The Science of Mindfulness

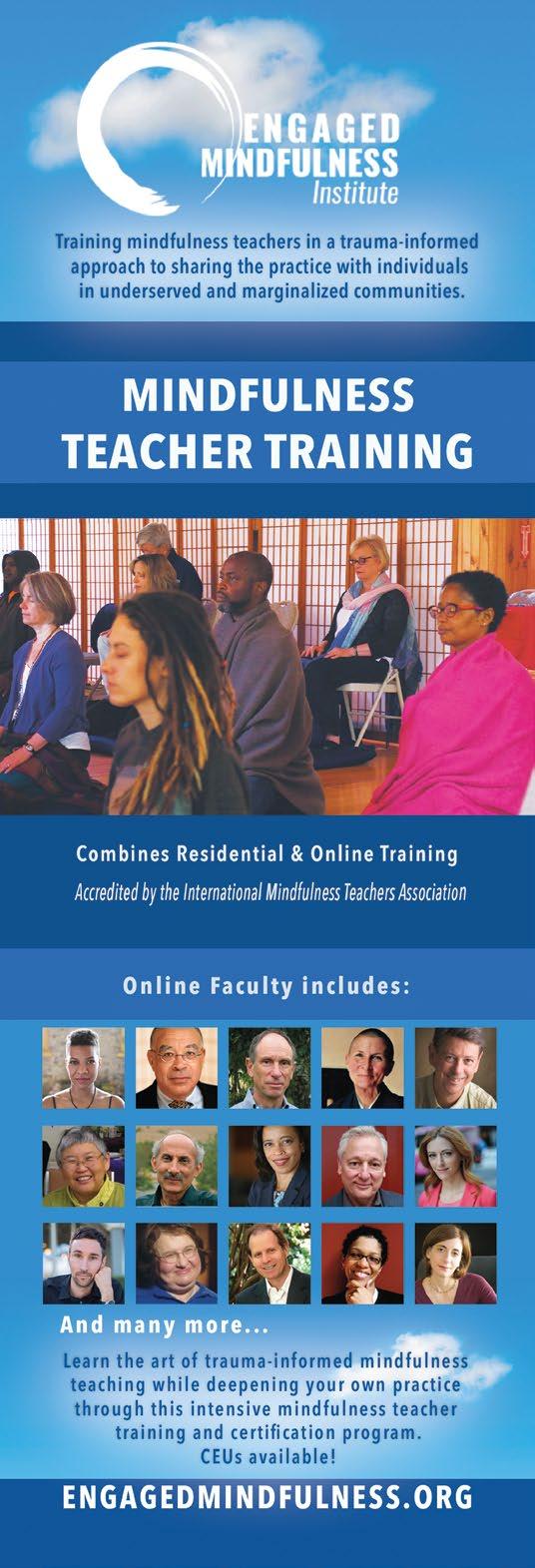

Mind-wandering causes us to miss 50% of our lives. Through groundbreaking research with elite soldiers, Dr. Amishi Jha discovered exactly how everyone can use mindfulness to strengthen our attention and working memory.

p.46

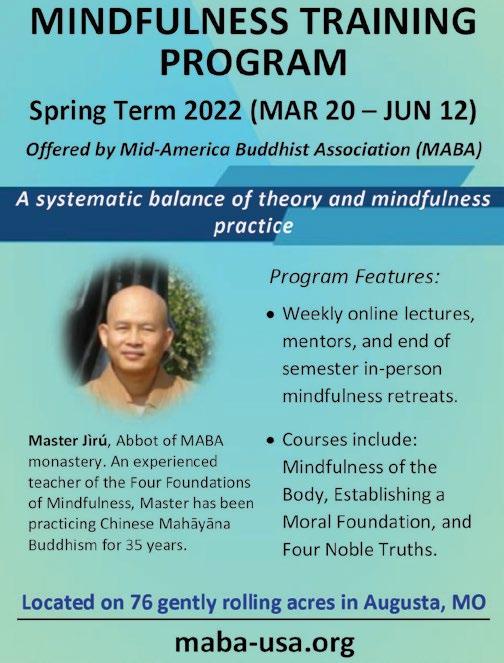

We’re bringing our content to life with Mindful Courses—offering practical guidance from expert teachers and inviting you to bring the benefits of meditation and mindfulness into every facet of your life. Find focus and uncover your inner power.

I often find myself in moments where I fail to see someone else’s truth. Once, when I was younger, I got to paint houses for Habitat for Humanity on a reservation in South Dakota. There were 15 of us sharing potluck meals and exploring the Black Hills on day trips with our hosts from the reservation. On one trip, a man named Elvis took us to see Mt. Rushmore. As we all stood there at the base of the mountain, in awe of this symbol of our country, Elvis, who was quick with an easy smile and a humorous anecdote, casually said: “Imagine there was a statue of the man who raped your mother in your living room. Imagine you were forced to carve it.” He looked at us, we looked at him. A heavy silent moment passed between us all before he lightened the mood with a joke I can’t remember.

I’ve never forgotten that moment. That casual and brutal glimpse into a perspective so different from my experience of American culture has served as a reminder of the enormity of what I don’t know (and can never truly understand, regardless of what I read).

Practicing mindfulness gives us the opportunity to acknowledge our unique perspective in the world and then unhook from it a little. We get to widen our lens and honor the gaps that exist between our individual perspectives—and the challenges those gaps can evoke. We can investigate the stories we tell, about ourselves and others, and consider how we might compassionately bridge the distance those stories create between us.

For this December issue of Mindful, we’re inviting you to explore the gift of mindfulness from many perspectives. On page 13, Dr. Sara Lomax-Reese reminds us that contemplative spaces are for everyone. On page 22, Elaine Smookler explores how we can remain open to the full dazzling array of beauty this life has to offer. On page 34, four Indigenous wisdom keepers reveal how their mindfulness practices inform their healing journeys. And on page 46, neuroscientist Dr. Amishi Jha details the cutting-edge research on exactly how much meditation fine-tunes our brain’s attention system so we can choose how we show up in this world.

Mindfulness comes in as many shapes, sizes, colors, and intensities as there are people in the world. The challenge is to practice—to sit and let things be as they are for a little while, notice what arises, remember that every truth is partial, and breathe into whatever shows up with kindness and compassion.

With love and gratitude,

Two Box Sets

4 designs | 12 cards each Zen Flowers & Calligraphies

The Mindful Family Guidebook

by renda dionne madrigal

by renda dionne madrigal

“

There is truly nothing else out there that combines American Indian wisdom and practices with mindfulness teachings.”

—diana winston author of The Little Book of BeingWe Were Made for These Times

by kaira jewel lingoIn ten concise chapters you’ll learn powerful ways to meet life’s challenges with wisdom and resilience.

“

—tara brach author of Radical Acceptance

The Eight Realizations of Great Beings

by brother phap hai

by brother phap hai

Brother Phap Hai has made accessible the ancient wisdom of Buddhism, shedding a bright light on the truth of our existence.”

—les kaye abbot of Kannon Do Zen Center and author of A Sense of Something Greater

“ Sourced in heart-wisdom”

Editor-in-Chief

Heather Hurlock heather.hurlock@mindful.org

Managing Editor

Stephanie Domet

Founding Editor

Barry Boyce

Senior Editors

Kylee Ross

Amber Tucker

MINDFUL COMMUNICATIONS & SUCH

Creative Director

Jessica von Handorf jessica.vonhandorf@ mindful.org

Associate Art Director

Spencer Creelman

Junior Designer

Paige Sawler

Associate Editors

Ava Whitney-Coulter

Oyinda Lagunju

Mindful is published by Mindful Communications & Such, PBC, a Public Benefit Corporation.

Chief Executive Officer

Bryan Welch bryan.welch@mindful.org

Chief Financial Officer

Tom Hack

Accounting

Kyle Thomas

Director of Technology

Michael Bonanno

Application Developer

Garang Thiong

Manager of Information Systems

Joseph Barthelt

Director of Human Resources

Lauren Owens

Head of Coach Development

Zina Mercil

Office Manager

Deandrea McIntosh

Administrative Assistant

Lydia Kajumba

Advisor

Alan Nichols

Board of Directors

President Brenda Jacobsen brenda.jacobsen@mindful.org

Founding Partner

Nate Klemp

Vice President of Operations

Amanda Hester

Vice President of Marketing

Jessica Kellner

Director of Marketing

Leslie Duncan Childs

Marketing Manager

Alissa MacDougall

Marketing Coordinator

Audhora Rahman

Director of Events

Julia Sable

Events Manager

Maggie Colby

Director of Client Services

Monica Cason

Client Relations Assistant

Abby Spanier

David Carey, James Gimian, Brenda Jacobsen, Eric Langshur (Chair), Larry Neiterman, Bryan Welch

Advertising Director

Chelsea Arsenault Toll Free: 888-203-8076, ext 207 chelsea@mindful.org

CONTACT / INQUIRIES

Publishing Offices

5765 May Street Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3K 1R6 Canada mindful@mindful.org

Corporate Headquarters 515 N. State Street, Suite 300 Chicago, IL 60654, USA

Advertising Account Representative

Drew McCarthy Toll Free: 888-203-8076, ext 208 drew@mindful.org

Editorial Inquiries

If you are interested in contributing to Mindful magazine, please go to mindful.org/submission-guidelines to learn how.

