Transform Your Life

JUNE 2021 mindful.org

+

JOURNEY

GRIEF

a

What neuroscience says about how you create your reality ABUNDANCE Embrace what you have and tap into true joy

A

THROUGH

What you can learn from

broken heart PSSST— GUESS WHAT? How gossip works for the greater good

Nourish Your Connection to Joy

When you understand the power of your predicting brain, writes Lisa Feldman Barrett, you unlock the ability to transform the way you experience your life.

p.58

ILLUSTRATION BY JAYE KIM / ADOBESTOCK

June 2021 mindful 1

CONTENTS THE ABUNDANCE ISSUE

On the Cover 28 ABUNDANCE Embrace what you have and tap into true joy 30 PSSST—GUESS WHAT? How gossip works for the greater good 44 A JOURNEY THROUGH GRIEF What you can learn from a broken heart 58 TRANSFORM YOUR LIFE What neuroscience says about how you create your reality Your Brain Predicts (Almost) Everything You Do Lisa Feldman Barrett on how our brains’ predictions create our reality. Sea Change The depths of grief can open us up to compassion, writes Bryan Welch on the value of a broken heart. 58 44 34 STORIES 20 Mindful Living Sewing Lessons 24 Health Rebalance Your Energy Levels 28 Inner Wisdom Feeling Lonely in a Sea of Love 30 Brain Science What Makes Good Gossip EVERY ISSUE 4 From the Editor 6 In Your Words 10 Top of Mind 18 Mindful–Mindless 68 Bookmark This 72 Point of View with Barry Boyce ILLUSTRATIONS BY JAYE KIM / ADOBESTOCK, JORM S / ADOBESTOCK, RALH MOHR / PLAINPICTURE The Fine Art of Failing Failure doesn’t have to hold you back, writes Katherine Ellison —instead, it can be a practice of accountability. 2 mindful June 2021 VOLUME NINE , NUMBER 2, Mindful (ISSN 2169-5733, USPS 010-500) is published bimonthly for $29.95 per year USA, $39.95 Canada & $49.95 (US) international, by Mindful Communications & Such, PBC, 515 N State Street, Suite 300, Chicago IL. 60654 USA. Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Mindful, PO Box 469018, Escondido, CA 92046. Canada Post Publication Mail Agreement #42704514. CANADIAN POSTMASTER: Send undeliverable copies to Mindful, 5765 May St, Halifax, NS B3K 1R6 CANADA. Printed in U.S.A. © 2021 Mindful Communications & Such, PBC. All rights reserved.

US

We’re bringing our content to life with Mindful Live —a series of in-depth, online conversations, and events featuring mindfulness experts on how we can enjoy better health, cultivate more caring relationships, and create a more compassionate society.

Sign up to learn more at mindful.org/mindful-live

The Light Gets In

This past year has been hard. Currently, I have a torrent of gnarly emotions stashed behind a mental dam that I’m not fully dealing with—the dam cracks a little each time I acknowledge it so I’m choosing not to look at it for very long. I’m saving it for…later. For now, I’m channeling my discomfort into my own form of aggressive yoga (there are pushups), and practicing body scan meditations to check in with my body along the way.

In my mind I believe I’m letting my emotional dam release in a scheduled fashion: acknowledging it’s there, providing some safe spillways for processing, some tunnels for inspecting any damage, a few postcards in the gift shop for tourists. But I know this is not the way emotions like to be treated.

You may want to ask me: If you recognize this, why are you doing it to yourself? The answer is: because that’s just the way it is right now. I’m choosing to be kind to my stubborn unwillingness and forgive myself for not wanting to look at the hardest stuff right now. I know resistance is futile. Change is inevitable. And pain is certain. But thankfully, kindness, forgiveness, and compassion show up anyway.

For this June issue of Mindful magazine, we’ve gathered together a host of wise and flawed characters to share their stories of pain, joy, and wisdom with you. On page 40 Vinny Ferraro offers a practice on compassionate accountability for when you’re the one causing harm. Dr. Sará King (page 14) shares her work connecting mindfulness, social justice, and inherited trauma. On page 58, psychologist and neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett offers a glimpse into how our brains predict our reality. And on page 44, our CEO Bryan Welch shares one of the most brave and vulnerable, raw and real essays I’ve ever read about the depths of suffering and deep wells of compassion that can come from a broken heart.

Heather Hurlock is the editor-in-chief of Mindful magazine and mindful.org. She’s a longtime editor, musician, and meditator with deep roots in service journalism. Connect with Heather at heather.hurlock@mindful.org.

As I was editing this issue, Leonard Cohen’s famous words kept coming to mind: Ring the bells that still can ring, Forget your perfect offering, There is a crack, a crack in everything, That’s how the light gets in. May we all find ways to turn toward our pain and suffering, accept our cracks, and acknowledge our walls—remembering that there’s joy, love, and abundance to be found even in our brokenness, simply because we’re alive.

JOIN

JOIN

live 4 mindful June 2021

from the editor

PHOTOGRAPH BY CLAIRE ROSEN

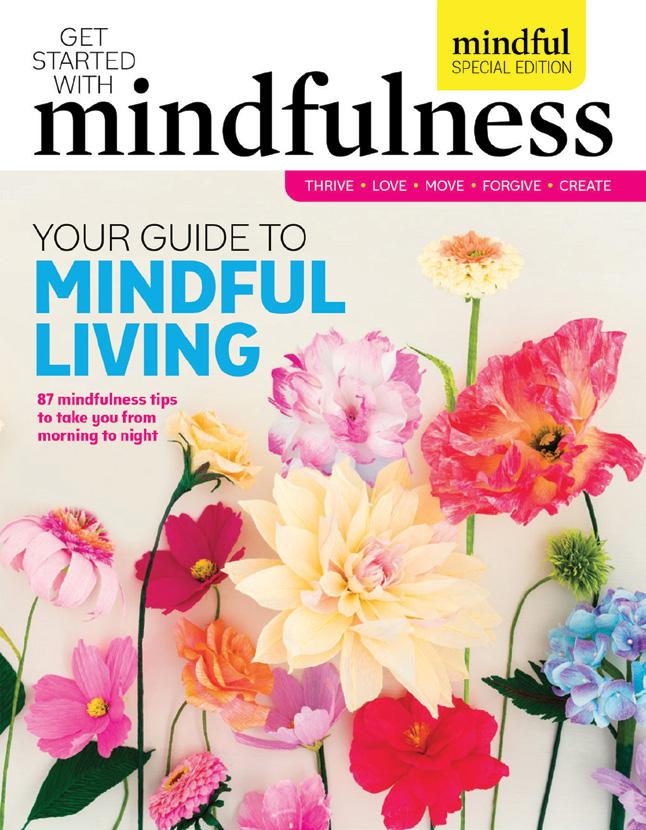

Order today mindful.org/guide-mindful-living SPECIAL EDITION Thrive, Forgive, Create Available at mindful.org/shop and wherever magazines are sold. Learn to nourish connection, embrace compassion, and tune into your true intentions with the latest special edition from the editors of Mindful. NEW!

Let’s Get Real

How each of us lives authentically is as unique as our fingerprints. Here’s what it means for Mindful readers.

What does it mean to be authentic?

“To accept myself with love and compassion, and follow my path with joy and gratitude.“

Candace Z.

“It means to be honest about what’s in my head and heart, but in a way that’s mutually respectful and productive.”

willingham2271

“My definition of authenticity is to be who you are, no matter where you are or who you are with. Truly yourself at all times.”

Marlene F.

How do you show up for yourself?

“When my body tells me ‘enough for now,’ I listen, I stop, and then I rejuvenate.”

herwithin

“By being present.”

instajmarsh

Does mindfulness help you be your true self?

← @megan.burnside made vision boards inspired by @balancewithburnside featuring artwork from Mindful

“I think it’s when you’re unfiltered. You’re truly yourself. And you are living into your core values. You’re not trying to fit in or impress anyone. You willingly show your imperfections and vulnerabilities without shame or guilt.”

Claire L.

“Staying true to yourself <3” m0rethan.fitness

“Authenticity is when our words, our thoughts, our actions, and our emotions are in alignment.”

wellnesswithbryce

96% YES

← @chillchief says her mindfulness practice has helped her embrace anxiety and stay in the present.

4% NO

Next Question…

How has the meaning of connection changed for you?

Send an email to yourwords@mindful.org and let us know your answer to this question. Your response could appear on these pages.

