes to a community of thought leaders by speaking at conferences across the United States, producing videos, and writing for various outlets. These include Inside Higher Ed, Edutopia, and of

course, Solution Tree Press. Back in middle school, James dreamed of becoming either a writer or an educator. Thus, it is a dream come true to now write about education.

James has a bachelor of arts from McGill University, a bachelor of education from the University of Western Ontario, and a master of arts from the University of

Massachusetts Boston. Throughout his many years in school, he has been told that he is a pleasure to have in class.

To book Maureen Chapman or James Simons for professional development, contact pd@SolutionTree.com.

We hate to give you an assignment on the first page, but as longtime educators, we can’t help it.

Take a piece of paper and write, A leader is someone who . . .

Next, set a timer for three minutes and record as many endings to this sentence as you can.

Try the same exercise with your collaborative curricular or grade-level team.

Now, do it with your students.

What did you learn?

We have conducted this brainstorm with secondary school leaders, teachers, students, and caregivers across diverse school settings. We also have taken a few field trips and talked with individuals at organizations— including Harvard Business School, Marvel Studios, IBM, and the United States Air Force—in order to learn about leadership beyond the school walls. Finally,

we have reflected on our own leadership experiences as students; classroom teachers; school administrators; and designers of professional learning experiences supporting school leaders, instructors, and students to reach their own potential as leaders.

Based on our research and reflection, we have learned four main things.

1. Leaders motivate: They regularly reflect on their identities and emotions, setting meaningful goals they are motivated to achieve.

2. Leaders persevere: When they inevitably encounter resistance en route to their goals, they maintain momentum by experimenting with perseverance strategies.

3. Leaders communicate: They authentically and adaptively exchange feedback that promotes motivation and perseverance for themselves and others.

4. Leaders collaborate: As team members, they individually and collectively reflect and set goals, experiment with strategies, exchange feedback, and advocate for themselves and others.

In the pages that follow, we offer secondary educators a practical guide for teaching all students these critical

leadership competencies. To do so, we start with an introductory Launch unit, followed by four sequential units focused on fostering the student skills required to motivate, persevere, communicate, and collaborate. Each of the four core units introduces one of the following foundational leadership practices.

1. Reflect and set goals.

2. Experiment with strategies.

3. Exchange feedback.

4. Advocate for self and others.

These practices both benefit from and contribute to a classroom culture characterized by four foundational leadership conditions.

1. Motivating work

2. Leadership opportunities

3. Safety to take risks

Belief in self and others

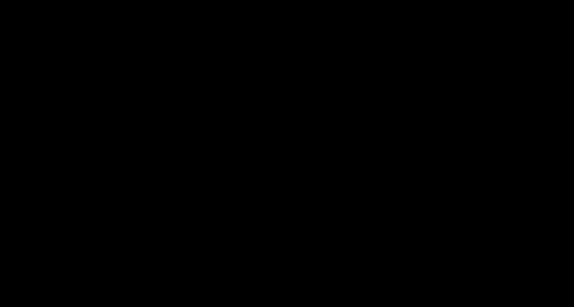

After exploring these elements in the Launch unit, learners collectively focus on a different condition paired with a specific practice in each subsequent unit. As students engage in these leadership practices, they build their individual leadership skills and collectively create the conditions of a leadership culture. What’s more, they develop their own identities as leaders. To document this development, learners work throughout the year on creating a leader profile. You can see a model of this culminating task, based on James’s experiences as a junior in high school, in figure I.1.

We encourage educators to pair our framework’s practical, replicable routines with their preexisting subjectspecific units. After all, the lessons of leadership surface in every academic endeavor, whether we are discussing the self-awareness, self-regulation, creativity, and critical-thinking skills that rigorous work requires or the communication and collaboration competencies needed for positive, productive group work.

We also encourage educators to practice what they teach. Just as a mathematics instructor might complete a few examples in preparation for class, the leadership teacher will benefit from strengthening their own emotional competencies and social skills as they support students to do the same. In your class, you are the lead learner, and since the lesson is leadership, you also are the lead leader.

As you prepare to practice and teach discrete leadership skills, it is helpful to internalize the framework that undergirds your work. For this reason, we have laid out the target competency, practice, and condition for each unit. We also included suggestions about when in the school year to teach each unit. However, no one knows your curriculum, your students, and your context as well as you do, so adapt any elements of this yearlong sequence to meet your unique objectives as an educator.

• Launch Unit (Weeks One and Two): Students reflect on leadership competencies, practices, and conditions. In the process, they preview the units that follow and familiarize themselves with the culminating leader profile, which they

Name:

James

Elements of identity (values, interests, group membership, beliefs, experiences):

What is my heart goal in this course?

Build my skills to become an author

What motivates me to achieve this goal?

You only live once. I want to soak up every experience + turn it into art because I believe that life is meaningful + beautiful.

Grade:

What is my perseverance goal?

EDIT MORE before SUBMITTING!!

What are my perseverance strengths and strategies?

Strengths: I am drawn to language. I Iearn song lyrics and poems easily, and I notice ways to improve my own writing when I prioritize it.

Strategies:

1. Read it out loud.

2. Take a break + then return.

3. Keep telling myself: “Every work needs to be bad before it can be good , and it needs to be good before it can be GREAT!”

What is my communication goal?

1. TALK less

2. Ask more ?uestions!

3. LISTEN!

What are my communication strengths and strategies?

I am a leader in (class)

Strengths: I never have trouble finding things to say. I just need to think of questions to ask instead of statements. I’m pretty curious when I’m interested in stuff, and English is interesting.

Strategies

1. wait for 3 people to talk before me

2. ½ of all my contributions = ?s to peers

What is my collaboration goal?

help my peers w/ their writing

What are my collaboration strengths and strategies?

Strengths: I get along with my classmates. I’ve always made friends with people in different social groups because I find common ground, and I’m nice.

Strategies

1. Ask specific questions (“How could you make this more concise?”)

2. DON’T just write it myself b/c I like writing + (think) I’m good at it

Figure I.1: Model leader profile, front page.

will incrementally build through the year. The primary areas of focus in this unit are as follows.

» Leadership competencies —Motivate, persevere, communicate, and collaborate

» Leadership practices —Reflect

» Leadership conditions —Motivating work, leadership opportunities, safety to take risks, and belief in self and others

• Motivate Unit (Months One and Two): Students activate self-awareness skills, reflecting on their identities and emotions to understand what motivates them. They set academic goals that they are motivated to achieve. Finally, they share their goals and motivations with each other, strengthening their relationships and inspiring each other in the process.