Customer Service

Subscriptions: Toll free: 1-855-492-1675 subscriptions@mindful.org

Retail inquiries: 732-946-0112

Content Licensing inquiries@mindful.org

Readers share what helps them embody their unique power and confidence.

What makes you feel empowered? How empowered do you feel?

I feel most empowered when I drive down the 110 Freeway. I belt out show tunes and visualize singing to an audience of thousands.

Grant G.

I feel empowered when I surrender. Letting go of expectations and trusting the universe is liberating and empowering!

Joanie

When I stand up for myself.

heatherlaurena

Knowing I always have choices! Making simple, positive choices every day to build my physical, mental, and spiritual muscles yields big results and makes me feel empowered.

Kristen K.

Noticing the signs of progress or healing in both body and mind.

Kalafern1848

I feel empowered when I finally verbalize my feelings, my dreams, my goals. By putting it out there I release some of my insecurities about whatever it is and can pursue my dreams and goals.

Jane W.

When I acknowledge my capabilities. When I take accountability. When I give myself compassion. When I am being present.

kristinsvenlarsen

When I see the ‘oh I get it’ look in a student’s eyes after helping them.

jmomydrz

Smile of a loved one. carpincho0119

I'M BASICALLY SHE-RA

NOT SO MUCH

Next Question… What helps you manage change?

Send an email to yourwords@mindful.org and let us know your answer to this question. Your response could appear on these pages.

↑

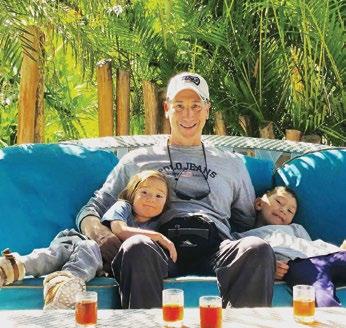

@jhanellemrivera says she feels best when she's being creative and playful—and this gives her more energy to be there for others.

↓ @peacfull_flower shared this pic of the people who help her feel the most like herself.

→ @wolfconnection helps empower at-risk youth with confidence, education, and life skills at their wolf sanctuary.

HBO’s In Treatment is giving viewers a front-row seat at patient-doctor therapy sessions.

The show aims to highlight the importance of mental health while addressing the stigma therapy carries in various groups. “I hope we just provide

another branch of resource for people in our community,” Uzo Aduba, who plays Dr. Brook Taylor, said on a panel with National Alliance on Mental Illness of New York City (NAMI). Aduba notes there are family and friends, and faith leaders, as sources of outreach, “but

also there’s this branch of therapy as a source of outreach.” HBO has also partnered with Ten Percent Happier to share meditation guides inspired by In Treatment characters, and launched the Therapy Is for Everybody campaign, presenting talks from multicultural mental health and wellness professionals.

It’s often said that a dog is a man’s best friend, but

central themes for asylum-seekers is this common experience of loss. They had to leave behind all sense of normalcy,” Levy told BuzzFeed News. “For them, especially after surviving so much trauma, pets are this lifeline of normalcy and emotional support.”

What do a decadeold tomato seed, an inhaler, and a badminton racket have in common? They’re all objects featured in the world’s firstever Happiness Museum.

anyone with a pet would argue that their furry, feathery, or scaly companion feels more like family than anything else, which is why being separated can be heartbreaking. So Mascotas Para Migrantes (Pets for Migrants), a program organized by immigration attorney Taylor Levy and communications worker Jordyn Rozensky, is currently working to reunite immigrants and asylumseekers with their pets. “One of the

In July of 2020, at a time where the world desperately needed a reason to smile, the happiness museum opened its doors in Copenhagen, Denmark. Eight different exhibits show varying perspectives on happiness: for example, a “happiness lab” uncovering the psychology of laughter, and a curation of objects representing contributors’ most cheering memories. Their mission statement? “Our hope is guests will leave a little wiser, a little happier

and a little more motivated to make the world a better place.”

The British organization Horses Helping People is expanding its mindfulness and well-being programming with a grant from the UK National Lottery Community Fund to help more people rein in mental health challenges. Learning to care for, ride, and communicate with horses can help people with disabilities, behavioral challenges, or addiction build confidence and feel calm. “Often we only need to be in a horse’s presence to feel a sense

of wellness and peace,” co-founder Debbie La-Haye told local news.

A nonprofit in Philadelphia offers healing for communities of color through art and mindfulness. The Woodlands—a historic cemetery and green space— was home to New Grass, a summer 2021 event that blended live jazz, yoga, and meditation, hosted by Ars Nova Workshop in collaboration with Spirits Up!, which works toward Black liberation. Mark Christman of Ars Nova, and Sudan Green, who started Spirits Up! see a lot of resonance between

jazz and mindfulness. “Yoga or mindfulness in general is always asking you to be more present,” Green notes. “We are presenting in a cemetery, where life and death are very present to us and sometimes in kind of uncomfortable ways. And we’re living in a moment that’s been a bit of a drag, to say the least,” adds Christman. Both hope that their work helps create “spaces that can accommodate and even reconcile” experiences of racial harm, Christman says, “making way for the present through sharing art and conversation and meditation.”

16-year-old Shane Jones began bidding on repossessed storage lockers so he could sell the contents and make extra money—until he saw what was inside. He didn’t feel right re-selling family heirlooms, baby photos, and other personal knickknacks. Now, he buys the storage lockers and follows clues he finds inside to reunite the contents with the original owners.

posts the photos from her merino farm in Australia where she helps orphaned lambs stay warm by putting them in baby sweaters. She receives hundreds of messages from people who find joy in her photos, invites commenters to help her name the lambs, and some fans even send handknitted sweaters.

HBO Max apologized for a test email that an intern accidentally sent out and thousands of Twitter users responded with empathy. Replies poured in that began “Dear intern” and ended with embarrassing work stories that could likely reassure almost anyone that their day could be worse. Dear intern, we’ve all been there.

Research gathered from Carleton University, University of Illinois, and others.

“The Journey Toward Wholeness places the Enneagram in its correct context—that of healing, of transformation, and of integrating the different aspects of our psyches. . . . It gives kind and steady guidance on how we can more consciously cooperate with grace and create more balanced, compassionate, and authentically spiritual lives.”

—Russ Hudson, author of The Enneagram: Nine Gateways to Presence

is a highly sought-after speaker, teacher, and internationally recognized Enneagram master teacher who has taught thousands of people over the last thirty years. She is the author of The Path Between Us, and coauthor, with Ian Morgan Cron, of The Road Back to You. She is also the creator and host of The Enneagram Journey podcast.

An international team of scientists examined weekly data from 221 executives to see if they might benefit from an app-based, workplace mindfulness intervention. The eightweek program included audio guided individual mindfulness practices and activities such as attending to bodily sensations, breathing, stretching and relaxation exercises, and instruction on mindfulness for workplace challenges. At each week’s end, participants were surveyed on their job satisfaction, work

engagement, emotional exhaustion, and mindfulness. Over the course of the program, participants’ selfreported mindfulness increased— and in turn, the boost in mindfulness was generally related to improved work engagement and job satisfaction, and less emotional exhaustion Additional studies using a control group are needed to better understand these effects.

In a pilot study, researchers at the University of Illinois tested whether a mindfulnessbased childbirth preparation program would

ease new parent distress better than typical prenatal instruction. They randomly assigned 30 expectant mothers in their third trimester to either twoand-a-half days of a mindfulness program or standard childbirth education. The mindfulness group was taught strategies for coping with labor pain and fear, and for parenting an infant, and were given audio of guided mindfulness practices for optional use. Both groups completed assessments of perceived stress, mood, and mindfulness before and after the program, six weeks post-birth, and one to two years later. The new moms who practiced mindfulness reported less depression over

a one-year period than control group members. Those in the mindfulness group with higher anxiety and/or least amount of mindfulness before the intervention had the greatest benefits. Findings suggest that mindfulnessbased prenatal instruction may help reduce maternal distress following childbirth.

personal goals. In the first study they randomly assigned 200 university students to either a mindfulness group, or a control group. The mindfulness group listened

Meditating while free of digital distractions may help motivate students to pursue their personal goals.

A new reason to keep your meditation distraction-free: It could boost motivation.

Researchers at Carleton University in Canada conducted two studies to see if meditation enhances motivation to tackle

to 10 minutes of guided meditation instructing them to bring attention to the present moment and the physical sensations of their breath. The control group listened to 10 minutes from a podcast about the history of emojis. Both groups completed a survey assessing their level of mindfulness, motivation to complete a word puzzle, and commitment to fulfilling their personal goals. Ten minutes later they reported on their motivation again, and completed two tasks to check if they’d paid attention to their assigned recording. The

10 minutes later, was relatively unchanged. The control group was less motivated than meditators immediately after listening to the podcast, as well as 10 minutes later. Many participants in both groups reported doing something else while listening to their assigned recording, making it unclear whether either meditation or listening to the podcast affected their behavior.

