MIND OCEAN SPACE

MIND OCEAN SPACE is a new multimedia magazine. It is a publication exploring the frontiers of human knowledge and existence, which is where it got its name.

The idea of the mind, the ocean, and space as ‘frontiers’ was developed in late 2019 whilst walking home along Cambie street in Vancouver from The Joker film with my friend Oscar. However, it was not until mid-2022 that the thought of turn ing this idea into a publication came about.

During the coronavirus pandemic, my friends and I absorbed and produced a lot of creative content, with nowhere to pub lish or share it. The concept of the magazine is to help us un derstand and develop an interdisciplinary view on the world around us using art and science—two things I love, but that rarely get to meet under one roof. I hope it will be a place for sharing interesting things, creative things, funny things, and beautiful things.

Submissions are accepted on a rolling basis. You should con tribute if you have something to say: an invention, a passion, a creation, or an idea. The digital format will allow for flexibility in media types, and readers are able to order individual copies at printing cost. We’ve received poetry, photographs, digital art, essays, short stories, music albums, and pieces of scientific research. Please get in touch if you are interested in submitting a piece.

Email: mind.ocean.space@gmail.com

Instagram: @mind.ocean.space

Thought, cognition, emotion, human experience, psyche, soul. How do we exist in and per ceive the world around us? Delve into my brain, imagine the colours only I can see. My mind is a beehive and every letter counts.

The actual ocean, or a metaphor for all that the natural world encompasses. We may explore, exploit and experiment with Mother Nature, but never should we expect to conquer her. What does the deepest part of the ocean look like? You tell me.

MIND OCEAN SPACE

Outer space, technology, the Universe and the Milky Way. A smattering of stars, the bright and dark sides of the moons, music to my ears + other miscellaneous things. What are you wearing, what are you listening to? Tell me more—a space for exploration.

Managing Editor & Contributor Noa Amson

Cover Art Be Nice Signs @be.nice.signs

Layout & Design Cole Cooper

Contributors

Timothy Andrews

Saja Badusa

Tagget Bonham-Carter

Thea Bryant

Sophie Edwards

Miriam Elhajli

Panos Giannadakis

Alanna Grogan

Louise Hall

Franz Hildebrandt-Harangozó

Nikola Kolev

Oscar Morgan

Tevin Muendo

Duc Vinh Nguyen

Csecs Norbert

David O’Connor

Johannes Pfahler

Camila Posada

Kiera Saunders

Erin Tattersall

Lindsay Tattersall

Carla Theuring

Liam Vandewalle

Shelan Zaynah

Featuring

Good Clean Fun

Heavy Petal Brand Bubble Music London Reuben Cantacuzino

MIND OCEAN SPACEEditor’s Note...........II Frontiers Intro..........III Contributors..........IV

MIND.........01

Chipped Tooth..........02

It’s Okay Not to Think..........08

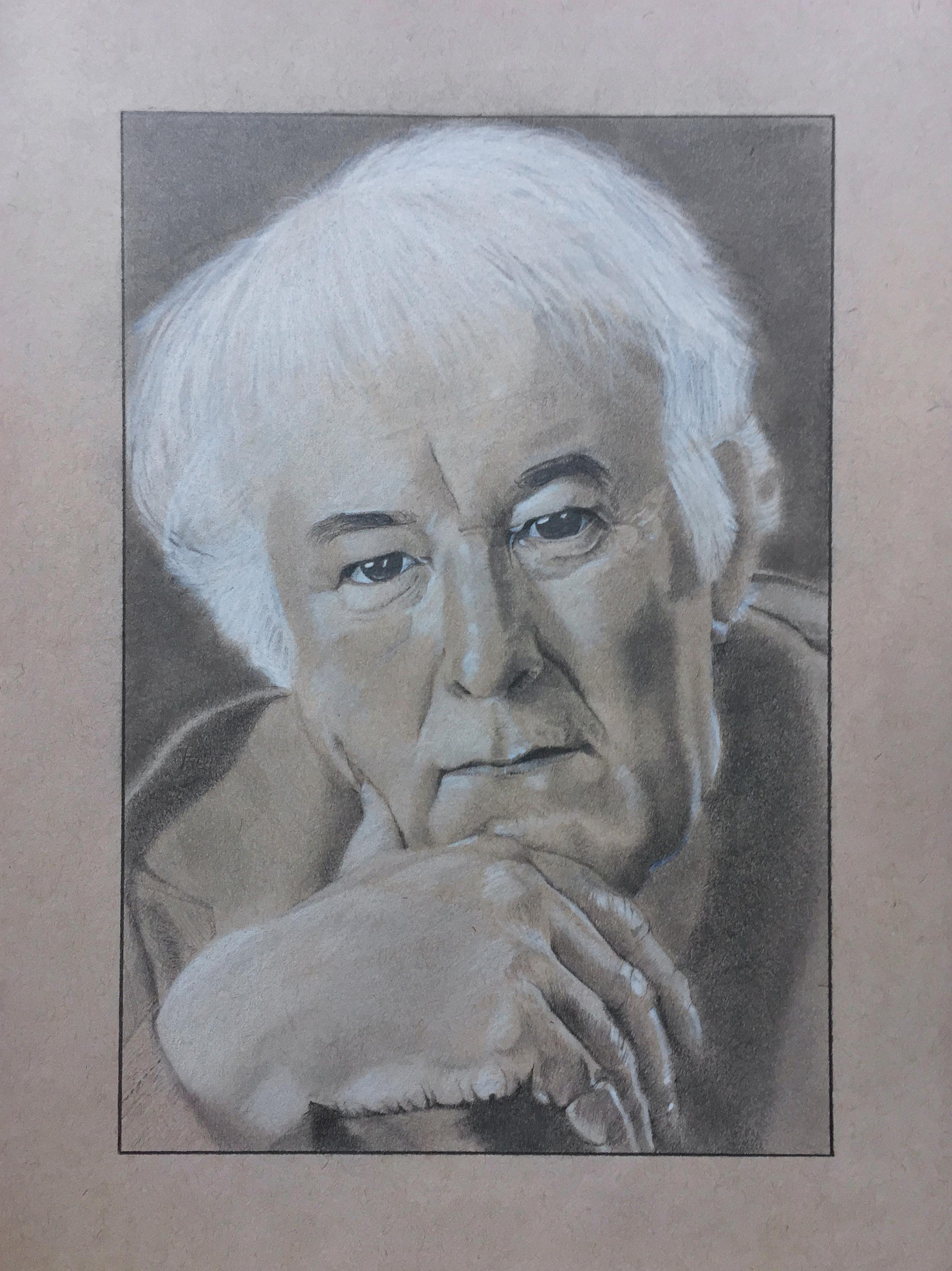

Your Brain on Drug X: DMT..........09 Seamus Heaney Portrait..........11 Drip..........12

Philosophical Dimensions of Bins..........15 Emily..........17 Elegy For Lungs..........18

A Creation Recipe: The Uncertainty of Signs..........21

Fix Your Ontology..........23

Captured by Captions / The Shop..........27

Living With Artists (Chapter One)..........29

OCEAN.........35

Nighttime on Gambier Island / Sea-through..........36

The Beach (Strand)..........37 Regenbogenforelle/Braunforelle..........39

To the South Shore..........40

Evolutionism: A Short Intro..........41 Veil..........44

Yayoi K. Meets the Natural World..........45

Afloat and afar, love is home..........49 Ecology of the Anthropocene..........51 Photography & Media by Timothy Andrews..........53

SPACE.........56

A Review of Berlin, A Novel by Bea Setton..........57 Musings on Soda Bread..........58

Black Holes ..........59

Quantum Tunnelling..........64 Stars..........67

Function, Algorithm, Implementation..........68

Good Clean Fun..........73

Heavy Petal Brand..........76 Bubble Music London..........77 Moshup App..........81

Cuzino Music..........83 Astrology Today..........85

Noa Amson | Noa enjoys writing and ed iting in her free time. She currently studies and lives in Glasgow, Scotland.

Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth.

