Program notes by David Jensen

PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY

Born 7 May 1840; Votkinsk, Russia

Died 6 November 1893; Saint Petersburg, Russia

Serenade for Strings in C major, Opus 48, TH 48, ČW 45

Composed: 21 September – 26 October 1880

First performance: 30 October 1881; Eduard Nápravník, conductor; Russian Musical Society

Last MSO performance: 14 January 2012; Evan Rogister, conductor

Instrumentation: strings

Approximate duration: 28 minutes

By his middle age, things had finally begun to turn around for Tchaikovsky, and for a brief few years in a life he felt was otherwise interminably difficult, his artistic efforts flourished. Following the disaster that was his attempt at marriage in the late 1870s, he spent several years travelling Europe and Russia extensively and composing freely. Having procured a steady income from Nadezhda von Meck, the wealthy widow of a railroad magnate, in 1876, he had resigned his post at the Moscow Conservatory and withdrawn from worldly affairs to better give expression to his interior experience. Over the course of the next decade, he would finally enjoy a burgeoning reputation as one of the most authentic voices in Russian classical music.

It is one of the great ironies of time that artists do not live to savor the enormity of their influence on the trajectory of history, but were it not for Tchaikovsky’s own dismal point of view toward life, much of his finest music may never have come into conception. So it was in the autumn of 1880 that he reported an otherwise typical episode of malaise to his patron: “Scarcely had I begun to enjoy a few days’ leisure than an indefinable mood of boredom, even a sense of not being in health, came over me. Today I began to occupy my mind with projects for a new symphony, and immediately I felt well and cheerful. It appears as though I could not spend a couple of days in idleness ... there is no other occupation open to me but composition.” Within a few weeks, the “new symphony” rapidly took shape as the serenade for strings, written “from an inward impulse; it is something I felt deep within myself, and therefore, I dare to think, is not without real merit.”

The opening movement is cast as a sonatina, or “little sonata,” a relic of the Classical period; as a conscious homage to Mozart, one of Tchaikovsky’s favorite composers, its structure is defined by two central themes left untreated in the absence of a typical development section, framed by an introduction and coda built upon a sweeping chordal motif. The ensuing waltz, the briefest of the four movements, underscores Tchaikovsky’s supremacy as a master of dance music, characterized as it is by its charming tunes and lilting phrase structures. The third movement, an elégie marked by an inward character, intimate voicings, and sprawling lyrical lines, forms the emotional peak of the serenade. Following a slow introduction, a rollicking finale sets two Russian folk songs — “On the Green Meadow” and “Under the Green Apple Tree” — in a proper sonata form, replete with a brilliant development section, before the opening material of the first movement returns, now overlaid with the finale’s infectious energy, imparting a sense of immense grandeur in having “arrived” once more at the beginning.

Before its first public performance in the autumn of 1881, the serenade was read in a private concert given by the students and faculty of the Moscow Conservatory on 3 December 1880 as a surprise for Tchaikovsky, who was visiting after an extended absence. “For the moment,” Tchaikovsky wrote to von Meck a few days later, “I regard it as my best work.”

RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS

Born 12 October 1872; Down Ampney, England

Died 26 August 1958; London, England

Tuba Concerto in F minor

Composed: 1954

First performance: 13 June 1954; John Barbirolli, conductor; Philip Catelinet, tuba; London Symphony Orchestra

Last MSO performance: MSO Premiere

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling on piccolo); oboe; 2 clarinets; bassoon; 2 horns; 2 trumpets; 2 trombones; timpani; percussion (bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, triangle); harp; strings

Approximate duration: 12 minutes

“Ralph Vaughan Williams has written a tuba concerto and wants you to play it at our jubilee concert in June.” This is the telephone call Philip Catelinet remembers receiving only a few years after his appointment as principal tubist for the London Symphony Orchestra. The moment must have felt surreal: to have a premiere from Britain’s most distinguished living composer land in one’s lap is no small prize, but for an instrument largely seen by popular culture as something slapstick, for which no one had ever bothered to write a concerto, it was daunting. Even the press expressed its skepticism in advance of the performance, insinuating that it couldn’t have been more than a flight of fancy worked up by an eccentric artist entering his ninth decade: “He will need all his breath. … Twenty minutes solo work is a tough proposition.”