» Leadership competency —Motivate

» Leadership practice —Reflect and set goals

» Leadership condition —Motivating work

• Persevere Unit (Months Three and Four): Students reflect on the resistance they experience in pursuit of their goals. They then co-construct a bank of perseverance strategies, experiment with these strategies, and reflect on the results. Through this ongoing cycle of reflection and experimentation, leaders maintain momentum toward their goals.

» Leadership competency —Persevere

» Leadership practice —Experiment with strategies

» Leadership condition —Leadership opportunities

• Communicate Unit (Months Five and Six): Students continue to reflect, set goals, and experiment with strategies, only now, they apply these fundamental leadership practices to their work as communicators. Learners endeavor to equitably contribute to class discussions and effectively engage in the third foundational leadership practice of exchanging feedback. At the unit’s end, each leader delivers a presentation about their communication goals and motivations as well as the key strategies they use to leverage strengths, overcome struggles, and maintain momentum toward their communication goals.

» Leadership competency —Communicate

» Leadership practice —Exchange feedback

» Leadership condition —Safety to take risks

• Collaborate Unit (Months Seven, Eight, and Nine): Students apply the foundational leadership practices—reflect and set goals,

experiment with strategies, exchange feedback, and a new one: advocate for self and others—to their academic collaboration. In the process, they contribute to a positive and productive collaborative culture that enables everyone on their teams to achieve their leadership potential.

» Leadership competency —Collaborate

» Leadership practice —Advocate for self and others

» Leadership condition —Belief in self and others

As you preview the framework, we hope that you feel inspired by its promise of every student becoming a leader of the class.

Think about your academic curriculum and spend five minutes jotting down responses to the following question.

What would it look, sound, and feel like if every single student demonstrated motivation, perseverance, communication, and collaboration while engaging in the work of your discipline?

This book is a love letter

It is a love letter to teachers and students, written with the understanding that we are all teachers, and we are all students, with tremendous leadership potential. It is also a love letter to school, written in the hope that all teachers and all students will love school as much as we do.

That’s right: We love school. Always have.

Growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, we were surrounded by “Stay in School” sloganeering. Clearly, we took this ever-present advice to heart. For most of our lives, we have stayed in school—as students, as teachers, and as school leaders. No matter how old we grow, every September, we slide into our squeaky-clean new sneakers, clutch our lunch boxes, and happily head back to school.

Now, think of your students. Take five minutes to reflect on the following questions.

Who do you believe already identifies as a leader?

Who already demonstrates the leadership skills of motivation, perseverance, communication, and collaboration?

Who is left?

We are writing this book for all students and for all adults who support them. And especially, we are writing this book for those who are left.

Since 2022, we have worked in schools as coaches and consultants leading a company, cor creative partners, that provides professional development to fellow educators. Maureen, a longtime Latin teacher, pitched our company’s first name, cor, which is Latin for heart

It is a privilege to say that we love school. And it is because of privilege, in part, that we developed this love.

Growing up, we were neurotypical, able-bodied, cisgender, and white. We were raised speaking English by educator parents who instilled in us a belief that we belonged in school . We studied in strong school

systems, learned from plenty of teachers who looked like us, and benefited from enough financial stability that we could focus on books instead of bills.

We were hard workers, high achievers, and pleasures to have in class.

As our academic competence grew, so did our confidence. This increased confidence, in turn, sparked greater competence, pushing us closer and closer to our potential as learners and leaders. It inflated our love for school, like a heart-shaped balloon that bopped behind us as we pulled it from assignment to assignment, class to class, and grade to grade. Figure I.2 demonstrates how the mutually reinforcing relationship between confidence and competence sparks one’s ever-increasing growth toward their enormous potential.

Only later, as classroom teachers and school leaders, did we understand how deflating school could feel for others. Take Sam. At all times, a six-foot radius separated Sam from other students. You would think that he had been sprayed by a skunk. Then, there was Ella.

She could get into a staring contest with a blank page that could last an entire class period.

And, of course, there were countless anonymous students who carved their feelings into desks and bathroom stalls. As an English teacher, James loved reading students’ writing and learning to identify each individual’s unique ideas and handwriting, some hastily jotted in jolts of inspiration and others meticulously printed on pulpy paper like a royal edict chiseled into marble. When James became the dean of students, he continued to read student writing—only then that writing appeared on cafeteria tables and bathroom walls.

“This school sucks.”

“This place is the worst.”

“Mr. Simons is a . . .”

We won’t finish that last one, but you get the picture. James encountered anonymous expressions of agony and anger everywhere. The surfaces were screaming, and somehow, we weren’t hearing.

Leo Tolstoy (1878/2014) once wrote, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” (p. 1). The same goes for unhappy students. All of us who love school feel a sense of belonging, possibility, and pride in our growth and accomplishments. But there are countless reasons we may not love school.

Despite the diversity of individuals’ experiences, there are trends that inevitably arise. As we have moved from school to school in our coaching and consulting work, we have learned that one’s likelihood of loving school is often proportional to their privilege, but it doesn’t have to be.

Take Cincinnati Country Day School (n.d.), an inclusive independent school in Ohio’s affluent Indian Hill suburb with the aim to create “leaders who, through the discovery of their own abilities, kindle the potential of others and better a dynamic world.” In support of this impressive mission, we have partnered with the school on a multiyear project. As part of this project, we collaborate with a faculty group to design and pilot tools for teaching leadership skills in students’ middle school classes.

Cincinnati Country Day School is a place of plenty, with excellence on display from the facilities to the faculty. Such an abundant educational environment enables what Helene Hodges (2001) once termed a pedagogy of plenty in which students learn cognitive and metacognitive processes while engaging in meaningful, relevant, and complex performance tasks. Indeed, when we visit Cincinnati Country Day School, we see students reflecting and setting goals, experimenting with strategies, exchanging academic feedback, and advocating for themselves and others.

In short, we see students leading.

Now, let’s take Our Sisters’ School. It is a tuitionfree, nondenominational independent school for economically disadvantaged girls in New Bedford, Massachusetts, with a named value of teaching its students leadership to be changemakers. We have been collaborating with the school’s administrators and teachers with the goal of increasing equity by ensuring academic rigor is accessible to all its students.

Our Sisters’ School may not have the highest facilities budget, but they make the entire community into their campus. When we visit, the place is bustling with movement: Students are coming and going from sailing trips and museum exhibitions, and visitors ranging from guest speakers to tutors are hustling through the hallways. And their faculty are committed to studentcentered learning. We see inspiring sights every

day—students riding the skateboards they built, presenting powerful and personal poetry, and recording podcasts to effect meaningful change.

