Katalog vydala Společnost Jindřicha Chalupeckého př příležitosti výstavy Cena Jindřicha Chalupeckého 2022 v Národní Galerii Praha.

Spolupořadatel

Národní galerie Praha

Partneři Společnosti Jindřicha Chalupeckého

Texty

Barbora Ciprová, Veronika Čechová, Anetta Mona Chişa, Tereza Jindrová, Karina Kottová, Olga Krykun, David Přílučík, Vojtěch Radakulan, Martina Drozd Smutná, Ezra Šimek, Jaro Varga

Hlavní partneři

Ministerstvo kultury, Magistrát hlavního města Prahy

Partneři

Redakce katalogu

SJCH

Překlady

Jamie Rose Korektury

studio Datle, Janka Jurečková (slovenský text), Brian Vondrák (anglická korektura)

Produkce katalogu

Ondřej Houšťava

Grafická úprava

Jan Brož

Fotografie

Jan Kolský, Iryna Drahun

Tisk Tiskárna H. R. G.

Státní fond kultury ČR, Městská část Praha 7, Trust for Mutual Understanding, Česká centra, Nadace a Centrum pro současné umění Praha, Moravská galerie v Brně, PLATO Ostrava, Institut umění – Divadelní ústav, Residency Unlimited

Speciální partneři výstavy Biofilms, GESTOR, Rotorama, Textile Mountain, Zlatá loď

Mediální partneři

Artyčok.TV, Art & Antiques, ArtMap, Radio Wave, A2 kulturní čtrnáctideník, Artalk, Flash Art Czech and Slovak Edition, Artikl, RAILREKLAM, GoOut

Výstava a vydání katalogu se uskutečňují za finanční podpory Ministerstva kultury a Magistrátu hlavního města Prahy.

ISBN 978-80-908535-1-5

© Společnost Jindřicha Chalupeckého www.sjch.cz www.ngprague.cz

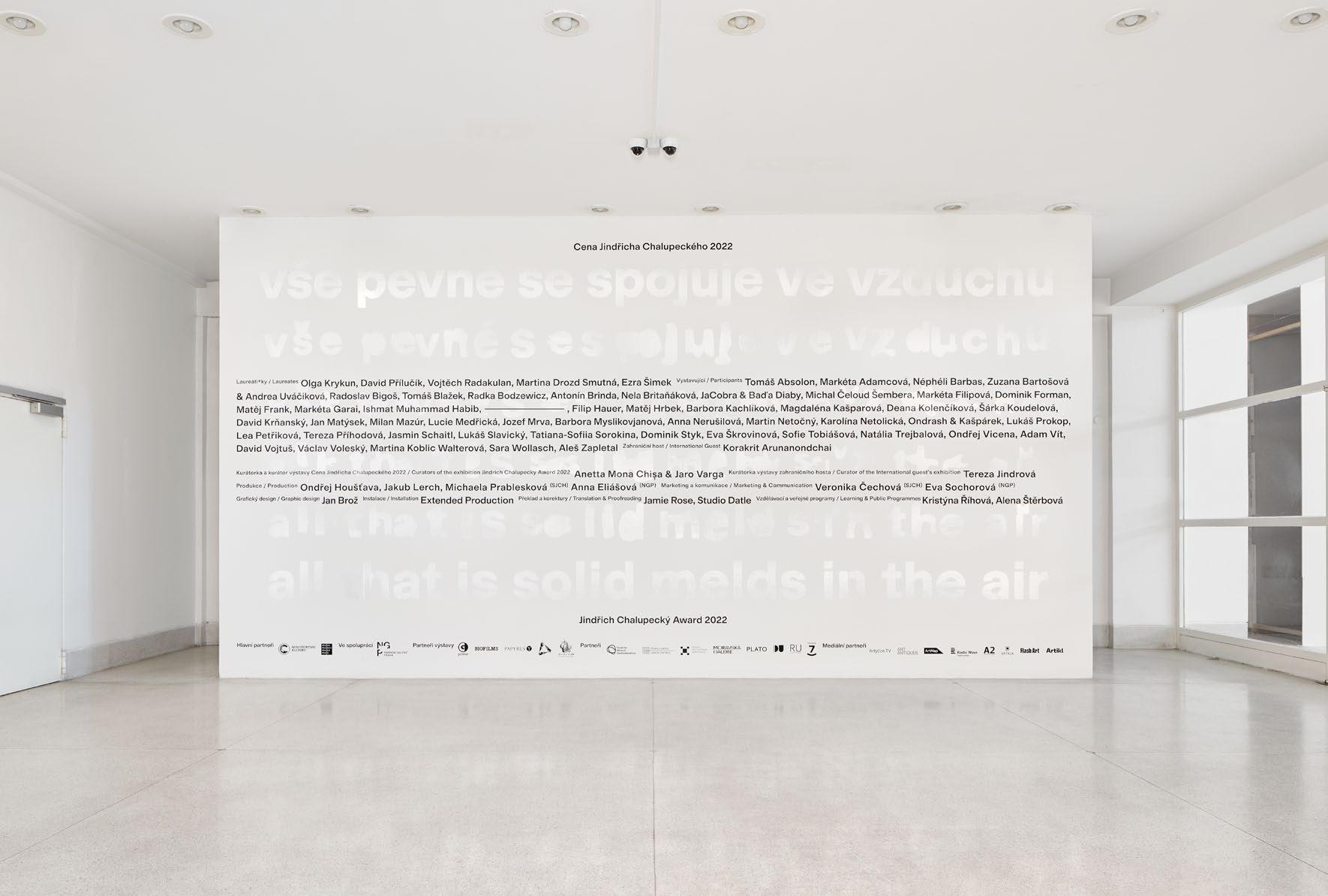

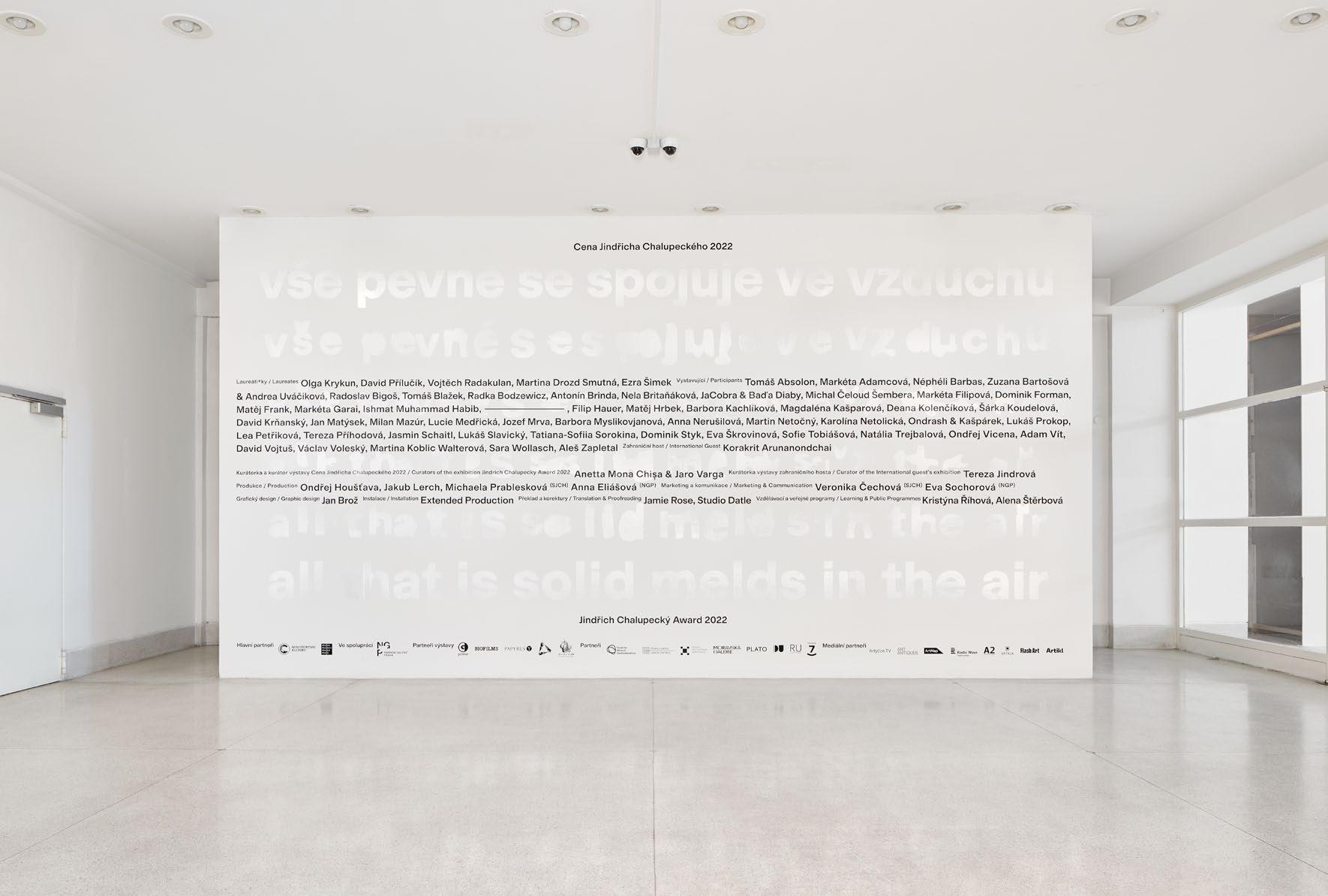

Cena Jindřicha

Jindřich

Chalupeckého 2022 Vše pevné se spojuje ve vzduchu

Chalupecký Award 2022 All That Is Solid Melds In The Air Veletržní palác Národní galerie Praha Trade Fair Palace National Gallery Prague 23 9 2022 – 8 1 2023 23 9 2022 – 8 1 2023

Laureáti*ky / Laureates Olga Krykun, David Přílučík, Vojtěch Radakulan, Martina Drozd Smutná, Ezra Šimek Vystavující / Participants Tomáš

Absolon, Markéta Adamcová, Néphéli Barbas, Zuzana Bartošová & Andrea Uváčiková, Radoslav Bigoš, Tomáš Blažek, Radka Bodzewicz, Antonín Brinda, Nela Britaňáková, JaCobra & Baďa Diaby, Michal Čeloud Šembera, Markéta Filipová, Dominik Forman, Matěj Frank, Markéta Garai, Ishmat Muhammad Habib, Filip Hauer, Matěj Hrbek, Barbora Kachlíková, Magdaléna Kašparová, Deana Kolenčíková, Šárka Koudelová, David Krňanský, Jan Matýsek, Milan Mazúr, Lucie Medřická, Jozef Mrva, Barbora Myslikovjanová, Anna Nerušilová, Martin Netočný, Karolína Netolická, Ondrash & Kašpárek, Lukáš Prokop, Lea Petřiková, Tereza Příhodová, Jasmin Schaitl, Lukáš Slavický, Tatiana-Sofiia Sorokina, Dominik Styk, Eva Škrovinová, Sofie Tobiášová, Natália Trejbalová, Ondřej Vicena, Adam Vít, David Vojtuš, Václav Voleský, Martina Koblic Walterová, Sara Wollasch, Aleš Zapletal Zahraniční host / International Guest Korakrit Arunanondchai

Obsah

Editorial Kurátorský kolektiv SJCH

Všetko pevné sa spojuje vo vzduchu

Anetta Mona Chişa a Jaro Varga

Apolitičnost v umění je privilegiem, který jsem právě ztratila Olga Krykun

Olga Krykun: Letní pomněnky (Літні незабудки)

