SUITED AND ROOTED

Bryan C. Barnhill II, the youngest member of the WSU Board of Governors, reflects on his upbringing on the east side of Detroit, his role in the historic shake-up of city politics, and what’s next for one of the city’s brightest lights.

Inside this issue …

Page 3: Letter from the president

Page 4: From the oustide in

As an outspoken young activist, Bryan C. Barnhill II spent a lot of time fighting the powers that be on behalf of the city’s most disadvantaged. Even though the WSU Board of Governors member has now amassed a little of that power himself, the struggle, he says, continues.

Page 8: Designing woman

WSU alumna Emeline King recounts her legacy as Ford Motor Co.’s first Black female transportation designer.

Page 11: Full circle

New Warrior 360 program offers a panoramic view of student success.

Letter from the president

At Wayne State, we’ve always been proud of our university’s deep, singular connection with the city of Detroit, its people and its long, winding history. Our work in Detroit isn’t only to educate and to inform but to transform as well, to ensure that we’re creating paths that will allow all our students to change their lives for the better. In return, those students make us, the city and campus alike, a richer place to learn and a more rewarding place to live.

This insert offers a few reminders of how, for decades, we’ve impacted the lives of Detroiters in general and Warriors in particular, and how many of those same students have repaid us a hundredfold with contributions that have made all our lives a little better.

From the nursing school education that allowed the mom of current Board of Governors member Bryan C. Barnhill II to upgrade her family’s lives (Page 4) to the engineering degree that enabled alumna Emeline King to become Ford Motor Co.’s first Black female transportation designer (Page 8), our commitment to raising up the lives of Detroiters through education has been richly rewarding for our students and our city.

Likewise, Wayne State has been bettered by that relationship with our communities and our students, whose accomplishments are the ultimate affirmation of our commitment to quality education and equal access. Therefore, we continue to seek new, more effective ways to foster student success on our campus (Page 11) and to shape leadership that will improve lives in the communities that surround it.

Because when the city and the students we serve rise, we all go along for the ride.

M. Roy Wilson, President Wayne State University

cover story

As an outspoken young activist, Bryan C. Barnhill II spent a lot of time fighting the powers that be on behalf of the city’s most disadvantaged. Even though the WSU Board of Governors member has now amassed a little of that power himself, the struggle, he says, continues.

He started with the earthworms. As far back as he can recall, political strategist and activist Bryan C. Barnhill II, the youngest member of the Wayne State University Board of Governors, felt the need to make a difference, to safeguard what he saw as vulnerable, endangered.

For a preschool-aged Barnhill, that meant sifting through wet dirt on rainy days around his childhood home on the east side of Detroit, trying to make sure that the worms were doing OK.

“I was a serious little kid,” he recalls with a brief, wry grin. Hair braided, eyes narrowed and focused, he leans back in his chair during a morning chat at the Fisher Building in the city’s New Center area and crosses his legs. “Because I felt like, for some reason, the stakes were high,” he continues, his baritone a mix of gravitas and fond remembrance. “I needed to do the right thing so I could have a chance. And I felt like I had a duty to try to do something. My mother

tells me that I was the type of kid who would go outside when it was raining and try to put the worms on the leaves, to protect them from the water. I really thought I was saving the worms.”

That sense of responsibility solidified as he grew older. As a teen, he stood up to neighborhood bullies who tried to pick on smaller children. He joined his churchgoing mom to help with the block club she founded. He cut unruly lawns in vacant lots and swept up trash in front of the crumbling, abandoned homes that dotted his struggling community around Conner Avenue and Gunston Street.

“My parents are what folks call ‘good people,’” he says of his mom, a nurse who earned her degree from Wayne State University, and his dad, a professional truck driver. “They always tried to instill good values in me and my sister. We always had activities. And my mother would give us responsibilities in the neighborhood.”

These activist clubs cleanup breathes air state’s politicians, powerbrokers.But there was plenty of fun to be had, too, be it on the bikes he rode freely throughout the neighborhood, on the swing sets that brought throngs of kids to his family’s backyard or atop the blacktop basketball courts where he’d play pick-up games on hot summer days. Barnhill says those memories, co-mingled with that irrepressible sense of duty, produced a love and deep appreciation for Detroit, for its blue-collar hustle and its unbowed sense of optimism in the face of struggles and challenges.

These days, the east side activist reared on block clubs and community cleanup projects now breathes the same rarefied air as the city’s and state’s most influential politicians, businessmen and powerbrokers.

Even now, long after his family moved away from Conner and Gunston, more than a decade after Barnhill graduated Detroit Renaissance High School to pursue a degree at Harvard University and years after he found himself at ground zero of one of the most seismic political upheavals in recent Detroit history, Barnhill says his commitment to and love for his city endure.