In Study 2, 120 different students were told to turn off their cellphones, then listen to either the meditation instruction from Study 1 or the emoji podcast. This time the mindfulness group reported increased goal motivation compared to the control group, suggesting that meditating while free of digital distractions may help motivate students to pursue their goals.

“Coaching is about helping others find their own best solutions through transformational listening, powerful coaching questions, designing an action plan and providing accountability. It is not about giving advice.”

Dr. Elliott B. Rosenbaum, Founder, ASPLC

Dr. Elliott B. Rosenbaum, Founder, ASPLC

Did

My attention span feels absolutely shattered by— well, everything. Stress, anxiety, social media, my to-do list. How can I rebuild it?

Even without stress, anxiety, and more, the mind will wander. And in fact, research shows it wanders 50% of our waking moments. Mindwandering is ubiquitous. And, contrary to popular belief, mindfulness doesn’t cause all thought to cease.

• Support well-being and resilience

• Combat stress and burnout

• Based on real human relationships

• Best-in-class engagement

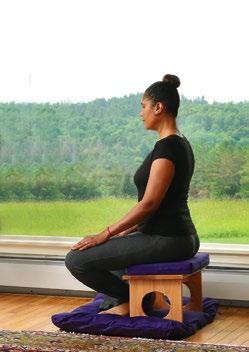

Mindfulness can help you practice stabilizing and directing your mind, which comes in handy especially in moments when we may feel stressed, distracted, or overwhelmed. This focused-attention practice can help you learn to direct your full, undivided attention to a single object of focus, in this case the experience of breathing. And when (not if) your mind wanders, you simply bring your attention back to the breath.

1 Sit in a way that is alert yet relaxed. Notice your body, your feet on the ground, your legs and torso as they make contact with your seat or the ground. Also notice your posture: See if you might sit in a way that’s upright but not rigid, relaxing into your body and breathing normally.

2 Begin to notice your breath. Without changing

your breathing, direct your attention to the experience of breathing, the sensations of the in-breath and the sensations of the out-breath. Noticing the air coming in and out of your body, firmly but gently direct your full, undivided attention to this experience of breathing, whatever that means to you.

3 Notice when your mind wanders. Simply take note and then gently bring your attention back to your breathing. Come back to the experience of in-breaths and outbreaths, the full cycle of breath. This is the process of focusing attention on the breath.

Even with a very short practice, you can get a sense for how this exercise is useful for cultivating a calm and focused state of mind.

you know Mindful offers a customizable, scalable mindfulness training program for the workplace?

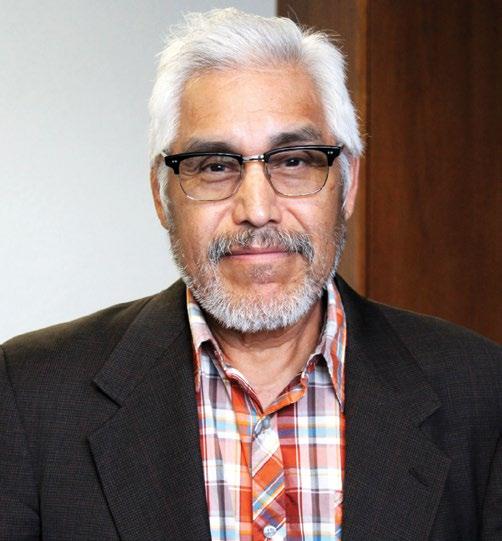

Dr. Sara Lomax-Reese is the CEO of one of the few Black-owned radio stations in Pennsylvania, WURD Radio, and while she is often regarded as a selfassured trailblazer, she is quick to share that that hasn’t always been the case.

“As I was graduating from college, they had an opening at an annual Black history publication. Even though I didn’t really know that much about what I was doing, it was an incredible opportunity to just learn the mechanics of putting a publication together. So, it’s been a bit of a random journey.”

Though Dr. LomaxReese might label her journey “random,” it’s clear that her commitment to her community has served as a compass.

“My mission is to create a space where our voices can be heard authentically, and consistently. Everything I do at WURD is to create a place where we can be who we are in all of our diversity, all of our complexity, all of our excellence, and even all of our mediocrity. All of our voices deserve to be honored and heard.”

While Lomax-Reese works to create space in media for people of color to be heard, she is looking to create that space

in mindfulness as well, as cocreator of the People of Color meditation group, which meets on the second Sunday of each month from September to June.

“There are so many spaces that have not welcomed Black and brown people, some of which includes the yoga and meditation world, and it can cause some to feel as though it’s not for them. I’m encouraged that Black and brown, younger people are owning these spaces and creating these spaces and saying, ‘Not only are these for me, but these are also exclusively for me. I’m creating my own universe specifically for Black and brown people.’”

And for anyone hesitant about speaking out and making their voice heard, Lomax-Reese shares a piece of advice she lives by.

“There’s a quote by Marianne Williamson that goes, ‘Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure.’ Who are we to not embrace how great we are or to play ourselves small? The work is to be your biggest and best self, because that’s what the world needs. So take care of yourself and cultivate that inner fire, and encourage that inner compassion.”

The work is to be your biggest and best self, because that’s what the world needs. So take care of yourself and cultivate that inner fire, and encourage that inner compassion.”PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY DR. SARA LOMAX-REESE

Remember: Meditating requires having no equipment whatsoever (besides a mind and a body). Still, we’d hardly be human beings in 2021 if we weren’t developing a plethora of ever-more-sophisticated products aimed at deconstructing, accelerating, or supercharging even our contemplative practices. Are these latest elite mind-hacking technologies ingenious, or indulgent? You decide.

Put a ring on it : A smart ring developed by startup Dhyana tracks heart rate variability, revealing how long the wearer spends in a state of focus while meditating. Dhyana partnered with the Indian Olympic Association to provide rings for the entire Indian Olympic team, making it the first meditation device officially used for the Games.

Lie detector? Seeking “to reconnect the world to their hearts and intuitive wisdom,” the Sensie app feeds you statements like “I can change my life for the better.” Then, shake your phone in your hand, and Sensie uses sensors to detect muscle tension, indicating stress or mental conflict with the statement. Sensie then serves “automated personalized coaching procedures.” Yay?

Fancy hat that reads your mind: Helmets made by Kernel, a (you guessed it) tech startup, give a front-row seat to the action inside the wearer’s brain. Tiny electrodes sense when neurons fire, and use that information to evaluate attention, problem-solving, emotional states, brain performance, learning, and information flow. Bring your wallet. They ring in at $50,000.

Our take on who’s paying attention and who’s not

by AMBER TUCKER

by AMBER TUCKER

A creative-studio owner in Buffalo, New York, inexplicably received more than 150 Amazon packages she hadn’t ordered— filled with brackets for making COVID masks. After Amazon said she could keep the errant wares, she used them to create DIY mask kits for children at local hospitals.

Is everything really better, down where it’s wetter? A 19-acre lot listed for sale in Shrewsbury, Ontario, looked like a steal at $99,000… but the land is entirely under water. “This property … could have endless possibilities in the future. Be creative,” the listing read. At press time, it appears this swamp’s been sold.

As the climate crisis looms, fossil-fuel workers are stepping up: A recent survey shows a majority of Canadian oil and gas employees want to transition to a net-zero-emissions economy. Worker-led organizations like Iron and Earth “empower the fossil fuel industry and Indigenous workers to build and implement climate solutions.”

Indigenous communities in northern Peru, alongside environmental organizations and researchers, are protecting their forests: Since 2018, through a program of patrolling and reporting signs of illegal activity using smartphones, these communities have significantly reduced deforestation.

In Beaverton, Oregon, a pet cat wouldn’t stop stealing items like gloves and kneepads from the neighbors. Finally, her abashed owner made a clothesline out front to display the stolen goods, next to a sign: “My Cat Is a Thief. Please take these items if they are yours.”

Tempers fizzed in the Hamptons last summer, due to a shortage of champagne caused in part by the pandemic.

Vacationers and residents made do with lesser sparkling beverages, like prosecco, until hundreds of cases of bubbly arrived via private planes. ●

Enter for a chance to win these unique mindful products just in time for the holiday season!

Prize package includes:

• Handcra ed Bracelet from meaning to pause®

• 1-hour, virtual private Mindfulness Meditation session with Ellen Patrick, Yoga Therapist and Mindfulness Meditation Teacher

• 4-day Silent Retreat from Art of Living Retreat Center

• $250 gi card to Sudara

• Ultima Replenisher Electrolyte Mocktini Variety Stickpack Pouch + Festive Holiday Low Sugar Cocktail Recipes Booklet

• Thich Nhat Hanh Classics Series from Parallax Press

• Mindful Writing Course

• Geometric Zafu Zabuton Set from Dharmacra s

• Take in the Good Book, Gemstone Bracelet, and Whole-School Program from Stressed Teens

• FocusCalm Headband from BrainCo Tech

Enter online by December 10, 2021 for your chance to win!

mindful.org/holiday-2021

Racing through a meal might assuage cravings or help us dodge emotions—but, by taking it slow, we invite savoring and satisfaction to the table.