Pro angažovanost je nezbytná imaginace

David Přílučík: Plemeno

Editorial JCHS Curatorial Team

All That Is Solid Melds in the Air

David Přílučík

Cílem je vidět to, co bychom jinak vidět v realitě nemohli Vojtěch Radakulan

Vojtěch Radakulan: Období osamělých směn, aneb nejdražší muzeum na světě

Selháváme už v tom základním bodě – nejde nám rozumět Martina Drozd Smutná Martina Drozd Smutná: Výběr maleb

Potřebujeme aktivně žít představu světa, který chceme

Ezra Šimek: Veselý Žďár

Ezra Šimek

Korakrit Arunanondchai: Konečnost našich písní proti nekonečnosti času a prostoru Tereza Jindrová SJCH

Vyjádření poroty k výběru umělkyň a umělců

Profily vystavujících

Ceny Jindřicha Chalupeckého 2022

Anetta Mona Chişa & Jaro Varga

Apoliticalness in art is a privilege that I’ve recently lost Olga Krykun

Olga Krykun: Summer Forget-Me-Nots (Літні незабудки)

Imagination is necessary for engagement David Přílučík

David Přílučík: Breed

The goal is to see things we otherwise cannot see in reality Vojtěch Radakulan

Vojtěch Radakulan: The Period of Lonely Shifts, or The Most Expensive Museum in the World

We’re already failing at the basic point – we’re incomprehensible Martina Drozd Smutná

Martina Drozd Smutná: Selected paintings

We need to live the imagination of the world we want Ezra Šimek

Ezra Šimek: Joyful Flame

Korakrit Arunanondchai: The Finiteness of Our Songs Against the Infinity of Time & Space Tereza Jindrová JCHS

Statement of the jury on the selection of artists for the Jindřich Chalupecký Award 2022

Profiles of the participants

Contents

do

10 14 66 72 80 88 96 102 110 120 128 138 146 162 166 11 15 67 73 81 89 97 103 111 121 129 139 147 163 167

Kurátorský kolektiv SJCH

Letošní ročník Ceny Jindřicha Chalupeckého provází hned dvě významné změny. Umělkyně*ci se poprvé hlásily*i do Ceny, která se již oficiálně řídí novými pravidly, v nichž už nefiguruje druhé kolo soutěže o laureátský titul. Pětice umělkyň*ců vybraných mezinárodní porotou se tedy nestává finalistkami*ty, ale rovnou laureátkami*ty, a společná výstava je tak představením a oceněním práce pěti významných uměleckých osobností mladé české výtvarné scény. Těmito osobnostmi jsou v tomto ročníku Olga Krykun, David Přílučík, Vojtěch Radakulan, Martina Drozd Smutná a Ezra Šimek. Společná výstava, která je i letos doprovozena prezentací zahraničního hosta, tentokrát thajského multimediálního umělce Korakrita Arunanondchaie, se koná ve Veletržním paláci Národní galerie Praha. Z téměř osmdesátky portfolií přihlášených do CJCH 2022 vybírala porota ve složení Ivet Ćurlin (Kunsthalle Wien), Anna Daučíková (umělkyně a pedagožka), Charles Esche (Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven), João Laia (Muzeum současného umění Kiasma, Helsinky) a Jan Zálešák (kurátor a pedagog FaVU VUT, Brno). Prohlášení porotkyň a porotců přikládáme v samostatné sekci katalogu.

celoroční spolupráce s pěticí umělkyň*ců, a to jednou či dvěma kurátorkami SJCH, naposledy pak v roce 2021 celým kurátorským kolektivem. Po sedmi letech této – pro nás velmi hodnotné – práce jsme se však rozhodli, že je na čase přizvat k CJCH nové osobnosti a dát příležitost přístupu zvenčí – nejen ke kurátorské práci a uchopení formátu výstavy, ale i k vnímání toho, co Cena pod vlivem dynamických změn posledních let, která jsou zároveň odrazem své doby, může a má sdělovat. A to jak směrem k umělecké scéně, participujícím umělkyním*cům, ale i široké veřejnosti. Této role se ujalo umělecko-kurátorské duo Anetta Mona Chişa a Jaro Varga, kteří do aktuálního ročníku Ceny vnáší řadu důležitých témat a otázek. Vytváří výrazné gesto směrem k současné mladé umělecké generaci, a co vnímáme jako ještě důležitější, dávají podnět k další diskusi.

Editorial JCHS Curatorial Team

Druhou změnou, kterou Cena Jindřicha Chalupeckého 2022 přináší, je pozice externího kurátorského týmu. Letos je tomu 32 let od založení Ceny a od počátků výstav, tehdy označovaných jako výstava finalistek a finalistů CJCH, které zpravidla koordinoval organizační tým Společnosti Jindřicha Chalupeckého, či její ředitelka nebo ředitel. Proměna v tomto směru nastala s nástupem současného kurátorsko-produkčního týmu Společnosti, kdy začaly být výstavy kurátorované a koncepčně vedené v průběhu

Publikace k výstavě Ceny Jindřicha Chalupeckého 2022 vznikla v gesci grafika a vizuálního umělce Jana Brože, který má zároveň nezanedbatelný autorský podíl na prezentaci výstavy, a to konkrétně iniciací samotného názvu. Původní citaci „Vše pevné se rozpouští do vzduchu“, kterou si Brož vypůjčil z titulu knihy Marshalla Bermana, následně kurátorské duo posouvá do lehce pozměněné verze Vše pevné se spojuje ve vzduchu. Tento název se manifestuje také ve výstavě levitující v prostoru Malé dvorany Veletržního paláce.

This year, the Jindřich Chalupecký Award comes with two major changes. For the first time, artists applied for the Award under new rules under which there is no longer a second round for the title of laureate. As a result, the five artists selected by the international jury do not become the finalists but laureates instead, and their joint exhibition is thus a presentation and recognition of the work of five significant artists within the young Czech art scene. These five artists are Olga Krykun, David Přílučík, Vojtěch Radakulan, Martina Drozd Smutná, and Ezra Šimek. The joint exhibition – which this year is also accompanied by the presentation of a foreign guest, the Thai multimedia artist Korakrit Arunanondchai – takes place in the Trade Fair Palace of the National Gallery Prague. The selection from among the almost eighty portfolios submitted for the JCHA 2022 was made by a jury comprised of Ivet Ćurlin (Kunsthalle Wien), Anna Daučíková (artist and educator), Charles Esche (Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven), João Laia (Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, Helsinki), and Jan Zálešák (curator and teacher at the BUT Faculty of Fine Arts, Brno). The statement of the jury is available in a separate section of the catalogue.

the current JCHS curatorial-production team, after which the exhibitions began to be curated and conceptually led during the year-long collaboration with the five artists by usually one or two curators from the JCHS or, in the case of the most recent exhibition in 2021, by the entire curatorial team. However, after seven years of this work, which has been very meaningful to us, we have decided that it is time to invite new personalities into the JCHS and provide an opportunity for access from the outside –not only for curatorial work and managing the format of the exhibition but also for the understanding of what the Award (set in the context of the dynamic changes of recent years, which also serve as a reflection of today) can and should communicate – both towards the art scene and the participating artists as well as to the general public. This role was taken up by the artist-curator duo of Anetta Mona Chişa and Jaro Varga, who bring a number of important topics and questions to this year’s Award. They make a major gesture towards the current generation of young artists and, what we view as even more important, initiate further discussions.

The second change to the Jindřich Chalupecký Award for 2022 comes in the form of an external curatorial team for the exhibition. This year marks thirty-two years since the founding of the Award, and from the very first exhibitions – then referred to as exhibitions of the JCHA finalists –these presentations have typically been coordinated by the organisational team of the Jindřich Chalupecký Society or its director. A change occurred with the formation of

The publication for the Jindřich Chalupecký Award 2022 exhibition was created under the leadership of the graphic and visual artist Jan Brož, who also has had a significant share in the presentation of the exhibition itself, specifically in suggesting its title. Borrowing the original quote “All that is solid melts into air” from the title of a book by Marshall Berman, the curatorial duo then shifted it into the slightly altered version All that is solid melds in the air. This title is also manifested in the exhibition levitating in the Small Hall of the Trade Fair Palace.

Editorial

10

Všetko pevné sa spojuje vo vzduchu Anetta Mona Chişa a Jaro Varga

Pri úvahách o kurátorovaní Ceny Jindřicha Chalupeckého (CJCH) v nás spočiatku značne vibrovali pochybnosti o tom, čo v daných podmienkach (daní umelci*kyne, dané miesto – priestor, jasný kontext, importované rozdielne obsahy) znamená kurátorovanie. Rola kurátorov sa nám javila ešte komplikovanejšia tým, že by sme mali naplniť špecifické očakávanie, ktoré nemalo jasné kontúry: čo predpokladá kurátorovať výstavu umeleckej ceny? Čo znamená kurátorovať cenu bez víťaza*ky, cenu v rámci korej víťazi*ky sú všetci*ky, ktorí*é vystavujú v Národnej galérii? Ke ď sme sa rozhodli zapojiť sa do CJCH pri súčasnom nastavení jej pravidiel a nálady, o zákulisí projektu sme vedeli veľmi málo. Predstavili sme si obraz dynamického moderátorstva, ktoré uvedie do pohybu hru estetík, akcií a síl bez hierarchie. Jedna z definícií charakterizuje “moderátora“ ako osobu, ktorej úlohou je zabezpeči ť, aby diskusia alebo rozprava bola spravodlivá. 1 Inde je „moderátor“ definovaný ako niekto, kto vedie diskusiu, stretnutie at ď. medzi ľu ďmi s rôznymi názormi. 2 Alebo je to jednoducho osoba či vec, ktorá zmierňuje, tlmí. 3 Tak sme sa ocitli v roliach moderátorov, ktorí sa pohybujú na rozhraní medzi piatimi rôzne zameranými

1 „A person whose job is to make sure that a discussion or a debate is fair.“ Pozri https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/ definition/english/moderator [30. 8. 2022].

2 „Someone who is in charge of a discussion, meeting etc between people with different opinions.“ Pozri https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/moderator [30. 8. 2022].

3 „A person or thing that moderates.“ Pozri https://www.dictionary. com/browse/moderator [30. 8. 2022].

umelcami*kyňami (Martina Drozd Smutná, Olga Krykun, David Prílučík, Vojtěch Radakulan, Ezra Šimek), jedným výrazným dizajnérom (Jan Brož), dvoma inštitúciami (Společnost Jindřicha Chalupeckého a Národní galerie) a publikom. Ukázalo sa, že moderátorské metódy by mohli v kurátorskom rámci prispieť k osvetleniu vzťahových podmienok, v ktorých sa odohráva umelecká produkcia, spolupráca a súperenie na poli umenia. Vyšlo tiež najavo, že sme boli naivní a príliš optimistickí, zrejme zaslepení radosťou, že ideme robiť niečo spolu. Naše aktivity sa zaradili niekde medzi komunikačnú prax, sociálne ňuchanie, zmyslové poznanie a spätnú racionalizáciu, interpretovanie slov a tlmočenie faktov, skúseností, pochybností, riešenie technického rámca, statické posudky a gravitačné sily všetkého druhu.