6 mindful June 2021 in your words

THRIVE & SHINE

SWEEPSTAKES

Enter for a chance to win an intimate prize package of self-care essentials—designed to make you feel your best self this summer!

Mindful Movement for Strength, Clarity and Calm

Prize package includes:

• meaning to pause® handcra ed bracelet

• Radiant Rest by Tracee Stanley from Shambhala Publications

• Lifetime subscription to HappiSeek + Apple’s new AirPods Max

• 1-hour, virtual private Mindfulness Meditation session with Ellen Patrick, a Yoga Therapist and Mindfulness Meditation teacher

• Turmeric Energizing Treatment from Eminence Organic Skin Care

• Mindful Movement Course

Enter online by July 31st, 2021 for your chance to win!

mindful.org/thrive-and-shine

Editor-in-Chief

Heather Hurlock heather.hurlock@mindful.org

Managing Editor

Stephanie Domet

Senior Editors

Kylee Ross

Amber Tucker

Associate Editors

Ava Whitney-Coulter

Oyinda Lagunju

MINDFUL COMMUNICATIONS & SUCH

Founding Editor

Barry Boyce

Creative Director

Jessica von Handorf

Associate Art Director

Spencer Creelman

Junior Designer Paige Sawler

Mindful is published by Mindful Communications & Such, PBC, a Public Benefit Corporation.

Chief Executive Officer

Bryan Welch bryan.welch@mindful.org

Chief Financial Officer

Tom Hack

Accounting

Kyle Thomas

Director of Technology

Michael Bonanno

Manager of Information Systems

Joseph Barthelt

Director of Human Resources

Lauren Owens

Director of Client Services

Monica Cason

Client Relations Assistant

Abby Spanier

Administrative Assistants

Deandrea McIntosh

Audhora Rahman

President

Brenda Jacobsen brenda.jacobsen@mindful.org

Founding Partner

Nate Klemp

Vice President of Operations

Amanda Hester

Vice President of Marketing

Jessica Kellner

Director of Marketing

Leslie Duncan Childs

Director of Events

Julia Sable

Head of Coach Development

Chris Peraro

Advisors

Alan Nichols

Larry Sommers

Kate Wolin

Content Licensing

Mary Jo Reale MJ@mindful.org

Board of Directors

David Carey, James Gimian, Brenda Jacobsen, Eric Langshur (Chair), Larry Neiterman, Bryan Welch

ADVERTISING INQUIRIES

Advertising Director

Chelsea Arsenault Toll Free: 888-203-8076, ext 207 chelsea@mindful.org

CONTACT / INQUIRIES

Publishing Offices 5765 May Street Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3K 1R6 Canada mindful@mindful.org

Corporate Headquarters

515 N. State Street, Suite 300 Chicago, IL 60654, USA

Advertising Account Representative

Drew McCarthy Toll Free: 888-203-8076, ext 208 drew@mindful.org

Editorial Inquiries

If you are interested in contributing to Mindful magazine, please go to mindful.org/submission-guidelines to learn how.

Customer Service

Subscriptions: Toll free: 1-855-492-1675 subscriptions@mindful.org

Retail inquiries: 732-946-0112

Moving? Notify us six weeks in advance.

We are dedicated to inspiring and guiding anyone who wants to explore mindfulness to enjoy better health, more caring relationships, and a more compassionate society. By reading Mindful and sharing it with others, you’re helping to bring mindfulness practices into the world where the benefits can be enjoyed by all. Thank you!

Welcome to mindful magazine • mindful.org Get More Mindful Print magazine & special topic publications 30 Day Mindfulness Challenge Healthy Mind, Healthy Life Mindfulness video courses FREE! Guided meditations & podcasts Visit online at mindful.org

8 mindful June 2021

has an app for that. Tinnibot is an online chatbot that supports those suffering from tinnitus through the use of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, mindfulness, and sound therapy. It features lessons based on relaxation and meditation, on how to transform negative thoughts and increase resilience. It also provides users with access to online counseling with a psychologist.

A LITTLE MORE CONVERSATION

TOP OF mind

DRAW ON

Nova Scotiabased graphic designer Melissa Lloyd founded Doodle Lovely in 2016 to draw our attention to the

here-and-now— creatively. In addition to a range of guided doodle journals and workbooks, in 2020 Lloyd also began facilitating Doodle Breaks:

guided sessions for organizations (over Zoom or in person), which she’s already brought to clients in the tech sector, first responders, and other highstress environments. Her years of mindfulness practice inspired her to study how putting pen to paper connects us to our natural

awareness—which encourages judgment-free, creative thinking, notes Lloyd. “If you can take even 5 minutes for a healthy break, that’s where all those ‘a-ha’ moments happen,” Lloyd told Mindful. “It’s about bringing the person into the present moment through the doodling process.”

NOW HEAR THIS

The constant ringing or buzzing in the ears that is the hallmark of tinnitus can present itself as a low-level annoyance in some cases, but multiple scientific studies reveal that people with tinnitus have an increased risk of anxiety and depression. And while the Mayo Clinic notes that often tinnitus can’t be treated and must instead be endured, an Australian start-up

Necessary conversations about race don’t stop when the hashtag stops trending, or at the end of Black History Month. But Black, Indigenous, and people of color often carry the burden of educating their white peers.

Professors at two Nova Scotian universities, Dr. Ajay Parasram and Alex Khasnabish, invite white-identifying students to a monthly drop-in where they can ask questions about the complex race dynamics within society. “I just want everyone to reap the benefits

Keep up with the latest in the world of mindfulness.

Keep up with the latest in the world of mindfulness.

PHOTOGRAPH

BY VIACHESLAV IAKOBCHUK / ADOBESTOCK, TEO ZAC / UNSPLASH

of safe intellectual space,” Dr. Parasram told his university’s newspaper, “but in order to build that, white people need to deepen their understanding of how race operates.” The first session of Safe Space for White Questions, held in person on campus, had only a few students in attendance, but when the session moved online, more than 200 students attended.

BRAIN TRAINING

One positive outcome of the pandemic: increased conversations about mental health. For Dr. Richard Davidson and his colleagues at the Center for Healthy Minds, University of Wisconsin-Madison,

2020 provided an opportunity to look for strategies for increasing mental wellness and resilience—even for those who are not experiencing mental illness.

Our brains are plastic, able to modify and rewire. When the brain is faced with challenges, it adapts and overcomes. With this in mind, Davidson and his colleagues Dr. Christy WilsonMendenhall and Dr. Cortland Dahl developed a framework they call The Plasticity of Well-being. The framework is built on four pillars: awareness, connection, insight, and purpose, all of which, the study’s authors say, can be developed through mental training. They hope the

framework will be broadly used by therapists, meditation teachers, and healthcare professionals.

CALL FOR CALM

In an effort to inspire joy in the midst of pandemic-induced gloom, Canadian artist and musician Kathryn Calder set up a hotline people can call to hear soothing sounds. You can dial 1-877-2BECALM to choose from nine different recordings, from children’s laughter, to Indigenous stories, to a guided relaxation meditation. Calder is Victoria, BC’s artist in residence and says she was inspired by a directive often repeated by her provincial health officer: “to be calm.”

ACTS OF kindness

GOLDEN OLDIE

Calgary’s Donny Marchuk says that in tough times, his elderly golden retriever, Sully, was there for him. Now, he’s repaying the favor. Sully can’t get around like he used to, so Marchuk pulls him on hikes in a wagon he calls an “adventure chariot.” He says an added benefit is that it makes other people smile to see them.

demand due to the pandemic. Community Loaves is a volunteer network of about 500 bakers. The home bakers are urged to keep one of every four loaves for themselves as thanks for their work.

PROOF OF LOVE

Seattle home bakers donated over 1,300 loaves of bread to a local food bank that’s seen increased

ALL CLASS

British Columbia MLA Ravi Kahlon tweeted about a proud dad moment when his 10-year-old son asked a new kid in his class to hang out. At the end of the day, Kahlon’s son received a note from his new friend that said sitting with him “felt better than anything,” thanked him, and asked to do it again. The note features a drawing of a rainbow.

June 2021 mindful 11 top of mind

PHOTOGRAPH BY ALEX / ADOBESTOCK

Research News

by B. GRACE BULLOCK

CONCUSSION CARE

Each year more than 2 million Americans suffer from chronic difficulties like headaches, anxiety, and trouble focusing following a concussion. Researchers at the University of Connecticut reviewed 22 studies where mindfulness-based interventions were used to treat symptoms related to these mild traumatic brain injuries. They found that meditation and yoga helped to lessen fatigue and depression, and improved mental and physical health, cognitive performance, and quality of life.

