Contents

Foreword

Tom Mitchell, MW

How we produced this guide

Ava Lynam, MW/TUB

Resident review facilitated by The Glass-House

Empowering community champions as experts

Sophia de Sousa, The Glass-House

Workshop Takeaway : Overcoming particpatory idealism

Workshop Takeaway : Different values, different currencies

Reflection : So what is social value?

Nicloa Bacon, Social Life

Workshop Takeaway : Centring people in the particpatory process

Reflection : Play and community engagement

Dinah Bornat, ZCD Architects

Takeaway : Increasing financial transparency, fostering trust

Reflection : Visualising viability

Gemma Holyoak and Michael Kennedy, MEAD fellows

Contributors

Foreword

Words by Tom Mitchell, Partner Metropolitan WorkshopPeople Powered Places is Metropolitan Workshop’s second annual practice-based research project, and aims to critically appraise innovative methods of community participation in planning and housing design, in order to enrich our own approach to working with new and existing communities.

We selected this research theme during the Covid-19 pandemic, when it felt particularly relevant to re-examine our own practices in relation to emergent, collective and participatory models for shaping places to generate the enhanced quality and value that

help communities thrive. While these events have brought a new urgency to our examination of community engagement, our research is also grounded in a deep practical interest in working with residents since our early projects, including in Ballymun Regeneration Masterplan, Dublin, Balham High Road and Somerleyton Road in Brixton, London. This has continued in our more recent work with communities at Westbury Estate in Lambeth, Carpenters Estate in Newham, Oakfield in Swindon in the UK, as well as the Kildare Town Renewal Plan in Ireland.

People Powered Places: a practical guide to community engagement is a result of an extended and focused period of research and discussions within the practice and with invited practitioners and community representatives. Our project began by preparing our working paper, People Powered Places (Prospects #2), the findings of which formed the basis for a programme of workshops and events over the following year. Grown out of interviews and reflections from experts, feedback from community representatives, discussions with a dedicated Focus Group within the practice, this process has allowed us to

arrive at the series of principles and recommendations for community participation that we present in this set of guidance. In particular, the two Resident Review workshops facilitated by The Glass-House were crucial steps in the development of this guidance, where we were able to gain critical feedback from community members themselves.

When we began this project, we intended to develop a guide for use within our own practice. As the project developed, however, our ambitions grew with it. It became very clear that this work held wider potential to advocate for more meaningful community engagement in the industry beyond our own practice, as a public resource that could be used by practioners, community members, and clients alike. One guide document turned into a suite of different material to suit various applications and audiences. The decision was made that the guidance would be made publicly available on our website, for anyone who would like to apply it to their own projects.

As well as opportunities, this also brought with it several challenges. How can we make the guide

accessible and understandable to different types of people? How can we integrate flexibility so that the guidance could be applied to a range of architectural, urban design, or planning projects?

On the following pages, we share this process with you by walking you through the methods we have used, collating reflections, key takeaways, and emerging questions from the events, workshops, and Resident Reviews, and introducing the range of people who have contributed to the development of this guide.

This guide is therefore intended as a reflective tool to be used during the design process, and will be reviewed and refined through its application in live projects. We see it as an everevolving document that we will keep coming back to as we reflect on feedback after testing it out on live projects. We therefore see it as work in progress which will continuously develop our evidence base to support more effective and meaningful community engagement.

Below: Creating a dialogue across different generations in Oakfield, Swindon, with the support of a community organiser. Image provided by Metropolitan Workshop.

How we produced this guide

Words by Ava Lynam, Researcher in Residence Metropolitan Workshop / Technische Universität BerlinA thematic review of engagement perspectives

The starting point for People Powered Places was our initial working paper, People Powered Places (Prospects #2), which brought together interviews, exemplary case studies and engagement stories from practitioners across Republic of Ireland, the United Kingdom and Germany. It captured the perspectives and practices of people who aim to develop policy, undertake communityled development, and enable participatory practices to help communities realise positive change in their local areas. To this broad range of perspectives from architects, urban planners, engagement facilitators, community organisers, initiators of grassroots projects, academics, and public and private sector clients, we also reflected on our own practice at Metropolitan Workshop by reviewing several project case studies.

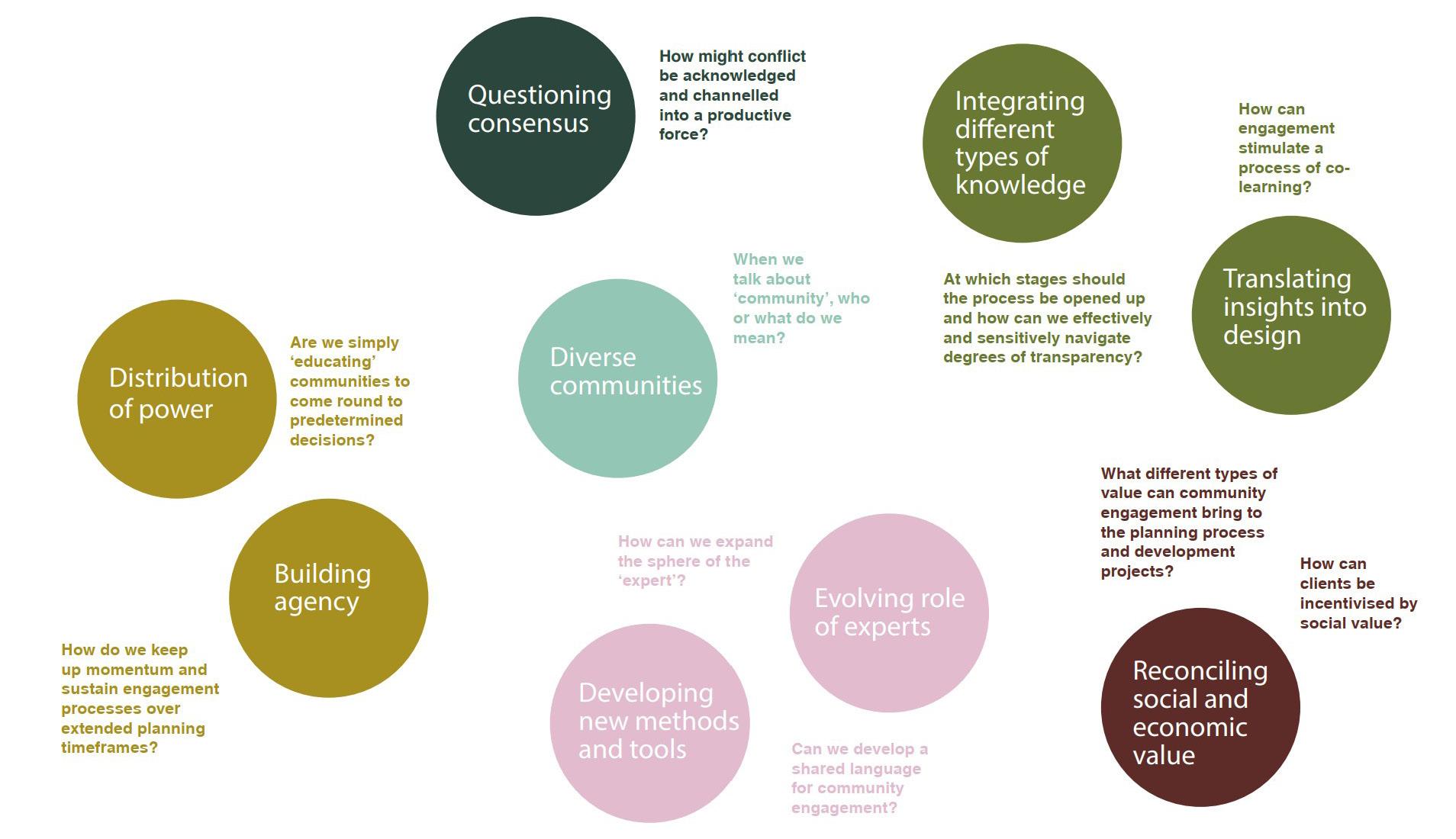

Through this process, it became apparent that the issue of what constitutes meaningful community engagement in practice was highly problematic, and embedded in various interrelated challenges. The contributors of Prospects#2 described a continuum of opportunity in which they actively sought to move beyond the consultation required by the statutory planning system. To interpret these different perspectives, we conducted a thematic review of interview transcripts, text contributions and selected case studies, which allowed us to identify interconnected themes, gaps, and further lines of inquiry for the next phase of research.

