Here, Not. Here, Not.

Edited by Micol Curatolo / Design by Lù Chén / Alejandra Alarcón / Francesca Bogani Amadori / Lucy Davis / Amy Gelera, S.U.R. / Lotta Hagelin / Naomi and Wanda Holopainen / Impropias Collective / Alice Mutoni, Ubuntu Film Club / Muniba Rasheed / Eliisa Suvanto, Porin kulttuurisäätö

Editor

Micol Curatolo

Contributors

Alejandra Alarcón, Francesca Bogani Amadori, Micol Curatolo, Lucy Davis, Amy Gelera, Lotta Hagelin, Naomi and Wanda Holopainen, Impropias Collective (Mercedes Balarezo Fernández, Yes Escobar, Paola Nieto Paredes, Daniela Pascual Esparza), Alice Mutoni (Ubuntu Film Club), Muniba Rasheed, Eliisa Suvanto (Porin kulttuurisäätö)

Design and cover Ⓒ Lù Chén 2024

Text copyright Ⓒ the editor and authors

Proofreading

Nastia Svarevska

Typefaces

Literata, Open Sans, Terminal Grotesque

Printed by Tallinn Book Printers, 2024

First Edition: 100 Helsinki, Finland

Tanks to Patrizia Costantin for the advice, and to the MA program Visual Cultures, Curating and Contemporary Art at Aalto University.

Supported by Aalto ARTS

ISBN 978-952-65469-0-2 (sofcover)

ISBN 978-952-65469-1-9 (PDF)

Here, Not.

Dialogues on art and the making of here

Nooks, thresholds, and highways, Micol Curatolo

‘I’ve discovered this humming’, Francesca Bogani Amadori

Museum Property, Lotta Hagelin

‘One plus one becomes three’, Impropias Collective

‘Trying not to build walls’, Eliisa Suvanto

‘From us to us’, Alice Mutoni

Contents

1 25 41 47 67 89

‘In this mulch of voices something can hatch’, Lucy Davis

‘Heads on a shared stomach’, Naomi and Wanda Holopainen

Subcontinental Helsinki, Muniba Rasheed

‘Tactile connection’, Alejandra Alarcón

A Resistance Against Abundant Comfort, Amy Gelera

Lù Chén on design

105 123 139 147 167 179

Nooks, Threshold, and Highways

Micol Curatolo

Micol Curatolo

1

Micol Curatolo is a cultural worker in the feld of contemporary art. Her research refects on everyday borders, belonging and geography. Using border thinking, Micol investigates how arts and culture negotiate identity, participation, and experiences of migration. Micol works with multi-vocal and everyday formats. She is interested in creative work that addresses people's stories, their possible conficts and their common emotions.

2

Here, Not. is a project about closeness.

Here, as in the tram line connecting your fat to mine, to the sea, to the university; connecting the cultural centre to the hospital, your place of work, the Parliament House. Here, as in Helsinki, Finland. Here, where we have moved from elsewhere and where for some time we’ll stay. Here, yours at times and at times not.

Here, Not. investigates how people express identity and belonging through contemporary art in the urban spaces of Helsinki.

‘Border thinking’ is the methodology behind the book.

A border is a device controlled to let some-thing and someone cross, deciding if they can enter or exit a territory and, by that choice, controlling where they can exist. Tose who cross undergo a transformation: value is accrued or lost, identity is assigned, new duties and roles are imposed.

Tinking about and with borders implies that we pay attention to all the border lines operating in our

3

environments and actions. Border thinking points to the everyday borders that modulate the regimes of visibility –that is, who and what is present and recognised – through which we construct the places we inhabit. Border thinking can help us refect on how cultural work participates, every day, in the global and local dynamics through which we produce geographies that are accessible, safe, and home for some and not for others.

In the book, these refections develop together with fourteen arts and cultural workers based in Helsinki. Teir ten contributions focus on what is happening across and beyond the threshold of the art gallery and how art sits and is bridged into the city.

To visualise these dynamics, we can play with three elements: — lines; — movement along, across, and on these lines; — the sites produced by those lines and the people and art moving along them.

Su cuerpo es una bocacalle.

1 Her body is the crossroads.

4

is a site of negotiation. A threshold.

‘…every word, every syllable I utter comes from a riot within my mouth. It is a babel between subconscious, tongue, teeth and vocal cords ...

See, this speech comes from a slaughterhouse I call my mouth.

See, this mouth is a battlefeld, a clash of unyielding cultures warring for dominance.

See, my tongue is a traumatized survivor lost in an alien fuency.

See, this accent is how I fnd my way home…’2

Relocating triggers a communication lag: you shout I am here, and the cavities of your own body, in an unexpected unison with the fords of this new place, echo back I am not.

5

uth

Your m

Urban environments are flled with noise but unbothered in words.

C’è una terra che tace e non è terra tua.3

Tere’s a land keeping silent and that land isn’t yours.

‘Ewú shoduwè?

It’s about time you learn my language too.’ 4

Bodies can actively ‘unbelong’ to reclaim presence.5 It is a power play with the ability to go un-seen.

Here is the problem and the answer. Here, at the tensive hyphen between un—seen.

Te —, that’s the line we are going to follow.

Te gasp, the crack, the pause, the act of pulling apart in order to keep together.

Te erasure of some(things), made invisible, which reinforces the visibility of others. It is along these hyphens that we become complicit.

6

Here, Not. tries to stand on them. It considers the line in relation to movement not simply as a trace of direction but as a place to linger on: a viewing platform in motion.

My curatorial research follows the way artworks and moving people travel and are present, tracing and reconfguring the city and its spaces for culture. ‘Tese cartographies of collective life […] frame a sense of what

7Art curating: the practice that coordinates, imagines, and arranges the material, intellectual, aesthetic, and personal interactions between disparate artistic works, practices, and practitioners to create a collective result (exhibition, event, public programme, etc) and communicate its framework with the audience. Curating is part of a broader teamwork of technicians, designers, educators, historians, artists, and experts in diferent felds. is possible.’6 Migration, belonging, home, memory, comfort, public expressions of afection and identity, participation, gender, and collective work. Art curating7 can ask questions to itself and others by following movement:

‘Te question of what diversity does is also, then, a question of where diversity goes (and where it does not), as well as in whom and in what diversity is deposited (as well as in whom or in what it is not).’8

To be honest, Here, Not. is especially a project about unresolved questions and scavenging for where they lead. Here, as in where my practice develops towards and how it

7

gets there. Why me? And if me, how? Not, as in doing the work to notice and unlearn my own complicity.

Nooks

Te word environment indicates the material network between a place and all the beings that make that place. Te environment is about profound physical enmeshment. Space and place, accordingly, are never abstract nor empty.9 Place is a complication of space. Place suggests the making of cultural and symbolic layers with a site. In reverse, making place happens as material, cultural and symbolic relations are threaded with a site to create its communal living. Anthropologist Tim Ingold describes place as a knot: the lively reality produced by the interdependent relations between diverse agents in motion and their home.

‘... human existence is not fundamentally place-bound, as Christopher Tilley (2004: 25) maintains, but place-binding. It unfolds not in places but along paths. Proceeding along a path, every inhabitant lays a trail. Where

8

Te production of Here is a work of meaning-making that takes place along trajectories. Tese create nooks: the triangulation of a couple of livelihoods interacting within the larger site. A nook, we can imagine it, is a busy relational place with blurry borders to its surroundings.

To me, this image works well to defne what happens around arts and culture, too. Cultural workers, artworks, and audiences together create a nook of sorts: a triangulation of their actions threading a new placemaking while inevitably interacting with the framework that the site itself carries. I want to think about the contemporary art exhibition as one such place where art workers and visitors are tightly knotted together in the act of fulflling their roles, but also by the extension of their lives into inhabitants meet, trails are entwined, as the life of each becomes bound up with the other. [...] Places, then, are like knots, and the threads from which they are tied are lines of wayfaring. A house, for example, is a place where the lines of its residents are tightly knotted together.’10

9

Meshwork—Patchwork—Homework—Linework— Bodywork—Work

the space. Feminism of Colour and intersectional theory11 unravel the ways in which ‘a body can be a meeting point,’ a place-making knot of its own kind.12 Tis opens a door to noticing how the presence of certain bodies in the urban environment leaks into the space of the art exhibition, too.

Let’s come back to border thinking.

Bordering

As borders become increasingly ‘mobile, portable, omnipresent, and ubiquitous realities [...] to be alive, or to survive, is more and more co-terminus with the capacity to move.’13 Political theorist Achille Mbembe calls borderization the practice of multiplying borders to control and strengthen geographical divisions across diferent scales of place. Tis is a process of space modifcation: from nation-state borders to local communities or private buildings, bordering devices are designed and policed to control who can enter and who can leave. Everyone and everything is assigned a certain capacity of crossing.

Te impossibility of entering or staying in a site does not end within itself: it assigns racial defnitions to those who cannot cross, becoming endangered along multiple and disseminated lines.14 Tese are kinopolitics – politics of movement. Borderization draws a geography

10

Te mobility of a person racialised under the infrastructures of white supremacy is exponentially more controlled than those who hold privilege within the same infrastructures. A large legacy of BIPOC authors, artists, and thinkers15 has documented how racialised that exacerbates exclusion based on value and race. Borderization repeatedly cuts people out of place. border cesura a midline pause imposed on your thinking, severing the fow. Losing meaning.

15BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, People of Colour. Some authors working with the themes of this book are Frantz Fanon, Audre Lorde, Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Homi K. Bhabha, Irit Rogof, Ana Mendieta, among others. livelihoods are erased from the public sphere by forced marginalisation, exactly by preventing the racialised body from entering, inhabiting, and expressing in the public environment.15 Simultaneously, the racialised person becomes hypervisible and hyper-present. In Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952):

‘A

triple persona, [...] three places, [...] I existed triply: I occupied

11

space. I moved toward the other [...] the evanescent other, hostile but not opaque, transparent, not there, disappeared. Nausea ... I was responsible at the same time for my body, for my race, for my ancestors. I discovered my blackness [...] My body was given back to me sprawled out, distorted, recolored, clad in mourning on that white winter day.’16

Bordering becomes habitual to the point of going unnoticed; ‘this is why when we attend to intersectionality we are actually making a point,’ scholar Sara Ahmed writes that ‘there is labor in attending to what recedes from view.’17

Let’s talk about transparency then.

Tim Ingold ofers the example of a carpenter who, hammering, pays real attention to the hammer only when the tool does not work as desired.18 Similarly, artist Antoni Gaudì notes that a design is noticed only when it does not function as wanted.19 In other words, devices are considered malfunctioning when the interaction isn’t easy enough to go unnoticed. Gaudì moulded a door handle into his hand so it could disappear in the perception of a body similar to his own.

Te form Western society gives to the world, with its

12

functionality, is moulded to the man. If things (and people) are labelled as functioning (or not), right (or not), when they are smooth(less) to one person, who is the mould?

Thresholds

A door ajar20 opened by a handle moulded in your palm.

Let’s set one foot in the art gallery and the other on the city street: standing across the threshold, our view is split by the doorframe.

On both sides, you’ll fnd a culturally loaded environment that can host potential nooks for speculative, idealistic, brutal, and sof, temporarily knotted worlds. Tis art-nook is a place where we can feel safe to test and try out, where the collective work of making culture turns us into one industrious dis-jointed body; but let’s not hide in our nook for too long. Taking over a space, it is on us to decide how permeable its doors will become and for whom.

‘Saying I don’t know is a start. What then if we hear I don’t know not as a declaration of ignorance but rather as an appeal for intimacy? [...] Intimacy

13

leaves doors ajar to encounters that might be difcult, messy. [...] As the door ajar can induce encounters based on trust and risk; it acknowledges that there cannot be trust without risk, and vice versa. [...] A door ajar does not mean that one has the right to enter, but it ofers an invitation to stand at the threshold and knock.’21

A door is constituent to the space but also somewhat out of it. Te door is an afordance, where value and meaning are discovered in the process of use, but also a site where they ‘can be directly perceived.’22 Te door functions as a mouth: a point of entrance, negotiation, decision-making, a place of exploration, and intimacy. Half private, half public.

Te interesting thing about doors is that they develop in a certain (horizontal) direction while they let movement happen orthogonally across. At the crossroads of these directions, one can actually stand still. If one inhabits a point along a line of travel, here, time pauses and enlarges. Te quick communication that the door invites is then embodied and expanded, catalysed and shredded by the body who decides to sit on that threshold and express in movement and words, to become a bridge.

Architect and activist Stavros Stavrides calls thresholds the in-between places, the passages built when people

14

attempt to create an ‘emancipatory spaciality’ and develop border consciousness.23 Tis happens when people decide to meet each other through the struggle of recognising diferences and addressing personal change. It is a painful, confictual process because it requires crossing internal borders upheld for safety, to encounter the boundaries of another’s livelihood. Tere is no romanticism here; rather a reminder that only through experiences of contact and self-recognition one unlearns phobias – xenophobia, transphobia, homophobia, etc. – which trap both the othered and the othering in the gaps of our knowledge where narratives of danger have overgrown. For this, thresholds can only be made collectively: ‘A type of collaboration where you try to let everyone work in ways that are individually right for them. [...] A group becomes a collective when they make a conscious decision and choose to see each other as equals.’24 To build thresholds, we need a (un)learning crowd in motion.

