Transforming Pre-K in Mississippi: The Story of the Early Learning Collaborative Act

Written and Published by Mississippi First

About Mississippi First

Mississippi First is a non-partisan, nonprofit education policy and advocacy organization whose mission is to champion transformative policy solutions ensuring educational excellence for every child. We are a leading voice for high-quality early education, highquality public charter schools, and access to effective teachers and leaders.

Acknowledgments

This commemorative publication was made possible by the generous support of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. We especially thank Bellwether Education Partners, Inc. and Micayla Tatum who conducted interviews and gathered contemporaneous news accounts and other primary sources in summer 2022.

Team

Rachel Canter | Executive Director • Author and Editor

Micayla Tatum | Director of Early Childhood Policy • Project Manager and Co-Editor

MacKenzie Hines | Designer

Rory Doyle | Photographer (unless noted otherwise)

Sonja Semion | Proofreader

Copyright © 2023 by Mississippi First.

All

reproduced

form

rights reserved. No part of this book may be

in any

without written permission from the publisher.

THIS CASE STUDY DOCUMENTS THE EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE ACT’S HISTORY, THE ROLE OF THE LEGISLATION’S CHAMPIONS, AND THE IMPACT THE ACT HAS MADE TO DATE ON THE LIVES OF CHILDREN AND FAMILIES.

Transforming Pre-K in Mississippi: The Story of the Early Learning Collaborative Act

Contents

02

Telling the Story

Meet the players who tell the story and learn about their role in early education and the passage of the Early Learning Collaborative Act of 2013.

04 The Landscape Before 2013

Mississippi’s fractured early education landscape was a primary reason it was one of the only states without statefunded pre-K.

09 A Moment of Possibility

Shifting political winds, the emergence of pre-K champions in the legislature, and Mississippi First’s winning concept for a pre-K program set the stage for a future pre-K bill.

11 Stars Aligning

New legislative leadership, an appetite for big education ideas, and an interest in a comprehensive education agenda created perfect timing for pushing a pre-K bill in 2013.

13 Building a Coalition

Mississippi First and legislative champions built a diverse coalition to support the bill by authentically engaging stakeholders and leaders in the early education space.

14 Solving the Problems of the Past

Mississippi First’s idea to create a collaborative delivery pre-K program enabled all providers to see themselves as beneficiaries of the legislation and prevented the division that killed previous efforts.

16

Getting the Politics Right

The bill successfully navigated challenging political waters that required it to win over the early education community and maintain Democratic support while also appealing to the Republican-controlled legislature.

18

Empowering Trusted Messengers

Instead of only promoting itself, Mississippi First worked to lift the voices of allies trusted by different factions within the legislature to earn support for the bill.

19 Keeping the Coalition Intact

Mississippi First and pre-K champions continuously engaged—and compromised with—early education stakeholders who opposed some aspects of the bill.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K

21 Trustworthy Data and an Independent Voice

Mississippi First’s independence from other organizations and state government, as well as its ability to provide trustworthy data, built credibility for the legislation.

22 Flying Under the Radar

The pre-K bill benefited from being part of a larger education reform package to overcome obstacles on the way to passage.

23 An Overwhelming Majority

After a long, hard road and a last-minute roadblock, the Early Learning Collaborative Act passed both chambers of the legislature with approximately 80% of the vote.

25 Implementation and Signs of Progress

In the time since passage, the program has begun to produce incredible outcomes for children as a result of quality implementation and ongoing support from pre-K champions.

27 Subsequent Legislation and Funding

Due to the success and popularity of the program, the Mississippi legislature continues to increase its investment and has agreed to improvements to the legislation recommended by Mississippi First and the Mississippi Department of Education.

29 Growing the Impact

Mississippi must continue to improve and expand the program to ensure excellence for all four-year-olds in Mississippi.

32 Conclusion 34 Endnotes and Citations

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K

This case study is dedicated to all the students, families, and teachers who have participated in an early learning collaborative since 2013.

Thank you!

The Story of the Early Learning Collaborative Act

On April 2, 2013, the Mississippi legislature passed the Early Learning Collaborative Act,1 which established Mississippi’s first state-funded pre-K program. Ten years after its enactment, the pre-K law is a popular program with broad bipartisan support, but designing the program and securing its passage was anything but easy. “I think back on just how unlikely it was,” said now-Mayor of Hattiesburg Toby Barker, a former state representative and pre-K bill co-sponsor. “It was a minor miracle that we could get not only the support of the education chairman,

but the committee and the rank-and-file members, both on the Republican side who doubted very much we should be in pre-K but also on the Democratic side who had to believe that we were for real and wanted to do something positive.”

How did the Early Learning Collaborative Act evolve from an impossible idea to a celebrated achievement? And what more must we do to protect and expand on our progress in creating a high-quality pre-K seat for

every child who wants one? For the tenth anniversary of the act’s passage, Mississippi First set out to document the Early Learning Collaborative Act’s history, the role of the legislation’s champions, and the impact the act has made to date on the lives of children and families. This report also makes the case for where the state should go from here to ensure the law continues to make a difference for decades to come.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 1

TWO PRE-K STUDENTS READ TOGETHER AT WEST AMORY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL, A SITE IN THE MONROE EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

Telling the Story

Mississippi First worked with a partner to interview legislators and advocates from the early childhood space as well as sift through contemporaneous news articles, videos, reports, state and national research, and other relevant information. Below is the list of interviewees and their brief biographies; other sources are compiled in the endnotes and citations.

Former Representative Toby Barker, R-Hattiesburg (now Mayor of Hattiesburg), who was elected in 2008, cosponsored the pre-K bill and led its passage in the House.

Rachel Canter has been the executive director of Mississippi First since its founding in 2008. She is the author of key Mississippi First reports documenting the need for pre-K in Mississippi, was the original drafter of the Early Learning Collaborative Act, and led the coalition advocating its passage.

Nita Norphlet-Thompson

has served as the executive director of the Mississippi Head Start Association since 2003. She has more than four decades of mental health, early childhood, and leadership development experience. She worked closely with the drafters of the Early Learning Collaborative Act and is a longterm member of the State Early Childhood Education Advisory Council (SECAC).

Former Senate Education Chair Gray Tollison, R-Oxford (now Mississippi Circuit Court Judge), was appointed Senate Education Chair after the 2011 election and encouraged Senator Wiggins to pursue the pre-K bill. Tollison also promoted other education reform bills during his time as Senate Education Chair.

Senator Brice Wiggins, R-Pascagoula, was newly elected to the Mississippi legislature in 2011 and made early childhood issues one of his first priorities. Senator Wiggins became the pre-K bill’s co-sponsor and led the bill’s passage in the Senate.

Jennifer Calvert, a 31-year veteran of early childhood work, is the owner and operator of Calvert’s ABC Preschool and Nursery, which is the lead partner for the Monroe Early Learning Collaborative. She participated in advocacy for the pre-K bill in 2013.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 2

Jackie Mader/Hechinger Report 2014

Rhea Williams-Bishop, Ph.D., was the executive director of the Mississippi Center for Education Innovation in 2013. She had formerly served as the administrator of an early childhood collaboration program called Supporting Partnerships to Assure Ready Kids (SPARK), a W.K. Kellogg-funded initiative implemented by the Southern Regional Office of the Children’s Defense Fund, and facilitated a cross-sector dialogue effort for early childhood practitioners, advocates, and policymakers known as the Mississippi Learning Lab. Bishop is currently the director of New Orleans and Mississippi programming for the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Sanford Johnson was Mississippi

First’s founding deputy director. He is currently the executive director of Teach Plus Mississippi.

Angela Bass, Ph.D., served as Mississippi First’s deputy director of policy after the passage of the Early Learning Collaborative Act and focused on the act’s implementation. After leaving Mississippi

First, Bass founded the Mississippi Early Learning Alliance and served as its executive director. Bass is currently the Mississippi regional executive director at RePublic Schools.

Cathy Grace, Ed.D., was serving as the program director for the Gilmore Early Learning Initiative in 2013. The Gilmore Early Learning Initiative became one of the first state-funded pre-K programs. Grace is currently the co-director of the Graduate Center for the Study of Early Learning and the early childhood education specialist with the North Mississippi Education Consortium.

Jill Dent, Ph.D., was the director of the Division of Early Childhood Care and Development within the Mississippi Department of Human Services when the Early Learning Collaborative Act was introduced. She later became the director of the Office of Early Childhood at the Mississippi Department of Education (MDE), a position she has held since 2015. Her office has primary responsibility for implementing the act.

Holly Spivey became the Head

Start collaboration director during Governor Barbour’s term in 2009 and served in the role under both Governor Bryant and Governor Tate Reeves. From 2020 to July 2022, she also served as Governor Reeves’ education policy advisor. Since July 2022, she has served as the director of government relations for MDE.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 3

Living Cities, 2023

University of Mississippi, 2023

The Landscape Before 2013

When Rachel Canter moved back to Mississippi in 2008 after two years away for graduate school, she knew that one of the first issues she wanted to work on was pre-K. “It didn’t make sense to me that Mississippi was one of the only states without state-funded pre-K when the research was so clear,” she said. “I wanted to change that.”