More studies are needed to better understand these effects.

NO SILVER BULLET

Mindfulness programs are widely used to reduce stress in nonclinical settings, and practices like meditation and yoga are known to lessen symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression and increase well-being. These effects are far from universal, say Cambridge University researchers after examining 136 randomized controlled trials of mindfulness interventions. Some studies reported reductions in stress, anxiety, and depression, while others showed little to no effect. The take-home:

Mindfulness practices may work for some, while strategies like physical exercise may be just as effective for others. The researchers note it’s important to assess which types of mindfulness practices will work best for different communities.

MIND OVER MUSIC

Interested in heart-rate variability as a biomarker of stress resilience, researchers from the University of Southern Denmark randomly assigned 90 adults to 10 days of 20-30 minutes of either app-based

Research gathered from University of Connecticut, Cambridge University, University of Udine, and others.

12 mindful June 2021 top of mind

mindfulness training, listening to music, or a control group that did nothing. All participants had their heart rhythms continuously monitored. After 10 days the mindfulness group reported greater increases in mindfulness, less perceived stress, and fewer breaths per minute than the other groups. The mindfulness group also

stress, anxiety, and depression

as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic according to recent studies, researchers in Italy wondered whether meditation might help. Sixty-six female teachers participated in a study, attending an 8-week meditation course and completing a personality profile that classified them

LOVE IN

showed increases in heart-rate variability, suggesting an enhanced ability to cope with life’s ups and downs.

TEACHER FEATURE

With women at greater risk than men for developing symptoms of

as either high or low resilience. After the course, both groups reported less anxiety, depression, and emotional exhaustion, and greater empathy, body awareness, and mindfulness. Those in the low resilience group showed greater reductions in depression and improvements in well-being than their higher resilience peers.

Is mindfulness or relaxation training helpful for romantic relationships? European researchers wanted to know. They randomly assigned 989 couples to either a mindfulness group or a relaxation group. Couples ranged in age from 21 to 83 years old and had been in relationships for an average of 23 years. Mindfulness training involved daily 10-minute audioguided exercises that included paying attention to posture and breath, directing attention to experiences, and being aware of thoughts and feelings during interpersonal interactions. The relaxation group completed 10-minute daily guided relaxation exercises. At study’s end, both groups reported similar levels of relationship well-being, suggesting that either strategy might be useful for relationship health.

The mindfulness group showed increases in heartrate variability, suggesting an enhanced ability to cope with life’s ups and downs.

June 2021 mindful 13 top of mind

Dr. Sará King

THE SCIENCE OF SOCIAL JUSTICE

Dr. Sará King has an idea she wants you to hear: Wellbeing and social justice are the same thing. King is a neuroscientist, medical anthropologist, and meditation teacher. She founded MindHeart Consulting and is a postdoctoral fellow funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at Oregon Health Science University, where she brings together her work in neuroscience, mindfulness, and social justice in a framework she calls The Science of Social Justice.

She wants people to understand that the effects of oppression and injustice manifest in our bodies and minds. Since trauma affects our physiology, psychology, mental health, and relationships, King says understanding that the pain permeates so many parts of ourselves helps us heal.

“When you integrate science and mindfulness and social justice, suddenly people understand that they have an incredible

amount of power to enact positive change,” King says. She has partnered with companies like Google and Nike, multiple universities, and the Museum of Modern Art to facilitate trauma healing circles and meditations based on the Science of Social Justice. This increased attention and interest in her work is fueled by recent cases of police violence against Black people, and the tremendous shift we’re seeing as more people work to come to terms with how the trauma of systemic racism and violence is passed down through generations. And though she wishes that people weren’t in the state of intergenerational pain that makes her work so relevant, she sees the beginning of a shift in how we understand the relationship between awareness and injustice.

King’s goal is that “no matter what your education level, no matter where you’re from, you have access to really understanding how much power you actually have in justice.”

14 mindful June 2021 PHOTOGRAPH

top of mind

PEOPLE TO WATCH

PROVIDED BY SARÀ KING

IT’S ALL RELATIVES

Like charity, mindfulness may well begin at home. Here are some of the latest online resources for families.

Sober Mom Squad was born when Emily Lynn Paulson, a recovery coach and mother of five, realized in the early days of the pandemic that “there wasn’t a specific support for moms who also happened to be navigating an alcohol-free life.” Welcoming all moms at any stage in their sobriety, the Squad dispels the idea that “mommy juice” is required to unwind: “Daily gratitude journaling, meditation, exercise, listening to music or shutting down technology are solid ways to regroup without alcohol,” says Paulson. The Squad hosts daily virtual meetings, a members’ forum, and a book and podcast resource library.

myKinCloud, styled as a “family mindfulness app,” offers a variety of mindfulness and yoga practices that members can access, and then post about what they did on their family’s private feed. The intention is to strengthen bonds within families, through sharing each other’s mindfulness journeys. It’s available for both Apple and Android devices.

Mindful Life Project also has an app—it’s free, ideal for families with younger children, and bilingual in English and Spanish. In both languages you’ll find a definition of mindfulness and its benefits, as well as an impressive menu of “sits” (guided audio practices) in categories such as Listening, Breathing, and Body Awareness. Most practices are under 5 minutes long and are led by MLP’s founder, JG Larochette, and other MLP teachers.

NAME IT to TAME IT

Pandemic Fine

HELLO mynameis PandemicFine HELLO my name is PandemicFine HELLO mynameis PandemicFine

this: Take a moment for gratitude. Focus on one thing per day that you’re grateful for, and feel the experience of gratitude in your body. Practicing gratitude strengthens our relationships and bolsters mental health.

recent viral tweet offered this definition: “A state of being in which you are employed and healthy during a pandemic but you’re also tired and depressed and feel like trash all the time.”

Try

A

June 2021 mindful 15 top of mind

PHOTOGRAPH BY DAIGA ELLABY / UNSPLASH, JIMMY DEAN / UNSPLASH ILLUSTRATION COURTESY MYKINCLOUD

TRUE

HAPPINESS COMES FROM YOUR HIGHER SELF

By Board-Certified Hypnotherapist & HappiSeek Co-Founder, Cynthia Morgan

An authentic life is a happy life. When we follow the world’s cues, we move farther away from our authentic self—that wise, all-knowing part of ourselves I like to call the “higher self.” Your higher self knows you well. It recognizes your highest good in any situation and always has your best interests in mind. Unfortunately, we don’t often listen to our higher self, and, as a result, we find ourselves unhappy. The solution? Go within. Quiet your mind and find yourself moving closer to your source of true happiness.

The path to sustained happiness is an inward journey, not an outward excursion.

We created the HappiSeek app to help you access your own inner guide, reach self-realization, find true happiness and make the world a better place.

GO DEEPER WITH HYPNOTHERAPY

There are many self-help meditation apps on the market that play soothing sounds and lull you into a wispy place, which is all fine and good. But what makes the new HappiSeek app unique is its combination of powerful spiritual hypnotherapy, support of a virtual community and cutting-edge technology to create an interactive journey to spiritual enlightenment.

HappiSeek is based on ten characteristics that all enlightened people commonly share, like trust and patience, which you too will develop through a series of 30 sequential hypnotherapy sessions. Along the way, you will connect with your higher self, explore your life purpose, reframe your past, find forgiveness, discover sustained happiness and so much more!

ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE PALM OF YOUR HAND

The HappiSeek app is available for both iOS and Android systems and subscriptions are $17.99/ month, $99.99/year, and $199.99 for a lifetime subscription. Download the app today and enjoy a free 38-minute revelatory hypnotherapy session. Your journey awaits, seeker.

Rooms for IMPROVEMENT

Corporate giants have been making the switch from cubicles to open concept offices over the past decade. A recent case study in the Journal of Environmental Psychology found that an increase in distractions from being in an open work environment can impair collaboration and increase stress. While mindful moments can be woven into any milieu, some companies are going out of their way to create stylish meditation spaces that take “alone time” at work to a new level. (No word yet on a meditation pod that works for Zoom meetings, though.)

HappiSeek.com 16 mindful June 2021 top of mind

OpenSeed has designed an egg-shaped meditation pod made of a sound-isolating wood and wool-felt shell. LED lights programmed to synchronize with guided audio meditations and calming sounds, an essential oil diffuser, noise-canceling headphones, and a touch screen to operate its functions make for a luxurious and private spot for a quick office cry.

