MIDDLEBURY GEOGRAPHIC

EDITOR’S NOTE

Dear Reader,

More than just a publication, Middlebury Geographic is a sanctuary for us, editors and contributors alike. We are called back each semester to create this magazine, fueled by the belief that storytelling still matters—that listening closely and sharing generously can be small acts of resistance in a world that too often favors disconnection. It is a fundamental joy to create something tangible as our lives are increasingly online; to weave together images, written experiences, and each contributor’s unique perspective on landscapes into something bigger than ourselves.

To print is to take up space in the world—it’s an act of slowing down, of choosing permanence in an age of constant motion—to honor the connections we make to the places we vibrantly seek. We hope this issue serves as both an invitation and as a call back to the physical world—a world that is deeply connected. Whether we comprehend it or not, we all yearn for a connection to the very place and stories that sustain us—to feel the soil beneath our feet and wind brush past our skin and importantly to share those experiences with those around us.

This issue embodies the innate desire to be connected to a place through knowledge earned by doing and being. We see this in Chile, as Will wrestles with the sense of awe that a stunning landscape brings, through Kaia’s intimate conversations with the land in Peru, and as Lilly reflects on the lessons the soil in New York has to offer. This edition (the 25th!) of Middlebury Geographic explores what it means to return home, to foster a connection to a place, and to allow yourself to soak in a landscape—even if it’s just for a mere moment.

Many thanks to you, our readers, who make printing our magazine so rewarding. We hope you enjoy this fall’s issue—we selfishly think it’s one of our best yet.

With gratitude, Lucas Nerbonne ‘25.5 & Eliza Tiles ‘27.5 Editors in Chief

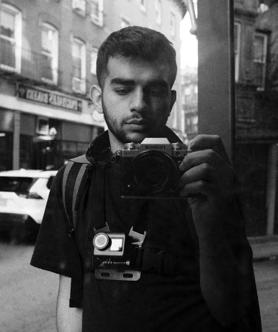

Mattias Herrera ‘29

MIDDLEBURY GEOGRAPHIC

Lucas Nerbonne ‘25.5

CONTRIBUTORS

KAIA GANZELL ‘28

Kaia is a sophomore from Maine who studies Environmental Policy, Global Health, and Spanish. She is especially interested in how environmental degradation shapes public health outcomes. Outside of school, Kaia loves rock climbing, backpacking, traveling, and playing ultimate frisbee.

YAHYA RAHHAWI ‘26

Yahya is a documentary and street photographer from Mosul, Iraq. Through his lens, he captures the resilience, beauty, and complexity of life in the cities he visits. He is drawn to fleeting moments—glimpses of emotion, movement, and light that tell passing stories within the everyday.

REBECCA DORIAN ‘26

Rebecca is a senior from Atlanta, Georgia. She is a philosophy major interested in questions of moral responsibility and determinism. She loves singing with her acapella group, working with kids, and doodling in her journal.

NOWELLE SPENCER ‘26

Nowelle is a senior biology major from Anchorage, AK. When not at school, she spends her free time attempting to convert a school bus into a tiny home (only somewhat successfully), running around the mountains, and trying to paraglide without dying. She loves skinny dipping in half-frozen alpine lakes and is happiest when she’s tidal pooling or doodling.

GERRIT BLAUVELT ‘27

Gerrit is a junior from Bellows Falls, Vermont. He’s majoring in Physics, and spends the rest of his time on campus learning lights and sound in the Theatre department. He has carried a camera with him everywhere since fourth grade, and takes any opportunity he can to ride a train.

LUCAS NERBONNE ‘25.5

Lucas is a super senior feb from the flatlands of Minneapolis, MN. As a geology major, Lucas loves rocks, places that have rocks, and taking rocks home with him. Outside the classroom you can find Lucas in the pottery studio, taking photos, or on top of a mountain.

LILLY CLECHENKO ‘28

Lilly is a Sophomore from Houston, TX, majoring in Earth and Climate Sciences. When she’s not on the 4th floor of BiHall and around Vermont looking at rocks, she enjoys hiking, especially in the Adirondacks, playing her guitar, and film photography.

LIAM REYNOLDS ‘26

Liam is a senior from Western Massachusetts. He loves rocks, maps, and the smells of fresh cut hay and cow manure. He hates writing, the Yankees, and the New England Patriots. When not playing frisbee, or biking, or skiing, he dabbles in film photography and beer.

DYLAN MEYER ‘28

Dylan is a sophomore from Miami, Florida. He is an Environmental Studies major and is considering minors in English and Political Science as well. Dylan works as a hiking guide in the summer at a sleepaway camp in Colorado. If Dylan could be one animal, he would be a grizzly bear.

CASPER WILSON ‘28

Casper is a sophomore from Marin County, CA. Joint majoring in Biology and Earth and Climate Science, he hopes to explore the interplay between ocean acidification and aquaculture. He loves spending time in nature and enjoying views of Lake Dunmore from a rowing shell.

EVE SARTI ‘29

Eve is a first-year student from Marin County, California, hoping to study Earth and Climate sciences and Biology. She spent the past year exploring Patagonia, Southern Africa, Mongolia, and Scandinavia. When she’s not grocery shopping, she loves baking, mountaineering, planning outdoor adventures, and sharing it all through videography and photography.

LUCAS BASHAM ‘28

Lucas was born and raised in Brooklyn, NY, and is an International Politics and Economics major. He lived in Spain during his junior year of high school but speaks fluent Spanish with an Argentine accent he got from his mom. He loves sweet treats, snow, sunsets, and Christmas, but especially all of them at the same time.

WILL HINKLE ‘26

Will is a senior with passions for education and exploration. His love for the outdoors and meeting people inspires his interest in environmental communication as a means of working with others to address environmental issues and to foster a voice for nature. Will is an energetic leader who brings these passions into spaces like YMCA Camp Woodstock, political organizing, and the Middlebury Mountain Club.

Erin Pomfret ‘28

GEOGRAPHY OF THIS ISSUE

Cartography by Lucas Nerbonne ‘25.5

Celia Geci ‘27

In Conversation with the Earth

Kaia Ganzell ‘28

Smooth rocks lined the shore of the winding river where I stood, gazing up at the Apus—the 17,000-foot mountain who seemed to look back down on me. Wanka had sent me here to collect stones for repairing the house, so, for a while, it was just me, the water, the rocks, and the mountain—each of us sharing quiet company with the other. I set down the sack I had brought with me and turned to speak with the river.

Antuarku, an Incan spiritual master from the Chawpin Quechua Community in Peru, and my WWOOFing (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms) host, had given me instructions to ask the river for her stones. It was my responsibility to seek permission before taking something from the place where the Earth put it, and my obligation to listen for an answer. The stones weren’t just mine for the taking.

So I listened. The air was cool, with a soft breeze brushing against my skin as it drifted past. It smelled fresh, clean, untouched. Sunlight glistened on the water as it swam past, rushing through the plains on its way down the mountain. I heard Blanco and Ampy, two of the farm dogs, barking in the distance. I’m still not entirely sure how I received an answer to my question. It was more of a feeling—subtle but certain—of consent and appreciation. The longer I stood there, the less it felt like I was asking permission and the more

it felt like I was being welcomed. I thought about how rarely I stop to ask before taking, and how much better it felt to be still enough to listen first. I knelt to pick up stones, understanding the Earth around me in ways I hadn’t even a few minutes ago.

On the surface, to spend time in the high plains, or the Puna (as they’re called in Quechua) is to forgo the comforts of daily life: clean clothes, grocery stores, cell service, and comfortable beds.

But the trade is for a deeper connection to the natural world. I learned how to listen—to the birds chirping and dogs barking, the unhurried evening winds, the hum of the llamas, and, even more notably, the soft sound of silence that encompassed the plains. Listening became a process of learning. I became more in tune with myself, with the freedom I felt in the environment, and the unpredictable nature of the world around me.

It wasn’t just the river that I spoke to. During these weeks in the high plains of Peru, my sister and I were immersed in Inkan ancestral teachings and traditions that illustrate the intrinsic connection between humankind and Pachamama, our Mother Earth. Inti Nan’i Yachay Wasi (the farm and its project) exists in harmony with these ancestral Andean traditions and aims to share this deep connection with others, preserving and sharing their culture.