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 4

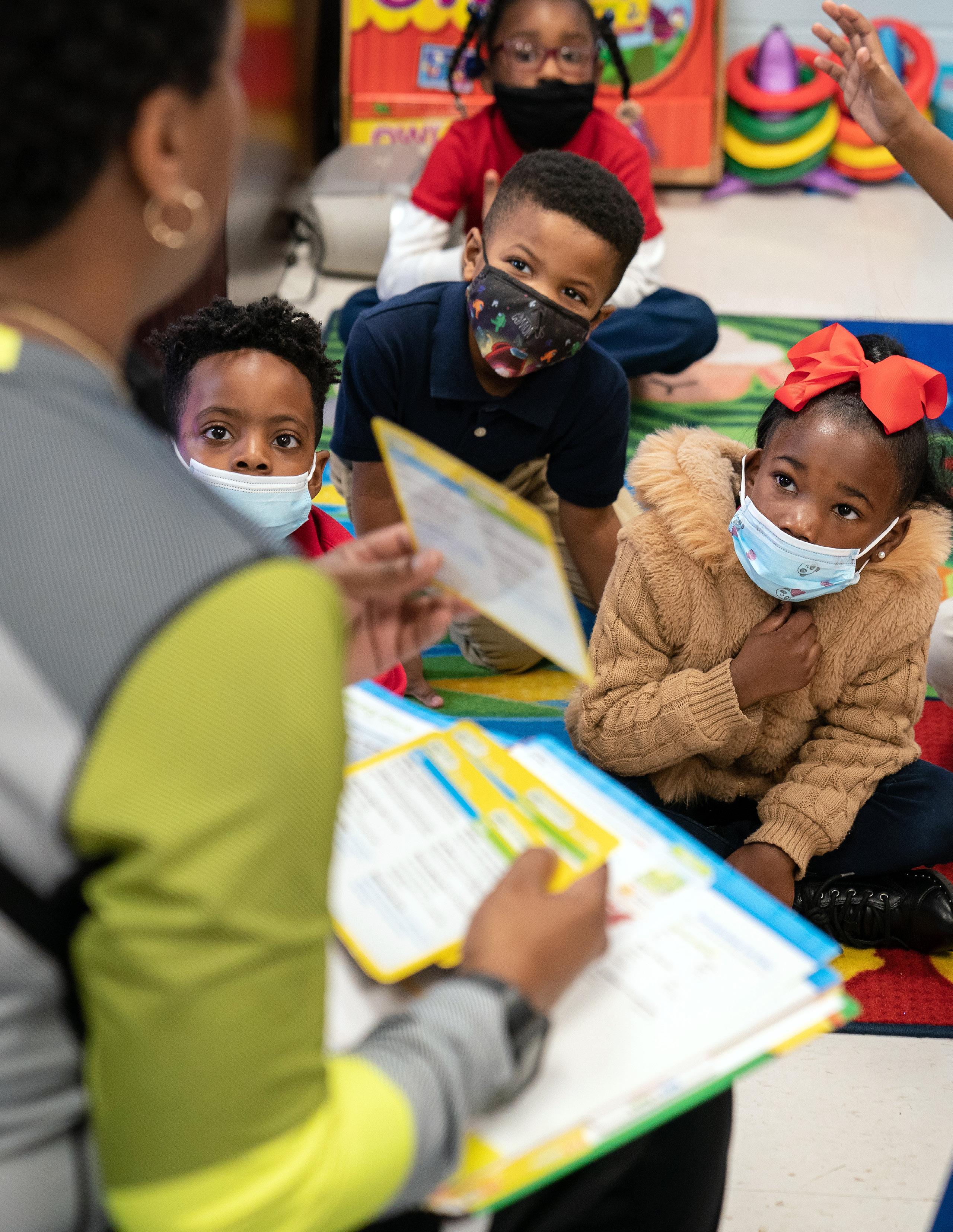

EARLY

TWO PRE-K STUDENTS PRACTICE SOUND RECOGNITION AT A LITERACY CENTER IN A COAHOMA COUNTY

LEARNING COLLABORATIVE CLASSROOM.

Canter, who grew up in Starkville and attended public schools, had directly benefited from the 1982 Education Reform Act that established the state kindergarten program, but since the 1980s, Mississippi had not passed any major early childhood legislation, and kindergarten remained voluntary to attend, a sore point for the early childhood community.* Canter knew Mississippi First would have a hard time achieving its goal of starting a state pre-K program. “I don’t come from a political or wealthy family, and I did not go to college in state, so I had next to no connections, either at the capitol or within the early childhood community. We were starting from scratch on everything,” she said. Knowing she needed to learn more about current conversations and build relationships, she started going to early childhood meetings

and sitting in the back of the room to listen. “I went to all kinds of meetings. Some of these meetings were public meetings, and some of them I got invitations to after meeting key influencers. I also cold-called a lot of people and asked to meet with them. I had the same question for everyone: ‘Why doesn’t Mississippi have statefunded pre-K?’” Those interactions helped her get to know not only the players in the space but what everyone thought the barriers were to bill passage.

In December 2008, Canter attended the launch event for a new childcare initiative supported by powerful state business interests and funded exclusively through philanthropy. The program was a voluntary childcare improvement effort that would provide classroom supplies and curriculum, at least 20 days of coaching, and

business training to participating childcare providers. It was pitched as a lower-cost alternative to state pre-K. A very prominent Mississippi politician gave the closing speech at the event to encourage the audience to support the program. “What he said made a deep impression on me because it summed up what I had heard so many times from so many people by that point,” Canter remembered. “He said, ‘Mississippi will never have a fourteenth grade.’ That was the accepted political wisdom.” But after months of listening, Canter concluded the problem was much bigger. “I thought the issue was more than a perception that Mississippi was ‘too conservative’ to pass a pre-K law. There were multiple, ongoing divisions in the early childhood community that prevented any progress on state pre-K.”

Mississippi, like most states, has many providers with a long history serving four-year-old children. Head Start has served families in Mississippi since 1965, for example. Private childcare has also existed for decades. While the advent of pre-K programs in school districts is a more recent change, by 2009, several school districts were offering some type of program. Not every child was eligible to attend every kind of program, though. For many providers, their source of funding dictates what children they can serve and their total amount is ultimately based on how many of them they enroll. Notably, Head Start has strict eligibility guidelines: 90% of children must be at or below the federal poverty level, with some spaces reserved for children with disabilities. Since childcare is most often supported through tuition,

Major Pre-K Providers in 2013 Head Start

Licensed Childcare

A licensed childcare program provides supervised care to children of any age for which the facility is licensed by the State Department of Health. Examples include childcare programs located in church facilities, private businesses, or private residences. Some Head Start centers must also be licensed, if not affiliated with an educational institution, such as a public school. Licensed childcare programs can also serve older children through summer programs and before and after school care. They are primarily funded through tuition, although some childcare assistance may be available to low-income families through the Department of Human Services (DHS).

Head Start, the state’s oldest publicly funded provider, is federally funded and overseen. The program has strict eligibility guidelines: 90% of children must be at or below the federal poverty level, with some spaces reserved for children with disabilities or other risk factors. Head Start programs may be “blended” with district-based programs that use Title I or other funds.

School District Pre-K

Many school districts in Mississippi provide pre-K using funding from Title I (a federal grant program), local taxes, philanthropy, or tuition. Title I-funded programs are free to families, but children must be “at risk of academic failure” to qualify for services. Districts using funding sources other than Title I usually have more flexibility in enrollment criteria.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 5

*By 2008, an estimated 98% of children statewide attended either public or private kindergarten. The Literacy Based Promotion Act of 2013 made kindergarten compulsory for any child who enrolls, but the compulsory attendance law still begins at age six.

children must come from families who earn enough money to be able to afford care, or they must qualify for the small number of childcare subsidies offered by the Mississippi Department of Human Services (DHS). School districts, too, have restrictions on who they can serve, especially if they fund their program through federal Title I dollars, which must support children at risk of academic failure.

Nita Norphlet-Thompson, the executive director of the Mississippi Head Start Association since 2003, remembers the early childhood world in Mississippi in this time well: “[Before the] Early Learning Collaborative Act—your zip code, poverty level, or resource level— dictated what kinds of services were available to children…

There were patches of work being done but not a really coordinated, carefully aligned effort.” In a resource-constrained state like Mississippi, and with funding tied to enrollment, providers often felt at odds with each other because only a subset of children might be eligible for each of the programs. It made the early childhood space a zero-sum game, even as many children went without access.

