Modern Jewish Hero Rav Chanan Porat:

WITH GRATEFUL THANKS TO THE FOUNDING SPONSORS OF HAMIZRACHI THE LAMM FAMILY OF MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA יִחָרְזִמַּהUK EDITION VOL 5 • NO 5 SUKKOT & SIMCHAT TORAH 5783 120 YEARS OF RELIGIOUS ZIONISM Est. 1902

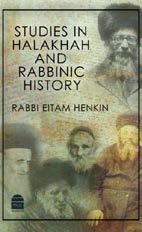

Rabbanit Chana Henkin pays tribute to Rav Eitam and Naama on their yahrzeit

PAGE 32

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks zt"l on the deep resonance of Sukkot in the 21st century

PAGE 18

Rabbanit Sharon Rimon on the arba'a minim

PAGE 21 ALSO INSIDE...

Kurt

Yechiel

Harvey

Doron

Danny

Reuven Taragin

Shani

Shani

Mizrachi is the global Religious Zionist movement, spreading Torat Eretz Yisrael across the world and strengthening the bond between the State of Israel and Jewish communities around the world.

Based in Jerusalem and with branches across the globe, Mizrachi – an acronym for merkaz ruchani (spiritual center)

was founded in 1902 by Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Reines, and is led today by Rabbi Doron Perez. Mizrachi’s role was then and remains with vigor today, to be a proactive partner and to take personal responsibility in contributing to the collective destiny of Klal Yisrael through a commitment to Torah, the Land of Israel and the People of Israel.

THE WORLD

PRESIDENT Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis CHAIR

TRUSTEES Steven Blumgart

Rabbi Andrew Shaw

Michelle Bauernfreund Matti Fruhman Andrew Harris Grant Kurland Sean Melnick David Morris

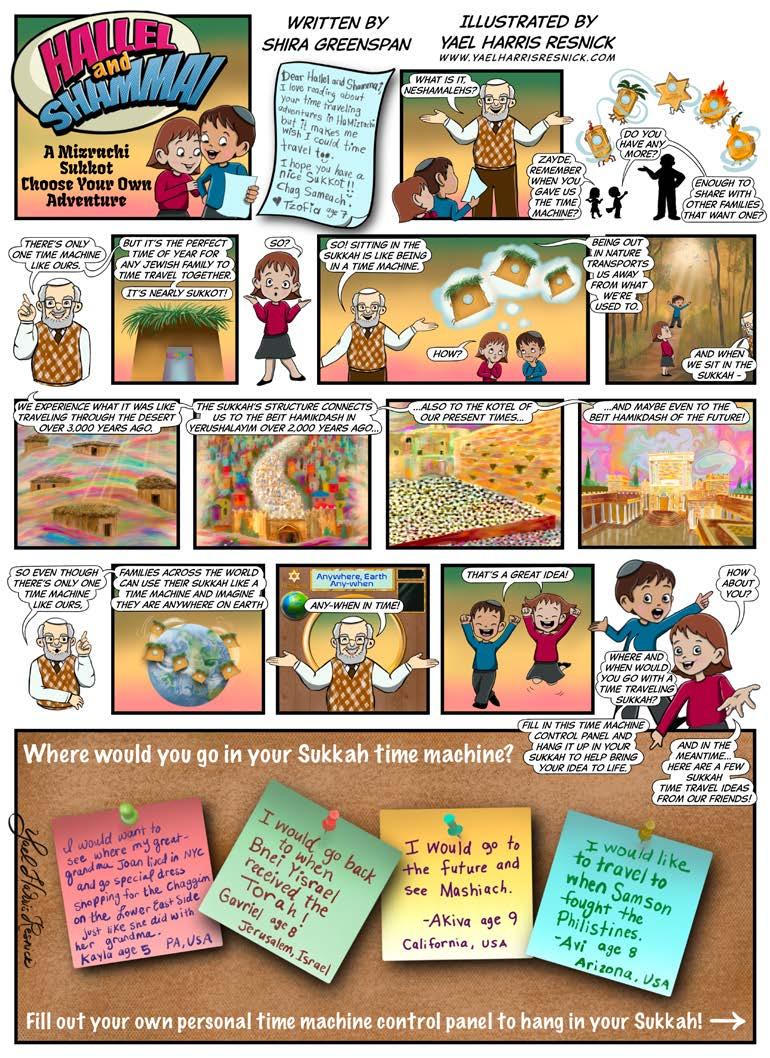

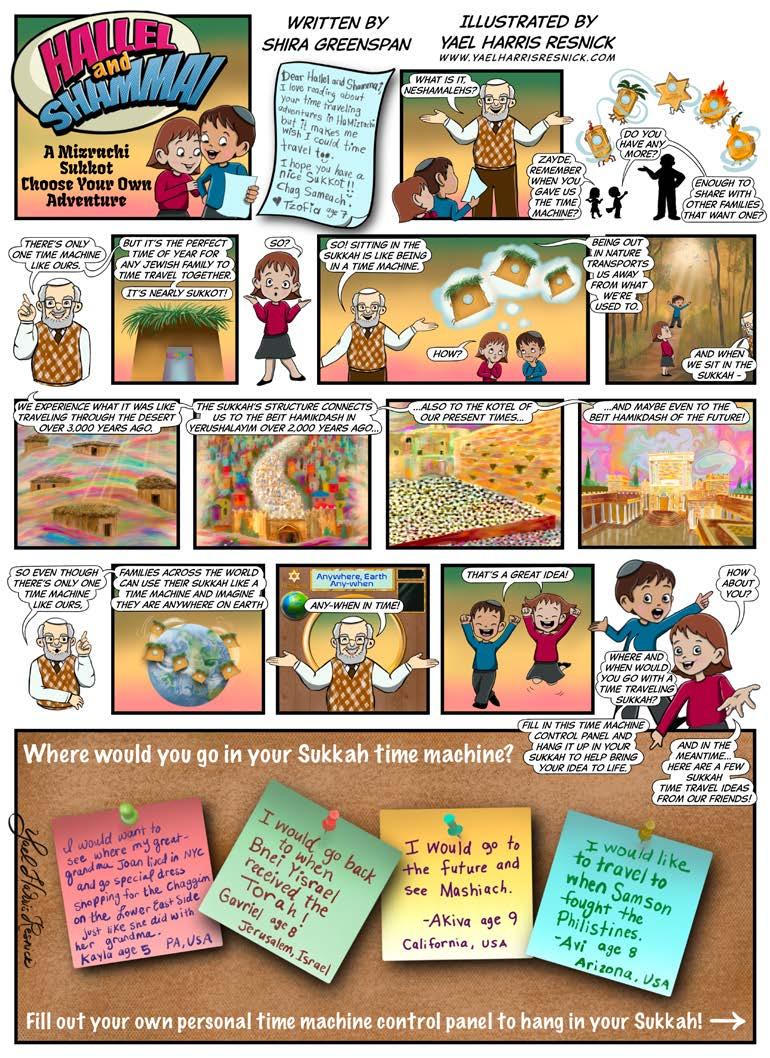

INSIDE REGULARS 4 Rabbi Doron Perez 27 Rabbanit Shani Taragin 38 Rabbi Reuven Taragin 49 Sivan Rahav-Meir 56 Aliyah Diaries 59 Food from Israel 61 Crossword 62 Hallel and Shammai JEWS VIEWS with PAGES 30–31 PAGES 11–17 COVER PHOTO In 1975, Rav Chanan Porat and Rav Moshe Levinger led hundreds of Jews to Sebastia in the Shomron to establish a new Jewish town. Moshe Milner took this iconic pho to, capturing the joyful pioneering spirit of the masses, led by a radiant Chanan Porat. 3 Rabbi Andrew Shaw 4 Rabbi Doron Perez 18 Rabbi Jonathan Sacks zt"l 20 Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon 28 Rabbi Reuven Taragin 42 Hallel and Shammai REGULARS The Extraordinary Life of Rav Chanan Porat zt”l PAGES 18–31 Sukkot & Shemini Atzeret Torah 120 YEARS OF RELIGIOUS ZIONISM Est. 1902 www.mizrachi.org www.mizrachi.tv office@mizrachi.org +972 (0)2 620 9000 PRESIDENT Mr.

Rothschild z”l CO-PRESIDENT Rabbi

Wasserman CHAIRMAN Mr.

Blitz CEO & EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN Rabbi

Perez DEPUTY CEO Rabbi

Mirvis EDUCATIONAL DIRECTORS Rabbi

Rabbanit

Taragin World

–

www.mizrachi.org.uk uk@mizrachi.org 020 8004 1948

OF

CHIEF EXECUTIVE

BOARD

To dedicate an issue of HaMizrachi in memory of a loved one or in celebration of a simcha, please email uk@mizrachi.org

EDITOR

Rabbi Elie Mischel editor@mizrachi.org | ASSOCIATE EDITOR Rabbi Aron White CREATIVE DIRECTOR Leah Rubin | PROOFREADER Daniel Cohen HaMizrachi is available to read online at mizrachi.org/hamizrachiPUBLISHED BY WORLD MIZRACHI IN JERUSALEM HaMizrachi seeks to spread Torat Eretz Yisrael throughout the world. HaMizrachi also contains articles, opinion pieces and advertisements that represent the diversity of views and interests in our communities. These do not necessarily reflect any official position of Mizrachi or its branches. If you don't want to keep HaMizrachi, you can double-wrap it before disposal, or place it directly into genizah (sheimos).

ORTHODOX ISRAEL CONGRESS PAGES 6–9 2 |

Rabbi Andrew Shaw

Earning Our Simcha

As a kid growing up in Kingsbury in the 70s and 80s, I loved Sukkot.

Sukkot meant the won derful Sukkah Crawl, when people opened their Sukkot to the commu nity. It was one of the highlights of the communal year. We would walk from sukkah to sukkah, eating, drinking, singing and having a fantastic time. Over the first two days of the chag and Shabbat Chol HaMoed, we could visit over fifty sukkot!

Then there was Simchat Torah, when the shul was filled with singing and dancing, when there were sweets everywhere and everyone was in a good mood. It was a special community atmosphere which enveloped all of us, from young children to grandparents, and unquestionably the highlight of the shul year.

But something always puzzled me.

Just before Sukkot, we observe Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. As a child, this stood out as a uniquely intense experience. The shul was so packed we even had an overflow service. People came that I never saw the rest of the year. And what did they come for? To sit in shul and pray (or just sit there) –for hours on end!

Then, when Sukkot and Simchat Torah came round just a few days later and the amazing fun began, the people who had come specifically for Rosh

Hashanah and Yom Kippur were nowhere to be seen. We were back to just the regular crowd.

