Winter

1

VolumeXIII

2023

ThisworkislicensedundertheCreativeCommons

Attribution-Non-Commercial-NoDerivatives4.0InternationalLicense.

Toviewacopyofthislicense,visithttps://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

TheMcGillJournalofPoliticalStudies(MJPS)ispublishedannuallybythePolitical ScienceStudents'AssociationofMcGillUniversity(PSSA),843rueSherbrookeOuest, Montreal,QCH3A0G4.

ISSN0835-376X

Allassertionsoffactsandstatementsofopinionaresolelythoseoftheauthors. TheydonotnecessarilyrepresenttheviewsoftheEditorialBoard,thePSSA,the ArtsUndergraduateSociety,theStudent'sSocietyofMcGillUniversity,McGill University,oritsfacultyandadministration.

2

3

TableofContents

9:“WalkOutorStaySeated?EvaluatingtheNamingandShaming StrategyofWalkingOutonRussiafortheInvasionofUkraine”

25:“IndigenousElectoralParticipationandNon-Participationin Canada:DefiningTheirIdeologicalDifferencesandtheCasefor Cooperation”

39:“Priests,Politicians,andPandemics:DriversOfCOVID-19 ConspiracyTheoryBeliefInRomania”

61:“State,Society,andRecklessSpending:20thCenturyArgentina’sNear MisswithSuperpowerdom”

74:“IndigenousDataSovereignty:TheCensusasanInstrumentof CanadianDecolonization”

89:“ADefenseofIslamicSectarianism”

108:“TheChallengesofMappingUndocumentedMigration”

119:“Understandingthe“ImpendingClimateDisplacementCrisis” Discourse:ReplacingAlarmistNarrativeswithTechnicalSolutions”

136:“Women’sWork:RisksandOpportunitiesforGenderEqualityin Ghana’sInformalEconomies”

150:“FromObjecttoAuthor:IndigenousPeoplesandInternationalLaw”

4

SubmissionandReviewProcess

TheMcGillJournalofPoliticalStudies(MJPS)acceptsmanuscriptsin eitherFrenchorEnglishfromundergraduatesofanyfacultyormajor. PapersmusthavebeenwrittenforaPoliticalSciencecourseatthe 300-leveloraboveandmusthavereceivedaminimumgradeof80% (A-)inthecourse.Selectedmanuscriptscontaincoherentandwellstructuredarguments,goodgrammar,andstrongsyntax.original analysisanduniqueperspectivesonrelevanttopicsinpoliticalscience andcurrentaffairsdistinguishselectedpapersassomeofthebestthat undergraduatestudentshavewrittenatMcGillUniversity.

ManuscriptsareacceptedthroughouttheFallandWintersemestersin multiplesubmissionrounds.Allmanuscriptsenteradouble-blind reviewprocess.Authors'namesarewithheldwhileananonymous teamofpeerreviewersanalyzesandcritiqueseachpaper.TheEditorial Boardthenconvenestoreviewtheanonymouspeerreviewfeedback andselectthestrongestmanuscriptsforthejournal.Atthistime,each editorispairedwithanauthorforarevisionphasetopreparethe manuscriptsforpublication.

TheJournalisastudent-runenterprisewithanEditorialBoard consistingofundergraduatestudentsatMcGillUniversity.

5

EditorialBoard

Editor-in-Chief

MatthewMolinaro

ManagingEditor

EmilySegal

DirectorofPeerReviewers

JulietMorrison

Editors

CatrionaArnott

RitaBroberg

HannahClarke-Andrews

JulienDuffy

CateyFifield

AmeliaFortier

LilyMason

ChloeMerritt

JeremyRotenberg

6

WordsfromtheEditor-in-Chief

Witheveryyearthatcomes,themembersoftheMcGillJournalof PoliticalStudiesPrintaskthemselves:whatcanwedoforpolitical scienceandhowcanthedisciplineitselfinviteopendialogue, exchange,andcuriosityintothenatureofpower,policy,andpolitics. TheundergraduatePoliticalSciencecommunityatMcGillresponds withunmatchedgrace,precision,andrigour,makinginturnour responsibilitiesaseditorschallenging,relational,anddynamic.Theten papersfoundinthisjournalpushtheboundariesofpoliticaltheory, Indigenouspolitics,comparativepolitics,andinternationalrelations, eachconstitutingaresponse,atimelyreminderfortheneedforclose attentionandlisteningtothemanysourcesthatmakeupourpolitics.

IhopeyouenjoyreadingthesefantasticpiecesasmuchasIhaveand lookatpoliticalsciencewithadifferentlens.

Thisjournalwouldnothavebeenpossiblewithout,aboveallelse,the hardworkandsupportoftheEditorialBoardandourteamofpeer reviewers.Theeditorsprovedthemselvestobedeeplyinvestedina mindfulandinterdisciplinaryapproachtothestudyofpolitics.I’dlike tothankthemindividually.

MythankstoLily,alsoaBSNcomrade,forhercriticaleyetodetailand brillianceacrossmultiplepoliticalspaces;Catey,forbringingher outstandingcopyeditingskillsandhercuriositiesfrompublishingto ourpaper;Hannah,forworkingacrosstimezonesonherexchange, anddoingsoflawlessly;Rita,afellowEnglishliteratureandpolitical sciencestudentandclassmatewhobreathesprofessionalismandsharp editingintopieces;Jeremy,forhiskeennessforpolicyimplementation

7

thatradiatesandhisgenerouscontributionstooureditorial discussions;Catriona,afellowOakvillian,forhercompassionandcare forthefieldandforthepeoplewhomakeit;Julien,forwritingoneof thebestwritingsamplesaneditorhaseversubmitted,atestamenthe embodiestohowgreatwritingandeditinggohand-in-hand;Amelia, forthinkingwiththemanyhistoricalvoicesthatshapepoliticsand doingsoacrossdisciplines;andChloeMerritt,forchoosingtodelve intotheeditingsideafterwritingoneofthestrongestpaperslastyear, twoyearsinarow,shehasbeenakeycollaboratorinourmoveto unbindtherelationshipofIndigenouspoliticstothesubgroupof Canadianpolitics.

I’dliketoextendmydeepestgratitudetoJulietMorrison,Directorof PeerReviewers,forcoordinatingsuchalargeteamwithease.I’dliketo sayamassive,massivethankyoutomyManagingEditorEmilySegal. JulietandEmilywerejoystoworkwith,andrepresenttomeintheir futureendeavoursasArtsSenatorandanincominglawstudent respectivelythekindsofjournalists,policymakers,andlawyersweneed inthefuture. Icouldnothavecompletedthisprojectwithouttheir supportandextensivecontributions.

Finally,IwouldliketothankmypredecessorKennedyMcKee-Braide. NowalawstudentatMcGill,Kennedyhastakentimeoutofherbusy yeartoinformallymentormethroughoutthisprocess.Shemodels howapoliticsofhope,socialchange,andfreedomcanstructurealife andmakeusthinkdifferently,collectively.Inall,Icouldnotbemore honouredtohavehadtheopportunitytoleadthejournalthisyear.

MatthewMolinaro Editor-in-Chief McGillJournalofPoliticalStudiesPrint,Volume

8

XIII

WalkOutorStaySeated?EvaluatingtheNamingand ShamingStrategyofWalkingOutonRussiaforthe InvasionofUkraine

KiranBasra

EditedbyRitaBroberg

KiranBasra

EditedbyRitaBroberg

9

OnFebruary28th,2022,Russialaunchedafull-scaleinvasionofUkraine topreventNATOfromgainingafootholdintheEast.Sincethen,tensof thousandsofcasualtieshavebeenreported,sparkingEurope’slargestrefugee crisissincetheSecondWorldWarwithnearlyeightmillionUkrainiansbeing displacedthusfar(UNHCR2022).Russia’sunlawfulinvasionofUkrainehas violatedseveralinternationalhumanrightslaws,includingjusadbellum,and Article2(4)oftheUNCharter.Theseviolationsofinternationallawincludethe righttolife,therighttoliberty,therighttosecurity,therighttosovereignty, genocide,warofaggression,andwarcrimes,amongothers.Thispaperwillopen withanextensiveliteraturereviewthatexplainshowwalkoutsareaformof namingandshamingthatcanbeaneffective,ineffective,andcounterproductive strategyofenforcingcompliance.Next,thispaperwillanalyzethespecific consequencesofconductingwalkoutsagainstRussiafortheinvasionofUkraine, concludingthatalthoughwalkoutsmaybeineffectiveduetotheRussian government’sinsulationfromdomesticpressure,orevencounterproductive,by threateningthepurposeofdiplomacy,failingtotakenotes,andinspiring backlashfromtheKremlin,walkoutscanalsobeeffectivebecauseRussiacares aboutprotectingitspublicimagefrominternationalscrutiny.Duetothese factors,staterepresentativesshouldcontinuewalkingoutagainstRussiabecause theargumentsforineffectivenessandcounterproductivitycanbemitigatedand outweighed,andtheinternationalcommunityhasaresponsibilitytopressure falsepositivestateslikeRussiaintocompliance. Russia’sdisregardforhumanrightslawhassparkedwidespread condemnationfromtheinternationalcommunity.Asaresult,stateshave implementedforeignpolicyinitiativestoexpresstheirdisapproval.Forexample, stateshaveappliedindividualsanctionsbyfreezingassetsandbanningthetravel ofRussianleaders(Funakoshietal.2022).Otherstateshaveexercisedmaterial sanctionsagainstRussia’seconomy,transportation,energy,anddefencesectors (EuropeanCouncil2022).Unlikestates,diplomatscannotleveragehardpower totargetdissidents.Instead,theymustrelyonsoftpowertoinfluencestate behaviourandforceacountrybackintocompliancewithinternationallaw.A recentsoft-powerstrategythatdiplomatshaveusedtocondemnRussia’s invasionofUkraineisawalkout,wherestatescoordinatetheirbehaviourby exitingacommissiontoexpressdisapprovalduringRussianinterventionsin multilateralforums.Walkoutshaveoccurredinseveralhigh-levelconferences overthepastyear,rangingfromtheUnitedNationsGeneralAssemblyandthe G20,totheAsia-PacificEconomicCooperationandtheUnitedNationsHuman RightsCouncil.

WhileworkingforthePermanentMissionofCanadatotheUnited NationsOfficeonDrugsandCrime,IparticipatedinawalkoutagainstRussia

Introduction

10

duringthe31stCommissiononCrimePreventionandCriminalJustice.During Russia’sintervention,thestaterepresentativepropagatedfalseclaimsthat Ukrainewastrainingcybercriminalsandemulatingneo-Nazismthroughthe supportofseveralotherWesternstates,includingtheUnitedStates,theUnited Kingdom,France,andtheNetherlands.Theseinflammatoryremarkstriggereda coordinatedresponsefromUkrainianallieswhocollectivelyexitedtheroom duringRussia’sintervention.Afterthewalkout,alldelegatesreturnedtothe conferenceroomandcontinuednegotiations.Thismademewonder,are walkoutsameaningfulformofenforcinghumanrightslawbynamingand shamingcountriesintocompliance?DowalkoutsagainstRussialeadtogreater harmsorbenefitsinmultilateralforums?Shouldstaterepresentativescontinue walkingoutonRussia?

Thispaperwillarguethatwalkoutsareaformofnamingandshaming becausetheyfollowasimilarstructureofidentifyingandcondemningatarget statetoachievethesamegoalofenforcingcompliancewithhumanrights treaties.AlthoughwalkoutsmaybeineffectivebecauseoftheKremlin’s immunitytodomesticpressure,andcounterproductivebyinspiringbacklash whichimpedesthecreationofinternationallaw,contradictsthepurposeof diplomacy,andfailstorecordtheintervention,Iarguethatwalkoutsare ultimatelyaneffectivemechanismofenforcinghumanrightslawbecausethey offeranaccessibleandlow-coststrategyofcollectivesolidarity,spark internationaldiscussionthroughthemedia,andprovidethemostefficient responsetoRussia’sinflammatoryinterventions.Inordertomakewalkouts moreeffective,staterepresentativesmustcoordinatebehaviourthrough identifiabletriggerwords,exerciseinstitution-specificdiscretionwhendeciding whethertoconductawalkout,andselectivelychoosewhentoimplementthis strategytoavoidde-sensitizingRussiatoitseffects.

LiteratureReview

Namingandshamingisapopularenforcementmechanismthat diplomatsusetopressuredissidentstatesintocompliance.AccordingtoCarraro etal.,namingandshamingtypicallyinvolvesthreeactors:“theagentsofshaming (whoshames),thetargetsofshaming(thosebeingshamed)andtheaudience (whichamplifiesthesocialpressureonthetarget)”(2019,337).Theagentsname thetargetandthenshamethemthroughavarietyofmethodsincludingpublic condemnation,boycotts,orstagingaprotest.Thehopeisthatthepressurestates feelfrombeingshamedwillreflectnegativelyupontheirimage,leadingto reputationalcoststhatdeterothercountriesfromformingpartnershipsor grantingbenefitstothedissidentstateinthefuture.Namingandshamingis 11

thereforeconductedwiththeexpectationthatthesocialdiscomfortofbeing reprimandedwillforcethedissidentstatebackintocompliance(Carraroetal. 2019,337).

Walkoutsareaformofnamingandshamingbecausetheyfollowasimilar structuretoachievethesamegoalofenforcingstatecompliance.Inalignment withCarraroetal.’striangularrelationshipofnamingandshaming,walkouts involveagents(thosewhowalkout),targets(thosebeingwalkedouton),andan audience(thepublic,themedia,othersintheroomduringthewalkout,andso forth).Despitetypicallybeingconductedinsilence,walkingoutonadelegate whiletheyarespeakingclearlynamesthecountrybeingreprimanded,and shamesthembydemonstratingthattheyarenotworthlisteningto.In comparisonwithotherformsofnamingandshamingwhichverballyexpress statecondemnation,silentwalkoutscanbeunclearaboutthebehaviourthatis beingreprimanded.Toresolvethistension,manycountriespublishawritten statementfollowingtheirwalkouttoexplainthemotivationfortheirbehaviour. Thereismuchdebateaboutwhethernamingandshamingisaneffective strategyinenforcingcompliancewithinternationalhumanrightslaw.According toAusderan,namingandshamingiseffectivebecauseitcreatesdomestic pressureagainstthedissidentstatebyenforcingpublicaccountability.Whena citizen’scountryisshamedbytheinternationalcommunityforhumanrights violations,theywillperceivethehumanrightsconditionsintheircountrymore negativelyandwithgreaterscrutiny(Ausderan2014,83).Therefore,namingand shamingmaybeaneffectivetoolinmobilizingdomesticpressureagainsta dissidentstate.However,thisstrategycanalsobackfire.Citizenswhowitness internationalshamingagainsttheircountrymaystrengthentheirloyaltytowards theirgovernmentwhenconfrontedwithinformationthatrunscountertotheir predisposedbeliefs(Ausderan2014,83).Thisoperatessimilartotherally aroundtheflageffectwherecitizenswhoholdtheirgovernmentinhighesteem mayincreasetheirsupportforthemwhentheircountryisbeingcriticizedbythe internationalcommunity.Therefore,namingandshamingmaybe counterproductiveinmobilizingastate’sdomesticpopulation,asitrisks bolsteringsupportforthedissidentgovernment.

Namingandshamingcanalsobeeffectiveatenforcingcompliance becauseitshinesapowerfulspotlightonhumanrightsviolatorswhoareeagerto escapecentrestage.Hafner-Burtonarguesthattoavoidthisattention, governmentsoftendecreasehumanrightsviolationsafterbeingcalledoutin ordertominimizeinternationalpressure:“governmentsnamedandshamedas humanrightsviolatorsoftenimproveprotectionsforpoliticalrightsafterbeing publiclycriticized”(Hafner-Burton2008,690-691).Gallagherarguesthatthisis aparticularlyhelpfultoolinframingperpetratorsasuntrustworthypartnersto publiclysignalinternationaldisapprovaltoalliesandpreventdissidentstates from

12

formingprofitableagreementsinthefuture(2021,5).Thehopeisthatby exposingthesehumanrightsabuses,themoralcredibilityofthedissident countrywillbesubjecttointensescrutiny,forcingactorstotakeastand (Gallagher2021,5).Thiscanleadtomaterialdrawbacksforthedissident countryasotherpartiesbegintoexcludethemfromeconomicagreementsand tradepartnerships.Studieshavefoundthatnamingandshamingcansignificantly reduceforeigndirectinvestmentreceivedbyrepressivestates,including restrictingaccesstoportfolioinvestmentsandarmsexports(DeMerittand Conrad2019,130).Thus,namingandshamingcanbeaneffectivetool, especiallyforcountriesthatarevulnerabletoexternalpressureandrelyon internationalpartnerships.Despitetheseconvincingarguments,theeffectiveness ofharmingastate’sreputationthroughnamingandshamingissubjecttotheir relationalpower.ItmaybeeasytoconvinceotherstatestoexcludeMyanmaror NorthKoreafromtradeagreementsascountriesgenerallydonotrelyontheir exports,butitwillcertainlybemorechallengingtopersuadestatestorefuse tradedealswithcountrieslikeChinaandSaudiArabia,whoareresponsiblefor someoftheworld’smostvaluableexports.Therefore,theeffectivenessofnaming andshaminginelicitingreputationalcoststhatdeterfuturepartnershipswith othercountriesissubjecttothevalueofapartnershipwiththedissidentstate. ThisconnectstoApodaca’sargumentthat,whilenamingandshamingisan inexpensivealternativetoenforcementmechanismslikeeconomicsanctionsor militaryaid,itstillincurssocialcosts.Innamingandshamingatargetstate, nationswhorelyonarelationshipwiththatcountrywilldamagetheirprospect ofcontinuinganalliancewiththeminthefuture(2020).Forexample,smaller statesthatdependonthetargetcountryforanexportmayfacegreatertariffsif theychoosetoparticipateinthewalkout.Alternatively,statesthatrequire supportfromthetargetstateinmultilateralnegotiationsmayriskjeopardizing theirpartnershipinfuturediplomaticforums.WhileApodacaraisesalegitimate riskassociatedwithnamingandshaming,countriesthatdonotnameandshame mayfacesimilarorgreaterrepercussionsfromthestateswhodochoosetoname andshame,placinganultimatumbetweenwhicheverpartyhasthepowerto implementthemostsevererepercussions.Sincetherearemoreagentsthan targetsinawalkout,astatewilllikelyfacethegreatestharmfromsidingwiththe agent.Therefore,whiletherearecostsassociatedwithparticipatinginwalkouts asApodacatheorizes,theremaybegreaterrepercussionsinvolvedinfailingto walkout,incentivizingstatestojointhepackinnamingandshamingthetarget nation.

Namingandshamingcanalsobeineffectivebecauseasviolationsreduce inonearea,theymayriseinanother,leadingtoabalancingeffect.DeMerittand Conradcallthisrepressionsubstitution,aprocesswherethe“shamingofone physicalintegrityviolationisjointlyassociatedwithdecreasesinthatviolation andincreasesinotherviolationsofhumanrights”(2019,129).Examplesofthis

13

includefindingsthatshamingacountryforpoliticalimprisonmentincreasesthe probabilitythatthestatewillreducethefrequencyofpoliticalimprisonment whilesubsequentlyincreasingtherateofextrajudicialkillings,torture,and/or disappearances(DeMerittandConrad2019,142).Asaresult,thebenefitsofa statecomplyingwithapreviouslyviolatedhumanrightbecomeneutralizedas thestatebeginstoviolateadifferenthumanright,callingintoquestionthe efficacyofnamingandshaming.WhileDeMerittandConradoffervaluable insightintothepossibilityofrepressionsubstitution,itisquestionablewhethera decreaseinoneviolationandanincreaseinanotheralwaysleadstoanequally balancedeffect.Manytradeoffsthatresultfromnamingandshamingreplacethe frequencyofasignificanthumanrightwithalessimportantone.Forexample, namingandshamingleadssomestatestoreducetheirfrequencyofgenocidefor ethnicminoritieswhileincreasingtheirrateofimprisonmentforthesamegroup. Althoughstillresponsibleforcommittingahumanrightsviolation,inthiscase, namingandshaminghasreapedanetbenefitbysavingthelivesofmanyethnic minorities.Therefore,repressionsubstitutionneednotalwaysbeineffective,asit mayreplaceaserioushumanrightsabusewithalessharmfulviolation. Beyondineffectiveness,namingandshamingcanalsoproduce counterproductiveconsequencesbyincentivizingthedissidentstatetoviolate morehumanrightsoutofbacklash.AccordingtoSnyder,respondingtoshame withdissidenceisanaturalpsychologicalresponsebecauseshametriggersa “self-reinforcingsyndromeofanger,resentment,evasion,andglorificationof deviance”(2020,645).Thus,Snyderarguesthat“shamingismostlikelyto mobilizeintenseformsofbacklash”whichmanifestinmanydifferentforms (2020,645).

OneformofbacklashthatSnyderfindsviolatorsregularlyengageinisthe restrictionofspaceforcompromiseandbargaining(2020,645).Thisisespecially dangerousinmultilateralpoliticalforums,wherediplomaticwalkoutsoccur, becausestatesusethesespacestoreachaconsensusaboutinternationallaw. GallagheragreeswithSnyder,arguingthatbacklashcanproduceramificationsat theinternationallevel,whichcould“jeopardizeinternationalsociety’scapacityto dealwithhumanrightsviolationselsewhereintheworld”(2021,9).For example,thisbacklashcouldresultinthetargetcountrywithdrawingvoluntary fundsfromanorganizationorrefrainingfromsigningatreatythatisbeing drafted.WhileGallagherandSnyderposelegitimatethreats,itseemsequally dangeroustoallowacountrythatactivelyviolatesthevaluesofaninternational organizationtoalsoparticipateinit.ThissentimentwasechoedbyYevheniia Filipenko,thePermanentRepresentativeofUkrainetotheUnitedNations,after walkingoutonRussiaintheUNGeneralAssembly,whereshenotedthatthe UnitedNationsmuststepupandfulfillitsduty,asRussiaisviolatingtheUN Charterandits

14

membersthroughitspresenceandcontributions(GuardianNews2022).Thus, therestrictionofspacefordissidentstatesinpoliticalforumsmaynotbeas harmfulasSnyderandGallagherclaim,asitmaybemoredamagingtoallowthe participationofanactiveviolator.

Anothercounterproductiveconsequenceofnamingandshamingisthe backfireeffectofstatesincreasingviolationsofthehumanrighttheyarebeing shamedfor,orotherhumanrights.DiBlasiarguesthatcountriesaremorelikely tocreatepro-governmentmilitiasafterbeingnamedandshamedforahuman rightsabusebytheinternationalcommunity(2020,907).Therefore,namingand shamingmaybeharmfulbecauseittriggershostilityfromthetargetcountry, whichcausesthestatetofurtherincreaseviolationsofthathumanrightorother humanrightsoutofbacklash.

Despitetheharmsandbenefits,conductedcorrectly,namingandshaming canbeaneffectivemechanismofenforcingcompliancewithhumanrightslaw. Sohowshouldcountriesnameandshame?Wongarguesthatdiplomatsdonot usuallyexpresstheirdissatisfaction,thusanallywhoistypicallycollegialbut becomesupsetsymbolizestheimportanceofthattopictothecountryand informsotherleaders’expectationsoftheirbehaviour(2020,83).Therefore, namingandshamingismosteffectivewhenitisconductedsparingly.If conductedtoofrequently,namingandshamingcannormalizeanddesensitize theimplicationsofawalkoutforthetargetstate.Moreover,BatesandLaBrecque arguethatnamingandshamingismosteffectivewhenconductedcollectively (2020).Thus,mechanismsmustbeinstalledtoensurethatallparticipating partiesareclearonwhenawalkoutisbeingconducted,toensurethata co-ordinatedandcollectiveresponseisimplemented.

CaseStudy:WalkingOutonRussiafortheInvasionofUkraine

BaseduponCarraroetal.’sdefinitionofthetriangularrelationship involvedinnamingandshaming,thecaseofwalkingoutonRussiadisplaysthe followingactors:statedelegates,whoaretheagentsofshaming,Russia,whois thetargetofshaming,andtheaudience,whichisacombinationofthemedia, citizens,internationalorganizations,andotherstates.Themediaservesasan audiencebecauseitpublishesreportsonstaterepresentativeswhowalkouton Russia.Thesereportseducatethepublicandsparkconversationsonwhetherthis isanappropriateandeffectivediplomaticresponsetotheinvasionofUkraine. Internationalorganizations,liketheUnitedNations,serveasanaudienceby observingwalkoutsandlearninghowtomediatethenegotiationsmoving forward.Otherstatesalsoformanaudiencebecausetheycanlearntoemulate walkoutbehaviourbynamingandshamingRussiainotherpoliticalforums. WalkingoutonRussiaisaformofnamingandshamingbecause

15

countriesabandonsessionsduringRussia’sinterventionstodisplaytheir condemnationofthedissidentstate’sbehaviour.Thewalkoutsconducted againstRussiaareframedbythemediaaccordingtonamingandshaming principleswithsensationalarticletitlessuchas“EmbarrassedatUN;Over100 diplomatswalkoutinprotestduringMinister’sspeech”(HindustanTimes).This mediaattentionframeswalkoutbehaviourasatoolusedbydiplomatstoname andshameRussiabackintocompliancewithinternationalhumanrightslaw. Namingandshamingisaneffectivetoolbecauseitdamagesacountry’s reputation,forcingthembackintocompliancetoprotecttheirimage.Asaresult, ifacountrydoesnotcareaboutitsreputation,namingandshamingmaybean ineffectivestrategyinpunishingdissidence.Toevaluateifwalkingoutisan effectivemechanism,itisthusimperativetodeterminewhetherRussiacares aboutitspublicimage.Manyarguethatacountryaspowerfulanddissidentas Russiaisunphasedbyshamingtechniques.Afterall,Russiahasfacedsevere criticismfordecadesinresponsetoavarietyofhumanrightsviolationswithin theirownbordersfortheirtreatmentofracialminoritiesandmembersofthe LGBTQ+community,andoutsidetheirbordersfortheirviolationsof internationalhumanitarianlawintheFirstandSecondWorldWar,theCold War,theFirstandSecondChechenWar,theinvasionofAfghanistan,the interventioninCrimea,andmanyothers.Asaresult,somescholarsarguethat Russiahasbecomenormalizedtothislevelofostracizationandcondemnation fromtheinternationalcommunity,andthusnamingandshamingwillnotreap significantprogress.

However,thisperspectiveismisguided,asitisevidentthatRussia continuestocareaboutitspublicimage,despitefacingconsistentbacklashfrom otherstates.Afterall,thisiswhyRussianrepresentativesaredesperatelytryingto advancethefalseclaimthattheinvasionofUkrainewasactuallyamilitary interventiontoprotectcitizensandendthe“genocideoftheRussian-speaking populationbytheNazigovernmentofVolodymyrZelenskyy”(Fortuin2020, 314);Russia,aconsistentviolatorintheinternationalcommunity,doesnotwant tobeseenasahumanrightsabusingstate,despitetheirwillingnesstocontinue committingatrocities.Asaresult,Russiaclearlyfeelsthepressuretoconform. Thus,walkingoutmaybeaneffectivemechanismtoforceRussiabackinto compliancewithinternationalhumanrightslaw.

ThereareseveralreasonswhywalkingoutagainstRussiaisaneffective strategy.First,walkoutsareanaccessibleandlow-costmethodofsupporting Ukraineasallthatisrequirediscoordinationbetweenmemberstates.Therefore, walkoutsareaneasywayforsmallercountriestoexpresssolidarityand condemnation,especiallyiftheycannotaffordmoreexpensivedemandslike sendingtroopsorimposingsanctions.Acollectiveresponsetotheinvasionof UkraineisimperativetointernationallycondemningRussia,butitisunrealistic

16

tothinkallcountriescanactwithsimilarmeans.Thus,walkoutsprovidea mechanismforeverycountrytocollectivelysupportUkraine.

Second,becausewalkoutsarerareandcontroversial,theyreceive significantmediaattentionandareheavilypublicizedinthenews,sparkingan importantdiscussionfromthepublicandvaluedstakeholders.This conversation,coupledwiththefactthatthisresponseisanaccessibleand low-coststrategy,caninspiremanyaroundtheworldtoparticipateinsimilar walkoutsandboycotts,suchasbynotattendingRussiansportingcompetitions orrefrainingfrombuyingproductssoldbypubliclyownedRussiancompanies. Unlikematerialsanctionsormilitaryaid,walkoutsareastrategythatcanbe easilyreplicatedbycitizens.Thus,walkoutsgobeyondthediplomaticforumto affectpeopleinreallifeandsparkamassmovement.

Third,walkingoutisthemostefficientmechanismofrespondingto Russia’sinflammatoryinterventions.WhenRussiamakesaninterventionthat propagatesfalseclaims,countrieshavetwooptions:tostaysilentorspeakup. TheseinflammatoryremarksdispelinaccurateinformationbyequatingWestern countrieswithneo-Nazism,andarguingthattheinvasionofUkraineisjustified duetothehumanrightsabusescommittedbytheUkrainiangovernmenton theirownpeople.Therefore,choosingtoignoreRussia’sinappropriate interventionsisdangerousbecauseitcondonesstatementsthatwouldreap harmfulrepercussionsformanystatesinvolved.Ontheotherhand,ifstates choosetorespondtothesestatements,doingsowouldtriggerRussiatouseits rightofreply,whichwouldseverelyderailtheconversationintoabackandforth betweenRussiaandopposingstates.Thiswoulddistractthecommitteefromits mainfocusofcreatinghumanrightslaw,andvanquishthegreatergoalof protectingvulnerableminorities.Inlightofthesetwoill-fatedresponses,walking outintroducesathirdoptionwhichsendsanequallystrongmessagewithout elicitingadistractionfromtheconversationathand.Notonlydowalkouts expresscleardisapprovalofthefactitiousstatements,theyalsoallowthe committeetostayontask.ThisisbecauseRussiandelegatescannotusetheir rightofreplyagainstawalkoutliketheycanwithaninappropriateintervention, thuslimitingtheopportunityforarightofreplyface-offwhichwillderailthe conversation.Therefore,walkoutsintroduceathird,moreeffectiveresponseto Russia’sinflammatoryandfactitiousremarks.

Despitetheaforementionedbenefitsofconductingwalkouts,thisstrategy maybeineffectiveinthecaseofRussiaduetotheauthoritariannatureofthe Kremlinwhichhasmadethegovernmentimmunetodomesticpressure.Despite countlessRussiancitizensbravelyprotestingVladimirPutin’sinvasionof Ukraine,domesticpressurehasyettoreapsignificantprogressinendingthe intervention.EvenifwalkingoutonRussiadidcreatedomesticpressureagainst thedissidentstateasAusderantheorizes,itisunlikelythatthis

internal 17

accountabilityisenoughpressuretoincentivizeRussiatopulloutofUkraine andtakeresponsibilityforitsinternationalhumanrightsviolations.Therefore, relyingondomesticaccountabilitymechanismstotriggerRussia’scompliance maybefutile.

Beyondineffectiveness,conductingwalkoutsagainstRussiamaybe counterproductivebysparkingbacklashfromtheKremlin.Forexample,naming andshamingcouldleadtostagnancyinthepoliticalforum.Inmultilateral committeeswhereinternationallawisbeingdrafted,countriesaresearchingfor consensussothatallpartiescanagreetocomplyingwiththerecommendationsof atreaty.ItisthereforedangeroustowalkoutagainstRussiabecausethishostility coulddeterMoscowfrommovingforwardwiththenegotiations,orfrom signingthetreatyatall.ThisisespeciallysignificantconsideringthatRussiais oneofthegreatestviolatorsofhumanrights,therefore,itisimperativetoinclude theminmultilateralconversationssotheycancontributetoatreatythatthey willcomplywith.

Furthermore,namingandshamingRussiamaybecounterproductiveas walkingoutonadelegatecontradictstheverypurposeofdiplomacy.Diplomacy representsaspaceforconversationandcompromise-thispromiseiswhat incentivizesstatesofalldifferentideologiestoparticipateinthecreationof internationaltreaties.Thispromiseisbrokenwhenstatesdonotletothersspeak, orsendthemessagethattheyrefusetolisten.Exitingtheroomduringastate’s interventionsymbolizesthatthecountryspeakingisnotworthyofparticipation inthatpoliticalforum.Thiscanleadtoaslipperyslopebydeterringthestate fromparticipatinginthatparticularcommitteeorothermultilateralforumsin thefuture.LosingRussia’sdiplomaticpresencewouldjeopardizethe internationalcommunity’sabilitytoformpeacefulagreements.IfRussia abandonsmultilateralforumsmoredangerousresponsesandreactionswilllikely replacediplomacy,suchasbargainingandswaggering.Therefore,walkingouton Russiamayjeopardizetheinternationalcommunity’sabilitytoreach compromisesoninternationallawbyexcludingakeyactorfromtheprocessof draftinglegislationandcontributingtohumanrightspolicies. Lastly,andoftenignored,whencountrieswalkouttheyeliminatetheir opportunitytorecordtheinterventionmade.Capitalsrelyontheirdiplomatsto takedetailednotesasmanymultilateralforumsarenotvisuallyoraudibly recorded.MostforumsrelyontheChairtomakenotesontheimportant recommendationsthatstatesmake,whichtheyaddtothedraftingofthe legislation.Walkingoutofthecommissionjeopardizesthechanceforstatesto collecttheirownnotesonRussia’sintervention,whichrisksnormalizing inflammatoryremarksthattheirdelegateswillnotbeabletorespondto. Therefore,walkoutsmaybeineffectiveastheyincreasetheriskoflegitimizing Russia’sfactitiousinterventionsandpreventstatesfromrecordingimportant contributionsandrespondingappropriately.

18

ShouldwalkoutsonRussiacontinue,andifso,how?

Todeterminewhetherwalkingoutisaneffectivemechanismofenforcing compliance,wecanexplorewhetherthebenefitsofnamingandshamingRussia outweightheineffectiveandcounterproductiveoutcomespreviouslydescribed. Perhapsthestrongestresponserefutingtheefficacyofwalkoutsistheriskthat namingandshamingRussiamayleadthedissidentstatetorefusefurther participationinthecreationofahumanrightstreaty.However,despitereceiving criticismforbeingoneoftheworsthumanrightsabusersintheinternational community,Russiacontinuestoparticipateinthedraftingofhumanrights treaties.ThishypocriticalperspectiveisexplainedbyBethSimmons,whoargues thatcountrieslikeRussiawhoratifyhumanrightstreatiesdespitehavingno sincereintentionofcomplyingwithitsrecommendations,arefalsepositivestates (2009,77).Russiahasfacedmuchstrongercondemnationforcommitting humanrightsviolationsthannamingandshaming.TheKremlinhasbeen subjecttoeconomicsanctions,publiccondemnation,militaryintervention,and thebreakingofalliances,yetRussiacontinuestoattendmultilateralhuman rightsforumsandcontributetointernationaltreaties.IfRussiaisalreadywilling toparticipateinthetreatyprocess,whichinvolvesasubstantialinvestmentof time,energy,andresources,Moscowisunlikelytobedeterredfromcontinuing negotiationsbecausecountrieschoosetoexittheroomwhiletheyarespeaking. Inresponsetotheargumentthatwalkoutscontradictdiplomacy,itis morelikelythatthealternative,speakinguporstayingsilent,risksevengreater harm.Speakingupinitiatesarightofreplybattlewhichderailstheconversation anddoesnotallowmemberstatestoefficientlyfocusonthetaskathand: formulatinglawtoprotectvulnerableminoritiesfromhumanrightsviolations. Ontheotherhand,stayingsilentlegitimizestheinflammatoryremarks propagatedbyRussia,which,duetotheirfactitiousnature,canleadtogreater harm.Moreover,diplomacyshouldbeaspaceforactorscommittedtothevalues ofdiplomacy.Thus,statesshouldnotbeallowedtoparticipateinthecreationof humanrightstreatiesiftheyarecurrentlybreakingtheverylawstheystriveto implement.

Third,whilethefailuretorecordRussia’sinterventionduringawalkout posesanimportantproblem,itcaneasilybesolvedwiththerightsolution.Many conferencesarealreadylivestreamed,makingthemeasytorecord.Moreover,the internationalorganizationcanhirenote-takerstoassisttheChairandnotifyall statesaboutwhatwaspreviouslysaid.Regardlessofwhetherornotwalkoutsare beingconducted,thetranscribingoftheseimportantpoliticalforumsis imperative.Implementingthissolutionwouldnotonlyalleviateariskassociated withconductingwalkouts,butitwillalsoprovidestaterepresentativesand internationalorganizationswiththeresourcestheyneedtoensurefull

19

understandingandtransparencyovertheconversationandhavemorefruitful communicationthatisnotburdenedbyafailuretoremember. Thus,consideringtherisksofwalkoutscanbesolvedoroutweighed,why isitintheinterestoftheinternationalcommunitytocontinuethisstrategy?In ordertofostergreatercompliancewithhumanrights,statesmuststrivetoturn falsepositivesintosincereratifiers,countriesthatbelieveinthetreaty’spurpose andintendtocomplywithitsrecommendations(Simmons2009,354).False positivesactastheydobecauseitiseasyforthemtonotgetcaughtcheatingand eveniftheyarecaughtthemechanismsinplaceareweakenoughthattheywill notfacesignificantconsequences.Namingandshamingcanthereforeholdfalse positiveslikeRussiaaccountable,sothattheycanreceiveproportionalharmto deterfutureviolations.

Howcancountriesbecomemoreeffectiveatwalkingout?Therearethree keymethodsthatstatescanimplementtoconducthigherqualitywalkouts.First, countriesmustestablishacoordinatedresponseaboutwhenandhowtoact.The mosteffectivewalkoutsareconductedwhenthereisacollectiveandunified responsewhichsendsaclearmessageforwhytheactionisbeingconductedand whoitisbeingconductedagainst.Thiscanbedonebyusingtriggerwords, whereagroupoflikemindedcountriesdecideinadvancewhichwordswillcause thegrouptoabandonthecommissionduringanintervention.Inthecaseof Russiawalkouts,thesetriggerwordscanincludemessagesthatrefertotheWest asneo-NazisorimplythatUkraineiscommittinggenocideagainstitsown people.Triggerwordsareaneasyandclearmechanismofestablishingwhento walkoutandwhentostayintheroom,allowingallcountriestooperate consistently.Triggerwordsarealsoimportantbecausetheyactasamechanismof factcheckingRussia’sstatementsandensuringthatMoscowisreprimandedfor spreadingfalseinformation.

Second,walkoutsshouldbespecifictotheorganizationthattheyare beingconductedin.Someorganizationsarenotconducivetoawalkout,suchas theUNSecurityCouncil,whereaprotestcouldinspireunwantedconsequences fromvetomemberslikeanunwarrantedmilitaryresponse.Similarly,inabody liketheUNOfficeonDrugsandCrimeswhereconsensusisusedtopass internationallaw,conductingawalkoutmayriskjeopardizingthecreationofa treaty.Inotherinternationalorganizations,especiallythosewherehumanrights arethemainareaoffocussuchastheUNHumanRightsCouncil,awalkout maybetheperfectstrategytoexpresscondemnationofRussiawithoutthe politicalrepercussionsembeddedinotherinstitutions.

Third,walkoutsshouldbeconductedsparinglyandintentionally.If conductedtoofrequently,walkoutsmayrisknormalizingtheconsequencesof beingshamedforRussia.Moreover,continuouswalkoutswilldisrupttheflowof conversationinamultilateralforumandprohibitprogressindrafting recommen-

20

-endations.Thus,namingandshamingshouldbeselectivelycarriedoutwhen andifRussiamakesanextremeaction,whetheritbethroughanewmilitary interventioninUkraineoranovelinflammatoryremarkinapoliticalforum.For example,ifRussiaweretocommitanunprecedentedhumanrightsviolation,or spreadnewmisinformationthatrequirescondemnation,awalkoutmaybean appropriatestrategy.However,ifRussiamakesasimilarstatementtheweek followingawalkoutmotivatedbythesamebehaviour,awalkoutmaybe redundant.

Conclusion

Namingandshamingcanbeaneffectivetooloftriggeringdomestic pressureanddamagingastate’sreputation.However,walkoutscanalsobe ineffectivebyreplacingoneviolationwithanother,leadingtorepression substitution.Walkoutscanalsoincurcounterproductiveeffectsbyincentivizing thetargetstatetoactoutofbacklashbylimitingroomforcompromiseinfuture negotiationsandincreasinghumanrightsviolationsoutofhostility.Toconduct walkoutseffectively,thisstrategymustbeimplementedinfrequentlyand collectively.

Namingandshamingisaneffectivemechanismofenforcingcompliance becauseitisalow-costandaccessiblestrategyofcollectiveactionthatsparks mediaattentionandefficientlyrespondstoRussia’sinflammatoryinterventions withoutderailingtheconversationinapoliticalforum.Despitethesebenefits, thereisconcernabouthowwalkingoutagainstRussiamaybeineffectivebecause thecountryisimmunetodomesticpressure.Moreover,walkoutsmayproduce counterproductiveconsequencesbygeneratingbacklashfromtheKremlin, leadingMoscowtopulloutofinternationalnegotiationsonhumanrights treaties.Furthermore,walkoutsmaycontradictthepurposeofdiplomacyand impairstates’abilitytorecordRussia’sinterventions.Inresponsetotheseharms, Russiaisunlikelytopulloutofinternationalnegotiations,astheyarefrequently criticized,yetcontinuetoparticipateinmultilateralforumsonhumanrights issues,likeatruefalsepositivestate.Furthermore,thepurposeofdiplomacyis moreseverelyharmedbyallowingacountrywhoregularlyviolatesthat internationalorganizationtoparticipateinit.Finally,alackofnotetakingduring walkoutscanbesolvedbyimplementingtranscribersandbyrecordingmeetings. Sincethebenefitsofnamingandshamingoutweightheharms,walkoutsarean effectivestrategyforenforcingRussia’scompliance.

Toensurethatwalkoutscontinuetobeeffective,statesmustdothree things.First,statesshouldestablishacoordinatedstrategyofknowingwhenand howtoact,byagreeingupontriggerwordsthatdeterminewhentoexita politicalforum.Second,walkoutsshouldbespecifictotheorganizationto ensuretheydo

21

notimpedeoncertaininstitutionalstructureswhicharenotconduciveto namingandshaming.Third,walkoutsshouldbeconductedsparinglytoensure thatRussiaisnotde-sensitizedtotheireffects.Ifconductedproperly,statescan leveragethesoftpowerstrategyofnamingandshamingtopressureRussiainto compliancewithinternationalhumanrightslaw.Whilethismechanismmaynot beenoughtoforceMoscowbackintocompliance,itisanimportantfirststepin protectingUkraineandpreventingfuturehumanrightsviolations.

22

Apodaca,Clair.2018.“Chapter6:ThehumanrightscostsofNGOs’naming andshamingcampaignsCrisis,Accountability,andOpportunity.”In ContractingHumanRights:CrisisAccountabilityandOpportunity,edited byAlisonBryskandMichaelStohl,EdwardElgarPublishing,73-88.

https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nle bk&db=nlabk&AN=1723866.

Ausderan,Jacob.2014.“Hownamingandshamingaffectshumanrights perceptionsintheshamedcountry.”JournalofPeaceResearch51,no.1: 81–95.http://www.jstor.org/stable/24557536.

Bates,RodgerA.,andBryanLaBrecque.2020.“TheSociologyofShaming.”The JournalofPublicandProfessionalSociology12,no.1.

https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1162& context=jpps.

Carraro,Valentina,ThomasConzelmann,andHortenseJongen.2019.“Fearsof peers?Explainingpeerandpublicshaminginglobalgovernance.”

CooperationandConflict54,no.3:335–355.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836718816729.

DeMeritt,Jacqueline,andCourtenayConrad.2019.“RepressionSubstitution: ShiftingHumanRightsViolationsinResponsetoUNNamingand Shaming.”CivilWars21,no.1:128-152.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2019.1602805.

DiBlasi,Lora.2020.“FromShametoNewName:HowNamingandShaming CreatesPro-Government Militias.”InternationalStudiesQuarterly64,no. 4:906–918.

https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa055.

GuardianNews.“DozensofdiplomatswalkoutduringRussianforeign minister'sUNspeech.”Youtube,March1,2022.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozgGPWnVLkY.

Fortuin,Egbert.2020.“‘UkrainecommitsgenocideonRussians’:theterm ‘genocide’inRussianpropaganda.”RussianLinguistics46, 313–347.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-022-09258-5.

Funakoshi,Minami,HughLawson,andKannakiDeka.2022.“Tracking SanctionsagainstRussia.”Reuters,ThomsonReuters,

https://www.reuters.com/graphics/UKRAINE-CRISIS/SANCTIONS/b y

WorksCited 23

vrjenzmve/.

Gallagher,Adrian.2021.“ToNameandShameorNot,andIfSo,How?A PragmaticAnalysisofNamingandShamingtheChineseGovernmentover MassAtrocityCrimesagainsttheUyghursandOtherMuslimMinoritiesin Xinjiang.”JournalofGlobalSecurityStudies6,no.4.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogab013.

Hafner-Burton,Emilie.2008.“SticksandStones:NamingandShamingthe HumanRightsEnforcementProblem.”InternationalOrganization62,no. 4:689–716.http://www.jstor.org/stable/40071894.

OHCHR.2022.“Ukraine:CivilianCasualtyUpdate5December2022.”United Nations.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/news/2022/12/ukraine-civilian-casualty-updat e-5-december-2022#:~:text=From%201%20to%2030%20November,is%20y et%20unknown)%3B%20and.

Simmons,Beth.2009.MobilizingforHumanRights:InternationalLawin DomesticPolitics.Spain:CambridgeUniversityPress.

Snyder,Jack.2020.“Backlashagainstnamingandshaming:Thepoliticsofstatus andemotion.”TheBritishJournalofPoliticsandInternationalRelations 22,no.4:644–653.https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120948361.

UNHCR.2022.“Ukraine-FastestGrowingRefugeeCrisisinEuropesince WWII.”UploadedJune6,2022.

https://www.unhcr.org/hk/en/73141-ukraine-fastest-growing-refugee-crisi s-in-europe-since-wwii.html.

Wong,Seanon.2020.“MappingtheRepertoireofEmotionsandTheir CommunicativeFunctionsinFace-to-faceDiplomacy.”International StudiesReview22,no.1:77–97.https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viy079.

24

IndigenousElectoralParticipationand Non-ParticipationinCanada:DefiningTheir Ideological

DifferencesandtheCaseforCooperation

MiaGill

EditedbyCatrionaArnott

25

(Matt Comte / Getty)

Thispapermustbeginwithanacknowledgementofmypositionality.I amanIndigenousstudent:aDehchoDenewomanandastatusmember ofLiidliiKueFirstNation.Iwasbornandraisedin Kootsisáw/Wincheesh-pah/Moh-kíns-tsis(Calgary),onTreaty7land, separatefrommynation.DespitenotbeingraisedinLiidliiKue,Iremain connectedtomyfamilyandcommunity.MyDenelinecomesfromthe HorassiandHoresayfamiliesoftheDehchoregion-whoarerelated, howeverhavedifferentspellingsofaphoneticallyidenticalsurname-my grandmother,aHoresay,marriedasettlermanandhadmyfatherbefore 1985.Duetothis,IamaBillC-3statusperson.Mymotherisa refugee-immigrantborninPolandwhofledduringthePolishPeople’s Republiccommunistrule.IhavelivedandworkedinLiidliiKueduring thesummersof2020and2021asanexecutiveassistanttotheGrand ChiefofDehchoFirstNations.

Introduction

WhydosomeIndigenouspeoplesbelieveinCanadianelectoral participationwhileothersdonot?Aretheseideologiescounterintuitive,orcan theyworkincollaboration?Indigenouspeopleswhoseekthegoalof self-determinationareengagedinaperpetualdebateonwhethertovoteinthe electionsofcolonialpoliticalsystemsorabstain(Narine2021).SomeIndigenous peoplesarguethatelectoralparticipationunderminestheirfightforsovereignty (Katsi’tsakwas[Gabriel]2021;Waabshkigaabo[Landon]2021).Nevertheless,in the2015election,61.5percentofregisteredvotersonreservescastaballot (SlaughterandMacyshon2019).Thispaperevaluatestheinteractionbetween twomainfactors:Indigenousself-determinationand,therefore,rejectionof colonialpoliticalsystemsandparticipationintheCanadianelectoralsystem.This ‘Canadianelectoralsystem’excludesallchiefandcouncilelectionswhile includingthosethatmakeupthesettler-colonialstateapparatus:municipal, provincial/territorial,andfederalelections.Thispaperwillarguethefollowing threeconclusionsusingtheoreticalandempiricalanalysis.First,bothIndigenous26

Statement

non-participatoryandparticipatoryideologiesaredeterminedbypotentialvoters simultaneouslyconsideringthefactorsofelectoralparticipation:rationalchoice theoryanddutytovote.Second,whilethenon-participatoryideologyisdefined byconsideringelectoralparticipationfactorsinrelationtoalienationand Indigenousnationalism,theparticipatoryideologyisdefinedbythesefactors' interactionswithstrategyandrepresentation.Lastly,Indigenouselectoral participationdoesnotunderminethegoalofself-determination.Thisisbecause thegoalofdualcitizenshipasameansforself-determinationmakeselectoral participationbothnecessaryandactivelycreatesuniquevalueforautonomy;the utilizationofthefourrolesoftheactivismmodelrequirestheIndigenousactive voterandelectedrepresentativewhilearolethatincludesthoseengagedinrefusal isstillvital.

FactorsofElectoralParticipation

Touncoverthepatternsandcoexistenceofparticipatoryand non-participatoryIndigenousideologies,onemustunderstandwhypeoplevote. Rationalchoicetheoryisoneapproachtounderstandingvoterturnout.Inbrief, rationalchoicetheoryarguesthatvotersdecidewhethertovotedependingonan independentcalculationthatweighsthecostsandbenefitsoftheirchoice.A decisiondependsonwhichoutcomeresultsinthemostsignificantpersonal benefits(LevinandMilgrom2004).Inthequestionofwhethertovote,a calculationmaylooklikethis:anactorwillaccruexcostfromvotingandis expectingtoreceiveybenefits.Ifyminusxispositive,theywillvote;ifnegative, theywillnot.Animportantcaveattothistheoryisthatbenefitsmustbe expected,notmerelypotential;thereforeifanelectorvotesforthemost beneficialcandidatewhoissuretolose,theexpectedbenefitsarenil,andwill chooseacandidatewithahigherexpectedbenefit(Blais2000,1).However,this raisesthe“paradoxofnotvoting:”ifelectionsaredecidedbysuchalargenumber ofpeople,onevoter’sdecisionseemsunlikelytomakeadifference,andtherefore, theyhavenoreasontovote(Feddersen2004).Anexperimentalstudyonstudent votersinthe1993Canadianfederalelectionshowedthatevokingtherational choicetheory’sparadoxinpotentialvotersresultedinreducedturnout“mainly becausethepresentationdiminishedtherespondents’senseofduty,aneffectthat was

27

indirect”(BlaisandYoung1999).Opponentsofrationalchoicetheorymay arguethatitprovidesalimitedscopeonhumanbehaviour,specificallyby assumingthecontinuousrationalityofindividualsandignoringtheinfluenceof affectivedimensions.Thisobjection,alongwiththeimplicationsarisingfromthe paradoxofnotvotingleadustoconsiderasecondfactorinthevotingequation. Thesecondfactoraffectingwhetheranindividualelectordecidestovote is‘duty’,whichcanbeunderstoodastheemotionofpersonalresponsibilityto vote.Thisfactorisnotconcernedaboutpotentialgainsbutinsteadreflectsa philosophicalstressorthatholdsvotingasavirtuousactionforacitizenofa democracy.ThroughdatacollectedinCanadaduring2008and2009andSpain from2010to2012,researchersfoundthateventhoughdutyisreinforcedafter voting,itstillstronglyaffectsone’smotivationtovotebeforeengaginginsuch behaviour(GalaisandBlais2016).Ithasalsobeenshownthatrationalchoice anddutycansimultaneouslyaffectindividuals,andthosewithaweakersenseof dutyrelymoreontherationalchoicefactorwhendecidingwhethertovote(Blais 2000,92-114).Thefactorsofrationalchoiceanddutywillbeusedtoanalyzethe differencesbetweenparticipatoryandnon-participatoryIndigenousvoters’ ideologicalunderpinnings.

DefiningtheIndigenousNon-ParticipatoryIdeology

Non-participationofIndigenouspeoplesincolonialelectionsis motivatedbytwomainfactors:alienationandnationalism.Tounderstand Indigenouspeoples’alienationfromtheCanadianelectoralsystem,onemust examineCanada’scolonialhistoryofpoliticaldisenfranchisementandattempted assimilation.Post-confederationCanadadeniedstatusFirstNationspeoplesthe righttovote;astringofassimilationistenfranchisementlegislation(includingthe GradualCitizenshipActof1857andtheIndianActof1876)hadmeanwhile beenprovidingtherightinexchangefortheadoptionof‘civilized’waysoflife (Leslie2016).Inuitwereallowedtovotein1950,althoughitwasnotuntil1962 thattheywereprovidedsufficientballotboxes.FirstNationpeoplesweregiven thefederalrighttovotein1960and,bytheendofthe1960s,Indigenouspeoples couldvoteineveryprovincialandterritorialelection(Leslie2016).Oneresultof thisrecenthistoryofthedenialofvotingrightstoIndigenouspeoplesisthe

28

continuinglackofelectedIndigenousrepresentationingovernment,which Daltonarguescauses“alackoflegitimacy[oftheelectoralsystem]fromthe perspectiveofmanyFirstNations”(2007,252).

Indigenousnationalismisthefoundationfortheoriesof self-determination.AudraSimpson’sMohawkInterruptusoffersasuccinct theorytounderstandhowIndigenousnationalismpresupposesthepraxisof non-participationincolonialelections.Simpsoncoins“politicsofrefusal”asa responseto“politicsofrecognition,”thelatterofwhichisthetendencyof CanadaasasettlercolonialstatetoattempttoundermineIndigenous sovereigntythroughtheofficialrecognitionofIndigenouscultureasdistinctyet nestedinCanadiancitizenship(2014,11).Politicsofrefusalinstead "acknowledge[s]anduph[olds]"the"politicalsovereignty"ofthecolonized peopleswhilequestioningthe"legitimacy"ofthecolonizingforcewhich maintainsthepowerof"recognizing";forIndigenouspeoples,thiscanmanifest intherefusaltovoteintheelectionsofcolonialstructure(Simpson,2014,11). Indigenousnationalismarguesthatengagementwithintheimposedcolonial structureofelectionsisparadoxicalandservestheharmfulpoliticsof recognition.Therefore,Indigenouspeopleshaveanideologicalbasisforengaging inapoliticsofrefusalasresistancetoassimilation.

Theinteractionbetweenalienationbornfromahistoryof disenfranchisementandsubjugationandIndigenousnationalismasthe resistancetothisalienationisself-perpetuating:“theendresultisanelectoral systemthatlackslegitimacyforFirstNations,ultimatelyleadingtofurther alienation”(Dalton2007,274).Assimilationistmotivationsforexpandingthe righttovotedirectlyunderminetheself-determinationofIndigenouspeoples expressedthroughIndigenousnationalism.Canada’shistoryofenfranchisement asacivilizingforcerevealsthattherighttovotewasnotgiveninorderto strengthenthenation-to-nationrelationshipsbetweenIndigenouspeoplesand Canadabutwasinstead“becauseoftheideathatCanadiancitizenshipwould furtherintegrateFirstNationsintoCanadiansociety,assistwithsocio-economic issuesandhelpCanadaincontinuingtoignoreFirstNationsautonomy, nationhoodandtheirowncitizenship”(Cowie2021).

InasurveyofIndigenousyouth,manyofthosewhohavepreviously abstainedfromvotingreporteddoingso“asamatterofprinciple,”andinstead,

29

alternativeengagementinpoliticswasreferenced,including“traditional governance,radicalpoliticsanddirectactions”(GeraldR.,Pitawanakwat,and Price,2007,11).Understandingtheinteractionbetweenalienationand nationalism,itisclearthatforsomeIndigenouspeoplesengagingin non-participationdutyhasbeentransformedandisnolongerapplicable.Aduty forthecolonialdemocraticsystemhasbeennullified,andinstead,anewdutyhas emerged:self-determinationandsupportofnon-electoralpoliticalparticipation. However,sincethosewithaweakerdutytovoterelymoreheavilyonrational choicetheory(Blais2000,92-114),whydoIndigenouspeopleswithout democraticdutynotinsteadvotebasedonrationalchoice?Inthesurveyof Indigenousyouth,itwasfoundthat“[a]pragmaticcalculationisbeingmade thattheIndigenousvoteisunlikelytohaveanimpact‘unlessyouhavean overwhelminglyhighnumberofIndiansinoneprovince.’”(GeraldR., Pitawanakwat,andPrice,2007,11).Thisshowsthatforsomefollowersofthe non-participatoryroute,itseemsasthoughtheparadoxofrationalchoicevoting isalsomotivatingtheirnon-participation.

DefiningtheIndigenousParticipatoryIdeology

ThemotivationsbehindtheIndigenousparticipatoryideologycanbe definedwithtwomajorthemes:strategyandrepresentation.Thechoicetovoteis sometimesexplainedbyIndigenousvotersasstrategic,withthegoalof preventingworseoutcomesthatmayresultfromnotvoting.Oneofthe justificationsprovidedmultipletimesbysurveyedIndigenousyouthwhohave previouslyvotedwas“apreventivestrategy–asameanstopreventpeoplewith dramaticallydifferentvaluesandbeliefsfromrepresentingthem”(GeraldR., Pitawanakwat,andPrice,2007,7).Intheirtestimony,individualsreferencedthe possibleadverseeffectsofelectedrepresentativesontreaties,theircommunities, andtheirrights(GeraldR.,Pitawanakwat,andPrice,2007,6).Thismotivation canbeseenasdirectlyreflectingrationalchoicetheory.WhileIndigenous individualsmayunderstandthatvotingwithincolonialstructuresseems paradoxical,theymayweightheexpectedcostsofnotvotingtobetoolargeto abstain.

Thesecondmotivationalthemeisrepresentation:specifically,adesirefor electedrepresentativestorepresentIndigenouspeoplesand,therefore,electoral

30

supportforcandidateswhoidentifyasIndigenous.InthesurveyofIndigenous youth,thosewhohavepreviouslyvoted“arguedthatsupporting,encouraging andvotinginAboriginalcandidateswasparamount,”specificallytoensurethat thosewithsimilarbeliefsandvaluesastheminfluencecolonialgovernance structures(GeraldR.,Pitawanakwat,andPrice,2007,7).Thisthemeis supportedbyevidenceof‘affinityvoting’:thetrendofminoritiesbeingmore likelytovotewhenacandidatethatrepresentstheirminorityidentitiesis running.InastudyofdatafromCanada’s2006,2008,2011,and2015federal elections,researchersdiscoveredthataffinityvotingisinfluentialinIndigenous votechoice(Dabin,Daoust,andPapillon2019).Voteturnoutwashigherin IndigenouscommunitieswhenanIndigenouspersonwasontheballot;with threeoffourIndigenouscandidatesontheballot,turnoutincreasedbymore than15percent(Dabin,Daoust,andPapillon2019,50).Further,political partiesalsobenefitedfromhighervoterturnoutfortheirpartyinIndigenous communitieswhentheyhadIndigenouscandidates,withthepartysupport scalingalongsidethenumberofIndigenouscandidates(Dabin,Daoust,and Papillon2019).

Thethemeofrepresentationasamotivationalfactorfortheparticipatory Indigenousideologyreflectsboththefactorsofdutyandrationalchoicetheory. Indigenouspeopleslikelyfeelanemotionaldutytosupporttheirkininpolitics. ItalsofollowslogicallythatanIndigenousrepresentativewiththesamevaluesas Indigenousvotersismorelikelytoworktowardspositivepolicydecisionsfor Indigenouspeoplesspecifically.Thustheexpectedbenefitofelectingan Indigenousrepresentativeisboosted,andpotentialvotersaremorelikelyto decideusingtherationalchoicetheorythatvotingismorebeneficialthan abstaining.

ElectoralParticipation:CounterintuitiveorCollaborative?

Isitpossiblefornon-participatoryandparticipatoryideologiestoexist withoutunderminingoneanother?Palmaterarguesthisisimpossible,asthe virtuesofelectoralparticipationaremythologicalforIndigenouspeoples,making theboldclaimthat“whenIndigenouspeoplesvote,theyvotefortheirnext oppressor”(2019).SheclaimsthattheCanadianpoliticalsystemintentionally subjugatesandharmsIndigenouspeoplesthroughtheirexclusion.

Palmater

31

pointstotheHarperandTrudeaugovernmentsasexamplesofhowregardlessof statedintentionorpartyinpower,theCanadianpoliticalsystemactivelyworks againstIndigenousself-determinationandautonomy:“Whatisthecore differencebetweenpastracistandaggressivegovernments,whichdidn’tgiveour landsbackorrespectourtreaties,andthecharmingandpositivePrimeMinister Trudeau,whodoesexactlythesame?”(2019).Further,whilethepotentialfor increasesinbeneficialfundingisacknowledged,thesearetemporaryanddonot makeupforthelackofactiononmissingandmurderedIndigenouswomenand girlsandtheincreasingIndigenousoverrepresentationinthefostercaresystem, inthecarceralsystemandpovertyorhomeless(Palmater2019).

ThecruxofPalmater’sargumentisthatforIndigenouspeopleswho participateintheCanadianelectoralsystem;“theirvoicemakesnoactual difference,”asthestructuresofcolonialismandanti-Indigenousracismare ingrainedintoCanada’spartysystem(2019).Palmaterisessentiallyassertingthat thereisnoexpectedgoodfromIndigenousvoterparticipation,regardlessof partyplatformsorleaders.Therefore,therationalchoiceforIndigenouspeoples istorefrainfromvotingandengageinothermeansofpoliticalactiontobetter theircircumstances,whetherthrough“protests,publicpressure,litigationor outsideinterventionattheUnitedNationslevel”(Palmater2019).Underthis argument,thereisnomovementforstrategicvoting–the‘worseoption’is essentiallythesameasthestrategic‘better.’

However,PalmaterignorestherelevanceofdutyinIndigenous participatoryideology.Whileshedoesstatethattheconceptualizationofcivic participationasadutyisamythforIndigenouspeoplesinthedemocraticsense oftheterm,as“botharightandaresponsibilityofcitizens,”sheignoresthe representationaldutyIndigenouspeopleshavetoeachotherwhenvoting (Palmater2019).Asnotedearlier,Indigenouspeoplesaremuchmorelikelyto voteiftherearecandidateswhoidentifyasIndigenous.Thisdutyliesoutsideof theEurocentricdemocraticdefinitionofdutyandinsteadistheresultof Indigenousrelationalityandresponsibilitytokin.RelationalityasanIndigenous conceptisexpressedthroughwaysoflifeandone’sresponsibilitytotheir relations(Tynan2021).Further,relationalityasapracticeisapartofIndigenous self-determinationbyrejectingcolonialimpositionsofidentityandcommunity (Tynan2021).InordertosupportIndigenouskinshipties,anewdutyiscreated

32

andexistsdespitethefailureoftherationalchoicecalculation,andtherefore Indigenouspeopleshaveareasongroundedinself-determinationundersome circumstancestoengageinelectoralparticipationwhilenotbeing counterintuitive.Further,asPalmaterfailstoconsiderIndigenousrepresentation inCanadianpoliticsaltogether,sheignoresthattheelectionofIndigenous peopleintogovernmentcanservetolessentheharmofthecolonialsystemfrom theinside.

SomeonearguingindefenceofPalmater’sthesismayrespondthat Indigenousrepresentationinpoliticsdoesnotmagicallysolvethecolonial structureofthatsystem–despitethereinforcementofIndigenousrelationality indoingso.In“Being-in-the-Room-Privilege,”Táíwòmakeshis‘elitecapture’ argument,whichraisescriticalissueswiththeacceptanceofstandpoint epistemology,particularlyforpeopleinpositionsofprivilege.Standpoint epistemologyisusedinradicalpoliticalspherestorefertotheclaimthatthose withlivedexperiencesofmarginalizationhaveaccesstouniqueknowledgethat thosewithoutthoseexperiencesdonothave–andthus,minorityrepresentation inpositionsofpowercanservetounderminethemarginalizingeffectthosein thatpositionhavehistoricallyreinforced(Táíwò2020).AnIndigenous proponentofstandpointepistemologywouldarguethatIndigenous representativesintheCanadiangovernmentwouldchampiontheotherwise unheardperspectivesofIndigenouspeoplesandthereforebringgoodto Indigenouspeoplesthroughpolicy.However,Táíwòarguesthatthosewho managetogainaccessto‘theroom’–inthiscase,bybeingelectedasa representative–aremostoftenthe“elites”oftheirmarginalizedgroupand thereforedonothavelivedexperiencesthatwouldbemostusefulfortheaverage orthemostmarginalizedofthatminoritygroup(2020).Usingthisargument, howcanIndigenousvotersbesuretheirIndigenousrepresentativehasthesame valuestheydo?Theansweristhattheycannot;instead,theyoughttobewary aboutusingrepresentativesoftheirvaluesandbeliefstogainfurther self-determinationthroughactionwithintheCanadiangovernment. Nevertheless,byreconceptualizingthegoalforIndigenous self-determinationasthejourneytowardsdualcitizenship,itbecomesclearhow engaginginelectoralparticipationcanfurtherthepoliticalgoalsofIndigenous peoplesandcommunities.CowiearguesthatIndigenouspeoplesoughttouse

33

Canada’spoliticalsysteminordertopushforasocietythatembracesBorrows’ conceptualizationof“dualcitizenship:”whereinnation-to-nationrelationships arerespectedinapoliticallandscapeofseparatenessratherthandifferenceand equalityratherthanpoliticalentrenchment(2013,84-96).Byengagingin electoralparticipation,Indigenouspeoplescanpushfortheoriginal nation-to-nationrelationshipsbetweenthemselvesandCanadiansandincrease theIndigenoussphereofinfluenceacrosstheCanadianlandscape(Cowie2013, 94).ThislatterbenefitcanfurtherexpandIndigenousidentityandcitizenship: pastbloodrelationsandtowardsacivicidentitythatexistsalongsideCanadian identities,thusreturningself-determinationtotheveryfoundationof communityandIndigenousidentityitself(Cowie2013,92-93).Itbecomesclear howbydefiningIndigenouspeoples’goalforself-determinationasthecreation ofa‘dual-citizenship,’theveryactofelectoralparticipationbecomesnecessary andproductiveforIndigenoussovereigntyandwell-being.

Lastly,Moyer’sconceptualizationofthe“fourrolesofsocialactivism” showshowitisshort-sightedtocategorizeIndigenouselectoralparticipationas counterintuitive(2001,21).Moyerdescribesfourrolesthatareallneededfor effectiveactivism:thecitizen,rebel,changeagent,andreformer,allofwhichcan beplayedeffectivelyorineffectively(2001,21).Thetworolesthatrelyon electoralparticipationarethecitizenandthereformer.Thecitizen’spurposeis “winningoverandinvolving”thegreaterpublicthroughdemonstrationsof “goodcitizenship,”whichkeepsthesocialmovementfrombeingrelegatedtothe fringesofsociety(Moyer2001,22-23).Oneoftheexplicitrolesofthecitizento dosois“advocat[ing]anddemonstrat[ing]awidelyheldvisionofthe democraticgoodsociety;”forIndigenousactivists,thoseengaginginelectoral participationarefillingthisroleeffectively(Moyer2001,24).Thereformer’sjob istoinstitutionalizenewlyacceptedalternativespushedforwardbytheother threerolesintoformalinstitutionsofsocietythroughlegislation,policies,and practices(Moyer2001,26).Inordertohavereformersabletoperformthisfinal act,Indigenouspeoplesmustworktoelectreformersintopositionsof institutionalpower.Therefore,electoralparticipationisarequirementforthe furtheringofIndigenousself-determinationactivism.Itiscrucialtonotethat underthismodel,thereisstillaroleforthosewishingtoengageinapoliticsof refusalpurely:therebel.Thekeyspecificityoftherebelisthateventhoughthey aremeanttogain

34

attentionforcausesthroughdramaticacts,theydosowiththegoalthatthose causescaneventuallybeformalizedbythereformer(Moyer2001,24).Murphy (2008)arguesthatelectoralparticipationhasbeenburdenedbyunrealistic expectationsofitsabilitytoresultinIndigenousself-determinationalone.By understandingthefourrolesofsocialactivismandapplyingthemtothegoalof dualcitizenship,itbecomesclearhowIndigenouselectoralparticipationisnota counterintuitiveactbutratheranecessarytoolforcooperationinthefightfor Indigenousself-determinationthatcannotworkalone.

Conclusion

Theuseofrationalchoicetheoryanddutyasexplanatoryfactors illustratestheideologicaldifferencesbetweenIndigenouselectoralparticipation andnon-participation.Theformerisdefinedbytheinfluenceofstrategyand representation,whilethelatterisdefinedbyalienationandIndigenous nationalism.Throughtheredefinitionofthegoalofself-determinationas towardsdualcitizenship,itbecomesclearthatIndigenouselectoralparticipation isnotcounterintuitivetogreatergoalsofsovereignty.Rather,itisamodeof activismthatfitsintoamoresignificantmodelthatrequiresandisfurther propelledbyitsachievements.Indigenousactivistsseekingself-determination mustcooperatewhethertheytaketheroleofrefusalorelectoralparticipation,as bothfunctionsarecrucialinthefightforsovereignty.

35

Aldrich,JohnH.1993.“RationalChoiceandTurnout.”AmericanJournalof PoliticalScience37,no.1:246–278.https://doi.org/10.2307/2111531.

Alfred,Taiaiake,BrockPitawanakwat,andJackiePrice.2007.“Themeaningof politicalparticipationforindigenousyouth.”InChartingtheCoursefor YouthCivicandPoliticalParticipation.CanadianElectronicLibrary. Retrievedfrom

https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1219752/the-meaning-of-political-pa rticipation-for-indigenous-youth/1772829/.CID:20.500.12592/x9ktfv. Blais,André.2000.ToVoteorNottoVote?:TheMeritsandLimitsofRational ChoiceTheory.UniversityofPittsburghPressDigitalEditions.Pittsburgh, Pa.:UniversityofPittsburghPress.

Blais,André,andRobertYoung.1999.“Whydopeoplevote?Anexperimentin rationality.”PublicChoice99:39–55.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018341418956.

Cowie,Chadwick.2021.“AvoteforCanadaorIndigenousNationhood?The complexitiesofFirstNations,Métis,andInuitparticipationinCanadian politics.”TheConversation,November1,2021.

https://theconversation.com/a-vote-for-canada-or-indigenous-nationhoodthe-complexitie

s-of-first-nations-metis-and-inuit-participation-in-canadian-politics-169312

Cowie,Chadwick.2013.“Validityandpotential:Dual-citizenshipandthe IndigenousvoteinCanada’sfederalelectoralprocess.”MAdiss.,University ofManitoba.

https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1993/22226/C owie_Chadwick.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Dabin,Simon,JeanFrançoisDaoust,andMartinPapillon.2019.“Indigenous PeoplesandAffinityVotinginCanada.”CanadianJournalofPolitical Science52(1):39–53.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423918000574.

Dalton,Jennifer.2007.“AlienationandNationalism:IsItPossibletoIncrease FirstNationsVoterTurnoutinOntario?”

CanadianJournalofNative Studies27(2):247–291.

Feddersen,TimothyJ.2004."Rationalchoicetheoryandtheparadoxofnot voting."JournalofEconomicPerspectives18,no.1:99–112.

WorksCited 36

Galais,Carol,andAndréBlais.2016.“Beyondrationalization:Votingoutof dutyorexpressingdutyaftervoting?”InternationalPoliticalScience Review37(2):213–229.https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512114550372. Katsi’tsakwas[Gabriel,Ellen].2021.“Respectmyrightnottovote:for Indigenouspeoples,votinginacolonialsystemcomesatacosttoour sovereignty.”RicochetMedia,September14,2021.

https://ricochet.media/en/3776/respect-my-right-to-not-vote

Leslie,JohnF.2016."IndigenousSuffrage."TheCanadianEncyclopedia. HistoricaCanada,March31,2016.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indigenous-suffrage Levin,Jonathan,andPaulMilgrom.2004.Introductiontochoicetheory.

https://web.stanford.edu/~jdlevin/Econ%20202/Choice%20Theory.pdf

Moyer,Bill.2001.DoingDemocracy:TheMapModelforOrganizingSocial Movements.GabriolaIsland,BC:NewSociety. Murphy,MichaelA.2008.“RepresentingIndigenousSelf-Determination.”The UniversityofTorontoLawJournal58(2):185–216.

Narine,Shari.2021.“ManyIndigenousvotersstrugglewithwhethertovote.” OrilliaMatters,September6,2021.

https://www.orilliamatters.com/canadavotes2021/many-indigenous-voter s-struggle-withwhether-to-vote-4303853

Palmater,Pam.2019.“TheironyoftheFirstNations’vote.”Maclean’s,October 7,2019.

https://www.macleans.ca/opinion/the-irony-of-the-first-nations-vote/ Simpson,Audra.2014.MohawkInterruptus:PoliticalLifeAcrosstheBordersof SettlerStates.Durham:DukeUniversityPress.

Slaughter,Graham,andJillMacyshon.2019.“Indigenousvotersbrokerecords inthe2015election.Willtheydoitagain?”CTVNews,September13, 2019.

https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/federal-election-2019/indigenous-votersbroke-records-in-the-2015-election-will-they-do-it-again-1.4593104

Táíwò,Olúfẹ́miO.2020.“Being-in-the-Room-Privilege:EliteCaptureand EpistemicDeference.”ThePhilosopher.

https://www.thephilosopher1923.org/post/being-in-the-room-privilege-eli te-capture-and-epistemic-deference

37

Tynan,Lauren.2021.“Whatisrelationality?Indigenousknowledges,practices, andresponsibilitieswithkin.”CulturalGeographies28(4):597–610.

https://doi.org/10.1177/14744740211029287

Waabshkigaabo[Landon,Will].2021.“AsanAnishinaabecitizen,Ican’tvotein goodconscienceinfederalelections.”CBCFirstPerson,September17, 2021.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/first-person-anishinaabe-vote-federal-ele ction-1.6178236

38

Priests,Politicians,andPandemics:Driversof COVID-19ConspiracyTheoryBeliefinRomania

Edited

SaraParker

byLilyMason

Edited

SaraParker

byLilyMason

39

(Daniel Mihailescu / AFP)

RomaniahasoneofthelowestratesofCOVID-19vaccinationinEurope; lessthanhalfthepopulationhasreceivedonedoseandlessthan10%have receivedtheirbooster(ECDC,2023).Theselowvaccinationratesarenotdueto alackofdoses,however,despiteanextensivevaccinationprogram,Romaniawas forcedtosellexpiringdosestocountrieslikeDenmark,Ireland,andSouth Korea.Rather,Romanianschosetonotgetvaccinated.Thispaperwillthus explorethedriversofCOVID-19conspiracytheory(CT)beliefinRomania, payingparticularattentiontothecontentofCTs,theliteratureaboutCTbelief, theliteratureaboutvaccinehesitancy,corruptioninRomania,andsourcesof institutionaldistrust.ItwillthenengageinaqualitativeanalysisofRomanian CTsandaquantitativeanalysisonsourcesofinstitutionaldistrustandvaccine hesitancy,demonstratingthatthecharacterofprominentCOVID-19CTsin Romaniahasstrongrootsininstitutionaldistrust,whichis,itself,correlatedwith lowvaccinerates.Ultimately,itarguesthatinstitutionaldistrust,asmotivatedby personaleconomichardship,increasestheprobabilitythatanindividualwill believeCOVID-19CTsinRomaniaand,therefore,thattheywillnotget vaccinated.

COVID-19ConspiracyTheoriesInRomania

ACTisdefined,forthepurposesofthispaper,asatheorythat“explains aneventorsetofcircumstancesastheresultofasecretplotbyusuallypowerful conspirators,”(Merriam-Webster).EverydominantCTregardingtheCOVID-19 virusinRomaniaimplicatesthegovernmentinaconspiracytocontrolthe population.AsdescribedinLupandMitrea’s(2021)studyonuniversity studentswithconspiracybeliefs,themostpervasivetheoryisthatthevirusisnot asdangerousasthegovernmentisleadingthepublictobelieve(7).Althoughnot assevereasothertheories–forexample,theassertionthatthepandemicisascam tousherintheNewWorldOrder–thiswidely-heldbeliefunderminesthe authorityofgovernmentandsowsdistrustinRomanian,European,and internationalinstitutions.Othertheoriesincludetheassertionthatthepandemic isaconspiracybypoliticalelitestorestrictandcontrolcitizens;thattheviruswas

Introduction

40

createdbyscientistsinalab,likelyinWuhan,China;andthatthepandemicisa conspiracybyinterestgroups,likethepharmaceuticalindustry,forfinancialgain (LupandMitrea2021,7).ThesetheoriesweresupportedbyOrthodoxpriests, manyofwhomassuredtheircongregationsthatreceivingtheCOVID-19 vaccinationwasunnecessary(Higgins2021).TheRomanianOrthodoxChurch furtherrejectedacollaborationwiththenationalgovernmentonacoordinated vaccinationcampaign,citingtheirrefusalas“fundamentallyethical”becauseof theChurch’spromotionof“personalfreedom,”(Muresan2021).Additionally, somedoctorshavecontributedtotheCTs,includingFlaviaGrosan,a pulmonologistwhohasfalselyassertedthatCOVID-19shouldbetreatedlike pneumoniaandthatmedicaloxygenisdangeroustopatients.Althoughthe pandemicskepticswithinthereligiousandmedicalcommunitiesinRomania infrequentlysupportmajorCTsaboutaNewWorldOrderorthevirusbeing madeinalab,theyhaveallparroted–inonewayoranother–thetheorythatthe governmentisexaggeratingtheseverityofCOVID-19,andthatthesubsequent publichealthrestrictionsareameansofcontrollingthepopulation.

DriversOfConspiracyTheoryBelief–Literature

Evidently,itisnotsufficienttosimplycharacterizeCTs,wemustunderstand whypeopleareinclinedtobelievethem.ThedriversofCTbeliefhavebeena subjectofsocialscienceresearchsinceasearlyas1992,whenGoertzelconducted atelephonesurveyof348randomly-selectedNewJerseyresidentstounderstand thecharacteristicsunderpinningsusceptibilitytoCTbelief(Goertzel1994,733). GoertzelfoundthatCTbeliefwasnotsignificantlycorrelatedwithgender, education,oroccupation,butthattherewasahighcorrelationbetweenCT beliefandwhathecalls,“anomia”.Anomiareferstothebeliefthatthesituation oftheaveragepersonisgettingworse,thatitwouldbeunfairtobringachildinto theworldtoday,andthatmostpublicofficialsdonotcareabouttheaverage person.Inotherwords,pessimistsweremorelikelytobelieveinconspiracies (Goertzel1994,737).CastanhoSilva,Vegetti,andLittvaycontinuedthis researchin2017withasurveystudyon1415AmazonMechanicalTurkworkers intheUSthatattemptedtoidentifyapotentialrelationshipbetweenpopulist

41

attitudes(thebeliefinamalevolentgovernment)andCTbelief.Theyfoundthat populistpoliticalbeliefs,coupledwithlowlevelsofpoliticaltrust,increasedthe likelihoodthatsomeonewouldbelievethatthegovernmentisengagingina malevolentglobalconspiracy(CastanhoSilvaetal.2017,437).

DriversofConspiracyTheoryBelief–Romania

Someresearchershaveattemptedtospecificallyidentifythedriversof COVID-19CTbeliefinRomaniausingsurveymethodssimilartothose aforementioned.Achimescu,Sultanescu,andSultanescu(2020)conducteda websurveyof582Romanianadultstodetermineiftherewasaconnection betweendistrustinWesternactors(i.e.,theUS,theEuropeanUnion,and NATO)andnoncompliancewithCOVID-19publichealthguidelines(301). Theyhadtwokeyfindingsrelevanttothispaper:first,54%ofrespondentsagreed withatleastoneCOVID-19CT(suggestingthatapproximatelyhalfof RomaniansmaybelieveinCOVID-19CTsandtherebyassertingtheimportance ofunderstandingtheireffects),and,secondly,thatthelevelofconcernan individualhadaboutthespreadofthevirus–and,therefore,theiradherenceto publicguidelines–wassignificantlydependentontrustinRomanian governmentalinstitutions,illustratingtheimportanceofinstitutionaltrustin takingCOVID-19seriously(Achimescuetal.2020,305).Butoroiuetal.(2021) alsoconductedawebsurveyof945Romanians,aimedatunderstandingthe profilesofpeoplewhopubliclyendorseCOVID-19CTs.Theyfoundthat perceptionofonlinefakenews,perceivedusefulnessofsocialmedia,education level,andreligiosityweresignificantpredictorsofCTbelief(Butoroiuetal. 2021,7).Theauthorsspecificallyhighlighthighlevelsofchurchattendanceas beingassociatedwithanincreasedlikelihoodthatanindividualwillbelievein CTsaboutCOVID-19vaccines,pointingtotheimpactthatOrthodoxpriests havelikelyhadonspreadingCOVID-19CTsanddrivingthelowvaccination rate(Butoroiuetal.2021,10).Althoughbothstudiesarefairlysmall,andneither includespeoplefromallregionsofRomania,theyrepresentanimportantfirst stepinidentifyingthedriversofCOVID-19CTbeliefinthecountry.

42

VaccineHesitancy–Europe

Researchhasalsobeendonespecificallyondriversofvaccinehesitancy,the findingsofwhichbearsimilaritiestothedriversofCTbelief.Mostprominently, Jenningsetal.’s2021studyonCOVID-19vaccinehesitancyintheUKfound thatCTbeliefhadasignificanteffectonvaccinehesitancy,whilealsoidentifying aconsistentrelationshipbetweeninstitutionaldistrustandunwillingnesstoget theCOVID-19vaccine(8).Theyultimatelyconcludethat“holdingconspiracy beliefsisasignificantpredictorofvaccinehesitancy,”whileinstitutionaldistrust actsasakeypredictorofone’slikelihoodofholdingaCTbelief(Jenningsetal. 2021,10).Recio-Romanetal.(2021)findsimilarresultsintheirstudyon vaccinehesitancyandpoliticalpopulisminEurope.Usingthe2020 Eurobarometersurveyandaninvariantcross-nationalstudy,theauthorsfind that“distrustininstitutionswasthemainunderlyingdriverthatwasassociated withbothvaccinehesitancyandpoliticalpopulism,”(Recio-Romanetal.2021, 10).Mostnotablyforthispaper,Recio-Romanetal.concludethattheclusterof countriesofwhichRomaniawasapart(includingFrance,theUK,Spain, Greece,Bulgaria,andCroatia)hadthehighestratesofpopulism,institutional distrust,andbeliefthatvaccinesareuselesscomparedtotheotherEuropean clusters(2021,9).

VaccineHesitancy–Romania

Ahandfulofstudieshaveaimedtounderstandvaccinehesitancyspecificallyin Romaniaandhavefoundasimilarlinkwithinstitutionaldistrust.Forinstance, Radu(2021)usedthecityandsurroundingsuburbsofClujasacasestudy.He surveyedapproximately700citizensabouttheirdemographicindicators,trustin publicinstitutions,andcompliancewithpublichealthmeasures,andfoundthat citizenswithhightrustinpublicinstitutionsweremorelikelytofollow guidelines(Radu2021,143).Mikoetal.(2019)alsouseClujasacasestudyto assesstheprevalenceofvaccinehesitancy–notably,priortotheCOVID-19 pandemic.Theauthorsfoundthat30%ofrespondentswerehesitanttoreceive

43

vaccinesorallowtheirchildrentoreceiveit(Mikoetal.2019,6).Uponasking respondentswhytheywereskepticalofvaccines(specificallythoseagainst varicella,measles,andHPV),mostrespondedwithassertionsthatvariousmedia sourcesandsomepoliticalleadershadsoweddoubtabouttheirefficacy,while otherspointedtoageneralmistrustofthepharmaceuticalindustry(Mikoetal. 2019,8).

Bothpapersexperienceddifficultyinclearlyidentifyingthedriversof institutionaldistrustthatspecificallyledtovaccinehesitancy:Radu(2021) foundthatlevelofeducationhadaminimaleffectoninstitutionaltrust,while occupationhadastatisticallysignificantbutsmalleffectonfollowingpublic healthmeasures(139,142).Furthermore,Mikoetal.(2019)couldonlyspeculate aboutwhypeoplemistrustpoliticalleadersandthepharmaceuticalindustry, suggestingthatknowledge(oreducation)andaversenesstoriskcouldplayapart (7-9).ThefollowingsectionswillthereforeexploreRomanianinstitutional distrustinmoredetail.

CorruptioninRomania

TrustintheRomaniangovernmentishardtofind.Romaniaconsistently sitsatthetopofcorruptionlistsintheEuropeanUnion(in2020,Transparency Internationalrankeditthird)andreportsremarkablyhighratesofperceptionof corruption.Forinstance,22%ofRomaniansreportedhavingtobribehealth officialsforbasicservices(slippingthenurseafewbillstopayattentiontoa patientorchangeanIV,forexample),while51%ofRomaniansbelievethat MembersofParliamentareinvolvedincorruption(Transparency2021).These attitudesarebasedinhistoricalcontext:inconversation,manywillalludetothe notoriouslycorruptCeausescuregime,which,post-1989,gavewaytoanequally corruptdemocraticgovernmentconsistingofmany“reformed”ex-Communist officialsandfrequentlyembezzledmoney.Thispersistentcorruptionultimately complicatedRomania’scaseforascensiontotheEU.Discussionsbeganin2000, yetthecountrywasonlyadmittedsixyearslaterontheconditionthatit demonstratedsufficient“politicalwilltoestablishingruleoflawandcombating corruption”(Ristei2010,348).However,Romania’sfightagainstcorruption

44

hasachievedlimitedsuccess.Forthepasttwodecades,therulinggovernments havemaintainedapatternoflegislatingbywayofgovernmentordinancesor attachingbillstomotionsofconfidence,therebyeithernegatingtheroleof Parliamentinpassinglegislationorthreateningitwithanotherelection(Ristei 2010,342).Additionally,theautonomousanti-corruptiondirectorate(Directia NationalaAnticoruptie,orDNA),witha38-million-dollarannualbudget, focuses“disproportionatelyoneffectivenessofprosecutionattheexpenseof reasonableness,”(Mendelski2020,251).Mendelski(2020)essentiallyarguesthat theDNAhasfocusedtoomuchonachievingguiltyverdictsratherthanactually identifyingandpreventingcorruption.Citingthefactthat,between2009and 2015,corruptionconvictionsrosefrom22to879peryear,Mendelski(2020) showsthatthehasteRomanianprosecutorshaveexercisedinconvictingthose accusedofcorruptionhasunderminedtherighttoafairtrialandultimately derailedthefightagainstcorruption(238).

Corruption,therefore,isamajoraspectofRomanianpoliticalculture: politiciansaccuseoneanotherofcorruptpracticesfrequently,andmanymajor protestsinthepastdecadehavebeeninresponsetopubliccorruptionofthe nationalgovernment.Thecountryexperiencedtwoyearsofalmost-dailyprotests from2017to2019inresponsetoaseriesofsecretly-passedbillsthat decriminalizedabusesofpowerresultingindamagesofunder$50,000and pardonedconvictionsoflessthanfiveyears.Over500,000Romanians participated,makingthemthelargestdemonstrationsinRomaniasincethe overthrowoftheCeausescuregimein1989.

SourcesofInstitutionalDistrust

Asaresultofcorruption,institutionaldistrustispervasiveinRomania,however itssourceonanindividuallevelremainsdisputed;inotherwords,whydocertain peopleexperiencehigherlevelsofinstitutionaldistrustthanothers,despiteliving inthesameenvironment?MishlerandRose(2001)analyzed1998surveydata from“post-Communist”societies(thatis,Bulgaria,theCzechRepublic, Slovakia,Hungary,Poland,Romania,Slovenia,Belarus,Russia,andUkraine)in anattempttoidentifythekeydriversofpoliticaldistrust(40).Theyfoundthat

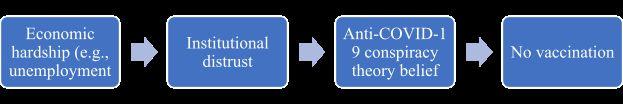

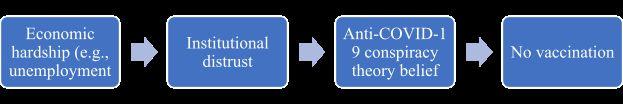

45