I ran my tongue over the exterior lamina of my front right tooth. There it was, the little indent. Bottom exterior corner, where I had bitten down hard into a fork earlier that day. The mirror and a sensitive spot when eating my next forkful of curry (a nondescript saag paneer over basmati rice left over from the night before—I hadn’t even bothered to heat it up. Cold, green, and creamy, with stringy bits from the cooked spinach. A student masterpiece) confirmed that a large chip had been taken from my enamel. I ran my tongue over it again and again as sweat per meated every item of clothing I was wear ing: a bralette, a long sleeve black synthetic blend, an icebreaker half zip, a leather jack et. My scarf flapped aimlessly around my neck, where windward hairs were sticking to my perspiring chin under the chinstrap of my helmet. With each pedal stroke I ex uded more heat and lamented my choice of outfit, but stopping to de-layer would mean

wasting valuable time. The hill I was cycling up was lined by Soviet-looking tower blocks of flats and stretched out in front of me like a menacingly positioned rook on a chess board. I knew it wasn’t actually that steep, but I hadn’t cycled in ages and so my over stuffed backpack (containing a laptop, text books) combined with fear and apprehen sion surrounding the upcoming procedure all weighed me down. But the adrenaline was picking me up. I was barrelling down the highway on my screeching bike in the wilds of Scotland, somewhere between the suburban countryside metropolises of Nigel House and East Motherhill. Massive trucks containing oats, North sea oil and tinned haggis whistled by me, only inches from my gasping lungs. I was shitting myself, I was afraid. But I was on a high. You know that feeling. It sometimes feels really good and exhilarating to do some fucked up shit.

The line ‘How did I get here?’ from a song by the Talking Heads reverberated in my ears like howls in an echo chamber. This strange position of sweating my (non-exis tent) balls out, riding a bottom-of-the-line road bike on a motorway unknown to me,

using one hand to phone-navigate, the other to steer and brake should anything ‘danger ous’ arise. How this uncomfortable 20-mile cycle came to be during what should have been the heat of my revision period is what I will explain in the coming paragraphs.

As previously covered: I chipped the tooth by biting into a forkful of lunch curry whilst revising lymphatic organ anatomy. In be tween the spleen and the thymus, there went the fork and my piece of tooth with it. I swal lowed the chunk and proceeded to spend the rest of the afternoon being intermittent ly anxious about the piece of ivory sizzling away in my gastrointestinal tract. Would the HCl in my stomach be enough to break it down, would it go straight through me? Or would it cause some sort of intestinal occlu sion the consequences of which I couldn’t even imagine (mostly because I can’t re member the first-line treatment for intesti nal occlusions). I thought about the piece of enamel hissing like a snake in the cardia of my stomach full of gastric acid. My fear of dentists meant that I was apprehensive about going to some random practitioner about my chip. They might mess it up, and worse, they would see the inside of my mouth and therefore the state of the wear on my teeth. A traumatic experience from when I was 17: ‘Wow, you’re really a grinder aren’t you. Se vere damage on all upper and lower molars and bicuspids. I’ve never seen someone your age with such little tooth left.’

I googled ‘dental practice glasgow’ and rang the first one that popped up. The receptionist was unprofessional and the cost was so pro hibitively expensive that I was repulsed and slightly terrified at the idea of anyone from that establishment fixing my tooth. ‘Hi there,

my name is Louie Cardell. I’ve just chipped my front tooth. I’d like to please book an appointment as soon as possible to have it fixed,’ to which she replied ‘Hi Mr. Cardell, so what would you like done?’ There was heavy rustling in the background, making it difficult for me to decipher what she was say ing. I corrected her that I was actually Miss Cardell even though my name was unisex (Haha! A common mistake!), and repeated that my issue was about a chipped tooth. She started babbling on about a root canal and a booking fee of 50 pounds, followed by a consultation fee of 90 pounds, and all that of course before the actual cost of the rep aration of 135 pounds. ‘Let’s book you in Sir, for a root canal in 2 weeks’ time then?’ At this point I was tired of explaining myself and had already lost faith in the establish ment, and so I thanked her for her time and hung up. How could a good dentist possi bly hire such a poor receptionist? Intelligent, competent people do not hire incompetent staff. I felt the divot again with my tongue. My heart beat a little faster, like the heart of a rabbit does when the rabbit is being ‘lov ingly squeezed’ by a small child. Why had I bitten down on my fork? Why was I in such a rush to finish the bloody curry?

Anecdotes learned during my days as a horse girl flitted through my mind. ‘People will try and sell you old horses in good condition, but they’ll be overpriced for what they are. The only way to truly tell a horse’s age is by looking at its teeth.’ I imagined being an old horse, able to trick my future owners into thinking I am something that I am not. ‘Nev er look a gift horse in the mouth’, they say. ‘She’s not who she claims she is’, they say. I pictured myself sitting down in that leanedback chair, the dentist examining my worn

molars, as he gave me a liquid Valium to sip on. It tasted like red Kool-Aid. Shiny, plump cherries of the deepest hue of red. I still re member the feeling of it kicking in– like a smooth, cool stream slipping over my body and my mind. ‘The jig is up!’ I shuddered these thoughts away.

Then I remembered: my friend’s father was a dentist. I messaged Bethany to ask her for his details. She replied nearly immediately, after which I proceeded to do my ‘research.’ This consisted of Googling his practice and academic trajectory in the profession, most ly to check that no dentistry lawsuits had been filed against him. He’d actually won a few Scottish dentistry awards. I wondered what this meant for the future of oral health in Scotland; I had recently read a statistic that one quarter of Scots had lost at least 12 teeth. Perhaps if they’d had Dr. McInnis looking after theirs, they would have man aged to retain more of their pearly whites?

Also, the clinic’s website was very profes sional. It wasn’t a WordPress site with spell ing mistakes and grammatical errors like the website of the practice I’d phoned earlier. Bethany sent me another message to explain that he was extremely busy, with a 6-month waiting list, but that she could ask if he had time to ‘squeeze me in.’ Squeeze me tighter Children, rabbits.

Bethany told me to be ’at the ready’ for an appointment at 17.30. I started making my way to East Motherhill. I cycled to Glasgow Central clad in a black leather jacket and black Dickies trousers, with my waterproof backpack full of revision materials ready to get shit done on the train. A very Glaswegian drizzle and mist hung in the air. I listened to Afro B’s ‘Joanna’ in my AirPods as I navigat ed my way through the station. The outing broke up the monotony of studying; it was exciting to have somewhere to be. As soon as I sat down in the train I was struck by a wave of panic. Even if it was Bethany’s father who fixed the tooth, it meant that he would know, which is nearly worse than a total stranger knowing. I knew that dentists see this kind of thing often. Perhaps they are the only ones who can see the damage that my mind has inflicted on my body. Evidence. Habits from a much darker time in my life had caused this wear. He might be a truth teller, I thought. All dentists could be, I thought.

I replied to her message with an ecstatic ‘yes!’ and followed up with appropriate levels of gushing and thank yous. Hopefully he’d be able to see me sometime before the week end. I imagined future compliments from an imaginary boyfriend’s mother: ‘You have great dance moves, and a lovely smile.’ My tooth would be whole again soon.

My mum used to tell me, if you don’t brush your teeth they will all fall out, like Chiclets. Chi clets are multicoloured, candy-coated piec es of rectangular chewing gum that come in square packages. Pink, orange, green. Children get them trick-or-treating at Halloween. The pieces get shaken around in their boxes, and they sound like maracas. They make me think of colourful day of the dead celebra tions, of candy corn, of skulls with missing molars. I thought about my teeth turning these colours, first at the edges before greying right into the centre of each tooth. My gingi val tissue becoming loose and flappy. Disco gums, the teeth all fall out. Like Chiclets.

I was torn between my conflicting fears—one surrounding my past, the secrets of which

could be found in my mouth, and one sur rounding the integrity of my future tooth. I weighed the consequences of people know ing with those of leaving the chip unfixed to eventually rot away in my skull.

I distracted myself with revision of the neph ron. The glomerulus, Bowman’s capsule, the proximal and distal convoluted tubules. The loop of Henle and its countercurrent multi plier. What the normal Glomerular Filtration Rate was, the first line treatment for acute nephrotic syndrome with proteinuria. I wore my glasses without removing my helmet and stared at my laptop. My spirits soared to new heights. Ahh, to be young and free! I didn’t know if it was a high or a low, so I messaged Katie (because yes, as a child of the digital era, I am constantly in contact with at least my closest friends) and asked her what she thought. ‘Definitely a high. You would know if it were a low,’ she said. Just as I was finish ing with the nephron, the train screeched to an abrupt stop. I played ‘Don’t gas me’ by Dizzee Rascal in my Airpods. The song end ed. An announcement came on: ‘Due to a network failure in Nigel House, this train will no longer be traveling to our original desti nation of East Motherhill. All passengers are kindly asked to alight from this train.’