In other words, we see students leading.

This school’s focus on leadership skills is so important because students in under-resourced communities may be in greater need of this support. Not only do obvious academic inequities exist across school settings, but differences in emotional and social skill demonstration between individuals often align with broader systemic inequities (Benton, Boyd, & Njoroge, 2021).

For instance, members of certain subgroups—such as students of color and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, intersex, asexual, and more (LGBTQIA+) youth—are more likely to experience trauma and to struggle with mental health issues; they are less likely to feel a sense of belonging in school, less likely to be perceived as leaders by others, and less likely to encounter the tasks that increase leadership skills and opportunities (Gerdeman, 2021; Gündemir, Homan, de Dreu, & van Vugt, 2014; Price, DeChants, & Davis, 2022).

These and other factors influence the level of emotional and social skills students exhibit in the classroom. Hodges developed the concept of a pedagogy of plenty, in contrast to what educator Martin Haberman (1991) once termed the pedagogy of poverty, after observing that compliance-centered classroom climates often exist in schools supporting economically disadvantaged children. In classrooms, students learn to line up behind others, follow directions, regurgitate decontextualized facts on cue, and avoid the disciplinary consequences that derive from perceived disobedience. Students in these settings don’t always believe that their teachers want them to be leaders. Rather, students in these settings are being taught the skills of followership.

Without explicit and ongoing attention to the social and emotional skill development that is so central to leadership training, many students will never know— let alone meet—our behavioral and academic expectations. That means they may never meet the expectations of future teachers, admissions officers, hiring managers, and employers. More to the point, without a focus on leadership development, students will never know or reach their full potential. As a result, existing

gaps in student experiences and outcomes, both in the classroom and in the broader world, will only widen.

Leadership development is not, and should not be, solely the providence of the privileged. If we want a world in which all students are equally likely to become leaders, we need to work toward a world in which every learner in every classroom engages in leadership practices and contributes to a leadership culture.

It can happen. In fact, we know that it is happening. In every school we enter, we are inspired by the number of educators who are leading this work with skill, care, and creativity.

Let’s assume that you are on board with teaching students leadership skills. You may still be wondering if the academic classroom is the best place to do this important work.

We believe so, and here is why.

Some students learn leadership skills on the field, court, or stage. They spend their free periods serving as the secretary of this and the vice president of that Some students—often the same ones—benefit from relationships with role models and access to leadership opportunities outside of school. But for everyone else, there may not be many opportunities to develop a leadership identity and the corresponding abilities.

Even if your school offers all students opportunities to intentionally practice emotional and social skills (say, through an advisory program), opportunities outside the academic context are not enough (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL], n.d.a). The reason is that secondary school students do not automatically transfer skills from one context

to another, both because transfer is a difficult process that requires support and because they see an obvious incentive to code-switch from class to class (Hajian, 2019; van Peppen, van Gog, Verkoeijen, & Alexander, 2022). After all, often what is expected in one room (for example, “Go to the bathroom whenever you want!”) might result in disaster in another (“Where do you think you’re going?!”).

Indeed, research indicates that the instruction and assessment of emotional and social skills are most effective when integrated with subject-specific academic work. In a Learning Policy Institute report on how to support students in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors espouse an integrative approach:

The science of learning and development . . . helps us see that academic, social, and emotional learning are interrelated and reinforcing and that learning is inherently social and emotional. For instance, children and youth learn best when they feel safe, find the information to be relevant and engaging, are able to focus their attention, and are actively involved in learning. This requires the ability to combine skills of emotion regulation and coping strategies with cognitive skills of problem-solving and social skills, including communication and cooperation. (Darling-Hammond, Schachner, & Edgerton, 2020, p. 34)

Elsewhere, the institute advocates for educators to provide students with “opportunities to develop social and emotional skills throughout their school day. Research shows that when [social-emotional learning] opportunities are embedded throughout the school day and integrated into other subject matter, the benefits are even more pronounced” (Darling-Hammond et al., 2020, p. 37).

Not only are leadership lessons most effective when integrated into academics, but academic lessons are also most effective when infused with explicit attention to leadership skills. This is because the practices of every discipline demand the activation of emotional and social competencies. For academic and professional success in any subject area, one needs to motivate, persevere, communicate, and collaborate.

Want one final reason that your academic classroom is the best place for students to learn leadership skills?

Because you are in it. Over the course of a year, you spend countless hours with your students. This enables you to foster the psychological safety that students require to engage in the challenging, vulnerable work of activating emotional and social skills.

Of course, as a teacher, you may not yet feel confident explicitly teaching, say, the communication competencies of leadership. You may say, “I teach social studies, not social skills.” In truth, though, you don’t just teach social studies; you teach students. And you likely do so with more care and skill than you even realize. In order for each of these students, your students, to achieve their leadership potential in social studies class or in any other setting, they need to develop and demonstrate grade-appropriate emotional and social skills. And there is no better person to teach these skills than you (Cipriano et al., 2023).

Think about it: Have you ever run into a group of students at the grocery store? Did they nudge each other and whisper excitedly? Did they yell your name from the other end of the bread aisle? Maybe they stood frozen in the middle of the frozen foods aisle, astounded to confirm that you are, in fact, a real human who exists outside of the classroom and occasionally enjoys fish sticks. Over the years, we have experienced many student run-ins like this. They have asked us to take selfies with them or to autograph their yearbooks or casts, and we have graciously complied.

To others in our lives, we educators are friends, relatives, colleagues, neighbors, or complete strangers. But to our students, we are celebrities. Seriously.

As a secondary school teacher, you may not always get the holiday gifts and stick-figure tributes that elementary educators enjoy, but your students admire and adore you more than you realize. In fact, you are one of the most important people in their lives, and you always will be.

Think about a teacher from your past. What do you remember? Maureen remembers Mrs. Squier. Maureen felt so safe in Mrs. Squier’s class, even when Mrs. Squier tried to gain the class’s attention by hurling chalk across the room. Years later, when Maureen became a Latin teacher, she hoped to foster the same sense of safety (all while refraining from throwing writing utensils). James remembers two English teachers, Mr. Damon and Mr. Crawford, who talked to him not as a student but as a writer. These teachers made James believe he was the kind of person who could one day write a book. And then, many years later, James did write a book. How cool is that?

Just as we still remember our teachers, our students will remember us and the central lessons we taught them. What would you like them to remember? Chances are, you want them to remember how you saw them and believed in them, how you helped them build the social skills and emotional capabilities that have enabled their academic achievement and professional success, as well as their personal and interpersonal health and well-being. Who better to teach them these skills than one of the most important people they will ever know—you?