“I’m very much a product of my community,” he says. “The beauty of it, the strength of it. There is a dark side — but you have to find light in the darkness.”

These days, the east side kid who once casted about in mud in search of earthworms to rescue has become a man — a still-youngish one, at that — who breathes the same rarefied air as the city’s and state’s most influential politicians, businessmen and powerbrokers. He’s gone from the neighborhood block club to board seats on the Detroit Institute of Arts, the United Way of Southeastern Michigan and the Detroit/Wayne County Stadium Authority, among other institutions. And the precocious son who grew up amidst the blight of Conner Avenue is now a father of two and a husband, still an eastsider, but one ensconced in the city’s tony Indian Village neighborhood. Nevertheless, for the political wunderkind who many consider most responsible for the 2013 mayoral election of Mike Duggan, the first white Detroit mayor in nearly half a century, the same sense of duty and responsibility he’s harbored since childhood continues to call.

And Barnhill continues to find ways to answer. At present, he works at Ford Motor Co. for the automaker’s Smart Mobility City Solutions Group, where he has an important hand in molding Ford’s urban ecosystem for mobility innovation in Detroit. And while Barnhill says he has no desire to run for any elected office beyond the one he holds as a WSU governor, his successful campaign work for groundbreaking political figures such as Charles Pugh — the city’s first openly gay city councilman — and Mayor Duggan suggests that, at the very least,

he could play the role of kingmaker in local election cycles to come.

“There is little to no chance of me running for another political office — like maybe 5%,” Barnhill says emphatically. “I don’t think we need me to run for office. There are tons of talented people out there who can do it. We need more folks who share similar viewpoints, who have a perspective of people coming from our community, to be in a position to support these campaigns.”

However, Barnhill makes little secret of his desire to help mold those future campaigns and candidates.

“Now, I have the experience to say, ‘OK, this is what a successful campaign looks like. This is what successful administration looks like. This is what an unsuccessful administration, unsuccessful politician looks like. This is what a successful business looks like. This is how successful organizations operate. This is how you make change within that context.’ I like the Vernon Jordan types, the Clarence Avants,” he explains, referencing the civil rights leader and music mogul who both earned reputations as fearsome behind-the-scenes operatives.

He confesses that his desire to steer clear of political office stems in part from a reluctance to feed too much into a sense of self-importance. “I’m a Leo. We’re told our egos can get out of control. And so for me, it’s also thinking, If I really want to make a difference, why do I need to be in the spotlight? It’s my ego. I want to have that in check. When you see a lot of people make mistakes, it’s their ego that gets in the way.”

He doesn’t say it, of course, but the inference to one of the biggest scandals in Detroit history is unmistakable: Barnhill wants no parts of the sort of missteps that felled the last young turk to storm Detroit politics, disgraced ex-mayor Kwame Kilpatrick.

Of course, in some ways, that scandal helped create the opportunity for Barnhill to showcase his considerable political and organizational talents. Kilpatrick’s fall and the subsequent rocky tenure of elected successor Dave Bing left many Detroiters angry, disappointed and mistrustful of local leadership — and inspired a longtime local powerbroker, then-Detroit Medical Center CEO Mike Duggan, to fill the seat.

But Duggan is white in a city that’s more than 80% Black and that hadn’t elected a white man to serve as mayor since Roman Gribbs left office in 1974. The challenge, most observers agreed, would be formidable, if not outright impossible. And the challenge grew even steeper after Duggan failed to qualify for the ballot and was forced to run a write-in campaign that few thought he’d win. Barnhill was among that few.

Up until then, though, Barnhill hadn’t garnered much formal political experience. As an older teen, he had cut his teeth in the By Any Means Necessary (BAMN) grassroots movement, where he often engaged in demonstrations and protests centered on issues such as anti-affirmative action measures and inequitable school funding. Barnhill had also belonged to the citywide student council, where he and close friend QuanTez Pressley served as school board representative and vice president, respectively.

“Sometimes, I was sitting down with the school superintendent, and some other times, I’m coming in there with a bullhorn behind me,” he recalls. “BAMN was fascinating at that time because I felt like they gave me an outlet to be politically active in a way that some of the more tried and true organizations had not. In addition to the activity, we would have study groups where we’d read Karl Marx, read about the civil rights movement, and then go out and organize folks for things like the National March to Defend Affirmative Action in Washington, DC.”

However, he says he began to evolve after graduating high school and heading off to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to attend Harvard University. He was invited into the exclusive circle of the university’s “final clubs,” where he began to rub shoulders with influencers in business, politics and culture. Barnhill says he started to realize that he had an opportunity to network and make change in ways he’d never considered possible while growing up in Detroit.