We began each day with the llamas. In an ongoing effort to retame them, we were instructed to catch them and hug them (or, as we liked to call it, rather, llama wrestling). We then let them out for the day as a free-ranging herd, allowing them to move and graze freely throughout the plains. With a shared commitment and appreciation, we would then water the plants and cook a communal breakfast. Filling the water buckets in the stream and hauling them to the green-

houses may have felt like a monotonous chore, but doing so while experiencing the presence of the Apus above me, the ground beneath my feet and the others around me became uniquely comfortable.

After filling our buckets each morning, we would gather in a circle to make k’intu—small bundles of four coca leaves offered to Pachamama and the Apus in gratitude and connection. One by one, we created offerings for ourselves and for each person beside us, pressing into each leaf our intentions and our hopes for one another. This process quickly transformed us from a group of strangers traveling from across the globe into a unified group, existing in harmony with one another and together with the natural world around us. Beginning our days with these offerings and shared graciousness wove a quiet connection between us, creating meaning and comfort within our daily work.

On our rest day, we hiked up into the mountains that had been watching over us for our first few days there. Six WWOOFing volunteers, Wanka, Illa Wari (Antuarku’s son), the three dogs, and two horses set out on the journey. Usually, I hike fast, pausing occasionally to take in my surroundings, with a greater focus on the destination than the journey itself. This hike was entirely different.

We made three lengthy stops on the trek up the first

to ask for a safe passage, offering a k’intu to the mountain herself, and leaving the coca leaves carefully tucked into a crevice of the great sacred rock whose shadow shielded us from the powerful sun. Our second stop was an offering at a historic spiritual site from the 1500s, where we introduced ourselves to the mountain, and recognized our own intentions on this journey, and how those intentions are inherently connected to the very mountain and her spirit that we were speaking to. The final offering was to the Apus, a vibrant and beautiful mandala of grains, flowers, and fruit that we each contributed to with quiet sincerity, placing the individual pieces with such genuine thought and intention.

“The focus wasn’t on yield, but on reciprocity.”

Hiking in the United States so often feels transactional—paying for parking passes and entrance fees, hurrying to claim a spot near the trailhead, weaving through crowds eager to capture the summit in a photo. It becomes easy to neglect the tiny wildflowers, the scurrying insects, the soil beneath your feet. Walking up the mountain in the Puna was the opposite: slow, intentional, reverent. Taking my time

to introduce myself to the mountain, to create time for rest, and take in my surroundings in these new ways opened up a deeper kind of appreciation for the grandness and beauty that encompassed us.

Ideas of land appreciation revealed themselves most vividly through the farming practices of the Puna. While we grew some vegetables, the primary agricultural project was a tree reforestation effort with native high-plain saplings. Like the hike, the rhythm of farm work here felt entirely unlike anything I’d experienced in the United States. Having worked in a vegetable garden the previous summer, I was used to measuring success in quantifiable terms: the number of beds weeded, pounds of produce harvested, visible progress at the end of the day. But here, in the Puna, the rhythm of work was slower, more intentional. We dug purposeful trenches for the young trees, pausing before breaking the ground and learning from the Earth as we dug. Progress wasn’t something to tally, and we weren’t planting for economic gain. The focus wasn’t on yield, but on reciprocity.

Every stone I took from the riverbed, every sapling I watered, every breath I shared with the mountain was a quiet reminder that we are not separate from nature—we are a part of her endless rhythm.

Into the Weeds with Mike Quinn

Rebecca Dorian ‘26 & Yahya Rahhawi ‘26

Iwedged my feet between a toolbox to keep from falling out the back of Mike Quinn’s red flatbed truck as he drove us to the highest point on his farm. Shouting from the driver’s seat, Quinn’s words were barely audible over the sound of the engine, and I felt sorry to miss anything he had to say. I originally sought out Quinn because I was interested in speaking with local hunters. Growing up outside of Atlanta, my dad hunted most of the meat my family ate—quail with a shotgun, and deer, turkey, and elk with a compound bow. Weekend mornings were spent with my sister practicing our archery skills in the backyard, and we would occasionally drive outside of the city to shoot clays. I felt strange bringing my elk jerky to school, and embarrassed when friends would come over and see our taxidermy lined walls. While I don’t personally hunt, I feel pride in this aspect of my upbringing, and wanted to explore the hunting culture in Addison County. After asking around about local hunters, my friend and passionate photographer Yahya and I drove 15 minutes off campus to Quinn’s farm. We would end up engaging in what would become a conversation about so much more than hunting.

Quinn grew up in Hinesburg, Vermont in the ’60s, a childhood he refers to as “pretty much continuous hunting, fishing and trapping.” Now 70 years old, Quinn sports a long white beard, and his bright blue eyes shine from beneath his

Mike Quinn

worn cap. He moved to the Middlebury area in 1979, where he runs his small farm and sawmill, “Mikey’s Mill.” He spends his time tending to his roughly 30 sheep, which graze brush until he eventually processes them for meat. Before raising sheep, Quinn sold hay, but he got out of that about two years ago when prices collapsed during the nationwide agricultural depression. Prior to that he shipped milk—that is, up until 2020 when he sold his last replacement heifers.

Aside from life on the farm, Quinn is an agile musician who is skilled in both the banjo and concertina. His band, which includes Middlebury College professors, is one of the many ways he is involved in the Middlebury community.

Quinn describes himself as a firm believer in hunting, which he argues is “just one step away from farming, which is more managed wildlife.” He sold the exclusive hunting rights of his land to the Warner family, friends and neighbors of his. The Warners hunt all kinds of game with a variety of tactics, from bow and arrow to muzzle loading rifles. Quinn is passionate about allowing the Warners’ now roughly 40-year stewardship of his land continue until he “drops dead.”

Quinn’s preferred hunting practice is small game— partridge, squirrel, duck. He told us, “If I went out hunting, I wanted to come back with something.” While hunting used

to be more of a food source for Quinn, he now does it for animal control, which he explains is “a necessity in an agricultural community.” Recent medical operations have limited his mobility, but he still keeps his .22-caliber shotgun propped against the wall by the front door, ready to shoot possums, skunks, and coons from the front porch.

The relationship Quinn describes with hunting on his land is one of true stewardship. He hunts what is needed to protect his crops and maintain the health of his farm, while ensuring that the land continues to provide for others. Those who are estranged from agricultural communities often view hunting as an evil act, but Quinn instead holds the view that killing is a part of his responsibility to effectively care for the land. He also remarks that his instinct for hunting goes beyond just wildlife management, connecting it to a predatory instinct. He compared the feeling he gets before a successful shot to knowing he has a winning raffle ticket. “The feeling I had knowing I was gonna win is the same feeling I have when I know I’m about to flush, take aim, fire, and be successful […] I recognize that [predator] feeling.” My dad has expressed a similar sentiment, claiming that he knows if a shot will kill the animal the second he releases the arrow. The act of hunting seems to intimately connect the hunter to their prey, creating a true connection to and appreciation

for one’s food. Personally, when I know exactly where my food comes from, I am much more appreciative and less likely to waste it. To be so closely engaged with the meat which we consume, feels to me like the ultimate form of respect towards the animals which nourish us.

A main theme of our conversation was division: between the college and the locals, farmers and city folk, liberals and conservatives, and so on. Quinn expressed frustration towards the way he feels that mainstream liberal culture views hunting and farming.

In the media, these pursuits have often been depicted as the lifestyle of an uneducated, backwards-thinking, rural population. This stereotype may be partially kept alive by a failure from urban populations to actually interact with hunters and farmers to build their own opinions. When discussing Addison County specifically, Quinn remarks, “It’s like there’s two different populations that don’t know one another.” He continues, “People are not aware [...] they didn’t even grow up going home to grandpa’s farm. So they just plain don’t know anything about it […] this is how Trump got elected.” Quinn leans forward, his shift in tone hinting at frustration. “[Farmers are] treated like a minority, by an uneducated urban majority, with excessive regulations and so forth. That resentment is what caused Trump, which was a very, very bad thing. I mean, it just so happens that all of us agree with that.”

“It’s like there’s two different populations that don’t know one another.”

The sense of disconnection that Quinn so eloquently touches on speaks to a greater cultural divide between people whose lives are tied to the land and those whose aren’t. A key takeaway from the conversation that Yahya and I had with Quinn is that bridging these gaps requires genuine curiosity and conversation between people with different experiences. Engaging with local farmers like Quinn, and spending time off campus, can help dissolve those barriers in the Middlebury community. It is through those kinds of exchanges that people can begin to replace the kind of schism that Quinn so aptly describes.