Why?

The simple answer is that these people were “three-times-a-year Jews” – and so they tragically didn’t get to see the simcha of Sukkot. On a deeper level, however, these Jews sadly never learned a beautiful teaching of Rav Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev, the Kedu shat Levi

Rav Levi Yitzchak explains that there are two parallel holiday cycles in the Jewish year, each of which lasts 51 days. The “national holiday cycle” of the Jewish people begins on Pesach and culminates in Shavuot, while the “personal holiday cycle” begins with Rosh Chodesh Elul and culminates with Shemini Atzeret. Each of these holiday cycles demand hard work and effort to achieve spiritual growth. During Sefirat HaOmer , we literally count each day, as if to measure and track our spiritual toil. Our personal holiday cycle demands even more; first the repentance of Elul, and then the intense days of the Aseret Yemei Teshuva, the Ten Days of Repentance.

Only after the hard work of Sefirat HaOmer , Elul and the Aseret Yemei Teshuva do we reach days of great celebration. The final days of each of these cycles – Shavuot and Shemini Atzeret – are both called “Atzeret”; they

are both days in which we look back at what we have accomplished and celebrate together with G-d. Our hard work and simcha are bound up with one another; the incredible national and personal joy of these days is only possible because of the effort we invested beforehand.

Sadly, far too many Jews experience only part of the Jewish holiday cycle. They attend shul only for the Days of Awe and introspection, but do not return for the joyous conclusion of these days on Sukkot and Simchat Torah. It’s no surprise that their impression of Judaism is, as Rabbi Sacks zt”l said, “too much oy, not enough joy”. If only they would join us for Sukkot, they would experience the great sweetness and joy of Judaism, a joy unlike any other!

“You shall live in sukkot for seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in sukkot” (Vayikra 23:42).

May we soon see the day when all of Am Yisrael celebrates together on Sukkot, speedily in our days! Chag sameach!

Rabbi Andrew Shaw is the Chief Executive of Mizrachi UK.

| 3

Rabbi Doron Perez

THE IDEAL LEADER

vs. Davidian Politics

Israel is about to experience some thing almost unheard of in the history of democracy – a fifth election in less than four years!

For many years, the Israeli electorate has been politically split down the middle, unable to form a government with a stable ruling majority. The pros pects for this latest election look no different, with polls once again pre dicting deadlock and division.

This troubling reality has eroded our national sense of unity. The ongoing elections not only cost billions of shek els and make sustainable governance impossible, but also have a corrosive effect on our societal cohesion. When parties are in constant “election mode”, they are forever focused on the short comings of others, constantly sharp ening differences and undermining and delegitimizing political opponents. This counterproductive behavior leads to a continuous culture of criticism and condemnation. At times, the con demnations are so acerbic that they result in deep intolerance for the views of others and mutual hatred.

Destroying political rivals

How do disagreements deteriorate into delegitimization and even hatred?

When I am absolutely right and you are absolutely wrong, when my polit ical opponents are part of “the dark side”, it is only natural to view them

as an existential threat to our society. And once our political opponents are classified as “existential threats”, it becomes easier to justify distasteful tactics and behavior to combat those perceived threats. When battling “exis tential threats”, the ends justify the means!

When I am absolutely right and you are absolutely wrong, when my political opponents are part of “the dark side”, it is only natural to view them as an existential threat to our society.

This past year, the mistreatment of political opponents reached new heights. Some Knesset members now routinely shun one another, refusing to acknowledge or greet other members, and even encourage their followers to harass political opponents in shul and heckle them and their families. Some Knesset members frequently engage in the cancel culture so prevalent in our time, eschewing basic principles of civility and common decency.

On top of all this, lying, manipulation and deception have become ubiquitous

in the political milieu. Politicians are amongst the least trustworthy people in all of Western society, routinely tell ing the public what they want to hear and what will serve their personal interests instead of standing for what they really believe. Israeli politicians repeatedly make convincing campaign promises to potential voters, only to immediately do the opposite of what they promised following the election. Others deceive their coalition partners by exploiting tiny loopholes in order to avoid fulfilling their promises. Sadly, deceiving and double-crossing voters and coalition partners alike has become commonplace.

Machiavellian politics

The unscrupulous behavior of today’s political leaders has a cogent phil osophical basis. It is rooted in an uncouth, un-Jewish mode of political interaction, in which lying and decep tion are virtues, undermining political opponents is desirable and political ends always trump moral means. It is the political philosophy known as Machiavellianism.

A 16th century statesman and dip lomat, Machiavelli served his native Florence for 14 years. But when the Medici family seized power, he not only lost his position, but was tortured and banished from the city. In forced retirement, he wrote works of history

Machiavellian

4 |

and drama, but his lasting notoriety is due to his most famous work, The Prince.

In this watershed work, which ulti mately established him as the “father of political science”, Machiavelli drew upon his personal experiences and political studies to argue that poli tics has always been conducted with deception, treachery, and criminality. Machiavelli maintained that successful politicians should not abide by normal standards of morality and ethics. For successful politicians, the desired end always justifies the means, no matter how brutal or unethical. Rulers who hope to maintain their hold on power must know no moral limits. They must lie and deceive as needed, and should torment, torture and murder political enemies with impunity if they wish to secure and sustain their leadership. Most famously, he notes that for a ruler, “it is much safer to be feared than loved”.

In the decades after it was published, The Prince gained a fiendish reputation. By the end of the century, Shakespeare was using the term “Machiavel” to denote amoral opportunists, leading directly to our popular use of “Machi avellian” as a synonym for scheming villainy. Throughout the book, Machi avelli appears entirely unconcerned with morality, except insofar as it is helpful or harmful to maintaining power.

But not everyone has condemned The Prince. Some consider it to be a straightforward description of the evil means used by tyrannical and power-hungry rulers, while others see it as unsavory yet pragmatic realism with Machiavelli wishing to shatter popular delusions about what power really entails for those who wish to wield it. Either way, Machiavelli’s polit ical philosophy of realpolitik connotes deceit and deviousness, tyranny and treachery, where any means justify a political end.

Davidian politics

Diametrically opposed to Machiavel lian politics is the political leadership of King David – what we shall call “Davidian politics”. During David’s 40-year rule, he modeled a form of leadership so transformative that he has become known to posterity as ךֶלֶמַה דִוָד, King David, ‘the’ king par

excellence. So extraordinary was his leadership that the longed-for, future leader of Israel, the Messiah himself, must be a direct descendant of David.

David’s respect for his political adver saries is remarkable, and could not be more different from Machiavelli’s ideal prince. While David was a war rior who fiercely fought the enemies of

tribes of Israel. He desperately sought to overcome painful internal divisions between his tribe of Judah and the other tribes of Israel who appointed Saul and Ish-boshet as their kings. His lifelong goal was to heal the fractures of national society and forge a unified commonwealth.

Maimonides explains that the role of Jewish kings and political leaders is

So extraordinary was his leadership that the longed-for, future leader of Israel, the Messiah himself, must be a direct descendant of David.

ץֵבַקְל, “to unite our nation and to lead it” (Sefer HaMitzvot #173). In this passage, Maimonides is describing a time in which all the tribes of Israel are dwelling in the Land of Israel, and so the Hebrew word ץֵבַקְל does not mean “to gather the exiles” but rather “to gather together and unite the tribes of Israel”.

Israel, he was extraordinarily forgiving and consistently tolerant towards his political adversaries, a compassion ate attitude his own senior military brass and tribal leadership struggled to understand.

On several occasions, King Saul attempted to kill his loyal servant David, yet David twice refrained from harming him, even though his own life was in danger and he had every right to kill King Saul in self-defense. David also showed remarkable for bearance and forgiveness to Avner ben Ner and Amasa ben Yeter, chiefs of staff of the armies that fought against David on behalf of Saul’s kingdom and Avshalom’s rebel forces respectively. When Yoav surreptitiously murdered these men, David rebuked Yoav for his actions and publicly mourned them. When the Amalakite youth and brothers Ba’ana and Reichav joyously informed David that they had killed his political enemies – King Saul and Ish-boshet – David had them killed for daring to harm an elected king of Israel.

The national unifier

What drove King David to show such unusual mercy to his political adversaries?

David understood that the main role of the king of Israel is to unite the people. David knew that killing Saul or taking vengeance against political enemies could lead to an irrevocable split amongst the already divided

The king of Israel plays a critical role in the mitzvah of Hakhel – the momen tous unity gathering of the nation that took place every seven years in Jerusalem. On the first day of Chol Hamoed Sukkot, immediately follow ing a Shemitta year (such as this year!), the king would preside and read from the Torah before the entire nation. Rav Soloveitchik explains that the implica tion of this mitzvah is clear: the king’s role is to unify the nation!1

The book of Shmuel, which in many ways is the book of David, stands out as the blueprint for Jewish political leadership. It was David who bent over backwards to ignore prior insults, grievances and wars and to forgive others for the sake of unity, overcom ing the tribalism that had plagued the people of Israel for generations. And so it was David who laid the foundations for the Temple in Jerusalem, where Hashem’s presence could only reside among a people united as one.

In both Israel and around the world, we are today in desperate need of the Davidian mode of Jewish leadership. May Hashem grant us such leaders who will unite our people and rebuild the Temple, speedily in our days!

1. Sefer Birkat Yitzchak by Rabbi Menachem Genack, Parashat Shoftim; with thanks to Rabbi Josh Kahn for making me aware of this source. Rabbi Doron Perez is the Executive Chairman of World Mizrachi.

ונֵגיִהְנַיְו ונֵתָמֻא

| 5

THE WORLD ORTHODOX ISRAEL CONGRESS

Behind the Scenes

In April 2023, Jews all over the world will celebrate Israel’s 75th anniversary. In honor of this milestone and Mizrachi’s 120th anniversary year, World Mizrachi will host two exciting events in Yerushalayim, including a massive celebration of Yom HaAtzmaut and the inaugural World Orthodox Israel Congress for Jewish professional and lay leaders representing communities from across the world.

We sat down with Rabbi Doron Perez, Executive Chairman of World Mizrachi, and Rabbi Reuven Taragin, World Mizrachi’s Educational Director, to hear more about the plans.

Can you tell us more about the purpose of this cele bration and Congress?

Rabbi Doron Perez: One hundred and twenty years ago, the Mizrachi movement was founded to play a proactive part in the revival of the Jewish people and the building of a Jewish state – and to demonstrate that there is no contra diction between Zionism and authentic Torah values. On the contrary, they are indeed complementary!

