ATreasu re d Legacy Life CyCL es

From birth to death, Jews mark moments of life’s passage with blessings and rituals. These traditions connect the individual to the community, to generations past and future, and to the Jewish people. Personal and community artifacts enhance the rites and ceremonies that observe life cycle events. These objects tell the story of special moments in Jewish life. They illustrate styles and designs that reflect both the time and place of their creation as well as universal Jewish traditions found across time and diverse cultures.

12320 Nall Avenue

Overland Park, Kansas 66209

913-663-4050

curator@bnaijehudah.org

Monday–Thursday, 9 a.m.–5 p.m.; Friday, 9 a.m.–4 p.m.; Closed Saturday; By Appointment Only Sunday

www.bnaijehudah.org/kleincollection

2

“

A season is set for everything, a time for every experience under heaven...”

Ecclesiastes, 3:1

“S tage S of M an ” Paper token, Germany, 1910.

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

BIRTH

Today, thanks to modern medicine, we experience the excitement and joy of pregnancy and birth in relative safety. However, at one time, the real and imaginary dangers to mother and child included beliefs in demons, the “evil eye,” and spirits. While rabbis frowned upon superstition and “magic,” amulets like these were often used to protect from harm. A woman in childbirth or an infant often had an amulet to invoke God’s protection and to ensure their good health.

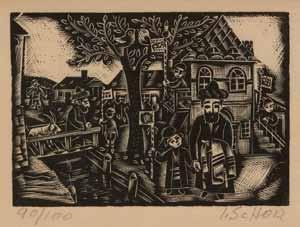

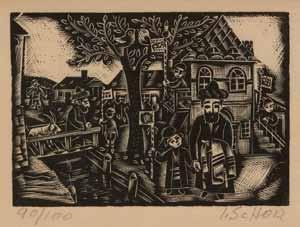

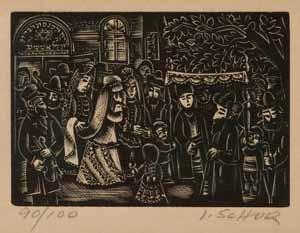

I lya S chor B lock P r I nt

This 4.25-by-3.19-inch print is part of the set used to illustrate Abraham Joshua Heschel’s 1950 book The Earth Is the Lord’s: The Inner World of the Jew in East Europe.

n ecklace w th a M ulet c a S e S

From Iraqi Kurdistan in the 19th century, this necklace (with a 4.75-by3.75-inch plaque) is engraved with the owner’s name: Rivka bat Leah (Rebecca, daughter of Leah). The cylinders hold amulets written on parchment. Many of these amulets for pregnant women and newborns were specifically targeted to protect the child from Lilith, whom Talmudic legend tells us was Adam’s first wife. She was childless and threatened to snatch newborns for herself. The swords that hang on the necklace are intended to deter Lilith.

I tal an a M ulet c a S e

This hollow case holds a written amulet to protect the newborn, but the case itself was also thought to hold power, thanks to special symbols and the Hebrew inscription of one of the names for God, Shaddai (The Almighty). Made of gilt silver in the mid-18th century, the 5.5-inch case would have been suspended over an infant’s crib to protect it from spirits, demons and the “evil eye.”

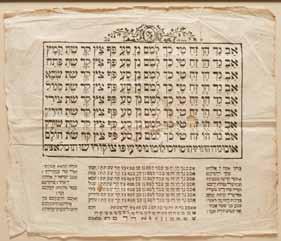

a M ulet

This paper-and-ink amulet was made around 1850 in Persia and inscribed with text from the mystical Jewish Kabbalah to protect the amulet’s owner.

a gate a M ulet

The Hebrew lettering on this 1-inch carnelian stone is in the shape of a menorah (a multi-light Jewish lamp). From Iraq or Palestine in the 19th century, the language expresses hope for a male child whose soul will be like that of the famous Jewish King David’s soul: “white as snow” (free from sin).

B r t M I lah a M ulet

This bronze Eastern European amulet (2.68-inch diameter) celebrates the ritual of brit milah (covenant of circumcision) for a young Jewish boy. The traditional threefold blessing for the child reads, “May this boy grow up enriched by Torah, chuppah (a wedding canopy) and good deeds.” The back side of this 18th or 19th century item, calls to seek God’s blessing from disease and bad magic and it reads:

B

racelet a M ulet

Individual amulets in this silver Persian bracelet (9.5 inches long) from the 18th or 19th century bear inscriptions for protection. Three angels are specifically named to protect babies from the child-snatching demon Lilith.