All of these providers also have different regulatory authorities and face different standards for health, safety, education, and program quality. Jill Dent, then director of the Division of Early Childhood Care and Development at DHS said, “You could see throughout the state the different levels of quality from different providers or

different levels within the same type of provider.” Representative Barker agreed, “It was a hitor-miss hodgepodge of a lot of well-intentioned people.” Families were left to navigate this confusing landscape without any state guidance about available programs or their quality. Canter found that there was no state data source summarizing the number or type of providers in different communities, let alone the quality of providers. There was not even a common definition of quality. The state also did not have a kindergarten readiness assessment. School districts implemented a wide variety of tests or no test at all, obscuring how children statewide were faring as they entered formal school.

The early childhood system on the state level was characterized by fragmentation as well. Multiple state entities had a hand in policy for children prior to school entry, and though there had been attempts at better aligning systems, state entities have functioned in silos. At the time, the state’s primary government funding for early childhood was federal and came from DHS which receives the Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG) and provides qualifying parents with subsidies for the cost of childcare. However, because of state law, childcare licensure— which ensures childcare centers comply with health and safety regulations before operating—is housed at the Mississippi State

Department of Health, though it is paid for by the Department of Human Services through CCDBG. The Mississippi Department of Education previously had a staff member focused on early childhood, but the agency did not refill the role after that person departed in 2005. By 2008, their only substantive early childhood involvement was as the administrator of federal Title I dollars, the primary source of funding for district pre-K programs. Lastly, as the result of the 2007 federal reauthorization of the Head Start Act, the governor’s office employed a Head Start collaboration director to serve as a liaison between state government and Head Start programs, which did not have a state government link in Mississippi because their funding has never flowed through any state entity.

Government

Mississippi Department of Education

DHS

Mississippi Department of Human Services MSDH

Mississippi State Department of Health

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 6

A TEACHER WORKS WITH A PRE-K STUDENT AT BELL ACADEMY, A SITE IN THE CLEVELAND EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

MDE

Agencies

Outside of government, Mississippi had an entire group of private organizations created to support providers through training, funding, coaching, or coordination. These organizations sometimes provided overlapping services or competed for the same scant resources, and conflicts between leaders had led to more than a little toxicity within the community over the years. As Rhea WilliamsBishop, the former administrator of an early childhood collaboration program called SPARK, noted, “[The early childhood community] was totally disjointed, not connected at all. Everybody was off doing their own thing.” She recalled one attempt to try to foster better working relationships between players nearly turning into an altercation: “We tried to pull together a meeting at the capitol with Head Start leaders, childcare center directors, and anybody interested in early childhood

education…capitol police had to be called because it was that contentious.” Cathy Grace, a 40-year veteran of the early childhood community, added, “I think that the struggles that still take place in some communities are around [these] turf problems.” It made it hard for the sector to speak with one voice about the importance of early childhood education or to articulate a positive vision for the future. The State Early Childhood Advisory Council, another entity resulting from the 2007 Head Start reauthorization, was supposed to increase cooperation among state entities and providers, but meetings often became the forum for any person with grievances to air them through public comment or as part of the formal agenda.

As

Sanford Johnson, Mississippi

First’s founding deputy director, stated, “Of all the different policy issues we worked on, pre-K was the messiest.”

From the perspective of legislators, this messiness was an obvious barrier to any early childhood legislative effort. “It was disjointed to say the least,” said Senator Wiggins. “There was infighting… and nothing would be done [at the capitol].” Canter added, “Every time anybody started to get any sort of momentum behind them, to get something started in the legislature, it would all fall apart, because everybody would attack everybody else, and the legislature just didn’t want to deal with it.”

A good example of this was a series of small pilot programs that the legislature passed in 2007, including a program to create a fund that local communities could use to pilot collaborative early childhood projects. The pilot never received an appropriation—a sign of its weak support at the capitol—and the program never got off the ground.† As Rhea Bishop explained, “If you want to know

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 7

† The law

2010.

sunset by statutory provision in

Since 2012, the legislature has implemented an unofficial rule that it will not pass bills requiring an appropriation if the budget will not include funding for them.

A PRE-K STUDENT READS WITH THEIR TEACHER AT WEST AMORY ELEMENTARY, A SITE IN THE MONROE EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

“[Before the] Early Learning Collaborative Act—your zip code, poverty level, or resource level— dictated what kinds of services were available to children…”

Nita NorphletThompson “

“

how important something is, look at the budget… that spoke volumes to what we thought of early childhood education.”

Everything seemed arrayed against a state-funded pre-K law any time soon, including political context, a fractured early childhood community, and the major push by powerful elites to support the alternative childcare program. “It’s a good thing I’m persistent,” said Canter, “although my family has another word for it—stubborn.” In the summer of 2009, Mississippi First hosted its first intern, Angela Bass, to pull together the research behind why the state should invest in pre-K. At the end of the summer, Canter and Bass organized an event at the capitol to allow Bass to present her findings. “There were some important stakeholders that came at that time,” Bass recalled, “but the general sentiment in the room was, ‘This will never happen; there will never be state-funded pre-K. We just don’t have the money for that.’”

Canter was pleasantly surprised at the number of people who came to that event, considering how new Mississippi First was and how adamant some had been that pre-K was a pipedream. She did not expect the fallout. “Some of the monied elite were extremely angry that we had an event focused on pre-K at the capitol, even if it was only an end-ofinternship presentation. As a result,

I got dragged to a meeting with three people who were a lot more connected and powerful than me or Mississippi First.” Their message to Canter was clear: stop talking about a state pre-K program. With less than a year in operation, Mississippi First still lacked sizable benefactors or a record of success, and there was a danger in making powerful enemies. “I knew the easier path, both in terms of fundraising and politically, would be to go along to get along, but I did not believe that was the right path for kids,” Canter said.

Over time, Canter would return again and again to something that struck her about that meeting— why were these very wellconnected and well-funded people so afraid of a new, under-resourced organization talking about statefunded pre-K? As Mississippi First continued to beat the drum about pre-K, she found her answer. Many, many people were actually very interested in a real pre-K program if someone could solve the issue of how to do it in a way that built a winning coalition. “Most people I talked to did not really support the idea that had become the darling of the monied elite; they wanted something that would expand access and quality statewide, and they wanted financial support for the efforts they were making in local communities that were working. What they wanted was a state pre-K program that they could see themselves in,” Canter

said. But there was “no unified vision about what pre-K should look like, what standards should be, or what kids should get out of the program,” she said. “We had to get advocates to stop standing in a circle and shooting at each other.”

Canter concluded this was the key political and policy problem that she should try to solve—the fact that advocates could not get on the same page about what a statefunded pre-K program should be.

After extensive research, Mississippi First published its first major report in January 2012. Titled Leaving Last in Line in a nod to the fact that Mississippi is often last to do good things in education, the report was the culmination of four years of conversations and observations,

and proposed a collaborative pre-K model‡ based on an amalgamation of policies from other states, fit to the Mississippi context. Canter remembers the reception to Leaving Last in Line among state early childhood leaders being underwhelming. “I was so excited about it, and state early childhood leaders either did not react or they wanted to bicker over the one or two sentences that referenced their specific program. I think there was this ingrained sense of ‘everyone says it can never happen so that means it can never happen.’”

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 8

‡Many people nationally refer to collaborative pre-K models as “mixed delivery,” but Canter believed that the word “collaborative” has more political zing because it is easier to understand and has more positive connotations. “Collaborative” was also the word used in a 2007 law that proposed a pilot program which never got off the ground.

A PRE-K STUDENT WORKS WITH THEIR TEACHER IN THE CLEVELAND EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

A Moment of Possibility

The political winds had begun to shift by the time Mississippi First published Leaving Last in Line in January 2012, although few people yet realized what it might mean for pre-K.

In November 2011, the historically Democratic-controlled House experienced a 20-seat swap, with Republicans winning unified control over the Mississippi legislature for the first time in 150 years. This introduced new leaders, including newly appointed Speaker of the House Philip Gunn and newly appointed Senate Education Chair Gray Tollison, as well as several new legislators, including former assistant district attorney and newly elected Senator Brice

Wiggins. Holly Spivey, who was serving as the state’s Head Start collaboration director at the time, remembers the term that began in 2012 as “a perfect storm of new people coming in” to make a change happen. As Representative Barker explained of the new Republican majority, “There was a desire to do things—to have an agenda, not just to be the party of no.”

Before that election, state legislators had not prioritized

either pre-K or early childhood education more generally. Representative Toby Barker recounted how pre-K was not a legislative priority because leaders were focusing on fully funding K–12 education. Others were skeptical of whether Mississippi would be capable of creating a high-quality early childhood education system even if funds were available, given the state’s K–12 system struggled to ensure every child could read, write, and meet other basic

academic benchmarks. The fact that kindergarten was still not mandatory was another talking point Canter heard a lot. Moreover, there was the problem that Canter had identified early on: no one had proposed a substantive bill that had the support of most of the early childhood community.