Here, Not. plays with the communication and engagement created by such attempts to inhabit and settle at the door; with what the door can do to bodies who use it for transitioning rather than travel.

15

Highways

A line of travel is other than a line of movement. Movement inhabits place. In movement, one makes sense of the world and continuously produces knowledge with reality’s shapeshifing. Instead, a line of travel moves between two points less to understand than to arrive.

Standing at the tram stop, the overhead wires tangle above our heads. We await to be picked up. Sit and move. Drop of – it is a new place we are in.

Knowledge is relational, experiential, temporal and creative. Information is quick, set, analytical and synthetic. Travel takes away the ‘all-around perception’ by which one notices others.25 As one loses the habit of producing knowledge ecologically, one wants to travel faster. Here we are: ‘emplacement becomes enclosure, travelling becomes transport, and ways of knowing become transmitted culture.’26

I N V E R S I O N

‘To be alive, or to remain alive, is increasingly tantamount to being able to move speedily.’27

T R A P

16

My thoughts are rushing again. How does one slow down without ceasing to move? How does one make art without becoming elitist?

COUNTERSPACE’s ‘folded architectures’ come to mind: art publications which become ‘a sandwich wrapper, a falafel house shop-window poster, a tablecloth in the central market for ifar.’28 I want to make events that are as visceral to people’s lives as the breakfast blanket they eat porridge on in the morning; artefacts you can carry in your pocket next to a pack of mints; exhibitions that enter our lives as another one of the things we feed ourselves with.

Remember Ingold’s upset carpenter and Gaudì’s bodily handle?

‘Humans alone are haunted by the spectre of the loss of meaning that occurs when action fails;’ humans imagine reality by ‘the occasional glimpses of a world rendered meaningless by its dissociation from action.’29

Let art be something that moves and disappears and carries us away.

17

What I am chasing afer as a cultural worker are the zones where we can catch as many glimpses of our world rendered for a moment meaningless to ourselves but meaningful to others. Here, Not. is chasing for fractures where reality enlarges onto the world of someone/something else. Moving to explore, to train the eye, and to tackle our biases and fears. To see the many worlds overlaid on our shared spaces. Let’s follow movement to ask questions, notice closeness, and see complicity. Here, I will stand on the line of those questions, at the door of a gallery, on the threshold of my fellow art workers’ practices, and open myself to conversations that can hint at where to go.

Dialogues

Access to movement means access to culture and a choice over how to participate. Curator Carla Gimeno Jaria says that the role of the curator at the borders involves ‘the development of patterns of hospitality, by providing the spatio-temporal conditions to engender encounters between unknown entities or bodies.’30 I will hold that curating should always, not only at the borders, be an extended and temporal efort to negotiate and open encounters. Tis is another reason why border thinking is important and efcient around any border, starting with a door: to work collectively on ‘what kind of citizenship is

18

aforded’ by cultural workers and audiences in the urban and artistic space of Here.31

In the spirit of border thinking, I have invited fourteen Helsinki-based artists, designers, and cultural workers to be in conversation around their practices. Dancing or cooking together, in their studio or a greenhouse, I have tried to break away from the formal dynamic between curator-artist and interviewer-interviewee. I hope this resonates in the contributions: seven conversations, two photographic series, and an opinion piece, beautifully designed by Lù. Meeting these people and their practices has ofered moments of discovery, pleasure, and refection. It has helped me navigate the beginning of my career and my being in Finland. Tey all work on participation, accessibility, and geography, cultivating larger, multidisciplinary, and inclusive defnitions of arts and art spaces in Helsinki’s cultural scene.

‘I’ve discovered this humming’ is a conversation with artist Francesca Bogani Amadori, whose work overlays the rhythms of Lima, Perù and Helsinki, Finland, in multimedia archives of walks and feld recordings. Together, we refect on safety, visibility, and policing in public urban spaces.

Lotta Hagelin presents Museum Property (2023). Te photographs capture a tension between stillness and motion that tells about the objectifcation that Sámi people and culture have

19

sufered by the Nordic nation states, it portrays the endurance and activism of Sámi youth, and echoes the repatriation of Sámi heritage from the Finnish National Museum to the Sámi Museum Siida.

Impropias Collective discuss the power, awkwardness, and joy of dancing with strangers as a social practice, when ‘One plus one becomes three’ and dance recalibrates interactions. Daniela, Mercedes, Paola, and Yes connect music, urban rhythms, and memory to deal with how bodies move in the built environment, partying to Latin-American tunes.

Curator-producer Eliisa Suvanto shares about the values embedded in their collective work with Porin kulttuurisäätö, the bureaucracy of accessing public spaces in Finland, and the conversations hosted by site-specifc public art, stubbornly and purposefully ‘Trying not to build walls’.

‘From us to us’ is a conversation with Alice Mutoni, one of the three founders of Ubuntu Film Club. With their free documentary screenings, Alice, Rewina and Fiona have created a low-threshold space for BIPOC youth and friends to learn and talk about contemporary issues while having fun and catalysing a sense of excitement and belonging.

20

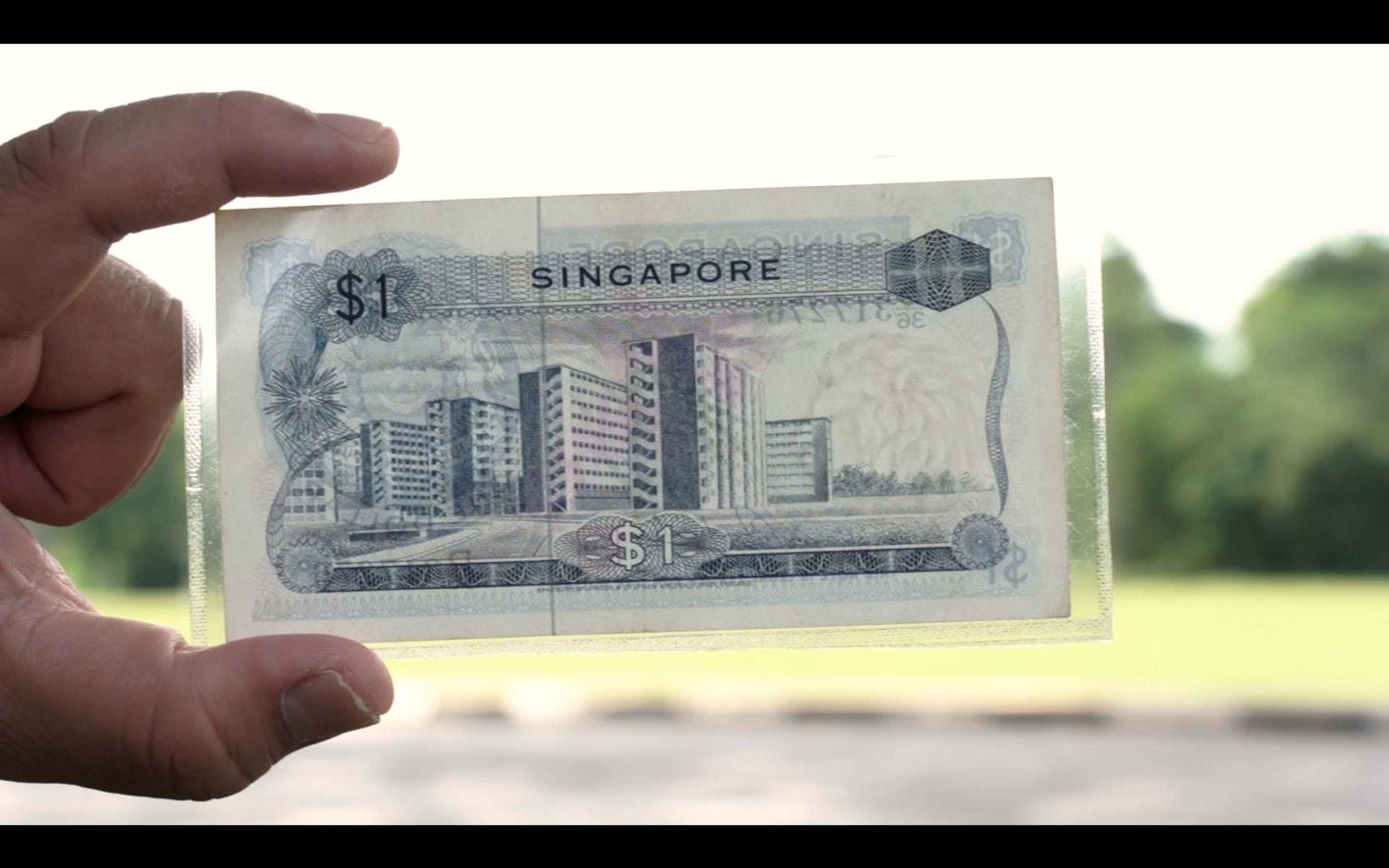

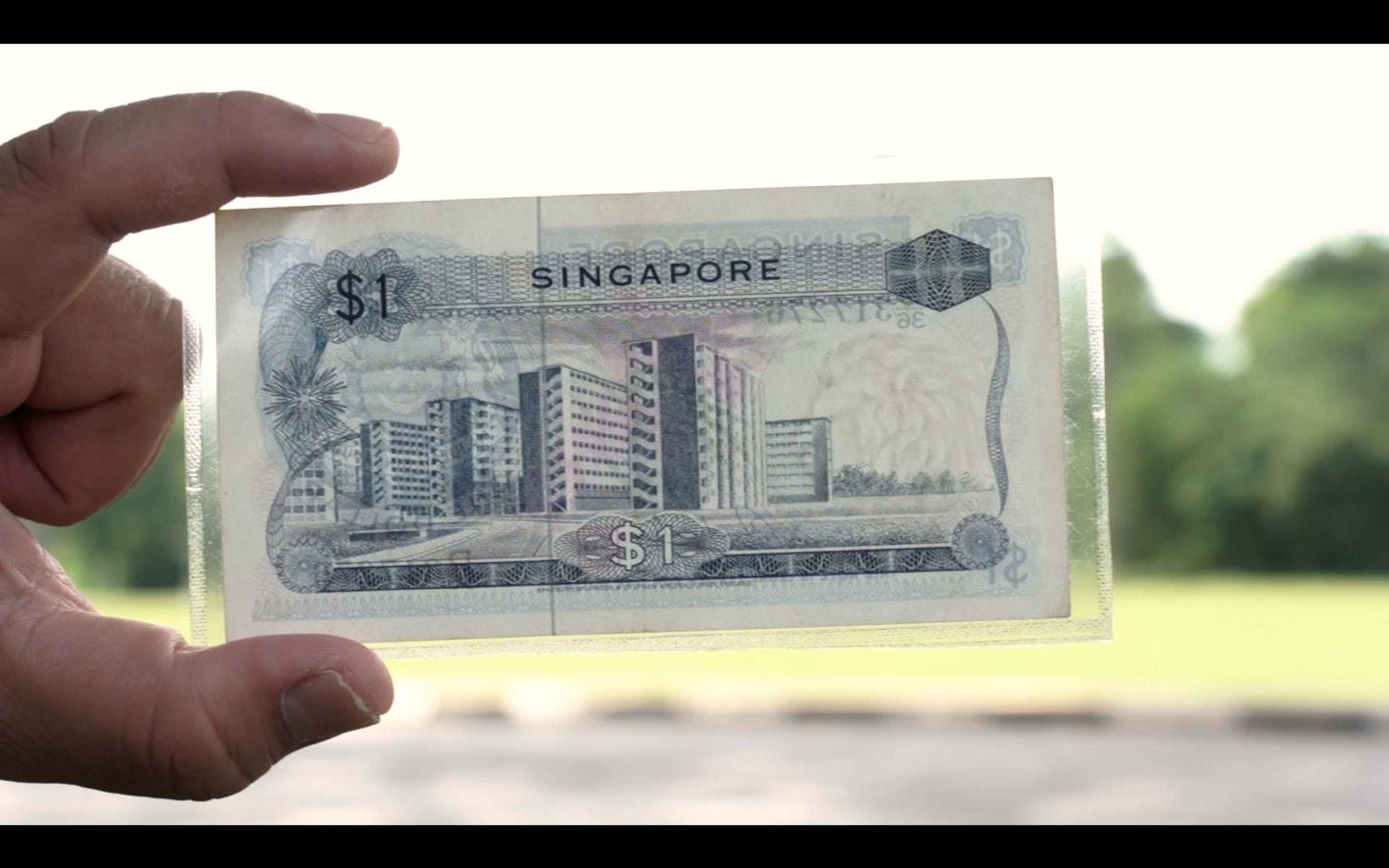

Visual artist Lucy Davis tells about the process of narrating a place and its entwinements with nature, politics, urban planning, and migration. ‘In this mulch of voices something can hatch’ discusses the politics of representation of the human and more-than-human community living in Tanglin Halt, Singapore.

Naomi and Wanda Holopainen refect on how we can shif the narratives around diversity, representation, and power in the creative industry from artistic production to collective work, education, and marketing. Naomi, Wanda, and I talk about fulflling one’s social responsibility through creative work.

Muniba Rasheed presents Subcontinental Helsinki (2023), a research into the use of typefaces by Helsinki’s Indian, Pakistani, and Nepalese restaurants to portray and convey cultural genuinity and identity. Muniba’s photographic documentation of the shopfronts mirrors how ethnic presence is self-marketed in everyday urban spaces.

