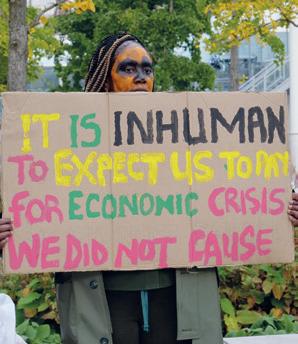

presenting alternative positions on migration

Only two months before the Conservative government was swept aside in 2024, it passed the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Act, paving the way for the deportation to Rwanda of those seeking asylum in the UK.

Within days of taking power Labour scrapped the Rwanda policy, and also announced that it would stop the use of the Bibby Stockholm barge as accommodation for asylum seekers.

Labour supporters welcomed the two swift actions which it had demanded when in Opposition as a step forward towards a more humane asylum and immigration system.

Subsequently, however, Labour has swivelled back towards more hostile policies and rhetoric on asylum and inward migration generally, partly perhaps as a knee-jerk response to growing support for the Reform party in opinion polls.

Within weeks, Labour announced an increase in immigration raids and deportations, and proposed an expansion of immigration detention places, despite a number of past reports showing the harm caused by detention and evidence of abuses in detention centres. A recent announcement said Labour had completed 19,000 deportations since the election, though roughly 14,000 of them were recorded as “voluntary”.

While the rhetoric has not yet reached the levels of toxicity seen under the previous government, including a former Home Secretary’s condemnation of a “hurricane of mass immigration”, there are

worrying signs that Labour is far from ready to scrap the Hostile Environment policy initiated by the Conservative administration in 2012.

The absurd, repeated claims by Prime Minister Keir Starmer that the Conservatives had an “open borders policy” on immigration risk fuelling xenophobic and racist attitudes in the wake of last summer’s riots.

His comments have presented migration as a “threat” to the country, which further stokes anti-migrant hostility, with all the harm that engenders for individual migrants and the communities in which we live.

And it is not just the government’s words that are having an impact: Labour’s policies, too, are replicating the hostility to migrants conjured up under the last government.

The proposed Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill formally seeks to repeal the Safety of Rwanda Act and parts of the Illegal Migration Act. But it continues the trend of legislation treating people seeking asylum as the enemy that must be deterred.

It fails to address why people seek safety in the UK or set out how people can seek asylum in the UK without using irregular routes.

In September the government said it was open to emulating some Italian policies, including establishing asylum processing centres

What an extraordinary 15 years!

When I and a group of migrants and friends established Migrant Voice in 2010 the media was full of migrant stories. But few of the stories were by migrants or quoted migrants. Even large non-government organisations were making decisions about what to say about migrants: we migrants were told “the experts” knew more than we did.

The inevitable result was an increasingly negative debate, inaccurate media reports, wild claims by politicians, inexorably followed by a perfect storm of bad practices and policies, including:

an ill-conceived rash of measures in response to the desperate humanitarian crisis in Calais; imposition of the “hostile climate”, a cap on net migration; increased spending on security measures, some of them crazy, in an effort to stop “small boats”; the “Go Home” van that my family and I and many, many migrants felt was directed at all of us; scandals such as Windrush and the kneejerk banning of tens of thousands of overseas students in response to a TV programme.

It’s a trust-shattering list. And there’s more:

the nature of the Brexit debate, with EU nationals feeling for the first time like migrants in a place they called home; war in Syria and Ukraine and other pressing reasons to leave countries such as Eritrea and Hong Kong; Nigel Farage’s infamous “Breaking Point” poster; the Illegal Migration Act stripping more rights from migrants — and confirming the link between migration and illegality in the public mind; the pie-in-the-sky Rwanda scheme; the drumbeat of the ‘Stop the Boats’ rhetoric. And now, within months of a new government

taking office, we have already experienced frightening riots targeting asylum seekers the bitter fruits of years of negative rhetoric and scapegoating; increased deportations and relentless treating of migration as a ‘problem’; and no sign that the administration will take responsibility for educating the public to the truth that migrants’ are an integral part of the community and make a hugely positive contribution to the country.

Yet despite the politicians’ failings and outbursts of media hysteria, most of the British public appreciate that without migrant workers the NHS would not exist, happily put their elderly parents into the hands of migrant care workers, relish the wonderful new foods and restaurants that have transformed our cuisine, thrill to the medals and excitement generated by migrant athletes, dance and sing along to migrants’ music that has become part of the soundtrack of British life, are entertained by migrant detectives tackling crime on TV, earn their living from migrant businesses, and elect migrant politicians.

These 15 years have been an emotional rollercoaster for migrants and for Migrant Voice staff, politically and emotionally.

Two personal examples of many:

when I first met some of the 30,000 international students whose visas were suddenly and unfairly cancelled for allegedly cheating in an English-language exam, I felt overwhelmed and a sense of terror that such a travesty of justice could occur to young men and women who could be my son or daughter.

when the riots erupted in August 2024 they triggered frightening memories of my first years

With thanks to all the volunteer journalists, editors, photographers, contributors and Migrant Voice staff, network members and trustees who took part in the production of this newspaper.

Thank you to all the funders who support our work.

Thank you

Migrant Voice: Started in 2010 to help fill the huge gap in the debate around migration that was left by excluding our voices, Migrant Voice works to build a community of migrants to speak for ourselves. Over the last 15 years Migrant Voice has trained hundreds of people to tell their stories in the media and through other channels, including our own newspapers like this one, as well as influencing the way the media represents us in general. With offices in London, Glasgow and Birmingham, Migrant Voice and our members speak out to create

in the UK where I experienced racism, verbal attacks and a lit cigarette pushed through my letterbox which started to burn my carpet.

Looking back, Migrant Voice is happy to have made a significant contribution to one of the most notable achievements in this difficult decade: a marked uptick in the number of migrant voices in the media and in the corridors of power. We have been active in every aspect of both traditional and new media, thanks to the trust given to us by hundreds, thousands, of migrants who came to us, opened their hearts and bared their souls to tell their stories.

It has been a privilege to be part of their lives and to help make their lives part of the British story.

This one-off newspaper is itself an example of the many ways we tell our own migrant stories and share them with the public. No single publication or social media meme can cover the amazing variety of migrant lives, but we hope the paper offers at least an introduction to who we are: from the young Ukrainian selling cappuccinos and Borscht in a trendy London cafe, to an African woman fighting to reestablish her life after escaping from modern slavery; from a successful Brazilian businessman who started life here without a word of English, to volleyball players from around the world in a Scottish park; from careworkers fighting racism, to a woman from Pakistan who is literally helping Birmingham to bloom.

Some of the testimonies are bleak, some are inspirational. They are all part of British life yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Nazek Ramadan Director, Migrant Voice

positive change in society: countering xenophobia, forging new ties, running campaigns, strengthening communities, influencing policy and bringing justice.

Printed at Web Print UK: Webprintuk.co.uk, pdf@webprintuk.co.uk, First-floor office, The Old Sorting Office, 21-45 Station Road, Barnes, London SW13 0LF Migrant Voice is the newspaper of the registered Charity number 1142963 and the Not-for-Profit Company 07154151 (England and Wales); SC050970 (Scotland) ‘Migrant Voice’. Published by and @Migrant Voice 2025. Please seek permission before reproducing any of our articles or photographs.

A new attempt is to be made to tackle what has been described as “one of the biggest scandals in British legal history” and compared with the Windrush and Horizon IT scandals.

A direct appeal to Prime Minister Keir Starmer is planned by victims of the scandal, which began in 2014 with a BBC TV report on cheating in an English-language test by some international students at two UK testing centres.

The then UK government quickly asked the company that ran the tests, Educational Testing Service, to investigate. As a result of its findings, the Home Office suddenly terminated the visas of more than 34,000 students, making their presence here illegal overnight. A further 22,000 were told that their test results were “questionable”. Over 2,400 have been deported.