Continuing the conversation around key issues

Next, we hosted a roundtable discussion that marked the launch of the next phase of research to continue to interrogate the drivers and obstacles around community engagement in theory, policy and practice. This conversation allowed us to identify key issues to be discussed in more detail, relating to ongoing reform of the planning system. Through a series of workshops facilitated by invited experts, we dived into the themes of: social value, engaging young people, and economic value.

After each workshop, we produced a summary document of key takeaways which emerged out of the presentations and discussions. You can find out more about what we learnt on the following pages.

Going deeper with our Focus Group

To guide us through this process, we established a dedicated Focus Group within the practice across the Dublin and London studios that met on a regular basis and captured a variety of perspectives. Within this small group, we interrogated issues highlighted in the workshops, discussed the next steps for our research process, and reflected on our own role in the process of engagement – one of the key lessons that we have identified.

The sessions were particularly vital when it came to translating these insights into a series of principles and practical recommendations for how engagement with communities could become more meaningful and impactful. The result of these conversations form the foundations of this practice guide, which has gone through several rounds of iterations and feedback. This process has allowed this document to become a genuinely collaborative effort that draws on the shared knowledge of practice members, expert practitioners and community representatives.

Capturing community feedback

A pivotal step in the process was opening up the guide to feedback from community members. Read about our Resident Review facilitated by The Glass-House on the following pages.

Below: Identifying themes and lines of enquiry

Resident review facilitated by The Glass-House

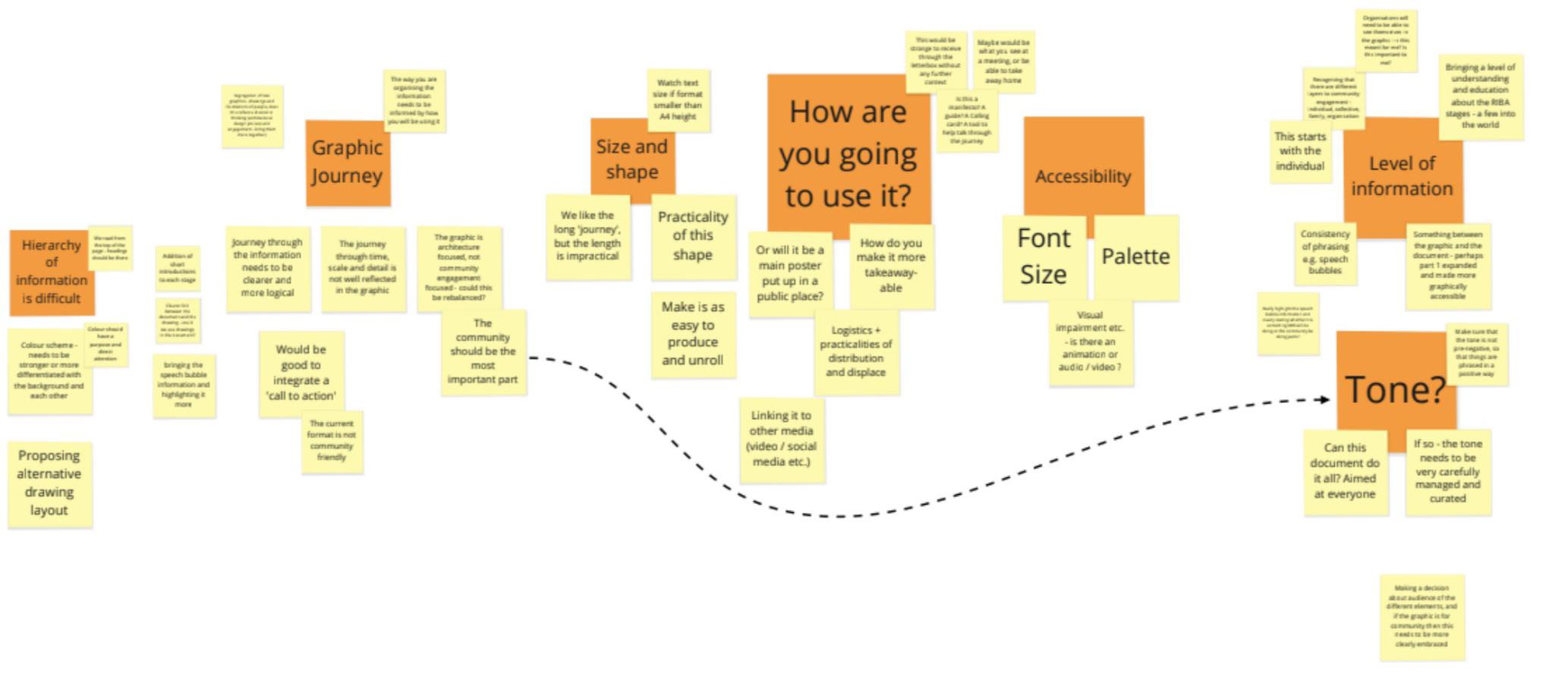

A core aim of Metropolitan Workshop’s work within People Powered Places has been to critically appraise our own approach to community participation. Within this process, we view incorporating input from community members as essential to ensure criticality in our work by challenging our professional preconceptions. This practice guide has therefore been opened up to feedback from the perspective of residents who have lived experience of community engagement processes during complex estate regeneration or new housing projects, offering a valuable opportunity for us to reflect on our practice.

We teamed up with The GlassHouse Community Led Design, a national charity focused on connecting people with the design of their local places,

while enabling inclusive and collaborative design processes. Drawing on their experience of supporting communities engaging with design and development in their neighbourhoods, The GlassHouse hosted and facilitated two intensive workshops in April and July 2022 alongside key community representatives, during which they could critically review our practice guide and consider its applicability from the resident perspective. During the discussion, community participants drew on their own lived experience to explore and evaluate the themes and principles within the documents, suggest areas for refinement, and provide detailed feedback that has played a major role in shaping the ongoing development of this practice guide. After reflecting on the feedback from the first workshop, we invited

the community participants and The Glass-House back to present how we had responded to their comments, and together discussed our next steps and open questions.

Through the support of The Glass-House facilitation, this review process has allowed us to gain critically informed direction on how to approach the implementation of the principles and recommendations we have proposed as they continue to be refined. The guidance documents have been fundamentally shaped by this feedback. These workshops were arguably the most important step in the project, representing the moment where community representatives have become active partners within the process.

Empowering community champions as experts

Sophia de Sousa, Chief Executive, The Glass-House Community Led Design

As part of People Powered Places, Metropolitan Workshop asked The Glass-House to act as a critical friend to reflect on their research on the topic of community engagement in design. Our task was to review their emerging guidance and tools both for embedding participatory approaches in their work, and for championing participatory design within communities, with clients, and to the wider industry.

What made this particularly interesting to us was that Metropolitan Workshop wanted us to bring community representatives into this space, to facilitate a conversation that would empower them as critical friends and experts in this process alongside The GlassHouse team.

Two community champions we had worked with in the past immediately sprang to mind.

The first was Angela Moore, Co-founder and Manager of the Tabot Centre and a member of the Granville Homes Resident Steering Group (GNHRSG) we supported back in 2005 on the Granville New Homes regeneration project in South Kilburn, North London. Angela played an active role in the design journey for the new building for the Tabot Centre, which has provided after school

and school holiday care for children since 1998. Angela has become an articulate champion for participatory design and has helped us support other communities and practitioners learn from the participatory design process she experienced.

The second community champion was Toni Dyer Miller, who we first encountered in 2019 as a local resident intern on the partnership project to regenerate St Raphael’s Estate, led by Karacusevic Carson Architects (KCA) for the London Borough of Brent. Toni did placements at The GlassHouse, Brent Council and KCA, learning about placemaking from the perspective of a design charity, a local authority and a design practice. Throughout, she was also contributing to the design process as a resident of the housing area undergoing regeneration. Toni went on to work both with The Glass-House and KCA, and now works full-time within the placemaking world. She too is a passionate champion for participatory design with a particular interest in the role effective communication can play in its success.

Angela and Toni joined this session with The Glass-House team to carry out a critical review on the guidance and a graphic poster designed to communicate Metropolitan Workshop’s key principles

and methods for engagement in the design process. Our group brought together both the perspectives of community activists who have lived through significant regeneration projects in their neighbourhoods, and our charity’s organisational experience of championing and enabling community participation and leadership in design and placemaking. We were also in that space simply as people, responding quite personally and instinctively, through our respective lived and professional experience, to what was put in front of us.

