What's "Classic" About "Classical"?

Example V.1 Kansas City Strip Steak1

"The Kansas City Strip. Oh yes Sir, the classic choice!"

My father had taken the family to dinner at a club of which he was a member. We had a particularly oily and obsequious waiter and when my dad told him his choice for entree the waiter gushed his approval. My brother and I eyed each other, knowing each other's thoughts: "It's just a steak, not a Rembrandt. Chill out. The tip will be fine."

"Classic" and "Classical" are problematic terms for us. We have "classic rock" radio stations. And "classic" cars. Warner Bros.Discovery offers "Turner's Classic Movies" and in 2013 Pope Francis referred to "religious classics", texts he thought had proved stimulating and mind expanding, "meaningful in every age," apparently embracing Gilgamesh to Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet 2 NASCAR maintains a YouTube page of "classics" (there are a lot of crashes). There's a similar YouTube page for the "Top 10 Classic SNL Sketches of the 1980's" (a lot of

1 The Kansas City steak is a tender cut of beef with marbling throughout the meat, cut from the short loin of a cow and served with the bone intact.

2 Francis: Evangelii Gaudim, Rome: 24 November, 2013. Paragraph 256. “At other times, contempt is shown for writings which reflect religious convictions, overlooking the fact that religious classics can prove meaningful in every age; they have an enduring power to open new horizons, to stimulate thought, to expand the mind and the heart.”

laughs) and the American Association of Retired Persons has the YouTube page "10 Classic Sports Moments to Watch Again and Again." In history, we talk about "classical antiquity", by which we mean the eight hundred years in Greece and Rome from about 500 BC to 300 AD and we have to include the "antiquity" because the French, following Voltaire (1694-1778) who called them nos auteurs classiques, use "le classic" to describe their culture during the reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715) and the "classic" because that ancient period doesn't include the cultures of Egypt and Mesopotamia, which are very important and great but aren't considered "classical" (and we ignore the contemporary cultures of India and China). We have "classical architecture" (more Greek and Romans) and "classics" in literature, which can be anything from Dante's Divine Comedy (14th Century) to Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (20th Century). And it gets trickier. In the West, there's a particular kind of music that we call "classical." But when we talk about the history of music in the West, we refer to the period between 1750 and about 1810 as the "Classical Period." This is the music of Mozart and Haydn and their contemporaries, which I guess we probably should call "classical classical" music, which sounds like we're stuttering. But again we have a problem with the French, who sometimes think of la musique francaise classique as stretching from the founding of the Académie de Poésie et de Musique in 1571 (you'll remember that academy from Chapter Three) to the 1790's and the French Revolution. So to be clear, we might have to describe the music of Haydn as "classical classical non-classique."3 Perhaps thinking about the stuttering, in 2004 the American music critic Alex Ross wrote "When people hear “classical,” they think “dead.”4

Example V.2

NASCAR YouTube page

It looks like "classic" is a synonym for old, even dead. Old rock, old movies, old literature, old television, old buildings, old history (not all old history but just some of it), old sporting events old people like to watch because it reminds them of when they weren't so old (same reason old people like to listen to "classic rock"). But "classic" isn't always old.

3 Daniel Heartz: "Classical", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie, vol. 4; London: MacMillan Publishers Limited, 1980.

4 Alex Ross, "Listen to This," The New Yorker, February 16 & 23, 2004

Sometimes it's new. American Major League baseball has an all-star game known as "The Midsummer Classic." Numerous organizations in the United States host charity fundraisers they call "golf classics" (I gave up counting at 165, "Dan Hogan Golf Classic," "Roscoe Brown Golf Classic," "YMCA Golf Classic", there are a lot). There's a limousine service in Los Angeles called "L.A. Classic Transportation" (yes, they do offer Rolls Royces). We have "classic cuisine" (of course we must use the French cuisine instead of the English cooking because we think the French is “classier”) and even here we apparently have a subcategory: Kansas City strip: "classic classic," which reminds us of Mozart's "classical classical non-classique" (stuttering again). And we've all heard something being breathlessly praised as an "instant classic!" exanimation mark included.

It's all confusing and a bit silly. But there's more. Let's go back to my dad's steak and that oily waiter. He was trying to flatter my dad. He was saying that my dad's choice showed him to be a man of superior taste, of sophistication who had the worldly knowledge to know the best and expect it, someone who was a member of the elite, someone set apart from the rabble.

That "set apart from the rabble" is important because it literally takes us back to our term's ancient origins. Aulus Gellius (ca 125 AD - ca 180) was Roman writer. In his Noctes Atticae he uses the word classicus to differentiate between the best writers of his time and the rabble, the proletarius (although classicus, and particularly classis, had more meanings than just that literary, and sociological, one) 5 In 1604, Robert Cawdrey (ca. 1538 - ca 1610) published the first edition (there were to be three more) of his marvelous A Table Alphabeticall containing and teaching the true writing, and understanding of hard useful English words , gathered for the benefit and help of ladies, gentlemen, or any other unskillful persons. Whereby that they may speak more easily and fluently, have a better understanding many hard English words, which they shall hear or read in Scripture, Sermons, or else where and also be made able to read at the same aptitude themselves.6 This is generally regarded as the first dictionary of the English language and Cawdrey includes an entry for "classick:" chiefe and approued "Chief and approved," here we have the core of a common meaning of the term today: "of the first class, of the highest rank of importance, constitution and acknowledged standard or model, of enduring interest and value"7

The importance of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe(1749 –1832) to German culture probably can't be over emphasized. Poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, philosopher even what today we would call a "social influencer" (he created a rage for young men wearing yellow vests) he was one of the most significant figures of an age of titans that included Napoleon, Washington, Beethoven, and Voltaire. In conversations about their poetry with his fellow poet and playwright Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (1759 1805), Goethe used "classical" not as a mark of excellence but instead as a sobriquet for a particular style, a style distinctive from the "romantic."

5 Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae, 19.8.15. Ite ergo nunc et, quando forte erit otium, quaerite, an "quadrigam" et "harenas" dixerit e cohorte illa dumtaxat antiquiore vel oratorum aliquis vel poetarum, id est classicus adsiduusque aliquis scriptor, non proletarius." https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Gellius/19*.html

6 It shouldn't be overlooked that Cawdrey includes "ladies" and "unskillful persons" in his title. His intention was to help people understand the Bible as they individually read it and heard sermons preached from it. As a Puritan sympathizer, these were populations Cawdrey included in his literacy program.

7 OED Classical etc.

The idea of the distinction between classical and romantic poetry, which is now spread over the whole world, and occasions so many quarrels and divisions, came originally from Schiller and myself. I laid down the maxim of objective treatment of poetry, and would allow no other; but Schiller, who worked quite in the subjective way, deemed his own fashion the right one, and to defend himself against me, wrote the treatise upon 'Naïve and Sentimental Poetry.' He proved to me that I myself, against my will, was romantic, and that my 'Iphigenia,' through the predominance of sentiment, was by no means so classical and so much in the antique spirit as some people supposed. The Schlegels took up this idea, and carried it further, so that it has now been diffused over the whole world; and every one talks about classicism and romanticism of which nobody thought fifty years ago 8

We find "classic" applied specifically to the works of musicians in John Birchensha's (active 1664-1672) translation of Johannn Heinrich Alsted's (1588-1638) Latin treatise, Templum Musicum. On the book's final page, as a summary of the whole work, the reader is enjoined to "consider those melopoetic Classic's and prime Musicians, Orlandus and Marentius" (melopoetic means skilled in making melody) [Ex.V23]. In 1829, Vincent Novello (1781-1861) and his wife Mary, kept a journal of their travels in Europe. Novello was a highly regarded English musician and is best remembered today for founding the Novello music publishing house, a firm that still exists. In Vienna, the couple attended high mass at Example V.3 the Hofberg’s Chapel Royal, hearing Templum musicum, final page9 Mozart’s Mass in D, No. 6. Vincent wrote:

"This is the place I should come to every Sunday when I wished to hear classical music correctly and judiciously performed.”10

John Comfort Fillmore (1843-1898) was one of America's most important 19th-Century musicians. Trained at Oberlin College in Ohio and finishing his career at Claremont, California's Pomona College, his far-ranging interests lead him to write books on the history of piano music, harmony, and the music of the Omaha Indians. In his 1885 A History of Pianoforte Music he defined classical music as "music having a permanent interest and value" and he was one of the first writers to go further and suggest that the music of the late 18th century possessed these

8 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Conversations With Eckermann (1823 1832), translated by John Oxenford, edited J.K. Moorhead, Da Dapo Press, 1998.