The Immersive Spaces Series, an ongoing project by Office of Things, explores the effects of light, space, and sound through their meditation chambers—several of which are installed in the Google and YouTube corporate offices. Each chamber offers a calming experience heightened by sleek design elements, gentle sounds, and soft fuschia, blue, purple, and pink light.

Wake up to the fullness of your life and engage in a powerful practice of deep relaxation and transformative selfinquiry with this essential, introductory guide to yoga nidra.

Rainbow Arches —a brand focused on meditation and therapy—contracted BEHIVE Architects to design their flagship-store-headquarter-office hybrid in Shanghai, China. An open oval-shaped meditation salon is used as a meditation room for customers and employees or as a meeting space for staff, and can function as an entertainment or activity hall.

A comprehensive approach to healing anxiety with relatable stories and accessible practices to help you fi nd more peace by working with your body, mind, and spirit.

The ultimate holistic health guide to achieving overall physical, emotional, and mental well-being through herbalism and a reconnection to nature.

TIMELESS • AUTHENTIC • TRANSFORMATIONAL SHAMBHALA.COM

June 2021 mindful 17

PHOTOGRAPHCOURTESY OFFICE OF THINGS, OPEN SEED, RAINBOW ARCHES

MINDFUL OR MINDLESS?

by AMBER TUCKER

Endangered

Thai elephants are safe in rescue worker Mana Srivate’s care: He revived a wild baby elephant using CPR after it was struck by a motorcycle (the rider wasn’t badly hurt). After a medical check, the baby was reunited with its mother.

A young, healthy man in the UK was surprised to get a priority appointment for a coronavirus vaccine shot. When Liam Thorp called to find out why, he learned medical records mistakenly had his height at 6.2 centimeters rather than 6 ft 2, making his body mass index 28,000—which puts him in a weight class alongside heavy machinery. Speaking of class, Thorp turned down the appointment, and will wait his turn.

In Salt Lake City, Utah, Darin Mann invited unhoused people to camp on his front lawn. While he told ABC News he thinks the city should step up to help, in the meantime he allowed 10 tents on his lawn, and opened his bathroom to the folks sleeping in them.

Monesk, a new startup, aims to support artists while helping more people access and savor (tiny) works of art. A monthly subscription (under $10) gets you a 4x6” print, a description, the artist’s bio, and a set of reflection questions.

The pants-free set will have to stay put this year. The “No Pants Subway Ride,” an annual performance-art event put on by NYC-based collective Improv Everywhere, has been cancelled due to COVID-19.

“Wellness drinks” are trendy concoctions that boast natural (in theory), medicinal ingredients. One such beverage brand, Moment, proclaims its products can “increase alpha brainwaves…just like meditation.” Bottoms up? ●

Our take on who’s paying attention and who’s not

MINDLESS 18 mindful June 2021 top of mind

MINDFUL

Mindfulness for Healthcare

FREE Online Summit May 20-23

Join leaders in the healthcare field, healthcare workers, and experts in mindfulness to explore the many ways mindfulness practices can support individual well-being, compassionate patient care, and an equitable and inclusive healthcare system.

Free event! Register today at mindful.org/healthcaresummit

Exploring the benefi ts of mindfulness and meditation together.

SEWING LESSONS

How to align with your values, love yourself more, and have a truly intentional wardrobe, just by taking fashion into your own hands.

I love clothing. And shopping. But shopping for clothing has rarely been a pleasure. I’ve always been hard to fit—short and fat, with a large differential in my waist and hip measurements. So pants that fit my hips gape at the waist and trail well past my feet, needing to be shortened or cuffed six or seven inches. Tops that fit my bust are loose in the shoulder and long in the sleeve. And because fast fashion—the clothing available in every store in your local mall—has been the most accessible to me, because of budget and size constraints, I have always come home with what fits well enough, rather than what expresses my style or matches my values.

As I’ve become a more conscious consumer— preferring to support small businesses in my neighborhood over multinational chains, seeking out local farmers to supply my fruits and vegetables, meat, milk, and cheese, choosing companies that treat people and the environment well for goods I can’t find a local supplier for—I’ve been stymied that my clothing remained an outlier.

Until, that is, I learned to sew.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A Stitch In Time

I learned to sew in 2016, at a little fabric shop and sewing studio around the corner from my house. I took a beginners’ sewing class, and learned to make an infinity scarf. That first project was uneven, with seams that didn’t totally lie flat, but it led to many more (everyone got an infinity scarf for their birthday that year), and I was hooked. I took an easy alterations class and learned how to shorten the pants that were always too long for me. I took more classes, spent more time practicing, and eventually began making my own garments. Five years after that first class, I now have an entirely handmade wardrobe, from undergarments to jeans, to outerwear including a rain jacket, and a winter coat made from cozy boiled wool. From a wardrobe point of view, not only do my handmade clothes fit, they are in the color, print, and fabric quality of my choosing. I know how and where they were made—and just how much time, effort, and skill go into something as simple as a T-shirt, as ubiquitous as a pair of jeans, as essential as a rain jacket. Even when my sewing isn’t as careful as it could be, I know I’m still going to emerge with something better than what I could get at the mall—better in every way.

Sewing is the ultimate in slow fashion. Every part of it requires time and atten-

By Stephanie Domet

Stephanie Domet is Mindful 's managing editor, and the author of two books. She lives in Halifax, where she sews all her own clothes.

mindful living 20 mindful June 2021

tion, and a willingness to explore the minutiae of the garment at hand. When you sew for yourself, you engage deeply with the reality of your body as it is. That waist-hip differential becomes not a problem with your body, but a bit of math and a few pencil strokes on tracing paper to grade a pattern between sizes. A small shoulder or full bust adjustment happens without judgment, but simply with acknowledgment: This is what is, this is what’s needed. When I sew, I am less in conflict with reality, and spend much less time staring sadly into a mirror wishing things were different, or feeling bad about myself. Instead, I feel empowered to give my body what she needs—clothes that don’t gape, or dig in, or fall down, or feel like they were pulled from someone else’s wardrobe.

And while sewing for myself is practical, it also has the happy result that I am almost always wearing exactly what I want to be wearing, with lots of room for flights of fancy. Though I now work (and grocery shop, and attend events, and visit with family, and everything else) from home, my sewing throughout these pandemic days has tended toward dramatic sleeves and luxurious fabrics—even though no one sees me in person but my spouse these days (who very happily snaps the photos that help me document my makes on Instagram). →

Material Gains

You can learn a lot about life—and mindfulness— when you use your hands to create.

One

Creativity Is for Everyone and it feels great. Kids know this, but adults often forget: Making stuff is really fun. And if fun isn’t motivating enough for you, working with your hands on a creative endeavor also reminds you of your capacity for problem solving, ingenuity, and resilience. Plus, it underlines how capable you actually are— which can be hard to keep in focus in a world where we can sometimes feel at the mercy of forces larger than ourselves.

Two

Attention Is Key: There is no multitasking in the sewing room. When you’re pressing fabric, press fabric. When you’re sewing a seam, sew a seam. Bring your full attention to the task—and the moment—at hand, and you will be richly rewarded.

Three

Mistakes Are Not Permanent, and they’re not a referendum on your worth as a person. Anything that’s been stitched can be unstitched and stitched again. And if you can’t rip it out and start again, get curious about it. Sometimes errors lead to lovely design features.

Four

Anything Is Possible, or, when you thought you’d have enough fabric for pants, but you only have enough for shorts. If shorts aren’t part of your wardrobe plan, maybe that linen could find new purpose as a top instead. In the sewing room, as in life, our plans don’t always work out the way we intended. Being unattached to outcome is as useful in your approach to crafting as it is to living.

June 2021 mindful 21

PHOTOGRAPHS BY NEW AFRICA / ADOBESTOCK, SHINTARTANYA / ADOBESTOCK

SHOP

I haven’t purchased clothing since early 2017, but when I did shop, an investment of a few hours would result in a bag or two of clothing items, some of which would never or rarely be worn. I probably spend at least as much on fabric as I used to spend on clothing—sewing for yourself is by no means inexpensive! But my wardrobe is more carefully chosen and much higher quality than it used to be. Slow and steady builds the wardrobe, and if I make something that for one reason or another doesn’t work, I can either take it apart and make it work, turn it into something else (a dress from my early sewing days that just didn’t fit right became a totebag, for instance), or save it to stuff a handmade floor pouf (the first one I made contains all the scraps and trial projects from my first three years of sewing, and is a comfy and stylish place to rest my feet while I’m reading).

