Experience the thrill of big game hunting in Alaska’s untamed wilderness with Deltana Outfitters—Alaska’s premier guide service. Whether you’re after Brown Bear, Grizzly, or Moose, our expert guides lead unforgettable Spring and Fall hunts in the remote, pristine Alaska Peninsula and Western Alaska.

Adventure. Expertise. Results. That’s what we do—and Deltana does it best.

90% Success Rate! Average Moose: 64” Grizzlies: 7’6” - 8’6” Black Bears: 6’ - 7’ Brown Bears: 9’ - 10’

PUBLISHER

James R. Baker

GENERAL MANAGER

John Rusnak

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Andy Walgamott

EDITOR

Chris Cocoles

WRITERS

Landon Albertson, Michael Engelhard, Scott Haugen, Tiffany Haugen, Tiffany Herrington

SALES MANAGER

Paul Yarnold

ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE

Janene Mukai

DESIGNER

Kha Miner

WEB DEVELOPMENT/INBOUND

MARKETING

Jon Hines

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Katie Aumann

INFORMATION SERVICES MANAGER

Lois Sanborn

ADVERTISING INQUIRIES media@media-inc.com

MEDIA INDEX

PUBLISHING GROUP

941 Powell Ave SW, Suite 120

Renton, WA 98057 (206) 382-9220 • Fax (206) 382-9437 media@media-inc.com www.media-inc.com

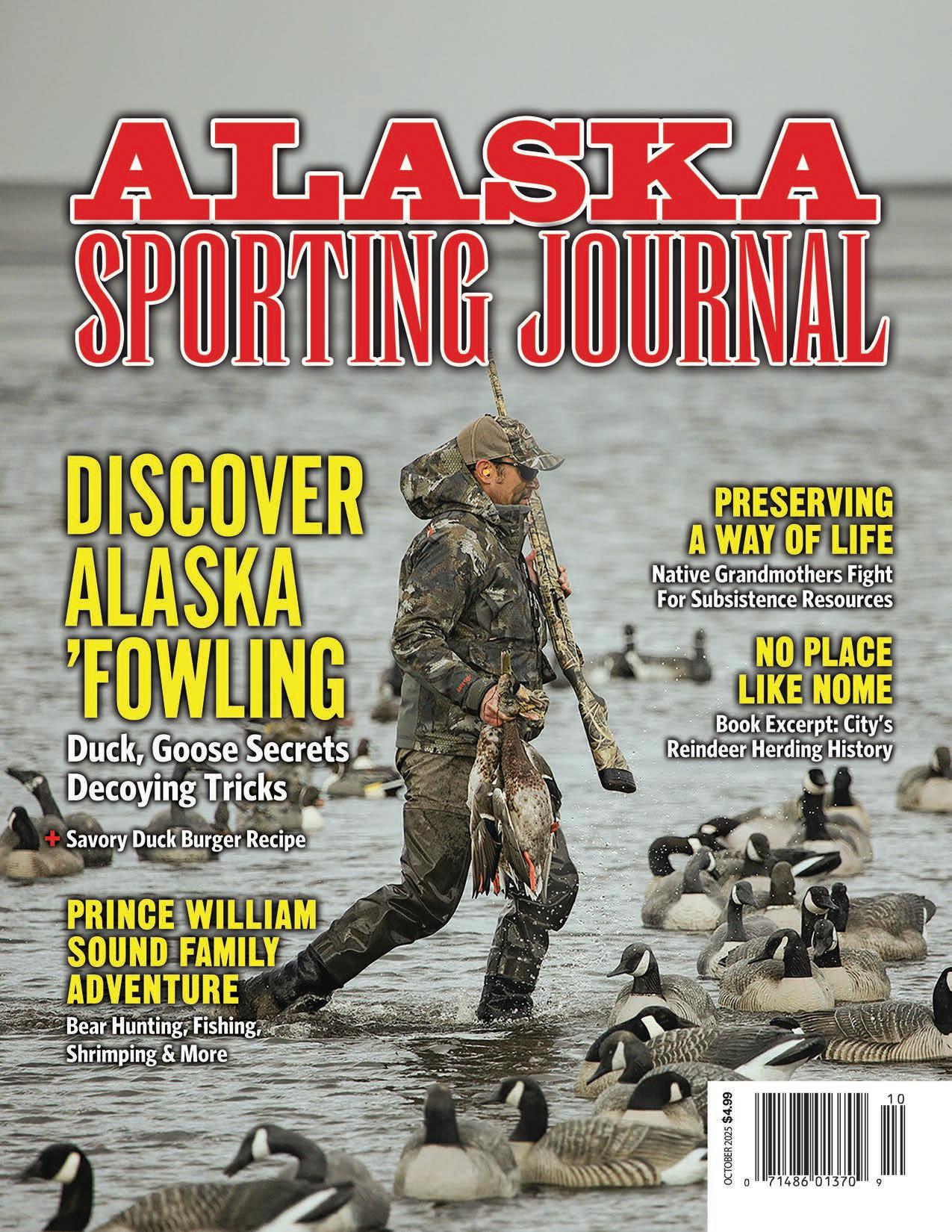

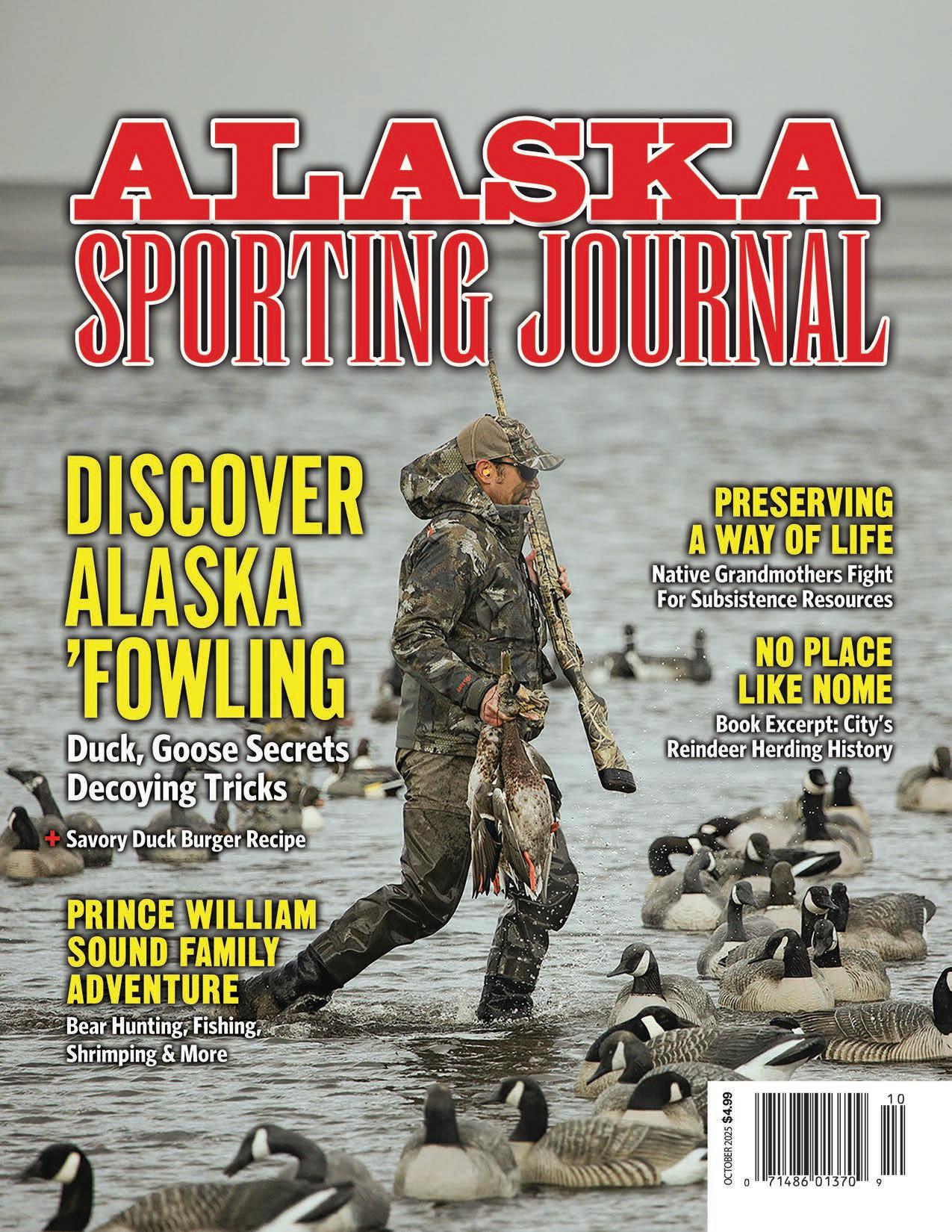

ON THE COVER

Some of Alaska’s most underrated fall hunting happens during waterfowl seasons held throughout the state. “With some basic gear and a desire to learn,” writes Scott Haugen (page 50), “you’re on the way to discovering just how fun early-season waterfowl hunting can be in Alaska.” (SCOTT HAUGEN)

CORRESPONDENCE X @AKSportJourn Facebook.com/alaskasportingjournal aksportingjournal.com Email ccocoles@media-inc.com

Landon Albertson, his wife Jen and their sons Leo, Caleb and Fisher love to explore Prince William Sound, where they’ll hunt, fish and drop shrimp pots. Last spring, along with reeling in rockfish and lingcod and pulling up some delicious crustaceans for fresh seafood meals, the Albertsons were looking to harvest a couple of bruins. Landon recaps the family’s big adventure.

18

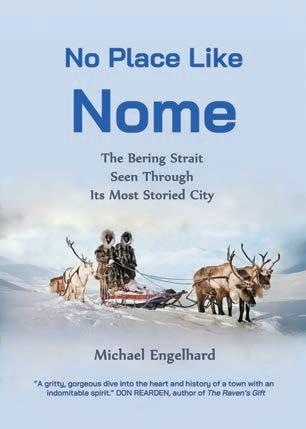

Isolated, cold and a punching bag for parody and puns, Western Alaska’s Nome is in many ways a quintessential Alaska outpost, a community with a colorful, intriguing and at times tragic backstory. Author Michael Engelhard once lived there, and his latest book, No Place Like Nome, shares stories of this remarkable, unique town. Along with our interview with Engelhard, check out an excerpt from his book that recalls a gold rush-era shortage of caribou and those who compensated by herding reindeer on the tundra.

