Queering REPRODUC

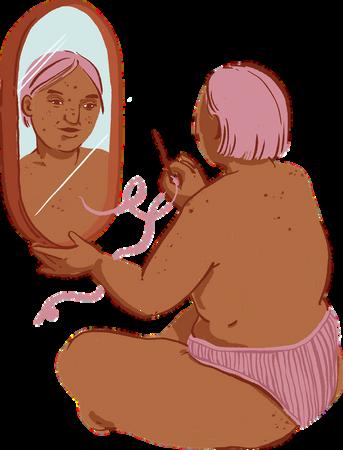

This zine is designed for Black, Indigenous and other people of color within 2SLGBTQ+ communities.

2SLGBTQ+ includes Two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and more!

You may be considering assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and want to better understand how our communities form families.

ARTs include, but are not limited to, in vitro fertilization (IVF), insemination (IUI), and surrogacy.

The experiences in this zine are from community members in Ontario, Canada and primarily focus on IVF and IUI. Some stories include surrogacy experiences. We’re grateful for all of the stories, community knowledge, and advice that community members have shared with us.

QTBIPOC includes: Queer, transgender, Black, Indigenous, people of colour

“This project started with my own family expansion journey, and eventually became my doctoral research. For me, being queer has expanded the meaning of kin and kinship. It taught me to break free of heteronormative definitions of family and redefine what family means on my terms. My community also taught me about queer time: that our lives aren’t always linear. A non-linear timeline does not make me panic at all. Instead, I feel heard, held, and understood.”

MichelleTam (she/her)

queer,pansexual, Asian cis woman

QueeringReproductiveAccess information and advice sourced community members. It’s arrang one another. Read them in whate Please take what is helpful to you

You’ll also see pen names of some community members that we talked to. These were either names they chose themselves or asked us to make for them. Each quote is followed by the self-identified demographic information of the person quoted.

This project is funded by the Lesbian Health Fund and the Centre for Sexual and Gender Minority Health Research.

Many community members stressed how important it is to do thorough research before starting the process.

Healthcare providers won’t always guide you or answer all your questions. Your research could include seeking guidance from friends, family, community members, traditional knowledge keeps, Elders, legal professionals, online groups, and more.

What are your needs?

What are your desires?

Is there a timeline?

What other conditions are important for you? (e.g., social, physical, financial, community, familial)

What is your ideal method of conception?

How flexible are you in achieving your goals?

What are your priorities?

Who do you want to be involved in the process?

This can be a long process that moves slowly. You’ll want to gather as much information as you can while you wait.

“If you're thinking about family expansion possibly in the next few (3-5) years, get yourself on some waitlists because it might take that long.”

Sasha (they/them)

queer, non-binary, mixed race South American & white

Queer Conception: The Complete Fertility Guide for Queer and Trans Parents-to-Be by Kristin Liam Kali

Queer + Pregnant: A Pregnancy Journal by Jenna Brown

Intrauterine insemination (IUI): sperm is inserted into the uterus of the intended pregnant person

Intracervical insemination (ICI): sperm is inserted into the cervix (the passageway to the uterus) of the intended pregnant person (done at home or in clinic)

In vitro fertilization (IVF): egg and sperm are combined outside the body, then an embryo is transferred to the uterus

Reciprocal IVF: egg of one partner is combined with sperm, then the embryo is transferred to another partner’s uterus

Egg freezing: retrieving eggs to be frozen for IVF in the future

Sperm freezing: retrieving sperm to be frozen for IUI or IVF in the future

At first we were like, “There’s no reason to do fertility testing until we get a donor.” And pretty much every single person we talked to since has said, “just go do it.” You’re going to be waiting a long ass time! You’ll want to have that information in your back pocket. This process takes so long and can feel really isolating along the way. So start early and look at everything.

Sam (they/them)

Two-spirit and trans mixed race Anishinaabe-Métis and white

A major part of your research will be calculating the many costs associated with assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Some fertility clinics will include pricing on their website, but many do not. You can call to ask about price, or set up a consultation appointment (covered by OHIP).

ART can be very expensive, this is a part of what we call queer tax.

Queer tax is the additional financial, labour and time costs, gatekeeping, and emotional burdens that 2SLGBTQ+ people face while going through the fertility process.

One round of IVF can cost between $15,000-$25,000, and one round of IUI can cost between $1,000-$4,000, this does not include the cost of medications.

Some fertility clinics have programs and cycle monitoring to support at-home insemination aka do-it-yourself (DIY). There are also FDA approved at home insemination kits (i.e. Mosie Baby) available online.