One hundred and twenty years on, the Mizrachi movement remains deeply dedicated to the vision of our founders –but with an updated mission. Such a significant milestone provides a wonderful opportunity to appreciate being part of such a historic organization, the oldest still-existing movement in the World Zionist Organization. Even more importantly, we will reflect on our illustrious past in order to plan for a reinvigorated future as a relevant and revitalized Religious Zionist global movement.

At our Jubilee Yom Yerushalayim celebrations in Jerusa lem in 2017, Naftali Bennett, then Minister of Education, shared a powerful statement: “The State of Israel used to be the project of Jewish people; now, the Jewish people must be the project of the State of Israel.” This transformation

crystallizes our reinvigorated Mizrachi mission, in which Israel, as the center and heart of the Jewish world, must play a proactive role in the future of Jewish destiny all over the world. Times are changing, and an increasing number of Diaspora communities are turning to Israel for assistance. We must answer the call, and so Mizrachi is investing heavily in serving the needs of Diaspora communities. This is why we will be hosting the World Orthodox Israel Congress. Mizrachi is uniquely positioned to play a role on the global stage. With branches and affiliates in over 40 countries, World Mizrachi aims to galvanize a global community where the whole is much greater than the sum total of the individ ual parts. Mizrachi leaders and affiliates play crucial roles in thousands of communities, schools, college forums and youth movements around the world. We aim to connect and galvanize these communities and join these institutions together to create a powerful, networked and interconnected global community. We will bring institutional leaders – rab binic, educational and lay leaders alike – from Israel and the Diaspora to work together to address the greatest challenges of our generation and create effective mechanisms to con tinue this work over time.

Facing page: The Yom HaZikaron ceremony at the Kfar Etzion cemetery, during Mizrachi's Israel70 mission in 2018. (PHOTO: DAVID STEIN)

6 |

Why is the Congress being convened in Israel and at this time?

RDP: The historic milestone of the 75th anniversary of our miraculous State of Israel provides an ideal opportunity. Now more than ever, Diaspora Jewry is defined by its rela tionship with the State of Israel, and so it is critical that we all deepen our appreciation of the enormous spiritual and religious significance of Israel today. To this end, we are planning mega events to commemorate Yom HaZikaron and celebrate Yom HaAtzmaut. These will include a “Mothers of the Nation” event at Binyanei Ha’uma for Yom HaZikaron and a Yom HaAtzmaut concert featuring Ishay Ribo, along with other exciting events.

The Congress is timed so that the many community leaders coming to Israel for these special events can conveniently stay on to participate in the Congress which will take place right after Yom HaAtzmaut. Those community leaders who need to be in their communities for Yom HaZikaron and Yom HaAtzmaut can join immediately thereafter to participate in our Congress.

This will be the first worldwide Mizrachi gathering since the pandemic. How will the experiences from the last two years impact the meaning and significance of the Congress?

Rabbi Reuven Taragin: During the COVID pandemic, World Mizrachi quickly moved many of its activities online, enabling us to continue reaching global audiences at a time when our regular programs of scholars-in-residence and mis sions were not possible. Now that the pandemic has largely

receded, we are delighted – and deeply appreciative – to have returned to in-person education, which is certainly the ideal.

At the same time, the global pandemic ironically enabled us to significantly expand our reach to even more countries around the globe, effectively shrinking the distance between Mizrachi branches and communities. It also brought many of our branches closer to one another; when everyone was stuck at home on Zoom, it didn’t matter if you were speaking with your neighbor or someone living thousands of miles away. The pandemic effectively shrunk the distance between Mizrachi branches and communities.

What excites you most about the Congress?

RRT: Perhaps not since our exile began nearly 2,000 years ago has there been such a gathering! Bringing institutional representatives of the Orthodox community in an official capacity in a centralized way is truly unique.

Before the telecommunication revolution, such represen tation was harder and less necessary. Modern technology has created a global village, bringing the world much closer together. Our global Orthodox village presents us with global challenges, which require coordinated global responses.

The Congress will have representatives of Orthodox schools, shuls and institutions from over 40 countries across the world, a truly unprecedented gathering. This will allow us to develop international support networks for Orthodox professional and lay leaders, essentially creating a global community that can continue long after the Congress is finished.

| 7

You mentioned communities working together. How do you envision this when the needs and priorities of our global communities are so diverse?

RRT: Each community, city, and country has its unique issues and needs, and local and national organizations to address them. That being said, many of the issues we face are common to all (or many) of our communities around the world. Working on these issues together will benefit all of us. Creating an effective network will help each community benefit from each other’s wisdom, experience, and resources.

The Congress will bring the Orthodox world together and create a representative body that can serve as a voice and address for world Orthodoxy and a forum in which our communities can work together to face common challenges.

Who is invited to the Congress?

RRT: We are inviting the professional and lay leaders of each community organization to join us. In order to properly represent the Orthodox community, the Congress will include all types of Orthodox organizations, including shuls, schools, youth groups, and all constituencies, including men, women and youth. There will be forums for shul rabbis, shul lay leaders, school principals, school lay leaders, a special women’s leadership forum, and youth and young professionals forums.

In addition, we are also arranging forums for Orthodox profes sionals in fields that pose unique challenges to Orthodox Jews, such as psychology, and are important to our community’s voice and influence, such as media.

Each of these forums will address the issues faced by their orga nizations and also interact with one another in a meaningful way.

Why does the Orthodox community need its own Con gress? Aren’t we part of the broader Jewish community?

RRT: We are certainly part of the broader Jewish community and we will continue to do our best to strengthen our kesher with all Jews in the context of the World Zionist Organization and other broad organizations. Ultimately, we are all Hashem’s children. That being said, the Orthodox community faces unique challenges and needs a voice that can address these issues from an Ortho dox perspective and represent our communities to government agencies and ministries.

How can HaMizrachi readers get involved?

RDP and RRT: We are inviting the leaders of all Orthodox com munity organizations to join us in Jerusalem. Please speak to the leadership of your shuls, schools and other organizations to ensure they will be represented.

It is important for each organization to be represented by both professional and lay leaders, and to include both men and women in their delegation.

For more details or to register on behalf of your organization, visit mizrachi.org/israel75 n

Rabbi Doron Perez speaking to press outside Independence Hall, Tel Aviv at Mizrachi's Israel70 celebrations. (PHOTO: DAVID STEIN)

Sivan Rahav-Meir interviews the parents of Gilad, Naftali and Eyal, the three Israeli boys who were murdered in 2014, and whose story gripped the Jewish people. (PHOTO: DAVID STEIN)

Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis speaking at Mizrachi's Yom Yerushalayim conference. (PHOTO: DAVID STEIN)

At the opening

Rabbi Doron Perez speaking to press outside Independence Hall, Tel Aviv at Mizrachi's Israel70 celebrations. (PHOTO: DAVID STEIN)

Sivan Rahav-Meir interviews the parents of Gilad, Naftali and Eyal, the three Israeli boys who were murdered in 2014, and whose story gripped the Jewish people. (PHOTO: DAVID STEIN)

Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis speaking at Mizrachi's Yom Yerushalayim conference. (PHOTO: DAVID STEIN)

At the opening

of

Mizrachi's mega-event celebrations for Yom Yerusahalayim

50. 8 |

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND TO REGISTER: MIZRACHI.ORG/ISRAEL75 Wednesday April 26 – Friday April 28, 2023 ג״פשת רייא ז–ו Binyanei Ha’uma Conference Center, Yerushalayim An unprecedented gathering of leaders and representatives of Orthodox organizations and communities from over 40 countries. MARKING 120 YEARS SINCE THE FOUNDING OF MIZRACHI USING OUR PAST TO INSPIRE OUR FUTURE THE WORLD ORTHODOX ISRAEL CONGRESS REGISTERTOREPRESENT YOURCOMMUNITY

Rav Chanan Porat zt”l

An Introduction by Rabbi Aron White

Every society is shaped and defined by its heroes. From sports teams to local synagogues, from small towns to nations, each community possesses certain individuals who become entwined in the fabric of its history, whose individual lives become the embodiment of the society’s ideals and dreams.

Who are the heroes of the State of Israel? In the early decades of Israel’s existence, the heroes of Israel came largely from the secular Labor Zionist camp. From the heroism of Joseph Trumpel dor at Tel Hai, to Ben-Gurion and Weizmann the architects of the State, and then to early military heroes such as Moshe Dayan and Ariel Sharon, the Israeli hero was strong and secular, a new type of Jew who radically broke from the traditional religious mold. Professor Dov Schwartz of Bar-Ilan University argues that this led to a Religious Zionist inferiority complex; without heroes, they felt themselves to be playing only a peripheral role in building the State of Israel, merely supporting the Labor Zionist camp.

Rav Chanan Porat changed everything. During the dark and pes simistic years that followed the trauma of the Yom Kippur War, Rav Chanan burst onto the public scene – young, bright-eyed, idealistic, and energized. A student of Rabbi Tzvi Yehudah Kook and a passionate Religious Zionist, he led a spiritual revolution that invigorated and transformed the Religious Zionist community and vaulted the community to a leadership role in broader Israeli society. For the next five decades, he led the Jewish people back to Yehudah and Shomron, built numerous Torah institutions and

brought his unique perspective to the halls of the Knesset. He was the first Religious Zionist Israeli hero.

“When King David would study Torah, he would be soft as a worm, but when he would go out to war, he would be as tough as wood” (Moed Katan 16b). Like King David, Rav Porat cannot be labeled or categorized in the way of most Jewish leaders. He was a leader revered by thousands, yet maintained a lifestyle of utter simplicity. He could be fearless and unwavering in pursuit of his goals, spending sleepless nights campaigning to keep Kever Rachel under Jewish sovereignty and for greater assistance for the thousands of Ethiopian Jews, but was a kind and gentle teacher of Torah who made time for students of all backgrounds and levels of observance. He was a leading student at the right-wing Yeshivat Merkaz HaRav, but also a founder of the open-minded Yeshivat Har Etzion. A fervent Religious Zionist, he nevertheless developed close and meaningful relationships with secular Israelis.

Though his status within Israel’s Religious Zionist community is legendary, little of his life’s work has been translated or dissem inated in English to date. In commemoration of his 11th yahrzeit, we are honored to dedicate this edition to his memory. May the sweetness of his Torah and the powerful example of his extraor dinary life continue to inspire us and generations to come.

A special thank you to Effie Rifkin, a close student of Rav Porat, for his help with this edition.

