R2!

R2! The River Rat

A student literary journal produced in the Writing and Humanities department at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design

fall 2025, vol. 2, no. 1

Masthead

Editor-in-Chief: CJ Scruton

Managing Editor: Ashley Luchinski

Guest Editor: B. Pladek

Readers:

Emily Blaser

Alexia Brunson

Cheryl Coan

Devlin Grimm

Anna Hillary

David Lawson

Lauren Simmons

Donna Tanzer

Andy Turner

Isabelle Von Sturm Day

Layout and design: CJ Scruton

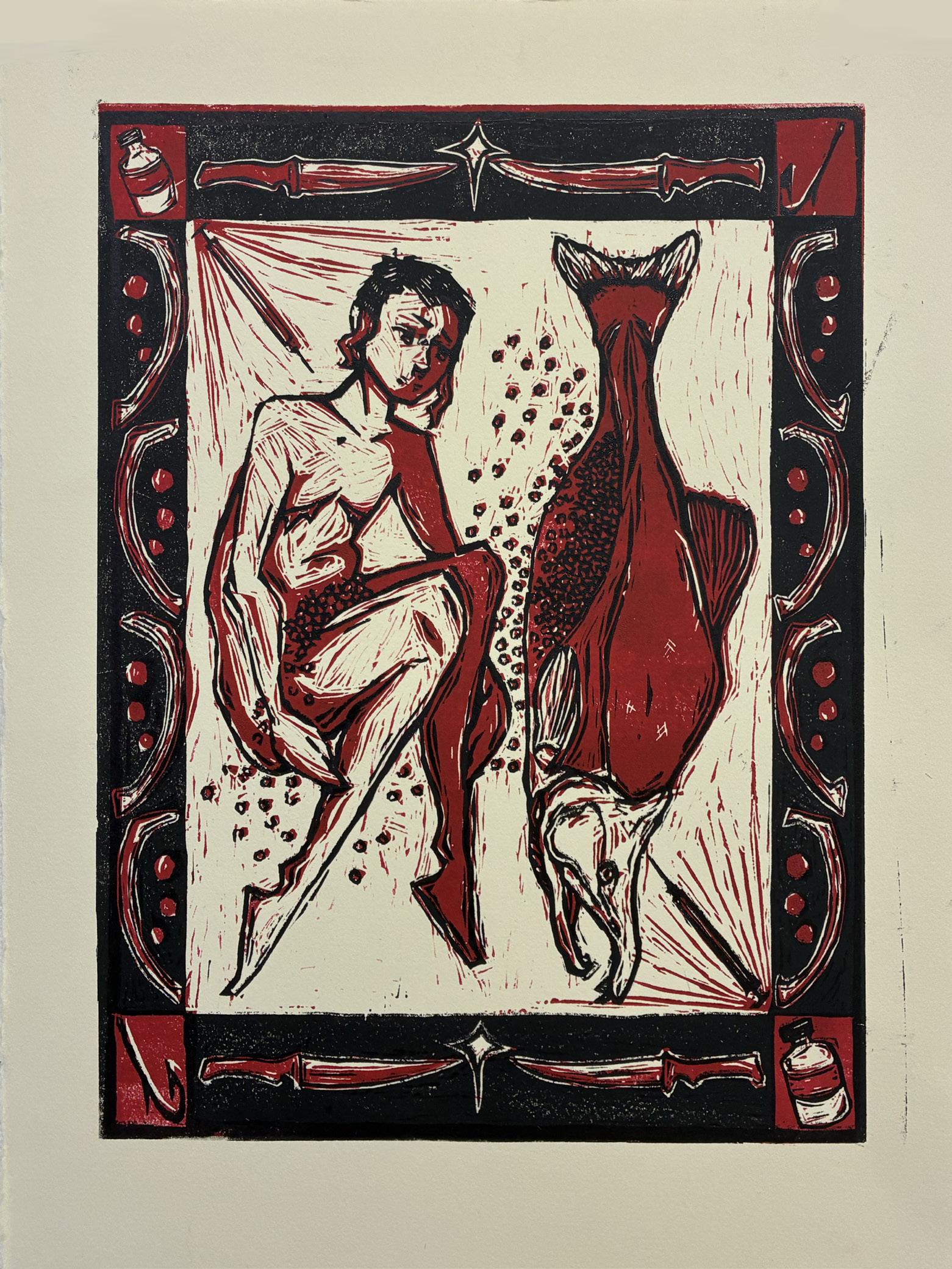

Cover art:

Daniel Perez, “See Me”

Nonfiction

Lexington Berens-VanHeest

Jamie Messerman

Erin Woods

Sylvia Munoz

Rowan R

K.L.

Haircut as Revolution .

Life-Writing Journal #2: Daydreaming .