9 Johann Alsted Templum Musicum, page 94, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/muspre1800.100280/?st=gallery

10 Vincent & Mary Novello, A Mozart Pilgrimage, Being the Travel Diaries of Vincent & Mary Novello in the year 1829, transcribed and compiled by Nerina Medidi di Marignano, edited by Rosemary Hughes, London: Eulenburg Books, 1955, p. 181. This is the chapel where the famous Vienna Boys’ Choir continues to sing.

qualities in ways that were superior to other eras. At least in American understanding, the "classical era" of Mozart and Haydn was born.

What have we learned? Perhaps the most important thing is that the notion of "classical" referencing some kind of superiority goes back to its Latin use in the second century and that this use of the term continues to this day. With the important exception of Goethe, to be "classical" is to be the best of its kind. But who's to make that decision? Who's to decide what's "best"? And what are the criteria for making that decision? Going back to that waiter, he was the one who apparently decided that the Kansas City Strip was the "best of its kind" and he made that decision to flatter my dad in the hopes of increasing the tip. He made that decision for his own economic purpose; if my dad had ordered meatloaf he probably would have said the same thing.

And even putting that question aside, who decides what's best and why and it's a very important question, perhaps the most important question and one we'll return to in the last chapter what about all those varying "classics" within music? We have the "classical classical" of Mozart, and the "classical classical non-classique" of the French, and Goethe's "classical" as an oppositional category to "romantic." And then we have this.

Billboard, Rolling Stone, and the National Endowment for the Arts have each published lists of "best songs," Billboard ranking the "500 Best Pop Songs since 1958" in 2023, Rolling Stone ranking 500 songs in 2024, and The NEA ranking 365 songs in 2001 (all these rankings were of recorded songs). Here are the top five songs from each list [Ex.V.4].

Example V.4 comparative list of top five songs11

11 Billboard list: https://www.billboard.com/lists/best-pop-songs-all-time-hits/5-kelly-clarkson-since-u-been-gone/ Rolling Stone list: https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/best-albums-of-all-time-1062063/rufus-chakakhan-ask-rufus-1062734/ ;

NEA list: https://web.archive.org/web/20120324105252/http://www.riaa.com/newsitem.php?id=B3DB4887-39EEF70A-8C7A-3B81B66B2C44

The Billboard and Rolling Stone lists were published for the purposes of attracting readers to the publications and were thus parts of the corporations' business strategy of drivingup stock price. The National Endowment wasn't established to benefit private shareholders, but instead to "develop and promote a broadly conceived national policy of support for the humanities and the arts in the United States, and for institutions which preserve the cultural heritage of the United States. . ."12 Yet because The National Endowment's ranking was done for the purposes of providing educators with music curricula for public schools, developed and distributed by the Scholastic Corporation, a New York City based publisher with an annual revenue of 1.5 billion dollars focusing on pre-Kindergarten through twelfth-grade instructional materials, there was a commercial engine driving that list as well (this "Songs of the Century" curriculum was to be given free of charge to ten thousand fifth-grade teachers in "key areas nationally" in its inaugural phrase, the curriculum was to be purchased thereafter).13 So, as with my dad's waiter, we're back to the possible self-serving use of "excellence."

We'll come back to this, but we must address the more obvious problem first. I don't think anyone would look at those fifteen pieces and call them "classical." Yet, as the finest of their type, they certainly fulfill the primary quality of a "classical piece." And because Otis Redding's "Respect" is the only piece to appear in the top five songs on more than one list, it would be reasonable to say "Respect" is the most classical piece of all classical pieces. But I think we would all would find that ridiculous, or at least very curious, and not because "Respect" isn't a great piece of music for a lot of people but instead because it doesn't fit with the way we customarily use "classical."

There are great pieces of music, the best of their type, that we don't call "classical;" in our last chapter we'll look at Henry Mancini's and Johnny Mercer's extraordinary "Moon River" and Pete Seeger’s “If I Had a Hammer” and later in this chapter we'll study a song by Dolly Parton. We’re going to find out that these are great works of art but we wouldn't call them "classical music." We recognize that there's something different between them and the kinds of pieces we recognize as "classical" and that difference isn't in their artistic value. It lies someplace else.

In the first two chapters we addressed the definition of music. We need to to circle back to those opening chapters and now deal with the matter of taxonomy, or classification. Knowing what music is, we now need to know what kinds of music there are. But before we begin, two caveats. First, the boundaries between these definitions are porous, and second, none of these categories reflect artistic excellence. To label something as "pop" or "folk" or "classical" is not in itself to make a judgement about its artistic value. The placement in a category is based on something else; I know I’ve said that before but it needs to be remembered.

I12 NATIONAL FOUNDATION ON THE ARTS AND THE HUMANITIES ACT OF 1965, NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS FISCAL YEAR 2010 APPROPRIATIONS, AND RELATED AGENCIES, 1 August 2010, 20 U.S.C. § 951 (2010), 4 20 U.S.C. § 953 (2010) § 953; https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Legislation.pdf

13 RIAA, NEA Announce ‘Songs of the Century’ https://web.archive.org/web/20120324105252/http://www.riaa.com/newsitem.php?id=B3DB4887-39EE-F70A8C7A-3B81B66B2C44

Fundamentally, there are three kinds of music: 1) folk; 2) pop; and 3) classical. We'll begin with the second category, "pop" because it's the easiest to define and, at least in the United States, the most significant.

Example V.5

Billboard, September 19, 1960 top of first page

"Pop" is short for "popular." Pop music is music that's popular. People like it and they show that they like it by listening to it, buying it, and attending events where it’s performed. And all that popularity can be tabulated, valued, and sold. We mentioned Billboard earlier when we looked at those three lists of "best" songs. Billboard is probably the most import publication in music business, the equivalent of The Wall Street Journal for investment and Variety for theater and film [Ex. V.5]. Founded in 1894 in Cincinnati as a journal devoted to advertising, by the 1930's Billboard had shifted its focus to music: hearing it performed live, broadcast on the

radio, and reproduced on phonographs. It published its first "hit parade" in 1936 and started featuring a "record buying guide" three years later. In 1940, record sales were tabulated in its "Chart Line" and this was followed in 1944 by a tabulation of juke box plays called "The Music Box Machine." By 1987 Billboard published eight charts and that expanded to twenty-eight charts by 1994. Today, Billboard publishes data about one-hundred and fifty categories [Ex. V.8].

Once a week, Billboard publishes data gathered about recordings from radio stations, physical and digital sales (data gathered from Nielsen and SoundScan), streams, Youtube and TickTock views, and even playlists submitted by Billboard approved disc jockeys. The results are posted on the firm's web site. The "Hot 100" is the most anticipated posting [Ex. V.9]

The charts for the other categories are similarly formatted. The "Hot Rock & Alternative Songs" chart is typical. [Ex. V.10]

Example V.10

Billboard "Hot Rock. & Alternative Songs;" week of June 15, 2024

How Billboard tabulates and weighs that diverse data is complicated and nuanced. In 2013 the company revealed that its "Hot 100" was achieved through a point system that was 3545% based on sales (of any kind), 30-40% based on airplay, and 20-30% based on streaming.14 But that report leaves 30% of "play" between the percentages and it isn't clear what criteria Billboard might use in their final reckoning.

Whatever guides Billboard's decisions about how high or low something is placed on their lists, it's essential to note that the various lists are entirely business driven. The charts track

14Gary Trust: "Ask Billboard How Does the Hot 100 work?" 09/29/2013, https://www.billboard.com/pro/askbillboard-how-does-the-hot-100-work/

how people buy music, either through actually purchasing physical CD's or vinyl albums, listening to music on various membership streaming platforms, or "purchasing" it with their time, which is what we do when we listen to music on the radio or various "free" on-line platforms or hear it at a club If we go back to our original point that the primary characteristic of "pop" music is that it's popular, Billboard is THE metric of popular music. There is a marker of excellence in popular music, and that marker is charted by Billboard. The higher the music charts, but better the piece, better because it’s more popular.

That's a very important point and there's much more to discuss here (for one thing, you might think it too cynical, it’s not). We'll circle back to it and Billboard but before we do we have to look at that other very important list, the Grammy Awards.

