The Michigan Student Power Network is a statewide association of progressive and radical students across the state. We work to connect across issues, campuses and identities to learn, collaborate, and strategize together! We are currently active on 8 campuses across the state (Grand Valley, Kalamazoo College, Michigan State, Central Michigan, Wayne State, UMich Ann Arbor, UMich Dearborn, Oakland Community College & Eastern Michigan), and we’re always looking for more folks to connect with!

The MSPN embraces a variety of tactics running from direct action through electoral action, guided by a strong emphasis on training and strategic thinking! At the statewide level this takes the form of peer to peer skills trainings, state wide meetups, regular statewide calls, and cooredinated statewide actions. Currently we are exploring some new potential campaigns focused around cutting tuition rates!!

Email our statewide organizer using the email above! We can connect you with other students working on your campus, a training coming up in your area, or with one of our statewide working groups focused on training, publication, or higher education funding!

Contact us!

mspn414@gmail.com facebook.com/ michiganstudentpower/

Michigan Rises is a space for students and young folks in Michigan to share their perspectives, experiences, and analysis regarding current issues and events, progressive activism, and intersectionality and idenity with each other to build a stronger statewide culture and community.

This issue is the product of many different perspectives and conversations around oppression in organizing communities, and is part of an anctive and ongoing conversation and negoatiation about these issues.

If you’d like to contribute to Michigan Rises in the future, plese contact us!

