The Miami Hurricane

By Jenny Jacoby Editor-in-Chief

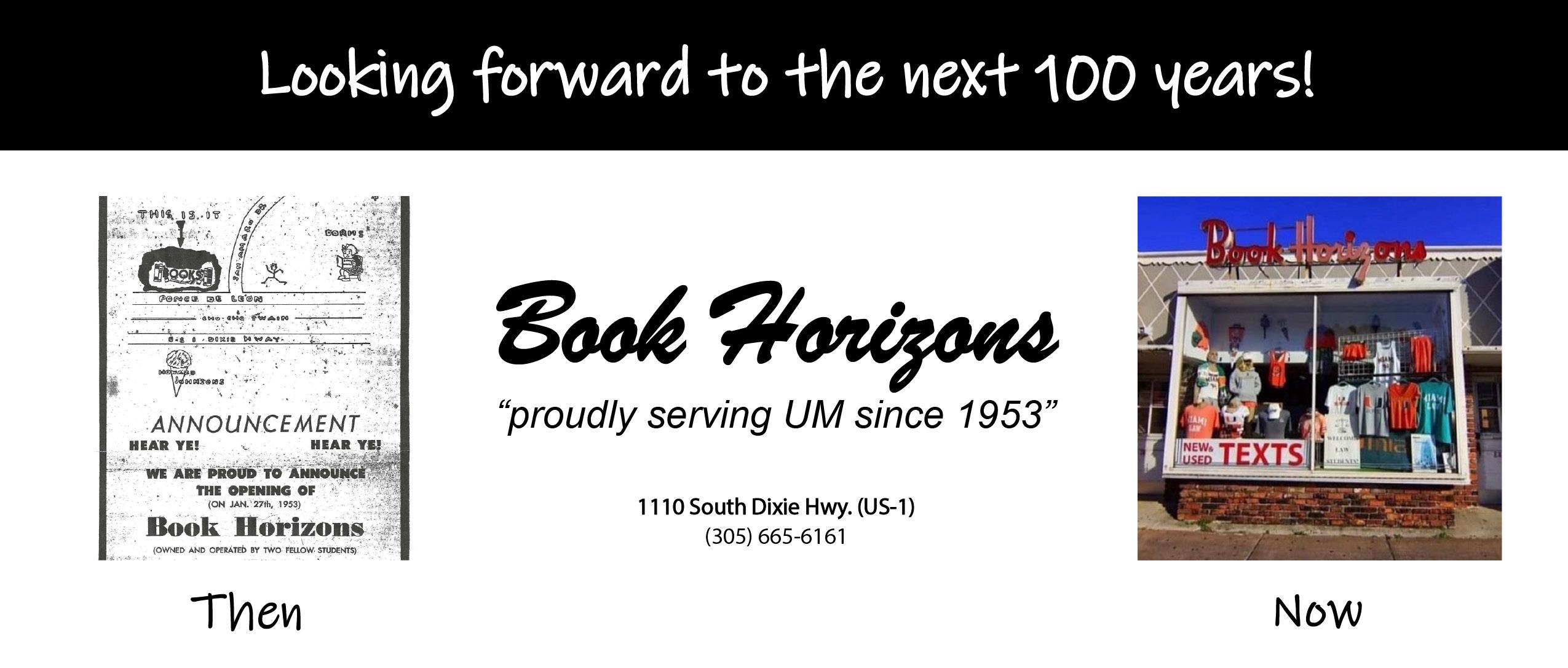

It all started with a 160 acre plot of land, a $10 million donation and a dream.

“Miami should and can have a university, and the ideal place for it is at Coral Gables,” George E. Merrick announced in an advertisement on December 18, 1921.

Merrick’s ambitious optimism was generational. He was born to two-college educated parents that took a risk moving to the young City of Miami. When they arrived, his mother, passionate about supporting her children’s education, opened a school on their property and enrolled ten students.

It’s no wonder then that when Merrick set out to establish a city, he wanted a university to define it.

Within three weeks of UM being awarded its

By Lauren Ferrer Managing Editor

By Keira Faddis Staff Writer

charter, the city of Coral Gables was incorporated, setting the stage for the next century of educational pioneers.

At the time Merrick declared his desire for a university, there were only 42,000 residents in all of Dade County, now known as Miami-Dade.

As of fall 2024, 40,500 people call UM home. More than half are faculty, the rest are a mixture of undergraduate and graduate students.

On April 8, 2025 UM celebrates the day its charter was granted. A celebration that against all odds, the University of Miami was able to persevere, climbing so high as to have once been one of the top 40 universities in the country, according to the U.S. News and World Report.

“One thing is clear: From the beginning this institution has attracted the uncommon confidence and support of visionary people,” Edward Foote wrote in his 1987 Annual Report.

For all intents and purposes UM should have

failed before it even began.

Less than a month out from the first day of class and already behind construction schedule, 150 mile per hour winds ripped through Coconut Grove into Coral Gables.

What followed was worse. Florida’s land boom had evaporated and the Great Depression was underway. There could not have been a worse time to get a university on its feet.

Faculty worked without guarantee of a salary and students endured “cardboard” accommodations in incomplete buildings. Had it not been for the innovation of Bowman Foster Ashe, the first president of the university, UM would not have survived its funding deficit.

According to environmentalist Marjory Stoneman Douglas, supporters of Ashe’s vision were so committed that they were “willing to gamble their lives” to help lay the foundation for a school with the potential to become great.

“Proud as I am of what has been accomplished for Miami in Coral Gables, I am prouder of this University beginning than of everything else put together,” Merrick said.

“For years, I have hoped and worked for this day, and even though we are just starting in this work, I am sure it is in the hearts of all Miami that this good start is to have year after year such a bigger and broader culmination as can be limited only by our dreams.”

Under fireworks, on Lake Osceola’s steps overlooking the campus, UM will ring in its 100th birthday, a commemoration of more than 200,000 graduates, some of the best moments in sports history, groundbreaking research and medical innovations and the dedication that has defined what it means to be a ’Cane. Merrick — a legacy of innovation and education — we can confidently say that there has been no limit to your dream.

By Editorial Board

By Sports Staff

Frost School alumni concert, hosted by TV host and alum Jason Kennedy. What Fireworks Show When 8:30 p.m. Where Lake Osceola

By Keira Faddis Staff Writer

For some people, the decision to attend UM is about more than getting a degree. Legacy students get the unique opportunity to learn in the exact spaces their loved ones did decades ago.

When Hannah Kuker, a senior finance, legal studies and studio art major, sat in one of her sophomore year finance classes, her professor, Seth Levine, was hit with a strong case of deja vu. It did not take long for Levine to realize he taught Kuker’s

By Avery Simon Contributing Writer

When students pass by the Frost School of Music, visit the Lowe Art Museum or hear about accolades at the Miller School of Medicine, they’re walking through the legacy of three families whose names have become synonymous with the University of Miami.

Behind these buildings are stories of generosity that have defined the U and shaped its commitment to music, art and medicine.

The music school was one of the two schools that opened with the University of Miami in 1926. However, it was not until 2003 that Phillip and Patricia Frost donated $33 million to the School of Music. This was the largest gift ever given at the time to a university-affiliated music school across the country.

“We have always felt that music is one of the elements in the culture of our society that moves people to do great things, and it’s one of the arts which has always deserved a lot more support than it has received,” Frost said in a statement to the Sun Sentinel in 2021.

The Frost family also established the Abraham Frost Endowment, which funds the commissioning of new works every two years, further strengthening the school’s dedication to the creation, performance and recording of original music.

In 1951, Joe and Emily Lowe underwrote the funding for the creation of the art museum at the University of Miami. Their donation of $100 million led to the official opening of the Lowe Art Gallery on Feb. 4, 1952. The Lowe family also helped acquire collections of non-Western Art, including pieces from Asia, Ancient America and Africa.

The building? site? was renamed the Lowe Art Museum in 1968 and became the first museum in Miami-Dade County to receive professional accreditation from the American Alliance of Museums in 1972. The museum was recognized by the State of Florida as a major cultural institution in 1985 and has continued to expand throughout the years as a beautiful place for the university community to come and visit.

One of the most generous donors to the University of Miami is the Miller family. Over the years, the Miller family has donated over $221 million to the school. As the Miller family’s primary goal was to enrich the medical program, the name is now recognized alongside the accomplishments of the medical school.

The school was renamed to the Miller School of Medicine in recognition of the 100 million dollars that the family of Leonard M. Miller donated to the school in 2004. Miller, former president and CEO of Lennar Corporation, made the donation with the intention of supporting innovative medical research, improving patient care and training future generations of physicians.

“Our family couldn’t be prouder of our commitment to the university,’’ Stuart Miller said in a written statement to the Miami Herald in 2015. This massive donation supported innovative research in fields including cancer, diabetes and neurology. It also allowed for expanded staff and student assistance and overall improvements in the school’s facilities.

The Miller family also supports the medical school with initiatives and scholarships that help the school strengthen its reputation for being one of the top institutions for medicine.

“We felt our gift was a significant way to continue the advancement of the UM Medical School enterprise that is such an important segment of our community and to honor president Shalala’s many contributions to the university and our community,” Miller said.

mother almost 30 years before in a course to help her become a certified public accountant.

“He recognized me before I said anything about it, as he remembered my parents dating,” Kuker said. “He knew them both and put two and two together via my appearance and last name.”

Her parents, Galite Kuker, class of ‘93, and Seth Kuker, class of ‘92, met and started dating while they were at UM pursuing undergraduate degrees.

“Galite was my Spanish tutor,” Seth said. “We were friends first, but I asked her to be my Spanish tutor. That’s how we became better friends.”

When Galite realized Seth was struggling in his class, she knew she could step in to help him.

“I was really good with foreign languages, and Seth was struggling,” Galite said.

Just as Seth and Galite met on campus, Seth’s parents, Howard and Diane, also started dating after meeting in the 1960s while pursuing their undergraduate degrees at UM. Both are double ’Canes who graduated from UM Law School in 1971 and 1975, respectively.

Russ, Seth’s brother, is also a double ’Cane, who received both his undergraduate and medical degrees at UM.

30 years later, Hannah is not the only Kuker currently studying at UM. Her younger brother, Joshua, and her younger sister, Leah, are in their sophomore year.

“We’re very traditional as a family, so it’s not that we expected all three of the kids to end up there for undergraduate, but it actually keeps in line with the tradition in us,” Galite explained.

While the Kuker story is not one you hear every day, it is something that other legacies, like the Karlinsky family, can relate to.