“Going there opened me up to a whole new level of wealth and power,” Barnhill says. “Some of the people in these clubs are, quite frankly, some of the wealthiest, most powerful people who run the world. And the cool thing is we’re friends. We’re friends, and now we’re in a club together, and we’re just kind of hanging out, supporting one another. They’re listening to my ideas. I’m listening to some of theirs.

“It was not the black-and-white situation that I thought it was. I had a unique position to be in places to do things, have a relationship with audiences that not a lot of folks in our community would tend to have, and this is the kind of attitude that I have

I’m very much a product of my community. The beauty of it, the strength of it. There is a dark side – but you have to find light in the darkness.

today. I want to be able to take my perspective, my experiences, and make change within these groups in these rooms.”

Of course, he says, his more radical peers in Detroit hadn’t even wanted to him to go away to school: “They were like, ‘Why would you want to do that?’ But in my mind, I was like, ‘I’m doing this for my community. I’m going here for my family.’”

And after graduating Harvard, Barnhill says, he made the decision to return to Detroit for those same reasons. Although he’d landed a cushy position handling private equity in New York City, he knew his fate rested back in his hometown.

“The plan was always to come back,” Barnhill says. “I just thought that I would come back as this rich and successful person who can just kind of do my thing, but it was a special moment that I think was the culmination of a lot of crises. You had Kilpatrick. He was going through what he was going through. You had the auto industry headed toward bankruptcy. You had the city headed toward bankruptcy. There was the mortgage foreclosure crisis. And I got tired of reading about how horrible it was in Detroit and then having conversations with people in New York like, ‘Hey, man, you’re from Detroit. What’s going on?’ As I reflect on everything that energized me when I was younger, I was trying to do positive stuff in the community.”

Barnhill says he got calls from his two closest friends, Pressley — now a pastor at Third New Hope Baptist Church in Detroit — and current state senator Adam Hollier, both of whom also were trying to find their niche. “QuanTez had been talking about going the Peace Corps, but he said, ‘Why would I do that when I can just do the same stuff in Detroit?’ Adam was already back in Detroit after going to [University of Michigan] to get his degree in urban planning. They were already committed to coming back and wanted me to join up with them. Eventually, I was like, ‘I’m in.’”

And so he came back … just as Detroit seemed ready to implode. Kilpatrick had been ousted from office and was headed toward a criminal trial and,

ultimately, a conviction and lengthy prison sentence. The city was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, with its first emergency manager only a few years away. And the local economy seemed to be in shambles.

Barnhill felt that pain, too. Although he was fast becoming adept at networking and building relationships, his efforts didn’t immediately translate into success — or even employment. “I was sleeping at my parents’ house, trying to find a job,” he says. “And I appreciate my parents because they know me. If they didn’t, they would’ve been very upset. I didn’t want to be a loser with a Harvard degree.”

Eventually, he landed with nonprofit group Southwest Housing Solutions, which handled low-income housing. But he also decided that he’d devote his free time and energy volunteering for one of the few local political aspirants who didn’t mind his lack of experience, then-TV news personality Charles Pugh, who’d just left Fox 2 Detroit to make a run at a city council seat in 2009.

Barnhill eventually forged a friendship with a local Republican figurehead, who hoped that Barnhill might direct his talent toward conservative candidates. But when the GOP operative realized that Barnhill wasn’t likely to shift rightward, he began putting the upstart strategist with key Democratic colleagues.

“In politics, just like in sports, opponents have relationships with one another,” Barnhill explains. Turned out, one of those colleagues was good friends with a hospital executive and former Wayne County prosecutor who had been mulling a run at the mayor’s seat in the aftermath of Kilpatrick’s fall. “So he called me,” Barnhill recalls, “and said, ‘Hey, Mike Duggan is thinking of running for mayor. Would you be interested in leading the exploratory committee?’”

After City

“QuanTez was volunteering for the campaign as well, so we spent most of the time passing out flyers,” Barnhill remembers. “And then QuanTez and I started figuring out other ways we could make a contribution. Charles didn’t need that much help in terms of notoriety. Everybody knew who he was. So, we figured we could add value in sharpening the focus of the policy issues.”

Leveraging the experience of other, more seasoned volunteers, Barnhill said he and Pressley began to promote community discussions aimed at focusing the candidates on key policy points. They attended debates and took careful notes about community members’ talking points. And they fed everything they learned into the campaign.

Pugh won handily, earning the most votes of any candidate, which automatically earned him the city council presidency. And Barnhill, then barely 23, had officially served notice that he was a political force to be reckoned with.