This brings us to an important point: As a classroom teacher, you are a leader. In fact, in your classroom, you are the lead leader. Whether or not you acknowledge this identity, it is yours. You work daily to harness the motivation to move toward meaningful, value-aligned goals. In the face of countless challenges, you experiment with strategies, shifting your approach in an effort to maintain your momentum. You leverage your communication skills to connect with students, foster psychological safety, and facilitate learning, for them and for yourself. To support this learning, you build the culture and systems needed to enable collaboration.

As you teach the skills of leadership, keep coming back to your identity as the lead leader of the class, just as, for example, a mathematics teacher would

return to their identity as a mathematician by practicing problems before teaching them and by engaging in authentic academic tasks alongside students. When teaching leadership—heck, when teaching anything— it is imperative that we practice what we teach.

For this reason, we have structured the book to support your leadership growth as you prepare to do the same for your students. With this goal in mind, let’s preview the structure and substance now.

In part 1, which consists of chapters 1 and 2, we present the why, offering educators information and inspiration to motivate their work ahead. We also introduce the what , explaining the framework and unit structure, as well as the how, providing practical learning experiences to integrate into academic routines.

In part 2, we dedicate a chapter apiece to each of the framework’s units: Launch, Motivate, Persevere, Communicate, and Collaborate. Each of these chapters opens with Whiteboard Wisdom, a collection of quotes connected to the unit’s theme. If a quote catches your fancy, we encourage you to write it on the whiteboard in your classroom. You may also want to showcase your own favorite quotes and to crowdsource quotes from your students. After all, when we invite students to leverage prior knowledge, we accelerate their in-class learning, increase their self-worth, and prime them to transfer class-specific skills and understandings to their lives outside of school (Quaglia & Corso, 2014).

In part 2, The Foundation section of each chapter opens with an overview of the unit, including its connections to the preceding unit, as well as its essential question and learning objectives. Then, we’ll provide an introduction offering contextual and conceptual framing, information, and inspiration to support implementation. Each chapter introduction ends with a summary in the form of teacher talking points to help you prime students for the learning ahead.

In The Unit section of each chapter, we break the unit that you will be teaching into a series of standard steps. Prep the unit: This section contains questions to activate your own self-awareness about the unit topic and logistic information so you can prepare materials and classroom displays, rotate student groupings, and, in the Communicate and Collaborate units, identify relevant upcoming academic lessons to leverage.

1. Introduce the unit: This section contains a short frame to present the unit to students.

2. Introduce the essential question(s): This section contains a series of one-time exercises to support students in thinking about leadership competency in general and then how it applies to your classroom setting before co-constructing a tool to engage in the new leadership practice of the unit. The exercises model learning experiences that highlight the chapter’s theme.

3. Introduce the leadership learning objectives: This section contains a self-assessment tool you can use to capture baseline and progress data related to the unit’s leadership learning objectives. Students use the tool to evaluate their current strengths and struggles before setting goals.

4. Engage in ongoing leadership practices: This section contains tools for students to regularly use throughout the unit as they engage in your ongoing academic work to highlight the leadership practices explored.

5. Complete the culminating performance task: This section contains an opportunity for students to analyze the data they gather in step 4 in order to complete a short performance task, which yields important takeaways about their leadership identity.

We suggest using the corresponding “Culminating Performance Task Rubric” to assess student performance on each of the culminating performance tasks throughout the year. You may notice that the rubric

does not include the opportunity to award zero points. We recommend going the extra mile to ensure each student completes the culminating performance task (even if you have to sit down and complete the task as a conversation) to ensure that no one falls through the cracks on the path to identifying as a leader. The students most likely to avoid completing the task probably need your extra attention and belief the most.

In addition to completing a unique culminating performance task at the end of each unit, students will also add to their ongoing leader profile, highlighting their strengths, struggles, and strategies related to the unit’s targeted leadership competency. By the end of the year, they will be able to present their completed profiles to peers, parents, caregivers, and teachers. Thus, in each chapter, you will see a leader profile prompt. You also will see a summary, which connects the current unit to the one that follows.

Finally, The Scaffolds unit in each chapter provides commentary and tools for additional student support where needed. There are no scaffolds in the first unit, Launch. In the final unit, Collaborate, these supports are presented as tool kits for use by students in each group role.

We have planted questions throughout the book that we hope will sprout reflection and planning. As you read, we encourage you to annotate. For example, use a question mark for your own questions, a star for information that you want to share with students, and maybe a light bulb to illuminate instruction ideas that arose for you.

As an English teacher, James would often explain to students that when we read, we are entering a conversation with the author. If we let the author do all the talking, we will likely become bored, distracted, and sleepy. It is not polite to fall asleep when, say, William Shakespeare is talking to you. So, James would tell his students, “Talk back!”

As educators and authors, we feel so privileged to be in conversation with each of you. We hope that you will talk back to us by jotting down notes that inform and inspire your instruction.

In part 2, we present the framework’s units: Launch, Motivate, Persevere, Communicate, and Collaborate. Each unit’s chapter includes three sections: (1) The Foundation, (2) The Unit, and (3) The Scaffolds.

In The Foundation sections, we offer information and inspiration to frame the unit ahead. The foundation opens with Whiteboard Wisdom—a collection of quotes connected to the unit’s topic—and ends with Teacher Talking Points to help you frame the learning ahead for students.

Then, in The Unit sections, we deliver a detailed series of steps for implementation.

Prep the unit.

1. Introduce the unit.

2. Introduce the essential question(s).

3. Introduce the leadership learning objectives.

4. Engage in ongoing leadership practices.

5. Complete the culminating performance task.

Lastly, The Scaffolds section includes commentary and tools for additional student support where needed. There are no scaffolds in the first unit, Launch, and in the final unit, Collaborate. In Collaborate, the scaffolds are student-facing tool kits for use in group work.

As students progress through each unit, they periodically add to their leader profiles to celebrate the growth of their identities and abilities as leaders of the class.

“Ut est rerum omnium magister usus (Experience is the best teacher).”

—Julius Caesar

“Anybody who has survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days.”

—Flannery O’Connor

“Never be afraid to sit awhile and think.”

—Lorraine Hansberry

“The mind can be trained to relieve itself on paper.”

—Billy Collins

“I have short goals—to get better every day, to help my teammates every day—but my only ultimate goal is to win an NBA championship. It’s all that matters. I dream about it. I dream about it all the time, how it would look, how it would feel.”

—LeBron James

What quotes would you like to add?

What quotes would your students like to add?