A few thousand stayed, desperate to clear their names. But, stripped of their right to work, study, rent a house or access healthcare, many became destitute and suffered severe health problems.

They have tried to highlight the mass injustice through media and politics. A few who could afford to, or borrowed money, have been fighting – and recently winning –expensive, uphill court battles.

But there has been no apology, not even a serious review of what some courts have described as flawed evidence; no re-issuing of visas, no readmission to universities that they were forced to leave in an instant.

With a new government in power, the students have decided to try to end their living hell by writing to the Prime Minister and asking him to cut the Gordian Knot that is blocking their future. They plan to send the letter within the next few weeks.

Aditya Khadka voices his anger and frustration on behalf of a group of overseas students fighting to clear their names

We can wait no longer.

We are victims of an injustice inflicted on us by the former UK Government’s “hostile environment” policy under Theresa May.

We were never given a fair chance to defend ourselves, yet our futures were destroyed. Some of us have been driven to the brink of mental and emotional collapse.

In many cultures, having a failed immigration status is seen as shameful, and many parents have cut ties with their own children out of fear of social stigma.

Some families took out loans, sold land, or borrowed money to send their children to the UK for a better future. Instead, their children were left to suffer in legal limbo, unable to work or support themselves.

Our parents wake up every day with unanswered questions: Why did this happen? How did our child’s dream turn into a nightmare?

They hear whispers in their communities, face judgment, and suffer humiliation for a cruel act that was never our fault.

The pain of knowing our parents have suffered because of this injustice is unbearable.

This scandal has done more than deny us visas—it has ruined lives.

Some have lost their minds to depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Many have considered suicide, many have disappeared. Some have been hospitalised, placed on medication to control their anxiety and panic attacks.

Many of us have been forced into homelessness, unable to rent a home, relying on food banks, temples, and charities just to survive.

We were once students with bright futures. Now, we are ghosts in a country that refuses to acknowledge our suffering.

We are trapped in a system that has stripped us of our dignity.

For many of us, the fight for justice has come at a devastating cost. Wrongfully accused students spent years entangled in legal battles just to clear their names. Lives were placed on hold, dreams shattered, their futures stolen. While the world moved forward, they remained stuck in uncertainty, unable to work, study, or even plan for their future.

Even for those who finally won their cases, the victory came too late. By the time they were granted visas, the damage was irreversible. Many had lost their families back home—parents who passed away while they were stranded in legal limbo, siblings who moved on with their lives, childhood homes that no longer existed. The very places they once called home had become unfamiliar. They had fought for justice, but when they finally received it, they had nothing left to return to. No family. No support. No future back home.

We have spent thousands in legal fees, desperately trying to prove our innocence.

Some of us borrowed money, sold family property, and drained every penny, believing justice would prevail.

The Post Office Horizon IT scandal showed the devastating consequences of a government refusing to admit its mistakes. Innocent people were branded as fraudsters, forced into financial ruin, and some even took their own lives, all because the government ignored clear warnings of faulty evidence. from page 1

in Albania. Italy’s plan has since been found to be unlawful, yet we have continued to hear talk about the UK trying a similar approach.

We no longer have the performative cruelty of the policy of the former Immigration Minister, Robert Jenrick, to paint over murals in an asylum reception centre for children, yet this is a low bar to claim a change of direction. Instead, we have seen a policy pushed through as a “change in guidance”, thereby denying the ability for parliamentary debate to deny people who have been granted asylum the potential of ever receiving citizenship. This policy is likely to face significant challenges because of its potential

violation of parts of the Refugee Convention.

The “Stop the Boats” catchphrase has been replaced with “Smash the Gangs”, but as with the way the Conservatives’ Clandestine Channel Threat Commander has been swapped for an enhanced Border Security Force, the meaning and impact remains very much the same.

Only days after US President Donald Trump released footage of manacled migrants being forced onto deportation flights, the Labour government did the same. The move was roundly condemned, including by some who agree with deportations, with one Labour MP arguing that it “enables the mainstreaming of racism”.

It is not just asylum seekers or undocumented workers who have come under fire. Both increases in visa fees and reductions in the list of jobs for which visas might be given have been floated as a means to “bring down net migration”,

Migrant Voice’s #MyFutureBack campaign has helped many international students clear their names from Home Office accusations of cheating in Englishlanguage tests.

The students have been fighting for justice for 10 years and Migrant Voice has campaigned with a group of them since 2017.

The campaign aims are:

• a simpler process for appeals — introduce a simple, free, and publicly available mechanism for students to apply for a decision on their case or reconsideration

• the immigration record of every student who is cleared of cheating must be wiped clean; and universities, employment checking services and others informed

• facilitate students’ return to study, or support those on work or entrepreneur visas to find new jobs or restart their businesses — by removing barriers created by the allegation

despite the harm of such policies on individuals and families as well as on the wider economy.

We are less than a year into a possible five-year term of Parliament, however. There is still time for Labour to change the narrative on immigration, to reverse course, rather than repeating the failed policies of the past; to be the party that sank the Bibby Stockholm, repealed the Rwanda Plan and extended the 28-day time-limit period for people who have been granted asylum to find accommodation.

The new government can be a force for change in how we speak about migration. It is time to discuss the realities and benefits of migration, not shouting out soundbites or selected statistics, but focussing on the people themselves, and the way migration benefits the whole country.

‘It impacts every area of our lives. Relationships have been impacted as at one stage we were homeless and family members wanted to help but had their own situations. We have borrowed money from friends and family and it’s stressful asking for money from anyone. My husband’s mental health has been impacted and he suffers from depression due to the stresses of immigration and has not been able to provide for the family.

Children have been impacted as they would have loved to go to university but due to NRPF [No Recourse to Public Funds] and no settled status, universities were reluctant to give them places unless prepared to pay international fees, yet they have grown up here.

Family have died back in country of origin, and due to pending visa applications [we] have not been able to travel and bury loved ones. We have lost our goods in storage as we could not pay for them. It’s been a vicious cycle, these immigration issues, and cause stress.’

‘The cost and uncertainty and inability to plan ahead and incredible anxiety knowing a simple bureaucratic error could result in our being ripped apart as a couple.’

‘I was very depressed and suicidal and anxious and insomniac. I couldn’t live my life. I had no support because no one understood what I was going through or cared to learn.’

‘With the increase in the IHS fee and visa fee it’s going to be almost £12k for us to be together. That’s an insane amount of money to take from someone to be with family.’

‘It’s taken a long time to get in a stable place, during which time we’ve had 3 children. It’s hard work: always the next application hanging over you. Always that doubt and fear at the back of your mind.’

More ammunition for the campaign for a government rethink on Britain’s exorbitant visa renewal fees — which are among the highest in the world — has come from ongoing Migrant Voice research.

The evidence is already clear that the cost of visas has hugely damaging financial, health, familial and social effects on those paying them.

Many families are forced into poverty and debt to pay for the costs. Visa fees price them out of their rights, and reduce their children’s life chances.

Migrants wanting to settle in the UK must live here for at least five years before they can apply for permanent residence, but many are placed on the longer “10-year route” for settlement, doubling the costs and putting migrants in positions of far greater uncertainty and vulnerability.

Two-thirds of migrants in a recent survey said they had been forced into debt to pay their visa costs, with debts of up to £30,000 reported. One said, “I feel like we’re treated as cash cows and political footballs.

“No one in the British public cries out if the Immigration Health Surcharge increases to over £1,000 per year. Most people are not even aware how we are being treated and yet [they say] we are to blame for the dire state Britain is in, not the policies of decades by both main political parties.”

