ECHOES ECHOES ECHOES

FRAGMENTED HOMELAND FRAGMENTED HOMELAND FRAGMENTED HOMELAND

FRAGMENTED HOMELAND FRAGMENTED HOMELAND FRAGMENTED HOMELAND

We acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land upon which we reside, work and study, the Wurundjeri People of the Kulin Nation. We pay respect to their elders past and present, and acknowledge that sovereignty of this land was never ceded.

In any discussion of cultural memory and postcolonial landscapes, acknowledgment of the rights and experiences of those whose homelands were colonised is essential. This zine examines the impact of colonialism on Vietnam and Cambodia, and recognises the irreversible damage inflicted on cultural identities, histories, and landscapes.

As we explore both diasporic and mainland perspectives, we extend our respect to all those whose lands and cultures have been shaped or fragmented by colonial rule. The stories of exile, displacement, and memory restoration in these films remind us of the enduring impact of colonial histories.

Always was, always will be.

Before you read our zine, we suggest you to open our curated playlist for the zine by simply click on this link below:

We recommend you to listen to the playlist while reading the zine to enjoy the sensory experience that we are trying to recreate.

Inside the zine, we also embedded a video link which will take you to the particular scene in The Scent of Green Papaya (1993) which will further enhance your experience. The link can be found on page 17. You do not want to miss it!

Welcome to Echoes of A Fragmented Homeland:

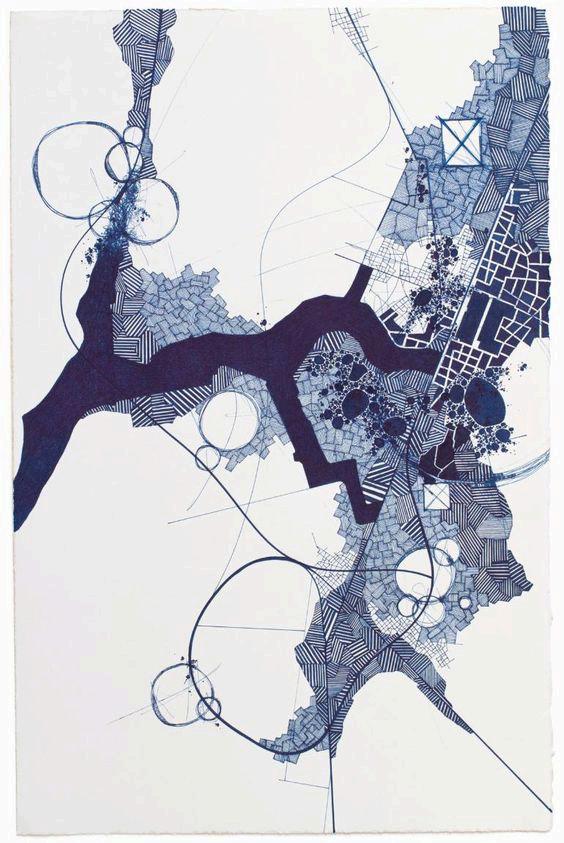

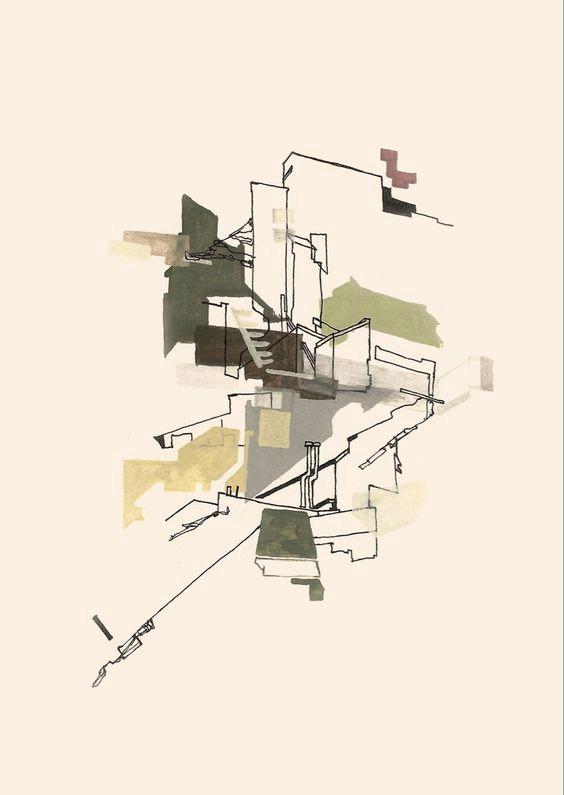

Indochina in Exile, a journey through fragmented homelands, distant memories, and the everpresent ripple of colonial trauma. This zine is our collective attempt to piece together the shards of a history that refuses to stay silent, much like the lands of Indochina themselves Vietnam and Cambodia, where echoes of exile and home intertwine like tangled roots beneath the soil.