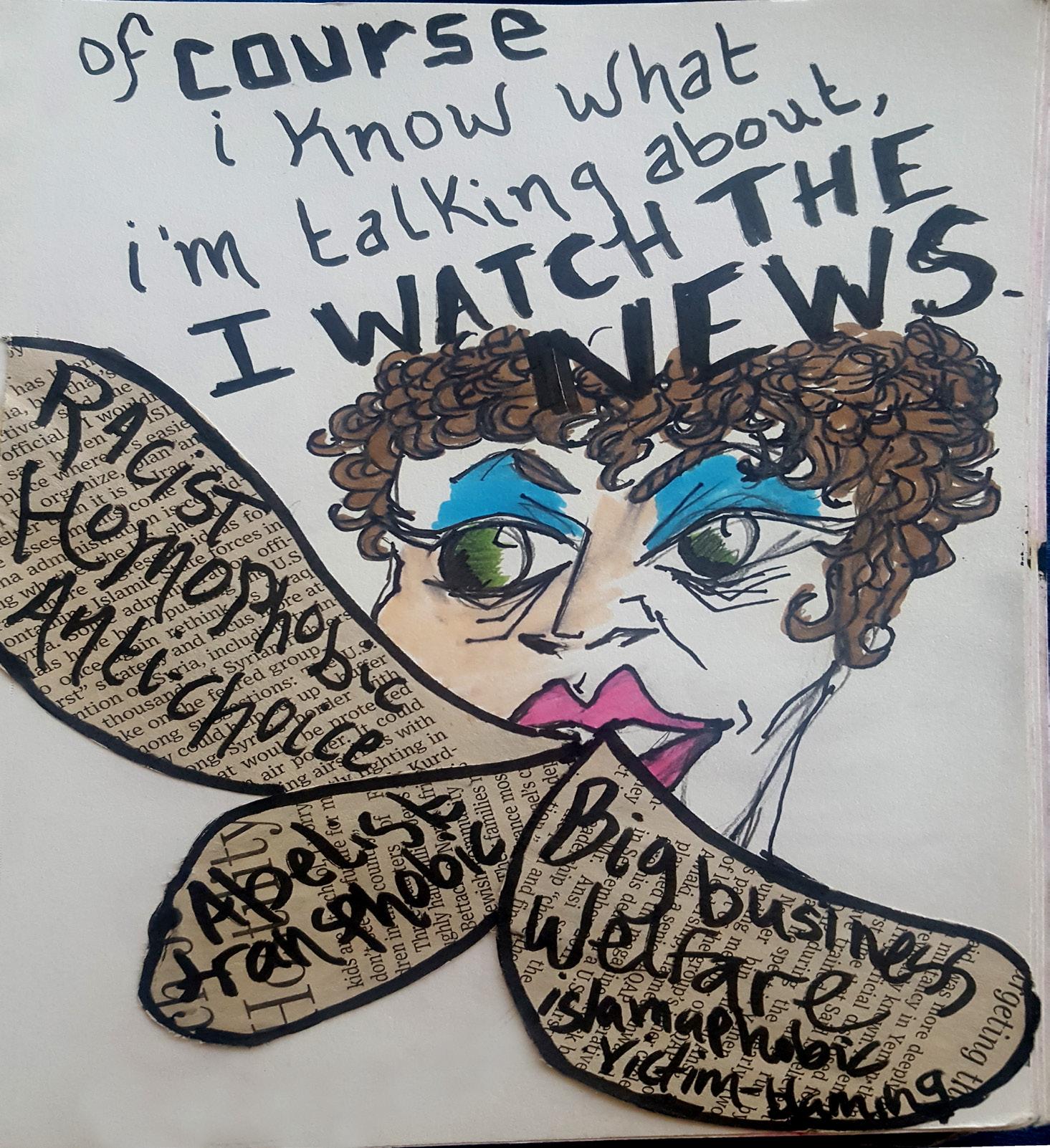

Content and Research for this issue by Aiko Fukuchi, Sariah Metcalfe, and Teia McGahey. Edited by Kelly Garland. Cover Artwork by Cydney Camp.

In the past, U.S. social justice movements have frequently fought in ways that neglect and exclude the voices and needs of people living in the intersections of oppression while acting as if they are speaking on behalf of and working towards the good of everyone, despite gains they made for some. Not only do these harmful patterns in organizing hold us back from achieving the only form of liberation there is, one that liberates us all, it also perpetuates harmful systems of oppression — often the same systems movements claim to be fighting against.

We see this when we listen to the stories of black women who have not only been overlooked by mainstream feminist movements, but who have also had their ideas, practices, and developed through stolen by these same movements. We see this when we study LGBTQ activism in the 1960s that exploited the passion and labor of trans women of color to further demands that would most benefit white, cis gay men and lesbian women coming from backgrounds with more financial stability, while neglecting the demands of those doing so much of the work.

These are only a couple of examples, but the mentality that creates these types of exclusionary movements and perpetuates systems of harm in fights for justice are related. These instances are not separate, but are instead part of a pattern created by both the blindness of privilege as well as the fear that creating a narrative inclusive of too many voices will dilute the message of a movement.

It can be a lot easier to fall into these organizing traps than it is to build a movement that does not exclude the narratives of those most impacted by systems of oppression, impacted in multiple ways, or impacted in a way that is different than what mainstream narratives portray, especially for those organizing from a place of privilege. This zine gives more of a historical context to the harmful mechanisms described above. It also includes tools to avoid recreating these patterns in your own organizing. Whether or not movements build themselves in harmful and exclusionary ways intentionally or unintentionally, what this zine focuses on is outcome and impact rather than intent.

While meeting goals and improving life for many, as well as setting the framework for so much amazing organizing taking place today and giving many of us a basis of knowledge to build from, many organizers have often failed to include the experiences of those who are intersectionally oppressed, oppressed by multiple forces, and hold fewer dominant identities with fewer ties to privileged spaces and backgrounds. These are a few examples and explanations for how this has played out in different movements. It is important to learn from past movements and histories both in terms of what to embody, how to build power, and what to avoid or what to improve on.

Mainstream and white feminist movements have largely excluded narratives of women with non-dominant identities such as women of color, women with disabilities, transgender women, queer women, gender non-conforming folks, incarcerated women, immigrant women, sex-workers, and low-income women from mainstream and prioritized messaging of the most privileged women in their movements. An example of this can be found during the women’s suffragist movement when Susan B. Anthony (a leader in women’s suffrage movement) was quoted opposing the 15th Amendment in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

They have also largely remained silent if not actively opposed transgender women’s health and rights, and the United States’ history of forced sterilization of many native women, women of color, and immigrant women in the context of reproductive rights or women’s healthcare. Additionally, these movements have remained silent about factors related to and influencing reproductive justice such as economic, educational, environmental and racial justice.

Lastly, many feminist movements continue to hold women of different backgrounds and identities to different sexual standards regarding sexual freedom and ideas of consent and devaluing alternate definitions or expressions of femininity or womanhood than the white, mainstream feminist definition.