Threading the Needle

“Don’t pull it or force it,” my teacher advised as we learned to feed fabric through the machine. Pulling it and forcing it were, at the time, two of my most-reached-for tools in life. Being in the moment of the sewing lesson let me see that pulling and forcing might not, actually, be optimal in life either. At my sewing machine, I learned that it was important to be present, paying attention to the fabric, the instructions, the machine, and my fingers. At the same time, it was important to relax, to find ease. I also received many lessons in grace and self-compassion.

During my first garment-making class, I messed up sewing the sleeve on a top. I made a common mistake—fabric from the body of the shirt got caught up in the sleeve. “The Stephanie Domet special,” I joked to my teacher, who replied, kindly, “You are so hard on yourself.”

Her comment opened a space for me to be with myself, noticing and interrupting my very chatty inner critic. It was, after all, the very first sleeve I’d ever tried to sew onto a shirt (never mind that I made the same mistake on the other side, which was, after all, only the second sleeve I’d ever tried to sew onto a shirt). It was a mistake easily undone. And, it turns out, rushing to judge myself before anyone else could was simply unnecessary—and it sure didn’t help me learn and build my skills.

BROWSE ONLINE AT mindful.org/shop 22 mindful June 2021 mindful living

Support your mindful living journey with mindfulness courses, audio meditations, print & digital mindfulness meditation resources, merch and more!

mAUDIO Try a SelfCompassion Break

A five-minute guided meditation to help you be kind to yourself. mindful.org/ break

There’s a hashtag sewists use on Instagram—#smyly or, sewing makes you love yourself. That’s been true for me, whether because sewing has allowed me to clothe my body in a way that matches my inner self-expression, or because sewing has invited me to slow down, be a beginner (there’s always something more to learn, some more complicated project to undertake), or given me a sense of self-sufficient capability, or some combination of all of that. There’s another hashtag popular with sewists—#sewingismysuperpower. The best part about that is that it’s a superpower that’s broadly available to anyone who cares to pick up a needle and thread—and it can lead to a lot more than a few handmade garments. ●

June 2021 mindful 23 PHOTOGRAPH BY

/

SHUTNICA

ADOBESTOCK

REBALANCE YOUR Energy Levels

Trying to pin down why you’re constantly exhausted can feel, well, exhausting. Experts say part of the solution could involve nurturing your adrenal health.

The pattern goes something like this: You feel exhausted and unwell, so you open a search engine and type. Your symptoms are common enough that every condition seems possible, and you go down one rabbit hole after another in search of what’s wrong.

You easily dismiss certain possibilities, but your symptoms persist. With repeated searching, you might read “feeling tired” (yes), which “doesn’t get better with sleep” (yes again) and where you’re “craving salty snacks”

By Steve Calechman

24 mindful June 2021

mental health

PHOTO BY NATHAN DUMLAO / UNSPLASH

(oh man, that’s me). And then you happen upon a term that covers all of the above: “adrenal fatigue.”

You feel a little hope, until you discover that “adrenal fatigue” isn’t a medical term yet. It is becoming more recognized by physicians, according to Rael Cahn, an assistant professor of psychiatry at University of Southern California who’s researched how yoga and meditation can affect the brain and cortisol levels. For now, the label is “still on the periphery,” says Cahn. That’s not to say that your adrenal health doesn’t affect your level of fatigue.

Keys to the Stress Response

The adrenal glands sit on top of the kidneys. When the amygdala in the brain perceives a threat, the adrenals release hormones: Adrenaline gets the heart pumping, and if the threatening situation continues, cortisol is secreted to mobilize energy to deal with the threat. At the end of the cycle, the cortisol feeds back into the brain to shut down the stress response and return to equilibrium.

Apart from our stress response, cortisol production rises and falls with a diurnal rhythm. It’s highest

in the morning, to wake you up for the day ahead; by midnight it’s dwindling, letting you wind down. Stressors can cause cortisol production to spike up and down throughout the day, but overall, when all is functioning normally, it tapers off toward nighttime. However, when adrenal function is “off”—the adrenals aren’t responding properly to messages from the brain, or the brain is telling the adrenals to secrete the wrong amount of cortisol— “the system can get out of whack,” says Linda E. Carlson, professor of oncology at the University of Calgary. While stress-induced cortisol fluctuations by themselves don’t cause symptoms, if stress persists for weeks or months, it may cause cortisol-induced problems like insomnia, weight gain, and fatigue.

To complicate things, symptoms of your adrenals being “off” can overlap and also be nonspecific, says Irina Bancos, associate professor of medicine and adrenal endocrinologist at the Mayo Clinic. Trying to diagnose your own problem can lead to the conviction that your adrenals aren’t working properly. This may be true, says Bancos, but without a medical diagnosis, “adrenal fatigue” is a largely meaningless term.

Zeroing In on Adrenal Issues

One challenge is that there aren’t definitive tests for adrenal health, as there are with diabetes and blood sugar levels. And an

underlying issue is that the adrenal glands are seen as all-or-nothing: They either work or they’re shut down. Perhaps it would be more helpful to view adrenal health on a spectrum, like Type 2 diabetes (T2D), says Bancos. T2D impacts a gland (the pancreas), in which its capacity to make insulin becomes dysregulated and cannot meet the body’s needs, leaving excess glucose in the blood. Instead of “adrenal fatigue,” Carlson suggests a more accurate term is hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) dysregulation, which is more encompassing and includes issues with the neuroendocrine system, which handles stress. Here, adds Carlson, the problems leading to elevated or lowered stress hormones are not only due to adrenal malfunction, but also in the signals sent to the glands from the brain.

Bancos adds another condition, adrenal insufficiency, in which there’s a lack of cortisol production either day-to-day or in response to stress. She agrees that making a diagnoses can be complex. →

ABOUT

AUTHOR Steve Calechman is a contributing editor for Men’s Health and a writer for MIT’s Industrial Liaison Program. A journalist for over 25 years, he is also a regular contributor to Mindful m RESOURCE Manage Stress Better

our best tips and practices to help you navigate and manage stress. mindful.org/ stress-guide

THE

Find

“When we take time to stop and listen to our inner experiences, we become more attuned to when our bodies are out of balance.”

MICHAEL MANTZ

June 2021 mindful 25 mental health

Integrative Psychiatrist at the University of Calgary

For example, if the problem is adrenal insufficiency, the treatment is straightforward (commonly hydrocortisone) and symptoms can go away quickly. But there’s also partial adrenal insufficiency, where people can have normal cortisol production for usual activities, but an abnormal response to stress, she says.

Bancos adds, “It takes time to untangle,” and many doctors don’t have that freedom. Symptoms could be related to more chronic issues like sleep apnea, fibromyalgia, anxiety, or depression. Uncovering the problem “requires a pretty open, intense approach from both parties,” she says.

Off Balance Due to Stress

These experts agree that stress can play a role, and mindfulness can

ease stress naturally. Since cortisol is a stresstriggered hormone, how a person manages stress can affect whatever the condition is. Michael Mantz, a psychiatrist in Santa Barbara, California, says that a common result of adrenal issues is hypersensitivity to stimuli like light, sounds, even foods. More things are perceived as threats: “You become more reactive to life itself,” he says. Research shows that regular mindfulness practice can support the parasympathetic nervous system, as well as regulate the sympathetic nervous system, which reduces our threat sensitivity and grounds us through daily stress. “When we take time to stop and listen to our inner experiences,” says Mantz, “we become more attuned to when our bodies are out of balance, and can respond efficiently.” ●

a non-profit supporting your meditation practice since 1975 made in vermont take your seat. m editation c ushions m editationbenches japaneseincense Lojong sL ogan c ards m editationgongs 30 Chur C h Street, Barnet, Vermont 05821 samadhicushions.com 1.800.331.7751 Save 5% on Meditation Seats with code MINDFUL 26 mindful June 2021 PHOTOGRAPH BY TABITHA TURNER / UNSPLASH

WAYS TO BALANCE Your Nervous System 6

Try these practices to rein in the stress that might be impacting your adrenal health.

1 BREATHE

One method is the ocean breath: “You partially close the back of the throat on your exhale, which gently lengthens its duration,” says Mantz. He offers two guides: Pretend you’re fogging up a mirror, or breathing like Darth Vader. Increasing the length of your exhale strengthens the parasympathetic nervous system and eases an overactive fightor-flight response.