In ‘Tactile connection’, designer Alejandra Alarcón and I discuss food as a contemporary design practice. While preparing salsa, Alejandra shares about cooking as a space of encounter with our surroundings. We refect on how favours and food consumption deal with traditions,

21

belonging, pride, and self-sustenance.

Amy Gelera’s bittersweet A Resistance Against Abundant Comfort seals the refections of this book around migration, the search for comfort “back home” and in one’s “new home”, and the complicity and contradictions of our practices. Amy calls out the shortcomings of Finnish educational institutions and social welfare and, with kind and sharp realism, they propose motion as a form of resistance and discomfort as an act of responsibility.

22

1. Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Borderlands: the new mestiza = La frontera (San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute, 1987), 80.

2. Havfy (Hafsat Abdullahi), ‘To the girl in English class’, YoutTube, 2022, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T2oJ5bk34-M&ab_ channel=Havfy).

3. Cesare Pavese, Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi (Torino: Guilio Einaudi Editore, 1951), 13.

4. Havfy, 2022.

5. Irit Rogof, Terra Infrma: geography’s visual culture (London: Routledge, 2022), 5.

6. Catalin Gheorghe and Mick Wilson, ‘Introduction’, Exhibitionary Acts of Political Imagination, ed. Mick Wilson and Catalin Gheorghe (Gothenburg: PARSE, Iasi: Vector, 2021), 8.

7. Art curating: the practice that coordinates, imagines, and arranges the material, intellectual, aesthetic, and personal interactions between disparate artistic works, practices, and practitioners to create a collective result (exhibition, event, public programme, etc) and communicate its framework with the audience. Curating is part of a broader teamwork of technicians, designers, educators, historians, artists, and experts in diferent felds.

8. Sara Ahmed, On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2012), 12.

9. Doreen B. Massey, For Space (United Kingdom: SAGE Publications, 2005), 6.

10. Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2011), 148.

11. Kimberle Crenshaw, ‘Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color’, Stanford Law Review 43, 6 (1991), 1241–99.

12. Ahmed 2012, 14.

13. Achille Mbembe, ‘Bodies as borders’, From the European South 4 (2019), 9-10.

14. Ibid.

15. BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, People of Colour. References on the themes of the book are by Frantz Fanon, Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Homi K. Bhabha, Irit Rogof, Ana Mendieta, among others.

23

16. Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (United Kingdom: Pluto Press, 2008), 259.

17. Ahmed 2012, 14.

18. Ingold 2021, 81.

19. Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, ‘Door handle for Casa Milà ('La Pedrera'), model 1’ (https://www.museunacional. cat/en/colleccio/door-handle-casa-mila-la-pedrera-model-1/ antoni-gaudi/214667-000).

20. Eloise Sweetman, Curatorial Feelings, ed. E. Sweetman and J. Tang (Rotterdam: Shimmer Press, 2021), 33-40.

21. Ibid.

22. Ingold 2021, 78.

23. Stavros Stavrides, Towards the City of Tresholds (United States: Common Notions, 2019), 27-36.

24. Index Teen Advisory Board and PRAKSIS Teen Advisory Board, How do we know? Institutional Listening and Young Agency in the Arts (Oslo: PRAKSIS, Stockholm: Index Foundation, Helsinki: PUBLICS, 2022), 14.

25. Ingold 2021, 145.

26. Ibid.

27. Mbembe 2019, 8.

28. COUNTERSPACE Studio, ‘Material Histories’ (https://www. counterspace-studio.com/projects/material-histories/).

29. Ingold 2021, 81.

30. Carla Gimeno Jaria, ‘What Borders Can Do’, Oncurating, ed. Hadas Kedar, 50 (2021), 91-99 (https://on-curating.org/issue-50reader/what-borders-can-do.html#.ZHXtuXYza3A).

31. Mick Wilson and Cosmin Costinaș, ‘Te Space of the exhibition as a space of political potential: a conversation with Cosmin Costinaș’, Exhibitionary Acts of Political Imagination, ed. Mick Wilson and Catalin Gheorghe (Gothenburg: PARSE and Iasi: Vector, 2021), 37.

24

I’ve discovered this humming

Francesca Bogani Amadori

Francesca Bogani Amadori

25

Francesca Bogani Amadori is a visual artist and artistic researcher based in Helsinki. Teir work looks at the (inter)dependent relation of subjects and spaces within geopolitical and sociocultural hegemonic systems. Bogani Amadori draws on the personal experience of dealing with (in)visible power dynamics through performance, walking, (re)mapping, and active listening. As a means of resistance, their diverse process-based practice focuses on attunement, being porous, volatile, and shifing by engaging in multiple directionalities and intensities. Teir work unfolds as audiovisual installations, video, photography, soundscapes, sound walks, experimental and academic writing.

On April 11, 2023, Francesca and I practised a soundrecording walk in the neighbourhood of Töölö, Helsinki, where we both have lived at diferent times. I led the walk, letting the surroundings guide my movement. Francesca followed 2 metres behind, recording the soundscape. Tis conversation took place in my fat afer the walk.

26

Francesca (F) Micol (M)

F: When we were walking together and I followed you, recording the sounds, whatever I did was double the size. Me, and you, too. It was like I had an extension, like my body was longer. It was interesting because, as the walk continued, it almost became a question of trust.

M: I was guiding you into my way of seeing the city.

F: It became quite intimate. When you share an experience, you always add a layer to your thinking. It's interesting also that, as I try to draw a map of the frst part of our walk, I have a big gap ... I’m clueless.

M: Why is that?

F: Because I was trying to be invisible. Since I was mimicking you or dealing with your way of navigating the city, the movement didn’t come from me. Now I’m trying to remember, rather than having it from within.

27

M: Does it happen also when you do soundwalks by yourself?

F: Not really… It is by default that our body circulates in a certain way.

M: I was making choices, defnitely. At one point, it felt like I was trying to chase away from things rather than moving forwards. I was trying to get to quieter places.

F: Exactly. When I moved here, I perceived the city as silent. But when I started recording and walking, I discovered this humming: a lot of this “mhhh”, a lot of ... not, white noise ... but a lot of “kchukchukchu”, and soooo many engines.

M: It’s a body that moves, the city. I mean, comparing cities to bodies is quite common, but Helsinki really makes its own sound.

F: It isn’t people – it’s these machines.

M: As if it had joints that crack.