By Lynn Rossy

By Lynn Rossy

I often teach what I need to learn, and, boy, is this lesson a big one for me. I move fast, talk fast, think fast, and drive fast. The faster I move, the more lost in thought I tend to be and the harder it is to fully experience the present moment. One morning I was so caught up in the acceleration of life that, while combing my clean, wet hair, I thought, Have I taken a shower yet this morning? I had been completely absorbed in my "to-do" list for the day.

This accelerated pace also prevents me from knowing that I ate, how much I ate, and whether I even liked what I ate. How many times have you stopped after being lost in thought and found the potato chip bag empty without even realizing that you ate them all?

To live fully in the present moment and wake up to our senses requires that we put on the brakes a little. You can’t experience the ride when the landscape is whizzing by and you’re missing the essential information you need to create the life you want. Slowing down helps you notice how you are feeling, what you are thinking, and the sensations in your body (such as hunger and fullness) as well as the sights, smells, and sounds around you. These messages are guideposts to your life.

If, like me, you feel a lot of urgency to fix the way you eat, fix your body, or fix your life, you probably have the feeling of going around in circles without getting anywhere. The truth is there is nothing to fix, but much to explore with curiosity and kindness. By first slowing down, you are placing yourself in the perfect position to hear the answers from within that tell you what you need to know about the food

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lynn Rossy, PhD, is a health psychologist specializing in mindful eating and living. She developed a 10-week, empirically validated Eat for Life class that teaches people to eat mindfully and intuitively, love their bodies, and find deeper meaning in their lives. Lynn is a longtime practitioner of mindfulness meditation and yoga, and is the president of the Center for Mindful Eating.

you eat, what your body wants and needs, and the truth of who you are.

Slowing down and exploring your senses as you eat is only the beginning. As you learn to luxuriate in the moments you have with food and your body, your entire life naturally becomes suffused with the beauty of mindful attention and love. Slowing down helps you notice more, and what you notice can teach you volumes about the most important aspects of life. The answers are already waiting for you; all you need to do is slow down to listen.

When I say “sit down and just eat,” I don’t mean sit in your car and eat while you’re driving, sit at your desk and eat in front of your computer, or sit down in front of the TV and eat while you’re watching your favorite show. I am suggesting that you sit down at a table in your own home or apartment (preferably in the dining room or kitchen) and eat without distractions of any kind (even the distraction of other people)— just you and your food and the experience of noticing and savoring. If you want to sit outside and eat, that’s wonderful—take a moment to acknowledge the luxury of that option.

I realize asking you to "just eat" is a big ask. Most of us eat while doing other things. To demonstrate, did you know that 20% of all American meals are eaten in the car? And research from the Hartman Group suggests that 62% of professionals typically eat lunch at their desks, a phenomenon social scientists call “desktop dining.” This unconscious munching in front of a screen (computer or TV) while you’re working or otherwise distracted leads to eating more than your body needs or you would even want, if you were paying attention. Multitasking is impossible for the brain to do well, because when your attention

is divided, it’s half as effective. Even if you are “just eating,” if you’re daydreaming about other things, you will miss both the pleasure of eating and the signals that tell you when to stop.

I fell in love with the practice of “sit down and just eat” at a meditation retreat. One of my biggest pleasures in going on a meditation or yoga retreat is that there is plenty of time to eat—at least an hour. I have the pleasure of eating alone (because often the meals are consumed in silence), and the meals are vegetarian, organic, locally sourced, and prepared by loving hands. There is hardly anything more luxurious than having meals ready and waiting for you and all of the time in the world to eat. Taste seems to explode from the food, as each bite is filled with wonder and nourishment.

Set aside some time when you will be undisturbed, with no other distractions for about 30 minutes. Pick a food or dish that will be delicious and satisfying to you. It doesn’t have to be a gourmet meal. For instance, I like nothing better than sitting down with a plate of fresh tomatoes (particularly in the summer), avocado, and goat cheese with some good balsamic vinegar and olive oil drizzled over the top, along with a few salty chips. Use the BASICS of Mindful Eating. Notice any time your mind wanders away from the experience of chewing, tasting, and savoring. It’s OK that the mind wanders. Your job is just to notice and keep coming back to the experience of eating and savoring.

The BASICS of Mindful Eating provide a guideline for you to practice “sit down and just eat.” The BASICS acronym can guide you before, during, and after eating. Practicing with these instructions can change the way you eat forever. It’s people’s favorite takeaway from my class. →

Discover meaningful opportunities to DEEPEN YOUR PRACTICE with the guidance of experts and online events. Browse hundreds of teachers and events in one convenient location.

B stands for Breathe and Belly Check Before You Eat. Before you eat, take five deep breaths. Notice whether you have sensations of physical hunger, like mild gurgling or gnawing in the stomach. How hungry are you? What are you hungry for? Maybe you’re hungry, or maybe you’re bored, tired, or stressed. If you’re physically hungry, take your time to choose food that you can enjoy and savor. If you’re not, maybe there is something else your body is wanting, like movement or rest.

A stands for Assess Your Food. What does your food look like? Notice the colors. Does it look appealing? What does it smell like? Where does it come from? Is it whole and unprocessed, or is it highly processed? Is this the food you really want? A brief pause to assess can give you lots of information.

S stands for Slow Down. After you’ve determined that you’re physically hungry and you’ve chosen what to eat, slowing down can help you enjoy your food and be more attentive to when your body is telling you it has had enough. To slow down, put down your fork or spoon between bites, pause and take a breath between bites, and chew your food completely.

I stands for Investigate Your Hunger Throughout the Meal. Be aware of your distractions and keep bringing your attention back to eating, savoring, and assessing your hunger and satiety throughout the meal. Halfway through, you may discover you are no longer hungry, even if there’s still food on your plate. Give yourself permission to stop or to continue eating based on awareness of your hunger and satiety cues.

C stands for Chew Your Food Thoroughly. Pay attention to the multitude of sensations available to you as you chew. When you’ve chewed your food thoroughly, your body will process the food more efficiently and get more nutritional value from it. When your body has been nutritionally fed, it will tell you by dispelling your hunger cues. Chewing thoroughly also helps you to slow down and taste, improves

Lynn Rossy leads a practice to apply the BASICS of Mindful Eating to your next meal.

mindful.org/ basics

dental health, and spares your belly the discomfort of indigestion.

S stands for Savor Your Food. Food is a wonderful part of our lives. Savoring your food means taking time to choose food you really like and that would satisfy you right now, picking food that honors your body and your taste buds, and being fully present for the experience of eating and taking pleasure in that experience. Every time you sit down to eat can be an opportunity to savor. ●

Excerpted from Savor Every Bite. New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Copyright © 2021 Lynn Rossy.

When we release our tight hold on our preferences, the world can open up for us in surprising—and even delightful—ways.

By Elaine SmooklerHave you ever been utterly convinced you couldn’t stand someone? Or certain you detested a particular food, or felt strongly determined to steer clear of all people and parties, and music that doesn’t involve Willie Nelson? Then suddenly, like a bolt from heaven, someone cooks the broccoli in a new way and your preferences are challenged because, “Hey! It’s actually quite tasty.” Or you meet someone at a party and they inspire you and turn out to be a joy to talk to. Maybe someone dragged you to a hip-hop musical and, without warning, you ended up having fun.

It’s OK to have preferences. But if you’re a prisoner of your preferences, the world becomes increasingly intolerable when, inevitably, you don’t always get your way.

You can start to un-gloop the doors of sticky-stuckness by remembering that the payoff for taking a sidelong glance at your preferences might be suddenly being available for a life of freshness and surprise. Letting go of what you think you prefer might allow you to apply for jobs you didn’t imagine you’d ever choose, or bring you the courage to move to a bigger or smaller town even if you’re not entirely sure yet what you prefer. Easing up on preferences can allow for you to adapt to whatever might be on offer, which will allow you to thrive under a variety of circumstances. We can get pretty hot about who we are, who we like, and what we stand for. It’s good to have fire in our bellies. But when we cling to our likes and dislikes, they can become barriers that prevent us from more fully experiencing ourselves, each other, and the ever-changing riot of life. With practice, you can question whether a passionately held desire is actually just a preference. Perhaps one that you can or might want to let go of.

When you have the intention to notice preferences without being chained to them, you make yourself available for the dazzling discovery that there might be people, ideas, smells, tastes, and opportunities that could fit you even better.

But if you don’t recognize that many things are just preferences, and not critical to your well-being or happiness, you are going to find yourself in hell’s half acre when you discover other people want to be happy in different ways than you do. Or when some of the things you think you need to make you happy are not available.