Editor’s Note: Savoring Fat Bear Week contest winner

As Outsiders from Washington, DC, covet opening large swaths of protected Alaska public lands for drilling for natural gas, many who have lived on these same areas and sustained themselves via their natural resources are not giving up the fight to preserve that way of life. Iñupiat Rosemary Ahtuangaruak, who hunts and harvests on the North Slope, leads the organization Grandmothers Growing Goodness, which won’t back down with so much at stake for themselves, future generations and fish and wildlife. Tiffany Herrington profiles Ahtuangaruak and her cause.

If you always wanted to get out onto a Last Frontier marsh or tidal flat and hunt early-season ducks and geese but were a bit intimidated by the logistics, Scott Haugen makes a compelling argument how even newbies can give this a try with some research and safety common sense. You won’t need fancy apparel, expensive decoys or a new shotgun. “With some basic gear and a desire to learn, you’re on the way to discovering just how fun early-season waterfowl hunting can be in Alaska,” writes Haugen.

The editor went all-in on voting for perennial-contender-but-always-coming-up-short bear 32 “Chunk” for this year’s Katmai National Park Fat Bear Week contest. Voters agreed and Chunk won the crown as beefiest of the big-boned bears for 2025. (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE)

Each spring marks a rite of passage for me as a college basketball fan. That’s when I, like millions of other weirdos, fill out a bracket predicting that year’s NCAA Tournament games. It’s a wild, three-week circus known as March Madness.

I’ve won a few office pools and when competing with my buddies, but more often than not I end up with that sickness known as bracket busted syndrome. That’s when the tournament’s unpredictably of upsets and unexpected results all but torpedo your chances to win. And here I watch enough of the game to think I know what I’m doing! Fat chance.

Speaking of fat, now I have another bracket addiction annually in September – Katmai National Park and Preserve’s Fat Bear Week contest, which sees fans make their choice for the park’s most impressively bulky brownie.

And seeing these majestic animals transform from skinny and athletic to stuffed and big-boned to prepare for winter’s hibernation has attracted thousands of like-minded voters rooting for their favorite. Unlike how cruel the basketball picks can be, there are really no losers here when making these picks.

“The astonishing salmon runs in Katmai are essential to the survival of the park’s ecosystem and brown bears,” Katmai National Park Superintendent Mark Sturm says of the event. “Fat Bear Week enables people from around the world to actively engage in learning about bears while cheering for their favorite competitor.”

As I looked at this year’s bracket, my favorite bruin was bear 32, affectionately known as “Chunk.” He’s been runner-up in this event now three times in the decade, and if I can make a college

basketball comparison, he’s the Fat Bear Week equivalent of the University of Houston Cougars, a program that’s won big in multiple eras with some of the greatest players of all time, but they always seems to come up short of winning it all, including the most recent tournament in a bitterly close loss to Florida in this April’s national championship game.

Chunk had become a polarizing bear in the contest, given the subplot of killing the cub of his 2024 Fat Bear Week sow competitor, 128 “Grazer,” who’d won the previous title – also beating out Chunk. Grazer repeated as princess of plump last year by outpacing the always-the-bridesmaid, never-the-bride Chunk by about 40,000 votes.

As I started voting in 2025’s contest, I kept wondering if this would be Chunk’s year. Like any good athlete, Chunk was playing through the pain. “Chunk returned to Brooks River in June 2025 with a freshly broken jaw,” noted his Fat Bear Week bio. “The timing of the injury during the brown bear mating season and the nature of it strongly suggest that Chunk was injured in a fight with another bear.”

I was all-in on Team Chunk as I voted throughout the competition, and other bracketologists agreed. As he cruised into the finals and faced off with an upstart contender, bear 856 (that bruin needs a nickname too!), Chunk completed his redemption tour, earning 96,350 votes (856 was just over 32,000 behind in the final tally).

Whether it’s basketball or bears, I love a good bracket contest, and we appreciate a comeback story like Chunk’s. Enjoy your victory, buddy. Sleep well. -Chris Cocoles

Removal of Roadless Rule protections would affect some of the Tongass National Forest’s pristine habitat. “The Tongass is where America comes to see Alaska. More than two million people come to see wildness, brown bears, glaciers, wild salmon and big, beautiful public land,” says SalmonState’s Southeast Alaska program manager Dan Kirkwood. (DON MACDOUGALL/USFS)

Besides the fight to keep the Pebble Mine out of Bristol Bay’s pristine salmonspawning watersheds, the Tongass National Forest is the battleground capital of Alaska’s tug-of-war to preserve or develop the state’s remaining natural wonders.

Now in his second term in the White House, President Donald Trump and his administration have longed to repeal the Roadless Rule. Because of the 2001 rule’s safeguards on inventoried roadless areas, about half of the West Virginia-sized Tongass – which is 17 million acres of lush forests and anadromous fish habitat – has been off-limits from large-scale commercial logging and other projects.

But in late August, Trump’s Interior Department announced its intentions to remove Roadless Rule protections, potentially affecting at least 45 million acres of national forest land across America, including large portions of both the Tongass and Chugach National Forests in Southcentral Alaska.

“For nearly 25 years, the Roadless Rule has frustrated land managers and served as a barrier to action – prohibiting road construction, which has limited wildfire suppression and active forest management,” US Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz said in an Interior statement. “The forests we know today are not the same as the forests of 2001. They are dangerously overstocked and increasingly threatened by drought, mortality, insect-borne disease and wildfire. It’s time to return land management decisions where they belong – with local Forest Service experts who best understand their forests and communities.”

Opponents expect the Trump Administration to run roughshod on the land by making its plentiful timber available for logging and other moneymaking opportunities.

“Alaska’s roadless areas are essential public lands that the Forest Service should not open up to roads and development. Our national forests still have trees older than the United States, healthy salmon populations and true backcountry,” said Dyani Chapman, Alaska Environment research and policy center state director.

“Roadless areas make up beloved hunting grounds, fly fishing areas and hiking opportunities. It is more important to protect these areas than to get a little more wood or to build one more mine or one more road. The Roadless Rule is a successful conservation tool, and it should stay in place,” she added.

Two Southeast Alaska outdoor recreation business owners, Dan Blanchard of Uncruise Adventures and Hunter McIntosh of The Boat Company, both cited the need to keep the lands they share with customers undisturbed from development that’s sure to change the Tongass forever.

Added SalmonState Southeast Alaska program manager Dan Kirkwood, “The Tongass is where America comes to see Alaska. More than two million people come to see wildness, brown bears, glaciers, wild salmon and big, beautiful public land. The Forest Service and Southeast Alaska needs to focus on managing tourism so locals can make a living here and we can keep what makes Alaska awesome.”

And we’ll see how long that lasts.

We can’t think of a better way for a couple’s wedding nuptials to take place than on Bristol Bay’s famed Nushagak River, courtesy of our friends at Nushagak River Adventures (fishthenush.com).

The Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center and the Alaska State Fair teamed up to feed vegetables from the festivities to hungry bears. Bon appétit, bruins!

15.32, 264.8

Weights, respectively, for Valdez Silver Salmon (caught by Jager Thurmond) and Halibut (Lloyd Fanter) Derbies’ winning fish.

THEY SAID IT

“ ”

“My favorite thing to do is

watch everybody else.

I was supposed to be running the boat and everyone else was eating sandwiches and I just happened to grab the pole. I just got lucky.”

Derbies on his winning coho salmon that earned him $11,500 in cash prizes.

When he was a college athlete at Cisco College in Texas, Gary Morris was thinking about Alaska.

“I had friends who went up there when they were 19 years old and worked on the pipeline,” he says. “And I was in college playing ball and thought, ‘Damn, I’d really like to go.’”

Except he didn’t go for years, not until long after he became a successful performer. It was worth the wait when he made his first trip in the 1980s.

Morris flew into Cordova, in Southcentral Alaska. There he met famed hunting guide Sam Fejes, who took Morris on a memorable six-day grizzly hunt.

They put in a lot of miles, staying in a tent camp and eating meals cooked over an old WhisperLite stove. The simplicity of the moment had a lasting effect on Morris. He never got the grizzly he was after, but did harvest a black bear on a spot-and-stalk longbow hunt, “which was kind of cool.”

“I’ve always said that what Alaska offers is, there are a million ways to live and a million ways to die, and they’re all in Alaska,” Morris says.

There were plenty of other adventures in the Last Frontier. In the 1990s, he hosted an outdoors show, The North American Sportsman, on the Nashville Network. His guests on Alaska-filmed episodes included actors Ed Marinaro and Wilford Brimley. The latter fished with Morris in the Brooks Range, where they shared the river with grizzlies.