Unlike Billboard's charts, which are published weekly, the Grammy Awards are given yearly by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (usually abbreviated as "The Recording Academy"). Like so many things in Hollywood, the Recording Academy had its origins in a publicity stunt mixed with envy. Wanting to promote Hollywood tourism and driveup sagging property values along Hollywood Boulevard, in 1953 the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce hatched the idea of a "walk of fame." The walk would promote "the glory of a community whose name means glamour and excitement in the four corners of the world," a glory

15 Grammys Blackstone received in 2006 for William Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and Experience Photo courtesy of Jerry Blackstone

that by the mid 1950's had grown a bit seedy.16 After imposing an additional one and a quarter million-dollar tax assessment on Hollywood property owners to pay for it (which is close to fifteen-million 2024 dollars), the walk received its first permanent "star" in 1960. The Chamber of Commerce put together a committee of entertainment moguls to select who would be honored by a star. But when the committee's musicians discovered that the agreed upon criteria for inclusion would exclude many in their business they decided to create their own prize.17 Together they formed the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Modeling their award on the Oscars, which the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had first awarded in 1927, and the Emmy, first awarded in 1949 by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, the National Academy invented the "Grammy." If the movie and TV folks were going to have their big awards, music people were going to have theirs too. The first Grammy was awarded in 1959. Recognizing the commercial importance of Spanish-language music, the Academy spunoff separate Grammy Awards for Spanish and Portuguese music in 1989 and in 1997 established the Latin Recording Academy. The Latin Grammy Awards are given for projects in Spanish or Portuguese and is an event and process separate from the Grammy Awards (although there remains a "Latin" category in the older awards).

Grammys are given in “categories” arranged under “fields.” Both the number of categories and fields change, reflecting changes in the market and even politics. In 1958, twenty-eight awards were given. In 2024 the Academy awarded ninety-four Grammys in twentyseven fields but for the 2025 ballot the number of fields was slashed to eleven [Ex.5.12].18 Fundamentally, the changes reflect the market. Rap was first included 1989 (it's estimated that hip-hop has controlled about 28% of all music consumption in the United States since 2020)19 Polka was included as a category in 1986. It was dropped in 2009. The reason given was that the elimination was required to keep the Grammys "relevant and responsive . . . within a dynamic music community."20 Because practitioners of Hawaiian music felt themselves slighted by the lack of awards given to their music, a Grammy Award for "Best Hawaiian Music" was introduced in 2005. It was retired in 2011. The "Best Regional Roots Music Album" category was invented in 2012 as a catch-all for polka, Hawaiian, Native American, Zydeco, Cajun, and

16 https://walkoffame.com/history/

17 The committee included five highly accomplished musicians and music executives: Dennis Farnon (1923-2019), head of RCA's West Coast A&R department; Paul Weston (1912-1996), West Coast Music Director of Columbia Records (and composer of "Day by Day"); Sony Burke (1914-1980), a composer, conductor and arranger with Decca Records; Lloyd Dunn (1907-1991), vice president of merchandising and sales at Capitol Records, and Jessy Kaye, producer and engineer for MGM. Paul Grein: "Dennis Farnon, Last Survivor of the Recording Academy's Five Founders, Dies at 95". Billboard, 06/21/2019; https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/dennis-farnonrecording-academy-founder-dead-95-8517056/

18 Paul Grein, “Here Are the 11 Fields on 2024 Grammy Ballot & Categories They Contain: Complete List, Billboard, 06/16/2023. https://www.billboard.com/lists/2024-grammy-ballot-fields-categories-complete-list/rockmetal-alternative-music-field-6-categories/

19 Jordan Rose, "Don't Call It a Comeback: Rap is Rebounding in 2024", COMPLEX, April 17, 2024, https://www.complex.com/music/a/j-rose/rap-music-decline-popular-again-2024

20 Ben Sisario, Polka Music is Eliminated from as Grammy Award Category," New York Times, May 10, 2010. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/05/arts/music/05polk.html

General Field

Record of the Year

Album of the Year

Song of the Year

Best New Artist

Producer of the Year, Non-classical*

Songwriter of the Year, Non-classical*

Pop & Dance/Electronic Music Field

1. Best pop solo performance

2. Best pop duo/group performance

3. best pop vocal album

4. Best dance/electronic recording

5. Best pop/dance recording

6. Best dance/electronic music album

Rock, Metal & Alternative Music Field

1. Best rock performance

2. Best metal performance

3. Best rock songs

4. Best rock album

5. best alternative music performance

6. best alternative music album

R&B, Rap & Spoken Word Poetry Field

1. Best R&B performance

2. Best traditional R&B performance

3. Best R&B song

4. Best progressive R&B album

5. Best R&B album

6. Best rap performance

7. Best melodic rap performance

8. Best rap song

9. Best rap album

10. Best spoken word poetry album

Jazz, Traditional Pop, Contemporary Instrumental & Musical Theater Field

1. Best jazz performance

2. Best jazz vocal album

3. Best jass instrumental album

4. Best large jazz ensemble album

5. Best Latin jazz album

6. Best alternative jazz album

7. Best traditional pop vocal album

8. Best contemporary instrumental album

9. Best musical theater album

Country & American Roots Music Field

1. Best country solo performance

2. Best country duo/group performance

3. Best country song

4. Best country album

5. Best American roots performance

6. Best Americana performance

7. Best American roots song

8. Best Americana album

9. Best bluegrass album

10. Best traditional blues album

11. Best contemporary blues album

12. Best folk album

13. Best regional roots music album

Gospel & Contemporary Christian Music Field

1. Best gospel performance/song

2. Best contemporary Christian music performance/song

3. Best gospel album

4. Best contemporary Christian music album

5. Best roots gospel album

Latin, Global, African, Reggae & New Age, Ambient, Or Chant Field

1. Best Latin pop album

2. Best música urbana album

3. Best Latin rock album

4. Best música Mexicana album (including Tejano)

5. Best Tropical Latin album

6. Best gospel music performance

7. Best African music performance

8. Best global music album

9. Best reggae album

10. Best new age, ambient, or chant album

Children’s, Comedy, Audio Book Narration and Storytelling, Visual Media & Music Video/Film Field

1. Best children’s music album

2. Best comedy album

3. Best audio book, narration and storytelling recording

Example V.12

4. Best compilation soundtrack for visual media

5. Best score soundtrack for visual media (included Film and television)

6. Best score soundtrack for video games and other interactive media

7. Best song written for visual media

8. Best music video*

9, Best music film*

Package, Notes & Historical Field

1. Best recording package

2. Best boxed/special limited edition package

3. Best album notes

4. Best historical album

Production, Engineering, Composition & Arrangement Field

1. Best engineered album, nonclassical

2. Best engineered album, classical*

3. Producer of the year, classical*

4. Best remixed recording

5. Best immersive audio album

6. Best instrumental composition*

7. Best arrangement, instrumental or a capella*

8. Best arrangement, instruments and vocals*

Classical Field

1. Best orchestral performance

2. Best opera recording

3. Best choral recording

4. Best chamber music/small ensemble performance

5. Best classical instrumental solo

6. Best classical solo vocal album

7. Best classical compendium

8. Best contemporary classical composition*

Special Merit Awards*

MusiCares Person of the Year

Lifetime Achievement Awards

Dr. Dre Global Impact Award

Best Song for Social Change

Music Educator Award

Grammy Award Fields (in bold) and Categories, 2025

Go-go music (no, Go-go isn't the music associated with the topless, and occasionally bottomless, dancers that scandalized the late 1960's but is instead a subgenre of funk that became, by law, the official music of Washington, D.C. in 202121). It would be politically unthinkable to drop any of these kinds of music because of the potential charge of racism, but none of them command the commercial status to merit their own category, hence the catch-all field.

I've said that the categories are "market driven" and I'd like to explain that a bit more clearly. First, in order for something to be considered for a Grammy it must be recorded and commercially available through what the Academy calls "general distribution:" "available nationwide via brick-and-mortar stores, third-party online retailers and/or streaming services. ‘Streaming services’ is defined as paid subscription, full catalog, on-demand streaming/limited download services. . . "22 The recording has to be something that can be sold as part of the American capitalist/corporate system. A CD that you're recorded and sold at a booth at the local Renaissance fair or farmers' market, no matter how wonderful it is, won't be considered; it's not part of the profit-driven corporate culture. As we shall see, this isn't a trivial matter.