28

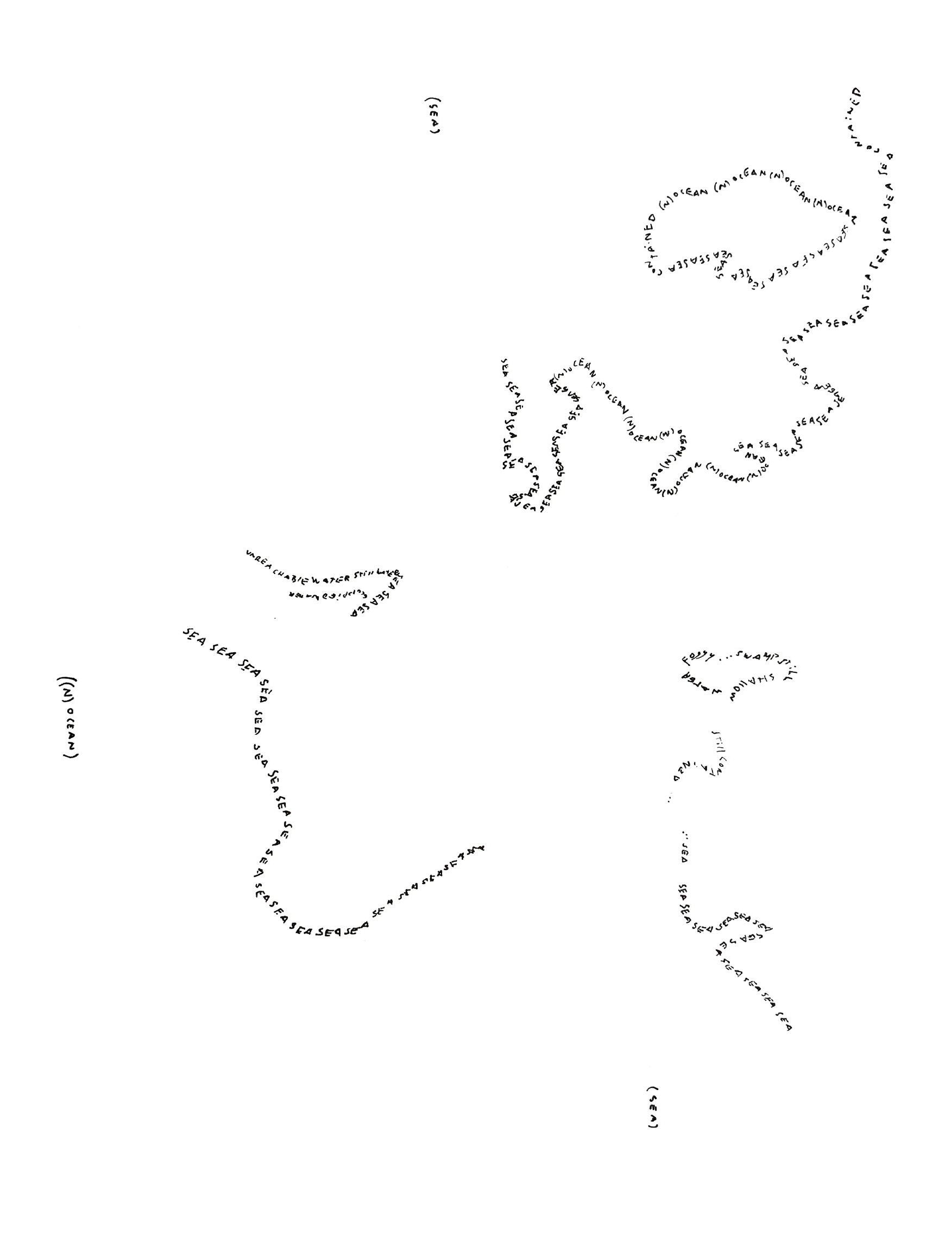

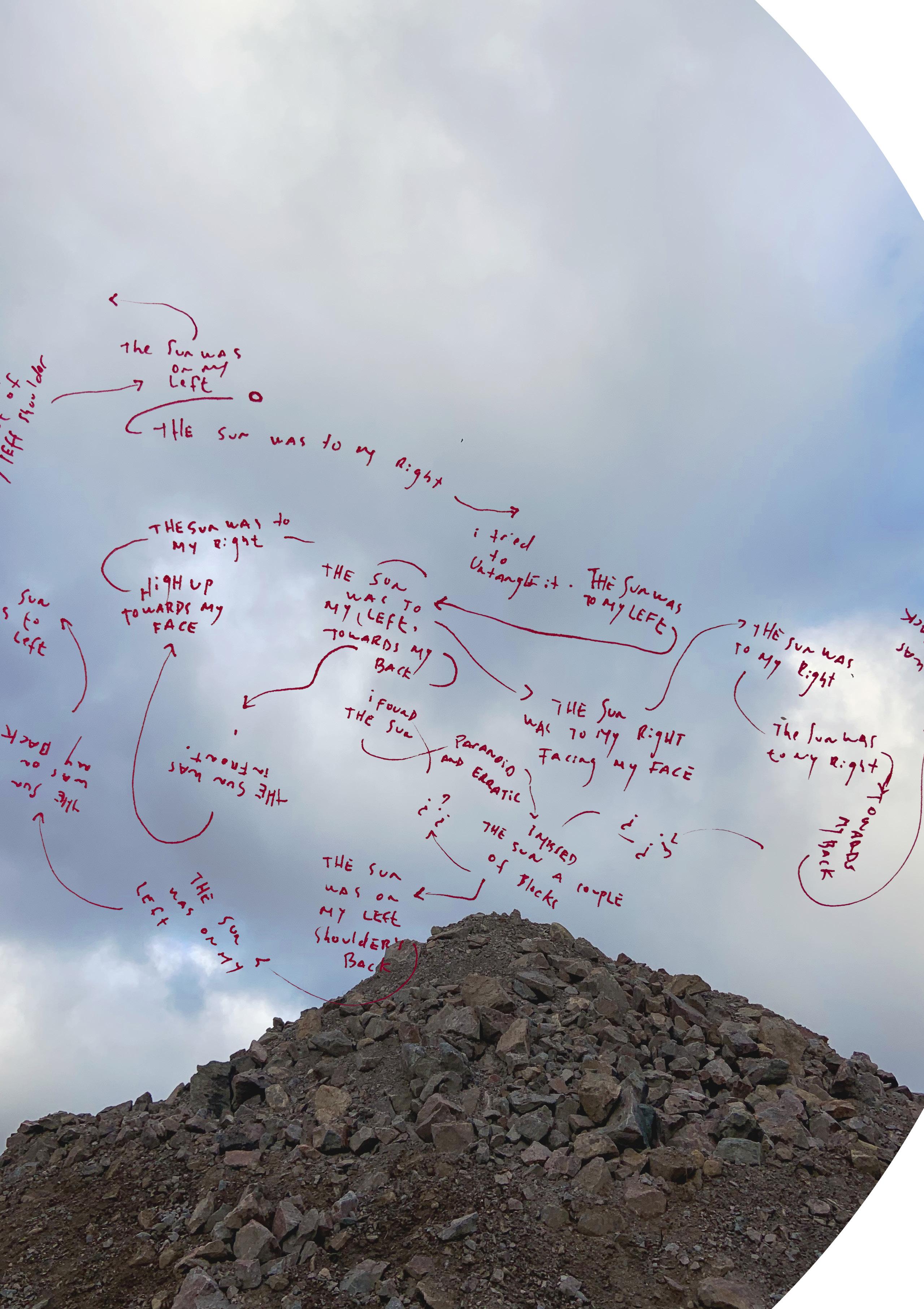

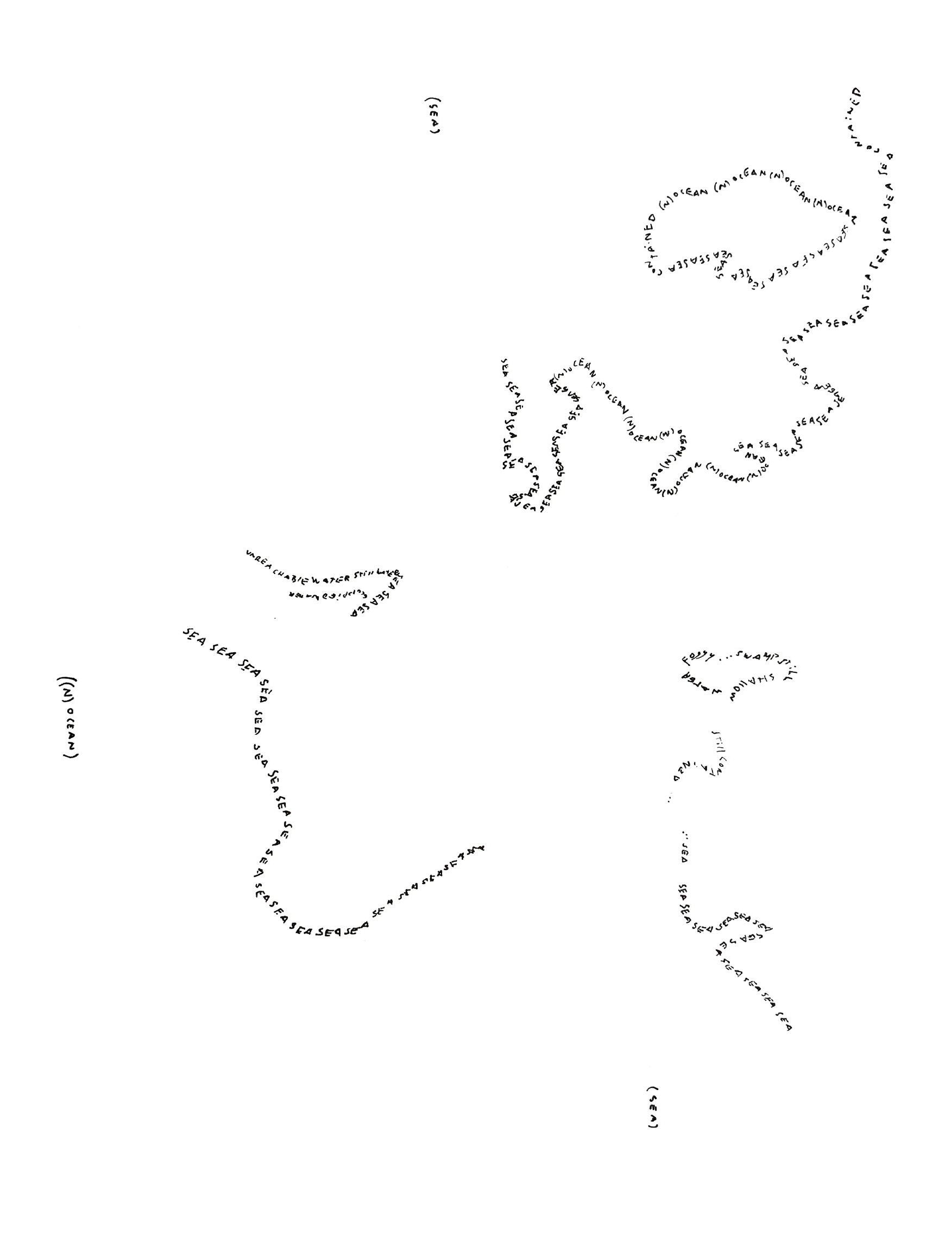

Francesca Bogani Amadori, Tracing (n)ocean.

Walk-Listening mapping practice, 2023, Helsinki. Digitalized maps, variable dimensions.

M: Should we try to draw the map? ... Now I’m confused. I think Helsinki looked a bit diferent today. I don’t know, maybe it’s the season.

F: Seasons afect a lot. Te thing with the summer is performativity. Summer grants you permission to be outside doing nothing; you are allowed to wander, to just lay on the ground. You’re allowed to be.

M: Today, I felt like a visitor. One could hear so much: the trains and the trams on the farthest horizon. Listening, I could hear these nodes of movement which the city is organised around. Afer two years, I still sense that it isn’t mine, the city. I’m not uncomfortable, I don’t feel out of place, but I still relive the experience of seeing Helsinki for the frst time. Tere’s something almost reassuring knowing that, when I need a break, I can go out and perceive the city as if it doesn’t quite belong to me. To be honest, it almost doesn’t belong to anyone. Do you know what I mean?

F: Yes, it’s hard to make the outside yours, because the public is also always privatised. It’s transitory. And everything else is enclosed: all your livelihood is within.

M: Would you say that this is diferent in Lima?

30

F: Te city is more hostile, defnitely more chaotic. But the spaces feel more taken by the public. I couldn’t walk safely or at ease in many places in Lima. So when I came to Helsinki, I was “Oh, walking!” Tat changed my perception of here and the scale of here. Navigating the city of Lima was most likely by car. Somehow, here, the city feels so tiny that I feel like falling out of its edges. While there, walking, the city would feel massive. Lacking the car and walking in Helsinki has made me perceive space on another scale. I rely more on my own size.

M: Is the way you look more visible in Helsinki?

F: Well, certain bodies gather diferent types of attention than others. In Lima, one comes across many intentions; you know, catcalling, angry glares that might indicate a risk ... People in the daily context are defensive. You receive neutral stares or random smiles, some intruding, some sympathetic. Here is diferent. Tere are other sorts of microaggressions or gazes. It’s the other side of the coin. Yet, at the same time, I’m invisible here. I don’t know if that’s better or worse, but I’ve been playing with that. I don’t think I would have managed to become invisible at home. Here, sound recording has allowed me to be in places more easily because it grants me an occupation.

31

F: One day, I was walking for a whole hour in Kamppi station. Walking and walking and walking. I knew someone was going to come. Tey came. But it took a while; it took an hour.

M: Te security came?

F: Yes, of course. But it took one hour, and I was questioning: if I had looked diferently, how long would it have taken? Before that, they approached other people. Way earlier. Tey were just sitting around; while I was walking in circles and coming up and down the escalator for a whole hour. One hour later, they came.

M: It’s a question of when we become accessible to others ... Te street holds a diferent status.

F: For that reason, at frst, it was hard to be outside, walk, and stroll. Right now, I’m not making dérive work1. I’m walking with the purpose of understanding myself in this space, but even that is privileged.

1Dérive (French “drift”) is a practice of walking in the urban environment established in the 1950s by the Situationist movement and formulated in Guy Debord’s Theory of the Dérive (1958). Practising la dérive, one wanders through the city being guided by emotions and personal experiences connected to the space (Psychogeography) rather than by functional, productive, or normative logics.

32

33

and modular audio.

34

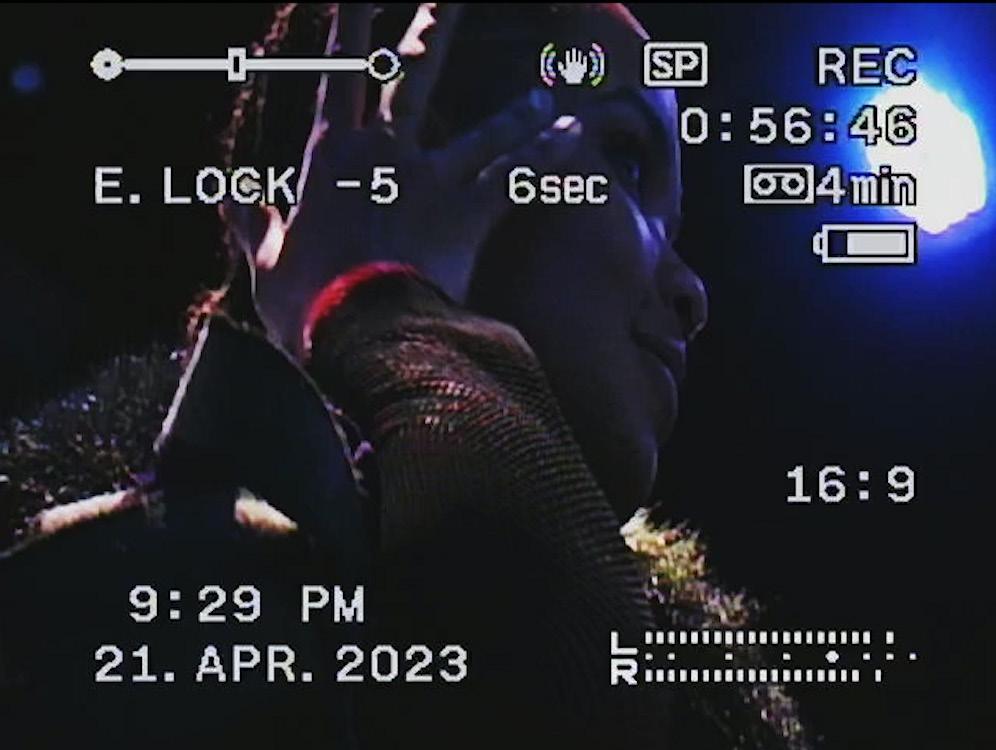

Francesca Bogani Amadori, Making-here: Embodied Memory. Walk performance, 2022, Helsinki. Video documentation: Henry Lämsä. Post-production by Francesca Bogani Amadori. Field recordings in Lima and Helsinki (2022 - 2023)

M: Have you ever tried to be still in a place?

F: Tat isn’t for me, I think.

[Francesca laughs.]

M: When we walked past the playground, I was thinking about how we as a society need to make a place where one’s allowed to stay and do nothing ... Well, playing isn’t “doing nothing”, but you know what I mean ... Tere, you’re allowed to linger.

Why is walking easier for you?

F: It helps me think, and it unlocks things that are carried in my body. It was hard for me today to walk at a diferent pace – yours – because I still carry this memory of how to walk in a faster city. I still have this defensive mode ... Tat’s why I walk: because I untangle a lot of “back home” and this “new home”. It needs to be in the space, by walking rather than just sitting. I’ve been playing with that in terms of making home.

M: How does it feel to “feel at home”?

F: Sometimes, it’s a made-up feeling. I can look for the elements that, in my memory, remind me of home: water and wind. Sometimes, it’s when I don’t notice what I’m doing; whenever things just happen or the city disappears. Like breathing! Sometimes, being noticed makes me

35

realise I’m not at home; sometimes, being too invisible makes me realise I’m not at home.

M: Do you feel at home in Lima?

F: Here in Helsinki, I feel at home on a bigger spectrum in the sense that I can be in the extension of a city, whereas there I cannot. I feel limited. In Lima, I inhabit areas; most of them are private. So my idea of the city is narrowed down to specifc districts. Access to what I’m doing right now, like recording soundscapes, would have to be mostly in private areas for safety reasons. I cannot cover as much space. Maybe not knowing, not being aware of certain layers, is granting me this “security” here. So far, being an outsider has allowed me to, at least, reach further than I would have been able back at home. Probably, being an outsider there would have gotten me in trouble.

M: Do you think that the moment will come when you would feel not an outsider?

F: No. Do you?

M: I don’t know. Right now, my life travels on a parallel layer of relations that I’ve imposed above the city.

F: I get that.

36

M: It is a strange position to be in.

F: A superfcial fow, like smoke. I thought I wasn’t in this transit mode anymore, but I think I still am. I’m still foating; I’m not rooting.

M: Floating is a good image. One is allowed to build this foating platform that stands above the centre. Of course, this is already a privilege.

F: Tat’s the thing: there is the possibility of being invisible, if you want, by having this extra layer. At some point, I was playing with that, and then I said, “No.”