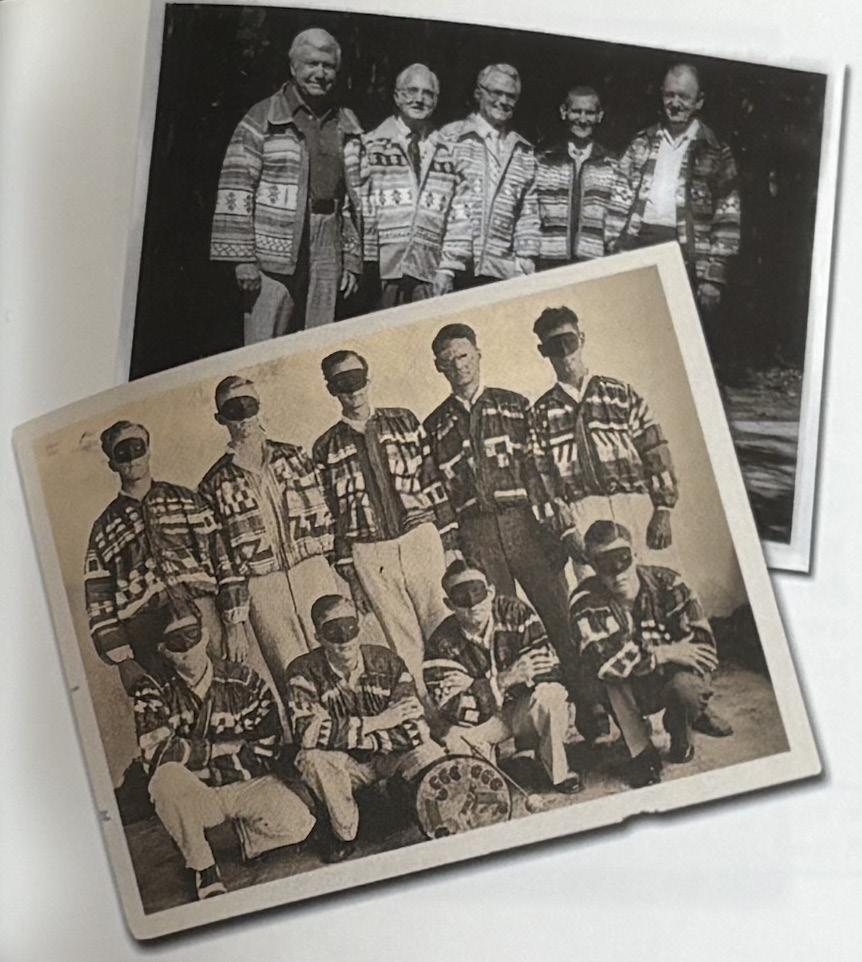

When Neal Karlinsky had to choose a college, picking UM felt like a no-brainer. His father Lee Karlinsky, uncle Fred Karlinsky, and grandfather Richard Furman, all UM alumni, were people he always looked up to.

“Going to UM was a dream because of how much I admire these three men and how UM helped launch their success,” Neal said. “I feel so lucky to be able to pave my own way, while getting to walk in my dad, uncle and grandpa’s footsteps at the U.”

His dad, class of ‘92, and uncle, class of ‘89, were both resident assistants during their time as ’Canes. Fred and Lee also led Alcohol Awareness

Week as Budweiser “Bud College Beer Reps.”

Neal and his younger brother Liam had been invested in the UM community for as long as they can remember. Growing up, they attended Mini ’Canes Camp, a sports camp the University offers every year.

Liam joined Neal as a ’Cane this spring, with the brothers sharing the UM campus for the first time since they attended camp as kids. Seeing his sons continue in the same path he and his older brother chose has felt special for Lee, the boys’ father.

“Having both my children attend University of Miami has been a gift for our whole family,” Lee said. “My older brother and I attended the University of Miami when we were younger and it was an amazing experience. We were both in the same fraternity, Sigma Phi Epsilon, and now my kids are both in the same fraternity, Alpha Sigma Phi.”

Seth and Galite Kuker also expressed the great warmth and pride they feel when they think about their continuing family legacy. Every time they come to visit their kids, they are filled with memories from the days they walked the same paths together more than three decades ago.

“I’d say [UM is] completely different because it kind of is, but in the same breath, it’s the same, but it’s really incredible to watch it grow.”

“The school has come a long way since my parents went there, even from when my wife and I were there to now,” Seth said. “I’d say it’s completely different because it kind of is, but in the same breath, it’s the same, but it’s really incredible to watch it grow.”

The heart of the U: Dr. Patricia A. Whitely’s 43 years of presence

By Lauren Ferrer Managing Editor

While four presidents have led the University of Miami, one steady presence has remained behind the scenes through every transition: Dr. Patricia A. Whitely.

Since arriving at UM in 1982, Whitely has become one of the University’s longest-serving and most beloved leaders. Now the senior vice president for student affairs and alumni engagement, she is in her 43rd year of service.

“She changed my life,” said Associate Vice President for Student Affairs Richard Soboram, who first met Whitely as a freshman in 1987. “I came here with a thick Jamaican accent and no expectations. She saw something in me. Invested in me. Pushed me. And it changed everything.”

Those who know her will tell you that she built her legacy by showing up.

“She’s present, she’s responsive, she’s everywhere,” Dr. Renee Callan, assistant vice president for student life, said. “You’ll be at an event and suddenly realize, ‘Of course, Dr. Whitely’s here.’ She makes the time.”

In 2017, the Faculty Senate recognized Whitely’s legacy with the James W. McLamore Outstanding Service and Leadership Award, which recogniz

graduate experience at St. John’s University, and someone told me ‘You could do this for a living.’”

In those early years, she helped convert Stanford, Eaton, Mahoney and Pearson into the University’s first residential colleges. By the time she became vice president for student affairs in 1997, she had weathered Hurricane Andrew, served as director of student life and earned her doctorate from UM.

Since then, her influence has been felt in every corner of the University.

“She is the most foundational leader we have,” Callan said. “When I think of the University of Miami, aside from Sebastian, the next face I think of is Dr. Whitely.”

She’s helped shape the most visible and personal spaces on campus, including the Wellness Center, Lakeside Village and Centennial Village. From founding the Student Affairs Crisis Coordinator Program to quietly covering hotel costs for students in crisis, her impact is not just institutional. It’s deeply human.

“She’s not just part of the University. In many ways, she is the University.”

Erin Kobetz

Senior Associate Dean for Health Disparities

“She used to personally go to the hospital every time a student was admitted,” Soboram said. “That was her standard. And if a student didn’t have housing, she’d put them in a hotel — even if it hurt the budget. She once used her own credit card to help a student get home in an emergency. Before there was an emergency fund with her name on it, she was the emergency fund.”

It’s a sentiment echoed again and again by those she’s mentored.

“What you see is what you get,” Soboram said. “There’s no pretense. She genuinely cares. And, she expects us to care, too.”

That expectation has created a ripple effect of student-centered leadership across higher education professionals at UM. Dr. Whitely’s mentees have even gone on to lead student life divisions at universities across the country. Brandon Gross, a former UM Student Government president, now serves as an Assistant Vice President at Wayne State University.

“She changed my life,” Gross said. “I didn’t even know I wanted to work in higher ed. She helped me find that path. She gave me tough advice when I needed it, like when she told me, ‘Sometimes you have to move out to move up.’ I didn’t want to leave UM, but she was right.”

Still, she never sought recognition. For example, the Patricia A. Whitely Emergency Fund and the Unsung Hero Award that both bear her name were never her idea.

“The University community named those,” Gross said. “That speaks volumes.”

According to those she crosses paths with, what Whitely has built with purpose is a culture of presence.

“I hold most of my meetings at Starbucks now,” Whitely said. “During COVID, I realized students felt more comfortable outside my office. So I meet them where they are.”

Part of that experience now includes “Pancakes with Pat,” a tradition Whitely started in 2017. No agenda. No speeches. Just pancakes and presence.

“It’s simple,” she said. “But it matters.” So does senior reflections, the four-week seminar she personally leads each spring for graduating seniors.

“I participated in a capstone course like it when I was an undergrad,” Whitely said. “I never forgot how meaningful that was. I wanted to bring that same experience to our students.”

If the McLamore Award honored her official role, these moments speak to something less visible but just as important: the way she holds this place together.

“She’s not just part of the university,” Kobetz said. “In many ways, she is the university.”

Putting the student experience first Whitely has also been a steady presence through some of UM’s hardest moments. During the COVID-19 pandemic, she co-led the University’s response alongside Kobetz, coordinating with then-President Julio Frenk and UHealth to safely reopen in fall 2020.

“I came back to the office after just two weeks of working from home,” Whitely said. “I sat here, alone, for five months. We had 2,700 students who left belongings behind. We shipped boxes to all 50 states.”

She also oversaw the transformation of parts of Eaton into isolation housing. When students asked for hotel-style amenities, she made runs to Target herself, buying bedding and toiletries.

“Small changes like that mattered,” Whitely said. “It wasn’t just about reopening, it was about reopening well.” That sense of care has defined every chapter of her career. She’s shown it in disaster management during Hurricane Andrew, in overseeing the university’s response to tragedies and in fielding late-night calls from students and parents.

“She informs the president, the provost, the trustees. She delivers the news. She makes the calls. And she shows up,” Callan said. “Not everyone does, but she always does.” Even now, as she helps lead UM’s Centennial celebration, Whitely is thinking about students first.

“We chose alumni to speak at commencement this year,” Whitely said. “Because if you don’t showcase your own, who will?”

In the past 43 years, Whitely has worked under four university presidents—Edward Foote, Donna Shalala, Julio Frenk, and Joe Echevarria—and each one expanded her role. As of 2023, Whitely oversees Alumni Engagement, making her a bridge between generations of ’Canes.

“She remembers everyone,” said Callan. “Names, years, majors. It’s uncanny.”

But ask Whitely what she hopes her legacy will be, and she pauses.

“Student engagement. Student experience. The power of presence,” Whitely said. “These roles are temporary, but I hope that culture of care continues long after I’m gone.”

By Casey Servatius Contributing Writer

Women at the University of Miami have not always been at the forefront of leadership. Their progress is the result of decades of advocacy, dedication and efforts, which has set a foundation for generations of women to come.

UM was founded as a coeducational university in 1925, and 646 men and women made up the first fully registered class. Regardless, it took years for women in faculty to feel recognized at the university.

Dr. June Dreyer, PhD, a professor of political science, began working at UM in 1979.

“I was only the second female full-time professor,” Dreyer said. “The other, named Margaret Mustard, was I believe in the Biology Department and had been at UM since the days of ‘Cardboard College.’”

According to Dreyer, it was difficult for women to be taken seriously in a strong academic environment, despite their impressive backgrounds and accomplishments. Before coming to UM, Dreyer was a Far East specialist for the Library of Congress and an Asia policy advisor to the chief of naval operations.

“I had a difficult time even being addressed as Doctor or Professor Dreyer,” she said. “Since my husband also taught here, I had to remind people that I had a doctorate, too.”

Many aspects of student life, like residential colleges and honor societies, were separated by gender at UM until the 1970s and 1980s. Mahoney Residential College was exclusively for men until it was connected to Pearson Residential College in the early 1970s when the two residence halls transitioned to coed living.

The Iron Arrow Honor Society, the highest honor attained at UM, only admitted men until 1985. Prior to this change, Nu Kappa Tau was the highest honor society for women.

Over the course of the University’s century of history, women have made their presence known in other male-dominated academic and athletic pursuits.

Maria Teresa Giammattei, Margarita C. Giammattei and Sherman Hoffman Kilkelly were the first women to graduate from the College of Engineering only five years after it was established in 1947. Today, the College of Engineering is made up of 37% female students, according to UM News, whereas nationally, only 22% of undergraduate engineering degrees are earned by women.

In 1973, UM became the first major university nationwide to offer athletic scholarships to female athletes.

Golfer Terry Williams received a $2,400 athletic tuition waiver just nine months after former President Nixon signed the Education Amendments Act. This included Title IX, which enforces gender equality in high school and college educational programs, as well as athletics. Before Williams, women only participated in recreational sports.

As of fall 2024, UM has 230 male athletes and 250 female athletes.

“The coaches don’t take any incidents lightly when it comes to sexual assault,” Eloise Stuart, a freshman cross country and track and field athlete, said. “Female athletes here feel really supported if they need to come forward about something.”

Kelsey Greer, a first-year student on the cheer team, conveyed the importance of leaning on her fellow female teammates for support.