Quinn’s stories often take exciting twists and turns, a characteristic he describes as “[going] off into the weeds.” One of Yahya’s and my favorite tales began with him catching a skunk in a coyote

trap. “If you’ll cooperate, I’ll let you out of that trap” he recalls saying to the skunk. “But otherwise, I’m gonna beat the heck out and kill you.” He describes creeping close to the skunk, trying to soothe it—“take it easy, skunky, take it easy.” It’s then that Quinn drops his funniest line of the afternoon, “every book will explain that the skunk has to have all four feet on the ground to spray […] well, this skunk hadn’t read that.” He pauses for laughter before finishing the story: “and, of course, when I open the trap, he rolls out of it […] I see this skunk rolling in slow motion, and a stream of yellowish stuff ends up hitting me, right? And then, oh, my God […] I went to the nearest puddle […] I was very disappointed with his manners. […] so the worst thing I can call anybody would be an ungrateful skunk.”

For Quinn, storytelling is more than entertainment, but a way of connecting. Through his stories, he invites others into his rich and colorful world. Sitting in his kitchen, laughing and comfortably switching between conversations of farming, politics, childhood memories, and everything in between, it was easy to see how simple conversation can bridge differences between people who might otherwise have little in common. In a place like Addison County, where divides between locals and college students can feel stark, Quinn’s stories remind me that conversation, especially when it wanders into the weeds, is sometimes the most powerful tool we have for crossing those divides. I entered his house nervous about how I may be perceived, if I would ask the right questions, if I was intruding. By the time we left, I felt joyful and assured. Even my face was sore from smiling and laughing all afternoon.

Spencer ‘26

THUNDER DRAGON scenes from the land of the

Nowelle

Cheri Monastery, located just north of Thimpu, the capital of Bhutan

Icouldsit here and summarize some facts about Bhutan—the place that so often earns a puzzled “where?” when I mention I studied abroad there. I could explain that it’s the only carbon negative country in the world—or that it values its environment and citizens’ happiness above economic growth. I could try to describe its culture, or its religion, or the policies surrounding the government and environment, but that’s not my story to tell.

I was a student in Bhutan for a mere six weeks, and my experience can’t begin to capture the country in its entirety. My words here are simply a glimpse at what Bhutan gave to me, rather than a definition of what Bhutan is.

Inside Cheri Monastery, built into the rocky landscape

Life was slow in Paro, Bhutan. I spent hours watching the fog roll over the mountains, sitting on a little green bench atop the hill that overlooked the valley of Paro. Between classes, I would lie in the courtyard of The Center, staring at the clouds, discussing with a friend whether one looked like a dragon or a flower. I drank copious amounts of gooseberry tea and got overly excited every time I saw fairy ferns. I learned to sit with my thoughts, with the only internet access being in the dining room and library, and spent hours walking clockwise around stupas, trying to decipher life’s dilemmas. My clothes took multiple days to dry due to the humidity, and I became accustomed to timing my hikes with the monsoons. However, in the midst of that quiet rhythm, it was the locals who left the deepest mark—what I truly walked away from Bhutan with was the wisdom from the locals I met.

As I attempted to hitchhike around Paro, people would stop and offer me help before I could even raise my thumb, often even rerouting their trips just to take me home. The chatty rides granted me small but vivid glimpses into their lives as we bounced down the rocky, unpaved roads.

Atop Mt Frawilkar, at 13,000 ft, I befriended a shepherd as we tried to outrun a thunderstorm. Through the cracks of thunder, we debated the potential dangers of the bears and snow leopards I might encounter on the rest of my adventure, and laughed at the ill-formed decision we both made that left us more than 10 miles from the trailhead surrounded by fog in the pouring rain.

While watching locals practice archery in Thimphu, my friends and I met an archer who immediately invited us to try his bow and arrow. Afterwards, he then led us behind the field into the dark, where he offered us momos from the back of his friend’s car. We sat, chatting about traditional Bhutanese archery practices and about our lives at home until the stars grew bright over the city, and the cold of the night began to creep in.

Farmer

tending to the rice paddies towards the beginning of the season in the valley of Paro

Looking down at Punakha Valley from atop Khamsum Yulley Namgyel Chorten, a Buddhist temple

Buddha Dordenma Statue, south of Thimpu

In the valley of Paro, I often spent hours in the town’s Gho and Kira shop, where the owner greeted me each time with a warm cup of milk tea. I’d wander through narrow aisles stacked floor to ceiling with vibrant fabrics, gradually getting to know the family and their cat, Tiger. Over time, those visits turned into real friendships, and soon we were swimming in the Paro Chhu and having dinner together at the local restaurant.

Though strangers at first, each of these individuals welcomed me into their lives through quiet acts of kindness— offering me a short ride, sharing a long conversation, or simply just showing care. As someone who often travels alone, it took me time to adjust. I’m used to keeping my guard up for safety when meeting new people. But in Bhutan, that instinct began to fade. I found that I could trust strangers. I could trust the people I met to be genuine and kindhearted. What defines Bhutah for me isn’t its policies or its carbon negative status, but the kindness of its people—the quiet, effortless generosity woven into their everyday lives. Their generosity left an impression deeper than any landscape or temple, one that I’ll carry with me long after my time there. Even now, I find myself longing to someday return to the sound of prayer flags fluttering in the Himalayan wind, and to give back, in some small way, to the country and people who gave so much to me.

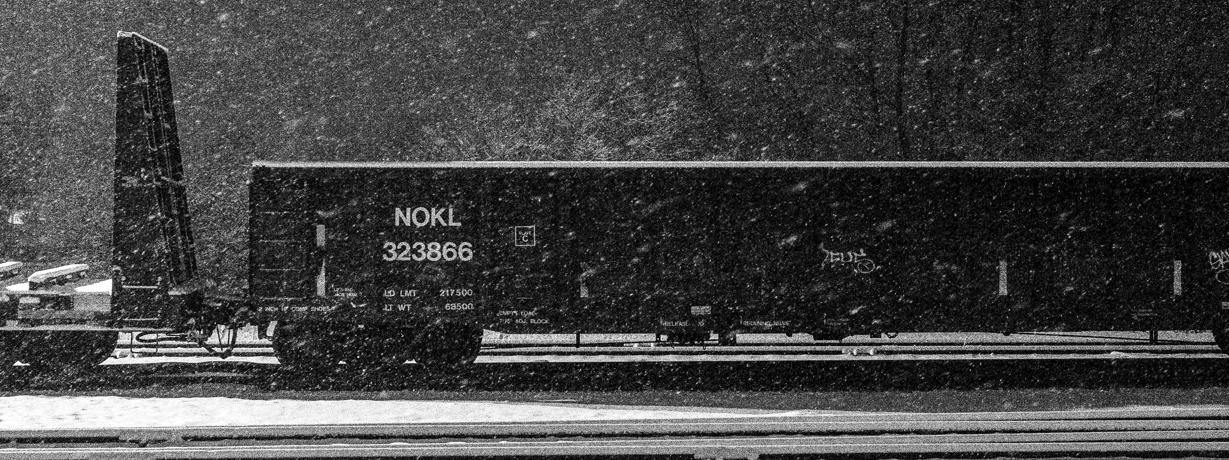

Boarding the train at Halifax, Westbound. 11:56 AST

48 HOURS ON A SLOW TRAIN IN CANADA

Gerrit Blauvelt ‘27

WhatNorth America lacks in reliable or frequent train services, it makes up for in long-distance options, offering beautiful scenery from coast to coast. A dense network of interurban rail certainly would be nice, but long train rides offer something I find rather special. On a long-distance train ride, most of the journey is far beyond urban development; cell service is sparse and the trains rarely have Wi-Fi. In a world that can be overwhelmingly busy and distracting, a long train ride holds no obligations but to sit down, look out the window, and eventually arrive somewhere new.

After a particularly stressful fall semester, my friend and I decided the proper way to wind down would be to take a train simply for the sake of taking a train. VIA Rail, Canada’s equivalent to Amtrak, operates two overnight trains: The Canadian, a three-day tourist-focused ride through the Canadian Rockies from Vancouver to Toronto on a fleet of retrofitted 1940s train cars, and our route of choice, The Ocean, a twenty-four-hour journey from Montreal to Halifax, on a 50/50 mix of the previously mentioned ’40s cars and surplus English cars from the ’90s. It’s not a tourist train, and the ride takes twice as long as driving would take, so it has a fairly niche market. The route winds its way up the St. Lawrence River past Quebec before coming down the coast of New Brunswick and terminating in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The conductor seats everyone based on destination; the week before Christmas, our coach of people riding all the way to Nova Scotia was full. Before we’d even pulled away from the platform at Montreal, the conductor came around asking who would want to smoke, and made sure to wake those of us who asked as each stop approached. The train makes three scheduled smoke stops, seemingly for the sake of the crew as much as the passengers. A select few of us would get off at these stops for fresh air and the opportunity to walk for a few minutes, but most would smoke.