Another migrant giving evidence for the survey said, “It’s obviously quite frightening and difficult to have essentially no safety net to fall back on. We had some issues in the past where we could not pay our rent or purchase groceries, but we were not entitled to any support at all despite having a history of paying tax.” [Most migrants are covered by a policy called ‘no recourse to public funds’, which denies them the ability to get state support.]

Commented another: “It was a slap to the face when they

announced a new threshold increase for family visas.”[From April 2024 the minimum income threshold for a UK family visa rose from £18,600 to £29,000 per year.]

“It sends a strong message that the UK is not tolerant of international, intercultural, and interracial relationships,” she continued.

“We felt penalised and targeted because of my visa situation despite the fact we are in well-paid employment and contributed to taxes and National Insurance etc.”

The usual defence for massive high visa costs is that offered by Seema Malhotra, the Minister for Migration and Citizenship: “Any income from fees set above the cost of processing is utilised for the purpose of running the Migration and Borders system”, thus reducing reliance on taxpayer funding.

Yet visa fees are set at 7-10 times the actual processing costs.

Migrant Voice has been campaigning for a reduction in these costs since 2020. Every day migrants face poverty and destitution as they scrimp and save for fees. Families have been ripped apart, children denied opportunities.

Migrant Voice’s campaign aims to change the system and ensure that migrants are treated fairly and with respect. We urge government to:

• introduce a quicker, simpler, less stressful visa application process

• ensure that visa fees are no higher than the administration cost, with no fees for children

• abolish the Immigration Health Surcharge

• cap all routes to settlement at 5 years

• cut waiting times and improve communication from the Home Office

Tennille Hannah Rolingson

Since moving to the UK in 2016 I’ve spent tens of thousands. of pounds in visa fees. That excludes my university fees and living expenses, which may run into six figures. This is a consequence of a choice I and my parents made to better myself and seize opportunities I could get only here.

I had been attending a British school, so the move made sense. But I started to be aware of the expense of being an international student. I didn’t have access to student finance or a student loan and scholarships were rare. Everything was paid by my parents, and visa restrictions meant I could not really work. But I had never contemplated spending a life in the UK after graduation, and had no reason to stay in the UK.

At the end of 2019, I met the love of my life and everything changed. My now husband, a Lithuanian who had lived in the UK for 10 years, made me envision a life here. My love for him grew along with my love for this country. I had no idea of the challenges that would face me in the quest to live with the one I love.

It’s 2020 and the Covid-19 pandemic is in full swing. I was nearing the end of my law degree and had plans of doing a master’s, potentially qualifying as a solicitor and securing another couple of years in the UK on my Tier 4 student visa. But the costs of extending my stay here were becoming out of reach. Anxiety over my looming visa expiry made me queasy. I couldn’t ask my parents, who had already

sunk their life savings into my education; I couldn’t ask my boyfriend, who wasn’t yet financially in a position to help. It became clear that I would need to give up my place at law school, along with continued life in the UK.

I couldn’t stay. I couldn’t go.

I succeeded in obtaining a two-month visa extension because, as a result of my parents’ own movements at the time, I had essentially nowhere to go. When eventually I was able to leave, I had to leave most of my belongings and along with them, my life.

I eventually made it back to the UK via the fiancé/partner/ spouse route — with delays, interrogation and expense. I

‘I couldn’t stay, I couldn’t go’

thought I had rid myself of the shackles of a hostile system. I could move on with my life and start to build my future.

However, in December 2023 the government declared that the Minimum Income Requirement (MIR) was due to increase from £18,500 to £38,700.

My life in the UK was again under threat. I cried, I screamed, I spiralled. I felt foolish, for letting myself believe that I could be allowed stability and a home here. I started frantically mentally preparing myself for the evitable, while my husband kept reassuring me that it would all work out.

In a bitter-sweet turn of events, things did work out. My

spouse visa renewal was recently approved for an additional 2.5 years when I hope I will be able to secure Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR), which would provide an increased sense of stability.

However, I spent over £4,000, plus £200 for an appointment in London to complete my biometrics — essentially, the most expensive 10 minutes of my life. About £2,500 of the cost was the NHS surcharge payment that allows migrants access to the NHS, a service my 9 to 5 job already taxes me for.

Visa renewal took a huge chunk out of mine and my husband’s savings. Working hard, saving every penny, in hope of using it towards our future and instead having to use it to solidify my stay in a country that on occasion has expressed disdain for my presence, is painful. I have fondness towards this country and even dare call it home, but it has taken from me. I have sacrificed a lot to be allowed to live here, not just physically but financially.

Migrants are tired, exhausted. Yet visa fees, along with MIR, show no signs of being reduced. The pressures of trying to uphold the ‘model migrant’ persona while policies continue to withhold our humanity and keep us much further from having fruitful lives in the UK; needing to explain over and over to people the process we go through to simply have the pleasure of being here. No migrant deserves to have their life in the UKmade inaccessible because it’s been decided that thousands of pounds is a justifiable cost to having a home here.

Majeda Khouri is a foodie with a mission. Or, more precisely, an activist who likes to cook.

She combines the two in the London-based Syrian Sunflower, the social enterprise she set up as she re-made her life after fleeing civil war.

She was apart from her husband and two children, had nowhere to live and as an asylum seeker was barred from working. She spoke little English, and understood less — “people seemed to be talking so fast.

“So I would put earphones on for almost 24 hours a day until I got familiar with the British accent.”

She imported that determination, drive and energy from Syria, where she practised as an architect and, after the outbreak of conflict, became a rights activist. She was detained and witnessed and documented human rights abuses, especially against women and children.

In the UK an early breakthrough came when she met a woman from Migrateful (“In-person cookery classes in London: join us in a journey of flavour and cultural stories while mastering authentic global recipes”): “She asked me, ‘Can you teach me to cook?’”

That led to Khouri doing cookery classes for 15-20 women. But though she loves food, her real interest was the opportunities it opened up for conversations. She was

particularly concerned to challenge and change negative ideas about refugees.

“I told the British women attending the classes] about women in Syria, how they became refugees, how they used their skills, about their bravery, about how they took responsibility, especially those who fled with children after their husbands had been killed or detained.”

This food-and-talk tactic blossomed after she was

‘I translated Health and Safety rules into Arabic’

officially granted asylum: “I needed a job. Because I have these skills and people like my food, I did a lot of supper clubs and Sunday lunches”, introducing people to Syrian food.

Another group, Terrn (The Entrepreneurial Refugee Network], helped her acquire the know-how to establish a company, and switched her onto the idea of a social enterprise because “I wanted not just a business, but to help other women with a refugee background.

“At the same time I was hearing from Londoners and other British people that refugees were ‘taking our taxpayers

money’.” So later she was able to offer jobs to women in Syrian Sunflower. She taught women how to register their own kitchen business and translated Health and Safety rules into Arabic: “I had got the experience, so I transferred it to them.”

Syrian Sunflower now caters for corporate events and weddings. The events have included a meal for 2,000 in Italy (“I didn’t sleep for three days”) and party food for the reopening of the Museum of Migration in London.

She also gives refugee women tips on integrating into British society.

“I even trained them to take children to parks and to school — not to wait for their husband to do it — because they didn’t have the confidence to go out of the house or use transport. They were afraid to talk to people.

“It’s odd to think that as a child and before I married, I didn’t enter the kitchen unless I wanted to eat or drink.

“An interest in cookery only came when I had kids and I wanted them to be healthy and didn’t want to give them any processed food. It was never in my mind that cooking will be my job, until I came to the UK. But it was a good skill.

“Now, through cooking, I share my beautiful culture and tell the untold stories of Syria.”

And fortunately, she adds, “Londoners want to try everything, all kinds of food.”