Vaughan Williams’s career in music had developed only gradually. He spent nearly a decade on his collegiate education, attending both the Royal College of Music in London and Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. He took lessons with the preeminent German composer Max Bruch for several months in 1897 before receiving his doctoral degree from Cambridge a few years later, and by the time he began studying with Maurice Ravel in 1907, he was already collecting English folksong as source material for his work. Though he had been working to refine his stylistic means, it was Ravel who helped Vaughan Williams escape the sway of German Romanticism; coming to rely on a lighter, more spacious approach to orchestration, he began incorporating modal elements and shaping his melodies in the manner of the English folk idiom. In the intervening 30-odd years that then separated him and his tuba concerto, he would teach for 20 years at the Royal College of Music, serve as president of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, lead The Bach Choir of London as their music director, and earn recognition as the leading exponent of English music following the deaths of Elgar, Delius, and Holst.

A product of his mature voice, the tuba concerto turned out to be anything but an act of whimsy. With military pomp, the opening movement explores the instrument’s range and agility, alternating between simple and compound meters with a great deal of rhythmic ingenuity. In contrast, the central romanza breathes freely, a respite from the more technically demanding outer movements — a gently flowing stream of semiquavers in the accompanying strings provides an almost choral canvas as the soloist rhapsodizes above the orchestra’s continuously shifting tonal centers. The finale, lasting only about three minutes, pushes the instrument to its limits: marked “alla tedesca” (“in the German style”), the short three-part form features, according to the composer, a German waltz at its heart, and following a short cadenza, a series of descending triplet figures brings the brief concerto to a rousing conclusion.

The first of its kind, Vaughan William’s tuba concerto enjoyed not only a successful debut, but sustained popularity, finding a permanent place among the instrument’s repertory. But such were Catelinet’s own misgivings that he had even asked his wife not to attend the premiere: “In the past, the tuba has been treated as a rather comic instrument, and I did not know how the public would react. If I had to suffer, I would rather suffer alone.”

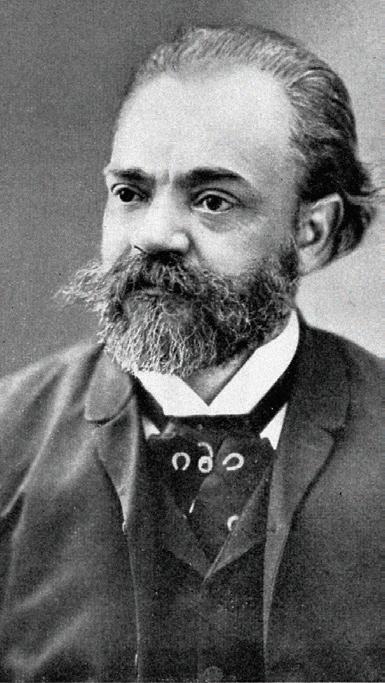

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK

Born 8 September 1841; Nelahozeves, Austrian Empire (now the Czech Republic)

Died 1 May 1904; Prague, Czech Republic

Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Opus 70, B. 141

Composed: 13 December 1884 – 17 March 1885

First performance: 22 April 1885; Antonín Dvořák, conductor; Philharmonic Society of London

Last MSO performance: 5 March 2016; Joshua Weilerstein, conductor

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling on piccolo); 2 oboes; 2 clarinets; 2 bassoons; 4 horns; 2 trumpets; 3 trombones; timpani; strings

Approximate duration: 35 minutes

“This main theme occurred to me upon the arrival at the station of the festival train from Pest in 1884.” So reads the handwritten note Dvořák left in the manuscript of his seventh symphony. A habitual trainspotter, the flash of insight was the composer’s intuitive response to what he saw on the platform during his daily walk to the station: hundreds of Hungarian and Czech nationals were traveling to the National Theatre in Prague for a concert staged in support of their nations’ struggle for independence from the Hapsburg dynasty’s Austro-Hungarian empire. The moment must have felt portentous. On the cusp of a hard-won international career, he had begun to recognize his responsibility to posterity — as well as his homeland — as a symphonist of the first rank.