Príbeh CJCH sme chceli odmoderovať ako pojednávanie o súťaži a spolupráci. Zahĺbili sme sa teda do problematiky súťaženia v umení, ale postupne sme zistili, že diskusie o cenách sú vypitvané a že v takom krátkom čase ich nevieme ani dobehnúť, nieto ešte predbehnúť. Pri čítaní textov, ktoré sa už o cenách a súťažení popísali, a zapojení sa do prípravy prezentácie CJCH sme pochopili, že najväčšia diskrepancia je medzi slovami a realitou, medzi tým, čo sa píše/hovorí, a skutkami. Naše snahy vycítiť plodné momenty v prechodnej zóne medzi spoluprácou, kreativitou, rituálom, rivalitou, komparáciou, komodifikáciou a kapitalizáciou nás priviedli k presvedčeniu, že potrebujeme veľké gestá, nie veľké slová. Áno, tiež si myslíme, že vo svete s narastajúcou nerovnosťou by sme mali zvrhnúť súťaživosť – kultúrny a morálny koncept, ktorý uľahčuje autoritatívne prideľovanie moci, legitimizuje odmeny a podporuje meritokraciu. Áno, spoločnosť, v ktorej sú ľudia delení na víťazov a porazených a v ktorej sa odmeny nerozdeľujú rovnomerne, vedie

All That Is Solid Melds in the Air

Anetta Mona Chişa & Jaro Varga

When thinking about curating the Jindřich Chalupecký Award (JCHA), we had considerable doubts about what it means to curate under the given conditions: given artists, given space, clear context, imported different contents. The role of curators felt even more complicated to us due to the pressure to fulfil a certain expectation, the outline of which was vague at best: What does it mean to curate an art prize exhibition? Even more so for an award that has no winners, or rather, where the winners are those who get to exhibit in the National Gallery?

one remarkable designer (Jan Brož), two institutions (the Jindřich Chalupecký Society [JCHS] and the National Gallery Prague [NG]), and the audience. It turned out that the techniques of moderating could be used in curation as ways to help shed light on the relational conditions under which artistic production, cooperation, and competition take place within the art scene. Ultimately, it also turned out that we were naive and overly optimistic, perhaps blinded by the joy of working on something together. Our activities fell somewhere between communication practice, social sniffing, sensory knowledge and retroactive rationalisation, interpreting words and facts, experiences, doubts, sorting out technicalities, static assessments, and gravitational forces of all sorts.

At the time we agreed to be involved in the JCHA under the current rules and approach, we knew very little about the background of the project. We envisioned an image of dynamic moderation that would set in motion a play of aesthetics, events, and forces free of hierarchy. One definition of the word “moderator” is that of “a person whose job it is to ensure that a discussion or debate is fair”. Elsewhere, the “moderator” is defined as “someone who leads a discussion, meeting, etc between people with different opinions”.2 Or, simply, it is “a person or thing that moderates”.3 So, we found ourselves in the role of moderators, navigating the boundaries between five artists, each with a different focus (Martina Drozd Smutná, Olga Krykun, David Prílučík, Vojtěch Radakulan, Ezra Šimek),

1 See https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/ english/moderator. Accessed 30 August 2022.

2 See https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/ moderator. Accessed 30 August 2022.

3 See https://www.dictionary.com/browse/moderator. Accessed 30 August 2022.

We wanted to moderate the JCHA story as a reflection on competition and collaboration. So, we delved into the issue of competition in art but gradually discovered that the discourse around awards runs so deep that, in such a short time, we would not be able to catch up to it, let alone get ahead of it. While reading the texts about awards and competition, as well as being directly involved in putting together the JCHA presentation, we came to realise that the greatest disparity is between words and reality, between what is written/said and what is acted upon. Our attempts to sense fruitful moments in the crepuscular zone between collaboration, creativity, ritual, rivalry, comparison, commodification, and capitalisation have led us to believe that we need grand gestures rather than grand words. Yes, we share the opinion that in a world of growing inequality, competition should be abandoned as a cultural and moral concept which enables the authoritative allocation of power, legitimises rewards, and upholds meritocracy. Yes, a society in which people are split into winners and losers and in which rewards are not distributed equally leads to the failure of cohesion and

14

k zlyhaniu súdržnosti a súčinnosti, k nárastu kompulzívneho narcizmu a materiálnej nerovnosti. Áno, súperenie sa stalo ekonomickým mýtom založeným na viere. Najvyšší kňazi ekonómie sa mylne domnievajú, že je všeliekom, ktorý vždy povedie k hospodárskej a spoločenskej harmónii. Áno, tým sa ignoruje najväčší prínos ľudskej evolúcie, ktorým je spolupráca – hlavný pohon ľudského rozvoja. Áno, je to komplexný problém, keďže v rámci preľudnenosti planéty sa spolupráca javí ako jediná možnosť prežitia.4 Ale čo si v takto nastavenom svete počať a ako sa k tomuto problému postaviť zvnútra? Ako neparticipovať na rituáli kompetitívnosti, ktorý, podobne ako náboženstvo, dramatizuje základné kultúrne hodnoty, performatívne transformuje sociálne úlohy účastníkov*čiek a autorizuje výsledky tým, že ich spája so základným kozmologickým poriadkom?

Ako sa nestať len ďalším článkom v reťazci obetovania, exkomunikovania, požehnania, posvätenia a korunovania?

Napriek tomu, že súťaže sú problematické a kanibalizujú spolupráce, vnímame istý typ vzrušenia, ktoré ceny do často dosť nudnej umeleckej bubliny prinášajú. Čím však nahradiť ceny v umení, alebo ako ich udeľovať tak, aby sme spochybnili nefunkčné kompetitívne usporiadanie sveta? Zrejme sa to nedá dosiahnuť kozmetickým upgradom, ktorý by problém viac neinfantilizoval a neuhladil než riešil.

Nie sme jediní, v ktorých vrie potreba novej citlivosti, nových spoločenských a estetických jazykov, nových mikropolitických praktík, nových spôsobov nahliadania na seba vo vzťahu k druhému, cudziemu, neznámemu. Túto

4 Félix Guattari vo svojej knihe Tri ekológie (1989) upozorňuje na preľudnenosť planéty, ktorá bude vyžadovať nové modely spoločného bytia „group being“, ktorého hlavným motorom bude subjektivita na mikrospoločenskej úrovni. Guattari, Félix: The Three Ecologies London: The Athlone Press, 2000.

naliehavosť chceme sprítomniť tým, že očakávané pretavíme na neočakávané a napneme možnosti stanoveného výstavného formátu. Naším moderátorským cieľom je spájanie nezávislých štruktúr do závislých vzťahov, nakláňanie výstavnej plochy do atypických uhlov, rozkladanie významov a skladanie nových, uvedenie do pohybu nekonvenčnej, neopotrebovanej kauzality. Myslíme si, že kritická reflexia a spochybňovanie zaužívaných vzorcov je cestou k spravodlivejšiemu prostrediu, v ktorom nesúhlas a kritika sú superhodnotami v rámci dialógu a vyjednávania. Zároveň chceme výstavu, ktorá nebude primárne o cene a súťažení, ale o umení ako takom. Výstavu, ktorá bude úvodom nevyspytateľnej5 diskusie, nie jej záverom. Veríme, že dobrou kvalitou umenia je rozochvenie pocitov, podnietenie nečakaných transformácií. Čím viac dojmov, pojmov, záujmov a zdrojov, tým je umelecký diskurz (tak teoretický, ako aj vizuálny) bohatší.

Najprv sme sa pokúsili načrtnúť možnosť väčšieho prekrytia diel laureátov. Výsledkom takto nasmerovaného dialógu by bola extenzia výstavy do spoločného gesta, jednotnej štruktúry, ktorá by vznikla kolektívne. Stále si myslíme, že má zmysel premýšľať transverzálne – posilňovať spoločné/spoločenské a individuálne zároveň. Takýto zámer sa nám však nepodarilo zreálniť kvôli príklonu laureátov*iek sústrediť sa radšej na vlastné diela, bez prerastania do spoločných rovín. Prešli sme si portfóliá všetkých

synergy, to an increase in compulsive narcissism and material inequality. Yes, competition has become an economic myth built on faith. The high priests of economics mistakenly believe that competition is a panacea that will always lead to economic and social harmony. Yes, this ignores the greatest contribution of human evolution – cooperation, which is the primary driver of human development. Yes, it is a complex problem since, as the planet becomes overpopulated, cooperation appears to be our only path for survival.4 But what do we do in a world that is set up in this way, and how do we deal with the issue from the inside? What can we do to refrain from participating in the ritual of competitiveness that, like religion, dramatises basic cultural values, performatively transforms the social roles of participants, and authorises the results by setting them within the basic cosmological order? How do we avoid becoming just another link in the chain of sacrifices, excommunications, blessings, consecrations, and coronations? Yet, although competitions are problematic and cannibalise collaborations, there is a certain type of excitement that awards bring into the often boring bubble that is art. But how do we replace art awards, or how do we distribute them in a way that remains critical of the dysfunctional competitive world order? Clearly, this cannot be achieved through a simple cosmetic upgrade, which would do more to neutralise and infantilise the issue than to solve it.

the other, the foreign, the unknown. We want to make this urgency felt by turning the expected into the unexpected and stretching the possibilities of the established exhibition format. Our goal as moderators is to combine independent structures into dependent relationships, tilting the exhibition space at atypical angles, deconstructing meanings and constructing new ones, setting an unconventional and fresh causality into motion. We believe that critical reflection and questioning of established patterns is the way to a fairer environment in which disagreement and criticism are the guiding values of dialogue and negotiation. At the same time, we want an exhibition that won’t be primarily about the award and competing but instead about art as such – an exhibition that will kick off an unpredictable5 discussion rather than conclude it. We believe that one of the positive aspects of art is stirring up feelings and prompting unexpected transformation. The more impressions, interests, inclinations, and ideas integrated into the exhibition, the richer the artistic discourse (both in theory and in visuals) can become.

umelcov*kýň a vyvstala

5 Hana Janečková uvádza, že „nevyzpytatelnost lze totiž vnímat jako nástroj jiného způsobu života, musíme se ale kriticky ptát, jak se umění využívá především ze strany uměleckých institucí, a do čeho vkládáme čas a sdílené zdroje umělkyň a umělců”. „... do středu institucionálního provozu umístníme širší ekologii vztahů s umělkyněmi a umělci, veřejnosti a komunitami…” Janečková, Hana: A Useful Art Award. Cena Jindřicha Chalupeckého 2020. Ostrava: Společnost Jindřicha Chalupeckého, 2020.

We are not the only ones burning with the need for a new sensibility, new social and aesthetic languages, new micro-political practices, new ways of seeing ourselves in relation to

4 In his book The Three Ecologies (1989), Félix Guattari draws attention to the overpopulation of the planet, which will require new models of shared being, “group being”, based around subjectivity at the micro-social level. Guattari, Félix: The Three Ecologies

The Athlone Press, London, 2000.

First, we tried to outline the possibility of greater overlap between the laureates’ works. The result of such a directed dialogue would be the extension of the exhibition into a common gesture, a unified structure that would be created collectively. We still believe that it makes sense to think transversally – to emphasise the shared

5 Hana Janečková states that “the unpredictability of art can be seen as a tool for living otherwise. We must then critically ask about the way art is used, especially by art institutions, and to what ends the artist’s time and shared resources will be channelled [...] we put a wider ecology of relationships with artists, publics and communities at the centre of institutional operations.” Janečková, Hana: “A Useful Art Award”, Jindřich Chalupecký Award 2020 Jindřich Chalupecký Society, Ostrava, 2020, p. 314–315.