“We all cheer each other on,” Greer said. “A win for one of us is a win for all of us.”

In 2020, UM announced a Flagship Initiative for women and gender equity. The project examines the current leadership positions held by women and develops ways for UM to further support female students and faculty.

Shortly after, UM established the Public Voices Fellowship in 2021. This fellowship year allowed 20 women and minority members to focus on conducting research and gaining recognition in their respective fields.

Most recently, the Steven B. Schonfeld Foundation established a scholarship for female students studying STEM at the University of Miami. In 2024, the scholarship was offered to four sophomores, and the foundation will continue to sponsor female computer science students for the next eight years.

Still, instances of inequality have been reported, particularly when it comes to faculty pay. According to the Miami New Times, within the school of medicine’s clinical division, male faculty are being paid 25% more than their female counterparts. Additionally, as stated by Forbes, other cases of gender-based pay discrimination are ongoing at UM, such as female professors making $8,500 less per year than male professors with a lower rank.

By Emil Salgado Vazquez Staff Writer

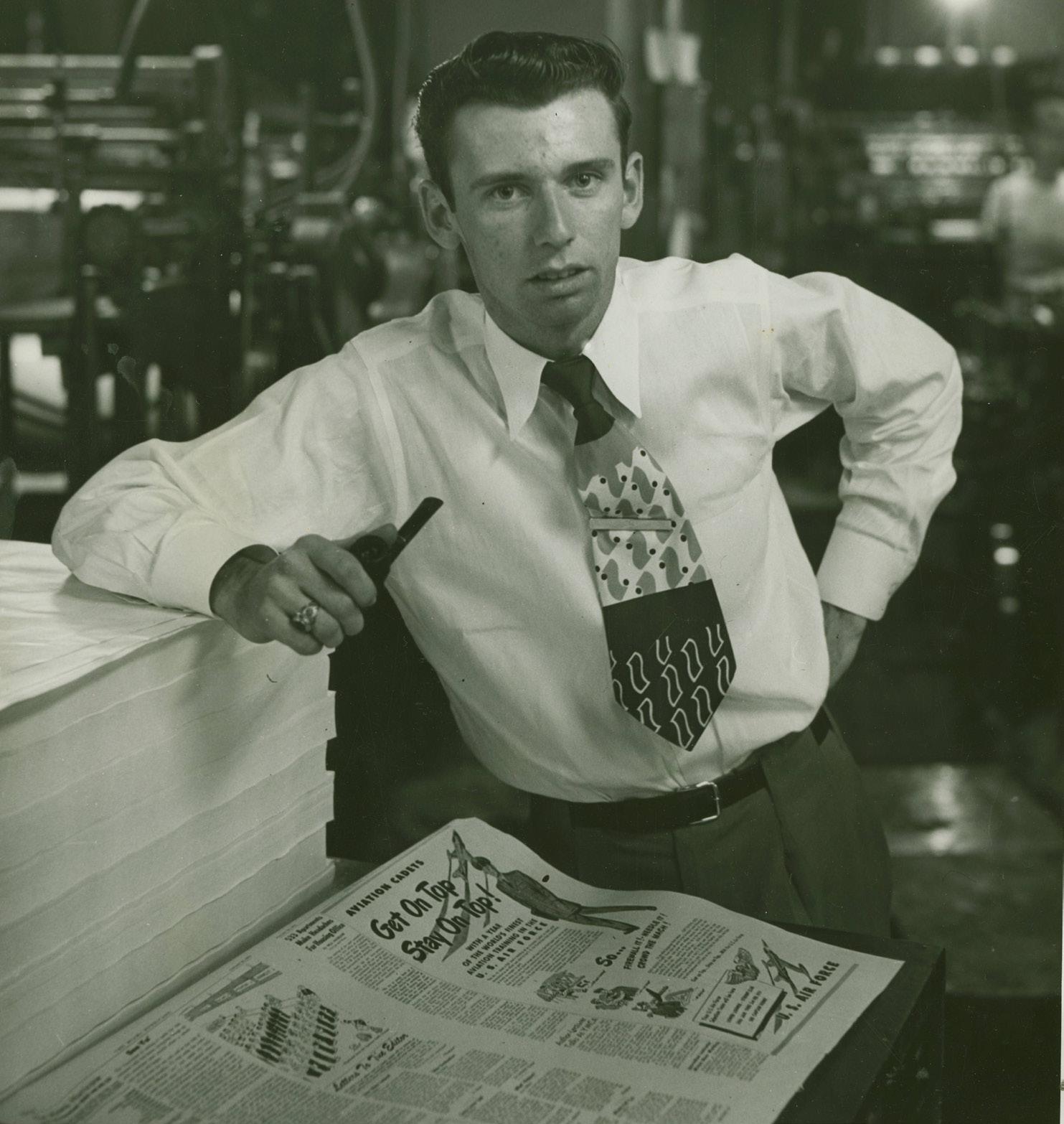

At the front of the classroom, Dr. Mitchell Shapiro takes his stand, ready to deliver yet another lecture at the University of Miami Communication School. Today, he may be teaching about the ethics of journalism; tomorrow, it could be a presentation on the history of mass media mixed in with fun facts about The Beatles.

Thousands of students have heard these lessons during Shapiro’s 43-year career at UM. As one of the longest-serving professors at the university, Shapiro has served under four UM presidents and played an instrumental role in establishing the School of Communication and developing it into what it is today.

“The school has grown leaps and bounds,” Shapiro said. “Our programs are recognized by other professors and deans around the country as some of the best, and that really works for the students who come here, which is what it’s about at the end of the day.”

From student to associate dean

Shapiro’s history with UM goes back further than his time as a professor. He was a ’Cane himself, studying at UM over 50 years ago when the communications department was a collection of programs within the College of Arts and Sciences.

He earned a Bachelor of Arts from UM, a Master of Science, and a Ph.D. from Florida State University. Shapiro started teaching at FSU and Illinois State University before returning to the University as a professor in 1982.

“The people running the College of Arts and Sciences brought me back here to run the broadcast and broadcast journalism programs,” Shapiro said. “One of the reasons they brought me back here was they wanted to become a school of communication within the CAS.”

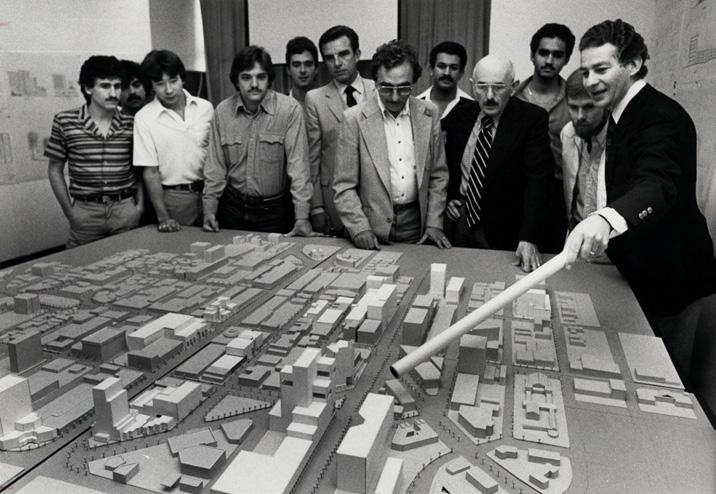

However, the School of Communication would not be housed within CAS for much longer. Under the recommendation of Board of Trustees member

David Kraslow, the SOC became a separate entity.

Shapiro remembers facing opposition from the CAS, who would lose revenue from around 400 Communication majors pursuing degrees at the time.

“The CAS required that all our students had to take a second major in Arts and Sciences,” Shapiro said. “They didn’t really think that what we did was legitimate academics.”

Shapiro quickly became fond of the school’s first dean, Dr. Edward Pfister.

“He was the type of person I would describe as the ideal human to be a dean,” Shapiro said.

They would go on to establish a Doctor of Philosophy in Communication program together.

“When we finally presented it to the Faculty Senate, we were praised for having the best proposal they had ever seen,” Shapiro said. “They had immense faith in us that this would be a top program.”

Pfister’s arrival ushered in the creation of graduate programs, changes to departments and the focus on students getting a liberal arts education.

“All along this time, we were growing,” Shapiro said. “Not just in size, but in reputation. The SoC had gained a lot of respect among the faculty of UM, too.”

Over the course of his career, Shapiro has served many roles. He became the director of graduate studies in 1991, then transitioned to being the SoC’s academic associate dean until 2006 and currently is the director of honors.

don’t have to teach,’” he said. “I would say, ‘That’s what’s keeping me sane.’ When I went into the classroom, all my problems disappeared.”

Shapiro decided to step down as associate dean to focus on teaching full-time.

“Teaching keeps me young and inspired,” he said about teaching. “I was seriously considering retiring two years ago because of the pandemic and online learning. The last two years made it fun for me again.”

The SOC has given Shapiro an environment to educate unlike any other, occupied by exceptional faculty and students.

“It’s allowed me to live out my passion.” He said. “To learn and teach about the media. Just talking with students in my office keeps me young and helps me be a better professor.”

Many of Shapiro’s former students have kept in touch with him over the years, creating a Shapiro-network made up of the students who connect through him, reflecting the impact that Shapiro has had on so many people.

“Dr. Shapiro holds a special place in my heart because he cares about every single one of his students,” Chiara Ambrosini, one of Shapiro’s Honors students, said. “He goes out of his way to ensure our success and is a great professor along the way.”

Shapiro has even had the opportunity to teach the children of his former students, making the net-

“My students are like family to me,” Shapiro said. “A student last semester mentioned to me that her mother was also my student. I keep a list of who I’ve taught and try to encourage them all to Those bonds created speak more than just Shapiro’s impact; it reflects his passion for teaching and hopes for the SOC’s future. “I’d love to see the SoC continue to thrive, and to grow in stature,” he said. “I don’t want to see us ever rest on laurels. I like teaching; I don’t look forward to classes ending. The day I stop loving to teach I will probably retire.”