I got off the train and took in my surround ings: barbed wire fences and government signs. The station itself was peculiar; a mas sive, prison-resembling building far from the madding crowd. A handwritten sign on the door indicated that the station was in the process of being decommissioned so please do not touch the rubble. It felt completely emp ty. Nigel House was not remote in the way of mountains only accessible by helicopter in Alaska, but somehow felt so. Its oddly

square and incoherent (for both its func tion and location) architecture made it feel removed by both space and time from the world in which I spend most of my time. The chip all of a sudden took precedent in my mind again—it was feeling even big ger, grander than it had before. I imagined my entire mouth turning black, each tooth turning the colour of charcoal, the way trees look after forest fires burn the foliage they are normally dressed with, leaving only blanched trunks and charred black tops. I pictured myself in this forest, standing up in a sea of huge singed matchsticks. They were so impressively tall and bare and damaged. No leaf could possibly grow again on those branches. I would open my mouth, and they would know. Bare and vulnerable. We all have secrets, and mine is my mouth.

I checked the time of the next train for East Motherhill—I would arrive by 18.30. I sat in disbelief. A departure time that would normally put me at my destination an hour ahead of schedule was now going to get me there an hour and a half late. The practice would be closed, and more importantly, my tooth would remain broken.

The Glasgwegian drizzle from earlier had stopped, and I started to feel the sun heat ing up my leather jacket. The ball of anxi ety in my stomach surrounding the chipped tooth re-emerged: I had swallowed a solid chunk of Calcium phosphate. Would it give me kidney stones? I also hadn’t had anything to drink other than a giant mug of instant decaffeinated coffee with oat milk, which I’d sipped on alongside my curry prior to leav ing the flat. I didn’t think to bring water with me because I’m usually like a desert-inhabit ing camel in Petra; even without a hydration

hump, I am seemingly able to go for days without fresh drinking water, surviving on only hot brown drinks like tea, coffee, and Ovaltine. However, I was suddenly feeling very thirsty. My tongue was dry and fuzzy against my cheeks, conjuring the desiccated apricots of my childhood. Orange, wrinkled and gummy. Yum.

After re-checking Google maps for public transportation journeys, I began cycling as I realised that every minute elapsed was a min ute lost. I made a right turn onto the 4-lane dual carriageway, unaware this would be one of the more pleasant roads I would cycle that day. Google maps was saying that it would be 17 miles, or 1 hour and 48 minutes by bicycle. I decided to pass back through Nigel House in case there was a spontaneous train going to Glasgow because I had not yet men tally committed to the idea of cycling (which was in fact a terrible idea and ended up only adding more time due to construction and dead ends). My front wheel was rubbing against the brake pad and my inner tube had popped out, causing the tire to bulge a little.

I played out all the possible scenarios in my head. Not going to the dentist at all meant keeping my secret past hidden in plain sight, with the only immediately visible proof be ing a medium-sized chip on my front right tooth. And if I went…they would know. Who would they tell? How would I be punished? I pushed these thoughts away and focused on the problem at hand—any time spent de ciding was ticking away precious time. I felt my chipped tooth with my tongue, I thought about the incompetent receptionist from earlier than day at another dental practice. HA! As if such incompetent swine were get ting anywhere near my teeth. I was going to cycle to East Motherhill.

I took off—in the wrong direction. About half a mile in I had to turn around, just in time to hit rush hour traffic and construc tion queues. The bulldozers and asphalting machines spat their black smoke at me as I ran over their gravelly debris and prayed that I wouldn’t get a flat. I started heavily per spiring under all my layers of clothes and the leather jacket. And the backpack. The sun had burned off the grey from earlier in the morning and now a very un-Glaswegian sun was beating down on my heavily-clad body, despite darker clouds ominously lin ing the edges of the sky. My phone stayed in my right hand for navigation, and Android Siri would always tell me just too late about the slight left I had to make, or which round about exit was the correct one. I was mostly on extremely busy roads, dual carriageways with cars honking at me to get off to the side. I ignored them. Maps kept telling me to take a slightly longer route, which I wanted to avoid at all costs. “Shorter!” I exclaimed to Android Siri. My hair was plastered to my face and neck and chin now, all my crevasses were sweaty. It felt freeing in some way to be using my body in a non-obsolete, useful way: for the sake of transport. My legs were start ing to tire but adrenaline pumped through my body. Cars on either side of me, slight right, bump bump bump the sound of my brake pad rubbing on the bulge. Oh boy. Here we are, entering an on-ramp...onto the motorway? That couldn’t be right. Yet here I was, there we were, my bike and I, getting on the motorway with the big boys.

‘What am I doing here,’ I thought to myself. All of the sudden I was 17 again, in the den tist’s chair, an unfriendly hygienist sticking instruments in my mouth and poking around as if looking for clues. The Valium I had taken

was just kicking in, I was fading in and out of consciousness (‘a state in which the patient is alert, awake, and responsive to stimuli’). The medication was making me tread the thin line between being aware of what is going on around me while appearing to be passed the fuck out. I could hear them discussing the wear on my molars, but their voices were fading out, getting quieter and quieter. The dark clouds at the sky’s borders were blown away, and I was bathed in only yellow light. My head was weightless, I drifted above my body, I watched my self from above, I saw my thoughts without experiencing them—‘HAAAAAAAANNNK!’— My daydream was abruptly interrupted by a lorry honking as it sped by. The Doppler effect caused its volume to amplify as it approached me before dropping to a disproportionate and asymmetrical low once it had passed. ‘Shit,’ I thought. I could see a body of water nearby, where Google had been trying to direct me. I finally understood why Android Siri had been adamant about taking the longer route.

I exited the motorway, unscathed but shellshocked from the experience, to join the Strathclyde Lochside path. It was beautiful, the sun was shining, I could feel myself getting a nice tan on my cheeks and nose. I felt my tooth again, kept sweating. Eventually I got onto a road that snaked up beside the highway, following its every turn but ultimately taking me to the same place. This road was pretty, single-lane, and mostly car-free. Cows and goats on the side of the road, flowers, a farm shop, some horses grazing on white and purple clover. This is how I had pictured the United Kingdom of Great Britain in Jane Austen’s novels. It was beautiful. The clicking of my bike and the sounds of my laboured breathing faded away for a minute. I basked in bliss. I felt fleetingly but overwhelmingly that the world was a serene place of beauty and peace, that everything was going to be okay. The feeling was all that mattered.

When I finally rejoined the real world at a roundabout that crossed the highway, I had made it to East Motherhill. I realised I was actually going to be early and so I moseyed through a com munity park, gliding along on my click click clickety rickety bike. Oh, how I loved this bicycle. Old faithful got me here in one piece. I arrived at the practice, and a friendly middle-aged man in scrubs greeted me. It was definitely Dr. McInnis because Bethany looked just like him. ‘How was the ride?’ he asked me. ‘Oh, lovely,’ I told him. ‘A bit spontaneous.’ He smiled and said something about stretching my legs. I parked the bicycle near the bins (no lock) and proceeded to go wait and feel thirsty in the waiting room, maskless while everyone else wore a mask, until I could bear it no longer. I approached the receptionist, a lovely round woman, to ask her if I could please get a drink of water. She couldn’t believe I’d cycled all the way there from Nigel House. ‘I cannae believe you’ve come with yae bike! I’ve ne’er seen someone arrive by bicycle fae so far away.’ I must’ve looked desperate because she acquiesced without a fuss despite the water dispenser being technically out of service due to Covid. I sat down, relieved, drank from my tiny disposable plastic cup. The jig is up. I had made it.

When my head hurts so much I can’t tell which way is up and my pillow cannot seem to be deep or soft enough to accommodate my mind in its entirety

The walls of my bedroom become a border beyond which I cannot penetrate, and do not matter anyway Everything is happening in this room

Every thing

Me, tiny fleck in this universe

A molecule of water in the vastness of the ocean

A grain of sand

Tumbling in a direction chosen only by its surrounding environment

Thoughts rushing in, out squeezing between and beside one another

Like a traffic jam happening at breakneck speed

Like one of those timelapses you see about a nameless city in China, integrating its new transit solutions

Except for the city is your brain

The transit solutions are your thoughts

And the overwhelming busyness is the fact that you won’t be sleeping much more tonight

But the good thing is that there is an inextricable link between the body and the mind

By occupying your physical medium, your brain can be distracted from itself

Focus on your breath

In, out Get lost in your work

It’s okay not to think

Shelan Zaynah | Shelan is a PhD student in psychedelic research at University College London.

What exactly is N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (commonly known as DMT) and why all the hype?

DMT is classified as a ‘classical’ psychedelic and is one of the only psychedelics to have been found endogenously—naturally present within the human body. Trace amounts have been identified in the brain, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid. DMT is rapidly broken down by Monoamine Oxidase-A (MAO) enzymes, which explains why it has only been found in small quantities.