(PHOTO: RACHEL PORAT) | 11

And Your Children shall Return to their Own Borders

Rav Chanan Porat zt”l

Anyone who hopes to thoroughly deal with the question of “what is Religious Zionism” and “who is a Religious Zionist” cannot be satisfied with an abstract or theoretical discussion but must rather examine the way Religious Zionism has left its mark on the real-world return of Am Yisrael to Eretz Yisrael in our time and its impact on the Torah, the nation and the Land.

One great enterprise in which Religious Zionism has played a foundational role and likely would not have occurred without it is the settlement of Yehudah and Shomron (Judea and Samaria). My goal here is not to list the historical or geographical facts of the settlement movement, but rather to examine the idea behind the movement and use it to shed light on the uniqueness of Religious Zionism, which challenges the premises of ‘safe haven Zionism’ and establishes in its stead a new but ancient alternative: ‘redemptive Zionism’.

The settlement of Yehudah and Shomron after the Six-Day War began with a handful of young dreamers who went up, a few months after the war, to reestablish the homes of their parents that were destroyed in Gush Etzion in 1948. Since then, the settlements have grown and flourished from a small, tender seedling to a large enterprise of about 300,000 souls [currently, there are about 500,000 Jews living in these areas – Ed.]. Today,

the movement is like a tree with deep and powerful roots which no wind can succeed in uprooting.

Now, after over forty years of successes and failures, achievements and crises, we can look back with satisfaction: we climbed the mountain and succeeded! We merited, with Hashem’s kindness, to withstand the double challenge of Psalm 24: “Who shall ascend the mountain of Hashem, and who shall stand in His holy place?”

Climbing the mountain was certainly difficult. Kol hatchalot kashot, all beginnings are hard and demand effort and courage. But no easier, and perhaps even more difficult, is the task of standing on top of the mountain and holding onto it permanently. Because in a certain sense, kol hatchalot kalot, all beginnings are easy; the enthusiasm and joy of youth inherent in the act of pioneering obscures the hardships and difficulties. But [as the poet Rachel Bluwstein writes,] as the years go by, “the gold is hidden and the peaks have become a plain.” Routine can gnaw at and cool the initial enthusiasm, and those who have climbed the mountain may get lost in smallness and descend from the very mountain they climbed.

This is why the challenge hidden in the second part of the verse is so great: “and who shall stand in His holy place?” For this, not only the precious qualities of “he who has clean hands and

(PHOTO: HOWIE MISCHEL) 12 |

a pure heart” are needed, but also the third trait listed in the Psalm: “who has not taken My name in vain, and has not sworn deceitfully,” someone who not only promises but knows how to fulfill, with sacrifice and diligence.

From this perspective, we can say confidently that after forty years of climbing the mountain, the stability and strength of the settlement movement is no longer in doubt. No sane person can any longer claim that this movement is a passing episode of some crazy settlers who jump frantically from hill to valley and who will ultimately come down from the mountain and return to their homes.

In many ways, the settlers of Yehudah and Shomron are continuing the legacy of the great early pioneers of Zionist history, before and and after the founding of the State, who settled the Galil and the Negev, on mountains, lowlands and valleys. Many of the tests these earlier generations had to overcome are being repeated in the settlement of today: the physical difficulties, the security dangers, the societal challenges, the struggle with government institutions, and more. But there are also significant differences, some due to the passage of time, but the most important of which go to the heart of the issues.

The Jewish settlers of Yehudah and Shomron have been defined, through all the years, by a great faith in the word of G-d, who has returned the captives of His people and returned His children to their borders. Its founders saw the Six-Day War as a critical part of the process of our return to the Land and felt deeply that the redemption of Yehudah and Shomron in the war obligated them to act. Not to abandon these lands to our enemies but to settle them, as the prophet Yirmiyahu called out to the people of Israel: “Return, O virgin of Israel, return to these, your cities” (Yirmiyahu 31:20). For the founders of Jewish settlement in Yehudah and Shomron, the Zionist idea does not stem from the need to find a safe haven for the Jewish people, as Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau argued, nor from the desire to rebel against the old world and to build a new society in Israel, as so many from the second and third Aliyot imagined they would do.

The settlement movement was led from the very beginning by the students of the great “seer”, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook and his son, Rav Tzvi Yehudah, who continued his path. Before the eyes of all those who climbed the mountain were the powerful and penetrating words of Rav Kook in his letter to the leaders of Mizrachi almost 100 years ago. In this letter, Rav Kook strongly rejected the saying that prevailed in the Zionist movement of the time, that “Zionism has nothing to do with religion”. In its place, he wrote that “the source of Zionism is the Tanach” – that only the Tanach gives deeper meaning to Zionism.

More than this, Rav Kook strongly rejected belief in Zionism as a safe haven for Jews: “The desire of a hated nation to find a safe haven from its pursuers is not enough to infuse this extraordinary movement with life. A holy nation and the segulah of all peoples, the lion cub of Judah has awoken from its long slumber and is returning to its inheritance, ‘to the pride of Ya’akov whom He loves’ (Tehillim 47:5)”.

This great spirit beats in the heart of those who climb the mountain and is the inner point that gives life to the settlement movement, even as it has grown tenfold and many of its newer settlers know little of Rav Kook’s words.

It is worth noting that settling the Land with an outlook of Biblical faith did not begin with Gush Emunim in the wake of the Six-Day War but rather is rooted in the accomplishments of the early Religious Zionists, such as the religious kibbutzim and the moshavim of HaPoel HaMizrachi, who built settlements throughout the Land.

At the same time, something significant changed in the wake of the Six-Day War. Before the war, Religious Zionism was merely one voice in the larger Zionist movement. After the war, it became the dominant voice of Zionism, leading the settlement movement and determining the agenda of the Zionist movement. If before the war Religious Zionism served as a bridge between different parts of the nation, after the war it became the bridgehead of the nation, shaping the orientation of the entire State.

| 13

The difference between ‘safe haven Zionism’ and ‘redemptive Zionism’ is not merely theoretical, but has several practical consequences. ‘Safe haven Zionism’ is driven by the fear of antisemitism, and so in places where antisemitism is not open or widespread – like America and Canada – there should be no need to promote Aliyah.

And if living in Israel should prove to be more dangerous than living in exile, there is no reason to remain here. But according to the worldview of ‘redemptive Zionism’, a Jew has no place in exile. The motivation to make Aliyah is driven by the desire to be attached to the Land and the nation.

‘Safe haven Zionism’ does not assign any unique importance to the Land, and certainly not to every inch of Eretz Yisrael, and so it will happily give up Yehudah and Shomron, for the Land is merely a means to a different end. By contrast, ‘redemptive Zionism’ sees the attachment of the nation to its Land as having inherent value. The bond between Am Yisrael and Eretz Yisrael is like that between the body and the soul; uprooting Jews from any part of the Land is like cutting a limb off a man’s body.

The most important difference is that ‘safe haven Zionism’ reduces the mission of Zionism to ensuring the physical security of the State, ignoring the question of the State’s Jewish character and culture. But for redemptive Zionists, the ingathering of the exiles and the establishment and security of the State are merely the first steps – each significant in their own right – of the return to Zion. “The song is not over, it has just begun.” We still await many more stages of redemption, establishing a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation”, the return of G-d’s shechinah to Zion, the establishment of the Davidic kingdom and the building of the Beit HaMikdash – the key to repairing the world with the kingdom of the Almighty…

The struggle between these two forms of Zionism is at the center of today’s political and social debates. The spiritual and educational world woven and shaped by the settlement movement poses a great challenge to the broader Zionist movement, forcing it to ask itself from whence it came and where it is headed. This is not an easy struggle; the settlement movement has increased passion and Jewish identity, but it has also caused painful reactions and animosity that reached their peak during the forced separation from Gush Katif and other settlements. Nevertheless and despite everything, the great settlement movement in Yehudah and Shomron serves as a solid rock in the middle of a stormy sea, calling out to our mother Rachel: “Refrain your voice from weeping, and your eyes from tears, for your work shall be rewarded, says Hashem; and they shall come back from the land of the enemy. And there is hope for your future, says Hashem; and your children shall return to their borders” (Yirmiyahu 31:15–16).

And to all the weak-minded who seek, G-d forbid, to uproot the children from their borders… [know this]: “The grass withers, the flower fades; but the word of our G-d shall stand forever” (Yishayahu 40:8).

Translation by Rabbi Elie Mischel from “Ha’Agalah HaShlishit: Tzionut HaDatit B’Yameinu Mahu”, 353 (2009). (PHOTO: RACHEL PORAT) 14 |

I Will Not be Afraid, for G-d is with Me!

“W

hoa, whoa, what’s this?”

My father was standing over me, a bursting knapsack slung over his left shoulder.

“Nothing,” I said.

He looked at the salty streaks my tears had made upon on my face and stooped toward me. “What happened?”

I began crying again. Between ragged breaths, I told him the whole story: how my sister Ayelet had stood there and what I’d said and how we’d run away from her, and how the kids had imitated her and laughed at her, and so had I, because I’d been embarrassed of Ayelet and afraid they’d laugh at me.

“And where is Ayelet now?” asked my father.

“At home,” I said. “With Mom.”

My father was silent. He often thought before he started talking, and I didn’t always have the patience to wait. But sometimes crying makes everything a little easier, and you can deal with silence longer.

In the end, my father said, “We Porats aren’t afraid or embarrassed by anyone or anything in the world.”

I wasn’t crying anymore. I looked at him.

“I always remind myself,” said my father, “that if I need to be embarrassed, I need only be embarrassed before G-d and my own heart.”

“In front of G-d,” he explained, “because He is the Creator of truth and justice, and knows when I haven’t been honest with myself or others, and in front of my heart because it was created in the image of G-d, and if I listen to it carefully, it knows what the right thing to do is and whether it’s even worth my while to listen to what other people are saying.”

A raindrop fell on my father’s head. He raised his face skyward and smiled. “Shall we go inside now?”

“Wait,” I said, looking at him in doubt, “you really aren’t afraid of anyone?”

“Of people?!” he said with horror. “Not in the least!”

I wasn’t convinced. “I don’t believe you,” I said.

“I mean,” he explained, “I do get scared. Everyone gets scared. But I overcome it right away. Like a lion!” My father punched the air with excitement.

He had a kind of gesture like that, meaning “Onward!” or “Full speed ahead!” or sometimes “Let’s dance!”

“When I start getting scared,” my father said, “I think right away about what King David said. You know it from the tefillah

My father, as if he were King David himself, began to cry out:

,אָריִא יִמִמ יִעְׁשִיְו יִרֹוא

“Hashem is my light and my salvation. Whom shall I fear?”