By Jenna Simone Staff Writer

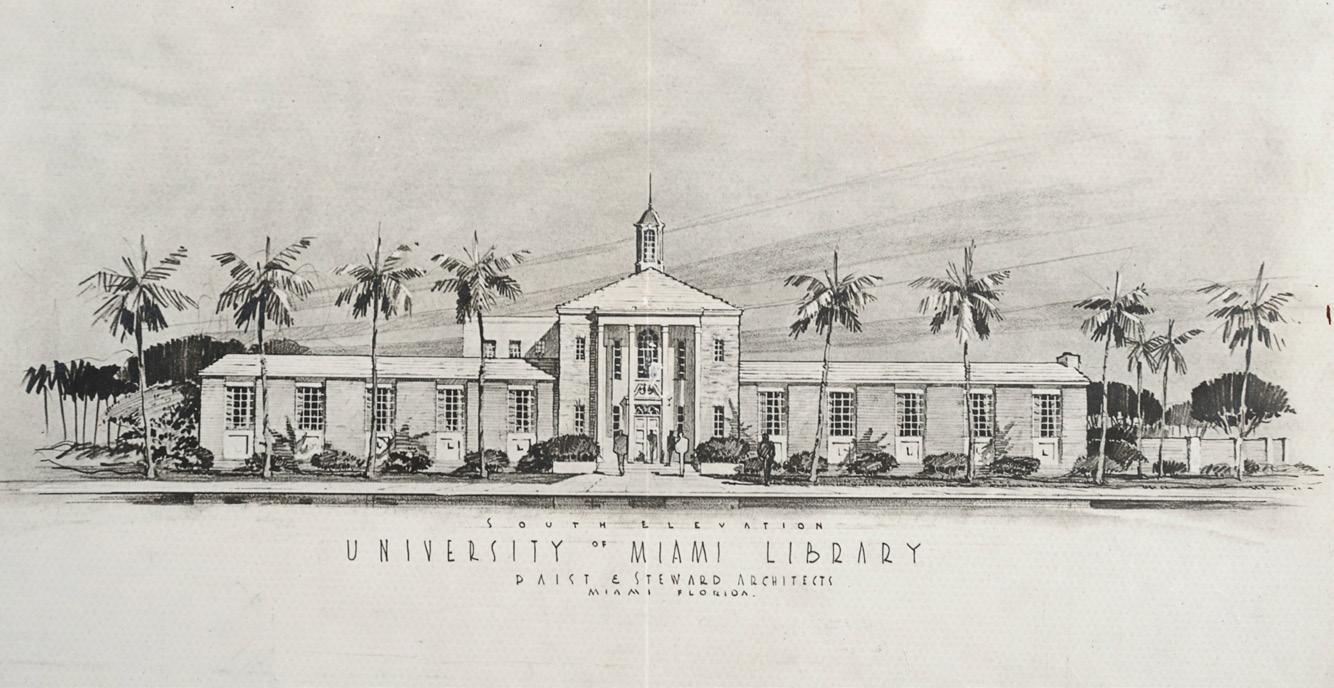

From a small collection of buildings in Coral Gables to a thriving hub of academics, culture and student life, each UM landmark tells a story of progress and tradition.

In total UM is encompassed by 213 buildings and more than 12,600,000 acres of property across its campuses.

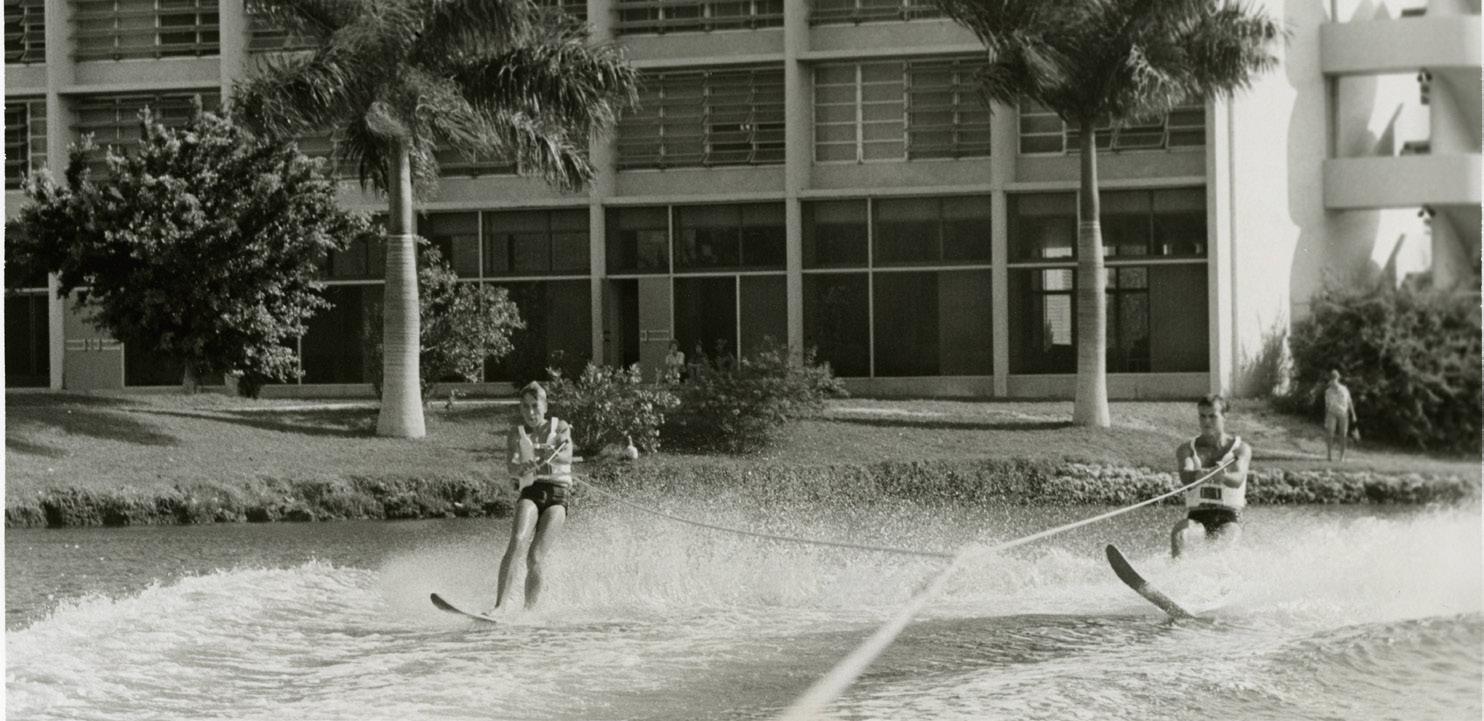

These spaces have adjusted over the years to match the needs of the university. For example, Lake Osceola, the heart of today’s University of Miami Coral Gables campus, has not always been part of UM. It was originally a canal that connected terrestrial freshwater systems from the Everglades to Biscayne Bay and was developed into a lake as part of UM’s campus expansion in the late 1940s.

Due to its connection with other natural water bodies, wildlife began to inhabit the lake, including different kinds of fish and even manatees. The lake was named by the Iron Arrow Honor Society, UM’s highest honor society, in recognition of Osceola, a Seminole tribe leader and historical figure in Florida.

Today, students can be found relaxing by the lake eating Starbucks or Corner Deli, working on the nearby steps or even fishing.

“When I’m walking around campus in between my classes, I love seeing the lake and remembering why I chose this beautiful campus,”

Emma Paccione, a freshman studying finance, said. “I really don’t think campus would be as lively, or feel the same without the lake.”

Today’s landmarks

Across from the lake sits the Shalala Student Center, a 10year project that officially opened in fall 2013. Initially called the Student Activities Center, it was later renamed in honor of Donna Shalala, UM’s president from 2001 to 2015.

make way for the new Shalala Center, where the Rat would be relocated. The restaurant temporarily moved to the University Center before opening its current location on Aug. 20, 2013.

“That Rathskellar was not similar at all to the one we have now. It was limited to only students and faculty. There were concerts on weekend evenings,” Mitchell Shapiro, UM alum, professor and director of the School of Communication Honors Program said. “It was two stories. The first floor had a restaurant, and the second was only on the periphery with more seating and a stage where artists would perform.”

Today’s Rathskeller blends modern and rustic design elements to create a relaxed, student-friendly atmosphere. The Rat features indoor-outdoor flow, large glass windows and waterfront seating under umbrellas and palm trees. The interior features decorated walls, wooden furnishings and a pub-like ambiance.

Designed for social interaction, the space includes high-top tables, comfier couch seating and an open bar area, making it a central hub for students.

Notable buildings

Whether it’s due to an iconic architect or distinctive architectural features, several campus buildings have been deemed “notable” by the Department of Facilities Operations and Planning. These include the Oscar E. Dooly Memorial Classrooms, J. Nev-

a high school that bears his name, says sincerely, ‘I owed it to the community. And as long as I live, I am going to contribute to its welfare.’”

Designed by Miami architect Wahl Snyder, the five-story structure features a concrete-block first floor with frosted clerestory windows above. The southeast upper stories are screened by a distinctive metal grille made of diagonally cut cylinders, which covers a wall of fixed metal windows. On the northeast façade, pebbled panels and grouped metal windows define the exterior, while large concrete planters flank the stairs to the southeast entrance. Built in 1967, the James M. Cox Science Building maintains its original appearance and architectural significance. Its design adopts brutalist features, such as exposed concrete, angular geometry and structural transparency. The building also incorporates elements of the Miami Modern (MiMo) style, including mosaic tilework, attention to sun protection and seamless transitions between indoor and outdoor spaces.

Funded by a $20 million gift from Bruce and Tracey Berkowitz, Shalala offers a 24-hour study space, student organization offices and a 1,000seat ballroom.

With its opening, student organizations also gained a dedicated space to establish private offices, instead of sharing facilities in the much smaller Whitten University Center.

Shalala’s sleek architectural style features clean lines, open spaces and large glass windows that provide natural light and offer scenic views of Lake Osceola. The building’s design encourages movement and interaction, with multiple terraces, meeting rooms and lounges that accommodate both social and academic activities.

The Rathskeller, UM’s on-campus restaurant and bar, opened on Dec. 18, 1972 as a stand-alone building. Originally housed in Gautier Hall, named after Charles Gautier, the late chairman of the Board of Trustees’ Subcommittee on Student Affairs, the Rat became a student-run business under the Dean of Students Office.

“Rathskeller” is a German term meaning “council’s cellar,” historically referring to a tavern or restaurant in the basement of a city hall or university building. The Rat continues that tradition, serving as a community gathering place on campus.

In June 2011, Gautier Hall was demolished to

ille McArthur Engineering Building, James M. Cox Science Building, Ashe Memorial Administration Building and the Otto G. Richter Library.

“I love walking towards Cox and seeing the beautiful double helix staircase designed to represent DNA,” Lucas Velasquez, freshman computer science major said. “It’s thoughtful and cool to see how they mixed science with architectural design.”

Constructed in 1947, the Memorial Classroom Building was the first permanent academic structure opened on the Coral Gables campus after World War II. Designed by Marion I. Manley and Robert Law Weed, the 680-foot-long building originally featured 58 classrooms across a two-story north wing and three-story south wing.

Between the wings stood the Beaumont Lecture Hall, which included a small stage and seating for 290 people. This space was later converted into the Bill Cosford Cinema. The building’s orientation is also a key design feature. Its classrooms face east to avoid direct sunlight after 9 a.m., helping to keep them cool.

Thanks to a $1 million donation from J. Neville McArthur, the engineering building bearing his name was constructed in 1959.

“The distinguished gentleman and civic leader, who gave a million dollars to the University of Miami for a School of Engineering,” the Miami Herald wrote about McArthur in 1961, “And 40 acres for

The Ashe Administration Building, named in honor of UM’s first president, Bowman Foster Ashe, symbolizes the university’s transition from the rapid post-war expansion era to a period of planned growth. Completed in 1954 and designed by Watson and Deutschman, the building includes a seven-story north wing connected to a two-story south wing. The north wing’s exterior features stucco and pebbled panels, with window bays inset among projecting piers and floor slabs, evoking the “egg crate” look of Eaton Hall. Its fenestration includes single-light metal pivot windows with porcelain-enamel and steel panels in the bays below. A wall of Oolitic limestone runs along the base of the first story. The south wing’s second story cantilevers over the first, and its exterior is clad in stucco. A continuous ribbon of fixed metal windows lines the upper floor, completing the building’s streamlined, functional aesthetic.

Historical landmarks

1300 Campo Sano is the only remaining building of “The Shacks,” a group of temporary wooden structures built to accommodate the post-WWII student boom at the University of Miami. Originally constructed in 1947 as one of five semi-permanent buildings made from army surplus materials, it served as the administration building alongside a cafeteria and three science buildings. Its design, influenced by early plans for the Dooly Memorial Building, featured exterior corridors, open porches and staircases that allowed each room to have windows on opposing walls, maximizing airflow in the days before air conditioning. Restored in 2013 to its original 1947 appearance, 1300 Campo Sano has since earned multiple awards for historic preservation. It is now home to the George P. Hanley As the University of Miami celebrates its centennial, today’s campus landscape is a testament to a century of growth, transformation and tradition. From Lake Osceola’s evolution to Centennial Village’s creation, each landmark reflects UM’s commitment to innovation while preserving its rich history. Over the next 100 years, one thing is sure: UM will continue to shine, evolve and inspire future generations.