WE INVITE YOU TO LINGER. TO TOUCH. TO FEEL.

In this exploration, we invite you to linger. To touch. To feel. Memory, like cinema, is not a fixed thing. It is sensory, lived, haptic It is the smell of papaya lingering in the air, the soft grain of rice slipping through fingers It’s the heavy silence between drone shots and the quiet tremble of voiceover narrations. These are the fragments that filmmakers like Tran Anh Hung and Rithy Panh offer to us not complete stories, but windows into diasporic lives stretched across oceans and continents, past and present.

We were drawn to this project because the films speak to more than just their own histories They speak to the universality of displacement, of fractured identities, of trying to reclaim a home that has been forever altered. How do we remember what has been taken from us? How do we construct identity in the aftermath of colonization? These are questions our filmmakers ask, and in their answers, we find not resolution, but reflection.

Here, you will meet the ghosts of forgotten homelands, see landscapes that are both real and imagined, and navigate memories that are at once painful and tender. You will not find a clean history. You will find fragments pieces of Indochina scattered across time and space, stitched together by cinema. This is not a neat narrative. It is a collective act of remembering, of imagining, of feeling through the stories that we cannot bear to lose

So, sit with us. Watch with us. Feel the weight of these exiled echoes.

Linh, Michelle & Gabriel

WHERE DO WE COME FROM?

are questions posed by French painter Paul Gauguin’s most famous works. Gauguin’s infamy is irrevocably tied to France’s colonial history in Tahiti, a small but not insignificant corner of the violence and trauma inflicted by the colons. Spanning across seven continents, France’s past as the second largest colonial empire, just after Great Britain, continues to stain the territories.

QUE SOMMES-NOUS?

OÙ ALLONS-NOUS?

D'OÙ VENONS-NOUS?

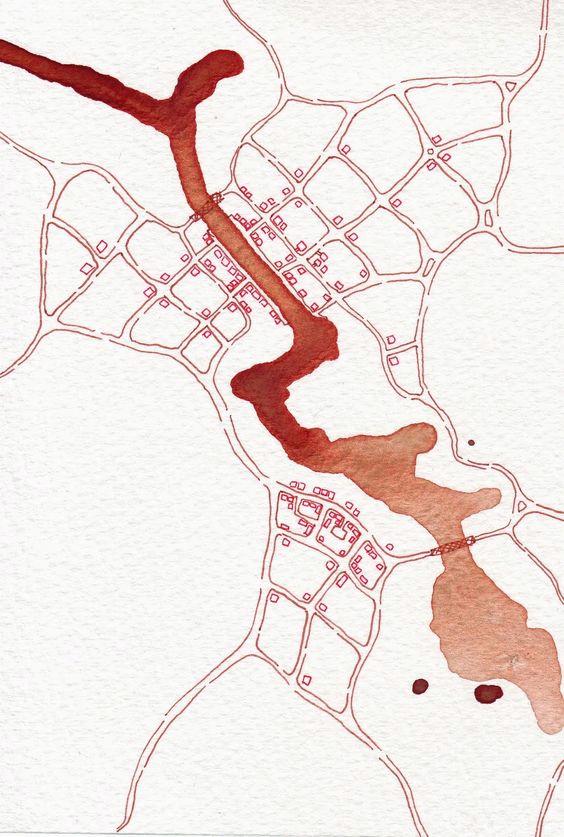

Indochina was one of these French territories. Postcolonial Vietnam and Cambodia, for this zine, highlight how diasporic filmmakers work to store and restore the fragmented memories of their motherlands How do these filmmakers reimagine the collective history of this period? How do they address the tensions of memory as a means of understanding colonial trauma? How does each individual or group of individuals project their subjective memory of a shared experience: colonialism? (Halbwachs, 1992)

Focussing on The Scent of Green Papaya (1993) and Rice People (1994), respectively by Vietnamese-born French filmmaker Tran Anh Hung and French-schooled Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh. With these two as the centre, we will draw comparisons between what we will be calling Mainland Filmmakersfilms by those born and worked in Vietnam or Cambodia, and Outsider Filmmakers - which represent these colonial territories from the perspective of a “foreign” country such as France or the United States.

With the aid of The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses by Laura U. Marks, and Dana Polan, we will explore memory as language, image, touch, things, and senses.