4 5

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

“Save the children of the people of Israel from the evil eye and from sickness and watch over them. Amen.“

CIRCUMCISION

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

The Jewish rite of brit milah (covenant of circumcision) is considered the physical sign of the bond between God and Abraham and his descendants, the Jewish people. Performed on the eighth day after a boy’s birth and followed by a formal Jewish naming, the circumcision is completed by a mohel, who has received special training for the ritual. The person holding the infant during the ceremony is known as the sandek and is often a grandparent. The importance of this ceremony is apparent in these beautifully decorated objects. The commandment for circumcision comes from the Torah when God says to Abraham, “Such shall be the covenant between Me and you and your offspring to follow which you shall keep: every male among you shall be circumcised. You shall circumcise the flesh of your foreskin, and that shall be a sign of the covenant between Me and you.”

(Genesis 17:10-11)

c I rcu M c ISI on S et

Lined with silk, this 5-inch-long silver box contains a knife for use by a mohel, a flask for styptic powder (to help stop bleeding), a shield, and a small kiddush cup for the infant. The knife handle has a Hebrew blessing. Made in Austria in 1876, the lid depicts the Torah story of the binding of Isaac, as well as some medieval German figures.

S I lver c I rcu M c ISI on f la S k

Scenes related to the brit milah ceremony decorate this 5.25-inch-high German/Bohemian flask used to hold styptic powder. Engraved in Hebrew is Genesis 17:13, which reads in English, “Thus shall My covenant be marked in your flesh as an ever-lasting pact.” The dedication is to “Raphael, son of Kaufman” in 1744.

w ood and S I lver c I rcu M c ISI on f la S k

A 4-inch flask to hold styptic powder shows a carved scene of a mohel a sandek, and an infant on the front. The name Asher Katz appears on the back, dated 1756.

The engraving on this silver kiddush cup (for blessings over wine) shows a picture of the brit milah ceremony and Hebrew that reads, “This cup, bought myself, the humble Zeligman Etting, for good deeds.” The bottom reads, “And not for any retribution, but to honor the Almighty and his Torah.” The 18th century item (2.75 inches in diameter) was crafted by T. Kunitz.

c u S h I on c over

An infant being circumcised would rest on this 21-inch-wide, 18th century covered cushion from Italy. It may also have been placed on a chair as a ritual to call for the eventual return of the prophet Elijah. Traditional Jews hope Elijah will usher in the return of the messiah and help bring peace to the world. The silk fabric was embroidered using flat metallic purl with the Hebrew words “b’siman tov” (“with a good sign,” hoping for good luck in the future).

B r I t M lah c ha I r

This chair dates from 1660s England, just a few years after Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell formally permitted the Jews to return to the country in 1656. Jews had been expelled in 1290, but were once again permitted to return and worship openly, build synagogues, and purchase burial grounds. A large star of David adorns the 43-inch-high chair’s backrest, and pewter-carved, inlaid Hebrew letters reading “brit shalom” (covenant of peace) were added in the 18th-century.

S taff of e l jah

In Afghanistan, Jews believed that because the prophet Elijah attended so many circumcisions, he would get tired running from place to place. Thoughtful hosts provided the unseen-but-welcomed Elijah with a staff to lean on during the ceremony. This 53.5-inch-long item from the 19th century has a silver top that reads in Hebrew, “In honor of Elijah the Prophet, angel of circumcision.”

6 7

h c u P for c I rcu M c ISI on c ere M ony

k I dd IS

late

Abraham, considered the first Jew, is here pictured during the Akedah the story of Abraham’s near-sacrifice of his son Isaac. He is depicted in typical 18th century German garb on the plate from 1790, which was made in Nuremberg, Germany. The 9-inch plate has the brit milah blessing in Hebrew as well as the owner’s initials.