Loosening your hold on preferences can offer a pathway to peace with others who have their own choices, some of which might have the horror-factor of not being what you want.

Will all this preference-checking be comfortable? Of course not. It will challenge you and your perceptions about yourself, and the world. Hurrah! ●

m

AUDIO

S.T.O.P. Practice

Follow along as Elaine guides us through the S.T.O.P. practice.

mindful.org/ stop

You can utilize the S.T.O.P. practice as soon as you feel yourself digging your heels in because you just have to have things your way, or when you reach out to eat, buy, or do anything without thinking. Take a moment to consider the ramifications of any preferences you exert.

STOP. Press pause, just for a moment, to give yourself permission to take a closer look at your dearly held preferences.

attention from sliding into the gloopy cow paths of habit.

Elaine Smookler is a registered psychotherapist with a 20-year mindfulness practice. She is also a creativity coach and is on the faculty of the Centre for Mindfulness Studies in Toronto.

TAKE A BREATH, and bring your attention to feeling (not just thinking about) the breath as it moves through the body. You can only feel yourself breathing in the here and now. Staying focused on the moving breath can keep your

OBSERVE. Mindfulness is a way to take the observer stance and notice, among other things, adherence to preferences that starve us of all the wondrous possibilities on offer. As keen observers we can ask: Which thoughts are pushing us around, which emotions are riding piggyback, and how is the body responding to this push-pull menu of unchallenged sameness?

PROCEED. Notice how taking an intentional gander at your familiar choices offers you a little more space to proceed with greater freedom into the adventure that lies ahead.

Small steps can lead to greater happiness, selfacceptance, and well-being. Misty Pratt debriefs on how a free, science-based app is helping her get started.

I was in my late 20s when I discovered the practice of mindfulness. Years of anxiety and depression had left me exhausted and lacking confidence in my ability to navigate the basics of adult life, but an eight-week mindfulness program was a turning point. My symptoms didn’t disappear, but I learned how to ride the waves of my emotions while tapping into a deeper calm within myself.

When marriage and kids rolled around, meditation went out the window, along with sleep, intelligent conversation, and a clean house. As my children grew older and I could do more self-care, I felt conflicted about how to use my time. Do I shower? Go for a walk? See a friend? Meditation was one item in a long list of things I needed to do to address my mental health.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Misty Pratt has been a health researcher for over 10 years and works as a research coordinator with the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. She is also a freelance writer and voice for the Ottawa blog Kids in the Capital. Misty’s research interests include mental well-being and maternal health.

In the past two decades, the science of well-being has grown. We know that “flourishing” (defined as a combination of physical, emotional, and mental health) is a state of mind where life feels good. Flourishing is not about perfection or being happy all the time, but a recognition that when we have purpose, meaning, and connection in our lives, getting out of bed every morning is easier. Life is short. We want to be fully alive and embracing every moment, even when those moments are difficult.

Most people would agree that nothing has been more challenging than living through the COVID-19 pandemic. As we churn through the frustrating cycle of opening up and then retightening COVID restrictions in the face of dangerous new variants, we may also be facing longer-term mental health impacts. For many, anxiety over returning to jobs, busy schedules, and socializing has been challenging to manage when we’re already so depleted.

Recently, I stumbled across the Healthy Minds Program, a free app that’s designed to help users develop skills in the pursuit of well-being. Drawing from the work of scientists at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the app is based on research that identifies four pillars of wellbeing: awareness, connection, insight, and purpose.

Curious, I downloaded the app and set out to try

it for 30 days to discover whether I could learn the skills to flourish in my own life.

The app begins with a questionnaire that generates a personal score for each dimension. Awareness measures things like mindfulness; connection looks at my ability to form and maintain relationships, as well as show empathy and compassion; the insight score captures things like self-knowledge and resilience; and purpose gains a sense of my values, and how I integrate them into my everyday life.

“If you want to cultivate loving-kindness and compassion, examine experience and insight, or align yourself toward your values and a deeper sense of purpose—all of that really presupposes that you have a sense of awareness and present-moment mindfulness,” says Cortland Dahl, one of the research scientists who developed the app at the Center for Healthy Minds. This emphasizes that mindfulness is more than the popular idea of sitting still and quieting the mind—mindfulness helps us develop a set of skills

that we can apply in everyday life, skills that will reduce stress and improve mental health.

I started with the Foundations program, which introduced me to each of the four themes. Two practices teach the basics of sitting and active meditation, and there is a brief podcast-style lesson about the science behind training in well-being, narrated by Cortland Dahl and by Dr. Richard Davidson, founder and director of the Center for Healthy Minds, who’s widely known for his work studying the neuroscience of emotion (affective neuroscience). Other meditation practices touch on things like relationships, inquiry into beliefs or assumptions, and how a sense of purpose can make life more meaningful. Practices are followed by mini science lessons, covering topics related to the app’s themes.

Although a daily practice is encouraged, users are welcome to set their own pace, and the app tracks your progress. Foundations is followed by longer programs on the skills of awareness, purpose, compassion, and insight. Users can also choose stand-alone meditations with titles like “Calm in the Midst of Chaos” or “Our Common Humanity.” →

Within a few days of using the app, I became aware of long-held myths that I believed about meditation and mindfulness—myths that, unknown to me, were getting in the way of flourishing.

Within a few days of using the app, I became aware of long-held myths that I believed about meditation and mindfulness—myths that, unknown to me, were getting in the way of flourishing. The soothing voice of Cortland Dahl (or “Cort,” as he referred to himself) reminded me that I wasn’t required to do this perfectly—in fact, there was no ideal way to meditate. All I had to do was show up and become aware of what was going on in my body and mind.

The stricter practices that I’d previously followed fed into my perfectionism, and when I achieved anything less (for example, sitting for 20 instead of 45 minutes), I felt like I had failed. It was an all-or-nothing approach, because I gave up unless I was doing it “right.”

The app turned these beliefs on their head, and some days I defined success as a five-minute practice while walking the dog. Most of my sitting practices were done in my bedroom, with screaming kids outside the door. It was far from serene.

Another “aha” moment came when I realized that I’d always understood well-being to be a fleeting experience over which I had little control. “The science of training the mind is all based on the idea of neuroplasticity: a fancy term that basically just means that the brain is constantly changing in response to experience,” Davidson tells me in one of the app’s lessons. “Usually the forces

around us are driving these changes, but when we train our minds we’re in the driver’s seat.”

At the end of the 30 days, I had logged six hours of practice time and two hours of learning. My follow-up report showed that my connection score stayed the same, while both awareness and purpose improved. My biggest jump was in the dimension of insight, highlighting a newfound ability to be more flexible and adaptable in the face of challenges.

Digital therapeutics like apps are promising tools in a world where so many people are struggling with their mental health. Long wait times and costly therapies make it difficult for some individuals to receive the care they need. Research is emerging on the effectiveness of the Healthy Minds app, although thus far it’s been conducted by the app’s creators. Even so, preliminary results are promising, with those randomized to the app (compared to those in a waitlist control group) showing larger improvements in recovering from distress, social connectedness, and mindfulness.

One evening toward the end of the month, I grabbed my phone and headed out for a walking practice on the theme of purpose. The narrator led me through some deep breathing and body awareness, and I relished the calming exercise after a busy day.

“Take a look around you,” he said. “What would you notice if this was your last day on earth, or maybe even your last minute?”

As I glanced up a large blue crane swooped low overhead, a startling sight in my sleepy suburban neighborhood. A magnolia tree bloomed, the colors brilliant against the pewter sky. I took a deep breath, sending out thanks for the beauty of this world, for my place in it all.

As the narrator concluded, he reminded me that life is fragile. Shifting our perspective to the present moment reminds us how quickly things can change, and this wisdom, too, is a key to flourishing. “Moments become minutes, then hours, then days; and eventually a lifetime,” says Dahl. “Every moment provides a new opportunity to connect with a deep sense of purpose and meaning.” ●

By engaging in repeated practices meant to help us increase awareness, focus on our similarities, and develop care and kindness, we might also be combating the implicit associations that cloud our judgments of other human beings.

It seems reasonable to think that, if we believe firmly that people of all racial identities should be treated equally, we won’t perpetuate racial bias. Unfortunately, our consciously held beliefs may not always align with our mental and behavioral patterns. Society, culture, media, and power structures can feed us subtle (and not-so-subtle) racist messages, and these messages, repeated over time, create associations in our minds that instill prejudice without us realizing it—even if we don’t believe these ideas consciously. This is known as “implicit bias.” We can work toward racial equity and justice through active engagement in our communities, and also in ourselves— and when we do, we need to be aware of, and work to shift, our implicit associations.