We began by looking at the key aims, objectives and process that had led to this guidance, and all of us were impressed with:

• The action research approach taken by Metropolitan Worksop, to critically appraise innovative methods of community participation in planning and housing design in order to enrich approaches to working with new and existing communities.

• The intention to create clear and comprehensive guidance in order establish a high standard to engage with communities, both as a practice and for the wider industry, and to give people the tools to do so confidently and effectively.

• Their intention to use this research also as a means of making the case for considered and effective participation to the clients that commission these projects.

• Their desire to communicate their approach and methods for participation clearly and effectively to the communities with which they work in order to galvanise a spirit of collaboration.

Quite quickly, we saw that the core content and messaging was really strong and that we could offer some advice on elements we thought might further enhance it. We were keen to see a bit more focus on the potential power and impact of the journey of participatory design, not just outcomes that emerge at the end. We championed the importance of creating opportunities for social value and social impact and of empowering communities as champions, collaborators

and partners. These ideas were there in the draft documents between the lines, but we felt it was important to be explicit in the guidance.

Generally speaking, they had their core principles and processes in place. The question of how best to communicate them in an accessible way became the focus of most of our discussion. We considered a whole series of angles, including audience, graphic style, layers and levels of information, print and/or digital formats, and indeed perhaps the spectrum of resources required to achieve all of the objectives set out above.

When we fed back the key points back to the Metropolitan Workshop team, we found ourselves congratulating them on the investment of time, resource and collaborative activities to get to the point at which we stepped in. We left them to some

extent with a design challenge, made even more complex by their intention for it to be a live, evolving document.

Our conversations with the project team suggest that this guide is just one step in a larger body of ever-evolving research and work at Metropolitan Workshop. What their extensive research and the many collaborators have brought to People Powered Places has revealed, and evidenced, is that they are part of a larger movement for change. People Powered Places marks a design practice setting out their stall as being committed to this movement for change, and we at The Glass-House look forward to seeing the evolution of the Practice Guide, and to adding it to our toolbox.

Above Angela and Toni reviewing the documents with The Glass-House. Image taken by The GlassHouse

Overcoming participatory idealism

Power relations

• When more citizens come to understand and embrace their power through positive collective action, there will be more answers within the community as more people will be engaged to make change.

• Expanding citizen control in the development process will enable sustainable development, but a major barrier is for ‘power holders’ to genuinely commit to participation.

• There is an overrepresentation of particular actors within the planning process, and attempts to level the playing field need to be considered and planned for before a project begins.

Two-way trust

• Trust needs to be fostered in both directions. The ‘power holders’ need to be committed to transparency with a genuine openness to public scrutiny in order to build trust, including sharing budgets, aims, and limitations.

• There are often limits that what can be achieved, but the most important thing is to foster open dialogue. No matter what issue arises, there are choices and decisions to be explored collectively.

• Participation is about listening, rather than telling or judging. It is for a community to critique their local area, while outsiders need to arrive with humility and be ready to educated by those who have inherent knowledge about their needs. Trust cannot be built if the answer is predetermined.

Engagement as a learning process

• One of the ways to influence planning policy locally is to inform the community about the planning process, and how and where they can intervene in order to have their voices heard.

• Rather than asking people to accept the limits of existing systems, the aim should be to involve people in identifying areas requiring change, and including them in change making processes.

• Even if experts know the answer, the aim is still to work through it collectively.

Scaling-up

• Most people get involved in a local project because they are triggered by something in particular.

• However, there is a need to support more strategic community engagement on

city, regional, and national scales, not only within individual schemes.

• If the community is trusted and supported to take the lead in the process, this has potential to generate an important legacy of engagement, rippling out beyond an individual project.

Tensions between people and planning

• People feel alienated from the production of the built environment and deeply mistrustful of the planning process.

• Within the current planning system, communities tend to be treated as a third party with less rights and power, where the first party is the applicant and the second is the local authority. In architecture, the primary relationship is with the client, while that with the community comes after.

• If development is viewed in the public interest, those who think differently are seen as unwelcome opponents. There is an anxiety around whether the ‘right’ people turn up to participate, and whether they say the ‘right’ things.

TAKEAWAY

Launch Event: 28th April 2021

Chair: Denise Murray, Metropolitan Workshop

Presentations:

The Dilemmas and Responsibilities of Public Participation in Planning

Dr. Andy Inch, Sheffield University

Breaking the Silence; Breaking Cycles

Keith Brown, independent community organiser

Present Voices Future Lives, Housing Towards 2040

Chris Stewart, Collective Architecture

Professional vs local knowledge

• There is a balancing act between listening to what a community wants and needs, and fulfilling professional responsibilities.

• The professional’s views of life can be very different to those of a community experiencing change. Storytelling can be an effective communication tool to bridge this gap.

Participatory idealism

• The idea that people should engage in projects to shape change within their local area has become lauded in mainstream discourse, and participation is often portrayed with imagery that presents it as always good, positive and inclusive.

• However, participation remains a fuzzy and vague concept. In order to acknowledge its realities, we have to ask how true we are to those ideals, and how uncomfortable are we with them. In reality, professional practice and institutional contexts are challenged by some of them.

Policy ambiguities

• The right to participation is increasingly highlighted in recent planning documents, with promising language relating to community empowerment. The realities of community engagement remain overlooked. It can be interpreted in many different ways and there is a danger that it remains tokenistic.

• Tensions are captured in policy language, which suggests that people are invited to participate but only if they are willing to welcome change, i.e. only certain attitudes or opinions are welcome.

• For some policy aspirations to become a reality changes to the structure of the housing industry and land reform are required, and therefore fundamental change in the way we produce our built environment.

• Therefore, action also needs to be started at a grassroots level, instead of waiting for the right legislation to come through.

Accepting and managing conflict

• Agonistic approaches to understanding community engagement are relevant as the planning system itself has inherent winners and losers. Conflict must be accepted as part of the process. Moreover, if only certain attitudes and opinions are welcome, the only option left is protest.

• Conflict is also hard for communities; it can create divisions and put people off wanting to engage. It needs to be managed very carefully.

• But conflict can also be a productive force. Arguments and disagreements are a place to start a process of learning and explore new ideas.

Responsibilities of care

• Colin Ward’s Talking to Architects: “The dilemmas and responsibilities arising from temporary involvement in other people’s lives and hopes”

• As professional planners and architects, we engage with people through the planning system in short, episodic ways, yet we impact their lives in significant ways.

Emerging questions

• Participation can also cause difficulties and damage to people, while alienation can also be reinforced. We therefore have a responsibility of care throughout the participatory process.

(re) learning from history

• Skeffington Report 1969 –key reference in the history of participation and where it was first introduced into the planning system in the UK. First recognition that people should fundamentally be involved in planning and in decisions that affect their lives.

• Diverse drivers: partly out of concern for citizens mobilising against development and managing discontent of stateled planning, partly about democratising and recognising people’s rights.

• Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation 1969 –described the different levels of community engagement, including manipulation, informing and consulting on the lower.

Present voices - future lives: Housing to 2040 Exhibition in Glasgow. Image provided by Chris Stewart

Which ideals of participation make us uncomfortable, and why? How might we reimagine our role as ‘experts’ in terms of community engagement?

How can conflict be managed productively and channelled into a process of learning?