REDEMPTION OF THE FIRSTBORN (Pidyon ha-Ben)

“ w IMP el ” t orah B I nder S

From the 16th to 19th centuries, many Jews in Germany and Central Europe would sew a special binder for the Torah scroll called a wimpel (wrapper) out of an infant’s swaddling cloth. The cloth that had wrapped the child at his circumcision ceremony was cut into four equal strips and sewn together to make one long strip, and was embroidered or painted with the child’s name, the father’s name, the date of birth, and a blessing for the child to grow “to the Torah, to the marriage canopy, and to a life of good deeds.” When the child visited the synagogue for the first time, the wimpel was presented to the congregation. Years later, when the child returned at age 13 to help lead services and read from the Torah as a bar mitzvah (son of the commandment), the Torah scroll was wrapped in the wimpel. This collection includes four 138-inch long Torah binders from Alsace, France, that date from the late 19th century. They are illustrated with traditional folk art as well as a French flag. Historically, wimpels were made only for boys. Modern traditions include wimpels made for girls as well.

In the Torah, Moses and Aaron are sent by God to announce to Pharaoh a total of 10 plagues against the Egyptians to secure the release of the Hebrew slaves. The last of the 10 plagues was death of the firstborn males among Egyptians and livestock alike. The Israelites’ firstborn males, however, were spared. To commemorate the event, the Torah says that all Jewish firstborn males were obligated to lifelong service at the Temple (Exodus 13:2). Those duties were later handed off to the kohanim (priests) of the Levite tribe of Israelites. In today’s Jewish tradition, the ceremony of Pidyon ha-Ben (redemption of the firstborn) has evolved to redeem with money every firstborn Jewish male. The ceremony takes place on the 30th day after the birth of a Jewish boy. Often, the child is brought out by the father on a silver tray. In front of a kohen (a descendant of the ancient priests), the father announces his firstborn son, and the kohen asks the father if he chooses to give his son to priestly service or if he wants to redeem him. The father, upon selecting redemption, pays five silver coins and recites a blessing. The kohen accepts the redemption offering and proclaims, “Your son is redeemed.”

S I lver r ede MP t I on P late

In early 19th century Lemberg, Ukraine, silversmith Dornheim of Lvov designed decorative plates like this one. Later, these plates became the standard for use in the Pidyon ha-Ben ceremony. Zodiac signs, seen here on the 14.5-inch plate’s border, are often found as decorations on Jewish ritual items and in synagogues. The scene of the binding of Isaac is usually associated with the brit milah (circumcision ceremony).

In many places, the silver tray used to carry the child was decorated with the Torah scene of the Akedah, the binding of Isaac by his father, Abraham, before Isaac’s near-sacrifice. Other communities use a smaller plate to hold the coins used in the exchange.

f rench P I dyon ha - B en P late

This pewter plate, made in 1830, was used to hold the coins during a child’s redemption ceremony. Moses’ brother, Aaron, who became the high priest of the Temple, is pictured on the plate along with the Temple’s menorah the Ark of the Covenant, and the Temple’s altar. The 9-inch plate is engraved in Hebrew with the words, “Aaron the High Priest.”

P I dyon ha - B en c o I n S

Minted in France in 1827 from designs by Jacques-Jean

Barre, these bronze coins were designed for use in the Pidyon ha-Ben ceremony. Depicted on the front are Aaron, Moses, and David, and on the back are instruments used in Temple rituals. Hebrew inscriptions relate to each of the three leaders: “I will turn my attention to a theme, set forth my lesson to the music of a lyre.” (for David from Psalms 49:5), “Aaron lifted his hands toward the people and blessed them … ” (Leviticus 9:22) and “Moses, master of all prophets.”

8 9

P ewter P

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

“Just as he has grown to the Covenant, so may he grow to the Torah, to the marriage canopy, and to a life of good deeds.“

CHILDHOOD

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Education is the central focus of a traditional Jewish childhood. Children are surrounded with Jewish symbols, learn Jewish history through family holiday celebrations like the Passover Seder, and watch adult role models enact Jewish values.

The Torah, as well as the wisdom of Proverbs, post-biblical rules and stories from the Talmud all stress the education of children: “...and teach them to your children—reciting them when you stay at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you wake up.” Deuteronomy 11:19

I lya S chor B lock P r I nt

A 4.25-by-3.19-inch print from Heschel’s The Earth Is the Lord’s: The Inner World of the Jew in East Europe.

“For I have singled him [Abraham] out, that he may instruct his children and his posterity to keep the way of Adonai.” Genesis 18:19

Jews have made education a religious obligation and early on created a mandatory universal system of schooling. After children become a bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah (son or daughter of the commandment) and are considered adult members of the community, Judaism calls them to continue Jewish learning throughout their lives.

c

h I ldren ’ S w ood P uzzle S

In the 1970s, Constructive Playthings developed a line of Jewish-themed puzzles created by Michael Klein and manufactured in Israel by “Bumi” Egozi. Educational materials like these toys were sold worldwide.