Canter went into the session with a singular goal—to find a champion for pre-K who could introduce a bill. “I met with a long-time Democratic champion

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 9

A TEACHER WORKS WITH A PRE-K STUDENT AT WEST AMORY ELEMENTARY, A SITE IN THE MONROE EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

for education in late 2011, and I asked him, ‘How do you get a big bill passed?’” What he said would be life-changing for Mississippi First and the probability of passing a pre-K bill: find a legislative champion. “I realized that I had not spent enough time convincing the actual decision-makers—the legislature,” Canter admitted. After the lukewarm reception to Leaving Last in Line among early education leaders, Canter decided to use the report to build political will directly with legislators instead of trying to convince advocates who were reluctant to promote yet another new idea.

Ideally, Mississippi First would be able to identify a champion in both the House and the Senate, as any bill would have to make it through both chambers to get to the governor’s desk. To Canter, there were three basic qualifications for the role: the legislator had to be passionate about pre-K or willing to learn, they needed to be on the education committee in the House or Senate, and, out of political necessity, they needed to be Republican because of the new Republican majority. Two legislators quickly rose to the top of her list: Senator Brice Wiggins, a freshman legislator from Pascagoula, and Representative Toby Barker, a second-term legislator from Hattiesburg.

Canter remembers the exact moment that she met Senator Wiggins. “Early in the 2012 session,

the Senate Education Committee had a hearing to listen to the Department of Education explain the state’s school funding formula. Senator Wiggins asked a question about whether the formula could fund early childhood education. It was probably the third or fourth time I had heard him ask a question about early childhood. I thought, I have to meet this guy.” After the meeting concluded, Canter chased Wiggins down in the hallway. “I remember I introduced myself and shoved the pre-K report at him. He didn’t tell me to go away; instead, he was excited about it and asked me to come talk to him some more.”

In his campaign for the legislature, Senator Wiggins had identified early education as one of his priorities. During his tenure in the district attorney’s office, he had partnered with groups like Fight Crime, Invest in Kids,§ as he was concerned about the number of young people in prison. “In my former life as a prosecutor, I really got tired of seeing the kids in the courtroom who had not finished school, and I figured there had to be a better way,” said Wiggins. That experience led him to involvement in early Excel By 5 efforts in Jackson County. Excel By 5 is a statewide initiative that promotes collaboration and certifies communities as child friendly. By focusing on early education, Senator Wiggins believed the state could improve outcomes for Mississippians. He thought

his status as an unconventional champion for pre-K and as a new member of the legislature was a strength. “I was new to the game of this area of policy, so I wasn’t jaded, and I wasn’t going to take no for an answer,” he said.

An incumbent by 2012, Representative Barker had met Canter in 2009, his first year in the legislature, and had attended Bass’ presentation at the capitol that summer. “I had known Representative Barker was someone I wanted to work with for a while,” Canter says. “He always carried around these huge binders stuffed with bills, research, notes, and speeches. Pre-K needed someone who would put in the work to learn the issue, and Representative Barker was my first choice in the House.”

Representative Barker also had the advantage of being not only

a member of the new majority party but also one of the few legislators who had previously served on the House Education Committee. He saw new legislative leadership as an opportunity to pursue his interest in early childhood education, which he developed after hearing about the successes of Harlem Children’s Zone and differences in childhood experiences before kindergarten. As with Wiggins, Canter met with Barker in the capitol in late January 2012 and gave him a copy of Leaving Last in Line. He promised to read it.

By the time Canter had these crucial conversations, though, the 2012 session was too far along to introduce a bill. “I knew we weren’t ready to push pre-K in 2012. I was trying to lay a foundation to bring a bill in a future session.”

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 10

A PRE-K STUDENT WORKS ONE-ON-ONE WITH THEIR TEACHER AT WEST AMORY ELEMENTARY, A SITE IN THE MONROE EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

§Fight Crime, Invest in Kids is a national nonprofit that organizes local law enforcement and other professionals in the criminal justice field—such as district attorneys—to talk about the importance of pre-K.

Stars Aligning

It was the first step in Mississippi

First’s research project to document how widespread pre-K attendance had become statewide. Canter recalled with some chagrin, “I thought at the time we were two to three years away from a pre-K bill.” Then, in December, Senator Wiggins called her and asked to meet at the capitol when he was in town for other meetings. When Canter and Sanford Johnson met with Wiggins, he asked for help drafting a bill to put the ideas in Leaving Last in Line into law. Canter was surprised but thrilled. “I immediately said, ‘Let’s ask Toby Barker to introduce the bill in the House.’” Not only had Barker read Canter’s report earlier in the year, but he had approached her as the 2012 session closed with an idea about where they could squeeze some money for it out of the state budget. “There was no doubt in my mind that Representative Barker had to be the bill author in the House if we wanted it to pass.” Wiggins and Mississippi

First left that meeting with a plan—Senator Wiggins would talk to Senate Education Chair Gray Tollison and then-Lieutenant Governor Tate Reeves to get their

support, and Canter would call Representative Barker.

“He agreed right away,” Canter remembered. Barker had been thinking about writing a bill as well, but he quickly got on board with the plan for having identical bills in the House and the Senate to increase the likelihood that one of them would pass. Most importantly, he offered to convince Speaker Philip Gunn to add the issue to the House agenda. “That was critical,” Canter said.

Senator Wiggins met with Chairman Tollison shortly after

his meeting with Mississippi First and recalled Tollison’s enthusiasm, “He was like, ‘Brice, love it, you go, you go do it, and let’s get some investment.’” Together, the two approached Lieutenant Governor Reeves to secure his support.

One of the factors that worked greatly in their favor was that, as 2013 was the second year in the legislative term, expectations were high that the legislature would do big things. “Usually, the second and third years are the times [to do it] if you want to have success with legislation,” said Chairman

Tollison. Barker agreed, “You know, I think you had a year of everybody figuring out where the bathroom was, now that [Republicans] were chairmen and subcommittee chairmen and [there were] a lot of new members. Sometimes you can get things done quickly; sometimes it just takes a while. And it was not a very big majority that Republicans had. So it took a year to kind of get your footing and learn some of what those things were.”