Barnhill didn’t know much about Duggan’s history, so he reached out to the political figure who knew his work best. “I called Charles Pugh, and he said, ‘What I know about Mike Duggan is that he’s able to get a lot of stuff done. I think he would be great for the time that we’re in.’ And this was as the city was headed toward bankruptcy. Mike was someone who’s very skilled at running large-scale organizations and putting forth different initiatives. I thought, ‘OK, this capability is going to be what we need.’ Also, I’m very aware of race and racial dynamics. We are totally aware of the racial animus that has existed in this region. And the city of Detroit has basically been a proxy for Black folks. I thought that Mike Duggan would help bring in resources to benefit Detroiters.”

After multiple positive meetings, Barnhill took over the exploratory committee, which included a broad swath of Detroit community leaders. “And from there, we started to develop the beginning stages of the policy platform. We took this focus on neighborhoods and went from there.”

It wasn’t long before Duggan took notice of Barnhill’s work, his energy and his knack for making the right connections at the right time. Soon, he asked

the campaign Despite began only neighborhoods build people influential — ended couple majority trying from the So house ‘Hey, All and Barnhill use and but But came ineligible gone changed think had folks any period.’ became read time paperwork been So, Barnhill says he got more serious about his role in politics after his wife, Rian, announced she was pregnant with the first of their two children.

the young Harvard grad to come on board as his campaign manager.

Despite his hesitance, Barnhill signed on and quickly began working to strengthen Duggan’s ties to not only corporate leaders but, more critically, to the neighborhoods in the city. “Our job was really to build some momentum so that we could convince people who were influential folks in town — whether influential in business or influential in the community — that we could actually succeed,” he says. “We ended up pursuing this grassroots approach. A couple of people said they’d support Mike, but the majority of folks were risk averse. So instead of trying to knock on doors and get the endorsements from the key leaders in town, we just needed to get the people’s endorsements.”

So he began to gather the people. “We set up this house party effort and just told people basically, ‘Hey, you can be your own leader in the campaign. All you have to do is gather at least 10 of your family and friends and tell us to come and we’ll be there,’” Barnhill says. “We did a bunch of those. We would use that as an opportunity to sharpen the platform and get more awareness of what the issues were — but also to collect data on volunteers.”

But Barnhill’s first shot at leading a campaign nearly came to a premature halt when Duggan was ruled ineligible for the city ballot. “The city charter had gone through a revision, and the language had changed for eligibility to run for office,” he recalls. “I think this was really a backhand to Dave Bing, who had moved to the city from Franklin. So, I guess the folks engaged said, ‘Look, we’re not going to have any more of this. You need to be here for a certain period.’ But Mike filed for office during the year he became a Detroit resident. The charter language read that you had to be a resident for a year by the time you filed for office. Because he turned the paperwork in two weeks prior to what would’ve been a year of him being in Detroit, he was ineligible. So, he ended up getting thrown off the ballot.”

Barnhill, who says he was often pilloried for supporting Duggan and accused of undermining Black political power in a majority-Black city, says Duggan wanted to suspend the campaign at that point. But Barnhill nevertheless urged him on.

“It was a blow to me,” he says. “Because I’m the one taking all these shots. People were cruel when the campaign was over. Some people felt like it was a betrayal to even try to do it in the first place. But given my understanding of history, and the pride I have as a Black person, I can see where they’re coming from. That was tough. But I didn’t want to be a loser.”

‘Hey, call Mike. Tell him that you’ll be behind him if he ran a write-in campaign.’ He was overwhelmed with calls. Somewhere, somebody convinced him — or maybe all the collective convinced him — that we can do this.”

Duggan won in a landslide and took his seat in the Manoogian Mansion at the start of 2014. Barnhill stayed on, carving out a position as chief talent officer in the mayor’s first administration. He stayed for five years, leaving his post in 2018 to pursue business opportunities and seek out new challenges.

In the city, there’s still plenty of work that needs to be done — especially in the neighborhoods. Though Barnhill expresses little interest in any high office right now, he admits that running for a seat on the WSU Board of Governors in 2018 was a nod to his love of public service — but also a bit of an homage to the woman who initially fostered his belief that he could make change.

“My mother went to Wayne State when we were growing up,” he says. “That’s where she received her nursing degree. So growing up, I see her studying, I’m studying. I’m seeing her go through what she needs to go through, working and going to school. And I saw her accomplish her goal and saw our lives get better. By the time I graduated high school, my parents, they bought a house in a nice neighborhood on the west side. This was the opportunity that Wayne State provided. So, I feel like I want to be able to preserve that opportunity for other families, for other people who want to do better in their lives. And I value Wayne State as an institution that helps make that happen.”

Barnhill points specifically to WSU’s determination to improve social mobility for students and graduates, saying that that mission aligns perfectly with his own hopes for the university.