Second, the categories are recognizable by consumers. Here is the Academy’s requirement for a recording submitted in the “Best African Music Performance” category:

Eligible recordings include vocal and instrumental performances with strong elements of African cultural significance that blend a stylistic intention, song structure, lyrical content and /or musical representation found in Africa and the African Diaspora. Meaning; The African diaspora is the worldwide collection of communities descended from native Africans or people from Africa, predominantly in the Americas.23

Morocco, Egypt, and South Africa are all African countries with “native Africans” and with African “diasporas.” Although the Academy’s requirements would allow submissions here of Amazigh music (Berber music of Morocco), Coptic music (Christian music of Egypt) and even Boer hymns (White South Africans of Dutch descent), I suspect the Academy would disallow the placement of such pieces here What this category is really intended for is music of Black Africans because consumers, when looking for “African music” are looking for the music of Black Africa. Someone looking for music of the “African diaspora” would be perplexed to see on the list a mass sung by the folks of St. Karas Coptic Church down the street from me.

A similar example is the Academy's "Contemporary Christian" category. It would be reasonable to think that contemporary Christian music would be music of today in which Christianity was fundamentally important. The British composer James MacMillan (b. 1959) and Estonian composer Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) would fit that bill nicely since both are internationally known composers and their music is deeply informed by their Christian beliefs (Roman Catholic in the case of MacMillan and Orthodox in the case of Pärt). But their works would never appear in any of the Grammy's "Christian" categories because consumers looking to listen to "Christian Contemporary Music" (CCM) are looking for rock, pop, rap/hip-hop, or possibly Latin music with generally Christian lyrics, the kind of music they'd hear broadcast on Christian radio stations and performed as "worship songs" by "praise bands" in evangelical churches. A new

21 Marissa J Lang, "Go-go is signed into law as the official music of D.C.", The Washington Post, February 4, 2021.

22 67Th Grammy Awards Rules & Guidelines, p. 9

https://naras.a.bigcontent.io/v1/static/67_Rulebook_06.13.2024_FINAL%20(1)

23 P 10 https://grammysubmit.dmds.com/Content/documents/naras/en/CatDescGuide.pdf

recording of Pärt's Credo in a Christian Contemporary Grammy category would deeply confuse them.

In summary, for a recording to be considered for a Grammy it must be literally part of the market; it has to be something that's sold within American corporate culture. It also has to fit-in, or be placed in, a market defined niche.

Remembering this, we’re now in a position to look at the process that can result in a Grammy Award.24

There are three levels of membership in the National Academy: 1) Voting members, who are performers, songwriters, producers, engineers, and other creators currently working in the recording industry. Voting members alone determine the Grammy winners; 2) Professional members, who are people involved full-time in music business: publishers, promoters, agents, writers, executives of labels, etc.; and 3) "Grammy U" members who are people involved with music in its creating, performance and marketing side at the beginning of their careers. Membership at all the levels is through application and nomination. I am privileged to be a voting member of the Academy; there are about 12,000 of us.

Every year, voting and professional members have the opportunity of submitting recordings to the Academy for consideration as potential nominees in specific categories. Media companies that are registered with the Academy may also submit projects for consideration. This process garners thousands of recordings which Academy staff screens for their eligibility and placement in the proper category. While some of the categories are clear (such as the classical: opera category) others are possibly more ambiguous and the Academy employs committees of musicians who are deeply experienced in the various fields to make final determinations about appropriate category placement.25 At this stage no artistic or technical judgments are made about the recordings.

24 https://www.recordingacademy.com/awards/voting-process

25 This is an example of a possible ambiguity. Here are the qualifications for entry in the “Best Alternative Jazz Album” and “Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album” categories: Best Alternative Jazz Album

Screening Criteria. This Category recognizes artistic excellence in Alternative Jazz albums by individuals, duos, groups/ensembles (large or small), with or without vocals. Alternative Jazz may be defined as a genre-blending, envelope-pushing hybrid that mixes jazz (improvisation, interaction, harmony, rhythm, arrangement, composition, and style) with other genres, including R&B, Hip-Hop, Classical, Contemporary Improvisation, Experimental, Pop, Rap, Electronic/Dance music, and/or Spoken Word. It may also include the contemporary production techniques/instrumentation associated with other genres (Instrumental albums in the well-established Smooth Jazz style will remain in the Contemporary Instrumental Category).

Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album

Screening Criteria: This Category recognizes excellence on albums of large jazz ensemble performance , primarily recording with a “big band sound.” Other large ensemble or orchestral jazz recording where a number of musicians come together, most commonly to play arrangement featuring the orchestrational possibilities of a large ensemble of musicians are eligible. In some instances, arrangements may be less structured (so-called “head arrangements”) that nonetheless demonstrate the orchestration possibilities of a large ensemble setting. Generally, these ensembles must contain none or more members to be eligible in this Category (excluding the conductor or bandleader). The ensembles may be billed as ensembles or under the name of a solo artist who is the featured band or orchestra leader. Recording that use synthesizer to imitate the sound of a large jazz ensemble are not eligible in the Category. Large jazz vocal ensemble albums must be entered in Best Jazz Vocal Album.

After submissions have been screened, voting members of the Academy are sent ballots. Some categories may have hundreds of entries, some a few dozen, which makes some areas much more competitive than others (for instance in 2024 there were 978 entries for “Song of the Year” and 32 for “Best Opera”). Although the specific procedures have changed over the years, usually, after casting votes in the General Field, voters are able to cast votes in ten categories spread across three Fields. The Academy relies on an honor system, asking voters only to cast ballots in areas where they have day-to-day professional expertise and to vote only on the basis of the projects’ merits.

These votes are tabulated and, with the addition of projects determined by the committees judging the seventeen “Craft” categories,26 the top vote-getters in each category become official Grammy Award Nominees. Depending on the category there may be as many as eight or as few

Example V.13

“For Your Consideration” campaign for Just 627

as three nominees. Like being an Academy Award Nominee, being a Grammy Nominee is a big deal. It can catapult a career from relative obscurity to potential stardom. If the nominee isn’t an

The question is how much artistic innovation in something entered in “Best Large Jazz Ensemble” propels it into “Alternative Jazz.”? It isn’t immediately clear and judgments regarding things like this are left to the committee and will always be somewhat subjective. 67th Grammy Awards, Rules & Guidelines, The Recording Academy, 2024.

26 Shown by asterisk (*) on Example V.12

27 https://fyc.agency/

American citizen, it even gives the nominee a new legal status: he or she is now, legally, a person of “extraordinary ability” and eligible for a O-1 Visa.

As we will soon see, there’s potentially a lot of money now a stake, and the lobbying for a Grammy can be intense. Technically, the Academy strictly forbids voters being directly solicited for their votes but nominees, or their representatives, can engage in “For Your Consideration” (FYC) campaigns where voters are made aware of the nominee’s project [Ex.V13].28 All voting members are mailed a special Billboard Grammy Award magazine, an extraordinarily luxurious edition with ads placed by various agents, publishers, and labels on behalf of clients. In certain locations in Los Angeles and Nashville, there are even billboards with FYC notices and FYC meet-and-greet soirees.

Voting members are sent their second ballots sometime in the late fall (the rules are the same as for the first). We vote, and the results are announced several months later.

Like the Oscars, the winners are announced in front of a ticketed audience but unlike the Oscars there are two ceremonies, distinguished, to put it bluntly, by the commercial value of the nominated projects. There is a first ceremony, usually in the afternoon, where the winners in the areas of children’s music, audio book, best package, best notes, best historic, etc. are announced. Then that night there’s a second ceremony, broadcast live on a major television network, with stars walking the red carpet, celebrity hosts, and performances by major stars. It’s at this ceremony that the winners of the song of the year, best new artist, album of the year – the potential big money makers – are announced.