16

prihlásených

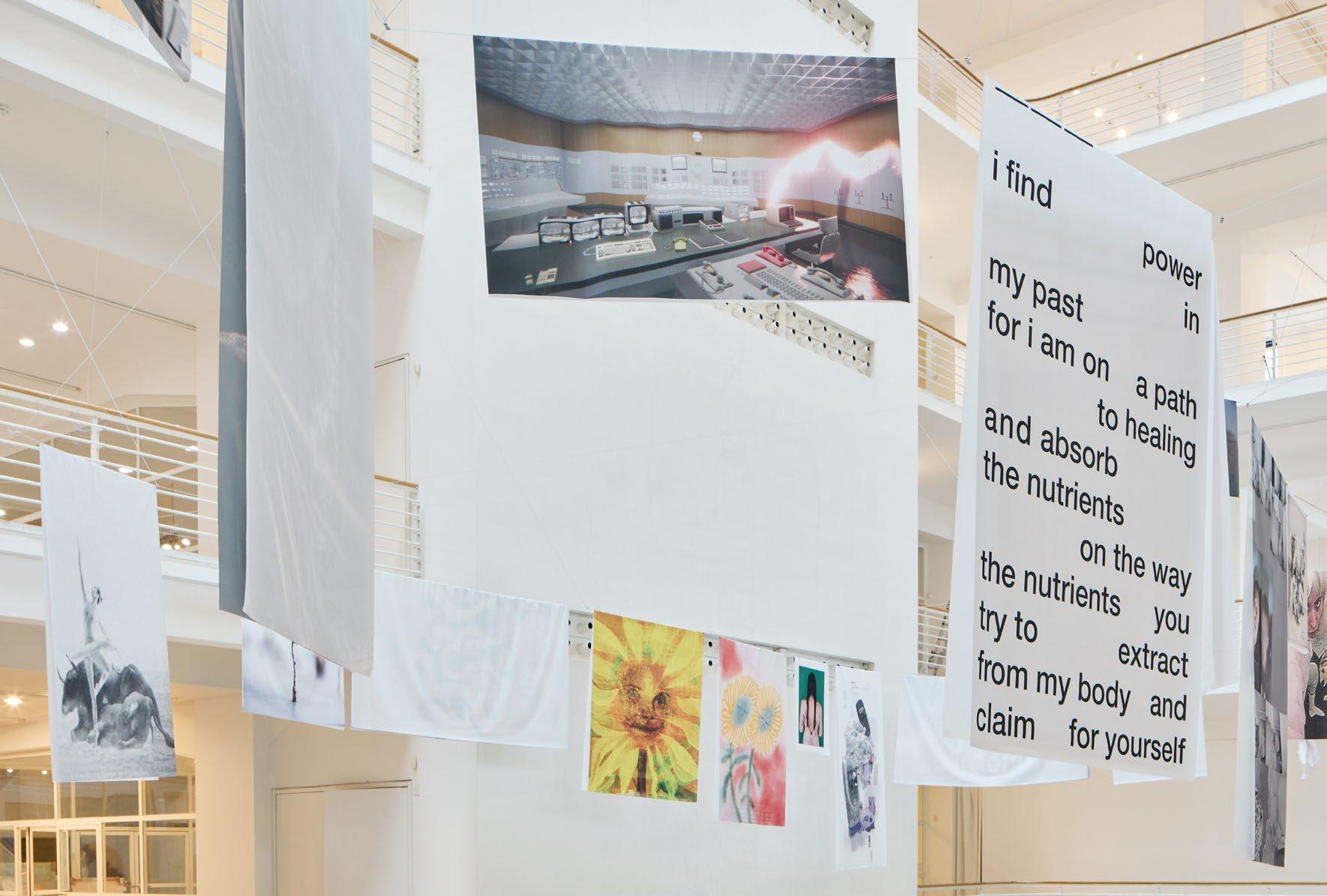

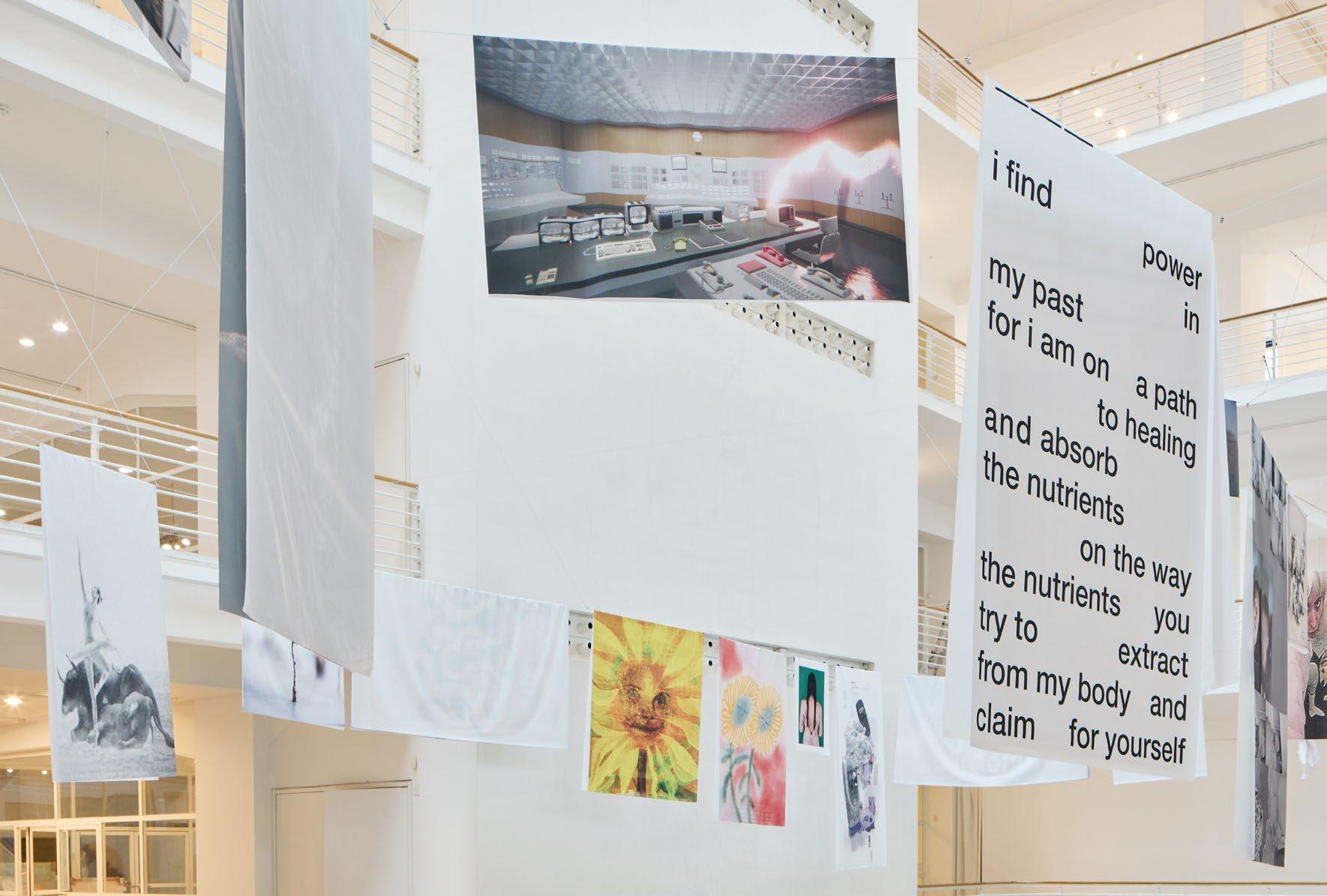

v nás potreba znova uviesť do pohybu to, čo bolo arbitrárne vylúčené: vystaviť aj tých*ie, ktorí*é by mohli vyhrať za iných okolností, pri inom zložení poroty, v inej nálade, za iného počasia. Všetkých 79 prihlásených sme pozvali, aby sa zúčastnili výstavy, ktorá by mala vzniknúť ako rozvetvenie prezentácie laureátov*iek. Spätnou väzbou boli rôzne názory na správnosť či nesprávnosť nášho gesta, rady na zlepšenie a úvahy o súčasnom nastavení ceny. Aj keď sa nám nepodarilo vychytať všetko (napr. vystaviť originálne diela namiesto digitálne vytlačených návrhov alebo tlačiť na recyklované plátno), týmto gestom sme dúfali v demokratickejší a inkluzívny dialóg. Naším zámerom bolo iniciovať vznik organickej štruktúry, v ktorej budú paralelne existovať odlišné výtvarné pozície, a rozšíriť kontext mladej generácie o náznaky rôznorodých obsahov a nálad, ktoré táto generácia prináša. Forma tohto dialógu nám pripomínala priebeh technopárty. Tancujúci (umelci*kyne) sa stávajú jedným telom a sú to práve oni, kto DJ-om (kurátorom/moderátorom) diktujú tempo a gradáciu. Párty sa koná v obrovskej hale (vo Veletržnom paláci), kde sa prepotení tanečníci*čky de facto kúpu vo vlastnom ja, no zároveň je to skúsenosť účasti a jednoty.6 Čiže tancujeme sami so sebou, ponorení do seba, a simultánne sme súčasťou akejsi „mystickej participácie“7. Výstavu tak vnímame ako proces kontinuálnej resingularizácie, v ktorom sa indivíduum stáva na jednej strane viac zjednotené s inými a na druhej strane viac rozdielne, osobité. Jedno posilňuje druhé: rôznorodosť umocňuje kolektívne telo a súčasne prehlbuje individuálnu inakosť.

6 Vladislav Šolc uvádza technopárty ako príklad „mystickej participácie“ a prostredníctvom analytickej psychológie sa tu zaoberá archetypmi prítomnosti. Šolc, Vladislav: Archetyp otec (a jiné hlubinně psychologické studie). Praha: Triton, 2009.

7 Pojem do analytickej psychológie uviedol C. G. Jung. Ide o stav mystického spojenia alebo identity subjektu s objektom.

S radosťou sme zistili, že na našu výzvu zareagovalo 61 oslovených umelcov*kýň a umeleckých skupín, z toho 57 sa rozhodlo do projektu zapojiť: Tomáš Absolon, Markéta Adamcová, Néphéli Barbas, Zuzana Bartošová a Andrea Uváčiková, Radoslav Bigoš, Tomáš Blažek, Radka Bodzewicz, Antonín Brinda, Nela Britaňáková, JaCobra & Baďa Diaby, Michal Čeloud Šembera, Markéta Filipová, Dominik Forman, Matěj Frank, Markéta Garai, Ishmat Muhammad Habib, Filip Hauer, Matěj Hrbek, Barbora Kachlíková, Magdaléna Kašparová, Deana Kolenčíková, Šárka Koudelová, David Krňanský, Jan Matýsek, Milan Mazúr, Lucie Medřická, Jozef Mrva, Barbora Myslikovjanová, Anna Nerušilová, Martin Netočný, Karolína Netolická, Ondrash & Kašpárek, Lukáš Prokop, Lea Petřiková, Tereza Příhodová, Jasmin Schaitl, Lukáš Slavický, Tatiana-Sofiia Sorokina, Dominik Styk, Eva Škrovinová, Sofie Tobiášová, Natália Trejbalová, Andrea Uváčiková & amp, Ondřej Vicena, Adam Vít, David Vojtuš, Václav Voleský, Martina Koblic Walterová, Sara Wollasch, Aleš Zapletal plus päť laureátov*iek. Prezentácia autentických príspevkov všetkých týchto autorov*iek má uvítací tón vo Veletržnom paláci nad Malou dvoranou. Pestré príbehy súčasnosti sa ďalej rozvíjajú v prácach laureátov*tiek v mezaníne. Šľachtenie, hybridizácia, spleť ľudských a neľudských entít, novopohanské kulty, dekolonizácia tela, rodová nebinarita, nové druhy viditeľnosti, reálna a mentálna dimenzia vojny, utečenci, sociálne siete, pomníky jadrovej energetiky, špekulatívne politiky, virtuálne a reálne zlyhania...