His confidence in Duggan aside, Barnhill says he had another, more intimate reason to forge ahead. His wife Rian, whom he married in January 2013 just before the campaign began, had called him with an announcement: She was pregnant with the first of the couple’s two children. To Barnhill, failure was no longer an option.

“I was determined to try to keep this going,” he said. “And there were some other people in the community who were also very supportive of him continuing. I know that from a period where we suspended the campaign to where we reinitiated the campaign, I was just calling everybody that I could,

“My goal is to continue to make Wayne State a place that is accessible to people and also be a place to help folks better themselves through higher education,” he says. “Our focus as a university is to become the number one school for social mobility, which is just a fancier way of saying kind of what I had in mind earlier. And I thought it would be not just a way to stay involved in public service, but to stay involved in public service in a low-key way.”

And so, Barnhill says, he goes to work in the community, at WSU and inside Ford, the same way he has from the start: in earnest sincerity and with both feet firmly planted where he thinks he will do the most good.

The earthworms would no doubt be pleased.

My goal is to continue to make Wayne State a place that is accessible to people and also be a place to help folks better themselves through higher education.After graduating Harvard, Barnhill landed a cushy position handling private equity in New York City — but he knew his fate rested in his hometown: “The plan was always to come back.”

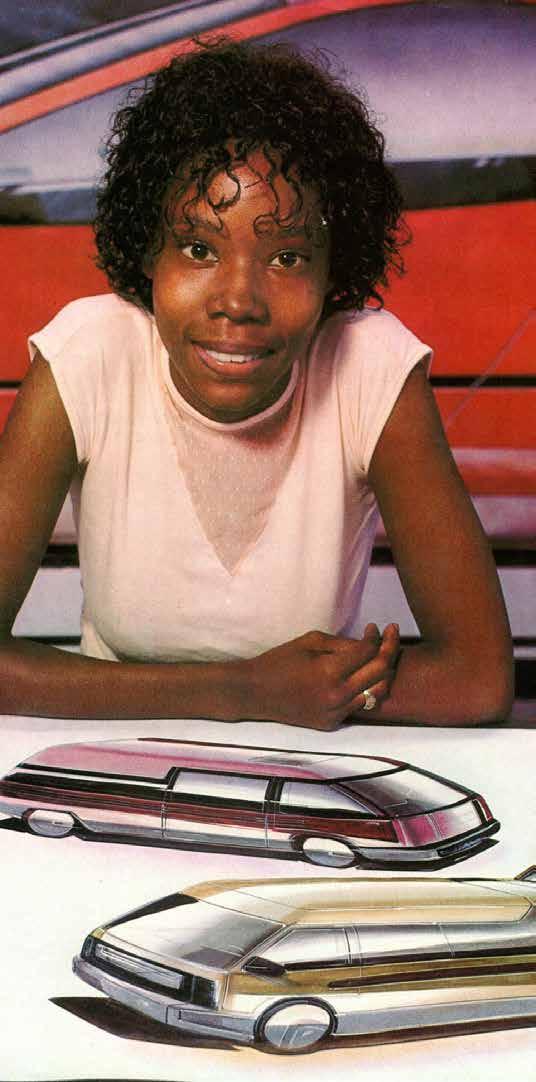

A young Emeline King shows off some of her forwardlooking designs.

designing woman

WSU alumna Emeline King recounts her legacy as Ford Motor Co.’s first Black female transportation designer

Emeline King leans forward and closes her eyes briefly, fanning her hands under her nose as if inhaling the aroma of a steaming pot of gumbo. In this instant, she’s 11 years old again, strolling with her father through the Design Center of Ford Motor Co. during the company Christmas party, olfactory senses tantalized by a strange scent wafting from behind a nearby set of huge blue doors.

“It was the clay,” recalls King, identifying the scent. “My father would take me to special areas around the building, and one area was near where they worked on the clay models for their cars. I had dabbled in clay before, but I had never smelled anything like this. I was fascinated over the smell of this clay. I wanted to get behind those blue doors.”

But those blue doors didn’t open for everyone, she learned: “My father told me, ‘Behind those doors are men who design cars. And you would have to be a transportation designer and a Ford employee. You have to work here to be a part of this clay.’”

In that moment, King says, her future was set.

“From that day forward, I made a promise,” she says. “I said three things I wanted to do: I wanted to become a transportation designer designing cars. I wanted to work for Ford Motor Company. And I wanted to work there with my father designing cars.”

More than a decade later, she made good on that promise. And she didn’t just pass through those doors either. King broke them down.

After earning her bachelor’s in industrial design from Wayne State University, King would eventually spend 25 years at Ford, becoming the first — and, as far as she knows, only — Black woman to work as a transportation designer at the auto manufacturer. Over that quarter century, she played key roles in some of Ford’s biggest projects, won some of the industry’s most prestigious awards, traveled the globe, and cemented her reputation as both an industry pioneer and innovator.