Different values, different currencies

Social Value Workshop: 24th June 2021

Chair: Dhruv Sookhoo and Ava Lynam, Metropolitan Workshop

Presentations:

Outline of Social Value: Nicola Bacon, Social Life

Social Value in Practice: Mellis Haward, Archio

Practice Case Study: Campbell Park North Michelle Tomlinson & Shaun Matthews, Metropolitan Workshop with Tom Jarman, Urban Splash

Beyond the tangible

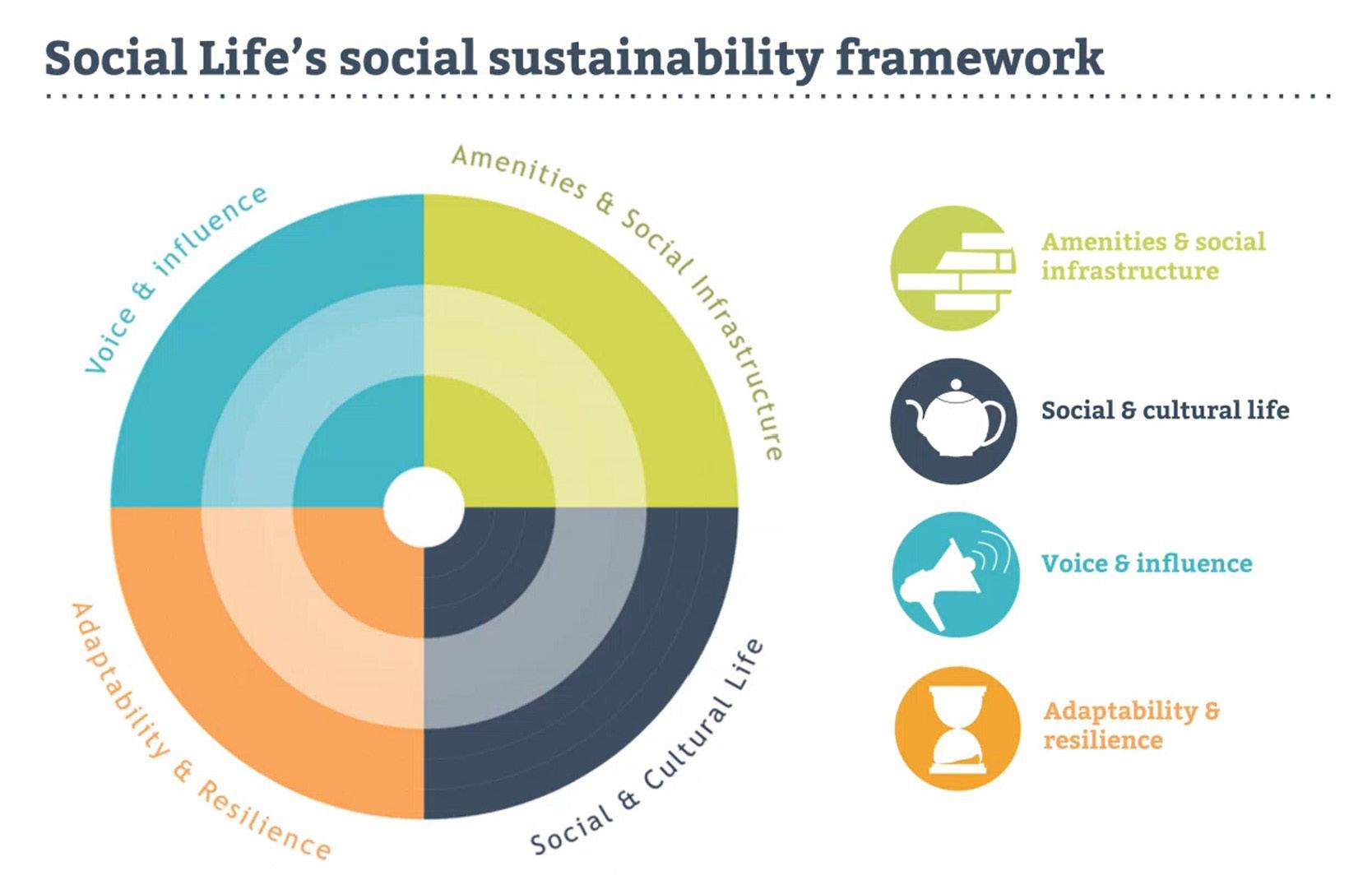

• Social value considers the wider, non-financial impact of projects. Beyond other more tangible factors – such as poverty, inequality, education, health, physical issues – it grasps how people feel about the place they live.

• Social value considers the relationship between people and places, between the physical and non-physical, aiming to understand how the built environment can affect the invisible assets of places – including wellbeing, quality of life, sense of belonging, relationships and social capital, and lived experiences.

• Planners, architects, and designers play a large role in affecting these intangible factors. Understanding social value guides design and investment to help to deliver more impactful projects that can lead to places that work better for people.

Measuring different types of values

• Frameworks for measuring social value (such as the RIBA Social Value tool kit) have been developed, however there is no one way to measure social value.

• Measuring social value should be context specific, with criteria dependent on the project aim: some clients want comprehensive quantitative data from household surveys to present to authorities, while substantial insight into local dynamics can be achieved from fewer, more in-depth ethnographies, interviews and observations, or walking with local people around the site.

• Frameworks and targets for measuring tangible and intangible factors should be developed in partnership with the local community. It is important to get a holistic understanding of social value,

as local people may not be consciously aware of certain factors, while clients may avoid tackling some criteria.

• Different values are measured in different currencies. While some frameworks turn wellbeing and sense of belonging into monetary value, many people believe social value also has its own intrinsic value, and doesn’t need to be put in cash terms.

Value for who?

•

It is important to always question who we are creating value for, what they would want from a place, and who loses and who wins in changes in the social and physical environment.

• Different people want and need different things from public space, housing, or neighbourhoods. Try to understand both explicit and implicit barriers to using space, how different groups live, and how the social fabric is arranged.

• Organisations and groups already active on the site and know the local community very well can help architects and planners understand local issues and represent the voice of different types of people.

Reconciling economic and social value

• Some clients have a longterm interest in a place and see financial benefit in measuring and fostering social value. They understand the relationship between social, economic, and environmental value, and that places can ultimately fail if they fail socially.

• Sometimes social value may be seen by clients in a very narrow way, and aspects relating to wellbeing may get thrown away when budgets get tightened. But architects can demonstrate the benefits of measuring social value, which can even help to deliver better planning outcomes or more intense development.

• The process can take a huge amount of time and money but when done well, there are endless possibilities for

adding value and reducing costs in the longer term. Some interventions may be very easy and cheap to provide, but can generate maximum impact in terms of building relationships with the local community.

Professional assumptions vs lived experience

• What people want might be very different from or clash with the professional assumptions of the architect or the client, which may leave the most impactful interventions overlooked.

• Through their lived experience, residents can offer insightful, precise, and compassionate feedback, which can improve design and create a better outcome for residents. Challenge is to work out how to take this social insight and build it into design.

Biases and positionalities

• Architects and planners can identify social value risks to the client and position themselves as the one with the ability to help mitigate them.

• Architects and planners could also bring their own biases into the process, or be perceived as biased, especially when paid directly by the developer. One way of circumventing this is through the support of a neutral, non-biased party to mediate the process.

• However, outsourcing community engagement can also make it difficult to relate knowledge gained to design decisions, and architects lose power over the end result. It can be powerful if residents are able to communicate directly to the client representatives and architects drawing up the plans for a development.

Activating a site

• Supporting social value should be an incremental and long-term engagement to understand the social impact of change over time and the knock-on impact to the wider area.

• Where there is not already a strong existing community on site, investigate neighbouring communities. Put in effort to activate the space and its social world: design spaces to support an evolving social fabric and invite people from outside to take ownership.

• Every site holds emotional history. It is important to understand wider political and social sensitivities

Transparent communication and effective listening

• Form a genuine collaboration with the client early on with a promise to deliver social value.

• Building empathy helps to deliver maximum social impact. Ask the right questions, take a genuine interest in the issues, and try to minimise professional bias. Listen, take comments on board and dig deeper to find out why people have given the answer that they have.

• Design instruments to open up conversations and shift power dynamics in the process. Enable residents to easily understand their role in the project, and when and how they can input.

• If communities feel their own influence strongly, it enables them to become advocates for the process.

Emerging questions

How do we communicate the interrelation between social value and long term economic and sustainability benefits to key decision makers such as local governments and private developers?

What are the risks in quantifying social value? Should it or can it be monetised?

Who should measure social value?