(Over)Stated Surveillance

I’m Reading Captain America Fanfiction Instead of Doing My Homework

Visual Art

Cal Davis

Shonchalai

Madalin Francis Ramos

Jayne Henningsgaard

Greta Berens

Matthew Davis III

Max McClure

Benjamin Smith

Fiction

Oakley Lopez

Miette Smith-Golwitzer

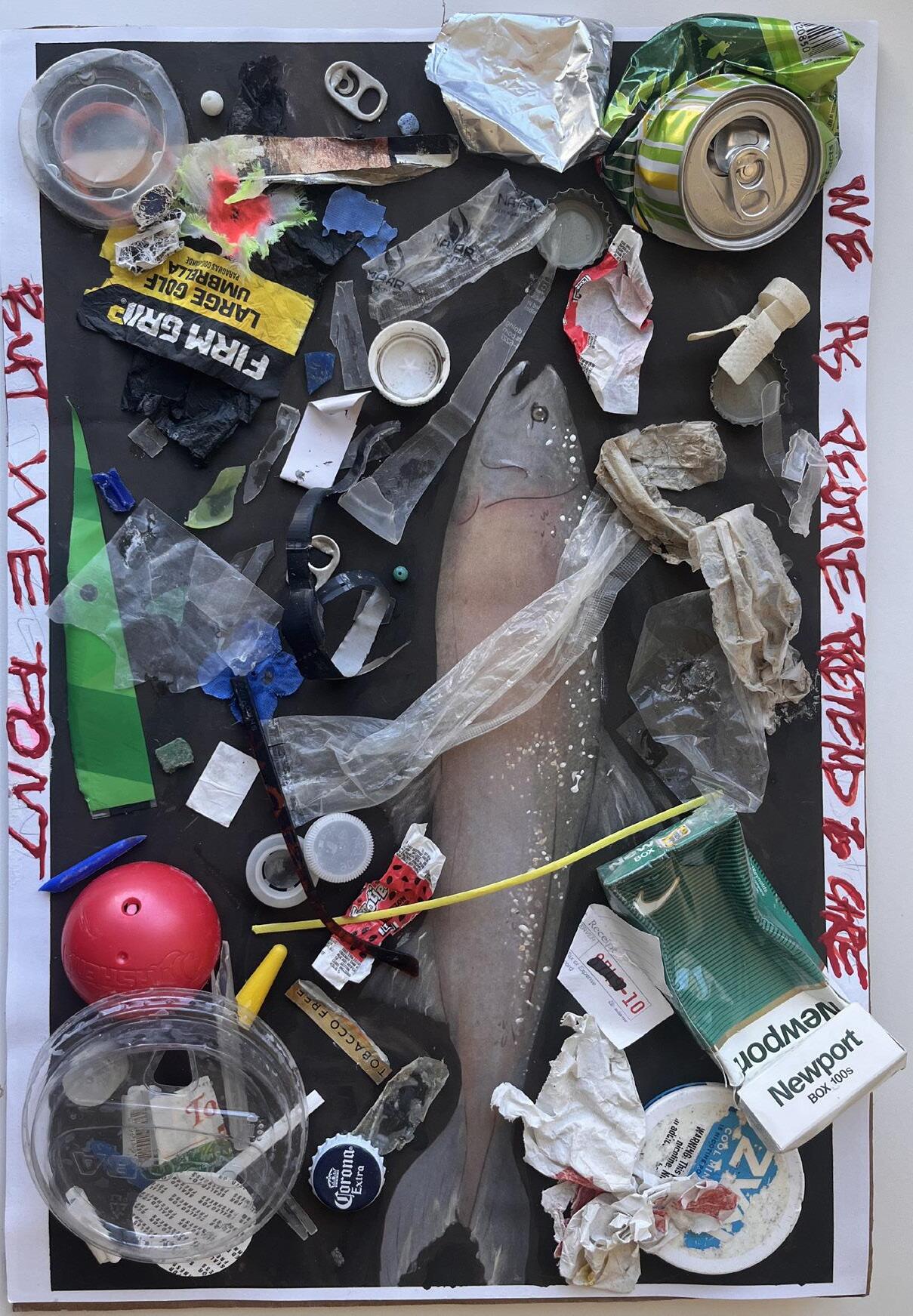

Life Cycle of Salmon .

Young Flicker

First Feeling of Art

The Intern Shaved My Vampire Teeth and I’m Still Mad about It

Rimbaud’s Life Experiences .

Forgive Me, for I Have Lost My Throne

Our Reality

Untitled (2025)

The Enchanted Marsh Has Frogs

Dream of a Projector’s Whir

Poetry

Simon Brink

Leonardo Rivas

Mack Horky

Audra K

Uni

Emily York

Tori Vaughn

Jaidyn Brink

Sailor’s Delight

A Pearl Necklace

Dragged from the Freezer

Community, at a Glance

For My Parents

The Art of Noticing

My First Love

A-Frame

Summoning Space

SAILOR’S DELIGHT

Simon Brink

abandoned by nurses, the sound of an oxygen tank in the living room makes me realize how fragile you are. I often sat by that brown recliner in the living room, holding your big hands in my small ones. I would curl my hand around your finger because your hand was so big I couldn’t fit mine around it. The television seemed dimmer, and the living room had turned into a temporary hospice. I would often think about the unusual quietness in the house, gone was the French cursing in the kitchen. often I regretted not asking you to teach me.

Sometimes I hope you wash up on the shoreline from Dog Key Pass. When we released you there, The sky was red and a butterfly flew past me.

LIFE CYCLE OF SALMON

Cal Davis

THE ENCHANTED MARSH HAS FROGS

Oakley Lopez

Far away, in an ever-distant land, most alive when the moon kisses her light upon the dew drops that spill into wide, reflective pools, is an enchanted marsh.

Pixies posed like dolls dance around the reeds, and satyrs with their pipes, play music that reaches the edges where the marsh melts into muck, swamp, and tall trees. The changelings waltz to and fro, mingling and taking pieces and stories from others to lock into their ever-evolving hearts. Will-o’-the wisps flutter in spirals throughout the land, scattering a shimmering kaleidoscope over the drab greens and browns, guiding the lost fae to the marsh, where they joined in the dance. A menagerie, a masquerade with no masks, a dance, and a prance that’s carried by the whispers on the wind.

In the enchanted marsh, there are also frogs.

Slimy from their ponds and grasses, with long, gooey limbs and hands that slap and grab and leap from lily to lotus. Some are in every shade of olive and oak, while others are deeply and brightly hued — a warning sign to the others. Some are less slick and more warted, covered in bumps and ridges akin to the logs they’d perch themselves onto. They have long, sticky tongues that shoot out quickly and frequently; you could almost miss them if you blinked.

There are many frogs in the marsh. Some pose with the pixies, play with the Satyrs and their pipes, and give their stories to the changelings. But the frogs do not often get along with each other, it would seem. They flirt and flounce enough, but you can often find them cautioning each other away from their

part of the pond. The bright ones have their warnings and their poison, and all of them have their resentment. At best — a hesitant best — you’ll find them alone, with nary another frog by their side. At worst — a horrible worst — they’re cannibalizing each other. The frog fancies himself a romantic creature, but he does not act with romance. No, instead, he shoots his tongue out and catches the fly before the frog lurking near can stab the sky and steal it from him. Many of them will do this. Truly, they prefer the company of the other enchanted creatures of the marshland.

Yes, the other enchanted creatures of the marsh. Because they can feel free to have fun with the frogs despite the fear that comes with them at times — a pixie could be a fly in the eyes of a frog who squints with suspicion. Yes, they can be friends, for the frogs, too, are enchanted. The frogs hate each other. Despise each other. They’re reminders that they’re still waiting for that true love’s kiss, the one that will bring forth a blossoming transformation into the prince they know they’re meant to be for another.

From frog to prince.

The other creatures feel a deep pity for the frogs. For they do not realize that the kiss they wait for with bated breath could come from another frog all along.

YOUNG FLICKER Shonchalai

Lexington Berens-VanHeest

Honorable Mention for the River Rat Prize in Prose

You are on a boat, drifting through a lake thick with lotus blossoms and enveloping leaves that blur into a verdant tree line and soft sky.

I. The sky is a ragged satin blue, clouds threaded near seamlessly through its hazy hue.

II. There are no paddles. You are not sure how you found yourself aimlessly floating along, or how you will find solid ground again —

A. Stay within the frame.

III. You are not alone in the boat.

A. (An obvious fact, but one B. that you overlooked, perhaps, too distracted C. by the serene landscape surrounding you.)

There are two women across from you.

I. The one on the left —

A. Her dress is a gentle brown, with belled sleeves and a modest cut.

B. Her hair, wispy brown curls, are delegated to the shelter of a straw bonnet, adorned with modest flowers, its most eye-catching feature the voluminous white bow fastening in place under her chin, spilling down her chest.

1. You wonder if its bulk puts tension on her throat.

C. Her lap is full of lotus blossoms, which her downward gaze regards. Her eyebrows are

slightly furrowed, pink lips neutral. She looks…

1. Thoughtful.

2. Peaceful.

3. Worried.

4. Sad.

5. Wistful.

6. You’re not sure.

a. Do you want to know?

b. (You never will.)

D. Her right arm grips the edge of the boat

1. Firmly

2. Gently

3. Steadyingly

E. — while her left holds up a large parasol, veined with metal and glowing from behind.

1. It’s not dissimilar from an inverted version of the lotus leaves you part, blanketing her in soft shadows.

2. There is a thick golden band on her ring finger. Maybe that’s what she’s looking at, rather than the flowers.

F. Her name is Charlotte Ada Taylor, but she likes to be called Lottie.

1. She is the cousin of the woman to her right, on the boat with you.

2. (I am sorry, dearest reader, that this is all I can say concretely — beyond that, I am grasping at straws and potential matches.)