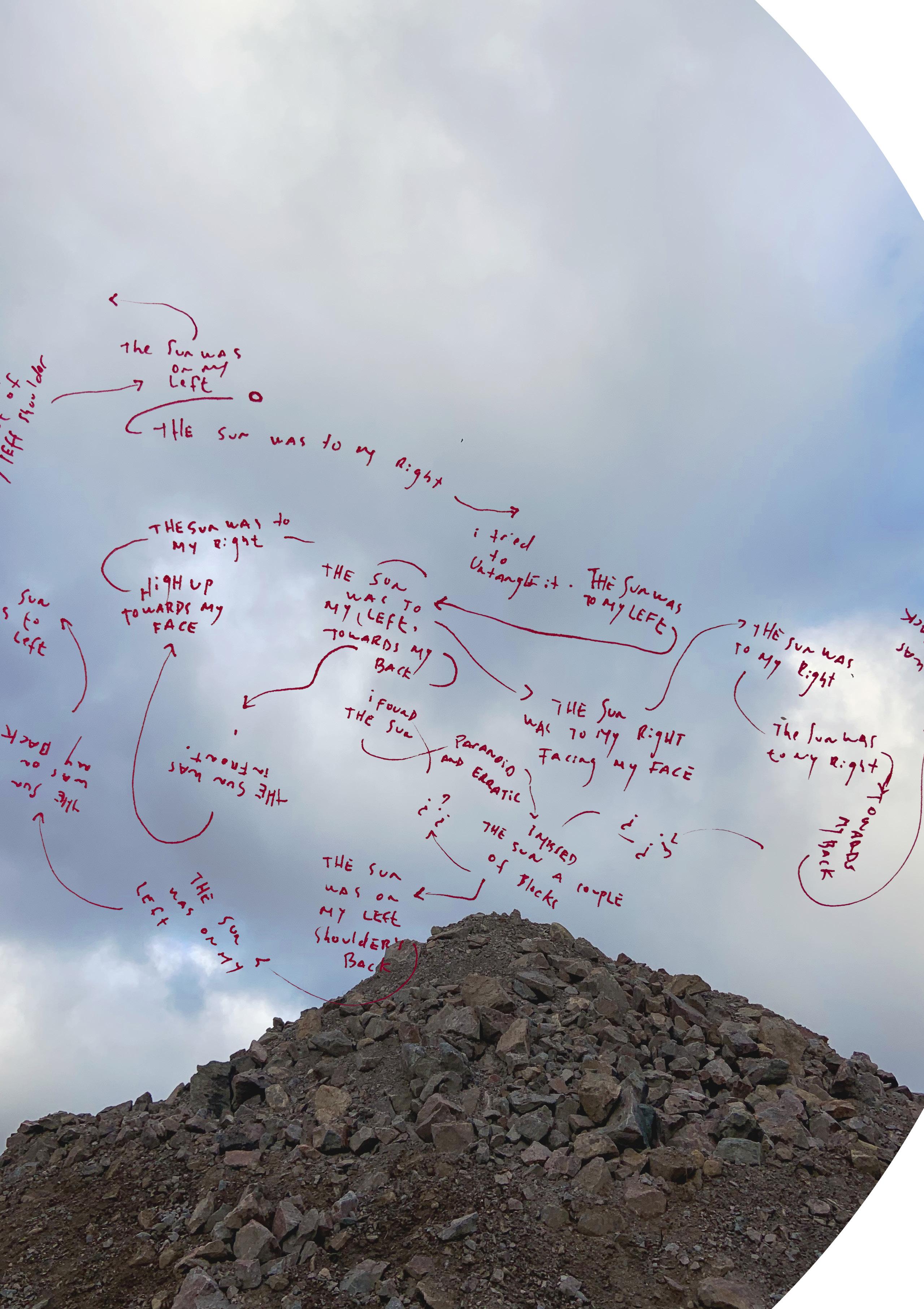

Francesca Bogani Amadori, Un/tangled mapping horizons. Walk-Listening mapping practice, 2022, Helsinki. Mixed media collage, variable dimensions. ^

37

1. Dérive (French “drif”) is a practice of walking in the urban environment established in the 1950s by the Situationist movement and formulated in Guy Debord’s Teory of the Dérive (1958). Practising la dérive, one wanders through the city being guided by emotions and personal experiences connected to the space (Psychogeography) rather than by functional, productive, or normative logics.

39

40

Museum Property

Lotta Hagelin

Lotta Hagelin is currently studying Visual Communication Design at Aalto University and has a Bachelor’s degree in Arts. Her work focuses on issues related to the Sámi people by being active at the street level, participating in Sámi organisations, and providing an indigenous voice to the youth-led NGO Operaatio Arktis.

41

Lotta:

Museum Property (2023) is a collection of works about the feeling of putting on a gákti, Sámi dress, in the urban environment. Just wearing a gákti in the streets brings a sense of forced performance. One is being observed, photographed, stared at – as if we were museum objects. With this project, I have wanted to create a moment when we can face these gazes on our own terms. To explore the unpleasant feeling together and examine how we, even when being objectifed, could be in control of that dynamic.

As the Finnish National Museum has provided the museum equipment for this project, with my work, I want to take a stand on the politics of museums in relation to the possession of Sámi objects and the representation of the Sámi and Sámi culture created by art institutions. Although the Finnish National Museum has a history of possessing Sámi property, today, the museum has been a major player in contributing to the Sámi people’s right to their own cultural heritage and is leading the way in the global repatriation discourse as it has completed the repatriation process and handed over its Sámi collection to the Sámi Museum Siida in Inari, Sápmi.

42

Lotta Hagelin, Aarni, Seen, series ‘Museum Property’, 2023, digital photograph.

Lotta Hagelin, Biret-Iŋgá, Noticed, series ‘Museum Property’, 2023, digital photograph.

Lotta Hagelin, Biret-Iŋgá, Noticed, series ‘Museum Property’, 2023, digital photograph.

Lotta Hagelin, Helmi, Spotted, series ‘Museum Property’, 2023, digital photograph.

Lotta Hagelin, Helmi, Spotted, series ‘Museum Property’, 2023, digital photograph.

Lotta Hagelin, Museum, Discovered, series ‘Museum Property’, 2023, digital photograph.

46

One plus one becomes three

Impropias Collective

47

Impropias Collective researches Latin American identities from an embodied, situated, and feminist standpoint. In Spanish, “impropia” is the female form for inappropriate, for something inadequate or untimely. It is also a play of words between “improvisation” and “propio”, which means cool and street-smart in Ecuadorian slang. Te collective was founded by Mercedes Balarezo Fernández, Yes Escobar, Paola Nieto Paredes, and Daniela Pascual Esparza in 2021. cuerpalatina is their frst collaboration.

Mercedes, Yes, Paola, Daniela, and I met at Humina Association in Länsi-Pasila, Helsinki, on March 14, 2023. I joined Impropias for their rehearsals. Te three tasks that follow this conversation were produced afer our meeting, answering this prompt:

How does your experience of space and movement during the performance cuerpalatina relate to threshold elements?

By threshold, I imagine an element (physical, visual, expressive, organic, conceptual, etc.) that separates and connects spaces and is defned by movement. A threshold can be:

◊ an aperture by moving across it,

◊ a contact zone by moving towards it or gathering around it,

◊ a space to inhabit by lingering on it, or

◊ a device to control interaction.

48

Mercedes, Yes, Paola, Daniela, and Micol

Paola: How does one invite people to dance?

Mercedes: “Would you attune with me?”

Impropias Collective, cuerpalatina, Y-festivaali by the Ministry of Justice, October 2022, Helsinki. Images courtesy of Y-festivaali.

49

Micol: While we were dancing together, you all were at the perimeter of my sight. Te room got smaller because we were defning the space. Maybe the centre wasn’t one of us but somewhere between us.

Rehearsing seemed almost like a quest for an internal movement, which slowly gets analysed through the body. As it gets out, it starts to fnd a connection, and then there seems to be a conscious decision to open this movement to others.

Yes: More than movement, I think we’re trying to paint certain landscapes.

Micol: Achille Mbembe writes about the idea of ‘re-membering,’1 which resonates with what you, Mercedes, were saying about deconstructing movement: centres, patterns and energies; the connection between memory and the analysis of its motion.

Mercedes: Yes, there’s a lot of bodily memory that comes from the music, or the music comes from bodily memory.

Paola: In one part of my scores, I used music that brought me back to the image of being in Mexico City, in the market, on the bus, to how my body feels in that space, adapting those feelings to the

50

context and the site of the performance.

Mercedes: Because the music visits us again, this re-membering is like re-building memory in your limbs. Tings overlap; the old memory and the reconfguration of the dance, the people we are here now in this country, and the people we were in our childhood.

Micol: Tere’s a relation to identity and urban spaces, at least in your [Paola’s] memory: the idea that we move diferently in diferent cities.

Impropias Collective, cuerpalatina, FOE Fest, July 2021, Helsinki. Co-funded by Taiteen Edistämiskeskus/ The Arts Promotion Centre Finland. Photos by Vitali Gusatinsky.

51

Mercedes: It has been at the forefront from the beginning: what is it to be a “Latin person”? Where does this “Latinity” lie? What are the things that we want to associate with it?

Daniela: Our cultural heritage is what we can bring forth, explore and experiment with; it’s been our common ground. Te experience of “being away” is something that we deal with every day. It has been the starting point and the channel. But I think that, eventually, the project is a lot about dancing together, about what it takes to get people to dance, and how to promote dance and conviviality. Of course, having had that experience growing up, that dance was not something extraordinary but everyday, this cultural heritage has shaped our corporeality and how we experience the world.

A big part is about identity, yes, but cuerpalatina goes beyond that and is perhaps about something else ... or something more than that. Like, when one plus one becomes three.

I always go back to myself dancing in the kitchen. I think about what Mercedes says, “You cannot share what you don’t have.” How to embrace identity without being trapped in it.

Afer the performance at Svenska Teatern, I went to an actual party where people were sweating

52

and dancing, and you couldn’t see where the centre was, and you were all part of the same body. I would like the performance to feel like that, like: “What the hell is going on!”

Paola: We want a big party!

Mercedes: Yeah, we have a very clear goal: we want people to party. Maybe it’s a memory of our own experiences; when there is a great party, everybody loses themselves in the movement, “I

53

Impropias Collective, cuerpalatina, the New Theatre Helsinki Festival at the Svenska Theatre, February 2023, Helsinki. Photos by New Theatre Helsinki and Quentin Wachter.

don’t know if you’re my friend or not, but we are together! Eah, eah!”

When bodies dance together, the hierarchies change too. Of course, social constraints are still present, but something is stated when we’re in relation to someone else dancing. It’s what we’ve just experienced: this attunement. Suddenly, I experience the person next to me move so freely, and I start to move a little freer too. It isn’t even a conscious decision, but the body starts to speak its own language.

Micol: I felt that at the theatre, you were playing with infrastructures. I have started reading Gloria Anzaldúa’s writings, her concept of la mestiza being a mediator, reclaiming a zone that allows them to tap into diferent worlds.2 Te way you used the space of the theatre was allowing you to walk on this border line between structures: between the stage and the audience, or between the upper and lower side. Redrawing spaces. Maybe it relates to what Daniela was saying, that it isn’t only about identity but more about interaction and drawing contact. How can this expand to spaces, too?

54

55

Impropias Collective, cuerpalatina, FOE Fest, July 2021, Helsinki. Co-funded by Taiteen Edistämiskeskus/ The Arts Promotion Centre Finland. Photos by Vitali Gusatinsky.

56

Paola: Te space is a character in itself.

Yes: We like to occupy the location. We are also deconstructing how spaces are being used. We take over in a way that goes from uncomfortable to less uncomfortable to hopefully togetherness. We will never be on stage unless it’s with the audience.

Daniela: And when I don’t know what to do with the space, I play with it as if there was another body. When I have to perform, I might as well let certain parts of my bodily way of being go from the private to the public. Tat ofen becomes a threshold in the performance for me.

57

Yes Escobar,

A somatic exercise for the exploration of quality over shape

You need at least two people for the exploration. Before the exercise, gather one or many some-things that embody the following

qualities:

◊ Hard ◊ Sof ◊ Liquid ◊ A smell you like ◊ Cold ◊ Tasty

58

Somatic exploration

Read the following instructions in any given order. Change the reader afer each round.

Gather all your somethings around you. Close your eyes. When coming into contact with your somethings, try to focus on the sense of touch as your only means of understanding. Sometimes, you will be invited to share this experience in the form of movement. Try to relate the movement to the knowledge acquired/activated/ remembered by the experience. Now, close your eyes.

Exploration instructions

If you can, pick up something hard. Press your fngers around it. What is the texture like? If you can, press your chest against it. Feel it there for a little while.

Make contact with the liquid. Can you touch it with your fngers? What temperature is it? Does it have a smell? Can it move? In which ways? Is it good to drink? How do you know?

Move to express knowledge

Find something to eat. Give it a nice bite. How does it feel?

Touch something sof and something hard at the same time. Why did you think these somethings represent antonyms?

Move to express knowledge

Keep something sof in contact with you from now on and until the end of the exploration.

Find something that smells nice. How can you best sense the smell? Is it better to be close or far away from its source? How can you know where the smell comes from?

Move to express knowledge

Put one foot on something cold. Now, the other foot. Now, one palm, try closing the palm. Now, repeat on the other hand. Keep it there until you cannot handle the cold sensation.

Move to express knowledge

Take something sof away from you.

Find something to eat. What does it feel like? How can you know this is food? Take the food close to your nose and open your mouth just a little bit. Press your nose against it if you can.

Take something sof away from you.

60

Daniela Pascual Esparza,

El Ave del Paraíso Blanca

El Ave del Paraíso Blanca es una planta oriunda de África del Sur. Sus hojas se parecen a las del banano y es fácil confundirlas: ambas son lisas, grandes, y fuertes. Y sin embargo, el aire las acaricia hasta partirlas. Yo las miro moverse en las alturas, me siento alegre, ligera, y pienso en estos versos de Rubén Bonifaz Nuño:

te lo abrán dicho ya, que nadie muere de ausencia, que se olvida, que un lamento se repara con otro, y es el viento o la raya en el agua que se hiere.

Y así, una hoja se convierte en pluma, de una fsura nace un movimiento, y mi cuerpo descubre nuevas formas y texturas; el sonido de la lluvia.