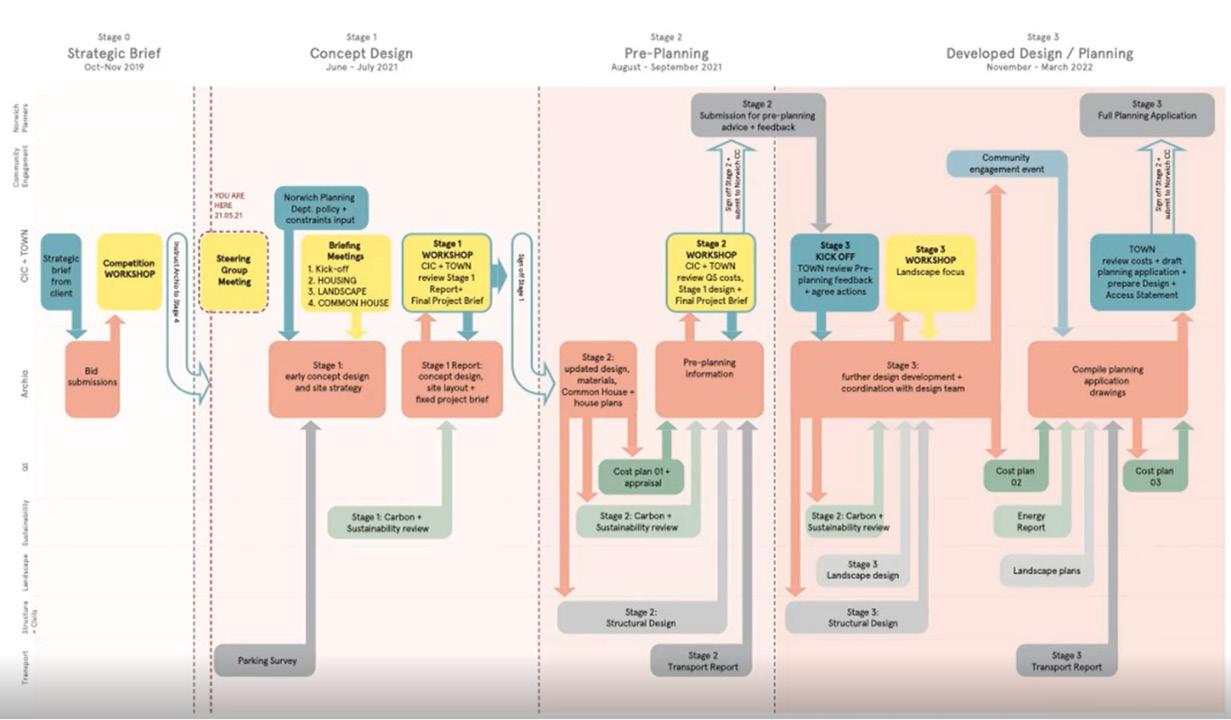

Above: Project flow chart developed

So what is social value?

Nicola Bacon, Social Life

Social value is a concept that we, the Social Life team, work on daily. But the notion remains difficult to explain accessibly and succinctly. Careers have been built on the back of the idea, millions of words have been written describing, analysing and critiquing it. However, it remains a slippery concept; one that sometimes helps bring insight and clarity, one that sometimes focuses too narrowly on employment and green infrastructure, and at worst, one that can be used to muddle and distract.

For us, it is at heart what the built environment contributes that isn’t about money. One quote we use a lot is from Geoff Mulgan, in the Stanford Social Innovation Review: “Social value: the wider, non-financial impact of programmes, for example on individual wellbeing, group social capital and area-level physical environment.”

Our work focuses on the relationship between people and the places they live in, and use. We believe that lived experience and how we feel about places –whether we feel at home and that we belong, how we feel about our neighbours and other people around us, whether we feel safe, whether we feel we have control over our environment – are all critical to our wellbeing. It is easy for built environment professionals to agree, but much more difficult in practice to work out strategies to design, plan, manage and invest in things that are seen

as intangible and somehow nebulous.

We use the concept of social sustainability to express some of these ideas. It’s a strong idea, sitting alongside environmental and economic sustainability, but also a tactical way of drawing attention and focus to our lived experience.

Social value becomes useful to frame how we think about the impact of new developments, or regeneration schemes.

migrant traders and their families to thrive economically and socially. We are yet to see how their replacements add value to the people who live in them and use them, and to the wider area.

Our work on social value tries to capture the things that matter in everyday life. This sits alongside our understanding of inequality, of deprivation and social justice. We know that lives are damaged by the experience of living in poverty, discrimination and inequality. But if you don’t feel at home, or safe, in your neighbourhood this experience is exponentially worse. Neighbourliness and strong sense of belonging and trust in the community can be strong protective assets in places where residents live with the impact of material deprivation.

In Elephant and Castle, we have seen a massive intervention in the built environment as old structures, and their social meaning, are knocked down and replaced. Over 1,200 council homes in the Heygate Estate have been demolished, the thriving economic and social space that was the Elephant & Castle Shopping Centre has recently become rubble – our research in 2014 showed how this space helped Latin American and other

We’ve experimented with different ways of capturing social value, measuring the social sustainability of the South Acton Estate regeneration programme over time with several assessments, codesigning a social value framework with regeneration partners on Woodberry Down, or investigating the social value of the Hackney Carnival.

For us, the value of social value is that it surfaces the ordinary and everyday things that are supporting quality of life – the invisible assets of a place that architects and other professionals sometimes find difficult to see. And critically, it guides design, investment and planning to create places that work for people.

How do schemes deliver value to the people who will live in them, how will they impact on people in the area, and who wins and who loses from change?

Centring young people in the participatory process

The right to play as a right to the city

• Play is a fundamental part of a child’s development, enshrined within the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

• If we put the needs and desires of children at the top of our priority when designing and planning cities and neighbourhoods, we will achieve better places for all types of people.

• We have all been a child at one stage in our lives.

• Social exclusion in play: families with different socioeconomic backgrounds have varying access to quality play infrastructure.

The social legacy of play

• Children, who have the opportunity to play, grow and become adults together leave a legacy of community in a local area.

• Architects and urban designers should keep in mind that people grow up in the places we design and remember them as fondly as the spaces of our own childhood.

• Play spaces and youth centres not only serve the purposes of building friendships, but by occupying young people with

activities and things to do, have been linked to a lower perception of crime in some neighbourhoods.

• In Crawley New Town, a legacy of community in the town was built through play. Constructed in 1957 as one of London’s designated satellite towns, no resident was more than 500m from local centres, including pub, church, community facilities, and playcentres. This legacy has been threatened by the dramatic scaling back of play since 1970 with the divergence from garden city new town aspirations, as well as the worsening of accessibility and increase in car dependence.

Involving children in the planning process

• We should advocate for the involvement of children and young people in the planning process with a child-friendly vision established from the very beginning of the process.

• Children can offer vibrant and creative ideas, and a different way of looking at spaces from adults and professionals.

• It is especially important to involve teenagers into the process, to get a deeper understanding of their desires and needs within

public space, and by doing so, overcome prejudices and stigma surrounding this particular age group.

Considering different types of children

• Play offers opportunities to meet outside a child’s usual circle (age group, local school, neighbourhood, or socioeconomic group) and therefore plays a key role in establishing a social network in an area.

• It can be counter-productive to segregate age groups in terms of play facilities; siblings and differ-ent age groups need spaces where they can play close together. Techniques used for children can also be effective for older people, or those with disabilities.

Engaging Young People Workshop: 4th November 2021

Chair: Dhruv Sookhoo & Ava Lynam, Metropolitan Workshop

Presentations: Child-friendly design and participation

Dinah Bornat, ZCD Architects

Play in Dublin How it started and how it’s going Ozan Balcik, Metropolitan Workshop

Shaping Community through play in Crawley New Town Tom Mitchell, Metropolitan Workshop

Formal provision vs unsupervised exploration

• Non designated play spaces are used as much, or if not more, than local dedicated play spaces. People’s memories of play don’t tend to include playgrounds.

• While formal playgrounds are still important, children need to have the opportunity and freedom to select their own spaces for incidental play outside their front door –around their houses, laneways and streets.

• In the case of Crawley New Town, adventure playgrounds allowed for outdoor play with unconventional play equipment built by children themselves, and freedom to play under guidance of a play leader.

The role of spatial planning and design

• A stimulating environment for play should be accessed directly from the home, is designed as an integral part of the surrounding neighbourhood, is well overlooked and is not segregated by tenure.

• The most critical elements in child-friendly design are car free space, access, connectivity, and overlooking.

• We need to start thinking about play strategically, from the masterplan level, how children will move around, to shops, their school, and their friend’s houses.

• Advocacy for child-friendly design needs to connect across built environment professions. Child-friendly assessments in planning should occur alongside others such as environmental assessments.

• Time of day should also be considered in the design of child-friendly spaces. It is also important to think about how places change after dark and during winter, especially for teenagers.

• Natural assets such as streams or trees are effective and easily-provided play elements that tend to be overlooked in play provision.

Communicating play to developers

• Society, as well as developers and clients, are often wary of young people and teenagers, and their activities in public space. A cultural shift is needed towards inclusive child-friendly cities.

• It is important to keep reminding developers and clients what play means as something they have in their own personal experiences, childhoods, and family lives.

• The more developers are confronted directly by young people through participatory processes, and see the impact of successful play infrastructure and youth centres first hand, the more they understand their needs, and the value play can bring to communities into the future.

• If residents facing a regeneration project are supportive of and excited by the prospect of new play opportunities in the area, this can greatly mitigate chances of the project being rejected.