We challenge readers to weave through this fragmented experimentation. Linger on the film stills and background art Meditate upon our critical commentary. We hope that you will be encouraged to broaden your film viewing habits and consider the subtle and unspoken effects of colonial occupations, and continue to engage with cinema with decoloniality.

HOW DO THESE FILMMAKERS REIMAGINE THE COLLECTIVE HISTORY OF THIS PERIOD?

HOW DO THEY ADDRESS THE TENSIONS OF MEMORY AS A MEANS OF UNDERSTANDING COLONIAL TRAUMA?

D'OÙ VENONS-NOUS?

WHERE DO WE COME FROM?

CHÚNG TA LÀ GÌ? WHATAREWE? WHEREARE WE GOIN G ? OÙALLONS-NOUS? C HÚNG TA ĐI VỀĐÂU?

QUE SOMMES-NOUS?

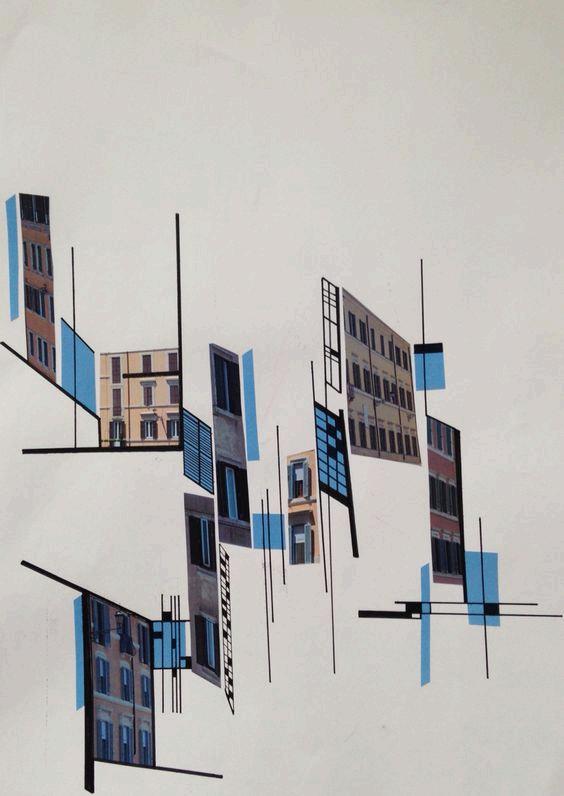

French colonial rule in Indochina (which included modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) lasted from the late 18th century until the mid-20th century. This period generated many cultural and cinematic portrayals that reflect colonial attitudes, exoticism, and Orientalism, shaping Western perceptions of the region.

For this project, we focus on Vietnam and Cambodia, whose histories are marked by intense struggles for independence from French colonial rule. The First Indochina War (1946–1954) and the subsequent decolonization movement were pivotal in shaping their national identities. Films produced during and after this colonial period— particularly those created by diasporic filmmakers often delve into themes of anticolonial resistance, fractured memory, and identity. These works offer a unique lens through which filmmakers, both from the homeland and the diaspora, reinterpret their colonial past and explore cultural identities, navigating the complexities of belonging, displacement, and cultural independence.

Nameless River. I was born sobbing

Blue sky. Vast earth. Black stream water

I grow with the months, the years

With no one to watch over me

Nameless is the river

Colourless is the flower

Perfume

Without a voice O river, O passerby

In the closed cycle

Of the months, the years

I cannot forget my debt to my rotts

And I wander through worlds Toward my land

Tran Anh Hung

“Cyclo”

1995

Directed by Rithy Panh

Rice People was the first Cambodian film to compete at the Cannes Film Festival, earning a Palme d'Or nomination in 1994. Set in post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia, the film tells the story of a rural family struggling to bring in a single season's rice crop.

Yim Om and Yong Poeuv, a married couple with seven daughters, often wonder whether having a son would ensure the continuation of their legacy. Yet, alongside this desire, there is an underlying anxiety—will their rice fields survive to be passed down to their children?

The film captures the deep connection between the farmers and their land, portraying rice not simply as a source of sustenance, but as life itself. It reflects the devotion of those who live for rice, and in some ways, die for it, as the heart of survival and existence in rural Cambodia.

Directed by

Trần Anh Hùng

In 1950s Saigon, the story of Mùi, a young girl who arrives to work as a maid, begins to unfold. Through her innocent gaze, we witness the lives of those around her and the quiet nostalgia that lingers over them. As we follow her through her daily routines, we experience the small joys of a peaceful life and, unexpectedly, the discovery of love.

*The Scent of Green Papaya* (1993) offers a sensory experience, inviting the audience to become immersed in its rich textures and aromas while guiding them with graceful poetry through the delicate tapestry of life. It serves as a quiet tribute to family and to Vietnamese women, who form the heart of that bond like seeds taken from fresh fruit, growing pure and shining with quiet brilliance.