Now, following the recent release last year of her autobiography, What Do You Mean a Black Girl Can’t Design Cars?, King is not only sharing the story of her breakthrough legacy — she’s adding to it.

Having spends particularly She’s her to “It who playing King her designer, with the “A is remembers. be with tell You you housewife. do exposing In world and of the was scenes. sculptor took There, of Graves “Saturdays “At Black sculpture would of

under tantalized to part wanted and

Having departed Ford in 2008, King says she spends many of her days mentoring young people, particularly girls, hoping to fan their interest in art. She’s also a fixture on the speakers’ circuit, sharing her story and promoting her book. And she’s hoping to one day found a school for young women. “It would be an academy called She Did It — for girls who dare to dream big,” King explains. playing in the clay

King was once such a girl herself. After setting her ambitions on joining her dad at Ford as a car designer, King says, her path was constantly littered with critics and naysayers, minds too small to chart the trails she envisioned herself blazing.

“A lot of times my male teachers would say, ‘What is it that you want to do when you grow up?’” King remembers. “And I would always tell them, ‘I want to be a car designer. I’m going to work for Ford there with my father.’ And a lot of my male teachers would tell me, ‘Oh, no, Emeline. Girls cannot draw cars. You need to take those little hands of yours, and you should be either a librarian, a nurse or a good housewife. But as far as designing cars, girls can’t do that.’ Little did they know that my father was exposing me to the world of transportation design.” In fact, her parents had been exposing her to a world of art and design that was much broader, and more diverse and vibrant than what even many of her teachers had seen. For instance, her father, the noted local pastor Rev. Earnest O. King Sr., was deeply rooted in both the local music and art scenes. The Rev. King was close friends with famed sculptor and WSU alumnus Oscar Graves and often took Emeline and her siblings to visit Graves’ studio. There, she would experience firsthand the power of the clay as she’d sometimes watch her dad assist Graves with a commissioned sculpture.

“Saturdays would be like a little outing,” King says. “At Mr. Graves’ studio, we got a chance to see a Black sculptor. I was so fascinated with the beautiful sculpture pieces that Mr. Graves and my father would design — and I got a chance to dabble in some of the clay. I just loved playing in that clay.”

shaping the future

Even as she was shaping the clay, King was herself being molded. The more she dabbled, the more her dreams and determination hardened. By the time she was a student at Detroit Cass Technical High School, King was focused heavily on commercial arts, sculpture and graphic design.

“I would draw people, cars, anything,” King says. “But it wasn’t until I enrolled in Wayne State that I really got training related to transportation design. As I was going to Wayne State, my father had a bunch of his coworkers — and these were Black car designers, Black clay modelers — who mentored me. So I was getting Design 101 there.

“And the unique thing about going to Wayne State, I would take my academics in the daytime and then at night Ford Motor Co. had it where some of the transportation designers would come down to the school and offer transportation design classes.”

She also credits WSU with having a huge influence both on her work and on her love for art.

“Wayne State shaped me immensely,” King boasts.

“First of all, I liked that it was in the cultural center. You were surrounded by the museums, by the library. And going to Wayne State ... I’ll never forget.

I was infatuated with art history. I just loved art history. And like I said, there was also the advantage of having some of the car designers from Ford Motor Co. come and teach there in the evening. Then, in the morning, I would have my regular sculpture, painting classes, printmaking. Wayne State definitely was a launching pad as far as my career is concerned.”

King says she also was getting life lessons from many of her father’s friends. Graves, for one, urged her to get out of the United States for a bit and spend time abroad.

“When I would go to his studio, he would always tell me, ‘King, you have to go to Europe. You have to be indoctrinated with the European flair,’” she remembers.

But King was laser focused on the goal she’d set at 11 years old. Right after graduation, armed with a portfolio filled with oversized, 30” x 40” car illustrations, King applied for a job at Ford.

“When I presented all my car designs,” she says, “they did not believe that those designs came out my head. A lot of the drawings were 10 years ahead. These were the cars that I was designing.”

But an economic downturn had slowed hiring at Ford considerably, so the company passed on King at the time.

But she persisted. After an 18-month stint at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California, a prestigious school that had been attended by many

of Ford’s top designers, she left California and was right back at Ford’s front door.

“The school’s director had told me there were a lot of execs coming out there to see my work,” King recalls. “And I told him that I appreciated them coming, but I had promised [then-VP of global design] Jack Telnack at Ford that I would be interviewed by him. The director told me I was making the biggest mistake. Oh, he was so mad. But I wanted to keep my promise.”

breaking through

Her choice wasn’t a mistake at all. Shortly after her interview with Telnack, King landed the job. She had officially become Ford’s first Black female transportation designer.

