• Emotive

• Research

• Research

• Scope

2.1

2.2

• Emotive

• Research

• Research

• Scope

2.1

2.2

Architecture is more than just the arrangement of bricks and mortar. In my opinion, architecture is a medium of expression just like art. Just as how a painter uses colors and canvas to create a scene that evoke certain feelings, architects or designers wield materials, light, form etc to create spaces that stirs emotions, tell stories and communicate ideas. Emotive Architecture, refers to this approach of crafting spaces that intentionally evokes emotional responses from occupants or visitors.

To do this effectively, these buildings and spaces need to be designed in a way that they act like "resonators" (Tseng 2015). This means they should be built to strike a chord with the people who visit them. In practical terms, an architectural "resonator" involves designing a building so that its physical structure helps people to perceive and engage with the stories or histories it embodies and stir certain emotions.

This paper delves into the realm of Emotive Architecture, exploring how architectural elements and strategies can evoke emotional responses in built environments. By investigating the relationship between emotions and architecture, this research aims to provide insights into the profound impact that architectural design can have on human well-being and experience.

The aim of the proposal is to investigate the potential of built environments to evoke emotional responses through architectural elements and strategies, keeping in mind the context of immigrant’s emotional experiences.

To achieve this aim, the research first delves into an exploration of why people migrate, the impact of migration on society, and the concepts of memory and belonging. This background on Immigrants’ experience provides a deeper context for understanding the emotional journey of immigrants and how it can be represented in architectural design.

Furthermore, the research discusses the relationship between emotions and architecture, focusing on how built environments can evoke emotional responses. It begins by exploring the shift in design approaches that incorporate emotional engagement and includes a literature review on emotional design. It then dives into the role of sensory stimuli, examining how architecture engages the senses to evoke specific emotions in occupants. By highlighting the co-relation between senses and emotions, the chapter provides the theoretical foundation for designing emotionally resonant spaces.

Next, it presents an analysis of architectural case studies that evoke specific emotional responses—curiosity, discomfort, and hope. By examining buildings like Peter Zumthor’s Therme Vals (curiosity), Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum (discomfort), and the Baha’i Temple in Chile (hope), the chapter provides examples of how architectural elements such as spatial organization, materiality, and circulation can be used to provoke these emotions. A final section introduces a comparative table that links architectural strategies to specific emotional responses across all case studies.

The final chapter presents the design implementation of this research and outlines the process of creating a Migration Museum. It begins with an initial exercise in designing an architectural sculpture conceived as an experiential space aimed at evoking emotions associated with migration. This chapter then progresses to a detailed design proposal for the Migration Museum in Adelaide, integrating the insights gained from the research to create a space that embodies the emotional complexity of the migrant experience.

The research concludes with a summary and outlines future design and research possibilities for the subject related to migration, dislocation and belonging.

The research will contribute to the development of design methodologies that translate emotional experiences into architectural spaces, with a particular focus on specific emotions that represent the immigrant journey.

The findings can also be applied in the conceptualization and design of different temporary or permanent spaces such as pavilions or memorials that reflects the emotional complexity of the immigrant experience, ensuring that the space fosters empathy and engages visitors emotionally.

Designing architectural spaces that evoke emotional responses, particularly in the context of the immigrant experience, presents a unique set of challenges. Emotions are deeply personal, and translating the complex feelings of displacement, adaptation, and hope into physical spaces requires a thoughtful, sensitive approach. This research navigates several difficulties in achieving these goals, from the subjectivity of emotional responses to the complexity of immigrant experiences.

Key challenges include:

Subjectivity of Emotions: Emotional responses vary greatly between individuals, making it difficult to design spaces that evoke universal feelings like curiosity, discomfort, or hope.

Translating Emotions into Architecture: Turning abstract emotions into tangible architectural elements is challenging, requiring a balance between creativity and practicality.

Diverse Immigrant Experiences: Immigrant journeys differ widely, making it hard to capture the complexity without oversimplifying or generalizing.

Balancing Immersivity and Functionality: The design must engage visitors on a deeper emotional level while still being functional and practical for real-world use.

Cultural Sensitivity: Ensuring the design is culturally sensitive and avoids stereotypes requires in-depth research and care.

This research is primarily aimed at architects, interior designers, and urban planners who are interested in creating spaces that evoke emotional responses and foster deeper human connections. It also targets artists and exhibition designers working in immersive installations, as well as museum curators and cultural professionals involved in designing spaces that convey narratives of migration and identity.

Additionally, the research may appeal to psychologists and sociologists studying the emotional and psychological impacts of built environments, as well as academics and students in architectural and design fields who are exploring the intersection of emotion, culture, and spatial design. Finally, it could be relevant for policymakers and non-profits involved in community-building projects, particularly those focused on the immigrant experience.

The concept of studying emotions in the context of migration, as discussed in the journal article “Emotions on the Move: Mapping the emergent field of emotion and migration” (Boccagni & Baldassar 2015) highlights how emotions are crucial for understanding the migrant experience beyond economic or social factors. The article explains that emotions shape how migrants form relationships, adapt to new cultures, and stay connected to their homelands. By focusing on emotions, we gain a deeper insight into how migrants integrate into new societies, develop a sense of belonging, and navigate shifts in their identity. The article also emphasizes the role emotions play in influencing public opinion and political discourse about migration, while also exploring how migrants maintain ties with family across borders and interact with diverse communities. Overall, looking at emotional experience of immigrants, we can get a clearer picture of the personal challenges, social connections, and identity transformations that can help represent the migration experience.

The emotions that immigrants experience are complex and sometimes ambivalence. This concept is also woven throughout the article, “Emotions on the Move: Mapping the emergent field of emotion and migration” (Boccagni & Baldassar 2015), when discussing the emotional tension between immigrants’ hopes for a better life and the emotional challenges of leaving their homeland. The conflicting emotions of optimism with fear, discomfort and guilt are highlighted when addressing the migrant’s journey toward success while dealing with anxieties tied to home and family.

This exploration of emotions in migration, as outlined in Boccagni & Baldassar’s research, lays a vital foundation for understanding the deeper emotional complexities faced by immigrants. It reveals how emotions, beyond just social and economic factors, play a pivotal role in shaping their experiences, relationships, and adaptation in new societies. In designing spaces that capture these nuanced feelings, we are able to create

environments that speak directly to the immigrant journey.

To further delve into these emotions, it is important to examine key emotional themes, such as curiosity, discomfort, and hope, which are often experienced throughout the immigrant’s journey. These three emotions—curiosity, discomfort, and hope—capture the ambivalence of the immigrant experience, reflecting the complex layers of exploration, adaptation, and perseverance. Consequently, the design outcome will aim to evoke these emotions.

Driving through my personal experience, Immigrants often experience curiosity as they enter new environments and cultures. This curiosity drives them to explore unfamiliar landscapes, languages, and social systems. As they interact with diverse communities, they are eager to learn and unlearn, even as they navigate the uncertainties of an unfamiliar society. This sense of curiosity allows immigrants to broaden their worldview and integrate new cultural practices into their daily lives. In doing so, they embark on a journey of self-discovery, redefining their identity in relation to both their home and host countries.