“I’ve brought a bunch of other people up there. I’ve been in floatplanes when that migrating caribou herd was out,” Morris says. “When I hunted with Sam, we went to the lodge one day and we were in two tents in the middle of it. There were grizzly tracks around our tent after we were out all day. When we came in, we said, ‘Well, look what’s been here.’” -Chris Cocoles

Multiple Alaska moose seasons open this month, including two in the Anchorage area (October 15 in the Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson Management Area, and October 25 around the Ship Creek drainage). (LISA HUPP/USFWS)

Oct. 1 Goat season opens in Game Management Unit 1C (Southeast Mainland; area draining into Lynn Canal and Stephens Passage between Antler River and Eagle Glacier/River)

Oct. 1 Deer season opens in GMU 3 (Petersburg Management Area and, for residents only, remainder of Mitkof, Woewodski and Butterworth Islands)

Oct. 1 Elk season opens in GMU 3 (Etolin Island)

Oct. 1 Moose season opens in GMU 5 (Yakutat in area east of Dangerous River and Harlequin Lake)

Oct. 1 Deer season opens in GMU 6 (North Gulf Coast and Prince William Sound)

Oct. 1 Elk season opens in GMU 8 (Raspberry Island)

Oct. 1 Deer season opens in GMU 8 (Kodiak Island, areas not including the Kodiak Road System Management Unit)

Oct. 1 Brown bear season opens in GMU 9 (Alaska Peninsula)

Oct. 1 Black bear season opens in GMU 14C (McHugh Island)

Oct. 1 Brown bear season opens in GMU 14C (McHugh Creek drainage)

Oct. 7 Goat season opens in GMU 6C (North Gulf Coast and Prince William Sound)

Oct. 8 Elk season opens in GMU 8 (Southwest Afognak, that portion of Afognak Island and adjacent islands)

Oct. 11 Second elk season opens in GMU 8 (Raspberry Island)

Oct. 15 Nonresident deer season opens in GMU 3 (remainder of Mitkof, Woewodski and Butterworth Islands)

Oct. 15 Youth deer hunt opens in GMU 5

Oct. 15 Moose season opens in GMU 5A (west of Dangerous River and Harlequin Lake, and southwest of Russell and Nunatak Fjords and the East Nunatak Glacier)

Oct. 15 Brown bear season opens in GMU 6D (Montague Island)

Oct. 15 Moose season opens in GMU 14C (Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson Management Area)

Oct. 16 Second/alternate elk season opens in GMU 3

Oct. 23 Elk season opens in GMU 8 (Southwest Afognak and additional areas)

Oct. 23 Third elk season opens in GMU 8 (Raspberry Island)

Oct. 25 Brown bear season opens in GMU 8 (Kodiak/Shelikof)

Oct. 25 Moose season opens in GMU 14C (Ship Creek drainage above Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson Management Area)

For more information and season dates for Alaska hunts, go to adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=hunting.main.

Tucked away in Moclips, Washington, on a 125-foot clifftop where the forest meets the sea, sits Ocean Crest Resort – your new favorite spot for some much needed R&R&R. No, that third R isn’t a typo, it’s Washington’s best-kept secret.

Rest: You’ll feel well rested having drifted off to the dull roar of the Pacific, the soft patter of rain, or the quiet murmur of the movie you rented from the front desk.

Relaxation: You’re sure to be relaxed after lounging at Cedar Serenity Spa, the resort’s pool, hot tub and cedar dry sauna.

Recreation: You’ve never had a vacation like this, because Ocean Crest Resort is the ideal launchpad for any adventure, no matter what suits your fancy.

Fun is just footsteps away when you descend the resort’s staircase to Mocrocks Beach for surf fishing, clam digging, beachcombing and birdwatching. Adventure a little further to take advantage of the Olympic Peninsula’s best spots for game hunting, fishing, hiking and trail biking, all less than a 45-minute drive away. With 43 units ranging from retro and rustic to renovated and refined, you’ll have no problem finding the perfect spot to land, be it a standard studio or a large two-bedroom flat for the whole family. How about an adventure for your palate? The dining room at Ocean Crest Resort sources the finest, freshest spoils of the Pacific Northwest and prepares them with global flair, leading to unique dishes that are flavorful and refined, yet unpretentious and exciting. The restaurant truly is a love letter to the region, pouring only beers local to Grays Harbor and maintaining an expansive wine catalog sourced exclusively from the Pacific Northwest.

No matter what kind of adventure you’re looking for, you’ll be impressed by all Ocean Crest Resort has to offer.

www.oceancrestresort.com | 360-276-4465

From Nome’s Front Street after a winter storm to Bering Land Bridge National Preserve erupting with color during the short fall season, this famed city on the Bering Sea also has quite the backstory, which author (and former Nomeite) Michael Engelhard details in his new book about the city’s and region’s culture and history. (JILL HOMER; KATIE CULLEN/NATIONAL PARK SERVICE)

Mention Alaska and your first thought might be of iconic salmon runs heading up pristine rivers, massive big game animals like bears, moose and caribou sharing the Last Frontier with its people, and perhaps endless summer daylight that describes the “Land of the Midnight Sun.”

And there’s the Western Alaska city of Nome, a tiny, hearty and historical melting pot of a community of just under 4,000 hard on the Bering Sea’s Norton Sound.

Nome is now known for its isolated location, dreary winters and gold dredging vessels made famous by the Discovery Channel series Bering Sea Gold, but it also has a colorful past – both in good and bad ways – that one-time Nomeite and author Michael Engelhard was fascinated by.

“In truth, Nome’s contrasts at once can jar one and stimulate thought. There is racism, poverty, femicide, domestic and substance abuse. There is laughter, beauty, resilience, and vibrancy, too,” Engelhard writes in a new book that captures whatever perception you might have about this quintessential Western Alaska town.

Trained as an anthropologist with a degree from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Engelhard worked for 25 years as a wilderness guide and as an outdoor instructor. His books include the National Outdoor Book Award-winning memoir Arctic Traverse (see our August 2024 issue), the cultural history memoir Ice Bear, and the essay collection he’s published now that discusses, among other things, how dwindling caribou herds around the turn of the 19th to 20th century made reindeer herding big business, even amid Nome’s gold rush heyday chaos.

The following is excerpted from No Place Like Nome: The Bering Strait Seen Through Its Most Storied City, by Michael Engelhard and published by Corax Books.

BY MICHAEL ENGELHARD

“THE

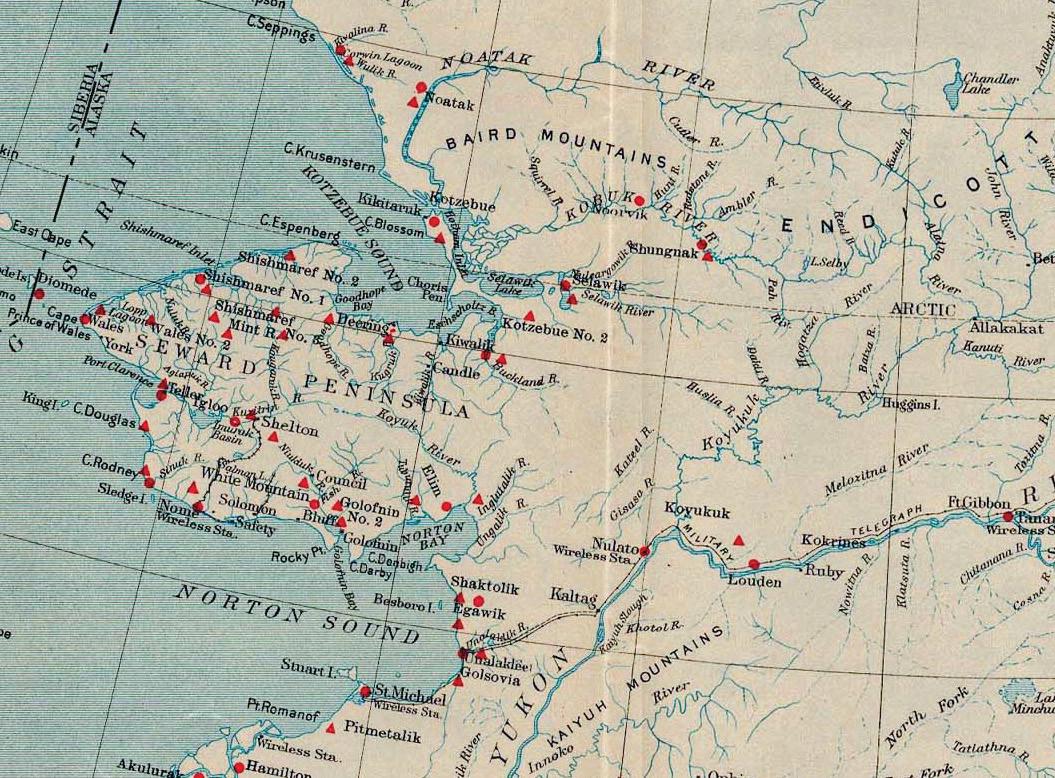

In July 1897, among a sales ad for walrus heads and news of the discovery of antique Eskimo armor made from iron slats, the following appeared in The Eskimo Bulletin: “The success attending this year of the mission herd of domestic reindeer at the Cape [Prince of Wales] speaks well for the faithfulness and skill of our Eskimo herders, all of whom are Christians. Each of them has driven more than 500 miles during the winter.”

The author and publisher was William Thomas Lopp, teacher at the Congregational mission and, briefly, superintendent of the Teller Reindeer Station. The wintertime long-distance reindeer driving had been done entirely in reindeer-drawn sleds with the driver balanced on the runners, dog sled-style.

Only five years before, on Independence Day, the Teller Reindeer Station had been established, with flag raising, cheering and 53 Siberian reindeer landed at Port Clarence, the only sheltered port on the Bering Strait coast. This breeding stock laid the foundation for a total of 640,000 reindeer on the Seward Peninsula and would shape the welfare and livelihoods of its Alaska Native residents for the next 40 years.

BY THE END OF the 19th century, commercial hunting had depleted the region’s whale, walrus and caribou populations, and starvation haunted the coastal Iñupiat. Following his belief that “God blesses aggressiveness,” the Presbyterian Reverend Sheldon Jackson – Alaska’s General Agent of Education – had made five trips to Siberia in 1892 and imported 171 reindeer to aid Western Alaska’s Native residents. Four Chukchi Siberian men accompanying the initial shipment were employed as herding instructors. Iñupiat traveled from hundreds of miles away to determine what the white men at Teller were up to.

Jackson used herding as a means for teaching Alaska Natives of both sexes modern domestic skills, English and math, so they could do business with whites. But Jackson had another agenda: Manifest Destiny. Not only would reindeer turn hunters into herders, he thought, but also “utilize hundreds of thousands of square miles of moss-covered tundra ... and make these now useless and barren wastes conducive to the wealth and prosperity of the United States.”

For ages, however, this “barren waste” had meant security to people who were not ranchers, miners, or farmers. Their

crops were the North Country’s wild animals. “Any time that we wanted an ‘apple,’” said Iñupiaq leader Eben Hopson from Barrow, “we went out and got it. We got what we wanted to live on, got what we needed.” But the locals fastlearned the new economy. “The deer is like money,” one herder observed.

Selected by the mission teachers, Iñupiaq “apprentices” (boys or men) got five years of schooling, together with room and board. The first year, an apprentice earned two of the reindeer in his care, the second year five and the third year 10. After five years, a herder was loaned enough reindeer to increase his herd to 50 animals.