“It’s important to create a realistic budget, which you can do by getting information from as many people as possible about how much they’ve spent on different parts of the process and what the required costs are. Budget an additional 10-20% of your total cost for unexpected costs”

Laura (she/her) lesbian Latina cisgender woman and Zafiro (she/her) gender fluid lesbian Latina woman

Ontario residents with a health card are eligible for the Ontario Fertility Program, which offers:

Unlimited cycles of artificial insemination (AI), including intra-uterine insemination (IUI)

One cycle of fertility preservation (FP) for medical reasons (sperm or egg preservation), per patient per lifetime

One cycle of in vitro fertilization (IVF) per patient per lifetime

One egg retrieval attempt. However, all the eggs from that retrieval can be fertilized and frozen within the covered cost. Each embryo transfer is also covered.

“I don't think many people realize that every embryo that you get from that cycle is funded. So if you get 12 embryos, all of those transfers are funded in the future.”

Sasha (they/them)

queer, non-binary, mixed race South American & white

There are typically waitlists for OFP funding. Each clinic has their own waitlist and waitlist policies. The time can vary from months to years.

OFP does not cover any drugs or medications, sperm washing/ preparation before insemination, purchase, shipping or storage of donor sperm and eggs, counselling by a psychologist or social worker, or various optional tests.

Ontario Fertility Program ontario.ca/page/get-fertilitytreatments

Ontario Fertility Program Factsheet bit.ly/OFPfactsheet

Sperm donation can come from a friend (known donor) or a sperm bank (anonymous donor). There is a very limited amount of BIPOC sperm available in sperm banks.

As of April 2024, there are 21 registered sperm donors in all of Canada. The majority of sperm donors are white. The number of donors fluctuates but the lack of diversity remains consistent.

Health Canada compliant International sperm costs almost 1.5 times more than Canadian sperm. This is significant when doctors recommend that 3-6 vials be purchased at a time.

Health Canada compliant means the sperm/egg donation follows their strict testing requirements.

Some participants found that there were few options when searching for BIPOC sperm internationally.

“We decided to go through a HC compliant sperm bank in the States. We knew that we wanted either a South American, Caribbean, or Black donor. We were also looking for negative CMV status, just in case either one of us were CMV positive. And that got us down to two people. ”

queer, South Asian, non-binary

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a common virus, related to herpes, that can affect anyone. CMV positive means you have been infected at one point and your body has created antibodies to protect you. CMV negative means you have never been infected. If a CMV negative pregnant person contracts CMV, it can be potentially dangerous to a developing fetus.

Most fertility clinics in Canada require fertility counselling for IVF and third party reproduction. This is controversial because it is not required by federal laws, but is used by fertility clinics to defend themselves against potential legal action. This session is also an additional cost for folks going through an already expensive process.

Many community members felt like these sessions were gatekeeping parenthood, since a report needed to be written about them and submitted to the fertility clinic before they were “approved”.

Gatekeeping is the attempt to control who gets access to resources, power or opportunities, and who does not.

Community members also felt that their physicians did not even read the report afterwards, and that the whole process was just another “checkmark” on their list.

It was just shocking. Within two minutes of being on Zoom with this counsellor, she's like, “On a scale of 1 to 10 rate your childhoods.” We were like, “What?” One of the next questions was, “Have you experienced any abuse in your life? Physical abuse, emotional abuse, psychological abuse? Just tell me about your abuse.” And it’s like, I've never met you, it's not even clear what the 45 minute appointment is for. You don't really know what the outcome is... to determine whether we're fit to be parents?

Natasha (they/them)

queer, genderqueer, Black Chinese

It’s important to build networks of support throughout the process, from pre-conception to postpartum and beyond. Care networks can include physical, emotional, and spiritual care, as well as traditional knowledges and healing practices.

In this section we offer suggestions for building a care network that includes medical care providers, holistic care providers, mental health support, social support, community care and more.

Fertility clinic team: fertility specialist doctors, nurses, technicians and patient care coordinators

Obstetricians: specialize in the care of pregnant people and delivering babies.

Midwives: provide care and support during pregnancy, labour, birth and the postpartum period. For “low-risk pregnancies” you can choose to deliver at home, in a hospital, or in a birth centre.

Midwives are covered by OHIP, but there may be waitlists depending on your location.

Full-spectrum doulas: community care workers who support the full spectrum of reproductive experiences. Doulas are able to provide 1-1 system navigation support, emotional support and physical support during labour.

Doulas are not covered by OHIP, but may be covered by some health insurances.

Holistic & complementary care providers: may include naturopathic doctors, pelvic floor physiotherapists, acupuncturists, Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine practitioners, medicine people, ceremonial people, etc.

“Acupuncture is an ancestral practice for me and my body really resonates with it, so going to acupuncture once a week helped me feel more in control of the process and provided me with the care I wasn’t getting from the fertility clinic.”