Na jednej strane by sme týmto gestom radi využili našu moderátorskú rolu na radikálne amplifikovanie pozornosti a na vyjadrenie pospolitosti, mnohorakosti a súdržnosti v umení aj v spoločnosti. Na strane druhej považujeme za podstatné kriticky precítiť výročné ceny ako CJCH a jej

and the social alongside the individual. However, we were unable to implement this idea due to the tendency of the laureates to focus on their own works, without treading onto common ground. We went through the portfolios of all the artists who applied for the award and began to feel the need to once again set in motion that which was arbitrarily excluded: to exhibit also those who could have won had the circumstances been different, had the jury been different, had there been a different mood or even different weather. We approached each of the seventy-nine applicants for the JCHA 2022 with an invitation to participate in the exhibition, which would be created by branching out from the laureates pre-selected by the jury. While communicating with the artists over email and telephone, we received various questions and thoughts regarding the correctness or incorrectness of our gesture, advice on how to make further improvements, and thoughts about how the award is currently set up. Although we didn’t manage to implement all the ideas (such as exhibiting originals instead of digital prints or printing on recycled canvas), we hoped that this gesture would lead towards a more democratic and inclusive dialogue. Our goal was to initiate the creation of an organic structure in which different artistic perspectives could exist side-by-side. This would expand the context of the young generation with the hints of the diverse contents and moods that they bring in. The strategy we chose was based around materialising an exhibition that would be a sort of rave. The dancers (artists) form a single body, and it is they who dictate the tempo and gradation to the DJs (curators/moderators). The rave takes place inside a huge hall (the Trade Fair Palace), with the dancers drenched in their own sweat, essentially bathing within their own selves, while, at the same time, it is an experience of

participation and unity. 6 So, we dance with ourselves, immersed in ourselves, and simultaneously we are part of a kind of “mystical participation”.7 We thus view the exhibition as a process of continuous resingularisation in which the individual is brought to closer unity with others while also acting as different, distinctive. One reinforces the other: Diversity strengthens the collective body while simultaneously deepening individual difference. We were thrilled to find that sixty-one of the approached artists and art groups responded to our call, fifty-seven of whom decided to join the project: Tomáš Absolon, Markéta Adamcová, Néphéli Barbas, Zuzana Bartošová & Andrea Uváčiková, Radoslav Bigoš, Tomáš Blažek, Radka Bodzewicz, Antonín Brinda, Nela Britaňáková, JaCobra & Baďa Diaby, Michal Čeloud Šembera, Markéta Filipová, Dominik Forman, Matěj Frank, Markéta Garai, Ishmat Muhammad Habib, Filip Hauer, Matěj Hrbek, Barbora Kachlíková, Magdaléna Kašparová, Deana Kolenčíková, Šárka Koudelová, David Krňanský, Jan Matýsek, Milan Mazúr, Lucie Medřická, Jozef Mrva, Barbora Myslikovjanová, Anna Nerušilová, Martin Netočný, Karolína Netolická, Ondrash & Kašpárek, Lukáš Prokop, Lea Petříková, Tereza Příhodová, Jasmin Schaitl, Lukáš Slavický, Tatiana-Sofiia Sorokina, Dominik Styk, Eva Škrovinová, Sofie Tobiášová, Natália Trejbalová, Ondřej Vicena, Adam Vít, David Vojtuš, Václav Voleský, Martina Koblic Walterová, Sara Wollasch, Aleš Zapletal, and the five laureates. The presentation of the

6 Vladislav Šolc lists raves as an example of “mystical participation” and uses analytical psychology to consider the archetypes of presence. Šolc, Vladislav: Archetyp otec (a jiné hlubinně psychologické studie) TRITON, Prague, 2009.

7 The term was introduced to analytical psychology by C. G. Jung. It is a state of mystical unity or merging between the subject and the object.

18

podobné, ktoré sa často míňajú účinkom.8 Kolektív SJCH sa nad problémom oceňovania dlhodobo zamýšľa a aj preto sa rozhodli prikloniť k jednokolovému rozhodovaniu poroty. Nie sme si istí, ako naložiť s takto realizovanou reformou. Nie je to eliminácia súťaže súťažou? Je pre nás znepokojujúce stáť medzi cenou a ne-cenou, medzi inklúziou a exklúziou, medzi opaterou a zanedbávaním. Aj keď si ceníme snahy SJCH o reformy CJCH9, nemôžeme nemyslieť na to, že umelecké ceny predstavujú anachronizmus z uplynulého binárneho veku víťazov a porazených a je otázkou, či majú vôbec zmysel, resp. či nepodporujú korporátne modely konania, propagácie, komunikácie, či neživia

8 V posledných rokoch sa čoraz častejšie objavujú hlasy spochy bňujúce umelecké ceny a ich nastavenie. Finalisti*ky Preis der Nationalgalerie 2017 sa v otvorenom liste vyjadrili k problémom, ktoré majú s ocenením. Vyjadrili obavy týkajúce sa praktík stojacich za touto cenou: príliš sa zameriava na pohlavie a národnosť umelkýň, nie dostatočne na ich umenie; príliš ochotne sa zapája do PR cyklu umeleckého sveta; účasť na finálnej výstave nie je honorovaná. V roku 2017 sa finalisti*ky Ceny Oskára Čepana postavili proti neprofesionalite koordinovania a organizovania ceny a s ňou spojenej výstavy a odmietli súťažiť. Namiesto toho sa rozhodli vystúpiť jednotne, ako kolektív. V rámci Turner Prize 2019 sa finalisti*ky rozhodli rozdeliť cenu a zdroje na rovnaké časti, resp. od poroty požadovali nie individuálne, ale kolektívne ocenenie štvorice. Vytvorili vyhlásenie solidarity (Statement of Solidarity), kde svoje rozhodnutie opreli o roztrieštenosť doby, ktorá by sa nemala multiplikovať ešte aj vo vnútri umeleckého sveta prostredníctvom súťaženia. Symbolický akt mal reflek tovať politickú a spoločenskú poetiku, ktorá je prítomná v ich umeleckej praxi. Kriticky k súpereniu pristúpili aj finalisti*ky CJCH 2020 a cenu prijali kolektívne.

9 Problém oceňovania v umení je podkutý rôznymi teoretickými zdrojmi a SJCH dlhodobo pracuje a rozvíja tento diskurz na teoretickej i praktickej úrovni. V posledných rokoch došlo k viacerým zmenám CJCH, tou zrejme najvýraznejšou je upustenie od jedného víťaza a dvojkolového výberu poroty od roku 2021.

mýty, že súťaživosť je prirodzená ľudská vlastnosť, prípadne že súperením dosahujeme lepšie výsledky alebo že ocenením sa formuje osobnosť a posilňuje sebavedomie jednotlivcov. Nie sú ceny pomôckou pre zberateľov, ktorí sa malým oblúkom zorientujú v tom, čo má aktuálne „cenu“? Nebývajú autorizované ocenenia receptom na horké pocity frustrácie? Nebýva tvorba umeleckých diel v tomto kontexte poháňaná túžbou po statuse a inštitucionálnom uznaní, ktoré formuje spôsob, akým umelci*kyne prezentujú svoje diela a definujú úspech? A opäť, nie je CJCH na druhej strane jednou z mála udalostí na scéne, ktorá nás excituje a strháva našu pozornosť? Nie sú akcie spojené s touto cenou jednými z najvýraznejších v našom regióne? Ako kritizovať umeleckú cenu, ktorá sa svojím 30-ročným fungovaním zaslúžila o vznik veľkého množstva nových diel a o zviditeľnenie českého umenia vo svete?

Zárodkom názvu výstavy je názov knihy Marshalla Bermana All That Is Solid Melts into Air10 z roku 1982. Berman tvrdí, že modernizmus v spojení s toxickými tendenciami priemyselného kapitalizmu a imperializmu spustošil psychický a duchovný život človeka, ako aj jeho sociálne a ekonomické podmienky. To nám pripomenulo dialektiku našej patologicky roztekavej kultúry, ktorá metastázuje do prepálených výkonov, presilenia, preháňania a predbiehania. Podľa Bermana by sme mali nájsť pevný terén, na ktorom sa dá pristáť, a návod na prekonanie „rozpúšťajúcich sa“ účinkov

10 Názov knihy si Berman požičal z Komunistického manifestu Karla Marxa, ktorého priamo cituje v kapitole „Marx, Modernism and Modernization“: „All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and men at last are forced to face with sober senses the real conditions of their lives and their relations with their fellow men.” Berman, Marshall: All That Is Solid Melts into Air. New York: Penguin Books, 1982, s. 89. Na knihu nás upozornil Jan Brož, za čo sme mu veľmi vďační.

authentic contributions of all these authors will have a welcoming tone in the Trade Fair Palace above the Small Hall. The varied stories of today will be further developed in the works of the laureates in the mezzanine. Breeding, hybridization, the tangle of human and non-human entities, neopagan cults, the decolonization of the body, gender non-binarity, new kinds of visibility, the real and mental dimensions of war, refugees, social networks, nuclear monuments, speculative politics, virtual and real failures...

On the one hand, we would like to use this opportunity to radically amplify attention and to express togetherness, multiplicity, and cohesion within art and within society as a whole. On the other, it is high time to critically re-evaluate annual awards, including the JCHA and others like it, which often miss the mark.8 The Jindřich Chalupecký Society has spent a long time thinking about the issue of awards, which is also why it has decided to instead use a single-round jury

8 In an open letter, the finalists of the Preis der Nationalgalerie 2017 spoke about their issues with the award, particularly regarding the practices behind the award itself: that it focuses too much on the gender and nationality of the artists and not enough on their art, that it engages all too willingly in the PR cycle of the art world, and that the award does not have any money associated with it. In 2017, the finalists of the Oskár Čepan Award openly criticised the lack of professionalism in the coordination and organising of the award and the associated exhibition. They refused to compete and instead presented their work jointly, as a collective. As part of the Turner Prize 2019, the four finalists decided to divide the prize and resources equally between themselves and demanded the jury assess them collectively rather than as individuals. They wrote a “Statement of Solidarity”, in which they explained their decision by stating that the fragmentation of our time should not be exacerbated from within the art world by making artists compete against each other. The symbolic act was supposed to reflect the political and social poetics that is found in their artistic practice. The finalists of the JCHA 2020 were also critical of competition, choosing instead to accept the award collectively.

system. However, we are not sure how to grapple with this sort of reform. Isn’t this just eliminating competition with competition? It is worrying for us to be positioned between award and non-award, between inclusion and exclusion, between care and neglect. Although we appreciate the efforts of the JCHS to reform the JCHA,9 art awards represent an anachronism from the bygone binary era of winners and losers, and the question remains whether there is any point to them at all – or, more precisely, whether they don’t just uphold corporate models of behaviour, promotion, and communication or fuel the myths that competition is a natural human trait, that competition leads to better results, or that awards shape the personality and bolster the self-confidence of individuals. Are awards not a shorthand for collectors to understand what is currently “valuable”? Are authorised awards not a recipe for bitterness and animosity? Isn’t the creation of artworks in this context often guided by the desire for status and institutional recognition, shaping the way in which artists present their works and how they define success? Then again, on the other hand, is the JCHA not one of the few events within the scene that titillates us and grabs our attention? Aren’t the events associated with this award some of the most significant in our region? How to criticize an art prize that has contributed to the creation of a large number of new artworks and to the visibility of Czech art in the world through its 30-year activity?

9 The issue of art awards is underpinned by various theoretical sources, and the JCHA has been working in the long term to develop this discourse on both a theoretical and practical level. In recent years, there have been several changes to the JCHA, perhaps the most significant of which was the abandonment of the single winner and the two-round selection by the jury in 2021.