From the beginning, tensions flared between the missionaries and the Chukchi, who when thirsty, lassoed a reindeer doe to drink directly from her teats,

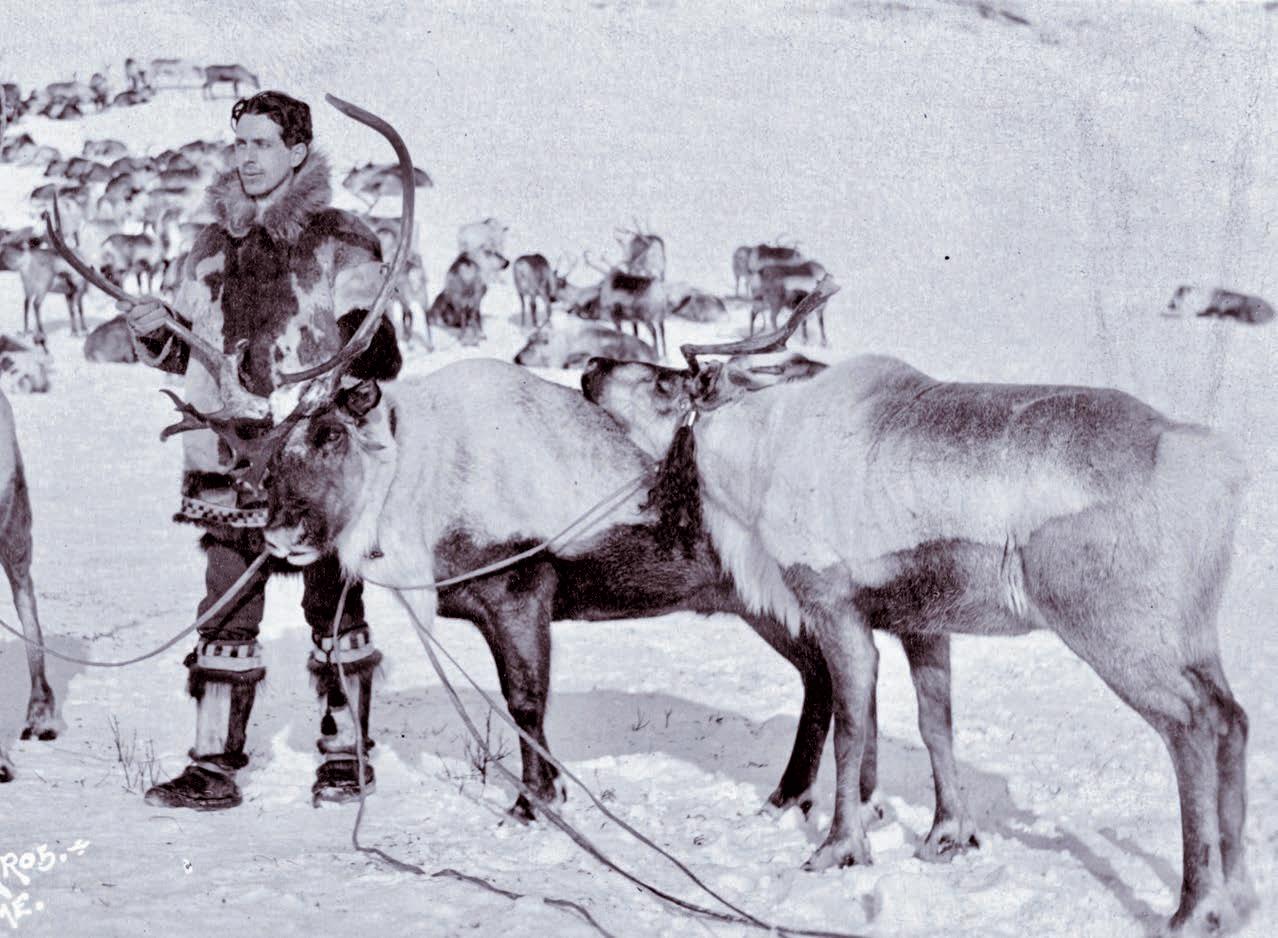

Carl Lomen with draft reindeer – animals trained and used to pull heavy loads – near Nome. Lomen and his family came to Nome from Minnesota in 1903 to strike it rich amid the city’s gold rush period, and they became loathed by his peers as the need for reindeer meat became more critical. “Eventually, Lomen controlled the prime grazing grounds, charging Eskimo herders a use fee and collecting a herding fee for each Iñupiaq reindeer that got mixed up with his herd,” Engelhard writes. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

“quaffing it with as much enjoyment as if it had been pure nectar.” More offensive to their supervisors was the Siberians’ practice of guiding the salt-loving reindeer by marking the ground with streams of urine. Such behavior, in the eyes of the missionaries, would do nothing to help civilize the local Iñupiat.

In 1894, the missionaries recruited 16 Saami in Lapland to replace the Chukchi as herding instructors. A Christian role-model clause in their contract bound the Saami to behave “orderly and decently and to show discipline.” Each Saami herder received 100 deer for three to five years of service. The local Iñupiat soon warmed to the newcomers, calling them the “Card People,” because their traditional Four Winds hats reminded the Iñupiat of kings’ and jacks’ headgear on playing cards. The Iñupiat herd-

During the 1960s, Alaska Native owners were selected to become private reindeer herders with designated ranges. In 1968, the Bureau of Indian Affairs took over range management by issuing grazing permits and monitoring range conditions. Soon after, modern range management techniques, in part developed with the University of Alaska, Fairbanks Reindeer Research Program, were applied to herding. With passage of the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, Alaska Natives were drawn deeper into free enterprise, and several regional and village corporations sought to revitalize reindeer herding as viable economic ventures.

Currently, there are approximately 20 reindeer herders and 20,000 reindeer in Western Alaska. These herders belong to the Reindeer Herders Association, part of the Kawerak, Inc. Natural Resources Division. This group provides assistance with improving herd management and developing a viable reindeer industry to enhance the economic base for rural Alaska.

Some modern herders use satellite collars to locate their herd, and at summer roundups near Teller a helicopter – hovering 8 feet above the ground – helps funnel reindeer into corrals. The pilot is Donald Olson (Iñupiaq), a medical doctor, Alaska state senator, and also the great-grandson of one of the original Saami herders. Nowadays, the most lucrative reindeer product is velvet from the new antlers, a homegrown Viagra for Asian markets. ME

Alaska Sporting Journal editor

Chris Cocoles caught up with No Place Like Nome author Michael Engelhard on what makes this community such a “storied” city.

Chris Cocoles Congratulations on this latest book, Michael. What was your inspiration for writing about Nome?

Michael Engelhard I lived for three years in Nome, and as the book’s subtitle says, it is the most storied city I’ve ever lived in. Positioned at a crossroads of continents and cultures – North America and Asia, Anglo and Iñupiaq – it is rich in characters and history dating back at least 15,000 years, when people traveled there from Beringia, the land bridge now submerged. Over the years, I’ve written articles about Nome and the Bering Strait for various magazines and, realizing that there was much more material waiting to be explored, I decided to more fully portrait the town and region.

CC What an historic, fascinating, complicated, if not at times tragic, backstory Nome has. Can you put into words what the research was like for you working on this book?

“It can seem forlorn on overcast days, with the gray sea as backdrop and the wind howling … Being without big-city amenities might also get to people,” says No Place Like Nome author Michael Engelhard, who lived in the remote city along the Bering Sea for three years. “You have to live in Nome for a while to see and appreciate its true character and that of its people.” (MELISSA GUY)

ME The book was largely written while I no longer lived in Nome, and with the multitude of facts, checking each one personally was beyond my reach. Plus, frankly, there can be ideological divides in Native communities about conservation versus development, for example; the same as in any society, really. Orally transmitted stories are another good example: Different versions usually coexist, so it’s impossible to find the “true” or “official” one. I tried to double-check the correctness of facts, usually from not one but several sources. The University of Alaska Fairbanks’ oral history department has done incredible work interviewing elders and recording them, and I used those archives, plus visual sources (old photos, film clips, etc.).

CC Probably the first time I ever heard about Nome was the movie Stripes, when the obnoxious Army Captain Stillman gets banished to a command in Nome. Do you think that’s the perception people have for Nome – that it’s a dreary place you don’t want to end up in?

ME

That may be the case. It doesn’t have the scenic values of, say, the Alaska Range. It’s a more subtle beauty of tundra and rolling hills – though they have the Kigluaik Mountains near town, a 48mile miniature Brooks Range of peaks up to 4,714 feet above sea level. Some people rock-climb there. It can seem forlorn on overcast days, with the gray sea as backdrop and the wind howling. And it is almost always blowing. Being without big-city amenities might also get to people. You have to live in Nome for a while to see and appreciate its true character and that of its people.

CC As you describe in the book, gold is a huge part of Nome’s identity. Can you explain a little bit about that connection?

ME In 1899, after the gold fields in the Yukon’s Klondike had all been claimed or exhausted, the “Three Lucky Swedes” (one of them was actually Norwegian) struck it rich on Anvil Creek. The town originally was called Anvil City, after a rock outcrop on a nearby mountain. So, the action then shifted to Nome, which could be reached much easier, by steamer, rather than over the arduous Chilkoot Pass from Skagway or up the Yukon River from its mouth at St. Michael. Some Sourdoughs in Dawson even hit the trail on bikes and rode on the frozen Yukon River all the way to Norton Sound that first spring. Even latecomers still had a chance to make money from the “Poor Man’s Diggings” – Nome’s beaches, which hold gold-bearing sands and could not be claimed individually. That’s where also much of that current reality TV show takes place – Bering Sea Gold – on the beach and offshore, where amateur miners on pontoon boats dredge up the ocean floor and sift it mechanically.

CC The other component that defines the city is dog sledding, including the Iditarod connections. How important have these remarkable working dogs and their mushers been to the people there?

ME There are no more “working dogs,” per se, in the region, but Nome definitely remains a dog town. The Iditarod brings in big revenues from tourists and journalists who come to watch the finishers on Front Street. But the race has lost some of its luster. Many of its sponsors are now corporate or backing out over allegations

of animal cruelty; the race start last year was moved to Fairbanks, north for the fourth time, since Southcentral Alaska snow at its start was in short supply again; and most Nome mushers no longer exercise teams on the Iditarod Trail for fear of getting hit by a snowmachine.