And even as she was making history, she was also getting a chance to meet history. Right after she was hired, King recalls, she wound up meeting a man named McKinley Thompson — who had had the distinction of being the first Black man hired as a transportation designer at Ford. Like King, Thompson had also attended the ArtCenter College of Design.

“I thought that was neat — even though I wasn’t actually aware of it when I met him,” she recalls with a chuckle.

“I wanted to become a transportation designer designing cars. I wanted to work for Ford Motor Company. And I wanted to work there with my father designing cars.”These days, Emeline King spends her time speaking, mentoring and promoting her book.

“Wayne State definitely was a launching pad as far as my career is concerned.”

It wouldn’t be too long before King was again breaking new ground at Ford. In December 1984, she was sent to Turin, Italy, for a foreign service assignment. Finally, she would be able to absorb that “European flair” that her mentor Graves had gone on about years ago.

She left Italy an improved designer several months later, hungry to showcase her fast-developing talents. And she got the chance to show what she could do when she was tapped for a role in the design of Ford’s upcoming 1989 Thunderbird, for which she designed the wheels, interior and a portion of the exterior.

Beloved for its aerodynamic body and a wheelbase nine inches longer than its predecessor, the car was a big hit with auto enthusiasts. Ultimately, the 1989 Thunderbird Super Coupe was named Motor Trend Car of the Year, a monumental accolade for the entire design team, but especially for King. “It was a successful car,” King says. And it helped put the first Black woman to design cars at Ford firmly on the map.

But King, who also did foreign assignments in Germany and England between 1987 and 1990, says she wanted more. She dreamed of one day heading up a project on her own, to manage the development of a vehicle as opposed to simply contributing. Somehow, though, the glass ceiling always kept her bigger dreams out of her reach. “I always wanted to be a part of management,” she says, “but over the years, they kept passing, passing. I thought my credentials could get me into management, and my background, but it didn’t. So, I would have a lot of meetings with the execs to find out what is it that I need to do. I was passed over I don’t know how many times. I would look at the management and say, ‘It’s not diverse. It’s not diverse.’ But that went in one ear and out the other.”

King says a Ford design colleague advised her to get her name tied to a hot project that management would associate with her talent and leadership. But somehow, those opportunities always eluded her — until one day, she found herself working on

the vehicle whose iconic, one-word name alone could catapult her into the pantheon of great Ford designers: Mustang.

“We had one staff meeting where we had the designers, supervisors, myself and the engineer [in attendance],” she says. “And my supervisor said, ‘Well, today there’s going to be a revision to the ’94 Ford Mustang. This is a hot project.’ I had to get on that.”

offering veteran employees as part of its attempt to trim its workforce and reorganize the company.

She admits that she didn’t want to leave but had little choice.

These days, King spends her time speaking, mentoring and promoting her book.

“It felt like the bottom fell out,” King says. “They wanted to downsize. They took me out of the creative part. I didn’t mind doing the marketing, but I couldn’t do the creative part. And shortly after they moved me out there, it wasn’t too much longer when they ... when my boss mentioned to me that they’re doing the involuntary company separation.”

And with that, the first Black woman to design cars at Ford drove off into history.

King says she was added to the team after her supervisors agreed to keep her on from start to finish and to allow her to bring a strong, female perspective to the initiative. So how’d it turn out?

“It was a landslide,” King exclaims. “Every time the word ‘Mustang’ would come up, they related that to Emeline King. I would do a lot of PR work. I mean, a lot of PR work … I was doing interviews. They had me in magazines, on TV shows. And every time they would say ‘Mustang,’ my name would pop up.”

the next chapter

In the years that followed, King’s success on the Mustang led to work on other major vehicle designs, from the two-seater Thunderbird to the early iterations of the Lincoln Navigator SUV. She earned more praise, more notice, more impact. But somehow, her success never translated into the management role she so deeply desired, says King.

By the early 2000s, King’s circumstances began to change drastically. She was moved out of the design department and into marketing, she says. Not long after that, in 2008, she endured an “involuntary company separation” from Ford, accepting one of the many buyouts the auto manufacturer was

Even so, King says she remains appreciative of her two-decades-plus career at Ford and grateful for the opportunities she did receive to showcase her talents. She still shows up for certain events. And she is still friendly with company officials, who she says have been supportive of her post-Ford work and especially her book. In another nod to her impact, King’s work also has been featured as part of an exhibit at the Detroit Institute of Arts called “Detroit Style: Car Design in the Motor City, 1950–2020.”