We traveled on the solstice, so daylight was short lived. We left Montreal shortly after sunset, winding up alongside the St. Lawrence River as far as Mont-Joli, before cutting down to Matapédia and following a dozen miles inland from the eastern shore of New Brunswick. The lights of railroad crossings and a nearly full moon provided a steady glow through the night. Surrounded by falling snow and Canadian forests, each town felt like its own snowglobe.

As the ride went on, we got to know our neighbors—an older couple from Ontario visiting their daughters in Halifax, a girl living in Montreal

on a gap year returning home for Christmas, and another girl, doing just what we were, taking the train to Halifax for the sake of it. Neither of us had put any thought into what would happen when we got to Halifax, so the three of us ended up wandering in search of dinner together. She was slightly more sensibly spending a couple of days in the city, unlike our plan to immediately turn around the morning after we got in and get right back on the same train to Montreal.

In addition to the breakfasts, lunches, and dinners you’d expect over twenty-four-hours, we found ourselves frequenting the canteen car for any sort of miscellaneous snack we could use to justify the short walk. We were quickly welcomed as “regulars” by the attendant, who thought our trip was a bit silly on the whole but otherwise humored us. For twenty-four-hours, the train felt a lot like my small-town high school—everyone said hello to everyone, and we all knew the crew that was making our food.

Smoke stop at Campbellton, Eastbound. 08:43 AST

Departing Mont-Joli, Eastbound. 05:23 AST

The way east, sitting in the cars from the 40s, felt long and winding, with no music or entertainment beyond the window. In contrast, the way back to Montreal went by quickly. We barely talked, only taking breaks from listening to music and looking out the window on our frequent trips to the canteen car. With a timezone change on the way, the eastbound train leaves at 7 p.m., and arrives at 6 p.m. the next day. We had a full sunrise to sunset, but the westbound train leaves at 1 p.m. and arrives at 10 a.m. the next day, giving us just two partial days. As different as they were, both ways proved to be exactly what we needed after a long fall semester. With limited daylight and limited sleep, the four day trip felt more like just two days, in the best way. We had properly detached ourselves from the rest of the world, temporally and spatially.

Passing through rural Canada, with limited connection to the world at large, thinking only of scenes out the window or conversations with strangers, was a wonderful way to relax, reset, and clear our minds from a busy semester and a chaotic world. My experience felt, as British musician and photographer Graham Nash sang in Marrakesh Express, like “sweeping cobwebs from the edges of my mind.” We spent forty-eight hours on a train just to end up where we started, and returned all the better for it.

Smoke stop at Sainte Foy Station (Quebec City), Eastbound. 23:23 EST

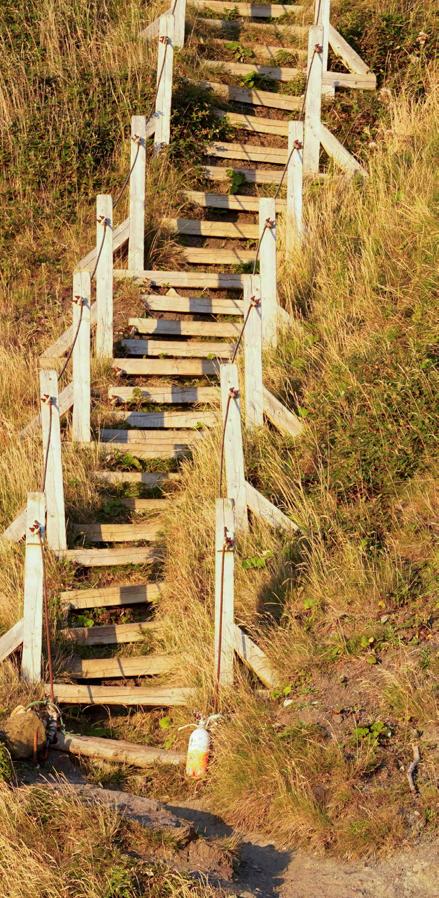

To Newfoundland with a Map

Lucas Nerbonne ‘25.5

We pulled into our campground as dusk was setting in, and I couldn’t help but think about having to dig headlamps out from the heaping pile of stuff in the back of the car. The site was perched on a ledge above the ocean, set back from the sand by a staircase and a few piles of driftwood. Sharing the expansive view with only one other campervan, we watched as the last light faded from the horizon, leaving only the glow from our camp stove illuminating the scene around us.

I first heard of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, years ago in an essay by Neil King titled Three Cheers for the Far, Far, Far Away. In it, King details his three-day drive up the coast of North America from Washington, DC to his summer home in Cape Breton, a peninsula perched at the end of the world on the very tip of Canada’s Nova Scotia Peninsula. The essay paints a rich picture of this remote island, which, in King’s words, is “swaddled by distance.” This distance, much like a rind of an orange, “protects the sweet fruit inside.” I pinned it on my Google Maps app, drawn to the idea of a place that embodied a wilder beauty than the overcrowded, overdeveloped landscapes of my childhood.

As I stood along the ocean on the eastern shore of Cape Breton Highlands National Park this past August, I started to understand what King meant. It was the last week of summer before the first day of classes of my final semester of college, and my friend Liam Reynolds and I had driven north to Canada’s Maritimes. These seldom-visited coastal provinces reach into the Atlantic to the north of Maine, playing host to long stretches of empty coastline, ancient forests, and a rich history of Scottish and French culture brought by some of the first New World settlers. After my own long drive from home in Minnesota back to Vermont, we drove out of town along Main Street, heading north. The drive to Cape Breton alone would take two full days. From there, our final destination, the island of Newfoundland, lay another five hours and a seven-hour ferry

ride farther along the coast. The spot King described as feeling like the “end of the world” would, for us, just be a stopover. We set off from Middlebury, Vermont, with only a pair of ferry tickets and not a single place booked to stay or any activity planned. The remote corners of Canada aren’t known for good cell reception. This unstructured journey resonated with Liam’s mom—she said it looked a lot like a trip she would’ve taken back in the 80s: just showing up and hoping you could

find someone who knew what they were talking about. With that lack of structure, the trip became a case study in curiosity—seeing where the road, the weather, or even a stranger’s suggestion might take us next. Could it be possible, in the age of online campsite booking lotteries and Alltrails routes, to still go on a spur-of-the-moment adventure? Or have we as a society researched and reserved ourselves into a months-out trip planning trap?

Liam at Green Gardens

As the southeastern coast of Newfoundland came into view from the ferry deck I started to realize that if an unplanned trip was possible anywhere, it was probably possible here. Small white houses dotted the shore of the island, and the rest of the landscape was dominated by a vast expanse of tundra draped over the rugged ridgeline of the Long Range Mountains. I wasn’t sure if it was because it was too windy, too cold, or some combination of both, but trees were either nonexistent or grew close to the ground across the landscape. Newfoundland was… empty. As shorebirds swooped overhead, we drove my now-well-traveled CR-V off the ferry and onto the dock of Channel-Port aux Basques. Setting course farther north, we drove into the heart of the seaside mountains towards Gros Morne.

National parks back home in the United States are experiencing a boom in visitation and popularity. Parks across the US saw a record 331,000,000 visitors enter their gates in 2024, about a 25% increase in visitorship over the course of my lifetime. According to the NPS, visitor numbers have jumped roughly 50% in the past twenty years, and the park service now recommends booking campsites or lodging six to thirteen months in advance, depending on the season. The

era of tossing a tent and a map in the backseat and setting out for the West is over. It’s been replaced by frantically planning trips for the following summer when you would rather be savoring the last breath of the one you’re currently in.

Booking campsites a year out was definitely not on our minds as we pulled into the Gros Morne visitor center the morning after disembarking the ferry. Pulling in two hours after opening, we were still greeted with an empty parking lot and friendly park rangers, one of whom clicked a handheld counter—four, five, he noted as we passed by. Evidently the visitor center hadn’t had many actual visitors yet that day. We chatted with a front desk ranger who told us—much to our delight—that there were openings in every campground in the park and that we could have our pick of where we wanted to sleep for the duration of our stay. With advice from the young, seemingly inexperienced ranger, we settled on three so-called ‘backcountry’ sites, supposedly the “three of the most beautiful sites in the park” that only required a short hike in. The resulting battle between the ranger and the online reservation system was fierce, and it took about 20 minutes of coaxing for the computer to spit out our reservation confirmations. With three small slips of paper in hand,

we strode out into the sunshine.