“I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman”

- Susan B. Anthony (White Feminist)

Social justice movements and rhetoric often do not make the connection between xenophobia and racism. When people express xenophobia, more often than not they are targeting a specific immigrant group more than all immigrants. We see this today with Trump’s Muslim ban and plans to increase deportations in the U.S.

Xenophobic policies and rhetoric generally do not impact all immigrant groups the same way, targeting different groups throughout history depending on the context. Many movements often differentiate between who “should” or “shouldn’t” be here based on documentation status (i.e. stating that if you have a visa, you are welcome, and if you are undocumented, you are not). This is harmful and upholds into a system that grants visas much easier to people immigrating from certain countries and cultures than others. Additionally, arguing that only immigrants who are “economically beneficial” or “useful” in our society should be allowed to live here upholds capitalist notions of the worth in humans being solely defined by our productivity and objectifies immigrants to being valued as worker and nothing else.

When speaking about immigrant rights, many organizers and movements often use a framework that excludes the experiences of native and black folks. This is frequently done through the narrative that “we are all immigrants”, which discounts many experiences like black folks being brought to the U.S. violently and against their will for slave trade, as well as indigenous peoples who experience genocide and are pushed off of land through an ongoing process of colonization.

Racism operates at many levels in the world around and within us (systemic, interpersonal, and internalized). It is in the fabric of every institution, structure, and system that exists within societies that have been touched by western forces. While every level of racism is under-recognized, systemic racism is widely denied, mostly by those who believe that opportunities come equally to all and all one has to do is “pull themselves up by the bootstraps.”

Many movements have neglected to address racial injustice as an issue which led them to recreate the racial hierarchies that dominate the rest of the world. This meant that feminist spaces, LGBTQ+ spaces, economic justice spaces and others have reflected the injustice that they claimed to be eradicating. Similarly, some racial justice movements have neglected to address intersections such as with gender, sexual orientation, and ability status. We see this historically when we look at the lives and organizing careers of folks such as Bayard Rustin who was continually pushed behind the scenes in the civil rights movement because of his sexual orientation as a gay man.

Other examples can be found when looking at the erasure of the work and energy put into racial justice work by black women and femmes such as Rosa Parks, Ella Baker, and Kimberle Crenshaw. Recent movements and organizations like Black Lives Matter and BYP100, largely focus on black liberation, operate from an intersectional framework and better recognize the lives and work of organizers and activists who have been left out of historical accounts in the past and the need to include them and others who share their identities in all present and future movements.These movements recognize the interconnectedness of all of these struggles. Racism intersects with all other ‘isms’ and forms of oppression because it is in the fabric of our society.

“You didn’t see me on television, you didn’t see news stories about me. The kind of role that I tried to play was to pick up pieces or put together pieces out of which I hoped organization might come. My theory is, strong people don’t need strong leaders.”

- Ella Baker

“500+ years of violence against black and brown communities includes 500+ years of bodies and minds deemed dangerous by being non-normative – again, not simply within ablebodied normativity, but within the violence of heteronormativity, white supremacy, gender normativity, within which our various bodies and multiple communities have been deemed

“deviant”, “unproductive”, “invalid.”

- Patty Berne (sins invalid)

Disability justice (DJ) movements have been known to be historically dominated by white, straight men, often upper or middle class. DJ has a reputation for focusing on issues of physical disability rather than other types such as mental and emotional. Much of the progress that has been made for disability rights has been through litigation and other legal processes which help to legitimize the state and the bureaucratic institutions that work to oppress all of us.

The oppression that has faced people with disabilities closely mirror oppression faced by other marginalized identities, though it is not the same. Forced sterilizations, the removal of children, imprisonment and institutionalization are seen as legitimate reactions to people with disabilities by our governments and other institutions in our society. Ironically however, the DJ movement has largely invisibilized those who are more heavily impacted by this state sanctioned violence by failing to center the voices of disabled people who are also people of color, a part of the LGBTQ community, without a home, formerly incarcerated, had their ancestral lands stolen, etc. White supremacy and ableism are intertwined in a history that is a product of capitalism and colonialism. These forces are all related to patriarchy, heteropatriarchy, classism, and other platforms capitalism used to discriminate so that a power structure could be made.