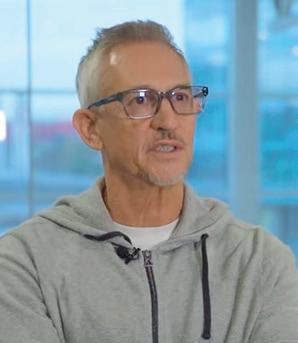

Rafael dos Santos (pictured), an award-winning entrepreneur and senior university lecturer, looks at what it takes to be a migrant entrepreneur. He describes himself as “Brazilian by birth, British by choice”.

“Ask your God to help you, but if you stay on the sofa, he will not.”

Brazilian entrepreneur Rafael dos Santos has a way with words, even in English — a language he didn’t speak when he arrived here 23 years ago. He learned quickly. It’s the first thing to do as a migrant entrepreneur, he says: “Once you master the language, you are yourself again.”

After you grasp the language and at least some of the culture, which is an ongoing learning process, next on his list of barriers are lack of knowledge and of people who can help, which leads to fear, and fear paralyses people: “The people changing the world are those who are not scared of trying, not scared of failing.”

You need to be curious, he counsels, “and curiosity leads to knowledge, and knowledge leads to power — power in many ways. You become powerful so people can’t take advantage of you.”

He believes people are naturally curious, “but when you move countries, fear takes over and you become more frightened of doing things because you don’t know how people are going to react; you don’t know what’s going to happen. If you have knowledge, that kind of fear disappears. Knowledge is power.”

He recalls how frightened he was the first time he sued one of his clients: “I was scared to death to go into a courtroom.” Some time later it was his turn to be sued and he thought, “Oh, I’ve been there; I know what it’s like to stand before a judge. I had lost my fear of being in a courtroom.”

Similarly, after writing his first book, Moving Abroad One Step At A Time, he had to record a two-minute publicity video: “It took four hours because I was mortified at being in front of the camera. I cried. I didn’t like my voice. Because of the experience of being bullied at school, I felt people would laugh at me or wouldn’t like my voice. All those feelings came back. I was feeling the fear of judgement.

“When I learnt to get over it, I did the video in four minutes.

“Now my approach is, ‘If you don’t like my video, don’t watch it.’” Since 2018, dos Santos has recorded hundreds of videos and mentored clients on how to use Instagram and record themselves.

The lack of network and trust are also barriers.

Migrant entrepreneurs need to build a network of people “because if people don’t know you, they aren’t going to buy from you, and it takes time for you to win people’s trust.

“In your own country, that network is ready-made: your parents have built it, your grandparents have built it; you don’t even think about it. You are born into a network; everybody knows you. When you move countries, you have to build that network again.”

Another hurdle is learning local laws and following rules, guidelines, and protocols. For example, “It still baffles me that the UK financial year is from April to April, a system that started on 25 March 1752. Why can’t this be changed to follow most countries? Why not start on 2 January and end on 31 December?”

Despite the problems facing migrant entrepreneurs, he emphasises that the biggest barrier is mindset. Success depends on the individual and determination: “There’s no alternative to a positive outlook.

“I did all the courses available from local governments: accountancy, marketing, planning; I learnt about HR and how and when to pay tax. It opened the doors. Local knowledge should no longer be a barrier to starting a business.”

Positivity and a willingness to learn are how he built several businesses in Britain; how he recovered from a £70,000 loss when an investor pulled out of his company because of Brexit; how he created a successful tech PR company with 250 clients; how he established the Best of Brazil Awards for Brazilians abroad, which has been nicknamed the “the Brazilian Oscars”.

Dos Santos became an entrepreneur “because no one employed me in marketing, which was my aim, so I started an estate agency instead.”

He quotes research that “14 % of businesses are owned by migrants in the UK, and they employ millions of people, making a significant contribution to the UK economy.

“Migrants don’t steal jobs;” he points out, “they do jobs that locals don’t want to do. They aren’t more ‘entrepreneurial’: they start businesses to have a better life.”

Ethnic minority businesses contribute about £25 billion a year and a million jobs to the UK economy, according to the Centre for Research in Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship.

The £25 billion figure is higher than the gross added value of a major British city such as Birmingham or an industry such as agriculture, In addition, migrant businesses are disproportionately engaged in exports and innovation, which are regarded as priority areas for the economy.

This huge and often overlooked contribution of migrants to the economy could be four times higher – £100 billion a year – if changes recommended in the report were implemented, the Centre says.

The businesses that contribute to this often overlooked economic boost range from small to very large: of the UK’s 100 fastest-growing companies, 39 have a foreign-born founder or co-founder, according to Job Creators 2024, a report compiled by Fragomen for the Entrepreneurs Network.

“These immigrant founders come from across the world – with America being the most common origin country, followed by Germany and India,” it says.

“We believe this shows the critical contribution that international talent makes to Britain – without their effort and vision, our economy would be less dynamic and competitive … all of our research has found that immigrants play a disproportionate part when it comes to starting some of the most dynamic, promising and influential companies in the British economy.”

As the recent Museum of Migration exhibition, Taking Care of Business: Migrant Entrepreneurs and the Making of Britain, pointed out, “From the food we eat to the clothes we wear, the apps on our phones to the products in our homes, our lives wouldn’t be the same without migrant entrepreneurs.”

The exhibition, viewable online, tells the stories of some 70 pioneer migrant entrepreneurs, from Stelio Stefanou of Accord (born in Egypt to Greek Cypriot parents), through Michael Marks, born in Belarus and co-founder of M&S, to Trinidad-born Winifred Atwell, one of the biggest pop stars in 1950s Britain who went on to create the first Black hair salon in central London.

When Yelyzaveta Tataryna left Ukraine after the outbreak of war, she had no idea her flight would lead to opening one of the most talked-about cafes in a fashionable central London area.

She spoke little English, knew no-one, had no idea about England, and had never heard of one of the city’s most popular shopping, eating and tourist spots, Covent Garden.

“I had no expectations,” says 24-year-old Tataryna. “I was raised on Jane Austen novels. I’d never been to the UK before. It’s so different from Ukraine — crazy different. Almost everything is different.”

Landing in London with her life packed into suitcases, the first few months were tough. “I didn’t have anyone at all. No friends. I was living in an Airbnb, far from central London, paying £80 a month for a mattress on the floor. To open the door I had to move the mattress!

“People didn’t want to rent to me. I didn’t have any UK credit or a local job. The landlord wanted me to pay a year upfront. Eventually, I paid six months in advance, thanks to my savings.”

As a pastry chef, she quickly realised there was something unique about London’s food scene. “Everywhere I walked I saw gluten-free options. My goodness, in Ukraine it’s hard to find that. But in London, it’s everywhere. I thought, maybe there’s something for me here.”

The eye-poppingly pink and flowery Cream Dream Vegan Pastry Cafe (“every dessert is a labour of love”) was on the way.

She made a bold move.

“I Googled how to open a cafe in London and started from scratch. It said, Make a business plan and find a location near the Thames. So I made a business plan and I found that Covent Garden might be a good venue. I just followed a map

and got off the tube. The first time I saw the cafe space, I thought, ‘This is it.’”

It wasn’t smooth sailing.

“I had to build it up from nothing,” she remembers. “The space needed a lot of work. I did it all myself. I couldn’t afford to hire anyone. But then, through Instagram and TikTok, a group of girls and women with kids, none of them professionals, came to help. They were incredible.”

Tataryna opened the shop on Valentine’s Day 2023.

‘They were queuing down the road.’

“On the first day, hundreds of people came, they were queuing down the road. I had posted every step of the journey online, and people were so excited to see it come to life.”

She smiles as she recalls the chaos. “We didn’t have enough pastries ready, and I even forgot sugar for the coffee! But the British people were so friendly and supportive. We had a sign: ‘English is our second language. Please speak slowly’. The customers were patient, explaining what they wanted. It was amazing.”