In nature, however, DMT is found in abundance. It is the active component of ayahuasca, a number of tisanes (a.k.a. herbal brews), and snuffs. DMT was first synthesised in the lab oratory by Canadian chemist Richard Manske in 1931 before being discovered in plants by Oswaldo Gonçalves de Lima in 1946. It was finally tested on humans by Hungarian chemist Stephen Szara in 1956 by means of extracting and administering it to himself (which would definitely not meet today’s rigorous safety and ethics standards).

Despite its late introduction to the Western world, this powerful hallucinogenic compound has been used for centuries in Central and South America during religious ceremonies. For peo ples indigenous to the Amazon, DMT is seen as a form of medicine and thus is also a staple of healing ceremonies. The leaves of the Psychotria viridis are rich in DMT and prepared for con sumption by combining them with those of the plant Banisteriopsis caapi as it contains MAO enzyme inhibitors, thus prolonging the effects of DMT by slowing down its degradation.

So what does being on DMT feel like? Although no two experiences are the same, a gen eralisation that can be made is that one will experience intense and profound visual and/or auditory distortions whilst under the influence. Users have reported intense feelings of con sciousness, an interconnectedness with the universe and the breakdown of all reference points and identity. Words that have been used to describe experiences with DMT are ‘weightless,’ ‘oneness,’ and ‘connectedness.’ DMT trips can be perceived as being very long, but in reality the average DMT experience lasts only 20 minutes.

DMT exerts its effects primarily through binding to the 5-HT2A serotonin receptors. It is also known to act on the sigma-1 receptor, but the effects of DMT action on this receptor are not well understood.

Why the big fascination with DMT then? Psychedelics are currently at the forefront of a lot of mental health research. If you haven’t already heard (though if you’ve ever opened

The Guardian, Scientific American, or any other pop science news publication, you probably have), we’re in the midst of a psychedelic renaissance. Research has shown improvements in mental well-being and perspective after DMT consumption, and it is thought that these pos itive changes are long-lasting. DMT has been found to increase neuroplasticity (the ability of the brain to change/adapt as a result of experiences) which may be the reason for its observed long-term beneficial effects.

Alright, shameless plug time—enter the UNITy project: UNITy stands for ‘Understanding Neuroplasticity Induced by Tryptamines.’ FYI, tryptamines are the class of psychedelics to which DMT belongs. The overarching goal of UNITy is to explore which brain networks be come plastic after DMT consumption, leading to positive changes in well-being. Plasticity has yet to be linked to subsequent changes in well-being in any of these real-world brain networks, and the UNITy Project will be the first to do so both in adults who are healthy and, building on our prior work, those who drink harmful amounts of alcohol. The UNITy Team will accom plish this using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of healthy and problem drinkers while they are experiencing a Dimethyltryptamine, or DMT, ‘trip.’

To find out more about UNITy please check out our website: https://www.psychedelicunit.com

For some cool (DMT-related) art, check out our UNITy artists: https://www.psychedelicunit.com/our-artists

To have a chat tweet me: https://twitter.com/SHELANZAYNAH

To read further: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25877327 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19213917 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35837277 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2018.00536/full https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4773875

Liam Vandewalle | Liam is a Belgian-En glish writer and medical student living in Glasgow, Scotland.

Drip, drip, drip.

Can you hear it? Come closer, listen harder. It’s the teasing, tantalising last crusade of the raindrop as it rolls down a withered ivy leaf outside your bedroom window. Or perhaps it’s the smooth medicine on the stand, in the bag, next to the bed promising health, promising life, promising you. It’s Juliet, holding a prop knife thick with thin blood rolling off, unsheathing, hitting the auditorium floor. Whatever it is, there is something beautiful and dangerous about that sound. At once constant yet unreliable. Because you can guess but never really know when the next one will come, will hit.

I read once that you can torture a man like that.

I listen to the faucet in the kitchen of my shared flat. Number 4 never really mastered the art of turning the knob an extra five de grees to stop the water squeezing out the scaled neck of the chrome tap. I have giv en up on trying to sleep anymore. The eerie small hour light has slid over each surface of my room and eyelids, entreating recognition. I grant it. I lift off the starched sheets and swing my legs, heavier by the day, off the bed and onto the floor. The first thing I see, as I always see, is the easel. I always see the easel first. Then I see what’s on it. I hastily cast my eyes away and grimace, as if at some porn when I am post-ejaculation. I unlock my door and feel my way to the bathroom, animated less by any real energy than by that reliable urge of a morning piss.

Drip, drip, drip.

I read once that you can split a man’s mind in two like that.

Drip, drip, drip.

Fuck. The cobalt blue on the brush can’t wait to escape from my creative impulse to make a more impressive-looking imprint on my bedroom floor. I stand, hands by my side, eyes aghast at the ‘it’ on the easel in front of me. The paint keeps falling. Each rebel, radioactive pearl resounds in my head. Each

one sings of an unpaid bill, a pre-mashed potato that I still have to buy. An empty line on my curriculum vitae which is now being filled with that cacophonous cobalt blue. Some days I al low exactly three salty confessions to ooze from my brain and out of my eyes. Just three, never four. They burrow their way out of their ducts and roll down my parchment cheek to the most prominent part of my jaw.

Drip, drip, drip.

I awaken at 2.53am sharp, according to the heater pipes and my phone. The 24-hour time overlays her face. I wait for the 3 to graduate to 4 so I can make out the pearl smile on her face. I glance at me, clean-shaven and lean and arm wrapped round her tighter than my palm around the graceful gullet of a bottle. The picture is old but it is my way of keeping her “good.” Behind the 4, behind the eyes linger the perfect poisonous pixelated black pupils made into rainbows by her. I smile at the picture. The sun falls onto her hair like a halo should in all those old Renaissance paintings. But the playful sun outside doesn’t do much to stop inside surreptitious teeth. Inside her it oozes in wait. I was there when they told her. The first thing she did was look at me and say “it’ll be okay.” The joke of it was that she didn’t fight for her, she fought for me. She held my hand. Even as hers shrank, even as it paled. The small muscles and tendons supporting her ring finger first became more pronounced, then were lost too. They told me she was going. They asked if I wanted to stay, and that if I did I should be prepared to see her ‘in distress.’ I read somewhere they called it ‘the death rattle.’ When you’re dying you hyperexcrete respiratory secretions into your windpipe and it creates this rasping, gagging sound. Like drowning. They tried to stop it, tried to plug the secretions with their medicines. But she kept secreting.

Drip, drip, drip.

My bloodshot eyes drink the liquid that spouts from the bottle. They orbit around my orbits and leak into my skull, silently filling each expansive sulcus. The memories resonate with each exploding orb, extracting discordant notes that scream silent howls. That sound haunts me. No matter where I go, where I turn, who I plead with, there it is. My mind is a dry salt block underneath it. And yet, I cannot live without it. Without her. I am an addict. My nerves rely ing, screaming for that short sharp assertive syllable to release those pretty liquid chemicals from my reptile brain into my blood.

Drip, drip, drip.

I thought it would be romantic to go back to the place where she had tripped that one time and fallen and scraped her knee and it had bled like mad. The brown and off-brown surrounding me and the tall trees and mud offer no comfort to me, but that’s okay. I forgive them. I was schismed as to whether I wanted the sound to be there or not. So in the end I left it to chance. I made sure not to check the forecast for rain at all in the last four days. In my left hand I held

the knife. I thought how funny it was that the last thing I had cut with it had been red onions and how I hadn’t cried at all. I close my eyes and listen to my surroundings.

The rustling leaves.

A babbling brook.

A gasp eaten by the whistling wind.

Drip, drip, drip.

What’s the hardest thing you’ve thrown away?

Bins (non-recycling, non-organic) represent a profound tenet of ancient as well as modern philosophy. The reader’s response to this may be healthy scepticism at best, and casual scoff at worst; regardless, both only bolster the argument presented in this piece. Consider briefly that the earliest waste management system dates back to as early as 6500 BC in the Fertile Crescent. Consider also that every society, every person and every cell produces waste. Be it urea or carbon dioxide or urine or shit or toxic fumes or radioactive sludge, our existence is interwoven with that which is a lesser side-product, a nuisance to our continued existence and convenience. The problem of the forced production of undesirable by-products confronts us all, and the receptacle into which we cast these ‘objects’ (by-products) has rarely been offered the limelight. Why should it? As a holder of our waste, it symbolises the very essence of that which is undesired, the contemptible. If a Hell of the household world were to exist, the bin (non-recyclable, nonorganic) would be it. There are plenty of other congenial and (perhaps even more) laudable household wares to consider thank-you-very-much (see blender, toaster, ceiling fan).