That commercial value can be significant. And we’re back to those Billboard charts. In February 2011, Columbia Records released 21, the British singer Adele Adkin’s (b.1988), known as Adele, second studio album; it was released a month earlier in Europe by XL Recordings.29 The project won the 2012 Grammy Award for “Album of the Year” and the Brit Award “British Album of the Year” (the “Brit Awards, ” given by the British Phonographic Industry, are the United Kingdom’s equivalent of the Grammys). Adel was already an internationally known singer. At the 51st Grammy Awards in 2009, she had been named “Best New Artist” and the song “Chasing Pavements” won a Grammy for “Best Female Pop Vocal Performance” (the song also received nominations in the categories “Song of the Year” and “Best Female Pop Vocal Performance”). 21 had been heavily promoted in the months before the Grammy balloting. The previous October, before its release, Universal took the singer to Minneapolis to perform before executives of Target Corporation; Target agreed to sell a two-CD version of 21 (enhanced by additional tracks) and later that month Adele performed in Los Angeles for an invitation-only audience of “tastemakers” at the Largo nightclub. After the release of 21, Adele appeared on the

28 Even here the Academy has rules for what’s allowed. These FYC presentations may not: 1) Cast a negative or derogatory light on a competing recording. Any tactic that singles out the ‘competition’ by name or title is not allowed 2) Exaggerate or overstate the merits of the music, an achievement or an individual 3) Include any Recording Academy trademarks, logos or any other protected information. Logo use is reserved for paid Recording Academy sponsors or partners 4) Include entry list numbers or category numbers 5) Include chart numbers, number of streams, sales figures, or RIAA awards 6) Include personal signatures, personal regards or personal pleas to listen to the eligible recordings 7) Misrepresent honors or awards, past or present, received by either the recording or those involved with production 8) Reference the year or the telecast number (i.e., 2023 or 66th Grammy Awards)

29 The track “Rolling in the Deep” was released early on November 19, 2010, as a single lead.

“Today Show” (February 18), “The Late Show with David Letterman” (February 21), “The Ellen DeGeneres Show” and “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” (both on February 24), and “CBS’ The Early Show (February 28). Additionally, one of the album’s cuts, “Rolling in the Deep” figured in a scene of the science fiction movie I Am Number Four, released in theaters on February 18. In March and April, Adele toured Europe performing tracks from the recording, followed by appearances in the Unites States in May and June.30

“Rolling in the Deep” hit the number one spot on Billboards Hot 100 chart the week of May 21, 2011, having already been tracking since January 24 (it stayed as number one for twenty-four weeks). The album’s other cuts also all tracked on the Hot 100 chart (“Someone Like You” and “Set Fire to Rain” both from March 12, “Turning Tables” from May 7, and “Rumor Has It” from August 13). By the time Academy voters had cast their ballots in the early fall, 21 was already a well established hit.

What is astonishing is that after 21 received its Grammy Award, sales for the album exploded 207%. This “Grammy bump” isn’t unique to Adele. When Taylor Swifts’ (b.1989) Folklore won “Album of the Year” at the 63rd Grammys in March, 2021, it was greeted both by a 53% increase in earnings in the week of the award broadcast and the week following and a 12% increase in revenue for her entire catalogue. Grammy nominees or winners or even musicians who perform as part of the televised Grammy ceremony, see surges in earnings ranging from 4% to 400% after the broadcast. And apart from the increase in immediate sales, a Grammy award puts the award-winning musician in a much stronger position to negotiate more favorable contracts with recording labels. Harvey Mason Jr, chief executive officer of the Recording Academy, summed it up:

The attention and excitement around a Grammy win always translates to people more curious, especially if it’s a newer artist. It impacts your ability to attract attention thereby getting you better deals, better contracts. . . hopefully more people are excited to see you and want to listen to what you’ve done.31

“See you” and “want to listen to what you’ve done” means “buy your stuff” (and Mr. Mason leaves something out that’s very important and we’ll return to that). There is a symbiotic relationship between the Grammy Awards and the Billboard charts. Although the charts show recordings’ relative levels of market success and we vote on Grammys based on our views of artistic and technical excellence of marketed projects, appearance on a Billboard chart gives a project a prominence that helps propel it to Grammy voters’ “radar screens” so that it receives consideration and a Grammy award (or even a nomination) drives up a project’s sales.

And the SALES. The world was stunned when something that had been rumored for months was finally confirmed in June, 2024: after a bidding war between several major corporations, Sony Music was buying the entire music catalogue of the music ensemble Queen for one billion, twenty-seven million dollars. From now on, every time a stadium trembles with

30 Mikael Wood, “Adele: The Billboard Cover Story”, Billboard, January 28, 2011; https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/adele-the-billboard-cover-story-4733347/

31 Starr Bowenbank, “Billboard Explains: What a Grammy Award Win Means,” Billboard, March 31, 2022.

“We will, we will rock you” royalties flow into Sony Music. 32

The Queen sale is only the most spectacular sale of a number of purchases that have testified to the value of pop music. It’s worth money. A lot of money. Example V.14 is a list of only some of the most prominent sales since 2006. The confirmed sales are all in the millions of dollars and the rumored and undisclosed sales are assumed to be similar figures (rumored figures are shown by **) All in all, the total of just this partial list is about five billion dollars.

Musician

Queen Sony Music Group June ’24 full catalogue. $1.27 billion 0/4

Rod Stewart Iconic Artists Group Feb '24. song catalogue $100 million** 1/15

Michael Jackson Sony Music Group Feb '24. Half publishing & $600 million 13/38 recorded masters

Enrique Influence Media Dec '23 Name, image $100+ million ** 1/4 Iglesias BlackRock/Warner likeness, partnership.

Christine McVie Harbor View Oct '23

Share of Fleetwood undisclosed. 2/7 (estate) Mac record royalties

Master recording & Katy Perry Litmus Music Sept '23 publishing rights of $225 million** 0/13 five albums

Paul Simon BMG June '23 Simon & Garfunkel undisclosed 16/36 Royalties

Justin Bieber Hipgnosis/Blackstone Jan '23 100% of music, $200 million 2/23 publishing & performing assets

Dr. Dre Universal Music Group Jan '23 artist & writer $200 million 7/26 & Shamrock Holdings royalties

Keith Urban Litmus Music Dec '22 100% recorded undisclosed. 4/19 catalogue

David Bowie Warner Chappell Music Jan '22 100% music $250 million 5/19 catalogue.

Huey Lewis Primary Wave Nov '22 100% $20 million 1/6 and the News

Justin Hipgnosis/ May '22 100% $100+ million** 10/39 Timberlake Blackstone writer's & publishers share of catalogue & publisher's share of performance income

Joey Ramone. Primary Wave Oct '22 Publishing Rights $10 million. 1/1

32 Jem Aswad, “Queen Catalog to be acquired by Sony Music for £1 Billion”, Variety, June 19, 2024. https://variety.com/2024/music/news/queen-catalog-acquired-by-sony-music-1-billion-1236042619/

Musician Purchaser

Phill Collins/ Concord Music Group Sept '22

100% publishing $300 million 8/27 Genesis rights

Gordon Sumner. Universal Music Feb ’22

100% song writing & $300 million 17/45 (Sting) Publishing Group Performing rights

Jason Aldean Spirit Music Group Feb '22

90% of recording $100 million. 0/5 catalogue.

Tina Turner BMG Sept ’21 Singer’s share of $50 million** 8/25 recordings, publishing, name, image, likeness

Bob Dylan Sony Music July '21 all recorded music $150-200 million** 10/38 Entertainment since 1962

Paul Simon Sony Music Entertainment April '21 song catalogue $250 million** 16/36

Bruce Sony Music Entertainment Dec '21

100% of recordings $525 million** 20/51 Springsteen. and songs

ZZ Top BGM/KKR Dec '21

100% of catalogue $50 million 0/3 & all recorded & published royalties

Bob Dylan Universal Music Dec '20 song-writing catalogue $400 million** 10/38 Publishing Group (lyrics & compositions)

Stevie Primary Wave Dec '20 80% interest in songs $100 million 2/15 Nicks Music & brand representation

Taylor Swift Shamrock Capital Nov ‘20

100% rights to Swift’s $300 million** 14/52 first six albums

Smokey Primary Wave Music Sept '16 partial catalogue, $22 million 0/1 Robinson all name & likeness

Maurice White Primary Wave May, ’07 partial interest in $30 million** 7/22 (Earth, Wind Music song catalogue & Fire)

Courtney Love. Primary Wave Oct, ’06 25% of Kurt Cobain’s $50 million 1/7 (widow of Kurt Music song catalogue Cobain)

Example V.14

Examples of prominent music purchases *number of Grammy awards/number of Grammy nominations

Who are these buyers? Sony and Universal are well known, others are not. Shamrock Capital Advisors is a private corporation, founded by Walt Disney’s nephew Roy E. Disney (1930-2009) and wholly owned by the Disney family with an estimated two billion dollars of assets. Hipgnosis Songs Fund was purchased by The Blackstone Group in July, 2024 for 1.6 billion dollars. The Blackstone Group (not to be confused with BlackRock, Inc.) is a New York City based private equity business with an estimated one trillion dollars in managed assets In October, 2021, the firm announced its intention to invest one billion dollars to acquire music

rights and song catalogues (Blackstone also owns the music rights organization SEAC and the MNRK Music Group) 33