The White Bird of Paradise is a plant native to South Africa. Its leaves remind those of banana trees, and it’s easy to mistake them: both are big, smooth, and strong. And yet, the wind caresses them until it breaks them. I look at them move high above, feeling light, feeling joy, and recall the words of Mexican poet Rubén Bonifaz Nuño:

te lo abrán dicho ya, que nadie muere de ausencia, que se olvida, que un lamento se repara con otro, y es el viento o la raya en el agua que se hiere.

And just like that, a leaf becomes a bird, a crack invents a movement, and my body discovers new textures, new shapes; the sound of rain.

Cuando camino y todo está quieto, y lo único que escucho es el caucho de mis botas pisando la nieve, me inunda un recuerdo falso, inventado, de una fnca en Babahoyo, platanares por doquier, y el sol abriéndome la piel. El aire denso y húmedo derrite mis toxinas, mi cuerpo se expande, y así, mientras el frío arruga mi piel y me siento ajena al milagro de este paisaje, repito: que el desapego no me impida apreciar la belleza que aquí habita, que el desapego no me impida apreciar la belleza que aquí habita. Camino, me despliego, y por un momento me siento cerca de mi abuelo, de la guanábana que crece en el patio, de mi abuela convertida en pájaro, de aquel río que yo también crucé en balsa. ¿Qué miras tú cuando me ves bailar? Yo a veces lloro sin llorar, y otras dejo que me atreviese un rayo de luna, que me habiten todas las vidas no vividas, un Mapalé colombiano, el polvo de la calle, un dembow, el cóndor de los Andes, un balcón en primavera y Quilapayún. Cada poro de mi piel es un umbral y todos los días una tarde de domingo: un instante en el que tú y yo nos podemos encontrar, bailar quizás.

When I walk and everything stands still, and the only sound I hear is the rubber of my boots against the snow, I’m invaded by a false memory, an invented memory of a fnca in Babahoyo, banana trees everywhere, the sun piercing my skin. The air there is thick and humid. I feel myself melting. I expand and so, as the cold wrinkles my skin and I feel foreign to the forest and the miracles around me, I repeat: may indiference not prevent me from acknowledging the beauty of this place, may indiference not prevent me from acknowledging the beauty of this place. I keep walking, I unfold and, for a moment, I’m near my grandfather and the soursop tree in his garden, near my grandmother who’s now a bird, and by that river, I, too, have crossed. What do you see when you watch me dance? Sometimes I cry without tears, and other times I welcome the moonlight, lives I’ve never lived, a Colombian Mapalé, the dust from the street, a dembow song, the Andean Condor, a balcony in Spring, Quilapayún. Every pore in my skin is a threshold and every day a Sunday afternoon: the chance for you and I to meet, perhaps to dance.

63

64

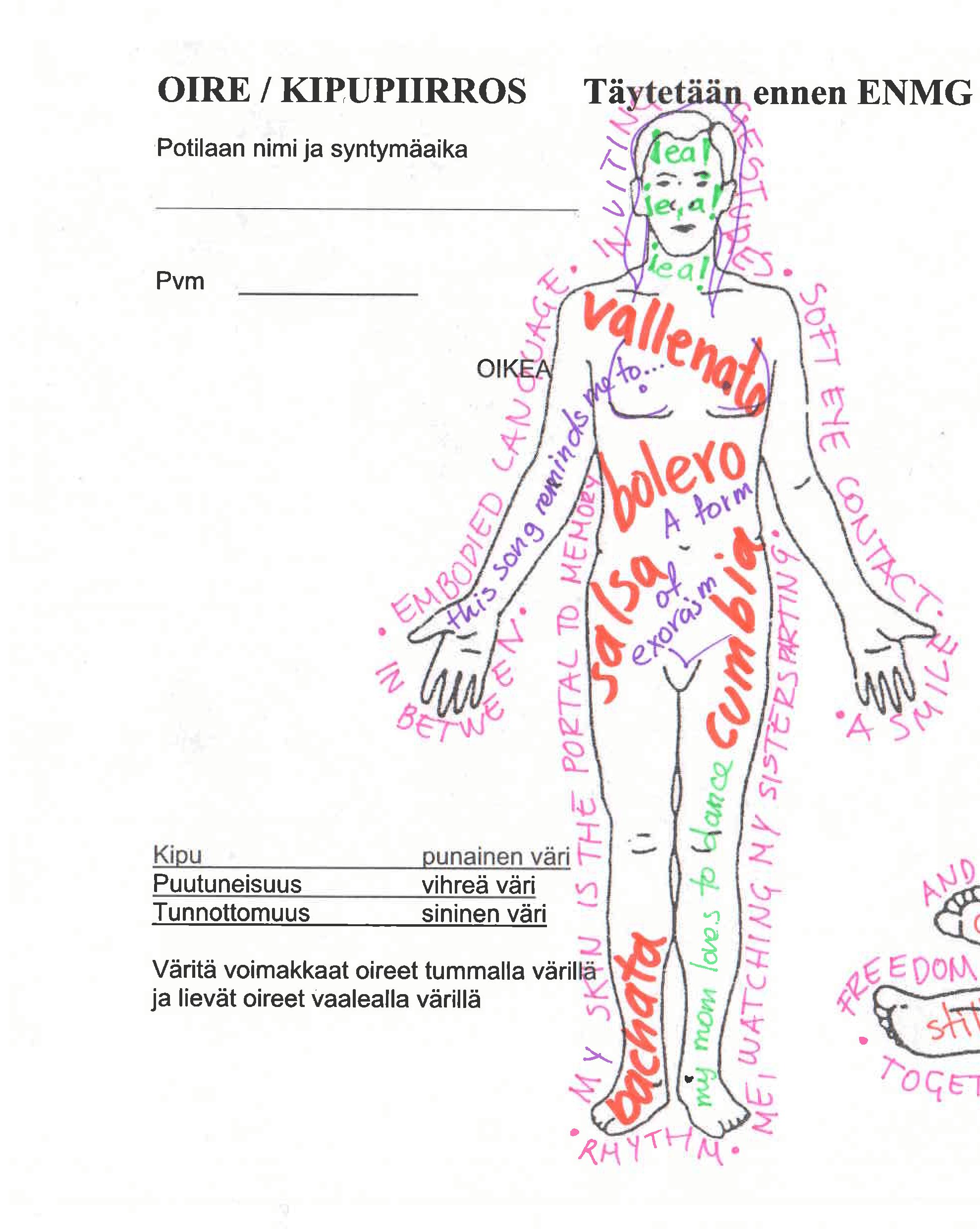

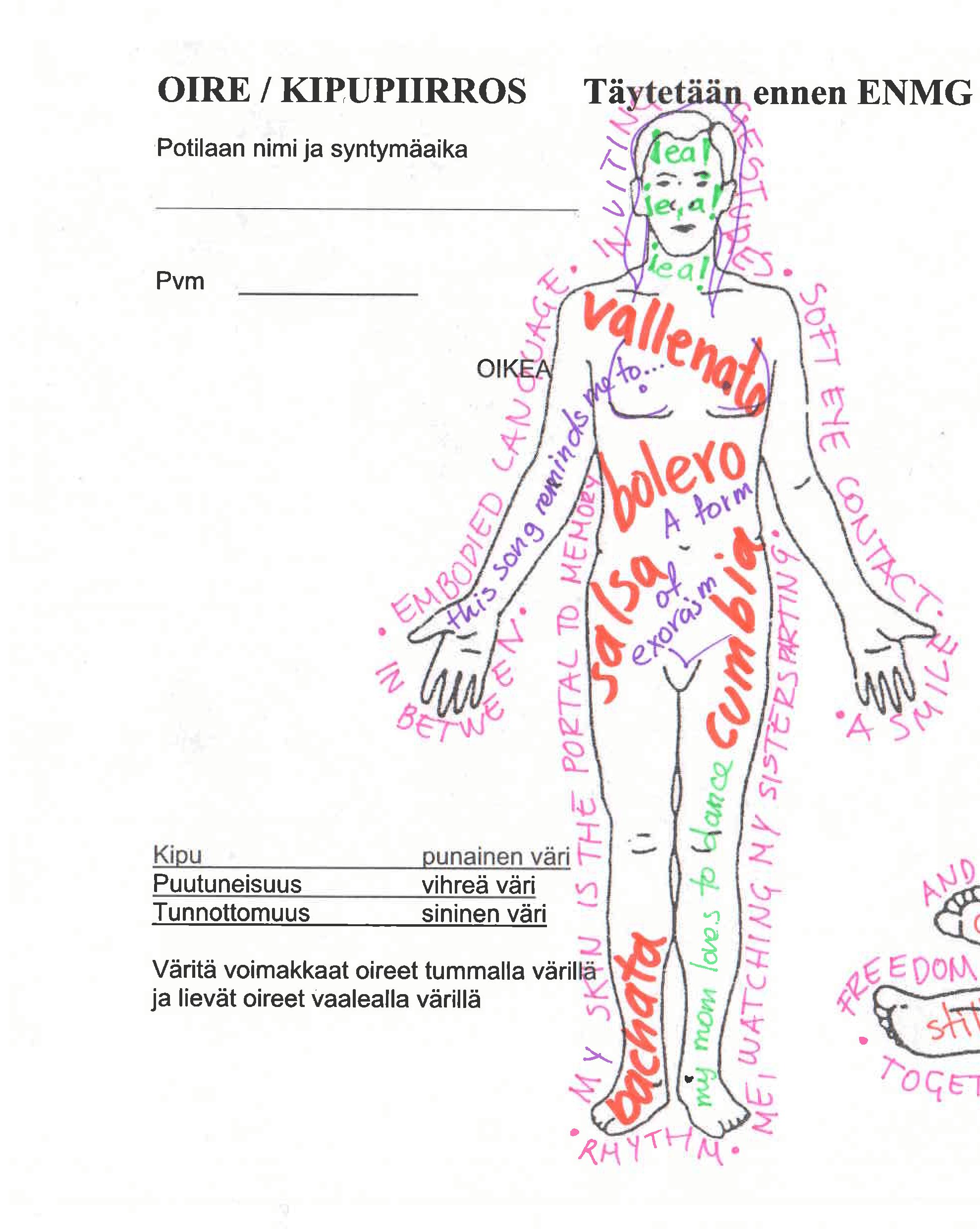

Mercedes Balarezo Fernández, Mapa del cuerpo, 2023, sketch.

1. Achille Mbembe, ‘Bodies as borders’, From the European South 4 (2019).

2. Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Borderlands: the new mestiza = La frontera (San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute, 1987).

65

66

Trying not to build walls

Eliisa Suvanto, Porin kulttuurisäätö

67

Eliisa Suvanto is a curator-producer and one of the founding members of Porin kulttuurisäätö, an awardwinning collective combining artistic research, production, and curatorial work. In addition to annual exhibitions and events, the collective produces public talks, consultancy, studio visits, and political advocacy work. Previously, Eliisa has worked as the director of the artist-led space Titanik in Turku and as programme manager of PUBLICS in Helsinki.

Tis conversation was compiled in diferent moments, through written and spoken dialogue, in December 2023. Eliisa and I worked together in other instances, while I was introduced to Porin kulttuurisäätö’s work through their exhibitions Evergreen Inner Jungle (2021) at Kaisaniemi Botanic Garden, Helsinki, and #Holiday365 (2023) in Sotkamo, Kainuu.

68

Eliisa (E) Micol (M)

E: Porin kulttuurisäätö and Space Invaders were born under diferent circumstances but back to back, driven by the need to actualise something concrete, to put the theory into practice, so to say. We wanted to bring visibility to a programme (the MA in Visual Cultures, Aalto University, at the time based in Pori), which addressed questions – for example, thinking about the public space – that weren’t as common in the cultural practices of the time. Since 2013, the projects have grown into platforms where our collective practice manifests strongly.1

Porin kulttuurisäätö, an “imaginary foundation” (in Finnish ‘säätiö’, but in this case missing one letter, which then translates into ‘hustle’), and what was built around it, we considered to be “the work of art”. Tat is, what we were able to collectively produce by using the so-called foundation as a platform.

1 The frst ever Porin kulttuurisäätö project, The Sponsor, was realised with a one time working group (Anna Jensen, Niilo Rinne, Eliisa Suvanto, Eetu Henttonen and Anni Venäläinen) all connected to Aalto’s MA program. Since then Jensen, Suvanto and Venäläinen continued Porin kulttuurisäätö as a collective working on site-specifc practices. In 2024, Porin kultuurisäätö consists of Jensen, Suvanto and Sanna Ritvanen, who joined the group in 2020.

69

[We laugh.]

M: Okay, this connotation of “the work of art” is interesting, maybe a bit counterintuitive to its conventional meaning. Isn’t it something that you’ll need to explain?

E: Do I?

I'm going to stop you right there. You can think of it as a gesture implying that there are multiple people, multiple voices in our projects, and collective moments of discussion and mutual impact along the way. It suggests that roles can be muddy and that all the elements in this picture – the location, the bureaucratic structures, the artists, the possible hosts, ourselves, etc. – are equal actors.

We work with site-specifc research questions, mainly commissioning artworks that respond or react to these terms, and collectively with artists and other professionals who create resonance on an individual level and the project at large. Te exhibition always shifs in unexpected directions. [Eliisa smiles.]