She encountered the usual online snarkiness. “I got a lot of negative comments online. People said things like, ‘Oh, she’s a refugee, but she has more than me. She’s taking taxpayers’ money.’

“That’s just not true. I’ve paid £30,000 in taxes already and haven’t earned any money from the business yet. My teenage sister [who followed her from Ukraine] helps manage the place, and we employ 15 people, almost all Ukrainians.”

Tataryna works 12 hours a day (“I got burnt out, so I’m doing yoga”) but remains positive. “There will always be haters, but I focus on the good. People who come to my cafe are so supportive.”

Originally, she says, she wanted just a coffee and pastry shop, “but I quickly realised it wasn’t enough. People wanted sandwiches and hot food, so I expanded the menu to include vegan sandwiches, potato pancakes, borscht, dumplings and even chicken Kyiv — vegan-style!”

The cafe has become a hotspot for Ukrainians in London: “Every month we host charity events to raise money for Ukraine. We donate food and sell lottery tickets for cool prizes like UK wine. It’s our way of giving back.”

It’s not a cheap cafe, but Tataryna offers cut-price coffee for health and social workers, road sweepers, mounted police and others serving the community.

Her sister, a budding filmmaker, is social media manager and does a score of other jobs: “She’s incredible. She was in Ukraine when the war started, and despite the bombings, she was posting on Instagram for me. I wouldn’t be here without her.”

Tataryna is already looking ahead.

What’s next? “Work work work. I want to open a ‘dark kitchen’ [a commercial kitchen that prepares food exclusively for delivery or takeaway]. We don’t have enough space right now. I’d love to bake bigger orders, like birthday cakes, in a separate space and deliver them to the cafe. It’s a big plan, but I’m working towards it.”

Does she hope to return to Ukraine? “I want my business to be independent here, but I want to return home someday.”

Fernanda Silva de Almeida Nunes

Tattooists are not high on the list of migrants to the UK, but several have made their mark here.

“It opened many doors for me,” says Dean Gunther, a 36-year-old Manchester-based tattoo artist from Cape Town, South Africa, about his decision to move to the UK in 2017. A self-taught artist, Gunther has been tattooing for more than 16 years. Since coming to the UK he has developed his style, using realistic elements in vivid colours, gaining international recognition.

In June 2024 he applied for British citizenship, which he describes as an expensive, lengthy process, though he emphasises, “I mean, I love the UK. it has good opportunities, you can make a decent living.”

A bonus of the new location, he says, is proximity to Europe: “There’s conventions every weekend in different towns. And you can just fly half an hour and you’re in a different country.”

Since his arrival he has stopped drinking, which he says was holding him back during his years tattooing in South Africa.

“All that attention that I’d put into drinking all that time, I’ve put now into my work, into my art, and that really elevated me”, he says.

He sees himself staying in the UK.

But his connection to his homeland influences his work, and he often draws on his knowledge and memories of South African fauna when clients ask for nature-inspired designs.

“I know Cape Town [the landscapes of] Table Mountain and Lion’s Head and the proteas [a South Africa plant] like the back of my hand,” he explains.

London-based Ann Chang, a 31-year-old tattoo artist from Taiwan, is also deeply influenced by where she grew up. Her tattoo pieces are “mostly about the scenery and plantations

of Taiwan, where I came from. My mom has a beautiful garden that has a beautiful pond … and it rains a lot as well.”

For Chang, staying in the UK came with visa challenges.

She moved to the UK in 2016, initially with a Youth Mobility Visa. Two applications for a Global Talent Visa were rejected.

The Arts Council, responsible for endorsing artists applying for talent visas, does not recognise tattooing as an art form. Chang put on a traditional art exhibition, Temporary before permanent, which featured temporary stencils, placed on the body to guide the permanent tattoo. The show and the accompanying media coverage helped meet the visa criteria, which was given in 2021.

‘the tattoo chair can be an intimate space’

Although a few tattoo studios are registered as able to sponsor workers, no visa is specifically designed for tattooists. An Arts Council England spokesperson explained, “We would not be able to consider an application from a practising tattoo artist that works in a studio tattooing their designs on people. This is not an area within our arts and culture remit, and there are health regulations, policies and licensing requirements to operate as a tattoo artist which are not within our scope.”

Like memories of hometown scenery, the tattoo chair can be an intimate space: clients share personal stories while artists work on permanent alterations to their bodies.

“It’s like a memento,” says Chang. While she may not remember the face of a client if they meet on a pavement, she’ll instantly remember their story once she sees the art on their body.

Similarly, this feeling of proximity motivated Gunther to

create a podcast that he records while tattooing.

“I find it quite easy to speak to people from all backgrounds,” he explains. He mentions a magician, exprisoners, and a bare-knuckle fighter.

For Oksana Demidova, 28, it’s the personal connection that makes each session different. “Sometimes it gets a bit repetitive, just technical work, right? Because the process is kind of the same thing, if you think about it.”

Originally from Ukraine, Demidova lived in Berlin for two years before coming to London, because it felt like “the right next step”, five days after the outbreak of the war with Russia.

“When you connect on something like art, it’s a feeling that you share, that you both can relate to in some way … it makes me really want to get to know [clients] better, to understand what we have in common — and there’s always something. That’s the most exciting part of every session,” she explains.

Working with linocut techniques that use carved linoleum blocks and ink to print on paper, she creates intricate designs that are then recreated on skin. Demidova says that her early career in Kyiv as a printmaker was formative. The Kyiv art scene, she says, “gets very experimental. You didn’t have anyone to tell you how to do it. So people just go in really interesting, different ways.”

“People are multifaceted,” as Demidova put it when talking about clients. “I’ve tattooed lawyers, software engineers, a quantum physicist. And they’re all very creative themselves. I guess people narrow what people are like, because we can’t really imagine how one person could do so many things.”

Art and creativity transcend borders or visa status, and tattoos can serve as a permanent reminder on someone’s body – regardless of where they’re from – that human connection can be rich, complex and often unexpected.

As artistic director of Hear Me Out, Johanne Hudson-Lett was experiencing all the usual worries ahead of one of the organisation’s gigs: “Will it be well organised and all possible scenarios covered?”

But unlike most music promoters she had other, bigger worries, too: “Will The Unknowns band be here to play on the night? Will an instruction arrive from the Home Office to inform them that they are to be deported or moved from their accommodation to a different part of the country?

“Now, that is fear,” she admits. It arises because the band members are asylum seekers.

They met and formed a band (“We picked the name because there are a lot of talented people out there who are unknown, as we are now”) in an asylum hotel in central London during Hear Me Out workshops. They mix musical styles from the Middle East, Europe and Africa and their songs speak about their homeland, family and hopes for the future.

About 28,000 people a year are locked in UK immigration removal centres and similar settings with no end date. Their lives are stopped while authorities decide their fate. Hear Me Out helps by taking music into the centres — “because music can be freedom”.

‘Will

the band be here to play on the night?’

“We want to give people a voice and to feel human and to feel like they are being treated with respect,” says HudsonLett.

“It also shows there is somebody who cares, because a lot of asylum seekers, wherever they are, whatever places they are in, are so lonely.

“What we want to do with our music is make them feel somebody is listening to them and we will do what we can.”

Band member Kidu agrees about the organisation’s importance: “Honestly speaking. I was desperate, I knew no one. Then through the group I found people.”

The organisation works in two hotels housing asylum seekers in London, at Napier Barracks in Kent (which has been used since 2020 as “temporary accommodation” for those seeking asylum), runs music workshops, and has “two phenomenal bands that we really want to push into the public eye because they’ve got such an important message to tell.”

Helping inform the public about the asylum system

and about the stories of asylum seekers and refugees is important, says Hudson-Lett, “because people only know what they hear on the news, and therefore they are getting only one side of the story.”