3. She is modest, and traditional, and a proper lady.

4. What else do you need to know?

a. She is not the one you are here to look at, after all,

b. She is not the one that matters to you.

i. (I keep coming back to her anyways.)

II. The one on the right —

A. That is your wife.

1. (If you are, indeed, the painter.)

B. She is dressed in a fashionable white gown, with scalloped lace at the bottom, a pair of thin stripes weaving a shimmering ripple through the folds of her skirt, long tight clinging sleeves ever so slightly sheer, revealing the warmth of pink beneath it.

C. Her hat is a boating hat, flat brimmed, a cake box on a dais, clad in woven straw and a similar clinging white ribbon, though it entwines the band of the hat, growing pink in its crevices and trailing behind her as a little pendant as you drift.

D. One hand in her lap, the other reaching over the edge to pluck a lotus flower from the grasp of the lake’s surface.

1. At your wedding, she had a bouquet of water lilies.

a. Your wedding. Can you remember that? Why can’t you remember anything beyond this moment?

b. Stop feeling for the edges of the frame and submerge yourself in its carved paint.

2. I wonder if the act of taking says something about her. That you are

surrounded by beautiful flowers in all directions (though you can only look in one) and yet she won’t just appreciate the moment, that she wants to take some of it, rip it from life with her greedy hands.

a. Or were they gentle hands?

b. To be human is to destroy. Perhaps she deserves no judgement for this.

E. She is beautiful.

1. I know.

a. I know.

i. I know.

III. Who are you, the viewer?

A. You are in the boat with them, certainly, B. but are you the hand that layered each brushstroke,

C. whose eyes witnessed this scene?

1. (you are.)

2. (you are not.)

a. (maybe you are something else entirely.)

You are on a boat, drifting through a lake thick with lotus blossoms and enveloping leaves that blur into a verdant tree line and soft sky.

I. You are in Lotus Lillies, a painting by Charles Courtney Curran.

II. Can you feel the paint beneath your skin? Feel it in your lungs, your eyes, seeping from you?

III. You are not alone on the lake, either. Another boat, more implication than definition, goes horizontal to you in the distance. How long has it been there?

A. Only for a moment.

B. Eternally.

IV. You’re in Old Woman Creek, an estuary off of Lake Erie, where your wife’s family owns several summer cottages.

A. (An estuary is where fresh water drains out to sea, a strange wetland found where salt and fresh water mix.)

V. Take in the beautiful landscape.

A. Follow the shapes of dark umbrellaed silhouettes cutting across the blue mirror water.

B. Take in the unfolding lamp-like blossoms, curving into an unnamed fractal.

C. Look at the two women in front of you.

1. They are as much a part of the landscape as your surroundings.

2. Are they people, or just objects? Do they breathe, or are they still under your gaze?

3. They do not look at you, but they know you are watching.

a. They always know. They can feel it crawling on their skin.

You are on a boat, drifting —

I. No.

You are looking at a painting, being pulled into it by my hands. You grip the frame as tightly as Lottie grips the boat, submerged into this world of paint and canvas.

I. I am pulling you by the hair, trying to get you deep enough that you can see something, something

important, something that called to me, but I cannot do it.

II. I am not sure what I am trying to show you.

III. You are running out of air.

I let go. You surface once again, coughing up

I. Scraps of depicted lace and A. thick crumpled wads of billowing leaves and 1. feathery petals that burst from your mouth like confetti.

You can feel

I. Linseed on your tongue,

II. canvas scrapped lungs heaving,

III. the creamy remnant of oil paint in between your teeth.

Breathe deeply. Take a moment, then try again.

Where are you?

I. You are on a boat, drifting…

II.

III.

IV.

V.

FIRST FEELING OF ART

Madalin Francis Ramos

A PEARL NECKLACE

Leonardo Rivas

the world is so full of soft things that 1 hold near my heart until they become pearls

1 string them on a thread tying knots with one eye closed secured into a necklace so I can never lose them even after the memories fade, 1 can still feel the warmth through the lacquer

TIDEWRACK

Jamie Messerman

It happens in the attic of the cottage by the sea. It is early morning when a dead body washes up on shore, eyes frozen open. He’s walking along the beach and finds the carcass; a look of disgust forms on his face at the sight of the mangled figure. Still, he tenderly untangles their limbs from the rocks where they were caught. Their eyes are open, gazing at his face above their body, holding the limp vessel. They cannot move, or speak, or hear, because they are dead. Arms hang motionless at their sides, swaying only through his movement as he hoists the figure into his arms. For a moment, the two make eye contact. A bitter feeling washes over him from looking at the body. The corpse is a reminder of what he does not have.

He carries it home, through the door, up the stairs, and walks down the long hall to its end. His demeanor shifts and the body is dropped carelessly to the floor. He doesn’t look back at where he dropped the body or check for damage, and pulls the attic ladder down from the ceiling. Dead weight thuds heavily on wood panels, their skull hitting a loose nail, a cool, wet sensation following the throbbing they feel at the base of their head. Hands slide gently under their arms and wrap around their torso, hoisting them up the rickety ladder. Blood smears on his shirt from the body’s head wound. When the body arrives in the attic, it is tucked neatly into the corner formed between his bedframe and wall. Cool blood trickles down their neck, slowly creeping between their shoulderblades. Over each disc of their spine. He approaches with a wet cloth, wiping away the blood before it can make it to the body’s tailbone. He is gentle. The cloth is rough, so he must be careful to not use excess pressure, not wanting to irritate the skin. This is his apology for dropping them so

carelessly. He thought he wanted to hurt the corpse, but that isn’t it. Dropping them so carelessly only made him feel worse. Their head lulls forward over his shoulder when he leans their body over, searching for the origin of the blood. Their chin fits nicely over his shoulder. It is snug in the crevice of his neck. The cadaver’s collarbone juts out against his own clavicle. His hands are light, moving hair aside to dab carefully at the bloody dent in their skull. Their eyes are open and stare down his back.

Once he is sure the wound has stopped bleeding, they’re dragged to the center of the room, laying them under the skylight above. The centerpiece of the attic. Light shines through the window to create a halo around his silhouetted figure. He leans in close, hands glide over their side, observing the body with his hands just as much as with his eyes. In some places they feel fingers dig into their flesh with a sense of desperation. In others they tread lightly, taking time to admire the cadaver’s form. His eyes try to hide the desperation, the frustration, the sadness that he feels when looking at the corpse. The carrion just lays there, unmoving, unable to understand why he has taken them into his home, why they are laying here on his floor, why he touches them so gently. Fingertips stop above the navel, studying this place before rising and heading across the room to a dresser.

His figure looms over them when he returns, a scalpel in his left hand catching the light from above. When he leans in close over the cadaver’s torso, they can feel his breath on their cool skin. Then, the stinging comes. It begins at their navel, tracing up the corpse’s torso, ending just below the sternum. The air feels cool when the scalpel leaves the skin it just carved open. A horizontal and vertical incision create doors, and he opens them to reveal their viscera. The cadaver stares up at him as he lifts his own shirt to reveal a torso with identical incisions. The sutures that hold him closed are messy and rushed; the skin is taught from the stitches being pulled

too tightly. Without cleaning the blade, he lifts the scalpel to his own body. One by one, they can hear the gentle pop as each stitch releases. Once the sutures have been removed, he looks back down at the carcass and smiles. He opens up his torso and the body stares into the empty space inside. The organs that once filled the space are small and shriveled.