By Lauren Ferrer Managing Editor

A maze of scaffolding and cranes greeted student media on Tuesday, March 19 as the group was guided through the University of Miami’s largest active construction site, Centennial Village phase two.

Guided by project leaders with Coastal Construction, the group got a close-up look at the three new residence halls going up on the Coral Gables campus expected to open in August 2026. The project marks the second phase of the University’s Centennial Village student housing initiative, which aims to modernize and reimagine the first-year residential experience.

“Everything is at a different stage,” Senior Project Manager Lonny Shnur said. “Some buildings are still getting windows. Others are already working on interior framing.”

The site includes two new buildings, labeled 2A and 2E in internal documentation. Building 2A, which includes two towers connected by a bridge closest to the Frost School of Music, will stand eight and ten stories tall, while 2E, near the Herbert Wellness Center, will have nine floors.

Combined, the three towers will house 1,149 beds across 660 rooms. The design emphasizes shared spaces, with every floor featuring study rooms, lounges and communal bathrooms. Each tower also includes a meditation room, faculty apartments and administrative spaces for Housing and Residential Life staff.

Each building also includes HRL administrative spaces on the ground floor, including offices, conference rooms and student staff areas.

One unique feature of the new phase is a bridge on level seven that will connect two of the towers, an architectural element that distinguishes this project from phase one which focused on the new dining hall.

“Each project has its own challenges,” Assistant Superintendent Michael Perez said. “For phase two, the chill beam units keep getting delayed by manu facturers. That’s held us up on finish ing interiors.”

To compensate for delays, the crews have been working long hours, often from 5 a.m. to 7 p.m., building morale through weekly team barbecues

Everything is at a different stage. Some buildings are still getting windows.

Others are already working on interior framing.”

Lonny Shnur Senior Project Manager

and impromptu cookouts on Fridays.

“It’s brought us closer together,” Perez said.

“We’re all here to get it done.”

By Tracy Ramos Contributing Writer

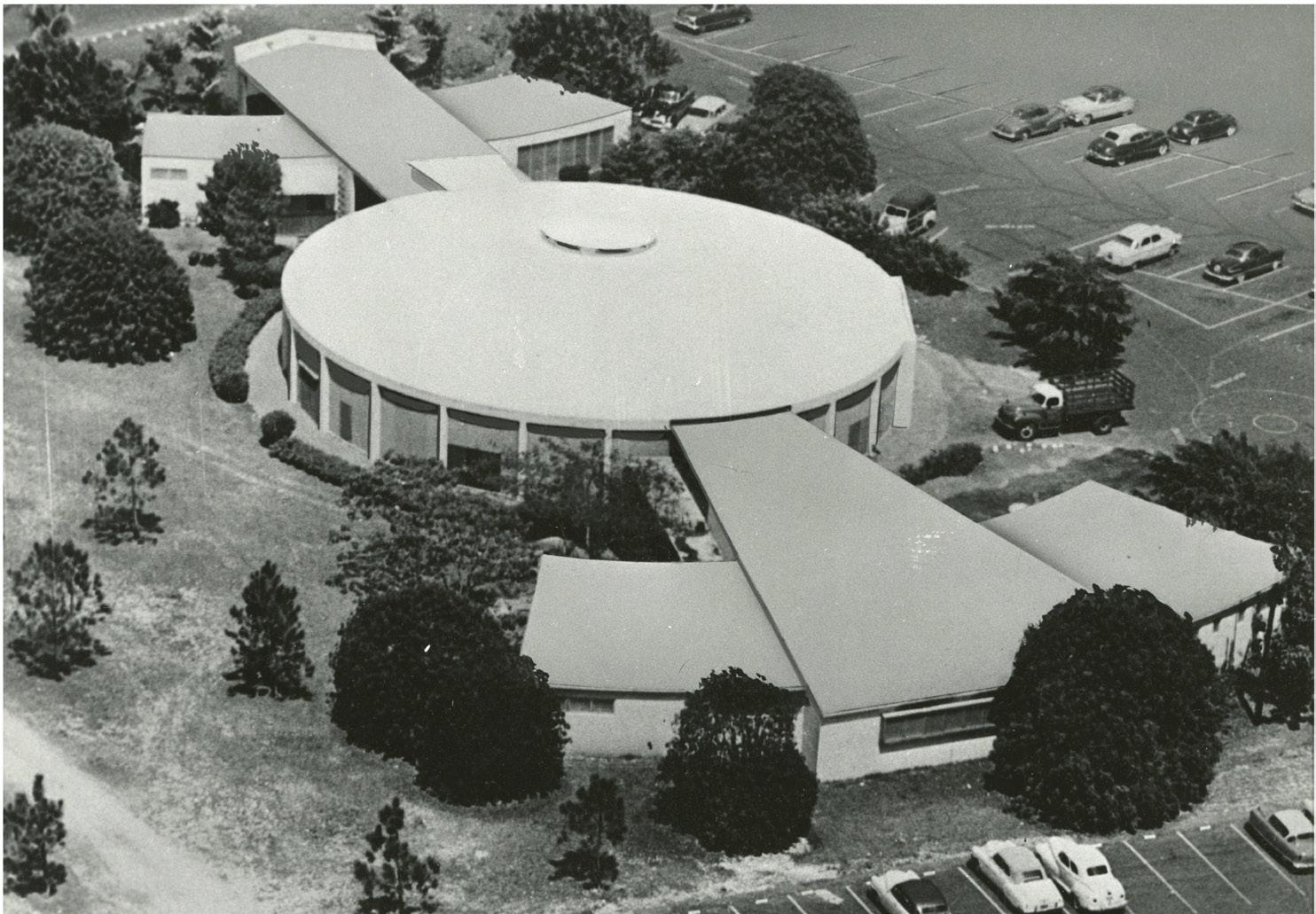

When the Jerry Herman Theatre opened in 1951, heads turned, but not from the audience. It made national headlines for its circular design, which allowed spectators to sit in a ring around the stage.

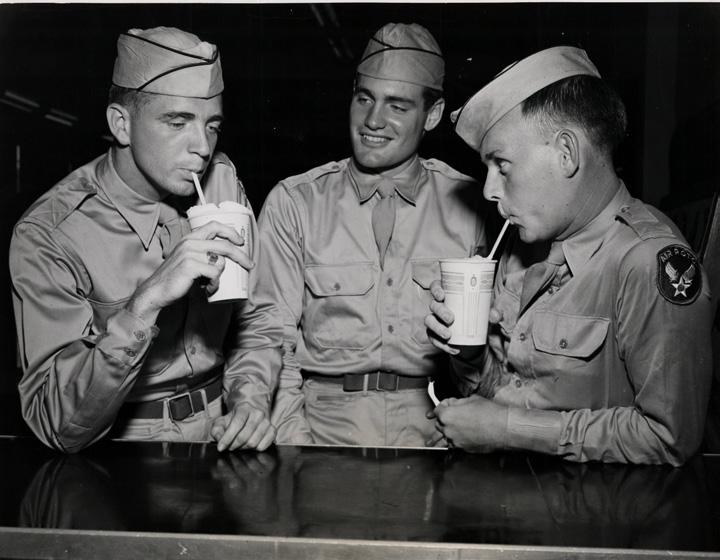

Originally named the Ring Theatre, its design was inspired by the configuration of the rotunda in the Anastasia building. The building was a hotel that UM purchased to serve as its temporary home until the Merrick building’s construction was completed. Theater students performed in the Anastasia building after it was used to train WWII air navigators.

Even during the war, theater thrived on campus. In 1942, the Miami Herald covered a student production of the Mexican comedy, “Sunday Costs

Five Pesos,” at the then called University of Miami Theater. The play tells the story of a small northern Mexican town, Four Cornstalks, where women who fight on Sundays have to pay a five-peso fine.

Theater professor Frederick Koch Jr. spoke to the Herald, emphasizing the “need for arts in a war world.”

Performances moved to a circus tent until construction for the current facility finished in 1950.

After renovations in the 1990s, the theater had a 306-person seating capacity and was renamed after UM alumnus Jerry Herman. A Tony-award-winning Broadway composer and lyricist, Herman was known for “Milk and Honey,” “Hello, Dolly!,” “Mame” and “Dear World.”

In 2009, the theater department staged a production of “Hello, Dolly!” and received a heartfelt letter from Herman ahead of the opening night.

“I’d like everyone connected with Dolly to know that my heart is with you,” he wrote. “And what a special thrill it is to have it playing in my namesake theater. If you hear a strange voice singing along with the curtain calls – it’s me from Los Angeles.”

Joy Missey, a senior musical theater major, said

performing in shows with the arena seating configuration has enriched her education.

“Performing in the theater, which is one of the only theaters in the U.S. where audiences can sit around the stage, has taught me how to perform to people all around me,” Missey said. “It’s prepared me for performing in different settings after graduation.”

Graduating seniors have participated in the tradition of signing their names on the theater’s signature wall since the 1960s. E.V. Cummins, a senior musical theater major, is excited to add her name to the list.

“I’m really looking forward to leaving my mark on a space I’ve performed in so many times,” Cummins said. “I’m honored to have my name among so many notable alumni on the wall.”

Broadway actor Joshua Henry, known for starring as Billy Bigelow in the third Broadway revival of “Carousel,” and actress Dawnn Lewis, known for her role as Jaleesa Vinson–Taylor on the NBC television show “A Different World,” are among the names of alumni on the wall.

Ramanjaneyulu Doosari, assistant professor of theatre arts, said the theater is critical to the department and University’s futures.

“Without it, how can we teach students where we started as a program and where the University was decades ago?” Doosari said. “It’s important to remember our roots so we can see how far we’ve come.” Doosari also recognized the theater’s importance in the South Florida community.

“People going to live performances and not just watching entertainment on TV is important because of the human connection,” Doosari said. “For centuries, people have enjoyed the human connection in theater and that desire will never go away.”

The Jerry Herman Theatre’s not done making history yet. Check out its upcoming production of “Seussical: The Musical” from April 22-26, which draws from the worlds in Dr. Seuss’ books, “The Cat in the Hat,” “Horton Hears a Who!” and more. To purchase tickets, visit the Jerry Herman Theatre website.

By Martina Pentaleon Staff Writer

What started with just eight student leaders has grown into a powerful presence on campus. From the parking prices, to the cost of tuition and dining hall food quality, SG’s has played a role in shaping the student experience for a century.

This year, the student body elected Ivana Liberatore to continue this work as SG president, alongside her Brand New U administration, extending its legacy of advocacy.

For decades, SG presidents have left their mark. In 1967, Dennis Richard became the first independent candidate elected president and developed the proposal to establish SAFAC. Three years later, Ray Bellamy became the first Black student and student-athlete elected to the role. After a career-ending injury caused him to lose his athletic scholarship, he successfully advocated to the administration for the creation of student government chief executive officer scholarships.

“If through my work as president, I can extend the welcoming and accepting environment I experienced at UM to every student, it would be the greatest privilege of my undergraduate career,” sixty-sixth SG president Roy Carrillo Zamora said to the Hurricane when he got elected in 2024.