Trần Anh Hùng crafted a delicate story about a world unfamiliar to many, offering a serene contemplation of life developing in quiet harmony. It is a poetic reflection that evokes a sense of simple happiness. IT IS AN ALLURING SENSORY EXPERIENCE. EVERY SENSES IS CONSTANTLY EVOKED.

River Changes Course (2012)

Directed by Kalyanee Mam

Kalyanee Mam’s A River Changes Course is a powerful documentary that intimately follows the lives of three rural Cambodian families, each grappling with the rapid changes brought by the country’s development. Through its mainland perspective, the film provides an authentic insight into the contemporary struggles of rural Cambodia, where environmental degradation and displacement threaten traditional ways of life. By focusing on the daily realities of ordinary people, Mam’s documentary

offers a grounded portrayal of Cambodia’s socio-economic challenges. The documentary genre amplifies the authenticity of this narrative, giving viewers a raw, unfiltered view of the country’s transition, and reflecting broader issues faced by many developing nations.

Cambodia Through The Outsider’s Len

First They Killed My Father (2017)

Directed by Angelina Jolie

Angelina Jolie’s First They Killed My Father is a harrowing retelling of the Cambodian genocide under the Khmer Rouge, based on Loung Ung’s memoir. Told through the eyes of a five-year-old, the film presents a child’s perspective of the terror, displacement, and survival during this dark period in Cambodia’s history. While Jolie's intention is to honour the memory of the victims, the film's outsider, Westernised gaze shapes its narrative, often relying on cinematic spectacle and dramatic sequences to convey the trauma

Angelina Jolie’s portrayal emphasises a more universal, emotionally resonant storyline, framed for a global audience unfamiliar with Cambodia’s history, rather than the deeply rooted, sensory approach found in diasporic works like The Scent of Green Papaya or Rice People.

Nostalgia for The Countryside (1995)

Directed by

Nhật Minh

Dang Nhat Minh’s Nostalgia for the Countryside (1995) is a deeply poetic exploration of rural Vietnam, following the story of Nham, a young man who grapples with the changes in his small village as it faces modernisation. Rooted in Vietnam's rich literary and poetic traditions, Dang Nhat Minh’s film reflects a mainland perspective that is intimately connected to the land, culture, and people of Vietnam. The film is imbued with a sense of longing and reverence for the rural countryside, portraying the beauty of simple village life while also

acknowledging the hardships and alienation that come with the changing times. Dang Nhat Minh’s film captures the raw emotions of those who remain in Vietnam, highlighting the tensions between tradition and modernity, and evoking a deep connection to the land that is less filtered by the distance of exile.

Vietnam Through The Outsider’s Len

The Lover (1992)

Directed by

Jean-Jacques Annaud

Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Lover (1992) is a sensual and visually evocative film set in colonial Indochina. Based on Marguerite Duras’ semi-autobiographical novel, the story revolves around the forbidden romance between a young French girl and a wealthy Chinese man, set against the backdrop of a racially and socially divided colonial Vietnam. Through Annaud’s lens, Indochina is portrayed as an exotic, distant land, rich with imagery that caters to Western fantasies of the East lush landscapes, forbidden desires, and complex power dynamics. The Lover reflects a colonial,

Westernised gaze that romanticises Indochina, focusing more on the personal and sensual experiences of its French protagonist than the historical realities of colonial rule While visually stunning, the film is more concerned with the intimate, emotional drama between the characters, often overlooking the broader socio-political context of colonialism.