BlackRock, Inc. is a multinational investment company based in New York City and managing assets of ten trillion dollars. It’s one of the most famous, and in some eyes notorious, companies in the world today. Founded in 2006, Primary Wave is a privately held company with Germany’s Bertelsmann Music Group (BMG) and Canada’s Brookfield Corporation holding significant interests. In 2016 BlackRock invested three hundred million dollars in the company. Thirteen years later, BlackRock launched Influence Media Partners with an investment of seven-hundred and fifty million dollars, bringing the firm’s commitment to purchasing music right up to one-billion and thirty million dollars. Influence Media Partners is dedicated to purchasing and promoting the “award-winning catalogues of some of music’s most influential female music creators.”34

Iconic Artist Group was founded in 2018 by an initial one billion dollar investment by HPS, Highbridge Principal Strategies, a private company based in New York City with estimated assets of about one hundred and six billion dollars.35 Based in Newark, New Jersey, HarborView was launched in 2021 with a billion dollar financial package from Apollo Global Management, a New York City based asset management firm with approximately five hundred billion dollars under management. In early 2004, HarborView used its portfolio to raise another five hundred million dollars through asset-backed securities.36

In August, 2022, Carlyle Global Credit, part of the Carlyle Group Inc, a private equity, asset management and financial services company with about four hundred twenty-six billion dollars of managed assets, backed Dan McCarroll, who had served as president of both Warner Bros and Capitol Records, and Hank Forsyth, who was executive vice president at Warner Chappell Music with a five-hundred-million dollar to buy catalogues under the corporation invest Litmus Music.37

In May, 2024, publicly traded Reservoir Media Management announced that it had already spent $938 million on acquisitions since its inception in 2007 and looked to raise another $100 million for further purchases.38 Founder Golnar Khosrowshahi (b.1971), a member of an extraordinary Iranian family whose significant wealth was confiscated by the Islamic revolution and eventually had to flee the country for Canada (her father, Hassan Khosrowshai, eventually founded a chain of electronics stores, later expanded into pharmaceuticals and real estate development and served on the board of the Bank of Canada; her brother Behzad is the chief executive officer of DRI Capital an investment firm that purchases royalty streams paid by

33 https://www.reuters.com/markets/deals/blackstone-outbids-concord-16-bln-takeover-battle-hipgnosis-2024-04-29/

34 https://www.billboard.com/pro/litmus-music-500-million-music-rights/

35 https://musically.com/2024/02/16/iconic-artists-group-raises-1bn-and-buys-rod-stewart-catalogue/

36 https://www.billboard.com/business/business-news/harbourview-equity-partners-raises-500-million-debtfinancing-1235631775/

37 https://www.carlyle.com/media-room/news-release-archive/music-industry-veterans-hank-forsyth-and-danmccarroll-partner-with-carlyle-global-credit-to-launch-litmus-music

38 https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/reservoir-media-plans-100m-offering-to-fund-acquisitions-debtrepayment/

pharmaceutical companies to patent holders;39 and her cousin Dara is chief executive officer of UBER and served on the board of directors of The New York Times), has set Reservoir apart by its goal to not only hold the properties of Western musicians but also to become world’s largest holder of Arabic music copyright. Khosrowshahi told investors: “Expanding our portfolio in… important emerging markets, but especially within the Middle East, is highly important to our overall strategy and a key differentiator for us”40 To that end, Reservoir formed a joint venture with Abu Dhabi headquartered PopArabia in 2020 and purchased the catalogue of Egyptian rap duo El Sawareekh and all past and future recordings of Lebanese pop star Nancy Ajran.41

A hundred million here, a trillion there, it’s a lot of money. What this means is that the world’s most sophisticated money managers believe that the long-term earning potential of owning this music justifies the princely prices required to buy it. And you can see their point. A song with a pre-existing fan base doesn’t require a field to be plowed or a crop harvested or a mine dug or factory workers paid to make it or truckers hired to haul it before it can make money. Of course there are expenses. The various platforms have costs and there are always accountants and lawyers but compared with the overhead of running something like a paper factory or a copper mine or even a bakery, the expenses are minimal. It simply sits on a streaming platform and brings in money as people listen to it.

Example V.15

Reservoir Media stock performance, June 25, 2024

But are those prices justified? The sale of Bob Dylan’s material is instructive. In 2022, Billboard estimated the world-wide sales of Dylan’s recordings to be $16 million a year and

39 It’s ironic that the business model of DRI mirrors the business model of Reservoir; both seek to purchase the income generated by creators; DRI the income generated by inventors holding patents and Reservoir the income generated by musicians holding copyrights.

40 https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/reservoir-and-poparabia-expand-presence-in-mena-with-two-newacquisitions-in-egypt/

41 https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/reservoir-and-poparabia-strike-catalog-deal-with-queen-of-arab-popnancy-ajram/

believed that a benchmark being used to value catalogues was about 15 to 20 times annual revenue. Taking sixteen million and multiplying by twenty (the upper limit) we get $320 million. Apparently, Sony and Universal were willing to pay a premium for Dylan’s materials since their combined possible $600 million price tag almost doubles that valuation.42 Will the investments prove wise? Will the repertory prove popular (meaning profitable) over a long time, thirty to sixty years or longer? Of course I can’t tell, but the five-year stock performance of Reservoir shows the stock down almost 30%.43 [Ex.V.15] Sometimes the smartest investors in the world make mistakes; the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers comes to mind.

Example V.16

Secretary of State John Blinken performs in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms as part of the ceremony announcing the PEACE through Music Diplomacy Act September 27, 2023

I began this segment by saying that pop music was the most significant kind of music today. If we can define “significant” as the most frequently performed, listened to, promoted and invested in, I think you can agree that’s right. And we can even go further and say, as the driving wedge in the American entertainment behemoth (or even Levithan), pop music is America’s most significant contribution to world culture. It’s even an official instrument of America’s foreign policy. The 2022 “PEACE through Music Diplomacy Act” authorizes the State Department to partner with the private sector to create programs and events that build “cross-

42 Hannah Karp & Robert Levine, “Sony Music Bought Bob Dylan’s Master Recordings, Now Worth More Than 200 Million”, Billboard, January 24, 2022 https://www.billboard.com/pro/sony-music-bob-dylans-masterrecordings-200-million/

43 https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/RSVR/; June 25, 2024

cultural understanding and advance peace abroad.”

44 45 The primary, private sector partners have been the Recording Academy and YouTube. At a September 27, 2023 ceremony at the Department of State, Harvey Mason Jr, chief executive office of the Recording Academy, and Lyor Cohen, global head of music for YouTube and Google, were joined by Secretary of State John Blinken in announcing several cooperative programs one of which will bring foreign midcareer music industry professionals to the US for mentorship with the Recording Academy and another which will help teach English across the world by bringing American songs into classrooms. [Ex. 5.16] Whether or not any of this helps bring world peace remains to be seen as we remember from Chapters Three and Four, music hasn’t had a particularly impressive record in bringing social harmony but the programs will certainly help foreign musicians network with the American corporations who would like to own their music and potentially create international populations of children whose taste will be wedded and the values of Grammy winners and the Hot 200.46

Remember, the Recording Academy isn’t committed to all music, but only to recorded music that can be sold. Its purpose in cooperating with the State Department isn’t altruistic, it’s in furthering corporate interests (and those interests are even obliquely acknowledged in the legislation for the act). And the interests of the State Department aren’t broadly humane but in specifically furthering American interests; we Americans tend to take it as self-evident that our interests are always humane but we have to acknowledge that there are people in the world who would disagree.

BUT and I think you’ve been holding that “but” for a while through these pages and with growing annoyance isn’t “pop” music popular just because people love it? Isn’t that enough? And isn’t all that rather ham-fisted economic analysis we gone through unnecessary? And isn’t it too cynical? As we’re going to see in a minute, there is a kind of music that people deeply love but isn’t pop and needs to be distinguished from it. And that economic analysis is

44 State Department website: https://www.state.gov/music-diplomacy/

45Here are the justifications for the act. “It is the sense of Congress that (1) music is an important conveyer of culture and can be used to communicate values and build understanding between communities; (2) music artists play a valuable role in cross-cultural exchange, and their works and performances can promote peacebuilding and conflict resolution efforts; (3) the music industry in the United States has made important contributions to American society and culture, and musicians and industry professionals in the United States can offer valuable expertise to young music artists around the world; and (4) the United States Government should promote exchange programs, especially programs that leverage the expertise and resources of the private sector, that give young music artists from around the world the chance to improve their skills, share ideas, learn about American culture, and develop the necessary skills to support conflict resolution and peacebuilding efforts in their communities and broader societies.” H.R.6498 PEACE through Music Diplomacy Act; https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6498

46 Impetus for the act was given by a 2022 opinion piece published in The Hill by Tara D. Sonenshine Sonenshine, an academic with former experience in The State Department, served on the board of “Silkroad,” the arts organization founded by cellist Yo-Yo Ma Golnar Khosrowshahi, founder of Reservoir Media Management, is also a member of “Silkroad.” Remember, one of the purposes of Reservoir is to expand its properties outside of the US. Tara D Sonenshine, “American could use a little jazz diplomacy”, The Hill, August 6, 2022; https://thehill.com/opinion/international/3590272-america-could-use-a-little-jazz-diplomacy/

required if we’re to understand our culture. Let me finish with two examples: one rather private and the other very public.