However, alongside curiosity comes discomfort, which arises from the barriers and challenges that immigrants face in adapting to their new surroundings. This feeling is deeply tied to the struggles of learning new languages, navigating complex legal and social systems, and confronting discrimination or alienation. The emotional tension of discomfort is often amplified when immigrants reflect on their dislocation from their homeland, leaving behind familiar places and people. These experiences can create a lingering sense of unease, even as they work toward adapting to their new lives.

Despite the challenges, hope plays a critical role in the immigrant experience. Hope represents the resilience of individuals as they overcome obstacles, build new lives, and seek brighter futures for themselves and their families. It is sustained by the support they find in local communities, as well as the bonds they maintain with those they left behind. Hope is not only an emotional refuge but also a motivating force, propelling immigrants forward as they create new social connections, find economic opportunities, and continue their personal journey of growth and integration.

Emotions are an essential part of our existence. They are not just passive experiences but active and significant influencers of how we perceive the world and how we choose to interact with it. While the subject of emotions is traditionally studied within the realm of psychology, there is also a significant relationship between emotions and the built environment, including architecture (Malhotra 2022). Moreover, architecture has a significant impact on human behaviour. The study of neuroscience applied to build environment has proved that surroundings in fact evoke emotions and influence brain processes (Paiva 2018).

Thomas Heatherwick, an award-winning designer, also advocates for moving beyond monotonous designs that serve only the functional aspects of a built space, referring to this trend as “an epidemic of boringness.” He highlights the ‘emotional function’ of architecture, explaining that it can positively impact the overall well-being of its occupants and encourage social cohesion (Florian 2023). Thus, Emotive Architecture encourages a departure from focusing solely on functionality, efficiency, and aesthetics. Instead, it emphasizes evoking emotions that enhance the experience of a space (Şener 2023).

Overall, there is a need to shift our focus from merely addressing user needs to responding to user emotions in order to create impactful and memorable experiences. This shift can transform the overall well-being of the occupants. In my studio project I want to explore this non-traditional approach to designing spaces that adds value to the life or experience of the inhabitant or the visitor. I believe the spaces we inhabit greatly influence our perception of the world, shaping both physical creations and the overall health of society. This approach by architects or designers is mainly seen in projects of remembrance, such as museums or memorials, or in places of worship, such as temple and cathedrals. It would be interesting to see this in everyday used places such as workplaces, residences, retail stores or even hospitals.

Furthermore, majority of literature relating emotions and architecture focuses on either neurophysiological correlation or the psychological aspect of built environments. Some literatures focuses on the interaction between user and their environment through the lens of ergonomic studies and industry standards. It highlights the crucial need for a balanced approach between designing spaces that are safe and compliant with standards and spaces that are also emotionally resonant with the users (Reddy, Chakrabarti & Karmakar 2012).

Another journal article, through a range of case studies, examines the intersection of architecture and psychology, highlighting the significant impact architecture has on human emotions. This studies include a public space in Berlin, a health environment in Sweden and a fitness center in Denmark illustrating how architectural elements can evoke a range of emotions including isolation, relief etc. It highlights a need for holistic approach that consider how all the combined architectural elements influence psychological well-being (Roessler 2012).

In conclusion, emotions play a pivotal role in shaping our interactions with the built environment, underscoring the significance of Emotive Architecture in contemporary design. As highlighted by industry professionals and supported by research, architecture goes beyond mere functionality and structure. While existing literature predominantly focuses on neurophysiological and psychological aspects, there is a growing recognition of the need for a balanced approach that integrates emotional resonance with functional requirements and budget constraint.

The intricate relationship between our senses and emotions forms the foundation of emotive architecture. This chapter explores how sensory stimuli from our environment directly influence our emotional and behavioral responses, establishing a crucial link for architectural design. It uses the conceptual framework outlined by Schreuder et al. (2016), to delve into the dynamic interplay between multisensory stimuli and human emotional responses, emphasizing the implications for architectural design. This proposed framework suggest that our perception of the environment is not a mere sum of isolated sensory inputs but a complex, multisensory integration that shapes our emotional and behavioral landscape. This integration occurs through a series of lower and higher order processes that begin with basic sensory detection and culminate in sophisticated emotional and cognitive outputs (Schreuder et al. 2016). The framework also highlights how The five senses (Mads Berg 2012)

multisensory stimuli interact to produce amplified and nuanced emotional responses (Schreuder et al. 2016). In the context of architecture, this suggests that a harmonious integration of sensory elements—light, sound, texture, and scent—can enhance the emotional impact of a space. For example, the congruence between the warm lighting and natural wood textures can evoke feelings of warmth and comfort, which is crucial for most residential spaces.

Furthermore, as noted in the research by Schreuder et al. (2016), congruency in sensory stimuli plays a vital role in the perception and emotional impact of an environment. Architectural design can leverage this by ensuring that sensory elements complement each other, thereby reinforcing the intended emotional effect, whether it be calm in a spa or alertness in an office space.

The context also plays a role in modulating emotional responses (Schreuder et al. 2016). This adaptability highlights the need for architects to consider the function and context of each space meticulously, ensuring that sensory elements are aligned with the intended use of the space.

I believe, modern architectural spaces merely serves as physical shelters for performing intended tasks and lacks the ability to engage occupants or visitors emotionally. Despite being visually pleasing, today’s architecture often feels devoid of distinctiveness and character. Rather than creating the ‘trendy’ designs, architects and designers should focus on creating enriching environments or ‘atmospheres’ (in the words of Peter Zumthor) that enhance the experience of being in the space.

In designing this experiences, emotions play a critical role. They are influenced by our senses - what we see, hear, touch and smell. These sensory experiences provide cues that can evoke memories, spark imagination, and integrate our experiences, making our interactions with spaces memorable (Hernandez 2019). Just how a film can take us into a different world, architectural atmospheres can profoundly impact our emotions and mood. Just how a resonating story can have a deep emotional impact on viewers, an emotionally resonating space can connect to individuals on a personal level, enhancing their sense of being and their connection to the outer world.

According to architect Juhani Pallasmaa (2005), architecture should support a deep and meaningful experience of being in the world, grounding us in reality rather than detaching us into fantasy. It should appeal to all our senses, melding our selfimage with our environmental experiences.

In our everyday lives, our actions and emotions are intertwined with the environment we inhabit, encompassing both natural landscapes and man-made structures. The significance of our behaviors and moods relies on how they relate to the context of our surroundings. For instance, our actions are constrained and/or facilitated by physical barriers like walls, doors and windows or the presence of the specific furniture piece. Therefore, when we alter our environment to create buildings that caters to human activities, we enhance and transform our experiences within those spaces. Robert Gifford (2002) defines this field of inquiry as ‘environmental psychology - the study of the interactions between individuals and their physical surroundings’.