Gloved hands enter the cadaver’s center and he maneuvers their innards with precision. Their soft parts are lifted and sliced out. One by one, they feel their cavity empty. The warmth from his hands briefly fills the void he creates. He places each intestine within himself and for a moment, the two are connected by the string of organs. Once the body is emptied of everything that makes them whole, he hastily grabs supplies to redo his sutures. He looks down at his work, but he doesn’t look happy. His expression is empty, pale, unhappy. He glares down at the corpse, and they stare back up at him, unsure what else they have left they could possibly offer to him. He has taken everything. But it is now that the corpse moves, the only movement their lifeless form will allow. They lift a cold hand toward him, reaching out. He looks away, rising and returning the supplies to their place across the room. The cadaver turns their head to watch as he cleans the scalpel. His movement is almost mechanical. He returns to the body, his expression unreadable, similar to when they first met on the beach. They can no longer see any of the turmoil that stirred on his face just a few minutes ago. He grabs the body, hoisting it up into his arms, and brings it back down the ladder, the hall, down the stairs, and out the door. He walks along the beach, and returns them to the rocks. He discards them, and they watch him walk away. He never looks back.

DRAGGED FROM THE FREEZER

Mack Horky

Honorable Mention for the River Rat Prize in Poetry

My flank hangs in your closet swaying in the breeze, the draft coming in through the window. Slung over your coat hanger I’m staining the carpet and your room is pungent.

Did you want me to apologize? Unhook myself and get down onto my knees to beg?

The maggots are shifting through your carpet in the sun

There are flies in your room swarming my stretched and graying form. The sunlight is pouring in making the room boil and stink, and it almost makes me regret it.

THE INTERN SHAVED MY VAMPIRE

TEETH AND I’M STILL MAD ABOUT IT

Jayne Henningsgaard

HAIRCUT AS REVOLUTION

Erin Woods

For the longest time I believed that I could only wear my hair long. As a child short hair suited me fine, it fit the childhood ideals of tomboyishness well enough, though was feminine enough to not be too transgressive for my family. The worst was what my sister dubbed “coconut head,” after the Nickelodeon character. It was the overly stylized salon equivalent to the bowl cut, it was horrible. At the time I loved it, it meant the physical pain of having your hair tied up wasn’t an option anymore. I didn’t have to feel the soreness that came with removing pigtails after a long day, and massaging the hair back into my head. I suppose a bad haircut is always the sign of some minor revolution, some internalized recognition of your own free will. After the coconut head I grew my hair long, wore it on my shoulders and kept my bangs as shields to protect myself (well, more of a hindrance than a protection, but such is the reality of having bangs). Middle school is situated approximately in the ninth circle of hell for insecure fat people (worse so, for insecure fat lesbians). This is the time where you’re old enough to get a fuller, crueler glimpse into fatphobia. Where you get a better understanding that your peers view you as an other, an it, an archetype that exists in one of two forms. Pitied or ridiculed. Middle school had its claws in me. Middle school convinced me I was too fat to have short hair. I kept my hair to frame my face, shaving down the roundness of my cheeks and creating a barrier between me and the world’s ability to perceive me. I didn’t like longer hair, I didn’t like how often it would tangle or get in my face, nor how long it took to properly maintain. There were many times where I had wanted desperately to cut it shorter, but my own insecurities kept it growing.

It took about until my freshman year of high school to finally allow myself to cut my hair. It went from about shoulder-length, equally split between resting on my shoulders to a longer bob. This was the first step for me, while it wasn’t as short as the rest of my haircuts ended up being, the shorter cut represented more to me. It was the start of allowing myself to carve my own identity, to allow myself a form of expression I previously thought was unacceptable. I think that is the secret of a haircut, though society acts as though the way to obtain confidence is to obtain thinness, I find a good haircut gives me the same sense of satisfaction. For the next four years of high school I kept getting my hair cut shorter, and shorter. Chasing the euphoria of that first realization that not only did I feel happier with shortened hair, but that I could look good having it as well. Haircuts act almost as the first step to self acceptance. Hair is easily regrown, and thus is free to be cut and transformed into any form or color, can be styled with gel or grease or worn as is. The hair is the first thing to be altered when going through metamorphosis, and it is something that (for the most part) is accessible for any body. Eventually the urge to shorten my hair led to getting it fully buzzed off before starting college, the last stage of my transformation. It was then that I had decided what lengths I liked and didn’t, while the photos of the buzz cut look quite humorous to me now, someone who has settled into a look (though admittedly it’s shaggier than I’d prefer), I would likely still feel that itch to go shorter and shorter had I not taken the leap. The haircut is at once the ultimate form of dysphoria and euphoria wrapped into one, and just as it does for gender or sexuality, it takes experimenting and identifying what makes you happiest that leads to that final bliss.