,דָחְפֶא יִמִמ יַ

“Hashem is the stronghold of my life. Of whom shall I be afraid?”

יִרָׂשְב תֶא לֹכֱאֶל םיִעֵרְמ יַלָע בֹרְקִ ,ולָפָנְו ולְׁשָכ הָמֵה יִל יַבְיֹאְו יַרָצ

“When evildoers approach me to consume my flesh, when my oppressors and enemies come toward me, they stumble and fall!”, my father called loudly.

הֶנֲחַמ יַלָע הֶנֲחַת םִא, “If a camp encamps by me…” prompted my father.

יִבִל אָריִי אֹל, “My heart will not fear,” I answered from memory.

הָמָחְלִמ יַלָע םוקָת םִא, “If war comes upon me…” he sprang to his feet.

I also jumped up. ַחֵטֹוב יִנֲא תאֹזְ ב, “In this do I trust!”

“Exactly,” my father laughed. “When we have faith in G-d, we have faith in ourselves too, and we don’t pay attention to people who laugh at us.”

“Also,” he added after a moment’s thought, “we do fewer things we’re embarrassed of later on.”

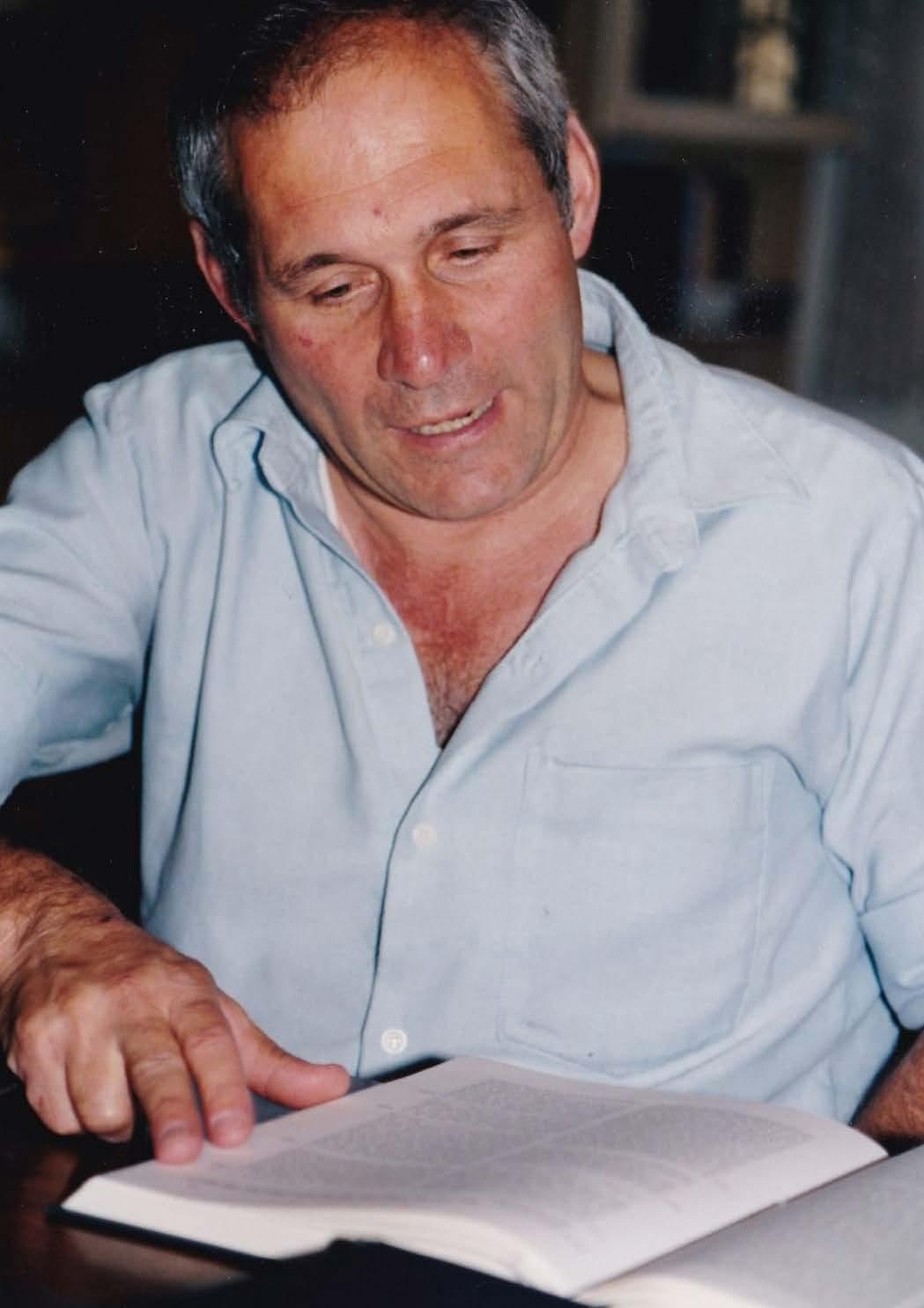

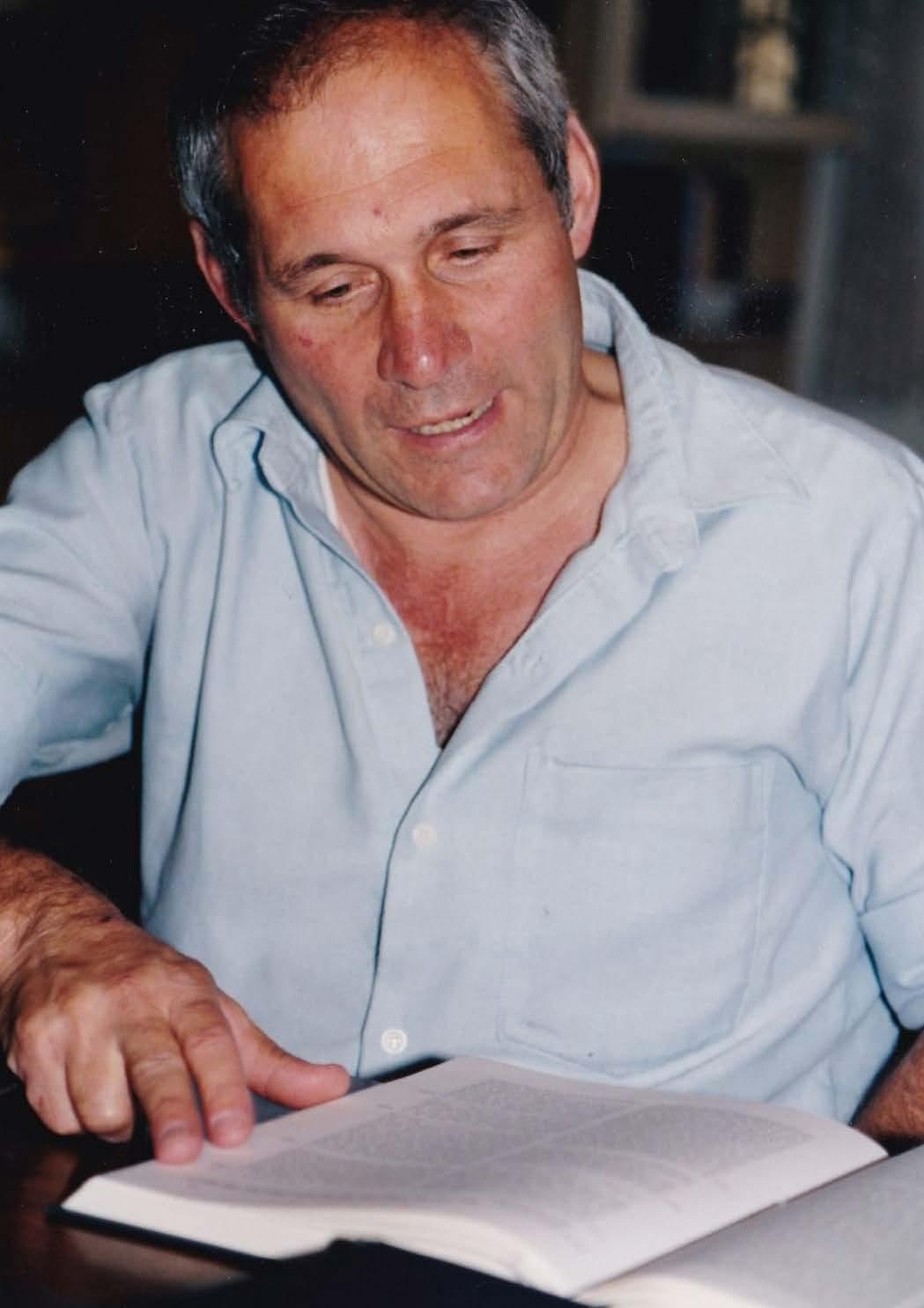

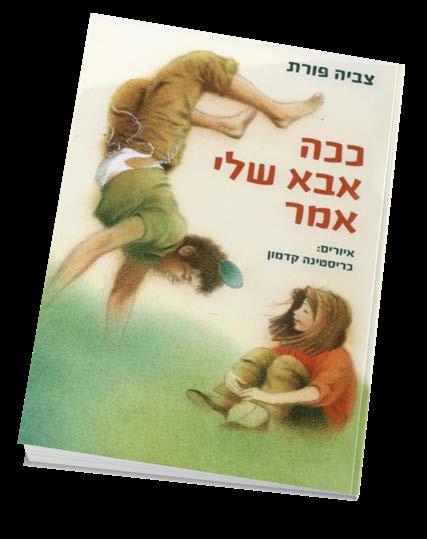

Tziviya Porat Mandel is Rav Chanan Porat’s daughter. “That’s What My Father Said” is her first book and tells a story of family, love, growing up and longing.

Tzviya Porat Mandel

Tzviya Porat Mandel

| 15

Rav Chanan Porat: An Eretz Yisrael Torah Scholar

Rabbi Shlomo Aviner

Because of the great humility of my beloved friend Rav Chanan Porat zt”l, because of his simple clothing and his lack of airs, many did not realize that a true Torah scholar stood before them, one of the most brilliant students who flourished at Yeshivat Merkaz HaRav. And they certainly didn’t realize that was ordained as a rabbi! Rav Chanan did not desire to make the Torah “a spade with which to dig”, but rather made himself into a spade to dig into the depths of Israel’s soul. All who knew him cannot but admit that this noble Jew lived what he preached.