Emerging questions

Methodologies for creating child-friendly spaces

• Observational studies over various times of day and year can help us understand how children and other types of people use space.

• As well as mapping and observing, it is crucial to talk to children in the local neighbourhood about their understanding of local spaces.

• Storytelling as a powerful tool to sell the idea of play to developers and clients, it allows us to think from

the point of view as a child, and makes the argument more personal by evoking memories.

• The toolkit developed with ZCD Architects alongside with Grosvenor starts by fact finding and listening, asking young people to rate their local places, participatory mapping, then introduces new developments as case studies, and finally, develops a manifesto describing the guiding principles for play identified by the children that has a direct impact on the design of the scheme.

Below: Children at play within the Crown Estate, London 2018. Image provided by Madeleine Waller

How can we design places, neighbourhoods and cities to work better for all types of people, at all times of day?

How can we communicate the benefits of child-friendly design to clients, developers, policymakers, and the wider public?

How can we better include the needs and desires of young people, and other groups, in our projects?

Play and community engagement

Dinah Bornat, ZCD ArchitectsMetropolitan Workshop’s talk on centring children in participatory processes revealed how important play is, but also how rich and varied it can be – from Ozan’s research into past street play in Dublin to Tom Mitchell’s fascinating lived experience of a new town conceived around play.

It is not the first time I’ve come across the Dublin archive of photographs. Ekaterina Tikhonlouk was highly commended in the President’s medals in 2014 for her dissertation Towards a Common Ground for Play: Examining the History of Play and Playgrounds in Dublin’s Liberties. Ozan’s photographs are beautiful too, but do tend to make us nostalgic and mournful, as if it were a bygone activity.

My own project with Madeleine Waller, taken on the Christchurch Estate, counteracts that and is a rich resource of children playing out. It’s perhaps not such a bad thing that we no longer point a camera at children, but we’ve lost the reportage that came with that, and it weakens our understanding of cities and play.

Tom’s own childhood in Crawley New Town would be a fine study alongside others. For example, Sally Watson’s PhD on Byker at Newcastle University and the funded PhD Children’s adventure play in urban Britain, 1955-97

which culminates at an exhibition at the Museum of Childhood.

For us as architects, I believe we need to unpick which spatial and organisational elements support the type of childhood that Tom describes: space to play outside the home, connected to other destinations and services, with support in play and youth work. We can also get better at making the connections between what we do and people’s everyday lives. I believe Sally’s study at Byker will reveal a bygone era of an architect embedded in the community, alongside sociologists, ethnographers and so on, and what can be gained from that way of working.

In our office, we learn a lot from working with children. For example, at Carpenter’s school in East London, we heard from children that they play out regularly and from a young age. They do the same in Thetford in Norfolk, in Plas Madoc in Wales, but not a few miles down the road in Aberfeldy in Poplar or Chingford Mount in Waltham Forest. Why is this? Or research suggests it’s primarily about the availability of space – pre cars, space was everywhere outside the front door and street play was common. Nowadays children play out from as young as two or three in some places but as late (if at all) as 11 in others.

They will ask: How can I call on my friend? Where can I go to the toilet when we’re playing out? How can I play football without breaking a window? These are all specific and resolvable challenges, but ones we forget about when juggling the bikes/ bins/cars/deliveries conundrum. All of us, including developers and house builders, have our own memories of playing out. Setting out what we are trying to achieve, what play ‘looks’ like, can be done so well through stories and those stories can start with us. It is also a great way of connecting with the people we’re working with – after all, we were all once children.

Listening to children talk about their play –they are brilliant at articulating what, where and how they play – is a lesson in urban thinking.

Increasing financial transparency, fostering trust

Socio-spatial consequences of viability

• Scrutinising inputs of a viability model can expose how developments evolve, including increasing property prices, and the rising cost of land construction and finance.

• Efficiencies in design, construction, and cost define pro forma volume house building: design becomes preoccupied with balancing space standards and planning policy.

• Viability modelling can result in increasing numbers of tall buildings, value engineering (where material quality may be lowered), and social housing demolished. It can be used to justify controversial decisions in developments.

Disconnect between people and economic models

• There is a lack of citizen understanding of development-led city-making.

• Consultations usually engage with people towards design but rarely touch on the fundamentals of the development process, such as questions relating to finance or economics.

• There are reservations from both public and private sector about including citizens in financial conversations.

• Some planning obligations (e.g., affordable housing) do not generate high returns, outweighed by construction costs, while developers perceive some uses as spatial opportunity cost (e.g., nursery or community centre).

Acknowledging local people’s financial capabilities

• The general public is very capable of understanding viability constraints. There are similarities to how we manage household finances, which does not differ too fundamentally from an earlystage development appraisal, although more complicated and involving larger figures.

• People should be given trust to make financial decisions, whilst being informed and encouraged to understand what is achievable.

• This involves giving people the opportunity to respond creatively to economic constraints, acclimatising them to the different factors involved in the process.

Economic Value workshop: 11th November 2021

Chair: Dhruv Sookhoo & Ava Lynam, Metropolitan Workshop

Presentations:

Visualising Viability

Gemma Holyoak and Michael Kennedy, MEAD Fellows

Community-led Design Methodologies:

Marmalade Lane and Ballyragget Town Ecologies

Andrea Doyle, Metropolitan Workshop

Increasing financial transparency, fostering trust

• People should have the right to clarity on how public funding is spent.

• More transparency in the development process avoids broken promises and increases trust when changes might be required later in the project.

• Raising awareness about what realistically can and can’t be provided by a development allows residents to better understand the constraints of a project and the reasons why certain things are not viable.

• Explain development economics in straightforward terms, establish financial principles from the beginning of a project, and be upfront about costs and constraints.

• Fostering trust around financial decisions takes time, but committing to it can win unexpected support.

Life cycle costing

• Whole life cycle costing is crucial to consider in addition to initial construction cost, yet it is often overlooked.

• In community-led projects, the data to understand life cycle costs of a project gives us significant insights into how the building is used by the inhabitants for their everyday lives, and can inform future financial decisions.

• Post Occupancy Evaluations are critical in understanding and communicating the economics of existing buildings between different stakeholders.