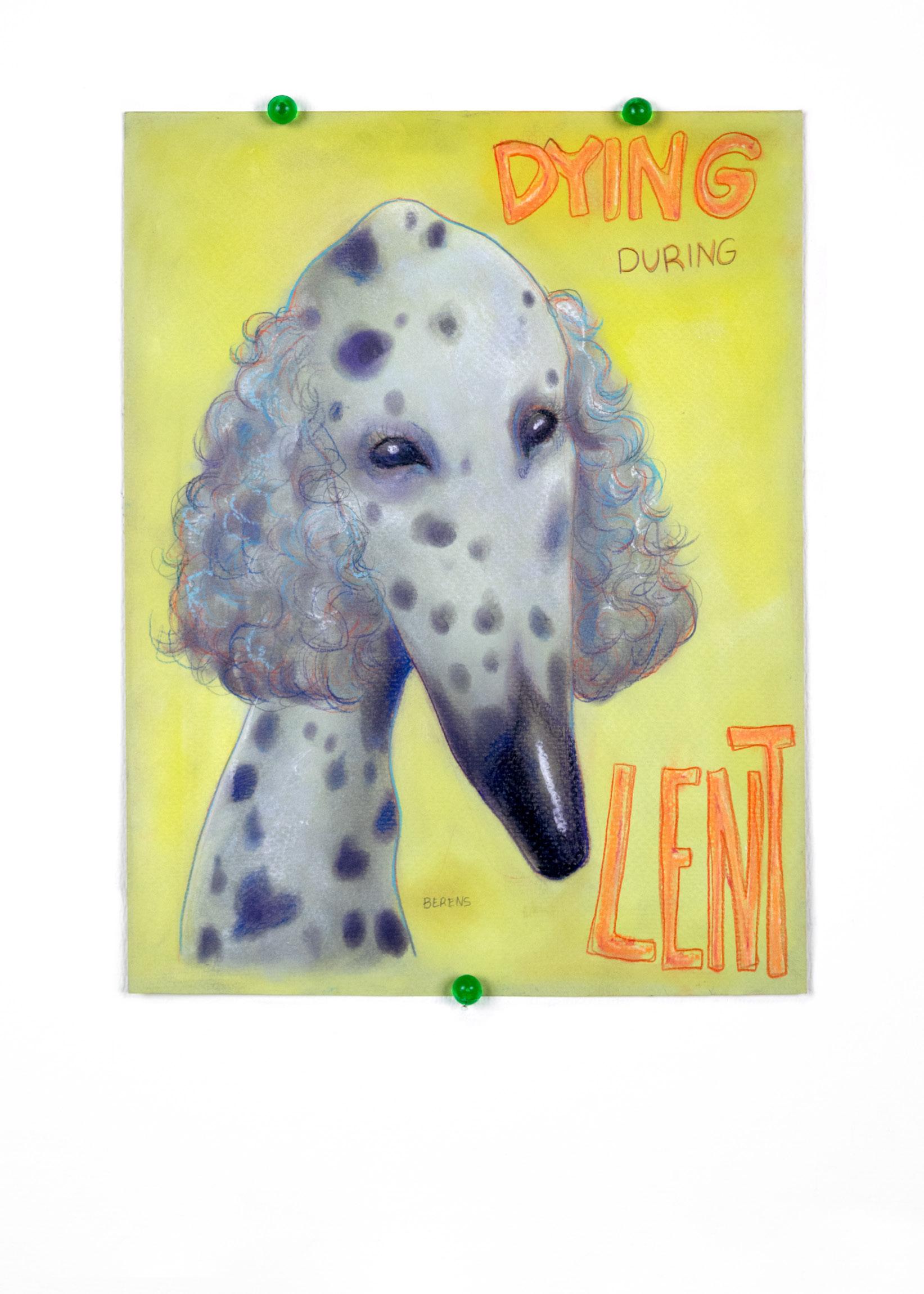

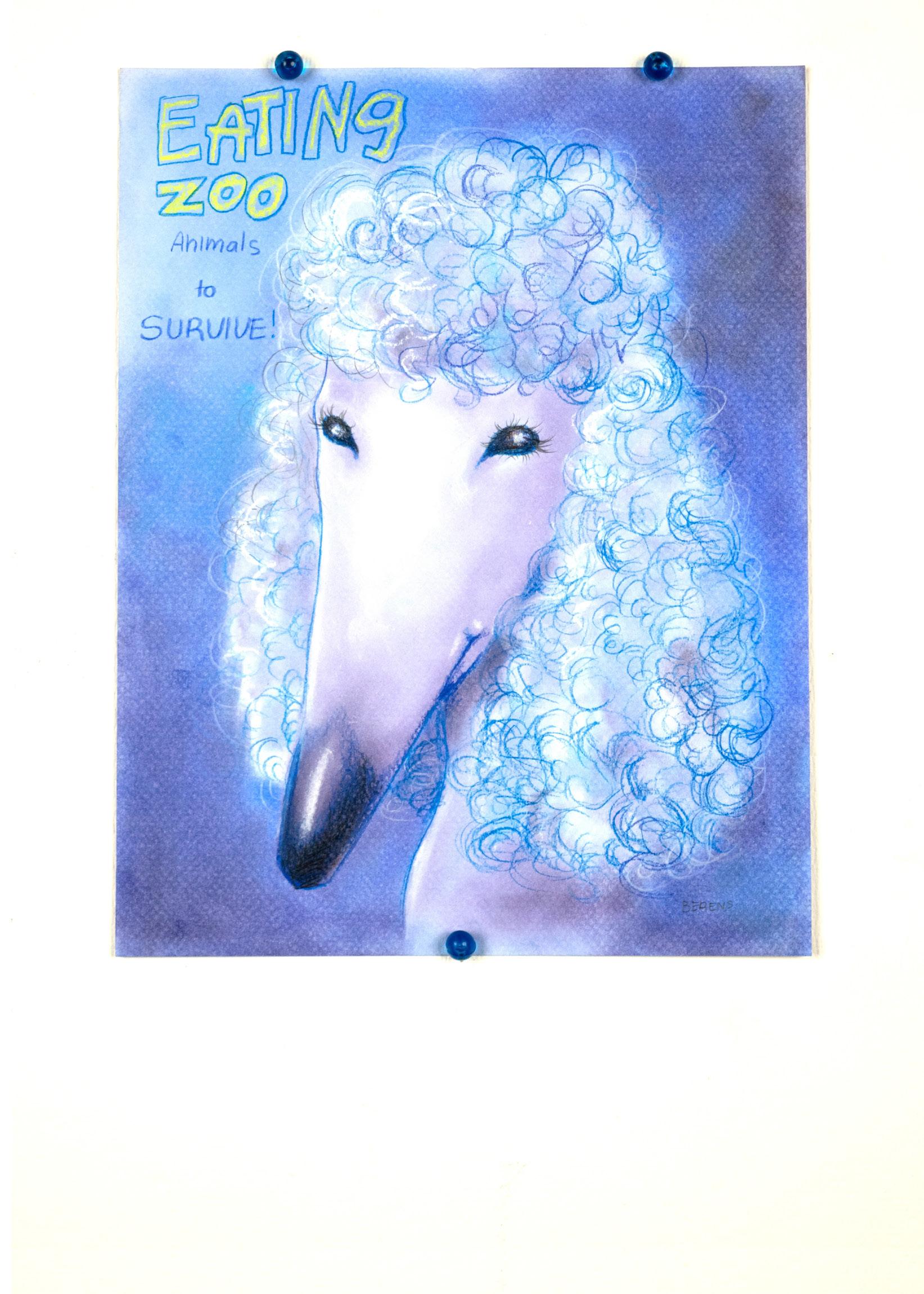

RIMBAUD’S LIFE EXPERIENCES

Greta Berens

COMMUNITY, AT A GLANCE

Audra K

I grew up in a small home in Waukesha, with gravel alleys sprinkled in with broken glass and beer bottles strewn about. Running barefoot down the drive with a friend and bragging about the built up bleeding callouses on my feet. My parents packed up and followed the smell of swamps to Brookfield. In a big house with more than enough room, and no one to fill it. But the air wasn’t that sweet, my family started dying, huffing up the gas. The taste of stomach cramping crab apples sticks to my tongue from my grafton grandparents. The summer sheer curtains stained with sunlight live as a permanent view in my windowed mind. And for a long time, my favorite place was a graveyard. I passed the time visiting my 10 year old cousin, just a few miles bike ride away, and waited to join her. I ended up growing tall with the grass instead of being set under it.

FOR MY PARENTS

Uni Land isn’t the only place to search.

Space, vastly open and far,

I navigate passion of belonging:

Twirl and twirl of dancing.

You speak as if independence is pointless

But a mask of self-reliance. Unsafe

Souls. Untrustworthy strangers.

Can I not desire freedom?

You’d stand by to watch my mistake

To see the flaws, I don’t often do

When I converse with the sea folk.

Then you say it’s the “American Dream”

As you pay tightly each paycheck.

Sylvia Munoz

#2: DAYDREAMING

Winner of the River Rat Prize in Prose

You’re scared. There’s one more class to go until school gets out and you don’t know if you want class to go on forever or end right now. Your sister is in the hospital again. You don’t know who will be there when you get home.

You try to talk quietly to your friends but they’re all seated too far away. Besides, you don’t tell them about this stuff. They try to get it but they don’t understand. The only way they understand death is maybe a grandma whose face is faded now. How can they understand what it feels like to think of death as someone in the room with you?

You try to pay attention in class but there’s not much point. The teacher talks too slowly explaining to other people for you to be able to keep track of what she’s talking about. You’ll figure it out later when you’re doing your homework. Or you can try to get it over with now.

You daydream. Letting your attention slip away, you pass the time the same way you always do when there’s too much to think about to let yourself think. You think about your new favorite fandom (as all the cool kids on the internet call it).