Music is a great way to communicate, she adds, “a great way to use your voice, whether through the lyrics you are writing or a song you are singing. So for Hear Me Out it’s a wonderful art form that enables us to bring people together to enjoy at the same time.

“We believe music is a way of people connecting with each other and with their emotions.

“With music there’s no language barrier and music is such an effective way of communicating with people of all ages and different cultures.”

And the Unknowns gig? Was it a success?

Hudson-Lett gives a definite thumbs-up: “It was a true celebration of their incredible talent, their cultures and homelands, and the uniting power of music.”

Hear Me Out: hearmeoutmusic.org.uk The Unknowns full performance

Daniel Nelson

“Detention is the worst thing you can do to a human being, especially one who’s trying to survive. It is cruel.”

That’s Stella Shyanguya speaking. One experience of cruelty is bad enough; it’s twice as bad when you are detained after your life has already been disrupted and you move to what you thought was a safe haven.

It’s triple cruelty if, like Stella Shyanguya, you are detained because of a Home Office mistake.

The France-born, Kenya-raised and legally naturalised British citizen was wrongfully imprisoned in Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre.

If you are unclear about the difference between prison and detention, she will explain: “It feels the same - except that in prison you have a date for release.

“In a prison you are counting down the days, in a detention centre you are counting up.”

Personal restriction, discomfort, constant surveillance, lack of decision-making opportunity, the failure of the Centre to provide the special diet that was needed for her health: it’s all distressing, and as she describes it, the suffering replays in her mind.

But perhaps worst of all is not knowing when you will be released, how long the horror will continue: “Fear of not knowing what is going to happen. You can’t even answer that basic question.”

It started when, in a deliberately-used policy (“I don’t know if it’s designed purposely to break you”), she was taken to the Centre at 2 o’clock in the morning: “Your mind is confused. You’re bewildered. You’re terrified.

“You feel somebody locking the door behind you: it’s a terrifying concept. You feel captured.”

After the capture, “You wake up every morning, waiting for a word.”

You are supposed to be given a monthly report that reveals whether you will continue to be detained or whether you will be released: “For four months I didn’t get that report.”

Your anxiety mounts. It starts to play with your mind.

The custody officers were intimidating, unsympathetic: “They’d make remarks like ‘Where are we deporting you to?”

In more than nine months of detention, she says she attempted suicide four times and ended up in hospital.

“Hopeless” is the word she uses to describe what it is to be locked up. ”It’s daunting. There were times when I thought, Surely this is not how my life was meant to be.”

Other detainees tried to help, “telling me ‘It’s not the end. One day we’ll be out of here’. But you can’t imagine the ‘one day’. It’s a perpetual life of uncertainty. You can’t even plan for a week ahead, let alone a month or a year. All you can do is make a little plan for the next hour.

“It’s cruel.”

But this is Stella Shyanguya. Despite the hardships, the hopelessness, the cruelty of the system, she emerged as a fierce advocate, helping others fight their cases even while detained. Her story has been described as “a David-andGoliath tale of survival, solidarity, and the human dignity at stake in the government’s new immigration strategy.”

How did she do it?

First, “You adopt a thick skin. Then “I made the library my friend. I read every legal book on detention, immigration law and every book geared to education.”

She quickly earned the trust of the other detainees: “The sense of other ladies depending on me gave me purpose. I aligned myself with helping people get out of detention.”

Organisations monitoring detention reckong she helped at least 60 women with their cases.

Finally, she herself went to court and won her appeal. But even when the court ordered her release “they left me for another five days.and then I was given bail conditions. I couldn’t leave my home. I lived in Huddersfield but had to report in Leeds; I was not offered any transport and had to rely on a friend.”

She lost a lot of friends, because as she says, “It’s hard for people to distinguish prison from detention. When people see you’ve been in prison, regardless of what for, you become a pariah.”

Immigration detention is the practice of locking foreign nationals in detention centres while their immigration status is being resolved. It is an administrative process, not a criminal justice procedure.

The UK is the only country in Europe where there is no limit on how long people can be detained. Nearly 20,000 people entered immigration detention in UK in year ending September 2024.

More than 50 people died in Home Office accommodation, including detention centres, in 2024, up from 11 in 2023.

Immigration detention is a proven cause of significant mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Most people detained in immigration are, eventually, released, demonstrating the levels of unwarranted detentions taking place.

Detention left other marks, too.

“It still affects me day to day. I have missed so many milestones in my life [not only from detention but because of years of battling the Home Office]. I have got grandchildren I’ve not seen. She was unable to fly to Kenya for the funerals of a brother and her mother. “I’m allowed to study and work but I have not been given any travel documents so haven’t been able to leave the country for 20 years.”

Last year the Home Office accepted she had been wrongly detained and compensated her, “but no amount of money can replace all the things you’ve missed in life. You cannot put a price on taking away a chunk of somebody’s life.”

Nando Sigona

The UK’s migration debate has long been dominated by a binary narrative of legality versus illegality, a framework reinforced through media coverage, political rhetoric, and civil society discourse. A new report written by Dr Stefano Piemontese examining how irregularity features in the British public discourse on migration between 2019-2023 highlights how this dichotomy serves not only to justify restrictive policies but also to constrain possibilities for a more informed and humane discussion on migration governance.

The report from the I-CLAIM research project on irregular migration in Europe underscores the urgency of shifting the debate beyond the transactional justifications of economic contribution and humanitarian need towards a more nuanced understanding of migration as an inherent feature of human mobility and social life rooted in British society and history.

One of the most striking findings of the report is what the report terms the ‘media coverage paradox.’

Despite a media landscape that includes both conservative and centre-left outlets, much of the migration discourse aligns with the narratives of the right-leaning UK government narratives, particularly on the issue of irregular migration. Media reporting heavily relies on imagery of Channel crossings, which frames migration primarily as a border control issue.

This focus not only dehumaniSes migrants but also distorts public perception, making irregular migration appear as an external threat rather than a structural issue shaped by policy choices. As the report notes, “migration discourse in media and politics heavily relies on quantification, particularly concerning small boat crossings and asylum applications. This numeric framing creates a

spectacle of control while overshadowing the complexities of how migrants become irregular (e.g., visa overstays, bureaucratic obstacles).”

The political discourse, on the other hand, strategically constructs ‘illegal migrants’ as a counter-image to ‘legal’ and ‘skilled’ migrants. The creation of ministerial and administrative roles explicitly focused on countering illegal migration and the 2023 Illegal Migration Act have enabled the government to justify a broader set of restrictive policies affecting all migrants and often also racialised citizens. The report shows that this framework operates in both geopolitical and moral domains.

Geopolitically, irregular migration is framed as a sovereignty issue requiring strict enforcement measures. Morally, irregular migrants are positioned as undeserving, contrasted against ‘desirable’ legal migrants who contribute to the economy and society.

This rhetorical structure, left unchallenged by media and political narratives, sustains a system where migrants’ rights remain conditional upon their perceived utility or vulnerability. As the report states, “Political discourse strategically constructs ‘illegal migrants’ as a counter-image to ‘legal’ and ‘skilled’ migrants. This framing enables the government to justify restrictive migration policies for all.”

Civil society narratives, while offering counterpoints to restrictive policies, remain largely reactive and limited in scope. The report identifies a dual strategy among migrant rights organisations: advocating for irregular migrants through economic contributions or humanitarian concerns. While these arguments have some success in shifting public opinion, they ultimately reinforce a state-centred neoliberal logic of ‘deservingness’—one that privileges certain categories of migrants over others. The ‘economic contribution’ argument, for example, has been instrumental in advancing discussions about regularisation initiatives, but it risks creating a hierarchy of deservingness based on

productivity rather than rights. Similarly, humanitarian narratives, while essential, often reinforce a victimhood paradigm that limits broader discussions on migrant agency and inclusion.