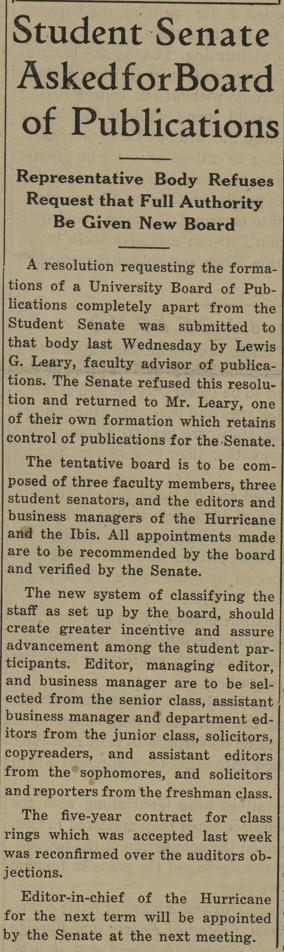

The organization Established in 1927 as the Student Association, SG was composed of an Honor Court, a Senate and eight executive board members: the president, vice president, secretary-treasurer and the secretaries of athletics, foreign affairs, publication, state, traditions and social affairs.

“I do solemnly swear that I will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, defend, and enforce the provisions of the Constitution and Laws of the Senate and the Decrees of the Honor Court of the Student Association of the University of Miami,” a portion of the 1929 oath of office stated.

The Senate, representing the original 646 students in 1927, had three senators for the School of Liberal Arts, the School of Music, the School of Art and the School of Law.

With the expansion of student organizations, the number of chairs grew to represent all students on campus. By 1995, 31 student groups were represented with 38 senators. Two committees were added in 1981, and the Honor Court evolved into the Supreme Court.

The University Affairs Committee connected students with “dorm government”, similar to what the Campus Liaison Council and Senate Committee of University Affairs do today. The cabinet position for Organizational and Ethnic Relations interacted with other student organizations, combining the tasks that are now overseen by the councils.

Agencies

Starting in 2000, SG began adoption agencies to further enrich the student experience. Category 5 was established under SG president Shane Weaver to provide funding for student pep rallies. Today Cat5 is the award-winning student section, promoting school spirit at all athletic events.

ECO Agency was founded in 2012 to promote sustainable living on campus. However, sustainability proposals like the ad hoc committee for university recycling, created in 1995, have had a place at the University for decades.

During her tenure as UM president, Donna Shalala was known for bringing influential speakers like Justice Sotomayor and Dalai Lama. To continue the culture of bringing speakers to campus, SG president Evan De Joya established What Matters to U in 2018. Since then, influential leaders and celebrities including Josh Peck, Pitbull and Tabitha Brown have come to campus to speak to students.

Elections

The elections process has always been a part of SG, but was formalized in the ’30s to ensure fair and equitable elections. Students have always voted on the executive branch and senators, but the cabinet,

though, was appointed by the president.

Initially, members of the Elections Commission would hand count all of the ballots. Tensions began in 1981, when election results were put on hold because both tickets were almost disqualified. It happened again in 1986 due to complaints against candidates. By 1994, students claimed that some candidates were erased from the ballot.

The election processes were reformed in February 2000 due to allegations of fraud. Instead of voting throughout campus, students could only vote in the Breezeway.

“Elections should be fair.” said Chris Roby, the director of student activities and leadership programs in 2000. “The last thing we would want to do is declare elections invalid because it would be a waste of everyone’s time and effort.”

Advocacy

To make sure students were heard, SG used to hold weekly meetings where they would distribute a

“Gripe Card” where students could give suggestions for improvements. Now, the “Gripe Card” has become “Share an Idea,” a survey available on the SG website.

Tuition has been a point of contention for students for years. SG’s efforts to stop a $500 increase in tuition resulted in a campus-wide protest in 1980, organized by SG.

During the fall of 2024, SG advocated for the expansion of Freebee, UM’s late-night transportation service. But before there were cars, there were Nightwatch Escorts. In 1981, SG sponsored the Nightwatch Escort Program, a service provided by the Student Security Patrol Office, which provided an escort from sunset to 1 a.m.

Following the death of a student who was hit by a car while crossing a U.S. 1 intersection in 2005, the Senate sponsored the bill to construct an overpass across U.S. 1. An overpass across U.S. 1 was created, improving student security.

The bill, which passed unanimously, was named the Ashley Kelly Resolution, “in memoriam of the death of Ashley Kelly in hopes that a tragedy such as hers should not be repeated for lack of action on the part of the University, its students and the greater community of Coral Gables.”

The University of Miami welcomed its first female president in 1933 when Aileen Booth, elected as vice president originally, took over when Stanford Kimbrough dropped out.

Decades later, in 2015, Brianna Hathaway made history as the first Black woman elected SG president. Most recently, in 2023, Roy Carrillo Zamora became the first international student to hold the position.

“Student Government should strive to help create a campus that its students, alumni,

and community can be proud of,” Hathaway said. “It was an honor and a privilege to be

and

By Jenny Jacoby Editor-in-Chief

Thirty feet underwater, a group of ’Canes race to preserve coral species as one of the most severe heat waves threatens coral reefs into extinction. Far away from the reefs, in medical labs, scientists are working at the microscopic scale to restore mobility to paralyzed patients. Others are reversing blindness.

The University of Miami operates on a research budget of $492 million, putting it in the top 70 university research budgets in the country. Research projects encompass a myriad of fields, but three in particular have emerged as some of UM’s most distinguished and crucial contributions to research and scientific advancements.

The best in the eye game

Bascom Palmer Eye Institute has been ranked the best in the country for 21 years in a row, and 23 throughout its history. It’s a reputation of excellence that did not come easily.

The institute dates back to the 1920s when Bascom Headen Palmer, M.D., opened one of Miami’s first ophthalmology practices. Edward W.D. Norton later founded the institute in 1962 in Palmer’s name, a decade after the School of Medicine was ordained.

Bascom Palmer has since become, “one of the world’s foremost academic centers for scientific discovery and clinical innovation,” according to Executive Director of Business Operations Marla Bercuson.

Bascom Palmer’s reputation for being the best eye institute comes from several breakthroughs that changed the field of ophthalmology. In 1993, the institute completed the first posterior lamellar endothelial transplantation, a surgery that only removed the diseased inner part of a cornea, instead of the cornea in its entirety. Later, in 2006, Bascom Palmer had another massive breakthrough when it discovered treatments to age-related macular degeneration, which can cause blindness.

Now, the team is working on the project of all projects: a total eye replacement.

“Undoubtedly, our most ambitious research initiative is finding a way to transplant an eye and restore vision through the optic nerve” Bercuson said. “This is our “moon-shot” project, which would lead to new therapies for potentially blinding diseases like glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy.”

The hope is to replace a failing eye with a bionic one, likely in the form of a biological eye altered to include a chip, or other technology, to restore the ability to see.

Bascom Palmer is currently led by Dr. Eduardo Alfonso, who oversees more than 30 labs and spaces dedicated to improving eye care, in whatever way that takes shape.

“I am the most proud of the TEAM that we have assembled at Bascom Palmer. To me, TEAM is not just an acronym. ‘Together, everyone achieves more’ represents a place where everyone works together to solve problems, create solutions, and generate innovation and success that would not be possible by oneself,” Alfonso said.

The statement echoes those frequently made by his predecessor, Norton. Norton always credited the institution’s success to its faculty. His philosophy has been coined into the Norton Principles, 15 guiding beliefs that have kept Bascom Palmer in line

with its goals.

Outside the labs, Bacom Palmer has an arguably even bigger impact, supporting and bringing eye to the communities in the most need.

Bascom Palmer has led several boots on the ground campaigns around the world, often operating out of its Vision Van, a medical vehicle specially equipped for mobile eye care. The van has traversed several cities post-natural disaster, from New Orleans after 2005 Hurricane Katrina to Japan in 2011 after the Tohoku-Pacific Ocean earthquake and tsunami.

Following Hurricane Maria’s devastation in 2017, Alfonso himself flew to San Juan, Puerto Rico with a team just a week after the storm hit, helping to distribute medication for patients with glaucoma and identify high risk patients that needed immediate care to avoid blindness.

Locally, Bascom Palmer runs the 33136 Initiative, to improve the health of low-income neighborhoods in the area surrounding the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine campus and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

“Children and adults are given free eyeglasses, sunglasses, or goggles, and if needed, people with serious vision problems are seen free of charge at Bascom Palmer for further treatment or surgery,”

Bercuson said.

Warding off a climate catastrophe

Running along Florida’s coasts is a 350 mile linear track of coral reefs, the third largest in the world and the only reefs found in the continental U.S.

Since the 1970s, 90% of the reef’s healthy coral cover has been lost, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates.

The Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science’s top scientists are racing against the clock to save this last 10%.

Dr. Diego Lirman is one of the leading researchers working to save coral. His lab oversees three underwater nurseries that house 10,000s of corals from about a dozen species. The corals are spawned in labs, then hung on tree-like structures in nurseries off Miami’s shore before being planted on an actual reef.

These young corals are essential to maintaining the health and diversity of the reef track, the lab explained. Many of the coral in the nursery were originally spawned from fragments of coral collected from reefs across Florida. Some of these parent colonies are no longer alive.

“With coral populations declining, genotypic diversity is also being lost, so it’s essential that we are able to preserve as much genetic material as possible,” Martine D’Alessandro, a senior research associate in Lirman’s lab, said.

The mass coral bleaching in 2023 nearly destroyed the Elkhorn coral, a branching coral important to reef structure, population in South Florida. Lirman’s team’s collected fragments have been able to survive, offering a glimmer of hope that they may one day be able to see numbers restored throughout the state.

But with coral dying at such a fast rate, the traditional outplanting process of attaching coral with nails and cable ties was not able to meet the reef’s demands. Corals were planted too slow and the effort was costing too much money.

That’s when graduate student Joe Unsworth made a huge breakthrough, a cement and micro silica “glue” combination that allows teams to plant more than 100 coral per dive. Previously, that num-

ber hovered around 30.

But, having to continuously collect, spawn and outplant corals is not a sustainable solution. A more permanent effort is underway to selectively breed the most tolerant coral types, essentially in a controlled survival of the fittest model.

“Some early observations have suggested that sexual recruits are more thermally tolerant compared to parent colonies, which suggests that corals are adapting to warming environments, but our concern is that they may not be able to adapt quickly enough to keep up with the rate of global climate change,” D’Alessandro said.

In 2024, Rosenstiel and partner universities were awarded a four-year, $16 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Habitat Conservation Program Office to continue to fund the development of resilient corals.

None of this matter though, scientists explain, if the ocean continues to warm to unprecedented temperatures. Quelling the rise in temperatures is a significantly more challenging feat that requires the cooperation of billions of people.

That’s where Rescue a Reef comes in.

“We don’t have the capacity to out plant enough corals onto the reef to combat the mortality that we’re seeing as a result of climate change,” Devon Ledbetter, the engagement program manager of Rescue a Reef, said.

Lirman established the non-profit as an offshoot of his lab meant to engage the public in an interactive discourse on corals and climate.

“Rescue a Reef’s primary mission is not necessarily to outplant as many corals as we can. Our mission is to use coral restoration as a bridge to close the gap between science and society and give the public the opportunity to create a personal connection and a personal investment in coral reef ecosystem health,” Ledbetter said.

The program has been able to reach more than 42,000 individuals and included 1,500 citizen scientists on their coral outplanting expeditions.