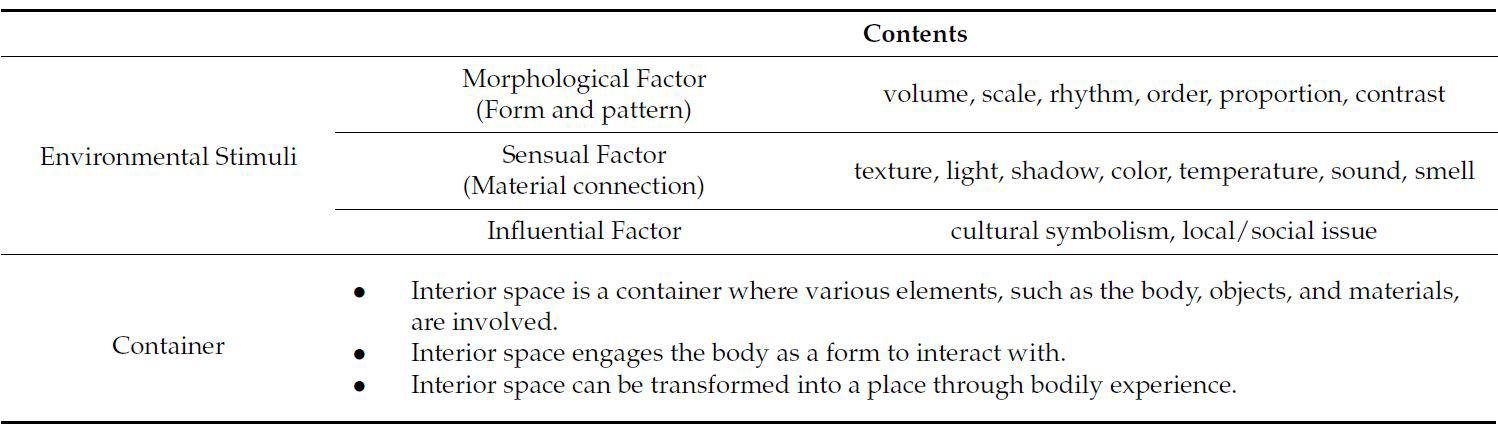

Built spaces are comprehensible not only through their architectural shapes but also through their connections with the body, environmental stimuli, and cultural contexts (Lee 2022). These connections establish the significance of space through experiential interactions. Keunhye Lee (2022) In his insightful categorization, identifies three distinct factors within interior spaces that serve as mediums to evoke emotions. These factors include the Morphological Factor , which encompasses elements such as volume, scale, rhythm, order, proportion, and contrast; the Sensorial Factor, which relates to the material connection through texture, light, shadow, color, temperature, sound, and smell; and the Influential Factor , which draws upon cultural symbolism and local or social issues. Each of these components play a crucial role in how interior spaces are experienced and interacted with, transforming mere spaces into meaningful places through the bodily experiences they facilitate.

Therme Vals is a renowned spa complex that explores how architectural design can evoke feelings of curiosity and encourage exploration.

Connection to the landscape: The primary material used in the complex is locally quarried Valser quartzite, giving a camouflaging effect from the outside. The use of stone throughout the interiors creates a monolithic, almost cave-like atmosphere that feels both protective and mysterious.

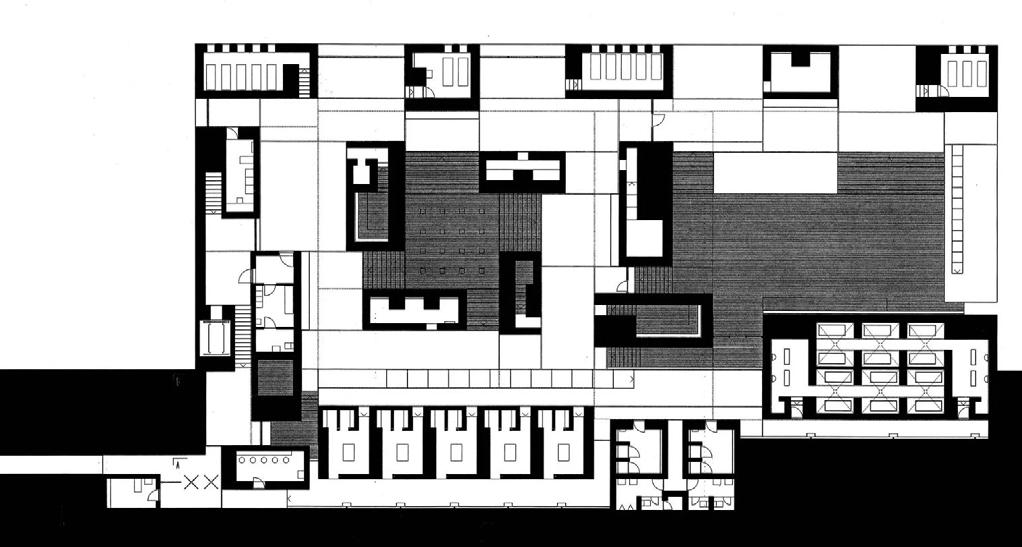

Spatial Organization: There are series of narrow corridors and low-lit passageways that open up to larger bathing areas. This creates a sense of curiosity. Various pools are tucked away in different parts of the complex, each with unique characteristics (e.g., different temperatures, lighting conditions, and acoustic properties). This arrangement encourages exploration as visitors seek out these hidden gems, creating a journey of gradual discovery.

Role of Light:

In the whole complex, natural and artificial lighting is used strategically to highlight certain areas while keeping others in shadow, enhancing the contrast between revealed and concealed spaces. Skylights, small windows, and light slots create dynamic lighting effects that change throughout the day. This strategic use of light enhances the contrast between revealed and concealed spaces.

The Jewish Museum in Berlin, designed by architect Daniel Libeskind was conceived to represent the Jewish presence in Berlin after the devastation of World War II. It does not have any direct entrance and is only accessible by an underground passage from the old Berlin museum adjacent to it. Here, I have analyzed the project to understand what architectural decisions help in creating certain emotions, which then can be used as a tool to enhance my studio project.

The façade of the building is cladded with zinc panels with perfect vertical line but skewing horizontal seems. Adding to this is seemingly random punctures in the shape of angular lines, gives a feel of distortion and disorientation which represents the turbulent history of Jews in Germany. Upon entering, the zig-zag circulation of the building guides visitors through a disjointed journey, mirroring the fragmented experiences of the Jewish people. Guided movements through these disorienting spaces reflect forced migrations experienced by Jews. Deliberate disorder, with dead ends and empty spaces, reflects the chaos of the Holocaust. Unusually proportionate spaces evokes the feelings of confinement or overwhelm.

Materiality plays an important role in enhancing the emotional stimulation. The rough texture of unfinished concrete walls conveys harshness and suffering, echoing the Jewish people’s brutal experiences. Minimal natural light through narrow slits, shadowy spaces, and monochromatic colors create a somber atmosphere, punctuated by moments of hope and reflection. Cool temperatures, unheated spaces and echoing footsteps imparts a sense of abandonment.

Overall, by engaging with cultural symbols, local context, and human experiences, the museum creates a powerful emotional journey for visitors.