20

nášho sveta v pozornejšom čítaní literatúry a v citlivejšom vnímaní architektúry, urbanizmu a umenia. Podobne sme sa chceli postaviť k tomuto projektu aj my: naznačiť vizuálny návod, ako pomôcť ľuďom zblížiť sa v tejto volatilnej dobe a ako ráznejšie uchopiť náš súčasný stav odcudzenia. Hodnoty, ktoré sa nám ukázali byť bez pevného základu v reálnom svete (kolektívne tvorenie, hlásaná horizontalita, excentrická starostlivosť, politická korektnosť), sú často prázdne, v praxi neexistujúce alebo neefektívne abstrakcie. Dôležité pre nás je predstaviť výstavu ako neurčitý, otvorený vektor, v ktorom sa rôzne skupiny, objekty, jednotlivci a informačné sféry navzájom pretínajú a ovplyvňujú. Z tejto perspektívy sa priestorovo-časová konštelácia CJCH 2022 môže stať miestom vytvárania, navrhovania a opätovnej artikulácie vzťahov medzi tými, ktorí sa na nej zúčastňujú, ale aj tými, ktorí účasť obišli.

disciplíny, ktorú nachádzame v súťažiach, ale aj v inštitúciách, a namiešanie prezentácie z bohatých sezónnych (estetických a tematických) ingrediencií, ktoré vytvoria komplexnú „chuť“ a nový výraz.

The title of the exhibition is a play on the title of Marshall Berman’s book10 All That Is Solid Melts Into Air11 (1982).

All That Is Solid Melts into Air (Všetko pevné sa rozpúšťa vo vzduch) sme jemne pretavili do All That Is Solid Melds in the Air (Všetko pevné sa spája vo vzduchu). Etymologicky vzniklo slovo „meld“ spojením slov „melt“ (roztaviť, rozplynúť, roztopiť) a „weld“ (spojiť, zvárať) a znamená zmiešať, spájať alebo zjednocovať rozpustením. Je to niečo ako rozpúšťanie a zároveň splynutie s iným.11 „Melding in the air“ (spájanie vo vzduchu) nám prišlo vhodné tak na popísanie fyzickej inštalácie, ktorá sa bude vypínať v prázdnote,12 ako aj na naznačenie toho, čo vlastne naše gesto znamená – narušenie delenia a selektívnej

11 Toto slovo sa často používa v kulinárstve – „cook until the flavours meld“

12 V čase písania tohto textu nie je celkom jasné, ako bude inštalácia vyzerať. Riešia sa technické (ne)možnosti spojené s vešaním o zábradlie a povolenia od NG inštaláciu uskutočniť.

In it, Berman argues that modernism, coupled with the toxic tendencies of industrial capitalism and imperialism, has laid waste to humanity’s psychological and spiritual life, along with the social and economic conditions. This reminded us of the dialectic of our pathologically dissolving culture, which now metastasises into overdoing, overpowering, over-exaggerating, and overtaking. According to Berman, we should find solid ground on which we can land and seek guidance for overcoming the “melting” effects of our world in more attentive reading of literature and a more sensitive taking in of architecture, urbanism, and art. In this project, we wanted to take a similar approach: to outline a visual guide that would help people come closer together in this volatile time and give us a better grasp of our current state of alienation. Theories that had not been put into practice proved to us to be without a solid foundation in the real world: collective creation, proclaimed horizontality, political correctness, and eccentric care are but empty abstractions, non-existent or ineffective in practice. It is important for us to present the exhibition as an indefinite, open vector in which different groups, objects, individuals, and information spheres intersect and influence each other. From this perspective, the

space-time constellation of the JCHA 2022 becomes a place of creation, conceptualisation, and the re-articulation of relations between those who are participating as well as those who passed on doing so.

All That Is Solid Melts Into Air has been gently melted into All That Is Solid Melds in the Air. Etymologically, the word “meld” was formed by combining the words “melt” and “weld”. Melding therefore suggests a simultaneous dissolution and merging with the other.12 “Melding in the air” seemed appropriate to describe the physical installation that will extend into the void,13 and it is also an indication of what our gesture actually means: disrupting the compartmentalization and selective discipline we find in competitions and institutions alike as well as a blending of the presentation made from rich, seasonal (aesthetic and thematic) ingredients that will create a complex “flavor” and a new expression.

10 The book and its title were brought to our attention by Jan Brož, for which we are deeply grateful.

11 Berman borrowed the title of the book from Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto which he directly quotes in the chapter “All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: Marx, Modernism and Modernization”: “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and men at last are forced to face with sober senses the real conditions of their lives and their relations with their fellow men.” Berman, Marshall: All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience Of Modernity Penguin Books, New York, 1988, p. 89.

12 This word is often used in cooking – “Cook until the flavours meld.”

13 At the time of writing, it is not entirely clear what the installation will look like. We are still sorting out the technical (im)possibilities associated with hanging things off of railings and getting permission from the National Gallery to carry out the installation.

22

Čo sme docielili týmto projektom:

� neočakávane sme do NG dostali ďalších 52 mladých umelcov*kýň;

� napli sme a zároveň vystreli CJCH;

� prečítali sme si Marshalla Bermana (vďaka, Jan Brož);

� nacvičili sme si spojiť nespojiteľné;

� spoznali sme päť umelcov*kýň, od ktorých sme sa niečo naučili;

� prelúskali sme texty v katalógoch predchádzajúcich ročníkov CJCH (čo by sme inak nikdy neurobili);

� architektúru, ktorú by si mohli vo Veletržáku nechať;

� utužili sme naše kamarátstvo.

Čo sme sa dozvedeli:

� že čierne gauče v Malej dvorane stáli 15 miliónov Kč;

� že slovo „starostlivosť“ má veľa interpretácií;

� že niektorým nevybraným umelcom*kyniam vyhovuje zostať v anonymite;

� že promo k výstave je pre niektorých dôležitejšie než samotná výstava;

� že umelci*kyne, ktorí*é dbajú na udržateľnosť vo svojej tvorbe, ekologické princípy často porušujú (napr. pravidelné lacné lietanie);

� že niektorí čítajú naše gesto ako nešťastný pokus pripomínajúci salón odmietnutých;

� že seno je hmota plná života, ktorý nemá povolený vstup do galérie;

� že skupinové rozhodovanie je zdĺhavé a vedie k priemernosti;

� že kurátorovanie umeleckej ceny sa neoplatí.

V čom sme zlyhali:

� zvládnuť výstavu bez prekročenia rozpočtu;

� obísť sa bez vyhrážok;

� stretnúť sa so všetkými vystavujúcimi umelcami*kyňami;

� nebyť ani, ani a aj, aj;

� vystaviť originálne diela všetkých prihlásených umelkcov*kýň;

� mať na to zverejniť tú najdrzejšiu verziu textu;

� neprepájať rôzne úrovne praxe prostredníctvom zvrchovanej supervízie;

� nájsť dodatočné zdroje na vyšší honorár pre nami pozvaných vystavujúcich*úce;

� vymyslieť ekologickejšie prevedenie výstavy;

�� dodržať harmonogram;

�� prísť s ľahko realizovateľnými, a pritom vtipnými riešeniami;

�� bezkonfliktne dokončiť projekt;

�� nemať veľké rozdiely medzi tým, čo sme si predstavovali, a tým, čo sme dosiahli;

�� vyhnúť sa úplne slovám a postaviť projekt čisto na zážitkoch;

�� viac afirmovať ako kritizovať;

�� povedať o umeleckých cenách niečo nové.

Na čo chceme čo najskôr zabudnúť:

� na stretnutie s hospodárskou správou Veletržného paláca;

� na prihlasovacie heslo k e-mailu kuratoricjch2022@gmail.com.

What we achieved with this project:

� we unexpectedly brought 52 more young artists to the National Gallery

� we stretched and stressed JCHA at the very same time

� we read Marshall Berman (thanks, Jan Brož)

� we rehearsed connecting the unconnectable

� we met five artists and learned new things from them

� we read through the texts in the catalogues to previous editions of the JCHA (which we never would’ve done otherwise)

� a space layout they could keep in the National Gallery

� we strengthened our friendship

What we learned:

� that the black couches in the Small Hall cost 15 million CZK

� that the word “care” has many interpretations

� that some unselected artists prefer to remain anonymous

� that the promotion of the exhibition is more important to some than the exhibition itself

� that artists who care about sustainability in their work often violate ecological principles (e.g. regular lowcost flying)

� that some read our gesture as an unfortunate attempt reminiscent of the Salon des Refusés

� that hay is a mass full of life that is not allowed to enter the gallery

� that group decision-making is tedious and leads to mediocrity

� that curating an art award isn’t worth it

What we failed at:

� putting together the exhibition without going over budget

� meeting all the exhibiting artists

� getting by without threats

� not being both neither, nor and also, also

� exhibiting the original works of all the artists who submitted

� putting out the cheekier version of this text

� not intertwining different levels of practice through absolute supervision

� finding sufficient resources to pay more to the exhibitors we invited

� coming up with a more ecological version of the exhibition

�� sticking to the schedule �� coming up with easy-to-implement yet smart solutions

�� completing the project without conflict �� having only small disparities between what we envisioned and what we achieved �� avoiding words altogether and building this project purely on experience �� affirming more than criticising �� saying something new about art awards

What we want to forget as soon as possible:

� the meeting with the economic management of the Trade Fair Palace

� the login password to kuratoricjch2022@gmail.com.

24

Eva Škrovinová Nezabudni, že nemusíš... Remember, You Don‘t Have To... 2022 Dominik Forman Upálení mistra Jana Husa Execution of Master Jan Hus 2022 Adam Vít Bez názvu Untitled 2022

Dominik Forman Upálení mistra Jana Husa Execution of Master Jan Hus 2022

Eva

Škrovinová Nezabudni, že nemusíš...

Remember, You Don‘t Have To... 2022

Markéta Garai Stále lahodím oku?

I Still Pleasing To The Eye?