A

leph B et c hart

Colorful pictures of animals and objects help teach Hebrew (aleph and bet are the first two letters in the Hebrew alphabet) to young children on this 18-by11-inch poster from Warsaw, Poland, from 1880.

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

t all I t k atan

This fringed undergarment (26 inches long) was worn by a male child as a reminder of God’s commandments. The number of strings and knots add up to 613, the number of commandments that rabbis have traditionally found in Torah. This early 20th century tallit is of unknown origin, but most likely comes from Eastern Europe.

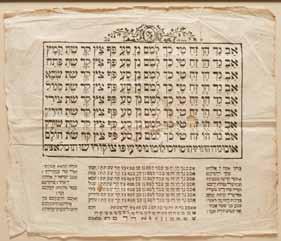

h e B rew A leph B et P r IM er

Basic morning prayers for the very young are combined with an aleph bet primer in this mid-19th century woodblock poster that was most likely printed in Germany. At the top of this 14.5-by-17-inch piece is a ewer (a special vase for holding water) as well as the Hebrew name “Moshe P. SH,” who may have been the printer. The ewer may represent the printer’s status as a Levite, descended from the tribe that, in Jewish tradition, assisted with priestly duties in the days of the Temple in Jerusalem.

“P ar S ha ”

In 1903, when Alphonse Levy published his print collection of rural Jewish life in Alsace, France, that way of life from his childhood had already vanished. In this nostalgic 17.5-by-16.5-inch lithograph, a child learns a Torah parsha (reading portion) from a loving teacher.

IMA g ES OF CHILDREN IN THE COLLECTION

h ungar I an t wo - h andled w a S h I ng c u P

Synagogue life is pictured in beautiful detail on this two-handled, silver handwashing cup. Before modern Sunday School curriculum, Jewish children were regularly present during services and learned rituals and liturgy there. This 6-inch 19th century cup is dedicated for synagogue use.

“ g rand M a ’ S S tory ”

Saul Raskin depicts Jewish children enthralled as an old lady weaves her tales. This mid-20th century work of pencil drawing (11-by-14-inch) depicts children of the era.

l I onel r e ISS w atercolor

Painted in the late 1940s, this image depicts young pioneers in Israel on a kibbutz (a collective farming community) boarding a truck. The water tower in the background identifies the location as Kibbutz Gineigar, not far from Nazareth. The 20-by-14-inch painting reflect moments in the life of the new and vigorous young nation.

10 11

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

NAI MITZVAH

The Torah makes no mention of Judaism’s most important coming-ofage ceremony. The biblical text ascribes no particular importance to the ages of Jewish adulthood today: 13 for boys becoming a bar mitzvah (son of the commandment) or 12 for girls becoming a bat mitzvah (daughter of the commandment). The Torah records 20 as the age of adulthood. There is reason to think the ceremony existed before 500 CE, but the ceremony didn’t begin to assume its current form until the 13th or 14th century. That’s when the custom started of calling boys (and later girls) to the front of a congregation to help lead services and to read from the Torah. More importantly, these b’nai mitzvah (children of the commandment) assume responsibility at the same time for the observance of Jewish precepts and commandments. Whether they participate in a special ceremony or not, Jewish boys and girls automatically become full-fledged members of the Jewish community once they reach these requisite ages.

A 4.25-by-3.19-inch print from Heschel’s The Earth Is the Lord’s: The Inner World of the Jew in East

Engraved sides on these 2.5-inch-wide pieces (c. 1870, Russia) illustrate the animals in a well-known saying from the Jewish Pirke Avot (Ethics of Our Fathers):

This late-19th century handmade Persian bar mitzvah jacket is made from a cloth printed with a wood block design and the Hebrew words, “God bless you and protect you.” (Numbers 6:24), which is one of three parts of the priestly benediction.

ddu S h c u P

A traditional gift to the bar mitzvah is a kiddush cup, which is used for ceremonial blessings of wine. This 3.5-inch-tall silver cup from the English Georgian period (c. 1789) has a family crest and the inscription, “Presented to Isaac Levy to remember his bar mitzvah.” Moses Isaac Levy was president of the Board of Deputies of the British Jews from 1789 to 1801 and died in 1808. The dedication was probably to a son or grandson.