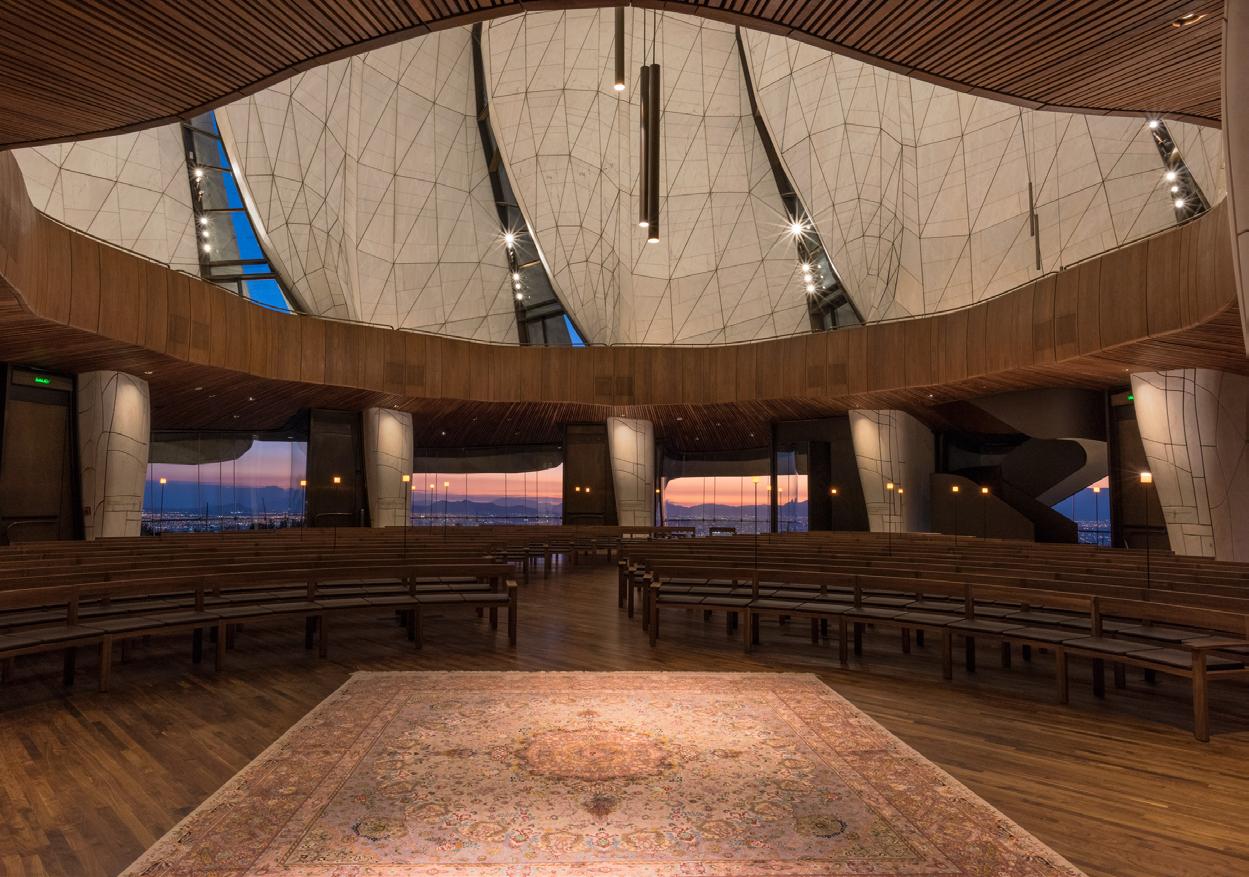

The curving, organic form of the wings promotes a sense of inclusiveness and unity, echoing the Baha’i principle of oneness. The soft, flowing lines create a serene and peaceful atmosphere conducive to contemplation and spiritual connection. Curved wooden benches encourages visitors to engage in quiet contemplation together. It fosters a sense of connection and community, aligned with the Baha’i values of unity and fellowship.

The exterior of the building is covered with cast-glass panels and interiors are cladded with translucent marble. During the day, natural light filters through the glass and marble, casting gentle, shifting patterns of light and shade within the space. At night, the temple glows softly from within like a lantern. This use of light evokes hope and spiritual upliftment, creating a tranquil and contemplative environment.

Building on Lee’s framework, which categorizes key architectural elements and their collective impact on emotional responses, the following charts provide a comprehensive overview of previous case studies. The analysis is divided into three primary factors: Sensorial, Morphological, and Spatial Planning. It illustrates how specific architectural attributes in each project evoke particular emotions, offering a valuable reference for designers. This chart serves as a practical tool, guiding architects and designers toward the architectural or design factors that should be prioritized to achieve desired emotional effects in their spatial projects