Methodological approaches to communicating economic value

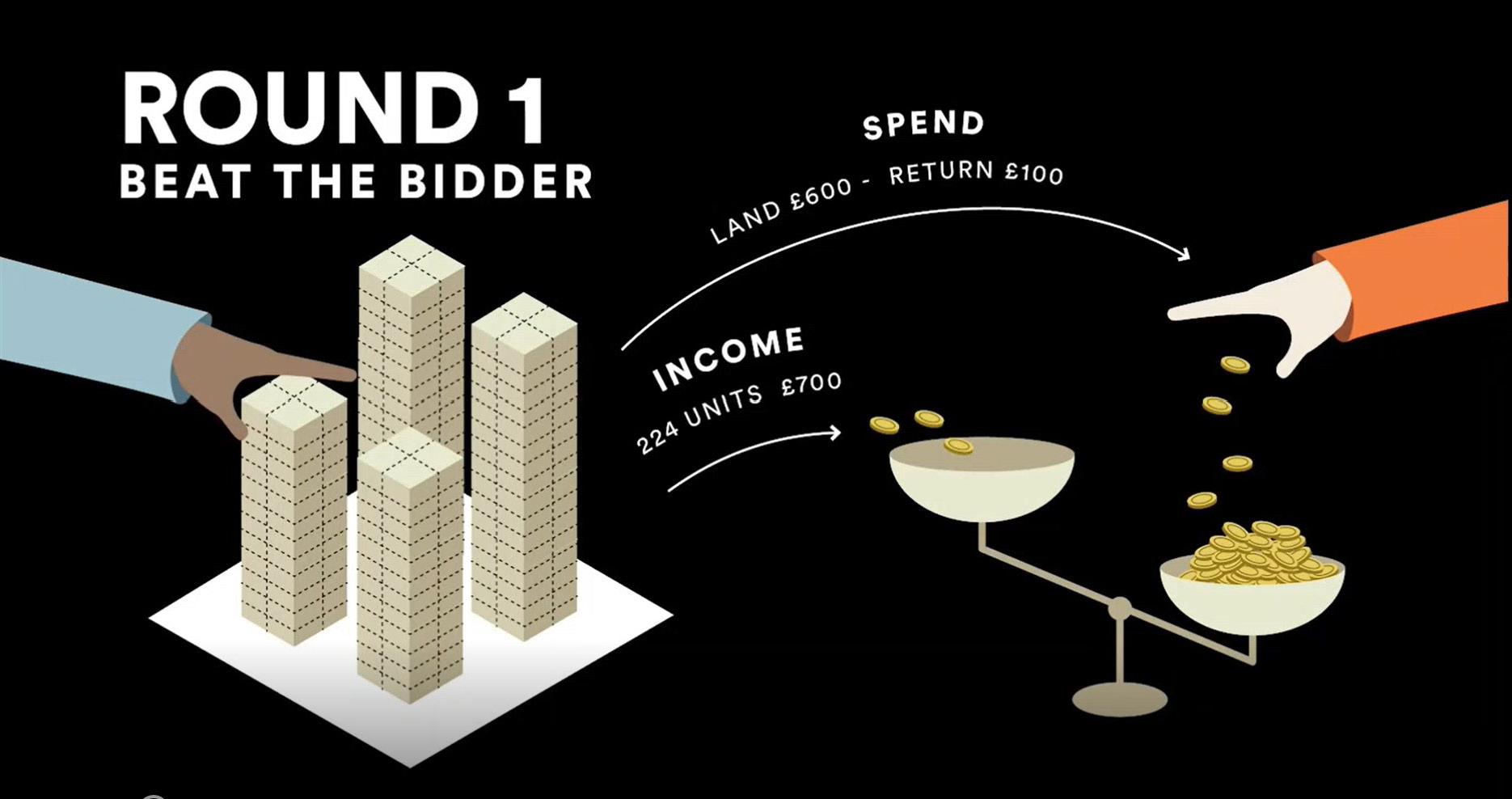

• Gemma and Michael’s ‘Visualising Viability’ game attempts to make the viability process accessible and open up conversations between different stakeholders. It uses different scenarios to show the multiple factors at play when trying to match the cost of development (construction costs, land costs, professional fees, surveys, legal fees, etc.) with the budget.

• The game illustrates the pushand-pull of viability and the trade-offs involved, with the aim of facilitating conversation surrounding these aspects and managing expectations.

• Establishing a community group or resident’s engagement panel early on in the process can also help to mediate financial decisions alongside architects, residents, developers, and council, and opens up discussions around viability to residents at a strategic level.

• Open source financial spreadsheets are another approach to make the complexity of viability models, and the relationships between different factors, transparent to communities.

Emerging questions

Alternative financial approaches

• The notion that economic value derived from land should be a shared asset opens up many possibilities of what can be built when land cost is not a constraint.

• As an alternative approach to financing housing developments, community

land trusts can secure sites at a subsidised rate.

• One example is Marmalade Lane, a co-housing project in Cambridge designed by Mole Architects providing 42 homes.

• As the first developer-led co-housing model in the UK, an innovative approach was taken with the shared land, where each person owned their individual house. Through

these sales, the developer was able to pay back land costs incrementally, and also resulted in diverse housing typologies with resident choice of plot, shell, interior and finishing.

In what ways can developments be used to pay for social infrastructure and public goods in a local area?

How can we communicate changes or amendments as a result of financial constraints to residents and communities?

How can we manage differences in financial expectations, desires, and needs between diverse groups of residents?The Visualising Viability’ game aims to make the viability process more easily understandable. Image provided by Gemma Holyoak and Michael Kennedy.

Visualising viability

Gemma Holyoak and Michael Kennedy, MEAD FellowsVisualising Viability is a MEAD Fellowship funded project developing tools to demystify development viability. The project is developing a standalone board game which allows participants to play the roles of architect, developer, surveyor and planner to collaboratively build a viable scheme.

People are questioning the developments happening in their cities. For instance: why can’t new developments have family housing, a community centre, and good quality materials? Much of the time, these decisions are informed by viability assessments and the needs of finance rather than those of the community or the optimum design for a site.

Coming from a tradition of radical play, such as The Landlord Game, which was co-opted as “Monopoly” following a copyright expiration, Visualising Viability seeks to expose the characters, forces and issues that underpin viability in construction.

Elizabeth Maggie designed The Landlord Game in 1902 as a critique of the exploitative nature of landlords and rent extraction. In contrast to the modern version, the player would go through the game and learn how the landlord class exploited the renter.

Visualising Viability is designed to scrutinise the inputs of a viability assessment, exposing how developments come to

be and how the rising cost of land, construction and finance is leading to a rise in skylines and property prices.

Denise Murray raised an example of a client who shared their viability appraisal with the community involved with the project. This transparency helped the community understand the restrictions of the development which ulitmately allowed for support for the scheme. However, this project also highlighted the need for training and time to engage with people so that they truly understand the information being supplied to them as part of this open process. The idea was raised that a game would be a useful way to debunk myths.

The game is simplified, and intended to be a gateway to become involved in local community networks or participate in engagement events.

It was interesting listening to Andrea Doyle on the governance of the Marmalade Lane cohousing project where ‘working groups’ of members of the intentional community focused on different workstreams of the development. As the ultimate developers of the scheme, the members of the cohousing group always had a view of the scheme’s viability appraisal. They understood every detail of the appraisal and how fluctuations in interest rates, build costs and values would affect the scheme’s viability.

One factor which was highlighted in the discussion was that professionals, not just the public or communities, would also benefit from a game that explains the mechanisms of viability. This touched on the fragmented nature of the built environment where planners, architects and designers are often serving, or subject to, forces of viability without fully understanding where their roles fit in.

Finally, the importance of ethics in prototyping tools for community engagement was raised as a key issue. People who are engaged with nearby development or those who may feel under threat of losing their homes, such as an estate renewal project, should be respected and engaged with as partners not test subjects.

Just as people can manage their household finance, they can understand the simple mechanisms that inform a viability assessment.

Project Contributors

Metropolitan Workshop lead

Ava Lynam

Researcher in Residence, Metropolitan Workshop

TU Berlin

Ava is the Researcher in Residence at Metropolitan Workshop. She works as a researcher in the Urban Rural Assembly project at the China Centre and is PhD candidate at Habitat Unit, both at Technische Universität Berlin. Her research interests focus on the fields of urban sociology, coproductive planning, land dynamics, and urban-rural transformation.

Tom Mitchell

Partner and Studio Leader

Metropolitan Workshop

Tom has worked for 20 years with founding partner Neil Deely and led a large number of residential projects and mixed use masterplans, many of which have won regional or national design awards.

The Glass-House Community Led Design

Elly Mead Design Champion

The Glass-House Community Led Design

Elly is an architectural designer who values and embeds collaborative design into the heart of her practice. She is passionate about producing systematic approaches to issues of access to food, land ownership and community engagement with built projects. As well as engaging and accessible resources, opening up architectural and design narratives to enrich the places in which we live, work and play.

Dhruv Adam Sookhoo Researcher, Newcastle UniversityDhruv led practice-based research projects that promoted innovation and dissemination. Previously, he was Head of Design at Home Group, responsible for championing better residential design quality across a national housing and regeneration programme. He is currently undertaking ESRC-funded doctoral research at Newcastle University, exploring the interprofessional perspectives and practices of architects and planners working to deliver residential design quality.

Sophia de Sousa Chief Executive

The Glass-House Community Led Design

Sophia is an impassioned champion of design quality and an enabler of design practices that empower people and organisations and that help communities thrive. She is also a leader in the field of research on community-led, participatory and co-design practices. Sophia plays an active role in designing and delivering support to communities and practitioners, events and in codesigning research, innovation and resources.

Jake Stephenson-Bartley Design Champion

The Glass-House Community Led Design

Jake’s creative practice draws on the powerful tradition of storytelling to inspire empathetic, sympathetic, and adventurous attitudes towards city-making, connecting realities, and collective creation of worlds for living. Jake has a particular interest in investigating and provoking new strategies for maintenance and “care”, focusing on places sheltering humans, wildlife, and ecosystems.

Community Representatives

Invited Experts and Practitioners

Angela Moore Manager, Tabot Centre

Angela is a wife, mother of six, grandmother of three, a resident of South Kilburn for over 40 years and manager of Tabot Centre, a community facility set up herself and her husband over 30 years ago. Angela gained extensive experience of community engagement as part of the Granville New Homes housing project. This brought her into contact with the Glass-House through their iconic training programmes at Trafford Hall. She is in semi-retirement now but keeps a keen eye on the regeneration programme that is unfolding in South Kilburn.