The report calls for a more transformative approach—one that reframes migration through an ‘unapologetic lens,’ one that recognizes human mobility as a historical and natural phenomenon rather than a crisis to be managed. In practical terms, this would mean shifting advocacy efforts away from transactional justifications and towards arguments that acknowledge migrants as integral members of society. For instance, labour rights discourse could serve as a powerful alternative to migration-centric narratives, focusing on protections for all workers regardless of status rather than reinforcing the distinction between ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ migrants.

The findings of the I-CLAIM report make it clear that current migration discourse does more than reflect political realities—it actively constructs them. The challenge ahead is to reimagine migration governance in a way that moves beyond punitive frameworks and towards policies that recognise the fundamental rights and contributions of all migrants, regardless of status. This requires not only a shift in media and political rhetoric but also a strategic recalibration in how civil society engages with the public debate. Only then can we create a more just and sustainable approach to migration—one that is not dictated by fear and exclusion, but by an understanding of mobility as a fundamental aspect of human society.

Nando Sigona is professor of International Migration and Forced Displacement at the University of Birmingham and Scientific Coordinator for Improving the living and working conditions of irregularised migrant households in Europe (I-CLAIM), a study funded under the Horizon Europe programme.

A Pakistani migrant has used flower power to overcome loneliness - and to brighten up her Birmingham neighbourhood.

“No flower grew in my area,” when Mah Jabeen Bano arrived in the city in 2003. Now, she’s winning horticultural and community awards.

Her first years here were achingly lonely. She felt isolated because of her lack of confidence in speaking English. She was fearful of travelling alone, having never done so in Pakistan. But she enrolled in an English class, then in several arts groups and when her two children were born she talked to mums on the school run.

Her confidence increased. And when she thought about the drabness of the area where she lived, she began to consider how she could spice up the public spaces around her. The answer was flowers.

“I wanted to do something for everybody in the community,” she says. “You cannot go wrong with flowers.

“I feel that flowers bring smiles to people’s faces. I saw flowers in other areas, and thought, ‘Why don’t we have them?’”

She started with her own front garden, hoping that if she set an example, others would follow and brighten up their front gardens.

Slowly, her initiative has grown, she has broadened her sights and, with two other women, set up Khawateen (Womankind) Creative Minds, a community organisation that specialises in recycled materials.

Khawateen’s first artwork was, fittingly, The Flower Queen, a lavishly garlanded woman’s face. Its first public

work, Rainbow Peacock, an equally colourful life-size creation made of paper, plastic and cloth, went on display at the Blakesley Hall Museum.

Even Covid-19 could not stop her: Bano started running classes online.

She joined others in creating the Hay Mills Art Trail, designed to bring the community together “and make our living space more welcoming through the creation of public

‘Don’t wait for someone to bring you flowers’

artworks co-designed by residents and businesses.”

Making the trail drew widespread community involvement. The local Acock Green Men’s shed group made the painted wooden planters. Flowers were donated by Acocks Green Village in Bloom. Khawateen volunteers took on painting and planting. A burst of vibrant colour lit up the high street.

Voluntary labour and donations remain at the heart of the work (“We rely on community support with people willing to use their time to beautify their communities — everyone brings one thing or another”), but Bano and the group also learned how to apply for funds. Khawateen used a £1,000 National Lottery grant to finance an indoor beautification scheme that saw it donating free seed packets to residents

to plant in their homes.

Khawateen received a certificate of commendation from the Heart of England in Bloom, a campaign that encourages local communities to care for their environment. Every subsequent year the campaign has recognised Khawateen’s activities.

A supermarket donated compost, flowers and hanging baskets to support Khawateen’s work. The Royal Horticultural Society made a grant from a programme supporting community groups who use gardening to increase social connections. In 2023 Khawateen was part of a River Cole restoration project that included the transformation of public spaces in derelict areas of east Birmingham.

Flowers really have changed Bano’s life, and that of scores of neighbouring residents.

Reflecting on her two decades in the UK, Bano, now 44, recalls, “With time, I became very confident, a peopleperson. Because my background is coming from another country, I understand the problems that other women can face, and I tell them that as a new person in this country, don’t wait for anyone to come and save you; get out of your house, get involved, learn the culture, learn how the country works for Muslim Asian women, go to art classes, learn painting, gardening … these are the ways I try to guide them.”

And she advises: “Don’t wait for someone to bring you flowers. Plant your own garden.

“Don’t wait for anyone to rescue you, you are the only one who can rescue yourself. Trust yourself.”

One of Migrant Voice’s top targets for 2025 is to see government action to take the estimated 745,000 undocumented workers out of the untaxed, unregulated economy and regularise their immigration status.

“This government needs to focus on what will benefit the country as a whole instead of playing with voters’ minds, using the issue of undocumented migrants,” one undocumented worker told Migrant Voice.

That worker, like hundreds of thousands of others, is not undocumented by choice: he wants a proper job, free from exploitation, to support himself and contribute to the country’s economy.

People are often undocumented through no fault of their own. Causes include the fall-out from policy changes, errors in paperwork, large increases in visa fees, spurious denial of asylum claims,and official confusion in dealing with modern slavery.

The problem has been growing, and last September more than 80 non-government organisations signed up to a Migrant Voice initiative to demand government action.

In an open letter to Home Office minister Yvette Cooper they said that being undocumented puts people at “increased risk of exploitation, and of mental and physical stress.”

These problems could be changed with a policy of regularisation, which the signatories said would also increase tax revenues for the government, increase the formal labour force and help create more cohesive communities.

A few weeks after publication of the letter, the Spanish government announced plans to regularise the status of approximately 300,000 people, which would “serve to combat mafias, fraud and the violation of rights.”

Nazek Ramadan, the director of Migrant Voice, has said: “Rather than penalising people for becoming

undocumented, this government must take a new approach and create simpler routes for them to regain a documented status.

“It is time for the UK to stop looking at people as statistics on a spreadsheet and start looking at them as human beings.”

X’s story is one of thousands, but each one sheds light on a system that has trapped people in limbo, forcing them into lives of uncertainty, poverty and fear. Fearful of further complications from the Home Office and the police, he spoke on condition of anonymity.

“I came here as a student in December 2009,” he explains, his voice heavy with the weight of years spent navigating the murky waters of an immigration system that has rendered him invisible. “I remember the date because so many people have asked me, maybe 100 times, in many places.”

He arrived in the UK with a bright future. Enrolled at a London college, he was pursuing a master’s degree, “but after just five or six months, the Home Office revoked my college’s licence, and that was it. Everything fell apart.”

With his college shut down and his visa linked to his studies, he was left in a precarious position.

“They told me if I wanted to continue, I’d have to enrol in another college and pay all the fees again. But I had no money. I’d already paid my tuition once and was surviving on a loan and money borrowed from a friend.”

The friend eventually moved to Portugal, leaving X with a £2,000 debt and nowhere to turn.

“I was homeless. I stopped going to college because I couldn’t afford it. I told my parents I needed to repay the loan, and they managed to scrape together some money, but nothing changed.”

He drifted between friends’ houses, restaurants, anywhere that would give him a roof over his head for a night: “When you have no status, people take advantage of you. They don’t want to pay you for work, and they abuse you because they know you have no power to complain.”

For years, he survived in the shadows.

X’s story took a new turn in 2019 when he was living with a friend who owned a pub. He helped out around the place, answering phones and occasionally serving drinks.

“I felt so good during that time. It was the first time in years I felt like a normal person,” he recalls.

It didn’t last. The Home Office raided the pub: “I was behind the bar helping the staff. They surrounded the place — there was no chance to flee. They found two other guys in the garden and came for me.”