Lions decorate these two silver cases (roughly 2 inches wide) used to store tefillin leather boxes containing Hebrew texts, that are worn by Jewish adults on the forehead and arm at certain times for prayer. The crowned cartouche with the Hebrew letter shin stands for Shaddai, an alternate name for God. These cases, made in Poland in the mid-19th century, held the tefillin used by a boy for the first time after becoming a bar mitzvah

t all I t S

In Scotland, tartan designs for specific clans are registered with a national agency. The contemporary design on this set of tallit (prayer shawl) and yarmulke/kippah (Hebrew and Yiddish words for head covering) are in an officially registered Jewish plaid design. Each color is symbolically Jewish, and the items are made from 100% wool, rendering it kosher, as wool and linen cannot be mixed in clothing according to Jewish law.

Silver lattice work from Morocco decorates this 10-inch-wide bag from the early 19th century used to carry a tallit and tefillin Under the silver, the bag is made with red velvet. The Hebrew reads, “Servant to God, Avraham, Son of Pinchas. God will receive him and strengthen him.”

Made in Morocco around 1900 from purple velvet and metallic threads, the embroidered priestly hands on this 10-inch bag identify the owner (initials “M.C.”) as a kohen descended from a priestly tribe that, according to Torah, handled duties at the Temple in Jerusalem.

12 13 B

’

et

t all I t / t ef ll I n B ag S

I lya S chor B lock P r I nt

Europe

B ar M I tzvah S I lver k I

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

B ar M I tzvah j acket

t ef I ll n c a S e S

“Be strong as a leopard, light as an eagle, fleet as a deer and strong as a lion.“

MARRIA g E

Arguably no other Jewish lifecycle event is more enriched with ornaments and accessories than the marriage ceremony. Beyond the chuppah (marriage canopy), ketubah (marriage contract), and the recitation of the Sheva Berachot (Seven Blessings), different communities have also developed their own unique variety of traditions to celebrate a new couple and send them off to their life together in style.

w edd I ng g elt c ollector

Lacking a flat bottom on which to rest, this 18th century container was probably walked through the crowd of wedding guests to collect money for a newly-married couple. Beautifully made of wood and leather, the 16-inch piece from Germany shows a pair of clasping male and female hands, as a symbol of marriage, as well as the words “mazel tov” in mother of pearl.

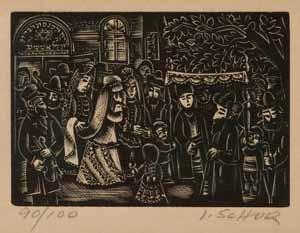

This gouache painting by ilya Schor depicts the bride and groom under the chuppah (wedding canopy) in a romanticized vision of an old Jewish shtetl (neighborhood). The chuppah symbolizes the Jewish home and is open on four sides, reminding us of the patriarch abraham’s tent that was always open for hospitality. The chuppah covering represents the presence of god over the covenant of marriage, a reminder that the ceremony and institution of marriage share a divine origin. The 8-by-12inch painting was created in new York in the 1950s.

S I lver w edd I ng B elt

w edd I ng r I ng

Outsized rings were historically used only during the marriage ceremony and were returned afterwards to the communal synagogue or the family. The castle on this ring (1.6 inches high) is engraved with the words “mazel tov” (good luck). The castle may symbolize the original Jerusalem Temple or perhaps the strong household to be established by the marriage. This gold ring was made in Germany, circa 1700.

A quote from Jeremiah 33:11 on a tray created by L. Roth in the United States in 1995 expresses the happiness of the married couple: “The voice of joy and the voice of gladness, the voice of the bride and the voice of the bridegroom.” The two kiddush cups, for ceremonial blessings over wine, stand 14.5 inches tall.

It was tradition among wealthy German Jews to give a silver belt to both the bride and the groom. These sivlonot (wedding gift) belts were worn under the chuppah and sometimes fastened together. This 32.75-inch-long belt was crafted by Jost Leshhorn around 1725 in Frankfurt.

g er M an w edd I ng B eaker S

Crafted of silver in 1780 in Nuremberg, Germany, these interlocking wedding beakers (3.5 inches high) are engraved with the Hebrew words, “happy bride and groom” as well as the Hebrew letters mem and tav as an acronym for mazel tov (good luck).