“We wanted to give people an opportunity to come out with us on the boat and experience coral restoration. Because hands-on learning has been demonstrated to be one of the most impactful and long lasting kinds of learning that we can offer,” she said.

Curing paralysis on patients’ terms

On October 26, 1985, Marc Buoniconti made a play that would change his life. In a football game against East Tennessee State University, Buoniconti sustained a spinal cord injury (SCI) that left him unable to move any muscles below his neck.

That same year, Buoniconti and his family founded The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis, a medical institution committed to improving the life of patients with SCI and researching to find solutions.

It has become a world leader in the effort to cure paralysis.

“We can confidently say we are the most comprehensive Spinal Cord Injury Research Center in the world,” Dr. David W. McMillan, the director of education and outreach, said.

A good way of understanding how The Miami Project operates is to look at its logo. It’s a pretty straightforward depiction of a sequence of stick-fig-

ure drawings that go from a seated position in a wheelchair to standing upright.

“It implies that the cure for paralysis is going to be when someone can stand up again, right? We even have a logo, a motto, ‘Stand up for those who can’t’,” McMillan said.

The next step is to forget about the logo, because for most patients, leg function is at the bottom of their priority list, he explained.

When Dr. Kim Anderson-Erisman asked people with spinal cord injuries what their main hope was, they said to regain control of their hands. This was followed by control over the bowel, bladder and sexual function, three functions essential to daily life.

The Miami Project is accomplishing this, operating across several disciplines to find the best ways to better the patient experience through as many avenues as possible.

UM participated in Project Uplift, a study that looked at stimulating the spinal cord, with several other universities. At its conclusion, the FDA licensed, for the first time ever, a medical device to restore movement in the hands of people after chronic tetraplegia.

“We’re seeing that [results] in people that have had injuries for like 30 years,” McMillan said.

On the front of fertility, UM’s research teams have also been instrumental.

“35 years ago, if you were a man living with a spinal cord injury, it would be very, very difficult for you to have a baby,” he said. “Now we are very confident we can help you to have a baby. You can become a father, and it’s due to some pretty simple but nuanced medical interventions here at the Mi-

“We’re seeing [results] in people that have had injuries for like 30 years.”

Dr. David W. McMillan SCI Director of Education & Outreach

ami Project.”

Of course, total restoration of function is the leading goal at The Miami Project. Scientists have reported that most vertebrates are able to regrow cut nerves outside of the brain and spinal cord, but not inside.

Researchers haven’t been able to discover why, but Dr. Mary Bartlett Bunge thinks it may have something to do with Schwann cells, the insulating cells that help protect a human’s network of nerves. These cells are found throughout the body, but not in the brain and spinal cord.

“She was like, well, if we take them out and we put them back in, in a way, then maybe they’ll be therapeutic,” McMillan said.

The hope is that the Schwann cells help regrow axons, a part of a nerve, through the spinal injury. This would essentially, in theory, restore function. The studies to determine if this is effective are currently underway. Medical research is a slow moving process however, so there’s no definitive timeline of when scientists will know if this works.

In the meantime, McMillan is motivated by how far The Miami Project and paralysis restoration has come. To him, the simple fact of someone with SCI being able to enjoy their life is monumental.

“Marc Buoniconti is celebrating the 40th year of his injury this year, not the 40th year of his life,” McMillan said. The fact that he can make it this long, thriving, leading a 200 person right center of excellence with his tetraplegia is a modern medical phenomenon that was not possible multiple years ago. It’s an important perspective.”

By Editorial Board

Continued from Page 1

The Hurricane must exist. It’s woven into the structure of UM and serves as a necessary bridge between student life, administration, faculty and alumni. To lose the newspaper would be to lose the voice of students altogether.

The Hurricane’s vital role

On a random weekday in 2024, students received letters alerting them that their fnancial aid was going to be adjusted as a part of a Financial Aid Course Audit. The email said their classes were not a part of their course of study and would cease to be covered by fnancial aid.

No one knew what that meant and no one at the University would comment. This out-of-theblue email had threatened to push students to take out tens of thousands in loans or graduate semesters earlier than planned.

Frustrated students began to privately message members of The Hurricane at all hours asking if we could help them understand the policy. Some students tried to solve the issue independently. Some told their parents. Some complained to faculty members. But the University failed to clarify its policy for weeks.

“When there’s an information void, there’s rumors, there’s panic, and there’s no spotlight on what the government is doing,” Sallie Hughes, department chair of journalism and media management at the School of Communication, said.

“So student newspapers have a huge role to play.”

When students felt abandoned by the university they paid for, The Hurricane was there.

We played a crucial role in capturing the widespread anxiety of students and parents. To write our articles, we sent the University non stop requests for comment, conducted student interviews and researched the policy. We were then able to publish an explanation of the policy, cover student’s discontent with the University and even author an editorial imploring the University to be more transparent.

Following our coverage, the University explained exactly how the policy worked, allowing students and parents to plan their academic paths. When student voices are united and have a newspaper to amplify those voices, the University is more compelled to address them.

“They report on not just policy changes, but when things happen in the school,” said sophomore architectural engineering major Bahar Arian. “Like when the president steps down, obviously we hear about that, but when they change their policies or when academic structures change … you couldn’t fnd that information elsewhere. I’m not going on UM’s website to see if they talk about that, if they even disclose it.”

Steven Priepke, deputy dean of students and fnancial manager for student media, said that student media on campuses is “everything.”

“I think it’s so important not to be afraid to say what is on students’ minds, and to explore that and talk about that is at the very heart of what education and journalism is supposed to be,” said Priepke.

What happens then if student media is not

opinions of the study body.

We need to change, but so do you

By Editorial Board

The Miami Hurricane has survived at UM for almost 100 years, but with print media dying, the traditional newspaper is struggling.

In 2022, only 8% of college students nationwide read the print edition of their campus newspaper, and 18% read the online edition. And why should they, if their own college newspaper isn’t even engaging with them?

As much as we expect you to meet us in the middle by reading and sharing our stories, the responsibility to be informed does not rest totally on your shoulders.

TMH works each year to reevaluate what types of stories draw the most interest from students and where they prefer to interact with that information. In the past few years, TMH has added a podcast, redesigned its social media posts and made its website more accessible.

We have focused on developing our breaking news reporting to get information out faster and conducted several investigations.

“I think that there’s no problem with TMH continuing to exist well into the future,” Priepke said. “They will always have to continue to adopt and adapt to whatever the electronic way is to reach the generation of the day.”

We hope that with UM’s help and by continuing to modernize, TMH will live to see another century, but we need engaged readers. Because, after all, what good is a newspaper without our readers?

Online sites have proven that students are open to reading about campus news. What makes platforms such as RedCup so popular among UM students? The gossip? The humor? Maybe a little of both, but the key to their popularity is the opportunity for student interaction.

TMH plans to continue fnding ways to connect directly with the student body. Our staff is exploring the ideas of dedicated student sections in the print edition, news-tip focused tabling and engaging social media prompts to garner quick

there? Will the university have to rely on the unmonitored posts of anonymous instagram accounts or will they turn to News@theU, the university’s sanctioned news and communication platform?

While a genuine source for information that shared the many accomplishments of the school, News@theU is ultimately a part of the university’s public relations vision. They are unlikely to publish the unsavory and hard-to-discuss events of the day. Unlike TMH, News@theU was not rushing to cover the collapse of Mahoney-Pearson roof on March 30, 2025.

TMH’s coverage is the frst draft of the history of the university.

Sometimes this history isn’t pretty. TMH covered every step of desegregation on UM’s campus, interviewing black student leaders when many others refused to give them a voice.

These archives are now essential to constructing UM’s history, refecting on the university’s journey to racial equality and appreciating the trailblazing commitments of civil rights leaders on campus. It’s a history UM is now proud to tell.

Our irreplaceable effort

When students bought parking passes for the Red Lot in 2023, they did not realize that the spots would be impossibly narrow. Most cars covered multiple spots, forcing students to miss classes as they searched for available spots. Parked cars were commonly scuffed and crashes happened daily.

RedCup Miami, another form of student media, publicized the issue with videos of crashes, dents and hit-and-runs. The posts helped to capture the mayhem that Red Lot parkers experienced. This awareness is important and the Hurricane values the work that RedCup does to represent its students. With that, the Hurricane and RedCup serve different roles, each essential in their own way.

The exhaustive work that goes into a Hurricane article is what differentiates it from social media platforms. When we added to the RedCup coverage with our own piece, we solicited responses from the University about the issue, consolidated student opinions from a range of sources and provided important context for those outside of the UM community.

Our article will live on as part of the historical record of the University of Miami. In 100 years, readers will be able to look back and see the story about the Red Lot in its entirety via our article.

The Hurricane is the most comprehensive, neutral and accurate source for this information.

Unlike new, alternative forms of media, our reporters follow ethical principles and are committed to reporting the truth. Most social media accounts do not professionally fact check their stories, nor do they carry out interviews to achieve a well-rounded presentation of information.

Big headline stories like these don’t get written overnight. They require intense commitment and skill.

“When the student newspaper prints an article that people really want to read, sometimes it’s so popular that the site is busy,” Priepke continued. “Those are exciting times. I think that’s always possible. As long as that’s possible, you’ll have a

student newspaper.” When affrmative action was overturned in June 2023, our editorial team immediately took note of how it could impact the university. We stuck with the story for months. When UM hesitated to share enrollment demographics in the fall, we pushed back.

For weeks, our reporters had heard whispers from student leaders that freshman membership in Black student organizations was noticeably low. After several conversations, UM entrusted us to receive that data before anyone else. In the end more than 100,000 people viewed the story. That story, seemingly simple, was a culmination of months of work. If readers only care to support us in those top headline moments, who will be there in the in between moments?

Money still matters

We’re 1,300 words into this article and have yet to even talk about funding.

Journalism revenue has cratered over the past few decades. Digital journalism has wholly replaced print journalism at some university and local papers, eliminating print advertising revenue which was once their largest source of funding. A Pew Research Center study found that between 2008 and 2018, newspaper advertising revenue fell from $37.8 billion to $14.3 billion, a 62% decline. The result is that many newsrooms can’t afford to pay many of their employees.

The challenge in securing funding extends to college newspapers. Our paper relies on fnancial support from the University, which gets supplemented by advertising revenue. While most of the University funding goes to the paper’s overhead, the advertising revenue goes directly to compensating our writers, editors, and printing. If advertising dollars dry up, then we would be forced to reduce compensation.

How is that relevant to our readers? Advertisers care when students are engaged with the paper. The more readers, the more ads and more revenue. What can you do to help?

Most people, unfortunately, fnd it easy to ignore newspapers. They complain that news can be negative, even depressing. It can require thought and refection to understand a story. And it takes time to read what TMH publishes every week. But as a paying student of this University you should want to stay informed. It’s crucial to stay aware of what the university is doing and if that is in line with your values and expectations for your college experience.

Your support and engagement matter beyond improving our readership numbers. As much as you count on us to let you know when something important is happening, we have to trust that you’ll have our backs if our place on campus is threatened.

TMH is dedicated to continuing serving students — covering important issues, empowering student voices, holding individuals accountable and adapting to the times.

Even though this staff won’t be around for the next centennial, our fondest wish is that those who are will come to celebrate UM’s 200 years and fnd The Miami Hurricane’s nameplate still splashed on every corner of our campus.

Changes are happening in the School of Communication as well. Sallie Hughes, department chair of journalism and media management at the School of Communication, is working on a new program that would expand the Community Wire, an independent community news outlet in the School of Communication staffed primarily by graduate students, taking it to “the next level.”