She experienced her share of ups and downs along the way, she says, but she loved the ride. And she encourages all the young people she meets not to hesitate to take the wheel of their own lives.

“A lot of times when I go and do a lot of career day speeches at the schools, I let them know that if I can do it, you can do it,” King says. “The opportunity is there. I found it as a little Black girl from Detroit. I tell them, ‘People or mentors are like bridges: You grab ahold of one of those bridges, be influenced by mentors — or just look at what is it that you want to become — and you don’t let anyone tell you what you can’t do.’”

FULL For A performance, and So Wayne readily “I to their was it. those Where

New view

Equally duration to

“The opportunity is there. I found it as a little Black girl from Detroit.”Emeline King’s persistence and creativity landed her on design teams responsible for such signature Ford vehicles as the Mustang, the Navigator and the 1989 Ford Thunderbird, which was named Car of the Year. student initiative success students Not paired who students

FULL CIRCLE

For nearly 30 years, Veronica Killebrew has steered college students to success. A longtime veteran of an array of programs aimed at improving student performance, Killebrew knows better than most the commitment, hard work and hope necessary to take students from their first year to graduation. So when she was approached last summer about helping to build Warrior 360, Wayne State University’s hopeful new student success initiative, Killebrew readily embraced the opportunity.

“I have worked in student success for over 28 years, and I believe my calling is to help students — especially those from marginalized backgrounds — achieve their academic goals,” Killebrew said. “When the framework for Warrior 360 was drafted, the administration looked at the best practices to carry over into it. I was asked to become part of the Warrior 360 leadership team to implement those best practices and support the evolution of this new model.”

Where previous programs have attempted to serve specific groups within the student body, such as incoming freshmen, the recently launched Warrior 360 initiative is designed to be the most ambitious and comprehensive student success effort that the university has launched to date, aiming to serve eligible students at every class level and in each discipline throughout the university. Not only are students connected to a slew of academic resources, they are also paired with staff members who serve as “success coaches” and student peers who serve as “success partners,” with both groups working closely to support students inside and outside the classroom.

Equally as important, students in Warrior 360 remain in the program for the duration of their enrollment at Wayne State to better ensure their opportunity to earn their degree.

“I’d like to help establish the notion of being and feeling supported within each student under our care,” explained Latonia Garrett, WSU’s director of student success initiatives and academic partnerships, who oversees Warrior 360. “To that end, I envision a graduation-focused framework and system of support that partners with students through professional coaching; peer partnerships; and high-touch, care-driven performance monitoring. I envision that Warrior 360 will be central to our students’ experiences and forever a part of how they remember their time at Wayne State.”

Likewise, Garrett has worked to keep students at the center of the initiative in a variety of ways, and she’s always looking for new avenues for student involvement. In fact, she said, one of the most distinct aspects of Warrior 360 is its dependence upon student leadership.

“Our student leaders have hosted programs and workshops that have been critical in shaping our relationships with students,” Garrett said. “While this work will continue from our success partners, we also will look to bring students in more to our longer-term planning and pre-first-year programs.”

Peer success partner Nia Jones, a junior majoring in political science, said she relishes the opportunity to work with student peers and to forge relationships that may not always be achievable with older mentors.

“I work with incoming freshmen to familiarize them with campus resources as well as provide a leadership role to them,” said Jones. “I find Warrior 360 to be encouraging because it allows incoming freshmen to talk to someone who has been in their position and familiarize themselves with what the campus has to offer. I also think it creates a new relationship in the process with someone who is similar in age rather than consulting to someone who is older and may be, in a sense, more intimidating.”

Not unlike the students she works with, Jones said that she has also matured and developed over time, and credits her work in Warrior 360 as a big part of that growth. “I feel like in my time in this program, I’ve grown as a student and as a person, and I’ve moved closer to my career goals,” said Jones, who came to Michigan in 2017 from her native Steubenville, Ohio.

Along with the student leaders, the other key component of Warrior 360 is the support provided by staff and faculty, many of whom serve as success coaches. For instance, Keanu Respess, a Warrior 360 success coach, said that a lot of her focus revolves around helping students hone their study and time-management skills, teaching them to access university resources and, of course, encouraging their steady academic development and progress.

“As success coaches, we meet with our students twice a month to build rapport,” Respess explained. “My hope for Warrior 360 is that we impart support in such a meaningful way that students feel that they belong at Wayne State, students know that they have the adequate knowledge to thrive and students believe that graduating with a degree is obtainable.”

New Warrior 360 program offers a panoramic view of student success

“I’d like to help establish the notion of being and feeling supported within each student under our care.”

— Latonia Garrett, director of student success initiatives and academic partnershipsThe new Warrior 360 student success program relies on student input, success coaching, and a broad menu of academic and social resources to help participants excel.