In this unit, student leaders engage in the first foundational leadership practice: reflect and set goals. They engage in a series of self-awareness exercises to understand their emotions and identities. Informed by their growing self-awareness, they regularly set individual goals to accompany the classwide academic and leadership learning objectives that you, the lead leader, have set. Student leaders reflect on how motivated they feel to move toward individual and collective goals, noticing which emotions and identity elements arise and how they impact their motivation. At the unit’s end, student leaders write and deliver a positive story about what motivates them to work hard in your class. The unit’s essential questions and leadership learning objectives are in figure 4.1.

Essential Questions:

How do leaders motivate themselves? How do leaders motivate others?

Leadership Learning Objective:

I know I am a leader because I can

Figure 4.1: Motivate unit essential questions and leadership learning objective.

The following sections include The Foundation, which introduces and contextualizes the Motivate unit; The Unit itself, featuring step-by-step implementation guidance; The Scaffolds for supporting all students; and

Team Discussion Questions to facilitate collaborative learning on your curricular or grade-level team.

Imagine you are delivering a speech to your students about why your work matters to you. You are weaving together an impressive, impassioned argument, connecting your efforts as an educator and practitioner to important elements of your identity (your membership in various groups; your values, beliefs, interests, experiences, and strengths) and to your emotions (perhaps your optimism about what is possible or your pride in the progress students make).

You are projecting. You are gesticulating. You are standing on the desk, Dead Poets Society style. You are in motion, and your students are about to pick their heads off their desks and get themselves in motion, too! Leaders are motivated and motivating, and you are a leader. As such, it is your job to activate and articulate what inspires you in an effort to inspire those around you. Educator Shane Safir (2017) coins the term storientation to describe this science-backed practice (Peterson, 2017) of incorporating personal storytelling into one’s leadership.

Give it a try. On your own, outside of class, take five minutes to write a response to the following prompt.

I am motivated to practice and to teach my discipline because . . .

Once you’ve completed this exercise, take it to class and share both the prompt and your response with your students. If they do not instantly applaud and chant your name while waving a big foam finger in the air, it does not mean that they are unswayed by your undeniable enthusiasm. Give them time. The more that you unabashedly bring big-game energy during this unit, the safer they will feel to eventually do the same. In fact, by the end of the Motivate unit, each leader in the class will be ready to write a similar story about their own motivation.

It sounds like a tall order, right? Sure, some students already exhibit academic motivation. But what about the others? You know, the ones slouched in the back, eyes glazed, mouths agape, like lethargic extras from the classroom scene in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

To prepare you to lead students in this work, we want to spend some time unpacking identity and emotion.

Let’s start with identity. Marketing expert Seth Godin (2018) writes, “You can’t get someone to do something that they don’t want to do, and most of the time, what people want to do is take action (or not take action) that reinforces their internal narratives [about who they are]” (p. 102). Godin (2018) goes on to argue, “Our actions are primarily driven by one question: ‘Do people like me do things like this?’” (p. 104).

How do we educators “sell” students on the importance of our academic discipline? How do we prove to everyone in the room that “people like us” care about this work? According to Godin (2018), the first step for “the marketer, the leader, and the organizer” is to “define ‘us’” (p. 107). In other words, as the lead leader, you will need to work with each student to develop a shared identity as students, disciplinary practitioners, and leaders in a motivated classroom community. In the process, you will support students to reflect on the following interrelated aspects of their individual and collective identities.

• Group memberships

• Beliefs

• Values

• Interests

• Experiences

• Strengths

You may note that we do not list struggles as an element of identity. This is because we do not want to encourage the self-limiting beliefs that we have heard so many times from students, caregivers, and colleagues: “I’m just not a math person,” “I am unathletic,” or “School is not my thing.”

Of course, we know that some communities connect over common struggles: people who have experienced trauma, people with substance use disorders, or people

with disabilities, for example. We do not intend to invalidate these incredibly important affiliations. We simply hope to shift how we think about them. In each of these groups, members bond over shared experiences and the individual and communal strengths that they leverage to overcome their struggles. In our classrooms, we aim for the same.

Each element of our identities is interconnected in countless ways. For example, our group membership shapes our interests, just as our interests influence which groups we choose to join. When our friends get into pickleball, we go out and buy a racket ourselves. This interest, in turn, may lead us to join other groups, like a pickleball club. Similarly, we develop our strengths through experience while often pursuing experiences that allow us to reinforce our preexisting strengths. The better we get at pickleball, the more we seek opportunities to play it, because it feels great to be good at something.

We each belong to many groups. What’s more, we possess more values, beliefs, interests, experiences, and strengths than we could even list. Each of these identity categories is like a bracelet containing countless threads. Sometimes, these threads complement each other nicely. Let’s say we value learning and achievement. The more we learn, the more we can achieve, and the more we achieve, the more opportunities arise to further our learning. Other times, however, the threads of an identity category can clash. If we value balance and achievement, for example, we may find that there are times when we need to sacrifice one for the other.

Imagine that everyone in your class wears an identification bracelet with their many strands of strengths, experiences, interests, group memberships, values, and beliefs braided together. In this unit, learners will unravel these intricately interwoven threads to understand who they are, what they want to achieve, and why they want to achieve it.

Author and educator Zaretta Hammond (2015) likens doing this cultural self-examination work to going on a “treasure hunt or an archeological dig” (p. 56). It is thrilling to imagine what discoveries students will make about themselves and each other and how these insights will inspire their growth as leaders. With this in mind, let’s dig into the elements of identity listed earlier in this section.

We have discussed the evolutionary importance of group membership. Humans have always relied on each other for survival, and our evolutionary impulse to find safety among “people like us” remains. In this unit, students reflect on what makes them unique from others in the room while also embracing their membership and leadership in your classroom’s academic community. Here, representation is important. We will only see every single student embracing their identities as academic leaders once they have seen “people like them” in the role.

As students buy and own their identities as disciplinary practitioners, students, and leaders, their motivation will increase, leading to higher levels of motivation, engagement, skill, confidence, and achievement (think of figure I.2 on page 8). Sociologist Daniel Chambliss finds that the best way to improve as a swimmer is to join a strong team: “Very quickly, the newcomer conformed to the team’s norms and standards” (as cited in Duckworth, 2016, p. 247). Chambliss likens this effect to his own experience as a researcher and writer. “I don’t have that much selfdiscipline,” Chambliss says, “but if I’m surrounded by people who are writing articles and giving lectures and working hard, I tend to fall in line” (as cited in Duckworth, 2016, p. 247). Consider it the power of positive conformity.