On top of the advantageous time in the term, legislative leadership had

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 11

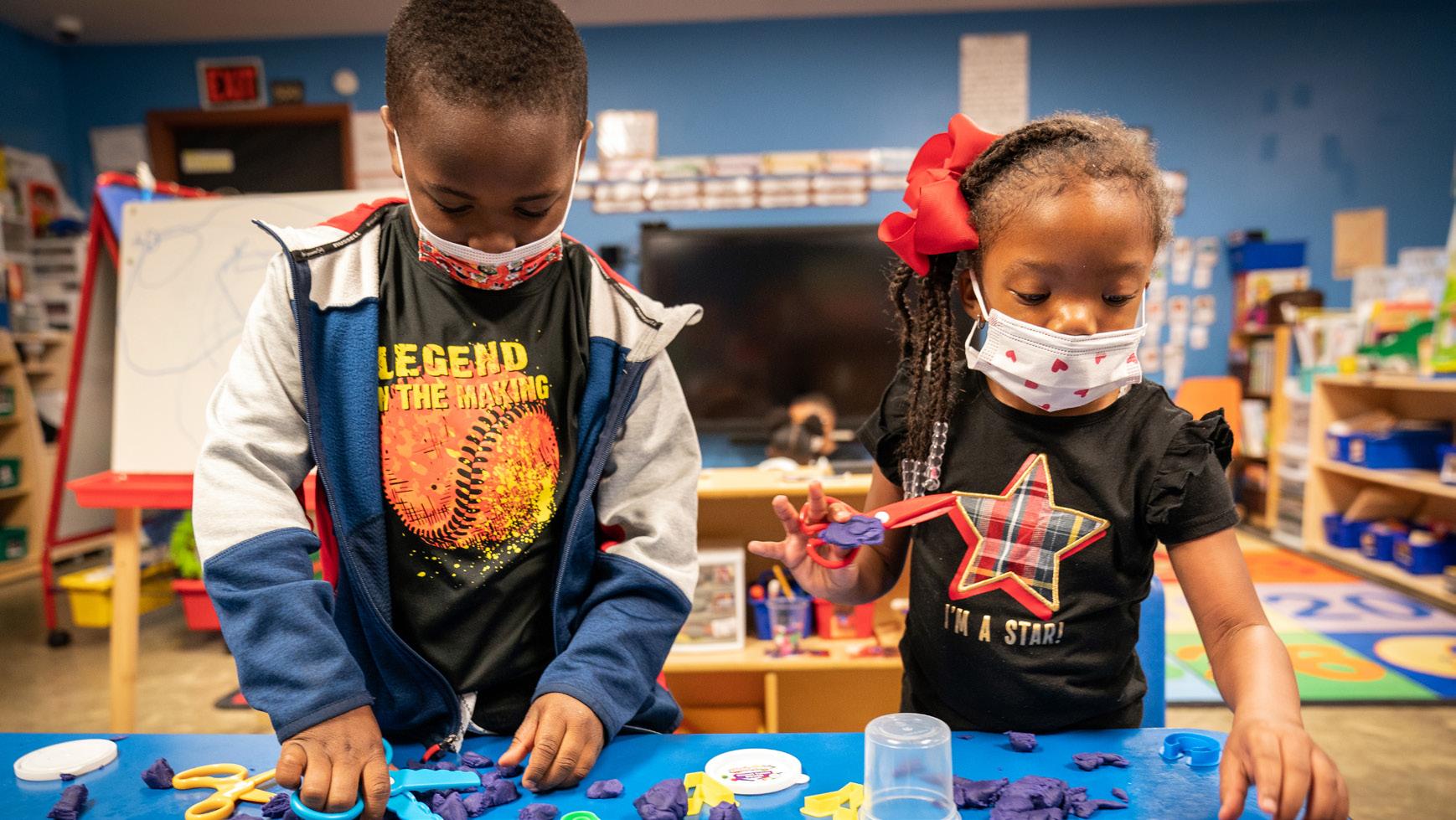

TWO PRE-K STUDENTS MAKE PLAY-DOH SHAPES AT CALVERT’S ABC PRE-SCHOOL, A SITE IN THE MONROE EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

After the 2012 session, Mississippi First went back to work researching pre-K programs statewide and published a second report called the Title I Pre-K Preliminary Report examining the number of school districts with Title I-funded pre-K programs as of the 2011-2012 school year.

started to talk about 2013 being an education session. The focus on education “organically grew,” according to Chairman Tollison. Beginning in 2012, the legislature had taken a renewed interest in big education policy ideas and had narrowly lost passing a new charter law. After the session, Mississippi First and the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, two organizations with different philosophies about policy but a shared interest in improving education, hosted a talk by former Florida Governor Jeb Bush about Florida’s education success. That talk laid the groundwork

for a bill to ensure students read to a minimum level of proficiency by third grade, a signature initiative of Bush’s national policy nonprofit. Leadership also planned a renewed charter school push in 2013.

Tollison remembered, “We were pushing several pieces of legislation—’we’ being the Education Committee, the lieutenant governor, and others… We had something for everybody. If you were all about reform, we had charters and some other things, and we had early education.” A similar dynamic was happening in the

What are “early learning collaboratives” under the Early Learning Collaborative Act?

Early learning collaboratives (ELCs) are community-based partnerships between providers of four-year-old pre-K, including, at a minimum, a school district and a Head Start, if one exists in the county. Childcare providers and private or parochial schools may also join a collaborative. The collaborative program is characterized by a few key features:

Collaboration

Collaboratives must be governed by a council of all participating providers. This council must select a lead partner to coordinate their joint application to the state for funding and serve as the fiscal agent of the collaborative.

Quality

ELCs must meet 10 of the 10 NIEER Quality Benchmarks for statefunded pre-K programs. These include requirements such as teacher and assistant teacher qualifications, curriculum supports, early learning standards, and professional development.

Funding

Collaboratives offer a high-quality, low- or no-cost pre-K option to families in Mississippi. ELC funding is based on enrollment. For every child in a full-day program, an ELC receives $2,500 from the state and must match this amount with its own $2,500, for a total of $5,000 per child. Match dollars can include any source of funds, as allowable, but the most common source of matching funds is Title I dollars. ELCs also use the proceeds of tax credit donations to meet their match.

State Tax Credit

Individuals and corporations who make a contribution to an approved ELC may receive a 1:1 tax credit from the state. The tax credit program has become an important source of funds for the ELCs.

House. Barker recounted to Canter how House leadership felt that they needed a popular education idea to round out their priorities since both the charter school bill and the reading bill were highly controversial. Barker was ready with the solution—pre-K.

As Nita Thompson said, “The timing was perfect.”

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 12

PRE-K STUDENTS WORK IN THEIR CLASSROOM AT PETAL PRIMARY, A SITE IN THE PETAL EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

Building a Coalition

Prior to the session, Mississippi First, Wiggins, and Barker agreed to keep the bill quiet to prevent the naysayers from having too much time to get organized. They knew they would have to build a coalition to get the bill to the governor’s desk, even with the support of the legislative leadership, but they would have to go about it carefully. After all, infighting among early childhood advocates was one of the obstacles to getting anything done in the past and precisely the problem their collaborative pre-K model was intended to solve. When the bill was mostly ready in early January 2013, Canter started to call people in the early childhood sector she trusted and whose buy-in she thought they needed. Two of the first people she reached out to were Holly Spivey and Nita Thompson.

As Spivey recalled, “I think that [Mississippi First] went about it the right way… I can only speak to the Head Start side, but Rachel [Canter] and others reached out and said, ‘I’m going to show you this. I want y’all to tell me what would work and what will not work.’ And that was very different than just being told, ‘This is what we’re going to do.’ And so I think, from the beginning, it was inclusive.” According to Thompson, “Where in the past . . . a group of usual suspects would make all the decisions, [this time] the net [was] cast a little wider, included more people, and [got] more buy-in.” Spivey added, “I think [Rachel Canter] was just very strategic in who she reached out to for help and for advocating for the bill.” As Spivey said, “It’s an ugly process while going through it, [but] that made [the bill] successful and helped our state in a lot of other areas—listening to different voices and [being] inclusive of other opinions and what they think is important.”

“I thought of this process like throwing a pebble in a pond,” said Canter. “If you throw a stone in still water, it starts to make ripples, slowly at first, then wider and wider. By the time I got to the second round of phone calls, beyond the people I knew best, I knew that word would get out about the fact that we were trying to pass a big pre-K bill. That meant the clock started ticking on when we would get our first pushback. I needed to make sure we had solid support from key influencers to withstand what I knew was coming.”

One of the strategies the bill used to gain support was to amend the section of the law containing the unfunded 2007 program,2 as Mississippi First had proposed in Leaving Last in Line. This meant Canter and others could message the bill as building on ideas the community already

supported. Jill Dent noted that the new bill not only “identified a different agency to manage it, but the revisions gave it some more teeth to make it work.” Early childhood leaders involved in the 2007 effort saw the bill as acknowledging and honoring their work.

By the end of January, advocates had enough support to host a press conference at the capitol announcing the legislation. In a rare show of unity, both Speaker Gunn and Lieutenant Governor Reeves made speeches and threw their support behind the bill.3 Representatives of school districts, Head Start, and childcare providers also spoke as did the bill co-sponsors. Two hours later, Governor Phil Bryant, who was supporting legislation to seek state funding for a childcare improvement program,** would release a statement supporting early childhood programs generally. “Everyone else was at the pre-K press conference. I think he felt pressure not to be left behind,” said Canter.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 13

**This program was the same one announced at the 2008 event Canter attended. It completed its pilot in 2012 and was seeking state support to continue.

A PRE-K STUDENT WORKS ON DAYS OF THE WEEK AT ROWAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL, A SITE IN THE HATTIESBURG EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

Solving the Problems of the Past

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 14

PRE-K STUDENTS

WORK IN THEIR CLASSROOM AT OAK GROVE, A SITE IN THE LAMAR COUNTY EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

Although the bill had a long way to go from the time of the press conference until final passage three months later, the bill’s core idea of structured collaboration meant that advocates were able to sidestep most of the divisions of previous efforts. As proposed in Leaving Last in Line, the bill required local communities to create “collaboratives” using specific rules: at a minimum, collaboratives had to include at least one school district and at least one Head Start, if one was available in the county, but could also include childcare as well as private and parochial schools. These collaboratives would then write a joint application to the state for funding. The law specifically required collaboratives to coordinate enrollment across providers so that Head Start enrollment would not decline as a result of the program.

The inclusion of Head Start as a mandatory collaborative partner and the provision to coordinate enrollment solved a major, longstanding problem for Head Start and secured their support. As Nita Thompson explained, “We wanted to be very careful not to use state dollars to supplant federal dollars because all of Head Start’s funding in Mississippi is federal. If we introduced state dollars and Head Start was not able to meet its enrollment, that could jeopardize our funding. And once those dollars are gone, they’re gone. It’s very difficult to get them back. So while we were very in favor of increasing access, and the number

of high-quality early childhood education seats in the state, …we wanted to make sure that it could be coordinated…hence the whole collaboration model.”

For school districts, the bill also helped solve some key challenges. Though about a third of school districts were already spending money to try to provide pre-K, most had limited financial ability to do so, and some struggled with a lack of space, or a lack of age-appropriate space, in their buildings. Collaborative funding would help them stretch their limited dollars to serve more students, but the most attractive element of the bill was that it would improve kindergarten readiness by ensuring uniform quality across all participating early childhood classrooms, whether district operated or not. As Barker recalled, one of the goals of the Early Learning Collaborative Act “was to align things” to help “level the playing field for kids going into kindergarten.”