Only a few months earlier, Dvořák had found unqualified favor among the British. A wildly successful staging of his Stabat Mater at the Royal Albert Hall in 1883 had resulted in a series of engagements by the Philharmonic Society of London, which bestowed an honorary membership and commissioned a new symphony from him in June 1884. A recent performance of Brahms’s newly minted third symphony (a colleague whose unflagging support had cleared Dvořák’s path to fame and fortune) stoked the fires of his imagination; writing quickly in a blaze of inspiration, Dvořák described his fervor in a letter to his friend Antonín Rus: “I am occupied at present with my new symphony (for London), and wherever I go, I think of nothing but that this new work must be capable of stirring the world — may God grant that it will!”

Consciously written to make as profound an impression as possible on the international scene, Dvořák’s seventh symphony marks a deliberate departure from the Slavic idiom that had defined his musical voice up until that point. The model here is undeniably Beethovenian, but the miracle of the music is that despite the scale of its drama and its insistently impassioned quality throughout, its craftsmanship remains as formally rigorous and thematically sophisticated as anything conceived by the late master. The British musicologist Donald Tovey identified the seventh as Dvořák’s finest contribution to the genre, placing it “among the greatest and purest examples in this art-form since Beethoven.”

From the opening theme introduced by the lower strings, the music of the first movement — and the symphony as a whole — is unsettled, brooding, and wrought with anxious tension. The bucolic second movement which follows (which Dvořák described in a footnote as “From the sad years,” a possible reference to the deaths of three of his children in infancy during the late 1870s) contained, according to the composer, “not a single superfluous note,” its pastoral character reflecting his preoccupations with “Love, God, and my Fatherland.” The scherzo here infuses an otherwise Classical structure with a wild, roiling vitality, while the finale culminates in a brilliant display of motivic ingenuity, its blazing, gloriously rendered coda sounding a bonechilling conclusion in D major.

Despite the work’s immediate success, publication became a different matter entirely. Dvořák’s German publisher, Fritz Simrock, tested his patience, first insisting that he required a four-handed piano arrangement, then altering the title page’s Czech spelling of Antonín to the Germanized “Anton.” Salting the proverbial wound, Simrock offered a mere 3,000 marks for the work, even going so far as to suggest that Dvořák quit troubling himself with symphonic writing entirely. Despite Simrock’s wheedling, the seventh’s unquestionable victory had convinced Dvořák of his worthiness as an artist; he successfully negotiated his fee and received twice the proposed sum.

2025.26 SEASON

KEN-DAVID MASUR

Music Director

Polly and Bill Van Dyke Music Director Chair

EDO DE WAART

Music Director Laureate

BYRON STRIPLING

Principal Pops Conductor

Stein Family Foundation

Principal Pops Conductor Chair

RYAN TANI

Associate Conductor

CHERYL FRAZES HILL

Chorus Director

Margaret Hawkins Chorus Director Chair

TIMOTHY J. BENSON

Assistant Chorus Director

FIRST VIOLINS

Jinwoo Lee, Concertmaster, Charles and Marie Caestecker Concertmaster Chair

Ilana Setapen, First Associate Concertmaster, Thora M. Vervoren

First Associate Concertmaster Chair

Jeanyi Kim, Associate Concertmaster

Alexander Ayers

Autumn Chodorowski

Yuka Kadota

Elliot Lee

Dylana Leung

Kyung Ah Oh

Lijia Phang

Vinícius Sant’Ana**

Yuanhui Fiona Zheng

SECOND VIOLINS

Jennifer Startt, Principal, Andrea and Woodrow Leung Principal Second Violin Chair