Greeting us as we drove out of the visitor center was the towering reddish-orange Tablelands. The Tablelands are striking because of their contrast. Looking closer to the surface of Mars than Earth, the bulk of the formation is nestled between normal-looking mountains—a visually striking difference. Armed with a somewhat tattered copy of Geology of Newfoundland borrowed from Liam’s grandfather, we spent longer than I’d like to admit rockhounding and identifying minerals as we wandered from the parking lot up a long glacially-carved valley. We saw only one solitary group of women for the next three hours—a group that we would go on to see at least once a day throughout our time in the park.

As we headed westward towards our campsite for the night, we drove back through geologic time. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site and an IUGS Geological Heritage Site, Gros Morne is widely regarded as a worldwide ‘proving grounds’ for plate tectonics. In a half-hour drive along the park’s main thoroughfare, we traveled through more than half a billion years of geologic time. Along this stretch, we traversed The Tablelands—one of the two places where the Earth’s mantle is exposed at the surface — a mix of basalts from upwelling magma, and sedimentary rocks and carbonates deposited on ancient ocean floors.

Tablelands, Gros Morne National Park

It was in this interplay of ancient processes that geologists were first able to piece together the mechanics of how oceanic plate movement has shaped the continents we see today.

We encountered even fewer people on the two-mile hike into our campsite at the Green Gardens, a spot along the easternmost coastline of the park. The trail was almost all downhill—vast ocean views poked between two hills and the smell of the sea began to wash over us as we inched closer and closer to the shore. Winding around the final corner, the horizon opened up and we found ourselves perched on the

edge of a 200-foot cliff that dropped straight to the ocean. To our left, the cliff gave way to a sloping bluff of greenery stretching straight down to the water. As the product of an ancient volcanic eruption, the surface still reflected the ancient sinuous flow of magma. To the right was a narrow field of flowing grass stretching along the hills to the north as far as the eye could see. Dropping our packs and wandering the landscape, we watched as the sun dipped closer to the horizon over the next two hours, bathing the two of us in rich, thick golden light. As the gold faded to blue and a flicker of

northern lights poked at the edge of the horizon, we set up our camping pads under the open sky and settled down to cook our third (and fourth!) can of chili of the trip. Just like the shores of Cape Breton, this empty cliffside felt like the end of the world.

We woke the next morning to a small herd of sheep that took poorly to us sprawling our gear over their narrow pasture. Like us, they had woken up with the sun and their

presence made the traditionally herculean task of packing up camp all the harder. Our destination for the day was Gros Morne Mountain, the namesake of the park and a towering tabletop monolith that dominates the northern horizon throughout the park. We would camp on the slope of the mountain after climbing it, so after driving to the trailhead we spread out our dew-dampened gear to dry as we cooked lunch. Only packing for one night, we tossed our sleeping

Liam filling up water before the big climb

bags and pads into packs and set off up the mountain.

The undeniable gems of the northern section of the park are the fjords. The backdrop is reminiscent of the Norwegian coastline, just without any houses dotted in bright colors. Liam and I couldn’t believe our eyes as we came up over the top of Gros Morne Mountain and looked down on Ten Mile Pond laid out below us to the north. Here, the water glittered more than 2000 vertical feet below us, a sharp

contrast with the solid rock walls that seemed to rise directly out of the deep. This indeed was a fjord; carved by successive glaciers and at one time connected to the ocean, the ‘ponds’ of Gros Morne reach as far down as 500 feet below sea level and were once connected to the ocean to the west before sedimentation slowly closed off their mouths. Awed by the majesty of the scene, we remained perched above the lake for several minutes, gazing out over the water in silence. There haven’t

Down the mountain to Fairy Gulch

been many landscapes in my life that have well and truly taken my breath away, and this was one of them. It felt like talking would break the silent spell cast by the majesty of the cliffs and neither Liam nor I was eager to spoil their grandeur.

The following night’s campsite was even more gorgeous than the last. The spot was nestled on the saddle between the two mountains and held a lake that seemed so close to the edge that it was ready to flood into the valley below. As we rounded the corner into the valley, the sun was starting to dip low in the sky,

bathing the lake and the hillside beyond in an orange glow. We threw our packs and clothes down on the bank and jumped in, sending ripples across the surface of the water and disrupting the reflected mountainside.

As the sun began to sink low, we set up camp over the ridge alongside a second, smaller pond, and setting our sweat-drenched shirts out to dry on the rocks that ringed the water. Setting up camp wasn’t hard, as a good forecast and two successful nights under the stars with no rain had convinced us that a tent was just dead weight. Parks Canada had managed to fly or hike up enough lumber to build a tent pad and a picnic table, so we scarfed too-spicy ramen in style as sunlight first left our campsite and then crept up the far ridge of the valley, lingering on the mountain framed by the valley before eventually fading into the blue of twilight.

The next morning dawned in much the same way the previous day had ended; sunlight creeping down the opposite

mountainside until I couldn’t help but get myself up and out of my sleeping bag to marvel at the dew-drenched landscape around us. This little saddle, a far cry from any national park campground I’d ever stayed in, was at that moment the most beautiful place I’d ever been. For just a few breaths, it felt like the world was standing still to marvel at mountains towering about me—and I, sitting quietly among them, wasn’t about to be the one to break the silence.

As the morning gave way to day and our sleeping bags disappeared into our packs, the quiet of dawn remained. Perhaps both things can exist in tandem; places that bustle with visitors, yet are still empty enough to constitute an adventure. If, like me, you find yourself having to wake up far too early to secure a spot at a parking lot in the Adirondacks, or find yourself frustrated at being stuck behind a line of weekend hikers vacationing in Vermont, I implore you: it might be time to head far, far, far, away.

Learning off the Land

Lilly Clechenko ‘28

In1938 Helen Haskell said, “We all want the good life for our children: unhurried, unplugged, and independent.” Haskell, the director of Camp Treetops for 40 years, shaped the community into what it is today—a space for children to run barefoot, climb mountains, ride horses, work in gardens, and take care of animals. Here, there is a simple beauty in a tomato straight off the vine, a carrot pulled right from the ground, and raspberries eaten directly from the bush. What cities and suburbs have taken away, Camp Treetops gives back.

Camp Treetops sits at the heart of the Adirondacks, surrounded by the High Peaks,

lakes, and rivers. What sets Treetops apart from other camps is not just their outdoor program but the five acres of farms, gardens, and barn animals that campers spend the summer taking care of. Twice a day, children spend an hour with farmers and counselors harvesting produce, feeding chickens, grooming horses, or tending to the flower beds. These activities build campers’ confidence by teaching them how their food moves from the farm to their plates. The work they put in throughout the summer is celebrated in the final week, during Farm Fest and the Harvest Banquet.

So often, people are removed from where their food comes from and the processes that are involved with bringing food to their plates. Many of the campers I worked with had never tried the produce grown at camp, much less seen where their food comes from at home. However, at Treetops campers help farmers plant seedlings in the perennial flower garden and propagate greens like spinach and kale. Some of my most formative memories from my time as a camper were when the vegetables I refused to eat at home like zucchini, rainbow chard, and kale became a staple of my diet. As the summer goes on, an abundance of produce is ready to be harvested every day. While the kitchen uses the majority of the produce, some is saved for activities where the children make recipes using what they helped grow. As a counselor this past summer, I led activities like these: making quiche using eggs from the chickens and greens from our garden, or making jam using the chokeberries and wild blueberries found across campus.

Perhaps the most difficult yet fulfilling part of the summer is the chicken harvest. Here, campers and counselors come together and support each other in a unique experience. Campers move a bird through every step of the harvest, which culminates with a bird ready to be eaten. This past summer watching so many campers work through their own discomfort and curiosity was an empowering experience for me. It’s a day of overwhelming reverence for the birds and for the people involved in the process of bringing food to the community.

In the final week, our Harvest Banquet emphasizes the interconnectedness of the life and time spent on the land. At the banquet, tables are adorned with perennial flowers and linens, and the dining room fills with the excitement of children eating the food they helped to grow. The many hours of our

collective work go into what we put on our plates. It begins with weeding, growing, and harvesting crops, which are eaten and turned into the food scraps that feed the pigs or become compost. The air is filled with the campers’ quiet satisfaction, knowing they contributed to a beautiful meal.