The childcare community was the most divided in their support. Childcare providers “who had invested a lot in quality and were working with their school districts already were the ones [who were] more [supportive],” stated Rhea Williams-Bishop. Other providers were concerned because, historically, childcare providers in Mississippi were only subject to health and safety regulations, and many did not meet the proposed NIEER quality standards. They were

also concerned about the economic impact on their businesses of state-funded pre-K for four-yearolds. Since allowable child-staff ratios are higher for older children, four-year-olds help subsidize the cost of providing services to infants and toddlers whose classrooms have lower child-staff ratios and thus higher costs. If a childcare center’s four-year-old enrollment decreased, it could raise the cost of care for families and potentially reduce the services available. However, because the collaborative bill was the first program with serious legislative support to propose state dollars that childcare providers could access, enough childcare leaders spoke in favor of the bill to counteract those who were unhappy about the prospect

of state pre-K. Jennifer Calvert, a long-time childcare director whose center would later become the lead partner of Monroe Early Learning Collaborative, had been part of a local collaborative initiative in her community started by the Gilmore Foundation a few years before and had seen the possibilities of this kind of approach. “It had benefited my center because it increased my enrollment as far as my fouryear-old program,” she explained. That experience motivated her to become involved in the bill’s advocacy from a childcare provider’s perspective: “I was part of lobbying for it in Jackson...in support of us trying to get this going to get the funding to be able to serve children.”

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 15

STUDENTS LISTEN AT LONGLEAF ELEMENTARY, A SITE IN THE LAMAR COUNTY EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

PRE-K

Getting the Politics Right

Senator Wiggins explained, “You have to understand politics and the reality of politics. And I will say this is what, in my opinion, has made Mississippi First excellent…because they understand the art of the possible in the legislature.”

Key to the bill’s success legislatively was how it prioritized quality and accountability. The bill incorporated the NIEER quality benchmarks as they existed in 2013, which were politically appealing as quality control measures. “We weren’t just writing a check for $50 million; we were using this legislation to make sure they had good quality instruction and requiring that [through the adoption of the NIEER benchmarks] before we released [funds] to them,” Senator Gray Tollison noted. The inclusion of the NIEER benchmarks would prove vital for the long-term success of the program, both politically and practically.

First, the benchmarks give legislators the ability to refer to Mississippi as a leader in the nation for high-quality pre-K because they are the criteria with which NIEER ranks programs in its popular State of Pre-K Yearbook series. In 2015, for example, Senator Wiggins started a speech to the Mississippi Economic Council by asking the audience, “When in your life did Mississippi lead the nation in education?”4 Jill Dent, who now administers the program at MDE, agreed, “[The benchmarks have] given our champions something to hang their hat on, to say we’re one of five states in the nation who met all 10 benchmarks, which helps them help us.”

The use of national program quality standards also helped prevent problems during implementation. Jill Dent values “the insight at the time to write it toward the NIEER benchmarks, because if they had not done that, we would have always had a fight on our hands to ensure that we were implementing the quality benchmarks that we needed to have.” Senator Wiggins recounted that one early learning collaborative director told him a few years later that “[The Early Learning Collaborative Act] didn’t allow people to create excuses. … When [quality] was written into statute, we could say it is in statute; you can’t get around it.” Monroe Early Learning Collaborative’s Jennifer Calvert echoed Senator Wiggins’ statement about the importance of the NIEER benchmarks on the quality of the program, “If we didn’t have those [NIEER] guidelines, and the structure, it probably would not be effective.”

The benchmarks were only one form of accountability within the Early Learning Collaborative Act. Canter wrote a requirement into the bill that every collaborative would administer the pre-K version of any kindergarten readiness assessment the state implemented in the future. Canter knew that if the Literacy-Based Promotion Act passed, a kindergarten readiness assessment would become mandatory, and she wanted the collaboratives’ assessment system to align. This information would be useful in determining whether the program was improving student outcomes over time and could become part of each collaborative’s accountability, along with the findings of annual site visits, classroom quality measures, and adherence to program standards.

These measures helped to make sure the state was, according to Chairman Tollison, being “smart with the money.”

Being “smart with the money” was important because funding had long been a barrier for state-funded pre-K. As noted earlier, the state has not been able to “fully fund” the K–12 system, so there was hesitancy to have a state-funded pre-K program. “We had a limited amount of money,” Chairman Tollison noted, “and we need[ed] to put it in places where we [would] get the greatest return in terms of teaching a child.”

Because the state could not fund pre-K on its own,5 the bill included a one-to-one matching requirement. The matching not only helped solve the funding problem but also made the bill more attractive to legislators because the community had to play a role. “One of the big selling points of the Early Learning Collaborative Act was the match of local dollars or in-kind donations because [funders had] an investment in the program to see that it succeeds,” Chairman Tollison recalled. Representative Barker agreed, “The legislature likes the community ‘having skin in the game.’” The bill allowed a wide variety of funding sources to count as matching dollars, including in-kind donations—an important option since available resources differ across the state. Senator Wiggins explained, “It was written very broadly that you could do in-kind donations to help match. It didn’t have to be money. It could be someone in the community donating a building because we knew in different areas of the state, they have

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 16

In addition to winning over the early childhood community, the bill had to appeal to the Republican-controlled legislature while maintaining Democratic support.

different things. What’s in Pascagoula is not in Tallahatchie County.”

To legislators, another benefit of the matching requirement—along with the competitive nature of the application—was that it encouraged local communities to plan how they would leverage their resources to support their collaborative before they received any money from the state. “[Collaboratives] were not just given a pot full of money to spend; they had to be approved for the program. They had to put some investment and effort in the front-end in terms of coming up with a plan, instead of just receiving money, then coming up with a plan,” Chairman Tollison said.

To support communities in meeting their local match, the bill created a tax credit donation program. When the legislature passed the Early Learning Collaborative Act, bill sponsors were not sure how valuable the tax credits would be to communities, but Senator Wiggins wanted a way to increase the business community’s involvement in—and ultimately support for— the program. As discussed later in this case study, the inclusion of the tax credit proved to be one of the most important aspects of the bill for collaboratives.

Other parts of the bill sweetened the deal for the new conservative majority. When Wiggins and Barker heard that a major conservative organization would oppose the effort, Canter drafted a statement for the legislators to co-sign and submit to a conservative state political blog.6 The statement highlighted how the bill satisfied several Republican values, in addition to accountability, student outcomes, and costeffectiveness. For example, the very nature of a voluntary, collaborative program gives families maximum choice in deciding where to place their children for pre-K—or deciding to optout—according to what choice best fits their families’ needs. The focus on creating programs locally within some broad parameters meant that local communities had a level of autonomy and flexibility to design a program right for their local context. In a session in which the charter school debate was generating a lot of attention, words like “choice,” “autonomy,” and “flexibility” were heavily favored.

Finally, as Canter proposed in Leaving Last in Line, the Department of Education would oversee the program, rather than the Department of Human Services, which had

responsibility for the defunct 2007 program. The move underscored the educational role of early learning collaboratives since “people perceive education differently than they perceive childcare,” according to Jill Dent, who worked at DHS at the time. This oversight structure also meant the bill was formally recognized as an education bill by being referred to the education committees in both the House and the Senate. This shaped the conversation by focusing the debate on the benefits of pre-K for school readiness. Mississippi First stepped in with data on the decades of gold standard research showing the positive effects of pre-K—when programs are implemented with quality. These data were particularly important as Tollison and Wiggins recalled that opponents cited research on pre-K “fading out” by early elementary grades as a reason not to pass the program.7 Canter felt keeping the focus on the effectiveness of pre-K was stronger political ground than having a culture war conversation about whether “babies should be home with their mamas,” in Canter’s words.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 17

PRE-K STUDENTS WORK IN A SMALL

ON LITERACY SKILLS AT

LEARNING

SITE IN THE HATTIESBURG EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

GROUP

TJ’S

CENTER, A

Empowering Trusted Messengers

Several of the coalition’s points were reiterated by the trusted messengers advocates mustered to win over Republican legislators. Key business leaders spoke about how an investment in pre-K would be good for Mississippi’s economy, both in terms of graduating students ready to enter the workforce as well as attracting and retaining companies. Mississippi law enforcement officials organized by Fight Crime, Invest in Kids as well as military officials tapped by ReadyNation met with legislators to explain how pre-K could impact societal issues such as decreasing criminal involvement and protecting national security

because children who start behind may not be eligible for military service at age 18.8

Senator Wiggins recalled that some thought a state-funded pre-K program would lead to “the government raising [their children],” or concerns that fouryear-olds were too young for formal, organized learning. These concerns were rebuffed, in part, by the religious community. According to Senator Wiggins, “The religious community, preachers, [came] out in support of early education because they saw it as a family values issue.” Mississippi First also addressed these concerns by presenting data showing that the

overwhelming majority of children in the state were already receiving care outside of the home.