But I must drag you back. Because if bins are Hell, then who are we? For it is us, the homeowners and tenants who pick up that ‘reduced to clear’ clearwrapped tub of coleslaw (the reasons of which are beyond the scope of the present piece) only to leave it, stalwartly, on its lonely refrigerator shelf, all too soon shoved behind the veritable Monarchs of the Contemporary Fridge, namely barista potato milks and the compostable-but-not-biodegradable ‘plastic’ bags holding exactly 400g of purple sprouting kale. WE are the ones who reach into the limbos and purgatories and clasp it, then retrieve it, then cast an eye over the ‘thing’ and make the final guillotine decision baked into every choice in life: yes or no? In the case of our mayonnaisedrenched friend, the answer is all too easy: it has failed the test. It is not just undesirable, the way celery is undesirable next to a vegan biscoff-stuffed crumpet, but it is disgusting. The cutting electric dance happens in our insulate cortex that makes itself known as disgust. The decision is made in milliseconds: the guillotine falls and the slaw topples down just about as gracefully as a human head.

I argue that this decision is that which lends profundity to the philosophical ideal of the bin. In nature there exist mouths of emptiness into which cosmic forces tip that which is to be unmade: on an astronomical scale yawn the Black Holes of the Universe. In us there is neural synaptic depotentiation which facilitates the necessary and climacteric faculty of forgetting. Through these mechanisms things exit existence on some plane or another—smiting down old coleslaw is the same, with one crucial difference: that which enters a bin has been selected by us, a conscious mind, unlike that which enters a black hole, or a memory that is forgotten. It

raises the inverse equivalent of the epistemological question of knowledge, that is, forgetting, unmaking. Bins are the black holes we control, the condemnation to obscurity we have agency over. When we are burdened we must shed, but how can we know without a test or a scan that we are condemning that which is truly ‘bad,’ now and for FOREVER and for you and for all? What have you thrown away? Why have you done it? Was it easy or was it hard?

In Virgin train (RIP) cubicles in the UK, it was very reasonably asked of passengers to not flush a variety of oft-misflushed items down their toilets (see below). Included alongside these are presumably (?) less-often misflushed items that function to project a humorous and therefore relatable voice onto the capitalist (big fan) machine that is Virgin (it worked I LOVE IT take my money Richard ). Hilariousness aside, this poster also succinctly presents the problem with the agency described above. Coleslaw is easy to condemn to nothing, to the ‘Fogs of the Forget.’ But unpaid bills? Junk mail? Your ex’s sweater? How about a stuffed toy you bought but never got to give? A darkened photo of a room with a silhouette only you know the identity of? Objects which are not objects but people? Who gave me the authority to erase full people from my life? It is terrifying that you can plant your feet as firmly as you want, grip the handle of the bin as resolutely as you are able to, but that last, fatal impulse of release, of letting go is what makes you the terrible God in your own life.

What’s the hardest thing you’ve thrown away?

We avoid resting a lingering eye.

don’t flush

sanitary towels, paper towels, gum, old phones, unpaid bills, junk mail, your ex’s sweater, hopes, dreams or goldfish, down this toilet

Emily - Louise Hall is an artist & yogi in Glasgow, Scotland.

Emily - Louise Hall is an artist & yogi in Glasgow, Scotland.

Miriam Elhajli | Miriam is a multidisciplinary improviser questioning along the peripheries of sound, folklore, and eco-poetics living between Brooklyn & New Orleans.

Part of a larger poetry collection, “Elegy For Lungs” chronicles the intimate personal lament of a first-generation queer American as she reconciles her nostalgia for a promised return back to a utopic motherland alongside the stark realities of displacement and colonialism in the New World. Looking through a multigenerational lens, these poems ask who we become after naturalization—how does the spirit of our ancestral heritage resist erasure? How can the silences inherited be spoken for?

“It is not only air that one exhales but it’s a current which, according to mystics, runs from the physical plane into the innermost plane; a current that runs through the body, mind, and soul, touching the innermost part of life and also coming back; a continual current perpetually moving in and out”

“Breath is like a lift, a lift in which one rises up to the first floor, and then to the second, and then to the third floor—in fact wherever he wishes to go”

Hazrat Inayat Khan (The Music Of Life)

I

Caught in between the coil of inherited tongues, my upper lip my lower lip are a crosscurrent underneath this slanted bridge where the east river sinks ferries just for fun.

Half open I spill out can not find a container in which to retrieve myself and you are no longer beside the pier, with a spare handkerchief in your raincoat to place into my hand, without looking, and wait until I can catch my breath. (You never asked me for an explanation.)

Listening to the drone of the fisherman’s reel, We admit to forgotten family recipes. Was it saffron or mustard seed in the secret jar of spices left behind? If only I could remember the size of her palms I’d need no measuring cup.

remedy diner (april 2021)

I will never write anything down I will never write anything down I will never write anything down I will never write anything down I will never write anything down I will

Not write anything down I will not write anything down I will not write anything down I will not write anything down I will not write anything down I will not

Write anything down I cannot write anything down I will try to write anything down I will never try to write anything down I will not write everything down

I downright or else write everything up

Never write anything down

Never write anything down

Never write anything down

Never write everything down

Never write everything down

Never write everything down

Down I anything write

Write I Down everything

Down down everything I write W irte ownd ythingever ewrite I thing I thing I thing I thing I thing I thing I thing I think I ching I ching I ching I ching I think I thing I think I thing I thing I thing I thing thing thing thing disconnected suffocated text that is not what I meant at all

act seventeen scene two thousand; miscommunications libations pay attention to the notes ringing

....false note .........false note ................ false notes........ false note...... ......church bell................. false note........pause..... jackhammer.....exhalation..... ... .. ...false note........... ya know sometimes you’re full of shit!

not one word rannnnnnngggggg metal chime brass silver truth quantum particles agitated by your deadpan indifference towards cosmic nuance input input input 9V to 12V to 16V EXPLOSION

no one drags me to church anymore but it’s Easter Sunday on 11th & C so I celebrate resurrections & my weekly unemployment claim at the dilapidated corner chapel with inviting windows.

the Dominican preachers wife doesn’t know what to make of me as I enter late to service with carpenter pants on inside out & a stain on my vest. I catch her sideways glance containing the unspoken reminder that I am no longer a child. No longer unnoticed when blowing out rows of votive candles, no longer protected when walking behind my grandmother, pinching her elbow, as we pause in line to receive confirmation.

I am held accountable now and have to explain myself this afternoon— my improper attire, shaved head, armpits.

When dedicating your time to creation, you must remember life comes first. This is the foundational instrument in which you will play a most divinely tragic hymn. Life as in the cardinals call at dawn, as in your bare bloody feet getting pierced by safety pins, life as in the inevitable realization of a love that’s run its course.

The first instrument you will need to receive aliveness is your body/spirit. This vessel needs to be emptied out in order to become a net and instrument to receive and resonate. Find a toothpick and begin to scrub out the tar lodged in your jugular. After the physical has found a semblance of equilibrium you are ready to catch.

The second instrument you will need is a sieve. The more refined sieve the better, one in which you can part an atom is ideal. Then with all the experiences accumulated, pressurized in the corners of your consciousness, twist your wrist downwards and pour (slowly darling, so as not to spill please) and witness the distillation. Now concentrated into a form of spirit, alcohol, or material, the final outcome is a pure expression. In order to align oneself to most fully receive the emergence of a song (or any receptacle of form), it is best to spend an afternoon watching the theatrics of the ocean, ever-expanding and contracting, reducing a boulder to a grain of sand through sheer will and repetition. Does the elemental dissolution of water and rock occur in their meeting? In the colliding shock of their encounter where all sense of separateness is shattered by a subterranean fault line erupting? The boundaries are unclear of creator and created—the action and its consequences are what remain. Observe the ocean with your heart-eye; do not try to make sense of anything.

The final instrument before returning to the head of creations wheel is the consciousness of the human and non-human entities who will interact with your expression through their senses—tentacles of nerve endings. Sonic, visual, sensorial, or telepathic, the expression will

meet another filtration organ and morph. This is a process of translation where each witness’s “image-repertoire,” as Roland Barthes so exquisitely puts it, meets you at the nexus of your expression to reinterpret your language using their own intimate mythologies. Another word to describe this process of transfiguration is alchemy. It is a splintering off, like each petal of the sunflower, your expression has now refracted. The seed of your expression has become a field of marigolds – how miraculous. Remember, you can only make sense of the ethereal chaos temporarily. Enjoy the catharsis of your radiating creation—go tell someone you are in love. There are forces at play beyond comprehension and all we can do is watch the children light fireworks at midnight along the shoreline’s horizon.