S I lver w edd I ng c u PS

Semi-precious stones and art deco figures decorate this pair of early 20th century, 4.5-inch-tall Italian wedding cups. The cups interlock at the rim, symbolizing the joining of two people in marriage.

t urk IS h B r I de ’ S B uckle

Holding together a bride’s dress, these silver buckles with stars of David added to the beauty of the wedding ceremony. These 2.25-inch buckles date from the late 19th century.

a fghan B r dal h ead d re SS

The colored stones on this 7-inch-wide silver bridal head dress, the enamel decorations, and the Hebrew phrase “mazel tov” all added beauty to a late-19th century wedding in Afghanistan.

14 15

“ u nder the c hu PP ah ”

I lya S chor B lock P r nt

A 4.25-by-3.19-inch print from Heschel’s The Earth Is the Lord’s: The Inner World of the Jew in East Europe.

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

“ w edd I ng I n t own ”

Saul Raskin’s nostalgic watercolor depicts a wedding in the Jewish shtetl with the whole village celebrating. The musicians are playing klezmer, a musical style developed by Jews in Central and Eastern Europe. Painted in the United States in 1963, the picture measures 28 inches wide.

P ewter w edd I ng P late

This 12.5-inch-diameter pewter plate from 1780s Prague was given as a wedding gift. The inscription reads, “Presented with congratulations from Dr Mochbor Ravehnni to Reb Mosche Cohen Jemikoy.” In the center are the Hebrew letters mem and tav to stand for mazel tov

c era

MI c w edd I ng d IS h

With a bride-and-groom scene inspired by 19th century wimpel illustrations, this dish was designed to be a wedding gift. American ceramic artist Irma Starr used 16th century English slipware style for this piece made in the late 20th century. Inscribed on the 15-inch-diameter dish is the Hebrew phrase “mazel tov.”

g roo M ’ S t all I t B ag

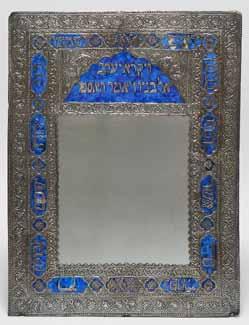

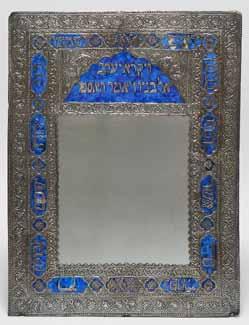

B r de ’ S M I rror

One traditional gift to a Persian bride was a mirror. This 20th century example (21 inches high) has a silver and blue enamel frame as well as the names of the 12 Jewish tribes and a Hebrew inscription reading (Genesis 49:1):

In some communities, such as in the Netherlands, it was customary to give the groom a tallit (prayer shawl). This 10-inch silk bag probably held such a gift, as it’s inscribed, “The pleasant groom Shockmin.” Such a tallit could have been used as a chuppah (wedding canopy); other times, it might have been wrapped around the bride and groom during the ceremony.

S a BB ath o I l l a MP

The family crests of two Jewish Italian families appear near the top of this oil lamp, so this was most likely a wedding gift to be used for lighting on Friday night to mark the beginning of the Sabbath/Shabbat. Made circa 1700, this 32.5-inch-tall brass lamp has six lion-shaped oil receptacles. The crests are of the Sulam and Delmonte families.

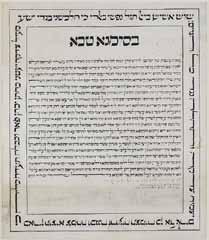

shows a wedding canopy, another a wedding dinner. The top of the 12.5-inch box includes a customary wedding wish, “B’siman tov B

fish and a hamsa (a symbol to ward off bad luck) are for good luck and prosperity. The Ben Porat Yosef prayer in Hebrew (Genesis 49:22) on the top reads, “A fruitful son is Joseph, a fruitful son by spring.”