This brave paratrooper was chosen by Divine Providence to be among the fighters of the Six-Day War and the liberators of Jerusalem, for he understood that the inner holiness of the nation is the supreme guarantee of its existence. But the Land of Israel must not only be conquered but also settled, and so he left the beit midrash and was moser nefesh to reestablish Kfar Etzion. More precisely, he invested his nefesh, his soul, his spiritual and Torah life, in the settlement of the land. He also literally gave his body and life to his people. In the Yom Kippur War, he was very seriously wounded on the southern front, and was saved only by the grace of G-d. When he recovered he became one of the founders of Gush Emunim and the settlements in Yehudah and Shomron

But he was not only interested in the Torah and the Land; he was also interested in people . Through his Gesher seminars he brought together

religious and so-called “secular” Jews; though in truth, no Jew is truly secular, for every Jew has a holy soul. These three passions of Rav Chanan are not really separate matters. Rav Chanan liked to talk about a discussion he and his friends once had at Merkaz HaRav. “What is more important – the Torah, the people or the land?” They turned to Rav Tzvi Yehudah with this question, who replied with a smile: “We are concerned with shleimut, with wholeness.” This was Rav Chanan’s guiding principle, that everything is one. And so even as he was very busy with his public activities, Rav Chanan did not stop studying and teaching Torah. In particular, he illuminated paths for those in search of faith; his book ׁשֵ קַבְמ יִכֹנָא יַחַא, “In Search of my Brothers ”, clarifies the deepest foundations of our faith in a language and style that find a way to the hearts and minds of all thinking people. But Rav Chanan’s greatest sacrifice for Am Yisrael was his decision to enter the Knesset. That difficult and dark place can wear down even the noblest people! But though he spent many years in that complicated maze, he remained holy and pure, never falling in love with his position. Indeed, he twice resigned his seat in the Knesset to allow others to take his place. Rav Chanan served in the Knesset for the sake of Heaven, working tirelessly for the people of Israel in whatever way he could.

After retiring from politics, he was one of the founders of Herzog College, teaching there, at Yeshivat Beit Orot,

Machon Meir and many other yeshivot That is when it became clear to all that he was truly a great and profound Torah scholar. He also humbly edited a Torah newsletter, רֹואָה ןִמ טַעְמ, “A Little of the Light” [later published as a popular set of books on the weekly parasha], a work that contains much light – though it is not a blinding light, but rather a gentle and illuminating light.

What did Rav Chanan not do? He had a regular radio show on Galei Yisrael Radio, and was one of the founders and heads of the Orot HaChessed association that provides food and electrical products and clothes to the underprivileged.

He was the epitome of the “Eretz Yisrael Torah scholar”, a man of redemption whose spirit pulsates among us and in all our works, and will illuminate them forever.

“We must always look ahead.” “What can I do to bring new spiritual strength to the nation?” “How can we ensure the light of our people will not dim?” These thoughts never left Rav Chanan. Indeed, Torah scholars have no rest, neither in this world nor in the next.

Rabbi Shlomo Aviner is the Nasi of Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalayim (formerly known as Ateret Cohanim) in Jerusalem, former rabbi of Bet El and one of Religious Zionism’s leading thinkers.

(PHOTO: HOWIE MISCHEL) 16 |

Rav Chanan Porat: For the Honor of Heaven

Rav Chanan Porat zt”l was a unique ish eshkolot, or ‘renaissance man’, a Torah scholar and poet, paratrooper and educator, in love with the nation, Torah and Land of Israel. A founder of Gush Emunim, he was also a pioneer, builder and eventually a Member of Knesset. Rav Chanan was often sought out for his comments on current events, for he spoke with passion and wit, and was never shy about sharing his opinions.

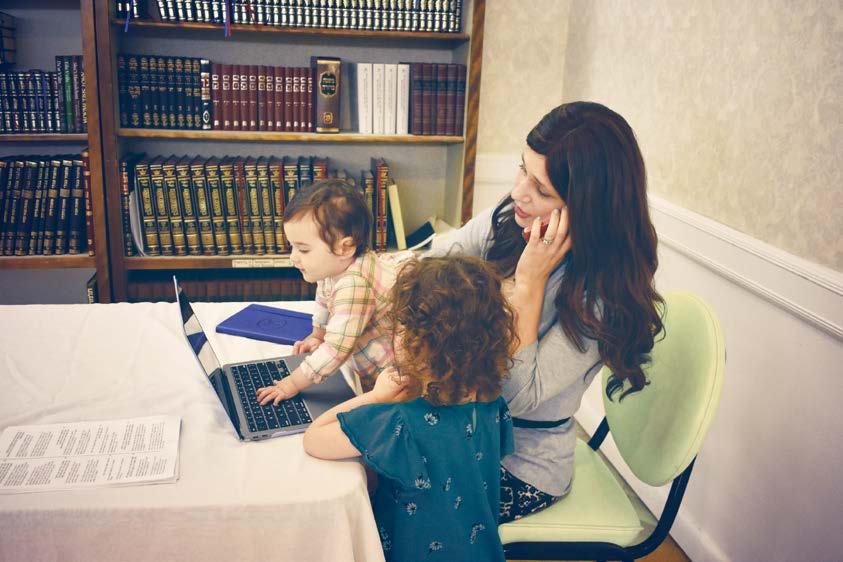

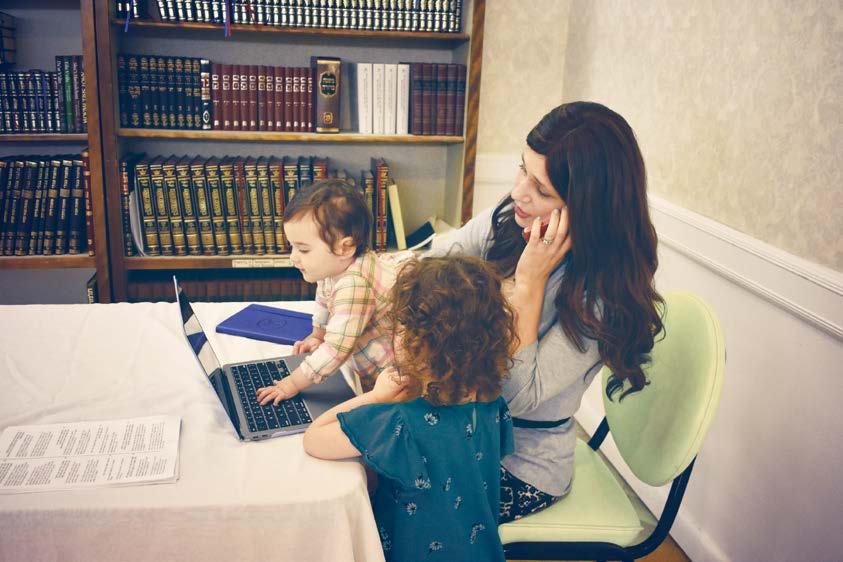

Rav Chanan’s daughter, Tirtza, describes how one afternoon, he was sitting with a sefer open in front of him, pen in hand, writing his weekly Torah column while fielding non-stop calls on two different phone lines. At one point, the producer of a popular prime-time Israeli television show called to ask Rav Chanan if he would appear on the program.

In the midst of the hustle and bustle, Rav Chanan paused for a moment, furrowed his brow in contemplation and calmly asked the producer, “Do you think that my participation will give nachat ruach to HaKadosh Baruch Hu, pleasure to the Holy One? Will it be marbeh k’vod Shamayim, will it increase the Divine honor?”

Taken aback, the television producer was unable to answer definitively, and offered a hesitant “I’m not sure…”

“Well, if that is the case, then I will have to pass. Thank you.”

In a life that touched practically every aspect of Jewish life in Israel this past half-century, Rav Chanan was at the forefront of efforts to build and create a thriving Jewish society in our home land. He would often speak of the need for faith and purpose, and cite the tragic failing of the meraglim, the spies sent from the wilderness to report on the Land, an episode that led to gener ations of exile.

According to Ramban, while the end of the story is disastrous, the meraglim had holy intentions. In the wilderness, the people were escorted and sustained by the well of Miriam, led by a pillar of fire and surrounded by clouds of glory. Their sojourn in the desert was one of constant miracles and revealed Divine providence. Why, they consid ered, should they enter the Land of Israel only to be forced to engage its inhabitants in battle, build cities and deal with the complex material needs of a worldly society? Why should they enter a situation in which they had to put aside spiritual pursuits to work the land and cultivate fields, when they were enjoying a life of attachment to G-d and being nourished by Manna that fell from Heaven?

The meraglim hoped to keep us in the ideal spiritual environment of the wil derness, nestled in a womb-like experi ence where we wouldn’t be busied with ‘lowly’ worldly affairs that could inter fere with our connection to Hashem. What they failed to take into account was actually the most important factor: ratzon Hashem, the Divine will. By allow ing ourselves to be persuaded by the spies, we rebelled against Hashem’s will.

When we are so certain in our belief of the righteousness of our cause, we can become filled with kavod atzmi, self-importance. This is a subtle act of rebellion, for kavod belongs only to Hashem. When grasping kavod for our selves, Hashem’s kavod is diminished in the world, so to speak.

After Moshe’s plea for forgiveness, Hashem says, “I have forgiven them in accordance with your word. However, as surely as I live, v’yemalei k’vod Hashem et kol ha-aretz, the glory of G-d fills all of the earth… all the people haro’im et k’vodi, who while seeing My glory and the signs that I performed in Egypt and in the desert have tested Me these ten times and not listened to My voice…

they will not see the Land that I swore to their fathers” (Bamidbar 14:20–23).

Hashem’s glory and presence, His kavod, fills the earth; there is no place devoid of Hashem. The ratzon Hashem is that we should reveal this omnipresent glory throughout “all the earth” by creating a dira b’tachtonim, a dwelling for Hashem in the ‘lower’, physical world. Our mun dane, physical day-to-day acts are them selves a revelation of Hashem on earth.

While holy and well-intended, the mistake of the meraglim teaches us how clear we must be regarding our higher purpose: to bring nachat ruach to Hashem and be marbeh k’vod Shamayim Like Rav Porat, may we have the cour age to “pass” on any offer that is not aligned with Hashem’s desire to dwell here, in our world and within ourselves.

Rabbi Judah Mischel

Rabbi Judah Mischel is Executive Director of Camp HASC, Mashpiah of OU-NCSY, founder of Tzama Nafshi and the author of Baderech: Along the Path of Teshuvah.

A member of the Mizrachi Speakers Bureau mizrachi.org/ speakers

(PHOTO: RACHEL PORAT)

(PHOTO: RACHEL PORAT)

| 17

Sukkot for our Time

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l

Of all the festivals, Sukkot is surely the one that speaks most powerfully to our time. Kohelet could almost have been written in the twen ty-first century. Here is the picture of ultimate success, the man who has it all – the houses, the cars, the clothes, the adoring women, the envy of others – he has pursued everything this world can offer from pleasure to pos sessions to power to wisdom and yet, surveying the totality of his life, he can only say, in effect, “Meaningless, meaningless, everything is meaningless.”

Kohelet’s failure to find meaning is directly related to his obsession with the “I” and the “Me”: “I built for myself. I gathered for myself. I acquired for myself.” The more he pursues his desires, the emptier his life becomes. There is no more powerful critique of the consumer society, whose idol is the self, whose icon is the “selfie” and whose moral code is “Whatever works for you.” This is the society that achieved unprecedented affluence, giving people more choices than they have ever known, and yet at same time saw an unprec edented rise in alcohol and drug abuse, eating disorders, stress-related syndromes, depression, attempted suicide and actual suicide. A society of tourists, not pilgrims, is not one

that will yield the sense of a life worth living. Of all things people have chosen to worship, the self is the least fulfilling. A culture of narcissism quickly gives way to loneliness and despair.

Kohelet was also, of course, a cosmopolitan: a man at home everywhere and therefore nowhere. This is the man who had seven hundred wives and three hundred concubines but in the end could only say, “More bitter than death is the woman.” It should be clear to anyone who reads this in the context of the life of King Solomon, the author of the book, that Kohelet is not really talking about women but about himself.

In the end Kohelet finds meaning in simple things. “Sweet is the sleep of a laboring man.” “Enjoy life with the woman you love.” “Eat, drink and enjoy the sun.” That, ultimately, is the meaning of Sukkot as a whole. It is a festival of simple things. It is, Jewishly, the time we come closer to nature than any other, sitting in a hut with only leaves for a roof, and taking in our hands the unprocessed fruits and foliage of the palm branch, the citron, twigs of myrtle and leaves of willow. It is a time when we briefly liberate ourselves from the sophis ticated pleasures of the city and the processed artifacts of a

18 |

technological age, where we take time to recapture some of the innocence we had when we were young, when the world still had the radiance of wonder.

The power of Sukkot is that it takes us back to the most ele mental roots of our being. You don’t need to live in a palace to be surrounded by Clouds of Glory. You don’t need to be gloriously wealthy to buy yourself the same leaves and fruit that a billionaire uses in worshiping G-d. Living in the sukkah and inviting guests to your meal, you discover that the people who have come to visit you are none other than Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and their wives (such is the premise of ush pizin, the mystical guests). What makes a hut more beautiful than a home is that when it comes to Sukkot there is no difference between the richest of the rich and the poorest of the poor. We are all strangers on earth, temporary residents in G-d’s almost eternal universe. And whether or not we are capable of pleasure, whether or not we have found happiness, nonetheless we can all feel joy.

Sukkot is the time we ask the most profound question of what makes a life worth living. Having prayed on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur to be written in the Book of Life, Kohelet forces us to remember how brief life actually is, and how vulnerable. “Teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom.” What matters is not how long we live, but how intensely we feel that life is a gift we repay by giving to others. Joy, the overwhelming theme of the festival, is what we feel when we know that it is a privilege simply to be alive, inhaling the intoxicating beauty of this moment amidst the profusion of nature, the teeming diversity of life and the sense of communion with those many others who share our history and our hope.

Most majestically of all, Sukkot is the festival of insecurity. It is the candid acknowledgement that there is no life without risk, yet we can face the future without fear when we know we are not alone. G-d is with us, in the rain that brings bless ings to the earth, in the love that brought the universe and us into being, and in the resilience of spirit that allowed a small and vulnerable people to outlive the greatest empires the world has ever known. Sukkot reminds us that G-d’s glory was present in the small, portable Tabernacle Moses and the Israelites built in the desert even more emphatically than in Solomon’s Temple with all its grandeur. A Temple can be destroyed. But a sukkah, even if broken, can be rebuilt

tomorrow. Security is not something we can achieve physi cally but it is something we can acquire mentally, psycholog ically, spiritually. All it needs is the courage and willingness to sit under the shadow of G-d’s sheltering wings.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt"l was an international religious leader, philosopher, award-winning author, and respected moral voice. Following his untimely passing, The Rabbi Sacks Legacy was established to perpetuate the timeless and universal wisdom of Rabbi Sacks as a teacher of Torah, a moral voice, and a leader of leaders. www.rabbisacks.org

(PHOTO: BLAKE EZRA / THE RABBI SACKS LEGACY)

(PHOTO: BLAKE EZRA / THE RABBI SACKS LEGACY)

| 19

Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon

The Shemitta Etrog, After the Shemitta Year

Although the Shemitta year has ended, many of its laws continue to apply, even after the Shemitta year is over. As we approach Sukkot, it is critical to determine the status of etrogim that began growing during the Shemitta year.

The Shemitta sanctity of vegetables is determined by the date of harvest. This is why, from the very beginning of the Shemitta year, one must be careful when purchasing vegetables, because if they were picked after Rosh Hashanah, they have Shemitta sanctity. Regarding fruit, on the other hand, the critical date is that of chanata – when the fruit first begins to assume shape, or when it reaches a third of its growth. Therefore, the fruit that is brought to the market at the beginning of the Shemitta year does not have Shemitta sanctity, and it is only towards Pesach of the Shemitta year that fruit with Shemitta sanctity becomes available.

According to most Rishonim, the etrog used on the Sukkot celebrated at the beginning of the Shemitta year does not have Shemitta sanctity. However, according to the Rambam, it does have Shemitta sanctity. In practice, despite the fact that strictly speak ing we rule an etrog is treated like a fruit, we try to be strin gent and assign it Shemitta sanctity according to the date of its harvest, as if it were a vegetable (see Chazon Ish, Shevi’it 7:10; Shevet ha-Levi, I, no. 175).

A member of the Mizrachi Speakers Bureau mizrachi.org/ speakers

What is the status of an etrog? At first glance, it seems clear that an etrog is the fruit of a tree, and therefore Shem itta sanctity should apply to it only in the eighth year (because any etrog that is available for Sukkot of the seventh year had reached chanata during the sixth year). This is the position of the Ra’avad (Hilchot Ma’aser Sheni 1:5) and most Rishonim, based on the Mishnah in Bikkurim (2:6). The Rambam, how ever, rules that an etrog is treated like a vegetable, because an etrog needs extensive watering just like a vegetable (as indicated by the Gemara in Kiddu shin 3a), and therefore the critical date regarding Shemitta sanctity is the date on which the etrog is picked.

Strictly speaking, it is per mitted to use a Shemitta etrog to fulfill the mitzvah of the four species, only that the sale of such an etrog raises certain problems and must be done through the Otzar Beit Din. This Sukkot, during the eighth year, etrogim do have Shemitta sanctity, and therefore must be sold through the Otzar Beit Din

After Sukkot, the etrog should not be thrown in the garbage, but rather it should be eaten, or else placed in a bag and later discarded in a respectful manner.

When an etrog is purchased with kashrut certification, the certification presumably related to the Shemitta sanctity as well.

Rabbi Yosef Zvi Rimon is Head of Mizrachi’s Educational Advisory Board and Rabbinic Council. He serves as the Rabbi of the Gush Etzion Regional Council, Rosh Yeshiva of the Jerusalem College of Technology and is the Founder and Chairman of Sulamot.

20 |

A Time to Reap: The Arba’a Minim and Chag HaAsif

"A

nd you shall take for yourselves… the fruit of goodly trees, branches of palm-trees, and boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook” (Vayikra 23:40). The most familiar explanation for this mitzvah is that each of the four species represents a certain type of person, and so we bind these four species together to symbolize the necessity of all of them for the wholeness of the people of Israel:

“Pri etz hadar – this is Israel; just as the etrog has a good taste and scent, so too among Israel are found people who possess both Torah and good deeds. Kapot temarim – this is Israel; just as a date tree has a good taste but no scent, so too among Israel are found people who possess Torah but not good deeds. V’anaf etz avot – this is Israel; just as the hadas has a good scent but no taste, so too among Israel are found people who possess good deeds but not Torah. V’arvei nachal – this is Israel. Just as the aravah has neither a good taste nor a good scent, so too among Israel are found people who possess neither Torah nor good deeds. Said the Holy One, blessed be He: To destroy them is impossible; rather, bind them together as one and they will atone for one another” (Midrash HaGadol, Vayikra 23:40).

Along with the beautiful midrashim, it is worth paying attention to the simple layer of the mitzvah, which is

also of great significance to our lives. Chag HaSukkot is also Chag HaAsif, the festival of the harvest, and the mitzvah of the four species is clearly related to the agricultural aspect of Sukkot: “When you have gathered in the yield of your land, you shall observe the festival of Hashem… And you shall take for yourselves on the first day the fruit of goodly trees, branches of palm-trees, and boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook and you shall rejoice before Hashem your G-d seven days” (Vayikra 23:39–40).

There are several aspects of Chag HaAsif , which are reflected in the taking of the four species.

Calm at the end of the agricultural year and the Days of Judgment:

Rabbi Yosef Bechor Shor sees the four species as “bouquets of flowers” that decorate our lives and make them more pleasing. Dealing with the four species is a sign of luxury, an activity that only a person free from the stresses of making a living can afford himself. Until Sukkot, everyone was preoccupied with agricultural work and the fear of judgment of the High Holidays. At the end of this season, a person begins to feel physical and spiritual calm and contentment, a feeling expressed through the four species:

“So that you will be seen as emerging meritorious from the courthouse, so that you will be seen as princes carrying beautiful and scented fruit in your hand, strolling joyously with branches for seven days... On Pesach

and Shavuot you are busy gathering grain. But now you are free…” (Rabbi Yosef Bechor Shor, Vayikra 23:40).

Joy in this year’s produce:

At the time of harvest, man recognizes that the grain grown that year is from G-d, and he rejoices and thanks G-d for it. Taking several kinds of plants that represent the crop, and rejoicing in them before G-d, is the proper way to thank G-d for the crop. The etrog represents fruit, the lulav represents fruit trees, hadassim represent fragrant plants, and aravot represent non-fruit bearing trees.

Prayer for rain and produce:

Alongside joy and gratitude for last year's crop, we also look forward to next year, and pray it will be blessed. On Sukkot we bring the water libation and begin to pray for rain, which allows for growth and existence. Rabbeinu Bechayei sees the four species as part of the prayer for rain:

“These four species grow through water and require more watering than other fruit. Therefore, we are commanded on Sukkot, the time of the water libation and the day of judgment for the upcoming year’s rain, to please G-d with the four species which represent water…” (Rabbeinu Bechayei, Vayikra 23:40).

These three aspects of the four species explain, together, one unified process. We pause to reflect on the year just completed, we express thanks for the abundance we have received, and from this we recognize that we must, once again, pray to G-d for abundance and blessing in the year ahead.

Rabbanit Sharon Rimon teaches Tanach and is Content Editor for the HaTanakh website.

Rabbanit Sharon Rimon

Rabbanit Sharon Rimon

| 21

Son of Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin (the Netziv), Rabbi Meir Bar-Ilan (1880–1949) was one of the Mizrachi movement’s greatest and most passionate advocates. Living in Berlin in 1911, he founded HaIvri, the world’s first Hebrew weekly newspaper. It soon became a primary forum for leading Zionists to grap ple with the great questions of the day.

In 1915, as World War I engulfed Europe, Rabbi BarIlan moved to the United States, where he lived for the next ten years. He soon became the recognized head of the Mizrachi movement and established an American counterpart to his HaIvri paper, which was published weekly until 1921. The following essay was published in Hebrew on the front page of HaIvri on October 11, 1916, and is translated here for the first time.

“Every citizen of Israel shall dwell in Sukkot” (Vayikra 23:42).

rom our study of mussar we know that it is not enough to help one’s friend when he is in pain and to give him support and strength. Rather, we are obligated to join our friend in his suf fering, to see ourselves as if we too are suffering in the same way. We must truly feel his pain.

This obligation is not restricted to individuals, but applies to nations as well. Nations that dwell securely and peacefully in its own land are obligated to feel the suffering of those poor and unfortunate peoples

22 |

who dwell in exile. Settled nations must see themselves as if they, too, are suffering in exile.

When our people were םיִחָרְזֶא, citizens, settled securely in our own Land of Israel, we were commanded to leave our permanent homes for a few days to live in sukkot, in tem porary tents, so that we ourselves could could experience a taste of wandering and exile. We would remember that we were not always established citizens in Israel, but that we too had dwelled in sukkot when we left Egypt. Living in sukkot helped us identify with other nations who had been exiled and could not live in their own land, people who only knew a life of sukkot.

Temporary and impermanent – this is the tragedy of every wandering nation. A nation that dwells in its own land lives a life of permanence and order. If there is value to its actions, the value is lasting and does not change from day to day. And if there is holiness in its way of life, its holiness has permanence. But this is not the fate of wandering peoples, whose lives are not in healthy order. Its people dwell in one land for a period of time and become accustomed to its ways, but are forced to move on to another land, and adopt their ways instead.

This is the history of wandering. There is no nation in world history that walked in exile, whether willingly or against its will, that was not diminished in reputation and numbers. By definition, exile weakens a people, for their children inevita bly assimilate into the host nation’s population. And if there are groups of people who are permanent wanderers, such as the gypsies, they do not even qualify as proper nations possessing their own unique culture and literature.

Only Am Yisrael, despite wandering for years in the desert, merited to be covered by the clouds of glory. Only Am Yisrael, despite our wandering, raised children who retained our identity and stepped into the shoes of their fathers who died before their time. And not only that, but there, in our exile in the wilderness, our national identity was formed and we received G-d’s Torah! But even as we lived in temporary sukkot, we hoped for future days when we would cease to be wanderers and dwell in our own Land.

Just as this hope for our own Land protected the generation of the wilderness, who despite their wanderings did not lose their identity and preferred to wander in the wilderness than to return to slavery in Egypt, so have we had many genera tions since then of “temporary dwelling”, during which the spirit of Israel remained strong and our independent identity did not waver. Even as we wandered, the “clouds of glory” did not leave us, and our children remained with us, accepting the heritage of their father and preserving their unique qualities and achievements. From the exiles of Babylonia, Spain, France and Germany through the exiles of Poland and Lithuania in recent times, we were wanderers, but we did not dwell in a “foreign environment”. We built walls of the spirit around us, and within these walls we lived in a world of our own. We had great centers, of the Geonim in Babylonia, of the wise men of Israel in Spain, and the Gedolei Torah in other lands. And all this time we kept one hope within our hearts: that soon, in just a few more years, our nation would return to life in its own land.

When we dwelt as citizens in our own land, we would test our strength, to see if we possessed the endurance to live a life of wandering. We practiced a life of wandering during the holiday of Sukkot, to see what impact it would have on us and whether we would be able to survive if our land was taken from us.

This “practice” served us well. For when we lived in exile, our temporary homes were spiritually healthy, with an atmosphere of permanence. We kept apart from nations among whom we lived, creating spiritual kingdoms within the physical kingdoms of others. We fulfilled the dictum of ורודָת

ובְׁשֵת, “dwell in [sukkot] as you dwell [in your homes]” (Sukkot 28b), not only during Sukkot, but all year long. Tor rential rains of decrees and suffering poured down upon us, and if the sun occasionally shone with promises of kindness, we still refused to leave our temporary sukkot for permanent buildings that were not our own!... We recognized that we can never live in permanent dwellings in lands not our own. And if our host nations came and destroyed our sukkot and sought to erase the memories of our past and our hopes for the future from our hearts, we would leave that place and build our sukkot anew in a different land.

Only in recent generations have we sought to truly dwell among foreign nations. The wandering has become too much for us; we yearn for a permanent home, and seek it in the homes of others… We have ventured outside of our walls, destroying the mechitza that separated us from our neighbors. If we still have temporary sukkot in our time, they are no longer kosher sukkot, for they are not built from the materials of our own Land and they are also tainted with materials that are הָאְמוט לֵבַקְמ, susceptible to impurity. How beautiful were our sukkot when they stood in our own Land, and we dwelled in them with pleasure and joy! How beloved were our sukkot when they stood within our borders and aroused thoughts of building David’s fallen sukkah [the Beit HaMikdash]! But how different are the sukkot that possess no joy in the present nor hope for the future but serve only as a place of refuge from the stones thrown at us… But today, [as the world is convulsed in war,] we see sukkot that give us some hope. It is possible that through the many “sukkot” in which millions of soldiers now find themselves, in the trenches and battlefields [of World War I] – perhaps through this experience the citizens of the world will begin to understand the suffering of the stranger and wanderer. Perhaps now, when so many millions are forced to leave their comfortable homes for the temporary dwellings of war to fight for the freedom of their nations – perhaps now they will have some sympathy for our people, for our yearning for freedom and for our homeland…

Only one year after this essay was published, on November 2, 1917, Rabbi Meir Bar-Ilan’s hope for compassion from the nations mate rialized with the issuance of Great Britain’s Balfour Declaration, expressing the British government’s support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

ןיֵעְכ

| 23

Katharina Hadassah Wendl

The Simple Letters in a Scroll

The weekly Torah readings are surrounded by many halachot and minhagim. The scroll we read from is stored, usually with a few others, in the Torah ark that forms the focal point of a synagogue. Often made of delicate wood and covered with an embroidered parochet , the ark is in this way like a Torah scroll. In batei knesset following Ashkenazi minhagim, a scroll is covered with a highly decorative mantle. In Sefardi ones, it is housed in a metal cast with detailed etchings. We stand up when the Torah scroll is taken out and car ried through the synagogue, we recite

verses and individuals are called up to read from it – especially on the occasion of upcoming lifecycle events like weddings. Wound up between two atzei chaim, it is presented to the con gregation. The Torah is read, we listen.

Though the Torah scroll is a central part of the regular synagogue services, the heritage and holiness that such a scroll emanates when carried through the synagogue and we read from it are unique. Outside the Jewish communal context, scrolls as a type of written document have become exceedingly rare. This is due to the advent of the

codex in late antiquity and the intro duction of printing in the late middle ages. But as Jews, we still read from them. The text of our scrolls is written nicely and clearly, dark ink on light parchment. But aside from the ark, the rituals, songs and readings, there is nothing more to the scroll than this: black ink on white background, row after row.

Why are Torah scrolls written and kept this way – and have been ever since? Illuminated Hebrew manu scripts and beautiful printed editions

– halachic , midrashic , mystical and liturgical works – have proliferated over the centuries, impressing their readers with ever diverse aesthetics. The illuminated Kennicott Bible and the Barcelona Haggadah are just two examples of these kinds of artfully cre ated manuscripts.1 Torah scrolls do not have such kinds of illuminations – far from it.

Eruvin 13a of the Talmud Bavli records a conversation between Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Yishmael. Asked by Rabbi Yishmael about his profession, Rabbi Meir says that he is a scribe, upon which Rabbi Yishmael responds: “My son, be careful in your vocation, as your vocation is heavenly service, if you omit a single letter or add a single letter, you will end up destroying the whole world in its entirety.”2 Here, writing a Torah scroll is attributed great responsibility – it is guided by clearly proscribed laws – no letter may be added, only certain writing uten sils, only some types of parchments may be used. Also the ink has to fulfil criteria (see Rambam’s Hilchot Tefil lin, 1.4; Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh De’ah 271). One criterion is that it is black

24 |

ink. The Midrash Tanchuma-Yelam denu (Bereshit 1) that Rashi refers to in his commentary on Devarim 33:2 describes that the law was written in black fire upon white fire – black ink on white parchment. Other colours are outrightly forbidden. That a Torah scroll is to be written with dyo – a cer tain type of black ink with the exclu sion of other colours – is considered halachah leMoshe miSinai (Masechet Sofrim, chapter 1).

There is, however, an interesting ques tion about whether gilding letters that have already been written in black ink is permissible. According to the Talmud Bavli, Masechet Shabbat 103b, names of G-d must not be written in gold – this gives a leeway for scribes: Could that mean that gold can be used for other letters? The poskim rule this out for G-d’s name – this makes a Torah scroll invalid. Additionally, it is forbidden to remove the gold as this would be considered blotting out Hashem’s name. Gold dust that has fallen on other letters in a Torah scroll is a different question, though. In theory, as the Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chayim 32:3) writes, adding gold dust onto letters other than those belong ing to G-d’s names does not make it invalid, but fixable. As long as the ink underneath remains intact, the Torah scroll can still be used – but only once the gold dust is removed again! The Keset HaSofer points out that this

Perhaps the simplicity of a Torah scroll is an expression of the will to maintain an authentic connection to the experience of Har Sinai that transcends time and ephemeral artistic trends.

case is fairly uncommon, but knowing about this halachah may enable scribes to save Torah scrolls that otherwise would be considered entirely unfit. Thus, the Torah scroll remains black ink on light parchment.