70

Michaela Casková, Small Talk #9 Walking through, taking in, soaking up and again. Porin kulttuurisäätö, Pori Biennale Visitors , 2022. Rastila, Helsinki, Finland.

Photo credits: Erno-Erik Raitanen.

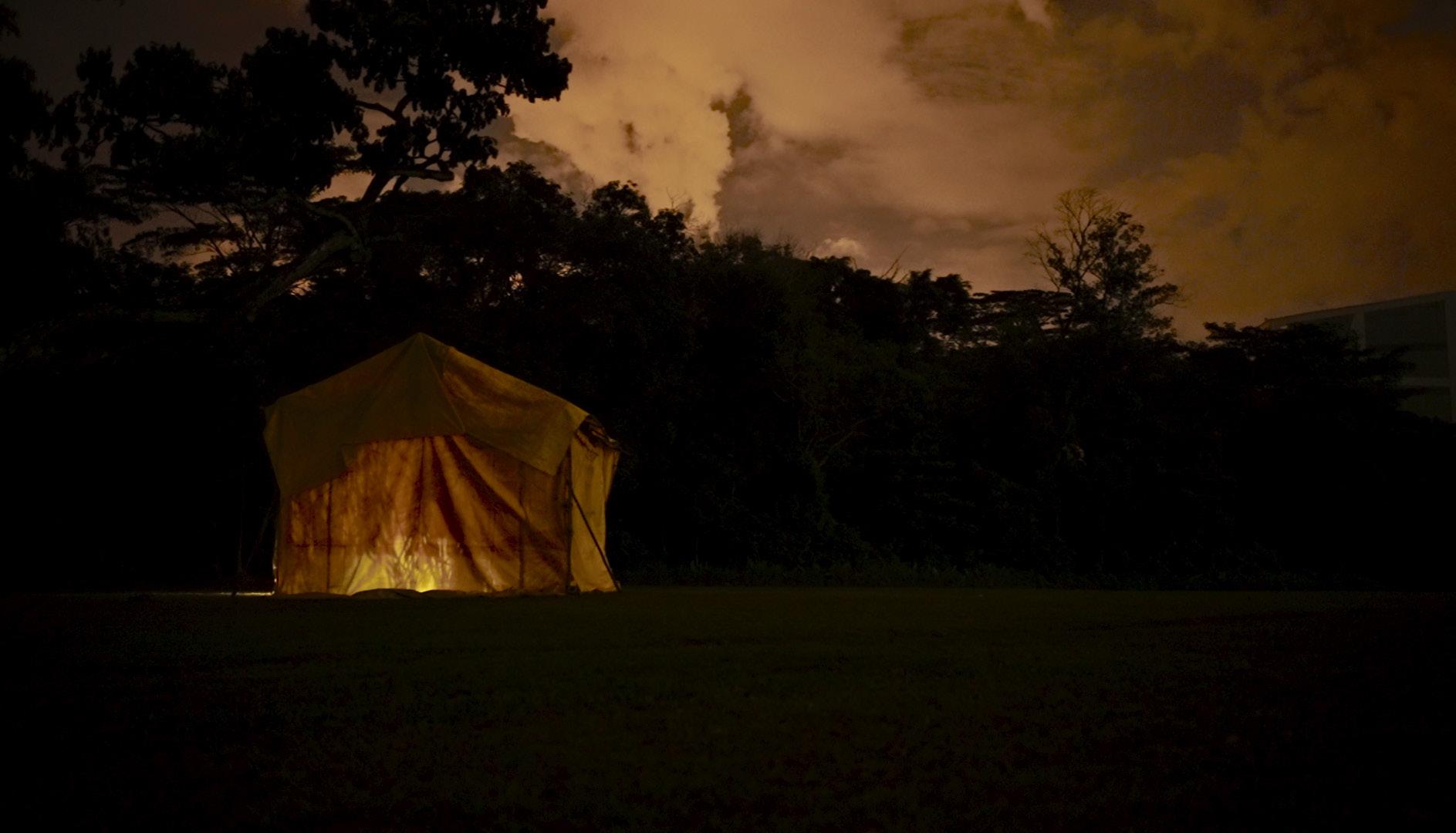

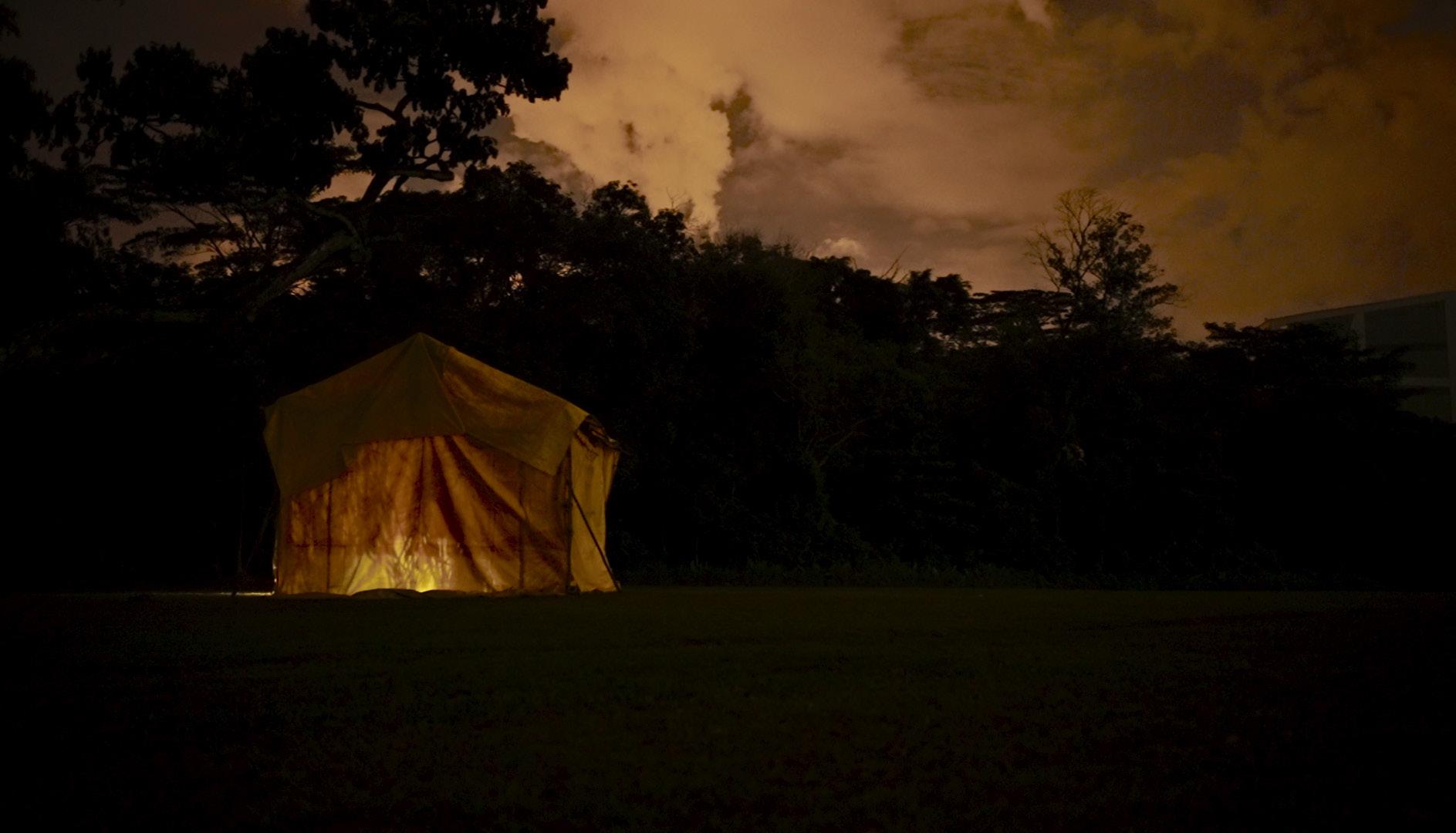

E: One recent example is Pori Biennale Visitors (2022) in Eastern Helsinki, where the original location was the vast natural area of Kallahdenniemi. Artist Michaela Cascová wanted to include the Rastila camping site, expanding the exhibition both physically and thematically. In the end, an artwork by Venla Helenius was shown at the camping site, too. Te exhibition continued in the suburb of Meri-Rastila, where Kaija Hinkula’s work was installed, moving through the local nature with forests, beaches, peaks, and meadows. Te concept of “work of art” involves the agency of the exhibition’s sites too, which can be multiple within one project. Te site is never a backdrop but a crucial element, communicating with the artworks and to the visitors, and vice versa.

M: Porin kulttuurisäätö and Space Invaders seem to hold an insistence on work, “the hustle”, of squatting a format or a structure. Whether it is hijacking the format of a foundation or literally squatting an empty place, to me, this seems to pursue a certain way of working more than establishing a stable entity.

E: Yes, they indicate the taking over a physical space or an idea. Ofen, in the process of fnding potential in a new site, we work with one further collaborator – beyond the artists and our working group – which brings its own agenda

72

and activities, being potentially other than art making: for example, Kaisaniemi Botanic Garden in Evergreen Inner Jungle (2021). All our projects try to facilitate the knowledge or activities already existing at the site, while adding another layer. Also, we’ve never returned to the same site twice.

M: Isn’t that a form of resistance? It sounds exhausting ...

[Eliisa laughs.]

E: It is. It is.

M: My question was also pointing at funding systems. Maybe directing the focus on how you work, rather than having a fxed homebase, allows you to work around these norms too?

E: Yes, but there are pros and cons. How interesting and difcult it is to “sell”, so to say, a way of working as your practice. How to put a “label” to this fuid collaborative work across multiple sites while purposefully and explicitly trying not to build walls? It becomes a question of sustainability, because operational funding in Finland, also on the regional level, ofen supports walls [organisations with a fxed base]. In a way, we are consciously going against the grain and some parameters of these funding systems.

M: How do you mould your exhibitions into the

73

horizon known by the locals? In the introduction to last year’s Visitors, you defne the guests and the locals as ‘producers of the exhibition.’2 How do you deal with and build site-specifcity?

E: It’s important to recognise that our projects aren’t participatory, in the sense that we don’t work directly with local communities on a large scale. Tere are many reasons for that, mostly it comes down to resources and that we move location each time. It’s always a restart. So we recognise we won’t be able to fully navigate local knowledge(s) – which are already always multiple. Nonetheless, there are clear reasons drawing us to a specifc location. Te ‘intimate outsider’ position is a helpful way to articulate our role.3 We are always present in the exhibitions while they are open to the public, so the exchange and articulation of our work happen then, too.

Recognising others as co-producers must be the case when working in public spaces. It’s one way of admitting that we don’t have full control of the process or the outcome – which is horrible and wonderful! Tis is why we work as we do: these processes always have something to ofer that we alone couldn’t have imagined, and that’s what moves us forward. We are keen to be present and engage with the visitors because they feed our thinking, and we can only hope it goes both ways.

74

75

FEMMA Planning, Lähiölaboratorio, 7 July 2022. Porin kulttuurisäätö, Pori Biennale Visitors, 2022. Vuosaari, Helsinki, Finland. Photo credits: Erno-Erik Raitanen.

76

M: Being present on-site and the self-awareness you bring into the project reinforce your accountability and self-positioning. Tis efort to gather people and talk isn’t necessarily about the location and its inhabitants, but has been thought for and with them. Can you recollect some of the conversations you’ve had with your visitors?

E: Tey could literally go any direction! When we started, the exhibition took place while the Pori Jazz Festival and Suomi Areena (the biggest public platform for debate in Finland) were happening in Pori at the same time. Tey brought tens of thousands of people to a city of modest scale. Pop-up exhibitions and art events started to cater for these guests. As local practitioners, we wanted to provide another perspective on what Pori could ofer. We directly addressed how people engaged with the exhibition in an urban setting.

Pori World Expo (2015) is still one of my favourite exhibitions: a white pavilion with a pool surrounding the building and a pathway to cross the water to get to the installation. Tere was no material artwork inside. Te artist’s name, a short description of the work, and a phone number were in place of the artworks, which were expressed in performative and conversational formats through a phone call. It was confusing for some visitors, and we were

77

present to fgure things out with them. Tis confrontational aspect was a great school for us to talk transparently about who we are, where we come from, what we do, why exhibitions can also take these forms, and what’s the point of it.

Porin kulttuurisäätö, Porin Maailmannäyttely (Pori World Expo), 2015. Pori, Finland. Photo credits:

78

Niilo Rinne.

M: You work in spaces that people feel familiarity and habit towards. Maybe this is like being in someone’s home and telling them that the view from their window is diferent when you look at it upside down: challenging one’s perspective the way a friend would. You write that ‘art has the power to alert if we choose to pay attention,’ and about ‘giving enough keys’ as a way of making this challenge accessible.4 Can we talk about accessible language?

E: We’ve had the tradition of producing a catalogue, even with modest resources. Our goal is to translate our processes and thinking in the best possible way. Tis means articulating the starting point, how we got there, and sharing some of the pros and cons on the way. So the work can become relatable. Working in spaces that people feel care towards, our relation with the audiences starts, at least, from a shared appreciation for the place. A collective imagination also helps when talking about accessibility.

M: What do you mean by “collective imagination”? Is it a shared understanding?