Dr. Andy Inch

Sheffield University

Andy is a Senior Lecturer in Urban Studies and Planning at the University of Sheffield. His research interests include the politics of planning, public participation and how planning enables society to care for the future (or not). He is currently involved in an AHRC-funded research project on the hidden histories of community-led planning in the UK.

Dinah Bornat

Co-director of ZCD Architects

Dinah is an expert in child friendly cities and urban design. She has published research, contributing to books and journals and advising local authorities and developers. Dinah is a Mayor’s Design Advocate for the Mayor of London. Other roles include; Design Review Panel member for Harrow and Hounslow councils, Wise Friend for Urban Design London, member of the Hackney Regeneration Design Advice Group and an advisor to A New Direction Challenge London.

Toni Dyer Miller Communications Executive, Planning Potential

Toni has an in-depth understanding of community engagement and its importance - established from her previous professional roles in community engagement and her own lived experience being a local resident of a site set to be redeveloped.

Chris Stewart Director, Collective Architecture

Chris is a Director at Collective Architecture, an employee owned company. Their work has been widely published and exhibited. Chris is the inaugural chair of the RIAS Sustainable Working Group and a director of the Scottish Ecological Design Association. He leads a design unit at Strathclyde University, and has lectured at several schools of architecture.

Gemma Holyoak MEAD Fellow

Gemma is a Development Manager at TOWN, a UK developer of housing and mixed use neighbourhoods. She is currently working on community-led and custom build projects in Norwich and Newcastle. Gemma previously worked at Community Led Housing London as a Senior Project Adviser, as well as the LB Southwark and in architecture practice.

Keith Brown

independent community organiser

Keith was Nationwide Building Society’s first Community Organiser. Community Organisers reach out and listen, connect and motivate people to build their collective power. Keith supported the neighbourhoods surrounding the Oakfield project, a not for profit eco-friendly housing development located in Swindon. Portrait image provided by John Boal

Mellis Haward Director, Archio

Mellis is a Director at Archio, an architecture practice with a reputation for community-led housing. She has a particular interest in community engagement and an expertise in running participatory design workshops.

Nicola Bacon

Founding Director, Social Life Nicola co-founded Social Life in 2012, a centre for expertise in innovative placemaking and social sustainability. She advises central and local governments, foundations and third sector agencies, embedding fresh approaches to public policy and service delivery tackling inequality and disadvantage. Nicola has worked across sectors for the Home Office and homelessness charities. She is an Academy of Urbanism fellow, a Design Council BEE, a Brent Design Advice Panel member, and a mentor for Bethnal Green Ventures.

Michael Kennedy MEAD Fellow

Kyle Buchanan, Director, Archio

Kyle is a Director at Archio, and has a passion for promoting outstanding design through Design Review Panels. He has pursued his interest in working with communities by volunteering on boards of community led-housing groups and local charities in London and is a member of the Housing Ombudsman’s Resident Panel.

Michael is a Principal Urban Designer at Enfield Council joining as a Public Practice Associate. He previously worked at SODA, a multidisciplinary studio of architects & designers as well as London Community Land Trust to help guide community groups through the planning process.

Catherine Greig

Founder and Director, make:good

Catherine is the founder of make:good, a London-based architecture and design studio. Born out of her passion for people-centred design, make:good uses meaningful processes of participation to involve people in shaping neighbourhood change.

Dick Gleeson

Dick was Dublin City Planner 200414 and had overall responsibility for strategic/forward planning and development management in the city. A committed urbanist, Dick championed the development of the “6 themes”, a systems-type framework, embedded in the City Plan.

Lesley Johnson

Director of Property and New Business, Phoenix Community Housing

Lesley has led on the set up of several successful stock transfers and delivered significant refurbishment and redevelopment programmes. She previously acted as a Neighbourhood Renewal Advisor to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government.

Lev Kerimol Project Director, Community Led Housing London

Lev previously worked at the GLA where he was involved in establishing the Small Sites x Small Builders programme and contributed to the London Plan, among other projects. He also worked with the LB Lewisham on the early stages of the RUSS (Rural Urban Synthesis Society) community land trust project.

Ciron Edwards Director of Engagement, Iceni Projects

Ciron delivers the stakeholder engagement of some of London’s largest projects, and has had longterm involvement with New Deal for Communities and Housing Market Renewal initiatives across the UK. He has extensive experience delivering urban regeneration and public realm projects.

Helen Wallis-Dowling

co-founder, Ansuz Action

Helen has many years experience working alongside communities, facilitating youth-led social action, and community organising projects. She has led the curriculum development and training for two national government funded community organising programmes. Helen is a director of Ansuz Action, who support organisations to make ultra-inclusive engagement the norm.

Dr. Michael LaFond Community developer, Spreefeld Cooperative and Statbodenstiftung

Michael is a cohousing expert, activist, and professor of urban planning. He is deeply involved in local grassroots activities relating to alternative models of housing and land management. Michael is the founder of id22: Institute for Creative Sustainability, a nonprofit civil society organisation that supports participatory initiatives in Berlin. He is on the advisory board of Berlin’s community land trust Stadtbodenstiftung.

Nick Woodford

Co-founder, Mesh Workshop and Peckham Coal Line

While studying Architecture at Central Saint Martins, Nick launched the Peckham Coal Line, bringing local residents together to adopt and connect unused open spaces along a Peckham railway line to form a public linear park. Previously, Nick was a travel writer and photographer.

Metropolitan Workshop Focus Group

Naomi Murphy Co-founder, Connect the Dots

Naomi is co-founder of stakeholder engagement practice Connect the Dots. Based in both Dublin and Philadelphia, they develop tailored strategies and expert insights to help build cities, regions, and entities focused on the health and happiness of all citizens.

Portrait image provided by Alex Foster

Stephen Hill Founding Director, C20 futureplanners

Stephen is a planning and development surveyor, and has been a long-time practitioner and advocate of co-production in the building of new settlements, the regeneration of urban housing estates and neighbourhoods, as well individual community-led housing developments. He is founder and director at C2O Futureplanners.

Alexandra Bullen Metropolitan Workshop

Fundamentally buildings are for people. Ally believes in the important of community engagement as an integral part of the design process. It is also vital for ensuring that buildings and public spaces meet the end user’s needs. Having work on numerous housing project Ally has first hand knowledge of the positive impact an integrated community engagement approach can have on the quality of new developments and how it can empower residents during the design process.

Cathal Cocoman Metropolitan Workshop

Cathal assisted with the delivery of the launch event, including the creation of the timeline and the boards.

Denise Murray Metropolitan Workshop

Denise is the studio llead in the Dublin studio. She has nearly 20 years experience as an architect working in Ireland, France and the UK on all project stages with specialist knowledge of urban design, regeneration and housing.

Denise is on the RIAI Housing Commitee and a design fellow at UCD Scholl of Architecture specialising in urban design, housing and community regeneration

Ethan Medd Metropolitan Workshop

Ethan is a part 1 who has recently joined for his year’s work experience. His enthusiasm for any task makes him a valuable addition to the team. He worked initially on the graphic.

Richard Robinson Metropolitan Workshop

Richard has a background in architecture and has helped architects with submissions, comms, and PR/marketing activities for over 20 years. He coordinated the production of the documents.

Michelle Tomlinson, Metropolitan Workshop

Michelle is a Design Panel Member and a Design Tutor. She has several years of experience designing and delivering award-winning residential and educational schemes, as well as masterplans. She is a member of the Design South East Review Panel, Ebbsfleet Design Forum and Guildford Strategic Sites Panel, where she reviews the quality of places and buildings.

Kruti Patel Metropolitan Workshop

Kruti has a passion for community engagement as she believes that it is of utmost importance, at the beginning of a project, to facilitate listening, encourage collaboration and hear from as many diverse voices from within the community as possible. Where possible, Kruti ensures that this kind of engagement is considered and implemented, early on in the design development of projects to promote empowerment and enhance the cohesion and resilience of an existing community. Kruti believes designers have the ability to influence change, and by utilising the wealth of knowledge and insight within communities, can only be to the betterment of a development.

Ozan Balcik Metropolitan Workshop

Ozan graduated from University College Dublin with first class Honours. His thesis investigated community engagement and empowerment in terms of ‘Playful Resilience’. Ozan has continued his research into practice assisting in the preparation of the PPP exhibtion and also with projects outside of practice with A Playful City in Ireland. Ozan was part of the team delivering the Kildare Town Renewal Plan while also working on the town renewal plans for neighbouring Newbridge, which successfully received funding from the Urban Regeneration and Development Fund for further research and development in 2019.