In the waning days of summer, anticipation builds for Farm Fest. During the event, children happily roam about, enjoying the produce they tended to all summer. It is a morning characterized by tables full of fresh farm produce, pickles, pizza, and even garden sushi. At the pickle tasting table, campers wait patiently for a pink pickled radish or a dilly bean, delicacies many have never seen before. Many campers also try their hand at making scallion pancakes or red currant lemonade. The day is filled with singing, a parade on horseback, potato sack racing, braiding flowers into crowns, and hanging garlic to dry for the winter months. We celebrate the time and commitment of the campers, with the hope that they can carry the values and skills they learned into their life outside of Camp Treetops.

It is such a gift to be able to spend two months in a space removed from the outside world, in a place that encourages trying new things. Simple pleasures like growing and cooking our own food are often under-appreciated in our day to day life. Giving children the opportunity to immerse themselves in nature creates independent, confident young people who embody these values. When I returned to camp this summer as a counselor, I couldn’t help but notice how full circle it all felt. Leading activities that I had participated in as a camper has helped me find new ways to commit Camp Treetops’ values to my life. Each summer that I return to this beautiful place, I feel more connected to the land, the food I eat, and to myself.

DISCOVERING THE ANALOG LANDSCAPE

Liam Reynolds ‘26

Theday before I went to college, my mom gifted me her 1975 Pentax Spotmatic F, a camera that her neighbor had given to her before she first started at Middlebury. Four years later, with that camera still in hand, I have a binder filled with thousands of negatives of black-and-white film shot all over the US, Canada, and New Zealand. After each of these adventures, I’ve returned to the Middlebury College campus to develop every shot in the same darkroom that my mom used when she was a student here, too. As I look toward graduation, I reflect on the ways that the film shot on that same camera has both captivated and taught me over the past four years.

What I love most about black-and-white film is the simplicity. Scientifically, a film camera captures the literal rays of light as they enter the lens—photons chemically altering the silver halide particles suspended in the film. The light darkens the particles that it hits, creating the ‘opposite’ negative image we so often associate with film. Unlike digital photography, where a camera creates a digital interpretation of light entering the lens based on electronic signals from its sensor, black-and-white film is more truthful in essence. In other words, what you see, is what you get.

I see the world differently when I shoot black-andwhite film compared to when I shoot in color. When the eye isn’t dazzled by infinite hues, what you’re capturing matters a lot more. On black-and-white film, composition becomes paramount; things like contrast, texture, and depth of field jump out, because I know they’ll translate well to the monochromatic medium. By looking out for these small details, I end up noticing parts of the world that are often more subtle than color usually reveals. This intentionality is even more important in the darkroom, for if care isn’t taken to highlight these details, the pictures come out flat and dull. As I began to shoot more often, I found myself falling deeper in love with film, for all the ways it differs from a phone or digital camera. Instead of taking 600 pictures a week, I took 10–15. I thought more about the composition of each frame, and I remembered the moments I took them in. Developing my own film only deepened that relationship, because I watched each image come up: first in the developer, then in the fixer, and finally on the photo paper. The more I shot and developed film, the more I realized how rare it is to feel that close to your own images. In a world where it has never been easier to take a picture, it is easy to overlook what it means to translate a real-world scene into a physical object. Being physically involved in shooting film reminds me that the act of capturing a moment and making it tangible is still astonishing.

Over time, I’ve noticed myself drawn again and again to landscapes. Ansel Adams’ work was a huge part of that, as those prints taught me how a black-and-white landscape can hold both delicacy and force at the exact same time. There is something magnetic about a hard foreground against towering clouds. Film feels like the most honest way to render scenes like that. The physicality of the negative and the print makes the place itself feel more physical too.

In 2023, I drove across the country in the wake of Hurricane Hilary. Through California, Nevada, and Utah, we had four days of rain during a time of year where it is normally bone dry. Shooting landscapes in this weather allowed for the mysterious nature of black-and-white film to come through. As I took this photo, I noticed the dark storm clouds in the foreground, and the mountains slowly fading into the rain. As we drove across more basins and ranges, I continued to appreciate

the layering of these misty mountains—contrast between the dark storm clouds and bright spots where sun peeked through. To me, the unpredictability of taking film photos adds to the magic of the format. Unlike digital photography in which you have instant feedback on exposure levels, contrast, light and more, I often don’t know what a photo will end up looking like until months after I take it. This unpredictability is magical and thrilling.

Due to the nature of uncertainty that black-and-white film possesses, I am sometimes disappointed by the results of my images. But more often than not, I am surprised by what actually takes shape. One example of this was a roll of film from the summer of ‘23. Shot on the drive out to California, the undeveloped roll sat in my car for the rest of the summer. Since film degrades in high temperatures, most of the roll ended up fried. Despite the damage, a few beautiful little gems

were left over in the middle of the roll, their contrast enhanced by the months of baking.

A word to those looking towards the world of film: embrace this ethos of failure and unpredictability. Not everything will be perfect, but that makes it special. Capturing the world at a slower pace is worth a try. You might even surprise yourself by what you end up producing, just as all of these photos surprised me.

Sunrise Crescendo

Dylan Meyer ‘28

those mornings I awoke with tied shoelaces and I was dragged forward by the tempo of the rising sun hanging low in the sky like a lonely street light on the dusty main streets of those driveby states Missouri, Kansas, Wyoming before flooding the horizon with rays of autumn leaves and tangerines chased by splashes of blues deep blue waters trickle down from powdered peaks keeping time during the stampeding day washing over the footsteps of Ute, Arapaho, Spanish or over no human trace at all

old men bloom beneath your ankles content to ask “how do you do” diminutive lovers of the alpine air bravely representing a whole in parts for a season at a time

the morning dew makes us drunk off moonshine and sunshine trees bristling and shaking like frantic bebop drums tension and release perfect erratic movement

pikas and marmots duck in and out of rock-crop alleyways and stony street corners rubber soles graze these same boulders taking giant steps over many scales of life: ants tap dancing in the sun and grass pirouetting in the breeze

the wind plays a great saxophone solo biting, friendly, energizing in equal measure like the feeling of tired legs resting on a mountain top

elk stomp and hoof in great herds thumping basslines which drone onward perhaps a Charlie Parker or John Coltrane among them just trying to find it we’re trying to find it too still pushing that rundown jalopy before the moon rises once more

BALANCING PROFIT AND PRESERVATION

Casper

Wilson ‘28

Sixhundred miles off the coast of Ecuador, a remote volcanic hotspot hosts the greatest concentration of marine biodiversity in the world. The Galápagos Islands are young on a geologic timescale, only about five million years old. In that time, over 9,000 species have found their way to the islands, mostly through rafting, swimming, or flight. This has created a unique ecosystem where polar and temperate species coexist in an equatorial tropical climate. The Galápagos Islands were first occupied by a sailor named Patrick Watkins in 1807. Since then, only four of the 20 distinct islands have been inhabited by humans. The remoteness of the archipelago and its many endemic species make it a site of exceptional value, both scientifically and culturally. The Galápagos were first protected by the government of Ecuador in 1932 with the goal of creating a nature preserve insulated from human intervention. However, despite strict regulation, human impact has still managed to make its mark on the islands.

As my family and I rode in the panga boat to the

Galapagos Marine Iguana, Sombrero Chino Island

Blue-footed Booby, North Seymore Island

beach of Santa Fe Island, we could see the shells of dozens of green sea turtles glistening just above the water. Our ship bobbed in the far distance, as close as it was allowed to come to the island. Regulations against large ships were in place to preserve the shallow bay from disturbance. Sharks and sea lions rely on the habitat as a nursing ground, while turtles wait in the shallow water to lay their eggs on the secluded beach at night, hoping no predators find them during this vulnerable process. On a smaller boat, we could see the perfectly clear water as we made our way towards the shoreline. It offered a window to the seafloor, where we could see the turtles grazing. As we landed on the beach, a colony of sea lions bustled about on the rocks. The pups played in the shallow break while the alpha male kept a close watch on them, making sure they didn’t get too close to us. While we walked along the designated paths, we came across the Santa Fe iguana, a species found only on this small island. The iguanas were comfortable sitting right on the path, seemingly oblivious to the destructive effect humans can have on unregulated land. It’s experiences like these that visitors get a glimpse into the island’s natural, wild state.