There’s a lot of people on the internet who write about all the characters living with the reader in a big house, so loud and full there’s barely room to think, where problems are solvable and you, the reader, is always the center of attention. You don’t know why it hurts in your chest how bad you want it, but you do. The droning on of your teacher is a bit too distracting to make this daydream last, though, so you have to switch to more concrete thoughts.

You do your homework. It isn’t that hard, and it means you’ll have time at home to draw or read fanfiction on your kindle. Or, more likely, you won’t have to worry about it if you end up going to the hospital after school so your parents can do the shift change. It’s impossible to get any homework done there. You always forget something, your pencil sharpener or your eraser or your red pen. And they don’t keep stuff like that in the kid’s waiting area. You finish your homework without incident, and there’s nothing else to keep your attention.

Without direction, your thoughts slip to the worst possible outcome. They always do, no matter what you try. Any moment now:

You try to focus on the good things. You had to make your own lunch today and you just stuffed your lunchbox with snacks. You know there’s some left over for the bus home That’s nice, isn’t it? Aren’t there nice things to think about? Are there?

Someone will come to the classroom door to get you. The principal, maybe, or the school counselor you’ve never actually seen, despite how you walk slow past her office door sometimes in the hope she’ll emerge and be able to read your suffering through your face, as part of her professional training or something. She’ll tell you to gather your stuff and follow her to her office.

They’ll call your name on the loudspeaker and ask you to come down to the principal’s office. Kids will ooh like you’re in trouble but it’ll be kind of halfhearted. You’re not a troublemaker. You’re not much of anything.

When you get to the door, she’ll tell you to bring one or two of your friends. You’ll beckon to the one person you want to come with you. You don’t really have other friends in this class. She’ll be confused, but pack up and come with you. She won’t be sick to her stomach or anything.

You’ll shove all your stuff in your bag without a single care for how they end up. All your work ends up crumpled at the bottom of your bag anyway.

You’ll pack your stuff up real slow, putting each paper in its folder nice and uncrumpled. You don’t want to get there.

You’ll nearly trip yourself hurrying down the hall without actually running. You need to know as fast as possible that it’s not really actually happening. It has to be something else.

You’ll walk slow down the hallway and try to peer in the office door through the marbled glass before they get a glance of you and let you in.

She’ll walk you there with a hand on your shoulder. It’s weird. You’re a little too old for adults to touch you casually anymore, what with perverts around and everything. You don’t really remember the last time you’ve been more than just brushed against by accident. You told your friends you didn’t like being touched because you couldn’t describe why when your best friend hugged you it made you feel miserable and sick to your stomach. When was the last time anyone tried to hug you? You really can’t remember.

When you see just your dad in there with your other sister, the healthier and babier one, you know. You know before you get in the door. In a moment you’ll have to go in and cry and plead and cling and grieve like you’re supposed to, like a living person does. You’ll have to be one of your parents’ remaining living daughters, even if it’s not what you feel like. Is it selfish to feel like you’re the one who died? It isn’t. You were right. You usually are. You won’t say anything to her the whole walk down the hall even when she asks what’s going on. You try to make a face like you don’t know. You imagine your jaw is wired shut so surely you won’t throw up.

You decide halfway through her packing that you don’t want her to come. You want the option to come to school tomorrow like nothing happened. You can already hear the whispers when she tells everyone, the sudden pity from people who didn’t even care to learn your name before.

She’ll hold her big corded phone, black and smooth and sweaty from someone else’s hand up to your ear and the voice on the phone will tell you what you already know.

Your aunt is there, or your grandfather. They haven’t rehearsed this speech before, so they hesitate after the first breath. It doesn’t matter, the saying it is more for them than you. You don’t need them to say anything. You already know. You know.

She’ll sit you down in a chair in her office to wait for someone to come get you, and the emptiness of the wait will eat away at her ability to pretend. Her face will mold itself after one of those sad women in movies, in a way that’ll make you wonder if she’s even real. The ticking clock will be the only thing that tells you anything. You know what it’s telling you.

The bell rings and snaps you out of it. You hurry to the bus to get a good seat near the front, where people don’t want to sit. You keep your headphones in full volume and your phone screen pointed up. You go home. No one is there. You’re scared. There’s nobody to tell.

DREAM OF A PROJECTOR’S WHIR

Miette Smith-Golwitzer

I remember where I was before, but not how I got here in this cabin, watching the projector whir to life again. Before, the snowstorm outside the car grew stronger by the second. We were barreling down a country road, scattered pine trees becoming blurs of greens as we passed them. Snow piled up on the road, caught beneath the tires causing a rhythm of thumps that got faster as we went further. Faster and faster, snow piling higher and higher, until the mounds of snow began to rise to the height of the car. It unevenly fell on the road, rising and then falling like waves. We didn’t slow down — instead we sped up, blasting through every hump in the road. When the tall piles of snow finally crested the top of the car, we’d be surrounded by darkness for a moment before emerging on the other side. Every pile got wider and closer together, bathing us in darkness for longer each time we hit more snow. I tried to look at my dad in the front seat from where I was in the back, but his face was out of view. I couldn’t form the words I wanted to say. Soon I couldn’t see anything, only flashes of dark and light as we crashed into and out of the snow. Again and again, I saw the flashes even when I closed my eyes. Until the darkness stayed and there was no light.

I opened my eyes to a warm light, high up in a wooden room. As I tried to get up, I realized I was on a bunk bed in a cabin. The bed was also made of wood, and had carvings of initials and names. The room looked worn, but well kept. I hopped down from the top, landing unbalanced on my heels with a thud. I caught myself before I fell, approached the ajar door and peeked into the room beyond. Rays of sun slightly illuminated a long hallway with cabinets and countertops to the side. I walked down the hallway towards another cracked door into a warmly lit room filled with chairs — all red except

one to the left of the aisle in the third row, which was blue. At the back of the room was a screen. I went and sat down, and the moment I did I heard a whirring sound. I looked up to see a projector on the ceiling, the light beginning to filter through the lens and illuminate the screen. I looked back towards it, but when I did the whirring got louder, and louder, and louder. I closed my eyes and put my hands over my ears, flashes of light appearing now that were bright enough to be seen through my lids. Light and dark back forth, repeating at a sickened fast pace until… the darkness stayed again.

I opened my eyes to a bright fluorescent light that was painful to look at. The bed I was on felt cold and hard. I jumped down, landing with a muted bang that slightly echoed. I reached for the closed door and twisted the handle. The hallway was just as bright as the bedroom, and had the smell of powerful disinfectant. Quickly walking, I reached the door to the projector room and found it also shut. I pushed it open to see the same colors of chairs, all red but one blue. Again I sat in the blue chair, and like last time the projector began to turn on. I tried to keep my eyes on the screen as the light appeared, but the flashing became overwhelming once again. On impulse my eyes squeezed shut as the light and dark entered their dance again. I forced them open, despite it hurting, because I knew I had to see what was on the screen in front of me. The flashing continued until I heard a snap, and the light stayed. Nothing could be made out yet, but I leaned forward in anticipation. I had to see what was shown. Just as an image came into view, I blinked.