2022

Eva Škrovinová

Nezabudni, že nemusíš... Remember, You Don‘t Have To... 2022

Adam Vít Bez názvu Untitled 2022

Jozef Mrva ml. Skromný požadavek A Modest Demand 2022

Am

Karolína Netolická Nemožnost vzlétnout Impossible to Fly 2022 Matěj Frank Visual Distancing (For Leo) 2022 Anna Nerušilová Skolióza Scoliosis 2022 Aleš Zapletal Greta (Slunečnice) Greta (Sunflower) 2021 Sofie Tobiášová Selfie 2022

DominikStyk Bez názvu Untitled 2022 Lucie Medřická Na kraji jiný krajiny At The Border Of Another Landscape Foto: Filip Švácha 2021 Milan Mazúr vimeo.com/723774583 2022 David Přílučík Plemeno Breed 2022 TerezaŠtětinováMaskMaska3 32019 Anna Nerušilová Skolióza Scoliosis 2022 Magdaléna Kašparová mTmR.gif =* 2022 Olga Krykun Pomněnky Forget-Me-Nots Незабудки Niezapominajki 2022

Natália Trejbalová Bez názvu Untitled 2022

Václav Voleský Zápas o pozornost Fight for Attention 2019 Vojtěch Radakulan Období osamělých směn, aneb nejdražší muzeum na světě The Era of Lonely Shifts and The Most Expensive Museum In The World 2022 EzraŠimek DigitalForeheadKiss2022 Anna Nerušilová Skolióza Scoliosis 2022 Magdaléna Kašparová mTmR.gif =* 2022 Olga Krykun Pomněnky Forget-Me-Nots Незабудки Niezapominajki 2022 Aleš Zapletal Greta (Slunečnice) Greta (Sunflower) 2021

Radoslav Bigoš Vše co zbylo z Ikara All That’s Left of Icarus 2022NéphéliBarbas Vitrínas palmou Palm Vitrine 2020 Tomáš Blažek Vizuál1–Čas (Umělcovavýstava2.2) Visual 1 – Time (Artist’s Exhibition2.2) 2022 Martina Drozd SmutnáTeige 20222022 Markéta Filipová Smrt a život tančí Death and Life Dancing 2022 Ishmat Habib Bez názvu Untitled 2022 Jasmin Schaitl Současnost / přítomnost (vzduch) Present / Presence (Air) 2018 JaCobra & Baďa Diaby Hlouběji Deeper 2022

MartinaDrozdSmutnáTeige20222022 Tomáš Blažek Vizuál 1 – Čas (Umělcova výstava 2.2) Visual 1 – Time (Artist’s Exhibition 2.2) 2022 Jasmin Schaitl Současnost / přítomnost (vzduch) Present / Presence (Air) 2018 David Krňanský FAIL 2021/22 Lea Petříková Finally Higher 2022

Lea Petříková Finally Higher 2022

David Krňanský FAIL 2021/22

JaCobra & Baďa Diaby Hlouběji Deeper

2022

Václav Voleský Zápas o pozornost

for Attention

Lucie Medřická

Na kraji jiný krajiny

The Border Of Another Landscape

Švácha

David Krňanský

FAIL2021/22

Fight

2019

At

Foto: Filip

2021

ŠárkaKoudelová Dřevěnýarchiv WoodenArchive 2022

Nela Britaňáková Mystické zatmění Mystical Eclipse 2022

Barbora Myslikovjanová Pieta 2021

SaraWollaschInV pozadíBackround2022

Ishmat Habib Bez názvu Untitled 2022

Filip Hauer

Snění o práci: Pro kolik bude vaše budoucnost?

Dreaming About Work: The Board Game 2022 Šárka Koudelová Dřevěný archiv Wooden Archive 2022

MarkétaFilipová DeathSmrta živottančíandLifeDancing

2022 Ishmat HabibBez Untitlednázvu2022 Tomáš Absolon Blue Pill 2022

Matěj Hrbek Mystické výjevy v krajině/ Multiverse Mystical Landscape Situations/ Multiverse 2022 Antonín Brinda Natírání sněhu Painting Snow Foto: Julius Töyrylä 2019 Michal Čeloud ŠemberaAnachron 22020 David Vojtuš Modul Module 2022 Lukáš Prokop The Murky Space of Opacity Between the Veil and the Seer 2022

Markéta Adamcová Untitled Bez názvu 2022 Deana Kolenčíková Syntax z večerky Syntax from the Bodega 2018OndřejVicena LotteryLost 2022 David Vojtuš Modul Module 2022 LukášSlavickýAtlas2022Tatiana-Sofiia Sorokina Život je krásný / Mapa utrpení It’s a Wonderful Life / Map of Suffering 2022

LukášProkop TheMurkySpaceof VeilOpacityBetweenthe and the

Souboj vlasteneckých, národo veckých i fašistických hnutí na našem území nese znaky, ve kterých bychom dnes mohli spatřovat symptomy korporativismu, č monopolismu. Tuzemský veřejný prostor 19. a první poloviny 20. století byl přesycen orga nizacemi, které se vzájemně předháněly ve snaze etablovat své vlastní pojetí velkého dějinného příběhu. Do roku 1918 vytvářel příkrov monarchie situaci, kterou je možné opsat meta forou vyrovnané soutěže. Po zániku mocenského centra ve Vídni získala monopolní dominanci podoba narativu, na níž je naše státnost vystavěna dodnes. Směrem k zapomnění tím byly postrčeny odlišné interpretace dějin, které se do hledáčku veřejného zájmu dostávaly už jen v momentech, kdy byl mainstreamový příběh ohrožen. Stejně, jako př nastolení ekonomického monopolu nad určitým segmentem trhu i zde platí, že vítěz bere vše. Kultura a politika dominují cího korporátu se stává univerzálním systémem znaků, jemuž rozumí zaměstnanec i spotřebitel. Loga, interní směrnice, podniková hymna, team buildingové akce. To vše, jako by tu s námi bylo odjakživa. Rétorika méně dominantních organizací se nám náhle jeví jako příliš specifická, nebezpečně cizí a narušitelská. Pod jejím povrchem však tiká stejná touha po nastolení monopolu. Co kdybychom neúspěšné a zapomenuté slogany vlastenců převedli do současného firemního newspeaku? Jaký je vztah mezi společenským a ekonomickým fašismem? Co tvoří membránu oddělující národ nostní a korporátní identitu?

** The conflict between nationalist, nativist and fascist movements on our territory has certain features which may nowadays resemble the symptoms of corporatism or monopolism. During the 19th century and the first half of the 20th, Czech public space was oversaturated with organisations trying to promote their own interpretations of the grand historical narrative. Up until 1918, the cover of monarchy created a situation that may be described via the metaphor of a fair tender. Following the collapse of the seat of power in Vienna, one form of the narrative established a monopolistic dominance, serving as the basis of our statehood to this day. This pushed other interpretations of history out of memory, only re-entering public consciousness at points when the mainstream narrative became threatened.

Much like in establishing a monopoly over a certain segment of the market, even here the winner takes all. The culture and politics of the dominant cor poration becomes a universal system of signs, understood by both employee and consumer. Logos, memos, company anthems, teambuilding exercises. All this seems like it’s always been here. The rhetoric of less dominant organisations suddenly starts feeling overly specific, dangerously foreign and disruptive. Below its surface, however, rests the same desire to establish a monopoly. What if we translated the unsuccessful and forgotten slogans of patriots into contemporary corporate newspeak? What is the relationship between social and economic fascism? What forms the membrane separating national and corporate identity?

Martin Netočný Verze vlasti #1 * Versions of Homeland #1 ** 2021–2022 Andrea Uváčiková & Zuzana Bartošová We Are Touching Our Limits 2022 Barbora Kachlíková Při práci na sérii AutoMoto, stodola v Ratulantii 932 Working on the series AutoMoto, barn of Ratulantie 932 2022

Seer2022 *

Ondrash & Kašpárek

Neznámý detail

Martina Koblic Walterová Vtipný polární život. Gratulujeme Lední medvědi! Jako výherci naší soutěže se stanete novou tváří naší zimní kolekce dětských oteplováků značky Shein. Funny Polar Life. Congratulations Polar bears! As the winners of our competition you’ve become the new face of our Shein winter childwear collection.

Unknown Detail 2022

2021

Uroboros

Ouroboros

2022 Barbora Kachlíková Při práci na sérii

AutoMoto, stodola v Ratulantii 932

Working on the series AutoMoto, barn of Ratulantie 932 2022

Radka Bodzewicz

Radka Bodzewicz

Deana Kolenčíková Syntax z večerky Syntax from the Bodega 2018OndřejVicena LotteryLost 2022 David Vojtuš Modul Module 2022 Lukáš Slavický Atlas 2022Tatiana-SofiiaSorokina Životjekrásný/ Mapautrpení It’s a WonderfulLife/ MapofSuffering 2022Jan Matýsek Strážce The Guardian 2022 Martin Netočný Verze vlasti #1 Versions of Homeland #1 2021–2022Andrea Uváčiková & Zuzana Bartošová We Are Touching Our Limits 2022 Lukáš Prokop The Murky Space of Opacity Between the Veil and the Seer 2022

Apolitičnost v umění je privilegiem, který jsem právě ztratila Olga Krykun

A&J Často se kritika soutěžení v umění prolíná s kritikou kapitalizace uměleckého výkonu. Jsou ceny více pomůckou pro sběratele umění, kteří se díky nim snáze zorientují v tom, co má aktuálně „cenu“, nebo pomůckou laureátům, kteří získají symbolický kapitál ve formě uznání a zviditelnění? Nebo jsou ceny důležitým segmentem ekosystému umění, tím že ho saturují širokým spektrem témat a diskusí? Když to zúžíme pouze na CJCH, v čem vidíš její hlavní poslání, co tě inspirovalo přihlásit se?

O Myslím, že pro umělce má cena hlavně funkci zviditelnění mezi uměleckou scénou, a šance se posunout ven z užší bubliny, ve které se pohybuje. To byl i důvod, proč jsem se přihlásila.

A&J Kromě odprezentování vašich děl – laureátek*ů, které*ří jste byli vybráni ještě před naším angažováním se do projektu, jsme výstavu rozšířili směrem ke všem přihlášeným umělkyním*cům. Naším záměrem bylo iniciovat vznik struktury, ve které budou paralelně koexistovat odlišné výtvarné pozice a rozšíří kontext vaší generace, vytvořit komplexní výtvarnou databázi s různorodými obsahy a náladami, které tato generace přináší. Přihlášené umělkyně*ce, které*ří se nedostaly*i mezi laureátky*ty, nevnímáme jako neúspěšné. Oslovením všech chceme vyjádřit naši snahu rozpustit dichotomické dělení úspěšní/neúspěšní – vítězové/poražení. Jak vnímáš tento krok?

O Do ceny CJCH se nehlásím prvním rokem, a podobně jako mnoho dalších umělců jsem posílala open-cally/přihlášky do soutěží, šance dostat se někam je

A&J Often, criticism of competition in art is intertwined with criticism of the capitalisation of artistic performance. Are awards more of a tool for art collectors to get a quick idea of what is currently “valuable” or a tool for the laureates to gain symbolic capital in the form of recognition and exposure? Or are awards an important part of the art ecosystem, saturating it with a wide range of topics and discussions? Narrowing it down to just the Jindřich Chalupecký Award, what do you see as its main mission, and what inspired you to submit your work?

O I think that for artists, the award mainly has the function of exposure within the art scene and serves as a chance for them to move out of the confines of their bubble. That was also the reason why I applied.

Apoliticalness in art is a privilege that I’ve recently lost Olga Krykun

A&J In addition to presenting the works of you, the laureates who were selected even before our involvement in the project, we expanded the exhibition to include all the artist who submitted. Our intention was to initiate the creation of a structure in which different artistic positions co-exist in parallel and expand the context of your generation, to create a complex art database with the diverse contents and moods that this generation brings. We don’t consider the artists who applied but did not make it among the laureates to be unsuccessful. By approaching everyone, we wish to dissolve the dichotomy of the successful/unsuccessful – winners/losers. How do you view this step?

O This was not my first year of applying for the JCHA, and, like many other artists, I submitted my work to a number of open calls/competitions – and the chances of

66

velmi nízká. Nevím, jestli to nějak systematicky řeší problém, ale je to symbolický krok pozitivním směrem.

A&J Již začátkem 20. století tematizovali avantgardisté B. Corradini a E. Settimelli metody oceňování kvality umění. V roce 1914 vydali manifest Weights, Measures and Prices of Artistic Genius, ve kterém cenu uměleckého díla odvodili od jeho společenského přínosu. Podobný požadavek na oceňování a společenský přesah umění se dnes objevuje na různých přehlídkách umění, např. aktuální documenta se výrazně zaměřuje na umělecké skupiny, komunity a společenský přesah umění. Jak vnímáš možnosti umění angažovat se v pandemických, válečných, ekologických časech? Může umění efektivně ovlivňovat realitu i z bezpečí Veletržního paláce?