2 BE PRESENT

Learning to see thoughts as just thoughts, and not threats, means you can step out of panic mode and your adrenals will be activated less frequently. Carlson says to envision a river with two options: You can be in the water, swept away with the thoughts, or you can be on the bank, simply watching the river flow by.

3

SCAN YOUR BODY

Start at your head and progressively move toward your feet, paying attention to the sensations in each area of the body. This is another way to strengthen the parasympathetic nervous system and keeps you grounded in your body, Mantz says.

4 MOVE

Physical exercise helps the brain shift out of stress mode and activates adrenal hormone production, Cahn says. But a moderate pace is best, since intensity can tax the glands. Keep monitoring your body’s response so you can adjust as needed.

5 FIND CALM

Seated yoga postures and meditation help you deal with low-level stress and lessen reactivity, so that “the body is more poised to respond,” Cahn says. Research shows practicing yoga can help regulate the sympathetic nervous and HPA systems.

6

SLEEP WELL

Adrenal issues often sap our energy and sleep quality. You can reestablish your circadian rhythm by waking and going to bed at the same times every day. Aim to get 15-20 minutes of sunlight exposure within three hours of waking up: “The light is your body’s natural alarm clock,” Mantz says. And avoid bright lights for at least two hours before bed. “It’s like drinking coffee at 8 p.m.,” he says. “Your body is exhausted but your brain is still on and wired.”

June 2021 mindful 27 mental health

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Elaine Smookler is a registered psychotherapist with a 20-year mindfulness practice. She is also a creativity coach and is on the faculty of the Centre for Mindfulness Studies in Toronto.

Feeling Lonely in a SEA OF LOVE

Even when you feel disconnected, you’re part of something larger than yourself. Your community is not just who you already know—it flows in abundance when you’re in need.

A global pandemic is a very inconvenient time to fall into the arms of cancer, chemotherapy, and hospital hijinx. And yet there we were, my husband and I, suddenly facing zillions of jagged little decisions and challenges. Meanwhile, everyone we knew also seemed to be struggling— with health, money, or relationships. Yet somehow, even during this time of seemingly ferocious division on planet earth, our wide-ranging network revealed itself to be a community that rose up to support us. Who knew community even still existed?

When you live in a big city it is easy to imagine that no one cares. It can feel difficult to connect with others or hold relationships together. We might feel isolated, and that we are not part of a community. But consider this: Community is an abundant ever-changing flow of spontaneous friendliness that might only be there for a precious moment. It can be composed of long-nourished friendships or family; or, it could be a kind nurse you might never see again. When we open to seeing ourselves as part of a living, breathing organism known as community, we recognize

By Elaine Smookler

28 mindful June 2021 inner wisdom ILLUSTRATION BY SIMONA DE LEO

the communal interweave of the person we buy a donut from, the children who run by us on the street, someone crying on a bench, or singing in the park. As much as we might try to avoid this circus of humanity, we can’t escape each other.

Letting go of our expectation of how community is supposed to be there for us allows us to rest more easily in the ocean of love and support that might come from unexpected directions: the pharmacist, colleagues, people who haven’t been in touch for years, a fellow traveler on the street. Community is a mindset, rather than a concrete structure. It’s ever-changing and can manifest in so many different ways.

In our case, some days there’d be a jar of soup, a casserole, or flowers left on our doorstep. Other days there might be heart emojis and rides to the hospital. There seemed to be no end to people’s generosity and what I noticed was that so little was needed. The smallest gesture of reaching out was a powerful and remarkable way to communicate connection and inclusion. We felt loved and held in so many ways!

The people in our community don’t necessarily know each other. Our community is made up of people who have differing viewpoints and radically differing lives. Some of them barely know us at all. In spite of all the things that don’t seem to make our community a community, there is a common desire to care and be part of something. And out of that desire, the supportive net known as community is formed. It doesn’t take much. Just the willingness to see the magic of connection—and leave or receive the odd jar of soup on the porch. ●

Nurture Community

Explore this meditation to help you nurture the buds of community that bloom where you might least expect it.

1

Imagine someone you are having some difficulty with. Take a breath and allow yourself to look into the eyes of this person. Picture them as a little child, maybe four years old. Can you delight in the sparkle and beauty and uniqueness of this wondrous being? Imagine, if they were your own child, how you would wish them well, keep them safe. Picture them aging. See them take a blow, a shame, a hurt, an indignity. Allow yourself to know they have experienced hurts you cannot imagine, burdens, terrors, sorrows, failures, losses, loneliness, addiction, disappointment, rage, and no end to sadness or despair. 2

m

AUDIO Engage With Community

Rhonda Magee teaches the RAIN practice to recognize how our community shapes our world. mindful.org/ community

Let yourself be open to knowing you don’t have to fix them or heal them, but perhaps you can just be with them. Feel the ache and the terror and simply open to being there. As you look again into the eyes of this being, can you also see the spark of joy, the muddy boots running wild through the backwoods, the potential for happiness, the wit, the laughter? 3

Imagine reaching out and wishing them well. Picture the potential for joyful camaraderie, the moments of ease, the relief of kindness. See the web of connection and know that we all want to be happy. We all want to be safe. We all want to belong. Open your eyes and see community flowing toward you, everywhere.

June 2021 mindful 29 inner wisdom

WHAT MAKES Good Gossip

Gossip can be a vehicle for meanness and chaos—but as Dacher Keltner explains, it can also be a social practice that works for the greater good.

For many, gossiping ranks among the great sins. Saint Paul placed whispering and backbiting on a par with murder, deceit, and fornication as vices deserving of capital punishment. Teachers routinely ask middle-school students to not gossip or whisper with their friends. For good reason: Gossip can humiliate and harm in ways that might even shorten lives. Andrew Jackson’s wife, Rachel, had left her

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dacher Keltner is a professor of psychology at University of California, Berkeley, and the faculty director of the Greater Good Science Center.

first marriage to run off with the future president in 1793, when divorce rates hovered between 0% and 5%. As a result, she was the target of vicious gossip during Jackson’s presidential campaign. When she first read of her damaged reputation, she collapsed in tears. Weeks later, she was dead.

There’s no question that gossip can be damaging. But these exceptional uses of gossip—typically by those who are abusing their power—do not prove the rule. In fact, gossip is an ancient and universal means by which group members give power to select individuals and keep the powerful in check.

Gossip is how we articulate a person’s capacity for advancing the

greater good and spread that information to others. We gossip about what might be true of a person’s character. When we talk with others about firmly known facts—a neighbor is in prison, a work colleague is in rehab, a friend on the softball team has cancer—we are passing on established information that does not buzz with the energized feel of speculation so true of gossip. We resort to gossip to explore potential flaws in a person’s character. Gossip seeks confirmation of character flaws defined by the flouting of principles that enhance the greater good.

Gossip, then, is how a social network negotiates and establishes a person’s →

By Dacher Keltner

30 mindful June 2021 brain science

• Illustrations

by Edmon de Haro

HUMAN

AND FUNCTIONAL MEDICINE

Explore our online graduate-level programs.

• Master of Science

• Graduate Certificate

• Doctor of Clinical Nutrition

Our communities are struggling with an increasing burden of chronic, complex illnesses – many of which are perpetuated by suboptimal nutrition. To address the most challenging patient cases, we need expert practitioners, who can apply advanced evaluation and treatment strategies to find the underlying drivers of illness and help to resolve them. A degree in human nutrition and functional medicine from University of Western States allows our graduates to Take the Lead in their chosen fields and positively impact the health care of tomorrow.

LEARN MORE

uws.edu/mindful

NUTRITION

reputation, in particular those who seek power and want to exert influence in Machiavellian fashion. For example, US presidential campaigns are defined by pitched battles over gossip, which hovers around every candidate and eventually targets every president at some point. Political gossip zeroes in on whether a politician does things that risk unraveling the culture, or things that are the foundation of the greater good. During the era of slavery, political gossip focused on candidates’ racial background. During Prohibition, gossip investigated politicians’ alcoholic tendencies and the potential hypocrisies of their imbibing. During the drug wars, the drug-taking habits of politicians became prominent. In 2021, that people gossip about the potential factors that produced the coronavirus pandemic is not surprising, given heated international tensions and the erosion of public trust in scientific and political leaders. Thomas Jefferson had a keen sense for the power of gossip in establishing political reputations. He catalogued the forms of political gossip during his day and concluded that the most damaging centered on selfish, backstabbing, socially destructive acts.