strategy

Emotions / Narrative Project

Jewish Museum

Architectural elements / strategy

Angular, skewing lines

Unusually proportionate spaces, Deliberate disorder

Distortion, Turbulance, Disorientation

Intimidation Confinment

Voids Loss, Absence, Emptiness

Slanted surfaces Imbalance Monolithic

Curving form

Inclusiveness, Unity, Togetherness

Emotions / Narrative Project

Jewish Museum

Architectural elements / strategy

Zig-zag circulation path

Baha’i Temple

Therme Vals

Forced circulation

Curving seating layout

Sequential layout

Fragmentation

Restrictions, VDependence, Lack of freedome

Encourage dialogue

Exploration, Curiosity

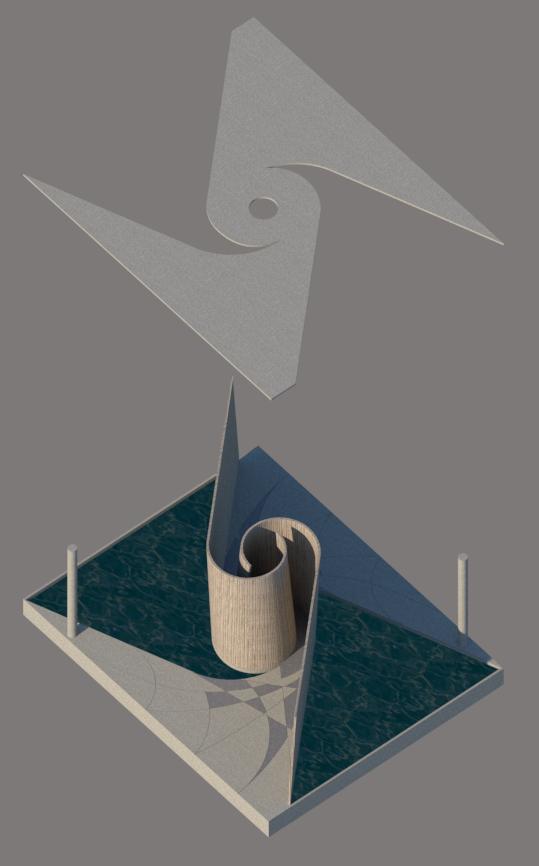

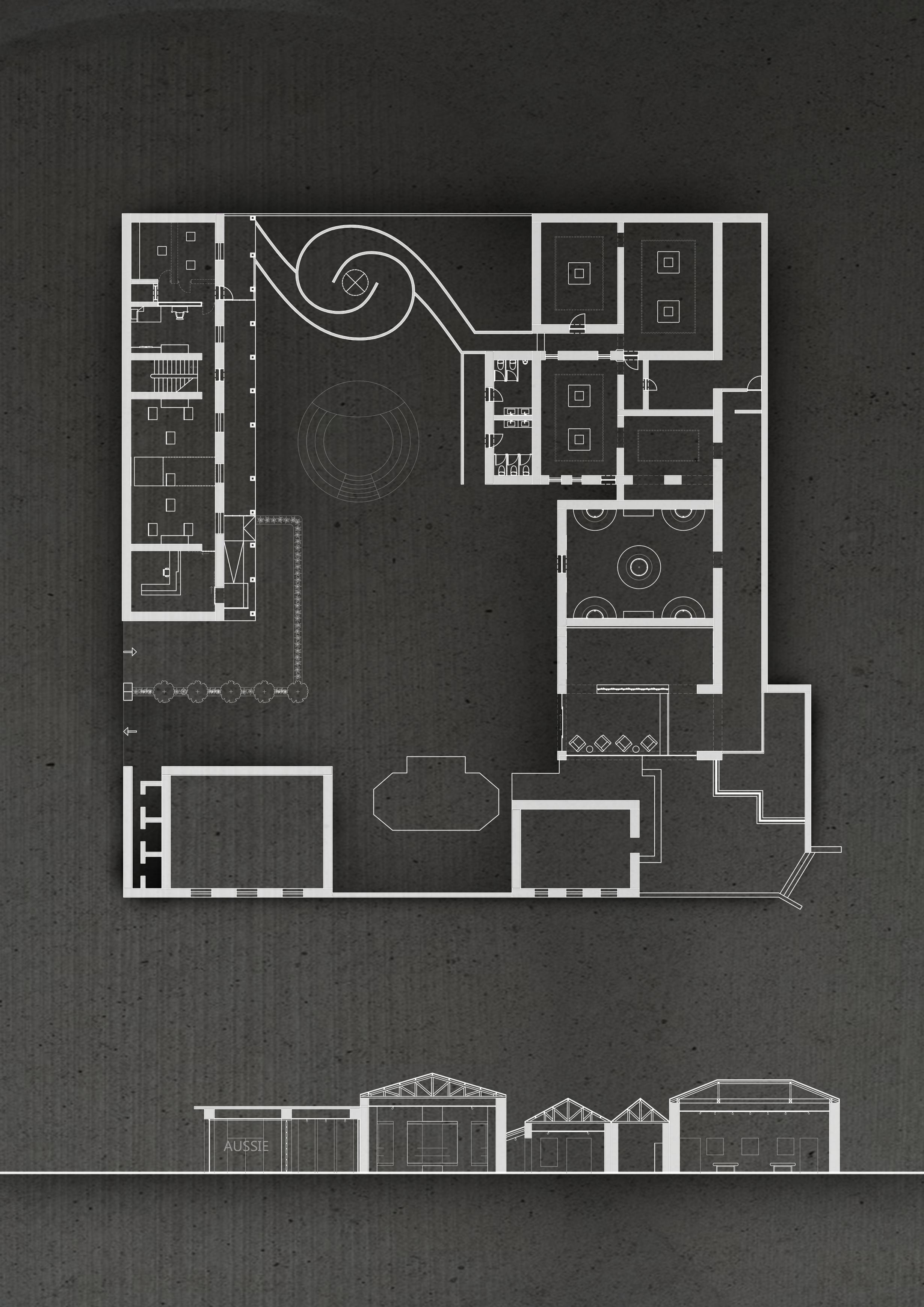

The implimentation of this research started with designing an architectural sculpture that aimed to evoke emotions such as curiosity, discomfort, and hope—central themes in the immigrant experience. However, it had several limitations, particularly in achieving the broader objective of fostering empathy for the immigrant community.

For instance, the pavilion featured a single linear path, which constrained the spatial exploration. It also lacked communal spaces, focusing solely on individual experiences. While solitary exploration can intensify emotional engagement, it reduced opportunities for collective interaction and dialogue. Additionally, the short circulation path limited the duration of the experience, diminishing the potential for deeper emotional engagement.

In response to these challenges, the design was revised to address these limitations. The program was expanded to include spaces for object and art exhibitions themed around migration, dislocation, and memory. This enhanced approach reimagines the Migration Museum in Adelaide, offering a more immersive and multifaceted experience that fosters both individual and collective emotional engagement.

To address these limitations, the final design proposal incorporates aims to create a Migration Museum with emotionally resonant, immersive spaces that foster a more profound empathy and understanding of the immigrant community.

• Immersive environment: Create immersive spaces that deeply engage visitors with the challenges and journeys of the immigrant community, fostering empathy and understanding through carefully designed sensory stimuli, architectural forms, and spatial planning.

• Encourage Reflection: Design spaces that prompt visitors to reflect on their own perceptions of immigration and the community.

• Encourage Dialogue: Create a platform that celebrates multiculturalism, diverse identities, histories and cultures, which prompts visitors to engage in meaningful discussions.

The selection of the site was straightforward, as Adelaide already hosts a Migration Museum, located on North Terrace behind the State Library on Kintore Avenue. The museum does not have a prominent street presence compared to other buildings along North Terrace.

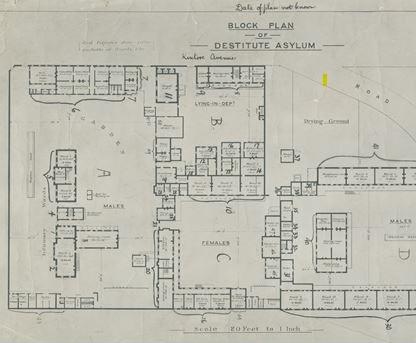

The Migration Museum is situated within heritage-listed buildings that were once part of the Destitute Asylum complex, a significant site in the history of South Australia’s social welfare system. Although the pre-colonial use of the site remains unclear, by the 1850s, the asylum had expanded considerably. Today, the remaining structures, highlighted in the block plan, accommodate the current museum.

The museum can be divided into four zones. The redhighlighted section represents the site’s historical narrative, detailing its past as a women’s lying-in home and a chemistry laboratory. The green zone is the main museum area, housing both temporary and permanent exhibits. Grey areas indicate unused space, while the remaining parts are outdoor areas.

The current layout and circulation of the museum are quite linear, leading visitors through exhibit after exhibit without providing reflective or immersive spaces. This limits the ability of visitors to absorb the emotional essence of migration beyond just factual information.

Current zoning

1. Reception

2. Temporary display on wall

3. Temporary exhibition

4. Temporary exhibition

5. Temporary exhibition

6. Permanent exhibition

7. Permanent exhibition

8. Site history exhibition

9. Site history exhibition

The ambiance is largely neutral or warm, which does little to evoke strong emotional or empathetic responses. The displays themselves are traditional and heavily reliant on text, which can overwhelm visitors and hinder deep engagement with the content.

While there are some audio-visual elements , these fail to create an immersive experience due to the small screen sizes, viewing distances, and the overall lack of an enveloping environment.

Finally, the absence of community spaces significantly reduces the potential for fostering collective emotional responses and empathy among visitors.