O Umění vnímám jako jednu z lidských potřeb, kterou naplňují umělci v různých obdobích dějin jiným způsobem. Dneska výtvarné umění může hlubokým způsobem odrážet realitu, možná dokonce i předpovědět budoucí tendence, a to díky citlivé analýze dneška. Bohužel ale teď ve své současné formě neohne z bezpečí Veletržního paláce pandemii, válku a ani ekologickou situaci. To ale neznamená, že umění není silný nástroj. Kultura je jednou z hlavních zbraní lidstva napříč historií.

sociálních nebo politických struktur. Identifikuješ politickou dimenzi ve svých pracích? Musí podle tebe současné umělecké formy formulovat nové vztahy mezi politikou a estetikou, mezi autonomií a politickou angažovaností nebo potřebujeme dnes více spekulativních imaginativních „apolitických“ narativů?

O Apolitičnost v umění je privilegiem, který jsem právě ztratila. Ať už udělám cokoliv, moje umění bude politické.

A&J Říkáš, že apolitičnost v umění je privilegium, které jsi právě ztratila. Máme to chápat tak, že aktuální politické dění tě nutí být politickou „proti srsti“?

O Rozhodně bych neřekla „proti srsti‘“, některé věci si bohužel nejde uvědomit, dokud je nezažijete. S novou zkušeností se lidem přirozeně mění názor na některé věci.

making it anywhere are very low. I’m not sure if this addresses the issue in a systematic way, but it’s a symbolic step in a good direction.

A&J

Already at the beginning of the twentieth century, the avant-garde artists B. Corradini and E. Settimelli spotlighted the methods for evaluating the quality of art. In 1914, they published their manifesto “Weights, Measures, and Prices of Artistic Genius”, in which they derived the value of a work of art from its social contribution. Nowadays, a similar requirement for the evaluation and social relevance of art can be seen at various art shows (e.g., the strong focus of the current documenta on art groups, communities, and the social relevance of art). What do you think about the possibilities for art to be socially and politically engaged in a time of pandemic, war, and ecological crisis? Can art effectively impact reality even from the safety of the Trade Fair Palace?

supporting or explicitly opposing the status quo) to the idea that it is art that shows what is currently going on or sheds light on events or situations in which people find themselves in as a result of social or political structures. Do you see a political dimension in your works? In your opinion, do contemporary art forms need to formulate new relationships between politics and aesthetics, between autonomy and political engagement, or do we nowadays need more speculative and imaginative “apolitical” narratives?

O Apoliticalness in art is a privilege that I’ve recently lost. No matter what I do, my art will be political.

A&J You say that apoliticalness in art is a privilege you’ve recently lost. Are we to understand this in the sense that the current political events are forcing you to be political against your preference?

A&J Je velmi obtížné definovat, co je politické umění. Názory na to, co dělá umění politickým, se mohou pohybovat od představy, že každé umění je politické (tj. buď implicitně podporuje, nebo explicitně oponuje současnému stavu), až po zobrazení toho, co se právě děje nebo poukázání na události nebo situace, ve kterých se lidé ocitli v důsledku

A&J Sochařsko-sociální prostředí, které vytváříš v prostoru galerie, si v jednom z našich přípravných rozhovorů odmítla označovat světem paralelním k tomu válkou zdevastovanému. Chápeme, že chceš poukazovat na svět reálný a tragický. Umění en bloc, přestože do života prosakuje, reflektuje ho, popírá nebo afirmuje však vykazuje známky paralelismu, odehrává se souběžně se životem, v odstupu, v určité autonomii. Kde ve svém díle vidíš ten moment splynutí?

O Je možné, že si jinak představujeme pojem „paralelní svět“. Svět, který vytvářím, je samozřejmě fyzicky v jiné lokaci, a není přímým záznamem toho válečného. Mentálně ale je ve stejné dimenzi. Stejně jako když

O I view art as a human need that artists across different historical periods have fulfilled in different ways. Nowadays, art can be a deep reflection of reality and may even predict future trends, and that’s all thanks to the sensitive analysis of today. Unfortunately, in its current form, it cannot impact the pandemic, the war, or the ecological situation from the safety of the Trade Fair Palace. However, that doesn’t mean that art is not a powerful tool. Throughout history, art has been one of the main weapons of humanity.

O I definitely wouldn’t say “against my preference”, but, unfortunately, you can’t understand certain things until you’ve been through them. People’s opinion of certain things naturally changes with new experiences.

A&J It is very difficult to define political art. Opinions on what makes art political can range from the notion that all art is political (i.e., either implicitly

A&J In one of our preliminary interviews, you refused to refer to the sculptural-social environment that you create within the gallery space as a world that exists in parallel to the one ravaged by war. We understand that you want to shed light on the real and tragic world. En bloc art – although it permeates life, reflects it, and denies or affirms it – shows signs of parallelism, taking place alongside life, at a distance, within a certain autonomy. Where in your work do you see that moment of confluence?

68

koukáme na záznamy války, videa a foto přímých (grafický kontent, devastace, smrt, násilí) a nepřímých (výpovědi přeživších, každodennost v týlu, každodennost uprchlíků) záznamů. Ty nepřímé sice jsou také fyzicky jinde, ale mentálně splývají s těmi prvními. To sledování války nepřímo je vlastně tématem, s kterým pracuji. Svojí prací především chci upozornit západního diváka na reálný svět, a z pozice člověka z Ukrajiny se vyrovnat s jeho prožíváním.

A&J Od doby, kdy digitální technologie začaly hrát v našich životech tak důležitou roli, se náš vztah k realitě výrazně změnil. Nejenže jsme stále závislejší na strojích ve všech oblastech života, současné digitální technologie zároveň dramaticky mění způsoby komunikace a odkazují nás na virtuální uživatelské kanály, skupiny, profily. Tyto způsoby online komunikace stále více vytvářejí paradox fyzické anonymity a virtuální intimity. Jak uvažuješ o dialektickém vztahu digitálního světa, lidského těla a sociálního prostoru ty? O Internet a digitální technologii vnímám jako nástroj. A není to první nástroj, který nás posunul od hmatatelné reality do virtuální, například knihtisk, film atp. Ale samozřejmě podoba nástrojů a technologií, kterou zrovna v daném historickém období lidé využívají, pak formuje i nás jako společnost.

Vnímám fluidnost propojení digitálního světa, lidského těla a sociálního prostoru do jakési naší specifické osobní reality a pracuji s tou svou fluidní realitou v umělecké praxi.

předem navržené choreografie. Jaký prostor jim nabízíš k manifestování jejich subjektivních psychologií a životních situací? Je to model spolupráce režisér-herec, nebo dílo vzniká v participativním, resp. kolaborativním dialogu?

O Pojmenovala bych to jako režírovaně-participativní prostředí. S performerkami vybíráme společně oblečení, které dotvářím malými doplňky, které je jemně odliší od návštěvníků. Pak instrukce k choreografii, které dostávají, jsou minimální, aby určily rámec děje. Bavíme se o tématu, a pak je nechávám volně se pohybovat v prostoru. Řekla bych, že pracuji podobným způsobem, jako jsem pracovala s herci ve svých starších videích.

O Perhaps we have different understandings of what “parallel world” means. Of course, the world I create is physically in a different location and is not a direct record of the war-time world. Mentally, however, it’s in the same dimension. Just like when we look at the records of war –videos and photos of direct (graphic content, devastation, death, violence) and indirect (stories of survivors, everyday life in the rear, the everyday life of a refugee) records. In that case, the indirect ones are also physically elsewhere, but mentally they merge with the direct ones. In fact, the indirect following of the war is a theme I’m working with. Through my work, I mainly want to make the viewer aware of the real world and, from my position as a person from Ukraine, come to terms with the experience of it.

A&J

Ever since digital technologies began to play an important role in our lives, there has been a major shift in our relationship with reality. Not only are we increasingly dependent on machines in all areas of life, but today’s digital technologies are also dramatically changing the ways we communicate, referring us to virtual user channels, groups, and profiles. These modes of online communication increasingly create a paradox of physical anonymity and virtual intimacy. What are your thoughts on the dialectical relationship between the digital world, the human body, and social space?

I see the fluidity of the merging of the digital world, the human body, and social space into a sort of specific personal reality, and my own fluid reality is something I work with in my artistic practice.

A&J There are performers who are set in an environment and who are dressed and walk around and behave in accordance with the choreography you created for them in advance. What sort of space do you offer them for the manifestation of their subjective psychologies and life experiences? Is the model of your collaboration that of director–actor, or is the work created through a participative or collaborative dialogue?

O I would call it a directed participative space. We pick out the clothing together, and I add in small accessories that slightly distinguish them from the visitors. Then, the choreography instructions they receive are minimal, just to establish the outline of the plot. We discuss the topic, and then I let them freely move around in the space. I’d say that I work in a similar way to which I worked with the actors in my older videos.

A&J Performerky, které jsou součástí prostředí, jsou oblečené, pohybují se a chovají se podle tebou

O I view the internet and digital technology as a tool. And it’s not the first tool that has moved us from the tangible reality into a virtual one – for example, there’s also the printing press, film, and so on. Although, of course, the types of tools and technology that humans use within a given historical period also shape us as a society.

70

Olga Krykun

Letní pomněnky

Літні незабудки

Olga Krykun vystavuje sérii maleb stylizovaných vyřezávanými dřevěnými rámy do podoby oken s výhledem, zasazených v prostorové instalaci, kterou na vernisáži oživí doprovodná performance. Přestože její nové malby se námětem v podobě antropo morfizovaných květin zásadně neliší od autorčiny dřívější práce, těžiště významu je výrazně pochmurnější. Dílo odkazuje ke stále probíhající a tragické ruské válce v Ukrajině, jež se Olgy Krykun a mnohých dalších autorek a autorů pocházejících z Ukrajiny a žijících a tvořících v Praze bytostně dotýká. Svou aktuální tvorbu Olga Krykun vnímá jako prostředek, jak upozornit západní diváky a divačky na reálný svět a zároveň jak se vyrovnat s jeho prožíváním. Volí k tomu ženskou perspektivu v širokém slova smyslu, pracuje s intuicí a emocemi i vlastními zkušenostmi. Podobizny ukrajinských žen ve formě figurín v životní velikosti a okřídlené drony na pomezí hračky, zbraně a jiného živočišného druhu zachycují přítomnost v její rozporuplnosti – smutek, strach, beznaděj, ale i odvahu a naději. Práce poukazuje také na moment sledování a prožívání války online, paradoxního spojení fyzické vzdálenosti a zároveň palčivých detailů mediálně zprostředkovaných obrazů probíhajícího konfliktu.

Letní pomněnky, Літні незабудки Modrý triptych, kombinovaná technika na plátně, 203 � 162 cm, 2022 Fialový triptych, kombinovaná technika na plátně, 203 � 162 cm, 2022 Černý triptych, kombinovaná technika na plátně, 259 � 162 cm, 2022

Panenka #1 – #10

Objekty, performance (10 �) 150 � 40 � 20 cm, 2022

Performerky Polina Davydenko, Polina Akini, Sofia Lisman, Margarita Ivy, Iryna Zakharova, Tetiana Kravchuk Fotografie Iryna Drahun

Motýl strážný anděl #1

Objekt, 30 � 30 � 60 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #2

Objekt, 30 � 63 � 40 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #3

Objekt, 30 � 40 � 20 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #4

Objekt, 35 � 30 � 43 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #5

Objekt, 25 � 25 � 20 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #6

Objekt, 21 � 33 � 30 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #7

Objekt, 15 � 20 � 5 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #8

Objekt, 9 � 10 � 11 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #9

Objekt, 14 � 12 � 7 cm, 2022

Motýl strážný anděl #10

Objekt, 20 � 18 � 10 cm, 2022

Olga Krykun

Summer Forget-Me-Nots

Літні незабудки