A tool scientists use to study unconscious biases is the Implicit Association Test (IAT), designed

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wendy Hasenkamp is Science Director at the Mind & Life Institute, and a visiting assistant professor at the University of Virginia. As a neuroscientist, her research focuses on how we can leverage the brain’s capacity for neuroplasticity to create healthier minds and a more connected society. She also hosts the Mind & Life Podcast.

to measure the strength of association between concepts in memory. In this computerized test, participants are asked to categorize two sets of stimuli as fast as possible according to the instructions. To probe racial bias, one must assign Black or white faces into positive or negative categories. The idea is that if someone has an implicit bias against Black people (e.g., they associate “Black” with “bad”), they will take longer to press a button to assign Black faces into a positive category. The delay is a result of the brain being slightly slower to process this grouping, because it runs counter to the existing association. Along the same lines, they would be faster to categorize white faces as positive, because this agrees with the existing association in their mind. While there are debates about how much IAT scores correlate with real-world behavior, the test remains a scientifically useful (and commonly employed) tool to probe these kinds of unconscious associations in our minds.

Studies using the IAT in US populations from Harvard’s Project Implicit consistently find evidence for pro-white/anti-Black bias. Perhaps more disturbingly, this is even the case among Black people, although the bias is less prominent than among white people. Notably, these implicit biases are not strongly correlated with people’s explicit reports of their attitudes about race, suggesting the biases operate without awareness.

Implicit biases can affect our decisions and behavior (although research shows the link →

between implicit bias and behavior isn’t consistent). In a pair of studies involving an economic trust exercise, participants who had high pro-white bias on IAT scores chose to “invest” less money in a Black partner. Implicit bias also affects healthcare: Providers’ implicit bias has been associated with racial disparities in treatment recommendations, pain management, empathy, and poorer patient-provider communication. Other work shows that in communities where people have stronger racial bias, Black people are killed by police at disproportionately higher rates, suggesting a society-level effect of implicit bias on behavior.

Evidence of racial bias is also reflected in our brains. An important early neuroimaging study scanned the brains of white Americans while they viewed unfamiliar Black vs. white faces. Researchers found not only that activation of the amygdala (a brain region associated with processing highly salient and/or threatening stimuli) was higher for Black faces than for white faces, but the level of participants’ amygdala activation was correlated with their level of implicit bias against Black people. In other words, the more implicit racial bias people had, the more their amygdala responded to Black

Mindfully Work with Bias

Explore your identity and capacity for compassion in this four-part mini-course led by Rhonda Magee.

faces. The level of amygdala response did not correlate with participants’ self-reported (i.e., conscious) racial attitudes, suggesting that the brain activity reflected unconscious processes.

It’s important not to reduce subjective experience into brain activity; what the amygdala activation in such experiments means for a participant’s experience is highly complex and remains in question by researchers. In addition, other brain systems are certainly implicated. Nonetheless, the amygdala remains a marker of interest in how prejudice might be reflected neutrally, and some recent work has replicated the link between amygdala activity and out-group bias.

What the research appears to suggest is, despite someone holding a conscious belief in racial equality, significant factors—psychological, cultural, and neural—can sway our perception and actions toward inequality. Contemplative practices, research also finds, may hold part of the answer to reducing implicit bias, through changing our deeply held mental patterns.

It is easy to move through our lives and miss the ways we subtly categorize people based on their relationship to us, their appearance, behaviors, and other external factors. These unconscious patterns and reductive labels are the fuel for our implicit biases. Mindfulness practices such as loving-kindness or compassion can help us learn to move beyond these limited, reductive labels of others by recognizing that, at base, we all want to be happy and to avoid pain and suffering. Emphasizing our common humanity helps to take us beyond the scope of our individual preferences. “In loving-kindness practice, when you say ‘May you be happy,’ you don’t necessarily mean ‘I want you to be happy.’ Rather, the sense of self is somewhat removed: You wish them well independent of your self-interests,” says Yoona Kang, research director of the Communication Neuroscience Lab at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication. →

Unconscious patterns and reductive labels are the fuel for our implicit biases.

A brand new 8-week self-directed course based on the 8-Dimensional Path of living a life of health, happiness and harmony.

With MBSR 2.0, we’ll guide you in creating your own practice of stress-reducing mindfulness.

Learn energy regulation through breathing exercises, meditation, and mindful movement, and get back that life of calm and emotional control.

We promise - you’ll find a simple, lasting way to unwind all the stresses of everyday life!

To learn more, or to register, visit

In 2014, Kang (then at Yale) conducted a study where volunteers were randomly assigned to six weeks of either practicing loving-kindness meditation, discussing loving-kindness with the same teacher but not practicing it, or a waitlist control group. Before and after the six weeks, participants took IATs intended to measure bias against Black people and homeless people. At the end of six weeks, the study found that implicit bias against both Black people and homeless people was reduced (compared to baseline levels)—only for those participants who had been practicing loving-kindness, but not for those in the other two groups. “These results were very encouraging,” Kang says, “because statistically, the implicit bias score was not significantly different from zero in the loving-kindness practice group. Of course, this was a one-time measurement and implicit bias fluctuates over time, so we can’t say it’s gone forever. But there was a strong effect.” The fact that the discussion group didn’t change suggests that merely learning, thinking about, and discussing compassion and equality may not be enough to change deep-rooted biases.

Another study, at the University of Sussex, found that just seven minutes spent directing loving-kindness toward a photo of a Black person was enough to bring about a reduction in implicit anti-Black bias. This work suggests that a very short emotional induction can change implicit bias toward a targeted group, and that generating other-focused positive emotions is important to make this shift.

Loving-kindness isn’t the only meditation practice that can reduce bias. In a 2016 study, people who engaged in 10 minutes of mindfulness meditation showed significantly less racial discrimination than controls in a trust game. In a different group, the same mindfulness intervention reduced racial bias on the IAT compared to controls, supporting evidence of behavioral changes. Further analyses suggested the reduction in implicit bias stemmed from a “weakening of [participants’] automatic associations” between these racial groups and negative ideas.

A recent study probed the ability of mindfulness training to affect the way we form automatic associations. Participants were exposed to a puff of air in the eye that was paired with a sound—not surprisingly, they quickly began to protectively blink in response to the sound alone, associating the sound with the air puff. Those who trained in mindfulness, however, had fewer of these conditioned blink responses, and a longer delay before the first such response.

A way to look within, connect better with others and make a real difference in your world.

Researchers suggested that mindfulness may allow us to be more “in the moment,” responding to each experience as fresh and not relying so much on past associations. Lead researcher Adam Hanley notes this could have major implications for negative automatic responses like those stemming from implicit bias. “I think a lot more of our behavior is conditioned than we sometimes acknowledge,” says Hanley, speaking on the Mind & Life Podcast. “Anything we practice gets automatic.”

How long might these effects last? A 2020 study trained preservice teachers for one semester in a combined mindfulness and connection (i.e., loving-kindness) practice, and monitored the effects on racial bias as measured by the IAT. Compared to standard teacher education, this intervention reduced implicit bias against child and adult Black faces—and this effect remained six months later, with no additional training. Given the powerful impact of teachers’ perceptions on students’ performance, well-being, and success, these results highlight options for meaningful shifts in teacher education.

While this research is still in its infancy, these studies point to exciting possibilities for change. Additional studies are needed to learn more about the potential long-term effects of various forms of meditation on reducing implicit bias, as well as whether these changes are reflected on behavioral and neural levels. Still, as we continue to push for social and political change, we can be encouraged to know we can also take individual responsibility for our own minds. By choosing to engage in practices that foster attitudes of equality and compassion, we can help shift the unconscious associations that drive our behavior. ●

By choosing to engage in practices that foster attitudes of equality and compassion, we can help shift the unconscious associations that drive our behavior.