A Cap on Selfish Actions

To capture Jefferson’s reasoning as it applies to a 21st-century social group, I studied the patterns of gossip in a network of sorority sisters at UC Berkeley. In the first phase, I gathered measures of the sisters’ Big Five—their enthusiasm, kindness, focus, calm, and openness—and their Machiavellianism, or tendency to lie, manipulate, and coerce. Then several weeks later I brought each sister to the lab and interviewed her privately about how often she gossiped about each of the other women in the sorority, and with whom she shared the gossip. The frequent targets of gossip were young women who most threatened the sorority’s greater good: They were well known and highly visible but, by their own reporting, unkind and highly Machiavellian, willing to

harm, lie, and manipulate to rise in power. As in this case, gossip typically targets individuals who seek power at the expense of others.

Other research has found that gossip’s purpose is to tarnish the reputations of individuals who diminish the greater good. Researchers who hung around a crew of strapping rowers at an East Coast college listened in on the teammates’ banter as they traveled to and from practice. The gossip systematically concentrated on one teammate who was not making practices on time, nor rowing hard enough or in sync with his teammates. He was failing to advance the greater good by literally not pulling his weight. Cattle ranchers in the western United States, in their spare, tight-lipped exchanges, gossiped about their neighbors who didn’t keep their fences in order. Again, gossip targets actions that undermine the trust of the community—for ranchers, the poor upkeep of fences. In huntergatherer societies, gossip is directed at coercive bullies who exploit others and steal food or sexual partners.

How gossip flows through social networks enhances its power to tarnish the reputations of those who do less to promote the greater good.

Follow this guided practice to bring awareness to how gossip affects you and those around you.

mindful.org/ gossipawareness

m

AUDIO Gossip Awareness

brain science 32 mindful June 2021

On average, we pass along every act of gossip we receive to 2.3 people, typically to high-status, highly connected people like, in the sorority study, high-status and admired young women. Gossip flows to individuals who have the greatest power to define, and damage, the reputations of others.

Gossip Gone Wild

So powerful is the social instinct to gossip that it gave rise to institutions that preserve its basic function. The first newspapers in 17th-century England to be widely read and financially sustainable were gossip rags about the neighborhood knaves and ne’er-do-wells, the flirts and drunks, the philanderers and squanderers, and the debauching aristocracy. One of America’s wisest citizens, Ben Franklin, wrote a gossip column, the first in America, that appeared in 1814 and was devoted to satirical commentary upon the scurrilous acts of people nearby.

In today’s digital world, gossip and the construction of reputations have gone viral on websites and blogs. Restaurants, stores, and hotels anxiously keep an eye on their customer ratings on Yelp. Politicians are tracked on Gawker and spoofed on The Onion. The Shittytipper Twitter feed names well-known individuals known to tip below the conventional 15-20%. A now-defunct blog called Holla Back NYC allowed women to submit photos of men who harassed, groped, catcalled, or leered at them.

Our obsession with spreading information about reputation has costs: intrusions into our private lives, mistakes in identity, and escalations into bullying, all indirect forms of oppression. Most of us have been the inappropriate targets of gossip and suffered in the moment. But on balance, the benefits of allowing groups to freely communicate about the reputations of others outweigh these costs.

In one study to first capture this idea, 24 participants came to the lab and were divided into groups of four.

They played six rounds of an economic game; in every new round they played with participants they had not played with before. In each round, each participant was given some money and presented with the chance to give some money to a group fund. That gift would increase in value and be redistributed among the four players. This game pitted the tendency to act on behalf of others—give money to the group fund— against the free-riding tendency to not contribute yet take money from the group fund built up by others’ generosity. At the end of the first round, players learned how much the three other group members had given to the group fund. Participants moved on to a new group of four players and played again, repeating this procedure six times.

After the first round, the study got interesting. In a gossip condition (that is, one of the subgroups within the study), participants could send a note to those who would be playing with their former partners about those individuals’ cooperative or selfish tendencies. As in real life, all players were aware of the possibility that they would be gossiped about. In an even more puritanical condition—gossip plus ostracism—participants had the

chance not only to gossip but also to vote to exclude their former partners from playing in the next round.

Who Can You Trust?

In a neutral condition lacking the opportunity to gossip or ostracize, people gave less and less to the public fund over time. After trusting others initially but being taken advantage of by the occasional individual with low commitment to the greater good, most people abandon their cooperative instincts and give less. In the condition in which participants could gossip, participants actually gave more. And in the condition allowing for gossip and ostracism, participants’ gifts to the group fund actually rose over the course of the experiment.

Social penalties like gossip, shaming, and ostracism are painful indeed and can easily be misused (in particular by those in power). But they are also powerful social practices, seen in all cultures, by which group members elevate the standing of those who advance the greater good and prevent those less committed to it from gaining power.

Power is the capacity to influence. It is the basic medium of our social lives. In the past 50 years, power—in politics, in the workplace, in our communities—has become more diverse and collaborative. Yet, we can still find examples, particularly in the political landscape, of coercive, deceptive, violent approaches to power. We have also seen, though, that such forms of power will not be tolerated forever. In the absence of wisdom, power leads to empathy failures, selfish and destructive acts, and racist, polarizing attitudes. Yet our social systems, from neighborhoods to democracies, are expressions of our power to rein in those who abuse theirs through accountability, assessing reputations, and uplifting what we esteem.

We all suffer from power irresponsibly wielded. Let’s turn toward compassionate power. ●

June 2021 mindful 33 brain science

From The Power Paradox by Dacher Keltner, published by Penguin Press, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2016 by Dacher Keltner.

OOPS

THE FINE ART OF FAILING

Our failures only hold us back if we don’t engage with them mindfully. Katherine Ellison learned the hard way the value of failing with presence— and recovering with slow accountability.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ALAN SHAPIRO / STOCKSY

PHOTOGRAPH BY PLAINPICTURE / RALF MOHR June 2021 mindful 35 self-discovery

When I was 23 and just starting out in journalism, I made an awful mistake. While covering a high-profile trial in San Jose, California, I wrote that a woman who hadn’t been charged with any crime had plotted a murder.

The woman I’d wrongly incriminated sued me and my newspaper for libel, demanding $11 million. Had she won, it would have killed my career and financially damaged my employer.

Alas, this wasn’t my first reporting error. In the preceding weeks I’d made a series of smaller mistakes, mostly getting names and dates wrong, although once I’d quoted a rancher as telling me he had to leave to “shoot a horse” when he’d really said “shoe” a horse. He called the news desk the morning that story appeared to demand a correction, saying his sister worked for the Humane Society and had given him hell.

As these errors piled up, I feared my days at the newspaper were numbered. But I still couldn’t seem to slow down and take the time to check my work. Instead, whenever possible, I blamed the flubs on others. The rancher had mumbled. The copy editor hadn’t done his job. My editors were overworking me and I was tired.

By the time of the libel lawsuit, I’d run out of excuses. But surprisingly, instead of firing me, the paper’s managing editor—a tough-on-theoutside Lou Grant type who until then had been my biggest fan—suspended me for three days, giving me just one more chance. He also bluntly suggested I use the time to get professional help.

“You’re sabotaging yourself,” he warned.

I took his advice and, even before I left the newsroom that day, tracked down a psychiatrist to make my first appointment. I couldn’t bear the thought of losing a job that was then my whole identity, and understood in that moment that I had no choice but to change: to stop looking for excuses, and to do the hard work to become

the kind of person I’d long wanted to be—both more competent and more trustworthy. In other words, I had to start being more accountable. The main problem was, I still had so little faith that I could make such a big change.

Slow Down to Speed Up

This was (ugh, how time flies!) 1981. Mindfulness wasn’t a mainstream thing yet. But Freudian psychoanalysis, couch and all, was available for those who had really good insurance or could otherwise find the money to pay. My psychiatrist was still in training, reporting to a supervisor. He offered me a hefty discount that made it just affordable.