Santa Fe Iguana, Santa Fe Island

Genovesa Island is another example of a well-preserved island, known for its extensive bird population. Since humans have never hunted or introduced any predators there, the avian residents have developed some unique behaviors. For example, the masked boobies on the island nest on the ground, making little mats out of sticks.

That afternoon, we stayed on Genovesa Island and climbed Prince Philip’s Steps, which are precariously carved into a cliffside. Atop the cliff, we searched for the Galápagos short-eared owl. They no longer have nocturnal tendencies and spend most of their time on the ground, hunting shorebirds between the rocks. We eventually found one in a crevice, its red feathers blending in with the clay-rich stone. The continued absence of human interference on this island has not only preserved the species endemic to the region but has also allowed new behaviors to develop in these species, seen nowhere else in the world.

Red-footed Booby, Genovesa Island

Masked Booby, Genovesa Island

Later in the week, we visited South Plaza Island. We landed on a bleak, rocky landscape with prickly pear cacti as tall as trees scattered across the island. Galápagos land iguanas the size of house cats packed around the “trunks” of the cacti, waiting for fruit to drop. Across the island, rusting metal cages were laid out in neat rows. Some contained small cactus plants while others were broken open and empty. We learned about a recent storm that wiped out the plant life on the island and a subsequent restoration effort to replenish the island’s natural appearance. Projects like this were often pitched

Red-footed Booby, Genovesa Island

to make islands look more “natural” to increase tourism to an area, but they normally end up abandoned with the funds in the pocket of some park official. Many conservationists blame the politicization of the Galápagos National Park—a result of its classification as an Ecuadorian province—saying that authorities lost sight of the founding principles of the park, chasing profits instead. Above all, this exchange raises an important moral truth: profit should never take precedence over the protection of wildlife, especially in a national park.

Human-induced environmental damage in the Galápagos isn’t a recent trend. We visited the Darwin Research Center on Santa Cruz Island, which features a number of partner institutions from around the world. One such institute is the California Academy of Sciences, which boasts the largest collection of scientific specimens from the Galápagos. Unfortunately, the means of achieving such a collection also contributed to the decline of native tortoise populations. During the process, researchers took hundreds of specimens from across the archipelago–some to preserve, and some to eat on their return voyage. Because the expedition was in 1905, such practices were common among naturalists. On its website, the Academy writes that researchers thought the tortoises were quickly going extinct and thus were simply trying to preserve as many specimens as they could before they were gone. While the Academy sees the voyage as a success, several representatives of the institution have lamented the toll of the voyage. I was saddened to see the devastating impact that a scientific institution—and one that I look up to—had on the local ecosystem.

On the flip side, recent efforts by the Darwin Research Center have had a much more positive impact on the preservation of the islands. The center runs a breeding program for all 13 extant species of Galápagos tortoises to

repopulate the islands, and in doing so has made progress in limiting the effect of several invasive species that have been introduced to the islands. Despite early damage caused by the Academy, the institution now provides active financial and intellectual support toward the preservation of the Galápagos Islands and the continued development of the Darwin Research Center.

I was devastated to see the damage that scientific exploration has caused on these islands, but I didn’t have to go far to see a thriving community in partnership with the natural world. Puerto Ayora is the cultural capital of the Galápagos, also situated on Santa Cruz Island. The main square was filled with gift shops, restaurants, and guide agencies. However, as I ventured further down the street, gift shops gave way to grocery stores and farmers’ markets, full of locally grown produce. As I passed a soccer stadium where a youth team practiced, their shrill voices echoing off of the expansive stands. Roads wove their way through forests and grasslands, connecting farmlands. I noticed a large gap at the bottom of all the fences, likely to allow for the unimpeded migration of tortoises. On this island, a thriving city hub is able to exist without having a destructive effect on the ecosystems around it.

Galapagos Sea Lion, Mosquera Island

Galapagos Sea Lion, Sombrero Chino Island

Resource extraction in some form is required to sustain a human population in the Galápagos. Restrictions walk a fine line between sustaining the wild populations and supporting local communities. One example of these restrictions lies in the fishing industry, which we saw in action off Santa Fe Island. As we were kayaking back to our boat, we passed fishermen gutting their catch off of their small skiff, only equipped with a few fishing rods. Brown pelicans crowded around the boat, hoping to get a free dinner. Our guide told us that fishing licenses are only distributed to those with citizenship of the Galápagos who hold the understanding that they will harvest sustainably. This agreement keeps extraction to a sustainable level, providing the resources the people of the Galápagos need while limiting industrial fishing in the area.

The people of the Galápagos have a deep connection to the natural environment surrounding them. History has told a nuanced tale, a clash between exploiting nature’s gifts, and simply letting them exist as they are. Thanks to growing public sentiment, the archipelago is now home to both a thriving local culture and a place that sustains its innate biodiversity. In the hands of vigilant stewards, the future of the Galápagos is bright, providing a space for sustainable living side by side with the archipelago’s unique ecosystems.

Fishermen near Santa Fe Island

Unloading at the Docks, Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz

The Spirit of the Altai

A Young Girl’s Place in the Changing Tradition of Mongolian Eagle Hunting

Eve Sarti ‘29

Cracked yellow talons sink deep into the worn leather of her father’s old glove. Each piercing black point wraps nearly all the way around Aigyerim’s delicate wrist, her arm staying ever so steady as the Golden Eagle spreads its wings, revealing eight feet of sun-gilded feathers. For most people, riding a horse and carrying a 15-pound bird on their arm, all while herding a few hundred sheep might prove difficult, but Aigyerim has been doing this every day since she was six. Now, at twelve, she spends her mornings galloping past us on her half-wild horse, laughing as Brady and I watch with our jaws hanging open.

“In this endlessly unfolding terrain, it is not uncommon for a family’s closest neighbor to be almost a day’s horse ride away.”

From the doorway of her family’s Ger, a traditional nomadic Mongolian home, Aigyerim’s mother calls us inside. Crouching to step through the little wooden door, the warmth ripples off the wood stove as the scent of freshly fried bread wraps around me. The walls are lined with hand-woven rugs and the ceiling curves upwards, opening at the top to allow the smoke to rise into the misty morning sky. Aigyerim’s mother hands us bowls of

suutei tsai, a hot, salty milk tea, and rolls of boortsog, a fried, crispy bread. Lost in the soft chatter of Kazakh around me, I feel at peace.

The Kazakh people have lived in the Altai Mountains of Western Mongolia since their migration from what is now Xinjiang, China in the mid1800s. Their nomadic lifestyle is deeply intertwined with every aspect of the harsh mountainous landscape. Four times a year, they pack up their Gers and move to new locations that better suit their livestock for the coming season. Until recently, their entire diet and livelihood depended on their animals: sheep, yaks, horses, and goats. Even something as simple as drinking water isn’t the norm. Instead, milk tea, made from whatever animal is milked that day, is the standard beverage. In this endlessly unfolding terrain, it is not uncommon for a family’s closest neighbor to be almost a day’s horse ride away.

Traveling on my gap year last spring, I had the opportunity to live with a nomadic family in the Western Mongolian region, Bayan-Ölgii. Situated in the heart of the Altai Mountains—where the borders of Mongolia, China, Russia, and Kazakhstan converge—the region is home to one of the last remaining communities that practice traditional eagle hunting. It was there that I met Aigyerim, a twelve-year-old girl who had boldly taken on a role usually reserved for men.

In Kazakh culture, the art of training Golden Eagles to hunt from horseback is usually passed from father to son. But with Aigyerim’s older

Aigyerim and her mother milking their horse

brother studying in Ulaanbaatar, she had taken on the responsibility herself. Aigyerim filled her days by tending to livestock and helping to train the eagle to hunt foxes and other small animals. A few days a week she rode her horse nearly two hours to attend school. As the impacts of modernization take root and more Kazakh families relocate to cities, keeping the sacred eagle hunting tradition going has become even more vital. Having children—and especially girls like Aigyerim to carry on these traditions—keeps the spirit of the Altai Mountains alive.

After a few days of herding, riding, and wandering the Altai with Aigyerim’s family, it was time for the most important horse race of the year. That morning, we were awoken with shots of fermented horse milk and plenty of boortsog before we were ushered out the door to saddle up the horses. Aigyerim’s father, Rakhiymbyek, had two huge bottles of cold milk tea strapped to the back of his saddle for the race. We rode in silence for the next three hours through the desolate valleys. Even without sharing a common language, let alone a word, I could feel the energy building and the quiet thrill in the crisp morning air. Within minutes, specks of movement littered the once-clear horizon— there were horses, riders, families, and plenty of motorcycles everywhere across the field.