When my eyes opened again I was on top of a bunk bed, in a room, but it looked different from the previous two. Here the walls were made of brick, and the door was already wide open. Like before I jumped down, headed to the projector room, and sat in the lone blue chair. And again the moment I thought I’d see what was on the screen I blinked a second too soon, waking up in a new but familiar room. Every

time the cabin and room were in a different state — clean, dirty, made from stone, or mud, or glass. Along with the inside, the outside changed too, ranging from rainy spring to bright summer to cloudy fall. No sense of time passing came to me with the cabin’s constant changing state. The outside didn’t follow logic, the sun never rising or setting in the correct sequence, and the inside looked too different every time for it to be the same space despite the layout being nearly identical.

I couldn’t remember my name, what I looked like, who I ever was. All I could recall was a car going through a snowy landscape. I finally paused, considered the space I found myself in when I woke up shivering and numb. The bed had fallen apart and to the floor, snow began to cover it. Part of the roof of the room had caved and let in the cold from the raging storm outside. I could barely move but managed to crawl through the doorway, the door barely hanging on its hinges to the side. The hallway was hardly warmer but better than the bedroom. No lights were on and the harsh winds whipped the sides of the cabin. Cobwebs covered every corner, dust heavy on the countertops. The cabin had never looked abandoned like this. A shudder, not from the cold, rushed through me from the bottom of my spine to the top of my shoulders. Slowly I stood up and tried to make my way to the projector room. The cold went through my skin like between the fibers of a shirt, seeping past muscle and into bone.

I stumbled and caught myself on the doorway. Looking in, it wasn’t really a room anymore. The door was broken on the floor, an entire wall nearly gone. Snow rushed in and piled wherever the wind could take it. Every chair was overturned, or broken, or blown away, except for one. I staggered to the blue chair, left of the aisle, in the third row, and collapsed into it. Instead of whirring the projector made a clicking sound, like a film being rolled. Heavy lidded eyes looked up to the screen. Bright light filled my vision, but I kept my eyes open. On the screen, I finally saw what had been showing this entire

time. Every memory I could recall, from when I gained the ability to member played in order. The memories were shown faster and faster until I couldn’t discern what was on the screen anymore. But then it slowed down. I saw myself, alone, in a room of red chairs and one blue. The view was from behind me, and like mirrors reflecting each other I saw myself looking at the screen going on for seemingly forever. I began to try to move to look behind me, but sharp pinpricks erupted across my skin — the numbness the cold provided couldn’t help me any longer. Despite the pain, I turned to look, to see what was observing me. I knew I had to see. I felt a fear crawl across my entire body.

I blinked automatically before I could understand what I had seen. The moment between my eyes closing and opening felt like eternity, as I wanted to scream, wondering why, in that moment, I closed my eyes. The darkness behind my eyelids couldn’t match what I caught a glimpse of behind me. When I finally opened my eyes again, the eternal blink over, I was in my bed, in my house. My eyes ached with a familiar feeling of a lack of sleep and too much time staring at a screen. I wondered why I felt so cold, even surrounded by what should be comforting.

(OVER)STATED SURVEILLANCE

Rowan R

I hate the camera on my street because I can see it. I know I am always being watched.

I am not naive enough to think that no one is looking, that I am ever alone. I know that cctv exists. I know the echo dot brought into my home on black friday can hear me complain about it.

I know that something could always be watching me — the data is being collected, and if someone wanted to find something, they could.

I’m not careful. I sign up for coupons via email. I recycle passwords. I use my real name online.

I’m not stupid. I know I am being watched — or, at least, I know I’m being recorded, that the window is open with no curtains, whether or not a passerby or voyeur is there to watch from below.

I don’t think I could shut the blinds if I tried. But that’s not what bothers me.

I hate the camera on my street because I can see it. It rears its ugly head at me. Its unblinking eye looks at me through the bushes, optic nerve trailing back to a brain and body I have no way of naming.

I hate the camera on my street because someone put it where I can see it.

I don’t know if it belongs to the house framed by the hedge it uses for cover, if it’s a home security measure which, pointed away from the three-story mansion at the end of the street, feels more like offence than defence. It could also be CCTV. It could belong to the city or state or whatever else.

But it sits in its stupid little hideout either way, mocking me just the same.

It pretends it is hiding, but it knows I can see it, it knows that I am not fooled. It is a thing that pretends to pretend to hide.

It wants to feel accidentally seen.

I hate the camera on my street because the fact that I can see it means that it is working.

I see it, so I feel watched. I act watched.

It is for the same reason that people put up fake security cameras. They are not meant to be discreet.

I know I am always watchable — but the camera pretending to hide reminds me anyways. It says, you are under surveillance, and don’t you dare forget that. Don’t distract yourself. See me seeing you, and look down at yourself, see what I see. You can see my eye, the part of me that does the seeing. But you cannot see the one who watches you, or why, or if they are even there.

I hate the camera on my street because I know it is there. I can feel it always. This is what it wants, and I am powerless to refuse it that knowledge.