Sometimes people join groups because of shared beliefs. But equally important are those beliefs that we develop through membership. When we join a strong leadership community, our beliefs—about ourselves, about our peers, about the world around us—begin to change, increasing our motivation as a result. In a classroom culture of leadership, everyone believes the following (CASEL, 2024; Safir & Mumby, 2024).

• This work is important.

• Everyone here has what it takes to do this work.

• We will all support each other to do this work.

A vision statement provides one powerful way to express and strengthen one’s beliefs. Figure 4.2 is an example.

By the end of this year, you will be doing (academic work ) I know this is true

Look to your left Look to your right Your peers will also be doing this work, in part because of the leadership work you will do to support each other’s personal and academic growth this year

Figure 4.2: Vision statement example.

When we said this to our students, they believed us. Students worked very hard. And because our students could process why doing this work mattered in their own worlds—how doing this work supported them individually in receiving the benefits of the leadership culture we described earlier—they felt safe among their peers and a sense of being seen and valued.

Classroom mantras, such as the following, offer another way to build a belief-based group identity.

• Each one of us is essential to this classroom and belongs here.

• We can do hard things.

• We have important work to do together.

• When we do this work, we earn respect.

• When we do this work, we gain the power to make a difference in our community.

Our values help us set meaningful goals and maintain motivation as we pursue them. What’s more, our values help us reset during moments of dysregulation. For this reason, this unit offers the opportunity for each student to name their core values and to co-construct a list of the class’s core values. They will then return to this work in the Persevere unit.

In Stephen Frears’s 2000 film High Fidelity, based on Nick Hornby’s novel of the same name, John Cusack plays Rob Gordon. Gordon loves popular culture, particularly popular music. “What really matters,” Rob tells the camera, “is what you like, not what you are like. Books, records, films: These things matter” (Frears, 2000). While we would argue that what you are like is also incredibly important, we agree that our interests are integral elements of who we are. To understand and engage our students, we need to know about their interests. Doing so deepens relationships and fosters psychological safety, which students need to feel to take academic risks. It also opens the door for making curricular connections to individuals’ interests.

Our experiences profoundly impact our identities, for better or worse. As educators, we are often working to undo the damage from negative experiences. Some students, because of their experiences, do not trust adults, and it becomes our job to demonstrate predictable warmth, support, and stability, knowing that it may take months or years until they begin to trust us. Other students come to class carrying baggage from negative academic experiences. They tell you they “hate social studies” or they “suck at science.” In both cases, our job is to facilitate new experiences that, over time, shift their experience-informed beliefs. As a result, students can begin to reframe past experiences and adapt their identities accordingly. “I hate social studies” becomes, “I didn’t really fall in love with social studies until my freshman year.” “I suck at science” becomes, “I used to

lack confidence in science, and I kind of shut down. But this year, things feel a lot clearer to me, and I know I can be successful if I put in the work and advocate for myself.”

Here is the thing about strength: It is relative. We are all stronger in some areas than others, and in every area, there is someone stronger than us, just as there is someone struggling more than us. The trick is to lean into positive narration: In what ways are you strong? In what ways are you stronger than you used to be? In what ways will you be stronger in the future? And in what ways are you strong, simply because you are you, and no one else can make that claim?

In the middle school art class of our longtime colleague, Tim Walker, students strived to emulate the styles of great artists before them. But the goal, always, was for the young practitioners to build skills to create their own style. Around the room were diverse models of artistic excellence, from Van Gogh’s Head of a Skeleton With a Burning Cigarette to Stan Lee’s Spider-Man comics. And somewhere in that vibrant visual mélange hung a small sign that read, “No one can draw like you.”

In an identity-forward leadership culture, we learn that every element of identity can be a strength. Our similarities bring us together, enabling positive connection and productive collaboration, and our differences make us invaluable as individuals because no one else can contribute what we can.

If we are motivated by who we are and who we want to be, we also are motivated by how we feel and how we want to feel. As Marc Brackett (2019), the director for the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, writes in his book Permission to Feel ,

research proves that “emotions give purpose, priority, and focus to our thinking. They tell us what to do with the knowledge that our senses deliver. They motivate us to act” (p. 25). John Hattie (2023) concurs that students’ “motivations when choosing x over y is . . . related to the student’s emotions— particularly, their sense of efficacy, task value, and expectations” (p. 109). In other words, how we feel impacts how we move.

So, let’s talk about emotion. Chances are that word sparks some uncomfortable emotions for you, because we are not used to talking—like, really talking —about our emotions.

To activate our students’ motivation, we must help them understand both how they are feeling and how they can productively process and express these emotions. Essentially, we must teach them emotional literacy: how to understand the messages that their bodies send them and how to translate these messages into words so that others around them understand how they are feeling.

The first step in learning a language is listening. And there is a lot to hear. Our emotions are always telling us something helpful, though the tone, volume, and message may vary. For example, the anxiety churning in students’ stomachs as they begin a test tells them that they are embarking on an endeavor that is important to them, so they should stay alert and try their best. As long as this anxiety doesn’t overstay its welcome, it is a very helpful house guest.

However, people don’t always hear these internal emotional messages amid the racket around them. Often an emotion’s voice is drowned out by external noise: phones, friends, food, video games, vape pens . . . the list continues.

As educators, we need to provide a space that is quiet and focused where students can listen closely to their emotions. Beginning in the Motivate unit, we

incorporate ongoing opportunities to embed individual reflection into academic routines. We also introduce a helpful emotional literacy tool called the Mood Meter. After all, it is not enough to simply hear one’s emotions; students need to build their emotional vocabulary so they understand the language they are hearing.

We cannot fully feel an emotion until we acquire it conceptually. And the easiest way to acquire the concept of an emotion, according to emotion scientist Lisa Feldman Barrett (2017), is by learning a word for it. Emotions are not only the start of understanding our motivation, but they also form the bridge to the work of the Persevere unit because simply validating our emotions by naming them makes us feel better, so we can keep moving toward our goals.

To activate their leadership potential, students must develop a nuanced understanding of how they are feeling and how these emotions impact their motivation to persevere, communicate, and collaborate in class. And as they move through the discomfort of academic resistance, you must offer ongoing opportunities to experience enough pleasant emotions to keep them going.

To do so, it will be your job to offer motivating work. We hope that this job of yours feels motivating to you. Remember, motivating work is purpose driven, appropriately challenging, social, and aligned to identity. Take a minute to consider your purpose for motivating students. Consider how this challenging social work will align with your identity as an educator who believes in students and who leverages professional strengths to ensure that everyone loves school as much as you do.

As you dig into this chapter’s The Unit section, these talking points provide helpful language to use when discussing motivation with your students.