Exclusion in LGBTQ+ movements frequently pertains to the othering of transgender and gender non binary people by excessively centering the experiences of white cisgender gay, lesbian, and queer people. This maintains structures of oppression by excluding trans and gender queer people from LGBTQ+ spaces and isolates issues related to these individuals from the rest of the community, meaning that in instances of advocacy and recounting of history they are at risk for being erased and further marginalized.

This is exemplified by the retelling of the events at the Stonewall Inn on June 28th of 1969. Marsha P. Johnson (pictured below), a black trans woman living in Greenwich Village, New York was celebrating her 25th Birthday at the Stonewall Inn (one of the few clubs LGBTQ+ people could dance in without fear of harassment from police) when police attempted to raid the club. Johnson as well as well as Sylvia Rivera, a Puerto Rican trans woman, were among the first to resist state tyranny on this night. The events at Stonewall are heralded as the beginning of the United States Pride movement. Despite this, recounting of this event and in popular culture ventures like Stonewall (2015) the role of transwomen of color is erased to center white cisgender gay people.

The problem of erasure persists into the popular political agenda for gay rights. Up until June of 2015 when the United States Supreme court legalized marriage equality discussions of marriage and civil unions took center stage in the discourse related to LGBTQ+ rights. This is often in correlation with the fact that issues like poverty, homelessness, labor discrimination and police violence widely impact people who are marginalized within the LGBTQ+ community itself.

Trans people of color face not only transphobia as a structure of oppression but also racism. They are four times more likely than the rest of the population to be living in extreme poverty. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey reported that 49% of people who responded to the survey reported being verbally harassed because they were Transgender and 58% of respondents who interacted with police reported mistreatment from law enforcement who knew (or thought they knew) they were transgender.

Marsha P. Johnson

Mother of the Trans and queer liberation movement at Stonewall inn, 1969.

Labor organizing in the United States over the course of the last 4 decades has consisted of fights for fair wages and benefits as well as resisting dangerous and oppressive workplace conditions. Victories that have lead to higher wages in some areas, better benefits, and safer more respectful workplace conditions have often been won through the unionization of labor via strikes, walkouts, and boycotts by workers and supporters. Advances in this area has also come from the coining of terminology (such as Intersectionality and Sexual Harassment) that can be used to identify issues in the workplace. These issues intersect with discrimination based on forms of oppression in addition to class status. Other forms of marginalization such as physical inaccessibility and language barriers can add more strain to working conditions that are already oppressive due to previously discussed structures like sexism, racism, homophobia, and transphobia.

The Fight for 15 movement started off with 200 New York workers in the fast food industry who were empowered by of the understanding that a 15 dollar minimum wage should be a standard across the United States. These workers went on strike for the first time in history, demanding at least $15 an hour and the right to unionize. Since then the movement has expanded to other cities and other professions.The Fight for 15 has won victories in Seattle, Washington, Los Angeles, California, New York and the District of Columbia. Typically these wins include a gradual increase of wages until the full dollar amount is instituted. The Fight for 15 victories unfortunately do not better the work experiences of all wage earners specifically those who work in serving within the food industry wherein they can be paid between $2.77 and $5 an hour because they can claim tips.

In September of 1965 Filipino-American members of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (which would later become the United Farm Workers in 1966 after a merger with the National Farm Workers Association) began striking against Delano Area grape growers in protest of poor wages and workplace conditions. They asked the National Farm Workers Association (a predominantly Latinx Organization) led by Cesar Chavez, to join the strike. Eight days later on Mexican Independence day (September 16th), the two groups would join together for what Caesar called a nonviolent strike that would include a boycott of Delano area grapes, and a 300 - mile march from Delano, CA to Sacramento, CA. This action lasted for more than two years. In February of 1968 to recenter the actions in nonviolence, Chavez went on a hunger strike for 25 days.

In 1970 Table grape growers (not necessarily including growers of grapes for wine) signed union contracts for the first time that would grant workers better benefits and pay. Before this, many other labor rights campaigns had failed due to different races of people working in the grape growing industry being pitted against each other by racist corporate leaders in order to disrupt their organizing.