Franz Hildebrandt-Harangozó | Franz is creating and performing shows in the Berlin Planetarium. He studied and now teaches philosophy at Humboldt University.

In Philosophy we discuss a lot of things, but our main questions can be found in:

Metaphysics: What is the nature of reality?

Epistemology: What can we know?1

Philosophy of Mind: Who are we?

Ethics: What should we do?

A subcategory of Metaphysics is called ontology.

Ontology: What is the world fundamentally made of?

Used as a noun, ontology becomes a perspective that a person can have on the world and differ ent people entertain different ontologies. The French philosopher René Descartes for example was a dualist which means he believed that there are two different substances that make up the world: an extended physical substance (res extensa) and a mental, non-extended, non-physical substance (res cogitans). Some other common ontological stances are non-dualist—i.e. mo nist—stances in the sense that their proponents deny the existence of two separate fundamental substances in favor of a unified principle. Some think of this principle as one of materialism (everything is physical) and some think of it in an idealist way (everything is mental).

You are entertaining an ontology as well, whether you constructed it consciously or adopted it in an unconscious manner. Take a minute to think about your ontology. What is the world fundamentally made of? What is really going on?

Chances are that you are leaning towards a dualist conception, generally thinking of the world as something physical but leaving a few dualist backdoors open when it comes to conscious experience, love, free will and related ideas.

In contemporary science, those backdoors are mostly closed by shutting down the intuition pumps that kept them open. But still, the resulting ontologies do not pan out in a productive way.

¹ Note that the answer to this question will inevitably put constraints on the space of possible answers for the other three. In this sense the title of this article “fix your ontology” will involve fixing our epistemology first.

The prevalent metaphysical position of our time is strong physicalism.

This position assumes the epistemological primacy of physical interactions.

In the current version of strong physicalism, the phenomena in the universe are caused by matter/energy and the physical laws that govern them, i.e. the phenomena of the universe, including minds (which are a subset of the phenomena in the universe), are then the conse quence of quanta and their interactions (Bach, Verdicchio 2012, S. 17).

Here many people nowadays are left with the ontological intuition that at the lowest level there is this continuous space in which matter and energy interact and this gives rise to everything else. But in that lowest level sense, there never was any matter or energy in the first place. We made them up. To show this I will present the concept of epistemological computationalism.

Epistemological computationalism2 is not compatible with the notion of strong physicalism, be cause it shifts the epistemological primacy from matter/energy and the physical laws that gov ern them to information (i.e. discernible differences) (Wolfram 2002).

It does so on the grounds that all possible observations of the universe do not reveal matter or energy, but information.

Matter/energy and physical laws can never be observed. All observations only consist of dis cernible differences.

Regularities in the way the discernible differences are correlated can be discovered and formu lated as entities. These entities can then be used as predictive models of further regularities in the correlation of the observables.

An example from our everyday experience are movies. Let us suppose we have an old-school analogue video projector and we are watching a movie on a big screen. In this movie there is a billiard scene. If we assume that this scene consists of people hanging out in a bar, making billiard balls hit each other, we can understand what is happening on the big screen

We can even do this in a predictive way: even though it is a movie, the billiard balls will most likely not get up from the table to order a drink at the bar. No! The Billiard ball moves because it got hit by another one, we think to ourselves. In this way we are watching the movie scene and we subconsciously constructed billiard balls, people, causality and momentum—a predictive set of made-up modeling entities—to understand the dynamics on the big screen.

² In different contexts also called functional constructivism - see Bach 2009, p.8 or von Fo erster & von Glasersfeld, 1999.

And it works!3 But at the same time we obviously know that all these things do not exist on the big screen. There are no billiards balls, no people and no causality. All these dynamics are byproducts of a video projector going through a series of slides. On the big screen there is only the light of the projector in varying intensities—a dance of discernible differences4.

If you want to think of it in a more general way: you being born and growing up is basically the same as you watching a continuing (multi-modal interactive) movie. All your brain gets is a stream of discernible differences and to understand and predict the patterns in this stream. Your brain constructs models like colors, people and causality (and your own self, but let’s not get too Buddhist right now—the models our brain creates are increasingly more complex than the models used in the movie example of course). But still—there are no billiard balls, no people and no causality in the real world.

In an even bigger and more extensive way, all of this happens as well when we are not watching a movie or when we grow up but when we try to understand the world5. In this case the big screen is the set of all observations (a finite vector of bits). To understand the dance of discern ible differences in this bit vector, we use a set of made-up modeling entities once again.

A possible predictive set of constructed entities consists of matter/energy and physical laws. This set of constructed modeling entities is captured in the idea of the physical universe. The physical universe is a possible theory that encodes the observed data6 (Bach, Verdicchio 2012, S. 17).

Among all the other discovered possible theories, it has been so successful that it stirs meta physical confusion in philosophy, leading to sets of beliefs that assume a metaphysical primacy

3 Sometimes it doesn’t work. If there is a malfunction on one of the slides or in the video pro jector, we will get artifacts on the big screen that are not explainable by the dynamics of our made-up entities and we have to take a step back and look at the video projector itself to un derstand therm.

4 Discernible differences are usually described by mathematical functions. Functions are a mode of description. They describe the abstract shape of changes. Math deals with all possible shapes of abstract change. Numbers for example are an ongoing successor function which can be given arbitrary shapes by using a couple of other functions which we call logical operators. Numbers are in some sense an abstract synthesizer with numbers-towers as the substrate and the logical operators as the interface.

5 Movies (simulacra) and computer games (simulations) are controlled pattern generators— they produce discernible differences which can be predicted with the help of made-up model ing entities. From our perspective, the universe is a controlled pattern generator as well.

6 Here, matter and energy are possible orderings that can be constructed over the discernible differences. Physical laws are propositions regarding the way in which the adjacent differences are correlated.

of the entities making up the physical universe, while treating all other discovered possible theories as being theories about the physical universe7.

The confusion disappears by locating the physical universe and all other discovered possible theories in the same domain—as valid encodings of the observations—and, in that, ascribing epistemological primacy to the observations themselves, i.e. to discernible differences.

This makes the notion of an ultimate physical substrate unproductive since it is empirically inconvertible and unobservable. In that, even if one starts out from a physicalist stance, they will arrive at epistemological computationalism just by excluding superfluous concepts from the physicalist approach (Bach, Verdicchio 2012, S. 17).

Now that we have fixed our ontology, we are freed from the shackles of a specific model and we can continue to explore the world in a productive way. A theory of everything does not need a physical substance. A theory of everything will be the set of the (most elegant) func tions—the correlates of all observations.

Bach, J. and Verdicchio, M. (2012): “What kind of machine is the mind?”, Turing-100, S. 16-19. Bach, J. (2009): Principles of Synthetic Intelligence: Psi: An Architecture of Motivated Cogni tion. Oxford University Press, Oxford Series on Cognitive Models and Architectures. Foerster, H. von. Glasersfeld, E. von. (1999): Wie wir uns erfinden. Eine Autobiographie des radikalen Konstruktivismus. Carl Auer, Heidelberg. Wolfram, S. (2002): A New Kind of Science. Champaign, IL: Wolfram Media.

7 This leads to the problem that other theories have to grapple with the model-specific con straints of the physical universe in order to be a coherent theory about it. The contemporary impotence of the philosophy of mind can be partially ascribed to this problem (the other fac tors being ontic commitments to artifacts of our mind’s world models and the use of non-for mal and incoherent languages).

Tevin Muendo | Tevin Muendo makes documentaries and writes, among many other things. He currently lives in Hackney, London.

This poem was written using only quotes from real Instagram captions.