In the early days of streaming, unless your works were already part of a major label, it was extremely difficult, if not impossible, to get your music streamed on iTunes. Looking for a way to help new and unknown musicians, my brother and I took some of our inheritance and founded a company to try to make that possible. We hired a project manager and a couple of developers, some attorneys, and launched musiquedart, LLC. We were successful in becoming a “aggregator,” partnering with iTunes in placing some new musicians’ music on the platform. Nashville being Nashville, the company received a lot of attention and investors presented themselves. Eventually the company was restructured and renamed and, as its focus shifted, my brother and I sold our interest. After having received the attention of people in the music business across the country and even a laudatory piece about the company in The Wall Street Journal, unfortunately the firm went bankrupt in 2017.47 For a few months, before we sold our interests, I was a member of the board and sat across tables from some of the most influential people in American music: investors, managers, accountants, attorneys, entrepreneurs (although musiquedart focused on classical music and I know we haven’t defined that yet but we will all of the investors in the re-structured company came from the world of pop music). These were decent and highly respected people, but their goal was clear: they liked music OK or some of it but their interest was financial. The music and the musicians were means to an end and that end was the maximum profit of the investors. It was a profoundly important learning experience for me because it disabused me from any notion that something other than profit drove American music. James Carville (b. 1944) was a well-known advisor to Bill Clinton During the 1992 Clinton vs. Bush presidential campaign, Carville, with some ire at having to point out what should have been obvious to everyone, summarized the issues at stake with what has become one of the most famous quips in American political history: “it’s the economy, stupid!” I learned my lesson the hard way: “it’s the money, stupid.”

That’s the first example. Here’s the second.

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum sits in downtown Nashville, kitty-corner from the Schermerhorn Symphony Hall, next door to the city’s over two million square feet futuristic convention center, a couple of blocks south of the honky-tonks of Broadway and three blocks from the Ryman Auditorium from where The Grand Ole Opry radio program was broadcast from 1943 to 1974 (when the show moved nine miles east to a larger theater with better parking and less crime). [Ex.V.17] The museum attracts over a million and a half visitors a year from all over the world (the last time I checked-in with a class of students I was behind a group visiting from Australia) and is estimated to contribute ninety-three million dollars to the Nashville economy.48 Its 1967 charter says that its purpose is to “to collect, preserve, and

47 Nate Rau, “Dart Music, one of Nashville’s most promising music technology companies in recent years, files for bankruptcy protection on Monday”, USA TODAY NEWORK, February 28, 2017 https://www.tennessean.com/story/money/2017/02/28/prominent-nashville-music-startup-dart-filesbankruptcy/98521732/

48 Country Music Hall of Fame and MuseumAnnual Report, 2020, p. 25; https://issuu.com/countrymusichalloffame/docs/2022_annual_report_2023

Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum Nashville, main front

Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

Entrance to 3rd floor exhibition, public exhibits to the left, closed archives to the right

interpret country music and its history”49 and while that’s true it’s also disingenuous. The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum is not devoted to country music but to the business of country music. It’s not too far off the mark to say that it’s an informercial wrapped around an archive costumed as a museum.

After buying our ticket for $29.95 (which is about six dollars more expensive than a ticket to the Louvre and eight dollars higher than a ticket to the Vatican Museums), we take an elevator to the museum’s third exhibition floor [Ex.V18] Most museums allow visitors to wander the collections at will. Not here. Our visit is a scripted narrative carefully managed through the architecture. After passing by cases highlighting Southern 19th-century rural American music and then moving into the early 20th Century, seeing Elvis Presley’s (1947-1977) “gold-plated Cadillac” (it’s not goldplated but a gold trimmed 1960 Cadillac Fleetwood limousine) and the even more impressive fire-arm and silver dollar encrusted 1962 Pontiac that belonged to Webb Pierce (1921-1991), past exhibits of some of the most important musicians’ personal instruments (Maybelle Carter’s Gibson L-5 guitar, Bill Monroe’s Gibson F-5 mandolin, etc.)[Ex.V.19], we’re confronted with what sets these musicians and their music apart from the rest; a display of “gold, “platinum” and “diamond” albums.[Ex.V.20].

49 Country Music Museum and Hall of Fame Annual Report, 2023, https://issuu.com/countrymusichalloffame/docs/dev_2023_annual_report_24_final_digital_1_

And in a spectacular piece of architectural stage craft, we exit the darkened exhibition floor through a door that opens to the museum’s expansive sun-lit atrium now literally in the light and we descend to the lower floor by a free-standing staircase that spirals down, giving us multiple views of a full wall of iridescent “gold,” “platinum,” and “diamond” recordings. We thought we’d seen a lot of those plaques just before, but this is overwhelming.[Ex.5.21]

Example V.21

Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum Spiral staircase descending from 3rd to 2nd floor.

“Gold,” “platinum,” and “diamond” albums are part of an awards program administered by the Recording Industry Association of America (not to be confused with the Recording Academy). Although originally bestowed by individual labels on their best selling projects, today record labels must request that the RIAA make a certification. After an audit, the RIAA awards a certification based on sales: five hundred thousand units = gold album; one million units = platinum album; ten million units = diamond album 50 The wall makes explicit what up to that point has been implied: this museum isn’t celebrating any “country music,” it’s celebrating country music that’s been sold and sold a lot.

50 RIAA lists on its website the status of recordings. https://www.riaa.com/gold-platinum/

Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

Various performers’ costumes and paraphernalia

And if we’ve somehow missed the point, after another floor of exhibits of established musicians’ stage costumes, boots, instruments, and various other memorabilia [Ex.V22] and temporary exhibits focusing on newer musicians the museum has chosen to promote, we’re finally brought to the sun-lit Country Music Hall of Fame.

In 2024, there were 155 inductees to the Hall of Fame. Plaques honoring each of them are hung on the rotunda’s wall (the portraits of the inductees are unfortunately uniformly hideous) [Ex.V.24]. The performers are major stars with multiple Billboard hits and Grammy awards and nominations; the ensemble “Alabama” (inducted 2005), Gene Autry (inducted 1969), Reba McEntire (inducted 2011), Garth Brooks (inducted 2012), and Elvis Presley (inducted 1998) are typical. But 15% of inductees are non-musicians and will be recognized only by industry insiders: label executives, marketing specialists, publishers, agents, broadcast personalities. The text: “WILL THE CIRCLE BE UNBROKEN” (without question mark) is repeated on the rotunda’s cornice.