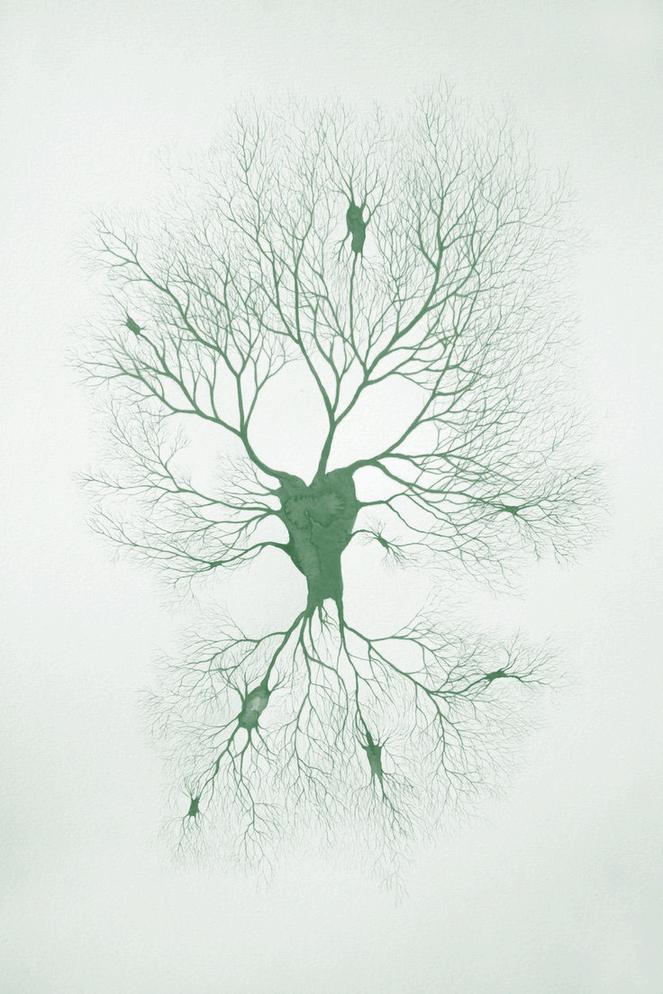

There exists a need for diasporic There exists a need for diasporic filmmakers to restore the memory filmmakers to restore the memory of their homeland. Oftentimes of their homeland. Oftentimes the trauma of the colonial space the trauma of the colonial space is much too immediate, so they is much too immediate, so they are consequently suppressed and are consequently suppressed and erased to protect the self from erased to protect the self from its harm. The generations its harm. The generations proceeding attempt to reclaim proceeding attempt to reclaim this history through their own this history through their own means, for filmmakers, that is means, for filmmakers, that is often through the position of the often through the position of the camera lens. They challenge film camera lens. They challenge film as a solely audiovisual medium, as a solely audiovisual medium, and support film as a haptic and and support film as a haptic and multi-sensorial medium (Marks multi-sensorial medium (Marks 2000). Marks argues that the 2000). Marks argues that the very “ awareness of the missing very “ awareness of the missing sense of touch” (2000, 129) in sense of touch” (2000, 129) in combination with the audiovisual combination with the audiovisual base of film, is how memory is base of film, is how memory is encoded. encoded.

Marks and Polan: Marks and Polan: ““OObjects, bodies, and intangible bjects, bodies, and intangible things hold histories within them things hold histories within them that can be translated only that can be translated only imperfectly. Cinema can only imperfectly. Cinema can only approach these experiences approach these experiences asymptotically, and in the process asymptotically, and in the process it may seem to give up its proper it may seem to give up its proper (audiovisual) being” (audiovisual) being” (2000, 131). (2000, 131).

The tactile nature often seen in The tactile nature often seen in the films of diasporic filmmakers, the films of diasporic filmmakers, like Tran and Panh, lingering on like Tran and Panh, lingering on the extremities of the body - the the extremities of the body - the hands and feet - as the point of hands and feet - as the point of contact for memory construction. contact for memory construction.

If memory to diasporic If memory to diasporic filmmakers is fragmentation, filmmakers is fragmentation, what is the objective of outsider what is the objective of outsider filmmakers? Diasporic filmmakers filmmakers? Diasporic filmmakers take a rather epistemological take a rather epistemological approach with the tools of approach with the tools of cinema at their disposal (Naficy cinema at their disposal (Naficy 2001). One of the ways in which 2001). One of the ways in which epistolarity is produced, argued epistolarity is produced, argued Naficy, is “under erasure ” , these Naficy, is “under erasure ” , these “narratives invariably spring from “narratives invariably spring from an injunction or a prohibition an injunction or a prohibition against writing and connecting, against writing and connecting, which takes many forms” (2001, which takes many forms” (2001, 115). Letters, oral storytelling, and 115). Letters, oral storytelling, and poetry transform into voice overs poetry transform into voice overs in filmic language. The tool of in filmic language. The tool of voiceover is confrontational to voiceover is confrontational to viewers, and immediately situates viewers, and immediately situates them into the subjectivity of them into the subjectivity of characters. characters.

Epistolarity sets them apart from Epistolarity sets them apart from the outside filmmakers, who the outside filmmakers, who seem to take an approach that seem to take an approach that emphasises a certain spectacle emphasises a certain spectacle of the events unrolling on screen. of the events unrolling on screen. The Lover The Lover (Annaud 1992) and (Annaud 1992) and First First They Killed My Father They Killed My Father (Jolie 2017), (Jolie 2017), for example, are both semi- for example, are both semiautobiographical and penned by autobiographical and penned by those who have lived in the those who have lived in the colonial space of Indochina. colonial space of Indochina.