In the 1970s, as the women’s movement was growing, one of the tasks undertaken was to address sexual harassment in the workplace. Per the Time Magazine website, the term was coined in 1975 when Camita Wood a former employee of Cornell University filed for unemployment benefits after having to resign from her job due to uninvited touching from her supervisor after being denied a work transfer. From these events the Working Women United group was formed between women’s right activists, Wood and Cornell’s Human Affair’s Office. The discussion of sexual harassment in the workplace became a bigger part of public discourse when Anita Hill testified against Clarence Thomas who was then a Supreme Court nominee (now a Supreme Court Justice) in 1991.

* a statement, action or incident regarded as an instance of indirect, subtle, or unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalized group such as a racial or ethnic minority.

Many of our movements for justice have operated within vacuums and focused on achieving goals for a particular identity. This serves to recreate many of the oppressive forces we seek to destroy within our own movements for justice. These include trusting the perspectives and ideas of folks holding the most privilege in a group over others and giving leadership, speaking roles, and greater access to decision-making positions to those who aren’t as negatively impacted by systems of oppressions as opposed to those on the frontlines.

Interrupting or talking over women, femmes, transgender folks, and gender nonconforming people

‘Mansplaining”

Expecting women to take care of background, “less glamorous” tasks while men and masculine-identified folks take the visible roles (i.e being the face of an group and its work)

Not providing childcare at actions or meetings

Assuming gender pronouns

Doing actions that put immigrant folks (especially undocumented folks) at risk (exposure to the state, etc.) without taking this into consideration, getting the consent of these people about doing this, providing adequate protection and post-action assistance, resources and assistance.

Using language like “illegal” or “alien”

Only being accepting of immigrants with visas and documentation

Not providing information in multiple languages

Referring to racial minorities as “other”

Believing that your organization knows what is best for racial justice actions or movements

Tokenizing the experience of POC members in your organization

Not making meeting spaces accessible

Failing to keep in mind that some people can’t participate in physical direct actions the way others can

Using abelist language

Not prioritizing healing and wellbeing of members/ overworking people.

Not paying people for their labor

Charging dues or fees for membership, conferences, travel, or other expenses that are mandatory (without offering substitute payment options)

Asking people to do work without thinking about what it will cost them financially

This list was created from information compiled in a series of conversations, interviews and research conducted between many organizers. The list is not all inclusive but was instead created with the intent to provide a basis for folks organizing with privilege either within themselves or in communities they’re working with to begin reflecting and improving themselves as organizers and people and add to/adjust depending on context and need.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12.

Be transparent with your intentions and where you are personally and in terms of your political organizing development and awareness.

Use accessible language to the best of your ability.

Be aware of the fact that everyone holds knowledge in different forms from different backgrounds. All are important and valuable.

Ask questions, listen, reflect on, and internalize people’s responses and words. This is a long-winded way of saying to hear and value others and their opinions when they are shared with you.

Listen and think before criticizing people or their work. Make any negative feedback you offer constructive and give it with the intention of building others up, rather than pulling them down or putting yourself above.

Thank people for their energy and work.

Compensate people for their energy and work. Good alternatives to monetary compensation are trading resources and attending/ volunteering at others’ events.

Do not put the responsibility of changing a group or making it more inclusive of non-dominant identities and struggles onto those in the group holding marginalized identities. Instead, help them do this by giving them what they need, helping them problem-solve for resources, offering yourself as a support and listening to what is needed to change the group/organization for the better.

Raise marginalized perspectives being neglected in discussion, especially when those folks are not in the room to advocate for themselves.

Know the difference between being inclusive and not actively be exclusionary.

Practice restorative/transformative justice when appropriate.

Practice enthusiastic consent in your organizing. (With assigning tasks, creating projects, forming actions).

Respect other’s space, need for, and forms of self-care. Do not make assumptions about people’s self-care. Do not assume that someone is less dedicated to a movements/org/issue becausetheir self-care process looks different from yours.

Take time to figure out what self-care means to you and consistently prioritize this.

Do not put the responsibility of explaining the perspectives and experiences of marginalized identities on those individuals in a group who hold those identities. This can be exhausting and tokenizing for those folks.

Be careful to not identify specific individuals and cases as “the problem” and detach them from their socio political, economic and cultural contexts. Include surrounding legal, political, cultural forces/ policies that contribute to problems in your analysis.