Natasha (they/them)

queer, genderqueer, mixed-race Black Chinese

Mental health support: may include one-on-one therapy, and preconception, pregnancy, prenatal, and postpartum support groups.

“Going through egg freezing, I had to do self-injections. The clinic was a very cisnormative space. The process was not trans inclusive. I felt lucky that I was able to access therapy so I was able to get my own emotional care and support.”

River (they/them)

trans, non-binary, queer, Southeast Asian

Ocama Collective ocamacollective.com

Perinatal Wellbeing Ontario perinatalwellbeing.ca

Rainbow Health Ontario rainbowhealthontario.ca

Together Waterloo togetherwaterloo.ca

Umbrella Mental Health Network umhn.ca

A combination of biological family, chosen family, friends, and/or community members

It’s important to have a support system, no matter the size. You don’t have to do this alone!

Connecting with others who have gone through the process and who share your identities, experiences, and values.

“My biggest advice is to find other people who’ve been through the process and talk to them about it because they will provide you with information, resources, and support from their lived experience that medical practitioners won’t be able to provide.”

Will (she/her)

queer, Two-Spirit, cisgender woman, mixed race Plains Cree and European settler

Finding preconception, prenatal, pregnancy and postpartum support groups (online and in-person)

Birth Mark Virtual Support Group birthmarksupport.com

Family Equality Fertility Peer Support familyequality.org

LGBT Mummies Support Groups lgbtmummies.com

Postpartum Support International postpartum.net

PAIL Network pailnetwork.sunnybrook.ca

Sam (they/them) is a Two-spirit and trans mixed race AnishinaabeMétis and white non-birthing parent who pointed out the lack of supports specifically geared towards parents like them. “There's a wider and wider wedge for the non-birthing parent going through fertility. I'm just really not in the picture in a lot of ways”.

Sam faced transphobia and queerphobia in healthcare settings that failed to acknowledge their parental status and the amount of time, effort and energy they have also devoted to this process. “They consistently forget that I'm trans… They once asked me to check my testosterone and I'm like ’OK, I check my testosterone all the time because I'm on T. Why do you need to know that?’ And they're like, ‘Oh, to check your sperm quality.’ And I'm like, ‘I don't make sperm.’ Or they send me forms that have F as the sex designation on it when that's not my legal sex designation. Even after 6-12 months of being at the clinic, I’m constantly shocked. Their trans competency is extremely low. ”

Sam’s advice for non-birthing parents is to “find people that you can talk to because it’s very easy to remove yourself from the situation, or to defer, or feel disconnected. You may not be experiencing the same hypermedicalization as your partner, but you are just as invested in it.”

The family building process can be emotionally taxing, especially for QTBIPOC individuals who face systemic barriers and erasure. It's crucial to mentally prepare for the toll these challenges may take, and the level of self-advocacy required within medical and legal systems. Community members emphasized the importance of being aware of these obstacles and offered valuable advice on how to navigate them.

Be your own biggest cheerleader and be gentle with yourself along this journey.

Understand there are things that are outside of your control and don’t let them break you.

Remind yourself that you will get through this, and that you have a right to build your family the way you choose.

Don’t compare your journey to others’.

Resist failure narratives. Online forums can be a helpful space for community and knowledge, but the stories shared there will not always be positive. You may need to step back if it becomes too much.

“I stopped reading online groups because there was so much language around failure. Part of queering the process for us was figuring out other ways to talk about trying to conceive that didn’t put the burden of getting pregnant or not getting pregnant onto the body. In our first IUI attempt, I was really nervous and my friend said to me, ‘your body’s perfect and this sperm just has to do it’s fucking job.’ It was exactly what I needed to hear. I was like, how can we find a way to think about this that brings some light and laughter?”

Have low expectations of fertility clinics and understand that, at the end of the day, it is a business.

“They’re not trying to make you feel nice, they’re trying to get shit done. So go in with the attitude of ‘you are providing me a service, this is how we need to work together, I know my rights, you’re not going to fuck with me. ”

Angelo (he/him)

gay South Asian cisgender man

Don’t let interactions with clinics define your experience of building a family.

Understand that you might not find the care you need within institutions like the clinic, but you can still find the care you need and deserve in other places.

“It helped to have the expectation that medical practitioners were not going to ’get’ our sexuality, gender, relationship structure, family makeup, etc. And that it’s okay that they don’t get it. As much as I would like to advocate for change, we don’t need to explain ourselves to them.”

Mingo (she/her)

queer, mixed race Anishinaabe and white cisgender woman

Expect that the process may feel invasive, unnecessary, and discriminatory. Do what you need to get through it. Sometimes that might be focusing on the task at hand and just jumping through the hoops to get to the next step.