However, the direction of French However, the direction of French and American production, and American production, magnifies the melodrama of the magnifies the melodrama of the film, pertaining it as a classical film, pertaining it as a classical narrative, as opposed to a narrative, as opposed to a collection or snapshot of a collection or snapshot of a memory in time. memory in time.

“A significant number of “A significant number of intercultural film and intercultural film and videomakers embed a critique of videomakers embed a critique of visuality in their work. Often visuality in their work. Often they draw from critiques of they draw from critiques of ethnography” ethnography” -Naficy-Naficy-

This well-known critique asserts This well-known critique asserts that ethnographic photography that ethnographic photography and film have objectified non- and film have objectified nonWestern cultures and made a Western cultures and made a spectacle of them; they have spectacle of them; they have reduced cultures to their visual reduced cultures to their visual appearance; and they have used appearance; and they have used vision as part of a general will to vision as part of a general will to know. (2001, 133) know. (2001, 133)

THE DIRECTION OF FRENCH THE DIRECTION OF FRENCH AND AMERICAN PRODUCTION, AND AMERICAN PRODUCTION, MAGNIFIES THE MELODRAMA MAGNIFIES THE MELODRAMA OF THE FILM, PERTAINING IT AS OF THE FILM, PERTAINING IT AS A CLASSICAL NARRATIVE. A CLASSICAL NARRATIVE.

We argue that the We argue that the diasporic filmmakers in diasporic filmmakers in question, Hung and Panh, question, Hung and Panh, opt for different angles in opt for different angles in responding to this responding to this question. The set of question. The set of TThe he Scent of Green Papaya Scent of Green Papaya iis s constructed in France, constructed in France, many have criticised it as many have criticised it as catering to the “western catering to the “western gaze ” (Yu 2020), an gaze ” (Yu 2020), an exoticised vision of exoticised vision of Vietnam and allegedly Vietnam and allegedly iinauthentic. nauthentic. Rice People Rice People,, on the other hand, filmed on the other hand, filmed on-location with on-location with naturalistic cinematic naturalistic cinematic grammar, offer a much grammar, offer a much less stylised version of the less stylised version of the homeland than Tran. homeland than Tran.

Perhaps authenticity is Perhaps authenticity is the wrong viewpoint. the wrong viewpoint. Perhaps each respective Perhaps each respective viewpoint – Diasporic, viewpoint – Diasporic, Mainland, and Outsider – Mainland, and Outsider –attempts to capture this attempts to capture this colonial history through colonial history through fiction, a fiction that is, fiction, a fiction that is, contrary to its definition, contrary to its definition, a certain truth. If memory a certain truth. If memory is, indeed, fragmented is, indeed, fragmented and subjective, could it and subjective, could it not still be Truth? Could it not still be Truth? Could it not still be History? not still be History?

COULD IT NOT STILL COULD IT NOT STILL BE TRUTH? BE TRUTH?

COULD IT NOT STILL COULD IT NOT STILL BE HISTORY? BE HISTORY?

This profile aims to share a bit about ourselves and our background interests. We want to highlight how these differences shape our experiences when watching the films we studied, including those not featured in this project. Our mediaconsumptionisinfluencedbyouruniqueperspectives andbackgrounds,whichaddsdepthtoouranalysis.

llinh’s inh’s

HAVE YOU HEARD OF OR SEEN ANY OF THESE SIX FILMS? IF SO, IN WHAT CONTEXT?

“I first encountered The Scent of Green Papaya while researching for a film analysis project in my second year. Though the film's environment felt unfamiliar at first, I was captivated by Tran Anh Hung’s masterpiece when I revisited it a year later. Earlier this year, my partner introduced me to Rice People, mentioning that Rithy Panh is often seen as Cambodia’s equivalent to Tran Anh Hung. This conversation sparked a deeper reflection on the diasporic experiences portrayed in both films, especially how audiences from Vietnam might connect with themes of nostalgia, identity, and displacement in their cultural contexts.”

Linh

“Because the films I watch are often limited to the more popular films of the West, I have not seen or heard of any of these films.”