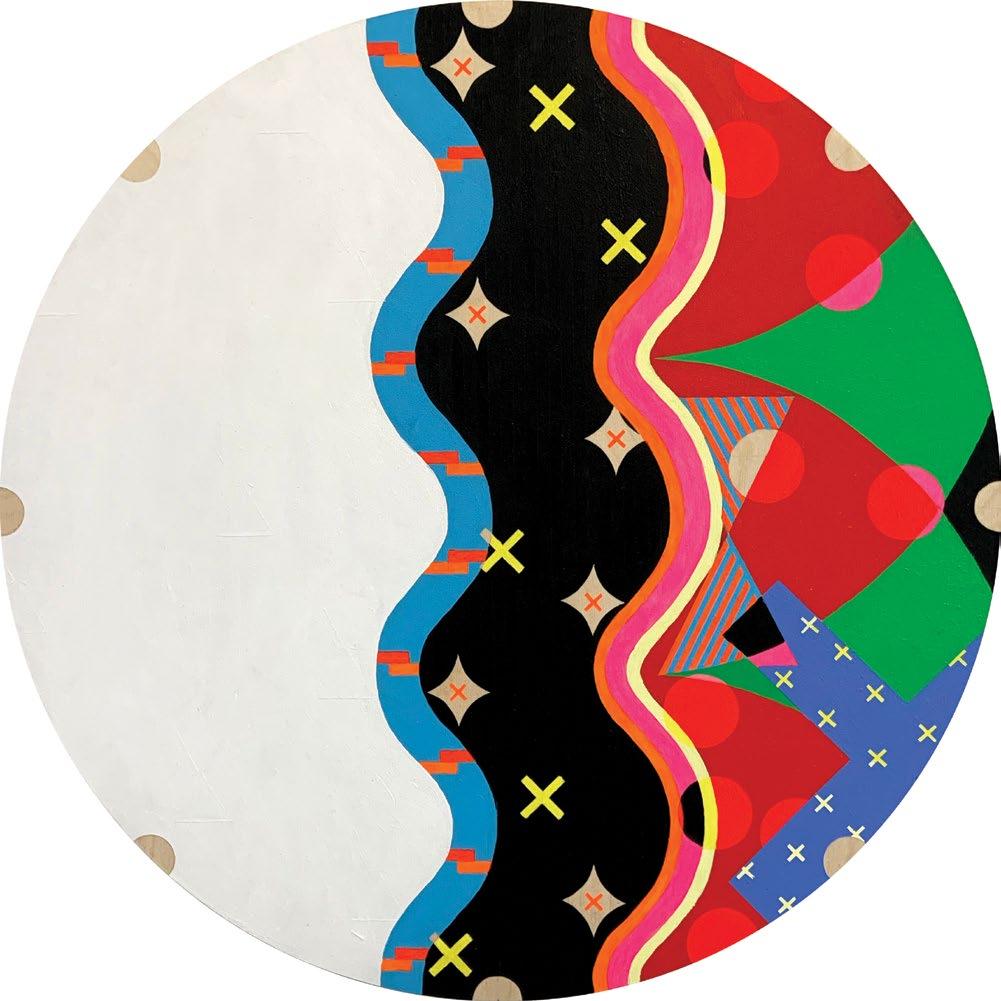

“Thank you for the love you’ve brought my way,” 2021

Painting by Jordan Bennett

Mindfulness, like the air itself, crosses boundaries of place and time, culture and community. In the intersection of mindfulness and Indigenous or tribal people there is connection to nature and to land, to relationships and community, and to the present and the past. There are the four elements of earth, water, fire, and air. There are elders and ancestors. And there are deep wounds from colonization and racism. There is displacement. There is trauma. And there is healing. There is homecoming.

In the following pages you will meet four people— Jeanne Corrigal is a Canadian Métis; Jeff Haozous, a member of the Fort Sill Apache tribe; Brenda Salgado, a first-generation Nicaraguan American; Michael Yellow Bird, a citizen of the Three Affiliated Tribes (the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara nations)—who practice, work, and live in this complex intersection.

There’s healing in acknowledging our interconnectedness. Here, four Indigenous wisdom keepers share how their practice helps them remember.

Guiding Teacher at Saskatoon Insight Meditation Community, Métis

At the heart of Jeanne Corrigal’s practice and her sense of purpose as a meditation teacher lies a sacred story. It is the tale of a little boy, lost in the Canadian bush, and the Cree elder who found him.

Corrigal, who is Métis, a Canadian of mixed Swampy Cree and Scottish ancestry, is the guiding teacher for the Saskatoon Insight Meditation Community. There she leads a weekly sit, and teaches a variety of classes, including “Indigenous Presence” and “Unwinding Whiteness,” a course that offers white students an opportunity to recognize and understand racialized conditioning.

Practicing since 1999, she trained at Spirit Rock and Mindful Schools and recently graduated from a four-year teacher training program

When I first encountered mindfulness, I thought, “This is our teaching, our Indigenous teaching of how to be in the world, how to be in connection with the world.”

with the Insight Meditation Society (IMS). Last year, she and three other practitioners led the first Indigenous Peoples Retreat offered at IMS.

“When I first encountered mindfulness, I thought, ‘This is our teaching, our Indigenous teaching of how to be in the world, how to be in connection with the world,’” she says. The daughter of a park warden, Corrigal grew up in Saskatchewan’s Prince Albert National Park. From her father, she learned lessons about nature and listening. “We would just sit at the edge of the meadow or sit by the spruce tree, not saying anything. In the early days, I wished he would talk. But in the bush, he was completely connected to everything around him. Fortunately, I eventually realized there was communication happening, without talking.”

When he did talk, Andy Corrigal told his daughter stories about Jim Settee, Cree elder, social activist, and tracker. The two men, both wardens, worked together in the park. They and other First Nation and Métis people knew well the land they had been displaced from, and their generosity and compassion showed in their willingness to assist in search and rescue when a visitor was lost in the bush. On one occasion, when a little boy went missing, Settee, considered the best tracker in the region, was off duty. Corrigal’s father assembled a search party and they fanned out, but at nightfall, the boy remained lost. Desperation intensified. The next day’s search ended without success. Finally, Settee, who lived in the Fishing Lake Métis Settlement, which he had founded for displaced Indigenous people, was asked if he would join the search.

On the third day of the search, on ground trampled by the search team, on the edge of →

JEANNE CORRIGAL

“Goodnight Circle and Bees,” 2021

“Goodnight Circle and Bees,” 2021

The elements have the ability to connect us, both internally and externally, with the world around us. Jeanne Corrigal brings her Métis heritage, and her training as an insight meditation teacher, to this guided practice to connect with the four elements within our own body.

1 Begin by settling into a sense of your body. Whether you’re sitting on a chair or a cushion, let yourself be comfortable while remaining present to the sensations of your earth body.

2 Close your eyes, if it feels comfortable. Sometimes that can let us be simpler in our attention so that we can connect more easily to the sensations. And if you want to leave your eyes open, just rest your gaze on somewhere close by so that you can simplify your attention.

3 Settle into the sensations of your earth body. Feeling the sensation of hands touching the lap or each other. The weight of the body on the chair. These physical sensations help you know that you’re here in this moment and connected to this earth.

4 Sensing the fire element: Within this earth body, you may feel heat and coolness. Feel the warmth in some areas, like the torso or chest, and coolness in your hands or feet. This temperature is the fire element in our earth body with the energy coming from the sun, directly warming the earth body, or indirectly through the nourishment of food we eat.

5 Sensing the water element: In this body, you may also feel pulsing. That is the water element in the body pulsing through a vast number of systems in the body. Feel it pulsing in your fingers, your feet, the heart, and in every cell of this alive body. Feeling it in the eyes as they move in the sockets, feeling the liquid in the mouth.

6 Sensing the air element: In this earth body, feel the sensation of the breath. The air element coming in through the nostrils, filling the lungs and lifting the chest. With this element, feel the shift of the element moving this earth body.

7 Sensing the earth element: The earth element lies in resting in this ebb and flow of the air element. Feel the air coming in and expanding the earth body before leaving and relaxing the body. Rest back and just ride the wave of this air element; realize there’s nothing you need to do.

8 When you are ready, open your eyes and take this presence to whatever you do next.

Kingsmere Lake, where the boy had last been seen, Settee stood. He was silent. Those around him grew silent too. Several minutes passed in stillness before Settee took off at a fast clip. For two hours and across miles of muskeg and bush, he tracked the boy. Settee found him, alive. No one, not even the other trackers, knew how he had done this.

“I grew up on that mystery,” Corrigal says. “Hearing that story, I imagined myself lost and Jim finding me.” Years later, then a young adult and filmmaker, Corrigal met and became friends with Settee, who had last seen her when she was an infant. And with his friendship, he helped her find her own way home.

In Settee, Corrigal saw a quality of loving presence that belonged to both the Indigenous culture she had inherited and the meditation practice she would embrace: unconditional care and love for all beings.

Jeanne Corrigal leads this four elements practice for connecting with the world inside us. mindful.org/ four-elements

“He was so mindful and so kind. He lived that completely,” Corrigal says.

In that first conversation, Corrigal asked Settee how he had found the boy. “What he told me has become a lifelong teaching for me—the teaching that brought me to meditation and the teaching I sit with, every time I sit on the cushion: ‘When I look for a lost person, I put myself into that person’s mind. Then I can pick up their trail more easily.’” The way he phrased this connected Corrigal to mindfulness, even as it touched on distinct Indigenous ways of knowing.

“When you found that boy,” she asked, “what did you do?”

Beset with fear, the boy could neither walk nor talk. “I just sat with him for half an hour,” he told Corrigal, “until he could come back inside himself.”

“When I get lost in the activity of my mind, when I get wound tighter and tighter and tighter,” Corrigal says, “if I can remember Jim and put myself in my own mind, I can pick up my trail more easily. If I can sit with mindfulness and kindness, until I can come back inside my experience, come back inside my heart. Then in that moment, I’m home.”

“Between the ocean and the shore,” 2020

“Between the ocean and the shore,” 2020

During his 16-year tenure as chair of the Fort Sill Apache, in Oklahoma, Jeff Haozous kept strict boundaries between tribal matters and his meditation practice.

One time, however, during a particularly tense council meeting, the resolve softened, and he tried to introduce a moment of mindfulness. “OK, everybody, just take a deep breath,” Haozous advised. “Take a deep breath and relax.”