• “The first foundational condition of a leadership culture is the presence of motivating work, and I work hard to put work in front of you that is worthy of your motivation. As you engage in academic work during the Motivate unit, you are going to focus on motivating yourselves and each other to do the important work of this class. With this in mind, I want to start

by telling you why I find this work motivating. I am motivated to practice and teach this discipline because . . .”

• “At the end of the unit, you are going to tell your own story to the class about what motivates you. To prepare, we are going to engage in the first foundational leadership practice: reflect and set goals. Since motivation stems from our identities and our emotions, we will reflect specifically on who we are—our group memberships, values, beliefs, experiences, and strengths—and how we feel.”

• “Let’s talk for a minute about identity and its connection to motivation. According to marketing expert Seth Godin, ‘Our actions are primarily driven by one question: “Do people like me do things like this?”’ I want us to build the safety necessary to take risks by sharing openly about all the ways we are each unique. At the same time, I want us to determine in what ways we are similar. People like us, in this class, are leaders, which means we all work hard to activate our self-awareness and set motivating academic goals. We also work hard to support each other with this important work.”

• “Motivation also stems from emotion. We are motivated to do that which feels good. When important work doesn’t feel good, we need to understand why we are feeling that way and reconnect with our motivation so we can maintain momentum toward our goals. For this reason, we are going to build in a lot of practice identifying and sharing how we are feeling during this unit.”

• “This work is so important to me because you all are so important to me. I know that it won’t be easy, but I feel incredibly motivated to achieve my goal of helping each of you connect with your motivation and embrace your identities as leaders of this class.”

As the lead leader of the Motivate unit, you will engage in the following steps.

You will reflect on motivation and prepare logistics for about fifteen minutes (plus time to preview the unit). Reflect on the unit’s leadership competency, practice, and condition by taking notes in response to the following questions.

• How have you grown as a leader by reflecting and setting goals?

• Can you describe the motivating work students will encounter in this unit?

Update your classroom displays by posting the Motivate unit’s essential questions and leadership learning objectives and choosing a quote from the samples in this unit’s Whiteboard Wisdom. Photocopy or download the resources listed in steps 1–5.

Determine if you would like to use the same roles students took on during the Launch unit or rotate their groupings.

Throughout the year, there are two options for ongoing student reflection: (1) a shorter-form reflection log and (2) a reflection bookmark designed to accompany a journal and provide more room for writing. Decide which reflection tool you will use.

Select an emotional literacy tool to use throughout the year. You and your students might already use a tool, such as Robert Plutchik’s (1980) Wheel of Emotions or the Center for Nonviolent Communication’s (n.d.) Feelings and Needs Inventory. If so, feel free to stick with what you know. However, our favorite for secondary school students is the Mood Meter (https:// tinyurl.com/mveeh25u), developed by Brackett (2019). It organizes emotions into four quadrants, depending on the degrees of pleasantness and energy that the emotions carry. Emotions in the two left quadrants feel unpleasant. Emotions in the right two quadrants feel pleasant. Meanwhile, the two lower quadrants contain lower-energy emotions, and the two higher quadrants contain higher-energy emotions.

We recommend modifying the Mood Meter to include scattered blank spaces so students can supply their own emotion words. This process helps students internalize the meter’s organization. It also enables the inclusion of all kinds of incredible language: words students use at home, including those that lack an English equivalent; subject-specific terminology (like gamesome during a Shakespeare unit or calculating for mathematics class); and, of course, selections from the dynamic lexicon of teenagers. (One of our favorite parts of working in schools has always been learning—and then awkwardly using—student slang. No cap.)

Introduce the Motivate unit using the Teacher Talking Points. You may choose to include the personal reflections that you recorded during preparation. Connect this leadership unit to your current academic unit. Pause to ask students what thoughts, feelings, and questions arise for them as they hear about the upcoming unit.

Before moving on, review the norms you set (you may have created them with and recorded them on chart paper after using the reproducible “Norms Protocol,” page 59).

Prepare students by sharing the reproducible “Motivate: Culminating Performance Task” (page 77). This way, they will know what to expect, and instead of dedicating any mental or emotional energy to wondering or worrying about the end point, they can focus on the best route there. If you choose to use the “Culminating Performance Task Rubric” (page 78), share that with students as well.

Here, you establish the essential questions leaders will explore throughout the unit and help students build self-awareness about their motivation.

By the end of the Motivate unit, students will have investigated the following questions.

How do leaders motivate themselves?

How do leaders motivate others?

If time is short, cut the gallery walk. Teaching teams may choose to complete the gallery walk exercise and identity exercise only once, such as in an advisory program or homeroom, and debrief in class to note discipline-specific connections.

To initiate exploration of the questions, introduce a twenty-minute gallery walk that allows students to consider the questions broadly and apply them to the context of your class.

1. Ask each project manager to post one piece of chart paper on the wall and to create a T-chart with headings, as shown in figure 4.3.

2. Invite students to silently move around the room and respond in writing to the questions. Encourage responses that include new ideas, connections to past learning, questions, and feelings.

3. As the sheets begin to fill, prompt students to write responses to their classmates’ contributions on the chart paper. What do they agree with? What do they (respectfully) disagree with? What emotions, ideas, and questions are coming up for them?

taking in their groups. Whenever we facilitate these exercises, we hear participants organically share details about their experiences that give us greater insight into how these individuals see themselves and would like to be seen. Even the bonus question in the experiences reflection exercise, which asks participants to pick a performer who would play them in the movie version of their life, provides a window into someone’s identity. As students begin, decide if you would like them to share their responses with you. If so, ask the advocate to take notes during the experiences reflection exercise and collect them during the identity exercise.

This exercise will take about twenty minutes. Share highlights from the research presented in this chapter’s The Foundation section (page 64) about the importance of identity in understanding our motivation. Ask the project manager from each group to gather one copy of the “Experiences Reflection” (page 79) for the facilitator and to keep time. Ask the facilitator on each team to lead their team through the exercise, including the debrief section. At the end, ask the motivator to share themes from the discussion about how the team’s experiences impact motivation.

Ensure students are seated in their teams. Ask the project manager in each group to gather emotional literacy tools for their team. Then, share highlights from the research presented in this chapter’s The Foundation section (page 64) about the importance of emotions in understanding our motivation. Ask each motivator to facilitate their group’s revision of their emotional literacy tool by editing provided words to include the words that feel most authentic to them. Students can continue to revise the emotions in the chart as they like throughout the year.