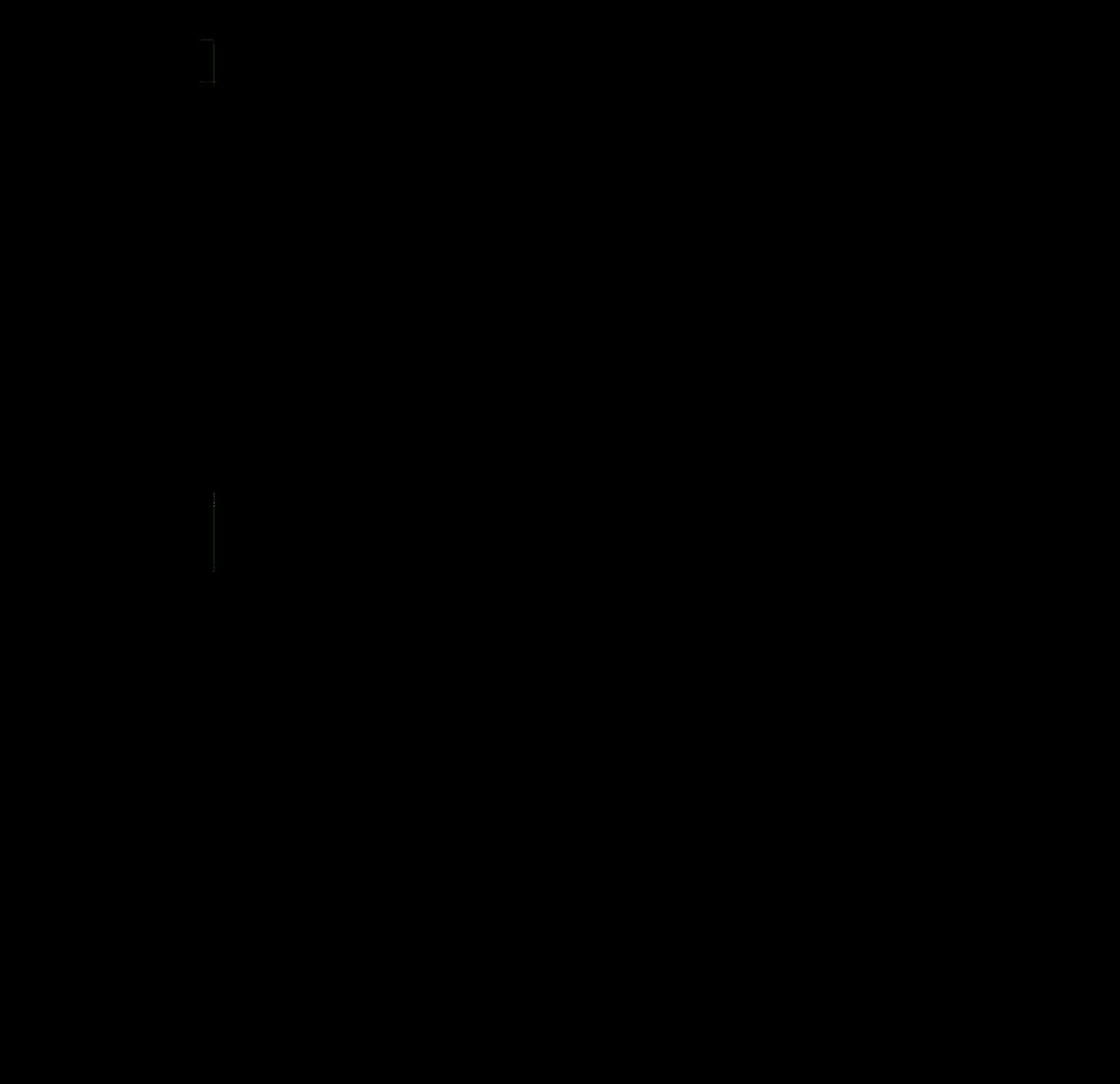

Spatial zoning

Exhibition areas

Immersive transition space

Direct connectivity

Close proximity

The spatial zoning for a migration museum is done keeping in mind the intentional connectivity and proximity between various functional spaces.

At the entrance, the reception serves as the central point of orientation, immediately linking visitors to the Site History Exhibition, which provides crucial context for the museum’s overarching narrative. Permanent and Temporary Exhibitions are positioned to offer distinct yet interconnected experiences, promoting seamless transitions between long-term narratives and contemporary perspective on migration, while the Migration Now exhibition, located near the exit, serves as a reflective space, allowing visitors to conclude their journey with contemporary insights, highlighting the ongoing nature of migration. The immersive areas between this exhibition spaces serves as contemplative spaces.

The proximity of administrative areas to the reception facilitates operational efficiency. Storage is closely connected to the temporary exhibitions, supporting logistical needs and exhibit changes efficiently.

The Multipurpose Area, located centrally, connects directly to both exhibition spaces and adjacent functional areas, ensuring flexibility for events, workshops, or gatherings that enrich the museum experience.