Gabriel

“The Scent of Green Papaya was mentioned to me by Dr. Tess Do, who was explained to me the unfortunate lack of Vietnamese diasporic films and filmmakers The trauma from the colonial and war times resulted in those memories to be buried, in an attempt to prevent oneself from the damage. However, the new generation in their own identity construction, look to restore those lost memories through their diasporic perspective. Tran Anh Hung, to Dr. Tess Do was one of these storytellers, and she wished for more and more diasporic artists to present themselves in restoring the memory of their ancestors and histories. “

Michelle

“After hearing about the premise of the films, I was mainly curious how they were going to keep the audience engaged, as films such as The Scent of Green Papaya does not have a traditional driving plot like Western films often have. Initially, I was expecting there to be a lot of character drama in order to excite the audience, or a lot of depictions of the violence that follows post colonialism. ”

Gabriel

“Since this was the first time I watched these films, I didn’t know much about their context beyond the fact that they were set in Indochina either Vietnam or Cambodia. I was nervous about how the diasporic films would handle portraying the homeland. Would they be able to carry the message and reimagine the homeland authentically, or would they be too stylised, making it difficult for me to recognise or resonate with the characters’ experiences? This concern was especially present for the films about Vietnam, as I’ve often found that when exile filmmakers make films about Vietnam, the depiction feels distant and less connected to the lived reality of the country.“

Linh

“Curious to see how each film seeks to depict violence, if they choose to omit it, considering the postcolonial territories all 6 are set on. I expected more French language/dialogue, but the omnipresence/omniscience of the French Imperial Empire was more subtle, not in an imposing way, but rather lingering and resentful. I also expected the “Outsider” films to represent its events in a melodramatic way, which is true for The Lover as it frames the young girl’s coming-of-age in a nostalgic manner. “ Michelle

HOW HAS YOUR EXPERIENCE IN MOVIE WATCHING CHANGED WITH THIS VIEWING OF DIFFERENT FILMS FROM DRASTIC FILMMAKING

HOW HAS YOUR EXPERIENCE IN MOVIE WATCHING CHANGED WITH THIS VIEWING OF DIFFERENT FILMS FROM DRASTIC FILMMAKING

PERSPECTIVES?

PERSPECTIVES?

“Unless I have studied or researched a historical event thoroughly, it is likely that I will unconsciously remember historical films as factual, disregarding embellishment and heightened atmosphere. While there is power in representations of history in film, I am conscious of this habit and will seek to unlearn my own biases. The varied origins and perspectives of the films, like the method of our publication, is a good starting point to assessing the biases of my own film consumption and has broadened my perspective and my own attitude towards the diversity of voices in cinema.”

Michelle

“Watching these films has made me more aware of my own media consumption. I’ve realised that the most popular or expensive films don’t always provide the most authentic depiction of history or culture. Diasporic films like The Scent of Green Papaya and mainland films like Rice People offer more nuanced portrayals, while outsider films like First They Killed My Father focus on immediate horror This experience has made me more conscious of the filmmaker's perspective and the way stories are shaped by their backgrounds I’ve become more critical on my own consumption and interpretation, knowing how each film is not the entire picture, but just another perspectives.”

Linh

“The films provided an experience that was drastically different to my expectations. The films often show an appreciation and love for the culture and encourage the audience to share this appreciation through the depiction of beautiful landscapes, communities and their devotion to upholding their culture It showed me that there does not have to be spectacle like Hollywood films often have in order to engage the audience, and quieter character driven narratives revolving around culture can work in capturing and keeping my attention Furthermore, the portrayal of culture from the perspectives of diasporic filmmakers also highlighted to me how drastic of a difference the placement of a director can make for the contents of the film and the portrayal of the culture. This has incited me to consider the context of a director’s placement when viewing a film to gain a greater understanding of the film’s intentions and the accuracy of the film’s portrayals.”

Gabriel

“When does a war end? When can I say your name and have it mean only your name and not what you left behind?”

“Ma. You once told me that memory is a choice. But if you were god, you'd know it's a flood.”

“In Vietnamese, the word for missing someone and remembering them is the same: nhớ. Sometimes, when you ask me over the phone, Có nhớ mẹ không? I flinch, thinking you meant, Do you remember me? I miss you more than I remember you.”

LAURA MARKS ELUCIDATES THAT FILM IS NOT STRICTLY AUDIO VISUALLY BOUND, BUT INSTEAD BASED ON THE SPECTATOR’S EXPLORATION OF THEIR OWN SENSE MEMORIES.

This extreme close up shot of the green papaya enables access to other sensory associations, as the fluorescent white papaya, and delicate softness of the seeds connotes the freshness and sweetness of fruit. The invocation of pleasant senses reflects this diasporic filmmakers portrayal of his homeland through a rose tinted lens with a more positive outlook on the blending of cultures that can only occur in a post colonial landscape.