The University is looking to hire a new faculty member in digital journalism and local news collaborations to lead an initiative that will leverage the combined strength of UM’s student media platforms, upper-level undergraduate classes and graduate student work through local and statewide partnerships.

“We are looking for ways to help the Hurricane have an even broader reach…to use their talents to produce journalism about communities in South-Dade county and in Miami that aren’t being covered, “ said Hughes. “From a social impact standpoint, the students get to see how jour-

nalism can make a difference in the community. From a professional development standpoint, they see their good work reaching more people, having a bigger impact…I think it’s a win-win.”

But for our efforts to work, we need you to participate.

If our community immediately clams up when they hear the words “Do you consent to being recorded for this interview,” how are we supposed to do our jobs as reporters?

We already have Instagram posts asking people to submit tips and a button on our website where you can submit an anonymous form with information. These forms are rarely used.

And it’s not just students. In the past, TMH has had diffculty connecting with higher-ups for interviews and information about campus events.

So, while we work on modernizing and catering to your needs, you should think about what matters to you. Help us, help you, and in 100 years we’re confdent that TMH will continue to deliver the news to UM.

“I think it’s so important not to be afraid to say what is on students’ minds, and to explore that and talk about that is at the very heart of what education and journalism is supposed to be .”

Steven Priepke Deputy Dean of Students & Financial Manager for Student Media

By Michelle Mchado Contributing Writer

The University of Miami was once known for its nearby beaches, nightlife, and carefree social scene. In the 1980s, it frequently topped rankings as one of the nation’s biggest party schools, earning the nickname “Suntan U”.

However, over the past few decades, UM has undergone a remarkable transformation, shedding its “party school” image and reinventing itself as a world-class research institution. This shift was not accidental but the result of strategic efforts that changed the trajectory of the university.

UM has worked tirelessly to rebuild its reputation, focusing on academic excellence, research advancements, and attracting top-tier faculty and students. This transformation began under President Edward T. Foote II (1981–2001), who recognized the need to move beyond the “Suntan U” image. Foote raised admission standards, recruited distinguished faculty, and strengthened the university’s research focus. His successor, Donna E. Shalala (2001–2015), expanded on these efforts, securing major research funding, investing in state-of-the-art facilities, and forming strategic partnerships. To-

gether, their leadership laid the foundation for UM’s rise as a top-tier research institution.

One of the most signifcant milestones in this transformation was the university’s induction into the prestigious Association of American Universities (AAU) in 2023. AAU membership is reserved for only the top research institutions in North America, so this recognition marked a major turning point in UM’s evolution. As an AAU member,

UM now has access to increased federal funding, valuable research collaborations and a global academic network, which provide students and faculty with unparalleled opportunities. Being part of this elite group of institutions places UM alongside Ivy League schools and other top universities, enhancing its ability to compete on the world stage.

Alongside this achievement, UM invested heavily in enhancing its research capabilities. One of the most notable areas of growth has been in the Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science, which has become a leading research hub. The school’s innovative work in marine biology, climate science and atmospheric research has elevated UM’s global standing and contributed signifcantly to its newfound reputation as a research powerhouse. For example, RSMAS has played a critical role in climate change research and the preservation

of marine ecosystems, with groundbreaking studies that have garnered international attention. Since 2022, its researchers have led a $7.5 million DARPA-funded project to develop hybrid biological and engineered reef structures aimed at protecting vulnerable coastal regions in Florida and the Caribbean.

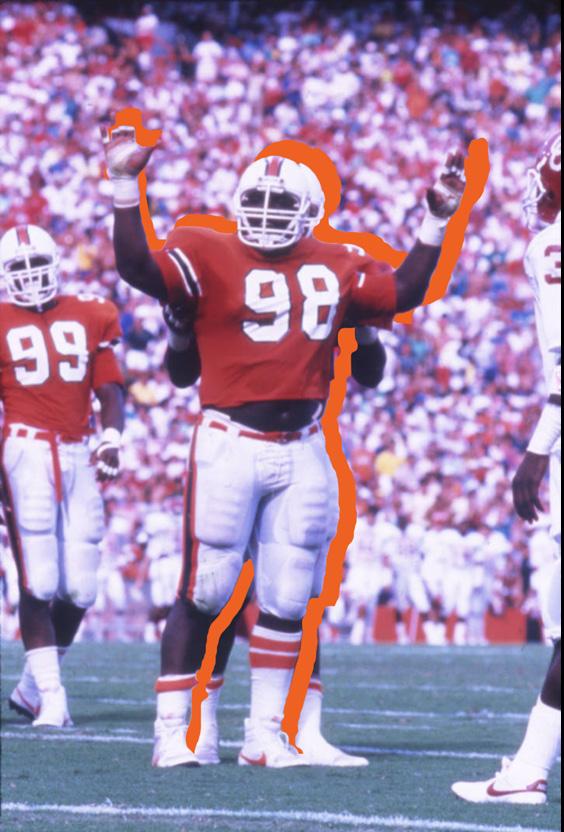

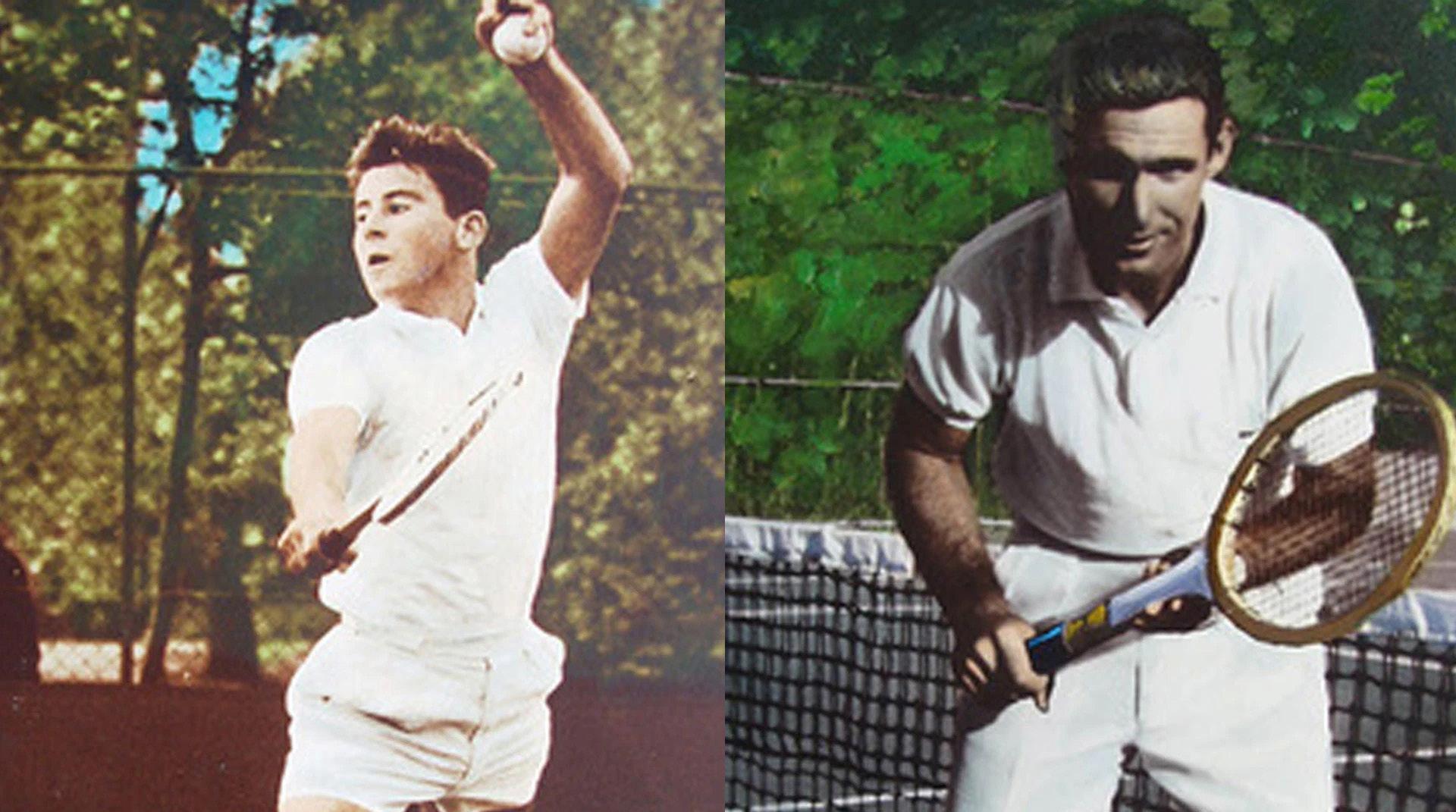

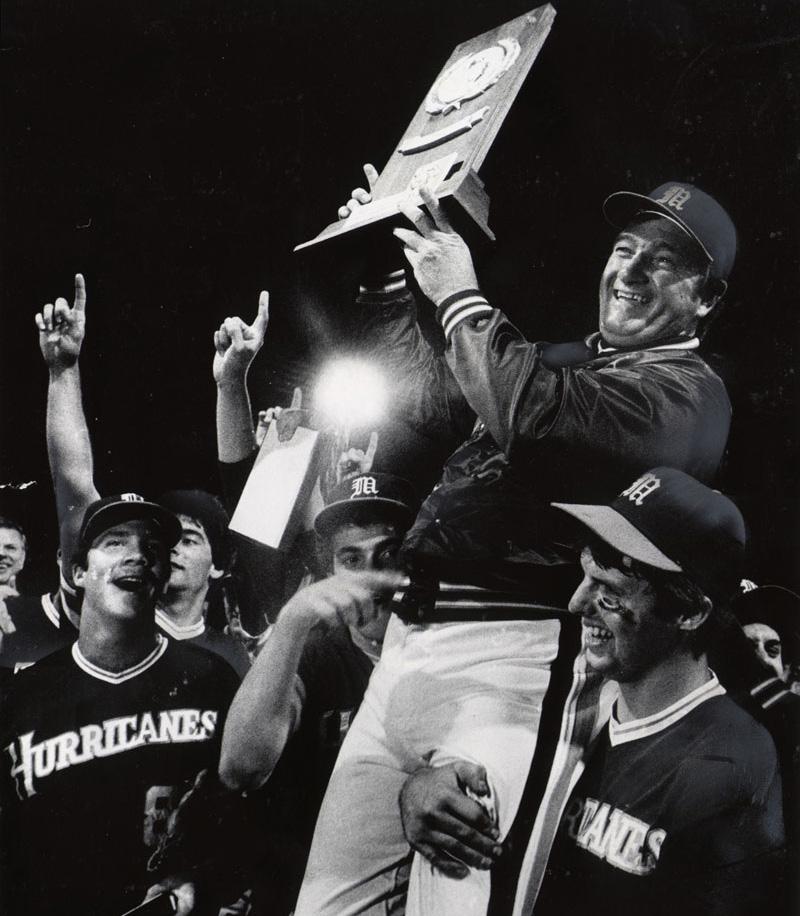

UM has also expanded research opportunities across other disciplines, investing in state-of-the-art facilities, distinguished faculty, and global research partnerships. For instance, its Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science has become a hub for marine biology and climate change research, while the Miller School of Medicine leads groundbreaking work in biomedical innovation. These efforts have strengthened UM’s academic standing and provided students with cutting-edge advancements in science and technology. UM has emerged as a leader in felds such as marine science, biomedical research, engineering and environmental studies with key programs focusing on coral reef studies, biomedical innovation, and sustainability challenges.