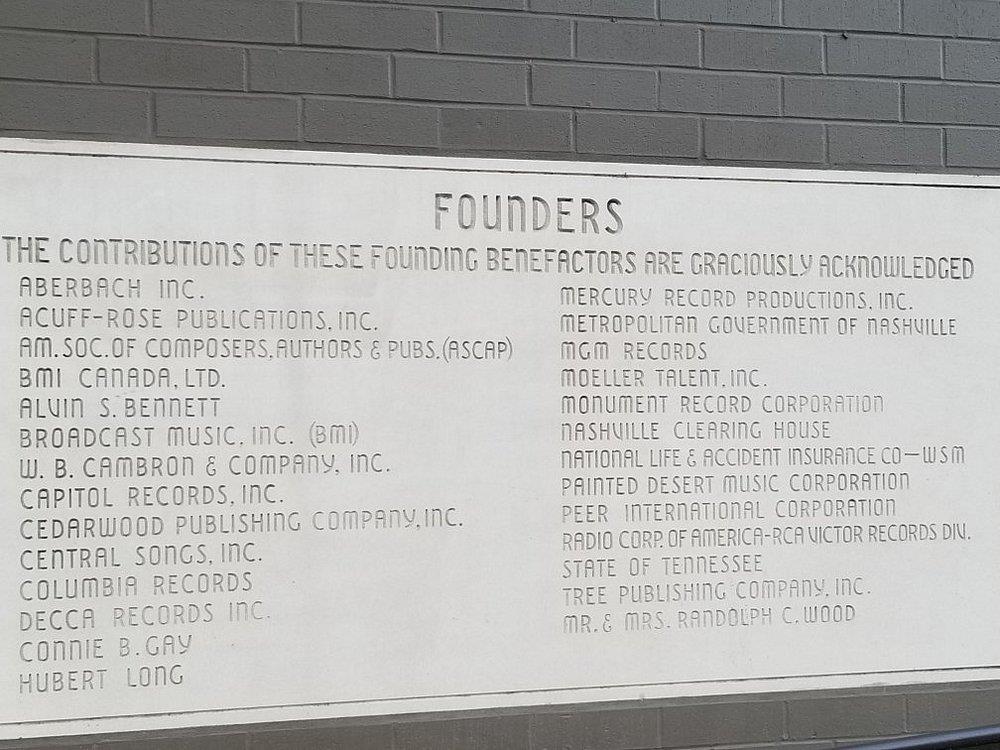

And that unbroken circle? It’s money. After having been steered through several thousand feet of exhibits, past a gold Cadillac, cases of Grammy Awards and walls celebrating the sale of songs in their hundreds of millions, our visit culminates in this shrine-like rotunda, what the great historian of religion Mircea Eliade (1907-1986) would call “a sacred precinct,” a space put apart where the heroes are honored. And who are these heroes and why are they here? They are the musicians who make country music and the people who market it and sell it; together they keep the money stream unbroken by creating fans to buy it. And to remove any ambiguity, the plaque near the front entrance that commemorates who paid for the building clarifies that it’s all an investment: Capitol Records, MGM Records, Mercury Records it’s a list of record companies and publishers, music executives and the State of Tennessee. [Ex.V.25]

It’s deeply ironic. That “WILL THE CIRCLE BE UNBROKEN” text comes from a 1907 hymn where the singers are asking their listeners to remain faithful to their saving faith in Jesus and not to be seduced by the things of this world, so that their Christian fellowship on earth might be continued and perfected in heaven, the circle of fellowship unbroken.51 Alvin Pleasant,

51 Original lyrics: 1) There are loved ones in the glory / Whose dear forms you often miss. / When you close your earthy story, / Will you join them in their bliss? CHORUS: Will the circle be unbroken / By and by, by and by? / Is a better home awaiting / In the sky, in the sky? 2) In the joyous days of childhood / Oft they told of wondrous love / Pointed to the dying Saviour; / Now they dwell with Him above / CHORUS 3) You remember songs of heaven, / Which you sang with childish voice / Do you love the hymns they taught you / Or are songs of earth your choice? CHORUS 4) You can picture happy gath’rings /. Round the fireside long ago / And you think of tearful partings /

“A.P.” Carter (1891-1960), pater familias of the famous Carter Family, re-worked the verse into a maudlin funeral song (stripping it of much of its Christian content) but keeping its chorus and recorded it in 1935 as “Can the Circle Be Unbroken (By and By).”52 The song has been recorded many times since and the chorus, with either “can” or “will,” has become the unofficial anthem of country music. In the context of its use here in the Hall of Fame rotunda that unbroken circle becomes the continuing commercial success of country music, which is pretty much the opposite of the original hymn’s meaning.

Example V.25

Plaque commemorating founders of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.

When they left you here below / CHORUS 5) One by one their seats were emptied / One by one they went away / Now the family is parted / Will it be complete one day? CHORUS. “Will the Circle Be Unbroken”, text by Ada R Habershon, music by Charles Gabriel, 1907. 52 1) I was standing by my window / On a cold and cloudy day / When I saw the hearse come rolling / For to carry my mother away. CHORUS Will the circle be unbroken / By and by Lord, by and by / There's a better home awaiting / In the sky Lord, in the sky. 2) Well, I went back home, home was lonely / For my mother she was gone / And all my family there was cryin' / For our home felt sad and alone. CHORUS 3) Undertaker, undertaker, undertaker / Won't you please drive slow / For that lady you are haulin' / Lord, I hate to see her go. CHORUS Lyrics by A.P. Carter, 1935

Let’s go back to where we started. “Pop music” is music that’s popular and that popularity is tabulated and monetized. And because it is monetized it is esteemed. The Billboard charts, the Grammys, the halls of fame, the investment firms that buy it (and the investors who buy stock in the investment firms), and the United States government programs that use it as a tool of American foreign policy, all of this is only available to music that’s part of our corporate capitalist system, in other words: monetized. I need to be clear here. This doesn’t mean that the musicians making the music aren’t extraordinarily fine musicians, because many are. And it doesn’t mean that this music can’t be of the highest artistic quality, because some of it is (as we shall soon see). And it doesn’t mean that this music isn’t deeply important to people and can be a powerful tool for emotional self-discovery, because it can be and is for millions of people which is why it speaks to them in the first place and they buy it. But it does mean that in the category of which we’re thinking about here, none of these things are of primary importance. Popularity is the music’s raison d'être. And that popularity is proven by its value in dollars and cents.

There’s more to be said here and it’s very important but we’ll return to it at this chapter’s end. We now need to look at what can be called “folk music.”

II

That’s not a scene from a Grand Ole Opry production, a Grammy Awards broadcast or part of a Hollywood movie. [Ex.V.26] It’s a group of neighbors in the mountains of North Carolina who’ve gotten together in a home to show a visiting New Yorker what they do for fun.

53 David Hoffman, “The Best Bluegrass Clog Dancing Video. How & Why I Made It” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJB_HGdGfic

It’s folk music. And folk dancing too, of course. And it’s free. In a home and that “home” is important, we’ll come back to that.

The scene is from a documentary shot by David Hoffman (b.1941) in the home of Bascom Lamar Lunsford (1882-1973). Although an attorney, Lunsford was best remembered as a folklorist and collector of the music of his native Appalachia, of which he was a proud and indefatigable champion. Hoffman had heard of Lunsford’s work up in New York, wrote him and asked if he could come to North Carolina and film him and some of the music of which he was so proud. Lunsford was delighted, invited Hoffman to his home, called in friends and neighbors, rolled-up the parlor carpet, and Hoffman and one assistant filmed the playing and dancing, some of the neighbors watching and toe-tapping and even a couple of the older folks taking a nap through the ruckus.

And nobody had a ticket. It was free. Folks were doing what came natural, getting together and playing and dancing and enjoying each other’s company. And you don’t charge folks for what y’all do natural. It would be like going to the church picnic, putting your platter of fried chicken on the big table and then expecting folks to pay for the pieces they take. And you don’t have to be told to cook it and bring it along in the first place; it’s just what the community does.

“Just what the community does.” That’s as good a definition of folk music as I can think of. Unlike pop, that requires lawyers to write the contracts and accountants to watch the money, and classical music that we’ll soon see requires philosophers to argue about it and schools to teach it folk music does fine just by itself. Work songs, game songs, religious and protest songs, songs of street sellers, drinking songs and mothers singing lullabies none of this needs academic justification or contracts any more than a church picnic requires a dietitian or an Irish pub sing-along demands an auditing.

But having said that, it doesn’t follow that hasn’t been studied because it has, and by some of our most significant figures The notion of “folk music” (Volkslied) as a particular category was first posited by the extraordinarily influential German pastor and polymath Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803). It’s difficult to know where to start with Herder. He was an admired poet (Beethoven, Brahms, Liszt, Schubert, Richard Strauss and Weber all set his poems), translator, and librettist for oratorios and cantatas. As a philosopher, one historian summarized his importance by saying “Herder virtually established whole disciplines that we now take for granted.”54 He had a profound influence on the work of Georg Hegel (1770-1831), Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), and his interpretation theory was foundational to both modern hermeneutics and anthropology. His ideas concerning the relationship between thought and language have been the basis of the modern philosophy of language. Historians credit the Strasbourg meeting between Herder and Goethe in 1770 as one of the pivotal events in German literature. Although only five years Goethe’s senior, Herder gave the twenty-one year old Goethe a deeper appreciation for folk tales and intensified his appreciation of the epic character of Shakespeare, Homer, and Ossian – perspectives which transformed Goethe’s poetry and world view. Five years later, Goethe was instrumental in

54Forster, Michael, "Johann Gottfried von Herder", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/herder/