On the Democratic side, different messengers were key. Mississippi First directly connected providers to legislators who had questions about how the bill’s provisions would impact them and the families they served. As described by Holly Spivey, Mississippi First would “make sure if a legislator had a question about a certain portion of the bill to connect with the person who is going to be able to answer that question. Then it wasn’t Mississippi First telling me this, it was the individual [the legislator already had a

relationship with] who is going to be able to reassure you.”

This strategy was instrumental in countering misinformation about the bill. At the eleventh hour, rumors circulated that the bill would negatively impact Head Start. In a coordinated response, Mississippi First’s Rachel Canter facilitated phone calls between legislators and Head Start staff to sort out concerns, and the Head Start Association facilitated conversations with Head Start directors and legislators. Having Head Start providers and directors speak for themselves about the bill’s potential impact was invaluable in securing its passage.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 18

A PRE-K STUDENT WORKS WITH THEIR TEACHER AT C.H. JOHNSON HEAD START, A SITE IN THE PETAL EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

Keeping the Coalition Intact

Although some from either the Head Start or the public school communities remained unsure whether the collaborative model would work (one Democratic legislator told Canter he did not understand why the state did not “just give money to school districts”), most of those in opposition came from the childcare space. Bill sponsors and Mississippi First did not try to win over opponents to any state-funded pre-K effort, regardless of its design, although the team did meet with these providers to hear their views. Instead, they focused on understanding those who disagreed with particular provisions to see if mutually agreeable compromises could

be reached. “Brice and I worked really hard to try and iron out agreements,” Barker recalled. Canter would often sit in on these meetings at the request of either Barker or Wiggins to provide further information or rationale, especially as opponents would sometimes bring up policy grievances well outside the scope of the bill.

Most of the childcare community’s disagreements came from just a few lines, rather than the concept of collaboration. Many providers were unhappy with the bill’s original language requiring childcare centers to meet a “3” on the state’s new five-point

childcare quality rating scale to participate in a collaborative. This requirement arose because childcare, unlike school districts or Head Start, did not have to adhere to any quality standards aside from of health and safety regulations, and bill sponsors were concerned the NIEER standards would be difficult for centers to implement if they did not already meet a base level of quality. However, the state’s voluntary rating system was only in use by about onethird of centers statewide, and its design was controversial among both participants and nonparticipants. Sanford Johnson remembered, “There was a big question about how many

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 19

While it was a huge advancement to get most of the early childhood community on board with the bill, bill sponsors and Mississippi First still spent a lot of time talking to—and compromising with—different factions within the community who opposed various aspects of the bill.

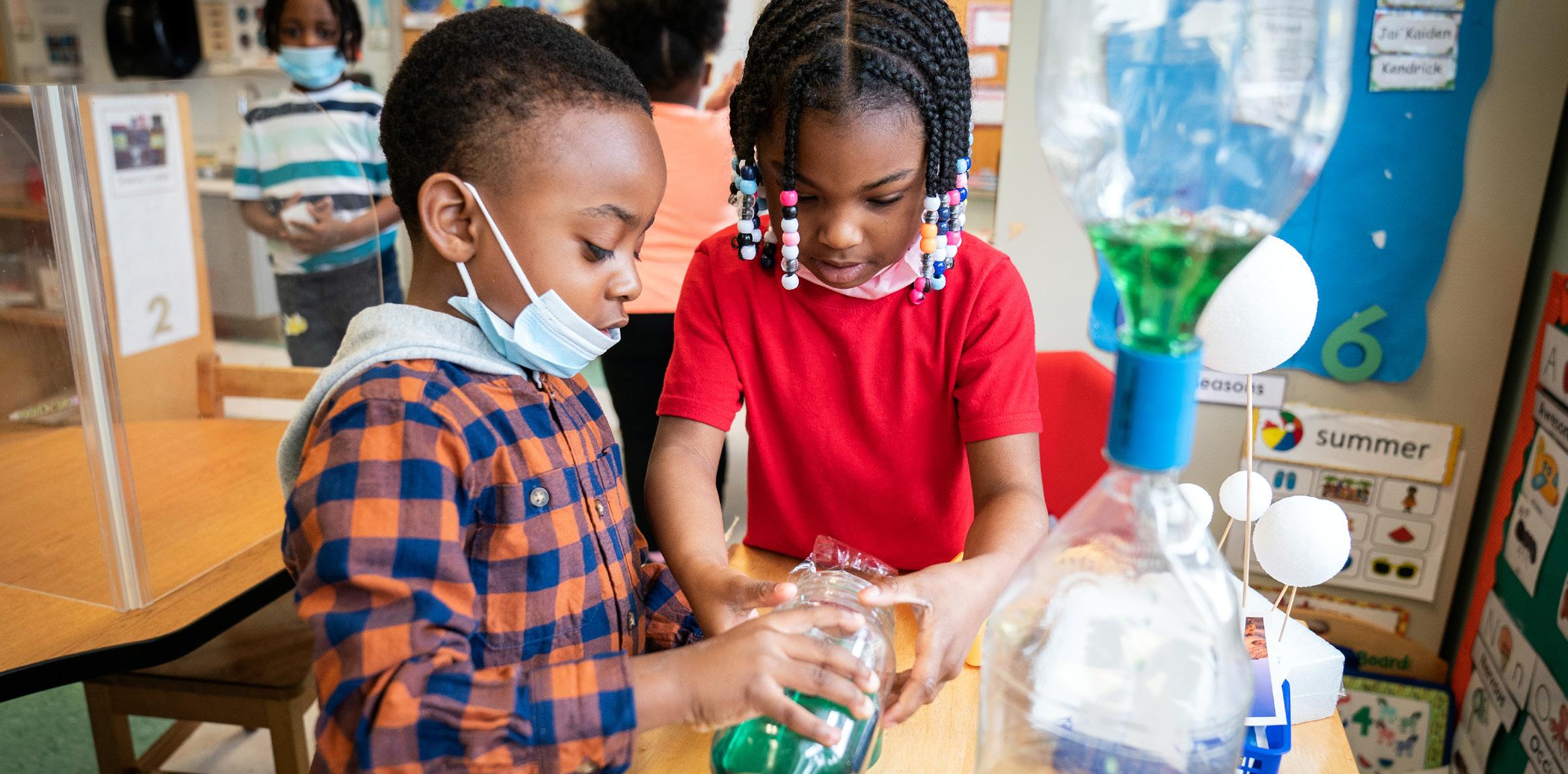

TWO PRE-K STUDENTS LEARN ABOUT SCIENCE AT ABERDEEN HEAD START, A SITE IN THE MONROE EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

childcare centers could reasonably participate [if they had to get to a 3]. Some Democrats were looking to use a different rating system to make it easier for childcare to join.” After listening to feedback, Barker introduced an amendment in the House to instead require “a nationally recognized assessment tool designed to document child learning outcomes.” (In other words, center quality would be measured by a national tool rather than Mississippi’s quality rating system.) However, that amendment tacked on language stating that the tool would be “the only additional measure of program quality allowable.” Advocates were concerned this language about “the only additional measure” might undercut the NIEER provisions as well as other accountability language in the bill. They were also concerned “child learning outcomes” was too vague. Ultimately, Barker and Wiggins amended the bill to require centers to implement a “nationally recognized assessment tool, approved by the State Department of Education, designed to document classroom quality…” Though some were never happy with any additional requirements, the compromise earned support among most childcare providers who had expressed concern.††

One part of the bill that turned into a pitched battle within the whole early childhood community was language to codify the State Early Childhood Advisory Council (SECAC) so that bill sponsors could define its role in relation to the ELCs as support, not an oversight body. Although the language about the composition of the SECAC was taken nearly verbatim from both the Head Start Reauthorization Act and the state executive order establishing the SECAC, it created an opportunity for competing factions to struggle for power. As Barker recalled, “There were a lot of childcare provider groups and advocacy groups that were all fighting over how the third part of our bill included a committee [ed. note: the SECAC], and everybody wanted to be in charge of the committee. And then they didn’t want these people on the committee. And we had to kind of get through that.” It was exactly the type of dispute that had prevented the early childhood community from gaining anything substantive from the legislature in the past. As Canter stated, “It took so much time and effort to ensure that the argument over the SECAC did not destroy the support we had built for the whole bill. The SECAC language wasn’t even critical; it had nothing to do with the actual program. The whole thing was maddening.”

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 20

††

“Brice and I worked really hard to try and iron out agreements.”

During implementation, MDE began requiring all providers, regardless of type, to implement the CLASS assessment tool, which satisfies the condition for childcare centers as well as ensures common requirements across collaborative partners. Since then, no one has objected to this language.