His mantra was, “Mistrust your sense of urgency,” which was at once the most helpful thing I’ve ever heard and the most difficult thing I’ve ever done. Again and again, he urged me to sit still and experience my feelings, rather than doing what I most yearned to do, which was to run from them, in any way I could. It’s embarrassing to look back on all the hours I wasted in ridiculous debates with him about whether I really needed therapy at all, and in trying to change the subject, and in throwing myself harder into work and pleading exhaustion as a reason to cancel appointments. But at last something shifted and I managed to face my all-but-overwhelming shame at having screwed up so repeatedly—and, more deeply, in believing I was destined to keep screwing up. Only then could I see how much shame had determined my behavior until then, particularly in my insistence on looking for other things and people to blame for my own mistakes. My editor was right—I had been sabotaging myself, for reasons that would take a long time to understand. Four years, to be precise.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Katherine Ellison is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author, most recently, of Mothers & Murderers: A True Tale of Love, Lies, Obsession …and Second Chances

A couple of decades later, when I was bringing up my kids, a wise swim coach observed my eldest son’s fast but awkward freestyle and told him, “You’ve got to slow down to speed up.” Sparing the grisly details, my own speed, just as clumsy, had some roots in childhood events that had conditioned me to tune out whenever I was stressed. Sticking with the therapy helped me first slow down enough to bring my brain’s →

PHOTOGRAPH BY PLAINPICTURE / YVONNE RÖDER

36 mindful June 2021 self-discovery

“

Once you stop to notice, you may be surprised by the prevalence, variety, and depth of human error.

pilot back into the cabin and stop making those mistakes, and then to patiently learn why I’d been making them. As time went on, my psychiatrist also helped me stop playing the victim whenever I was challenged. He insisted that I behave with integrity, beginning by charging for missed appointments whenever I canceled without a good reason.

Eventually, this practice—although it still wasn’t popularly called that—of learning to be aware of when I felt like outrunning my feelings and then patiently returning to face them would help make me not only a more careful journalist, but also a better listener. That, in turn, helped me be a better friend, wife, daughter, and mother than I otherwise ever could have been. I’m not suggesting that four years of therapy is the best solution for anyone making errors at work. But for me, slow accountability saved my life.

For Shame

Once you stop to notice, you may be surprised by the prevalence, variety, and depth of human error. From the simple fender-bender on your way to work to immensely more devastating plane crashes, botched surgeries, and downright horrific cases of parents leaving babies in hot cars, we constantly, mysteriously, act against our own self-interest.

My own experience with a far less consequential but still potentially devastating error early in my life has made me obsessed by human error, and particularly how people recover from the shame of seemingly incomprehensible mistakes. Mitch Abblett, a clinical psychologist and former executive director of the nonprofit Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy, shares this interest, writing powerfully about the way shame can paralyze us.

“The shame response is very old and comes from a primal part of the brain,” he told me in a recent interview. “As a psychologist I think of our evolutionary biology: Tens of thousands of years ago, if we did something that caused us to feel shame, it was related to our very survival, to fear that we’d be rejected from our social group and die.”

Abblett says a mindfulness practice can help people move past seemingly intolerable shame, as they ride out the physical sensations arising from shame and the “indignant arrogance” he says often accompanies it to arrive at regret, an emotion that more easily allows us room to make wiser choices—and to be more accountable. He gave the example of the 2007 documentary film, The Dhamma Brothers, which followed four convicted murderers on a 10-day meditation retreat in an Alabama prison. The prisoners said it was agonizing at first to sit still with the awareness of what they’d done to others and what others had done to them. But once they stuck with it, it was also liberating.

Fail Fast?

It’s interesting to contrast the Dhamma Brothers’ experience with the movement, over the last several years, to destigmatize failure in a hurry. “Fail fast, fail often!” and “Move fast and break things!” are the relentlessly cheery slogans of Silicon Valley, a place in which three-fourths of startups go bust. The archives of the TED Talks—the Valley’s influential e-sermons— include more than a dozen presentations about failure, many of which tout its “surprising” benefits. A paean to “celebrating failure” by Astro Teller, the “Captain of Moonshots” at Google’s idea factory, X, has been viewed more than 2.6 million times. In 2009, the same ethos inspired a popular program called “Fuckup Nights,” in which entrepreneurs take the stage to talk about their business disasters. The Mexican entrepreneur Leticia Gasca founded the project after her startup, a philanthropic effort to help Native women sell their handicrafts, went bust. Since then, “Fuckup Nights” have been held in more than 250 cities in 80 countries. Gasca’s organization also offers workshops to businesses to help “create a culture that celebrates trying, rather than stigmatizing failure,” according to their website. Using storytelling and a Q&A session, the workshops aim to “eliminate shame to turn it into accountability and autonomy.” FailCon, a similarly themed day-long conference, was founded around the same time by Palo Alto

Patricia Rockman leads a 10-minute practice to help loosen the hold of difficult emotions.

mindful.org/ art-of-failing

PHOTOGRAPH BY PLAINPICTURE / MIEP

m AUDIO Tame Your Shame

38 mindful June 2021 self-discovery

software designer Cassandra Phillips and has also gone global.

My reporting errors were in another class than the Silicon Valley sorts of failures, which mostly involve mistaken strategies and decisions. But both kinds of blunders share two important things: the potential to harm other people—say, when livelihoods are lost after businesses go bankrupt—and the corresponding need for someone to take responsibility and make changes. Both, in other words, demand accountability. And that might require something more mindful and systematic than just sharing stories of failure.

Sam Silverstein agrees. A former manufacturing business owner and author of several books about accountability, Silverstein’s main point, which he stresses repeatedly, is that accountability never happens in isolation. “It’s always a matter of being accountable to someone,” he told me. “Accountability is keeping your commitments to people. We’re responsible for things, but we’re accountable to people.”

I thought back on my tough-love treatment by the managing editor, and how much I’d wanted to redeem myself in his eyes. I also remembered the bond I’d established with my psychiatrist, who so skillfully, over months and years, had gained my trust and respect. It made sense that accountability depends on these kinds of strong relationships, which require long and steady investments of time. Still, I don’t believe you can achieve it without also devoting a lot of individual effort. As I recalled all that work with the psychiatrist, predating the mindfulness movement, it felt as if he’d helped me build up my muscles to face down shame on my own the next time it emerged. At the end of our time together, it was up to me to keep those muscles in shape, by honestly questioning my behavior and, importantly, by making sure I always had other relationships in my life—both in and out of work—that would help hold me accountable.

My slow accountability practice has helped me in my marriage and in deepening friendships, but it’s probably helped the most in my relationships with my children. I grew up with the notion—handed down from my own mother—that mothers should be perfect, that →

“

I had no choice but to change: to stop looking for excuses, and to do the hard work to become the kind of person I’d long wanted to be.

June 2021 mindful 39 self-discovery

When You’ve Caused Harm

Finding our way to true accountability requires a willingness to sit with the discomfort of having caused pain, allowing true compassion to arise.

By Vinny Ferraro

Compassion is a kind, friendly presence that allows us to stay in contact with the pain we may feel when we’ve caused harm, so that we can deepen into it rather than turn away from ourselves. It has the same connecting quality as empathy, but has a desire to help as well.

Whether it’s pain in the body, a mind that doesn’t seem to know peace, or a world at war with itself, we can pay attention to the hurt and care for the wound, honoring it, instead of just trying to get away from it. We can then rest in the simple truth that we’re here and we care about what’s difficult.

When we truly tend to our hearts and allow them to be touched by what is difficult, let them break, from the fear of pain or hurt, what arises is a natural tenderness. As Stephen Levine wrote, “to heal is to touch with love that which was previously touched by fear.” So when we bring compassion home to include ourselves, especially when we have failed, we finally get to honor the hurt. This is the alchemy of presence.

Living with an undefended heart is a profound expression of freedom and the promise of the sure heart’s release. We do this inner work so our lives can become an offering to all those we dare care about. Because ultimately, compassion is a verb.

PRACTICE

PHOTOGRAPH BY JUJ WINN / GETTY IMAGES 40 mindful June 2021

A PRACTICE FOR BEING WITH THE PAIN OF FAILURE, AND TAKING ACCOUNTABILITY

Find a comfortable seat. Settle, and breathe. Now, begin your inquiry. To start, the two components we’re looking for are clear seeing and willingness. Ask yourself: “Am I seeing clearly?” and in this moment, “Is there willingness present?”

Since self-criticism is not helpful, don’t get lost in the story of why things shouldn’t be as they are. Instead, allow yourself to feel the pain and quite naturally there’ll be a compassionate response to it. Because If we can’t feel it, we can’t heal it.

Don’t take it personally by becoming over-identified with the role you played in the situation. You didn’t give birth to these energies, they are universal, they belong to this realm, not you. When it’s not taken personally, we realize we can practice with anything we come into contact with—stress, frustration, pain, nothing is outside of our care.