“We knew using the clinic would suck. And it did suck, as it was not trans competent. But it was the best avenue we had to get what we wanted, so we had a utilitarian mentality about it. We just have to get what we want right now and brush things off as best as we could.”

Bruno (he/him) pansexual, Caribbean transgender man and Mingo (she/her) queer, mixed-race Anishinaabe and white cisgender woman

Be clear about what your goals are, while being flexible about the process of meeting those goals.

“If timing is more important for you, then you may need to priorize that. I think the openness is good preparation for birthing and for being a parent.”

Sam (they/them)

Two-spirit and trans mixed race Anishinaabe-Métis and white

Be prepared to self-advocate!

“Don’t be afraid to stand up for what is right. It’s not easy, there is a glass ceiling. You may feel that people will not hear you, or that your opinion doesn’t matter. It does matter!”

Angelo (he/him) gay, South Asian, ci

The folks we interviewed shared experiences of racism, queerphobia, and transphobia. They also spoke about how fertility clinics often prioritize profit and efficiency over personalized care. These community members had to do a lot of self-advocacy to get the care they needed. Here is some advice they wanted to share with you.

There are no “bad” questions.

“You have to remind medical providers that you have no idea what the fuck is going on and you really need to know.”

Zehra (they/she)

queer, genderqueer, Indo-Caribbean

You always have the right to change providers or ask for a second opinion.

You know your body best! You can always question or refuse a clinician’s course of care if it goes against your embodied knowledge.

Build relationships with different providers. Not all medical practitioners will be able or willing to answer your questions, and one way to ensure you get the answers you need is by building relationships with clinical support staff.

”Find someone that you can make a connection with in the clinic, even if it’s just a receptionist. It feels like you're being herded through the process at times. And so, having a bit of human connection can be really helpful.”

Melissa (she/they)

queer, South Asian, non-binary

Pick your battles. Only do what you have the time and energy to do, especially when it comes to correcting people and doing the labour of teaching.

“It was important for me to be intentional about choosing whether or not to correct medical personnel and staff when they misgendered me. It irritated me, but it also cost my time and energy, so it wasn’t always worth it.”

River (they/them)

trans, non-binary, queer, Southeast Asian

Don‘t be afraid to be persistent and repeatedly speak up for what you need. You are entitled to reproductive care!

Keep the receipts! Document everything you can.

“Even take notes for off-the-cuff conversations that you have on the phone or during an appointment. It's helpful to follow up in person because people change their minds, forget, and/or lie. Have those things in writing, regardless of whether or not they respond to it. Black women, in particular, are often not believed. We have to do so many things to prove ourselves. To prove that we're being genuine, that we're being honest, that we're being transparent, all sorts of shit. And so, for me, it's become an important practice to document everything.”

Erika-Ré (they/she) non-binary, Black queer femme

Know that, no matter what, you deserve support. Find outside help if you need to. There are organizations, community-based groups, mental health and health care professions who know these systems and work in support roles for BIPOC and 2SLGBTQ+ people. Some may have costs, but some are free!

Queerness invites us to invent and imagine beautiful futures for ourselves, our families and our communities.

While we’ve shared stories about many challenging experiences, community members also wanted to share the hope, kindness, and strength involved in the process. For many, the end result of a child made it all worth it.

Years down the road, or even months after birth, some shared that they almost forgot about the tough reproductive process until this storytelling. They were living in the present and basking in the joys of queer parenthood.

Remember that you will get through this. There are so many queer families before you, behind you, and all around you, cheering you on!

“Trust in the process, even if that means needing to pause and rest. It takes time, and sometimes time helps to heal some parts of you that will heal other parts of you later.”

Aneesa (she/her)

queer, Indo-Carribean, cisgender woman

“QTBIPOC families exist, we are out there, and we've done this. There are people who were in your shoes before and now have families. You’re going to be okay!“

Zehra (they/she)

queer, genderqueer, Indo-Caribbean

Michelle Tam, MA (she/her), Ph.D. Candidate, Principal Investigator

I’m a queer Asian researcher who is passionate about LGBTQ2SIA+ sexual and reproductive health, reproductive justice, and technologies. I also work with local social justice organizations and health services.

Ellis Greenberg (they/them), MEd, Research Assistant

I’m a queer, non-binary white settler working to create brave spaces, supportive communities, and networks of care with 2SLGBTQIA+ youth in rural Ontario.

Kitty Rodé (they/them), Graphic Designer

I’m a queer, South Asian artist who is passionate about design and community building. I love helping people share their stories and reach wider audiences.

Gabrielle Griffith (they/them), Doula, Educator, Speaker

I’m a Queer birth-parent of the Afro-Caribbean Diaspora supporting folks navigating the full spectrum of reproductive experiences through community led care work and research.