Make sure to reflect the above ideas in your ways of thinking when engaging with changes you are fighting for as well as against.

Define what respect means within your group. Doing this may include developing group norms, holding one or multiple discussions, etc.

Take time to accomplish things in a way that reflect the values you and your org envision as aspects of the type of society you are fighting for (even if it is more difficult, even if it is a longer process).

Be aware of and respect non-traditional forms of activism and organizing. Protests and actions are often not accessible to many people for different reasons. Keep in mind the many acts of justice being committed that may not show up on your social media or in the news. Examples of these acts can be investing in one’s community in different ways, choosing not to support certain businesses, writing books, making art, standing up for our values in our person, work, and other relationships, helping someone leave an abusive situation, and simply surviving. Capacity, interest and ability for different acts of social justice change depending on the state of one’s life and their accessibility to such things.

Donate to organizations and work led by folks of marginalized identities.

If you are not a frontline organizer of an issue, organize and/or check in with frontline organizers and communities before planning an action about that issue.

Provide childcare at events.

Provide food and replenishing resources and activities at gatherings.

Be strategic with your actions- reflect on energy-level and capacity of others you are working with when deciding on a next step.

In order to make this Zine to be more accessible to folks who are new to conversations about these topics we included a term bank. The following definitions are meant to give readers a basic understanding of the terminology used in the sections mentioned. Different scholars and organizers might define these terms in other ways but the following definitions can provide you with a foundational understanding to support your learning process. It is because of this that they may not explain the cultural or societal implications of some of the listed forms of oppression. We encourage you to use any confusion or curiosity to fuel further exploration.

denotes definitions from Collins English Dictionary

AntiBlack Racism: racism that manifests within communities of People of Color against people who are black and/or who have darker skin

Cisgender: a person whose gender identity corresponds to their assigned birth gender

Drag Queen: a male [identifying] entertainer who [performs] while wearing traditionally feminine clothes

Related terms: Drag King: A female identified person who is performing while wearing traditionally masculine clothes

Erasure: the removal, loss, or destruction of something [in this context the removal of the of Transgender and People of Color’s contributions to the LGBTQ movement from greater discourse about the movement]

Gender Nonbinary: Binary refers to something that is “made up of two parts or things. Gender nonbinary refers to genders that do not exist exclusively within the male or female binary

Heteronormativity: relating to, or based on the attitude that heterosexuality is the only normal and natural expression of sexuality (Merriam-Webster)

Homophobia: intense hatred or fear of non-straight people or of homosexuality

Immigration: the coming of people into a country in order to live and work there

Intersectionality: the concept that when trying to understand the experiences of Black women, one can not do so without taking into account that issues of race will intersect with racism thus giving them a unique type of lived experience. The term was originally coined by Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989 for this reason and has since been expanded to also grapple with the idea of other parts of a person’s identity impacting their lived experiences all at once by shaping the way they experience oppression.

Internment: the practice of putting people in prison for political reasons [such as during wartime, these people then become internees]

Internment Camp: a camp for the imprisonment of internees, especially during wartime

Marginalized Groups: groups of people that are not Cisgender, Straight, White, or Male identified Related Terms: Non-dominant Identities

Marriage Equality: the State of having the same rights and responsibilities of marriage as others, regardless of one’s sexual orientation or gender identity (The Random House Dictionary)

Othering: the act of treating someone who is marginalized as a person who is not equal to someone else.

PoC: people of Color, this abbreviation refers to all folks who do not self-identify as only white, such as folks who identify as Black, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous, and or Multiracial. Similar abbreviations might include: WoC (Women of Color), MoC (Men of Color) and QTPoC( Queer, Trans People of Color)

Queer: historically used as a slur word to dehumanize LGBTQ+ people, it is a word that is being reclaimed by members of the LGBTQ+ community to refer to sexual and romantic identities that are not heterosexual

Reproductive Justice: justice work relating to reproductive rights

Sanctuary City: a name given to a city in the United States that follows certain procedures that shelter [undocumented] immigrants(Aspen Law Offices, LLC.)