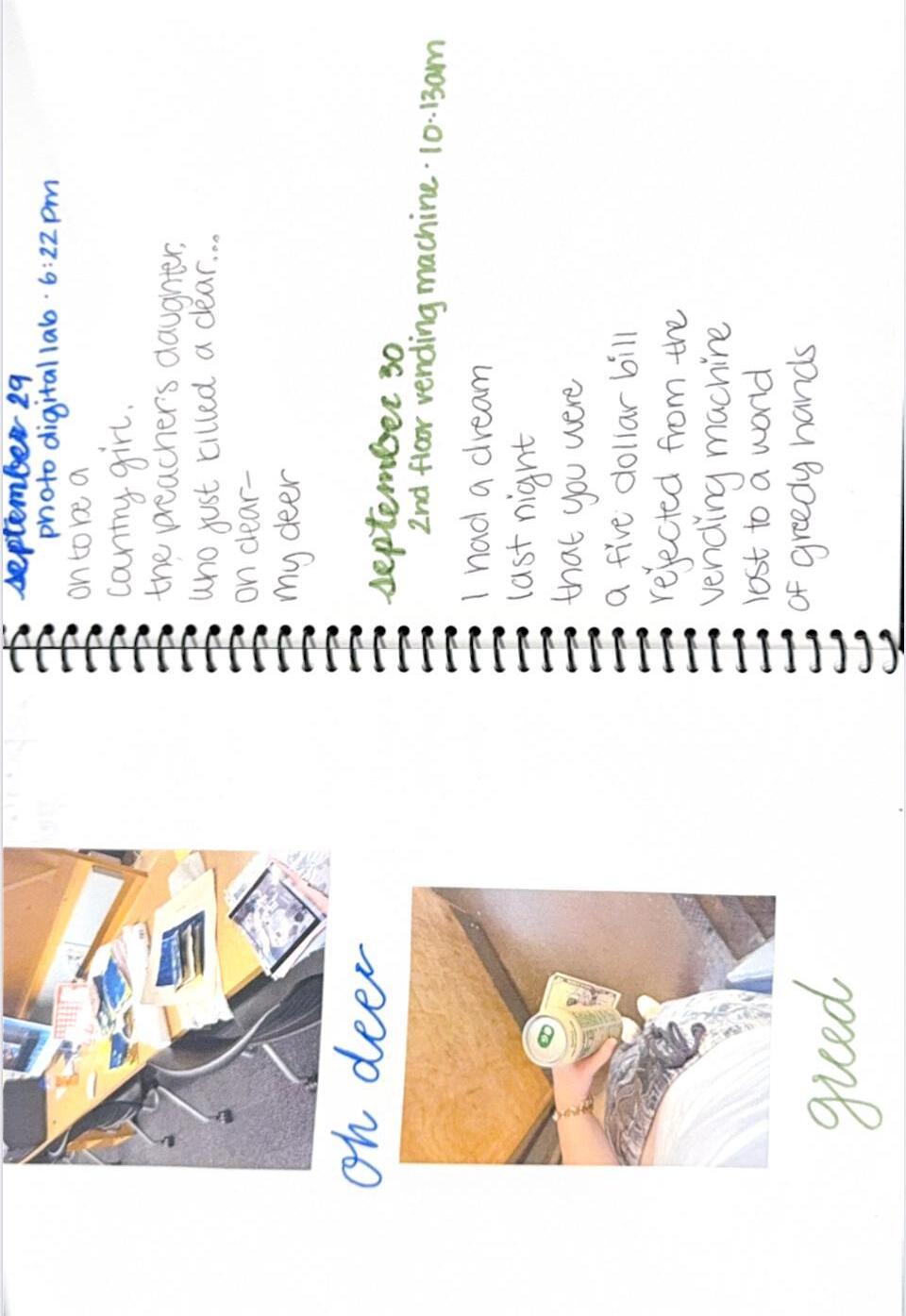

THE ART OF NOTICING

Emily York

The Art of Noticing was a month-long documentary project focused on impulsively taking photos and writing poems about other people, rather than myself. Some people are strangers who are unaware of my poem, while others are close friends. How closely can we observe the world around us, and how much can we notice about strangers?

Images from the project are featured on the following pages.

MY FIRST LOVE

Tori Vaughn

If you haven’t felt it yet, I’d call you lucky. That feeling leaves nothing but dread for the unlucky. Nothing but dread for the unlucky. My first love left memories that are utterly stuck with me. Memories that are utterly stuck with me are, unfortunately, blissful memories. He’s not so easily forgotten, not like the others. Not forgotten like the others, he was something special. The fling that came after didn’t feel as good as you, I gave someone else a try just to replace you.

But I never felt as good as I did underneath you. Underneath you, where everything was bliss, My first time was supposed to be exciting. Firsts are supposed to be clumsy and exciting. You played your part so well. So now what am I to do? I’m all alone, with my thoughts of you.

FORGIVE ME, FOR I HAVE LOST MY THRONE

Matthew Davis III

A-FRAME

the River Rat Prize in Poetry

of

Brink Winner

Jaidyn

I hardly remember laying down on the upper floor of that stark white a-frame. I was in so much pain I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t keep my eyes open; sliding in and out of consciousness. On the edge of some unnamable void. I should have heard you come up the stairs because I could hear you say my name. You crouched over the edge of our bed, running your fingers through my hair. My chest cinched close, throat got thick. I never want you to leave my side.

I woke in the morning and sat in the hot water so I could watch you watch the waves.

To roam the slick rock and point at the looms, at the small flowers on the bank. Add them to your collection. You collect the world in your mind and translate it in the palm of your hands.

Fingertips dancing on some new creation.

SUMMONING SPACE

Jaidyn Brink

It feels like my collar bones are reaching back, grabbing a hold of my spine to pull it forward. Summon it to this space that is caving in on itself.

I’ve been on the verge of panic for days now.

The body communicates strangely

Max

McClure

UNTITLED (2025)

Benjamin Smith

I’M

READING CAPTAIN AMERICA

FANFICTION INSTEAD OF DOING MY HOMEWORK

K.L.

And I’m thinking about my uncle who is not really my uncle; he’s my great-uncle, my father’s father’s brother and he never belonged to me not really because I had to compete with cousins and siblings and my father who loved him more than I think he might have loved my grandfather. I don’t remember my grandfather. I remember a man who was not my uncle.

Captain America is not gay and neither is Bucky Barnes but in the movies they fused him with Arnie Roth so Steve could have him before the war and Arnie was gay later so that’s a little bit like one of them being queer and if one of them is queer then both of them could be. They could be. This is what being online was like for me when I was thirteen and fourteen and twelve and sixteen and twenty. This is what being queer and nerdy and a little bit freakish is like.

History is what gets written down but it’s also what parents tell you when you are small that has never been written down before it’s also the things that never got said it’s also your father sitting you down at sixteen seventeen in your new front room with the big dark yawning window to tell you your greatuncle could have been.

He could have been.

I am thinking about the stories I was told and the stories I was not told and when I was six fi ve four seven my father told me that my uncle my great-uncle once punched a number of his

classmates for calling him something and my father has never told me what it was they called him but I think about crossing paths with a boy in my school who knew the name I was called before I found the real one and he smiled and his friend smiled and his teeth were white and he had scratchy hairs on his chin where he wanted so badly to grow a beard like my father’s and he said a name that pierced my ears like high shrill sound and I could see the future stretch before me endless full of smiling white teeth and scratchy failed beards and the sound the sound the sound I did not want and his shirt was cold in my hand and his eyes were big and round and scared and I have been polite my whole life I have not started fi ghts my whole life (the point of the story was that my great-uncle did not hurt anyone until they laid a hand on him) and that’s not my name. Please use my name.

Is that your name? He was shorter than I was. He didn’t feel shorter when he filled my ears with the sound of flashbangs. Nod nod it’s my name it’s the only name I will not be quiet I will not let sound drown me I will not let my nieces and nephews tell their children I could have been.

There is no comic from nineteen forty where Captian America talks to his gay friend because his gay friend wasn’t gay until nineteen eighty and that’s forty years and we spent them at war with Vietnam and Korea and Iraq and my great-uncle was going to be drafted and he signed up so he could choose to work in intelligence rather than become a footsoldier in other people’s wars and so there is no comic issue where I looked at him and I knew. And there is no other issue to read because there never is when your parents are from small towns and big cities and when they tell you he could have been they also say it’s no one else’s business and so don’t tell anyone. And when they go to dinner at your great-uncle’s best friend’s house to reminisce you wonder if he knew or if anyone is going to say

something and think about him sitting on the stoop with Arnie or has no one at the table cracked a comic in years and am I the only one who still reads.

I read. I read. I read. There are so many places that could be and in my mind they are real they are real when I read them as long as I see them they are true and I think “and” might be the most wonderful word in the world because it means “with” it means “also” it means “more than one” it means “I am not alone and no one left me here to tell the children they aren’t the only ones when they grow up in my brother and sisters arms oh God, the children I am okay I am alive but the children need someone to understand who doesn’t die and leave behind only what could have been.” I read about Captain America and Bucky Barnes and about abortion bans and discrimination laws and how fucking lovely it is to be a person like me in America and I am I am I am. When I grow up I will hold my children and my sibling’s children and I will tell them what I am, what the comics in my arms are and aren’t and what they could be if we want it. That’s all it takes is to want it.

When I grow up, I will find a way to wear dresses that does not burn like acid on the back of my tongue and I will scream and I will shout at the top of my lungs that I am here and I do not understand and I do not want to be fused and forgotten to make room for someone cleaner. At night when it is dark and I remember the night I was told a secret about my great-uncle, I wonder if I am Arnie Roth or Captain America or Bucky Barnes and if I am going to keep this like the intelligence he gathered for people with stars and stripes on their uniforms each a knock-off Super Soldier and when I am only what gets written down about me I wonder will anyone mention those fanfictions I read?

Or will they say I could have read them.

fall 2025 vol. 2, no. 1