“ “

Toby Barker

A PRE-K STUDENT WORKS ON LITERACY SKILLS AT HAYES COOPER CENTER, A SITE IN THE CLEVELAND EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

The Role of Trustworthy Data and an Independent Voice

Both Wiggins and Barker point to the importance of Leaving Last in Line in making the case for pre-K. Representative Barker noted that “Mississippi First is data-driven, research-based, very robust. It’s the truth, not partisan,” such that legislators “can always trust what they are giving you.” Because Mississippi legislators do not receive staff and only work part time, they find trustworthy information particularly helpful. Reports like Leaving Last in Line and the Title I Pre-K Preliminary Report provided data to help center the pre-K conversation on what was happening in the state, and, according to Holly Spivey, served as “hard evidence about where we [were].”

Advocates, too, value the work of compiling trustworthy data.

Nita Thompson remarked, “Rachel [Canter] and her staff [put a lot of effort] in bringing people together, collecting data and evidence to support moving in one direction or pivoting in another direction. They made, and are making, a really good effort to paint an honest and accurate portrayal of the work that has been done, is being done, and needs to be done. They make a good effort, especially when collecting their data, to verify and make sure it’s accurate and giving people opportunities to share their information in a way that will be

useful as we continue to do this work and move forward.”

As a newer organization in the education policy community, Mississippi First was perceived by both advocates and legislators as more neutral than other organizations. According to Representative Barker, Mississippi First “didn’t have a long reputation of being on one side or another” and did not publicly call out legislators through “email blasts for voting a certain way.” Senator Wiggins agrees, “Mississippi First doesn’t have an agenda other than what’s best for the children in Mississippi. There is always, in Jackson, at the capitol, an agenda. Some people just want a contract with the state. Mississippi First wants what’s best for children of the state, and not some kind of political agenda.”

Cathy Grace also spoke about how the trust Mississippi First built with legislators helped the pre-K bill be successful. “This is my observation: Brice [Wiggins] and Toby [Barker] trusted Rachel. Rachel was laser focused on how she worked the legislature, and she did it every day… She didn’t have an army of people…but if you work there, you know, and in legislation, you have to be there almost every day. And again, it’s that relationship building that we’re talking about here that

she had to establish. Since we don’t have a staff for our legislature, which is so sad, you have to be an advocate and a staff person almost at the same time, because you’ll have people who will be positioned to say, well, you don’t need to use that money there, you need to use the money over here, or who said that’s going to work? And of course, she had enough national data to show that this program would work. It wasn’t like something that had never been done in the United States.”

For Jill Dent, the organization’s nonprofit status also allows them “to say and do things differently as an independent entity.” Employees of government agencies or who work for politicians, for example, may not always be able to openly express what they feel is right or may be prohibited from taking stances on issues seen as controversial. As an independent organization, Mississippi First can speak on any topic that is relevant to their work without fear or favor. They also have the freedom to disagree with prevailing notions—such as advocating for a real pre-K program—and their willingness to do so respectfully helps them stand out among other groups at the capitol. In short, when Mississippi First agrees with the position of a governmental

entity or other political player, legislators can trust that they have independently come to the same conclusion, and when Mississippi First disagrees, legislators take notice.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 21

“

“

“Mississippi First doesn’t have an agenda other than what’s best for the children in Mississippi. There is always, in Jackson, at the capitol, an agenda. Some people just want a contract with the state. Mississippi First wants what’s best for children of the state, and not some kind of political agenda.”

Brice Wiggins

Flying Under the Radar

Not only did this larger focus on education help the pre-K bill make it to the agenda in the first place, but it also helped secure its passage: whereas the other two bills on the agenda were controversial and time-consuming, the Early Learning Collaborative Act was bipartisan, had good polling numbers, and had a relatively small budget. Senator Wiggins said, “We knew this was an

We were kind of flying under the radar. And sometimes in the legislature, that’s the best thing.”

Barker elaborated, “I think we played second fiddle to the charter school debate…and the third-grade reading gate. And so this was kind of like a third or fourth priority, so it didn’t attract a whole lot of attention. And so that helped. [Rachel

Canter] really helped do a lot of the background work with Democrats so that we knew when you walk in and you need 62 votes in the House but you know you already got about 50 on the board, [it] makes it a lot easier.”

“We were trying to push these things simultaneously, and it worked,” Chairman Tollison remembered, but

that didn’t mean the path to passage was smooth. The coalition still had a rocky road ahead.

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 22

One important political dynamic that helped the pre-K effort was that it was part of a larger education reform package. opportunity...

PRE-K STUDENTS LINE UP FOR RECESS AT HAYES COOPER CENTER, A SITE IN THE CLEVELAND EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

An Overwhelming Majority

In 2013, the very conditions that made the pre-K bill’s introduction and initial support possible also made its final passage difficult. For Wiggins, his newcomer status meant, in his words, that he “wasn’t jaded [and]...wasn’t going to take no for an answer”—important qualities in a champion—but it also meant that the pre-K bill was his first attempt at getting major legislation through the Senate floor. Before the deadline for the first floor vote, Barker remembers that “we were all nervous what was going on down the hall [in the Senate] because [our bill] passed about an hour or two before theirs did.” The experience proved a trial-by-fire, even though the ultimate result was successful. Canter, too, had her own worries as her time was split between the pre-K bill and the charter school bill, one of the other major education bills being debated. The breadth of the education agenda had helped open a window for pre-K, but with Canter so central to two major bills, she felt the pressure: “I didn’t have time to blink for fear something would explode if I took my eyes off of it. That was the downside to having a session with so many active education bills.”

CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF TRANSFORMATIVE PRE-K 23

Any big piece of legislation must overcome a sense of inertia within the capitol before final passage, even one with as much support as the pre-K legislation.

A PRE-K STUDENT AND THEIR TEACHER HAVE FUN ON THE PLAYGROUND AT GREENWOOD HEAD START, A SITE IN THE GREENWOOD-LEFLORE COUNTY EARLY LEARNING COLLABORATIVE.

Of all the champions, Barker had the most difficult session as he experienced multiple personal tragedies in the lead up to passage. “A tornado hit my district; my dad died in the middle right before [the second committee] deadline day; and one of my legislative mentors took her own life. It was just an awful session when it came to personal tragedies. I remember coming back from my dad’s funeral, and our House education chairman took me aside just before I was about to present the Senate version and said, ‘Look, you may lose this pre-K bill on the floor.’ I mean, he just gave me that pep talk. He’s like, ‘Man, people just don’t want it.’”

By that time, both the House and Senate versions had passed their original chambers and the necessary committees in the opposite houses, and were each awaiting second floor votes. Throughout this process, it had been especially important for Barker and Wiggins to find not only a simple majority for each vote but at least sixty percent because the inclusion of the tax credit made the legislation into a tax bill, which requires a three-fifths vote. Any weakening of support at this point would have been fatal because there was no room for error. The opposition, though, had had more time to organize for the second floor votes and was increasing their attacks. After the House education chairman’s warning, Barker worked even harder to ensure the Senate bill would pass the House floor. “I remember really whipping that vote. And whipping the vote means, you know, making sure that you have the vote secure before you [present it on the floor], which is something that I always made a practice of, because [losing a] bill on the floor is humiliating. And so we really worked hard to get our votes in place and to get a compromise that everybody got to be on board with.”

After the House passed the Senate version (Senate Bill 2395) and returned it to the Senate for concurrence, the Senate allowed the House bill to die on the calendar and invited the

House to conference to hammer out a final bill. Conference weekend, as usual, coincided with budget weekend, meaning that not only did bill authors have to find agreement on final bill language, but they had to jockey for a budget line item in a tight budget season to make all their efforts to pass the enacting legislation worthwhile.

Once again, the bill champions hit a roadblock. It was Easter weekend, and Canter was preparing to go to church with her family when she got a call from Wiggins. “The good news was that we were getting money in the budget. The bad news was that it was going to be half what we originally thought,” Canter remembered. “I felt like Senator Wiggins and Representative Barker had really gone to the mat for this bill.” Barker also recalled conference weekend as being particularly dicey, “…We went to conference and then you started getting the last-minute people who are getting cold feet and saying, ‘I don’t think we should do this.’ There was a great deal of effort put into reassuring committee members and leadership that this was worth it.”

The conference report and the budget emerged with pre-K intact. The final hurdle, though, would be getting the conference report adopted by both houses—the third and final floor vote in both chambers. Canter remembered that the conference report went for final passage in both the House and the Senate at the same time—a rare occurrence: “I was flipping back and forth between listening to the House and Senate debate and nervous the entire time. Were we going to hold our votes together?”

As a last-ditch effort to tank the bill, some disgruntled members of the early childhood community tried to convince Black Caucus members that the bill would kill Head Start in Mississippi. These opponents, who did not represent any Head Start provider, had passed out flyers with misinformation about the bill’s teacher qualifications sections and