E: I don’t think it can be “shared”, in the sense that everyone would need the same experience, background, or point of view. But “collective” exactly because it includes all of these

79

perspectives, even in a scattered manner. To me, collective imagination is about these layers and leaving room for personal navigation. It reminds me of the project Te Truth About Finland (2017), which we produced for the centenary of Finland’s independence. Even the title is a paradox, as there is, of course, no one truth, and our approach was to bring 100+ contributors to talk about what independence means.

80

Porin kulttuurisäätö, Pori Biennale Totuus Suomesta (The Truth About Finland), 2017. Pori, Finland. Photo credits: Niilo Rinne.

M: So, collective is what is produced by a number of diferent voices …

E: And is open …

M: And purposefully comes together …

E: And there is a framework to which each one adds on.

M: Ten, collective is something that is wanted and built?

E: Yes!

M: Great! [We laugh.]

M: Somewhere you’ve described the curator as ‘a cushion’. I like that image.

E: Have we said that? I like that image too, and it reminds me of the exhibition by curatorial duo nynnyt, Between a rock and a hard place there is sofness (Titanik, 2018). It’s important that everyone in the team is aware of what is happening with the others rather than having completely isolated processes. We encourage our collaborators to use the project to experiment or try new things. And it’s been lovely to work with a few artists long-term. In her recent dissertation, Anna Jensen calls these artists

81

‘double agents’ because they and their knowledge are situated somewhere between us and new collaborators.5

M: I’d say that the aesthetic of your curating plays with some sort of “magical modesty”. I read it as a way of producing and encouraging cohabitation – of art and the built environment, with its contradictions, everyday tensions and possibly difcult conditions – instead of competition between the two. Tis counteracts the traditional language of public art, which tends to be grand and authoritative, making the viewer passive.

82

Taidekoulu Maa, Art School MAA Day, 20 July 2022. Porin kulttuurisäätö, Pori Biennale Visitors, 2022. Rastila, Helsinki, Finland. Photo credits: Erno-Erik Raitanen.

E: Yes, I really like this way of putting it. It reminds me of vähätaide (I’m not sure how to translate it accurately, perhaps “minor art”), a term that artist, curator, and writer Kari YliAnnala has used to describe our practice too, referring to Deleuze and Guattari for its origin.6 In vähätaide, rules and customs are twisted or redefned, everything is political and linked to communal values. In the public space, the surroundings and the artworks don’t need to compete but should rather communicate with one another. Ofen, this tension is dismissed with “Te artwork doesn’t add anything to its environment,” and then I wonder if the whole deal is of, if the problem comes from how art was articulated to begin with, as the visitor expects a museum-like experience where the artworks are in a fully controlled situation with no interruptions. Modesty comes down to resources, too. Working with pre-existing locations, we have built our practice around using what we have, what we can access and, again, what is worth being alert of – is that how you say it?

M: I guess? I like it! Being alert is an interesting way of looking at things. It suggests militant aesthetics, a way of moving into the world caring enough to look hard, notice, and express. Art and exhibitions can facilitate this. I appreciate that it expects responsibility and efort from all sides – producers, artists, and audiences alike.

83

Everything comes down to behaviour, attitude, and attention. In your experience, how is public space perceived in Finland?

E: I don’t know if there is such a thing as a cohesive idea of public spaces, as I don’t think there can ever be consensus. Chantal Moufe, for example, suggests that public space is always in confict due to its inevitable pluralism.7 In general terms, public spaces in Finland are approached with obedience and respect. Tere is a code of conduct on how to behave to avoid causing distress to others. Public life here sufers from the long winters: gatherings take place indoors, they become exclusive; private or semi-public sites, such as malls, become “public spaces” despite mainly serving a consumerist agenda. In my mind, Finland is extremely rooted in the Nordic welfare state, where civic action, protests, and activism are generally not so valued; the mentality is that decision-makers know best, and individuals simply want to mind their own business. Tis is hopefully and already changing. In terms of working with projects in the public space, the amount of rules, regulations, and people who are simply gatekeeping is endless. At the same time, cities’ rebranding strategies ofen come down to a few harmless events that carry no critical questions or aims.

84

85

Anni-Anett Liik, UNNAMED FOREIGN BODY. Porin kulttuurisäätö, Pori Biennale Visitors , 2022. Kallahdenniemi, Helsinki, Finland. Photo credits: Erno-Erik Raitanen.

86

E: In 2018, we published a questionnaire asking people what their expectations and desires towards contemporary art were, and the majority felt warmly towards “being surprised” in their everyday context. To me, this links to the act of alerting. As Lucy Lippard suggests, all of our surroundings are one big ‘lost and found,’ and the real work starts afer the fnding.8

M: Finding what?

E: Te place! Lippard talks about engaging with the surroundings and how, beyond one’s curiosity or attention to the site, to work with that location, to “pick it up” from the lost and found, you’ll have to go through such bureaucratic mayhem. Tis is our experience too, dealing with the infrastructures of various cities. As you enter their chain of command, most of your time, resources, and patience will need to go into navigating diferent interests in the public space, ofen with opposing logic and little reliability. One big part of the job is fguring out how to work, in any capacity, with spaces that should be of public access. We try to articulate the politics of the locality in each project.

87

1. Te frst ever Porin kulttuurisäätö project, Te Sponsor, was realised with a one time working group (Anna Jensen, Niilo Rinne, Eliisa Suvanto, Eetu Henttonen and Anni Venäläinen) all connected to Aalto’s MA program. Since then Jensen, Suvanto and Venäläinen continued Porin kulttuurisäätö as a collective working on site-specifc practices. In 2024, Porin kultuurisäätö consists of Jensen, Suvanto and Sanna Ritvanen, who joined the group in 2020.

2. Porin kulttuurisäätö, Pori Biennale 2022 - Visitors, 2022 (https:// porinkulttuurisaato.org/projects/pori-biennale-2022-visitors/).

3. Porin kulttuurisäätö, Pori Biennale 2023 - #Holiday365, 2023 (https://porinkulttuurisaato.org/projects/holiday365-catalogue/).

4. Porin kulttuurisäätö, ‘In Praise of Pällistely: Art, nature and tourism as felt and imagined experiences’, ed. Neal Cahoon, Miina Kaartinen, mirko nikolic and Anu Pasanen, Mustarinda: Elinvoima (2023).

5. Anna Jensen, ENCYCLOPEDIA OF IN-BETWEENNESS. An Exploration of a Collective Artistic Research Practice (Espoo: Aalto ARTS Books, 2023), 177.

6. Kari Yli-Annala, ‘Saaristo ja rihmasto: vähätaiteesta, vähäisistä taiteista ja vähän vähemmistötaiteestakin’, Mustekala, 6 March 2023 (https://mustekala.info/saaristo-ja-rihmasto-vahataiteestavahaisista-taiteista-ja-vahan-vahemmistotaiteestakin/).

7. Chantal Moufe, Te Democratic Paradox (London: Verso Books, 2000).

8. Lucy R. Lippard, Undermining: A Wild Ride Trough Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West. (New York: Te New Press, 2014), 304-305.

88

From us to us

Alice Mutoni, Ubuntu Film Club

89

“Expanding narratives, with a twist of fun, one flm at a time” is the motto of Ubuntu Film Club (UFC). UFC organises flm screenings in Helsinki since 2019, giving visibility to minorities’ stories and storytellers. Te screenings are free of charge and open to all. Tey deal with urgent topics such as the war in Congo, sexual violence against women, and the lives of LGBTQIA+ people. Te flms are followed by discussions with experts, occupational therapists, activists, and flm directors, who open up these issues with the audiences. Most visitors are between 16 and 35 years old. UFC founders are Alice Mutoni, Rewina Teklai, and Fiona Musanga.

I frst attended Ubuntu Film Club’s outdoor screening with PopUp Kino in Aurinkolahti in August 2023. I was then in touch with Alice, and attended their event produced in collaboration with Tink Afrika. Tis conversation was recorded on January 18, 2024.

90

Alice (A)

Micol (M)

A: I was watching a lot of documentaries; it was easier for me to digest information that way rather than sitting through a book or a lecture. I was learning, and I thought we could start a flm club to show documentaries and open up the topics in a discussion.

Tis was 2019. A lot was going on in the media about immigration; those conversations were happening either virtually on social media or in academic spaces. Bringing them to a less intimidating place, like Museum of Impossible Forms (MIF), was inviting people to come, learn, or just observe without needing a specifc background or prior knowledge.

91

M: MIF ofered their space when you started and, since then, you have attracted the interest of many other organisations around the city. Do you think there’s a lack of capacity in the local cultural feld to produce projects like Ubuntu, which created a lively world from the simple format of a flm club? In your experience, what are the cultural or material barriers preventing similar projects from happening?

92

Ubuntu’s christmas screening at MIF, 2019

A: When we started Ubuntu Film Club, there was nothing like it in Helsinki: three young Black women organising documentary screenings. Many were curious and really wanted to support us; they seemed eager to help younger people get on their feet. Honestly, we knew nothing about licensing, screening fees, grants ... I assumed I would have paid out of my pockets. MIF was able to help us with that. Te difculty isn’t in keeping the ball rolling or imagining what the project could be but in knowing how to start if you aren’t already inside the scene.

M: Is it accessible information that is lacking, to begin with?

A: Tat’s it.

M: You were 21 years old when initiating Ubuntu Film Club, and the majority of your audience consists of young adults. Can their participation tell us something about a generational experience when it comes to access to communal spaces in Helsinki?

93

A: People come to our events because they feel comfortable, because it is from us to us. When people arrived a little early, and we were still organising the space or making sandwiches, everybody would jump into the kitchen. Tere was no diference between us running the club and them; there were no rules. Te space was stripped down of those power dynamics.

When I think back to it, that on a Sunday evening and in the winter, people would sit on those little foldable chairs to watch our documentaries, plus

94

Homecoming and Beyoncé’s party at MIF, 2019

the discussion aferwards ... Man! Tat space was really important! It was needed for many.

M: I was looking into people's reactions to your events when I came across an article that described the atmosphere as “expectant […] It is hard to believe that you are in Finland.”1 I’m always intrigued by statements like this, which play with expectations connected to geography and nationhood. If you feel comfortable, I’d like to talk about belonging. You shared with me about wanting to move abroad and how organising Ubuntu helped you make a home in Helsinki. What was lacking in your experience of living here that Ubuntu has fulflled, and how?

A: In 2018, I was travelling to London, where there was such a boom of cultural happenings: a lot was organised by young artists, club events focused on African music, open mics ... It was my frst time there, and when I came back, I was bored. Where are all the people? Black Femme Film inspired me to start Ubuntu. It was fascinating because, in Finland, people were still getting used to using terms like ‘POC’, while in London, there were successful events on Black women and femmes in flm. I needed to create something to resemble that. I didn’t even think about limiting the target audience because there was no other active flm club and because to have the discussions we wanted to have – about

[Alice laughs.]

95

racism, for example – it’d have been important to have non-Black people come into that space, learn, and ask questions. I called it Ubuntu, and we started. It became my baby. I wanted to invest in it, and the people who came to the events became really, really important to me. So, I no longer felt like I had to run away from Helsinki to feel what I had felt in London or what I thought people felt in London. Now I have that here.

M: Te flms you screen ofen address complex topics. Can you talk about the response of the audience and how you are hosting the space for these conversations? Is there any particular comment or a moment that stays in your memory from these discussions?

A: Te frst ever flm we screened was City of Joy: Turning pain into power (2016). It is about a women’s centre in the Congo where women who have been sexually assaulted and who have experienced violence in the midst of war, would go to tell their truths and learn ways to heal from those traumas or to cope with them. It was heavy. I’m no expert in the history of the war in the Congo, so we called in someone who could talk to us about it. My main point was to learn from the events myself. Te reaction to that flm was what kept us going! Many young people, also of African descent, didn’t know about what was happening in DCR. We had an open space to interact in a

96

language accessible to us. Language is really, really important. Seeing young people excited to learn, open to asking questions, and receiving the answers was lovely. It was really lovely.

I’ll never forget our screening in Ateneum. Te flm was Rafki (2018), about a lesbian couple in Kenya, and it was in Swahili. A friend of mine who is from Kenya and part of the LGBTQ+ community said, “Never in a million years would I have thought to be in Finland watching a flm about queer people in Swahili without having to read the subtitles!” On top of that, it was in Ateneum, not a familiar space to our audience. Tis was during our frst year, in collaboration with UrbanApa. It felt big! When Sonya Lindfors said we could make it happen, I got nervous because ... you know, at MIF, we would scream and run around, have a drink and a laugh, it was so light! I was scared that going to Ateneum would change the atmosphere: would people feel that they must manage their reactions, the way they act, the way they talk? Sonya said, “No, we are going there and we are going to be ourselves, do our thing.” So we were in Ateneum playing Afrobeats. It was liberating.

[Alice smiles.]

97

M: You, Rewina, and Fiona have been referred to as ‘young power women.’2 Do you identify with this power? What do you think makes you perceived as powerful in relation to Ubuntu and the rest of your work?

A: Te work we do is powerful, but the three of us as individuals don’t hold power. Infuential? Yes. We have the capacity to bring ideas to life and people together, but this is work that a lot of people can do if they have the means. If we were to stop running Ubuntu, I believe that people would remember our work in more powerful

Ubuntu’s founders with Anna Möttölä, CEO of HIFF and Director Khadar Ahmed at ’The gravedigger’s wife’ screening, 2021