Oh helllllo ��

My mind says as I look in the mirror

So sexy xx

U so pretty xxxx

I produce my phone, sometimes From out of my purse, to crystallise my validation

Each time, laying my own bed of nails

ARE YOU EVEN REAL in public, thoughts flood my mind...constantly “pretend ya don’t know the photos being taken” Plandid? ��

Socialising has gotten to be exhausting Anxiety at an all time high Look at her! �� Can I just be you �� until Finally, Home xx

Skin dabbed with armour piercing wipes, Miss this face xx I think

Term resumes and so does the shop, you know? The one involving human stock, quickly on a rack spun girls and guys, we watch as humans become silk ties, first to go, always easy on the eyes, the yellows and purples subject to routine demise, can Disguise in a guise of un-wavered eyes

Have you ever seen the boyfriend stall? come you ladies! come one and all! We have gents of all stature, nice, or grim as grinches, we have guys for those of you who prefer the ‘inches,’ Or height?! Our most popular model is over 6ft tall, we’ll even throw in the massive ego for no charge at all

Have you ever seen the girlfriend market? where testosterone meets child-like shyness, date requirements are an initial kindness that you may soon retract when the inevitable dryness, takes effect, when you superficially select the opposite sex

Be wary when visiting this shopping centre, as I regret to say that once you enter, that you become pretty obvious to the opposite gender, that you’re quite a frequent date attender, but alas, enjoy this romantic bender, signed yours truly, a future date contender

Living with artists was far from being the idyllic experience that I had hoped it would be. I had spent the months prior stewing over my decision to accept a scientific research post at USF, which would end my year-long escapade and life in Amsterdam. I was going back to San Francisco, and needed every day dream possible to make the move more bear able. Now you may be thinking—you were dreading moving to San Francisco? Really? It was, after all, named 2020’s most livable city, and 2019’s, and 2017’s. The top spot had escaped from reach in 2018, when the big S had been edged out by the other big S, Sydney. This was only because San Fran cisco’s fentanyl crisis obtained more interna tional airtime in 2018 than it had in the past. Luckily, this detail quickly faded back into obsolescence, allowing SF to regain its right ful throne the following year. I know, I know, San Fran’ is objectively not that bad.

In fact, my dislike of the place is niche enough to be funny and maybe even interesting. After moving to London, I had it listed as my ‘per sonal hell’ on Bumble until I realised that it served its purpose as a ‘prompt’ by starting only terrible conversations. I would struggle to answer when potential suitors asked me ‘but why?’—my fake reasons for hating the Bay area are shallow (‘not enough cultural offerings! This place is void of refined civili zation. Plus, their MOMA sucks’) or sound overly politically correct (‘SF has lost all its grassroots anarchist charm and is shaped only by techy Silicon bros. Nothing here is actually Fairtrade. Everyone knows that

Cascadia’s only truly carbon-neutral farmto-table markets are in Sedro-Wooley in Northern Washington state). These remarks conjure an image of a spoiled-rotten rich kid or leftist hipster, neither of which I am exactly. I hated how others perceived me in San Francisco (which might suggest something about the things I don’t like about myself). But for now, enough: you’ll see why this is important later on.

My real reasons for hating SF and therefore dreading moving there were far too revealing and painful to share with a total stranger on a dating app. It had to do with living with art ists. Let me tell you about it.

Wonderful and generous Michaela had of fered me her room: it was in the heart of Haight-Ashbury and only a short run to the ocean for convenient early morning skinny dipping. In the middle of a housing crisis it was a no-brainer to accept her offer of a fourmonth summer sublet in a place she referred to as the ‘Green House;’ I put my reservations about moving to SF aside. There remained the issue of where I would live come Septem ber, but this was still in the distant future as far as I was concerned. Truly aeons away, ac tually, (when taking into account my history of precarious living situations) and could be dealt with at a later date.

My desperate self had leapt at Michaela’s of fer of a room: in I rolled with my assortment of junk. The aesthetic of most of my worldly possessions can be described as ‘secondhand

and nearly threadbare,’ perhaps ‘homeless’ if seen in the Tenderloin district (my stepsister re cently said I looked like I ‘lived in a charity shop’). Despite this, it all has a large (very unPC) carbon footprint—collected in flea markets and unnecessarily transported across the globe, only to be hoarded in piles. This junk is combined with ‘expensive yet impractical objects.’ For example, the Montblanc fountain pen my father gave me for no reason other than ‘everyone needs a nice pen.’ My best friend Eloise once remarked on the ridiculousness of this pen and suggested I sell it to pay 2 months’ rent in a nicer flat, as I was living in a different sort of shithole at that time.

I arrived at the Green House with my bags, shaky mental state and prestigious undergraduate student research grant at USF. I was to spend the summer ‘investigating the relationship between changing climate and surface hydrology in the Bay area.’ In practice, this involved weighing salt into carefully labelled bags resembling cocaine (at least, I pretended they did to make my life more exciting), calibrating electrovoltometer probes, dumping said salt in river and measur ing saltiness downstream to determine the changes in flow rate. And finally, processing the thousands of data points obtained during each collection using Matlab and Matlab’s extensive online help section. This help section was a godsend. Each time I struggled to use the correct syntax when looping ‘if-statements,’ or tried to figure out how to generate a topographic map using geo-points, I could simply consult the online help section and find an organised and rele vant list of possible solutions. I wished, at various moments, that I could peruse a similar online help section for the mundane problems of my own life. For example, how do I get a curry stain out of a brand new white mock-neck from COS ($129.99) that I had worn without removing the tags with the intention of returning it after wearing it for 8 hours whilst a plus one to a non-boyfriend’s aunt’s wedding? Or, how do I stop myself from checking my crush’s Instagram, Facebook, and Linkedin profiles daily (as well as those of his brother, mother, and punk band) even after they made it very clear that they weren’t interested in anything of any kind after three dates and one dismal night together? Or, how does one avoid the extra charge incurred when renewing a drivers’ licence they have knowingly let expire due to negligence, forgetfulness and feeling overwhelmed with the bureaucracy of modern life? If a Matlab help section existed for problems like these, my time in San Francisco may have been very different indeed.

For my first 4 days at the Green House, I was completely ignored. On the 5th day, and very much in passing, I finally met one of the flatmates, who turned out to also be a subletter. She seemed nice enough, but was Latvian and spoke only rudimentary English. Despite being ex perienced and even good at feigning the ability to speak a foreign tongue better than I actually do, this talent fell flat upon the realisation that this skill extends only to languages of Latin, Anglo-saxon or Germanic origin. Latvian was far too Eastern to fit my conjectural language babble so I contented myself with friendly-sounding noises and a hopefully kind demeanour. In return she fed me pickles and hard cheese and rye bread crisps. Her Soviet straightfor wardness was somehow familiar and even comforting in the Green House, where no one else seemed to care that I existed. However, my interaction with Illka was short-lived as she moved back to Riga within weeks of me moving in, supposedly to get her life and career in order. This

seemed strange to me, as she was living in the world’s most livable city and the Baltic states hardly bring to mind’ economic prosperity,’ but away she went, leaving me to my devices at the sad, lonely Green House. I know now I ought to have followed her to Riga.

Michaela had instructed me to ‘touch base’ with Simone and told me that she was in charge of the ‘space.’ I loathe expressions like ‘touch base’ and ‘space’ as I find them pretentious yet stupid sounding. They’re the kind of expression only used by either smooth-talking CEOs, yummy American dads or woke ‘artists.’ The use of these terms alone should have been a red flag, but I was too committed to my lack of housing to back out. My belongings were already strewn around the room in vague piles, not properly put away as this would imply that I was staying a while (after moving in, my mother implored me to send her pictures of my setup— she knew about the piles and was afraid this would happen as she associated piles in my room with piles in my brain). I tried in vain to track down Simone so that we might touch each oth er’s bases, but she was nowhere to be found. It seemed as if no one lived in this house. Large, wooden, and old, it creaked and swayed when the ocean breezes turned into strong winds that churned the water into white caps that bubbled and sprayed at their peaks. The frothy behe moths would then crash into the massive rocks and logs of the West coast beaches. When these winds came, I imagined the House’s green boards getting ripped off, leaving the old thing bare and naked and the dull grey-brown colour of old barns in the American Midwest. The House had an odd feeling of vacancy even though four people supposedly lived here. Its best feature was a massive south-facing wrap-around covered porch which received sunlight in the morn ing. I had taken to sitting out on the porch and reading my book on the wicker bench. When I did this, I felt like an imposter—I felt as though the entire neighbourhood was watching me sit on this porch. I was as discreet as possible in my ADLs (Activities of Daily Living; one of my favourite acronyms1) to avoid disturbing the ‘Artists.’ But I was weak and sat on that lovely porch anyway, the morning light casually making an appearance despite the actual scarcity thereof (*San Francisco is not known for its rays of sunlight).