In recent years, using motorcycles for herding in place of horses has taken the nomadic lifestyle by storm. Now, we saw them before us, nearly outnumbering the horses. Aigyerim was set to compete in the

Our VW bus outside of Aigyerim’s home

races for both the two and three-year-old horses. The racers rode out until they disappeared into the horizon. We waited by the finish line, the wind carrying faint sounds of hooves and engines somewhere far off. Then, the first shapes began to reappear—Aigyerim was out front! Fifteen boys, most of whom were years older than Aigyerim, trailed behind her. I was captivated by the sight of the dust swirling around them and the raw, untamed energy. Aigyerim crossed the line first, breaking into a wide grin.

Across Mongolia, the rumble of motorcycles race alongside horses on the steppe and through the mountains. Shelves once stocked with only dairy and meat from their herds now hold rice, flour, candy, and soda brought from nearby towns. Modernization is reshaping the rhythm of typ-

ical nomadic life, and these once-inaccessible places are now destinations for visitors like me. Tourism here reveals a culture previously unknown, and circulates money through local communities. Yet, for many nomadic families, these changes have created new challenges. It is increasingly common for mothers and their young children to move away from home as schooling becomes more strictly enforced across rural Mongolia. While this shift opens doors to education and new possibilities, it also pulls families apart and disrupts the norms of nomadic life. As education becomes an expectation and living without an income is no longer possible, young women are often the ones leaving home and seeking futures beyond typical nomadic lives, while many men remain behind. Aigyerim’s life is a powerful defiance of this pattern.

At twelve, she has taken her brother’s role as eagle hunter and balances both her studies and daily chores. When the weather turned brisk and the occasional snowflake drifted through the opening at the top of the Ger, we gathered around the fire, passing phones back and forth, swapping photos, and drinking fermented horse milk as we tried to mime out stories from our lives. One especially brisk night, two lambs were too weak to spend the night outside. Aigyerim and her mother wrapped them in blankets and slept beside them by the fire. The next morning, Aigyerim showed us how to stitch small flowers into our jackets. Life in Mongolia moved slow, but with an intention that made every small act feel significant.

Before I left, I gave her a small, dark blue piece of tanzanite, and she handed me a beautiful Golden Eagle feather. For her, it symbolized a hope to one day see other parts of the world. For me, it was a promise to return and keep sharing the story of the Altai Mountain eagle hunters.

RUN,BOY,RUN LucasBasham‘28

Photos by Alex Basham

InMiddlebury, most trees were still in their jungle green summer state. But here in Northeast Kingdom, Vermont, almost on the Canadian border, early October foliage was already peaking. On the tarmac of the local airport, I laced up my royal blue Brooks Ghosts and tacked on my Fly to Pie Marathon bib. This moment was a climax of thousands of miles across countless cities over three years. From Zaragoza, Spain, to Mývatn, Iceland, to loops upon loops of the Trail Around Middlebury, I had been building not just strength and stamina, but also a sense of place. As the onset of the race neared, a warm, homey contentment from the familiar Vermont landscape clashed with inevitable pre-race nerves. The gunshot sounded and suddenly I was running again.

It was in Zaragoza, Spain, where I studied abroad my junior year of high school, where I began to love running. My parents, like me, were runners. Core memories of watching them race the New York City Marathon through our neighborhood are mixed with less joyful ones of being dragged on runs alongside them. I was a real sports kid—what was the point of running if I could go play instead?

It wasn’t until I went on that first spontaneous run in Zaragoza that I took any joy in it at all. As the claustrophobic European elevator creaked its way to ground level, I decided to run to the place I had become most familiar with after my first month: Parque Grande. I searched “running songs” on Spotify, clicked on Run Boy Run by Woodkid, and stepped out onto dawn’s barren streets. The song’s

dramatic bells chimed as I ran the one mile there—the only route I knew. Another runner passed as I trudged up the park’s zigzagging stairs and my gaze expanded. First down at the fountain’s still pool, out at the garden, the stadium lights, and further towards the rest of the city. I was learning to find home in the distance. It felt boring to return the way I came, so I left the park onto a new street in what felt like the right direction, and was pleasantly surprised when it merged onto a familiar avenue. I made my way home, where I had a tostada con jamón and an argument with my host brother waiting for me. I belonged here. I didn’t know it then, but I had just laid the groundwork for a style of adventure and home building that would wholly shape my approach to place.

Every couple of mornings for the rest of the year, I clicked on Run Boy Run and ran that route. Sometimes I would run it with friends, and sometimes I would run somewhere new, but I would always connect back onto my threemile Parque Grande loop. As Zaragoza became my home, I gradually drew more lines into my mental map after each run. With this new spirit of adventure, I stepped out onto several Spanish cities’ golden sunrise streets over the course of the year. Using the landmarks and sense of direction I had gained on school-led outings the day before, I would let my feet wander with full trust that they’d find their way back to the hotel by the time my classmates woke up.

Out of my head and back in Vermont, my calves began to tighten as mile four turned uphill. While I still felt their magic, I was no longer on golden Spanish streets. God, I despise hills. Trekking another 22 miles at my goal pace felt impossible. Yet I had found a comfort in my reminiscence of running across Spain, and as I looked up from my blurring shoes, I found another comfort in the familiarity of Vermont’s hills.

On the morning of Admitted Students Day the spring before my first semester, I searched for the fabled Trail Around Middlebury (TAM)—which loops 19 miles of mostly trail around the town of Middlebury—on AllTrails. I ventured to campus from the Courtyard Marriott on Court Street, slipping in the mid-April mud as I passed the middle school and fumbling my way between the jumbled trailheads that make up those two miles. Just as I had in those new Spanish cities, I made it back to the hotel as my friends awoke, having already gotten a sneak peak of campus, the setting for the day’s adventure. This time, like Zaragoza, the new setting would become home.

Come fall, I quickly declared two other boys I met during orientation week my best friends. One of my first and best memories with them is running the TAM’s Class of ‘97 trail from the golf course to the Knoll, Middlebury’s organic farm, for the first time. The next day, under the canopy of the

trail’s still summer trees, I bushwacked my way off of the trail in search of the cemetery, which lay less than 50 yards away according to my Google Maps satellite search. The cemetery was next to my dorm, so I hoped to find a way to more efficiently connect to the TAM. While said path proved nonexistent, the cemetery and its adjacent woods became a convenient and necessary space of solace when I was later stuck indoors on crutches that winter. Those few static months felt infinite; while my mental running map was frozen, I felt offbeat and stuck. I often hobbled over to the cemetery, looking longingly along the tree line and imagining the trail just behind the ridge. But come spring, finally running again, on both the TAM and road, my mental map grew and refined once again, and my relationship to this small Vermont town evolved more than it could in any classroom.

As I summited the first of three monstrous hills at mile 11, I gazed down at the steep slope and gladly let my legs loose. I amended my earlier refrain: God, I despise uphills. After all, the downhills aren’t so bad. The short and steep descent of the golf course trail, arguably

the most hilly segment of the TAM, my second favorite three-mile loop, had prepared me for this. While my knees are still young, I let ever-friendly gravity coast me down the mountain for four miles, hitting 13.1 along the way.

My first half marathon was the Middlebury Maple Run during freshman year. I heavily underestimated myself, running each mile faster than the last and claiming my fastest mile ever on number 13. The route took us north—new territory for me at the time—before coming back through campus and onto the golf course trail. It finished with an out-and-back through more new territory heading south on South Street. That friendly middle stretch was race altering; feeling comfortable running through campus, I had the chance to recognize my own strength and picked up the pace.

The second time I ran 13.1 wasn’t a race, just a New Year’s morning outing through Denver, Colorado. I found a grid-blocked neighborhood and finished my run by running in a pattern that spelled out “2025” so the drawing would show up on my Strava map. My third was the Steel Rail Half

in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, for which I did some training and ultimately blew my pace expectations out of the water by 20 minutes. There, I owe no success to a friendly landscape, but to the familiar cheers of my best friend every few miles— the same best friend with whom I first explored the TAM.

My fourth was around Iceland’s Lake Mývatn this past summer, a race I spontaneously signed up for in our rented campervan just a few days before. “Mývatn” I would later learn, means “midges” or small fly, which explains why my arms didn’t swing by my side but by my head, swatting away the little fleas for most of the race. I finished first of the men, and second only to Sigpora Brynja, the small village’s running prodigy. My prize was free entry into the geothermal nature baths, a few pounds of local smoked trout, and geyser bread.