Ji-Yeon Lee, Assistant Principal (2nd chair)

Hyewon Kim, Acting Assistant Principal (3rd chair)

Heejeon Ahn

Lisa Johnson Fuller

Clay Hancock

Paul Hauer

Sheena Lan**

Janis Sakai**

Yiran Yao

VIOLAS

Victor de Almeida, Principal, Richard O. and Judith A. Wagner Family Principal Viola Chair

Samantha Rodriguez, Acting Assistant Principal (2nd chair), Friends of Janet F. Ruggeri Assistant Principal Viola Chair

Alejandro Duque, Acting Assistant Principal (3rd chair)

Elizabeth Breslin

Georgi Dimitrov

Nathan Hackett

Michael Lieberman**

Erin H. Pipal

CELLOS

Susan Babini, Principal, Dorothea C. Mayer Principal Cello Chair

Shinae Ra, Assistant Principal (2nd chair)

Scott Tisdel, Associate Principal Emeritus

Madeleine Kabat

Peter Szczepanek

Peter J. Thomas

Adrien Zitoun

BASSES

Principal, Donald B. Abert Principal Bass Chair

Andrew Raciti, Acting Principal

Nash Tomey, Acting Assistant Principal (2nd chair)

Brittany Conrad Broner McCoy

Paris Myers

HARP

Julia Coronelli, Principal, Walter Schroeder Principal Harp Chair

FLUTES

Sonora Slocum, Principal, Margaret and Roy Butter Principal Flute Chair

Heather Zinninger, Assistant Principal

Jennifer Bouton Schaub

PICCOLO

Jennifer Bouton Schaub

OBOES

Katherine Young Steele, Principal, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra League Principal Oboe Chair

Kevin Pearl, Assistant Principal

Margaret Butler

ENGLISH HORN

Margaret Butler, Philip and Beatrice Blank English Horn Chair in memoriam to John Martin

CLARINETS

Todd Levy, Principal, Franklyn Esenberg Principal Clarinet Chair

Jay Shankar, Assistant Principal, Donald and Ruth P. Taylor Assistant Principal Clarinet Chair

Besnik Abrashi

E-FLAT CLARINET

Jay Shankar

BASS CLARINET

Besnik Abrashi

BASSOONS

Catherine Van Handel, Principal, Muriel C. and John D. Silbar Family

Principal Bassoon Chair

Rudi Heinrich, Assistant Principal

Matthew Melillo

CONTRABASSOON

Matthew Melillo

HORNS

Matthew Annin, Principal, Krause Family Principal

French Horn Chair

Krystof Pipal, Associate Principal

Dietrich Hemann, Andy Nunemaker French Horn Chair

Darcy Hamlin

Dawson Hartman

TRUMPETS

Matthew Ernst, Principal, Walter L. Robb Family Principal Trumpet Chair

David Cohen, Associate Principal, Martin J. Krebs Associate Principal Trumpet Chair

Tim McCarthy, Fred Fuller Trumpet Chair

TROMBONES

Megumi Kanda, Principal, Marjorie Tiefenthaler Principal Trombone Chair

Kirk Ferguson, Assistant Principal

BASS TROMBONE

John Thevenet, Richard M. Kimball Bass Trombone Chair

TUBA

Robyn Black, Principal, John and Judith Simonitsch Tuba Chair

TIMPANI

Dean Borghesani, Principal

Chris Riggs, Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Robert Klieger, Principal

Chris Riggs

PIANO

Melitta S. Pick Endowed Piano Chair

PERSONNEL

Antonio Padilla Denis, Director of Orchestra Personnel

Paris Myers, Hiring Coordinator

LIBRARIANS

Paul Beck, Principal Librarian, James E. Van Ess Principal Librarian Chair

Matthew Geise, Assistant Librarian & Media Archivist

PRODUCTION

Tristan Wallace, Production Manager/Live Audio

Lisa Sottile, Production Stage Manager

* Leave of Absence 2025.26 Season

** Acting member of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra 2025.26 Season