He was taken to a police station, terrified about what would happen next.

“I was scared out of my mind. I didn’t know what was going to happen, but I told them everything. I had no support, no family, no money.” Escorted to a detention

‘I have potential but they won’t let me use it’

centre overnight, he was interviewed by the Home Office the next morning.

Subsequently he found himself homeless once again, this time under a bridge in London, surviving on food from a local food bank: “It was winter. Cold. Terrible. They wouldn’t even let me sleep in the doorways. All they gave me was a sleeping bag.”

He spent nights riding the bus just to stay warm. “The driver asked me, ‘Why are you always on the bus?’ I told him, ‘I have no place.’ He said, ‘It’s not my problem.’ That’s what it’s like — nobody cares. You’re invisible.”

The system, as he puts it, is “killing” him. “I’ve been through so many nights, so much cold, so much hunger. The system takes everything from you. It breaks your spirit.”

Occasionally he has found temporary accommodation with a charity, but it was always fleeting. “They give you a bed for a few nights, but it’s never permanent. You’re always waiting for someone to tell you to leave.”

His mental health was affected, and his situation became increasingly dire: “I can’t sleep at night. I must take medicine. My brain is deteriorating because I haven’t been able to work. When I talk too much, I become dizzy.”

Today he still lives in limbo: “I could have done something for this country. I could have worked and contributed. But they’ve kept me in this prison. I have potential and education, but they won’t let me use it.”

His story is not unique. Thousands of undocumented workers like him are trapped in the UK, unable to work, unable to return home, unable to build a future.

“I’ve been in this country for nearly 15 years,” he says, his voice breaking. “I don’t know what I’m going to do for the next 15.”

He remains hopeful, but barely: “I’m isolated. I don’t talk to anyone. My father has died, and my mother is under stress back home. I’ve lost so much time.”

He waits, still checking in regularly with the Home Office. “Every time I am due to report I get a kind of flashback at night and I wake up suddenly, worried about missing the appointment. When I go I fear I might be detained — it’s so horrendous. They check my papers, five seconds, that’s it. They say nothing. They’re sadists. They enjoy watching us suffer.

“When they started digital reporting as well, I asked at the counter ‘Why am I doing double reporting?’ They just replied, “You have to.”

X’s story highlights a harsh reality: the UK’s immigration system is failing those who have slipped through the cracks. For many, it has turned into a nightmare of survival, exploitation, and despair.

“But I still have a little bit of hope left,” he adds. “Maybe, one day, they’ll let me live.”

Immigration in the UK has gone through seismic shifts in the last two decades, says Madeleine Sumption, director of the Oxford Migration Observatory, as she explains how Brexit and global trends have reshaped the country’s immigration patterns.

“For decades, non-EU migration was the main source of immigration to the UK,” she says. “Things started changing around 2004 when the EU expanded. By the 2010s, EU migration had overtaken non-EU migration.”

The tide turned again after Brexit, with non-EU immigration surging back to prominence.

As a result, Poland has been replaced by India as the top source country for migrants to the UK, “particularly in sectors like health care and higher education.”

However, Sumption stresses that migration statistics from the early 2000s are not always reliable.

“We don’t have perfect data from that time,” she acknowledges. “Non-EU migration may have been the majority even back then, but it’s clearer in the data from 2010 onwards.”

Sumption notes that while Brexit policies have significantly impacted EU migration, the shift from EU to non-EU migration began before the referendum because of “exchange rates, economic changes, and geopolitical factors.”

After Britain voted No in a referendum on whether to

stay in or quit the European Union, she points out, “several things happened at once.

“Free movement for EU migrants ended, which significantly reduced the flow of EU migrants to the UK,” she says. “On the other hand, there was a liberalisation of policies towards non-EU migrants, particularly for international students and care workers.”

The introduction of the “graduate route,” allowing international students to stay and work in the UK after completing their studies, had contributed to the growth in numbers.

‘The impacts are smaller than people think’

At the same time, UK universities were aggressively recruiting overseas students, especially after Covid-19, to make up for their own financial shortfalls: “We ended our lockdowns sooner than some competitor countries, like Australia, which made the UK more attractive.”

There was concern about care sector staff shortages “so the government opened up its care visa — and … Zimbabwe became a major source country.” There was also quite a lot

of abuse, she adds, with a considerable number of workers being exploited: “It was not a well-managed process.”

The third group of migrants consisted of Ukrainians (granted 200,000 visas) and HongKongers (particularly in 2021 and 2022), “though the biggest drivers of immigration are still workers and students, rather than those who came on humanitarian routes.” People seeking asylum account for about 10 per cent of migrants.

How long migrants stay “depends heavily on the type of visa they come in on,” says Sumption. “Refugees and family members tend to stay permanently, while workers and students often leave after their visas expire. We expect that more health and care workers are staying permanently now, though.”

British emigration also has an impact on the overall migration figures: “Between 30,000 and 80,000 Brits emigrate each year, which lowers the net migration figures. Without that outflow, the numbers would be even higher.”

Sumption anticipates a slight decrease in the number of migrants, but probably not to pre-Brexit levels of 250,000 to 350,000 a year. “We’ve already seen a decline in work and study visas. However, the numbers are still likely to remain higher than pre-Brexit levels, especially in sectors like health and care.”

She also points to the influence of non-immigration policies. “The care sector, for example, struggles to recruit workers because of poor pay and conditions. That’s a policy issue in a publicly funded sector, leading to higher demand for migrant workers.”

Overall, Sumption emphasises that while Brexit and global events such as the war in Ukraine have re-shaped UK immigration patterns, migration remains a complex, evolving issue: “Non-EU migration has taken centre stage again, and the UK’s immigration landscape is now influenced by a mix of policy changes, economic needs, and global dynamics.”

She foresees that migration will continue to be a hot topic for years: “It’s an issue that affects every part of society, and we’re likely to see further shifts as new policies and global events unfold.”

+ Sumption on the national debate on migration: “Media coverage can be quite polarised. Often we see debates in which one side says immigration is bringing down the economy and the other says immigration is keeping the economy alive. The reality is more boring: that migration has costs and benefits, and the impacts are smaller than people think.

“There are countries, like Japan, with much lower levels of migration and they do fine, and countries like Australia that have much higher levels of migration and they do fine, too.

“It’s often not the determining factor, at least from an economic perspective.”

The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford provides independent, authoritative, evidence-based analysis of data on migration and migrants in the UK, to inform media, public and policy debates, and to generate high quality research on international migration and public policy issues.

London has the largest proportion of migrants among UK regions, with over 40 per cent of its residents born abroad

Compared to people born in the UK, migrants are more likely to be of working age and have a university degree

Source: Migration Observatory

Exhibition photos: Karen Gordon

Migrants have really put themselves in the picture in Scotland: an exhibition of photographs by and about migrants at a Glasgow museum has attracted more than an estimated 150,000 visitors.

The 60 portraits at the Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery are vivid proof of the many ways that migrants contribute to Scottish life.

They also help ensure that migrant heritage is documented and recognised as part of Scotland’s past and present.

Migration is not a one-way movement: a previous government estimated the worldwide Scottish diaspora (emigrants and their descendants) at between 28 and 40 million.

Sir Geoff Palmer, the first black professor in Scotland, who is featured in the exhibition, has pointed out that “three-quarters of the surnames in the Jamaican telephone book are Scottish, so many Jamaicans have some Scottish blood or history in them, whether they like it or not.

“So as I tell many Scots, your ancestors were not in Jamaica doing missionary service alone!”

At the opening of the Kelvingrove show he also pointed out that a Jamaica Street has existed in Glasgow since 1763: “So when we talk about “our city”, [if] we look back far

enough, a lot of people have contributed.”