The Lover elicits the senses through evocative voiceover narration that vividly describes the smells of “duck, roast meat, charcoal, fire.” These sensory details transport viewers to a constructed version of colonial Vietnam, inviting them to experience the sights and sounds of a world steeped in exoticism. The emphasis on sensory imagery not only enhances the film's romantic atmosphere but also underscores the foreignness of the perspective being presented

Jean-Jacques Annaud

This slow panning shot in Nostalgia for the Countryside invites the audience to appreciate the landscapes, with the luscious green grass and the mooing of cows in the background associating the scene with the earthy, lightly sweet scent of grass, yet also the uncomfortable rotten smell of cow manure. This contradiction mirrors the director’s position in the mainland, as there is a present appreciation for his Country land like Hung’s film, yet also an acknowledgement of the hardships akin to Panh’s film.

An affective yearning for a community with a collective memory, a longing for continuity in a fragmented world (Boym 2001, 14)

“WHO

IS GOING TO RECOGNISE THE ANTICIPATIONS OF MY YOUTH, MY MOTHER’S GREYING HAIR, MY SISTER’S BROKEN DREAMS, THE SADNESS WITHIN MY VILLAGE?”

Nostalgia for the Countryside (1995)

Dang Nhat Minh

“I’M A DREAMER, I WRITE POETRY, MY THOUGHTS OFTEN WANDER”

Whilst The Scent of Green Papaya and its activation of the senses invites the remembrance of the gentle touch of fruits and the welcoming embrace of nature through the constant chirping of crickets in the background, Rice People tends to use this access to other memories to evoke anxieties and fears that may be present within the audience.

This scene depicting Yong Poeuv’s nightmares about the scorching flames burning their village to a crisp as a result of war aims to recollect such memories. Every audience member knows the agonising sting of a flame, and the overwhelming stench of smoke, which is what the film intends to bring to light in this portrayal of the village being burnt to dust.

Rithy

A River Changes Course powerfully highlights the devastation that modernisation brings to the rural communities of Cambodia. The roar of sewing machines in factories drowns out the gentle sounds of nature, such as the delicate chirps of crickets, symbolising the destructive impact of industrialisation on the locals' way of life

In First They Killed My Father, the warm, murky filter and the overbearing sounds of helicopters evoke an intense sensory experience, triggering discomfort associated with heat and noise. This stylistic choice reflects the foreign director’s reliance on heightened intensity and spectacle, aligning the film with Hollywood's standards of dramatic storytelling.

While this approach effectively immerses the viewer in the chaos and horror of the events, it also highlights the outsider's perspective, where the focus on spectacle can sometimes overshadow the more nuanced, internal experiences of trauma and memory that are often central in diasporic narratives.

W e i n s t r u c t

t h i s : t a k e c a r e

i n c o n s u m i n g

m e d i a , b e

a w a r e o f t h e

a c t o f

e x o t i c i s a t i o n ,

b u t a l s o

r e m e m b e r t h a t

s o m e t i m e s

f i l m m a k e r s

t h e m s e l v e s f a l l

i n t o t h i s

p a t t e r n o f

m e m o r y

c o n s t r u c t i o n .

Diaspora cinema is a tool of memory restoration, reclamation, and rewriting The nature of diaspora is its dispersion: Viet Kieu (Overseas Vietnamese; people of Vietnamese origin that live outside of Vietnam), for example, is one of the diaspora communities of which the publication is concerned. With the largest community residing in the U.S., as the biggest Asian population in France, and of course numerous in our local Naarm (Melbourne) Our digital publication mimics this spread, and the easy access to it by the omniscience of the Internet aids in this process of remembering

While Linh quickly spotted the falseness of The Scent of Green Papaya’ s set, Michelle and Gabriel did not catch on until the three discussed the production of the film Linh, having spent her whole life in Vietnam, was able to point out the visual inconsistencies with her own childhood memories. This fact forced Michelle to rethink the mise-en-scene of the film, critically reframing it as a representation of Hung’s own representation, rather than a realistic Saigon, and the influences of his French diasporic identity The varying levels of engagement with “Indochinese” history and cinema from the creators can be seen as a microcosm of the diversity of spectators each film could have the potential to reach.

Colonisation inevitably influences how we choose what to watch, what is distributed and marketed to us, how we engage with film, and what we gain from them The very act of film consumption is riddled with history and we must reassess this habit. Film does not necessarily need to be an audiovisual medium. Let us recall the fiasco that is the transition from silent cinema to talkies: it was even once revolutionary to think of film as more than a visual medium (Chion, 1993) Furthermore, the textures of a film, too, do not have to be accompanied by 3D glasses, water spraying, wind-blowing mechanisms like 4DX or, in the near future, VR and XR experiences. Rather, we can begin to understand film with a multi-sensorial focus (in a metaphorical sense), and the physicality of touch and objects as demonstrated by our filmography, as a new way of watching

Dr Cristóbal Escobar & Professor Chris Healy