CC Alaskans are known for their toughness, but does a Nomeite have to be even more resilient than a typical resident of the Last Frontier?

ME I don’t think they are tougher than rural Alaskans elsewhere (though they might like to believe so). They are just facing challenges that differ from those in other places; many of those are logistical. All fuel, heavy equipment, construction material and trucks have to be barged in during the summer, for example, and storms can delay those shipments. The town also experiences some pretty serious flooding during storms, and blizzards that create rock-hard snowdrifts, which bury roads. The Native cultures, before first contact, however, had adapted to this harsh environment. As people sometimes pointed out to me, their ancestors really were tough.

CC What’s the fishing and hunting scene like in Nome?

ME The fishing is good, though not by Southcentral Alaska standards. There are salmon and Dolly Varden at the mouth of the Nome River, and some starry flounders. But it’s, of course, best known for its crabbing; Bering Strait king crab is simply to die for. The hunting isn’t the best. Not a lot of cover for moose, and bears and caribou are scarce in the area. (Perhaps still from overhunting during the first gold rush and commercial whaling times?) On the other hand, you can see muskoxen right in town, sometimes near the Alaska Commercial Company store, where they play “King of the Hill.” You can also see them grazing right by the runway while planes take off. I think they may hide from prowling grizzlies in town, somehow knowing that they can’t be hunted within city limits. Beyond those, it’s a different game, and you can see muskox skins drying on people’s porches.

CC You did a deep dive into some of Nome’s most interesting personalities like wildlife

author Sally Carrighar, photographer E.S. Curtis and missionary/reindeer herder William Thomas Lopp. Did they really help you understand the soul of Nome? ME I think so. It is vital to link the past with the present. The two are not sovereign countries; we have one foot in each. History first and foremost is storytelling, and the stories of these famous individuals (and a score of lesser-known ones) helped me to understand patterns. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “All history becomes subjective … there is properly no history, only biography.” The fable of the elephant and the blind men, in my opinion, gets it wrong: A bigger understanding does hide in the sum of smaller ones; in this case, individual lives.

CC What’s one very overlooked component of Nome that we should all know about?

ME If anything, I’d like readers to acknowledge that this is not an American backwater and never has been, and that history there reaches so much deeper than the 1899 gold rush, when “Anvil City,” as Nome was then called, was founded. With the newly developing geopolitical situation and the Northwest Passage now largely ice free, Nome and the Bering Strait might well become hot spots again, as they were during the Cold War and even during the Russian period.

CC Is there an only-in-Nome story that stands out to you from writing the book? ME There are so many. Stories nest within stories there, like Russian dolls. But here are some glimpses that for me perfectly capture the spirit of Nome: On a cold, stormy early summer day, I was beach walking with my wife. Some Iñupiat kids were out swimming and frolicking like sleek seals, amid bergy bits of sea ice. During the 2011 “blizzicane,” I saw kids riding BMX bikes into rough surf. I really admire that kind of spirit and hardiness. Nomeites have strange customs, too. After Christmas, people put their trees out on the sea ice (when there is any) and call that the “Nome National Forest.” (The town is surrounded by treeless tundra, which feels more arctic than subarctic, culturally and biologically, though it lies at roughly the same latitude as Fairbanks.) CC

Saami

ers-in-training were less happy with their subordinate status, the monotony of the work compared to fishing and hunting, and the lack of immediate payback.

THE WINDS OF OPPORTUNITY blew a family into Nome that would become its richest, shrewd promoters of reindeer meat as well as the Christmas holiday, especially Santa and his sleigh. In 1903, Carl Lomen and his father, Judge Gudbrand J. Lomen of St. Paul, Minnesota, moved to Nome after a working vacation there at the height of its gold craze. Carl’s mother,

four brothers and one sister soon followed. Lomen senior hoped to profit from disputed mining claims but ended up forging a corporation with several backers: Lomen & Company.

Carl’s first encounter with reindeer paints a rather citified picture of him. Wandering the tundra near Nome in the summer of 1900, he came upon a herd and froze in his tracks. He was ignorant of reindeer habits and feared they might attack.

Conflict over the best rangelands soon mounted. Eventually, Lomen

Changunak

controlled the prime grazing grounds, charging Eskimo herders a use fee and collecting a herding fee for each Iñupiaq reindeer that got mixed up with his herd. While the Lomens hired Native herders and bought their excess steers, these were largely token gestures. Still, with breeding stock from firmly established mission herds, new reindeer stations sprung up in Iliamna, Barrow, Kivalina, Nulato and as far inland as Bettles.

Some Iñupiaq herders benefitted, if only temporarily. One of them was “Sinrock Mary,” born in 1870 to a Russian trader and an Iñupiaq mother as Changunak, who would become trilingual and eventually accompany Healy and Jackson, sometimes to Siberia, working as a linguist and interpreter. She would later become known as the “Reindeer Queen of Alaska.” Raised in St. Michael, she married the Teller Iñupiaq herder Charles Antisarlook in 1889, and the couple moved to Cape Nome. Charles had already built his own modest herd, the first to be owned by an Alaska Native. When he died from measles in 1900, Mary fought and succeeded in keeping her half of the herd. She started to sell meat to local businesses and the Army station. Her second husband was not interested in reindeer, so Mary adopted 11 children, some of which had been orphaned by the epidemics. She trained them and other Iñupiat to become “deer men,” and soon they ran herds of their own.

At one point, “Queen Mary’s” herd

At Krog’s Kamp, their mission is to craft an unforgettable Alaskan adventure where your every moment is steeped in comfort, excitement and personalized care. Nestled along the scenic banks of the world-renowned Kenai River, Krog’s Kamp offers more than just a place to stay — it’s a launching point for extraordinary experiences.

From the moment you arrive, you’re welcomed as part of the Krog’s Kamp family. Each day promises a new thrill — from epic fishing trips and wildlife encounters to evenings spent sharing stories under the stars around a crackling campfire. Guests enjoy comfortable lodging options, including cozy one-bedroom cabins and spacious two-bedroom chalets, each featuring private baths, gas grills, TVs and free WiFi. The main house offers satellite TV

and fax services, perfect for staying connected if needed.

You’ll also have access to a large hot tub, a relaxing sauna and private river frontage — ideal for both guided and unguided fishing. Their all-inclusive packages feature lodging, high-quality gear and exciting guided charters led by licensed captains, along with private riverbank access for those who prefer to cast a line solo.

They proudly welcome fishing groups, families, solo adventurers and even corporate teams seeking a unique getaway. With warm hospitality, a focus on every detail and a backdrop of breathtaking natural beauty, Krog’s Kamp delivers a level of service and adventure that not only meets expectations — it exceeds them.

Space is limited during the short fishing season – book early to secure your dates!

was the largest in the North, but she kept living simply fishing, gathering berries and greens, and preparing skins for sewing. A Swedish schemer claimed to be her third husband in an attempt to disown her. Changunak had long witnessed the effects of disease and unlawfulness upon her people. Miners staked claims inside grazing ranges,

and reindeer were lost to rustling.

Clearing claims by burning the tundra’s vegetation deprived reindeer and caribou of forage. In addition to encroachment upon Native hunting and fishing grounds, new diseases preyed upon people – smallpox, influenza and measles. Over half of the Native population in Northwestern Alaska had died by the end of 1900, a mere two years after the mad rush for gold had begun. ASJ

Editor’s note: You can buy the book on amazon. com/No-Place-Like-Nome-Through/dp/ B0DX4ZGLJT or at your local bookstore. For more on author Michael Engelhard’s other books, check out michaelengelhard.com.

Visit Oregon’s Year-Round Escape in the Cascade Mountains!

An excellent venue for retreats, team-building activities, weddings, and family reunions, Odell Lake Lodge & Resort offers cozy cabins, delicious food, boat and slip rentals, and a newly designed 18-hole disc golf course. It’s the perfect place to gather, connect, and create lasting memories in a stunning natural setting. Enjoy fishing, hiking, and camping in the summer, or snowmobiling, cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and fireside relaxation in the winter. This Fall, take advantage of the brand new sauna at lakeside as part of your adventures! Experience over a century of mountain magic—any season, every reason.

BY TIFFANY HERRINGTON

When Rosemary Ahtuangaruak talks about the Arctic, she doesn’t sound like a lobbyist or a policy wonk. She sounds like someone who has spent her life on the tundra, listening to elders, raising children, cutting fish at camp and watching the land change beneath her feet. Her words are not abstract; they are rooted in lived experience, in cultural continuity, in health and survival.

“We are not the sacrifice for the national energy policy,” she says.

Ahtuangaruak, the founder and executive director of Grandmothers Growing Goodness, or GGG, has become one of the most prominent Indigenous voices fighting to protect the Western Arctic and the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska (NPR-A) from expanded oil and gas drilling. From her home in Nuiqsut, a small Iñupiat village on Alaska’s North Slope, she has carried local concerns

into boardrooms, federal hearings and congressional offices. Her group has played a central role in opposing the Trump Administration’s efforts to open millions of acres of the NPR-A to leasing, a campaign that has pitted subsistence traditions against energy politics in one of the most ecologically rich regions in the world.

Ahtuangaruak was born in Fairbanks but raised in a world where food was culture, connection and survival. “We always had our foods,” she recalls. “We would get boxes and coolers, prepare them, and always have family over to share when the boxes came in.”

With the food came stories, games and laughter – until her father walked in, and Iñupiat language was silenced by assimilationist pressure.

She remembers the elders of

Nuiqsut pulling her aside, urging her to carry more than medical knowledge into the spaces of decision-making. “They told me, ‘We like that you go to the meetings and talk about life, health and safety, but we also want you to talk about the importance of tradition and culture.’”

That moment changed her trajectory. She was not originally from Nuiqsut –she had married into the village – but the elders made it clear they needed her voice. So she listened.

Her stories flow back to the seasonal games, hundreds of them, played at Christmas and designed to teach strength, agility and endurance for Arctic life: skills for hunting, ice travel and tundra hiking. “The games teach agility for hunting, the strength to hunt the mighty animals that feed our families, and the sharing that binds the generations in the bounty of our lands and waters,” she says.