Transgender: noting or relating to a person whose gender identity does not correspond to that person’s [gender assigned at birth] (Random House Dictionary)

Transmisogyny: the negative attitudes, expressed through cultural hate, individual and state violence, and discrimination directed toward trans women and trans and gender nonconforming people on the feminine end of the gender spectrum (Everyday Feminism: Transmisogyny 101)

Transphobia: intense hatred or fear of transgender people.

White Feminism: feminism that primarily centers the problems and experiences of white cisgender women. This is feminism that is not intersectional. Related Terms: Mainstream Feminism

White Supremacy: the theory or belief that White people are innately superior to people of other races.

Xenophobia: hatred or fear of foreigners or strangers and of their politics or culture.

Before you put an “I Voted” sticker on Susan B. Anthony’s grave, remember she was a racist, Lampen, Nov. 2016 (https://mic.com/)

8 Shocking Facts About Sterilization in U.S. History, Garcia, July 2016 (https://mic.com/)

Responding to Transgender Victims of Sexual Assault, Office of Justice Programs, June 2014 (https://www. ovc.gov/ pubs/forge/sexual_numbers.html)

#FTF: Millennials Co-opting Intersectionality- The New Way to Say ‘My Feminism is Better Than Yours’ Martin, July 2015 (http://www.feministcurrent.com/2015/07/24/ftf-mil- lennials-co-opting-intersectionality-the-newway-to-say- my-feminism-is-better-than-yours/)

Black Women and the Suffragist Movement 1848-1923, Wilson and Russell, 1996 (http://www.wesleyan.edu/ mlk/ posters/suffrage.html)

The History of Immigration Policies in the U.S., NETWORK 2017 (https://networklobby.org/ historyimmigration/)

We Want a Hate-Free City, Mehrdad Ali, 2016 (https://socialistworker.org/2016/12/07/we-want-a-hate-freecity

4 Myths About Undocumented Immigrants That Are Hurting Feminism, Lopez, February 2016 (http:// everydayfeminism.com/2016/02/myths-about-undocumented/)

7 Things Undocumented Immigrants Worry About That US Citizens Don’t, Lopez, June 2016 (http:// everydayfeminism.com/2016/06/7-things-undocumented-worry-about/)

This is Disability Justice, Lamm, Sept. 2015 (https://thebodyisnotanapology.com/magazine/this-is-disabilityjus- tice/)

Undoing Racism and Anti-Blackness in Disability Justice, Brown, 2015 (http://www.autistichoya. com/2015/04/undo- ing-racism-anti-blackness-in.html)

Disability Justice - a Working Draft, Berne, June 2015 (http://sinsinvalid.org/blog/disability-justice-a-workingdraft-by-patty-berne)

A Problem for the Movement: Martin Luther King, Jr., Bayard Rustin and LGBT People, HRC Staff, January 2015 (http://www.hrc.org/blog/a-problem-for-the-movement- martin-luther-king-jr.-bayard-rustin-and-lgbt-pe)

Who Is Sylvia Rivera?, Sylvia Rivera Law Project, 2017 (https://srlp.org/about/who-was-sylvia-rivera/)

The White Racial Frame and the Old Patriarchal Frame: Are They Interrelated?, Racism Review, March 2011 (http:// www.racismreview.com/blog/2011/03/13/the-white-racial- frame-and-the-old-patriarchal-frame-arethey-interrelated/)

Meet the Trans Women of Color Who Helped Put Stone- wall on the Map, King, June 2015 (https://mic.com)

Transphobia, TFODE (http://enc.tfode.com/Ciscentrism)

Why Transgender People Are Being Murdered at a Historic Rate, Steinmetz, Aug. 2015 (http://time.com)

Estimate of Transgender Population Doubles to 1.4 Million Adults, Hoffman, June 2016 (https://www.nytimes. com)

You Need to Work 50 Hours A Week to Stay Out of Pover- ty on Minimum Wage, Vasilogambros, May 2015 (https:// www.theatlantic.com)

Column: Why a $15 Minimum Wage Shouldn’t Scare Us, Komlos, Aug. 2016 (http://www.pbs.org)

How the $15 Minimum Wage Went From Laughable to Viable, Greenhouse, April 2016 (https://www.nytimes. com)

One Map Shows Where You Can Still Be Fired for Being Gay in 2015, McKay, June 2015 (https://mic.com)