Shortly after Illka’s departure and after living in the House for nearly two weeks, Simone appeared on the porch as I was reading the Bell Jar on a Sunday morning. ‘Hey,’ she said. Her eyes were the colour like the Wapta icefields on an overcast day, and I watched them look me up and down, sizing me up like a judge might size up an auditionee before their performance for the role of Frenchy in Grease (a character who seems important at the beginning, but who the judge knows will ultimately disappear halfway through the show for no reason other than ‘does not add to the plot’). I put down my book, wore my most luminous smile and intro duced myself. I made the usual introductory talk, smiled some more, asked questions, laughed

¹ It may seem odd and contradictory that I love acronyms like ADLs while actively denigrating other colloquialisms. I love them because they allow us to efficiently describe complex yet te dious things through the use of simple letters. They are also sometimes an inside joke with myself some acronyms are so ridiculous that using them ironically makes me laugh. Sort of like certain emojis (have you ever seen cat face with heart eyes ��).

politely. It was social interaction at its finest. She explained to me the history of the Green House, about how the city had bought the neighbourhood and slated it for demolition, about how the community in the 60s had revolted and saved the entire Clayton Street block. The lease had been grandfathered down through generations of self-proclaimed hippies. Simone seemed nice, but not warm. Actually, there was something distinctly glacial in her demeanour. Now, one may be thinking that this could just be my perception and not an objective descrip tion of her personality. After all, you can’t please everyone. ‘Trop plaire est une plaie,’ which means that ‘to please too much is a wound,’ or a less literal but more accurate interpretation, ‘don’t try to please everyone as this will cause you injury.’ This is a quote proclaimed by one of my favourite pieces of Parisian street art ever, found in rue François Miron (please see below).

I loved it so much that I’d written a poem based on it as a letter to Eloise when she was strug gling with addiction to self-destructive substances, habits, and thoughts. I find it so wholly encompasses the injury and hurt one inflicts on themselves when trying to please—whether that be a boss, a lover, their father, or society at large. The poem goes like this:

I’m glad you told me Though I had guessed it before You can see it clearly, easily When you’ve had it too

The echoes of desire the line between want and need becoming clouded, grey tornadoes in my head How much longer? will i be able to get what i need? today? ‘wow i feel good’ (alone)

But really It’s like trying to fill a leaky watering can With the hole growing larger and larger The more you try to fill it

I’m glad you told me Because in some way it makes it better Because I know how hard it can be to say it Out loud

It’s easier to bury it deep, Under the baggy shabby clothes Under the cheerful voice Under the counting, the lead-pencil sharp focus on one thing, the only thing that matters

Even buried, it’s worrying Like a plastic bag that somehow got into the compost heap and won’t decompose Like an easy to hide blister that you know could burst any day And I know it’s

Makes you feel whack, etc

But I guess it’s good to remember: It’s not forever Allow yourself the same leniency As you would a child

Would you tell them ‘no’ How far, long, hard would you push them with their innocent bodies and minds Or wouldn’t you?

But I’m derailing the story—back to frigid Simone. Even my friend Eloise who often struggles to pick up on subtle social cues or reactions, had remarked unprompted on her iciness following their first interaction. My gregarious and extremely perceptive friend Katie had actually coined the phrase ‘cold hippies’ to describe Simone and the other housemates, who will be introduced short ly. She was nice enough—not outwardly grumpy or rude at the outset. But the more time I spent in the Green House, the more I noticed the inconsistencies between their talk and their walk. Communal living, political correctness and ‘creative awakenings’ became tropes for selfishness, arrogant moral superiority, and bad art (sorry, I know that the value of ‘art’ is in the eye of the beholder. But what is to follow was so disturbing and un-enticing that it forever tainted whatever creative juices they may have had to offer). I would later find out that the rare occasions when they acted ‘nice’ were merely strategic means to an end.

entire month. I paid the rent on time, I bought toilet rolls when we ran out (no one else was inclined to do this). I washed, dried, and put away my dishes when I cooked. I tried in vain to forge friendships with the Green House in habitants; our interactions remained stilted. Throughout this period, I was not asked a sin gle question. I couldn’t decide whether it was my personality that inspired this indifference, or a morbid lack of curiosity on their part.

A month in, I shaved my head and re-pierced my left nostril. This sounds more dramatic than it was; my hair was already cropped quite short so it was not a huge change. However, the #1 buzz over my scalp and small silver ring in my nose turned out to be significant. I must have looked more an drogynous and thus more ‘interesting’—end result: the roommates gave me more of their time. Simone would insinuate questions re garding my sexuality, which I am quite cer tain was a form of flirting as she was openly (and condescendingly) bisexual. I tried hard to dissuade her from these conversations, and generally suggested heterosexuality ‘as far as I knew’ while not totally excluding the possibility of bi-curiosity as the new haircut, nose ring, and speculation surrounding my orientation had given me a sort of social cap ital in the House (I would later consider my self to be on the spectrum of bisexuality, but the label freaked me out and anyway I did not want to act patronizingly different as they did, making straight people feel as obsolete as sex toys from the 1950s). I played it cool. However, thanks to my haircut, my status changed from artistically illiterate scientist to possibly-BIPOC comrade. That is, until Si bellius moved in.

I kept to myself the following days, which turned into weeks, and eventually into an

To be continued, in issue 2.

Duc Vinh Nguyen | Duc Vinh studies art history and computing science in Berlin.

Im Sand sitzend horche ich dem Stürmen der Meere. Der Wind sorgt für ein nie endendes Rauschen. Links sehe ich zwei Muscheln, wie sie sich im Wind aufbäumen, rechts in der Ferne einen einsamen Fotografen, der mit sich im Reinen ist. Seit Stunden versteckt sich die Sonne schon hinter den Wolken. Leicht scheinen die Vögel vor dem grau, gelben Himmel zu schweben. Ratlos sitze ich in meiner orangen Hose hier, und warte auf das baldige Ende.

Heiligenhaft, 14.08.21

Sitting in the sand, I listen to the storm of the sea, With the wind providing a never-ending roar.

On the left, I see two shells rearing up in the breeze On the right, in the distance, a lonely photographer at peace with himself.

The sun has been hiding behind the clouds for hours. Birds seem to float lightly in front of the grey and yellow sky. Perplexed I sit here in my orange trousers and wait for the imminent end.

Carla Theuring | Carla Theuring is interested in different ways of healing the mind and body, such as through art and ergotherapy. She currently studies social work in Berlin.

Noa Amson | 09.12.2019

Stepping outside into the brightness of the day For the first time

The white light, blinding The cold air

The ground hard from last night’s frost

The world looks white

A huge lake, shimmering at the surface

The waves invisible despite the wind

But I’m running, running Tears streaming

Either from the wind, the light, or emotion I can’t tell

And the dome of sky, deep blue in the middle Paling to nothingness at the edges Bathed in the white light of day

Then I’m laughing

Because of the world’s beauty And that I get to be a part of it

What more could you, me, or anyone else ask for A beautiful world And the knowledge that it’s here to stay Until the day I won’t Anymore

1. What is Evolutionism? (Welcome to the second outrage against humanity).

Originally published in 1989, the book ‘Evolution: The History of an Idea’ by the Irish historian Peter J. Bowler has been, and still is, an influential work in the field of the history of science. The book gives a thorough account of the history of evolutionary thought over the past few centuries. Here you will get a short summary of Bowler’s general conception of the idea of Evolutionism

The history of evolutionism is best captured in the transition from a static (divine) to a dy namic (natural) model of the world.

The Darwinian revolution began before Darwin was born. Evolutionism is not the same as Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection. Bowler uses it as a general term to describe any theory arguing that lifeforms on Earth used to be different than they are today.

A crucial element leading to the rise of evolutionism (in whatever form) was what Bowler calls the expansion of the time scale (Bowler, 2009, p. 4), i.e. the insight that the Earth and the uni verse itself might be quite old and long-lived. Geologists played an essential part in expanding the time scale by showing that the Earth must be far older than the Judeo-Christian estimate, nailed down by James Ussher to a mere 6000 years.

The idea of an evolving physical universe (Bowler, p. 3) laid the foundations for thought mod els assuming that radical natural change concerned living things as well. Fossil evidence also played an important role in the development of evolutionism. Once paleontologists discovered fossils implying that the Earth had been inhabited by a vast number of unknown organisms in the past that were no longer around, it became more and more obvious that the biblical story of creation couldn’t be taken as literally as had been previously assumed. These fossils, which had been found in a number of different sedimentary layers, suggested that there had been more than just one act of divine creation, if divine at all.

These findings did not change the old worldview overnight. Rather, they initiated a step-bystep process in which numerous emerging scientific discoveries and theories became embed ded in the existing model of divine creation and religious belief. Therefore, evolutionism does not entail atheism.

At this time, many people believed in the fixity of species, or the idea that even if there had been more than one act of creation, every species was still designed by God and was part of a fixed

pattern where each design served a specific purpose. This argument from design states that the finely tuned and highly complex appearance of each species is too perfect to have developed from natural processes and therefore hints towards a teleological explanation of organic structures (Bowler, p. 6). However, evolutionism does not equal transmutation (gradual or radical change of one species into another). Therefore, the argument from design could still be com patible with certain evolutionist perspectives (e.g. if species are designed, then go extinct, after which new species are designed and take their place).