Reception

Site history

Matron’s room’s replica

Chemistry lab equipment display

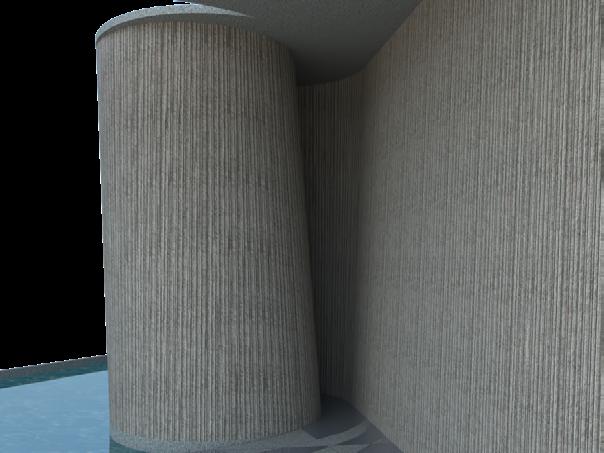

Architectural sculpture

Temporary exhibition

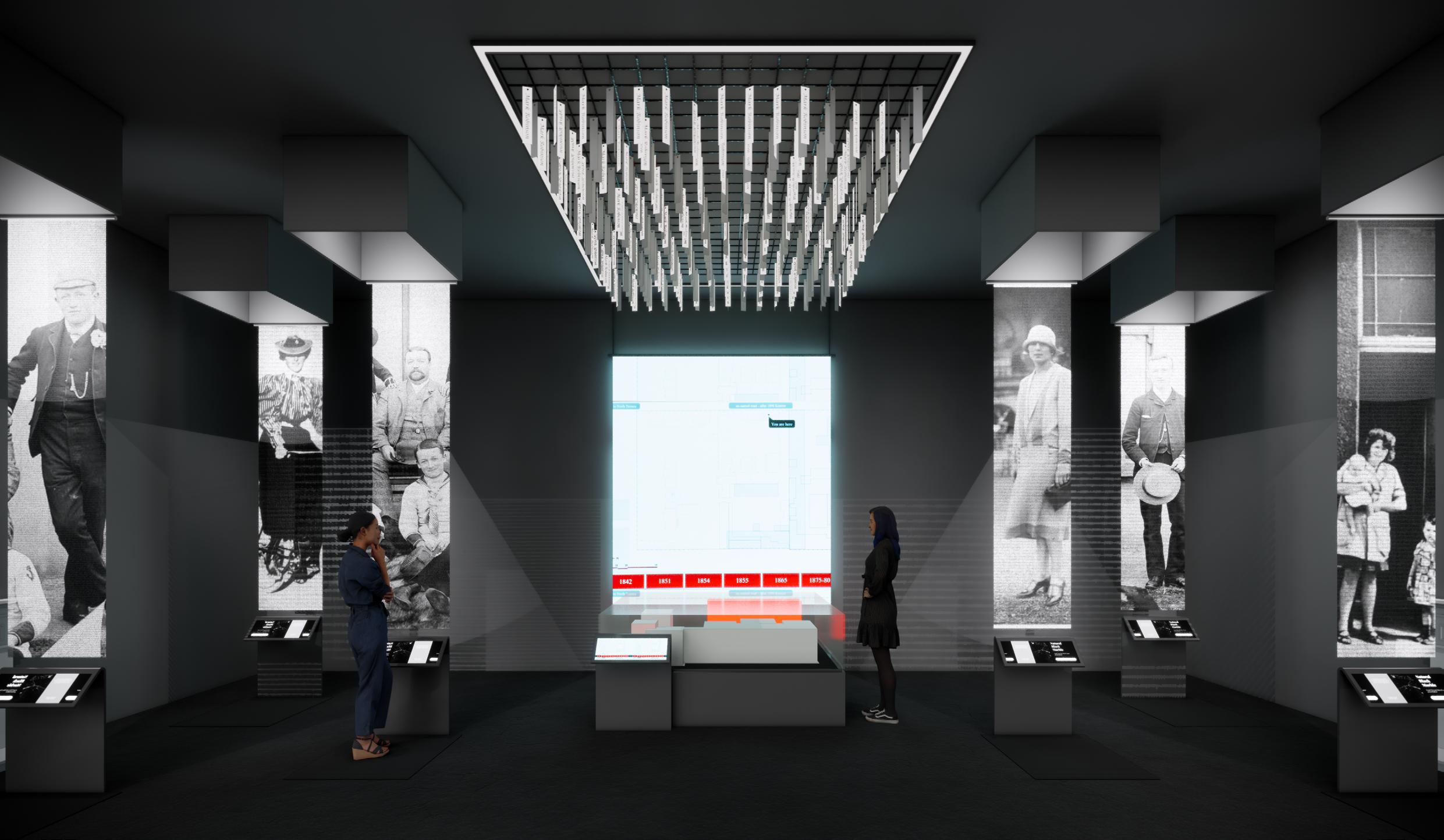

Immersive passage (world history timeline display)

Permanent exhibition 12. Migration in 21st century

Multipurpose area

The museum entry is located on Kintore Avenue, where visitors are guided by carefully curated vegetation leading to the reception area. This serves as the introduction point for the entire museum experience, welcoming visitors and providing essential orientation.

SITE HISTORY EXHIBITION

The site history exhibition is divided into three distinct sections. The first exhibition hall provides an overview of the site’s evolution over time, featuring interactive displays. It also shares personal stories from individuals who lived at the site during its time as a destitute asylum.

SITE HISTORY EXHIBITION - CHEMISTRY LAB

The second section is a faithful replica of the matron’s room, showcasing original furniture to recreate the historical setting. And the third section displays equipment used by the Department of Chemistry, which occupied the space at a certain point in the site’s history.

The architectural sculpture serves as a physical and emotional connector between the site’s two buildings, offering an immersive space where visitors can pause and reflect on their museum experience. The design uses form, circulation, and lighting to evoke emotions such as curiosity, discomfort, and hope, echoing the immigrant journey.

TEMPORARY EXHIBITION AREA

The temporary exhibit space is designed to house rotating displays with dynamic, evolving content related to migration. The area features a modular track lighting system and flexible furniture, allowing the layout and ambiance to be adjusted according to the specific requirements of each exhibit.

PERMANNT EXHIBITION

The permanent exhibition space showcases personal belongings brought by migrants, illustrating the diversity of cultures and lifestyles that have shaped the fabric of the city over time. These objects highlight the gradual merging of traditions that immigrants brought with them.

GLOBAL HISTORY TIMELINE

The immersive corridor shown in the image serves as a transitional space that connects the temporary and permanent exhibition areas of the museum. Designed to evoke a sense of movement through time, the corridor features a global history timeline, with significant moments displayed along its length.

MIGRATION NOW

This section of the museum focuses on contemporary migration patterns. It features a large digital screen displaying demographic data on migration to and from Australia, outlining the primary reasons for migration today. Additionally, a partition screen with louvered panels presents portraits of individuals on one side, while key emotions such as hope and nostalgia are inscribed on the reverse, offering a multi-layered emotional reflection on migration.

Lounge area is a buffer space between migration now and exit door. A partition screen with louvered panels presenting portraits of individuals on one side, while key emotions such as hope and nostalgia inscribed on the reverse, divides these two spaces, offering a multi-layered emotional reflection on migration. It is furnished with comfortable seating, providing a space for visitors to relax and contemplate the museum journey.

The centrally located outdoor multipurpose area functions as a flexible event area that can accommodate gatherings, performances, or community events and also as outdoor seating space. MULTIPURPOSE AREA

In conclusion, this thesis explores the intricate relationship between architecture and the emotional experiences of immigrants. By delving into the psychological and emotional journeys faced by migrants—such as leaving their homelands, adapting to new cultures, and grappling with feelings of displacement—it provides a nuanced context for understanding the immigrant experience. The historical overview of immigration waves and the examination of trends and patterns in migration have highlighted the multifaceted nature of these experiences, emphasizing the importance of memory and belonging in shaping identity.

Furthermore, the research underscores the significance of designing spaces that resonate emotionally with visitors. By analyzing how emotions like curiosity, discomfort, and hope manifest within the immigrant experience, this study advocates for architectural approaches that intentionally evoke emotions. Drawing from established theories and case studies in emotive architecture, the findings elucidate how architectural elements such as spatial organization, materiality, and sensory engagement can foster emotional connections between the space and its occupants. This connection is pivotal in creating environments that encourage reflection and empathy.

The insights gained from this research have directly informed the design principles for the Migration Museum, ensuring that the final architectural outcome serves not only as an informative exhibit but also as an immersive experience that resonates deeply with visitors. By integrating the complexities of the immigrant journey into the design, the museum aims to evoke emotional responses that foster understanding and connection among its audience. Ultimately, this thesis advocates for a transformative approach to architectural design, where the emotional dimensions of the human experience are at the forefront, enriching both the architectural narrative and the visitor experience.

The research on “Emotive Architecture: Emotional Engagement in the Architectural Design of the Migration Museum” paves the way for several future possibilities that can enhance the understanding and application of emotive design principles.

Future studies could expand the framework of emotive architecture to diverse building types, such as community centers and healthcare facilities, to explore how emotional engagement varies across different contexts. Additionally, interdisciplinary collaborations among architects, psychologists, and sociologists could yield insights into integrating emotional and psychological theories into architectural practice, fostering spaces that cater to the complex emotional needs of users.

Furthermore, the incorporation of technological advancements, such as virtual and augmented reality, could create immersive experiences that deepen visitor engagement with the immigrant narrative. By evaluating the long-term emotional impact of such designs and considering the voices of diverse communities in the design process, future research can contribute significantly to developing public spaces that promote belonging and social cohesion, thereby enhancing the emotional resonance of built environments.

1. Gutierrez, L, viewed 23/10/2024, <https://au.pinterest.com/pin/607493437266317860/>.

2. Berg, M 2012, The five senses, viewed 23/10/2024, <https://www.behance.net/gallery/3068845/The-five-senses>.

3. Lee, K 2022, Characteristics of interior space, 'The Interior Experience of Architecture: An Emotional Connection between Space and the Body', Architecture: Integration of Art and Engineering.

4. Ceriani, A 2009, Therme Vals exteriors, <https://www.archdaily.com/13358/the-therme-vals>.

5. Binet, H 2024, Therme Vals lighting, <https://archeyes.com/peter-zumthors-therme-vals-sensory-architecturein-an-alpine-retreat/>.