The experiences and identity exercises are designed to allow students to determine how vulnerable they would like to be in sharing their experiences and identities. Permit students to control the level of risk they feel safe

This exercise will also take about twenty minutes. Ask the project manager from each group to get a copy of the reproducible “Identity Exercise” (page 80) for each group member and to keep time. Ask the facilitator of each group to lead their group through the identity exercise. Ask the motivator to share themes from the discussion about how the team’s identity impacts motivation.

Let students know that these exercises were designed to support their self-awareness, which will help them identify meaningful goals that they are motivated to achieve.

Here, you will set clear expectations and criteria for success and provide a baseline self-assessment. By the end of the Motivate unit, students will be able to make the following claim.

I know I am a leader because I can . . .

Reflect on my emotions and identity to set goals I am motivated to pursue and motivate others to do the same.

Distribute the reproducible “Motivate: SelfAssessment” (page 81); ask students to complete the assessment and set a goal for the unit. After about ten minutes, collect students’ papers. Later that class period or on another day, after reviewing their responses, share takeaways and themes with students and ask if they have observations or questions. Throughout the year, you and your students are welcome to modify the learning objectives to personalize them or prioritize them.

As you implement the academic unit, ask the motivator to join you in reminding students of which leadership objectives they are working toward, and why they are important, using the following stems.

We are doing this exercise because . . .

This learning experience will help us develop the skill of . . .

We are engaging in this practice so you will be able to . . .

Better yet, prompt all students to connect each activity to the appropriate objective themselves with the following.

Take a minute to reflect on why you think we are engaging in the upcoming activity. What skill do you think we are activating? After a minute of reflection, I will prompt you to share with your neighbor. Then, I will invite someone to share what they heard from their partner.

Return to this self-assessment at the unit’s midpoint and again at the end so students can see their progress. If you choose to do these assessments digitally using tools like Mentimeter, you can also monitor progress over time for individuals and sections and celebrate that progress with students.

This engagement builds self-awareness about emotions and identity in your academic class to help

everyone stay motivated to work hard. Throughout the unit, students should complete a reflection two or three times a week for five minutes apiece. This step can be completed at the end of class or at home.

Distribute the reproducible “Motivate: Reflection Log” (page 82) or the “Motivate: Reflection Bookmark” (page 83). We encourage you to use the tool as frequently as possible, but at least twice a week. The reflections should take place at moments that offer particularly valuable opportunities for self-examination: the completion of a challenging academic task, the return of a graded assessment, or the celebration of an accomplishment. There is also value in asking students to reflect on their motivation during more mundane moments, like taking notes on a lecture or engaging in quiet individual work. Reflecting on motivation to complete a variety of tasks and in a variety of classroom configurations (after discussions, small-group work, or doing a lab) can build more dimensionality to students’ understanding of their motivation.

Ask students to use their emotional literacy tool and the information they recorded on the “Leader Profile” (page 53) as they complete their ongoing reflections. If possible, periodically ask them to share motivational advice with younger students—for example, if they participate in mentor programs, or if they take classes or ride the bus with students from younger grades. Research conducted with high school students finds that this practice increases the motivation of the advice giver (Eskreis-Winkler, Milkman, Gromet, & Duckworth, 2019).

See figure 4.4 (page 72) for sample student responses to the bookmark prompts.

Tell students to periodically review the data they collect about themselves this unit. Pose the following questions to them.

• What trends do you notice?

• What motivates you?

• What do you learn when you consider your emotions and your identity (“I am someone who . . .”)?

Goals

Collective Goal

Individual Goal

Motivation

Emotion

Name an emotion that you felt today as you worked toward these goals

What was happening?

Why do you think you felt this way?

Identity

Name an element of your identity that you were aware of as you worked toward this goal Consider your strengths, struggles, interests, experiences, values, and social identity markers

What was happening?

Why do you think that you became aware of this element?

Challenge

What level of challenge did you experience?

What in the work felt engaging or disengaging?

How much do you agree with the following statement? I felt motivated to work toward these goals today. Explain your choice

Celebrate your successes in staying motivated

Collective goal: Use a model to explain how the interaction between light and an object’s material surface impacts how the object appears.

Individual goal: Use my resources.

Emotion: I felt proud because I was really stuck when I first started constructing my model, but then I was looking at the one that we made together last class. I was able to kind of copy it but put in new info for this experiment.

Identity: I think what came up for me is that I’m capable of learning this stuff even though I haven’t always considered myself a strong student. Sometimes I feel like other people get stuff so quickly while I keep making the same mistakes, but when I really pay attention to why I’m messing up, I’m able to spot a pattern. On the last test, I didn’t use that resource sheet at all, and it practically had the answers on it!

Challenge: 3/5—I liked when we shared at the end. It was cool that we each needed to talk about one time we got stuck. I learned that other people also find things hard, and I was able to explain cause and effect to Marcello!

Self-Assessment: I think I was really motivated today. I want to be ready for the physical science fair in two weeks, and I need to do better on the unit test. I know that this is a hard class, so I feel good that I’m figuring things out.

The culminating performance task helps crystallize students’ self-awareness and ignite their motivation through storytelling. During this step, they also build relationships and inspire others. You may allow students time during an advisory program or study hall

to prepare for the presentation, prompting them to notice similarities and differences about their motivation across classes. If students have very similar data across classes, you may allow them to address multiple classes using the same assignment.

Distribute the reproducible “Motivate: Culminating Performance Task” (page 77), in which students review their work from the unit and identify a larger heart goal that describes their vision for what they can achieve in your class when motivated.

To close, ask students to complete the Motivate section of their leader profile, including the end-of-unit reflection. They can revise their heart goal and motivation throughout the year, as desired. When possible, share these updates to students’ leader profiles with caregivers and invite feedback.

This unit’s work provides the foundation for all future units. In the next unit, students will build the skills needed to persevere toward their meaningful leadership goals.

As you engage in the work of building motivation, inevitably, some students will need additional support. Here are tools to support you in addressing issues we commonly see come up in our work. As you follow any of these suggestions, keep in mind what you know about the student, and ensure you are going out of your way to demonstrate that you believe in them as leaders and that they are worthy of your respect. Do this by praising them generously; asking them questions; and, when you offer ideas, asking students how they feel about those ideas. The scaffolds include returning to the relationship, ensuring academic challenge is a justright fit, building their subject-specific identity, monitoring class morale, and finding role models.

If a student doesn’t seem motivated, the first move is to assess the strength of your relationship. How well do you and this student know and like each other? If your relationship isn’t as strong as it could be, make moves to build that relationship. Ask your teaching team for ideas on how to deepen your empathy and appreciation for that student and share professionally about yourself with that student. During class, as you circulate, make