A young man in the room pounded his fist on the table. “I will not relax!”

“Well, I won’t try that again,” Haozous said to himself.

But there were ample opportunities for his own practice: During another contentious meeting, when a member screamed in his face, the only skillful response was no response: “I would

breathe in and breathe out and feel their words, like a river flowing over me, while I remained centered,” he says. Another time, deeply worried about the tribe’s casino, which provides monthly revenue for members, Haozous turned to a pared-down practice of loving-kindness. “I remember driving to the tribal office, repeating ‘Safe, happy, healthy, ease, safe, happy, healthy, ease’ over and over and over again. It was the only thing that calmed me.”

His days are calmer now.

There’s a new chair. Haozous stepped down in 2018 and has moved from a public life in politics to a public life of loving-kindness practice, leaning fully into his training at California’s Spirit Rock and into his deepening role as a meditation teacher and retreat leader. During the pandemic, he and three other practitioners (including Jeanne Corrigal) led the first Indigenous Peoples Retreat at IMS, in Massachusetts. And now, after 20 years in Oklahoma, Haozous is bound for the Southwest. There, in the Cochise Stronghold in Arizona, Haozous has purchased a home, where he will connect with his ancestors and the present moment while he teaches, leads retreats, and offers—in person and online—meditation to the broader Indigenous community. “Mindfulness can bring to light and help heal the intergenerational trauma that Natives carry from the process of colonization,” he says. “Some teachers call this decolonizing the mind. I also use the term developing personal sovereignty.”

He is, in a sense, hearing—and answering—the long, silent call of his ancestors and of the land: His Chiricahua Apache forebears occupied the territory known now as southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. When Geronimo surrendered to the federal government in 1886, the Chiricahua were removed from the Southwest and subjected to 28 years of prisoner-of-war status in military installations in Florida, Alabama, and finally Oklahoma, where they arrived in 1894. In 1914, the 80 who remained in Fort Sill were released, prevented from returning to their homeland, and given modest land allotments instead. The Fort Sill Apache became an officially recognized tribe when the federal government approved their constitution in 1976.

Back then, Haozous was a teenager in Arkansas, more disconnected from than connected to his tribal identity. His father, in college, had changed his surname to Houser, an Anglicized version of the Apache word “haozous,” which means to pull up, as if by the roots. At home, Haozous absorbed a tone of atheism and a

Mindfulness can bring to light and help heal the intergenerational trauma that Natives carry from the process of colonization.

JEFF HAOZOUS

culture of science. Ties to his Apache relatives were only sparsely renewed. Decades later, after a career in direct-mail and internet marketing, Haozous left San Francisco for southwest Oklahoma—intending only a short hiatus from his business career, curious about his Apache lineage, and concerned about the small tribe’s business dealings. He felt out of place. There were shifts from the corporate culture to the tribal culture, from internet time to Indian time, from urban life to small-town, rural living. To his fellow Apache, he worried that a legal name change would look as if he were trying too hard. To the casual observer, he didn’t look the part, too white to be an Apache citizen, let alone a tribal chair.

The days are calmer now. The land speaks. The ancestors murmur. The nights reassure.

“To be in a place where Cochise lived and Geronimo and my great-great-grandfather, Mangas Coloradas, visited, is such a depth of connection,” Haozous says of his relocation to Arizona. “At night, you can see the Milky Way or you can see the beautiful granite cliffs, glistening in the moonlight. You can hear the silence. That was how our people lived. They woke before sunrise, preparing for their day and maybe praying or meditating with the morning star.”

“I think I’ve been told by my ancestors and by the land that I need to go there—for my own healing, for the healing of my people, and for the healing of the land. I’m drawn there.”

Haozous. To pull up, as if by the roots.

“I don’t know what it’s going to be, but I can see a little green sprout coming up.”

One year, when Brenda Salgado marked her birthday, she did so by honoring her ancestors. In her home, the first-generation Nicaraguan American arranged a small altar where she displayed, on posterboards, photographs of her biological ancestors, her spiritual ancestors, and her friends. And for seven days she observed a practice she’d found in a book by Thich Nhat Hanh: “In gratitude,” the Five Earth Touchings practice begins, “I bow to all generations of ancestors in my blood family.”

Gone were the days when, shopping with her mother at the St. Vincent de Paul thrift store in San Francisco, the young Catholic girl had hastened to the book section, in search of Bible stories. Although grateful for her Catholic upbringing and education, she had chafed at its limits. “The Church,” she says, “did not have room for all the ways I experienced God—or for female leadership.” It did not—it could not—hold the powerful spiritual tug that drew the contemplative Salgado past confines of institution, time, and place—drew her to the trees, to the land, to nature, and, ultimately, to her ancestors.

In a sense, that birthday celebration—in honor of her ancestors—launched Salgado on a path of homecoming, opening new and reso -

nant spiritual corridors of communication. Her maternal grandmother, who had lived and died in Nicaragua, and whom Salgado had met only a few times, began to appear to Salgado in dreams and meditations. Nudged by this ancestral voice, Salgado probed her mother and her Aunt Lydia for stories, learning that her grandmother had practiced traditional medicine, at times healing family members when Western medicine and doctors in Managua could not. “I knew, on some level, that there was medicine in my lineage,” Salgado says. “I assumed it was lost much further back, because of colonization and the loss of our language and culture. I had no idea this was something my grandmother, of Indigenous Chorotega lineage, had done.”

Over time, Salgado followed—and gradually integrated—strands of mindfulness and of traditional medicine. Having for several years attended daylong retreats at the East Bay Meditation Center in Oakland and with a background in nonprofit management, she became the organization’s first director. When she left EBMC, Salgado then edited the book Real World Mindfulness for Beginners, a 2016 collection of guidance and practices from next-generation mindfulness teachers around the country. After extensive work with Central American elders who taught her about traditional and plant medicine, Salgado studied the Toltec lineage, a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture, with its healing breath and energy work. Mindfulness, she says, prepared her for the healing work she now does full-time: “Learning mindfulness in a more secular context and then going into what was culturally appropriate for my lineage—what had been lost and what is being reclaimed—feels full circle for me, in a beautiful way.”

Now, as founder and director of Nepantla Consulting, she offers Indigenous practices, many of which restore the disconnections with land, with one another, with ancestors, with universal energies. In healing, she notes, the reach extends beyond the needs of the individual and to the collective. “We want to gift a different future to the next seven generations,” she says. “That requires us to do some healing work around the trauma of our lineage, so that we’re free and future generations are free from that.”

As for her grandmother? She is still here. Salgado dedicated Real World Mindfulness for Beginners to her—to Maria Paula Guevara Galan. “She shows up everywhere. When I attend ceremony and see an elder, they say, ‘There’s a woman standing behind you, a small woman.’ And I say, ‘That’s my grandma.’”

Learning mindfulness in a more secular context and then going into what was culturally appropriate for my lineage—what had been lost and what is being reclaimed—feels full circle for me, in a beautiful way.

BRENDA SALGADO

An educator and linguist explains the mindfulness concepts nested in his ancestral language.

By Jane AffleckFor James Vukelich Kaagegaabaw, an educator and linguist who lives near Minneapolis, Minnesota, learning his ancestral language of Ojibwe has been “a fascinating story about myself that had never been told”—an opportunity to connect to his culture in a way that was previously unavailable to him. He began learning Ojibwe about 20 years ago at age 25, from elders including Dr. Rick Gresczyk Gwayakogaabaw at the University of Minnesota, and the late Dr. Dan Jones Gaagigebines and Dr. Dennis Jones Pebaamibines (both originally from Nigigoonsiminikaaning First Nation, in what is now northwestern Ontario, Canada).

Now, Kaagegaabaw is keeping his language alive by posting an Ojibwe Word of the Day on social media, featuring the pronunciation of an Ojibwe word, with illustrative images—such as “Ode’imin” (“strawberry”), “Wiikonge” (“S/he gives a feast”), and “Iskigamizige” (“S/he boils sap”).

In longer weekly videos, Kaagegaabaw offers a basic translation, along with an explanation about how the philosophical and spiritual aspects of the words are connected to the cultural practices of Ojibwe and other Anishinaabeg peoples, such as the Chippewa, Odawa, and Menominee. So while Ojibwe words reflect the Seven Grandfather Teachings, as Kaagegaabaw explains, “They are not just abstract concepts, they are things you do —parts of a holistic lifestyle that aligns our thoughts and actions toward living in a balanced way.” Consequently, these words may provide fresh perspectives for other kinds of practice-based living, such as mindfulness.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

When the elders were teaching him about the stars, James Kaagegaabaw says, they asked him, “Can you possibly know the names of all the stars?” Kaagegaabaw found the question insightful. “It is impossible,” he says, “so it shows that our thoughts and our language have limits. The truth is much too vast; I don’t know the whole truth, I can speak only from my own perspective or knowledge.

‘Lying’ in Ojibwe is not ‘dishonest,’ but rather, ‘he/she misleads with speech.’”