Harvesting salmon and other fish at camp has been a huge part of Ahtuangaruak’s life, even when she was growing up in Fairbanks before marrying into a small, tight-knit Iñupiat community of Nuiqsut on the North Slope. (GRANDMOTHERS GROWING GOODNESS)

Driven by a desire to care for her community, Ahtuangaruak trained as a physician assistant through the University of Washington’s Medex Northwest program. She served as a community health aide for years, often working long shifts under difficult conditions.

Her commitment to health led her into leadership. She was elected mayor of Nuiqsut, a role she never sought for prestige but for responsibility. Then crisis struck. In 2022, the CD1 gas blowout occurred just 8 miles from the village.

“The industry evacuated personnel in front of our village,” she remembers. “That took a long time to deal with, and honestly, I am still worried there are problems from the blowout affecting development.”

The incident highlighted the risks her community faces living in the shadow of oil development. She couldn’t be home for her reelection campaign and chose

not to run again. Instead, she founded Grandmothers Growing Goodness.

“GGG allows me to share the work I do with others so they can learn before they must do this work,” she says.

The idea behind GGG is simple but powerful: prepare the next generation. The organization works to mentor youth, educate policymakers and protect subsistence rights. Its mission is framed around three goals:

1. Educate locals and nonlocals about the challenges facing Arctic communities.

2. Mentor the next generation of North Slope leaders.

3. Influence policy at every level to protect health, culture and well-being.

The group has taken young people to fish camp, where they set nets, prepared fish and listened to stories. They’ve traveled to Washington, DC, to meet with lawmakers. They’ve testified at public hearings and filed detailed comments on oil and gas projects.

Every effort is about amplifying voices that might otherwise be ignored. As Ahtuangaruak puts it: “By continuing to be involved, there are many who recognize the effort. There have been invitations to educate decision makers. Educating agency researchers, universities and colleges helps to give a seat. Amplifying the volume of concerns helps decision makers dim the confusion.”

If there is one place that defines GGG’s work, it is the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, part of the NPR-A. The lake and surrounding tundra are home to the Teshekpuk Caribou Herd, vital to local subsistence hunters. The Colville River cliffs host nesting raptors. Nearly 200 species of migratory birds arrive each summer from every continent. Offshore, bowhead whales, belugas and seals sustain coastal communities.

But this abundance is fragile.

“We have threats to 82 percent of the reserve,” Ahtuangaruak warns. “Every acre is open to their onslaught. Teshekpuk Lake, Colville River, Peard Bay, Kasegaluk Lagoon, Pik Dunes – all need protections, as they are all unique and provide different assets. They are special for the village that relies upon them.”

The dangers are not hypothetical. She points to reinjection wells near Umiat, where contamination has already been found in fish. She describes how invasive grasses spread across industrial fields, crowding out plants that caribou prefer. She recalls the endless flaring of natural gas – 80 days straight before the CD1 blowout – sending tons of emissions into the air.

The impacts ripple through everyday life. A helicopter once drove caribou into the water just as her son shot his first animal. The harvest was lost. “He is suffering the social disruption of drug use and is still facing demons from this,” she shares. “Precaution is needed and prevention is key.”

For Ahtuangaruak, subsistence is more than food; it is identity, health and resilience. She remembers trading fish for seal and caribou for salmon; aunties picking berries with grandbabies; elders teaching children to value sharing by giving away a first catch.

“We harvest the seasons, from the fish under the ice to the bowhead whales, beluga, walrus, seals, caribou and plants,” she says. “We share the food amongst our extended family.”

This sharing is not symbolic. It sustains life in villages where storebought food is expensive and often unhealthy. It anchors community bonds. It teaches respect and responsibility.

But every disruption – whether from seismic testing, helicopters, or industrial traffic – chips away at these practices. “Infrastructure and failed maintenance affected fish migrations, and this devastation created social stressors that hit the village and made it very hard,” she says.

To her, protecting subsistence is inseparable from protecting public health. “When you have had to hold those little eyes trying to breathe and they come back again, you keep asking questions,” she says. “You look for answers from elders, CDC, APHA, and elsewhere.”

GGG’s fight doesn’t end at the village boundary. One of the greatest obstacles is simply being heard in decision-making spaces dominated by industry.

“The biggest challenges are getting beyond the North Slope, to Juneau, and to DC. Decisions are being made away from the village that will suffer the reaction, leaving our concerns behind as industry sets many tables without us,” she explains.

Still, she persists. With GGG and partner groups like Sovereign Iñupiat for a Living Arctic and Native Movement (silainuat .org), she has filed comments, given testimony and joined coalitions. Wins have been hard-fought – like the Biden Administration’s 2024 rule establishing new protections in the NPR-A, which GGG celebrated, only to see it targeted for repeal under Trump’s White House.

Perhaps the most hopeful part of GGG’s work is its focus on youth. Fish camps bring dozens of young people to the riverbanks, where they learn to cut fish, listen to stories and gain a sense of belonging. Students have joined her in Washington, DC, seeing firsthand how advocacy connects to their future.

“Students are active in school, and I share in the classrooms and they learn,” she says. “Some have traveled to DC

with GGG already. When they ask what else they can do to help, our work is a rewarding response.”

These moments keep her going. “There are little eyes waiting for your help to breathe without flares,” she says.

Ahtuangaruak dreams of a future where special areas around Nuiqsut are safeguarded from drilling, young hunters don’t have to compete with helicopters or ice roads and subsistence traditions are passed on intact.

“The ability to have areas that do not have oil and gas development, that protect the use for our hunting, fishing, whaling, gathering and other activities … would be very appreciated by us,” she says.

She knows the fight is long, but she also knows it’s necessary. “The future we want or the future they deserve is not the same,” she says. “We want to continue to be Iñupiat in the Arctic, living as our elders taught us, feeding our families as they brought us from our land and waters into the future generations.”

For readers thousands of miles away, the struggle for the Arctic might feel distant. But Ahtuangaruak insists everyone has a role.

“See the migrations, connect to the Arctic, care to comment,” she says.

This area of the North Slope is sacred ground for the Iñupiat people. “We harvest the seasons, from the fish under the ice to the bowhead whales, beluga, walrus, seals, caribou and plants,” Ahtuangaruak says. “We share the food amongst our extended family.” (GRANDMOTHERS GROWING GOODNESS)

GGG encourages the public to submit comments during public input periods on Arctic drilling, donate to local organizations like Grandmothers Growing Goodness, and learn and share stories about the Arctic’s ecological and cultural importance.

Her call is urgent but hopeful. The Arctic is still alive, resilient and worth protecting.

“We want to continue to be Iñupiaq in the Arctic,” she says, “living as our elders taught us, feeding our families with the foods we need, in the places we need them, when we need them to be there. Giving the taste of life, health and safety and the importance of tradition and culture.” ASJ

Editor’s note: For more on Grandmothers Growing Goodness, check out its website (grandmothersgrowinggoodness.org) and follow on Facebook. Tiffany Herrington is a Seattle-area-based writer.

Ahtuangaruak (far left, with EJ Rochon and Lizzie Marie) wants the lands she grew up harvesting on to be preserved so future generations of Alaskans can utilize them. “The ability to have areas that do not have oil and gas development, that protect the use for our hunting, fishing, whaling, gathering and other activities… would be very appreciated by us,” she says. (GRANDMOTHERS GROWING GOODNESS)

The lightest 200-hp four stroke on the market

2.8L displacement and Variable Camshaft Timing give it the best power-to-weight ratio of any 200-hp four stroke

Nearly 120 pounds lighter than our four-stroke V6 F200

Show the water who’s boss with the F200 In-Line Four. Incredibly light, responsive and fuel efficient, it serves up plenty of muscle to handily propel a variety of boats. On top of that, its 50-amp alternator offers the power to add a range of electronics, and its 26-inch mounting centers and compatibility with either mechanical or digital controls give you the flexibility to easily upgrade your outboard or rigging. Experience legendary Yamaha reliability and the freedom of forward thinking, with the F200 In-Line Four. THE F200 IN-LINE FOUR.

The focus of a family trip to Prince William Sound was to fill two black bear tags, but it came with so many bonuses. “It is a wild and stunning place, untouched and rugged, and an ideal setting for anyone who loves the challenge and reward of hunting,” author Landon Albertson writes. (LANDON ALBERTSON)

BY LANDON ALBERTSON

Alaska is home to one of the largest black bear populations in the world, with an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 bruins roaming its vast wilderness. One of the best places to find them is in Prince William Sound, where remote islands and thick coastal forests create the perfect habitat. It is a wild and stunning place, untouched and rugged, and an ideal setting for anyone who loves the challenge and reward of hunting.

In many parts of Alaska, including in and around Prince William Sound, the season runs from late summer until June 30. But spring is one of the best times to chase black bears in the Sound. As they emerge from their winter dens, they begin moving along the beaches and glacier slides in search of easy food. Green grass, ocean mussels and whatever the tide has left behind draw them out into the open, offering solid opportunities for a well-planned stalk.

We decided to make the most of Memorial Day weekend. My wife Jen and I took an extra day off work and loaded up the boat with our kids – Leo, Caleb and our youngest, Fisher. Our goal was simple. We planned to hunt bears, drop shrimp pots, catch some fish and – most of all – enjoy quality time together in one of the most beautiful places Alaska has to offer.

For our family, the experience goes beyond the hunt. We do it with purpose. We use everything the animal provides and follow the laws in place to help protect the future of Alaska’s wildlife. The bear feeds our family, the hide gets used for practical and traditional purposes and the memories last forever. That’s how we were raised, and it’s how we raise our kids.

We pushed off into the Sound with

the salty wind on our faces and the quiet hum of the motor behind us. The water was like glass, mirroring the snowy mountains that towered in every direction. A light mist hung over the shoreline, softening the rugged edges and making it all feel like a dream. This place doesn’t just look wild. It feels wild deep down in your bones. Every mile we traveled pulled us further from the noise of the world and closer to something real.

We headed toward a remote bay tucked behind rocky bluffs and thick alders. This was bear country – the kind of place where nothing feels disturbed and every sound is worth listening to. That evening, it didn’t take long before we spotted a black bear working the beach in the distance.

The wind was perfect. I climbed to the top of our Weldcraft, unstrapped the 12-foot dinghy from the roof, and lowered it into the water. Jen and I climbed in and quietly paddled toward shore, staying low and keeping our movements smooth and silent.

As we neared the beach, the bow

of the dinghy scraped against the shoreline, causing shale rocks to shift and crunch beneath us. Jen stepped out and tied the boat to a drift log on the edge of the beach. We grabbed our gear and I handed Jen the rifle. The stalk was on.

We moved carefully, stepping over driftwood and pushing through thick brush, all the while doing our best to stay quiet and out of sight. Everything felt right. The wind was steady, the bear was still feeding and we were closing the distance. But just as it felt like it was all coming together, the terrain threw us a curveball. A steep rock wall dropped straight into the ocean and blocked our path. There was no way around it without being seen. We were pinned down.

At just over 120 yards, the bear was still working the shoreline, completely unaware of us. I whispered to Jen to get steady on a rock ledge and take her time. She eased into position, standing boot-deep in the ocean with the tide rising around her legs. We only had a small window before the

opportunity slipped away with the water. She steadied her breathing, focused and squeezed the trigger when she was ready.

The rifle cracked and echoed through the steep mountain walls surrounding the bay. But instead of a solid hit, we saw dirt explode just above the bear’s back. It looked like a clean miss. The bear bolted into the alders and disappeared without a trace.

We paddled over to where the bear had stood and confirmed what we already suspected. No blood. No sign of a hit. Just a narrow escape. Jen was frustrated but calm. She let out a breath of relief knowing the bear wasn’t wounded, though missing is never easy. No hunter likes to walk away empty-handed, but that’s part of the process. We headed back to the big boat, quietly reflecting on the stalk, the miss and the hope that tomorrow might bring another chance. And it did.

I have found that bear hunting is often better in the evenings, so we take it

easy in the mornings. We usually start the day with a hearty breakfast of premade moose sausage and scrambled egg burritos. After breakfast, we make the most of our time in Prince William Sound.

We drop shrimp pots in the morning and pull up full baskets later in the afternoon. The kids love it. Watching the lines come up heavy and seeing the pots overflowing with bright pink shrimp fresh from the deep never gets old.

We grab the biggest ones and toss them straight into a hot skillet with garlic butter. Cooking them right there on the boat, with the salt air, the sound of the waves and the smell of shrimp sizzling over the burner, is something special. Honestly, there is no restaurant on Earth that compares.

As Jen cooked, the boys grabbed their rods and started casting off the side of the boat. They pulled in a few solid rockfish and even managed to hook a couple of lingcod hiding in the rocks below. If you’ve never seen a lingcod, picture something between a camouflage-covered dragon and a deep-sea alien. They have a mouth full of sharp teeth that you definitely do not want to mess with.

They might not win any beauty contests, but they are fascinating to look at, fun to catch and when they are in season, absolutely delicious on the table. The boys lit up every time one came flopping out of the water,

adding to the excitement of another unforgettable day on the

These moments between the hunts, sitting on the water eating fresh shrimp and swapping stories, are what make trips like this unforgettable.

That evening, we headed to a familiar spot tucked deep in a quiet bay and far from boat traffic and noise. Over the years, we’ve harvested several bears from this area. A large glacier slide looms above the beach and grassy slopes.

We sat for a while glassing on the boat without seeing much, but then finally spotted one. A very dark black bear emerged onto the shale and moved through patches of bright green grass. There was no mistaking it – this bear was bigger than the one Jen had missed the night before. The look in her eyes said it all. She was ready.

We climbed back into the dinghy and paddled toward shore. The tide was low, which left a wide stretch of slippery ground between us and the bear. We moved quietly across musselcovered rocks and seaweed that had been underwater just an hour before. We crossed a shallow stream and crept over slick stones, using every bit of cover the terrain gave us. The wind stayed steady in our favor, helping us close the distance.

Jen found a driftwood log to brace against and got into position. The bear

was still feeding and unaware that we were there. She slowed her breathing, lined up her shot and squeezed the trigger.

The bear dropped instantly.

It was one of those quiet, powerful moments in the field. Jen had stayed composed, learning from the day before, and she made it count when it mattered most. Watching her walk up to that bear, smiling from ear to ear, filled me with pride.

We radioed the boys from the boat, and soon the whole family was walking across the beach together. We skinned and butchered the bear right there, saving every piece of meat along with the hide and skull. We packed it all into the dinghy and hauled it back to the Weldcraft.

Jen didn’t let the miss from the night before shake her. She didn’t get discouraged and she never lost hope. Instead, she stayed focused, trusted the process and stepped right back into the hunt with grit and determination. This time, she connected with an even bigger, more beautiful bear.

We brought back to the boat more than just meat that day. We brought a story of perseverance, redemption and a moment our family will carry with us for the rest of our lives.

On the third day, it was my turn. After Jen’s success, I was itching to get out there.

The weather was calm and cool, perfect for a stalk. We spotted a bear meandering along a rocky beach, then watched it disappear into the alders. As I grabbed my bow, Leo and I climbed into the raft.

We rowed across the bay and

stepped out onto the gravel shoreline. We moved slowly, walking in shin-deep water to muffle our sound. The spruce forest above us stood silent and dark, with patches of green seaweed tangled in the driftwood at our feet. Every step felt electric.

… She persevered, however, and got a bruin the next day and was able to savor the moment of success with her youngest, Fisher. (LANDON ALBERTSON)

Just ahead, we spotted the bear again tucked into the alder brush. Leo leaned in and whispered, “There he is.” I nodded, nocked an arrow and began moving in.

At 30 yards, the bear stepped out of the alders and started making its way toward the beach. I drew my bow, thinking it would keep walking and give me the perfect shot. It was a later-thanusual spring, and the alders were just beginning to bloom. The bear paused every few steps to feed, using its long tongue to pull in the fresh white flowers. My arms started to burn as I held full draw; my heart was pounding so hard I could hear it in my ears.

The bear kept feeding, head down, completely unaware. At 25 yards, I hoped for a clean angle, but it stayed facing toward me. I didn’t want to risk a poor shot. I held my draw for nearly three minutes before my muscles gave out, and I had to let down. Thankfully, the bear didn’t notice.

It stepped onto the beach at 20 yards and moved even closer. Leo and I crouched motionless at the water’s edge, with nothing between us and the bear but a stretch of gravel and green grass. At 15 yards, the bear finally turned broadside and fed calmly in a thick patch of new growth.

I drew again, pushing through the fatigue. My muscles were already worn from the long hold, but I managed to settle my pin just behind the shoulder. Right then, the bear looked up and locked eyes with me. It had caught the movement. This was the moment.

I released the arrow; it hit the shoulder and the bear bolted into the brush. As it crashed through the trees, I saw the arrow snap off. My heart was still pounding as I looked over at Leo. His eyes were wide. He had filmed the entire encounter.

We waited, then followed the trail. A clear blood trail led us up the hill. Just 60 yards later, we found the bear. Relief washed over me. Getting that close to a wild black bear with a bow in hand is an experience you never forget. There is no adrenaline rush like it, and no deeper respect than standing that close to such a powerful animal, knowing you made a clean and ethical shot.

The author used a bow to take his black bear, and they made sure to utilize everything they could from both bruins. “The bear feeds our family, the hide gets used for practical and traditional purposes, and the memories last forever,” he writes. “That’s how we were raised, and it’s how we raise our kids.” (LANDON ALBERTSON)

“This trip gave us everything: A tough miss, a powerful redemption, full pots of shrimp, fresh fish, and a close-range bow hunt that tested every ounce of patience I had,” Landon (right) writes. “It fed our bodies and our spirits.” (LANDON ALBERTSON)

This trip gave us everything: a tough miss, a powerful redemption, full pots of shrimp, fresh fish, and a close-range bow hunt that tested every ounce of patience I had. It fed our bodies and our spirits.

As we motored back toward camp with the sun sinking behind the mountains, I looked around at my family, our boat loaded with meat and the wild beauty of Prince William Sound surrounding us. My heart was full. I felt thankful for these moments together and deeply grateful to call a place like this home. ASJ

Editor’s note: Author Landon Albertson grew up in Lakeview, Oregon, but now chases hunting and fishing adventures as an Alaskan transplant. Check out some of them at preyonadventure. com and on the family's YouTube page (search for “Prey On Adventure: Alaska Fishing & Hunting”).

BY SCOTT HAUGEN

Aflock of pintails circled wide of the decoys that bobbed in a little slough on the Alaska Peninsula. I figured the ducks were gone, and then my buddy hit a high note on a mallard call that turned the lead bird. The rest of the flock followed.

The birds headed into the wind, set their wings and coasted into our spread. “Take ‘em!” my buddy shouted. We dropped four from the flock, rounding

out a stellar morning of waterfowl hunting in Southwest Alaska.

Soon we were gathering decoys and reflecting on the previous two hours. It didn’t take long to pile our little string of a dozen floating goose decoys and a half-dozen puddle duck decoys into the boat. On top of those were our limits of ducks, Pacific black brant and cacklers, all taken from that spot. It was September 1. Alaska’s waterfowl season was off to a great start.

In the early weeks of waterfowl season, Alaska has many opportunities for hunters. In September, many puddle duck species are still in family units. They can be tucked away on tiny ponds, living on rivers or occupying creeks and estuaries. As the waning daylight hours advance, ducks will start flocking together. This is the beginning of the annual fall migration. Brant are among the first of Alaska’s

Early-season waterfowl hunting is one of Alaska’s most overlooked fall opportunities, and options are widespread here at the north end of the Pacific Flyway. Even as big game rule the roost here, targeting ducks and geese can be rewarding for both seasoned and inexperienced hunters. (SCOTT HAUGEN)

waterfowl to start their early flight south from the Arctic and Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta to staging grounds on Izembek Lagoon. Pintail and green-winged teal are also among the early-season migrators on the menu.

If you love fishing for late-season coho in October and are traveling to remote rivers in search of them, bring a shotgun. Cacklers and puddle ducks frequent a lot of rivers, ponds and tundra potholes in coho territory, creating memorable castand-blast opportunities.

One fall I filled a brown bear tag early in the hunt. Rather than leave the coastal zone, I hiked into the marsh each day and shot cacklers, pintails, mallards and teal. I didn’t have any decoys, only my shotgun, a duck call and goose call. That was all I needed.

Ducks and geese are gullible early in the season. Two of Alaska’s greatest strengths are its vastness and low human population. Hunting where ducks

and geese have seen few, if any, humans is common. The fact that many of the birds are young also means that they’re inexperienced and will respond well to decoys and calls. For these reasons, the hunting can be simple and straightforward.

It’s ideal if you can scout an area before hunting it. If you don’t have time or you’re traveling to hunt, the first thing to look for is birds. Find where ducks and geese are and watch them as they come and go. See if they’re feeding or relaxing. If feeding, that’s the place you want to be. Duck hunters refer to this as the X. If you’re on the X, the hunting can be fastpaced action. A lot of early-season puddle ducks are shot on the X throughout Alaska, with very minimal gear.

You don’t need the best, most expensive, biggest spread of decoys to fool early-season ducks. This time of year, ducks have yet to gain their prime plumage. Most ducks are brown, even the drakes that have yet to color up. Tossing out a half-dozen old duck decoys will often do the trick.

Rarely will you need more than a dozen decoys to fool early-season ducks. If in areas where fellow hunters are near, a bigger spread of decoys will help pull in birds. Having a decoy or two on a jerk cord to create movement on the water will help catch the attention of ducks and swing them your way.

A call is also a good tool to have. One mallard call that creates a crisp, clean quack is all you need. Mallards, pintail, teal, wigeon, shovelers – all puddle ducks – will respond to a basic mallard quack. You can’t count on distant ducks seeing your decoy spread, but having a call to get their attention can make the difference.

For geese – be it brant, cacklers or other subspecies of Canada geese – I like going with six to 12 floating decoys and a few-dozen silhouette decoys set along a shoreline. Silhouette decoys are great because they’re easy to pack, are affordable and it’s simple to put out a lot of them to create the feel of a big flock.

• Easy Loader & Deuce accommodate 2 dogs up to 65 lbs each

• EZ-XL accommodates 2 dogs over 65 lbs each

• Made from High Density Polyethylene with UV protection

• Easy Loader fits most full size pickups, SUVs & large UTVs

• Deuce fits smaller pickups, SUVs & UTVs

• EZ-XL is for larger breed dogs & full size vehicles

• Vents, cold weather door covers, insulated covers & custom kennel pads available

Brant usually fly low to the water, so making a line of silhouette decoys is a great way to catch their attention. Often, all we use for brant are Big Al’s silhouette decoys. A lot of times we’re just hiking beaches, setting out lines of silhouettes at low tide, then moving them up the beach as the tide comes in.

Silhouette decoys and windsock goose decoys are a good combination when hunting cacklers on the tundra.

Cacklers, Taverner’s and lesser Canada geese respond well to this decoy combination. When blueberries and low-bush cranberries are thriving, hunting geese on the tundra can be very productive.

Don’t feel like you have to spend $1,200 on waders, twice that on a gun, $75 on a box of shells and $300 for a dozen decoys just to shoot a duck. You don’t.

Start with an inexpensive set of breathable waders. You can even use your fishing waders. Waders don’t have to be camouflaged because you’ll be hiding in grass, brush or in a blind. A lightweight rain jacket will keep you dry. Layer underneath the waders and rain jacket to attain the desired comfort level for your early-season hunt. If hunting from a boat, you might dress warmer than if hiking in.

As for a shotgun, you might already have one of those too. If not, a basic 12-gauge with a full or modified choke is all you need. You can get carried away with specialized waterfowl shotguns that cost a lot of money, but I’d suggest starting with something economical to see if you like waterfowl hunting, then upgrade as you gain experience.

Nontoxic shot is a federal requirement for hunting waterfowl. Steel shot is good

and will get the job done. For the price and performance, Kent Fasteel is hard to beat. Kent’s quality of steel, the wad and the powder charge all deliver the perfect speed and pattern for consistently killing ducks and geese. Size 4 shot is great for duck hunting, whereas the larger number 2 shot is fitting for geese.

There are other nontoxic loads out there, with bismuth and tungsten being most popular. Don’t get caught up in thinking you need to spend big dollars on a box of shells to kill ducks and geese. Be patient, let the birds work the decoys, shoot only when they’re in range – 40 yards or less – and you’ll kill more birds and save a lot of money on shotgun shells.

I’ve used a lot of duck and goose calls over the years. If I had one brand of call to use in Alaska, it would be Slayer Calls. Their acrylic bodies are tough and produce loud sounds, which are great for reaching across the tundra, carrying over big water and penetrating high winds and rainy conditions.

Slayer’s Tar Belly goose call works great for cacklers, white-fronted and snow geese. It’s a fantastic, all-around call I’ve had exceptional success with. Their Ranger duck call is my top pick when it comes to calling in ducks. This single-reed call is simple to blow, very loud and it’s easy to create a range of sounds

The LeeLock magnum Skeg #LMS-04 is made for Minnkota Instinct motors. It will drastically improve the steering performance and straight line travel of your bow-mounted motor. Not only does this Skeg improve your motor’s performance, it also makes it much more efficient. Your batteries will run longer on a charge. A LeeLock Skeg is a vital part of your trolling motor system. This oversized skeg is made of 5052 aluminum. The size is 8 3/4 inches high by 10 inches wide and it’s 3/16 inches thick. It comes with clear PVC coated stainless steel hose clamps.

The Heavy-Duty Quick Change Base #QB-03 is like the standard Quick Change Base, but beefed up to provide a wider footprint. This provides a more secure mount. Like the standard Quick Change Base, the Heavy-Duty base allows you to easily and quickly switch between the #CRN-01 Columbia River Anchor Nest, any of the 3 Bow Mount Trolling Motor Mounts or the #BL-01 LeeLock Ladder. Simply remove the pin and slide an accessory out and slide another accessory in and replace the pin. The Heavy-Duty Quick Change base mounts to almost any power boat as long as the footprint fits on the bow area of the boat. It has 7 5/16 inch mounting holes. The Heavy-Duty Quick Change Base is handmade of aluminum. Go to LeeLock.com to order the Base alone or to add the CRN-01 Columbia River Quick Change Anchor Nest, the three Bow Mount Trolling Motor Mounts, or the LeeLock Ladder to your order.

with. Calls are one thing I won’t skimp on when it comes to hunting in Alaska because the habitat is so vast and the conditions can be harsh. A loud call can make the difference between going home with a fresh dinner or not.

As for puddle duck decoys, grabbing some from a local garage sale is all you need for early-season waterfowl hunting in Alaska. I prefer having a mix of colors, even brands of decoys, for hunting early in the season. This is because the real ducks that make up an early-season flock can vary in size and color.

If you want to maximize decoy movement on calm days, a Decoy Spreader System from Motion Ducks is worth every penny. The four-decoy spreader system is perfect for small, early-season

spreads. I’ve been using them for years and they’ve been the reason behind a lot of successful hunts. They have them for goose decoys also.

There are many different geese to hunt in Alaska, from brant to whitefronts, snow geese to six different subspecies of Canada geese. Having species-specific decoys will help fool the birds you’re targeting.

When hunting coastal habitats and estuaries where brant and Canada goose populations overlap, having a line of six to 12 floating Canada goose decoys will help capture the attention of wary honkers. If targeting Canadas on dry land, shell decoys will do the job. Shell decoys are visible from all angles.

Still, adding silhouettes or wind sock

decoys in with your shells will increase the size and visibility of the spread.

As with any hunting in Alaska, safety is top priority. It’s no different with waterfowling. If you’re not an experienced boater, go with someone who is and learn from them. Not only is safe navigation a must, but being able to repair a motor should it break down is essential, for rarely will you be in a place where you can call for help. An emergency locating device is a good investment too.

Among the biggest dangers of waterfowl hunting in Alaska is the tide. Alaska’s vast coastlines have some of the biggest tide swings on the planet. Getting stuck on dry ground and having to wait for the tide to come rolling back in is one thing, but it’s the big mud flats that can be dangerous. Avoid hiking into mud flats unless other hunters are present and the bottom has been proven solid. Mud and heavy tides can be deadly in Alaska, so hunt with caution.

If new to waterfowl hunting or you’ve recently moved to Alaska, learning to hunt with a licensed guide will greatly expedite the process. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game has a listing of licensed waterfowl guides throughout the state, as well as other valuable information on waterfowl hunting. Their Alaska Wildlife Notebook Series is packed with great information, something I used back in my days of teaching high school biology in Point Lay and Anaktuvuk Pass.

With some basic gear and a desire to learn, you’re on the way to discovering just how fun early-season waterfowl hunting can be in Alaska. As with any hunting, the more you’re out there, the more you’ll learn and the more proficient you’ll become.

Once you experience flocks of ducks and geese committing to your decoys, you’ll be looking for every opportunity to hunt them before they head south for the winter. ASJ

Editor’s note: For signed copies of Scott and Tiffany Haugen’s best-selling cookbook, Cooking Game Birds, visit scotthaugen .com. Follow Scott’s adventures on Instagram and Facebook.

Cumberland’s Northwest Trappers Supply is your onestop trapping supply headquarters, featuring one of the largest inventories in the U.S. We are factory direct distributors on all brands of traps and equipment which allows us to offer competitive prices. Give us a try. Our fast, friendly service will keep you coming back.

We are the new home of “Trappers Hide Tanning Formula” in the bright orange bottle.

Retail & dealer inquiries are welcome.

If you are in the area, visit our store!

Request a catalog or place an order by phone, mail or on our website.

Storms and winds can force ducks to move. Pay attention to early-season weather and be ready to hunt when the time is right. (SCOTT HAUGEN)

BY SCOTT HAUGEN

Last season I went out with a group of young hunters, all in their early 20s. The wind was blowing hard. Ducks were flying but not committing. After an hour of frustration, one kid left. I was a guest, so I kept quiet. Finally, another kid asked me, “What should we do?” “See the flat water against that bank,” I pointed to the east. “That’s where we need to move the blind and decoys.” It took time and effort, but with four of us it wasn’t bad. Two hours later we left with limits.

To me, it was obvious that the ducks wanted into the pond we hunted, but they