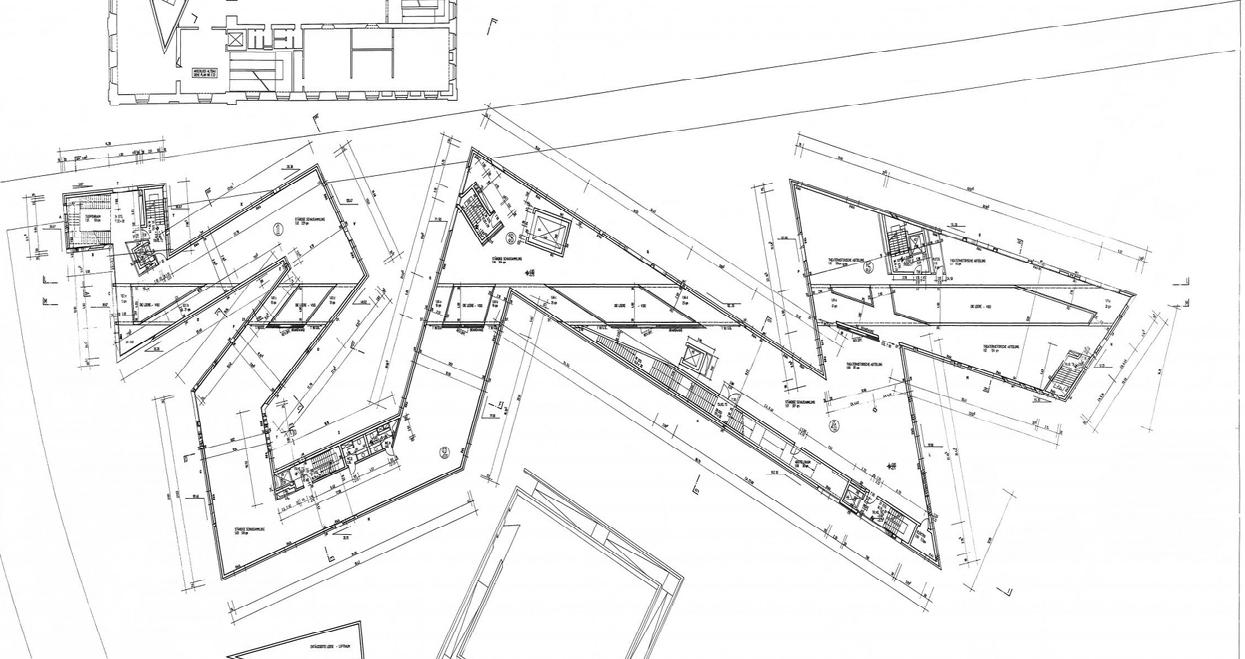

6. Zumthor, P 1996, Therme Vals floor plan, <https://archeyes.com/peter-zumthors-therme-vals-sensory-architecture-in-an-alpine-retreat/>.

7. Esakov, D 1999, Jewish Museum facade, <https://www.archdaily.com/91273/ad-classics-jewish-museum-berlin-daniel-libeskind>.

8. Esakov, D 1999, Jewish Museum vertical void, <https://www.archdaily.com/91273/ad-classics-jewish-museum-berlin-daniel-libeskind>.

9. Esakov, D 1999, Jewish Museum materiality, <https://www.archdaily.com/91273/ad-classics-jewish-museum-berlin-daniel-libeskind>.

10. Libeskind, D 1999, Jewish Museum ground floor plan, <https://www.archdaily.com/91273/ad-classics-jewish-museum-berlin-daniel-libeskind>.

11. McKnight, J 2017, Baha’i temple translucent surface <https://www.dezeen.com/2017/04/10/bahai-templesouth-america-chile-hariri-pontarini-architects-features-torqued-wings-steel-glass/>.

12. McKnight, J 2017, Baha’i temple materiality, <https://www.dezeen.com/2017/04/10/bahai-temple-southamerica-chile-hariri-pontarini-architects-features-torqued-wings-steel-glass/>.

13. McKnight, J 2017, Baha’i temple exterior surface <https://www.dezeen.com/2017/04/10/bahai-temple-southamerica-chile-hariri-pontarini-architects-features-torqued-wings-steel-glass/>.

14. McKnight, J 2017, Baha’i temple interior <https://www.dezeen.com/2017/04/10/bahai-temple-south-americachile-hariri-pontarini-architects-features-torqued-wings-steel-glass/>.

15. McKnight, J 2017, Baha’i temple natural light <https://www.dezeen.com/2017/04/10/bahai-temple-southamerica-chile-hariri-pontarini-architects-features-torqued-wings-steel-glass/>.

16. SA, SL 1918, Destitute Asylum, Adelaide.

17. Unknown, Block plan of Destitute Asylum.

18. maps, G 2024, Site map, <https://www.google.com.au/maps/place/Migration+Museum/@-34.9197292,138.599663,17z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m6!3m5!1s0x6ab0ced4e58bc541:0x66d74714972d8ab a!8m2!3d-34.9197336!4d138.6022379!16s%2Fm%2F0gjdvqy?entry=ttu&g ep=EgoyMDI0MTAyMC4xIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D>.

1. Boccagni, P & Baldassar, L 2015, ‘Emotions on the move: Mapping the emergent field of emotion and migration’, Emotion, Space and Society, vol. 16.

2. Florian, M-C 2023, ‘Emotional Architecture: How Contextual Solutions Can Fight against the “Epidemic of Boringness”’, <https://www.archdaily.com/1002817/emotional-architecture-how-contextual-solutions-can-fight-against-the-epidemic-of-boringness>.

3. Gifford, R 2002, Environmental Psychology: Principles and Practices, Optimal Books,

4. Hernandez, AJU 2019, ‘Architecture and Emotions: Defining the relationship in between Spatial Composition and Sensory Reactions’, The Leeds School of Architecture, Leeds Beckett University.

5. Lee, K 2022, ‘The Interior Experience of Architecture: An Emotional Connection between Space and the Body’, Architecture: Integration of Art and Engineering.

6. Malhotra, A 2022, ‘Emotional architecture’, viewed 24/03/2024, <https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/ Emotionalarchitecture>.

7. Paiva, Ad 2018, ‘Emotions & Senses: the relationship between architecture, emotion and perception’, ANFA 2018 Conference.

8. Pallasmaa, J 2005, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, 2nd edn, London Academy Press,

9. Reddy, SM, Chakrabarti, D & Karmakar, S 2012, Emotion and interior space design: an ergonomic perspective.

10. Roessler, KK 2012, ‘Healthy Architecture! Can environments evoke emotional responses?’, Global Journal of Health Science, vol. 4.

11. Schreuder, E, van Erp, J, Toet, A & Kallen, VL 2016, ‘Emotional Responses to Multisensory Environmental Stimuli:A Conceptual Framework and Literature Review’, Sage Open, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 2158244016630591.

12. Xener, EM 2023, ‘Emotive Architecture: Designing Spaces That Evoke Emotions’, <https://medium.com/@mengen794/emotive-architecture-designing-spaces-that-evoke-emotions-7703cbf6809f>.

13. Tseng, C-P 2015, ‘Narrative and the Substance of Architectural Spaces: The Design of Memorial Architecture as an Example’, Athens Journal of Architecture.