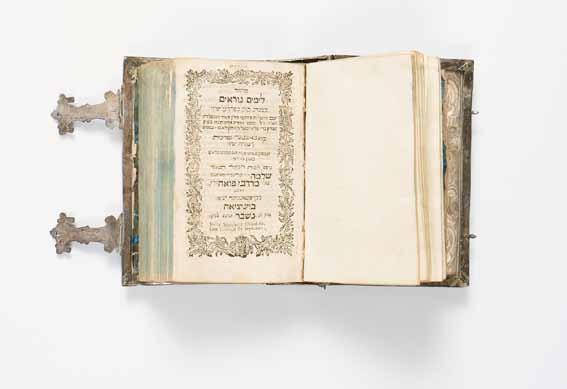

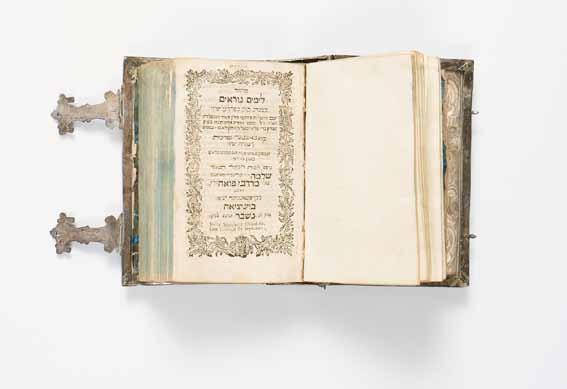

r I de ’ S P rayer B ook

In Jewish Italian tradition, new brides received a prayer book. From Venice, circa 1700, this handwrought 7.5-inch-high silver book binding features scroll motifs. The front and back covers have center cartouches with the bride and groom family crests: the Franchetti family of Livorno, Italy, featuring lions and crowns, and the DeRossi family of Mantua and Ferra, Italy, featuring an upright lion and palm.

16 17

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa B r I de S B oxe S

“And Jacob called his sons and said, come together...“

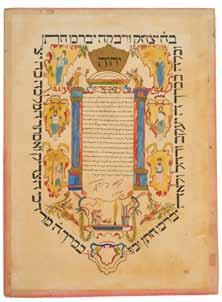

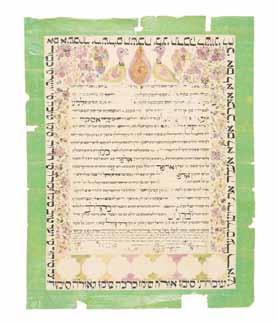

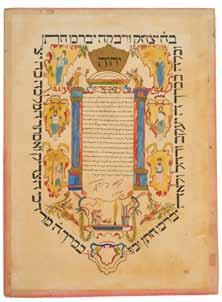

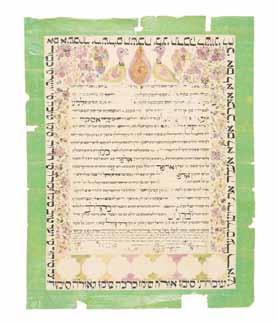

K ETUBAH

Obligations of a Jewish husband to his wife are outlined in a formal marriage document called a ketubah . This tradition dating back thousands of years was started to protect the wife by obligating the husband to financial support in case of divorce. Marriage contracts by Sephardic (of Spanish ancestry) Jews added other stipulations: For instance, a groom could take no other wives, a practice common in Muslim areas, nor could he divorce his wife without her consent.

The custom of decorating ketubot seems to have started in the late Middle Ages in Spain and carried to other European cultures after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. Especially in Italy from the 17th century onward, illuminated ketubot reflect local culture and traditions in their design and form.

DIVORCE

An all-leather shoe with straps is used in a chalitzah ceremony, where a childless widow formally declines to marry her deceased husband’s brother as required in a Levirate marriage (Deuteronomy 25:5-6). Rarely seen today, the ceremony involves the widow making the declaration and removing the shoe from the brother’s foot. This 11-inch-long shoe comes from Europe, circa 1900.

18 19

Kurdistan, early 20th century. 32 inches by 22.5 inches.

Gibraltar, circa 1800. 24 inches by 17 inches.

India, 1830. 20 inches by 13 inches.

Modena, Italy, 1852. 12.5 inches by 11 inches.

Persia, circa 1850. 22 inches by 17 inches.

Turkey, circa 1855. 36 inches by 23 inches. Italy, 1870. 27 inches by 20 inches.

c hal I tzah S hoe

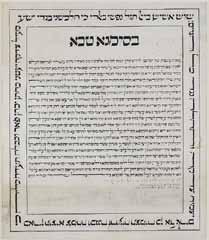

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa k etu B ah aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

DEATH

Jewish customs and rituals surrounding death simultaneously honor the deceased while also allowing mourners to take comfort in the tasks. Most Jewish communities have a Chevra Kadisha (Aramaic for “sacred society”), a society of volunteers who prepare bodies for burial. These societies historically also assumed responsibility for collecting and distributing funds for the poor.

The volunteers work without any expectation of payment. The acts of washing and preparing the body as well as overseeing the burial are important mitzvot (good deeds and commandments). It is considered a great honor to be a member of a Chevra Kadisha, and members would often celebrate at annual banquets.

Honoring the dead also entails observing the yahrzeit (anniversary of a person’s death), usually by lighting a flame in their memory. In addition, synagogue ritual objects are often donated and dedicated to the memory of the deceased.

c hevra k ad IS ha P I tcher

Depicting burial society members along with deer and foliage, this 16-inch-tall, late-19th century ceramic pitcher from Bohemia would hold water for washing the body of the deceased.

M

c o MB

This silver comb from 1741 was used for preparing a body for burial. From Palzich on the border of Germany and Poland, it measures 4 inches long.

P ewter M ug

Used by a Chevra Kadisha at banquets and celebrations, this pewter mug from Hanover, Germany, bears the Hebrew inscription, “Adonai, what is man that you should care about him, mortal man, that you should think of him?” (Psalms 144:3) Made in 1811, it stands 10.5 inches tall.

c ere M on I al w I ne e wer

Used by the Chevra Kadisha at banquets, this 16.25-inch-tall pewter ewer from Germany was made in 1851. The Hebrew inscription has the Kaddish prayer for the dead and identifies the ewer as a “sacred donation as loyal evidence to the burial society of the holy community of Lomza.”

For use in a synagogue, this hanging, 40-inch Moroccan lamp has a hand-wrought silver frame and a chain holding a glass bowl for oil. The dedicatory inscription reads, “In memory of Rav Samuel Haley. 1884.”

l I nen t orah B nder

Crochet work enhances this 4.5-inchwide 1675 Italian binder for a Torah scroll. The Hebrew dedication reads, “The widow of the Honorable Rav Abraham Lunit, his memory should be blessed, gifted from one heart in honor of the Torah of the Holy One, the Perfect One. My handiwork and offering to the glory of God.”

P ewter c har I ty B ox

The realistically sculpted hand has a slot for coins, and the Hebrew inscription reads, “This belongs to the Benevolent Society and the Burial Society of the Holy Congregation of Kolyn” and “Charity shall avert death.” Made from pewter in the 19th century, it stands 8.25” tall.

S efer z I karon (M e M ory B ook )

This hand-lettered book from Hungary contains rules of governance for the Chevra Kadisha, prayers and a page dedicated to each deceased person. Starting in 1858 and continuing until 1938, the names in this 16-inchtall book include members of the prominent rabbinic Softer family.

20 21

ortuary

M e M or I al l a MP

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

Beautiful silver work typical of early-20th century Morocco was used in the creation of this wall lamp. The arched 10.5-inch backplate design memorializes “Esther Malka T.” The unusual double-font lamp would be lit to mark her yahrzeit

This 4.5-inch-tall, silver oil-burning lamp from Hungary (circa 1900) would be lit on the anniversary of a loved one’s death.

Rachel’s Tomb in Bethlehem is the model for this 5.5-inch-tall oil-burning lamp circa 1920-1949. The finial on top of the dome can be removed to place a wick, while the dome is designed to hold oil.

Murals located in B’nai Jehudah’s “Community Commons” illustrate the 150 year history of the congregation. Several of the mural scenes show examples of how the congregation has aided those in need. Outreach to newly arrived immigrants from Eastern Europe at the start of the 20th century included a soup kitchen, job training, a bath house, and education opportunities, while the Mitzvah Garden is a volunteer-run, community-wide project that provides crops for distribution to food pantries and other aid organizations.

The murals painted by California artist F. Scott Hess show how Jewish values have been the bedrock of the congregation, and how those values have influenced the activities of the congregation and its members.

y ahrze I t w all P laque

This memorial print featuring Rachel’s Tomb was printed in the early 20th century by Kohn & Co. of Cologne, Germany. It was completed with an inked inscription for Berta Katzenstein, who died in 1921. Dates in the lower half indicate the standard Gregorian calendar date corresponding with the Hebrew calendar date of the annual yahrzeit through the year 1959.

22 23

y ahrze I t l a MPS aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

IMAGE BY HENDERSON ENGINEERS

“ u nder the c hu PP ah ” painting by ilya Schor. aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa